Abstract

Breast cancer remains one of the most lethal diseases for women worldwide. Marine populations are considered a vast reservoir for novel bioactive metabolites, particularly marine Actinomycetes, which are known to produce various bioactive compounds with antitumour, antibacterial, and antifungal properties. A promising new marine strain was isolated and identified as Streptomyces albidoflavus strain EgyAB2 (16 S rRNA gene sequence accession number ON680945.1). The anticancer activity of the extracted compounds was tested in the MCF7 cell line using a sulforhodamine B (SRB) bioassay, which revealed an IC50 of 0.36 µg/ml compared to the chemotherapeutic drug 5-fluorouracil (0.35 µg/ml). Additionally, the anticancer activity was confirmed by a dimethyl-thiazol-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) bioassay, which showed an IC50 of 17.46 µg/ml. The mode of action of the treated breast carcinoma (apoptotic effect) was studied via qRT-PCR, revealing a significant role in anticancer treatment. Although the extracted compounds exhibited high antioxidant activity in the diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical-scavenging assay, they presented an IC50 of 8.92 µg/ml and an inhibition percentage of 56.08%. Chemical characterisation was performed via GC‒MS, 1 H-NMR, and FTIR spectroscopy analyses, revealing the presence of 2-D N-methyl imidazole, 2-nonadecene, 1-D-2-methyl imidazole, and propane dinitrile, all of which exhibit antitumour activity.

Keywords: Marine Streptomyces, Anti-breast carcinoma, MTTbioassay, SRBbioassay, Apoptosis

Introduction

Each year, approximately 502,000 people die from breast cancer, making it the most common cancer among women worldwide. The incidence of breast cancer continues to rise, influenced by various factors including genetics, lifestyle, and environmental exposures. Furthermore, breast cancer can metastasise to other organs, such as the lungs, brain, and bones [1–4]. This ability to invade distal tissues underscores the critical need for effective therapeutics to manage not only localised disease but also metastatic progression. Cancer cells resist apoptosis due to the overexpression of oncogenic genes such as c-Myc, which promotes cellular division while inhibiting the tumour suppressor p53 and anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2 [5, 6]. These alterations enable cancer cells to survive and proliferate despite the presence of therapeutic interventions. Conversely, the resistance of cancer cells to apoptosis can be counterbalanced by downregulating the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins (caspases, Bad, Bax, etc.) and obstructing the tumour-suppressive function of p53 [7, 8]. Overcoming this resistance via apoptotic pathways is crucial for effective cancer treatment. This can be accomplished by targeting p53 (through drug, gene, and immunotherapy), caspases (using drug and gene therapy), and members of the BIR family, thereby enhancing the effects of IAP [9].

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in marine-derived compounds as potential sources of innovative therapeutic agents [10–15]. Marine Actinomycetes, in particular, are employed to produce various novel bioactive compounds with antitumour, antibacterial, and antifungal properties [16–18]. These microorganisms thrive in diverse marine environments and possess unique genetic and biochemical traits that enable them to synthesise a wide array of bioactive metabolites. Streptomyces, regarded as the most prominent genus of Actinomycetes for the production of bioactive compounds, has been extensively studied for its therapeutic potential. Active materials from Streptomyces species can be extracted, separated, and chemically identified through various advanced chemical assays [19–21].

This study is aimed at presenting the isolation, morphological characterisation, molecular identification, and antitumour effects of a bioactive compound derived from a marine Actinomycete, specifically concerning breast carcinoma treatment. The findings are intended to enhance understanding of the potential role of marine-derived compounds in cancer therapeutics, particularly their impact on apoptotic pathways and the structural characteristics of the bioactive compound. The extract from the selected Streptomyces albidoflavus strain EgyAB2 is aimed at demonstrating notable anti-breast cancer activity, accompanied by substantial antioxidant properties. By elucidating the mechanisms of action associated with these marine-derived agents, this study aims to pave the way for innovative strategies in cancer therapy and address the urgent need for more effective treatment options.

Materials and methods

Isolation and antitumour activity screening via red potato disc bioassay (RPD)

Microorganisms were isolated on a selective Actinomycetes medium from a seawater sample collected from the Western Harbour of Alexandria, Egypt (GPS: Latitude: 30° 57’ 23.38” N, Longitude: 29° 29’ 48.71” E) using previously described methods [22]. Marine samples were taken from the mediterean Sea coast between 30 cm and 1000 cm deep using sterile tools and stored at 4 ˚C in sterile containers (polythene container) for further microbiological analysis.

Antitumour activity was assessed using a red potato disc (RPD) bioassay following established protocols [23]. During this assay, potato discs were infected with the tumour-inducing bacterium Agrobacterium tumefaciens ATCC 19,358, supplied by the Egyptian Culture Collection Network. The infected potato discs were treated with Actinomycetes supernatant (T), applied at a volume of 50 µl/disc as a mixture of C + isolate supernatant at a ratio of 1:2. Each treatment was examined separately and compared with the blank and control groups.

All discs were incubated at 28 °C for two weeks. To the blank potato discs (B), 50 µl of sterile seawater was added. In the control potato discs (C), a 50 µl suspension of A. tumefaciens, pretreated with 100 µl of Ampicillin (1000 mg), was applied to eliminate the infection effect of A. tumefaciens on the potato discs without affecting their Ti plasmid activity. Following incubation, the potato disks were stained with Lugol’s reagent and observed under an electron microscope. The percentage of tumour activity and antitumour activity percentage of the tested supernatant (T) were calculated according to Coker et al. [23].

DNA extraction

Molecular identification was conducted via the 16 S rRNA gene sequence at Sigma Scientific Services Co., Cairo, Egypt, in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was extracted from a pure culture and subsequently purified using a Gene JET Genomic DNA purification kit (Thermo). The extraction steps were performed as follows: a 200 µl sample (liquid media containing bacteria) was added to a microcentrifuge tube, along with 95 µl of water, 95 µl of solid tissue buffer (blue), and 10 µl of proteinase K. The mixture was thoroughly mixed and incubated at 55 °C for 2 h. After incubation, the mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 1 min, and the aqueous supernatant (300 µl) was transferred to a clean tube. Next, 600 µl of Genomic Binding Buffer was added, and the mixture was mixed thoroughly before being transferred to a Zymo-Spin™ IIC-XL column in a collection tube. Centrifugation was performed at ≥ 12,000 × g for 1 min, after which the collection tube was discarded, and the mixture was thoroughly remixed.

Following this, a 400 µl aliquot of DNA prewash buffer was added to the column in a new collection tube, and centrifugation was again conducted at 12,000 × g for 1 min. Subsequently, 700 µl of g-DNA wash buffer was added, and the mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 1 min, with the collection tube emptied afterward. Finally, 200 µl of g-DNA wash buffer was added, and the mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 1 min before discarding the collection tube. An elution buffer (0.3 µl) was then added, and the mixture was incubated for 5 min before being centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 1 min.

PCR amplification and sequencing of the 16 S rRNA gene

The amplification of the genomic DNA was performed at the Sigma company using PCR with Maxima Hot Start PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The procedure was as follows: (1) The Maxima® Hot Start PCR Master Mix (2X) was gently vortexed and briefly centrifuged after thawing. (2) The following components were added to each 50 µl reaction mixture at room temperature: 25 µl of My Taq Red Mix, 1 µl (20 picomol) of the 16 S rRNA forward primer, 1 µl (20 picomol) of the 16 S rRNA reverse primer, 8 µl of template DNA, 18 µl of water, and a nuclease-free mixture, resulting in a total volume of 50 µl. The primers used were specific for actinomycetes: F: AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG and R: GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT. A Gene JET™ purification column was employed to clean the PCR product.

The PCR thermal cycler conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 6 min, denaturation at 94 °C for 45 s, annealing at 56 °C for 45 s for 35 cycles, extension at 72 °C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The sequences of the selected isolates were analysed using the BLAST program (www.blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the MEGAX program [24].

Effects of different culture media

Various recommended culture media were tested to identify the optimal conditions for growth and antitumour activity, including starch nitrate medium (M1), starch casein nitrate medium (M2), potato dextrose medium (M3), and oatmeal nitrate medium (M4) [25]. Bioactive pure colonies were harvested from oatmeal nitrate agar plates and activated in 10 ml of nutrient broth in a shaker incubator (Lab Tech) at 30 °C.

To investigate the effects of different media, a 2 ml inoculum was introduced into 500 ml glass flasks containing the four tested media. These were incubated in a shaker incubator (Lab Tech) at 30 °C, set to shake at 120 RPM for 7–14 days. Throughout the cultivation period, optical density (OD) was measured at λ550 using an E-Chrom Tech spectrophotometer. The isolate suspension was subsequently centrifuged (K3 series, Centurion Scientific) at 5000 rpm for 10 min. After centrifugation, the cells were dried overnight in a hot air oven (Memmert) at 105 °C until a constant weight was achieved. The growth curve over time was estimated using the best-performing culture medium to optimise the cultivation time [26].

Optimization and verification of the culture medium via plackett–burman statistical design

Statistical analysis was employed to optimise the ideal conditions for maximum production of antitumour agents using the Plackett–Burman experimental design. The major components of the culture medium, along with physiological conditions, were refined to enhance antitumour activity. Seven independent variables were screened across nine combinations, utilising high (+) and low (−) levels in comparison with the basal culture medium. The data obtained were statistically analysed using a t-test to identify significant factors. A verification test was conducted in triplicate to predict the near-optimum levels of the seven independent variables under the optimised culture conditions [27].

Extraction of the active compound using different organic solvents

One litre of inoculated oatmeal broth was incubated at 30 °C in a shaker incubator (120 rpm) for 7–10 days. The supernatant was divided into four equal volumes and extracted separately with an equal volume (1:1 v/v) of ethyl acetate, n-hexane, acetone, and diethyl ether. The mixtures were shaken multiple times in a separating funnel until complete separation was achieved. The collected organic layers were air-dried overnight in a desiccator, and solvent evaporation was performed using a rotary evaporator set to 40 °C. This process yielded a crude ethyl acetate extract, which was directly tested for antitumour activity via the RPD assay. No additional purification steps (e.g., column chromatography, HPLC) were applied to isolate individual compounds, as the study focused on preliminary screening of the crude extract’s bioactivity.

Biotoxicity assay using Artemia salina

The biotoxicity experiment was conducted using Artemia salina as a biomarker for assessing the toxicity of the selected isolate extract. Artemia salina eggs were sourced from the NIOF hatchery unit and hatched within a laboratory hatching system. Twenty-four-hour-old A. salina nauplii were employed in this assay. Different doses (250, 500 and 1000 ppm [v/v]) of the tested extract were administered, and the mortality percentage was assessed in the 24-hour-old A. salina nauplii. Mortality percentages and the half-lethal dose (LD50) were determined after 24–48 h using the probit analysis method [28].

Cytotoxicity test using a Sulforhodamine B (SRB) bioassay

The SRB assay was conducted at the Faculty of Pharmacology, El-Azhar University, Cairo. This assay aimed to measure the relative cell viability of a cancerous cell line (the breast cancer cell line MCF7) exposed to the tested extract, with IC50 determined in comparison to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) as a control. The breast adenocarcinoma cell line was acquired from the Faculty of Pharmacology, El-Azhar University, Cairo. The cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 100 mg/ml streptomycin, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum in a humidified atmosphere with 5% (v/v) CO2 at 37 °C. The extract was also tested against a normal human skin fibroblast cell line (HSF) to confirm its biosafety profile [29]. Human skin fibroblasts (HSFs) were obtained from Nawah Scientific, Inc. (Mokatam, Cairo, Egypt) and were maintained in DMEM as described earlier. Cell viability was assessed using the SRB assay.

Cytotoxicity test using the dimethyl thiazol Diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) bioassay

The MTT assay was performed at the City of Scientific Research and Technological Applications. Breast cancer cells (MCF7) were seeded in flat-bottom 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well (100 µl) in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator and allowed to attach for 18 h before treatment. Following complete attachment, the drugs were administered to the cells in triplicate at concentrations of 500, 250, 125, 62.5, and 31.25 µg/ml, after which they were incubated for 48 h under the previously specified culture conditions. After 48 h, the media over the cells were removed and replaced with fresh media (100 µl/well) containing 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) reagent at a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml, and the cells were returned to the incubator. After 4 hours of incubation, the media were removed, and dimethyl sulfoxide was added (100 µl/well). The plates were then placed on a shaker for 15 min, and absorbance was measured at λ570 nm using a microplate reader [30]. The breast adenocarcinoma cell line was sourced from the City of Scientific Research and Technological Applications, Borg El-Arab, Alexandria.

Mode of action of bioactive compounds on breast carcinoma (MCF7) via qRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was carried out at the City of Scientific Research and Technological Applications, Borg Al-Arab, Alexandria. Analysis was performed to quantitatively assess the messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of the TNF-alpha, P53, P21 and BCL2 genes in MCF7 cells treated with the isolates extract.The MCF-7/TAMR-1 Human Breast Cancer Cell Line was obtained from SCC101, Sigma-Aldrich, USA. Total RNA was isolated with a RNeasy mini kit (Qingen, Germany) supplemented with RNase-free DNase set to remove the genomic DNA (Table 1). The RNA concentration was determined via a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Total RNA (100 ng) was reverse-transcribed to complementary DNA (cDNA) via the Revert Aid™ First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, America) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The maxima SYBR Green ROXqPCR Master Mix kit was used for qRT-PCR. Real-time PCRs were performed via Step One Plus (Step One™ Real-Time PCR Systems -Applied Biosystems). The PCR amplification conditions consisted of 10 min at 95 °C followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s and annealing and extension for 1 min at 60 °C. The data were analyzed via the comparative Ct (ΔΔCt) method [31]. The threshold cycle(CT) is the cycle at which the fluorescence level reaches a certain amount, whereΔCT is the difference in the threshold cycle between the target and reference genes: ΔCT = CT (a target gene) − CT (a reference gene). The ΔCT for the target sample is CTD −CTB, and the ΔCT for the reference sample is CTC −CTA. Then, we calculate ΔΔCT, which is the difference in ΔCT as described in the above formula between the target and reference samples:

Table 1.

The primer sequences of the apoptotic genes of MCF7 cells

| Primer name | Sequence From 5`-3` |

|---|---|

| GAPDH |

Forward: 5’-GTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACAGCG-3’ Reverse: 5’-ACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAA-3’ |

| BCL2 |

Forward: 5’-TTGTGGCCTTCTTTGAGTTCGGTG-3’ Reverse: 5’-GGTGCCGGTTCAGGTACTCAGTCA-3’ |

| P53 |

Forward: 5’-TAACAGTTCCTGCATGGGCGGC 3’ Reverse: 5’ -AGGACAGGCACAAACACGCACC 3’ |

| P21 |

Forward: 5’-AGGTGGACCTGGAGACTCTCAG-3’ Reverse: 5’-TCCTCTTGGAGAAGATCAGCCG-3’ |

| TNF-Aalpha |

Forward: 5’-CTCTTCTGCCTGCTGCACTTTG-3’ Reverse: 5’-ATGGGCTACAGGCTTGTCACTC-3’ |

ΔΔCT = ΔCT(a target sample) – ΔCT(a reference sample) = (CTD − CTB)−(CTC − CTA).

The final result of this method is presented as the fold change in target gene expression in a target sample relative to a reference sample, normalized to a reference gene. The relative gene expression (2−ΔΔCT) is usually set to 1 for reference samples because ΔΔCT is equal to 0 and therefore 20 is equal to 1 [32].

Different biological applications of the actinomycetes isolate Ethyl acetate extracts

Antimicrobial activity using the well diffusion method

Antimicrobial activity was evaluated against 11 different bacterial pathogens: Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923), Escherichia coli (ATCC 8739), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 9027), Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633), Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 29212), Klebsiella pneumoniae (ATCC 13883), Vibrio damsela (ATCC 33539), Aeromonas hydrophila (ATCC 13037), Vibrio fluvialis (ATCC 33809), and Pseudomonas fluorescens (ATCC 13525). All bacterial pathogens were acquired from the Egyptian Culture Collection Network. The antimicrobial activity of the marine Actinomycetes isolates was tested using the well diffusion method. Fresh microbial lawn cultures of the test pathogens were prepared on Mueller–Hinton agar media. Wells were created in the agar medium using a sterile cork borer.

The crude extract, prepared from the secondary metabolites of the Actinomycetes, was diluted to a final concentration of 100 µg/100 µl in dimethyl sulfoxide. One hundred microlitres of the final dilution of this crude extract were added to each well. The plates were incubated at 37 °C overnight, and the zones of inhibition were measured in millimetres (mm). The results were then compared with those from antibiotic sensitivity tests using various commercial antibiotics [33].

Antioxidant activity via a Diphenyl-2-Picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical-scavenging assay

Antiradical activity was assessed based on the reaction with stable DPPH radicals dissolved in absolute methanol. The reduction of DPPH by an antioxidant results in a decrease in the absorbance of the solution at 515 nm. After incubation for 30 min in the dark, the absorbance at 515 nm was measured, and the antiradical activity was determined according to the Brand-Williams method [34].

The antiradical activity was calculated using the following formula:

|

where Acontrol is the absorbance of the control solution (DPPH solution without sample) and Asample is the absorbance of the solution with the extract.

Notably, a lower absorbance of the reaction mixture indicated a higher DPPH scavenging activity [34].

Analysis approaches

Statistical analysis

Triplicate data were collected from all cases during the optimisation analysis, biotoxicity tests, and bioactivity assays of the selected isolate. The results were analysed according to the mean value ± standard deviation (SD) in triplicate. Microsoft Excel software, version 2010, was utilised to calculate the means and standard deviations of all relevant data.

Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS)

The GC–MS analysis of the ethyl acetate extract was performed using a Thermo Scientific Trace GC Ultra/ISQ single quadrupole MS, equipped with a TG–5MS fused silica capillary column (30 m, 0.251 mm, 0.1 mm film thickness) at the National Center for Research in Cairo. The percentage of each compound was calculated as the ratio of the peak area to the total chromatographic area [35].

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR)

The 1 H NMR analysis was conducted using a Jeol DELTA2_NMR (version 1) at the National Center for Research in Cairo. The absorption peaks that appear in the ^1H NMR spectrum are represented by the difference in resonance frequency of a nucleus relative to a standard, measured in parts per million (ppm) or as the chemical shift (δ). The value of the chemical shift (δ) is influenced by several factors, including (1) the inductive effect, (2) bond anisotropy, and (3) hydrogen bond formation [36].

FTIR spectroscopy analysis

The functional groups of the ethyl acetate extract were confirmed via Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (Vertex 70) at the central laboratory of NIOF, Alexandria [37].

Results

Anti-tumour activity assessment via RPD bioassay

The potato discs examined under a simple microscopic lens reveal the starch granules infected by the Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmid (B), in comparison to the treated discs (C&D) and the negative control, the blank discs (A). The maximum antitumour activity was 92.5% greater than that of the blank (100%) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Photographs of simple microscopic examination of different potato discs showing the blue colour of untreated potato discs, blank (A), infected potato discs with Ti plasmid (B) and treated potato discs with 50 µl of the tested marine supernatant (C & D)

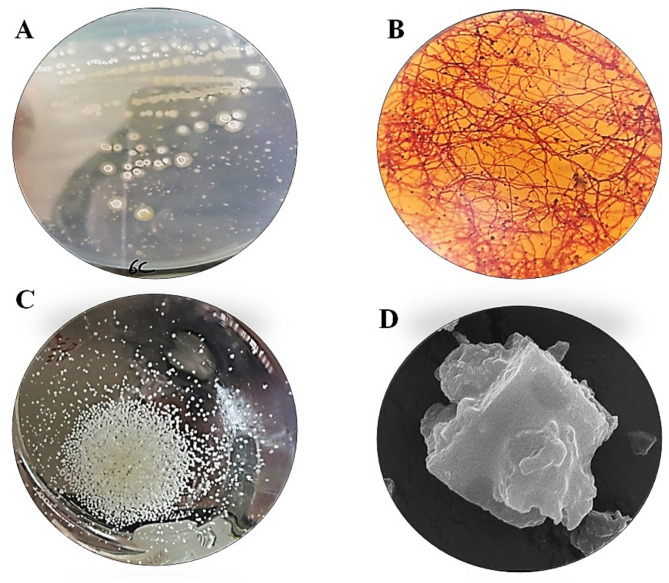

Characterisation of the marine anti-tumour producers

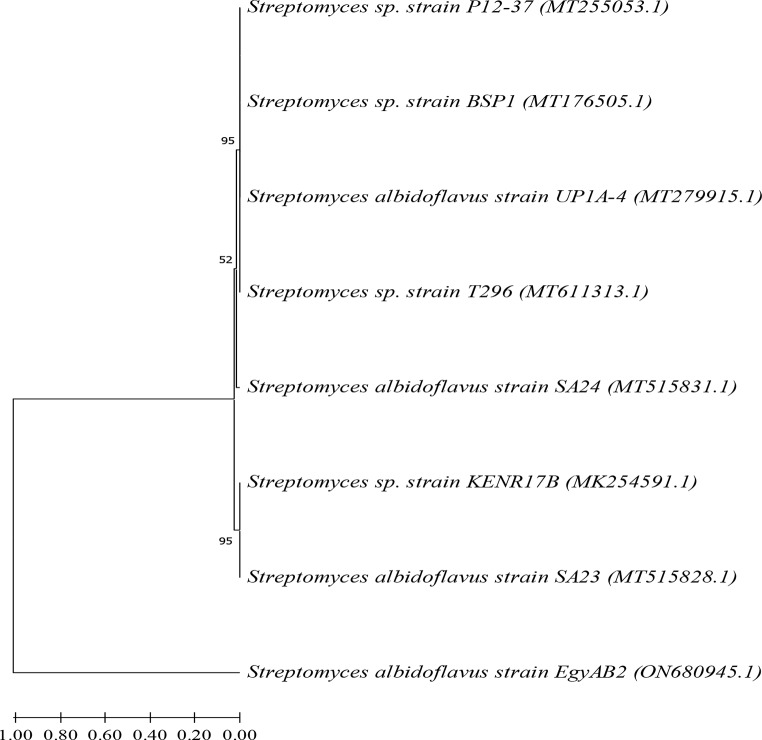

The photographs in Fig. 2 illustrate the colony appearance on the M4 agar plate (A) and their aggregation in M4 broth medium (B). These cells were identified as gram-positive actinomycetes (C) and were genetically characterised as the Streptomyces albidoflavus strain EgyAB2 via the 16 S rRNA gene sequence, facilitating the isolation of a new marine Streptomyces strain. The strain has been deposited in the Egyptian Microbial Culture Collection Network (EMCCN), “Marine Microbes of Economic Value, NIOF, Alexandria, Egypt,” which is sanctioned by the Academy of Scientific Research and Technology, National Network for Conservation and Handling of Microbial Cultures. It is encoded as EMCCN4266 Streptomyces albidoflavus strain EgyAB2 under accession no. ON680945.1, according to the Gene Bank database. A phylogenetic analysis based on the likelihood method is presented in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

The photographs show several characteristics of the novel marine strain S. albidoflavus strain EgyAB2: colony appearance on M4 agar medium (A), ball-shaped aggregates on M4 broth medium (B), Gram + ve mycelia under the oil lens microscopic examination (C) and the crystalline shape of the antitumor byproduct ethyl acetate extract under the scanning electron microscope (D)

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree of the marine Streptomyces albidoflavusstrain EgyAB2 and other related Streptomyces species in the Gene Bank database

Effects of different culture media on the marine S. albidoflavus strain EgyAB2

Four different culture media were tested. The oatmeal nitrate (M4) medium was the most effective for S. albidoflavus strain EgyAB2 compared with the other culture media: starch nitrate (M1), starch casein (M2), and potato dextrose (M3). The maximum growth, determined by measuring the optical density (OD) at λ550 nm, reached 0.95 (≈ 1.0) after 120 and 144 h of incubation (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The time growth curve and dry weight biomass of the marine S. albidoflavus strain EgyAB2 in oatmeal nitrate culture medium

Time growth curve of the marine S. albidoflavusstrain EgyAB2

The optical density was measured at 550 nm parallel to the dry biomass of the marine S. albidoflavusstrain EgyAB2 obtained during different incubation periods. The highest optical density (0.95) was obtained after 120–144 h, with a biomass of 15.4 g/l dry weight (Fig. 4).

Optimizationof the antitumor activity of the marine S. albidoflavusstrain EgyAB2

The data obtained from the Plackett–Burman experimental design and the main effects indicated that the tested culture medium components of oatmeal, K2HPO4 and KNO3 must be adjusted to low concentrations (0.15 g/l, 0.025 g/l, and 0.01 g/l, respectively), whereas MgSO4 must be adjusted to a high concentration of 0.04 g/l. In addition, the physiological conditions, temperature and inoculum size must be adjusted at their high tested levels (37 °C and 4 ml/100 ml, respectively), while the pH must be adjusted at a low level (6.0) to obtain maximum antitumor activity. Additionally, test analysis revealed that the significant factors were MgSO4, temperature and inoculum size at the 85% confidence limit. Compared with the basal culture medium, the optimized culture medium led to an increase in antitumor activity of 25.8%, and the anti-optimized medium resulted in a decrease in activity of 12.2% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Verification of the Plackett–Burman experimental results confirmed the antitumor activity of the marine S. albidoflavus strain EgyAB2

| Tested culture medium |

Variable conc. (g/l) | Average anti-tumor activity % |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OM | K2HPO4 | KNO3 | MgSO4 | Temp. °C |

pH | I.S (ml/100 ml) |

||

| Optimized medium | 0.15 | 0.025 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 30 | 6 | 4 | 97.5 |

| Basal medium | 0.3 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 30 | 7 | 2 | 71.7 |

| Anti-optimized medium | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 25 | 8 | 1 | 59.5 |

Extraction of the anticancer agents of the marine S. albidoflavusstrain EgyAB2

The solvent was selected based on its productivity and antitumor activity against the marine strain S. albidoflavus EgyAB2, as determined by the RPD bioassay. The results confirmed that ethyl acetate was the most effective solvent for isolating the bioactive extract, yielding a high dry weight of approximately 200 mg/L and exhibiting an antitumor activity of 93% compared to the other solvents tested. The shape of the obtained crystals was examined by scanning electron microscopy shown previously in (Fig. 2D).

Biotoxicity assay for the marine S. albidoflavusstrain EgyAB2 Ethyl acetate extract

The biotoxicity assay was carried out using Artemia salina as a biomarker. The results indicated that the S. albidoflavusstrain EgyAB2 ethyl acetate extract had a low biotoxicity. The LC50 was 600.23 ppm (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

The biotoxicity curve and the LC50 value of S. albidoflavusstrain EgyAB2ethyl acetate extract viaprobit analysis

Sulfo-rhodamine B (SRB) cytotoxicity assay

According to the obtained data, the S. albidoflavus strain EgyAB2 ethyl acetate extract showed very promising results against the tested breast cancer cell line (MCF-7). The average IC50 value of the three replicates was 0.36 ± 0.15 µg/ml, whereas the average IC50 value of the chemotherapeutic compound 5-FU was 0.35 ± 0.02 µg/ml (Table 3). In addition, the marine S. albidoflavus strain EgyAB2 ethyl acetate extract was subjected to a safety profile test in which normal HSFs were subjected to cell viability rates of 96.66 ± 0.33 and 93.86 ± 0.24 at concentrations of 10 µg/ml and 100 µg/ml, respectively (Table 4).

Table 3.

Cytotoxicity SRB bioassays of the marine S. albidoflavus strain EgyAB2 Ethyl acetate extract according to their IC₅₀ values against a breast cancer cell line (MCF7)

| Sample code | IC₅₀ (HCT116) | IC₅₀ (MCF7) | IC₅₀ (HePG2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. albidoflavus strain EgyAB2 | 2.60 ± 1.00 µg/ml | 0.36 ± 0.15 µg/ml | 6.00 ± 1.20 µg/ml |

| 5-FU | 0.25 ± 0.016 µg/ml | 0.35 ± 0.02 µg/ml | 0.28 ± 0.02 µg/ml |

Table 4.

The safety profile of the tested Ethyl acetate extracts showing IC50 values (µg/ml) against a normal cell line (HSF)

| Compound (Conc.) |

HSF cell viability% treated by S. albidoflavus strain EgyAB2 | SD |

|---|---|---|

| 10 µg/ml | 96.662 | 0.33049 |

| 100 µg/ml | 93.8623 | 0.24683 |

Our results demonstrated that the ethyl acetate extract did not significantly affect the viability of normal cells, even at higher concentrations. These findings indicate a favorable safety margin and suggest that the extract exhibits minimal cytotoxicity toward healthy cells. This selective cytotoxicity supports the potential of the extract as a targeted and selective anticancer therapy, as it appears to preferentially induce cell death in cancer cells while sparing normal tissue. Such selective action is highly desirable in cancer treatment, as it reduces the risk of side effects commonly associated with conventional chemotherapies, which often harm both cancerous and healthy cells alike.

MTT cytotoxicity assay

Through the MTT bioassay of the S. albidoflavusstrain EgyAB2 ethyl acetate extract along MCF7 cell line, the results revealed promising effects on a breast cancer cell line (MCF-7). The IC50 average value of the three replicates was 17.46 ± 0.38 µg/ml after 24 h of treatment (Table 5).

Table 5.

Cytotoxicity assay and detection of the IC50 of the S. albidoflavusstrain EgyAB2 Ethyl acetate extract on MCF7 cells using MTT as a viability dye

| Compound | IC50 (µg/ml) | AVG IC50 | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. albidoflavusEgyAB2 extract | 17.46 | 17.0533 | 0.38 |

| 17 | |||

| 16.70 |

Mode of action of the marine S. albidoflavusstrain EgyAB2 Ethyl acetate extract on MCF7 cells via real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

This assay was performed via the Ct (ΔΔCt) method to quantitatively assess the (mRNA) expression of the TNF-alpha, P53, P21 and BCL2 genes in MCF7 cells after treatment with the S. abidoflavusEgyAB2 ethyl acetate extract. These experiments were performed in triplicate and were independently repeated 3 times (Table 6). Based on our results and previous literature, we hypothesize that the ethyl acetate extract triggers apoptosis through the activation of both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways. The extrinsic pathway may be activated by the upregulation of TNF-alpha, which binds to death receptors on the cell membrane, initiating a signaling cascade that leads to caspase activation and subsequent cell death. Additionally, the intrinsic pathway is likely activated through the upregulation of P53, a key tumor suppressor gene that promotes the release of pro-apoptotic factors from the mitochondria, such as cytochrome c, which activates caspases (including Caspase-3) and induces apoptosis. Concurrently, the downregulation of anti-apoptotic proteins such as BCL2 further promotes cell death by disrupting the mitochondrial membrane potential according to the fold change in targeted gene expression in the extract sample relative to the reference sample, which was normalized to a reference gene, the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene (Fig. 6).

Table 6.

Relative gene expression (ΔΔCT) of the TNF-alpha, P53, P21 and BCL2 genes in MCF7 cells treated with the S. abidoflavus strain EgyAB2 Ethyl acetate extract

| Isolate name extract | TNF-α | P53 | P21 | BCL2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCF7 cells (untreated) | 1.02 ± 0.02 | 1.06 ± 0.09 | 1.05 ± 0.047 | 0.07 ± 0.07 |

| MCF7 cells treated by S. albidoflavus EgyAB2 | 6.9 ± 0.464 | 1.89 ± 0.137 | 0.98 ± 0.04 | 0.01 ± 0.01 |

Fig. 6.

Mode of action of the ethyl acetate extracts of the S. albidoflavus strain EgyAB2 on the different apoptotic genes TNF-α; (A), P53; (B), P21 and BCL2; (D) of the treated MCF7 cell line

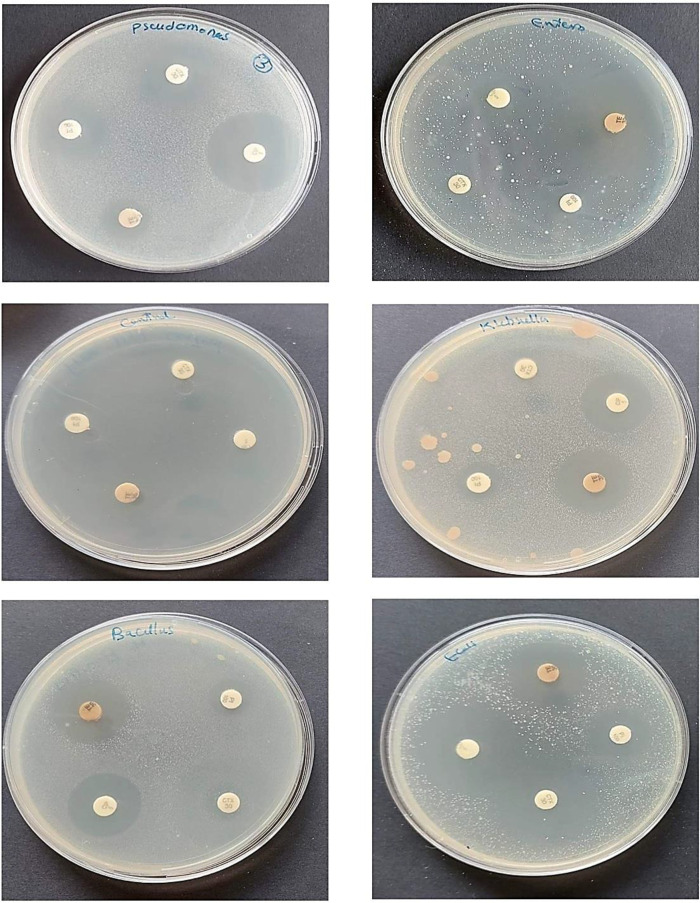

Antimicrobial activity of themarine S. albidoflavusstrain EgyAB2 Ethyl acetate extract

The ethyl acetate extract derived from the actinomycete isolate Streptomyces albidoflavus strain EgyAB2 was diluted to a final concentration of 100 µg/100 µl in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and its antibacterial activity was assessed against ten pathogenic bacteria. One hundred microliters of the final dilution of the extract were added to each well of the pathogenic plates. The plates were incubated at 37 °C overnight, and the zones of inhibition were measured. The results demonstrated no antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bacillus subtilis, Enterococcus faecalis, Vibrio damsela, and Vibrio fluvialis. Additionally, low levels of activity were observed against Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Aeromonas hydrophila, and Streptococcus agalactiae. In contrast, the extract exhibited high activity against the virulent fish pathogenic bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens, with a clear inhibition zone measuring 35 mm. These findings were compared with antimicrobial susceptibility tests conducted using four different commercial antibiotics (Table 7; Figs. 7 and 8).

Table 7.

Antimicrobial sensitivity test of the S. albidoflavus strain EgyAB2 Ethyl acetate Extractagainst the selected pathogens on Meuller Hinton medium and compared with 4 commercial antibiotics

| Pathogen name* | S. albidoflavus EgyAB2 | CIP (5 µg) |

CTX (30 µg) |

TE (30 µg) |

PIP (100 µg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. f | 35 ± 0.11 | 23 ± 0.1 | 21 ± 0.4 | 11 ± 0.08 | 19 ± 0.1 |

| S. a | 13 ± 0.2 | 23 ± 0.2 | 25 ± 0.09 | 21 ± 0.1 | 20 ± 0.2 |

| A. h | 15 ± 0.2 | 34 ± 0.3 | 20 ± 0.1 | - | 19 ± 0.1 |

| E. c | 30 ± 0.2 | 33 ± 0.4 | 20 ± 0.1 | 22 ± 0.08 | |

| K. p | 12 ± 0.15 | 20 ± 0.1 | 11 ± 0.17 | 21 ± 0.23 | 12 ± 0.17 |

*Pathogen names: P.F; Pseudomonas fluorescens, S.a; Staphylococcus aureus, A.h; Aeromonas hydrophila,E.c; Escherichia coli, K.p.; Klebsiella pneumoniae.**Antibiotic names: CIP; ciprofloxacin, CTX; cefatoxime, TE; tetracycline, PIP; PIPeracillin, activity measured as the inhibition zone in mm units

Fig. 7.

Effect of the ethyl acetate extract of the marine S. albidoflavus strain EgyAB2 on the growth of different pathogenic bacteria, indicated positive activity by the inhibition zone on MHA plates

Fig. 8.

The sensitivity test using 4 commercial antibiotics

Antioxidant activity of the marine S. albidoflavusstrain EgyAB2

The antiradical activity was determined on the basis of a reaction with stable diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radicals dissolved in absolute methanol. The reduction of DPPH with an antioxidant decreases the absorbance λ of the solution at 515 nm after incubation for 30 min in the dark. The results revealed high antioxidant activity of the S. albidoflavusstrain EgyAB2 ethyl acetate extract, with an inhibition percentage of 56.08% and an IC50 of 8.92 ± 0.16 µg/ml.

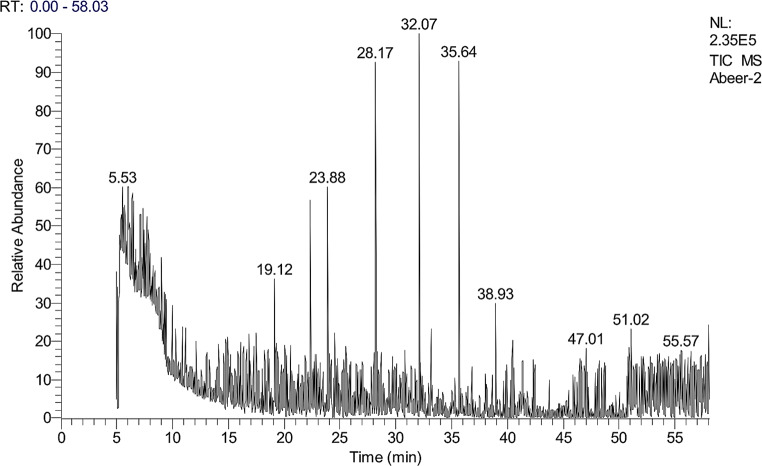

GC–mass spectrometry analysis

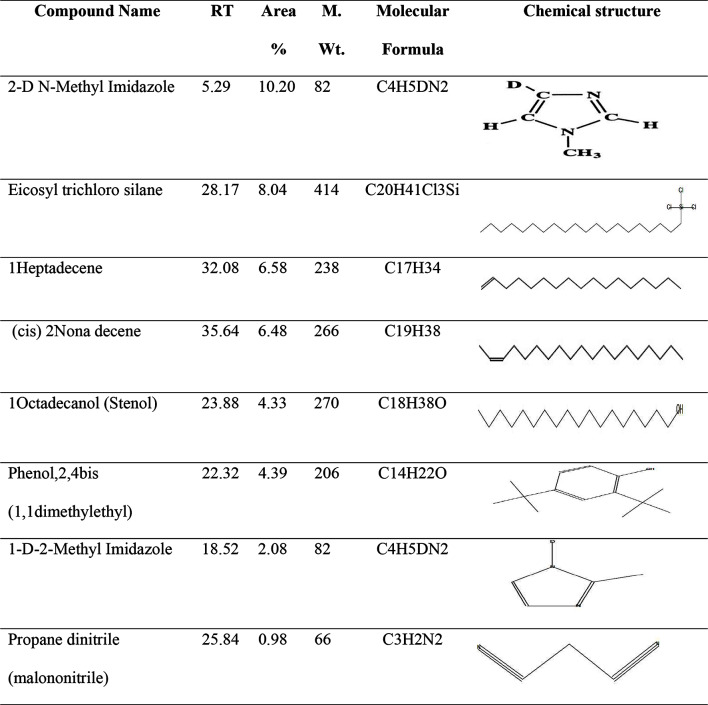

The GC–MS analysis of the ethyl acetate extract from the marine S. albidoflavus strain EgyAB2 resulted in the identification of several chemical constituents present in relatively high percentages (Fig. 9). These included 2-deuteration-N-methylimidazole (10.20%), eicosyl trichlorosilane (8.04%), 1-heptadecene (6.58%), (cis)-2-nonadecene (6.48%), 1-octadecanol (4.33%), phenol, 2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl) (4.39%), 1-D-2-methylimidazole (2.08%), and propane dinitrile (0.98%) (Table 8).

Fig. 9.

Gas chromatography‒mass spectrometry (GC–MS) spectrum of the ethyl acetate extract of the marine S. albidoflavusstrain EgyAB2

Table 8.

The main compounds of the marine S. albidoflavusstrain EgyAB2 Ethyl acetate extract identified using GC–MS

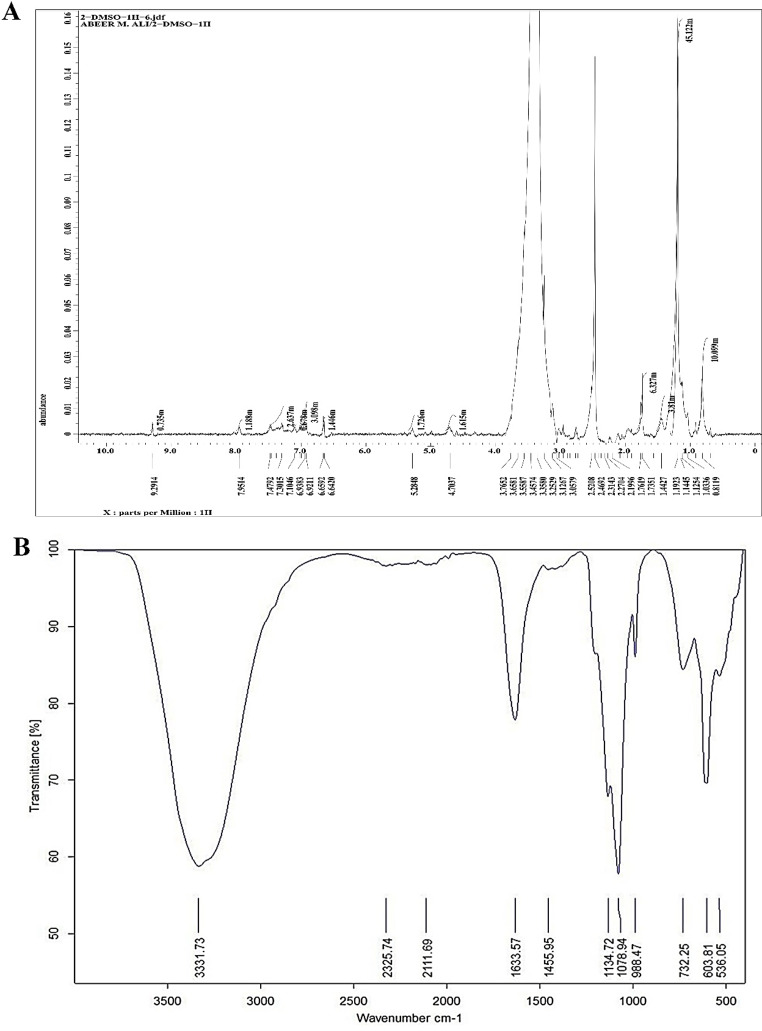

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy analysis

The 1 H-NMR spectrum of the marine S. albidoflavusstrain EgyAB2 ethyl acetate extract revealed various types of proton absorption; the alkyl (methyl) group at (δ) 0.9–1 ppm, the CHα–N (nitro) group at (δ) 2–3 ppm, the amide group at (δ) 5–9 ppm, the CHα–halogen (Cl, Br, I) group at (δ) 2–4 ppm, the alcohol (OH) group at (δ) 0.5–5 ppm and the phenol group at (δ) 4–7 ppm (Fig. 10A).

Fig. 10.

Spectral graphs of the marine S. albidoflavusstrain EgyAB2 ethyl acetate extract; 1 H NMR spectrum (A) and IR spectrum analysis (B)

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy analysis

FTIR analysis of the ethyl extract of the marine S. albidoflavusstrain EgyAB2 revealed a spectrum of 11 peaks. The absorbance values of the isolated extracts ranged from 3331.73 to 536.05 cm− 1. The functional groups were secondary amine (N-H) at 3331.73 cm−¹, alkynes (C–C) at 2111.69 cm-¹, alkenes (C = C) at 1633.57 cm-¹, carboxylic acid (C-O) at 1134.72 cm-¹, secondary alcohol (C-O) at 1078.94 cm-¹, 1,3disubstituted/1,2,4-trisubstituted benzene (C-H) at 988.47 cm-¹, aryl thioether (C-S) at 732.25 cm-¹ and a halo compound (C-Cl) at 536.05 cm-¹ (Fig. 10B).

Discussion

Marine bioactive compounds exhibit a wide range of biological activities, including antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer effects [38]. The marine environment possesses distinct physical and chemical characteristics compared to terrestrial ecosystems, owing to variations in light, temperature, pressure, salinity, and biodiversity. This unique setting is likely to enhance the discovery of new compounds derived from marine resources. Marine-based pharmaceuticals are beginning to influence advanced pharmacology, and distinctive anticancer drugs sourced from marine compounds, such as cytarabine, vidarabine, and nelarabine, have been approved for clinical use [39]. According to Jakubiec-Krzesniaket al. [40]. Actinobacteria represent a major natural source of bioactive compounds, serving as a significant reservoir of novel secondary metabolites for drug development due to their remarkable diversity in chemical structure, biological activity, and pharmacological properties. Among marine Actinomycetes, Streptomyces is an industrially important genus and has been extensively studied for its wide array of bioactive constituents.

In this study, a new marine Streptomyces strain was isolated from a seawater sample and identified as Streptomyces albidoflavus strain EgyAB2, with a new accession number, ON680945.1, via 16 S rRNA gene sequencing. This strain demonstrated a promising effect on the Ti plasmid presented in Agrobacterium tumefaciens, as indicated by the potato disc bioassay. Compared to the negative control with untreated potato discs, the ethyl acetate extract of this marine strain achieved a cell viability of 92.7%. In line with findings by Chowdhury et al. [41]. the antitumour activity of various fractions from plant extracts was evaluated using the potato disc bioassay method, where A. tumefaciens was employed to induce tumours in potato cells. The ethyl acetate fractions of the plant extracts inhibited tumour formation in the tested potato discs by 35.51% and 62.89% when treated with 50 µg/disc and 100 µg/disc, respectively. The safety profile of the S. albidoflavus extract was preliminarily assessed through two complementary assays: (a) the Artemia salina biotoxicity test (LC₅₀ = 600.23 ppm), which aligns with WHO criteria for low toxicity, and (b) SRB assays on normal HSF, where cell viability remained > 93% at concentrations up to 100 µg/ml. While these results suggest favorable biosafety at tested doses, further studies are necessary to evaluate potential side effects or toxicity at higher concentrations (e.g., > 500 µg/ml) and in vivo models. For instance, chronic exposure assays, organ-specific toxicity tests (e.g., hepatic or renal), and genotoxicity evaluations (e.g., comet assay) would provide a more comprehensive safety profile. Conversely, Chowdhury et al. [41]. reported that ethyl acetate extracts from certain plants exhibited a strong lethal effect, with an LC50 value of 11.67 µg/ml in their brine shrimp lethality bioassay.

In this aspect, Ngamcharungchit et al. [42]. discussed the incredible diversity of bioactive metabolites produced by actinomycetes, specifically focusing on advancements in genomic technologies that can help uncover new compounds with significant biological activities, such as antitumor effects. Their review highlights methods of genome mining and co-cultivation to activate silent genes for discovering novel bioactive compounds.

The ethyl acetate extract of the marine S. albidoflavus strain EgyAB2 exhibited notable anti-breast cancer activity, with IC50 values of 0.36 µg/ml according to the SRB bioassay and 17.46 µg/ml according to the MTT bioassay. The anti-breast cancer properties of this marine strain appear promising, particularly in comparison to the results of Sarmiento-Vizcaíno et al. [43]. who investigated the bioactivity of S. albidoflavus across different cell lines. Furthermore, Abd-Ellatif et al. [44]. reported that bioactive compounds from Streptomyces sp. IOPU exhibited anticancer effects on MCF7 cells, with an IC50 of 3.1 µM in an SRB bioassay. Additionally, Dharmaraj et al. [45]. emphasised the potential of marine Streptomyces as sources of bioactive substances, specifically noting their production of antibiotics and anticancer compounds. They highlighted the greater variety of Streptomyces species found in marine environments compared to terrestrial ones and underscored the economic and biotechnological importance of these microorganisms. Multiple recent studies have also highlighted that Streptomyces strains display significant antitumour and various biological activities [46, 47].

The ethyl acetate extract of S. albidoflavus strain EgyAB2 demonstrated potent anti-breast cancer activity against MCF7 cells, with an IC₅₀ of 0.36 µg/ml (SRB assay) and 17.46 µg/ml (MTT assay), outperforming the conventional chemotherapeutic agent 5-FU. Chemical characterization via GC‒MS, 1 H-NMR, and FTIR identified key bioactive constituents, including imidazole derivatives (2-Deuteration-N-methylimidazole, 1-D-2-methylimidazole), long-chain alkenes (1-heptadecene, cis-2-nonadecene), and phenolic compounds (2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)phenol). These compounds are structurally associated with mechanisms critical to anticancer activity: imidazole derivatives disrupt cancer cell metabolism by inhibiting topoisomerases and promoting mitochondrial apoptosis; phenolic compounds induce oxidative stress and caspase activation; while alkenes enhance membrane permeability, potentiating cytotoxic effects. The synergistic interplay of these components likely underpins the extract’s selectivity, as evidenced by > 93% viability in normal HSF and apoptotic gene modulation (6.9-fold ↑TNF-α, 1.89-fold ↑P53, 0.01-fold ↓BCL2). This multi-targeted mechanism contrasts with 5-FU’s non-specific DNA disruption, offering a promising avenue for reducing systemic toxicity. While the crude extract’s efficacy highlights the therapeutic potential of marine-derived metabolites, the interplay of its chemical complexity and bioactivity necessitates deeper exploration to isolate dominant compounds and validate their individual contributions.

So, our results show that the ethyl acetate extract from S. albidoflavus exhibited potent anticancer activity, similar to or exceeding that of 5-FU in terms of inhibiting the growth of MCF7 breast cancer cells. 5-FU, a common chemotherapeutic agent, is known to inhibit DNA synthesis by interfering with the thymidylate synthase enzyme, ultimately leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. However, despite its efficacy, 5-FU is associated with several limitations, including its cytotoxicity to healthy cells, which results in severe side effects such as gastrointestinal disturbances, myelosuppression, and hair loss. This non-specific toxicity remains a major challenge in chemotherapy.

On the other hand, the present results with S. albidoflavus suggest that the bioactive compounds from this marine strain may have a more targeted and selective mechanism of action, likely inducing apoptosis through modulation of key apoptotic and cell cycle regulatory genes (e.g., TNF-alpha, P53, P21 and BCL2), while minimizing damage to normal, healthy cells. Furthermore, compounds from marine organisms are often noted for their ability to target multiple cellular pathways involved in cancer progression, including apoptosis, angiogenesis, and metastasis, offering a potentially more comprehensive therapeutic approach than conventional agents like 5-FU.

Recent studies have highlighted the growing interest in marine-derived compounds as anticancer agents, as they tend to exhibit unique chemical structures and mechanisms of action that differ from those of conventional chemotherapies. For instance, Zhang et al. [48] recent research has demonstrated that marine-derived metabolites can overcome drug resistance, which is often observed with 5-FU and other chemotherapy drugs. Moreover, marine natural products often display lower toxicity to normal cells, which is a significant advantage over traditional chemotherapeutic agents.

The mode of action of the S. albidoflavus strain EgyAB2 ethyl acetate extract on MCF7 cells was investigated using qRT-PCR (Table 4). The ΔΔCT method outlined by Yuan et al. [49]. was employed to assess the induction of apoptosis through the upregulation of the TNF-alpha and P53 genes, alongside the downregulation of the P21 and BCL2 genes. Similar results were reported by Sangour et al. [50]. who observed that treatment of MCF7 and Vero cells with Ag NPs resulted in the upregulation of P53 and P21 gene expression in Vero cells, while their expression was downregulated in MCF7 cells.

Additionally, Khalil et al. [51] focused on bio-synthesized silver nanoparticles (Bio-SNPs) produced by Streptomyces catenulae. The Bio-SNPs exhibited substantial antibacterial effects against multidrug-resistant bacteria, with notable cytotoxicity against human colon cancer cells, emphasising their potential applications in nanomedicine for both antibacterial and anticancer treatments.

On the other hand, the partial chemical characterisation of the ethyl acetate extract from the S. albidoflavus strain EgyAB2, as presented in Table 5, revealed the presence of: 2-Deuteration-N-methylimidazole and 1-D-2-methylimidazole; Imidazole derivatives have been widely studied for their antitumor activities, often through the inhibition of enzymes involved in cancer cell metabolism or proliferation. Some imidazole-based compounds also promote apoptosis in tumor cells. While presence of Eicosyl trichlorosilane; While limited data is available on this specific compound, but organosilicon derivatives have been investigated for their potential anticancer properties due to their membrane-modifying and drug-enhancing effects, especially in combination therapies. And the existence of 1-Heptadecene and (cis)-2-Nonadecene; Long-chain alkenes like these have demonstrated moderate cytotoxic effects in some studies. Their presence may contribute to membrane disruption and influence cell viability. Where 1-Octadecanol; fatty alcohol has been reported to possess anti-inflammatory and anticancer activity. It may play a role in modulating lipid metabolism in cancer cells or enhancing permeability to other active compounds. Phenol, 2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl); this compound is well documented for its antioxidant and cytotoxic effects. It has been shown to induce oxidative stress in tumor cells, leading to apoptosis. Finally the existence of Propane dinitrile; nitrile compounds have shown promise in various pharmacological applications, including anticancer activity, often through alkylating or enzyme-inhibiting mechanisms [52]. Together, the combination of these bioactive metabolites may account for the observed cytotoxic effect of the extract on MCF7 cells. The multi-component nature of the extract likely allows for a synergistic or additive anticancer effect, which warrants further investigation.

Furthermore, Sarmiento-Tovar et al. [53]. investigated pigmented extracts from Streptomyces strains in Colombia, revealing that different growth media significantly influenced pigment production and bioactivity. They identified that anthraquinones and phenazines had notable cytotoxic and antimicrobial properties, suggesting the potential for these pigments in therapeutic applications. The extract also exhibited antioxidant activity, likely due to the presence of 2-nonadecene and 1-hexadecene [54].

Moreover, findings from Tan et al. [55]. presented Streptomyces sp. MUM256, which showed selective cytotoxicity against colon cancer cells, particularly HCT116, in-vitro. The study identified phenolic and pyrrolopyrazine compounds as key components responsible for its antioxidant and anticancer activities, highlighting its potential as a source for the development of chemopreventive agents. The NMR and FTIR analyses of the ethyl acetate extract of the S. albidoflavus strain EgyAB2, depicted in Fig. 7, confirmed the presence of these bioactive compounds through various functional groups, including methyl groups, nitro compounds, amides, amines, halogens, carboxylic acids, alcohol groups, and phenolic groups [56–59]. Additionally, Olanoet al. [60]. reviewed various antitumour compounds derived from marine actinomycetes, noting their mechanisms of inducing apoptosis, such as inhibiting topoisomerases or promoting mitochondrial permeabilization. This review underlines the role of marine actinomycetes in discovering novel lead compounds for cancer therapy. Also, Zhang et al. [61]. reported the isolation of new antimycin analogs from a marine Streptomyces sp., demonstrating their potent cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells. The study highlighted the mechanism by which the most potent compound, NADA, induces apoptosis through the ROS-mediated degradation of oncoproteins E6/E7, providing insights for therapeutic development against HPV-related cancers.

On the other side, recent studies have highlighted the significant anti-cancer potential of certain plant-derived compounds and nanoparticles. One study demonstrated the effective synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) using Zingiber officinale rhizome extract, which exhibited notable antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties. The characterized ZnO-NPs displayed enhanced antimicrobial activity, effectively boosting the performance of various antibiotics against pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Additionally, ZnO-NPs showed promising anti-diabetic and anti-Alzheimer activities by inhibiting key enzymes, alongside demonstrating good biocompatibility with red blood cells [62]. In another investigation, Mentha arvensis extract was evaluated for its pharmacological effects, revealing compounds like luteolin and rosmarinic acid as key bioactive ingredients. This extract exhibited substantial cytotoxic effects on HepG2 cancer cells and strong inhibition of crucial enzymes linked to diabetes and cancer, indicating its potential as a therapeutic agent [63]. Collectively, these studies suggest that plant-based extracts and their nanoparticles may offer a novel approach in cancer treatment and other related diseases, paving the way for advanced therapeutic strategies.

While this study demonstrates the promising anti-breast cancer activity of the marine S. albidoflavus strain EgyAB2, several limitations must be acknowledged. Primarily, the use of GC/MS restricts detection to volatile compounds, which may overlook significant non-volatile bioactive substances. Additionally, the reliance on NMR and FTIR for characterization may lack specificity unless complemented with more advanced techniques such as HPLC or LC/MS/MS. Furthermore, the biological validation conducted so far is preliminary, underscoring the necessity for in vivo studies to fully ascertain the therapeutic potential of these compounds.

Current production of the S. albidoflavus ethyl acetate extract has been performed under laboratory-scale fermentation conditions, which, while satisfactory for preliminary bioactivity screening, do not adequately reflect the complexities related to industrial-scale production. The scalability of this process is influenced by several factors, including culture medium optimization, aeration and agitation control, metabolite yield variability, and batch-to-batch consistency. Furthermore, the extraction method employed using ethyl acetate raises environmental and economic concerns when scaled up, due to solvent toxicity, flammability, and waste disposal challenges.

To advance the potential development of the extract into a regulated therapeutic agent, addressing the following key areas is essential: (a) Purification and structural elucidation of the key active compounds. (b) Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) profiling to understand absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. (c) In vivo toxicity and efficacy studies in appropriate animal models. (d) Standardization and quality control protocols for consistent production. (e) Regulatory pathway planning, including compliance with good manufacturing practice (GMP) and relevant preclinical safety assessments.

Future research should aim to employ a broader range of analytical techniques to achieve a comprehensive characterization of the bioactive compounds present in the extract. Additionally, while qRT-PCR revealed significant modulation of apoptotic genes, further validation through Annexin V/PI staining and cell cycle analysis is warranted to conclusively differentiate between apoptosis and necrosis. These experiments should be prioritized in subsequent studies to enhance mechanistic insights. Conducting extensive in vivo studies will be crucial for validating the anticancer efficacy and elucidating the mechanisms underlying the observed biological activity.

Furthermore, to bridge the gap between in vitro findings and clinical translation, future research will prioritize in vivo validation. Planned studies include evaluating the extract’s efficacy and safety in breast cancer xenograft models (e.g., MCF7 tumor-bearing mice) to assess tumor regression, biodistribution, and systemic toxicity. Concurrently, the most potent bioactive compounds within the extract will be isolated and characterized to elucidate their individual and synergistic contributions to anticancer activity. These efforts will be complemented by pharmacokinetic profiling (e.g., absorption, metabolism, half-life) and histopathological analyses of critical organs (liver, kidneys) to ensure therapeutic selectivity. To align with regulatory requirements, scalable fermentation protocols will be optimized, and GMP compliant production processes will be explored to address challenges in solvent use, batch consistency, and cost-effectiveness.

Together, these steps will significantly advance our understanding of the therapeutic applications of S. albidoflavus-derived compounds in cancer treatment and other areas of pharmacology, establishing a solid foundation for translating the extract from bench to bedside with the long-term goal of developing it as a targeted, natural-origin anticancer drug candidate.

Conclusion

The exploration of bioactive compounds from the marine S. albidoflavus strain EgyAB2 (GenBank accession: ON680945.1) reveals its potential as a source of novel anticancer therapeutics. This strain demonstrated significant efficacy against the MCF7 breast carcinoma cell line, with IC₅₀ values of 0.36 µg/mL (SRB assay) and 17.46 µg/mL (MTT assay), outperforming 5-FU. Importantly, the ethyl acetate extract maintained over 93% viability in normal human skin fibroblasts at 100 µg/mL, suggesting reduced off-target effects. Mechanistic studies indicate that the extract modulates apoptotic pathways, showing increased TNF-alpha and P53 expression, while reducing BCL2 levels. Key bioactive components identified include imidazole derivatives and phenolic compounds, contributing to its multi-targeted action against cancer cells. The extract also exhibited significant antioxidant activity and low biotoxicity, enhancing its therapeutic potential. However, the study’s focus on volatile compounds using techniques like GC-MS and FTIR may overlook non-volatile agents. Future research should employ advanced methods for compound validation and pursue in vivo studies for efficacy assessments. Lastly, this investigation highlights the promise of marine actinomycetes such as S. albidoflavus as valuable sources of novel anticancer agents, laying the groundwork for their development into effective cancer therapies.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2501).

Abbreviations

- M1

Starch nitrate medium

- M2

Starch casein medium

- M3

Potato dextrose medium

- M4

Oatmeal nitrate medium

- OM

oatmeal

- I.S

Inoculum size

- SEM

Scanning electron microscopy

- RPD

Red potato disc bioassay

- SRB

Sulfo Rhodamine B assay

- MTT

dimethyl-thiazol-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide bioassay

- DPPH

Diphenyl-2-picryl hydrazylradical scavenging assay

- LC50

Half-lethal concentration

- ppm

Part per million

- IC50

Half maximal inhibitory concentration

- MCF-7

Breast cancer cell line

- HSF

Human skin fibroblast

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative PCR

- CT

Threshold cycle

- ΔCT

Difference in threshold cycle between the target and reference genes

- ΔΔCT

The difference in ΔCT between the target and reference samples

- 2−ΔΔCT

Relative gene expression

- GC‒MS

gas mass spectrometry

- NMR

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopic analysis

- FTIR

Fouriertransform infrared spectroscopy

Author contributions

A.M.S., M.S.R., F.H., M.M.E., A.A.S., A.S.Y..: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation E.E.H., A.S.Y., A.A.S., S.A.E., M.M.E., S.A.E.: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. All authors reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2501).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript or/and available in the NCBI repository under accession number ON680945.1. You can access the datasets at the following link: [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/ON680945].

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was applicable and approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Alexandria University, with serial number 0306273. All the bacterial pathogens used in this study were obtained from the Egyptian Culture Collection Network.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abir M. Shata and Ahmed A. Saleh contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Manal M. El-Naggar, Email: mmelnaggar@yahoo.com

Ahmed A. Saleh, Email: Elemlak1339@gmail.com

References

- 1.Xiong X, Zheng L-W, Ding Y, Chen Y-F, Cai Y-W, Wang L-P, Huang L, Liu C-C, Shao Z-M, Yu K-D. Breast cancer: pathogenesis and treatments. Signal Transduct Target Therapy. 2025;10(1):49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim J, Harper A, McCormack V, Sung H, Houssami N, Morgan E, Mutebi M, Garvey G, Soerjomataram I, Fidler-Benaoudia MM. Global patterns and trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality across 185 countries. Nat Med 2025:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Yazdani Y, Jalali F, Tahmasbi H, Akbari M, Talebi N, Shahrtash SA, Mobed A, Alem M, Ghazi F, Dadashpour M. Recent advancements in nanomaterial-based biosensors for diagnosis of breast cancer: a comprehensive review. Cancer Cell Int. 2025;25(1):50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azamjah N, Soltan-Zadeh Y, Zayeri F. Global trend of breast cancer mortality rate: a 25-year study. Asian Pac J cancer Prevention: APJCP. 2019;20(7):2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sias F, Zoroddu S, Migheli R, Bagella L. Untangling the role of MYC in sarcomas and its potential as a promising therapeutic target. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(5):1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiri S, Ryba T. Cancer, metastasis, and the epigenome. Mol Cancer. 2024;23(1):154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulze A, Harris AL. How cancer metabolism is tuned for proliferation and vulnerable to disruption. Nature. 2012;491(7424):364–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhara A, Kaur R, Chattopadhyay R, Das S, Pal S, Sen N. Role of apoptosis in cancer: war of the worlds, therapeutic targets and strategies. In: Jana K, editors. Apoptosis and human health: understanding mechanistic and therapeutic potential. Springer, Singapore; 2024. p. 169–205. 10.1007/978-981-97-7905-5_9

- 9.Abotaleb M, Samuel SM, Varghese E, Varghese S, Kubatka P, Liskova A, Büsselberg D. Flavonoids in cancer and apoptosis. Cancers. 2018;11(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shinde P, Banerjee P, Mandhare A. Marine natural products as source of new drugs: A patent review (2015–2018). Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2019;29(4):283–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan MI, Shah S, Faisal S, Gul S, Khan S, Abdullah, … Shah WA. Monotheca buxifolia driven synthesis of zinc oxide nano material its characterization and biomedical applications. Micromachines. 2022;13(5):668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmad M, Tahir M, Hong Z, Zia MA, Rafeeq H, Ahmad MS, Rehman Su, Sun J. Plant and marine-derived natural products: sustainable pathways for future drug discovery and therapeutic development. Front Pharmacol. 2025;15:1497668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Hussaniy HA, Mahan SJ, Redha ZM, AlSaeedi AH, Almukram AMA, Oraibi AI, Abdalrahman MA, Jabbar AA, Al-Ani AAI, Hamed HE. Marine-derived bioactive molecules as modulators of immune pathways: A molecular insight into Pharmacological potential. Pharmacia. 2025;72:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shehata AS, Samy MA, Sobhy SE, Farag AM, El-Sherbiny IM, Saleh AA, Hafez EE, Abdel-Mogib M, Aboul-Ela HM. Isolation and identification of antifungal, antibacterial and nematocide agents from marine bacillus gottheilii MSB1. BMC Biotechnol. 2024;24(1):92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ji R, Zha X, Zhou S. Marine fungi: A prosperous source of novel bioactive natural products. Curr Med Chem. 2025;32(5):992–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osman NA, Mansour FM, Abdulla HM, Koh Y-S, Taher HS. Isolation and characterization of the endophytic actinomycetes from understudied seaweeds: exploring the therapeutic potentials of Streptomyces coelicolor. South Afr J Bot. 2025;179:112–23. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zafar S, Faisal S, Jan H, Ullah R, Rizwan M, Abdullah, … Khattak A. Development of iron nanoparticles (FeNPs) using biomass of enterobacter: its characterization, antimicrobial, anti-Alzheimer’s, and enzyme Inhibition potential. Micromachines. 2022;13(8):1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fonseca AC, Ribeiro I, Girão M, Regueiras A, Urbatzka R, Leão P, Carvalho MF. Actinomycetota isolated from the sponge Hymeniacidon perlevis as a source of novel compounds with Pharmacological applications: diversity, bioactivity screening, and metabolomic analysis. J Appl Microbiol 2025:lxaf044. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Shaaban KA. Marine microbial diversity as source of bioactive compounds. In., vol. 20: MDPI; 2022: 304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Ghareeb A, Fouda A, Kishk RM, El Kazzaz WM. Unlocking the therapeutic potential of bioactive exopolysaccharide produced by marine actinobacterium Streptomyces vinaceusdrappus AMG31: A novel approach to drug development. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;276:133861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel S, Naik L, Rai A, Palit K, Kumar A, Das M, Nayak DK, Dandsena PK, Mishra A, Singh R. Diversity of secondary metabolites from marine Streptomyces with potential anti-tubercular activity: a review. Arch Microbiol. 2025;207(3):1–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Subramani R, Aalbersberg W. Marine actinomycetes: an ongoing source of novel bioactive metabolites. Microbiol Res 2012, 167(10), 571–80. 10.1016/j.micres.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coker PS, Radecke J, Guy C, Camper ND. Potato disc tumor induction assay: A multiple mode of drug action assay. Phytomedicine. 2003;10(2):133–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maillet A, Bouju-Albert A, Roblin S, Vaissié P, Leuillet S, Dousset X, Jaffrès E, Combrisson J, Prévost H. Impact of DNA extraction and sampling methods on bacterial communities monitored by 16S rDNA metabarcoding in cold-smoked salmon and processing plant surfaces. Food Microbiol. 2021;95:103705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Subramani R, Sipkema D. Marine rare actinomycetes: a promising source of structurally diverse and unique novel natural products. Mar Drugs. 2019;17(5):249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santra HK, Maity S, Banerjee D. Production of bioactive compounds with broad spectrum bactericidal action, bio-film Inhibition and antilarval potential by the secondary metabolites of the endophytic fungus cochliobolus sp. APS1 isolated from the Indian medicinal herb Andrographis paniculata. Molecules. 2022;27(5):1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yan L, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Yang H, Qiu G, Wang D, Lian Y. Improvement of tacrolimus production in Streptomyces tsukubaensis by mutagenesis and optimization of fermentation medium using Plackett–Burman design combined with response surface methodology. Biotechnol Lett. 2021;43(9):1765–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pillai SK, Kobayashi K, Michael M, Mathai T, Sivakumar B, Sadasivan P. John William trevan’s concept of median lethal dose (LD50/LC50)–more misused than used. J Pre-Clinical Clin Res 2021, 15(3).

- 29.Skehan P, Storeng R, Scudiero D, Monks A, McMahon J, Vistica D, Warren JT, Bokesch H, Kenney S, Boyd MR. New colorimetric cytotoxicity assay for anticancer-drug screening. JNCI: J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82(13):1107–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fahmy NM, Abdel-Tawab AM. Isolation and characterization of marine sponge–associated Streptomyces sp. NMF6 strain producing secondary metabolite (s) possessing antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticancer, and antiviral activities. J Genetic Eng Biotechnol. 2021;19(1):102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rao X, Huang X, Zhou Z, Lin X. An improvement of the 2ˆ (–delta delta CT) method for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction data analysis. Biostatistics Bioinf Biomathematics. 2013;3(3):71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park S-H, Kim H, Kwak S, Jeong J-H, Lee J, Hwang J-T, Choi H-K, Choi K-C. HDAC3–ERα selectively regulates TNF-α-Induced apoptotic cell death in MCF7 human breast Cancer cells via the p53 signaling pathway. Cells. 2020;9(5):1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurumisawa T, Kawai K, Shinozuka Y. Verification of a simplified disk diffusion method for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of bovine mastitis isolates. Jpn J Vet Res. 2021;69(2):135–43. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brand-Williams W, Cuvelier M-E, Berset C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 1995;28(1):25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar V, Prasher IB. Antimicrobial potential of endophytic fungi isolated from Dillenia indica L. and identification of bioactive molecules produced by fomitopsis meliae (Undrew.) murril. Nat Prod Res. 2022;36(23):6064–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gunawan R, Nandiyanto ABD. How to read and interpret 1H-NMR and 13 C-NMR spectrums. Indonesian J Sci Technol. 2021;6(2):267–98. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishtiaq S, Hanif U, Shaheen S, Bahadur S, Liaqat I, Awan UF, Shahid MG, Shuaib M, Zaman W, Meo M. Antioxidant potential and chemical characterization of bioactive compounds from a medicinal plant Colebrokea oppositifolia Sm. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2020;92(2):e20190387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38..Mandlik DS, Mandlik SK. Marine natural products as a source of novel anticancer agents: a treasure from the ocean. In: Atta-ur-Rahman, editor. Topics in anti-cancer research: volume 10. Bentham Science; 2021. p. 68–99 (32). 10.2174/9789815039290121100007. https://www.eurekaselect.com/chapter/16049.

- 39.Barreca M, Spanò V, Montalbano A, Cueto M, Díaz Marrero AR, Deniz I, Erdoğan A, Lukić Bilela L, Moulin C, Taffin-de-Givenchy E. Marine anticancer agents: an overview with a particular focus on their chemical classes. Mar Drugs. 2020;18(12):619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al-Radadi NS, Hussain T, Faisal S, Shah SAR. Novel biosynthesis, characterization and bio-catalytic potential of green algae (Spirogyra hyalina) mediated silver nanomaterials. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2022;29(1):411–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chowdhury AA, Amran MS, Rana MRH. Antitumor and cytotoxic effect of different partitionates of methanol extract of Trema orientalis: A preliminary in-vitro study. J Ayurveda Integr Med Sci. 2018;3(04):44–50. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ngamcharungchit C, Chaimusik N, Panbangred W, Euanorasetr J, Intra B. Bioactive metabolites from terrestrial and marine actinomycetes. Molecules. 2023;28(15):5915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sarmiento-Vizcaíno A, Braña AF, González V, Nava H, Molina A, Llera E, Fiedler H-P, Rico JM, García-Flórez L, Acuña JL. Atmospheric dispersal of bioactive Streptomyces albidoflavus strains among terrestrial and marine environments. Microb Ecol. 2016;71:375–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abd-Ellatif AE, Abdel‐Razek AS, Hamed A, Soltan MM, Soliman HS, Shaaban M. Bioactive compounds from marine Streptomyces sp.: structure identification and biological activities. Vietnam J Chem. 2019;57(5):628–35. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dharmaraj S. Marine Streptomyces as a novel source of bioactive substances. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;26:2123–39. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arayes MA, Nawar EA, Sabry SA, Mabrouk ME. Bioactive compounds from a haloalkalitolerant Streptomyces sp. EMSM31 isolated from Um-Risha lake in Egypt. Egypt J Aquat Biology Fisheries 2022, 26(2).

- 47.Heo C-S, Kang JS, Kwon J-H, Anh CV, Shin HJ. Pyrrole-containing alkaloids from a marine-derived actinobacterium Streptomyces zhaozhouensis and their antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities. Mar Drugs. 2023;21(3):167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang Y, et al. Marine-derived anticancer compounds: mechanisms and potential applications. Mar Drugs. 2023;21(7):349.37367674 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yuan JS, Wang D, Stewart CN Jr. Statistical methods for efficiency adjusted real-time PCR quantification. In.: Wiley Online Library; 2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Sangour MH, Ali IM, Atwan ZW, Al Ali AAALA. Effect of ag nanoparticles on viability of MCF7 and Vero cell lines and gene expression of apoptotic genes. Egypt J Med Hum Genet. 2021;22:1–11.38624675 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khalil MA, El-Shanshoury AER, Alghamdi MA, Sun J, Ali SS. Streptomyces catenulae as a novel marine actinobacterium mediated silver nanoparticles: characterization, biological activities, and proposed mechanism of antibacterial action. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:833154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Konovalova O, Gergel E, Herhel V. GC-MS analysis of bioactive components of Shepherdia argentea (Pursh.) nutt. From Ukrainian flora. Pharma Innov. 2013;2(6, Part A):7. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sarmiento-Tovar AA, Prada-Rubio SJ, Gonzalez-Ronseria J, Coy-Barrera E, Diaz L. Exploration of the bioactivity of pigmented extracts from Streptomyces strains isolated along the banks of the Guaviare and Arauca rivers (Colombia). Fermentation. 2024;10(10):529. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baliyan S, Mukherjee R, Priyadarshini A, Vibhuti A, Gupta A, Pandey RP, Chang C-M. Determination of antioxidants by DPPH radical scavenging activity and quantitative phytochemical analysis of Ficus religiosa. Molecules. 2022;27(4):1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abdullah, Rahman AU, Faisal S, Almostafa MM, Younis NS, Yahya G. Multifunctional spirogyra-hyalina-mediated barium oxide nanoparticles (BaONPs): synthesis and applications. Molecules. 2023;28(17):6364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nandiyanto ABD, Oktiani R, Ragadhita R. How to read and interpret FTIR spectroscope of organic material. Indonesian J Sci Technol. 2019;4(1):97–118. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Khan IH, Javaid A. Antifungal, antibacterial and antioxidant components of Ethyl acetate extract of Quinoa stem. Plant Prot. 2019;3(3):125–30. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Swantara MD, Rita WS, Suartha N, Agustina KK. Anticancer activities of toxic isolate of Xestospongia testudinaria sponge. Veterinary World. 2019;12(9):1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kumaran S, Uttra V, Thirunavukkarasu R, Nainangu P, Krishnan VG, Renuga PS, Wilson A, Balaraman D. Bioactive metabolites produced from Streptomyces enissocaesilis SSASC10 against fish pathogens. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2020;29:101802. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Olano C, Méndez C, Salas JA. Antitumor compounds from marine actinomycetes. Mar Drugs. 2009;7(2):210–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang W, Che Q, Tan H, Qi X, Li J, Li D, Gu Q, Zhu T, Liu M. Marine Streptomyces sp. derived antimycin analogues suppress HeLa cells via depletion HPV E6/E7 mediated by ROS-dependent ubiquitin–proteasome system. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):42180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Al-Radadi NS, Abdullah, Faisal S, Alotaibi A, Ullah R, Hussain T, Rizwan M, Saira, Zaman N, Iqbal M, Iqbal A, Ali Z. Zingiber officinale driven bioproduction of ZnO nanoparticles and their anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic, anti-Alzheimer, anti-oxidant, and anti-microbial applications. Inorg Chem Commun. 2022;140:109274. 10.1016/j.inoche.2022.109274. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Faisal S, Tariq MH, Ullah R, Zafar S, Rizwan M, Bibi N, Khattak A, Amir N, Abdullah. Exploring the antibacterial, antidiabetic, and anticancer potential of Mentha arvensis extract through in-silico and in-vitro analysis. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2023;23:267. 10.1186/s12906-023-04072-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript or/and available in the NCBI repository under accession number ON680945.1. You can access the datasets at the following link: [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/ON680945].