Abstract

Background

Stimulator of interferon (IFN) genes (STING) is a central adaptor protein in the cGAS-STING signaling pathway, orchestrating the production of type I interferons (IFNs) in response to cytosolic DNA detection, a crucial mechanism in antiviral defense. However, further investigation is needed to understand how post-transcriptional regulation, particularly alternative splicing, modulates STING activity.

Methods

We identified a novel alternatively spliced isoform of STING, termed STING-∆N, resulting from exon 3 skipping. We examined STING-∆N expression in various human tissues and cell lines and assessed its role in cGAS-STING signaling using RT-qPCR, luciferase reporter assays, SDD-AGE, immunofluorescence, and immunoblot analysis. We evaluated the influence of STING-∆N on HSV-1 proliferation and STING-induced autophagy by viral plaque assay and immunoblotting. To unravel the mechanistic role of STING-∆N, we further investigated its interaction with STING, TBK1, and 2′3′-cGAMP and its effect on the STING-TBK1 complex using co-immunoprecipitation and 2′3′-cGAMP pull-down assay.

Results

STING-∆N shares an identical C-terminal sequence (aa 121–379) with STING but lacks a 120-amino acid N-terminal region encoding three conserved transmembrane (TM) domains. STING-∆N is expressed in various human tissues and cell lines. STING-∆N significantly suppressed IFN activation induced by cGAS, 2′3′-cGAMP, and STING. STING-∆N also reduced type I and III IFN induction in response to double-stranded DNA, HPV, and HSV-1. Additionally, STING-∆N promoted HSV-1 replication and inhibited STING-induced autophagy. Mechanistically, STING-∆N interacts with 2′3′-cGAMP, STING, and TBK1, sequestering their binding and disrupting the formation of the 2′3′-cGAMP-STING and STING-TBK1 complexes.

Conclusions

STING-∆N acts as a potent negative regulator of the cGAS-STING pathway, revealing a previously unrecognized regulatory mechanism by which alternative splicing modulates immune responses to DNA viruses. These findings suggest that STING-∆N could be a promising therapeutic target for modulating immune responses in viral infections, autoimmune diseases, and cancer.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12964-025-02305-w.

Keywords: cGAS, STING, STING-∆N, Alternative splicing, HPV, Antiviral immunity, Autophagy

Introduction

Nucleic acid sensing is a key innate immune mechanism, serving as the first line of defense against pathogens in eukaryotic cells and mediated by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) across cellular compartments [1–3]. Toll-like receptors (TLRs), including TLR3, TLR7, and TLR9, detect viral RNA and unmethylated CpG DNA in endosomes [3, 4], whereas RIG-I like receptors (RLRs) such as RIG-I and MDA5 recognize viral RNA in the cytoplasm [5]. Additionally, cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) is the primary sensor for cytosolic DNA, activating the cGAS-STING pathway [6–8]. Upon recognizing viral nucleic acids, these receptors trigger signaling cascades that converge at TBK1 and cause the phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of IRF3, lead to the production of type I IFNs and pro-inflammatory cytokines [2, 3].

STING (also known as TMEM173 [9], MITA [10], MPYS, or ERIS [11]) is an essential adaptor protein in cytosolic DNA sensing, which coordinates the production of type I IFN in response to cytosolic DNA [12, 13]. STING is encoded by the TMEM173 gene, which is located on human chromosome 5, and consists of five exons that produce a protein of 379 amino acids (aa). STING is featured by four transmembrane domains (TM) at the N-terminus, followed by a dimerization domain (DD) and a C-terminal cytoplasmic domain (CTD) [9, 14, 15]. The CTD is further composed of a CDN (cyclic dinucleotide)-binding domain (CBD) and a C-terminal tail (CTT). Upon DNA recognition, cGAS undergoes a conformational change that catalyzes the production of 2′3′-cyclic GMP-AMP (2′3′-cGAMP), which acts as an endogenous ligand for STING [15, 16]. In its inactive state, STING resides on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane [15]. Upon activation by 2′3′-cGAMP, STING translocates to the Golgi, where it recruits and activates TBK1 and IRF3, driving the production of type I IFNs and pro-inflammatory cytokines, which are essential for establishing an antiviral state and recruiting immune cells to the site of infection [12].

The cGAS-STING pathway is essential for immune responses against a wide range of DNA and RNA viruses, including herpes simplex virus (HSV), vaccinia virus, and vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) [9, 17]. STING deficiency has been linked to heightened susceptibility to HSV-1 infection because of impaired IFN responses [17]. In response, viruses like coronavirus, HSV-1, hepatitis C virus, and yellow fever virus have evolved mechanisms to evade STING activation, underscoring the pathway’s critical role in antiviral defense [6]. In addition to infectious diseases, the cGAS-STING pathway is also implicated in autoimmune disorders, such as Aicardi-Goutières Syndrome (AGS), STING-associated vasculopathy with onset in infancy (SAVI) [18, 19], and Niemann-Pick disease type C (NPC) [20, 21]. Dysregulated STING activation within neurons can trigger chronic inflammation in the central nervous system (CNS), leading to neurodegeneration [22]. The cGAS-STING pathway also plays a multifaceted role in cancer, affecting processes from malignant cell transformation and immune surveillance to metastasis. This pathway becomes activated by cytosolic DNA accumulation resulting from chromosomal instability, DNA damage, or cellular stress, thereby inducing immune activation through type I IFN and pro-inflammatory cytokine production. The pathway also promotes the recruitment of dendritic cells (DCs), natural killer (NK) cells, and CD8+ T cells into the tumor microenvironment [13, 23]. In cancer immunotherapy, the cGAS-STING pathway is gaining attention for its ability to enhance antitumor immunity. STING agonists, including nucleotide-based molecules (e.g., ADU-S100, MK-1454) and non-nucleotide small molecules (e.g., MSA-2, SR-717), have shown promising outcomes, particularly in combination with immune checkpoint blockade therapies [24, 25].

Given its pivotal role in host defense and immune homeostasis, its activity must be precisely regulated to prevent excessive IFN production and inflammatory responses [26]. A critical regulatory mechanism of STING is post-translational modification (PTM), encompassing processes such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination, palmitoylation, and acetylation [27]. Other regulatory mechanisms include protein–protein interactions, transcriptional regulation, subcellular compartmentalization, and alternative splicing [14]. Alternative splicing has particularly emerged as an essential regulatory strategy within IFN signaling pathways. Numerous isoforms of key IFN signaling molecules, such as RIG-I, MAVS, TBK1, and IRF3 have been identified, with many functioning as dominant-negative regulators [28]. To date, researchers have computationally predicted and experimentally identified several STING isoforms [29–32]. For instance, MITA-related protein (MRP), a STING isoform lacking exon 7, acts as a dominant negative regulator by disrupting STING-TBK1 complex formation [32]. In previous work, we identified STING-β, an N-terminus truncated protein of STING that impairs 2′3′-cGAMP binding and STING-TBK1 interactions, resulting in weakened IFN responses [29]. Together, these studies underscore alternative splicing as a crucial regulatory mechanism in STING activation.

The canonical human STING gene is composed of 8 exons and 7 introns, which encode corresponding key structural and functional domains of STING, including four transmembrane domains (TM), a dimerization domain (DD), and a C-terminal domain (CTD). STING-∆N lacks exon 3 which encodes 1 to 3 N-terminal transmembrane domains, while the C-terminal domain remains intact. However, STING-β is transcribed from an alternative promoter located within intron 6, yielding an isoform with a distinct N-terminus without 1 to 4 TM domains with intact STING CTD. Despite substantial progress in understanding STING-mediated immune responses, the regulatory role of alternative splicing in regulating these pathways remains underexplored. This study addresses this gap by elucidating how STING-∆N modulates STING signaling at the post-transcriptional level. Our findings not only advance our understanding of the cGAS-STING pathway but also suggest new therapeutic strategies for modulating immune responses in autoimmune diseases and chronic viral infections.

Material and methods

Cell culture and transfection

HEK293T, HEK293TT, HEK293, MRC5, LX-2, MDA-231, IMR90, WI38, HeLa, MIHA, Vero, HepG2, and Hep3B were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Gibco) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco) and 1 × Penicillin–Streptomycin solution (Gibco). THP-1, Jurkat, MT2, Hut102, CEM-T4, and HCT116 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Gibco) with 10% FBS and 1 × Penicillin–Streptomycin solution. U2OS cells were cultured in McCoy’s 5 A medium (Gibco) with 10% FBS and 1 × Penicillin–Streptomycin solution (Gibco), and A549 cells were cultured in F-12 K medium (Gibco). All cells were incubated in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

HEK293T cells were transfected using Polyethylenimine “Max” (Polysciences, Inc) at a DNA-to-reagent ratio of 1:3 (1 µg DNA to 3 µL PEI) in 6-well plates (1 µg DNA per well). HeLa cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol with a DNA-to-reagent ratio of 1:2.5 (1 µg DNA to 2.5 µL Lipofectamine 3000) in 6-well plates. Transfections with siRNAs, HSV-1-60mer (dsDNA), calf thymus genomic DNA (CT-DNA, Solarbio), and 2′3′-cGAMP (InvivoGen) were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Plasmids

Luciferase reporter plasmids pIFN-β-Luc, pISRE-Luc, and pIRF3-Luc, as previously described, were used to measure IFN-β, ISRE, and IRF3 promoter activity [29]. pRL-TK Renilla luciferase reporter was used as an internal control. Expression plasmids for cGAS, STING, and TBK1 various tags were constructed as previously reported [33]. The STING-∆N DNA sequence was amplified from a THP-1 cDNA and cloned into pXJ2 vector. Sequence orientation and accuracy were confirmed via sequencing. For co-localization experiments, mitochondrial, ER, and Golgi markers (pDsRed2-Mito, pDsRed2-ER, pEYFP-Golgi) were used. Primer sequences used in this study were listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Reagents and antibodies

cDNA templates from various human tissues, specifically the Human MTC™ Panel I, were obtained from Clontech. Calf thymus genomic DNA powder (CT-DNA) was purchased from Solarbio. 2′3′-cGAMP was purchased from InvivoGen. Transfection reagents, including Lipofectamine 3000 and Lipofectamine 2000, were purchased from Invitrogen. Polyethylenimine “Max” was ordered from Polysciences. The following primary antibodies were purchased commercially: mouse anti-Flag M2 (Sigma), mouse anti-HA (26D11, Abmart), mouse anti-Myc (19C2, Abmart), mouse anti-β-tubulin (2P2, Abmart), mouse anti-LaminB1 (AB0054, Abways), mouse anti-LC3B (T55992F, Abmart), rabbit anti-IRF3 (CY5779, Abways), rabbit anti-TBK1 (CY5145, Abways), rabbit anti-STING (198511-AP, Proteintech), rabbit anti-pIRF3 (4D4G, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-pTBK1 (D52C2, Cell Signaling Technology), and rabbit anti-pSTING (E9A9K, Cell Signaling Technology). Peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse secondary Ab (AB0102) and anti-rabbit secondary Ab (AB1010) were purchased from Abways. Fluorescence secondary antibodies, including Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG, Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit IgG, Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG, and Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-mouse IgG were purchased from Beyotime. The anti-HA agarose beads and anti-Flag magnetic beads were purchased from Abmart.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR)

Cells were harvested at specified time points, and total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. One microgram of total RNA underwent genomic DNA digestion, followed by reverse transcription into cDNA using the HiScript III 1 st Strand cDNA Synthesis kit with gDNA wiper (Vazyme). RT-qPCR was conducted using a SYBR Green-based RT-qPCR kit, UltraSYBR Mixture (CWBIO), on thermocycler (Roche LightCycler96). Primer sequences for target gene quantification are provided in Supplementary Table S1. Data analysis was performed using the comparative CT method (ΔΔCT method).

RNA interference

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting STING-∆N and the control siRNA (Scramble) were designed as described in our previously described [29] and were ordered from GenePharma [29]. siRNAs were employed to knockdown STING-∆N in THP-1 cells via transfection with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), following the manufacturer’s instructions as previously described [29]. The knockdown efficiency was confirmed by RT-qPCR and immunoblot analysis. The siRNA sequences are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

Luciferase reporter assay

Luciferase reporter assays were conducted with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit (Vazyme), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, HEK293T cells (approximately 1 × 105 cells/well in 48-well plates) were transfected with an IFN-β, ISRE, or IRF3 luciferase reporter plasmid (firefly luciferase driven by the IFN-β, ISRE, IRF3 promoter respectively), an internal control Renilla luciferase plasmid (pRL-TK), and the relevant expression plasmids of signaling molecules for each experiment. Thirty-six hours post-transfection, cells were lysed with passive lysis buffer (25 mM Tris–phosphate (pH 7.8), 2 mM DTT, 2 mM 1,2-diaminocyclohexane N,N,N´,N´-tetraacetic acid, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton® X-100), and luciferase activity was quantified using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit on a 96-well automated luminometer (Roche). Data were normalized to Renilla luciferase activity.

Immunoblot analysis and co-immunoprecipitation

Immunoblot analysis and co-immunoprecipitation were performed following the protocols outlined in our previous publication [29]. For immunoblot analysis, cells were lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris‐HCl (pH 7.4), 50 mM EDTA, 1.0% NP‐40, and 150 mM NaCl, with protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma) and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma). Lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant were collected. Protein concentrations in cell lysates were measured using the BCA assay kit (Pierce). Cell lysates were supplemented with 5 × SDS loading buffer and boiled at 100 °C for 10 min. Proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore, #IPFL00010) using a wet transfer system at 100 V for 1 h. Membranes were blocked with 5% (wt/vol) non‐fat milk at room temperature for 2 h, then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were washed multiple times (5 min per wash) and incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Beyotime) at room temperature for 1 h, followed by detection with the SuperSignal Chemiluminescent ECL reagent kit (Beyotime). For co-immunoprecipitation, cell lysates were incubated with anti-HA agarose beads (Abmart) or anti-Flag agarose beads (Abmart) at 4 °C overnight. Beads were washed five times with 1 mL lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40), and bound proteins were eluted by boiling the beads in 2 × SDS loading buffer at 100 °C for 10 min.

Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation

The fractionation of nuclear and cytoplasmic protein was performed using a Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction Kit (P0027, Beyotime). Briefly, cells were collected, washed, and lysed in cytoplasmic extract reagent A (P0027-1), supplemented with a protease inhibitor mixture, on ice for 15 min with intermittently mixing. The cell lysates were then supplemented with cytoplasmic extract reagent B (P0027-2), followed by vortex for 5 s. After 5 min of incubation, the cell lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 × g at 4 °C for 15 min. The supernatant was collected as the cytoplasmic extract. The pellets were resuspended in nuclear extract reagent (P0027-3) on ice for 30 min with intermittent vortexing. The nuclear lysates were centrifuged again at 13,000 × g at 4 °C for 15 min, and the supernatant was collected as the nuclear extract.

Semi-denaturing detergent agarose gel electrophoresis (SDD-AGE)

SDD-AGE was conducted following protocols in our previous study [29]. Briefly, cells were lysed on ice for 20 min in a non-denaturing buffer containing 0.5% Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% glycerol, and a protease inhibitor cocktail. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 × g at 4 °C for 15 min, then mixed with 5 × sample loading buffer containing 2.5 × TBE, 2.5% SDS, 25% glycerol, and 0.25% bromophenol blue. Proteins were electrophoresed on a vertical 2% agarose gel in running buffer containing 0.5 × TBE and 0.1% SDS, and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore) at 4 °C. Immunoblot analysis of the membranes was conducted as mentioned above.

Immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy

Cells were seeded on poly-L-lysine (Sigma) coated coverslips, washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBST, blocked with blocking reagent (Beyotime) at room temperature, and incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. The following day, cells were gently washed and incubated with fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. Coverslip was then mounted using mounting medium with DAPI (Beyotime). Images were captured using a Zeiss LSM880 confocal microscope, and image data were processed with the ImageJ software.

Viruses and infection

HSV-1, as used in our previous publications, was propagated and titrated in Vero cells [29, 33]. In this study, THP-1 cells were infected with HSV-1. THP-1 cells were plated 24 h prior to transfection, washed with PBS, and infected with HSV-1 for 1 h. After infection, supernatants were aspirated and replaced with complete medium containing 10% FBS. Infectious HPV16 virions were generated using a transient-transfection-based method, as described in previous publications [34]. Briefly, HEK 293TT cells were plated in 10-cm dishes one day before transfection, transfected with plasmids encoding HPV16 L1 and L2 capsid proteins along with the HPV16 genome using Lipofectamine 2000, and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. After incubation, cells were harvested, lysed in a custom lysis buffer, and concentrated using the PEG8000 method. Packaged virions were then used to infect HeLa cells in this study.

Viral plaque assay

HSV-1 titers were determined by virus plaque assay on Vero cells. Briefly, Vero cells were seeded in a 24-well plate to reach 90% confluency at the time of infection. HSV-1 was serially diluted in serum-free medium. Cells were washed and infected with the HSV-1 containing medium for 1 h. Following infection, the medium was discarded, and cells were overlaid with 0.5% agar in DMEM containing 2% FBS. After agar solidification, cells were cultured for 48 h. Supernatants were removed, and cells were fixed with methanol/ethanol for 30 min. Solid agar was then removed, and cells were stained with 0.05% crystal violet for 15 min. Wells were rinsed with water, and viral plaques were counted and calculated as PFU/mL.

cGAMP pull-down assay

The cGAMP pull-down assay was performed using 2′3′-cGAMP-agarose (Biolog), following protocols from a previous publication [18]. Briefly, clarified cell lysates were incubated with pre-washed 2′3′-cGAMP-agarose or control agarose at 4 °C for 2 h, then washed multiple times with PBS containing 100 μM ATP to reduce non-specific binding. Agarose was then resuspended in 2 × SDS loading buffer and analyzed by immunoblot analysis or silver staining.

Silver staining

Silver staining was conducted following SDS-PAGE as described in previous publications [29], with the steps outlined below. Fixation: The gel was fixed in 50% methanol and 12% acetic acid for 1 h, then washed with 35% ethanol three times for 20 min and rinsed with deionized water three times for 15 min. Sensitizing: The gel was incubated in 0.02% sodium thiosulfate for 2 min, followed by three washes in deionized water for 10 min each. After electrophoresis, gels were again fixed in 50% methanol and 12% acetic acid for 1 h, washed with 35% ethanol three times for 20 min, and with deionized water three times for 15 min, and sensitized with 0.02% sodium thiosulfate for 2 min, followed by deionized water washes. Staining: Gels were stained in 0.2% silver nitrate and 0.05% formalin for 20 min, rinsed with deionized water for 1 min, developed in 6% sodium carbonate, 0.05% formalin, and 0.0004% sodium thiosulfate, and then stopped with 50% methanol and 12% acetic acid for 5 min.

Statistics

Comparisons between groups were analyzed with a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test in GraphPad Prism 8. Data were presented as the mean ± SD. A p value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

STING-∆N is a novel splicing isoform of STING generated by exon skipping

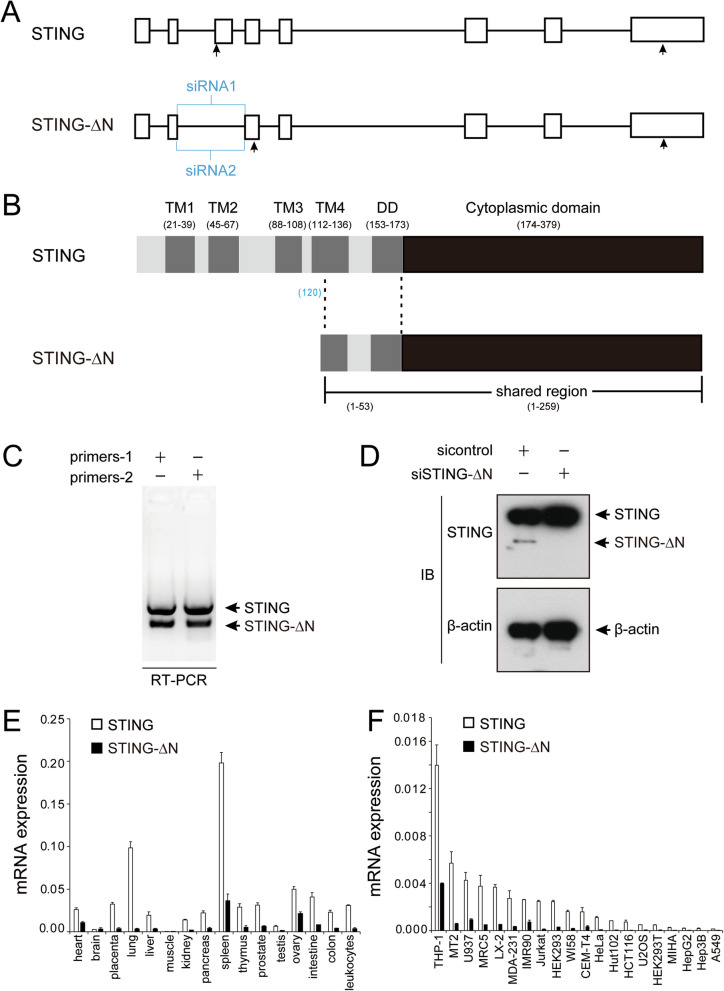

The human STING (TMEM173) gene consists of 8 exons and 7 introns (Fig. 1A) and encodes an alternative STING isoform, STING-∆N, generated by exon 3 skipping, introducing a new start codon in exon 4. This novel isoform was validated through PCR amplification and DNA sequencing from human-derived cell line THP-1. Compared with full-length STING transcript (hereafter referred to as STING), the new STING isoform lacks part of the N-terminus but shares an identical C-terminus with STING, thus it is designated as STING-∆N (Fig. 1A). The mRNA sequence spans 780 bp, encoding a 260 amino acid protein (Fig. 1B). Notably, STING-∆N’s initial 53 amino acids encompass part of transmembrane region 4 (TM4) and the dimerization domain (DD), while the remaining 207 amino acids are identical to the cytoplasmic domain (CTD) of STING, producing a shortened STING form (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Identification of STING-∆N as an alternative splicing isoform of STING. A Schematic representation of the genomic structure of STING and STING-∆N. Exons are depicted as boxes, introns as lines, with arrows marking the translation start and stop sites. Positions of siRNAs used for STING-∆N knockdown are indicated. B Domain map of STING and STING-∆N, highlighting the transmembrane (TM), dimerization domain (DD), and cytoplasmic domain. C RT-PCR amplification showing distinct bands for STING and STING-∆N isoforms in THP-1 cells. D Immunoblot analysis confirming STING-∆N knockdown in THP-1 cells using isoform-specific siRNAs. E Quantification of STING and STING-∆N across human tissues using cDNA libraries from the Human MTC™ Panel I (Clonetech, product number: 636742). F RT-qPCR analysis of STING and STING-∆N in various human cell lines

To specifically identify STING-∆N, RT-PCR was performed on cDNA from THP-1 cells using primers targeting exon 2 and exon 4 of STING (Fig. 1A). The amplification of two distinct DNA bands confirmed that the two pairs of primers can specifically detect both STING and STING-∆N simultaneously (Fig. 1C). Additionally, siRNAs sequences (siSTING-∆N-1 and siSTING-∆N-2) were designed to specifically knock down STING-∆N without affecting STING expression. Immunoblotting results showed that siSTING-∆N specifically downregulated the protein level of STING-∆N in THP-1 cells, confirming the existence and specificity of STING-∆N (Fig. 1D).

Expression patterns of STING-∆N in tissues and cell lines

RT-qPCR quantification of STING and STING-∆N mRNA across human tissues and cell lines used transcript-specific primers (Supplementary Table S1). STING-∆N mRNA levels were low across tissues such as the heart, ovary, placenta, lung, liver, intestine, pancreas, thymus, prostate, colon, and leukocytes, and negligible in the brain, muscle, kidney, and testis. STING mRNA was more abundant than STING-∆N in all tissues, with both displaying elevated levels in the spleen and ovary (Fig. 1E). STING-∆N expression was detected at low levels in most tissues, similar to the expression profile of STING-β [29]. However, STING-∆N exhibited a more selective expression pattern in spleen and THP-1 cells, suggesting its specific role in immune modulation (Fig. 1E & F). Consistent with the mRNA expression results, protein level of STING-∆N was highest in THP-1, while being nearly undetectable in other cell lines (Figure S1A). Moreover, STING exhibited significantly higher protein abundance compared to STING-∆N across the cell lines tested (Figure S1A).

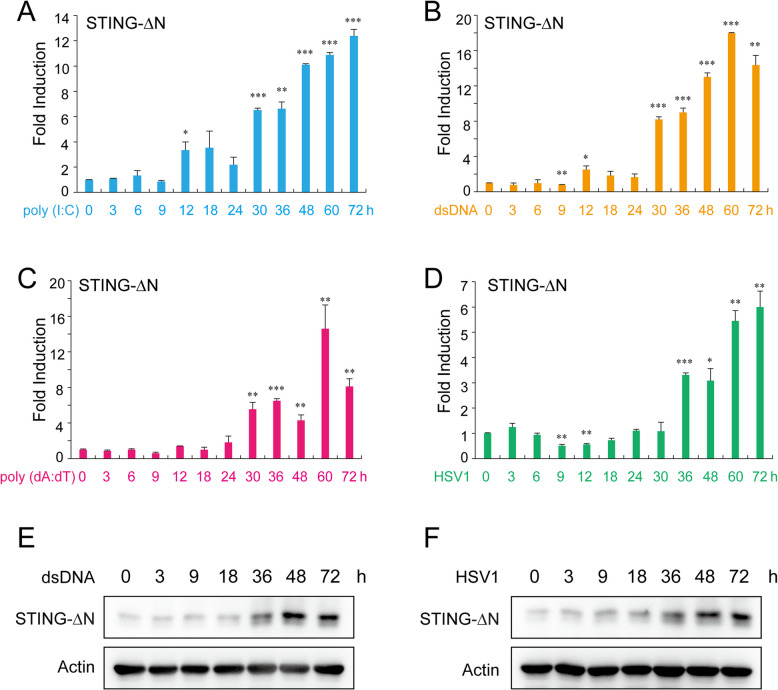

Expression levels of STING and STING-∆N were assessed in several human cell lines, with RT-qPCR detecting both isoforms in THP-1, MT2, U937, MRC5, LX-2, MDA-231, IMR90, HEK293, and CEM-T4. Notably, STING-∆N was most abundant in THP-1 cells, prompting further analysis of its induction. Next, we sought to determine whether STING-∆N expression is modulated by IFN signaling, which would support its potential role as a negative feedback regulator of the cGAS-STING pathway. RT-qPCR showed that STING-∆N levels remained stable in early phases (0–9 h) of various IFN stimuli, including poly (I:C), dsDNA, poly (dA:dT), and HSV-1, but significantly increased at 30 h (Fig. 2). To further confirm the results in RT-qPCR experiments, we next utilized an antibody to detect STING-∆N protein level in THP-1 cells. The immunoblot results showed that the protein level of STING-∆N gradually increased in a time dependent manner upon dsDNA stimulation or HSV-1 infection (Fig. 2E, F). This late-phase upregulation correlates inversely with IFN and ISG induction, suggesting that STING-∆N may act as a negative regulator in the innate immune signaling pathway (Fig. 2) [29].

Fig. 2.

STING-∆N expression in response to nucleic acid and DNA virus stimuli. RT-qPCR analysis of STING-∆N expression in THP-1 cells transfected with (A) dsRNA mimic poly (I:C) (1000 ng/mL), (B) dsDNA mimic HSV-1-60mer (1000 ng/mL), (C) dsDNA mimic poly (dA:dT) (1000 ng/mL), or (D) infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 1). Immunoblot analysis of STING-∆N protein level in THP-1 cells transfected with (E) dsDNA mimic HSV-1-60mer (1000 ng/mL) or (F) infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 1). Cells were harvested at specified time points post-stimulation. Data are shown as means ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance between the indicated groups and the control (0 h) was determined using Student’s t-test (∗ p < 0.05, ∗∗ p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗ p < 0.001)

STING-∆N inhibits STING, cGAS, and 2′3′-cGAMP-induced IFN activation

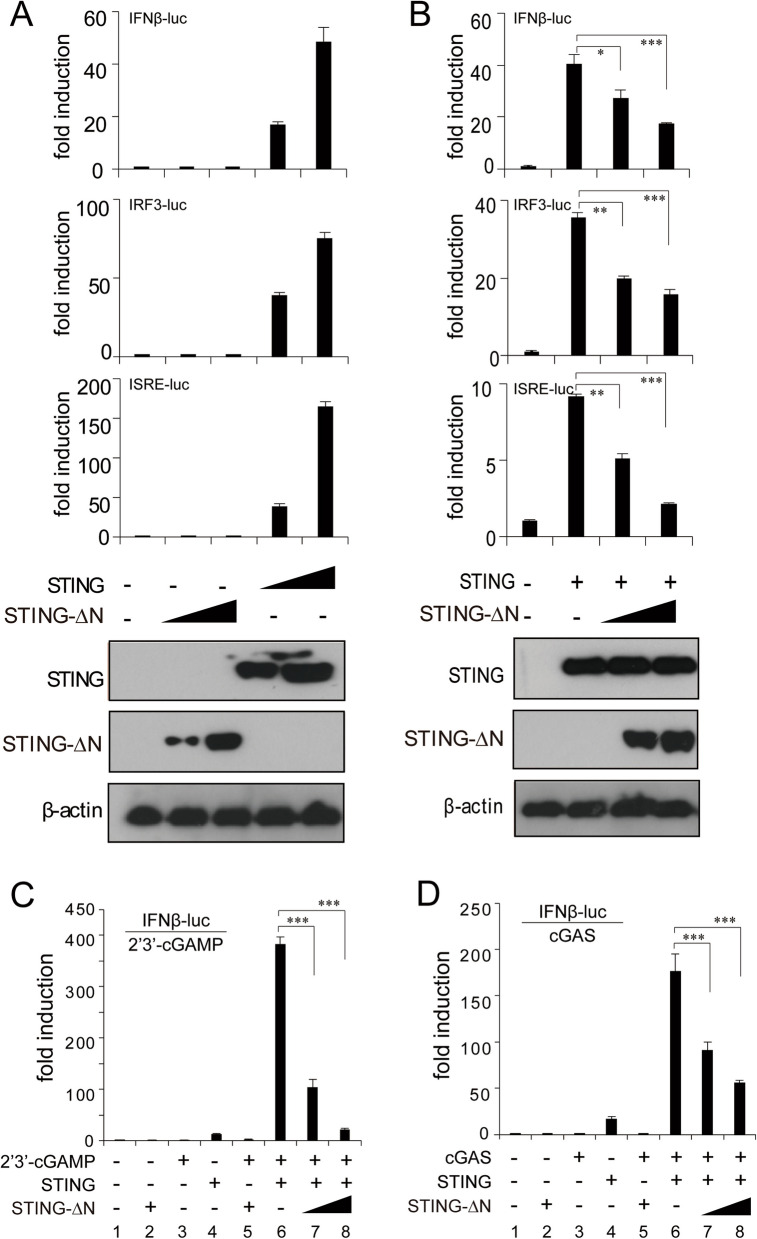

STING-∆N retains the CTD of STING, responsible for 2′3′-cGAMP binding, subcellular localization, oligomerization, and downstream signaling via the STING-TBK1 signalosome [14]. We assessed the role of STING-∆N in type I IFN response by testing IFN-β, ISRE, and IRF3 promoter activation in HEK293T cells. Co-transfection with STING significantly increased luciferase activity in all three reporters, reflecting active type I IFN signaling (Fig. 3A). Conversely, STING-∆N alone did not activate these reporters, indicating a lack of intrinsic IFN-inducing function (Fig. 3A). Co-expression of STING-∆N with STING in varying doses revealed dose-dependent suppression of IFN-β, ISRE, and IRF3 luciferase activity, confirming STING-∆N’s role as a negative regulator of STING-mediated IFN activation (Fig. 3B). The second messenger 2′3′-cGAMP, generated by cGAS, binds to STING’s CTD, triggering STING translocation from ER to Golgi and subsequent type I IFN response [15]. Luciferase assays in HEK293T cells revealed that co-expression of cGAS and STING strongly activated IFN-β (Fig. 3D, lane 6), with similar activation from exogenous 2′3′-cGAMP (Fig. 3C, lane 6). However, STING-∆N co-expression substantially reduced cGAS-mediated IFN-β activation in a dose-dependent manner, diminishing IFN-β response as STING-∆N levels increased (Fig. 3D, lanes 7–8). Further, STING-∆N co-expression blocked 2′3′-cGAMP-induced IFN-β promoter activation in cells with active STING, confirming that STING-∆N inhibits type I IFN signaling, despite sharing the 2′3′-cGAMP binding domain (Fig. 3C, lanes 7–8). Since STING-β and STING-∆N play similar roles in inhibiting STING activation, we next sought to compare the inhibitory capacities of STING-β and STING-∆N. The RT-qPCR results showed that STING-β overexpression leads to decreased induction of IFN-β and CXCL10 in comparison with STING-∆N at equivalent protein expression levels, suggesting a stronger inhibitory effect of STING-β on STING pathway (Figure S1B).

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of STING, 2′3′-cGAMP, and cGAS-induced IFN activation by STING-∆N. A STING activates the IFN-β-luc, IRF3-luc, and ISRE-luc reporters while STING-∆N lacks this activity. HEK293T cells were transfected with STING or increasing amounts of STING-∆N plasmid in combination with IFN-β-luc, IRF3-luc, or ISRE-luc reporter plasmids. B Dose-dependent suppression of STING-mediated IFN responses by STING-∆N, measured via luciferase assay. HEK293T cells were co-transfected with STING and increasing doses of STING-∆N plasmids. C Luciferase reporter assay showing dose-dependent inhibition of 2′3′-cGAMP-induced IFN-β-luc activation by STING-∆N. HEK293T cells were co-transfected with STING plasmid and increasing doses of STING-∆N plasmid, along with pRL-TK and IFN-β-luc reporter plasmids as indicated. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were stimulated by 2′3′-cGAMP. D Dose-dependent suppression of cGAS-induced IFN-β-luc activation by STING-∆N. STING, cGAS, and STING-∆N plasmids were co-transfected into HEK293T cells with pRL-TK and IFN-β-luc reporter plasmids as indicated. An empty vector was used to balance the total amount of transfected DNA. Data are shown as means ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance between the indicated groups and the control group was determined using Student’s t-test (∗ p < 0.05, ∗∗ p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗ p < 0.001)

STING-∆N attenuates the type I and III IFN responses

We investigated STING-∆N’s role in antiviral immunity, specifically its effect on type I and III IFN production in HeLa cells with a functional cGAS-STING pathway [35]. STING-∆N-expressing HeLa cells stimulated with calf thymus genomic DNA (CT-DNA) exhibited reduced IFN-β, IFN-λ1, ISG54, and CXCL10 expression compared to control cells (Fig. 4A). STING-∆N also suppressed IFN responses triggered by DNA viruses HPV16 and HSV-1 (Fig. 4B, C), and increased HSV-1 viral RNA levels, suggesting STING-∆N enhances viral replication. To validate STING-∆N’s regulatory function, we performed loss-of-function assays in THP-1 cells, which express STING-∆N robustly (Fig. 1F). Knockdown of STING-∆N with specific siRNAs resulted in increased IFN-β and ISG56 induction upon dsDNA stimulation (Fig. 4D), confirming that STING-∆N inhibits dsDNA- and DNA virus-induced IFN responses. To investigate the suppressive effect of STING-∆N in STING-mediated immune responses, we employed THP-1 knockdown cell model and infected them with HSV-1. The results showed that THP-1 cells knockdown of STING-ΔN induced higher levels of IFN-β, ISG56, and CXCL10 upon HSV-1 infection in contrast to control cells (Fig. 4E). STING-ΔN knockdown also impaired HSV-1 replication in THP-1 cells (Fig. 4E). To further confirmed the specific knockdown effect of STING-ΔN in THP-1 cells, we next examined the expression levels of STING-β and STING-∆N in the shRNA knockdown experiments. The immunoblot and RT-qPCR results demonstrated that STING-∆N targeting shRNA selectively impaired STING-∆N protein and mRNA levels without affecting STING-β expression (Figure S2). Also, these results indicated that STING-ΔN displayed relatively higher abundance than STING-β in THP-1 cells (Figure S2C and S2D). Collectively, these results suggest that STING-∆N negatively regulates the STING-mediated innate immune signaling.

Fig. 4.

STING-∆N modulates IFN responses to dsDNA stimulation and DNA virus infection. A STING-∆N suppresses IFN responses induced by dsDNA. THP-1 cells expressing STING-∆N or an empty vector (control group) were stimulated with CT-DNA. Nine hours post-stimulation, mRNA levels of IFN‐β, IFN-λ1, ISG54, and CXCL10 were measured using RT-qPCR. B STING-∆N inhibits IFN responses triggered by HPV16 infection. HeLa cells expressing STING-∆N or an empty vector (control group) were infected with HPV16 virions (MOI = 5). Nine hours post-stimulation, mRNA levels of IFN‐β, ISG15, ISG54, and ISG56 were determined by RT-qPCR. C STING-∆N inhibits HSV-1-induced IFN response. THP-1 cells expressing STING-∆N or an empty vector (control group) were infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 5). Nine hours post-stimulation, mRNA levels of IFN‐β, IFN-λ1, ISG54, CXCL10, and HSV-1 TK viral RNA were detected using RT-qPCR. D Knockdown of STING-∆N via siRNA augments dsDNA-induced IFN response. THP-1 cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs using lipofectamine 2000. Forty-eight hours post-transfection, cells were harvested to determine gene knockdown efficiency or further stimulated with dsDNA mimic HSV-1-60mer (1000 ng/mL). Six hours later, the expression of target genes was assessed by RT‐qPCR. E Knockdown of STING-∆N via shRNA enhances HSV-1-induced IFN responses. shSTING-∆N THP-1 cells and shControl THP-1 cells were infected with HSV‐1 (MOI = 1 or MOI = 2) for 9 h. Nine hours post-stimulation, mRNA levels of IFN‐β, ISG56, CXCL10, and HSV-1 TK viral RNA were detected using RT-qPCR. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance between the indicated groups and the control group was determined using Student’s t-test (∗ p < 0.05, ∗∗ p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗ p < 0.001)

STING-∆N antagonizes STING-mediated antiviral immunity, enhancing HSV-1 replication

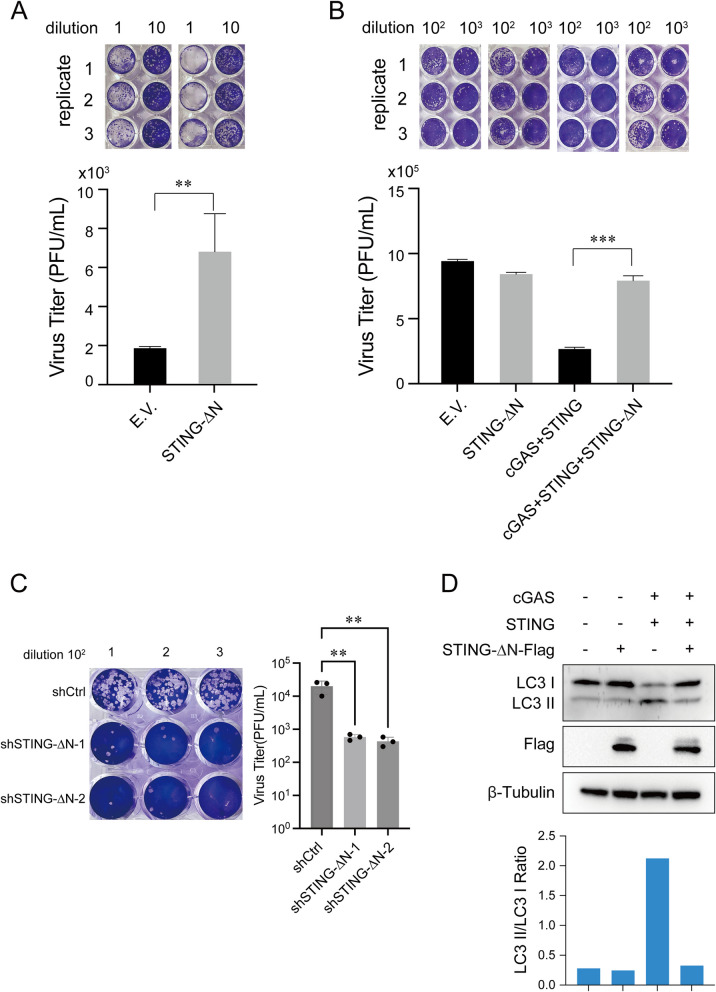

While STING-∆N reduces STING activation and IFN responses, its full impact on antiviral immunity and virus replication remains unclear. The cGAS-STING pathway is critical in DNA virus defense, prompting us to investigate STING-∆N’s role in HSV-1 replication, a model DNA virus. THP-1 cells stably expressing STING-∆N and control cells were infected with HSV-1, and virus titers were measured in culture supernatants. Plaque assays showed that STING-∆N expression led to a threefold increase in HSV-1 replication compared to controls (Fig. 5A). Similar results in HEK293T cells showed STING-∆N overexpression impaired immune responses activated by cGAS-STING co-expression (Fig. 5B). To investigate the effect of STING-∆N in STING-mediated antiviral immune responses, we employed THP-1 knockdown cell model and infected them with HSV-1. The plaque assays showed that STING-∆N knockdown also led to the deceased HSV-1 virus titers in supernatants (Fig. 5C). Together, above results suggest that STING-∆N negatively regulates STING-mediated antiviral immunity.

Fig. 5.

STING-∆N facilitates HSV-1 propagation and suppresses autophagy. A Plaque assay showing increased HSV-1 propagation in THP-1 cells overexpressing STING-∆N, compared to control (empty vector). THP-1 cells expressing STING-∆N or an empty vector (control group) were infected with HSV‐1 (MOI = 5) for 24 h. The cell culture supernatant was collected for plaque assays to assess viral propagation. B Suppression of HSV-1 propagation by STING-∆N. HEK293T cells were transfected with an empty vector or STING-∆N plasmid, along with cGAS and STING plasmids as indicated, for 24 h, followed by HSV‐1 infection (MOI = 0.5) for an additional 24 h. C Plaque assay showing decreased HSV-1 replication in THP-1 cells with the knockdown of STING-∆N, compared to control cells. shSTING-∆N THP-1 cells and shControl THP-1 cells were infected with HSV‐1 (MOI = 5) for 24 h. The cell culture supernatant was collected for plaque assays to assess viral propagation. D Immunoblot showing reduction in autophagy marker LC3-II in HEK293T cells expressing STING-∆N. HEK293T cells were transfected with an empty vector or STING-∆N plasmid alongside cGAS and STING plasmids. After 24 h, the cells were harvested for immunoblotting (top). Quantitation of LC3-II/LC3-I ratios was performed using ImageJ. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test (∗ p < 0.05, ∗∗ p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗ p < 0.001)

Inhibition of STING-mediated autophagy by STING-∆N

STING has recently been shown to activate autophagy as a conserved cell-autonomous defense against DNA viruses [36]. To assess STING-∆N’s effect on this process, we evaluated LC3-I to LC3-II conversion in HEK293T cells co-expressing cGAS and STING. STING-∆N significantly inhibited this autophagy-associated conversion (Fig. 5D). Given autophagy’s role in viral clearance and cellular homeostasis, STING-∆N’s suppression could have implications for neurodegenerative diseases characterized by autophagy dysregulation [22, 37, 38]. Thus, STING-∆N emerges as a potential therapeutic target for autophagy-related diseases such as Alzheimer or Parkinson, highlighting its role in impairing STING-mediated autophagy and antiviral immunity.

STING-∆N inhibits STING-induced IRF3 activation

Through its interaction with STING’s CTD, STING-∆N likely inhibits downstream cGAS-STING signaling events. THP-1 cells expressing STING-∆N showed reduced phosphorylation of STING, TBK1, and IRF3 following CT-DNA stimulation compared to controls (Fig. 6A). Similar outcomes were observed in HEK293T cells, where STING-∆N overexpression significantly suppressed phosphorylation of these proteins when co-transfected with cGAS and STING (Fig. 6B and C). Furthermore, to confirm the role of STING-∆N in STING signaling, we used short hairpin RNA technique to knockdown STING-∆N in THP-1 cells and measured the effect of STING-∆N on cGAS-STING mediated IFN-β signaling. Immunoblot results displayed that shRNA knockdown of STING-∆N expression enhanced the phosphorylation of STING, TBK1, and IRF3 upon HSV-1 infection (Fig. 6D). Since phosphorylated IRF3 translocates to the nucleus to initiate type I IFN responses, immunofluorescence revealed lower IRF3 nuclear translocation in STING-∆N-expressing HeLa cells post CT-DNA stimulation (Fig. 6E). This was further confirmed by fractionating cells into cytoplasmic and nuclear components for immunoblot analysis, where CT-DNA-stimulated IRF3 translocation was notably reduced in STING-∆N-expressing cells (Fig. 6F). These data show that STING-∆N impedes phosphorylation of STING, TBK1, and IRF3, as well as IRF3’s nuclear translocation.

Fig. 6.

STING-∆N inhibits IRF3 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation. A Immunoblot showing IRF3 phosphorylation suppression in THP-1 cells expressing STING-∆N post-CT-DNA stimulation (9 h). B, C Phosphorylation levels of TBK1, IRF3, and STING in HEK293T cells co-transfected with STING-∆N and STING (B) or STING-∆N, STING, and cGAS (C) were analyzed by immunoblot. Empty vector balanced total DNA. D Phosphorylation levels of TBK1, IRF3, and STING in shSTING-∆N THP-1 cells and shControl THP-1 cells infected with HSV‐1 (MOI = 5) for 6 and 9 h. E Confocal immunofluorescence images displaying IRF3 nuclear localization in HeLa cells with or without STING-∆N post-CT-DNA stimulation. Scale bar: 10 µm. IRF3 localization was quantified in 50 cells per group (right). F Immunoblot of cytoplasmic and nuclear IRF3 fractions in HeLa cells stably transduced with STING-∆N or empty vector, stimulated with CT-DNA for 9 h. Lamin B1 and β-tubulin served as nuclear and cytoplasmic markers. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test (∗ p < 0.05, ∗∗ p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗ p < 0.001)

STING-∆N inhibits STING oligomerization and STING-TBK1 signalosome formation

Structural studies indicate that STING forms oligomers via CTD interactions [39]. We investigated if STING-∆N associates with STING and interferes with downstream activities. Co-immunoprecipitation in HEK293T cells revealed that STING-∆N interacts with STING (Fig. 7A and B). STING dimers typically form oligomers and the STING-TBK1 signalosome [39, 40]. Co-expression of STING-∆N and TBK1 in HEK293T cells, followed by reciprocal co-immunoprecipitation, confirmed STING-∆N’s interaction with TBK1 (Fig. 7C and D). Overexpression of STING-∆N significantly reduced TBK1 levels in STING-HA precipitates, indicating that STING-∆N hinders STING-TBK1 complex formation (Fig. 7E). Furthermore, an SDD-AGE assay showed STING-∆N reduced oligomerization of STING induced by either STING alone or STING-TBK1 co-transfection (Fig. 7F). Immunofluorescence assays showed that STING-∆N co-localized with the ER tracker and partially with the mitochondria tracker, but not with the Golgi tracker (Fig. 7G). In line with the co-immunoprecipitation results, STING-∆N co-localized with STING and TBK1 (Fig. 7H). To further investigate whether STING-∆N traffics to Golgi like STING, we constructed a HeLa cell line stably expressing STING-∆N and infected them with HSV-1. Our results showed that STING-ΔN remained confined to the ER, with no observable trafficking to Golgi upon HSV-1 infection (Fig. 7I). Moreover, immunofluorescence results also indicated that STING-∆N inhibited STING translocation to Golgi apparatus and STING puncta formation upon HSV-1 infection (Figure S1C). Thus, STING-∆N interacts with STING and TBK1, thereby preventing STING oligomerization, ER to Golgi translocation, and STING-TBK1 signalosome formation.

Fig. 7.

STING-∆N interacts with STING and prevents STING-TBK1 complex formation. A, B Interaction between STING-∆N and STING. HEK293T cells were transfected with STING-∆N-HA and STING-Flag plasmids as indicated for 24 h. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-HA antibody (A) or anti-Flag antibody (B) and then immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. C, D Interaction between STING-∆N and TBK1. HEK293T cells were transfected with STING-∆N-HA and TBK1-Flag plasmids as shown for 24 h. Cell lysates were subjected to co-immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibody (C) or anti-Flag antibody (D), and followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. E STING-∆N inhibits STING–TBK1 interaction. HEK293T cells were transfected with TBK1-Myc, STING-HA, and STING-∆N-Flag plasmids as indicated for 24 h. Cell lysates were subjected to co-immunoprecipitation using anti-HA antibody, followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. F STING-∆N suppresses STING aggregation. HEK293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing STING, TBK1, or STING-∆N as shown. Twenty‐four hours later, cells were lysed for SDD‐AGE (top) and SDS‐PAGE (bottom) analysis. G Representative confocal images showing the subcellular localization of STING-∆N. HeLa cells were transfected with STING-∆N-Flag plasmid together with Mito-DsRed2, ER-DsRed2 or Golgi-EYFP plasmids. Immunofluorescence staining was performed with anti-Flag antibody and analyzed by confocal microscopy. Scale bar: 10 µm. H Immunofluorescence of STING-∆N co-localization with STING and TBK1 in HeLa cells. HeLa cells were transfected with STING-∆N-Flag plasmid together with STING-HA or TBK1-Myc plasmids. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the slides were fixed and processed for immunofluorescence staining. Scale bar, 10 µm. I Immunofluorescence of STING-∆N co-localization with Calnexin and GM130 in HeLa cells. HeLa cells were infected with HSV-1 DNA virus. Four hours after transfection, the slides were fixed and processed for immunofluorescence staining. Scale bar, 10 µm

STING-∆N binds 2′3′-cGAMP and blocks its interaction with STING

Experiments show that 2′3′-cGAMP does not activate STING-∆N, yet STING-∆N suppresses STING activation by 2′3′-cGAMP (Fig. 3A and C). We hypothesized that STING-∆N binds 2′3′-cGAMP separately from STING, inhibiting 2′3′-cGAMP’s interaction with STING. To test this, a 2′3′-cGAMP pull-down assay was conducted using THP-1 cell lysates post-DNA stimulation. Silver staining and immunoblotting revealed multiple bands in 2′3′-cGAMP-agarose precipitates, including those matching STING and STING-∆N (Fig. 8A). Immunoblotting with a STING-specific antibody confirmed that both STING and STING-∆N were present in 2′3′-cGAMP pull-down samples (Fig. 8A, B), indicating 2′3′-cGAMP interacts with both upon DNA stimulation. To further examine whether STING-∆N directly interacts with 2′3′-cGAMP, we performed a 2′3′-cGAMP pull-down assay using lysates from HEK293T cells overexpressing either STING or STING-∆N. The assay results indicated that both STING and STING-∆N were present in 2′3′-cGAMP-agarose precipitates, with no detection in the control group (Fig. 8B). Additionally, STING-∆N was shown to inhibit the 2′3′-cGAMP-STING interaction in a dose-dependent manner. These findings support the role of STING-∆N as a negative regulator within the cGAS-STING pathway, blocking the essential 2′3′-cGAMP-STING association required for downstream immune signaling.

Fig. 8.

STING-∆N binds with 2′3′-cGAMP and impedes STING-2′3′-cGAMP interaction. A 2′3′-cGAMP pull-down assay showing endogenous STING and STING-∆N binding to 2′3′-cGAMP in THP-1 cells stimulated with dsDNA for 6 h, analyzed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining or immunoblotting with anti-STING. B Pull-down of overexpressed STING-HA and STING-∆N-HA in HEK293T cells using 2′3′-cGAMP agarose. STING-HA and STING-∆N-HA plasmids were transfected into HEK293T cells. After 48 h, cells were harvested and lysed, and 2′3′-cGAMP pull-down assays were conducted using control agarose or 2′3′-cGAMP agarose. Input proteins and 2′3′-cGAMP pull-down products were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-HA or anti-Flag antibody. C Dose-dependent inhibition of STING-2′3′-cGAMP interaction by STING-∆N. STING-HA and increasing doses of STING-∆N-HA plasmids were co-transfected into HEK293T cells. After 48 h, cells were lysed and subjected to 2′3′-cGAMP pull-down assays

Discussion

The innate immune nucleic acid sensing pathways, including TLRs, RLRs, and cGAS-STING, are finely regulated by splicing isoforms of critical signaling molecules, such as TBK1 [41], IRF3 [42], TRIF [43], MAVS [44], and RIG-I [28]. These variants are crucial for modulating immune activation, ensuring controlled deactivation of signaling cascades. Here, we identified a novel spliced isoform of STING, STING-∆N, which lacks exon 3, resulting in a truncated N-terminus. STING-∆N was detected across multiple tissues and cell lines, particularly in immune-associated ones. Under basal conditions, neither transient nor stable expression of STING-∆N initiated type I IFN responses. However, following stimulation with 2′3′-cGAMP, dsDNA, or DNA viruses, STING-∆N functioned as a dominant negative regulator of the cGAS-STING-IFN pathway. Overexpression of STING-∆N not only enhanced viral replication but also suppressed STING-mediated autophagy. Mechanistically, STING-∆N binds 2′3′-cGAMP, STING, and TBK1, inhibiting 2′3′-cGAMP-STING interaction and STING-TBK1 complex formation, thereby acting as a decoy that attenuates downstream signaling.

Under normal conditions, STING expression remains low across tissues and cell types, with minimal basal levels preventing unnecessary immune activation. Upon pathogen infection or ligand stimulation, STING expression is upregulated in a STAT1-dependent manner, amplifying IFN responses via positive feedback [9, 29, 45]. This study compared STING and STING-∆N expression patterns across human tissues and cell lines, revealing that both were highly expressed in immune-related organs and hematopoietic lines, such as the spleen and THP-1. While STING was abundant in the lung, thymus, intestine, and colon, STING-∆N was scarcely detected in these tissues and exhibited low expression in most cell lines. These results indicate that STING-∆N may function as a cell-type-specific inhibitor of STING-mediated immune responses. Moreover, our results show that the expression ratios between STING and STING-∆N are not entirely consistent at the mRNA and protein levels. The observed discrepancy between mRNA and protein expression levels of STING and STING-∆N (lacking exon 3) may be attributed to post-transcriptional and post-translational regulatory mechanisms. The absence of exon 3 in STING-∆N could affect mRNA stability, translation efficiency, or protein stability, leading to reduced protein levels despite comparable mRNA expression. STING-∆N’s expression pattern closely resembles that of STING-β, another isoform highly expressed in immune-related tissues. Given that STING is an interferon-stimulated gene (ISG) central to the positive feedback loop of type I IFN responses, we explored if STING-∆N expression responds to immune activation. STING-∆N expression significantly increased during the late stages of HSV-1 infection and nucleic acid stimulation (9–30 h), remaining stable in early phases (1–9 h). This dynamic expression pattern parallels other STING isoforms like MITA-related protein (MRP) and STING-β, both known to exhibit stimulus-dependent regulation across infection stages [29, 32]. STING-β, transcribed from an alternative promoter, showed inverse correlation with IFN-β and ISG levels, suggesting a role in negative feedback within the cGAS-STING pathway [29]. Similarly, MRP increased in response to HSV-1 and HBV but decreased in RNA virus infections [32]. Collectively, these findings imply that STING isoforms, including STING-∆N, undergo stimulus-dependent modulation during distinct stages of viral infection.

While STING’s role in autophagy is well-documented, studies predominantly address its full-length form, overlooking the potential impact of splicing isoforms [37]. Upon binding 2′3′-cGAMP, STING translocates from the ER to the ER-Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC), forming scaffolds to recruit autophagy-related proteins such as ULK1 (unc-51-like kinase 1), ATG5 (autophagy related 5)-ATG12 (autophagy related 12), and LC3 [36]. Our findings reveal that STING-∆N not only negatively regulates IFN signaling but also suppresses STING-mediated autophagy, underscoring a novel role for alternative splicing in autophagy regulation—critical for maintaining cellular homeostasis. STING translocation and STING-TBK1 phosphorylation are pivotal for autophagy initiation [36]. By retaining STING at the ER and inhibiting STING-TBK1 phosphorylation, STING-∆N likely downregulates autophagy. This study provides the first direct link between a STING isoform, specifically STING-∆N, and autophagy regulation. Future research should focus on elucidating STING-∆N’s molecular interactions with autophagy-related proteins and exploring its regulatory role in conditions such as chronic infections and neurodegeneration. In vivo studies on STING-∆N’s physiological relevance could further unveil its therapeutic potential.

Various STING isoforms have been identified and characterized, with distinct mechanisms governing their transcript generation splicing mechanisms—including exon skipping, intron retention, and utilization of different transcription start sites—play pivotal roles in the production of these isoforms [5, 7]. STING-∆N produced by exon 3 skipping, results in a truncated N-terminus that acts as a dominant-negative regulator, mitigating excessive STING activation and IFN production. Similarly, the MRP isoform, produced by exon 7 skipping, truncates the C-terminus to inhibit STING function [32]. Rodríguez-García et al. reported three E7-less STING isoforms lacking exon 7; one of these is identical to MRP, while others are produced by skipping additional exons or through intron retention [31]. Additionally, STING-β is transcribed from an alternative promoter located within intron 6, yielding an isoform with a distinct N-terminus yet retaining STING’s CTD functionality [29]. These findings underscore the role of alternative splicing as a crucial regulatory mechanism in the cGAS-STING pathway.

STING is encoded by eight exons and contains three distinct functional domains: four TM domains for ER localization, a CDN-binding domain for ligand binding, and a C-terminal tail essential for TBK1 and IRF3 activation [14, 39, 40]. Although STING-∆N lacks TM1 to TM3, immunofluorescence results showed that it still co-localized with ER marker, suggesting that the remaining TM domains are sufficient for ER localization, or other factors, such as proteins [46] or cholesterol [47], may assist in its ER localization. Notably, a novel STING isoform, plasmatic membrane STING (pmSTING), produced by exon skipping, lacks TM1 and localizes to the plasma membrane. These findings suggest that truncations in TM domains can influence STING localization to different cellular organelles [30]. Further studies are required to confirm endogenous localization and elucidate functional truncated STING isoforms. Moreover, the transmembrane serine protease hepsin specifically cleaves STING at TM4, resulting in a product structurally similar with STING-∆N [48]. While hepsin-mediated cleavage of STING at TM4 and the dominant-negative function of STING-∆N both suppress STING activation, they operate through distinct mechanisms and in different cellular contexts. Hepsin, primarily expressed in liver and prostate cancer cells, reduces STING protein levels via proteolytic cleavage, thereby inhibiting IFN-β induction during viral infections. In contrast, STING-∆N, which lacks TM1-3 domains and is highly expressed in myeloid cells, acts as a defective form of STING by forming non-functional heterodimers that disrupt proper oligomerization and downstream signaling. Further studies are needed to determine whether the hepsin-cleaved STING product shares functional similarities with STING-∆N, particularly in terms of stability and dominant-negative activity.

Structural analyses reveal that amino acids 153–180 facilitate STING’s homotypic interactions, while the C-terminal tail (CTT) mediates TBK1 and IRF3 recruitment [15, 39, 40, 49]. STING-∆N, comprising 53 N-terminal residues with partial TM4 and dimerization domains, shares a 207-residual domain, including the complete CDN-binding domain (CBD) and CTT. This structural similarity allows STING-∆N to interact with STING, TBK1, and 2′3′-cGAMP, thereby impeding STING-2′3′-cGAMP binding and STING-TBK1 complex formation, ultimately disrupting downstream IFN signaling (Fig. 9). STING-∆N, despite retaining the ability to bind 2′3′-cGAMP and TBK1, likely acts in a dominant-negative manner by sequestering these signaling components without fully activating downstream signaling. Specifically, the variant may form non-functional heterodimers with the full-length STING protein, thereby preventing the proper oligomerization, ER to Golgi trafficking, or post-translational modifications (e.g., ubiquitination, phosphorylation) required for robust activation of IRF3 and NF-κB pathways. Further structural studies via cryo-EM or X-ray crystallography are needed to elucidate binding interfaces of STING-∆N, which could inform the design of small molecules that replicate its inhibitory effects. Such compounds may have therapeutic applications for autoimmune diseases characterized by STING hyperactivation [29]. Additionally, STING-∆N’s interruption of STING-TBK1 interactions and oligomerization supports a model where STING activation is attenuated by dissociation from 2′3′-cGAMP and other signaling proteins, including TRAPβ, Sec61β, Sec5, iRhom2, STEEP, and the COPII complex [9, 12]. Given STING-∆N’s ER localization, its potential impact on STING’s ER-to-Golgi translocation warrants further exploration.

Fig. 9.

Proposed mechanism of STING-∆N-mediated inhibition of cGAS-STING pathway. During the early stage of DNA virus or dsDNA stimulation, low STING-∆N levels allow full STING activation and IFN production upon dsDNA or DNA virus stimulation. In the later stage, STING-∆N expression increases, leading to the enhanced sequestration of 2′3′-cGAMP, STING, and TBK1, thus forming non-functional heterodimers with the full-length STING and attenuating prolonged IFN signaling

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that STING-∆N functions as a potent negative regulator within the cGAS-STING pathway during responses to intracellular dsDNA and DNA virus infections. By inhibiting 2′3′-cGAMP-induced STING activation, STING-∆N effectively suppresses IFN-β production and impairs STING-mediated autophagy and antiviral immunity. The observed upregulation of STING-∆N in the later infection stages suggests a potential modulatory role in preventing immune overactivation. These findings offer critical insights into the regulatory complexity of the cGAS-STING pathway and position STING-∆N as a promising therapeutic target for treating STING-related autoimmune diseases, chronic infections, and cancer.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank the Translational Medicine Core Facility of Shandong University for the consultation and instrument availability that supported this work.

Abbreviations

- dsDNA

Double stranded DNA

- CT-DNA

Calf thymus genomic DNA

- IFN

Interferon

- ISG

Interferon-stimulated gene

- cGAMP

Cyclic GMP-AMP

- HSV-1

Herpes simplex virus type 1

- HPV16

Human papillomavirus type 16

- VSV

Vesicular stomatitis virus

- TM

Transmembrane

- CTD

C-terminal cytoplasmic domain

- DD

Dimerization domain

- CTT

C-terminal tail

- SDD-AGE

Semi-denaturing detergent agarose gel electrophoresis

Authors’ contributions

P.H. W. designed and supervised the overall experimental design and execution. J. D. performed the experiments and analyzed the data with assistance from S.N. Z., J. Z., C.H. L., and T., L.. J. D. and P.H. W. wrote the manuscript and revised the draft. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2020QC085 to P.‐H.W), grants from the Taishan Scholar Project of Shandong Province (tsqn202211006 to P.‐H.W), and grants from the Natural Science Foundation of China (82471796 to P.‐H.W). This work was also supported by grants from the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (GZC20231449).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ishii KJ, Akira S. Innate immune recognition of, and regulation by. DNA Trends Immunol. 2006;27:525–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan X, Sun L, Chen J, Chen ZJ. Detection of Microbial Infections Through Innate Immune Sensing of Nucleic Acids. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2018;72:447–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dempsey A, Bowie AG. Innate immune recognition of DNA: A recent history. Virology. 2015;479–480:146–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bachmann MF, Speiser DE. Linking Viral DNA to Endosomal Innate Immune Recognition. J Immunol. 2023;210:3–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan YK, Gack MU. RIG-I-like receptor regulation in virus infection and immunity. Curr Opin Virol. 2015;12:7–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Motwani M, Pesiridis S, Fitzgerald KA. DNA sensing by the cGAS-STING pathway in health and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20:657–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao D, Wu J, Wu YT, Du F, Aroh C, Yan N, Sun L, Chen ZJ. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is an innate immune sensor of HIV and other retroviruses. Science. 2013;341:903–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun L, Wu J, Du F, Chen X, Chen ZJ. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science. 2013;339:786–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishikawa H, Barber GN. STING is an endoplasmic reticulum adaptor that facilitates innate immune signalling. Nature. 2008;455:674–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhong B, Yang Y, Li S, Wang YY, Li Y, Diao F, Lei C, He X, Zhang L, Tien P, Shu HB. The adaptor protein MITA links virus-sensing receptors to IRF3 transcription factor activation. Immunity. 2008;29:538–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun W, Li Y, Chen L, Chen H, You F, Zhou X, Zhou Y, Zhai Z, Chen D, Jiang Z. ERIS, an endoplasmic reticulum IFN stimulator, activates innate immune signaling through dimerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8653–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeltema D, Abbott K, Yan N. STING trafficking as a new dimension of immune signaling. J Exp Med. 2023;220(3):e20220990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li T, Chen ZJ. The cGAS-cGAMP-STING pathway connects DNA damage to inflammation, senescence, and cancer. J Exp Med. 2018;215:1287–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang X, Bai XC, Chen ZJ. Structures and Mechanisms in the cGAS-STING Innate Immunity Pathway. Immunity. 2020;53:43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shang G, Zhang C, Chen ZJ, Bai XC, Zhang X. Cryo-EM structures of STING reveal its mechanism of activation by cyclic GMP-AMP. Nature. 2019;567:389–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu D, Shang G, Li J, Lu Y, Bai XC, Zhang X. Activation of STING by targeting a pocket in the transmembrane domain. Nature. 2022;604:557–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishikawa H, Barber GN. The STING pathway and regulation of innate immune signaling in response to DNA pathogens. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:1157–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crow YJ, Hayward BE, Parmar R, Robins P, Leitch A, Ali M, Black DN, van Bokhoven H, Brunner HG, Hamel BC, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the 3’-5’ DNA exonuclease TREX1 cause Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome at the AGS1 locus. Nat Genet. 2006;38:917–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Jesus AA, Marrero B, Yang D, Ramsey SE, Sanchez GAM, Tenbrock K, Wittkowski H, Jones OY, Kuehn HS, et al. Activated STING in a vascular and pulmonary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:507–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang K, Tang Z, Xing C, Yan N. STING signaling in the brain: Molecular threats, signaling activities, and therapeutic challenges. Neuron. 2024;112:539–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chu TT, Tu X, Yang K, Wu J, Repa JJ, Yan N. Tonic prime-boost of STING signalling mediates Niemann-Pick disease type C. Nature. 2021;596:570–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woo MS, Mayer C, Binkle-Ladisch L, Sonner JK, Rosenkranz SC, Shaposhnykov A, Rothammer N, Tsvilovskyy V, Lorenz SM, Raich L, et al. STING orchestrates the neuronal inflammatory stress response in multiple sclerosis. Cell. 2024;187(4043–4060): e4030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ng KW, Marshall EA, Bell JC, Lam WL. cGAS-STING and Cancer: Dichotomous Roles in Tumor Immunity and Development. Trends Immunol. 2018;39:44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Q, Wu P, Du Q, Hanif U, Hu H, Li K. cGAS-STING, an important signaling pathway in diseases and their therapy. MedComm. 2020;2024(5): e511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samson N, Ablasser A. The cGAS-STING pathway and cancer. Nat Cancer. 2022;3:1452–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Decout A, Katz JD, Venkatraman S, Ablasser A. The cGAS-STING pathway as a therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21:548–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang J, Wu J, Liu Q, Wu X, Zhao Y, Ren J. Post-Translational Modifications of STING: A Potential Therapeutic Target. Front Immunol. 2022;13: 888147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carpenter S, Ricci EP, Mercier BC, Moore MJ, Fitzgerald KA. Post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression in innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:361–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang PH, Fung SY, Gao WW, Deng JJ, Cheng Y, Chaudhary V, Yuen KS, Ho TH, Chan CP, Zhang Y, et al. A novel transcript isoform of STING that sequesters cGAMP and dominantly inhibits innate nucleic acid sensing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:4054–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li X, Zhu Y, Zhang X, An X, Weng M, Shi J, Wang S, Liu C, Luo S, Zheng T. An alternatively spliced STING isoform localizes in the cytoplasmic membrane and directly senses extracellular cGAMP. J Clin Invest. 2022;132(3):e144339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodriguez-Garcia E, Olague C, Rius-Rocabert S, Ferrero R, Llorens C, Larrea E, Fortes P, Prieto J, Gonzalez-Aseguinolaza G, Nistal-Villan E. TMEM173 Alternative Spliced Isoforms Modulate Viral Replication through the STING Pathway. Immunohorizons. 2018;2:363–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen H, Pei R, Zhu W, Zeng R, Wang Y, Wang Y, Lu M, Chen X. An alternative splicing isoform of MITA antagonizes MITA-mediated induction of type I IFNs. J Immunol. 2014;192:1162–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han L, Zheng Y, Deng J, Nan ML, Xiao Y, Zhuang MW, Zhang J, Wang W, Gao C, Wang PH. SARS-CoV-2 ORF10 antagonizes STING-dependent interferon activation and autophagy. J Med Virol. 2022;94:5174–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pyeon D, Lambert PF, Ahlquist P. Production of infectious human papillomavirus independently of viral replication and epithelial cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9311–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fang R, Wang C, Jiang Q, Lv M, Gao P, Yu X, Mu P, Zhang R, Bi S, Feng JM, Jiang Z. NEMO-IKKbeta Are Essential for IRF3 and NF-kappaB Activation in the cGAS-STING Pathway. J Immunol. 2017;199:3222–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gui X, Yang H, Li T, Tan X, Shi P, Li M, Du F, Chen ZJ. Autophagy induction via STING trafficking is a primordial function of the cGAS pathway. Nature. 2019;567:262–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmid M, Fischer P, Engl M, Widder J, Kerschbaum-Gruber S, Slade D. The interplay between autophagy and cGAS-STING signaling and its implications for cancer. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1356369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo F, Liu X, Cai H, Le W. Autophagy in neurodegenerative diseases: pathogenesis and therapy. Brain Pathol. 2018;28:3–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang C, Shang G, Gui X, Zhang X, Bai XC, Chen ZJ. Structural basis of STING binding with and phosphorylation by TBK1. Nature. 2019;567:394–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ergun SL, Fernandez D, Weiss TM, Li L. STING Polymer Structure Reveals Mechanisms for Activation, Hyperactivation, and Inhibition. Cell. 2019;178(290–301): e210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu YW, Zhang J, Wu XM, Cao L, Nie P, Chang MX. TANK-Binding Kinase 1 (TBK1) Isoforms Negatively Regulate Type I Interferon Induction by Inhibiting TBK1-IRF3 Interaction and IRF3 Phosphorylation. Front Immunol. 2018;9:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li C, Ma L, Chen X. Interferon regulatory factor 3-CL, an isoform of IRF3, antagonizes activity of IRF3. Cell Mol Immunol. 2011;8:67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han KJ, Yang Y, Xu LG, Shu HB. Analysis of a TIR-less splice variant of TRIF reveals an unexpected mechanism of TLR3-mediated signaling. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:12543–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qi N, Shi Y, Zhang R, Zhu W, Yuan B, Li X, Wang C, Zhang X, Hou F. Multiple truncated isoforms of MAVS prevent its spontaneous aggregation in antiviral innate immune signalling. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma F, Li B, Yu Y, Iyer SS, Sun M, Cheng G. Positive feedback regulation of type I interferon by the interferon-stimulated gene STING. EMBO Rep. 2015;16:202–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang C, Nan J, Holvey-Bates E, Chen X, Wightman S, Latif MB, Zhao J, Li X, Sen GC, Stark GR, Wang Y. STAT2 hinders STING intracellular trafficking and reshapes its activation in response to DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120: e2216953120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang BC, Laursen MF, Hu L, Hazrati H, Narita R, Jensen LS, Hansen AS, Huang J, Zhang Y, Ding X, et al. Cholesterol-binding motifs in STING that control endoplasmic reticulum retention mediate anti-tumoral activity of cholesterol-lowering compounds. Nat Commun. 2024;15:2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hsin F, Hsu YC, Tsai YF, Lin SW, Liu HM. The transmembrane serine protease hepsin suppresses type I interferon induction by cleaving STING. Sci Signal. 2021;14(687):eabb4752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ouyang S, Song X, Wang Y, Ru H, Shaw N, Jiang Y, Niu F, Zhu Y, Qiu W, Parvatiyar K, et al. Structural analysis of the STING adaptor protein reveals a hydrophobic dimer interface and mode of cyclic di-GMP binding. Immunity. 2012;36:1073–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.