Abstract

Background

Achieving the sustainable development goal target 3.4 requires an all-hand-on-deck approach. Healthcare professionals are expected to provide health advice on lifestyle changes that will reduce the risk of developing non-communicable diseases, or improve the quality of life of those who already have the condition. The study examined the prevalence and correlates of receiving health advice among adults in Cape Verde.

Methods

We analyzed the data 1,098 adults aged 18–69 years who participated in the 2020 WHO STEPS survey. All estimates were weighted. Bivariable and multivariable logistic regression were performed to assess correlates of receiving at least one health advice. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, with 95% confidence intervals reported.

Results

Overall, 60.4% (95%CI: 55.3, 62.3) of adults in Cape Verde had received at least one health advice. Compared to younger adults (< 30 years), individuals aged 30–59 years having 1.55 times higher odds (AOR = 1.55, 95%CI: 1.11–2.15) and those aged 60 years and older having nearly three times the odds (AOR = 2.93, 95%CI: 1.71–5.02) of receiving advice. Previously married (AOR = 1.69, 95%CI: 1.09–2.61) and cohabiting individuals had higher odds (AOR = 1.56, 95%CI: 1.12–2.18) of receiving advice compared to those who were never married. Alcohol consumption was inversely associated with receiving advice, as drinkers had 40% lower odds of receiving advice compared to non-drinkers (AOR = 0.60, 95%CI: 0.45–0.81). Individuals consuming fewer than four servings of fruit per day had significantly lower odds of receiving advice (AOR = 0.58, 95%CI: 0.37–0.90), while those consuming fewer than four servings of vegetables per day had 1.41 times higher odds (AOR = 1.41, 95%CI: 1.06–1.88). The likelihood of receiving health advice was high among those living with hypertension (AOR = 1.94, 95%CI: 1.41–2.65).

Conclusion

Evidence from this study suggests that there is a moderately high prevalence of receiving health advice in Cape Verde. The key correlates are hypertension status, increasing age, marital status, alcohol consumption and dietary habits. The findings underscore the need for targeted health education and counseling strategies that address the unique needs of different population subgroups, particularly younger adults, non-drinkers, and those with suboptimal dietary habits, to ensure equitable access to health advice.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s41043-025-00923-1.

Keywords: Health behavior, Health education, Health promotion, Public health, Non-communicable diseases

Background

The increasing trend of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) worldwide is a matter of urgent public health concern [1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) [2], NCDs accounted for 43 million deaths in 2021, with 73% of these deaths occurring in low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs). In Cape Verde, an estimated 7.8% and 3.9% of adults aged 18–69 years were living with pre-diabetes and diabetes, respectively [3]. Approximately, a quarter of the adult population (25%) live with hypertension [4]. Another study also showed that NCDs and trauma accounted for more than 40% of deaths between 1995 and 2018 [5].

Literature from Cape Verde attributes the high burden of NCDs to urbanicity [3, 6]. However, the larger body of scholarly works highlight the contribution of lifestyle factors including diet, physical activity, alcohol consumption and smoking to NCD prevalence [2, 3, 7, 8]. Qiao et al. [8] revealed that in 2019, nearly 7.9 million deaths and 187.7 million DALYs were attributable to dietary risk factors. Okyere et al. [3] also reported that in Cape Verde, consuming less than four servings of vegetables per day increased the risk of diabetes by 74%. A systematic review of prospective observational studies found that increased physical activity significantly reduced mortality rate by 30% among those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and 4% decline among those living with diabetes [9]. This suggests that lifestyle changes are not only good for preventing NCDs, but are also critical to reducing mortalities among those who have already developed chronic diseases.

In recognition of the cascading adverse effects of NCDs, the sustainable development goal target 3.4 envisions reducing premature mortality from NCDs by one third, through prevention and treatment by 2030 [2, 10, 11]. Achieving this target requires an all-hand-on-deck approach. This means that healthcare providers have a critical role to play. A systematic review by Jeet et al. [12] shows that the involvement of healthcare professionals in the prevention and control of NCDs resulted in a significant increase in tobacco smoking cessation and a decline in systolic/diastolic blood pressure.

The role of health care professionals in NCD control include performing screening services and implementing lifestyle change interventions [13]. Beyond these roles, healthcare professionals are expected to provide health counseling or advice on lifestyle changes that will reduce the risk of developing NCDs, or improve the quality of life of those who already have the condition [14–16]. Despite the importance of health advice/counseling on NCDs, not all persons receive such health messages. For example, Zwald et al. [15] found that less than half of adults (42.9%) in the United States received health advice on physical activity. In England, only 47.2% of past smokers had received health advice on smoking [16]. The extant studies were conducted in high-income countries that tend to have a much organized healthcare system than LMICs like Cape Verde. To the best of our knowledge, there is no published evidence of the prevalence of health advice in sub-Saharan Africa, and specifically in Cape Verde. Moreover, the previous studies [15, 16] focused on only one health advice. And so, we ask the following questions: (a) What proportion of adults in Cape Verde receive health advice? (b) What is the most prevalent health advice received? (c) What factors account for differences in the prevalence of health advice received? To this end the study aims to examine the prevalence and correlates of receiving health advice among adults in Cape Verde.

Methods

Data source and design

We analysed secondary data from the 2020 WHO STEPS survey. The WHO STEPS survey is a nationally representative survey that evaluates risk factors for NCDs in Cape Verde [3, 17]. Conducted between February and March 2020, the survey employed a structured three-step methodology. In Step 1, detailed socio-demographic and behavioral data were collected [6, 7]. Step 2 involved taking physical measurements such as height, weight, and blood pressure. In Step 3, blood and urine samples were gathered for biochemical analysis, including assessments of blood glucose, cholesterol levels, and salt intake [3, 7]. The survey targeted a population-based sample of adults aged 18–69 years. To ensure the sample was representative of the data, a multi-stage probability sampling design was used. A total of 4,563 adults participated in Steps 1 and 2, with a subsample of 2,436 adults completing Step 3 [3]. However, for this study, we analyzed data from 1,098 adults who had complete data on the health advice question.

Study variables

Outcome variables

Receiving at least one health advice was the outcome variable. This was created a composite variable from seven health advices: smoking cessation, reducing salt intake, eating more fruits and vegetables, reducing fat consumption, increasing physical activity, weight loss, and reducing sugary beverages. Each of the advices had a binary response of 1 = yes or 0 = no. We then used the ‘egen’ command in STATA to create the composite variable by summing the binary responses across all seven advice categories. If the sum was greater than or equal to 1, the individual was coded as having received at least one health advice (1 = yes); otherwise, they were coded as not having received any advice (0 = no).

Explanatory variables

Socio-demographic, biochemical and physical factors were selected as explanatory variables based on their empirical and theoretical relevance [15, 16]. These included hypertension status, age, sex, educational level, marital status, alcohol intake, fruit and vegetable consumption, overweight/obesity status, total cholesterol level, and sedentary behavior. Total cholesterol was divided into two categories: ‘normal’ (< 194 mg/dL) and ‘high’ (≥ 194 mg/dL) [3]. Body mass index (BMI) was categorized as follows: a BMI of ≤ 18.49 was considered ‘underweight,’ 18.5–24.99 as ‘normal,’ and a BMI of ≥ 25 as ‘overweight/obese’ [18]. Hypertension was assessed by averaging three measurements of both systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Participants were defined as hypertensive if their average systolic BP was ≥ 140 mmHg or their average diastolic BP was ≥ 90 mmHg [19].

Statistical analyses

Originally 4,563 adults participated in Steps 1 and 2, however only 2,436 adults moved on to complete Step 3. Missing values from the remaining 2,436 observations were dropped from the analysis (n = 1,338). Thus, bringing the analytical sample size to 1,098 (see Fig. 1). All estimates were weighted. To account for complex survey design, we adjusted for the primary sampling unit and stratification cluster using the ‘svyset’ command in STATA version 18 (RRID: SCR_012763). We estimated the prevalence of receiving health advice and performed cross-tabulations to show the distribution of the prevalence across the participants’ characteristics. Two sets of binary logistic regression were computed. The first model assessed the unadjusted association between the participants’ characteristics and the likelihood of receiving health advice. Model II was a multivariable logistic regression model that assessed adjusted correlations of receiving health advice. The multivariable model was built using a backward stepwise approach where all selected variables were initially included, and non-significant variables (p ≥ 0.05) were iteratively removed. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The results from the multivariable logistic regression were presented in adjusted odds ratio along with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

Fig. 1.

Analytical sample process flowchart

Results

Characteristics of study participants

Table 1 shows the weighted sample distribution. Most participants were women (56.4%), aged 30–59 years (62.5%), had secondary education (69.7%), were never married (48.7%), and resided in urban areas (71.2%). For the health factors, most participants were living with hypertension (28.7%), consumed alcohol (73.1%), consumed < 4 servings/day of fruits (87.3%) and vegetables (67.4%). Also, 17% were living with high total cholesterol; 12.9% lived a sedentary life, while 7.3% were current smokers. Almost half (48.8%) of the participants were overweight/obese.

Table 1.

Weighted sample distribution

| Characteristic | Weighted sample (n) | Weighted proportions (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | ||

| No | 783 | 71.3 |

| Yes | 315 | 28.7 |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 478 | 43.6 |

| Women | 620 | 56.4 |

| Age Group | ||

| < 30 years | 315 | 28.6 |

| 30–59 years | 687 | 62.5 |

| 60 + years | 97 | 8.8 |

| Education Level | ||

| No formal education | 42 | 3.8 |

| Primary/basic | 30 | 2.8 |

| Secondary | 765 | 69.7 |

| Tertiary | 260 | 23.7 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Never married | 535 | 48.7 |

| Married | 178 | 16.2 |

| Previously married | 90 | 8.2 |

| Cohabiting | 295 | 26.9 |

| Residence | ||

| Rural | 317 | 28.8 |

| Urban | 781 | 71.2 |

| Alcohol Consumption | ||

| No | 295 | 26.9 |

| Yes | 803 | 73.1 |

| Fruit Intake | ||

| ≥ 4 servings/day | 139 | 12.7 |

| < 4 servings/day | 959 | 87.3 |

| Vegetable Intake | ||

| ≥ 4 servings/day | 358 | 32.6 |

| < 4 servings/day | 740 | 67.4 |

| High Cholesterol | ||

| No | 911 | 83.0 |

| Yes | 187 | 17.0 |

| Sedentary Behavior | ||

| No | 956 | 87.1 |

| Yes | 142 | 12.9 |

| Current Smoking | ||

| No | 1,018 | 92.7 |

| Yes | 80 | 7.3 |

| Overweight/obese | ||

| No | 566 | 51.6 |

| Yes | 532 | 48.4 |

Prevalence of health advice by participant characteristics

Overall, 60.4% (95%CI: 55.3, 62.3) of adults in Cape Verde had received health advice (Table 2). The prevalence of receiving health advice was significantly high among persons living with hypertension (70.4%), those aged 60 years and older (82.6%), cohabiting adults (71.0%), those consuming fewer than four servings of fruit per day (58.2%), and those who were obese (65.3%).

Table 2.

Prevalence of health advice by participant characteristics

| Characteristic | Weighted sample (n) |

Weighted proportion that received health advice (% [95%CI]) |

p-values (Chi-Square Test) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 664 | 60.4 [55.3, 65.3] | |

| Hypertension | 0.010 | ||

| No | 442 | 56.4 [50.3, 62.3] | |

| Yes | 222 | 70.4 [61.4, 78.1] | |

| Gender | 0.826 | ||

| Men | 285 | 59.8 [52.0, 67.1] | |

| Women | 403 | 60.9 [53.9, 67.6] | |

| Age Group | 0.001 | ||

| < 30 years | 161 | 50.8 [41.8, 59.8] | |

| 30–59 years | 445 | 61.9 [54.9, 68.3] | |

| 60 + years | 82 | 82.6 [73.6, 88.9] | |

| Education Level | 0.082 | ||

| No formal education | 32 | 70.5 [51.6, 84.3] | |

| Primary/basic | 22 | 61.4 [36.2, 81.7] | |

| Secondary | 495 | 64.0 [58.9, 68.7] | |

| Tertiary | 140 | 50.1 [37.2, 63.1] | |

| Marital Status | 0.029 | ||

| Never married | 299 | 54.2 [46.3, 61.9] | |

| Married | 118 | 63.5 [51.8, 73.8] | |

| Previously married | 61 | 66.9 [53.5, 77.9] | |

| Cohabiting | 209 | 69.6 [61.2, 76.8] | |

| Residence | 0.823 | ||

| Rural | 198 | 59.5 [50.1, 68.3] | |

| Urban | 490 | 60.8 [54.7, 66.6] | |

| Alcohol Consumption | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 216 | 74.6 [67.0, 81.0] | |

| Yes | 472 | 55.8 [49.9, 61.6] | |

| Fruit Intake | 0.005 | ||

| ≥ 4 servings/day | 108 | 76.3 [64.4, 85.2] | |

| < 4 servings/day | 580 | 58.2 [52.8, 63.3] | |

| Vegetable Intake | 0.259 | ||

| ≥ 4 servings/day | 220 | 56.2 [46.4, 65.6] | |

| < 4 servings/day | 467 | 62.6 [56.9, 67.9] | |

| High Cholesterol | 0.475 | ||

| No | 551 | 59.8 [53.9, 65.4] | |

| Yes | 137 | 63.7 [54.3, 72.1] | |

| Sedentary Behavior | 0.919 | ||

| No | 609 | 60.4 [54.8, 65.7] | |

| Yes | 79 | 61.0 [48.8, 72.0] | |

| Current Smoking | 0.763 | ||

| No | 638 | 60.6 [55.2, 65.8] | |

| Yes | 50 | 57.9 [40.4, 73.5] | |

| Overweight/obese | 0.049 | ||

| No | 328 | 55.9 [48.3, 63.2] | |

| Yes | 360 | 65.3 [59.0, 71.1] |

Disaggregation of health advice

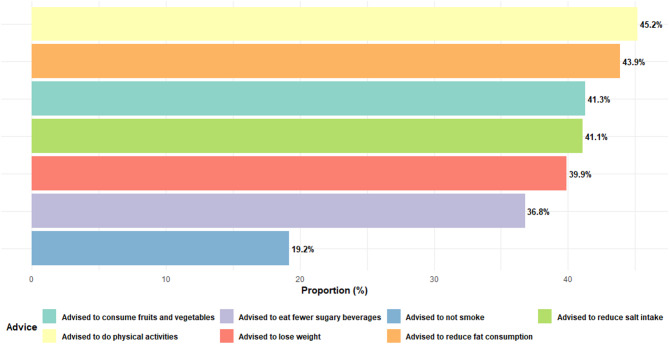

This study shows that advice on engagement in physical activities was the major advised given to adults in Cape Verde (45.2%). This was followed by advice to reduce fat consumption (43.9%), advice to consume fruits and vegetables (41.3%), and advice to reduce salt intake (41.1%) (see Fig. 2). Advice against smoking was the least provided health advice (19.2%).

Fig. 2.

Bar plot showing the percentage distribution of health advice by type

Disaggregation of health advice by participants’ characteristics

Among age groups, older adults (60 + years) were the most frequently advised to reduce salt intake (64.7%), eat fewer sugary beverages (49.2%), and engage in physical activities (57.8%), whereas younger participants (< 30 years) received the least advice across all categories. Gender differences indicate that women were more likely than men to be advised on dietary changes, such as reducing fat intake (50.2% vs. 35.9%) and eating fruits and vegetables (45.5% vs. 35.7%). In terms of residence, rural dwellers were more often advised to lose weight (49.4%) compared to their urban counterparts (36.5%). Educational disparities are evident, with individuals having no formal education receiving the highest percentage of advice on salt reduction (66.2%) and weight loss (56.9%), whereas tertiary-educated individuals received the least advice across most categories.

Lifestyle behaviors also influenced advice received, with non-smokers (42.0%) and non-drinkers (54.3%) being more frequently counseled on reducing salt intake compared to smokers (29.9%) and drinkers (36.2%). Individuals with hypertension were more frequently advised to reduce salt intake (54.9%), eat fewer sugary beverages (41.9%), and engage in physical activities (53.1%) compared to those without hypertension. Similarly, individuals with high total cholesterol levels were more likely to receive advice on dietary modifications, such as reducing fat intake (50.1%) and eating fruits and vegetables (50.1%), than those with normal cholesterol levels. Sedentary behavior also influenced health counseling, with sedentary individuals receiving less advice on salt reduction (27.5%) compared to their more active counterparts (43.1%). However, sedentary individuals were more frequently advised to lose weight (43.4%) and reduce fat intake (45.1%) than those with active lifestyles. (see Fig. 3 & Supplementary file 1).

Fig. 3.

Disaggregated health advice by participants’ characteristics

See supplementary file 1 for actual percentages.

Correlates of receiving health advice among adults in cape Verde

Compared to younger adults (< 30 years), individuals aged 30–59 years having 1.55 times higher odds (AOR = 1.55, 95%CI: 1.11–2.15) and those aged 60 years and older having nearly three times the odds (AOR = 2.93, 95%CI: 1.71–5.02) of receiving advice. Previously married (AOR = 1.69, 95%CI: 1.09–2.61) and cohabiting individuals had higher odds (AOR = 1.56, 95%CI: 1.12–2.18) of receiving advice compared to those who were never married. Alcohol consumption was inversely associated with receiving advice, as drinkers had 40% lower odds of receiving advice compared to non-drinkers (AOR = 0.60, 95%CI: 0.45–0.81). Individuals consuming fewer than four servings of fruit per day had significantly lower odds of receiving advice (AOR = 0.58, 95%CI: 0.37–0.90), while those consuming fewer than four servings of vegetables per day had 1.41 times higher odds (AOR = 1.41, 95%CI: 1.06–1.88). The likelihood of receiving health advice was high among those living with hypertension (AOR = 1.94, 95%CI: 1.41–2.65) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlates of receiving health advice among adults in cape Verde

| Characteristic | Model I Crude Odds Ratio (95%CI) |

Model II Adjusted Odds Ratio (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | ||

| No | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 1.37 [1.01, 1.85]* | 1.94 [1.41, 2.65]** |

| Gender | ||

| Men | Ref. | - |

| Women | 1.28 [0.98, 1.67] | - |

| Age Group | ||

| < 30 years | Ref. | Ref. |

| 30–59 years | 1.93 [1.42, 2.63]*** | 1.55 [1.11, 2.15]* |

| 60 + years | 4.95 [3.09, 7.95]*** | 2.93 [1.71, 5.02]** |

| Education Level | ||

| No formal education | Ref. | - |

| Primary/basic | 0.82 [0.34, 1.99] | - |

| Secondary | 0.49 [0.27, 0.88]* | - |

| Tertiary | 0.38 [0.20, 0.72]** | - |

| Marital Status | ||

| Never married | Ref. | Ref. |

| Married | 2.10 [1.46, 3.01]*** | 1.44 [0.97, 2.14] |

| Previously married | 2.16 [1.42, 3.30]** | 1.69 [1.09, 2.61]* |

| Cohabiting | 1.63 [1.18, 2.24]** | 1.56 [1.12, 2.18]** |

| Residence | ||

| Rural | Ref. | - |

| Urban | 1.09 [0.85, 1.41] | - |

| Alcohol Consumption | ||

| No | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 0.56 [0.43, 0.75]*** | 0.60 [0.45, 0.81]** |

| Fruit Intake | ||

| ≥ 4 servings/day | Ref. | Ref. |

| < 4 servings/day | 0.69 [0.47, 1.01] | 0.58 [0.37, 0.90]* |

| Vegetable Intake | ||

| ≥ 4 servings/day | Ref. | Ref. |

| < 4 servings/day | 1.24 [0.96, 1.60] | 1.41 [1.06, 1.88]* |

| High Cholesterol | ||

| No | Ref. | - |

| Yes | 1.37 [1.01, 1.85]* | - |

| Sedentary Behavior | ||

| No | Ref. | - |

| Yes | 0.76 [0.52, 1.13] | - |

| Current Smoking | ||

| No | Ref. | - |

| Yes | 0.77 [0.46, 1.28] | - |

| Overweight/obese | ||

| No | Ref. | - |

| Yes | 1.38 [1.07, 1.77]* | - |

***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05; Ref: reference category

(-) variables excluded after application of a backward stepwise approach

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to examine the prevalence and correlates of receiving health advice in Cape Verde. Our study showed that a moderate (60.4%) proportion of adults in Cape Verde received health advice. This is higher than the 42.9% and 47.2% reported in the United States and England, respectively [15, 16]. Our study was more comprehensive than the previous studies that focused only on advice to increase physical activity [15] and smoking cessation advice [16], and thus, may explain the difference. The disaggregated data suggests that advice on physical activity was the most prevalent advice received by adults in Cape Verde. This is consistent with an earlier study conducted in North Carolina that reported a 47.1% prevalence of advice to exercise as against other health advice (lose weight = 35.4%, quit smoking = 29.4%, reduce salt intake = 25.5%, reduce alcohol = 10.2%) [20].

Regarding the correlates, we found that increasing age was associated with higher odds of receiving health advice. The observed association is consistent with MacGeorge and Van Swol [21] who argue that older adults are more receptive to health advice. The authors [21] further posit that older adults believe that health professionals are motivated by concern for their health [21]. This finding also aligns with existing literature [15, 22] that emphasizes the prioritization of older populations in preventive healthcare due to their increased vulnerability to NCDs such as diabetes, and cardiovascular conditions. Healthcare providers may perceive older adults as a high-risk group requiring more frequent interventions, which could explain this trend. However, the lower likelihood of younger individuals receiving advice raises concerns about missed opportunities for early intervention. Targeting younger populations with preventive advice could help mitigate long-term health risks and promote healthier lifestyle choices earlier in life.

We also found that individuals who were previously married or cohabiting had significantly higher odds of receiving advice compared to those who were never married. Our finding resonates with another study conducted in the United States [23] that found a significantly higher prevalence of receiving advice among previously and currently married people. This suggests that social support systems, including family dynamics and living arrangements, may influence health communication. Married or cohabiting individuals may have greater access to shared decision-making or encouragement from partners, prompting healthcare providers to engage them more actively in discussions about health behaviors. Conversely, the lower likelihood of never-married individuals receiving advice highlights potential disparities in health communication that warrant further exploration.

Consistent with previous studies [15, 20], we affirmed that living with a hypertension increased the likelihood of receiving health advice by 94%. Hypertension is a major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, and its management through lifestyle modifications and medical interventions is a cornerstone of preventive care [24, 25]. As such, the higher likelihood of hypertensive individuals to receive health advice reflects the alignment of clinical practice with evidence-based guidelines. A plausible explanation for this observation could be that individuals diagnosed with hypertension are likely to have more frequent interactions with healthcare providers, which increases the opportunities for clinicians to offer tailored advice on lifestyle modifications.

In contrast to our expectations, we found an inverse association between alcohol consumption and the odds of receiving health advice. Individuals who consumed alcohol had 40% lower odds of receiving advice compared to non-drinkers. This result is concerning, as excessive alcohol consumption is a well-established risk factor for numerous health conditions, including liver disease, cardiovascular disorders, and certain cancers [26, 27]. Evidence also shows that moderate to heavy alcohol users are also more likely to have unhealthy lifestyles overall, characterized by a poor diet and smoking, as well as consumption of foods high in fat and sugar [28, 29]. We postulate that the observed association may be evidence of self-selection where individuals who consume alcohol might be less receptive to health interventions or less likely to seek guidance proactively. Dietary habits also emerged as a significant correlated of receiving health advice, though the patterns differed for fruit and vegetable intake. We observed that individuals who consumed fewer than four servings of fruit per day had significantly lower odds of receiving health advice, however, those consuming fewer than four servings of vegetables per day had 1.41 times higher odds of receiving health advice. It is unclear why this disparity exist. We suggest that this discrepancy may reflect differing perceptions of dietary priorities among healthcare providers, with vegetables potentially viewed as a more critical component of a healthy diet.

Strengths and limitations

This study is arguably the first in sub-Saharan Africa and Cape Verde to profile the receipt of health advice. Also, the strategy of considering more than one health advice is another strength as it contributes to the comprehensiveness of our study. The multi-stage sampling technique employed in the WHO STEPS together with the application of sample weights guarantees the generalizability of our findings. While this study provides valuable insights, several limitations are acknowledged. The cross-sectional design limits causal inference, and unmeasured confounders may still influence the observed associations. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data for variables such as dietary habits introduces the possibility of recall bias. Since the study was based on secondary data, other key confounders such as quality and frequency of patient-provider interaction were not factored in regression model. In the future, qualitative studies exploring patient-provider interactions could also provide deeper insights into the barriers and facilitators of effective health communication. Future research should also employ longitudinal designs to assess the impact of health advice on behavioral and health outcomes over time.

Conclusion

Evidence from this study suggests that there is a moderately high prevalence of receiving health advice in Cape Verde. The key correlates are hypertension status, increasing age, marital status, alcohol consumption and dietary habits. The findings underscore the need for targeted health education and counseling strategies that address the unique needs of different population subgroups, particularly younger adults, non-drinkers, and those with suboptimal dietary habits, to ensure equitable access to health advice.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the WHO for granting us free access to the dataset used in this study.

Abbreviations

- AOR

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- CI

Confidence Interval

- LMICs

Low-and-middle-income Countries

- NCD

Non-communicable Diseases: WHO: World Health Organization

Author contributions

JO and CA conceptualized and designed the study. JO curated the data and performed the formal analyses. JO and CA drafted the initial manuscript. KSD reviewed the initial manuscript for its accuracy. All authors reviewed the final manuscript and approved its submission. JO had the final responsibility of submitting the manuscript.

Funding

None.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the WHO NCD Microdata Repository: https://extranet.who.int/ncdsmicrodata/index.php/catalog/935. Accession number/ID: CPV_2020_STEPS_v01.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We did not seek ethical approval as this has already been done for all the STEPS surveys of NCD risk factors. However, ethical approval for the 2020 WHO STEPS survey was granted by the National Ethics Committee for Health Research and the Data Protection Commission (CNEPS). We formally requested the data from the WHO NCD Microdata Repository: https://extranet.who.int/ncdsmicrodata/index.php/home.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Taheri Soodejani M. Non-communicable diseases in the world over the past century: a secondary data analysis. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1436236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Non-communicable diseases: key facts. 23. Dec. 2024 [Internet]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases. Accessed 3 February, 2025.

- 3.Okyere J, Ayebeng C, Dickson KS. Prevalence of diabetes and its associated factors in cape Verde: an analysis of the 2020 WHO STEPS survey on non-communicable diseases risk factors. BMC Endocr Disorders. 2024;24(1):264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases (NCD) country profiles. 2018. Cabo Verde (Pp.55–56). n.d. Available: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/country-profiles/ncds/cpv_en.pdf?sfvrsn=631ced05_37&download=true

- 5.Varela DV, Martins MD, Furtado A, Mendonça MD, Fernandes NM, Santos I, Lopes ED. Spatio-temporal evolution of mortality in cape Verde: 1995–2018. PLOS Global Public Health. 2023;3(3):e0000753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christian AK, Osei-Appaw AA, Sawyerr RT, Wiredu Agyekum M. Hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease nexus: investigating the role of urbanization and lifestyle in Cabo Verde. Global Health Action. 2024;17(1):2414524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Behavioural and biological risk factors of non-communicable diseases among adults in Cabo Verde: a repeated cross-sectional study of the 2007 and 2020 National community-based surveys. BMJ Open. 2023;13(8):e073327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qiao J, Lin X, Wu Y, Huang X, Pan X, Xu J, Wu J, Ren Y, Shan PF. Global burden of non-communicable diseases attributable to dietary risks in 1990–2019. J Hum Nutr Dietetics. 2022;35(1):202–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geidl W, Schlesinger S, Mino E, Miranda L, Pfeifer K. Dose–response relationship between physical activity and mortality in adults with noncommunicable diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity. 2020;17:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennett JE, Kontis V, Mathers CD, Guillot M, Rehm J, Chalkidou K, Kengne AP, Carrillo-Larco RM, Bawah AA, Dain K, Varghese C. NCD countdown 2030: pathways to achieving sustainable development goal target 3.4. Lancet. 2020;396(10255):918–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frieden TR, Cobb LK, Leidig RC, Mehta S, Kass D. Reducing premature mortality from cardiovascular and other non-communicable diseases by one third: achieving sustainable development goal indicator 3.4. 1. Global Heart. 2020;15(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Jeet G, Thakur JS, Prinja S, Singh M. Community health workers for non-communicable diseases prevention and control in developing countries: evidence and implications. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(7):e0180640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Babagoli MA, Nieto-Martínez R, González-Rivas JP, Sivaramakrishnan K, Mechanick JI. Roles for community health workers in diabetes prevention and management in low-and middle-income countries. Cadernos De Saude Publica. 2021;37(10):e00287120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinto GS, Bader L, Billberg K, Criddle D, Duggan C, El Bizri L, Gharat M, Hogue MD, Jacinto I, Oyeneyin Y, Zhou Y. Beating non-communicable diseases in primary health care: the contribution of pharmacists and guidance from FIP to support WHO goals. Res Social Administrative Pharm. 2020;16(7):974–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zwald ML, Kit BK, Fakhouri TH, Hughes JP, Akinbami LJ. Prevalence and correlates of receiving medical advice to increase physical activity in US adults: National health and nutrition examination survey 2013–2016. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(6):834–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson SE, Garnett C, Brown J. Prevalence and correlates of receipt by smokers of general practitioner advice on smoking cessation in England: a cross-sectional survey of adults. Addiction. 2021;116(2):358–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okyere J, Ayebeng C, Dickson KS. State of multi-morbidity among adults in Cape Verde: findings from the 2020 WHO STEPS non-communicable disease survey. J Public Health. 2025;fdaf031. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Kim SY. The definition of obesity. Korean J Family Med. 2016;37(6):309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kandil H, Soliman A, Alghamdi NS, Jennings JR, El-Baz A. Using mean arterial pressure in hypertension diagnosis versus using either systolic or diastolic blood pressure measurements. Biomedicines. 2023;11(3):849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corsino L, Svetkey LP, Ayotte BJ, Bosworth HB. Patient characteristics associated with receipt of lifestyle behavior advice. N C Med J. 2009;70(5):391. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacGeorge EL, Van Swol LM, editors. The Oxford handbook of advice. Oxford University Press; 2018.

- 22.Barnes PM, Schoenborn CA. Trends in adults receiving a recommendation for exercise or other physical activity from a physician or other health professional. [PubMed]

- 23.Danesh D, Paskett ED, Ferketich AK. Peer reviewed: disparities in receipt of advice to quit smoking from health care providers: 2010 National health interview survey. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Samuel PO, Edo GI, Emakpor OL, Oloni GO, Ezekiel GO, Essaghah AE, Agoh E, Agbo JJ. Lifestyle modifications for preventing and managing cardiovascular diseases. Sport Sci Health. 2024;20(1):23–36. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valenzuela PL, Carrera-Bastos P, Gálvez BG, Ruiz-Hurtado G, Ordovas JM, Ruilope LM, Lucia A. Lifestyle interventions for the prevention and treatment of hypertension. Nat Reviews Cardiol. 2021;18(4):251–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Åberg F, Byrne CD, Pirola CJ, Männistö V, Sookoian S. Alcohol consumption and metabolic syndrome: clinical and epidemiological impact on liver disease. J Hepatol. 2023;78(1):191–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Georgescu OS, Martin L, Târtea GC, Rotaru-Zavaleanu AD, Dinescu SN, Vasile RC, Gresita A, Gheorman V, Aldea M, Dinescu VC. Alcohol consumption and cardiovascular disease: A narrative review of evolving perspectives and Long-Term implications. Life. 2024;14(9):1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Positive Choices [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 4]. The link between substance use, mental health, and other lifestyles. Available from: https://positivechoices.org.au/teachers/lifestyle-behaviours

- 29.Crovetto M, Valladares M, Oñate G, Fernández M, Mena F, Agüero SD, Espinoza V. Association of weekend alcohol consumption with diet variables, body mass index, cardiovascular risk and sleep. Hum Nutr Metabolism. 2022;27:200140. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the WHO NCD Microdata Repository: https://extranet.who.int/ncdsmicrodata/index.php/catalog/935. Accession number/ID: CPV_2020_STEPS_v01.