Abstract

Background

National prevalence estimates of exclusive breastfeeding practices could serve as the basis for future policy efforts and specific interventions. However, little is known about the prevalence and factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding practices in Afghanistan. This study aims to determine the prevalence and factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding practices among infants aged 0–5 months in Afghanistan.

Methods

Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) data collected between 2022 and 2023 were used for this analysis. Data from 3,141 mother-infant dyads were included in the study. The outcome variable was exclusive breastfeeding (EBF), defined as the proportion of infants 0–5 months of age who were fed only breast milk in the past 24 h. Binary logistic regression models were applied to examine the likelihood of EBF across the categories of independent variables.

Results

In the studied population, 67.0% (95%CI 65%-69%) of the infants were exclusively breastfed. The likelihood of EBF was higher in infants born to mothers with secondary or higher education [AOR = 1.35, 95%CI 1.04–1.76] and in infants with timely initiation of breastfeeding [AOR = 1.25, 95%CI 1.07–1.46]. However, the female sex of the infant was associated with lower odds of EBF practices [AOR = 0.83, 95%CI 0.72–0.97].

Conclusion

The practice of exclusive breastfeeding is at a good level (67%) in Afghanistan. Higher maternal education level, timely breastfeeding initiation, and being a male infant increased the likelihood of EBF practices. Policy efforts and interventions focused on these factors could enhance EBF practices in Afghanistan.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s41043-025-00963-7.

Keywords: Exclusive breastfeeding, Prevalence, Determinants, Afghanistan

Introduction

Breastfeeding is universally recognized as one of the most effective practices that plays a critical role in ensuring infant survival, health, and development, especially in resource-limited settings [1, 2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) strongly advocate for exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) during the first six months of life, followed by continued breastfeeding along with appropriate complementary foods until at least two years of age [3, 4]. EBF is associated with a myriad of health benefits, including optimal growth and development, enhanced immune function, reduced risk of infant mortality, and strengthening the bond between the mother and child [5–8]. Despite these benefits, malnutrition continues to be a significant global challenge, contributing to 45% of deaths among children under five [9]. Each year, an estimated 16% of global deaths among children under the age of two are attributed to inadequate breastfeeding [10].

Afghanistan faces significant health challenges, including high rates of under-five and neonatal mortality, pervasive malnutrition, and limited access to healthcare services [11, 12]. These challenges are exacerbated by socioeconomic disparities, low levels of maternal education, and inadequate health infrastructure [13, 14]. The under-five mortality rate is 56 per 1,000 live births, while neonatal mortality stands at 34 per 1,000 [15]. Additionally, low immunization rates (55–65%) and limited access to safe drinking water (only 28% of the population) further exacerbate the risk of infectious and waterborne diseases [15, 16]. Stunting affects 44.7% of Afghan children under five, reflecting chronic undernutrition linked to inadequate feeding practices during infancy [15, 17, 18]. Exclusive breastfeeding is particularly vital in humanitarian settings, where limited access to clean water and nutritious food increases the risk of malnutrition and disease among infants, underlining breastfeeding as a crucial strategy to reduce infant mortality [1, 5, 7, 19]. In Afghanistan, research indicates that not breastfeeding, particularly in the first two days after birth, significantly increases the risk of neonatal mortality [20]. Moreover, EBF contributes to birth spacing, further improving maternal and child health outcomes [19]. Breastmilk is an irreplaceable resource, offering safety, availability, and affordability, especially in times of crisis [5, 7]. Given this evidence, promoting EBF in Afghanistan emerges as a critical strategy for improving child survival and health outcomes.

EBF practices are influenced by various socio-demographic and economic factors. Studies have shown that timely initiation of breastfeeding, maternal education, and socio-economic status are important determinants of EBF [7, 17, 21, 22]. Additionally, cultural factors, access to healthcare, and media exposure can also play significant roles [2, 5]. Understanding these determinants is essential for designing targeted interventions to enhance EBF rates and, consequently, improve child health outcomes in Afghanistan. Involving the mother’s immediate social network is another key aspect of encouraging breastfeeding [1, 5, 7, 19]. Evidence suggests that family and husband support during lactation play crucial roles in achieving successful breastfeeding [5, 7, 19, 23]. Additionally, providing comfortable and private spaces for breastfeeding has been recognized as an enabling factor in promoting successful breastfeeding [5].

Early evidence from published studies suggests that the EBF rate is suboptimal in Afghanistan [24]. A study from Kandahar province reports a 51.8% EBF rate in a sample of 1,028 mothers [25]. However, to our knowledge, the updated prevalence and determinants of EBP at a national level have not been documented [26]. Therefore, this study draws on data from the recent 2022–23 Afghanistan Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS), a comprehensive nationwide survey, to explore the key determinants of EBF among infants aged 0–5 months. The findings of this study could serve as the basis for future policy efforts and specific interventions to enhance EBF practices in Afghanistan.

Methods

Data source

We used data from the MICS 2022–2023, which gathered data from a nationally representative sample in Afghanistan [27]. The primary objectives of the survey include providing high-quality data for evaluating the conditions of children, adolescents, women, and households; monitoring progress toward national targets; identifying disparities for social inclusion; validating intervention outcomes; and generating data for Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) indicators. Data collection and sampling approaches are described elsewhere [27]. During MICS, trained surveyors collected data from households with reproductive-age women. Women were asked questions about breastfeeding practices and about their sociodemographic characteristics. In this study, we used data from 3,141 mother-infant dyads who had complete information on variables.

Study variables

The outcome variable was defined according to the WHO definition of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) [28]. Data analysis was restricted to infants aged 0–5 months of age and the outcome variable was coded binary (yes/no) to indicate whether the infant has been fed only breast milk in the last 24 h [28, 29]. Oral rehydration salts (ORS), drops or syrups of vitamins, minerals, and medicines were not considered supplementary food [28]; thus, children who received them while being breastfed were not excluded from data analysis.

The independent variables were selected in light of the literature [21, 25, 30–37]. The independent variables were timely breastfeeding (yes vs. no) which was defined as the initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of birth, number of child born (one child vs. 2 and more children), infant sex (male vs. female), mother’s age (15–29, 30–39, 40–49 years), mother’s education (no formal education, primary education, secondary/higher education), residential area (urban vs. rural), wealth index (lowest quintile up to highest quintile), antenatal care (ANC) utilization during pregnancy (yes vs. no), place of delivery (home vs. clinic/hospital), postnatal care (PNC) utilization for the newborn (yes vs. no), mother watches TV daily (yes vs. no), mother listens to radio daily (yes vs. no), and mother has used mobile phone at least once a week in the last 3 months (yes vs. no). Detailed information on independent variables selection and their relevance to EBF practices are available in the supplementary file 1.

Statistical analysis

We conducted descriptive statistics to describe the basic characteristics of mother-infant dyads. Binary logistic regression models were fitted and applied to examine the likelihood of EBF across the categories of independent variables. We provided unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) from binary logistic regression analyses. We added a random cluster effect in the model to take the clustering effects of data at the household level into account, and to provide adjusted standard errors for the ORs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). STATA version 17 was used for the data analyses. The significant statistical level was set at 0.05.

Results

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of 3,141 mother-infant dyads. Of 3,141 infants, 45.1% of them were breastfed within the first hour of birth. Further, 48.3% of them were girls, 17.0% of them were first-order children, and 33.3% of them had their health checked after birth. Nearly two-thirds (63.8%) of infants’ mothers were 15–29 years of age, and 80.2% of mothers had no formal education (details in Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for 3,141 mother-infant dyads

| Characteristics | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Mother’s age | |

|

15–29 30–49 40–49 |

2,005 (63.8) 941 (30.0) 195 (6.2) |

| Mother’s education | |

|

No formal education Primary Secondary/higher |

2,520 (80.2) 271 (8.6) 350 (11.2) |

| Residential area | |

|

Urban Rural |

455 (14.5) 2,686 (85.5) |

| Infant sex | |

|

Male Female |

1,623 (51.7) 1,518 (48.3) |

| Number of children born | |

|

One child 2 or more children |

534 (17.0) 2,607 (83.0) |

| *Timely breastfeeding | |

|

No Yes |

1,723 (54.9) 1,418 (45.1) |

| Antenatal care (ANC) utilization | |

|

No Yes |

826 (26.3) 2,315 (73.7) |

| Postnatal care (PNC) for newborn | |

|

No Yes |

2,095 (66.7) 1,046 (33.3) |

| Place of delivery | |

|

Home Health facility/hospital |

1,079 (34.3) 2,062 (65.7) |

| Wealth status | |

|

Lowest quintile Second Middle Fourth Highest quintile |

668 (21.3) 743 (23.7) 746 (23.8) 592 (18.9) 392 (12.5) |

| Access to TV | |

|

No Yes |

3,043 (96.9) 98 (3.1) |

| Access to radio | |

|

No Yes |

2,957 (94.1) 184 (5.9) |

| Access to mobile phones | |

|

No Yes |

2,097 (66.8) 1,044 (33.2) |

*Timely breastfeeding refers to the initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of birth

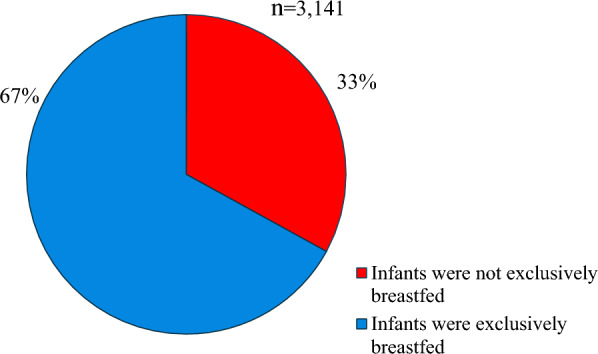

Figure 1 depicts the status of exclusive breastfeeding among infants 0–5 months of age. It shows that out of 3,141 infants, 67% (95%CI: 65%-69%) were exclusively breastfed.

Fig. 1.

Status of exclusive breastfeeding among infants 0–5 months of age

Table 2 shows the likelihood of EBF among 3,141 infants 0–5 months of age. In the multivariable regression analysis, compared with infants for whom breastfeeding was initiated after the first hour of birth, the likelihood of EBF was significantly higher among infants for whom breastfeeding was initiated within the first hour of birth [1.25 (1.07–1.46)]; however, the likelihood of EBF was significantly lower among female infants, compared with male infants [0.83 (0.72–0.97)]. The likelihood of EBF was significantly higher in infants whose mothers had secondary and higher education, compared with infants whose mothers did not have formal education [1.35 (1.04–1.76)] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Likelihood of exclusive breastfeeding among 3,141 infants aged 0–5 months

| Characteristics | **COR (95%CI) | P-value | **AOR (95%CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother’s age (years) | ||||

| 15–29 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 30–39 | 0.96 (0.82–1.13) | 0.65 | 0.98 (0.82–1.17) | 0.80 |

| 40–49 | 0.92 (0.67–1.25) | 0.22 | 0.90 (0.65–1.24) | 0.51 |

| Mother’s education | ||||

| No formal education | Reference | Reference | ||

| Primary | 0.90 (0.69–1.16) | 0.41 | 0.97 (0.74–1.27) | 0.83 |

| Secondary/higher | 1.16 (0.91–1.48) | 0.23 | 1.35 (1.04–1.76) | 0.03 |

| Residential area | ||||

| Urban | Reference | Reference | ||

| Rural | 1.32 (1.08–1.63) | 0.01 | 1.23 (0.97–1.56) | 0.09 |

| Infant sex | ||||

| Male | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 0.83 (0.71–0.96) | 0.01 | 0.83 (0.72–0.97) | 0.02 |

| Number of children born | ||||

| One child | Reference | Reference | ||

| 2 or more children | 1.03 (0.85–1.26) | 0.17 | 1.03 (0.83–1.27) | 0.78 |

| *Timely breastfeeding | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.24 (1.07–1.44) | 0.005 | 1.25 (1.07–1.46) | 0.004 |

| Antenatal care (ANC) utilization | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.82 (0.69–0.97) | 0.02 | 0.87 (0.72–1.05) | 0.15 |

| Postnatal care (PNC) for newborn | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.84 (0.72–0.98) | 0.03 | 0.88 (0.73–1.06) | 0.19 |

| Place of delivery | ||||

| Home | Reference | Reference | ||

| Health facility/ hospital | 0.57 (0.48–0.69) | < 0.001 | 0.98 (0.78–1.24) | 0.87 |

| Wealth status | ||||

| Lowest quintile | Reference | Reference | ||

| Second | 0.96 (0.77–1.21) | 0.74 | 0.98 (0.78–1.24) | 0.88 |

| Middle | 1.02 (0.81–1.28) | 0.87 | 1.07 (0.85–1.36) | 0.55 |

| Fourth | 0.75 (0.59–0.95) | 0.02 | 0.83 (0.64–1.07) | 0.15 |

| Highest quintile | 0.75 (0.58–0.98) | 0.04 | 0.88 (0.64–1.20) | 0.42 |

| Access to TV | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.00 (0.66–1.55) | 0.18 | 1.12 (0.73–1.74) | 0.60 |

| Access to radio | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.88 (0.75–1.04) | 0.11 | 1.03 (0.84–1.26) | 0.77 |

| Access to mobile phones | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.84 (0.72–0.98) | 0.03 | 0.90 (0.76–1.07) | 0.23 |

*Timely breastfeeding refers to the initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of birth

**COR and AOR refer to Crude and adjusted odds ratios, respectively

Significant values are in bold

Discussion

The prevalence of EBF practices among Afghan infants aged 0–5 months was 67.0%. In the adjusted regression model, higher maternal education, timely breastfeeding initiation, and being a male infant were associated with higher odds of EBF practices. Therefore, policy efforts and interventions may consider these factors to enhance EBF practices and improve child morbidity and mortality in Afghanistan.

The prevalence of EBF practices in the current study was 67%, which is higher than the 57.5% reported among infants aged 0–5 months in the Afghanistan Health Survey (AHS) 2018 [38], indicating a 9.5% increase in EBF practices over the past five years. The prevalence of EBF practice in this study was also higher than the EBF rates reported from other low and middle-income countries (LMICs), including 59.3% in Ethiopia [39], 51.6% in Indonesia [40], and 50.8% in Sri Lanka [34]. In contrast, our EBF rate was comparable to the findings obtained from studies in Bangladesh (64.9%) [30] and Uganda (62.3%) [41]. The high prevalence of EBF in Afghanistan may be attributed to religious beliefs and cultural norms that favor breastfeeding [24]. The recent humanitarian crises and the reduction in financial aid post-2021 have placed significant economic strains on families, forcing many to turn to exclusive breastfeeding as it is often seen as the most accessible and affordable option [42]. However, it is important to note that while breastfeeding does not involve direct expenses such as purchasing formula, it is not entirely cost-free [43]. Sustaining exclusive breastfeeding requires adequate nutrition, hydration, and access to healthcare for lactating individuals—resources that may be scarce in crisis settings [43, 44]. Limited access to formula and other feeding alternatives in many areas may also contribute to the higher EBF rates [45]. According to the Global Breastfeeding Scorecard 2023, Afghanistan had the highest increase (> 10%) in EBF practices between 2017 and 2023 [10]. These observations suggest that Afghanistan is among the countries with better EBF rates and is on track to meet the global target of 70% EBF by the year 2030 [10]. However, further emphasis on specific factors identified in the study might be important and deserve attention in future policies and interventions.

Previous studies from developing countries have demonstrated that educated mothers are more likely to adhere to infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices [33, 46]. Similarly, we found that mothers with secondary or higher education had 1.38 times greater odds of exclusively breastfeeding their infants. These findings likely reflect a better knowledge of breastfeeding practice by educated women [31, 33]. Moreover, a similar finding for Afghan women has been previously reported [25], and it highlights the need to enhance women’s higher education opportunities in the country. However, the recent bans imposed on women’s higher education are problematic and may have dire consequences for maternal and child health outcomes in the years ahead. Therefore, this study advocates for women’s secondary and higher education in the country. Additionally, previous studies have provided evidence for the positive impact of educational and supportive interventions on breastfeeding practice among less-educated women in LMICs [33, 47, 48], which cannot be overlooked in this population.

We observed that female infants were less likely to have been exclusively breastfed than male infants [AOR = 0.83, 95%CI 0.72–0.97]. Previous studies were inconsistent in the association between the sex of the infants and EBF practices. For example, a study from Bangladesh reported a lower EBF prevalence in male infants [30]. However, studies from Ethiopia [49], India [50], Cote d’Ivoire [32], and Somaliland [41] have reported lower EBF rates in female infants, which aligns with our findings. Sociocultural differences and context-specific factors may account for the observed difference in the association between the sex of the infant and EBF practices [30, 49, 51]. In Afghan society, male children are often preferred, leading to an unequal distribution of resources and attention for female children [52]. This preference is deeply rooted in sociocultural norms where male dominance as the head of the family and expectations of old age support from sons contribute to a higher emphasis on breastfeeding for boys [53]. Our study strengthens the evidence available regarding gender discrimination in child-feeding practices in Afghanistan. Therefore, promoting gender sensitization in child-feeding practices is urgently needed, in line with Goal 5 of the SDGs, which aims to eliminate all forms of discrimination against women and girls.

Infants who were timely breastfed were more likely to be exclusively breastfed compared to those who were not timely breastfed [AOR = 1.22, 95%CI 1.05–1.42]. This finding is in agreement with studies conducted in Nepal [54], Indonesia [55], and Bangladesh [30]. Initiating breastfeeding immediately within the first hour following birth has positive effects on the mother’s and newborn’s health and well-being [17, 56]. Timely initiation of breastfeeding is an important indicator for improving breastfeeding outcomes [57]. However, in Afghanistan, cultural and religious practices often delay early breastfeeding initiation. Prelacteal feeds such as butter oil, sweet water, and boiled herbs are commonly given to newborns before breastfeeding begins. These rituals, although spiritually meaningful, can delay the initiation of breastfeeding, as the newborn is first given these religious items instead of being put to the breast immediately. A systematic review of breastfeeding practices in South Asia highlighted how religious and cultural norms, including the administration of pre-lacteal feeds, significantly delay the initiation of breastfeeding, leading to suboptimal breastfeeding outcomes [56]. Additionally, some believe that colostrum, the first milk produced by the mother, is ‘dirty’ or harmful and should be expressed and discarded before breastfeeding can begin. This misconception, deeply rooted in cultural practices, is not unique to Afghanistan; it has also been documented in other countries across South Asia, including India, where similar beliefs lead to the delayed initiation of breastfeeding [58]. These practices are deeply ingrained and, while less documented, have a profound impact on delaying breastfeeding initiation. Given these challenges, there is a pressing need to incorporate culturally sensitive education and interventions aimed at promoting early breastfeeding initiation. Addressing these cultural barriers is essential to improving exclusive breastfeeding rates and achieving better health outcomes for mothers and children in Afghanistan.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, data in MICS relied on self-reported information, which may be subject to reporting bias. Second, the EBF prevalence was estimated based on the 24-h recall method, which might have overestimated the prevalence of EBF in this study [29, 59, 60]. However, this method is the most common and currently recommended for the global monitoring of EBF practices [29]. Third, the data in MICS restricted our evaluation of different variables associated with EBF practices. Therefore, further studies should consider a broad range of variables, such as prenatal and postnatal counseling on breastfeeding, traditional and cultural practices and beliefs regarding breastfeeding practices, maternal knowledge of breastfeeding indicators, and family support in their analyses. Finally, the temporal relationship between EBF practices and associated factors is difficult to establish due to the cross-sectional design of the study.

Conclusion

The study revealed that approximately more than two-thirds (67%) of infants aged 0–5 months were exclusively breastfed. The associations with maternal education level, timing of breastfeeding initiation, and the sex of the infant that we identified in our study highlight the importance of considering these factors in policy efforts and interventions targeted at further improving EBF practices in Afghanistan.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank the UNICEF for allowing us to access and analyze this data.

Abbreviations

- AHS

Afghanistan health survey

- ANC

Antenatal care

- AOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- COR

Crude odds ratio

- EBF

Exclusive breastfeeding

- IYCF

Infant and young child feeding

- LMICs

Low and middle-income countries

- MICS

Multiple indicator cluster survey

- ORS

Oral rehydration salts

- PNC

Postnatal care

- SDGs

Sustainable developmental goals

- UNICEF

United Nations international children’s emergency fund

- WHO

World health organizations

Author contributions

Conceptualization and design: MHS and ET. Analysis: MHS and ET. Writing—original draft: MHS, MJ, and ET. Writing—review and editing: MHS, ET, MJ, ZT, SAA, ZE, AWW, HS, and OD. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The MICS 2022–23 dataset is publicly available on UNICEF’s official website through the following link: https://mics.unicef.org/surveys.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was reviewed by the Research and Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Kandahar University, Afghanistan. The committee waived the ethical approval because secondary data from the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) 2022–2023 were used and analyzed in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Amat Camacho N, von Schreeb J, Della Corte F, Kolokotroni O. Interventions to support the re-establishment of breastfeeding and their application in humanitarian settings: a systematic review. Matern Child Nutr. 2023;19(1): e13440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sankar MJ, Sinha B, Chowdhury R, Bhandari N, Taneja S, Martines J, Bahl R. Optimal breastfeeding practices and infant and child mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(467):3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization: Infant and young child feeding; 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infant-and-young-child-feeding (Accessed June 2024).

- 4.UNICEF: Infant Feeding Area Graphs Interpretation Guide for Infant and Young Child Feeding at 0 5 Months. In. New York, NY 10017, USA; 2022. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/resources/infant-feeding-data-dashboard/ (Accessed June 2024).

- 5.Dall’Oglio I, Marchetti F, Mascolo R, Amadio P, Gawronski O, Clemente M, Dotta A, Ferro F, Garofalo A, Salvatori G, et al. Breastfeeding protection, promotion, and support in humanitarian emergencies: a systematic review of literature. J Hum Lact. 2020;36(4):687–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orr SK, Dachner N, Frank L, Tarasuk V. Relation between household food insecurity and breastfeeding in Canada. CMAJ. 2018;190(11):E312–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eamer GG, Randall GE. Barriers to implementing WHO’s exclusive breastfeeding policy for women living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: an exploration of ideas, interests and institutions. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2013;28(3):257–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van den Heuvel M, Birken C. Food insecurity and breastfeeding. CMAJ. 2018;190(11):E310–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization: Children: improving survival and well-being; 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/children-reducing-mortality (Accessed June 2024).

- 10.UNICEF: Global breastfeeding scorecard; 2023. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/documents/global-breastfeeding-scorecard-2023 (Accessed June 2024).

- 11.Tao NPH, Nguyen D, Sediqi SM, Tran L, Huy NT. Healthcare collapse in Afghanistan due to political crises, natural catastrophes, and dearth of international aid post-COVID. J Glob Health. 2023;13:03003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanikzai MH. Need for rapid scaling-up of medical education in Afghanistan: challenges and recommendations. Indian J Med Ethics. 2023;Viii(4):342–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamberti-Castronuovo A, Valente M, Bocchini F, Trentin M, Paschetto M, Bahdori GA, Khadem JA, Nadeem MS, Patmal MH, Alizai MT, et al. Exploring barriers to access to care following the 2021 socio-political changes in Afghanistan: a qualitative study. Confl Heal. 2024;18(1):36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dadras O, Stanikzai MH, Jafari M, Tawfiq E. Early childhood development and its associated factors among children aged 36–59 months in Afghanistan: evidence from the national survey 2022–2023. BMC Pediatr. 2024;24(1):734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.UNICEF: countdown to 2030 country Profile: Afghanistan 2024. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/countdown-2030/country/Afghanistan/1/ (Accessed June 2024).

- 16.Essar MY, Siddiqui A, Head MG. Infectious diseases in Afghanistan: strategies for health system improvement. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6(12): e1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hossain S, Mihrshahi S. Effect of exclusive breastfeeding and other infant and young child feeding practices on childhood morbidity outcomes: associations for infants 0–6 months in 5 South Asian countries using demographic and health survey data. Int Breastfeed J. 2024;19(1):35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dadras O, Suwanbamrung C, Jafari M, Stanikzai MH. Prevalence of stunting and its correlates among children under 5 in Afghanistan: the potential impact of basic and full vaccination. BMC Pediatr. 2024;24(1):436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, Franca GV, Horton S, Krasevec J, Murch S, Sankar MJ, Walker N, Rollins NC, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forde IA, Tripathi V. Determinants of neonatal, post-neonatal and child mortality in Afghanistan using frailty models. Pediatr Res. 2022;91(4):991–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Awoke S, Mulatu B. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding practice among mothers in Sheka Zone, Southwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Public Health Pract (Oxf). 2021;2: 100108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sand A, Kumar R, Shaikh BT, Somrongthong R, Hafeez A, Rai D. Determinants of severe acute malnutrition among children under five years in a rural remote setting: a hospital based study from district Tharparkar-Sindh. Pakistan Pak J Med Sci. 2018;34(2):260–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rollins NC, Bhandari N, Hajeebhoy N, Horton S, Lutter CK, Martines JC, Piwoz EG, Richter LM, Victora CG. Lancet breastfeeding series G: why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet. 2016;387(10017):491–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rahmani FA, Hamdam P, Sadaat I, Mirzazadeh A, Oliolo J, Naqvi N. A major gap between the knowledge and practice of mothers towards early initiation and exclusive breastfeeding in Afghanistan in 2021. Matern Child Health J. 2024;28:1641–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahimi BA, Mohammadi E, Stanikzai MH, Wasiq AW. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding practices in Kandahar, Afghanistan: a cross-sectional analytical study. Int J Pediatr. 2020;8(4):11125–40. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanikzai MH, Wafa MH, Rahimi BA, Sayam H. Conducting health research in the current afghan society: challenges, opportunities, and recommendations. Risk Manag Healthcare Policy. 2023;16:2479–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Afghanistan Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS), 2022–2023. Available at https://www.unicef.org/afghanistan/reports/afghanistan-multiple-indicator-cluster-survey-mics-2022-2023 (Accessed June 2024).

- 28.World Health Organization. Exclusive breastfeeding for optimal growth, development and health of infants; 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/tools/elena/interventions/exclusive-breastfeeding (Accessed June 2024).

- 29.Alayón S, Varela V, Mukuria-Ashe A, Alvey J, Milner E, Pedersen S, Yourkavitch J. Exclusive breastfeeding: measurement to match the global recommendation. Matern Child Nutr. 2022;18(4): e13409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmmed F, Hossain MJ, Sutopa TS, Al-Mamun M, Alam M, Islam MR, Sharma R, Sarker MMR, Azlina MFN. The trend in exclusive breastfeeding practice and its association with maternal employment in Bangladesh: a multilevel analysis. Front Public Health. 2022;10: 988016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jama A, Gebreyesus H, Wubayehu T, Gebregyorgis T, Teweldemedhin M, Berhe T, Berhe N. Exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life and its associated factors among children age 6–24 months in Burao district, Somaliland. Int Breastfeed J. 2020;15(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koffi I, Essis EML, Bamba I, Assi KR, Konan LL, Aka J. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding of children under six months of age in Cote d’Ivoire. Int Breastfeed J. 2023;18(1):43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laksono AD, Wulandari RD, Ibad M, Kusrini I. The effects of mother’s education on achieving exclusive breastfeeding in Indonesia. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ratnayake HE, Rowel D. Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding and barriers for its continuation up to six months in Kandy district, Sri Lanka. Int Breastfeed J. 2018;13(1):36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohammed S, Yakubu I, Fuseini A-G, Abdulai A-M, Yakubu YH. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence and determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months of life in Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dhawan D, Pinnamaneni R, Viswanath K. Association between mass media exposure and infant and young child feeding practices in India: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):19353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manyeh AK, Amu A, Akpakli DE, Williams JE, Gyapong M. Estimating the rate and determinants of exclusive breastfeeding practices among rural mothers in Southern Ghana. Int Breastfeed J. 2020;15(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Afghanistan Health Survey 2018 (AHS2108). Available from: https://www.kit.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/AHS-2018-report-FINAL-15-4-2019.pdf (Accessed June 2024).

- 39.Alebel A, Tesma C, Temesgen B, Ferede A, Kibret GD. Exclusive breastfeeding practice in Ethiopia and its association with antenatal care and institutional delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Breastfeed J. 2018;13(1):31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Idris H, Astari DW. The practice of exclusive breastfeeding by region in Indonesia. Public Health. 2023;217:181–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kimuli D, Nakaggwa F, Namuwenge N, Nsubuga RN, Isabirye P, Kasule K, Katwesige JF, Nyakwezi S, Sevume S, Mubiru N, et al. Sociodemographic and health-related factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding in 77 districts of Uganda. Int Breastfeed J. 2023;18(1):66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valente M, Lamberti-Castronuovo A, Bocchini F, Shafiq Y, Trentin M, Paschetto M, Bahdori GA, Khadem JA, Nadeem MS, Patmal MH, et al. Access to care in Afghanistan after august 2021: a cross-sectional study exploring Afghans’ perspectives in 10 provinces. Confl Heal. 2024;18(1):34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mowl ZK, LeFevre A, Ververs M. A comparison of total cost estimates between exclusive breast-feeding and breast milk substitute usage in humanitarian contexts. Public Health Nutr. 2023;26(12):3162–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santacruz-Salas E, Aranda-Reneo I, Hidalgo-Vega Á, Blanco-Rodriguez JM, Segura-Fragoso A. The Economic influence of breastfeeding on the health cost of newborns. J Hum Lact. 2019;35(2):340–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rahmat ZS, Rafi HM, Nadeem A, Salman Y, Nawaz FA, Essar MY. Child malnutrition in Afghanistan amid a deepening humanitarian crisis. Int Health. 2023;15(4):353–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neves PAR, Barros AJD, Gatica-Domínguez G, Vaz JS, Baker P, Lutter CK. Maternal education and equity in breastfeeding: trends and patterns in 81 low- and middle-income countries between 2000 and 2019. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20(1):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wong MS, Mou H, Chien WT. Effectiveness of educational and supportive intervention for primiparous women on breastfeeding related outcomes and breastfeeding self-efficacy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;117: 103874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haaland K, Sitaraman S. Increased breastfeeding; an educational exchange program between India and Norway improving newborn health in a low- and middle-income hospital population. J Health Popul Nutr. 2022;41(1):16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Habtewold TD, Sharew NT, Alemu SM. Evidence on the effect of gender of newborn, antenatal care and postnatal care on breastfeeding practices in Ethiopia: a meta-analysis andmeta-regression analysis of observational studies. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5): e023956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dutta S, Mishra SK, Mehta AK. Gender discrimination in infant and young child feeding practices in India: evidence from NFHS-4. Indian J Human Dev. 2022;16(2):286–304. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li H, Kim Y, Park C, Kang M, Kang Y. Gender-common and gender-specific determinants of child dietary diversity in eight Asia Pacific countries. J Glob Health. 2022;12:04058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Becvar K, Carpenter C, Leidner B, Young KL. The first daughter effect: Human rights advocacy and attitudes toward gender equality in Taliban-controlled Afghanistan. PLoS ONE. 2024;19(7): e0298812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Das Gupta M, Zhenghua J, Bohua L, Zhenming X, Chung W, Hwa-Ok B. Why is son preference so persistent in East and South Asia? A cross-country study of China, India and the Republic of Korea. J Dev Stud. 2003;40(2):153–87. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Neupane S, Dahal T, Khadgi K. Factors associated with timely initiation of breast feeding among mothers attending maternal and child health clinic at government institutions of Biratnagar. J Biratnagar Nurs Campus. 2023;1(1):69–77. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paramashanti BA, Hadi H, Gunawan IM. Timely initiation of breastfeeding is associated with the practice of exclusive breastfeeding in Indonesia. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2016;25(Suppl 1):S52-s56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sharma IK, Byrne A. Early initiation of breastfeeding: a systematic literature review of factors and barriers in South Asia. Int Breastfeed J. 2016;11(1):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yapo YV. Breastfeeding and child survival from 0 to 5 years in Côte d’Ivoire. J Health Popul Nutr. 2020;39(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.International lactation consultant association: A Closer Look at Cultural Issues Surrounding Breastfeeding; 2012. Available from: https://lactationmatters.org/2012/10/30/a-closer-look-at-cultural-issues-surrounding-breastfeeding/ (Accessed June 2024).

- 59.Singh BK, Khatri RB, Sahani SK, Khanal V. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding among infants under six months in Nepal: multilevel analysis of nationally representative household survey data. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):2456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Khanal V, Lee AH, Scott JA, Karkee R, Binns CW. Implications of methodological differences in measuring the rates of exclusive breastfeeding in Nepal: findings from literature review and cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The MICS 2022–23 dataset is publicly available on UNICEF’s official website through the following link: https://mics.unicef.org/surveys.