Abstract

Background

Adult specialist palliative care professionals have played a key role in the care of children with palliative care needs in the community. However, there is little known on their perceived level of preparedness or training in providing children’s palliative care in the community setting. The aim of this scoping review is to appraise the current literature and identify any existing gaps in knowledge on the level of preparedness and training of adult specialist palliative care professionals caring for children in the community. The review question asks: “Do adult specialist palliative care professionals feel sufficiently prepared to deliver their services to children in the community?”.

Methods

In order to address the review question, a scoping review was conducted. This was guided by the framework of Arksey and O’Malley and further enhanced by the methodology of the Joanna Brigg’s Institute in order to report the findings.

Results

Twenty studies were identified from the database searches. Common areas identified from the literature were that adult specialist palliative care professionals perceived that they had a lack of training or experience in children’s palliative care, lack of knowledge or preparedness, and that they faced barriers preventing them from providing effective children’s palliative care.

Conclusion

This review highlights the lack of empirical research on adult specialist palliative care professionals providing children’s palliative care in the community. While the available literature demonstrates both their limited training, experience and preparedness in caring for children.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12904-025-01792-5.

Keywords: Pediatric palliative care, Palliative care, Child, Community, Specialist palliative care

Background

Children’s palliative care (CPC) is a subspecialty in paediatrics that has slowly evolved and expanded globally over the years. Previously, CPC focused primarily on managing symptoms during the final days of life. While today, CPC is defined by the World Health Organisation as:

‘the active total care of the child’s body, mind and spirit, and also involves giving support to the family. It begins when illness is diagnosed, and continues regardless of whether or not a child receives treatment directed at the disease. Health providers must evaluate and alleviate a child’s physical, psychological and social distress. Effective palliative care requires a broad multidisciplinary approach that includes the family and makes use of available community resources; it can be successfully implemented even if resources are limited. It can be provided in tertiary care facilities, in community health centres and even in children's homes’ [1].

CPC has continued to evolve over the years in response to the growing demands for its services. Globally it is estimated that there is 21 million children who need CPC or end of life care [2]. This number is an estimate, as there is no universally accepted method in measuring population-level need for CPC [3] due to challenges in defining the child population in need [4–7] and by the limited available data e.g. number of child deaths caused by a life-limiting condition (LLC) [8–10]. International standards for the classification of conditions that may require CPC has been reported by a group of international experts through the GO-PPaCS project (Global Overview – Paediatric Palliative Care Standards) [8]. According to them, CPC is described as a service that is provided to children and young people with LLCs, life-threatening conditions or terminal illnesses. Children with LLCs or life-threatening conditions can be classified into four disease groups based on their disease trajectory [11]. These disease groups include LLCs for which treatment may fail, conditions where premature death is inevitable, progressive non-curative conditions, and irreversible non-progressive conditions leading to disability and likelihood of premature death [12]. However, these disease groups may expand as current evidence is now recommending to incorporate care complexity factors and a perinatal/neonatal fifth group too [3, 7, 8, 12]. Reflecting the evolving nature of CPC and the likelihood of a significant increase in demand.

The rising need for CPC is primarily due to children living longer due to medical advancements, and the broader eligibility criteria for CPC involvement [8]. For example, recent prevalence data within an English study estimated there were 32 cases per 10,000 in 2009–2010, increasing to 66.4 per 10,000 in 2017–2018, and a projected rise to 84.2 per 10,000 by 2030 [9, 13]. Increases like these highlight the need for effective planning and assessment of CPC services. However, only estimated prevalence numbers have been reported. This is due to there being no national database worldwide showing the prevalence of children with LLCs for practical, ethical and financial reasons [14].

CPC is important as it has the potential to improve symptom control and the quality of life of children and their families [8], reduce the number of hospitalisations and increase the opportunity to die in their desired place of death [15]. CPC can be offered at three levels of ascending specialisation, starting at level one (palliative care approach) in which a palliative approach is provided by all healthcare providers, level two (generalist CPC) where general palliative care is delivered by disease-specific specialists trained in palliative care, and level three (specialist CPC) where specialist CPC is delivered by experts in CPC [8]. There is recognition in Ireland, USA and the United Kingdom that adult specialist palliative care (SPC) professionals play a key role in the care of children with LLCs in the community [16–18]. These professionals have an expertise in caring for adults, usually over the age of 65 [4]. Although not experts in CPC, they can offer important specialist palliative care support that other community health professionals may not be able to provide. There are many possible reasons as to why adult-trained professionals are caring for children and not CPC experts such as the lack of standardised CPC education and varying access to CPC resources depending on place of residence [19–21]. There is growing evidence now that adult SPC professionals may not have sufficient training or knowledge to be caring for children [17, 22–28]. However they are still expected to provide that care. Evidently, there are distinct differences between adult palliative care and CPC [4]. Examples of these differences include: the number of children dying are small compared to adults; the diagnoses children face are often rare, familial or specific to childhood or young adulthood; the importance of play for children; and that professionals need to recognise that children have different levels of communication and understanding of their illness [12]. Children typically require palliative care for a broad range of conditions including congenital anomalies, genetic disorders, neurological conditions, and perinatal complications, often with prolonged trajectories [4]. While adults usually require palliative care for advanced cancers, cardiovascular diseases, and chronic respiratory diseases [29]. However, there are some similarities to adult palliative care and CPC such as the approaches to symptom management and the need for care to acknowledge the whole family [12]. These similarities are few in number and do not adequately prepare adult SPC professionals to care for children in the community without additional training. There is growing recognition now in Europe and the UK that additional education for adult SPC professionals in the community is an important step towards delivering high quality CPC [30, 31]. A framework that sets out standardising CPC education has not yet been established. A report on the international standards for CPC services recommended, as far back as 2008, that all countries should develop specific education curricula for all professionals involved in CPC [32]. In response, a Children’s Palliative Care Education and Training Action Group was formed across the UK and Ireland in 2019 to take this initiative forward in order to standardise CPC training [33]. There are already a number of CPC training programmes set up internationally in Asia, Europe, North America, Oceania, Sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and the UK [26, 34–36]. Progress has been made, but there is a considerable amount of work ahead especially as adult SPC professionals continue to care for children in the community without formal training.

In line with these concerns, we hope that this review has provided insight on the current evidence regarding adult SPC professionals providing their services to children in the community.

Aim of the review

The aim of this scoping review was to evaluate the current literature on the care of children provided by adult SPC professionals in the community, with a focus on identifying knowledge gaps and examining adult SPC professionals’ perceived preparedness, training, experience, knowledge, and confidence in delivering CPC.

Methods

A scoping review was conducted to find and map the available literature as well as to bring to light what future research may be needed [37, 38]. The Arksey and O’Malley methodological framework was used [39] while incorporating the updated guidance provided by the Joanna Briggs Institute [40]. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) standards were adopted to report the relevant findings from the literature search [41].

In addition, a protocol was completed for this scoping review using the PRISMA-P checklist. The draft was revised by an experienced senior academic at University College Dublin [MC] who provided suggestions for review. With the appropriate revisions made and further analysis by the research team, the final protocol was registered to Open Science Framework on the 18th April 2024 [42].

Stage 1 – identifying the research question

The research question was to explore and map the existing body of evidence related to adult SPC professionals caring for children in the community. Key stakeholders with expertise and experience in CPC as well as adult palliative care helped develop the research question by contributing their insights into current priorities and gaps in the field.

Stage 2 – identifying the relevant studies

The inclusion and exclusion criteria was set in order to gather the appropriate literature that would answer the review question. The recommended Population, Concept and Context framework [40, 43] for scoping reviews was used to structure the eligibility criteria as shown in Table 1. Eligible studies must include adult SPC professionals (population). There does not seem to be a specific definition for “adult SPC professionals” in Ireland [16] or the UK [44]. However, for this review adult SPC professionals were defined as healthcare professionals who provide a SPC service that primarily provides care to adults (18 years or older). SPC can be defined as care provided by healthcare professionals (usually involving an interdisciplinary team e.g. doctors, nurses, dietitians etc.) with the appropriate education, training, and clinical experience in palliative care, and whose main role involves delivering such care [45]. Paediatric SPC professionals whose primary patient population are children, were excluded.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria

| PCC | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Adult specialist palliative care professionals (doctors, nurses, physiotherapists etc.) | Paediatric specialist palliative care professionals whose primary patient population are children |

| Concept | Caring for children (0–18 years) | Caring for only adults (> 18 years) |

| Context | Working in the community setting | Working only in an inpatient/outpatient setting |

The place of work had to be in the community setting (context). Studies focused on a hospice or inpatient/outpatient hospital setting only were excluded.

Eligible studies had to mention paediatric patients (concept). For this review, a child is described as anyone under the age of 18 as recognised by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child [46]. Studies that only mentioned adult patients were excluded.

Studies were excluded if they were clinical trials, non-empirical research, or studies not relating to humans or not reported in English.

To identify potentially relevant papers, the following databases were used: PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Scopus, ERIC and Cochrane Library. No limits were applied to the databases. The first search was conducted in November 2023, and rerun in July 2024 to check for any new references. The search strategy was drafted by the researcher MMD with support from a key stakeholder in palliative care [MC]. Then further refined by the Specialist Librarian [FL] at the Education & Research Centre of Our Lady’s Hospice & Care Services who peer-reviewed using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) checklist, and a librarian at University College Dublin. Lastly, the search strategy was finalised by senior academics, experienced in the scoping review process. An example of the final search strategy for PubMed can be found in the online supplemental number 1. The final search results from each database were systematically exported to EndNote. They then were transferred to Covidence where duplicates were automatically removed.

EndNote 20™ bibliographic software (Clarivate Analytics LLP, USA) was used to store the papers retrieved from all the searches. Screening of the records was completed using a web-based literature review software platform called Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Australia).

Stage 3 – study selection

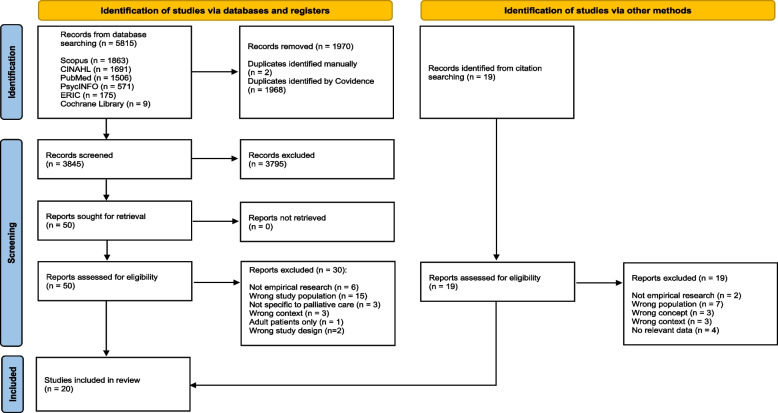

Once duplicates were removed by Covidence, two reviewers (MMD and MC) independently screened title and abstracts, and completed full-text reviews of the eligible studies. Both reviewers agreed to include any papers when there was doubt over its eligibility for further analysis. Disagreements during the independent review process were resolved by discussion and consensus between the two reviewers. A third reviewer was available if consensus was not achieved. The results are reported in the PRISMA flowchart [47] (Fig. 1). The reference list of all retrieved full text papers were hand searched to assess their eligibility for inclusion in the review. Nineteen were identified but no papers met the PCC (Population, Concept, Context) criteria during full text review.

Fig. 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis extension for scoping reviews flow diagram

Stage 4 – charting the data

Once the two reviewers completed full-text review, MMD extracted the relevant information from the final 20 papers using a review-specific template in which MC reviewed iteratively and provided feedback on the data charted. It was then further refined in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute guidelines [40]. The data extraction table as shown in the online supplemental (number 2) shows the data extracted template and analyses. The agreed characteristics of the data charted included the following headings: author(s), year, country, journal, aim(s), response rate, methodology, and key findings. Key findings included the following headings: PC experience (number of years working in palliative care or those identified as working in palliative care), CPC experience (number of children cared for or time providing CPC), previous CPC training, setting (primary practice setting e.g. community, inpatient, hospice or outpatient), perceived preparedness in providing CPC, challenges in CPC provision or training, and professional development needs identified.

Stage 5-collating, summarising and reporting the results

The extracted data underwent two phases of analyses: numerical and then descriptive content analysis that captured the main categories addressing the review question. The diverse nature of the studies meant that they were reviewed individually for emerging themes.

Results

Selection of studies

Five thousand eight hundred fifteen citations were identified from the database search. 1968 citations were automatically removed as duplicates, with a further 2 manually removed during screening. 3845 citations were screened and 50 were included in the full text review (see Fig. 1). The final number of records for data extraction was 20 (found in the online supplemental number 2). The main reasons for exclusion were wrong study population, non-empirical research or wrong context.

Description of studies

Overall, this review yielded a small number of 20 papers that provided a unique perspective into the types of issues that adult SPC professionals can face when caring for children in the community.

The year of publication for the selected papers ranged from 1994 to 2022, but the majority (n = 13) were new publications within the last 5 years. This demonstrates how CPC is a relatively recent focus in the literature. The oldest paper published in 1994 [48] is at least a decade older than the rest of the 19 papers which may highlight a period where the topic was overlooked or no longer prioritised, to then re-emerge notably from the year 2020.

Half of the studies were from the USA, 3 from the UK, 2 from Ireland and finally 1 from each of the following countries Malaysia, India, Australia, South Korea and Canada. Most studies were from the USA or UK, reflecting their early involvement in the global development of CPC. Few European countries were found in the search even though they account for 3 of the 7 countries who provide the most developed CPC services worldwide [49]. This however could be due to only English language citations being included in this review.

The methodological approach was heterogeneous with 12 focusing on quantitative, 7 qualitative, and 1 mixed methods. The preferred methodologies used were surveys or semi-structured interviews with adult SPC professionals. Five studies conducted cross-sectional surveys [22, 24, 48, 50–52], while 7 focused on longitudinal designs (e.g. pre-test and post-test) [25, 26, 53–57] to collect the relevant data. The cross-sectional surveys largely evaluated the present state of CPC, the learning needs of adult SPC professionals, the challenges of providing effective CPC, as well as adult SPC professionals’ comfort levels in providing CPC. While the longitudinal surveys focused on evaluating the impact of CPC training or telemedicine practices on adult SPC professionals.

It was noteworthy that 14 out of the 20 studies selected were published in dedicated palliative care journals. The population sample size of the papers ranged from an approximated 4 to 551 adult SPC professionals. It was challenging to identify the number of adult SPC professionals as many studies did not provide detailed information on the population’s demographics such as their training or experience in palliative care or paediatrics, or their primary patient cohort or clinical setting. For example, the term ‘hospice nurses’ was used in papers, however this term alone does not provide sufficient insight into their role in CPC. Hospice nurses can refer to those who work with adults, children, or both, and in either community or hospice settings. In contrast, one of the papers provided a clear understanding of their sample population. They described their participants as ‘adult community nurses’ and they collected further information on the number of children the participants cared for and whether participants had children’s nursing qualifications [28]. Only 8 out of the 20 studies reported on previous CPC training. Studies that may not fully meet our population criteria but could reasonably be presumed to do so due to a lack of data were still included in the analysis. Eleven studies had nurses as the professionals while the rest had a mix of multidisciplinary members including doctors, occupational therapists, medical social workers etc. This was expected as nurses play a key role in the care of children with LLCs in the community [12].

Following a detailed analysis of the extracted data, 4 broad categories emerged from the literature. These categories examined the training, preparedness, challenges and future directions in relation to adult SPC professionals caring for children in the community.

Training

Variation in training across countries

The level of training and development of palliative care services differed between countries. The majority (n = 18) of the 20 selected studies within this review are located in countries classified at the highest level of palliative care development (USA, Canada, Australia, South Korea, UK and Ireland) [58]. While the studies from Malaysia and India in this review are three levels below in the ‘isolated palliative care provision’ category, they still presented findings that were relevant and comparable to the other countries. An example of a related area of interest for different countries would be on the provision of adequate CPC training to resource-limited or rural communities [25, 56, 57].

Inconsistencies in reporting prior training

The studies differed in the extent to which they reported on the prior CPC training of adult SPC professionals. Many studies focused solely on their previous clinical experience in CPC e.g. number of years’ experience or number of children cared for [22, 50, 59], or just their palliative care clinical experience (not specified whether adult or children’s) [54, 60], or the number of years in their respective profession (not specifically palliative care) [25, 26]. Some studies reported their previous theoretical or academic training in CPC [53] or just palliative care (not specified if training content included CPC) [48]. Interestingly, there were only 2 papers that asked about whether they had previous paediatric training in general [28, 55]. One study from Malaysia detailed that no formal CPC training is available nationally [23]. Three studies did not ask the health professionals about their previous training at all [50, 57, 61]. And only 7 studies considered to report whether these professionals had both theoretical and experience-based training [24, 27, 28, 51, 52, 56, 62].

Limited clinical experience with children

When examining the paediatric clinical experience of adult SPC professionals in more detail, it is evident that adult SPC professionals have little experience working with children in the community. Half of the studies within the review identified this as a particular issue for these providers [22, 23, 25, 28, 50–52, 56, 62]. The studies identified the typical number of paediatric patients these professionals see annually. For example, it was identified that most adult SPC professionals chose the lowest range when it came to selecting the number of children they would or their healthcare organisation would see per year. When given a range of annual paediatric patient numbers, most adult SPC professionals selected less than 5 patients per year (lowest range they could select) [22, 51, 56, 62], or less than 10 patients per year (the lowest range they could select) [25, 55]. While others did not give a range but showed that the majority of professionals would annually care for perhaps 1 child [28] or 3 children [50], with some describing their exposure to paediatric patients as every couple of years or less [52, 56]. The possible reasons provided for the low numbers were that not a lot of children were requiring SPC services in the area [50], or that there was not enough resources or adequately trained staff to take on these patients [22–24]. No papers explored whether the low number of children requiring SPC services might be attributed to parents or carers assuming the role of SPC providers, or that those working in the subspeciality of CPC were taking on the majority of patients. In addition, 2 studies highlighted that SPC professionals preferred adult patients over children, and that this may deter them from taking on paediatric caseloads [27, 51].

From review of the literature, regardless of the national level of palliative care development, adult SPC professionals are not trained in any systematic way in CPC, they rarely care for children in the community and the reasons for this are multifactorial including systemic issues that go beyond training.

Preparedness

While adult SPC professionals acknowledged they lacked exposure to paediatric patients in the community, they also admitted they lacked sufficient levels of education [22–24], knowledge [25–28], preparedness [28, 61], comfort [22, 23, 52, 53, 55, 60, 62] and confidence [23, 28, 55, 59] in providing CPC.

Reported learning needs in CPC

Many studies asked adult SPC professionals to identify areas within CPC where they felt they required additional support in. The most common topics in CPC that they felt they required additional support in were understanding pain [22, 27, 52, 55, 59] or non-pain symptoms [22, 26, 27, 52, 55], medication management (with one Canadian paper noting medical marijuana [26]) [23, 25, 27, 55, 59, 62], and communication skills [22, 23, 25–28, 52, 53, 55, 59, 62]. Others highlighted were understanding complex childhood diagnoses [23, 24, 60, 61], and providing psychosocial support [22, 25–27, 61, 62], or grief/bereavement support [26, 52, 54, 55]. Uniquely to the others, there was one paper emphasising a limited understanding of hydration and nutrition and removal of ventilation practices [55]. Only one paper tested adult SPC professionals’ knowledge [55], while the rest asked for their ‘perceived’ lack in knowledge using Likert scales. Additionally, another paper highlighted that adult SPC professionals felt it was important to explore CPC topics while also comparing the paediatric care to the care they would provide to the adult patient in order to appreciate the key distinctions between each other [27].

Reported rationale for the lack of preparedness

Many studies did not collect enough information to fully examine the reasons why adult SPC professionals were prepared or unprepared in providing CPC, particularly those that presented participants with relatively high levels of preparedness. For example, one paper found that the nurses they surveyed had a good understanding of grief and bereavement in CPC but did not identify the possible reasons why such as prior CPC training or CPC experience [54]. Asking these kind of questions is important as many of the studies would mention that the lack of exposure to paediatric patients was one of the most impactful variables on providers’ confidence or comfort levels [23, 51, 52, 59]. Highlighting the importance of regular clinical exposure to paediatric patients to help clinicians build confidence. One study supported these findings, suggesting that formal CPC training was the most significant variable with respect to comfort with “management of severe symptoms at the end of life” [51] (p.1144). Furthermore, another study found that having a previous children’s qualification was the most important to improve confidence, not the clinical experience or how young the healthcare professional was [28]. However, other studies found that more nursing experience in general was an important factor in confidence levels [53]. This highlights the importance of paediatric trained staff being involved in CPC services in the community. Some papers did express interest in having a specialist paediatric-trained nurse in the community to support adult SPC professionals in their role and the overall coordination of care [27, 51, 52, 62]. This could be important as some papers had identified how adult SPC professionals are sometimes confused about their role in the community due to a lack of communication or coordination with other community health professionals [27, 28, 59]. Notably, there was no comparison made on whether the gap in confidence or knowledge was due to the presence or absence of universal health coverage, or the availability of trained CPC specialists in their respective country.

CPC training programmes

Many of the papers in this review developed training programmes in order to improve the gap in knowledge and address the lack of confidence, comfort or preparedness in adult SPC professionals providing CPC in the community. It is clear that adult SPC professionals have a desire to receive additional training in CPC [22–24, 26, 28, 50, 52, 54, 55, 59–62]. With one paper stating that adult SPC professionals felt “reinvigorated” and “inspired” after a 2-day education programme on paediatric palliative and hospice care [55] (p.211). It is important to consider how experienced the population in these studies were. The population cohorts in these studies were usually quite inexperienced with less than 5 or 10 years of clinical experience for the sample majority [22, 25, 51, 54, 55].

With regards to the training, many papers developed their programme using their own needs assessment [25, 26, 56], or through Delphi studies and professional expertise [53, 54]. One study developed an education program using input from a pilot group but did not specify its sample size or composition [55]. The training varied in content, frequency, structure and mode of delivery and trainer. Chosen education content and identified learning needs of adult SPC professionals are broken down in Table 2. The most common frequency was a short 1–2 day training [53–56]. While others focussed on a more regular education programme that occurs weekly, biweekly [25] or monthly [26]. The most common mode of delivery was in-person [53–56], but there was interest from adult SPC professionals to have education sessions delivered online [56]. Trainers providing the education were usually paediatric trained staff [25, 26, 53, 54].

Table 2.

Training topics and learning needs identified in the literature

| CPC training topics for adult specialist palliative care professionals | Common learning needs identified by adult specialist palliative care professionals |

|---|---|

| Introduction to CPC (e.g. define CPC, CPC history, current CPC services, patient stories) [26, 53, 56] | Understanding what children’s palliative care is [24, 62] |

| Symptom and pain assessments and management (e.g. nausea, vomiting, constipation, fatigue, pruritis, dyspnoea, agitation, secretions, delirium, sleep problems etc.) [25, 26, 53, 56] | Understanding of childhood life-limiting conditions [23, 24, 61, 62] |

| Medication management (e.g. palliative sedation, opioid use in children) [25, 26] | Assessment skills for child patients (e.g. general health assessments, pain assessments etc.) [23, 25] |

| Psychosocial support for children and families (e.g. identifying and managing depression and anxiety in children, spiritual considerations, respite care, supportive therapies such as music therapy, art, aromatherapy) [25, 26, 53, 56] | Symptom and pain assessments and management (e.g. pain, seizures, dyspnoea, secretions, neuro-irritability) [22, 26, 27, 52, 55, 60] |

| Communication skills (e.g. communicating according to child's developmental levels, advance care planning, breaking bad news, talking about death and dying etc.) [25, 26, 53, 54, 56] | Medication management (e.g. different dosages, different medications, palliative sedation) [23, 25, 27, 55, 60] |

| Grief and bereavement (e.g. assessment/management of grief, grief during different stages of development, complex grief) [26, 54, 56] | Psychosocial support for children and families (e.g. managing depression or anxiety in child or family) [22, 25–27, 62] |

| End of life care (e.g. resuscitation, caring for the dying child, medical assistance in dying) [26, 56] | Communication skills (e.g. advance care planning, goals of care, communication after child's death, communication on death or dying, coordinating care, prognostication questions) [22, 23, 25–27, 52, 53, 55, 60, 61] |

| Ethical and legal issues regarding CPC [26, 56] | Grief and bereavement (adolescents’ bereavement or grief, siblings’ grief) [26, 52, 54, 55] |

| Perinatal and neonatal palliative care [26, 56] | End of life care (e.g. what to expect and how to manage) [27, 48, 52, 61] |

| Transition from children to adult services [26] | Using medical equipment (e.g. respiratory machines, extubation at home) [27, 55] |

| Growing a CPC skillset in the rural setting [56] | Explaining the concept of "allowing a natural death" to the child or family [53] |

| Hydration and nutrition in CPC [55] | |

| Medical marijuana [26] |

Challenges

There were several challenges identified by adult SPC professionals including barriers to receiving additional CPC training and barriers preventing them from providing their services to children in the community.

The identified barriers to receiving CPC training were limited time [48, 54], limited finances [48], or lack of awareness of training opportunities or benefits of the training [60].

Several barriers were identified in regards to restricting professionals from providing their services to children in the community including lack of trained staff [22, 23, 27, 28, 59, 61], lack of finances [22, 23, 50], lack of resources e.g. access to home infusions or durable medical equipment [22, 27, 59, 61], lack of perceived benefits or understanding of their role in the community [24, 27], or how increasingly remote a child’s home is [50]. One paper noted the lack of children in the community requiring the services as one of the reasons for not providing CPC services [50].

Future directions

From the review it is clear that adult SPC professionals both perceive that they need and want additional CPC training so they can provide effective care to children in the community. It was evident that papers developing their own education programs showed variation in delivery. They usually provided either regular virtual training sessions or a once off in-person training workshop. Both were received well by attendees. However, there may have been a preference for a virtual platform with various challenges identified for in-person training such as difficulty working around busy working schedules [48, 54], or lack of finance to provide accommodation overnight [56]. In one paper, adult SPC professionals noted that a once off training does not sufficiently prepare them with one nurse saying “I mean, I got a whole week and a half of (CPC) training total in hospice, and then I had to wing it on my own.” [60] (p.6). Future studies should explore whether single-session or recurring training, and whether virtual or in-person delivery, is the most preferred and effective for this cohort.

There were a number of identified future research directions or gaps in the literature highlighted in this review. Regarding gaps, only 1 paper reported patient-reported outcomes (PROs) from their research [57], while 2 papers noted that there is a need for more PROs or data collected directly from patients or families [52, 55]. Recommendations have been made for more longitudinally designed studies in the future to evaluate the nursing impact on patient outcomes related to CPC training [53]. Others have advocated for more public awareness around CPC [24, 27]. An increase in collaboration with CPC hospital teams and adult SPC professionals in the community was voiced [50, 51, 59, 62]. Additionally, a need for a greater focus on rural, regional or LMICs were voiced [25, 28, 50, 54]. Studies from Malaysia [23] and Australia [54] noted the need for the standardisation of CPC training in undergraduate education for healthcare professionals. One paper noted that adult SPC professionals advocated for more community supports and respite services, rather than the development of more children hospices [61]. Emphasising the need for community providers to be sufficiently prepared, confident and trained to provide their services to children.

Discussion

Twenty studies were identified from the screening of the literature. Evidently there was little empirical evidence retrieved from this review. However, the content of the papers highlighted specific concepts in the literature, identified research gaps, and provided recommendations for future studies.

Four concepts were identified. The first concept examined adult SPC professionals’ training and clinical experience in CPC. Evidence demonstrated that adult SPC professionals are not formally trained to care for children nor do they routinely care for children in the community, regardless of the country’s level of development in palliative care. Reasons for the lack of training and experience were multifaceted and included factors such as lack of staff, resources, time, awareness of training and finances. This is not surprising as there has been growing evidence that adult SPC professionals are caring for children without formal training in North America [63, 64], Europe [27, 28, 65, 66] and globally [67]. In addition, many papers clearly lacked data on the prior training or exposure adult SPC professionals had in CPC. This made it unclear whether some study samples included what is defined as ‘adult SPC professionals’, creating a challenge for the data extraction and interpretation of the findings. This lack in data raises questions on whether CPC education is considered important in the literature for these professionals, or whether there is simply an absence of a clear definition of the ‘adult SPC professional’. It is essential for studies to collect relevant information from their participants. In this context, asking participants how many children they have cared for and whether they hold any paediatric qualifications can help explain variations in reported knowledge and confidence levels.

The second concept was on levels of knowledge, preparedness and confidence. The majority of adult SPC professionals felt unprepared and that they lacked knowledge, experience, preparedness, comfort and confidence when it comes to providing CPC in the community. The papers that did identify good pre-training levels of knowledge did not collect enough information on the adult SPC professionals’ previous experience or training to provide any reasons why. When papers were able to provide answers, the reasons could be seen to contradict each other at times. One example could be where one paper found that nurses with more years of experience felt most prepared while another paper highlighted that years of experience did not matter but whether staff were paediatric trained. Contradictions within the findings like these emphasise the need for more rigorous evidence-based research to be conducted in this area.

The third concept looked at the challenges of providing high quality CPC in the community. This was split into barriers preventing adult SPC professionals from receiving CPC training and from accepting more children into their care. However, insufficient staff education and resources emerged as the most prominent barriers to children receiving CPC in the community. While limited time was a common barrier to accessing CPC training.

Lastly, future directions in CPC were discussed. Papers highlighted the need for a universal measure of CPC need, standardised CPC education for adult SPC professionals and undergraduates, research on the most effective modes of delivery for CPC education (online vs in-person, regular vs once-off), more studies evaluating PROs, more collaboration between community and hospital-based teams, and incorporating a paediatric-trained nurse coordinator as a bridge between adult SPC professionals in the community and CPC experts. All very important directions to enhance our knowledge within the literature.

Regarding the limitations of this review, the majority of these studies included small samples with only 3 studies having a sample population larger than 100 [51, 52, 62]. These small sample sizes can affect the generalizability of the studies. Papers were also limited to the English language, possibly skewing the global perspective on adult SPC professionals caring for children in the community.

Conclusions

This scoping review has provided insights into what is anecdotally known about the current landscape of adult SPC professionals’ training, preparedness, and challenges providing CPC in the community. Ultimately, adult SPC professionals do not feel adequately prepared to provide CPC in the community. They do not receive standardised CPC training even though there is a clear demand for it. They do not have regular exposure to paediatric patients for a variety of systemic reasons. All of which reinforces the uncertainty surrounding their role in the community. This highlights the need to establish clear and appropriate expectations and training for this cohort of professionals.

Research gaps such as the lack of consensus on the conditions suitable for CPC, lack of PROs in CPC research, and fragmented care coordination in the community continues to be an issue even though CPC is already in its fourth decade of research. Future research should prioritise these areas to ensure we protect and enhance the preparedness and confidence of adult SPC professionals delivering CPC in the community.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1. Supplemental File Number 1: Search strategy used for PubMed database. Supplemental File Number 2: Data Extraction Table.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Maria Brenner, Professor of Children's Nursing at University College Dublin, for her support in the design of the research question. We also extend our gratitude to Fiona Lawler, Specialist Librarian at Our Lady's Hospice and Care Services, and Diarmuid Stokes, Health Sciences Librarian at University College Dublin for their guidance and assistance during the literature search.

Abbreviations

- CPC

Children’s Palliative Care

- SPC

Specialist Palliative Care

- LLC

Life-limiting condition

- PRO

Patient reported outcome

- LMICs

Low- and middle-income countries

Authors’ contributions

The first draft of the manuscript was written by MMD with support from MC and MB, and all the affiliated authors commented on and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

Consortium MMD is a MSc student and is funded by Professor Andrew Davies’s research account at the Academic Department of Palliative Medicine, Our Lady’s Hospice and Care Services, Dublin, Ireland.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organisation. Palliative care for children. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2023. https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/palliative-care-for-children#:~:text=Palliative. [Updated 1 June 2023; cited 2025 28 Apr]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Connor SR, Downing J, Marston J. Estimating the global need for palliative care for children: a cross-sectional analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(2):171–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delamere T, Balfe J, Fraser LK, Sheaf G, Smith S. Defining and quantifying population-level need for children’s palliative care: findings from a rapid scoping review. BMC Palliat Care. 2024;23(1):212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organisation. Integrating palliative care and symptom relief into paediatrics: A WHO guide for health care planners, implementers and managers. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hain R, Devins M, Hastings R, Noyes J. Paediatric palliative care: development and pilot study of a “Directory” of life-limiting conditions. BMC Palliat Care. 2013;12(1):43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noyes J, Edwards RT, Hastings RP, et al. Evidence-based planning and costing palliative care services for children: novel multi-method epidemiological and economic exemplar. BMC Palliat Care. 2013;12(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jankovic M, De Zen L, Pellegatta F, et al. A consensus conference report on defining the eligibility criteria for pediatric palliative care in Italy. Ital J Pediatr. 2019;45(1):89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benini F, Papadatou D, Bernada M, et al. International standards for pediatric palliative care: from IMPaCCT to GO-PPaCS. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;63(5):e529–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraser LK, Bluebond-Langner M, Ling J. Advances and challenges in european paediatric palliative care. Med Sci (Basel). 2020;8(2)1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Lu Q, Xiang ST, Lin KY, Deng Y, Li X. Estimation of pediatric end-of-life palliative care needs in china: a secondary analysis of mortality data from the 2017 national mortality surveillance system. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;59(6):e5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Association for children with life-threatening or terminal conditions and their families (ACT) and the royal college of paediatrics and child health (RCPCH). A guide to the development of children's palliative care services. Bristol: ACT; 1997.

- 12. Together for short lives. A guide to children’s palliative care. Bristol: Together for short lives; 2018.

- 13.Fraser LK, Miller M, Hain R, et al. Rising national prevalence of life-limiting conditions in children in England. Pediatrics. 2012;129(4):e923–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quinn C, McCarthy S, Devins M, O’Reilly M, Twomey M, Ling J. Prioritisation of future research topics in paediatric palliative care in Ireland: a Delphi study. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2017;23(2):88–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell S, Morris A, Bennett K, Sajid L, Dale J. Specialist paediatric palliative care services: what are the benefits? Arch Dis Child. 2017;102(10):923–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Department of Health. National Adult palliative care policy. Dublin: Stationary Office; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Field MJB, R.E. When children die: improving palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families. 1st ed. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed]

- 18.England NHS. Specialist palliative and end of life care services: Adult service specification. London: NHS England; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Friebert SE WC. NHPCO facts and figures: Pediatric palliative & hospice care in America. Alexandria, VA: National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization; 2014.

- 20.Marston J, Boucher S, Downing J. International Children’s palliative care network: a global action network for children with life-limiting conditions. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(2S):S104–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brock KE. Urgent appeal from hospice nurses for pediatric palliative care training and community. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10): e2127958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bogetz JF, Anderson A, Holland M, Macauley R. Pediatric hospice and palliative care services and needs across the Northwest United States. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;64(1):e7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chong L, Abdullah A. Community palliative care nurses’ challenges and coping strategies on delivering home-based pediatric palliative care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2017;34(2):125–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang KA, Yu S, Kim CH, et al. Nurses’ perceived needs and barriers regarding pediatric palliative care: a mixed-methods study. J Hosp Palliat Care. 2022;25(2):85–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doherty M, Rayala S, Evans E, Rowe J, Rapelli V, Palat G. Using virtual learning to build pediatric palliative care capacity in south asia: experiences of implementing a teleteaching and mentorship program (Project ECHO). JCO Glob Oncol. 2021;7:210–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lalloo C, Osei-Twum JA, Rapoport A, et al. Pediatric project ECHO(R): a virtual community of practice to improve palliative care knowledge and self-efficacy among interprofessional health care providers. J Palliat Med. 2021;24(7):1036–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quinn C, Bailey ME. Caring for children and families in the community: experiences of Irish palliative care clinical nurse specialists. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2011;17(11):561–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reid FC. Lived experiences of adult community nurses delivering palliative care to children and young people in rural areas. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2013;19(11):541–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance and World Health Organisation. Global atlas of palliative care. London: Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance; 2020.

- 30.Downing JLJ, Benini F, Payne S, Papadatou D. Core competencies for education in Paediatric palliative care. Milano: European Association for Palliative Care; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooper J. End of life care: strengthening choice. An inquiry report by the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) for Children Who Need Palliative Care. England: The All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) for Children Who Need Palliative Care; 2018.

- 32.Craig F, Abu-Saad Huijer H, Benini F, Kuttner L, Wood C, Feraris PC, Zernikow B. IMPaCCT: standards of paediatric palliative care. Schmerz. 2008;22(4):401–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neilson S, Randall D, McNamara K, Downing J. Children’s palliative care education and training: developing an education standard framework and audit. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Downing J, Ling J. Education in children’s palliative care across Europe and internationally. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2012;18(3):115–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slater PJ, Herbert AR, Baggio SJ, Donovan LA, McLarty AM, Duffield JA, et al. Evaluating the impact of national education in pediatric palliative care: the quality of care collaborative Australia. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:927–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Postier AC, Wolfe J, Hauser J, Remke SS, Baker JN, Kolste A, et al. Education in Palliative and end-of-life care-pediatrics: curriculum use and dissemination. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;63(3):349–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Armstrong R, Hall BJ, Doyle J, Waters E. Cochrane update. “Scoping the scope” of a cochrane review. Public Health (Oxf). 2011;33(1):147–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Munn Z, Peters M, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arksey HOM L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Intern J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peters MDGC, McInerney P, et al. Scoping reviews. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. 2020;10:10–46658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGowan J, Straus S, Moher D, et al. Reporting scoping reviews—PRISMA ScR extension. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;123:177–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McDonnell M, Connolly, M. Adult Specialist Palliative Care Providers Caring for Children in the Community: Protocol for a Scoping Review. Open Sci Frame. 2024. Available from: 10.17605/OSF.IO/8D4HA. Cited 10 Nov 2024 .

- 43.Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(10):2119–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. NHS England. Ambitions for palliative and end of life care: a national framework for local action 2021–2026. National Palliative and End of Life Care Partnership. England: NHS England; 2021.

- 45.Cherny NIFMT, Kassa S. Oxford Textbook of palliative medicine. 6th ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 46.United Nations. Conventions of the rights of the child. Geneva: United Nations; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;134:103–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jeffrey D. Education in palliative care: a qualitative evaluation of the present state and the needs of general practitioners and community nurses. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 1994;3(2):67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clelland D, van Steijn D, Macdonald ME, Connor S, Centeno C, Clark D. Global development of children’s palliative care: an international survey of in-nation expert perceptions in 2017. Wellcome Open Res. 2020;5:99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johnson K, Allen KE, West W, Williams-Kirkwood W, Wasilewski-Masker K, Escoffery C, Brock KE. Strengths, gaps, and opportunities: results of a statewide community needs assessment of pediatric palliative care and hospice resources. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(3):512-21e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaye EC, Gattas M, Kiefer A, et al. Investigation of modifiable variables to increase hospice nurse comfort with care provision to children and families in the community: a population-level study across Tennessee, Mississippi, and Arkansas. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(6):1144–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaye EC, Gattas M, Kiefer A, et al. Provision of palliative and hospice care to children in the community: a population study of hospice nurses. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;57(2):241–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hamre TJ, O’Shea ER, Hinderer KA, Mosha MH, Wentland BA. Impact of an evidence-based pediatric palliative care program on nurses’ self-efficacy. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2022;53(6):264–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kristjanson L, Cousins K, Macpherson R, Dadd G, Watkins R. Evaluation of a nurse education workshop on children’s grief. Contemp Nurse. 2005;20(2):193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vesel T, Beveridge C. From Fear to Confidence: Changing Providers’ Attitudes About Pediatric Palliative and Hospice Care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(2):205-12e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weaver MS, Jenkins R, Wichman C, Robinson JE, Potthoff MR, Menicucci T, Vail CA. Sowing across a state: development and delivery of a grassroots pediatric palliative care nursing curriculum. J Palliat Care. 2021;36(1):22–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weaver MS, Robinson JE, Shostrom VK, Hinds PS. Telehealth Acceptability for children, family, and adult hospice nurses when integrating the pediatric palliative inpatient provider during sequential rural home hospice visits. J Palliat Med. 2020;23(5):641–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Clark D, Baur N, Clelland D, Garralda E, Lopez-Fidalgo J, Connor S, Centeno C. Mapping levels of palliative care development in 198 countries: the situation in 2017. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;59(4):794-807e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Greenfield DK, Carter B, Harrop DE, et al. Healthcare professionals’ experiences of the barriers and facilitators to pediatric pain management in the community at end-of-life: a qualitative interview study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;63(1):98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Porter AS, Zalud K, Applegarth J, et al. Community hospice nurses’ perspectives on needs, preferences, and challenges related to caring for children with serious illness. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10): e2127457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Clarke J, Quin S. Professional carers’ experiences of providing a pediatric palliative care service in Ireland. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(9):1219–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kaye EC, Applegarth J, Gattas M, et al. Hospice nurses request paediatric-specific educational resources and training programs to improve care for children and families in the community: Qualitative data analysis from a population-level survey. Palliat Med. 2020;34(3):403–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weaver MS, Rosenberg AR, Tager J, Wichman CS, Wiener L. A summary of pediatric palliative care team structure and services as reported by centers caring for children with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(4):452–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carroll JM, Torkildson C, Winsness JS. Issues related to providing quality pediatric palliative care in the community. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54(5):813–27, xiii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Benini F, Orzalesi M, de Santi A, et al. Barriers to the development of pediatric palliative care in Italy. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2016;52(4):558–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zernikow B, Gertz B, Hasan C. Paediatric palliative care (PPC) - a particular challenge : Tasks, aims and specifics. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2017;60(1):76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Knapp C, Woodworth L, Wright M, et al. Pediatric palliative care provision around the world: a systematic review. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57(3):361–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1. Supplemental File Number 1: Search strategy used for PubMed database. Supplemental File Number 2: Data Extraction Table.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.