Abstract

Background

Oral bacteria can be pathogenic and may change during hospitalization, potentially increasing risk for complications for older adults, including residents of skilled nursing facilities (SNFs).

Objectives

To compare the oral microbiome at hospital admission by prehospital residence (SNF vs home) in older adults not receiving mechanical ventilation and to assess changes in their oral microbiome during hospitalization.

Methods

This prospective, observational study included 46 hospitalized adults (≥65 years old) not receiving mechanical ventilation, enrolled within 72 hours of hospitalization (15 admitted from SNF, 31 from home). Oral health was assessed with the Oral Health Assessment Tool at baseline and days 3, 5, and 7. Genomic DNA was extracted from unstimulated oral saliva specimens for microbiome profiling using 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing. Taxonomic composition, relative abundance, α-diversity (Shannon Index), and β-diversity (Bray-Curtis dissimilarity) of bacterial communities were determined.

Results

Most patients were female (70%) and White (74%) or Hispanic (11%). Mean age was 78.7 years. More patients admitted from SNFs than from home had cognitive impairment (P < .001), delirium (P = .01), frailty (P < .001), and comorbidities (P = .04). Patients from SNFs had more oral bacteria associated with oral disease, lower α-diversity (P < .001), and higher β-diversity (P = .01). In the 28 study completers, α-diversity altered over time (P < .001). A significant interaction was found between groups after adjusting for covariates (P < .001).

Conclusions

Hospitalized older adults admitted from SNFs experience oral microbial and oral health disparities.

Poor oral health may affect clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients. For example, hospital-acquired pneumonia is associated with several bacteria that colonize the oral cavity: Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and methicillin-resistant S aureus.1 Implementation of oral care protocols has reduced pneumonia rates in hospitalized patients not receiving mechanical ventilation,2–5 demonstrating the importance of oral health and oral care practices.

Older adults often have 1 or more oral diseases6–8 such as dental caries, periodontal disease, edentulism, and oral cancer.6 Additionally, the presence of dental devices (eg, dentures, implants, bridges, and crowns) increases the risk for biofilm buildup, bacterial accumulation, and pneumonia.9,10 Oral diseases are associated with inadequate oral health and decreased quality of life.6

Researchers emphasize the need to study determinants of oral health (eg, oral care, esthetics, ability to chew, and oral cavity structure) in relation to the quality of aging in older adults.11 Oral health has been associated with pneumonia in hospitalized patients,12 indicating a need for further study. Hospitalized older adults (≥60 years old) are at higher risk for development of pneumonia, with reported rates as high as 30.4%.13 Those admitted from skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) are at even higher risk because of debilitation and dependency on others to address self-care needs.14,15

Study of the oral microbiome provides in-depth identification of microbes in the oral cavity.16 Oral microbial changes occur as part of healthy aging.17 Frail older adults have a high prevalence of oral colonization with respiratory pathogens, increasing the infection risk.18 Factors such as oral health, number of teeth, dental devices, and comorbidities also affect the oral microbiome in older adults.10,11,19 Studying the oral microbiome in older hospitalized patients is of high importance to identify potential nursing interventions to improve oral health. In this study, we assessed the oral microbiome at hospital admission according to prehospital residence (SNF vs home) in older adults not receiving mechanical ventilation and assessed changes in oral microbiome during hospitalization.

Methods

Design and Setting

This prospective, observational study was conducted from May 2021 to August 2022. The study was approved by the university and study site institutional review boards. Patients were recruited from 1 of 3 progressive care units (intermediate or step-down units) at a large academic medical center in Florida.

Sample

Inclusion criteria were age 65 years or greater, progressive care unit admission, no mechanical ventilation requirement, negative SARS-CoV-2 screening test result, and enrollment within 72 hours of admission from SNF or home. Exclusion criteria were pneumonia diagnosis within 48 hours of hospitalization (community-acquired pneumonia), mechanical ventilation, hospice care, and immunosuppression (receipt of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunosuppressive medications, or ≥10 mg prednisolone per day) within the past 3 months.20–23 A sample size of 58 patients (29 admitted from SNFs and 29 from home) was planned to achieve 80% power, an effect size of 0.185 (preliminary data),24 and a significance level of .05 for baseline and longitudinal comparisons (Stata Statistical Software: Release 18, StataCorp LLC and R Project for Statistical Computing from the R Foundation).25

Procedures

Patient screening, recruitment, and data collection were completed using a standardized protocol. The electronic medical record was used to screen patients for eligibility. Patients could provide consent for themselves if they had screening results negative for cognitive impairment on the Mini-Mental State Examination (score ≥ 25) and negative for delirium on the Confusion Assessment Method tool.26–28 If a patient was unable to provide consent, the patient’s legally authorized representative provided consent.

Following receipt of informed consent, we collected data at baseline (within 72 hours of admission) and on hospital days 3, 5, and 7 (or day 6 if discharged earlier). Demographic and baseline data were obtained from the electronic medical record, the patient, the legally authorized representative, or nursing staff. Longitudinal data were collected until the patient met a study end point: new exclusion criteria, hospital day 7, hospital discharge/transfer, or death.

The Oral Health Assessment Tool was used to measure oral health status. Eight oral health categories (lips, tongue, gums, saliva, natural teeth, dentures, oral cleanliness, and tooth pain) were assessed on a scale of 0 (healthy) to 2 (unhealthy). Scores range from 0 to 16, with higher scores indicating worse oral health.29 After oral assessment, an oral saliva specimen was obtained at each time point (up to 4 specimens per patient). Each patient spit approximately 1 mL of unstimulated saliva into a standardized collection kit containing a DNA and RNA stabilization solution (DNA/RNA Shield, Zymo Research Corporation).30,31 Patients did not drink, eat, or complete oral hygiene for at least 30 minutes before specimen collection.30 We chose to collect unstimulated saliva specimens to mitigate potential challenges with cognition and dentition in older adults. Specimens were stored at room temperature, then frozen at −80 °C until analysis.

Patient and related specimen data were assigned a unique identification code. All data were stored on a password-protected computer in a locked university office. Data were managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tools hosted at the University of Central Florida.32,33

Outcome Measures

Prehospital residence was obtained from the electronic medical record. Oral bacterial taxonomy, α-diversity (Shannon Index),34,35 and β-diversity (Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index)34,36 were compared at baseline according to prehospital residence (SNF vs home). Oral bacterial taxonomy and α-diversity (Shannon Index) were assessed during hospitalization.

DNA Extraction, Library Preparation, and Sequencing

Oral saliva specimens were processed and analyzed using 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing with a metagenomic sequencing system (ZymoBIOMICS, Zymo Research Corporation). The DNA samples were prepared for sequencing with a library preparation kit (Quick-16S primer set V3-V4 next-generation sequencing library prep kit, Zymo Research Corporation). The sequencing library was prepared using a process in which polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were performed in real-time PCR machines to control cycles and therefore limit PCR chimera formation. The final PCR products were quantified with quantitative PCR fluorescence readings and pooled together on the basis of equal molarity. The final pooled library was cleaned with a size selection kit (Select-a-Size DNA Clean & Concentrator, Zymo Research Corporation) and then quantified with nucleic acid analysis systems (TapeStation, Agilent Technologies Inc; Qubit, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc).

A microbial composition profiling product (Zymo-BIOMICS Microbial Community Standard, Zymo Research Corporation) was used as a positive control for each DNA extraction and each targeted library preparation. Negative controls (eg, blank extraction control and blank library preparation control) were included to assess the level of bioburden carried by the wet-laboratory process. Sequencing of the final library was performed with a sequencing system (MiSeq with v3 reagent kit [600 cycles] and 10% PhiX spike-in, Illumina Inc).

Bioinformatics Analysis

The DADA2 pipeline was used to infer unique amplicon sequences from raw reads and remove chimeric sequences.37 A range of 18 830 to 46 212 chimera-free sequences from the oral specimens underwent further amplicon size filtration and were included in the final data analyzed with QIIME version 1.9.1. Taxonomy assignment was performed using Uclust from QIIME version 1.9.1 with the Zymo Research Corporation database. Composition visualization, Shannon Index, and Bray-Curtis dissimilarity analyses were completed with QIIME version 1.9.1.38 Taxonomy with significant relative abundance among different groups was identified by linear discriminant analysis effect size using default settings.39

Statistical Analysis

Data analyses were completed with R programming language and SPSS version 26.0 (IBM). Demographic data were summarized with descriptive statistics. Categorical demographic and longitudinal variables were compared between groups by using χ2 tests. Normally distributed, continuous demographic and longitudinal variables were compared between groups by using t tests. The Mann-Whitney test was used to compare nonnormally distributed data between groups.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize oral bacterial community structures (genus level) between groups at baseline and during hospitalization using relative abundance percentages. The Mann-Whitney test was used to compare the percentages for oral bacterial genera relative abundance between groups at baseline. The Friedman test was used to compare the percentages for oral bacterial genera relative abundance over time and over time by group.

Shannon Index results were compared between groups at baseline using permutational multivariate analysis of variance. Repeated-measures mixed effects modeling was used to compare Shannon Index during hospitalization, with 5 predictors as confounders. Group differences in baseline mean Bray-Curtis dissimilarity values were compared using analysis of similarities, and differences in variance were compared using a multivariate dispersion with permutation test.

Results

Forty-nine patients were recruited, and 47 consented to participate. One patient was unable to provide a saliva specimen and was excluded. Of 46 patients (15 admitted from SNFs and 31 admitted from home), 45 were enrolled within 48 hours of hospitalization. Twenty-eight patients (8 from SNFs and 20 from home) were included in the longitudinal analysis as study completers.

Demographics

Table 1 depicts demographic and clinical information. Most patients were female (70%), were White (74%), and had cardiac diagnoses (96%); patients’ mean (SD) age was 78.7 (9.1) years. Twenty-six percent of patients were of races other than White, and 11% were Hispanic. Patients had a mean Charlson Comorbidity Index of 6.8, indicating a high mortality risk. About half of the patients had a history of smoking (54%) and a dental device (48%), although few were current smokers (7%). Patients in the SNF group had a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index compared with patients admitted from home (7.7 vs 6.3, respectively; P = .04). More patients in the SNF group had cognitive impairment (P < .001), delirium (P = .004), and frailty (P = .03). Table 2 shows longitudinal data. Patients from a SNF had worse oral health status (measured using the Oral Health Assessment Tool) compared with patients admitted from home, and oral health worsened during the hospitalization. Likewise, patients from a SNF had oral care completed less often than patients from home. Over the 4 time points, oral care was completed a mean of 0.3 times per day for SNF patients compared with once daily for patients admitted from home.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study cohort

| Characteristic | Total (N=46) | Skilled nursing facility (n = 15) | Home (n = 31) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 78.7 (9.1) | 81.4 (8.9) | 773 (9.1) | .16a |

|

| ||||

| Sex, No. (%) | .08b | |||

| Female | 32 (70) | 13 (87) | 19 (61) | |

| Male | 14 (30) | 2 (13) | 12 (39) | |

|

| ||||

| Race, No. (%) | .49b | |||

| White | 34 (74) | 11 (73) | 23 (74) | |

| Black | 6 (13) | 2 (13) | 4 (13) | |

| Other | 5 (11) | 1 (7) | 4 (13) | |

| Asian | 1 (2) | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | |

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity, No. (%) | .10b | |||

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 41 (89) | 15 (100) | 26 (84) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 5 (11) | 0 (0) | 5 (16) | |

|

| ||||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean (SD) | 6.8 (2.2) | 7.7 (1.3) | 6.3 (2.5) | .04a |

|

| ||||

| Cognitive impairment. No. (%) | 11 (24) | 10 (67) | 1 (3) | <.001b |

|

| ||||

| Delirium, No. (%) | 3 (6) | 3 (20) | 0 (0) | .01b |

|

| ||||

| GCS score, mean (SD) | 14.7 (0.6) | 14.1 (0.7) | 15.0 (0) | <.001a |

|

| ||||

| Frailty score. No. (%) | <.001b | |||

| 3 (Well, treated comorbid disease) | 4 (9) | 0 (0) | 4 (13) | |

| 4 (Apparently vulnerable) | 16 (35) | 1 (7) | 15 (48) | |

| 5 (Mildly frail) | 10 (22) | 1 (7) | 9 (29) | |

| 6 (Moderately frail) | 14 (30) | 11 (73) | 3 (10) | |

| 7 (Severely frail) | 2 (4) | 2 (13) | 0 (0) | |

|

| ||||

| Antibiotics, No. (%) | 11 (24) | 7 (47) | 4 (13) | .01b |

|

| ||||

| Smoking history. No. (%) | 25 (54) | 9 (60) | 16 (52) | .59b |

|

| ||||

| Current smoker. No. (%) | 3 (6) | 1 (7) | 2 (6) | .98b |

|

| ||||

| Dental device. No. (%) | 22 (48) | 8 (53) | 14 (45) | .60b |

|

| ||||

| OHAT score, mean (SD) | 6.6 (3.6) | 10.6 (2.6) | 4.6 (2.0) | <.001a |

|

| ||||

| Oral care (frequency/day), mean (SD) | 0.5 (0.8) | 0.1 (0.4) | 0.7 (0.9) | .02a |

|

| ||||

| Readmit within 30 days before study. No. (%) | 6 (13) | 3 (20) | 3 (10) | .33b |

Abbreviations: GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; OHAT, Oral Health Assessment Tool.

From t test.

From χ2 test.

Table 2.

Longitudinal variables of study completers (N = 28)

| Baseline |

Hospital day 3 |

Hospital day 5 |

Hospital day 7 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | SNF (n = 8) | Home (n = 20) | P | SNF (n = 8) | Home (n = 20) | P | SNF (n = 8) | Home (n = 20) | P | SNF (n = 8) | Home (n = 20) | P |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Antibiotics, No. (%) | 5 (62) | 2 (10) | .004a | 4 (50) | 3 (15) | .05a | 2 (25) | 7 (35) | .61a | 1 (12) | 6 (30) | .33b |

|

| ||||||||||||

| OHAT score, mean (SD) | 10.3 (2.6) | 4.6 (2.3) | <.001b | 10.4 (1.8) | 5.0 (2.5) | <.001b | 10.4 (3.0) | 6.2 (2.4) | <.001b | 11.3 (2.8) | 6.2 (2.3) | <.001a |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Oral care (frequency/day), mean (SD) | 0.1 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.9) | .02b | 0.3 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.9) | .02b | 0.6 (0.5) | 0.8 (0.8) | .56b | 0.1 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.9) | .003a |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Shannon Index, mean (SD) | 4.3 (1.1) | 4.6 (1.0) | NA | 4.5 (1.0) | 4.8 (0.9) | NA | 4.0 (1.0) | 4.7 (0.8) | NA | 4.0 (1.1) | 4.9 (0.8) | NA |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; OHAT, Oral Health Assessment Tool; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

From t test.

From χ2 test.

Oral Microbiome at Baseline

In the 46 patients, 107 oral bacterial genera were identified; 96 genera had low relative abundance (relative abundance < 1%, categorized as “Others”). The most common oral bacterial genera were Streptococcus, Rothia, Prevotella, Veillonella, and Actinomyces; these genera accounted for nearly 70% of oral bacterial genera colonization, and their relative abundances did not differ significantly between groups. Percentages of oral bacterial genera differed between groups for some genera with low relative abundance. Oral bacterial genera of low relative abundance (ie, <1%) that were more common in the SNF group included Acinetobacter (P = .004), Bacteroides (P = .04), Burkholderia-Paraburkholderia (P = .04), Desulfovibrio (P = .04), Dialister (P = .04), Finegoldia (P = .04), Mycoplasma (P = .04), Phocaeicola (P = .04), Propionibacterium (P < .001), Pseudoramibacter (P = .02), and Shuttleworthia (P = .02). One bacterial genus, Stomatobaculum, was more common in the home group (P = .02). Percentages were very small for these low-abundance oral bacteria and actual values are not reported.

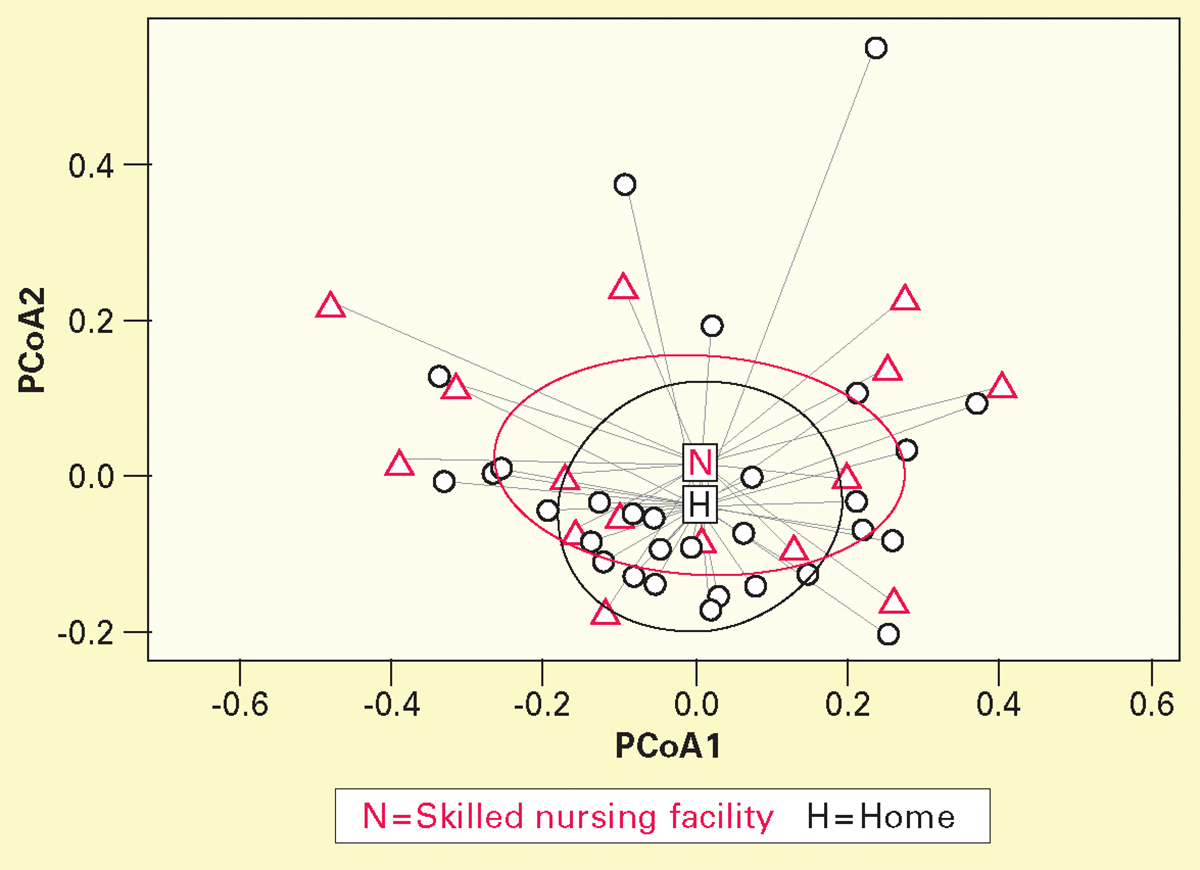

Mean (SD) Shannon Index was lower in the SNF group than in the home group (4.2 [1.2] vs 4.5 [0.9]; P < .001). Bray-Curtis dissimilarity at the genus level differed between groups (mean, P = .01; variance, P = .009) (Figure 1). Mean (SD) Bray-Curtis dissimilarity at the genus level was higher in the SNF group than in the home group (0.60 [0.16] vs 0.47 [0.15]).

Figure 1.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity mean and variance at genus level was higher in skilled nursing facility group (n = 15) than in home group (n = 31) at baseline. For analysis of similarities, P = .01; for multivariate dispersion test, P = .009. Bray-Curtis dissimilarity measures β-diversity (microbial compositional dissimilarity between samples or groups). Values range from 0 to 1; higher values indicate greater dissimilarity.

Longitudinal Changes in Oral Microbiome

In the cohort of 28 study completers, 137 known oral bacterial genera were identified; 125 genera had low relative abundance. Common oral bacterial genera were Streptococcus, Rothia, Prevotella, Veillonella, and Actinomyces. Except for a decline in the percentage of Streptococcus (χ2 = 8.87, P = .03), percentages of other genera remained stable over time. Significant changes in percentages of oral bacterial genera with low relative abundance were not computed over time.

Percentages of common oral bacterial genera declined nonsignificantly over time in the SNF group. Neisseria increased significantly during hospitalization in the home group (χ2 = 13.46, P = .004). Among study completers in the SNF group, oral bacterial genera with low relative abundance (grouped together as “Others”) increased from 20% at baseline to 42% on day 7 (Figure 2A). Among study completers in the home group, oral bacterial genera with low relative abundance increased from 15% at baseline to 23% on day 7 (Figure 2B). The change in low-abundance genera was absolute because several of these genera were not detected at baseline.

Figure 2.

Changes in relative abundance of oral bacterial genera during hospitalization in study completers admitted from (A) skilled nursing facilities (n = 8) and (B) home (n = 20).

Shannon Index changed over time in study completers (P < .001); mean (SD) values during hospitalization were 4.5 (1.0) at baseline, 4.7 (0.9) at day 3, 4.5 (0.9) at day 5, and 4.6 (1.0) at day 7 (values for the 2 groups are shown in Table 2). A significant interaction between the 2 groups was noted over time for Shannon Index values (Figure 3, P < .001). Repeated-measures mixed effects modeling was computed with 5 predictors as confounders. Sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index, cognitive impairment, frailty, and Oral Health Assessment Tool score had no effect on Shannon Index. After adjusting for covariates, a significant time and group by time interaction remained for Shannon Index values.

Figure 3.

Mean Shannon Index values during hospitalization significantly differed for study completers admitted from skilled nursing facilities (n = 8) and home (n = 20). Shannon Index measures α-diversity (taxa diversity within sample or group). Higher values indicate greater taxonomic diversity.

Discussion

Oral Health Vulnerability of Hospitalized Older Adults Admitted From SNFs

At admission, patients admitted from SNFs had higher colonization with low-abundance oral bacteria associated with oral disease40–43 and lower oral microbial diversity than did patients admitted from home. These changes are potentially reflected in the higher mean baseline Oral Health Assessment Tool score in the SNF group (10.6) than in the home group (4.6), indicating worse oral health status. More patients in the SNF group had cognitive impairment, delirium, and frailty, and patients in this group had more comorbidities, which may have contributed to differences in oral health and oral microbiome.44–49 These comorbidities can compromise patients’ ability to self-complete oral care, which was recorded less than once per day. Nearly half of patients in the SNF group admitted to the hospital received antibioics, which can also affect the oral microbiome.50,51

Patients in the SNF group had higher oral microbial dissimilarity than did patients in the home group. Differences may be attributed to environmental causes; patients in the SNF group came from several different facilities. Skilled nursing facility environments vary, reflecting a high turn-over of clients, in contrast to more stable and consistent home settings. Additionally, in SNFs oral care practices vary, staff members may not have training in oral care, and regular oral care is often lacking.52–54 Patients admitted from home generally self-complete daily oral care with a consistent regimen using toothbrushes and toothpaste. Due to the small sample size, we were unable to test any cluster-related differences in oral microbiome on the basis of SNF location.

Older Adults’ Oral Microbial Changes During Hospitalization

Frequently colonized oral bacterial genera in the study completers included Streptococcus, Rothia, Prevotella, Veillonella, and Actinomyces, which are common in the oral cavity.55 Oral microbes have a symbiotic relationship and generally become pathogenic only when commensal microbes can no longer maintain their protective barrier.55 Bacteria in these common genera can also cause disease or infection given the right circumstances.56,57 Increased oral colonization by Neisseria in patients in the home group may have been due to skewed group data; 1 study completer in the home group developed probable nonventilator hospital-acquired pneumonia, and colonization with Neisseria increased on hospital days 5 and 7. Oral bacterial genera with low relative abundance (<1%) nearly doubled during hospitalization in study completers in the SNF group and comprised nearly half of oral colonization by day 7. Although often overlooked, low-abundance organisms may be keystone species that have a disproportionately large impact on the community despite their low relative abundance.58 The clinical implications of such organisms require further study because they may be important markers of and contributors to dysbiosis.58

Although mean Shannon Index differed significantly during the course of hospitalization, absolute values (4.5, 4.7, 4.5, and 4.6) were comparable. The large sample size from longitudinal sampling may have detected small changes due to increased statistical power. Mean Shannon Index differed over time between groups. Longitudinal group differences could have been due to disparities in oral care practices as well as clinical factors such as antibiotics, diet, and hospital environment (private and semiprivate rooms).50,51,59,60

Clinical Implications

Consistent oral care at least twice daily is an important intervention in all hospitalized patients to promote oral health and prevent pneumonia.61–66 Similar to findings of other studies,67,68 daily oral care with a toothbrush and toothpaste (and/or oral chlorhexidine gluconate before procedures) was infrequent, indicating the need for improved oral care within the hospital setting. Patients admitted from home had more frequent oral care (mean of 1.0 times per day) than did patients admitted from SNFs (mean of 0.3 times per day), emphasizing the importance of oral care.

Mean Oral Health Assessment Tool scores increased during hospitalization in both groups, indicating a decline in oral health. Patients in the SNF group had worse oral health status, which is common.69 Differences in Oral Health Assessment Tool scores between groups reflected disparities in oral health and the oral microbiome, strongly suggesting the clinical utility of oral health assessments in the hospital setting. Incorporating standardized oral health assessments into daily care is critical when developing individualized care plans66 and informs clinicians of the need for additional oral interventions for patients whose scores decline. Oral health assessments for older adults should also integrate psychological and social factors such as quality of life.70

Oral care interventions such as structured visits 3 times a week to support oral care and develop a routine, oral self-care tailored to the individual, and self-management training can modify subgingival microbiota and slow cognitive decline.71 Effective and sustainable oral care intervention strategies72 should be further evaluated in hospitalized patients admitted from SNFs because of their high likelihood of cognitive impairment and need for assistance.

Opportunities for Future Research

Studies should be done to further assess the relationships between clinical factors common to SNF patients (eg, cognitive impairment and dental devices) and oral microbiome and oral health. Health conditions associated with oral microbial findings are not limited to pneumonia and should be explored.

Research on strategies to improve oral care in the SNF population continues to evolve.73 Such work may be expanded to identify not only the effects of oral care protocols on clinical outcomes but also the impact of oral care on the oral microbiome. Evaluating the impact of a structured oral health assessment (including psychosocial considerations) and oral care protocols in older adults not receiving mechanical ventilation who require hospitalization remains important and understudied.

Limitations

First, although the target sample size was 58 study completers, we encountered recruitment challenges such as the COVID-19 pandemic and difficulties enrolling SNF patients. Preliminary data showed a larger-than-expected difference between groups despite the small number of patients admitted from SNFs, and the study team agreed to cease data collection after the target sample size for patients admitted from home was achieved. Second, 6 patients were unable to provide saliva samples at various time points due to clinical fluctuations (eg, fatigue, confusion, or inadequate saliva) and instead oral swabs were collected from these patients. Our subanalyses showed similar oral bacterial findings for the 2 specimen collection methods (saliva and swab) in this subset of patients. Third, we used 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing to analyze only bacteria present in oral specimens. Identification of viruses and fungi in future studies may provide a more comprehensive understanding of the oral microbiome. Other factors that may influence the oral microbiome, such as antibiotics and diet, were not included in the analyses. Fourth, our study did not include a dental expert. These limitations may be addressed in the future by increasing the number of SNF patients, carefully considering specimen collection and sequencing methods, and including a dental expert.

Conclusions

At hospital admission, older adults admitted from SNFs had greater oral colonization with bacteria associated with oral disease, lower oral microbial diversity, and higher oral microbial dissimilarity compared with older adults admitted from home. Furthermore, older adults from SNFs had worse oral health and less frequent oral care. Clinical factors common to SNF patients should be explored in relation to the oral microbiome, oral health, and clinical outcomes. The clinical significance and biomarker capability of low-abundance oral organisms should also be studied further.

The oral microbial diversity of hospitalized older adults shifted over time and differed between groups over time. Our findings reinforce the importance of consistent oral care in all hospitalized patients, particularly vulnerable patients such as older adults admitted from SNFs. These patients experience a disparity in oral health and the oral microbiome that must be addressed through consistent oral care, ongoing oral health assessment, and continued study.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research (F31NR019518; principal investigator, Dr Rathbun). Dr Rathbun’s efforts were supported by the National Cancer Institute while she was a postdoctoral fellow at Moffitt Cancer Center (T32 CA090314; multiple principal investigators, Dr Susan Vadaparampil and Dr Vani Simmons). The T32 grant “Behavioral Oncology and Career Development” is a postdoctoral Ruth L. Kirschstein Institutional National Research Service Award.

Contributor Information

Kimberly Paige Rathbun, Moffitt Cancer Center Department of Health Outcomes and Behavior, Tampa, Florida..

Mary Lou Sole, Nursing at University of Central Florida College of Nursing, Orlando..

Shibu Yooseph, Claremont McKenna College, Kravis Department of Integrated Sciences, Claremont, California..

Rui Xie, University of Central Florida College of Nursing and University of Central Florida College of Sciences, Orlando..

Annette M. Bourgault, University of Central Florida College of Nursing..

Steven Talbert, J.W. Ruby Memorial Hospital, West Virginia University, Morgantown..

REFERENCES

- 1.Rathbun KP, Bourgault AM, Sole ML. Oral microbes in hospital-acquired pneumonia: practice and research implications. Crit Care Nurse. 2022;42(3):47–54. doi: 10.4037/ccn2022672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Munro S, Baker D. Reducing missed oral care opportunities to prevent non-ventilator associated hospital acquired pneumonia at the Department of Veterans Affairs. Appl Nurs Res. 2018;44:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2018.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munro S, Haile-Mariam A, Greenwell C, Demirci S, Farooqi O, Vasudeva S. Implementation and dissemination of a Department of Veterans Affairs oral care initiative to prevent hospital-acquired pneumonia among nonventilated patients. Nurs Adm Q. 2018;42(4):363–372. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chick A, Wynne A. Introducing an oral care assessment tool with advanced cleaning products into a high-risk clinical setting. Br J Nurs 2020;29(5):290–296. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2020.29.5.290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolfensberger A, Clack L, von Felten S, et al. Implementation and evaluation of a care bundle for prevention of non-ventilator-associated hospital-acquired pneumonia (nvHAP) - a mixed-methods study protocol for a hybrid type 2 effectiveness-implementation trial. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):603. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05271-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain N, Dutt U, Radenkov I, Jain S. WHO’s global oral health status report 2022: actions, discussion and implementation. Oral Dis. 2024;30(2):73–79. doi: 10.1111/odi.14516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.About periodontal (gum) disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. May 15, 2024. Accessed July 10, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/oral-health/about/gum-periodontal-disease.html [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oral cancer incidence (new cases) by age, race, and gender. National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Updated April 2023. Accessed July 12, 2024. https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/research/data-statistics/oral-cancer/incidence [Google Scholar]

- 9.Camilleri J, Arias Moliz T, Bettencourt A, et al. Standardization of antimicrobial testing of dental devices. Dent Mater. 2020;36(3):e59–e73. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2019.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dakka A, Nazir Z, Shamim H, et al. Ill effects and complications associated to removable dentures with improper use and poor oral hygiene: a systematic review. Cureus. 2022;14(8):e28144. doi: 10.7759/cureus.28144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vendola MCC, Jacob-Filho W. Impact of oral health on frailty syndrome in frail older adults. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 2023;21:eAO0103. doi: 10.31744/einstein_journal/2023AO0103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Son M, Jo S, Lee JS, Lee DH. Association between oral health and incidence of pneumonia: a population-based cohort study from Korea. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):9576. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66312-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao X, Wang L, Wei N, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of healthcare-associated infection in elderly patients in a large Chinese tertiary hospital: a 3-year surveillance study. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):121. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-4840-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robertson T, Carter D. Oral intensity: reducing non-ventilator-associated hospital-acquired pneumonia in care-dependent, neurologically impaired patients. Can J Neurosci Nurs. 2013;35(2):10–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burdsall D Non-ventilator health care-associated pneumonia (NV-HAP): long-term care. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48(5S):A14–A16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lenartova M, Tesinska B, Janatova T, et al. The oral microbiome in periodontal health. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:629723. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.629723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou X, Wang B, Demkowicz PC, et al. Exploratory studies of oral and fecal microbiome in healthy human aging. Front Aging. 2022;3:1002405. doi: 10.3389/fragi.2022.1002405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ortega O, Sakwinska O, Combremont S, et al. High prevalence of colonization of oral cavity by respiratory pathogens in frail older patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(12):1804–1816. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ewan VC, Reid WDK, Shirley M, Simpson AJ, Rushton SP, Wade WG. Oropharyngeal microbiota in frail older patients unaffected by time in hospital. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:42. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quinn B, Baker DL, Cohen S, Stewart JL, Lima CA, Parise C. Basic nursing care to prevent nonventilator hospital-acquired pneumonia. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2014;46(1):11–19. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pássaro L, Harbarth S, Landelle C. Prevention of hospitalacquired pneumonia in non-ventilated adult patients: a narrative review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2016;5:43. doi: 10.1186/s13756-016-0150-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ewan VC, Sails AD, Walls AW, Rushton S, Newton JL. Dental and microbiological risk factors for hospital-acquired pneumonia in non-ventilated older patients. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0123622. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belstrøm D The salivary microbiota in health and disease. J Oral Microbiol. 2020;12(1):1723975. doi: 10.1080/20002297.2020.1723975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sole ML, Yooseph S, Talbert S, et al. Pulmonary microbiome of patients receiving mechanical ventilation: changes over time. Am J Crit Care. 2021;30(2):128–132. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2021194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Statistical power analysis online. WebPower. Updated May 3, 2023. Accessed April 20, 2020. https://webpower.psychstat.org [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsoi KK, Chan JY, Hirai HW, Wong SY, Kwok TC. Cognitive tests to detect dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1450–1458. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schuurmans MJ, Deschamps PI, Markham SW, ShortridgeBaggett LM, Duursma SA. The measurement of delirium: review of scales. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2003;17(3):207–224. doi: 10.1891/rtnp.17.3.207.53186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941–948. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chalmers JM, King PL, Spencer AJ, Wright FA, Carter KD. The oral health assessment tool—validity and reliability. Aust Dent J. 2005;50(3):191–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2005.tb00360.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cabral DJ, Wurster JI, Flokas ME, et al. The salivary microbiome is consistent between subjects and resistant to impacts of short-term hospitalization. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):11040. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11427-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gomar-Vercher S, Simón-Soro A, Montiel-Company JM, Almerich-Silla JM, Mira A. Stimulated and unstimulated saliva samples have significantly different bacterial profiles. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0198021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kers JG, Saccenti E. The power of microbiome studies: some considerations on which alpha and beta metrics to use and how to report results. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:796025. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.796025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagner BD, Grunwald GK, Zerbe GO, et al. On the use of diversity measures in longitudinal sequencing studies of microbial communities. Front Microbiol 2018;9:1037. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qian XB, Chen T, Xu YP, et al. A guide to human microbiome research: study design, sample collection, and bioinformatics analysis. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020;133(15):1844–1855. doi: 10.1097/cm9.0000000000000871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJ, Holmes SP. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016;13(7):581–583. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7(5):335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011;12(6):R60. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dioguardi M, Alovisi M, Crincoli V, et al. Prevalence of the genus Propionibacterium in primary and persistent endodontic lesions: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2020;9(3):739. doi: 10.3390/jcm9030739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manome A, Abiko Y, Kawashima J, Washio J, Fukumoto S, Takahashi N. Acidogenic potential of oral Bifidobacterium and its high fluoride tolerance. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1099. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bao K, Bostanci N, Thurnheer T, Belibasakis GN. Proteomic shifts in multi-species oral biofilms caused by Anaeroglobus geminatus. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):4409. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04594-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawamoto D, Borges R, Ribeiro RA, et al. Oral dysbiosis in severe forms of periodontitis is associated with gut dysbiosis and correlated with salivary inflammatory mediators: a preliminary study. Front Oral Health. 2021;2:722495. doi: 10.3389/froh.2021.722495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Larson PJ, Zhou W, Santiago A, et al. Associations of the skin, oral and gut microbiome with aging, frailty and infection risk reservoirs in older adults. Nat Aging 2022;2(10):941–955. doi: 10.1038/s43587-022-00287-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ogawa T, Hirose Y, Honda-Ogawa M, et al. Composition of salivary microbiota in elderly subjects. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):414. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18677-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Y, Shen Y, Liufu N, et al. Transmission of Alzheimer’s disease-associated microbiota dysbiosis and its impact on cognitive function: evidence from mouse models and human patients. Res Sq. Preprint posted online April 28, 2023. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-2790988/v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weber C, Dilthey A, Finzer P. The role of microbiome-host interactions in the development of Alzheimer s disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13:1151021. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1151021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fogelholm N, Leskelä J, Manzoor M, et al. Subgingival microbiome at different levels of cognition. J Oral Microbiol. 2023;15(1):2178765. doi: 10.1080/20002297.2023.2178765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Da D, Zhao Q, Zhang H, et al. Oral microbiome in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. J Oral Microbiol. 2023;15(1):2173544. doi: 10.1080/20002297.2023.2173544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheng X, He F, Si M, Sun P, Chen Q. Effects of antibiotic use on saliva antibody content and oral microbiota in Sprague Dawley rats. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:721691. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.721691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yuan X, Zhou F, Wang H, et al. Systemic antibiotics increase microbiota pathogenicity and oral bone loss. Int J Oral Sci. 2023;15(1):4. doi: 10.1038/s41368-022-00212-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wagner S, Rosian-Schikuta I, Cabral J. Oral-care adherence. Service design for nursing homes - initial caregiver reactions and socio-economic analysis. Ger Med Sci. 2022;20:Doc04. doi: 10.3205/000306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weening-Verbree LF, Schuller DAA, Cheung SL, Zuidema PDSU, Schans PCDPV, Hobbelen DJSM. Barriers and facilitators of oral health care experienced by nursing home staff. Geriatr Nurs 2021;42(4):799–805. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patterson Norrie T, Villarosa AR, Kong AC, et al. Oral health in residential aged care: perceptions of nurses and management staff. Nurs Open. 2019;7(2):536–546. doi: 10.1002/nop2.418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deo PN, Deshmukh R. Oral microbiome: unveiling the fundamentals. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2019;23(1):122–128. doi: 10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_304_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ramanan P, Barreto JN, Osmon DR, Tosh PK. Rothia bacteremia: a 10-year experience at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(9):3184–3189. doi: 10.1128/jcm.01270-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Könönen E, Gursoy UK. Oral Prevotella species and their connection to events of clinical relevance in gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts. Front Microbiol 2022;12:798763. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.798763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Cena JA, Zhang J, Deng D, Damé-Teixeira N, Do T. Low-abundant microorganisms: the human microbiome’s dark matter, a scoping review. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:689197. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.689197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shaalan A, Lee S, Feart C, et al. Alterations in the oral microbiome associated with diabetes, overweight, and dietary components. Front Nutr 2022;9:914715. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.914715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu T, Chen YC, Jeng SL, et al. Short-term effects of chlorhexidine mouthwash and Listerine on oral microbiome in hospitalized patients. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13: 1056534. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1056534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gibney JM, Naganathan V, Lim MAWT. Oral health is essential to the well-being of older people. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;29(10):1053–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2021.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gibney JM, Wright FA, D’Souza M, Naganathan V. Improving the oral health of older people in hospital. Australas J Ageing 2019;38(1):33–38. doi: 10.1111/ajag.12588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Quinn B Best practices in oral care. Crit Care Nurse. 2023;43(3):64–67. doi: 10.4037/ccn2023507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Giuliano KK, Penoyer D, Middleton A, Baker D. Original research: oral care as prevention for nonventilator hospitalacquired pneumonia: a four-unit cluster randomized study. Am J Nurs. 2021;121(6):24–33. doi: 10.1097/01.Naj.0000753468.99321.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Collins T, Plowright C, Gibson V, et al. British Association of Critical Care Nurses: evidence-based consensus paper for oral care within adult critical care units. Nurs Crit Care 2021;26(4):224–233. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oral health in healthcare settings to prevent pneumonia toolkit. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. March 27, 2024. Accessed July 24, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/healthcare-associated-infections/hcp/prevention-healthcare/oral-health-pneumonia-toolkit.html [Google Scholar]

- 67.Saarela RKT, Hiltunen K, Kautiainen H, Roitto HM, Mäntylä P, Pitkälä KH. Oral hygiene and health-related quality of life in institutionalized older people. Eur Geriatr Med. 2022;13(1):213–220. doi: 10.1007/s41999-021-00547-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Coker E, Ploeg J, Kaasalainen S, Carter N. Nurses’ oral hygiene care practices with hospitalised older adults in postacute settings. Int J Older People Nurs 2017;12(1). doi: 10.1111/opn.12124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zimmerman S, Austin S, Cohen L, et al. Readily identifiable risk factors of nursing home residents’ oral hygiene: dementia, hospice, and length of stay. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(11):2516–2521. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang H, Xiao J, Cui S, Zhang L, Chen L. Oral health assessment tools for elderly adults: a scoping review. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2023;16:4181–4192. doi: 10.2147/jmdh.S442439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen L, Cao H, Wu X, et al. Effects of oral health intervention strategies on cognition and microbiota alterations in patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. Geriatr Nurs 2022;48:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2022.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weintraub JA, Zimmerman S, Ward K, et al. Improving nursing home residents’ oral hygiene: results of a cluster randomized intervention trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;1 9(12):1086–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.09.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Overgaard C, Bøggild H, Hede B, Bagger M, Hartmann LG, Aagaard K. Improving oral health in nursing home residents: a cluster randomized trial of a shared oral care intervention. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2022;50(2):115–123. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]