Abstract

The present study explored for the first time the blood-based proteomic signature that could potentially distinguish older adults with and without cognitive frailty (CF). The participants were recruited under the Malaysian Elders Longitudinal Research (MELoR) study. Cognition and physical frailty were determined using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and Fried’s criteria, respectively. The differential protein expression in the blood samples (38 CF vs 40 robust) were then determined using the Sequential Window Acquisition of All Theoretical Mass Spectra (SWATH) analysis. A total of 294 proteins were found to be differentially expressed in the CF group as opposed to the robust group. Considering proteins with fold change (FC) ≥ ± 2 and p-values < 0.05, 13 proteins were significantly upregulated and nine proteins significantly downregulated in the CF group when compared to the robust group. Subsequent correlation analysis identified nine dysregulated proteins, namely APOA1, APOA2, APOA4, APOC1, APOE, GPX3, RBP4, SERPINC1 and TTR, to exhibit significantly and moderately strong correlations with parameters of cognitive and/or frailty assessments. These proteins could potentially serve as useful proteomic signature of CF given their sensitivity > 78%, specificity > 75%, accuracy > 80% and area under the curve (AUC) > 0.8. The major biological pathways that could be potentially dysregulated by the nine proteins were associated with lipid metabolism and the retinoid system. The present findings warrant further validation in future studies that involve a larger cohort.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11357-024-01462-z.

Keywords: Cognitive frailty, Blood, Proteomic signature, Lipid metabolism, Retinoid system

Introduction

The rapidly ageing global population is attributable to the success in extension of life expectancy since the second half of the twentieth century. This has ironically led to concerns with regard to the increased burden of conditions which are more common in later life, including dementia and frailty. Age-related conditions are associated with increased risk of functional dependency, hospitalisation and mortality, which could in turn lead to increased health expenditure and a reduction in quality of life [1].

Cognitive frailty (CF), which is characterised by the co-occurrence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and physical frailty, is deemed a potential precursor to both dementia and adverse physical outcomes [2]. Since the establishment of the consensus on the criteria that define CF in 2013 [2], the emerging interest in CF has resulted in a growing number of published studies. Nevertheless, this has also led to the identification of potential areas of confusion, suggesting a need to refine the current CF construct [3]. Prior to the development of CF, cognitive impairment and physical frailty are often independently assessed despite their common aetiologies [4]. In fact, conventional cognitive performance assessment tools do not account for motor capacity whilst conventional physical frailty assessment tools do not account for cognitive performance [5].

Although the latest classification has broadened the CF spectrum into reversible CF (RCF) and potentially RCF, the determinants of RCF or asymptomatic preclinical CF remain to be fully elucidated before effective strategies can be identified to delay the onset or progression of cognitive impairment and physical frailty [6]. The need for early diagnosis and early intervention that can delay or reverse CF and thereby promote healthy ageing have led to the search for potential biomarkers. In this regard, several attempts have been made on blood-based biomarker discovery for CF, but they were predominantly based on targeted approach [7–9] except for Kameda, Teruya [10], who identified potential frailty metabolite markers involved in antioxidation, cognition and mobility through untargeted, comprehensive liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) metabolomic analysis. There are also reports on other potential non-invasive biomarkers, including digital gait metrics [5] and neuroimaging [11], which had been explored within the separate constructs of either cognitive impairment or physical frailty. Other efforts of CF biomarker discovery were based on in silico [12] and machine learning [4].

The proteome, which represents the set of proteins in a given time and space with varied composition in different cells or tissues, is increasingly recognised as a reliable source of diagnostic biomarkers for various diseases [13]. The use of proteomic approach in understanding frailty in older adults (general or those presented with specific diseases) has been previously described but often limited only to its physical aspect [14–17]. Given the clinical relevance and reliability of the proteomic approach as well as the lack of untargeted proteomic studies amongst those with CF, the present study explored untargeted potential blood-based proteomic profiles of Malaysian adults aged 55 years and over, with and without CF, through the sequential window acquisition of all theoretical mass spectra (SWATH) analysis.

Methods

Ethics approval and study design

The present study enrolled participants from the Malaysian Elders Longitudinal Research (MELoR) study, which was designed to investigate various dimensions of ageing amongst urban-dwelling older adults in Malaysia. A details of this cohort has been previously described by Alex, Khor [18]. The MELoR study was approved by the University of Malaya Medical Centre Medical Ethics Committee (ethics approval ID: 925.4). Written informed consent was acquired from each participant.

Recruitment of participants and CF assessment

Cognition was assessed using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). Physical frailty was determined using the Fried’s criteria (i.e. weakness (hand grip strength measurement), slowness (gait speed measurement), low physical activity (low physical activity if the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) scores were to fall within the lowest quintile for the study population) and shrinking (body mass index (BMI) < 18.5 or self-reported weight loss of 10 pounds or more in the past year) [19]. Upper limb strength was determined by handgrip strength while lower limb strength and balance were determined by the timed-up and go (TUG) test [20]. The present study has adopted distinct criteria that clearly defined robust and CF individuals. Basically, individuals with MoCA scores ≥ 23 or above and did not fulfill any of the Fried’s criteria were categorised as “robust”, whereas those with MoCA scores < 23 and fulfilled at least three of the Fried’s criteria were classified as “CF”. Individuals who fulfilled three or more of the Fried’s criteria were classified as frail [21]. Psychosocial factors were determined using the 21-item Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) for anxiety and depression, 6-item Lubben’s Social Network Scale (LSNS-6) for social network, Katz scale for basic activities of daily living (ADL) and Lawton scale for instrumental ADL.

Sample preparation

To improve the identification and quantification of low-abundant proteins, the plasma samples of robust (n = 40) and CF (n = 38) participants (Fig. 1) were depleted for albumin using the single-use spin columns of the ITSIPrep Albumin Removal Kits (ITSI Biosciences, PA, USA). Samples were lysed with sodium deoxycholate (1%) in 100 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate and proteins assayed using commercial kits. Briefly, samples were reduced and alkylated in 1 M dithiothreitol (DTT) and 0.5 M iodoacetamide (IAA), respectively. Proteins were trypsin-digested and then cleaned using styrenedivinylbenzene reverse phase sulfonate (SDB-RPS) StageTips (Fischer Scientific, MA, USA). The samples were then loaded and the StageTips were washed twice with 200 μL 0.2% trifluoroacetic acid. Elution from the StageTips was performed using 100 μL 80% acetonitrile and 5% ammonium hydroxide in water. Eluent was dried through vacuum centrifugation and reconstituted in 90 μL 0.1% formic acid in water.

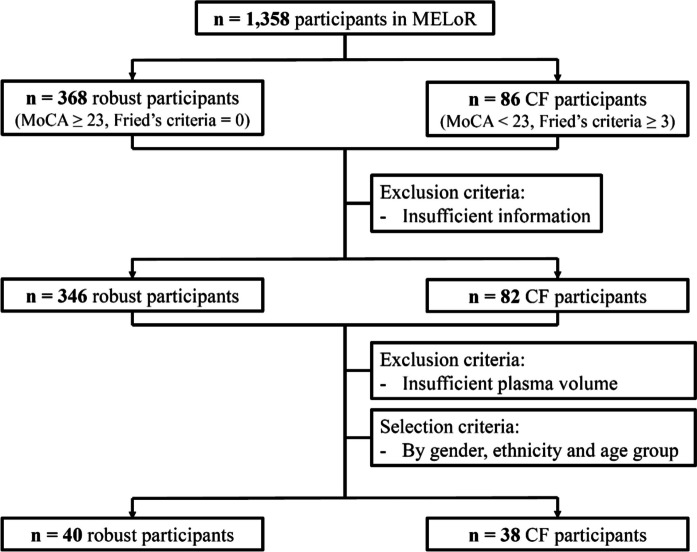

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of participant selection for the present study

High pH reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography

The samples (2 μg each) were pooled for ion library generation through the HpH-RP-HPLC as outlined in a previous study [22]. High pH fractionation was performed and the eluent collected at 2-min intervals at the start of the gradient and at 1-min intervals for the remainder of the gradient. A total of 17 fractions were concatenated, subjected to drying, and reconstituted in 30 μL loading buffer. Subsequently, 10 μL from each fraction was analysed using the two-dimensional information-dependent acquisition (2D-IDA).

Data acquisition

The LC–MS data acquisition was performed using the Triple TOF 6600 (Sciex, Toronto, Canada) with a nano LC system Eksigent Ultra nanoLC system (Eksigent, CA, USA) as described elsewhere [22]. Briefly, each sample (10 μL) was introduced onto a C18 peptide trap (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) for pre-concentration and desalted with loading buffer (0.1% formic acid). The peptide trap transitioned in line with the analytical column, and peptides were eluted. The LC eluent was used in the positive ion nano-flow electrospray analysis. In terms of information dependent acquisition (IDA) mode, a time-of-flight mass spectrometry (TOF–MS) survey scan (m/z 350–1500, 0.25 s) was conducted with subsequent MS/MS analysis for the 20 most intense ions (2+–5+; exceeding 200 counts per s). In terms of data independent acquisition SWATH mode, analysis involved TOF–MS survey scans (m/z 350–1500, 50 ms), followed by MS/MS analysis of 100 predefined m/z ranges were performed. The MS/MS spectra were accumulated for 30 ms in the mass range of 350–1500 m/z.

Data processing and analysis

Protein identification was conducted using the ProteinPilot (v5.0) whilst the Paragon™ algorithm was performed as described elsewhere [22], but with some modifications. UniProt, subset for Homo sapiens, encompassing 26,615 proteins, served as the reference database. The local ion library (353 proteins) and SWATH data were processed using PeakView (v2.2). Parameters included extraction of the top six intense fragments per peptide, a 75 ppm mass tolerance, and a 5-min retention time window. Peptides (≤ 100 per protein) with confidence ≥ 99% and false discovery rate (FDR) ≤ 1% were used for quantitation. SWATH protein peak areas were normalised and subjected to pairwise-relative abundance comparison. Proteins with p < 0.05 and fold change (FC) ≥ ± 2 were deemed as differentially expressed.

Statistical and bioinformatic analyses

The statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism™ version 9.0.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA). The normality of data was determined using the Shapiro–Wilk test. For continuous variables, the significance of differences between demographic parameters of the CF and robust groups was assessed using the independent t-test and Mann–Whitney test for normally and non-normally distributed data, respectively. Categorical variables were compared using the two-sided Fisher’s exact test.

The statistical analyses for correlation, biomarkers and multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) were performed using the R programming language version 4.4.0 (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria). To understand the relationship between protein expression levels and physical assessments with significant differences, the Spearman correlation analysis was performed for each participant using the Hmisc package of R version 4.4.0. A pairwise correlation coefficient of either a positive or negative correlation was interpreted as follows: < 0.3 (poor), 0.3–0.5 (fair), 0.6–0.8 (moderate) and > 0.8 (very strong) [23]. On another note, the biomarker analysis was performed by generating the receiver operating characteristic (ROC), from which the area under the ROC curve (AUC) was derived. The cut-off value of protein abundance was determined using the Youden index [24]. Subsequently, sensitivity, specificity and accuracy were calculated based on the confusion matrix. The MANOVA was performed to assess the impact of age, height, gender, BMI, diabetes, hypertension and CF or robust status on protein expression levels. It was also used to examine the discrimination between CF and robust status on the nine dysregulated protein expression levels after adjusting for gender, height and BMI using linear regression.

The differentially expressed proteins and genes were retrieved from the UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/). The SPRING version 12.0 (https://string-db.org/) was utilised to discern protein–protein interactions, whereas the Reactome pathway browser (https://reactome.org/) was used to identify pathways that are associated with each individual protein and protein subset. The principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical clustering of the participants involved were performed using the MetaboAnalyst version 6.0 (https://www.metaboanalyst.ca/).

Results

Demographic characteristics of participants

CF participants were significantly (p < 0.05) older and of lower height compared to robust participants. They had significantly (p < 0.05) lower haemoglobin and packed cell volume (PCV) compared to their robust counterparts. As expected, the CF participants recorded significantly (p < 0.05) higher total frailty scores (i.e. slower gait speed, lower grip strength, longer TUG test scores, higher dependency, lower MoCA test scores and were more likely to be at risk of social isolation relative to the robust participants) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants

| CD (n = 38) |

Robust (n = 40) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 72.58 ± 9.34 | 63.83 ± 5.67 | < 0.0001 |

| Gender | < 0.9999 | ||

| Male | 19 (50.0%) | 20 (50.0%) | |

| Female | 19 (50.0%) | 20 (50.0%) | |

| Height (cm) | 154.21 ± 7.414 | 161.70 ± 8.20 | < 0.0001 |

| Weight (cm) | 62.16 ± 13.60 | 67.65 ± 11.74 | 0.0641 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.11 ± 5.37 | 25.84 ± 3.94 | 0.7941 |

| Blood and urine test | |||

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 131.62 ± 17.62* | 141.33 ± 14.64 | 0.0067 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 6.48 ± 2.01 | 5.96 ± 1.54 | 0.1469 |

| Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.91 ± 1.23 | 5.07 ± 0.98 | 0.3876 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.47 ± 0.47 | 1.45 ± 0.80 | 0.3354 |

| Total CH/HDL ratio | 3.94 ± 0.90 | 3.69 ± 0.83 | 0.2240 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 43.76 ± 2.23* | 44.80 ± 3.05 | 0.0939 |

| Vitamin_B12 (pmol/L) | 459.21 ± 256.48 | 422.18 ± 169.99 | 0.7242 |

| PCV (L/L) | 0.40 ± 0.05 | 0.43 ± 0.04 | 0.0021 |

| MCV (fL) | 87.16 ± 7.60 | 86.88 ± 7.05 | 0.8555 |

| MCH (pg) | 29.13 ± 2.18 | 28.68 ± 2.65 | 0.5184 |

| MCHC (g/L) | 330.29 ± 10.67 | 328.28 ± 11.96 | 0.4403 |

| RDW (%) | 14.12 ± 1.40 | 13.59 ± 0.85 | 0.1112 |

| Incidence of diseases | |||

| Eye disease | 18 (50.0%)# | 14 (37.84%)^ | 0.3497 |

| Hearing problem | 12 (31.58%) | 10 (25.0%) | 0.6173 |

| Diabetes | 23 (60.53%) | 11 (27.50%) | 0.0058 |

| Hypertension | 27 (71.05%) | 15 (37.50%) | 0.0035 |

| High cholesterol | 23 (60.53%) | 20 (50%) | 0.3724 |

| Respiratory disease | 5 (13.16%) | 4 (10.00%) | 0.7337 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 3 (7.89%) | 1 (2.50%) | 0.3524 |

| Malignancy | 1 (2.63%) | 4 (10.0%) | 0.3593 |

| Cognitive frailty assessment | |||

| Frailty score | 3.32 ± 0.46 | 0 | < 0.0001 |

| Slowness | 34 (89.47%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Weakness | 30 (78.95%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Low Activity | 27 (71.05%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Shrinking | 3 (7.89%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Exhaustion | 32 (84.21%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Unintentional weight loss | 4 (12.5%)$ | 2 (5.41%)^ | 0.4052 |

| Grip strength (kg) | 19.39 ± 6.91 | 29.47 ± 7.51 | < 0.0001 |

| TUG (s) | 16.32 ± 4.57 | 11.03 ± 1.92 | < 0.0001 |

| Gait speed (m/s) | 0.57 ± 0.15 | 0.91 ± 0.14 | < 0.0001 |

| Basic ADL | 5.26 ± 0.50 | 5.18 ± 0.38 | 0.3579 |

| Instrumental ADL | 6.08 ± 1.22 | 6.73 ± 0.59 | 0.0034 |

| MoCA | 14.79 ± 3.84 | 26.50 ± 2.11 | < 0.0001 |

| Depression | 2 (5.26%) | 1 (2.5%) | 0.6104 |

| Anxiety | 2 (5.26%) | 0 (0%) | 0.2341 |

| Social network | 10.89 ± 5.71 | 13.98 ± 3.65 | 0.0198 |

| Medications | |||

| Alimentary tract | 20 (55.56%)# | 24 (60%) | 0.8167 |

| Blood forming | 11 (30.56%)# | 12 (30%) | > 0.9999 |

| Cardiovascular system | 25 (69.44)# | 26 (65%) | 0.8078 |

| Lipid modifying agents | 18 (62.07%)+ | 21 (63.64%)@ | > 0.9999 |

| Statins | 18 (62.07%)+ | 18 (54.55%)@ | 0.6120 |

| Fibrates | 0 (0%)+ | 1 (3.03%)@ | > 0.9999 |

| Omega | 0 (0%)+ | 4 (12.12%)@ | 0.1159 |

| Dermatologicals | 2 (5.56%)# | 0 (0%) | 0.2211 |

| Genito-urinary | 1 (2.78%)# | 2 (5%) | > 0.9999 |

| Hormonal medication | 0 (0%)# | 3 (7.50%) | 0.2421 |

| Antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents | 0 (0%)# | 2 (5%) | 0.4947 |

| Musculoskeletal system | 4 (11.11%)# | 7 (17.50) | 0.5236 |

| Nervous system | 4 (11.11%)# | 0 (0%) | 0.0459 |

| Respiratory system | 1 (2.78%)# | 3 (7.50%) | 0.6170 |

| Sensory organ | 0 (0%)# | 1 (2.50%) | > 0.9999 |

| Health supplements | 1 (2.78%)# | 10 (25%) | 0.0076 |

Each data represents either mean ± standard deviation (SD) or n (%)

Health supplements including “transfer factor, shiitake mushroom, beta glucan, soya bean, olive leaf, zinc, inositol phosphate 6, maitake mushroom, agaricus, cordycep, alpha mannans (aloe vera)”, “tomato powder, psyllium husk, spirulina, seaweed, alfalfa, maltooligosaccharide”, stem cell, saw palmetto, arabic gum, cordyceps, garlic, honey, bee pollen, evening primrose oil, transfer factor, garlic oil, chlorella

BMI, body mass index; CF, cognitive frailty; CH, cholesterol; Frailty15ft, walking speed for 15 feet distance; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; ADL, activities of daily living; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MCH, mean corpuscular haemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; PCV, packed cell volume; RDW, red cell distribution width; TUG, timed-up and go

*Information of one participant (n = 1) was unattainable

#Information of two participants (n = 2) was unattainable

^Information of three participants (n = 3) was unattainable

$Information of six participants (n = 6) was unattainable

@Information of seven participants (n = 7) was unattainable

+Information of nine participants (n = 9) was unattainable

Differential protein expressions between participants of the CF and robust groups

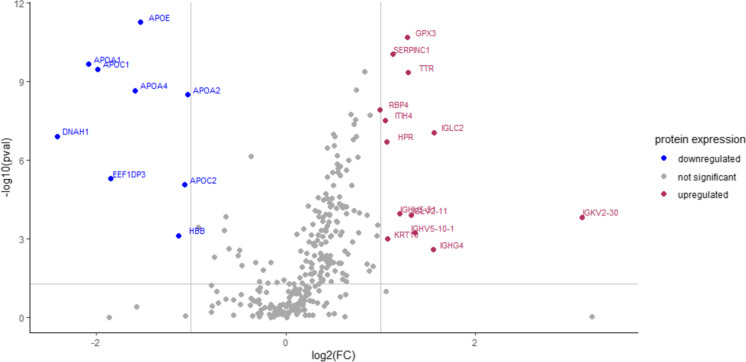

The SWATH analysis has identified a total of 294 proteins that were differentially expressed in the CF group as opposed to the robust group. Considering proteins with FC ≥ ± 2 and p-values < 0.05, 13 proteins were found to be significantly upregulated whereas nine proteins were significantly downregulated in the CF group compared to the robust group (Fig. 2). Table 2 lists both the upregulated and downregulated proteins in the CF group with FC ≥ ± 2 and p-values < 0.05 compared to the robust group (see Table S1 for the list of upregulated and downregulated proteins in the CF group with ± 1.5 ≤ FC < ± 2.0 compared to the robust group). Of the 13 differentially upregulated proteins in the CF group, immunoglobulin kappa variable 2–30 accounted for the highest FC (+ 8.7-fold) compared to the robust group. Of the nine differentially downregulated proteins in the CF group, dynein axonemal heavy chain 1 accounted for the highest FC (− 5.3-fold) compared to the robust group. The MANOVA revealed that gender also significantly influenced the protein expression levels (Table S2). However, the number of men and women in CF and robust groups was equally matched (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Volcano plot of the differentially expressed proteins in the CF group as opposed to the robust group. Proteins were deemed differentially expressed between the CF and robust groups when FC ≥ ± 2 and p < 0.05

Table 2.

List of upregulated and downregulated proteins in the CF group with FC ≥ ± 2 and p < 0.05 when compared to the robust group

| Gene | Uniprot ID | Protein name | FC | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGKV2-30 | P06310 | Immunoglobulin kappa variable 2–30 | 8.7 | 1.48E-04 |

| IGLC2 | P0DOY2 | Immunoglobulin lambda constant 2 | 3.0 | 8.64E-08 |

| IGHG4 | P01861 | Immunoglobulin heavy constant gamma 4 | 2.9 | 2.58E-03 |

| IGHV5-10–1 | A0A0J9YXX1 | Immunoglobulin heavy variable 5–10-1 | 2.6 | 5.95E-04 |

| IGLV2-11 | P01706 | Immunoglobulin lambda variable 2–11 | 2.5 | 1.26E-04 |

| TTR | P02766 | Transthyretin | 2.4 | 4.58E-10 |

| GPX3 | P22352 | Glutathione peroxidase 3 | 2.4 | 2.05E-11 |

| IGHV5-51 | A0A0C4DH38 | Immunoglobulin heavy variable 5–51 | 2.3 | 1.12E-04 |

| SERPINC1 | P01008 | Antithrombin-III | 2.2 | 9.00E-11 |

| KRT10 | P13645 | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 10 | 2.1 | 9.88E-04 |

| HPR | P00739 | Haptoglobin-related protein | 2.1 | 1.96E-07 |

| ITIH4 | Q14624 | Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H4 | 2.1 | 2.97E-08 |

| RBP4 | P02753 | Retinol-binding protein 4 | 2.0 | 1.18E-08 |

| APOA2 | P02652 | Apolipoprotein A-II | − 2.0 | 3.16E-09 |

| APOC2 | P02655 | Apolipoprotein C-II | − 2.1 | 8.45E-06 |

| HBB | P68871 | Haemoglobin subunit beta | − 2.2 | 7.41E-04 |

| APOE | P02649 | Apolipoprotein E | − 2.9 | 5.47E-12 |

| APOA4 | P06727 | Apolipoprotein A-IV | − 3.0 | 2.19E-09 |

| EEF1DP3 | Q658K8 | Putative elongation factor 1-delta-like protein | − 3.6 | 5.03E-06 |

| APOC1 | P02654 | Apolipoprotein C-I | − 4.0 | 3.32E-10 |

| APOA1 | P02647 | Apolipoprotein A-I | − 4.2 | 2.11E-10 |

| DNAH1 | Q9P2D7 | Dynein axonemal heavy chain 1 | − 5.3 | 1.20E-07 |

FC, fold change

Correlations between differentially expressed proteins and CF parameters

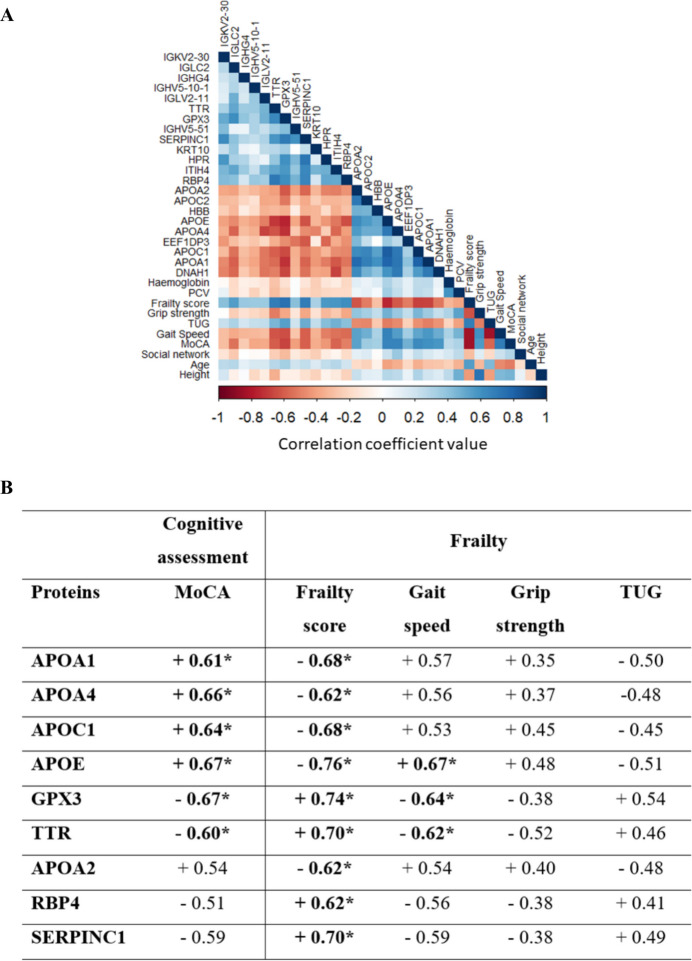

(Fig. 3A depicts the heatmap of differentially expressed proteins and parameters of cognitive and frailty assessments. Considering coefficient correlations ≥ 0.6 and p-values < 0.05, nine proteins exhibited significantly and moderately strong correlations with parameters of cognitive and/or frailty assessments (Fig. 3B). APOA1, APOA4, APOC1, APOE, GPX3 and TTR exhibited moderately strong correlations with parameters of both cognitive and frailty assessments. APOE, GPX3 and TTR, in particular, were correlated to MoCA, frailty score and gait speed. APOA2, RBP4 and SERPINC1 elicited moderately strong correlations with parameters of frailty (i.e. frailty score) but not cognitive assessments.

Fig. 3.

Correlations between differentially expressed proteins (FC ≥ ± 2, p < 0.05) and parameters of cognitive and frailty assessments (significantly different, p < 0.05). A Heatmap of correlation analysis. B List of proteins that exhibited moderately strong correlation (correlation coefficient ≥ 0.60, p < 0.05) with parameters of cognitive and/or frailty assessments. *The coefficient value ≥ 0.60. Abbreviations: PCV, packed cell volume; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; TUG, timed-up and go

Discriminatory strength and biomarker potential of the nine dysregulated proteins that exhibited moderately strong correlation with CF parameters

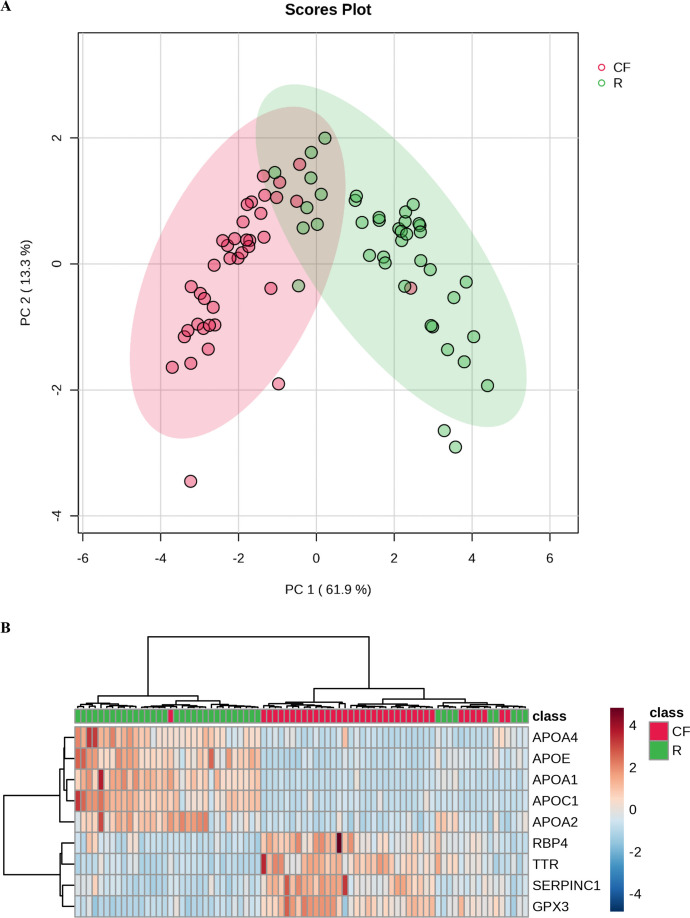

Based on the nine dysregulated proteins that exhibited moderately strong correlation with CF parameters, the PCA plot (Fig. 4A) and hierarchical clustering heatmap (Fig. 4B) indicated a distinct separation between most of the participants in the CF and robust groups.

Fig. 4.

Separation between the CF and robust participants based on the nine dysregulated proteins that exhibited moderately strong correlation with parameters of cognitive and/ or frailty assessments. A PCA plot of the participants. B Hierarchical clustering heatmap that depict the expression trend of the nine dysregulated proteins in each participant. See Fig. S1 for the expression trend of the nine dysregulated proteins in each participant based on diabetes and hypertension incidences.

Subsequent analyses of sensitivity, specificity and accuracy as well as AUC (Table 3 and Fig. S2) revealed that all nine dysregulated proteins yielded sensitivity, specificity and accuracy ranging 78.05–97.22%, 75.51–92.31% and 80.77–92.31%, respectively. Except for APOC1 and RBP4, the proteins yielded both sensitivity and specificity of > 80%. APOA1, in particular, yielded both sensitivity and specificity of ≥ 90%. The ROC analysis indicated that the AUC of the nine dysregulated proteins ranged between 0.88 and 0.95.

Table 3.

Sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of the nine dysregulated proteins (FC ≥ 2, p < 0.05) that exhibited moderately strong correlation (correlation coefficient ≥ 0.60, p < 0.05) with parameters of cognitive and/or frailty assessments. See Table S3 for false positive test on diseases using single and combination of dysregulated proteins (FC ≥ 2, p < 0.05) that exhibited moderately strong correlation (correlation coefficient ≥ 0.60, p < 0.05) with parameters of cognitive and/ or frailty assessments

| Protein | Optimal abundance value cutoff | Sensitivity (%) |

Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) | AUC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APOA1 | 195,731,096.6 | 94.74 | 90.00 | 92.31 | 0.92 (0.84, 1.00) |

| APOA2 | 11,892,998.6 | 87.50 | 86.84 | 87.18 | 0.89 (0.81, 0.97) |

| APOA4 | 24,091,052.3 | 80.95 | 83.33 | 82.05 | 0.89 (0.82, 0.96) |

| APOC1 | 3,561,394.5 | 96.55 | 75.51 | 83.33 | 0.91 (0.86, 0.97) |

| APOE | 6,236,817.4 | 97.22 | 88.10 | 92.31 | 0.95 (0.91, 1.00) |

| GPX3 | 678,282.5 | 89.74 | 92.31 | 91.03 | 0.94 (0.88, 1.00) |

| RBP4 | 11,117,975.4 | 78.05 | 83.78 | 80.77 | 0.88 (0.80, 0.95) |

| SERPINC1 | 31,070,160.2 | 90.91 | 82.22 | 85.90 | 0.93 (0.88, 0.98) |

| TTR | 23,364,280.4 | 87.18 | 89.74 | 88.46 | 0.91 (0.84, 0.98) |

| 3-protein combination# | 94.74 | 95.00 | 94.87 | 0.97 (0.94, 1.00) | |

| 6-protein combination^ | 100 | 93.02 | 96.15 | 0.98 (0.94, 1.00) | |

| 9-protein combination$ | 100 | 93.02 | 96.15 | 0.99 (0.97, 1.00) | |

AUC, area under ROC curve; CI, confidence interval; FC, fold change

#3-protein combination include APOA1, APOE and GPX3; these three proteins exhibited accuracy ≥ 90% in individual biomarker analysis

^6-protein combination include APOA1, APOA4, APOC1, APOE, GPX3 and TTR; these six proteins were correlated (correlation coefficient ≥ 0.6) with both cognitive and physical assessments

$9-protein combination include APOA1, APOA2, APOA4, APOC1, APOE, GPX3, RBP4, SERPINC1 and TTR; these nine proteins were correlated (correlation coefficient ≥ 0.6) with parameters of cognitive and/or frailty assessments

Subsequent MANOVA of the nine dysregulated proteins indicated that, apart from CF or robust status, both gender and height of the participants also significantly affected protein expression levels (Table S4). However, after adjusting for potential confounders (i.e. gender, height and BMI), CF or robust status remained as the significant factor influencing the expression levels of the nine dysregulated proteins (Table S5 and Fig. S3).

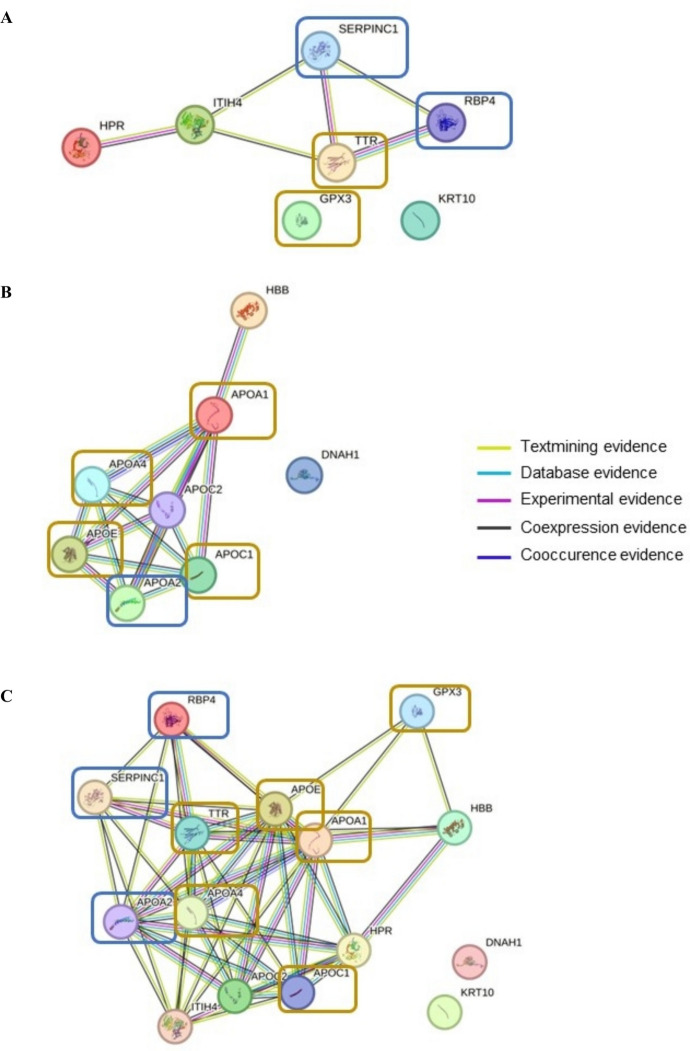

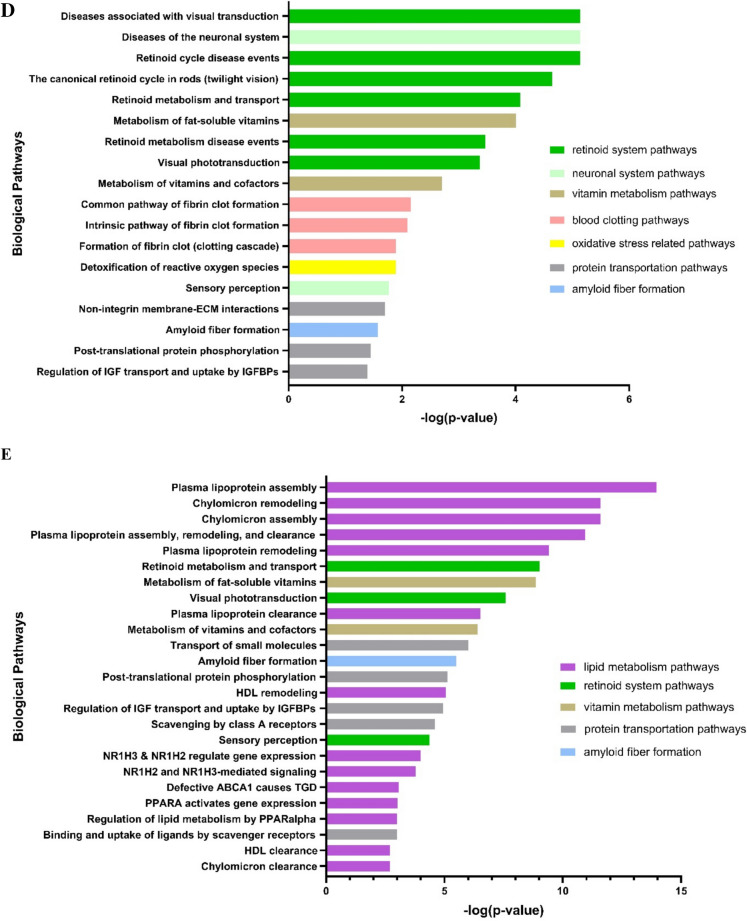

Protein–protein interaction network and pathway enrichment of the nine dysregulated proteins that exhibited moderately strong correlation with CF parameters

(Fig. 5A–C illustrates the protein–protein interaction network of the nine dysregulated proteins that exhibited moderately strong correlation with CF parameters and with the rest of the differentially expressed proteins (FC ≥ ± 2). Considering only the upregulated proteins (Fig. 5A), five differentially expressed proteins showed interaction in the matched PPI networks. Except for GPX3, three (i.e. RBP4, SERPINC1 and TTR) of the nine dysregulated proteins were found to be part of this protein–protein interaction network. SERPINC1 and TTR, in particular, were presented with the highest degree of connectivity. Considering only the downregulated proteins (Fig. 5B), seven differentially expressed proteins showed interaction in the matched PPI networks. Five (i.e. APOA1, APOA2, APOA4, APOC1 and APOE) of the nine dysregulated proteins were all part of the protein–protein interaction network. APOA4, APOC1 and APOE, in particular, were presented with the highest degree of connectivity. Considering both upregulated and downregulated proteins (Fig. 5C), all nine dysregulated proteins were part of the protein–protein interaction network.

Fig. 5.

STRING network of protein–protein interactions (PPI) and potential biological pathways significantly regulated of the identified nine proteins. A PPI of upregulated proteins. B Downregulated proteins. C Combined upregulated and downregulated proteins. Remarks: The proteins highlighted in the coloured box are the nine dysregulated proteins that exhibited moderately strong correlation with frailty (boxes with blue outlines) or both cognition and frailty parameters (boxes with yellow outlines). D Significant pathways involving upregulated proteins. E Significant pathways involving downregulated proteins

(Fig. 5D–E depicts the significantly dysregulated biological pathway. Considering only the upregulated dysregulated proteins (i.e. GPX3, RBP4, SERPINC1 and TTR) (Fig. 5D), a total of 18 biological pathways were significantly affected, of which six were associated with the retinoid system. Other pathways included those related to the neuronal system, vitamin metabolism, blood clotting, oxidative stress, protein transportation and amyloid fiber formation. As for the downregulated proteins (i.e. APOA1, APOA2, APOA4, APOC1 and APOE) (Fig. 5E), of the top 25 biological pathways that were significantly affected, 14 were involved in lipid metabolism. Other pathways included those associated with the retinoid system, vitamin metabolism, protein transportation and amyloid fiber formation.

Discussion

The present study reported, for the first time, the dysregulation of plasma APOA1, APOA2, APOA4, APOC1, APOE, GPX3, RBP4, SERPINC1 and TTR in urban-dwelling Malaysians aged 55 years and over with CF using the SWATH analysis. Six of the nine dysregulated proteins, which included the downregulated APOA1, APOA4, APOC1 and APOE as well as the upregulated GPX3 and TTR in participants with CF, exhibited moderately strong correlations with parameters of both cognitive and frailty assessments. More importantly, the present study found all nine dysregulated proteins to be a potentially useful signature of CF (sensitivity > 78%, specificity > 75%, accuracy > 80% and AUC > 0.8). Six of the nine dysregulated proteins, namely APOA1, APOC1, APOE, GPX3, TTR and SERPINC1, yielded AUC > 0.9, an indication of excellent clinical usability [25].

Interestingly, seven of the nine dysregulated proteins (i.e. APOA1, APOA2, APOA4, APOC1, GPX3, SERPINC1 and TTR) have been reported in previous proteomic profiling studies despite the use of different platforms. Nevertheless, these proteins were previously identified in older adults (different geographical regions) with either MCI or physical frailty but not both conditions. Liu, Austin [17], for instance, reported the association of APOA1 with lower odds of prefrailty in older American adults using the SomaScan platform. Mehta, Mohebbi [26], another example, reported the correlation of APOA1, APOC1 and GPX3 with cognitive function and significant interaction with mood disorders or bone health-related variables amongst cognitively unimpaired older Australian men using the targeted mass spectrometry-based proteomic assay. Song, Poljak [27], yet another example, reported the downregulation of plasma APOA2 and APOA4 but upregulation of plasma TTR in older Australian adults with MCI using the iTRAQ quantitative proteomics. Elsewhere, Lin, Liao [28], found serum SERPINC1 (i.e. antithrombin III), which was upregulated in frail older Chinese adults based on the ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry, to be highly correlated with grip strength. On another note, several previous proteomic studies of either cognitively impaired or frail subjects from other regions (i.e. Australia, Italy, Sweden, Taiwan and the USA) had also identified proteins that were undetected by the present SWATH analysis [14, 16, 17, 26–30]. These variations could be attributed to the different proteomic platforms employed in these previous studies (i.e. LC–MS, proximity extension assay (PEA), SomaScan and nanoflow ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (nUPLC-MS/MS)), which certainly vary in terms of their underlying principles, measurement techniques and the nature of the results produced [31, 32].

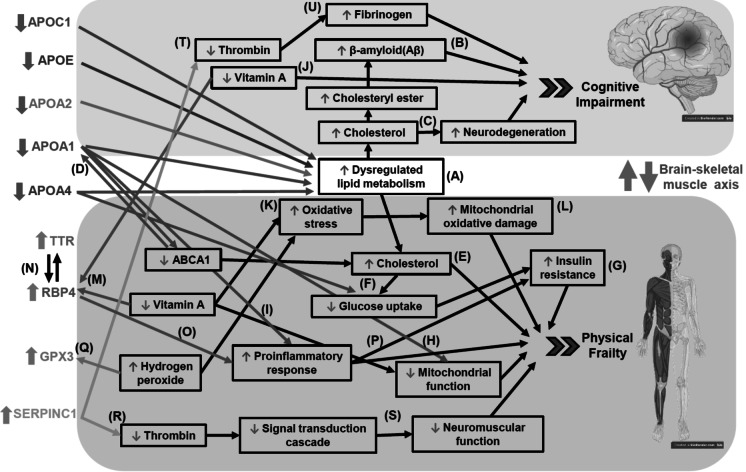

Based on their protein–protein interaction network and pathway enrichment, the present study proposed the potential crosstalk between the nine dysregulated proteins during the pathogenesis of CF via the brain-skeletal muscle axis (Fig. 6). In this regard, the present study has identified lipid metabolism as the key dysregulated biological pathways in older adults with CF given that the said pathway involved five of the nine dysregulated proteins (i.e. the downregulated APOA1, APOA2, APOA4, APOC1 and APOE). This confirmed the previous postulation from a population predictive model developed by Sargent, Nalls [4], whereby CF could be potentially driven by dysregulation across multiple cellular processes, including lipid metabolism. This is also in line with the association between cognitive decline and impaired cholesterol metabolism [33, 34].

Fig. 6.

Proposed pathways that may involve the potential crosstalk between the nine dysregulated proteins during the pathogenesis of CF via the brain-skeletal muscle axis. Remark: Part of this image was created using BioRender (BioRender.com)

In the context of cognitive impairment, the present findings on the downregulated apolipoproteins in older adults with CF were, in general, consistent with previous findings except for APOA2 and APOE, both of which reportedly yielded mixed results. A comparison of older Han Chinese men with normal, mildly impaired and impaired cognitive function, for example, implied that those with a higher level of APOA1 may have a lower risk of cognitive impairment (i.e. APOA1 as a protective factor) whereas those with a higher level of APOA2 may have a higher risk of cognitive impairment (i.e. APOA2 as an adverse factor) [35]. Elsewhere, a community based study in Australia found lower plasma levels of APOA1 and APOA2 but higher levels of APOE in individuals with MCI. Interestingly, lower APOA1 was the most significant predictor of cognitive decline over 2 years in cognitively normal individuals [36]. In fact, a lower level of serum and/ or plasma APOA1 was found to be associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [37, 38]. On the other hand, plasma APOA2 and APOA4 were reportedly downregulated in older Australian adults with MCI [27]. Low levels of serum APOA4 were also found to be associated with the risk of AD [37]. Besides, the causative relationships of apolipoproteins and the central nervous system (CNS) had also been demonstrated in preclinical studies. APOC1 knocked out mice, for instance, were presented with impaired memory function in object recognition [39]. In fact, both the absence [39] and overexpression [40] of APOC1 in mice have been found to impair memory functions, suggestive of an important, bell-shaped gene-dose–dependent role for APOC1 in appropriate brain functioning. On another note, APOE was found to be associated with lifespan and cognitive function in exceptionally long-lived older Australian adults. More specifically, APOE exhibited significant negative associations with global cognition scores in the 56 to 86 age group, whereas positive associations were demonstrated in the 95 to 105 age group [41]. The downregulation of APOE as observed in the present study may be due to ATP-binding cassette A1 (ABCA1) deficiency. It has been reported that APOE secretion is compromised in ABCA1-/- astrocytes and microglia that are characterised by lipid accumulation [42]. Overall, the downregulated apolipoproteins as observed in the present study may have dysregulated lipid metabolism (Fig. 6A), which resulted in excess free cholesterol. The increased free cholesterol could be possibly converted to cholesteryl that would in turn enhance the release of β-amyloid (Aβ) (Fig. 6B) [43]. Furthermore, metabolic dysregulation of cholesterol could also cause neurodegeneration (Fig. 6C) [44].

In the context of physical frailty, the present findings of the downregulated apolipoproteins in participants with CF were also in agreement with previous findings. Older Chinese adults with early sarcopenia, for instance, have reduced level of APOA2 [45]. Basically, apolipoproteins are known to play important roles in lipid metabolism and transportation [46]. APOA1, in particular, would markedly increase the levels of ABCA1 protein whereas ABCA1 would, in turn, stabilise APOA1, thereby activating signalling molecules that modulate posttranslational ABCA1 activity or lipid transport activity (Fig. 6D) [47]. More specifically, ABCA1 is involved in the biogenesis of high-density lipoprotein (HDL), whereby it would mediate the efflux of cholesterol and phospholipids to APOA1. Deficiency of ABCA1 would, however, result in the lack of circulating HDL, which would then greatly reduce APOA1 [42]. This would have, in turn, decreased ABCA1 activity, leading to cholesterol accumulation in the skeletal muscles [48] and consequently, skeletal muscle damage (Fig. 6E) [49]. On another note, APOA1 and APOA4 are also known to aid glucose uptake in skeletal muscle [50, 51]. The downregulation of the apolipoproteins in older adults with CF would have decreased ABCA1 activity, hence impairing insulin signalling [48]. Basically, the lower peripheral glucose uptake by skeletal muscle (Fig. 6F) would cause hyperinsulinaemia and insulin resistance (Fig. 6G), thereby increasing frailty incidence [52]. Furthermore, the downregulation of apolipoproteins, especially APOA1, in older adults with CF may also lead to other complications outside the CNS given its roles in preserving mitochondria function (Fig. 6H) [53] and suppressing inflammation (Fig. 6I) [54].

Additionally, the present study has also identified the retinoid (vitamin A) system as the second key dysregulated biological pathways in older adults with CF given that it involved three of the nine dysregulated proteins (i.e. the upregulated GPX3, RBP4 and TTR). The upregulated TTR, in particular, is in line with previous finding in Australian and Taiwanese MCI subjects [27, 55]. In the CNS, vitamin A is crucial for neuroplasticity and aspects of brain function necessary for cognition [56]. Deficiency of vitamin A was, however, found to be linked to cognitive impairment (Fig. 6J) [57]. It was reported that low serum retinol in older Mexican adults was strongly associated with MCI [58]. Low serum vitamin A has also been found to be significantly correlated with frailty (US participants) [59]. Elsewhere, a preclinical study reported that a consistently inadequate intake of vitamin A would give rise to negative effect on skeletal muscle function [60]. Deficiency of vitamin A could result in oxidative stress (Fig. 6K) and impaired mitochondrial function (Fig. 6L) [61]. Yet another preclinical study of psoriasis mice model implied that a deficiency in vitamin A would have increased circulating RBP4 to mobilise retinol from the liver to target tissues [62]. As such, the present finding of the upregulated RBP4, which is consistent with the higher level of RBP4 found in HIV-infected frail subjects [63], may be a positive feedback mechanism in older adults with CF and vitamin A deficiency (Fig. 6M). This may also explain the present finding of upregulated TTR, which binds to RBP [64] in transporting vitamin A (Fig. 6N) [65].

Apart from its role in transportation of vitamin A, elevation of RBP4 would stimulate pro-inflammatory response (Fig. 6O) and subsequently induce insulin resistance (Fig. 6P) [66]. This would certainly compromise skeletal muscle function which is associated with insulin sensitivity [67, 68]. It was reported that elevation of RBP4 is associated with increased serine 307 phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1), which would reduce its affinity for PI3K and suppress insulin signalling in the muscle [69].

On the other hand, the present finding of upregulated GPX3 may be explained by the previous preclinical study which detected overexpression of GPX3 a protective mechanism against hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-induced oxidative stress in tendons (Fig. 6Q) [70]. Elsewhere, an in vitro study using myoblasts indicated the beneficial effects of GPX3 overexpression on cellular signalling pathways that are typically impaired by ROS [71]. It is also possible that the upregulated GPX3 may coincide with the mobilisation of retinol from the liver to target tissues in older adults with CF and vitamin A deficiency. A preclinical study demonstrated that pretreatment of retinoic acid, a precursor of vitamin A, reduced H₂O₂-induced myoblast death by increasing GPX3 activity in myoblasts, suggesting GPX3 as a retinoic acid target gene [72]. The present finding of upregulated SERPINC1 (i.e. Antithrombin III) is in agreement with a previous report of frail individuals in Taiwan [28]. SERPINC1 would inhibit the activity of thrombin (Fig. 6R) [73] which functions in a signal transduction cascade in skeletal muscle (Fig. 6S) [74]. In the CNS, the inhibition of thrombin (Fig. 6T) would in turn prevent the conversion of fibrinogen into fibrin (Fig. 6U), which may explain the higher level of fibrinogen in MCI groups than non-MCI group [75]. Increased fibrinogen level was associated with an elevated risk of vascular dementia and AD [76].

Strengths and limitations of the study

The present study had adopted SWATH-mass spectrometry (MS), which is a powerful and advanced proteomic technology that permits more precise identification of disease-specific changes in large protein pools [77]. It is suited for biomarker studies, clinical drug/perturbation studies or exploratory basic research [78]. Basically, it consists of data-independent acquisition and a targeted data analysis strategy that aims at maintaining the favourable quantitative characteristics (accuracy, sensitivity and selectivity) of targeted proteomics at large scale. In other words, SWATH-MS has the combined advantages of high reproducibility and sensitivity of targeted methods with the increased proteome depth. SWATH-MS is versatile and has been used in diverse applications (i.e. model organisms, diseases states and bacteria). SWATH-MS has also been useful in characterising of low abundance sub-proteomes including post-translational modifications [79]. More importantly, SWATH-MS studies have shown high intra- and inter-lab reproducibility [80].

A current drawback of SWATH-MS compared to the classical targeted proteomic approaches is that peptide quantification with SWATH-MS is still three- to tenfold less sensitive. A further drawback of SWATH-MS in comparison with data-dependent acquisition-based methods is the required upfront effort on experimental or in silico spectral library and peptide query parameters generation and optimisation [78]. Besides, each sample from the comparison group is run individually in a mass spectrometer for quantitative analysis using SWATH, resulting in inter-run variation, which may influence relative quantification and identification of biomarkers. As such, normalisation of data to diminish this variation becomes an essential step in SWATH data processing [81]. On another note, the method used in the present study indicated abundance of the protein but not the absolute concentration of the protein. Hence, a targeted approach that quantifies the protein level will be useful for future studies.

The present study acknowledged the limitation of a small sample size. There are concerns that smaller samples yield progressively smaller coverage of the expressed proteome [82] which may be influenced by random variation [83]. Besides, small cohorts of complex human samples are associated with inter- and intraindividual variations and systematic effects that may obscure a differential analysis, leading to high false discovery rates and irrelevant results when an improper study design is applied [84]. The uncertainty in the sample variability estimates due to small sample size may give rise to proteins exhibiting a large fold change that are often declared non-significant because of a large sample variance, while at the same time small observed fold changes may be declared statistically significant, because of a small sample variance [85]. Therefore, findings from the study with small samples may not be generalisable to broader population [86]. This warrants validation in a longitudinal study that will involve an independent cohort of a larger sample size to assure high accuracy and reproducibility of the proteomic signature. Besides, proteomic detection of protein expression from small samples can be enriched by pathway analysis followed by targeted proteomics (82).

Conclusion

The present study revealed nine dysregulated proteins (i.e. APOA1, APOA2, APOA4, APOC1, APOE, GPX3, RBP4, SERPINC1 and TTR) which could potentially serve as the proteomic signature of older adults with CF. These interesting findings certainly provide important insights into the pathogenesis of CF that could be associated with lipid metabolism and the retinoid system.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- 2D-IDA

Two-dimensional information-dependent acquisition

- Aβ

β-Amyloid

- ABCA1

ATP-binding cassette A1

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADL

Activities of daily living

- AUC

Area under the curve

- BMI

Body mass index

- CF

Cognitive frailty

- CNS

Central nervous system

- DASS-21

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale

- DTT

Dithiothreitol

- FC

Fold change

- FDR

False discovery rate

- HDL

High-density lipoprotein

- HpH-RP-HPLC

High pH reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography

- IAA

Iodoacetamide

- IDA

Information-dependent acquisition

- IPAQ

International Physical Activity Questionnaire

- IRS-1

Insulin receptor substrate-1

- LC-MS

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

- LSNS-6

Lubben’s Social Network Scale

- MANOVA

Multivariate analysis of variance

- MCI

Mild cognitive impairment

- MELoR

Malaysian Elders Longitudinal Research

- MoCA

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

- nUPLC-MS/MS

Nanoflow ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- PCV

Packed cell volume

- PEA

Proximity extension assay

- RCF

Reversible cognitive frailty

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- SDB-RPS

Styrenedivinylbenzene reverse phase sulfonate

- SWATH

Sequential window acquisition of all theoretical mass spectra

- TOF-MS

Time-of-flight mass spectrometry

- TUG

Timed-up and go

Funding

This Transforming Cognitive Frailty to Later-Life Self-sufficiency (AGELESS) study is funded by the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia under the Long-Term Research Grant Scheme (LRGS/1/2019/UM/01/1/3).

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Panza F, Lozupone M, Solfrizzi V, Sardone R, Dibello V, Di Lena L, et al. Different cognitive frailty models and health- and cognitive-related outcomes in older age: from epidemiology to prevention. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;62(3):993–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelaiditi E, Cesari M, Canevelli M, van Kan GA, Ousset PJ, Gillette-Guyonnet S, et al. Cognitive frailty: rational and definition from an (I.A.N.A./I.A.G.G.) international consensus group. J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17(9):726–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Nader MM, Cosarderelioglu C, Miao E, Whitson H, Xue Q-L, Grodstein F, et al. Navigating and diagnosing cognitive frailty in research and clinical domains. Nat Aging. 2023;3(11):1325–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sargent L, Nalls M, Amella EJ, Slattum PW, Mueller M, Bandinelli S, et al. Shared mechanisms for cognitive impairment and physical frailty: a model for complex systems. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2020;6(1):e12027. 10.1002/trc2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou H, Park C, Shahbazi M, York MK, Kunik ME, Naik AD, et al. Digital biomarkers of cognitive frailty: the value of detailed gait assessment beyond gait speed. Gerontology. 2022;68(2):224–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruan Q, Yu Z, Chen M, Bao Z, Li J, He W. Cognitive frailty, a novel target for the prevention of elderly dependency. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;20:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inglés M, Gambini J, Mas-Bargues C, García-García FJ, Viña J, Borrás C. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor as a marker of cognitive frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(3):450–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MalekRivan NF, Shahar S, Rajab NF, Singh DKA, Din NC, Hazlina M, et al. Cognitive frailty among Malaysian older adults: baseline findings from the LRGS TUA cohort study. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:1343–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valdiglesias V, Sánchez-Flores M, Marcos-Pérez D, Lorenzo-López L, Maseda A, Millán-Calenti JC, et al. Exploring genetic outcomes as frailty biomarkers. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74(2):168–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kameda M, Teruya T, Yanagida M, Kondoh H. Frailty markers comprise blood metabolites involved in antioxidation, cognition, and mobility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(17):9483–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park J, Kim WJ. Potential imaging biomarkers of cognitive frailty. Ann Geriatr Med Res. 2023;27(1):3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dato S, Crocco P, Iannone F, Passarino G, Rose G. Biomarkers of frailty: miRNAs as common signatures of impairment in cognitive and physical domains. Biology (Basel). 2022;11(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Tambor V, Fučíková A, Lenco J, Kacerovský M, Řeháček V, Stulík J, et al. 59. Physiol Res. 2010;4:471–97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Landino K, Tanaka T, Fantoni G, Candia J, Bandinelli S, Ferrucci L. Characterization of the plasma proteomic profile of frailty phenotype. GeroScience. 2021;43:1029–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perry AS, Zhao S, Gajjar P, Murthy VL, Lehallier B, Miller P, et al. Proteomic architecture of frailty across the spectrum of cardiovascular disease. Aging Cell. 2023;22(11):e13978. 10.1111/acel. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sathyan S, Ayers E, Gao T, Milman S, Barzilai N, Verghese J. Plasma proteomic profile of frailty. Aging Cell. 2020;19(9):e13193. 10.1111/acel. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu F, Austin TR, Schrack JA, Chen J, Walston J, Mathias RA, et al. Late-life plasma proteins associated with prevalent and incident frailty: a proteomic analysis. Aging Cell. 2023;22(11):e13975. 10.1111/acel. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alex D, Khor HM, Chin AV, Hairi NN, Othman S, Khoo SPK, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of ethnic differences in fall prevalence in urban dwellers aged 55 years and over in the Malaysian Elders Longitudinal Research study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7):e019579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ong JYQ, Mat S, Kioh SH, Hasmuk K, Saedon N, Mahadzir H, et al. Cognitive frailty and 5-year adverse health-related outcomes for the Malaysian elders longitudinal research (MELoR) study. Eur Geriatr Med. 2022;13(6):1309–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alex D, Khor HM, Chin AV, Hairi NN, Cumming RG, Othman S, et al. Factors associated with falls among urban-dwellers aged 55 years and over in the Malaysian Elders Longitudinal Research (MELoR) Study. Front Public Health. 2020;8:506238. 10.3389/fpubh.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raajendiran A, Krisp C, Souza DP, Ooi G, Burton PR, Taylor RA, et al. Proteome analysis of human adipocytes identifies depot-specific heterogeneity at metabolic control points. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2021;320(6):E1068–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan YH. Biostatistics 104: correlational analysis. Singapore Med J. 2003;44(12):614–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fluss R, Faraggi D, Reiser B. Estimation of the Youden Index and its associated cutoff point. Biom J. 2005;47(4):458–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Çorbacıoğlu ŞK, Aksel G. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis in diagnostic accuracy studies: a guide to interpreting the area under the curve value. Turk J Emerg Med. 2023;23:195–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehta K, Mohebbi M, Pasco JA, Williams LJ, Sui SX, Walder K, et al. A plasma protein signature associated with cognitive function in men without severe cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2023;15(1):148. 10.1186/s13195-023-01294-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song F, Poljak A, Kochan NA, Raftery M, Brodaty H, Smythe GA, et al. Plasma protein profiling of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease using iTRAQ quantitative proteomics. Proteome Sci. 2014;12(1):5. 10.1186/477-5956-12-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin CH, Liao CC, Huang CH, Tung YT, Chang HC, Hsu MC, et al. Proteomics analysis to identify and characterize the biomarkers and physical activities of non-frail and frail older adults. Int J Med Sci. 2017;14(3):231–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanaka T, Lavery R, Varma V, Fantoni G, Colpo M, Thambisetty M, et al. Plasma proteomic signatures predict dementia and cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2020;6(1):e12018. 10.1002/trc2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitchell A, Malmgren L, Bartosch P, McGuigan FE, Akesson KE. Pro-Inflammatory proteins associated with frailty and its progression-a longitudinal study in community-dwelling women. J Bone Miner Res. 2023;38(8):1076–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petrera A, von Toerne C, Behler J, Huth C, Thorand B, Hilgendorff A, et al. Multiplatform approach for plasma proteomics: complementarity of Olink Proximity Extension Assay Technology to Mass Spectrometry-based protein profiling. J Proteome Res. 2021;20(1):751–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katz DH, Robbins JM, Deng S, Tahir UA, Bick AG, Pampana A, et al. Proteomic profiling platforms head to head: leveraging genetics and clinical traits to compare aptamer- and antibody-based methods. Sci Adv. 2022;8(33):eabm5164. 10.1126/sciadv.abm5164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Clark C, Gholam M, Zullo L, Kerksiek A, Castelao E, von Gunten A, et al. Plant sterols and cholesterol metabolism are associated with five-year cognitive decline in the elderly population. iScience. 2023;26(6):106740. 10.1016/j.isci.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Q, Huang S, Cao Y, Dong G, Chen Y, Zhu X, et al. Remnant cholesterol and mild cognitive impairment: a cross-sectional study. Front Aging Neurosci. 2023;15:1069076. 10.3389/fnagi.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma C, Li J, Bao Z, Ruan Q, Yu Z. Serum levels of ApoA1 and ApoA2 are associated with cognitive status in older men. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:481621. 10.1155%2F2015%2F [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Song F, Poljak A, Crawford J, Kochan NA, Wen W, Cameron B, et al. Plasma apolipoprotein levels are associated with cognitive status and decline in a community cohort of older individuals. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e34078. 10.1371/journal.pone.0034078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin Q, Cao Y, Gao J. Decreased expression of the APOA1-APOC3-APOA4 gene cluster is associated with risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:5421–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tong JH, Gong SQ, Zhang YS, Dong JR, Zhong X, Wei MJ, et al. Association of circulating Apolipoprotein AI levels in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:899175. 10.3389/fnagi.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berbée JF, Vanmierlo T, Abildayeva K, Blokland A, Jansen PJ, Lütjohann D, et al. Apolipoprotein CI knock-out mice display impaired memory functions. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;23(4):737–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abildayeva K, Berbée JF, Blokland A, Jansen PJ, Hoek FJ, Meijer O, et al. Human apolipoprotein C-I expression in mice impairs learning and memory functions. J Lipid Res. 2008;49(4):856–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muenchhoff J, Song F, Poljak A, Crawford JD, Mather KA, Kochan NA, et al. Plasma apolipoproteins and physical and cognitive health in very old individuals. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;55:49–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hirsch-Reinshagen V, Zhou S, Burgess BL, Bernier L, McIsaac SA, Chan JY, et al. Deficiency of ABCA1 impairs apolipoprotein E metabolism in brain. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(39):41197–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang D, Wang X, Zhang L, Fang Y, Zheng Q, Liu X, et al. Lipid metabolism and storage in neuroglia: role in brain development and neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Biosci. 2022;12(1):106. 10.1186/s13578-022-00828-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hussain G, Wang J, Rasul A, Anwar H, Imran A, Qasim M, et al. Role of cholesterol and sphingolipids in brain development and neurological diseases. Lipids Health Dis. 2019;18(1):26. 10.1186/s12944-019-0965-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu J, Cao L, Wang J, Wang Y, Hao H, Huang L. Characterization of serum protein expression profiles in the early sarcopenia older adults with low grip strength: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):894. 10.1186%2Fs12891-022-05844-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Boiko AS, Mednova IA, Kornetova EG, Semke AV, Bokhan NA, Loonen AJM, et al. Apolipoprotein serum levels related to metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia. Heliyon. 2019;5(7):e02033. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao G-J, Yin K, Fu Y-C, Tang C-K. The interaction of ApoA-I and ABCA1 triggers signal transduction pathways to mediate efflux of cellular lipids. Mol Med. 2012;18(1):149–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sánchez-Aguilera P, Diaz-Vegas A, Campos C, Quinteros-Waltemath O, Cerda-Kohler H, Barrientos G, et al. Role of ABCA1 on membrane cholesterol content, insulin-dependent Akt phosphorylation and glucose uptake in adult skeletal muscle fibers from mice. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2018;1863(12):1469–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tamilarasan KP, Temmel H, Das SK, Al Zoughbi W, Schauer S, Vesely PW, et al. Skeletal muscle damage and impaired regeneration due to LPL-mediated lipotoxicity. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3(7):e354. 10.1038/cddis.2012.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang S, Tabet F, Cochran BJ, Torres LFC, Wu BJ, Barter PJ, et al. Apolipoprotein A-I enhances insulin-dependent and insulin-independent glucose uptake by skeletal muscle. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1350. 10.038/s41598-018-38014-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Li X, Wang F, Xu M, Howles P, Tso P. ApoA-IV improves insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake in mouse adipocytes via PI3K-Akt Signaling. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41289. 10.1038%2Fsrep [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Peng P-S, Kao T-W, Chang P-K, Chen W-L, Peng P-J, Wu L-W. Association between HOMA-IR and frailty among U.S. middle-aged and elderly population. Sci Rep. 2019;9:4238. 10.1038/s41598-019-40902-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.White CR, Datta G, Giordano S. High-density lipoprotein regulation of mitochondrial function. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;982:407–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tang C, Liu Y, Kessler PS, Vaughan AM, Oram JF. The macrophage cholesterol exporter ABCA1 functions as an anti-inflammatory receptor. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(47):32336–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tien YT, Lee WJ, Liao YC, Wang WF, Jhang KM, Wang SJ, et al. Plasma transthyretin as a predictor of amnestic mild cognitive impairment conversion to dementia. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):18691. 10.1038/s41598-019-55318-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wołoszynowska-Fraser MU, Kouchmeshky A, McCaffery P. Vitamin A and retinoic acid in cognition and cognitive disease. Annu Rev Nutr. 2020;40:247–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mulero J, Zafrilla P, Martinez-Cacha A. Oxidative stress, frailty and cognitive decline. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15(9):756–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.González RP, Cruz-Góngora VDl, Rodríguez AS. Serum retinol levels are associated with cognitive function among community-dwelling older Mexican adults. Nutr Neurosci. 2022;25 9:1881–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Jayanama K, Theou O, Blodgett JM, Cahill L, Rockwood K. Frailty, nutrition-related parameters, and mortality across the adult age spectrum. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):188. 10.1186/s12916-018-1176-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ruiz A, Bachmann C, Franchini M, Benucci S, Zorzato F, Treves S. A low vitamin A diet decreases skeletal muscle performance. J Musculoskelet Disord Treat. 2021;7(096): 10.23937/2572-3243.1510096.

- 61.Chiu HJ, Fischman DA, Hammerling U. Vitamin A depletion causes oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and PARP-1-dependent energy deprivation. FASEB J. 2008;22(11):3878–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang HM, Wu C, Jiang YY, Wang WM, Jin HZ. Retinol and vitamin A metabolites accumulate through RBP4 and STRA6 changes in a psoriasis murine model. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2020;17:5. 10.1186/s12986-019-0423-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Blanco JR, Romero L, Ramalle-Gómara E, Metola L, Ibarra V, Sanz M, et al. Retinol-binding protein 4 (RBP4), a potential biomarker of frailty in HIV-infected people on stable antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med. 2020;21(6):358–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Naylor HM, Newcomer ME. The structure of human retinol-binding protein (RBP) with its carrier protein transthyretin reveals an interaction with the carboxy terminus of RBP. Biochemistry. 1999;38(9):2647–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Raghu P, Sivakumar B. Interactions amongst plasma retinol-binding protein, transthyretin and their ligands: implications in vitamin A homeostasis and transthyretin amyloidosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1703(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moraes-Vieira PM, Yore MM, Sontheimer-Phelps A, Castoldi A, Norseen J, Aryal P, et al. Retinol binding protein 4 primes the NLRP3 inflammasome by signaling through Toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(49):31309–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Srikanthan P, Karlamangla AS. Relative muscle mass is inversely associated with insulin resistance and prediabetes. Findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(9):2898–903. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.Shou J, Chen PJ, Xiao WH. Mechanism of increased risk of insulin resistance in aging skeletal muscle. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2020;12:14. 10.1186/s13098-020-0523-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Flores-Cortez YA, Barragán-Bonilla MI, Mendoza-Bello JM, González-Calixto C, Flores-Alfaro E, Espinoza-Rojo M. Interplay of retinol binding protein 4 with obesity and associated chronic alterations (Review). Mol Med Rep. 2022;26(1):244. 10.3892/mmr.2022.12760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Furuta H, Yamada M, Nagashima T, Matsuda S, Nagayasu K, Shirakawa H, et al. Increased expression of glutathione peroxidase 3 prevents tendinopathy by suppressing oxidative stress. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1137952. 10.3389/fphar.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chung SS, Kim M, Youn BS, Lee NS, Park JW, Lee IK, et al. Glutathione peroxidase 3 mediates the antioxidant effect of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in human skeletal muscle cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(1):20–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.El Haddad M, Jean E, Turki A, Hugon G, Vernus B, Bonnieu A, et al. Glutathione peroxidase 3, a new retinoid target gene, is crucial for human skeletal muscle precursor cell survival. J Cell Sci. 2012;125(Pt 24):6147–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Abildgaard U. Binding of thrombin to antithrombin III. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1969;24(1):23–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lanuza MA, Garcia N, González CM, Santafé MM, Nelson PG, Tomas J. Role and expression of thrombin receptor PAR-1 in muscle cells and neuromuscular junctions during the synapse elimination period in the neonatal rat. J Neurosci Res. 2003;73(1):10–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhuang Y, Huang H, Fu Z, Zhang J, Cai Q. The predictive value of fibrinogen in the occurrence of mild cognitive impairment events in patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy. BMC Endocr Disord. 2022;22(1):267. 10.1186/s12902-022-01185-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.van Oijen M, Witteman JC, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Fibrinogen is associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. Stroke. 2005;36(12):2637–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Park SA, Jung JM, Park JS, Lee JH, Park B, Kim HJ, et al. SWATH-MS analysis of cerebrospinal fluid to generate a robust battery of biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep. 2020;10:7423. 10.1038/s41598-020-64461-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ludwig C, Gillet L, Rosenberger G, Amon S, Collins BC, Aebersold R. Data-independent acquisition-based SWATH-MS for quantitative proteomics: a tutorial. Mol Syst Biol. 2018;14(8):e8126. 10.15252/msb.20178126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Krasny L, Bland P, Kogata N, Wai P, Howard BA, Natrajan RC, et al. SWATH mass spectrometry as a tool for quantitative profiling of the matrisome. J Proteomics. 2018;189:11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Collins BC, Hunter CL, Liu Y, Schilling B, Rosenberger G, Bader SL, et al. Multi-laboratory assessment of reproducibility, qualitative and quantitative performance of SWATH-mass spectrometry. Nat Commun. 2017;8:219. 10.1038/s41467-017-00249-510.1038/s41467-017-00249-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 81.Narasimhan M, Kannan S, Chawade A, Bhattacharjee A, Govekar R. Clinical biomarker discovery by SWATH-MS based label-free quantitative proteomics: impact of criteria for identification of differentiators and data normalization method. J Transl Med. 2019;17:184. 10.1186/s12967-019-1937-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sun J, Zhang GL, Li S, Ivanov AR, Fenyo D, Lisacek F, et al. Pathway analysis and transcriptomics improve protein identification by shotgun proteomics from samples comprising small number of cells - a benchmarking study. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:S1. 10.1186/471-2164-15-S9-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cao Y, Chen RC, Katz AJ. Why is a small sample size not enough? Oncologist. 2024;29(9):761–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Maes E, Cho WC, Baggerman G. Translating clinical proteomics: the importance of study design. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2015;12(3):217–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kammers K, Cole RN, Tiengwe C, Ruczinski I. Detecting significant changes in protein abundance. EuPA Open Proteom. 2015;7:11–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nayak BK. Understanding the relevance of sample size calculation. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2010;58(6):469–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study is available upon request from the corresponding author.