Abstract

In sepsis, immunosuppression is commonly observed as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) tolerance in macrophages. Leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor B2 (LILRB2) is an inhibitory receptor on immune cells that may play a crucial role in the immunosuppressive phenotype of LPS-tolerant macrophages, although its exact function in sepsis remains unclear. In this study, macrophages were exposed to single or sequential LPS doses to induce LPS stimulation or tolerance. Cell viability was assessed using CCK-8 assay, apoptosis, and macrophage polarization were detected by flow cytometry, and pro-inflammatory cytokine levels were measured by RT-qPCR and ELISA. Molecular interactions were explored using Co-IP, ChIP, and dual-luciferase assays, while mRNA and protein expression were assessed by RT-qPCR and Western blotting. The results showed that LILRB2 was upregulated in macrophages following LPS stimulation, with a more significant increase in the LPS-tolerant group. Knocking down LILRB2 reversed the immunosuppressive phenotype of LPS-tolerant macrophages and restored the inhibition of MyD88/NF-κB signaling and p65 nuclear translocation caused by LPS tolerance. Mechanistically, LILRB2 interacted with Toll-like receptor 8 (TLR8) to inhibit the MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway in LPS-tolerant macrophages. Furthermore, the upregulation of the Spi-1 proto-oncogene (SPI1) enhanced the immunosuppressive phenotype by transcriptionally activating LILRB2. In conclusion, SPI1 upregulation promoted the immunosuppressive phenotype of LPS-tolerant macrophages by activating LILRB2 transcription, which inhibited TLR8-mediated MyD88/NF-κB signaling. This study clarifies the role of LILRB2 and its underlying mechanisms in LPS-tolerant macrophages.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13062-025-00669-0.

Keywords: LILRB2, SPI1, Sepsis, LPS-tolerant macrophages, Immunosuppressive phenotype, MyD88/NF-κB signaling

Introduction

Sepsis is a critical medical condition marked by dysregulated immune responses to infections, often resulting in multi-organ failure and high mortality rates [1]. Each year, around 30 million individuals develop sepsis or septic shock, and the figure is rising annually, making sepsis/septic shock a significant global health issue [2]. Sepsis pathogenesis is complex, involving both excessive inflammation and simultaneous immunosuppression due to impaired immune cell responses. This immunosuppression heightens the risk of secondary infections in patients with advanced sepsis, often leading to death [3]. Despite advances in the clinical management of sepsis, there remains a critical need for effective therapeutic strategies that specifically address immunosuppression [4]. Therefore, it is necessary to elucidate the pathogenesis of immune dysfunction in sepsis, to lay the theoretical foundation for the diagnosis, prevention, and effective treatment of sepsis.

Macrophages are pivotal in the pathophysiology of sepsis [5, 6]. Upon recognizing pathogen-associated molecular patterns, such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS), via Toll-like receptors (TLRs), macrophages facilitate the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, thereby initiating the host’s defense mechanisms [7]. However, prolonged exposure to LPS leads to macrophage reprogramming, resulting in an immunosuppressive phenotype characterized by diminished production of pro-inflammatory factors, a process known as LPS tolerance, which is resistant to subsequent LPS-induced activation [8]. In addition, this process induces significant macrophage apoptosis, ultimately contributing to immune dysfunction [9]. While LPS tolerance-induced immunosuppression in macrophages can alleviate the excessive inflammatory response characteristic of sepsis, it also compromises the macrophages’ defensive capabilities, heightening the risk of secondary infections and exacerbating clinical [10]. However, the current research mainly focuses on the inflammatory response of macrophages in the early stage of sepsis [11, 12], with limited investigation into the mechanism of LPS tolerance in macrophages during the late stage of sepsis, so further exploration is warranted.

Recent studies have underscored the importance of leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor B2 (LILRB2), an inhibitory receptor involved in immunoregulation across a spectrum of diseases. In the context of oncology, LILRB2 has been implicated in facilitating immune evasion [13, 14]. Additionally, aberrant expression of LILRB2 has been observed in monocytes following LPS stimulation during sepsis [15, 16]. In septic mice, increased expression of LILRB2 in peripheral blood monocytes was observed alongside elevated serum IL-6 levels, collectively contributing to immune dysregulation within the septic model [17]. This suggests a potential role for LILRB2 in modulating immune responses during sepsis. Nevertheless, the specific mechanistic role of LILRB2 in sepsis-induced immunosuppression remains to be elucidated. Given its immunological characteristics, we propose that LILRB2 may play a pivotal role in sepsis-related immunosuppression, warranting further investigation.

Recent research has elucidated the pivotal role of the TLR/NF-κB signaling pathway in mediating immune responses during sepsis [18]. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) function as primary sensors for microbial elements such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS). Upon activation, TLRs engage the adaptor protein MyD88, which subsequently initiates the nuclear translocation of NF-κB and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines [19, 20]. The activation of the NF-κB pathway is instrumental in the production of inflammatory cytokines, which are crucial for the host’s defense against infections [21]. Importantly, the TLR/NF-κB axis is a well-characterized inflammatory signaling cascade that is implicated in the pathogenesis of sepsis [22]. Intriguingly, bioinformatic analyses from the biogrid database have predicted a potential interaction between LILRB2 and TLR8. Given the possibility that LILRB2 may bind to TLR8, we propose the hypothesis that LILRB2 could modulate the MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway, thereby contributing to immunosuppression in the context of sepsis..

SPI1, an ETS-domain transcription factor, plays a crucial role in the regulation of myeloid and B-cell development as well as macrophage activation, with mutations in this gene linked to immunodeficiency [23]. An RNA-Seq analysis conducted on 23 sepsis patients and 10 healthy controls demonstrated a significant upregulation of SPI1 in the peripheral blood monocytes of septic individuals [24]. Recent studies demonstrate that SPI1 transcriptionally activates PLA2G7, thereby exacerbating inflammatory responses in sepsis [25]. Intriguingly, bioinformatic prediction (Genecard) identifies SPI1 as the exclusive potential transcription factor for LILRB2. Based on these sights, we hypothesized that SPI1-mediated transcriptional activation of LILRB2 contributes to immunosuppression in sepsis through a novel mechanism: the upregulated LILRB2 interacts with TLR8, leading to the inhibition of the TLR8/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway. This study has the potential to identify promising therapeutic targets aimed at reversing immunosuppression in late-stage sepsis.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and differentiation

THP-1 cell was purchased from Hunan Fenghui Biotechnology (Hunan, China). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from anonymized healthy adult donors were obtained from Wuhan Pricella Biotechnology (Wuhan, China) with informed consent. Human monocytes were isolated from PBMCs according to the instructions of RosetteSep™ Kit. THP-1 cells and human PBMCs were cultured under standard conditions in 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 50 U/mL penicillin, and 50 µg/mL streptomycin [26]. THP-1 cells were differentiated into macrophages by treatment with 150 ng/mL PMA (Millipore Sigma) for 24 h [26]. Peripheral blood-derived macrophages grown in granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) were generated as described previously [27]. Human PBMCs were cultured in 5000 U/mL GM-CSF (BioLegend) [28]. On day 4, nonadherent cells were collected and cultured for 3 days with 5000 U/mL fresh CSF. On day 7, adherent cells were collected. Then, THP-1 cells and peripheral blood-derived macrophages were cultured under similar conditions. These procedures were approved by the ethics of Beijing Tsinghua Changgung Hospital, and the ethical number was 25120-0-01. The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant ethical guidelines.

Treatment of LPS-tolerant macrophages

LPS-tolerant macrophages which are resistant to LPS-induced, were generated according to a previous study [27]. The immunological characteristics of LPS-tolerant macrophages have also been verified [28]. In summary, the procedure is as follows: Treatment-naive macrophages, which served as the control group, received no LPS treatment. Cells were stimulated with 10 ng/mL LPS for 24 h to generate non-tolerant macrophages. For LPS-tolerant macrophages, cells were first stimulated with 10 ng/mL LPS for 24 h and then re-treated with LPS to induce tolerance. To investigate the role of TLR8 in LPS-tolerant macrophages, a subset of macrophages was treated with 1 µg/mL TLR8-specific agonist VTX-2337 for 24 h.

Lentivirus packaging and infection

Lentiviral vectors of short hairpin RNAs (sh-LILRB2 and sh-SPI1) and overexpression plasmids (LV-LILRB2) were obtained from Hunan Fenghui Biotechnology. 293T cells were transfected with lentiviral vectors or mock vectors along with packaging plasmids using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for lentivirus production. Then, THP-1 cells were transduced using lentiviral supernatant. At 48 h post-transduction, the cells were subjected to selection with either 5 µg/mL puromycin (Thermo Fisher) for 5 days.

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

Cell proliferation was measured using the CCK-8 assay (Dojindo Laboratories). Cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 104 cells per well, followed by the addition of 10 µL of CCK8 reagent. After incubation for 3 h at 37℃, absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad).

Flow cytometry

According to the instructions in the Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit (Beyotime Biotechnology), 106 cells collected from each group were washed with PBS, and then mixed with 5 µL Annexin V-FITC and 10 µL PI. The samples were gently vortexed and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 15 min. Flow cytometry (BD FACSCanto II) was employed to detect apoptotic cells, and the data were analyzed in FlowJo software. Macrophage polarization was evaluated. Briefly, cells were stained with anti-CD86 (Abcam, ab239075) and anti-CD206 antibodies (Wuhan Proteintech, 18704-1-AP) and then analyzed using flow cytometry. The levels of these markers were quantified by measuring the mean fluorescence intensity.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP was implemented using the ChIP kit (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). Cells underwent treatment with 1% formaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min to crosslink DNA-protein complexes, and this was followed by a 5-minute quenching with 125 mM glycine and sonicated to shear DNA. Chromatin complexes were immunoprecipitated using the SPI1 antibody (Abcam, ab302623), DNA-protein complexes were eluted in 200 µL elution buffer, crosslinks were reversed by adding NaCl to 200 mM and incubating IP samples overnight at 65 °C (input DNA for 4 h), and proteins were digested with Proteinase K at 55 °C for 2 h. DNA fragments linked to them were purified for reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) to detect LILRB2 promoter sequences. Enrichment analysis was conducted via RT-qPCR (100% input).

Dual-luciferase reporter gene assay

PCR was utilized to amplify the LILRB2 promoter fragment to construct WT reporter plasmids. To create MUT reporter plasmids, a site-directed mutagenesis kit from Stratagene, CA, USA, was used to alter the SPI1 binding site within this fragment. LILRB2 promoter sequences for reporter plasmids were inserted into the pGL3 vector (Promega, WI, USA). 293T cells were subsequently co-transfected with either WT-LILRB2 or MUT-LILRB2 plasmids, together with OE-SPI1, utilizing Lipofectamine 2000 from Invitrogen. The luciferase activity was examined after 48 h of transfection. To ensure accuracy, the relative activity of firefly luciferase was normalized to that of Renilla luciferase.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

THP-1 cells and human macrophages were lysed in a lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C to clarify. The supernatant was pre-cleared with 30 µL protein A/G beads(Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h at 4 °C. 50 µL of lysate was saved as input. Then, beads were incubated with IgG (Abcam, ab172730), LILRB2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, H00010288-M01), and TLR8 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-135584) antibodies at 4℃ for 4 h. Following an overnight incubation with cell lysate, bound proteins were eluted and harvested for Western blot.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The experimental procedures are described in the cited literature [29], TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-8 levels in cell culture supernatants were quantified using ELISA kits (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured.

Nuclear-cytoplasmic fractionation

Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were isolated from cultured cells with the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were rinsed with ice-cold PBS and lysed in a cytoplasmic extraction reagent. The cytoplasmic portion was isolated, and then the nuclear pellet was broken down to extract the nuclear fraction. Finally, protein concentrations were determined by the BCA kit (Thermo Fisher) [30].

RT-qPCR

The extraction of total RNA was performed using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and 1 µg of RNA was converted into cDNA with the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit from Takara. RT-qPCR was conducted using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix on an ABI 7500 RT PCR system. Relative expression levels of target genes were normalized to β-actin (an internal control). Primer sequences are displayed in Supplementary Table 1.

Western blot (WB)

Protein samples were extracted from tissues or cell lysates, denatured at 100℃, and separated through sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) based on molecular weight. After this step, proteins were shifted onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) or nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was then blocked to prevent non-specific binding and incubated with antibodies against LILRB2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, H00010288-M01), TLR8 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-135584), P65 (Abcam, ab32536), p-P65 (Abcam, ab7630), MyD88 (Abcam, ab133739), p-TAK1 (Abcam, ab109404), and β-actin (Abcam, ab8226) overnight. Once the washes were completed, a secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was added, and the signal was visualized using electrochemiluminescence (ECL).

Data analysis

All experiments were done in biological triplicate. Data are manifested as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The data of this study were following the normal distribution and tested by the Shapiro-Wilk method. Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way ANOVA, and pairwise comparisons were made using Tukey’s honest significant difference test. P-values from post-hoc tests were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg (B–H) procedure for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. All analyses were made using GraphPad Prism software 9 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

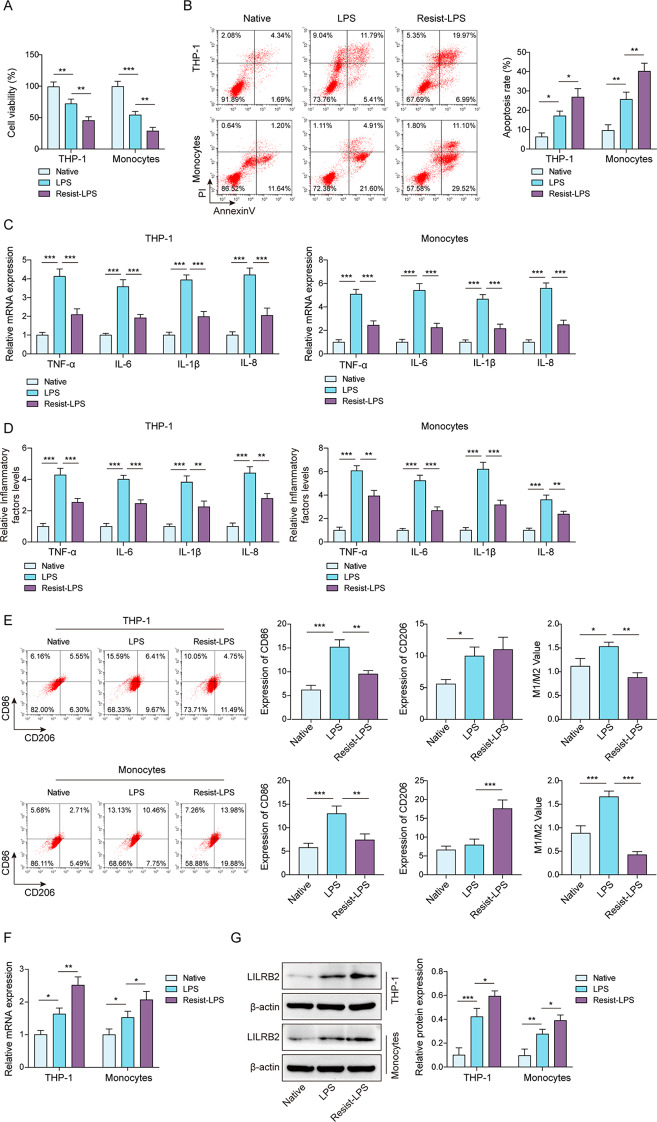

LPS-tolerant macrophages transformed into an immunosuppressive phenotype, along with a rise in LILRB2 expression

To induce mature macrophages, PBMCs were isolated and differentiated into macrophages as previously described [31]. THP-1 cells were induced into macrophages via PMA treatment [28]. An in vitro model of LPS-intolerant macrophages was induced through a single dose of LPS addition to the above macrophages for 24 h. After that, to prepare the LPS-tolerant environment of macrophages, we refer to previous studies to add LPS induction twice [32], and based on previous studies, we stimulated macrophages with a series of gradient concentrations of LPS (0, 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 ng/mL) to select the best induction concentration. The results showed that with the increase in LPS concentration, the cell viability decreased, but when the concentration was 10 ng/mL, the inflammatory factors decreased significantly (Figure S1), indicating that there were obvious LPS tolerance characteristics. Therefore, 10 ng/mL LPS was selected as the induction concentration for our subsequent experiments. As shown in Fig. 1A, LPS inhibited the viability of macrophages, and LPS-tolerant macrophages exposed to sequential doses of LPS exhibited an enhanced inhibitory effect of LPS on cell viability. LPS stimulation promoted apoptosis of macrophages and significant increases in apoptosis were observed in the LPS-tolerant group (Resist-LPS) compared with the LPS and control groups (Fig. 1B). In addition, LPS treatment significantly elevated pro-inflammatory factors (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-8), but these pro-inflammatory levels induced by a single dose of LPS were attenuated by sequential doses of LPS (Fig. 1C and D). M1 macrophages can be identified by CD86 expression, whereas M2 macrophages are predominantly expressed by CD206 [33]. The ratio of CD86/CD206 in macrophages was markedly increased by LPS stimulation but significantly reduced in LPS-tolerant macrophages (Fig. 1E). LILRB2 is an immune inhibitory receptor whose role in LPS-tolerant macrophages is unknown. The results elicited that LILRB2 was upregulated by LPS stimulation in macrophages; relative to the LPS group, LILRB2 was significantly upregulated in the LPS-tolerant group (Fig. 1F and G). The findings above indicated that LILRB2 might function as an immune inhibitory receptor in LPS-tolerant macrophages.

Fig. 1.

LILRB2 might function as an immunoinhibitory receptor in macrophages tolerant to LPS. Macrophages were incubated with either a single dose or sequential doses of LPS to induce LPS stimulation or LPS tolerance. (A) A CCK-8 assay was used to determine the viability of macrophages. (B) Apoptosis was detected using flow cytometry. (C) and (D) The levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-8 in macrophages were determined by RT-qPCR and ELISA assays, respectively. (E) CD86 and CD206 levels in macrophages were analyzed by flow cytometry. (F) and (G) The mRNA and protein levels of LILRB2 were detected by RT-qPCR and Western Blot assays. Each experiment was conducted in three biological replicates. Benjamini Hochberg for multiple comparisons of A-G. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

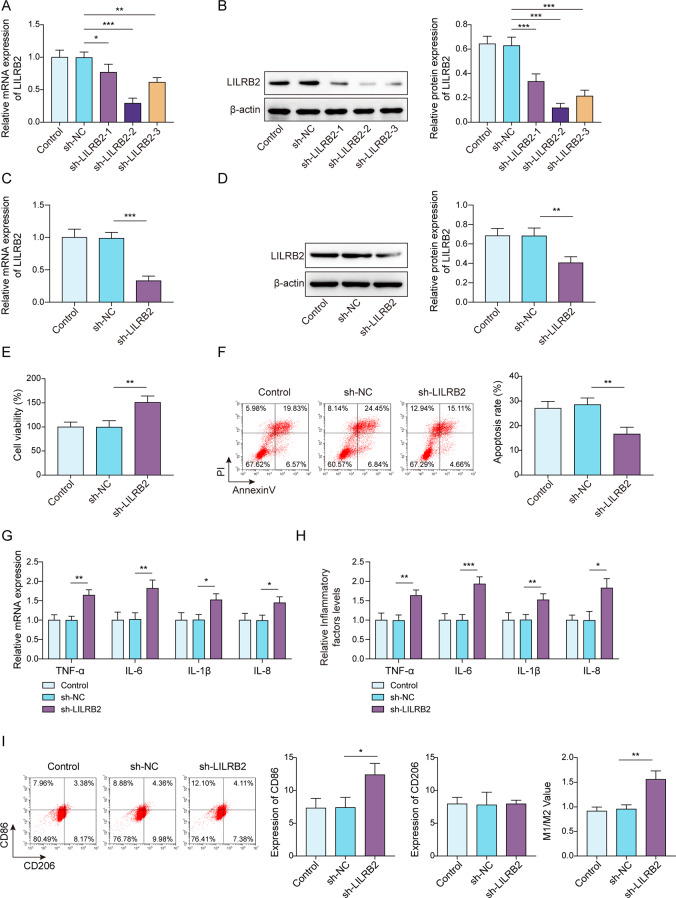

Knockdown of LILRB2 suppressed the immunosuppressive phenotype of LPS-tolerant macrophages

Since knocking down mRNA in PDMC-derived human macrophages is a major challenge, THP-1 cells were selected to generate stable LILRB2 knockdowns through lentiviral infection. As a result, sh-LILRB2-1, sh-LILRB2-2, and sh-LILRB2-3 infection significantly reduced LILRB2 mRNA and protein expression in macrophages (Fig. 2A and B), suggesting successful infection. In addition, the knockdown efficiency of sh-LILRB2-2 was the highest. After infection with sh-LILRB2 lentivirus, both transcription and translation of LILRB2 were knocked down in LPS-tolerant macrophages (Fig. 2C and D). Subsequent CCK-8 results subsequently showed that sh-LILRB2 infection decreased the inhibitory effects of LPS tolerance on cell viability compared to the control and sh-NC groups (Fig. 2E). LILRB2 knockdown reversed LPS tolerance-induced apoptosis in macrophages (Fig. 2F). Moreover, LILRB2 knockdown in macrophages partially reversed the inhibitory effect of LPS tolerance on pro-inflammatory factors (Fig. 2G and H). Flow cytometry noted that the inhibitory effect of LPS tolerance on macrophage M1 polarization was weakened by LILRB2 knockdown (Fig. 2I). Collectively, LILRB2 knockdown ameliorated the immunosuppressive phenotype of LPS-tolerant macrophages.

Fig. 2.

LILRB2 knockdown ameliorated the inhibitory effect of LPS tolerance in macrophages. THP-1 cells were infected with sh-NC, sh-LILRB2-1, sh-LILRB2-2, or sh-LILRB2-3. (A) and (B) LILRB2 expression was examined by RT-qPCR and Western Blot assays. Macrophages were given multiple doses of LPS in sequence to develop tolerance to LPS. (C) and (D) RT-qPCR and Western Blot were employed to detect LILRB2 expression in macrophages that were infected with sh-NC or sh-LILRB2. (E) CCK-8 assay was performed to examine the cell vitality, and (F) Flow cytometry was used to detect apoptosis of macrophages. (G) and (H) TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-8 levels in macrophages were determined by RT-qPCR and ELISA assays. (I) Flow cytometry was used to analyze the levels of CD86 and CD206 in macrophages. Each experiment was conducted in three biological replicates. Benjamini Hochberg for multiple comparisons of A-I. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

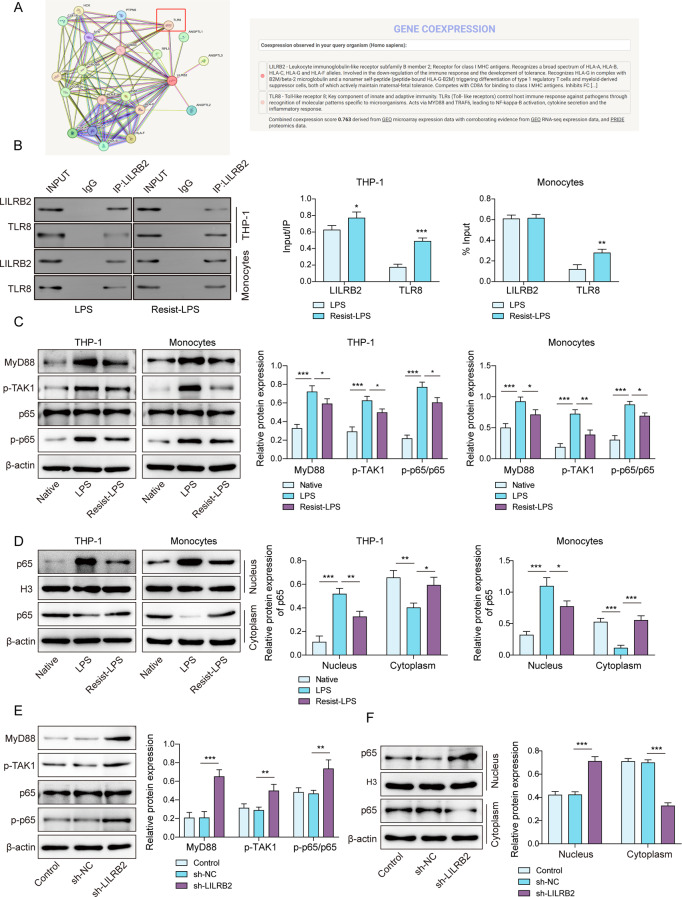

LILRB2 inhibited TLR8-mediated MyD88/NF-κB signaling by binding to TLR8

LILRB2 is known to transmit inhibitory signals in macrophages [34]. We conjectured that LILRB2 might exert an inhibitory role by binding to a certain protein to influence LPS tolerance in macrophages. With the help of the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING) database [35] (https://thebiogrid.org/), proteins that might interact with LILRB2 were identified, and a potential interaction between LILRB2 and TLR8 was found (Fig. 3A). TLR8 is an important recognition factor that drives bacteria to induce macrophage inflammation [36]. Co-IP assay elicited that the interaction between LILRB2 and TLR8 was significantly increased by LPS tolerance in macrophages (Fig. 3B). The MyD88/NF-κB pathway is the relevant innate immunity pathway for macrophages, which is regulated by TLR8 [37]. The MyD88/NF-κB pathway-related proteins (MyD88, p-TAK1, P65, and p-P65) were suppressed in LPS-tolerant macrophages (Fig. 3C). In addition, P65 protein levels in the nucleus were notably reduced after LPS tolerance (Fig. 3D). However, LILRB2 knockdown restored the inhibition of the MyD88/NF-κB pathway and P65 nuclear translocation caused by LPS tolerance (Fig. 3E and F). Collectively, LILRB2 could bind to TLR8 and inhibit the TLR8-mediated MyD88/NF-κB pathway.

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of MyD88/NF-κB signaling by LILRB2 was mediated through TLR8 binding in LPS-tolerant macrophages. (A) STRING used for analyzing interaction between LILRB2 and TLR8. (B) The relationship between LILRB2 and TLR8 was validated using Co-IP. (C) MyD88, p-TAK1, p65, and p-P65 protein expressions were determined by Western blot. (D) p65 protein expression in cytoplasm and nuclear parts of macrophage were detected by western blot. (E) and (F) Western blot used for detecting the MyD88/NF-κB pathway and p65 nuclear translocation. Each experiment was conducted in three biological replicates. Benjamini Hochberg for multiple comparisons of C-E. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

LILRB2 inhibited TLR8 to promote the immunosuppressive phenotype of LPS-tolerant macrophages

LILRB2 was overexpressed in macrophages (Fig. 4A and B), confirming the overexpression efficiency. VTX-2337, as a specific TLR8 agonist [38]. was used to investigate the regulatory link between TLR8 and LILRB2 in LPS-tolerant macrophages. First, LILRB2 overexpression elevated LILRB2 levels, with no changes in LILRB2 levels observed upon VTX-2337 treatment (Fig. 4C and D). LILRB2 overexpression significantly decreased cell viability, although this effect was reversed by VTX-2337 treatment (Fig. 4E). VTX-2337 treatment counteracted the heightened apoptosis induced by LILRB2 overexpression (Fig. 4F). LILRB2 overexpression markedly decreased levels of pro-inflammatory factors, but VTX-2337 treatment restored these levels in LPS-tolerant macrophages (Fig. 4G and H). VTX-2337 treatment mitigated the decreased macrophage M1 polarization (Fig. 4I) and restored the inhibition of the MyD88/NF-κB pathway and P65 nuclear translocation caused by LILRB2 overexpression (Fig. 4J and K).

Fig. 4.

The immunosuppressive characteristics of LPS-tolerant macrophages were promoted by LILRB2’s inhibition of TLR8. (A) and (B) THP-1 cells were infected with LV-NC and LV-LILRB2, and the expression of LILRB2 was evaluated using RT-qPCR and Western blot assay. Macrophages were given multiple doses of LPS in sequence to develop tolerance to it, and LILRB2 expression was detected using RT-qPCR (C) and Western blot (D). (E) The CCK-8 assay was utilized to assess cell vitality, (F) while flow cytometry was used to analyze macrophage apoptosis. (G) and (H) The levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-8 in macrophages were measured using RT-qPCR and ELISA. (I) Flow cytometry was used to analyze the levels of CD86 and CD206 in macrophages. (J) and (K) Western blot employed for the MyD88/NF-κB pathway and P65 nuclear translocation detection. Each experiment was conducted in three biological replicates. Benjamini Hochberg for multiple comparisons of C-K. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

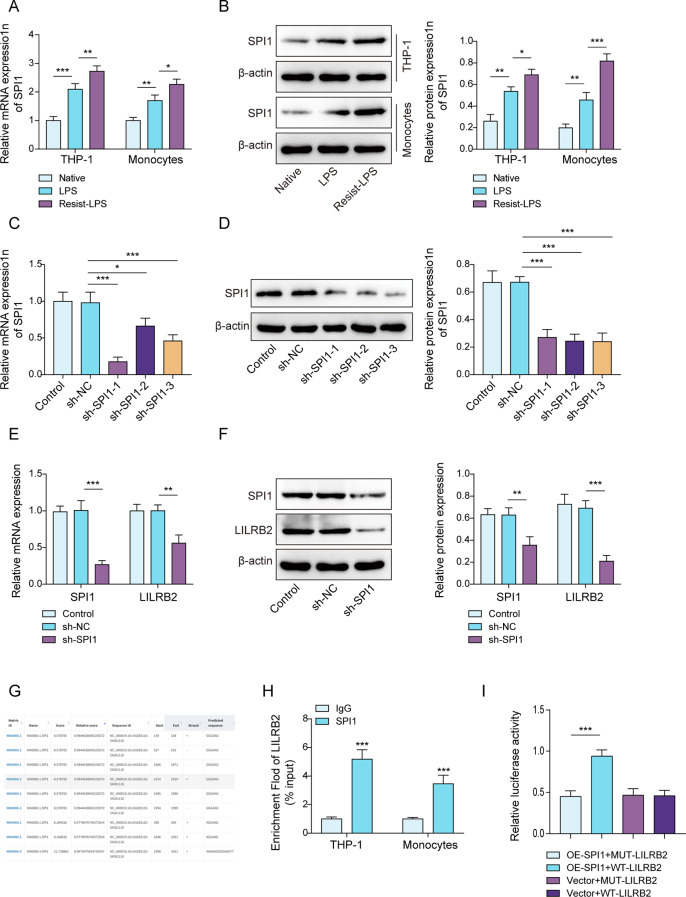

LILRB2 was upregulated by SPI1 via transcriptional activation

Through the GeneCard database (https://www.genecards.org/), we acquired a list of transcription factors that might bind to the LILRB2 promoter. Only the transcription factor SPI1 might regulate LILRB2 transcription. In macrophages, SPI1 was also found to be upregulated by LPS stimulation, especially in the LPS-tolerant group compared to the LPS group (Fig. 5A and B). THP-1 cells were chosen to establish macrophages with stable SPI1 knockdown through lentiviral infection. Consequently, sh-SPI1-1, sh-SPI1-2, and sh-SPI1-3 infections all markedly lowered SPI1 mRNA and protein expression in macrophages, and the knockdown efficiency of sh-SPI1-1 was the highest (Fig. 5C and D). SPI1 knockdown also decreased LILRB2 levels in LPS-tolerant macrophages (Fig. 5E and F), indicating that SPI1 is upstream of LILRB2. The expected SPI1 binding sites within the LILRB2 promoter region were delineated based on the JASPAR database analysis (Fig. 5G). The connection between SPI1 and LILRB2 was further confirmed through the ChIP assay (Fig. 5H). The regulation of LILRB2 promoter activity by SPI1 was confirmed through a dual-luciferase reporter assay (Fig. 5I). Overall, SPI1 increased LILRB2 expression by binding to its promoter region in LPS-tolerant macrophages.

Fig. 5.

LILRB2 was transcriptionally upregulated by SPI1 in LPS-tolerant macrophages. (A) and (B) THP-1 cells were infected with sh-NC, sh-SPI1-1, sh-SPI1-2, or sh-SPI1-3, the expression of SPI1 was assessed through RT-qPCR and Western blot assays (C and D). (E) and (F) RT-qPCR and Western blot were employed to detect LILRB2 and SPI1 expressions in LPS-tolerant macrophages that were infected with sh-NC or sh-SPI1. (G) JASPAR was used to predict the binding sites between SPI1 and LILRB2 promoter regions. (H) ChIP assay was used to confirm the binding relationship between SPI1 and LILRB2. (I) The interaction between SPI1 and LILRB2 was verified using a dual luciferase gene assay. Each experiment was conducted in three biological replicates. Benjamini Hochberg for multiple comparisons of A-F. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

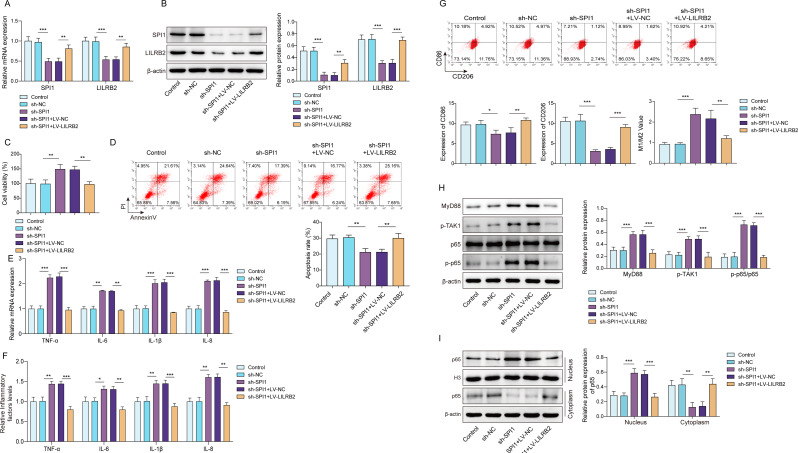

SPI1 promoted the immunosuppressive phenotype of LPS-tolerant macrophages by upregulating LILRB2 to inhibit TLR8-mediated signaling pathway

Finally, we explored whether SPI1 affected the immunosuppressive phenotype of LPS-tolerant macrophages by regulating LILRB2 to inhibit the TLR8-mediated signaling pathway. As results revealed, SPI1 knockdown decreased LILRB2 levels in LPS-tolerant macrophages, while LILRB2 overexpression reversed the effects (Fig. 6A and B). SPI1 knockdown significantly increased cell viability, although this effect was reversed by LILRB2 overexpression (Fig. 6C). The decreased apoptosis rate caused by SPI1 knockdown could be reversed by LILRB2 overexpression (Fig. 6D). Knocking down SPI1 notably elevated pro-inflammatory factors, whereas overexpressing LILRB2 restored these levels in LPS-tolerant macrophages (Fig. 6E and F). LILRB2 overexpression mitigated the increased macrophage M1 polarization (Fig. 6G) and the suppressed MyD88/NF-κB pathway and P65 nuclear translocation caused by SPI1 knockdown (Fig. 6H and I).

Fig. 6.

SPI1 enhanced the immunosuppressive characteristics of LPS-tolerant macrophages by increasing LILRB2 expression. Co-transfection of SPI1 knockdown, LILRB2 overexpression, or vector plasmids into LPS-tolerant macrophages, SPI1 and LILRB2 expressions in macrophages was detected using RT-qPCR (A) and Western blot (B). (C) The CCK-8 assay was utilized to assess cell vitality, (D) while flow cytometry was used to analyze macrophage apoptosis. (E) and (F) RT-qPCR and ELISA were used to measure the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-8 in macrophages. (G) Flow cytometry was used to analyze the levels of CD86 and CD206 in macrophages. (H) and (I) Western blot employed for the MyD88/NF-κB pathway and P65 nuclear translocation detection. Each experiment was conducted in three biological replicates. Benjamini Hochberg for multiple comparisons of A-I. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

Discussion

LPS tolerance in macrophages is a critical contributor to immunosuppression in sepsis [39]; however, its underlying mechanisms are not yet fully elucidated. Although the immunosuppressive receptor LILRB2 has been associated with various diseases [40], its specific role in LPS tolerance within macrophages remains unclear. This research demonstrates that SPI1 transcriptionally activated LILRB2, which in turn suppressed the TLR8/MyD88/NF-κB signaling, thereby promoting LPS tolerance in macrophages. These findings provide new insights into the mechanisms of immunosuppression in sepsis, highlighting LILRB2 as a potential therapeutic target for reversing LPS-induced tolerance in macrophages.

Sepsis-induced immunosuppression is characterized by dysregulated immune cell function [41]. As essential components of the immune defense system, macrophages engage in pathogen elimination through phagocytosis, cytokine production, and the initiation of inflammatory cascades [7]. However, excessive M1 polarization drives hyperinflammation, leading to septic shock and organ failure [42, 43]. Prolonged exposure to LPS induces a compensatory LPS-tolerant state that resembles M2 polarization, characterized by reduced inflammatory responses and increased apoptosis [9, 44–46]. While this adaptation prevents hyperinflammation, it simultaneously predisposes patients to secondary infections and exacerbates outcomes [47]. Notably, we observed a significant upregulation of the immunoregulatory receptor LILRB2 in LPS-tolerant macrophages, suggesting its potential involvement in this phenotypic transition.

Leukocyte Ig-like receptors (LILR; also referred to as LIR, ILT, and CD85) comprise a family of 11 immune regulatory receptors, including inhibitory members (LILRB1-5) that modulate the function of antigen-presenting cells through immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs (ITIMs). These receptors recruit SHP1/2 phosphatases to attenuate downstream signaling cascades [48, 49]. Furthermore, LILRB is frequently overexpressed in cells associated with immunosuppression, such as M2 macrophages and tolerant dendritic cells [50]. LILRB2, a prominent immunosuppressive member, is frequently overexpressed in M2 macrophages and contributes to immune evasion in tumors and chronic inflammatory conditions [13, 34]. Mechanistically, LILRB2 promotes M2 polarization whereas its inhibition induces M1 reprogramming via NF-κB/STAT1 activation [34]. Our research reveals that LILRB2 knockdown can alleviate LPS tolerance in macrophages to a certain extent. Further exploration is needed for its downstream regulation.

The immune response initiated by TLRs serves as the host’s primary defense mechanism against pathogenic invasion [51]. Pathogenic bacteria produce virulence factors, such as LPS, which can induce M1 macrophage polarization through TLR stimulation [52]. The TLR/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway enhances bactericidal activity by promoting the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [19, 20]. Among the TLRs, TLR8 is specifically responsible for recognizing bacterial RNA from common nosocomial pathogens including Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus pneumoniae) [53–55]. This recognition triggers MyD88-dependent NF-κB activation leading to the release of TNF-α and IL-6 [56]. Our research revealed that LILRB2 interacted with TLR8 to inhibit this signaling pathway, thereby suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines production and promoting an anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype. This interaction between LILRB2 and TLR8 plays a mechanistic role in late-stage sepsis immunosuppression, which is characterized by diminished macrophage responsiveness to pathogens. Previous studies have predominantly focused on mechanisms such as IRAK-M upregulation [57], SOCS1/3 induction, or epigenetic reprogramming [58] to elucidate LPS tolerance. Our study identifies LILRB2 as a novel regulatory element, offering a targetable surface receptor for modulating LPS tolerance. This aligns with the established role of LILRB2 in immune regulation, particularly in cancer immunotherapy [13].

SPI1, a vital ETS-domain transcription factor, critically regulates myeloid and B-lymphoid development. Mutations in SPI1 lead to alterations in chromatin accessibility, impair B-cell differentiation, and drive immunodeficiency disorders, such as agammaglobulinemia [23]. Additionally, SPI1 facilitates the expression of immune checkpoint molecules in myeloid cells, thereby promoting tumor immune evasion and immunosuppression [59]. It also orchestrates macrophage activation and differentiation by regulating key gene networks, underscoring its significant role in immune regulation and inflammatory responses [60, 61]. The concept of transcriptional factor activation influencing downstream gene expression in disease progression is well-established. In sepsis, macrophage-specific knockout of ATF4 disrupts glycolytic flux and mediates immune tolerance by targeting HK2 ubiquitination and HIF-1α stabilization [62]. Our findings revealed that SPI1 transcriptionally upregulates LILRB2, amplifying immunosuppression in LPS-tolerant macrophages. This SPI1-LILRB2 axis critically regulates septic immune dysfunction, identifying LILRB2 as both a key modulator in macrophages and a promising therapeutic target for reversing sepsis-induced immunosuppression.

This study introduces innovative insights into the role of LILRB2 in promoting LPS tolerance in macrophages through the inhibition of TLR8-mediated MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathways. The importance of this research is underscored by its potential to address a significant challenge in sepsis treatment: immunosuppression. LILRB2 has been identified as a pivotal regulator of macrophage LPS tolerance, and targeting this molecule may restore macrophage functionality and enhance the immune response in septic patients, thereby potentially reducing sepsis-related mortality. Future clinical interventions could involve the use of LILRB2-targeted antibodies or small-molecule agonists to amplify its inhibitory signaling. Proposed strategies include the development of monoclonal antibodies or fusion proteins specifically targeting LILRB2 to suppress hyperactive autoreactive immune cells, as well as blocking pathogen-induced interference with LILRB2 signaling to restore immune surveillance and counteract immune evasion mechanisms. Additionally, the transcriptional regulation of LILRB2 by SPI1 offers additional avenues for research, suggesting that modulating SPI1 activity could serve as a therapeutic strategy. Given the pivotal role of macrophages in both the inflammatory and immunosuppressive phases of sepsis, this study provides a foundation for future exploration and therapeutic development.

Despite the promising findings, this study is subject to several limitations. Firstly, given the technical challenges and instability associated with primary cell knockdown, our investigation of LILRB2’s role in LPS tolerance was primarily conducted using THP-1-derived macrophages, rather than PBMCs, which more accurately replicate the septic microenvironment. Additionally, the use of more stable reference genes, such as GAPDH and 18 S rRNA, for normalization would enhance the reliability of the Western blot analyses. Secondly, this study focused on in vitro systems to elucidate the mechanistic, cell-autonomous regulation of LILRB2 in macrophage LPS tolerance, thereby laying the groundwork for future translational validation in sepsis models. We recognize that in vivo validation in sepsis models is a crucial subsequent step, which we have explicitly outlined as a future direction. Thirdly, while our data underscore the critical role of the SPI1-LILRB2 axis in regulating LPS tolerance, the potential crosstalk with other immunoregulatory pathways requires further investigation. Specifically, LILRB2 may act synergistically with immune checkpoint molecules, such as PD-1 and CTLA-4, to enhance immunosuppression by inhibiting costimulatory signals including the CD28/B7 interaction, thereby maintaining T cell tolerance [63]. The engagement of LILRB2 could potentially suppress the activation of the MAPK pathway, leading to reduced production of inflammatory cytokines and the promotion of LPS tolerance [64]. These potential interactions underscore the necessity for systematic investigation of these pathways in future research endeavors. Finally, there is a lack of clinical data supporting the therapeutic efficacy of LILRB2-targeted therapies in septic patients. Consequently, future clinical trials are essential to assess and evaluate the potential advantages of corporating LILRB2 inhibitors with conventional sepsis therapies, especially in patients with advanced-stage sepsis who exhibit profound immunosuppression.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

R.B. and J.G. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript. Data Availability No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethical approval

These procedures were approved by the ethics of Beijing Tsinghua Changgung Hospital, and the ethical number was 25120-0-01.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mewes C, Runzheimer J, Böhnke C, et al. Association of sex differences with mortality and organ dysfunction in patients with Sepsis and septic shock. J Pers Med. 2023;13(5):836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu Z, Chambers S, Zeng Y, Bhatia M. Gases in sepsis: novel mediators and therapeutic targets. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(7):3669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torres LK, Pickkers P, van der Poll T. Sepsis-Induced immunosuppression. Annu Rev Physiol. 2022;84:157–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fu X, Liu Z, Wang Y. Advances in the study of immunosuppressive mechanisms in Sepsis. J Inflamm Res. 2023;16:3967–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Z, Wang Z. The role of macrophages polarization in sepsis-induced acute lung injury. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1209438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeung ST, Ovando LJ, Russo AJ, Rathinam VA, Khanna KM. CD169 + macrophage intrinsic IL-10 production regulates immune homeostasis during sepsis. Cell Rep. 2023;42(3):112171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar V. Targeting macrophage immunometabolism: dawn in the darkness of sepsis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;58:173–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biswas SK, Lopez-Collazo E. Endotoxin tolerance: new mechanisms, molecules and clinical significance. Trends Immunol. 2009;30(10):475–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luan YY, Yao YM, Xiao XZ, Sheng ZY. Insights into the apoptotic death of immune cells in sepsis. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2015;35(1):17–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang P, Amarasinghe HE, Whalley JP, et al. Epigenomic analysis reveals a dynamic and context-specific macrophage enhancer landscape associated with innate immune activation and tolerance. Genome Biol. 2022;23(1):136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patoli D, Mignotte F, Deckert V, et al. Inhibition of mitophagy drives macrophage activation and antibacterial defense during sepsis. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(11):5858–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He H, Zhang W, Jiang L, Tong X, Zheng Y, Xia Z. Endothelial cell dysfunction due to molecules secreted by macrophages in Sepsis. Biomolecules. 2024;14(8):980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen HM, van der Touw W, Wang YS, et al. Blocking Immunoinhibitory receptor LILRB2 reprograms tumor-associated myeloid cells and promotes antitumor immunity. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(12):5647–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang Z, Huang Q, Chang Y, et al. LILRB2 promotes immune escape in breast cancer cells via enhanced HLA-A degradation. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 2024;47(5):1679–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venet F, Schilling J, Cazalis MA, et al. Modulation of LILRB2 protein and mRNA expressions in septic shock patients and after ex vivo lipopolysaccharide stimulation. Hum Immunol. 2017;78(5–6):441–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baffari E, Fiume D, Caiazzo G, et al. Upregulation of the inhibitory receptor ILT4 in monocytes from septic patients. Hum Immunol. 2013;74(10):1244–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang W, He J. Interleukin-6 is a key factor for immunoglobulin-like transcript-4-mediated immune injury in sepsis. J Intensive Care. 2018;6:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radakovics K, Battin C, Leitner J, et al. A highly sensitive Cell-Based TLR reporter platform for the specific detection of bacterial TLR ligands. Front Immunol. 2021;12:817604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wen Q, Zhan B, Jin L, et al. Chlojaponilactone B attenuates THP-1 macrophage pyroptosis by inhibiting the TLR/MyD88/NF-κB pathway. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024;17(3):402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei H, Wu S, Mai L, Yang L, Zou W, Peng H. Cbl-b negatively regulates TLR/MyD88-mediated anti-Toxoplasma gondii immunity. Microbiol Spectr. 2023;11(6):e0007423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ai M, Lin S, Zhang M, et al. Cirsilineol attenuates LPS-induced inflammation in both in vivo and in vitro models via inhibiting TLR-4/NFkB/IKK signaling pathway. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2021;35(8):e22799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsujimoto H, Ono S, Efron PA, Scumpia PO, Moldawer LL, Mochizuki H. Role of Toll-like receptors in the development of sepsis. Shock 2008 29(3): 315–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Solomon LA, Li SK, Piskorz J, Xu LS, DeKoter RP. Genome-wide comparison of PU.1 and Spi-B binding sites in a mouse B lymphoma cell line. BMC Genomics. 2015;16(1):76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu J, Li S, Xiong D, et al. Screening of potential core genes in peripheral blood of adult patients with sepsis based on transcription regulation function. Shock. 2023;59(3):385–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin L, Jiang M, Qian J, Ge Z, Xu F, Liao W. The role of lipoprotein–associated phospholipase A2 in inflammatory response and macrophage infiltration in sepsis and the regulatory mechanisms. Funct Integr Genomics. 2024;24(5):178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai K, Song C, Gao M, et al. Uridine alleviates Sepsis-Induced acute lung injury by inhibiting ferroptosis of macrophage. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(6):5093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pietrzak J, Gronkowska K, Robaszkiewicz A. PARP traps rescue the Pro-Inflammatory response of human macrophages in the in vitro model of LPS-Induced tolerance. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2021;14(2):170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song R, Gao Y, Dozmorov I, et al. IRF1 governs the differential interferon-stimulated gene responses in human monocytes and macrophages by regulating chromatin accessibility. Cell Rep. 2021;34(12):108891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang R, Li Q, Wu P, et al. Fe-Capsaicin nanozymes attenuate Sepsis-Induced acute lung injury via NF-κB signaling. Int J Nanomed. 2024;19:73–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang C, Zeng J, Li LJ, Xue M, He SL. Cdc25A inhibits autophagy-mediated ferroptosis by upregulating ErbB2 through PKM2 dephosphorylation in cervical cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(11):1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang Y, Han Q, Zhao H, Zhang J. Promotion of epithelial-mesenchymal transformation by hepatocellular carcinoma-educated macrophages through Wnt2b/β-catenin/c-Myc signaling and reprogramming Glycolysis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2021;40(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boonmee A, Benjaskulluecha S, Kueanjinda P, Wongprom B, Pattarakankul T, Palaga T. The chemotherapeutic drug carboplatin affects macrophage responses to LPS and LPS tolerance via epigenetic modifications. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):21574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nwasike C, Purr E, Nagi JS, Mahler GJ, Doiron AL. Incorporation of targeting biomolecule improves interpolymer Complex-Superparamagnetic Iron oxide nanoparticles attachment to and activation of T(2) MR signals in M2 macrophages. Int J Nanomed. 2023;18:473–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Umiker B, Hashambhoy-Ramsay Y, Smith J, et al. Inhibition of LILRB2 by a novel blocking antibody designed to reprogram immunosuppressive macrophages to drive T-Cell activation in tumors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2023;22(4):471–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szklarczyk D, Kirsch R, Koutrouli M, et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(D1):D638–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang Y, Csakai A, Jiang S, et al. Tetrasubstituted imidazoles as incognito Toll-like receptor 8 a(nta)gonists. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):4351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nilsen KE, Skjesol A, Frengen Kojen J, Espevik T, Stenvik J, Yurchenko M. TIRAP/Mal positively regulates TLR8-Mediated signaling via IRF5 in human cells. Biomedicines. 2022;10(7):1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ignatz-Hoover JJ, Wang H, Moreton SA, et al. The role of TLR8 signaling in acute myeloid leukemia differentiation. Leukemia. 2015;29(4):918–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ondee T, Gillen J, Visitchanakun P, et al. Lipocalin-2 (Lcn-2) attenuates polymicrobial Sepsis with LPS preconditioning (LPS Tolerance) in FcGRIIb deficient lupus mice. Cells. 2019;8(9):1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tian J, Ashique AM, Weeks S, et al. ILT2 and ILT4 drive myeloid suppression via both overlapping and distinct mechanisms. Cancer Immunol Res. 2024;12(5):592–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wen X, Xie B, Yuan S, Zhang J. The Self-Sacrifice of immunecells in Sepsis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:833479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matsumoto H, Ogura H, Shimizu K, et al. The clinical importance of a cytokine network in the acute phase of sepsis. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):13995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brinkhoff A, Sieberichs A, Engler H, et al. Pro-Inflammatory Th1 and Th17 cells are suppressed during human experimental endotoxemia whereas Anti-Inflammatory IL-10 producing T-Cells are unaffected. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lorente-Sorolla C, Garcia-Gomez A, Català-Moll F, et al. Inflammatory cytokines and organ dysfunction associate with the aberrant DNA methylome of monocytes in sepsis. Genome Med. 2019;11(1):66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.López-Collazo E, del Fresno C. Pathophysiology of endotoxin tolerance: mechanisms and clinical consequences. Crit Care. 2013;17(6):242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Porta C, Rimoldi M, Raes G, et al. Tolerance and M2 (alternative) macrophage polarization are related processes orchestrated by p50 nuclear factor kappab. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(35):14978–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.LaFavers K. Disruption of kidney-Immune system crosstalk in Sepsis with acute kidney injury: lessons learned from animal models and their application to human health. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deng M, Chen H, Liu X, et al. Leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor subfamily B: therapeutic targets in cancer. Antib Ther. 2021;4(1):16–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Touw W, Chen HM, Pan PY, Chen SH. LILRB receptor-mediated regulation of myeloid cell maturation and function. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66(8):1079–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Louche CD, Roghanian A. Human inhibitory leukocyte Ig-like receptors: from immunotolerance to immunotherapy. JCI Insight. 2022;7(2):e151553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bhatnagar A, Chopra U, Raja S, et al. TLR-mediated aggresome-like induced structures comprise antimicrobial peptides and attenuate intracellular bacterial survival. Mol Biol Cell. 2024;35(3):ar34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rumpel N, Riechert G, Schumann J. miRNA-Mediated fine regulation of TLR-Induced M1 polarization. Cells. 2024;13(8):701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moen SH, Ehrnström B, Kojen JF, et al. Human Toll-like receptor 8 (TLR8) is an important sensor of pyogenic bacteria, and is attenuated by cell surface TLR signaling. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crémet L, Leroy AG, Muller D, et al. Antibiotic resistance heterogeneity and LasR diversity within Pseudomonas aeruginosa populations from pneumonia in intensive care unit patients. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2021;57(6):106341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thuy DB, Campbell J, Thuy CT, et al. Colonization with Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniae causes infections in a Vietnamese intensive care unit. Microb Genom. 2021;7(2):000514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krüger A, Oldenburg M, Chebrolu C, et al. Human TLR8 senses UR/URR motifs in bacterial and mitochondrial RNA. EMBO Rep. 2015;16(12):1656–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lyroni K, Patsalos A, Daskalaki MG, et al. Epigenetic and transcriptional regulation of IRAK-M expression in macrophages. J Immunol. 2017;198(3):1297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lu MQ, Xu LM, Huang Y, Chen YP, Li J, Wang XD. [The study on the role of SOCS1 and SOCS3 in the livers of endotoxin tolerance rats]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2008;88(37):2652–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Feng H, Wang T, Ye J, et al. SPI1 is a prognostic biomarker of immune infiltration and immunotherapy efficacy in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Discov Oncol. 2022;13(1):134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rothenberg EV, Hosokawa H, Ungerbäck J. Mechanisms of action of hematopoietic transcription factor PU.1 in initiation of T-Cell development. Front Immunol. 2019;10:228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zakrzewska A, Cui C, Stockhammer OW, Benard EL, Spaink HP, Meijer AH. Macrophage-specific gene functions in Spi1-directed innate immunity. Blood. 2010;116(3):e1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu T, Wen Z, Shao L, et al. ATF4 knockdown in macrophage impairs Glycolysis and mediates immune tolerance by targeting HK2 and HIF-1α ubiquitination in sepsis. Clin Immunol. 2023;254:109698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen X, Gao A, Zhang F, et al. ILT4 Inhibition prevents TAM- and dysfunctional T cell-mediated immunosuppression and enhances the efficacy of anti-PD-L1 therapy in NSCLC with EGFR activation. Theranostics. 2021;11(7):3392–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nishiyama S, Hirose N, Yanoshita M et al. ANGPTL2 induces synovial inflammation via LILRB2. inflammation. 2021. 44(3): 1108–18. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.