Abstract

Background

As a prevalent result of recurrent ankle sprains, chronic ankle instability (CAI) leads to persistent discomfort, impaired function, and mechanical instability. While ankle arthroscopic surgery effectively restores joint stability, its impact on psychological well-being remains uncertain. Patients with CAI frequently experience anxiety and depression, potentially influencing postoperative outcomes. The objective of this study was to examine improvements in anxiety and depression symptoms after arthroscopic anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) repair and analyze the connection between preoperative mental health and surgical outcomes.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study included 60 patients who underwent arthroscopic ATFL repair for CAI. The Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) and Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) were utilized for psychological assessments preoperatively and postoperatively. The Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) score were employed to evaluate pain levels and functional recovery. Based on preoperative psychological status, patients were divided into two groups: Group A, comprising those with anxiety or depression, and Group B, consisting of those without. The impact of preoperative mental health on postoperative outcomes was analyzed statistically.

Results

Out of the 60 enrolled patients, 56 completed follow-up assessments. Preoperative anxiety and depression were present in 38% of patients (Group A). Both groups exhibited notable postoperative improvements in SAS, SDS, AOFAS, and VAS scores postoperatively (p < 0.05). However, Group A exhibited a less favorable prognosis, with lower improvements in pain relief, functional recovery, and psychological well-being compared to Group B. A strong association between higher preoperative pain scores and increased anxiety was observed in the correlation analysis. In contrast, lower ankle function scores were linked to higher depression levels. Preoperative anxiety showed a strong correlation with disease duration, while older individuals exhibited higher levels of preoperative depression.

Conclusion

Arthroscopic ATFL repair significantly improved psychological well-being, functional outcomes, and pain levels in CAI patients. Nevertheless, the adverse impact of preoperative anxiety and depression on recovery emphasized the importance of incorporating mental health evaluations and psychological support into treatment strategies. Optimizing postoperative recovery in CAI patients requires a holistic, interdisciplinary strategy that incorporates both physical and psychological considerations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13018-025-06039-w.

Keywords: Chronic ankle instability, Anxiety, Depression, Ankle arthroscopy, Prognosis, Psychological well-being, Functional recovery

Introduction

Chronic ankle instability (CAI) is a prevalent and enduring sports injury from ankle sprains. It manifests as recurrent sprains and ankle joint’s mechanical impairment, resulting in pain, swelling, weakness, and restricted movement [1–3]. CAI leads to ankle dysfunction, movement limitations, and other symptoms that severely impact patients’ quality of life [4]. Ankle arthroscopic surgery has emerged as an effective treatment for CAI, repairing ligament injuries, enhancing ankle joint stability, and improving patient outcomes [5–8]. However, individuals with CAI, particularly those necessitating surgical intervention, often experience significant psychological distress, including mood disorders like depression and anxiety.

Mental health is closely associated with physical well-being. Individuals with CAI may experience depression and anxiety due to persistent pain, dysfunction, and fear of re-injury, which can impact their quality of life, rehabilitation progress, and ability to return to sports activities [9]. These negative psychological states may reduce patients’ confidence in surgery and impede their adherence to postoperative rehabilitation. Although existing research suggests CAI patients experience greater anxiety and depression than healthy individuals [10], further research is needed to examine psychological changes before and after arthroscopic anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) repair.

This investigation sought to examine the improvement of depression and anxiety symptoms and the prognosis of CAI patients following arthroscopic ATFL repair. By examining pre- and postoperative levels of depression and anxiety, healthcare providers can better address the mental well-being of CAI patients, customize treatment plans accordingly, and ultimately improve surgical outcomes and overall patient well-being.

Methods and materials

Patients

This retrospective cohort study utilized prospectively collected data, with participants primarily drawn from Jingzhou Hospital Affiliated with Yangtze University. The study included patients who received initial arthroscopic ATFL repair for CAI between September 2021 and September 2023. Inclusion criteria were: (1) recurrent ankle sprains and clinical instability, confirmed by positive anterior drawer and talar tilt stress fluoroscopy; (2) failure to improve after > 3 months of conservative management; and (3) a confirmed anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) lesion visualized on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasonography (US)[11, 12]. Exclusion criteria included: (1) History of psychiatric conditions or undergoing psychiatric treatment; (2) Presence of other significant medical conditions that could impact study results; (3) Severe postoperative complications, including infections necessitating reoperation and complex regional pain syndrome, precluded complete follow-up. The Medical Ethics Committee of Jingzhou Hospital, Affiliated with Yangtze University, approved this study, which adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent during hospitalization for potential future research use of their anonymized data. For follow-up assessments, verbal consent was obtained via WeChat(Tencent, Shenzhen, China) or telephone prior to questionnaire administration.

Research methodology

Patients were contacted via WeChat or telephone for in-person questionnaire completion. The ZUNG Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) was employed [13], consisting of 20 items with a 4-point scoring system. Scores below 50 indicated no anxiety, while 50–60, 60–70, and ≥ 70 denoted mild, moderate, and severe anxiety, respectively. The Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) [13] consisted of 20 items, with scores categorized as follows: mild depression (53–62), moderate depression (63–72), and severe depression (≥ 73). Pain intensity was assessed using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) [14], which ranges from 0 to 10, where 0 indicates no pain, ≤ 3 represents mild pain, 4–6 signifies moderate but tolerable pain, and 7–10 corresponds to severe pain affecting sleep and appetite. The American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) score [6] assessed ankle function on a 100-point scale, with scores of ≥ 90–100 considered excellent, 80-<89 good, 70-<79 fair, and < 70 poor. For analysis of psychological status in relation to recovery outcomes, patients were assigned to either Group A (presenting with preoperative anxiety or depression symptoms) or Group B (No such symptoms were observed preoperatively). Postoperatively, all patients were guided through a structured rehabilitation program.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis utilized SPSS 26.0 software, presenting measurement data as mean ± standard deviation. Changes in SAS, SDS, VAS, and AOFAS scores pre- and post-operation were evaluated through paired sample t-tests. Pearson correlation analysis and independent sample t-tests were conducted to evaluate the connections between disease duration, age, preoperative pain, ankle function, psychological condition, and postoperative progress in the anxiety/depression group. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Result

General characteristics of the patients

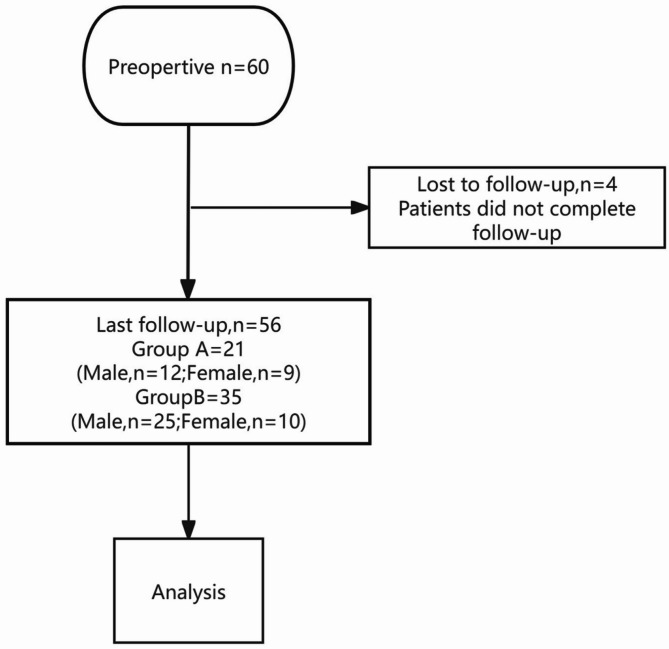

Among the 60 qualified patients enrolled in the study, 56 completed the questionnaire. The participant group comprised 37 males and 19 females (Fig. 1). The study cohort had a mean age of 28.96 ± 4.87 years, with a mean follow-up duration of 11.54 ± 0.74 months (minimum 10 months) and an average disease course of 16.93 ± 2.66 months. Among the participants, 21 (38%) experienced preoperative anxiety or depression, with 12 being male and 9 female. The remaining 35 patients (62%) showed no preoperative anxiety/depression symptoms, with 25 males and 10 females in this group. Age, disease duration, and follow-up period showed no significant statistical variations between the groups (Table 1). The same physician consistently performed the ATFL repair during the same surgical procedure for both groups.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart for patient enrollment and follow-up

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study patients

| Evaluation indicators | Group A (n = 21) | Median | Range | Group B (n = 35) | Median | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 27.98 ± 5.17 | 27 | 20–37 | 29.57 ± 4.65 | 28 | 21–40 |

|

Sex(n%) Male Female |

12(57.1) 9(42.9) |

- | - |

25(71.4) 10(28.6) |

- | - |

|

Injury side(n%) Left Right |

8(38.1) 13(61.9) |

- | - |

16(45.7) 19(54.3) |

- | - |

| Duration of illness (months) | 17.66 ± 2.54 | 18 | 14–24 | 16.49 ± 2.67 | 18 | 16–22 |

| follow-up time (months) | 11.57 ± 0.68 | 12 | 10–12 | 11.51 ± 0.78 | 12 | 11–12 |

| SAS (preop) | 55.90 ± 4.39 | 55 | 51–62 | 42.31 ± 2.79 | 42 | 36–47 |

| SDS (preop) | 60.19 ± 6.76 | 58 | 53–75 | 42.80 ± 3.28 | 42 | 39–47 |

Comparison of preoperative and final follow-up assessment indicators

Fifty-six patients were followed up for an average of 11.54 ± 0.74 months, with no incidences of wound infection, joint instability, or walking function limitations observed in either group during this period. Physical examinations yielded negative results for the drawer test and varus stress test. Group A exhibited a significant improvement in all scores post-surgery compared to preoperative scores (P < 0.05, Table 2), with the SAS score decreasing from 55.90 ± 4.39 to 35.19 ± 4.27, the SDS score decreasing from 60.19 ± 6.76 to 40.76 ± 3.22, the VAS score decreasing from 5.48 ± 0.75 preoperatively to 2.10 ± 0.54 postoperatively, and the AOFAS score increasing from 49.71 ± 6.11 preoperatively to 85.57 ± 1.75 postoperatively.

Table 2.

Assessment of preoperative and final follow-up indicators in group A patients

| Evaluation indicators | VAS | AOFAS | SAS | SDS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| preoperative | 5.48 ± 0.75 | 49.71 ± 6.11 | 55.90 ± 4.39 | 60.19 ± 6.76 |

| final follow-up | 2.10 ± 0.54 | 85.57 ± 1.75 | 35.19 ± 4.27 | 40.76 ± 3.22 |

| P value | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 |

In group B, the SAS score decreased significantly from 45.31 ± 2.79 to 33.69 ± 1.64, and the SDS score decreased from 42.80 ± 3.28 to 35.54 ± 1.24. The VAS score also notably decreased from 4.37 ± 0.55 preoperatively to 1.43 ± 0.50 postoperatively. Moreover, the AOFAS score showed a substantial rise from 53.29 ± 5.22 before surgery to 92.74 ± 3.09 after surgery. In Group B, these findings indicate notable postoperative advancements in mental health, pain alleviation, and ankle functionality relative to pre-surgical assessments (P < 0.05, Table 3).

Table 3.

Assessment of preoperative and final follow-up indicators in group B patients

| Evaluation indicators | VAS | AOFAS | SAS | SDS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| preoperative | 4.37 ± 0.55 | 53.29 ± 5.22 | 42.31 ± 2.79 | 42.80 ± 3.28 |

| final follow-up | 1.43 ± 0.50 | 92.74 ± 3.09 | 33.69 ± 1.64 | 35.54 ± 1.24 |

| P value | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 |

Correlation analysis of psychological status

Postoperative score analysis showed that prognostic outcomes were significantly worse in Group A compared to Group B (P < 0.05, Table 4). Furthermore, preoperative VAS scores were notably higher in Group A (P < 0.05), whereas preoperative AOFAS scores were comparable across both groups (P > 0.05, Table 5). Within Group A, correlation analysis identified a significant link between preoperative VAS scores and anxiety levels (P < 0.05), while no association was found with depression levels (P > 0.05). Additionally, preoperative AOFAS scores showed a significant association with preoperative depression levels (P < 0.05) but were not correlated with anxiety levels (P > 0.05). Illness duration was significantly related to preoperative anxiety levels (P < 0.05) but showed no correlation with preoperative depression levels (P > 0.05, Table 6). Age did not significantly correlate with preoperative anxiety levels (P > 0.05) but exhibited a significant relationship with preoperative depression levels (P < 0.05, Table 6). Additionally, preoperative anxiety and depression did not significantly impact postoperative improvements in VAS, AOFAS, SAS, or SDS scores (all P > 0.05, Table 7).

Table 4.

Analysis of the correlation between psychological status and patient prognosis

| Evaluation indicators | VAS | AOFAS | SAS | SDS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t value | 8.14 | -8.11 | 2.95 | 8.25 |

| P value | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.05 |

Table 5.

Association between psychological state and preoperative VAS and AOFAS scores

| Evaluation indicators | VAS | AOFAS |

|---|---|---|

| t value | 9.02 | -1.65 |

| P value | P < 0.05 | P > 0.05 |

Table 6.

Correlation between age, disease duration, VAS, and AOFAS scores with preoperative psychological condition in group A patients

| Evaluation indicators | SAS | SDS |

|---|---|---|

|

VAS r value P value |

0.88 P < 0.05 |

-0.07 P > 0.05 |

|

AOFAS r value P value |

-0.12 P > 0.05 |

0.85 P < 0.05 |

|

Age r value P value |

0.04 P > 0.05 |

0.97 P < 0.05 |

|

Duration of illness r value P value |

0.96 P < 0.05 |

-0.09 P > 0.05 |

Table 7.

Analysis of the impact of preoperative psychological status on postoperative recovery in group A patients

| Evaluation indicators | SAS(preop) | SDS(preop) |

|---|---|---|

|

VAS r value P value |

-0.29 P > 0.05 |

0.27 P > 0.05 |

|

AOFAS r value P value |

-0.01 P > 0.05 |

-0.22 P > 0.05 |

|

SAS r value P value |

0.05 P > 0.05 |

0.19 P > 0.05 |

|

SDS r value P value |

-0.19 P > 0.05 |

-0.01 P > 0.05 |

Discussion

In this study, 56 patients underwent examination, revealing that 38% presented with poor preoperative psychological status. This research confirmed a significant link between psychological factors and postoperative outcomes in CAI patients treated with arthroscopic ATFL repair. Patients exhibiting preoperative anxiety or depression symptoms displayed poorer recovery in pain, functional activity, and psychological well-being compared to those without such symptoms. The study indicates that surgical intervention may positively impact pre-existing anxiety and depression. However, Group A patients exhibited a worse prognosis than Group B, highlighting the complex relationship between surgical outcomes and pre-existing mental health conditions [15, 16]. While surgery effectively addressed the primary physical concern, persistent psychological distress may have impeded overall functional outcomes in Group A, suggesting that a solely physical intervention may not adequately meet the needs of this patient cohort.

This study demonstrated a significant association between preoperative VAS scores and anxiety levels among patients in Group A. This suggests that individuals with higher levels of pain also experience elevated preoperative anxiety, aligning with findings from previous research [17–19]. Foot pain negatively influences quality of life by impairing mobility, affecting balance, and increasing fall susceptibility [20, 21]. Studies suggest that people experiencing foot pain are more prone to anxiety and depression than those without such discomfort [22]. Effectively managing preoperative pain through analgesic medication or other interventions may help reduce patients’ preoperative anxiety levels and enhance their psychological well-being before surgery [23].

In Group A patients, preoperative AOFAS scores showed a significant correlation with preoperative depression levels. The AOFAS score indicates ankle function, with lower scores indicating more severe ankle dysfunction. The study results suggest that patients with more severe ankle dysfunction tend to have higher levels of preoperative depression. This association may be influenced by factors such as the chronic nature of joint disease, limitations in daily life due to functional impairment, and changes in social roles, which can contribute to negative emotions and an increased risk of depression in patients [24, 25]. Therefore, conducting a comprehensive functional assessment of patients before surgery and developing a tailored rehabilitation plan based on their functional status can improve both ankle function and psychological well-being.

Surgical intervention alone has been shown to improve the mental well-being of patients with comorbid musculoskeletal pain and depression/anxiety, as indicated by previous research demonstrating enhanced depression and anxiety scores postoperatively [26, 27]. In our study, both patient groups undergoing arthroscopic repair of the ATFL for CAI exhibited significant improvements in AOFAS and VAS scores. Psychological assessments post-surgery revealed notable enhancements in SAS and SDS scores compared to preoperative evaluations. No cases of wound infection, joint instability, or ambulatory limitations were reported in either cohort. Furthermore, physical examinations yielded negative results for the drawer and varus stress tests.

The study demonstrated a notable association between the duration of illness and preoperative anxiety levels, suggesting that prolonged illness is associated with increased anxiety. This correlation may arise from concerns about disease prognosis resulting from long-term illness, compounded by factors such as reduced quality of life and limited social support, thereby intensifying anxiety [28–30].

A notable correlation was identified between age and preoperative depression levels, suggesting that increased age is linked to higher depression severity. This relationship may be attributed to factors such as physiological decline, changes in social roles, and alterations in social support systems, all of which could elevate the risk of depression in patients [25]. Despite the correlation between psychological status and prognosis, preoperative anxiety and depression do not significantly impact postoperative progress. Thus, incorporating psychological assessments into clinical practice is vital for optimizing personalized treatment plans [31].

This study highlights the importance of psychological factors in the recovery after arthroscopic repair of ATFL. By identifying high-risk patients, making personalized treatment plans, and strengthening doctor-patient communication, patients can be helped to better cope with postoperative challenges, improve prognosis, and improve quality of life. Therefore, clinicians should pay full attention to the psychological state of patients and take corresponding intervention measures when treating ATFL injury.

The research examined the effectiveness of ankle arthroscopic ATFL repair for CAI and investigated the potential link between patients’ psychological health and postoperative recovery. However, the study’s small sample size of 56 patients limited the ability to comprehensively account for all influencing factors. Furthermore, since this study was conducted retrospectively in a tertiary grade A hospital, its applicability to patients in different healthcare settings remains unclear. The short duration of follow-up in this study means that we were able to observe patients’ recovery for a limited time, and we were unable to assess the effect of the procedure on their long-term mental health and functional recovery.To gain deeper insight into the relationship between psychological status and clinical outcomes following arthroscopic ATFL repair for CAI, a large-scale, multicenter, randomized controlled trial with extended follow-up is required to examine additional factors influencing patient prognosis.

Conclusion

This research highlights the role of preoperative anxiety and depression in shaping postoperative outcomes following arthroscopic ATFL repair for CAI, suggesting a detrimental association between these psychological factors and prognosis. Anxiety and depression are also linked to preoperative pain, function, disease duration, and patient age. Despite these challenges, group A showed significant short-term improvement post-surgery. These results underscore the importance of integrating psychosocial factors into orthopedic care to improve long-term patient outcomes.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- VAS

visual analogue scale

- AOFAS

American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society

- SAS

Self-Rating Anxiety Scale

- SDS

Self-Rating Depression Scale

- CAI

Chronic ankle instability

- ATFL

anterior talofibular ligament

Author contributions

Songlin Liu performed the data collection and data analysis and wrote the paper; Liang Ma conceived, designed, performed the experiments and revised the paper. All authors reviewed the results and finalized the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Jingzhou Science and Technology Program (2024HD12).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Consent for publication

All patients provided written informed consent for the publication of their identifying photographs.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jingzhou Hospital of Yangtze University. All patients signed a consent form for surgery. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ferran NA, Oliva F, Maffulli N. Ankle instability. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2009;17(2):139–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Azevedo Sodré Silva A, Sassi LB, Martins TB, de Menezes FS, Migliorini F, Maffulli N, Okubo R. Epidemiology of injuries in young volleyball athletes: a systematic review. J Orthop Surg Res. 2023;18(1):748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferran NA, Maffulli N. Epidemiology of sprains of the lateral ankle ligament complex. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11(3):659–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bridgman SA, Clement D, Downing A, Walley G, Phair I, Maffulli N. Population based epidemiology of ankle sprains attending accident and emergency units in the West Midlands of england, and a survey of UK practice for severe ankle sprains. Emerg Med J. 2003;20(6):508–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng SM, Maffulli N, Ma C, Oliva F. All-inside arthroscopic modified Broström-Gould procedure for chronic lateral ankle instability with and without anterior talofibular ligament remnant repair produced similar functional results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021;29(8):2453–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nery C, Raduan F, Del Buono A, Asaumi ID, Cohen M, Maffulli N. Arthroscopic-assisted Broström-Gould for chronic ankle instability: a long-term follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(11):2381–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aicale R, Maffulli N. Chronic lateral ankle instability: topical review. Foot Ankle Int. 2020;41(12):1571–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allegra F, Boustany SE, Cerza F, Spiezia F, Maffulli N. Arthroscopic anterior talofibular ligament reconstructin in chronic ankle instability: two years results. Injury. 2020;51(Suppl 3):S56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holt M, Swalwell CL, Silveira GH, Tippett V, Walsh TP, Platt SR. Pain catastrophising, body mass index and depressive symptoms are associated with pain severity in tertiary referral orthopaedic foot/ankle patients. J Foot Ankle Res. 2022;15(1):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakagawa R, Yamaguchi S, Kimura S, et al. Association of anxiety and depression with pain and quality of life in patients with chronic foot and ankle diseases. Foot Ankle Int. 2017;38(11):1192–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qin J, Fu Q, Zhou Q, et al. Fully Intra-articular Lasso-Loop stitch technique for arthroscopic anterior talofibular ligament repair. Foot Ankle Int. 2022;43(3):439–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thès A, Odagiri H, Elkaïm M, et al. Arthroscopic classification of chronic anterior talo-fibular ligament lesions in chronic ankle instability. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2018;104(8S):S207–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971 Nov-Dec;12(6):371–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Myles PS. The pain visual analog scale: linear or nonlinear? Anesthesiology. 2004;100(3):744–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cunningham DJ, Steele JR, Allen NB, Nunley JA, Adams SB. The impact of preoperative mental health and depression on outcomes after total ankle arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2021;103(2):131–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vissers MM, Bussmann JB, Verhaar JA, Busschbach JJ, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Reijman M. Psychological factors affecting the outcome of total hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41(4):576–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shivarathre DG, Howard N, Krishna S, Cowan C, Platt SR. Psychological factors and personality traits associated with patients in chronic foot and ankle pain. Foot Ankle Int. 2014;35(11):1103–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cotchett M, Munteanu SE, Landorf KB. Depression, anxiety, and stress in people with and without plantar heel pain. Foot Ankle Int. 2016;37(8):816–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nixon DC, Schafer KA, Cusworth B, McCormick JJ, Johnson JE, Klein SE. Preoperative anxiety effect on Patient-Reported outcomes following foot and ankle surgery. Foot Ankle Int. 2019;40(9):1007–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menz HB, Auhl M, Spink MJ. Foot problems as a risk factor for falls in community-dwelling older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas. 2018;118:7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menz HB, Morris ME, Lord SR. Foot and ankle characteristics associated with impaired balance and functional ability in older people. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(12):1546–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cotchett M, Frescos N, Whittaker GA, Bonanno DR. Psychological factors associated with foot and ankle pain: a mixed methods systematic review. J Foot Ankle Res. 2022;15(1):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan MIH, Sawyer BJ, Akins NS, Le HV. A systematic review on the kappa opioid receptor and its ligands: new directions for the treatment of pain, anxiety, depression, and drug abuse. Eur J Med Chem. 2022;243:114785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakagawa R, Yamaguchi S, Kimura S, Sadamasu A, Yamamoto Y, Sato Y, Akagi R, Sasho T, Ohtori S. Association of anxiety and depression with pain and quality of life in patients with chronic foot and ankle diseases. Foot Ankle Int. 2017;38(11):1192–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao S, Zan Q, Lu J, Li Y, Li B, Zhao H, Wang T, Xu J. Analysis of preoperative and postoperative depression and anxiety in patients with osteochondral lesions of the talus. Front Psychiatry. 2024;15:1356856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fehring TK, Odum SM, Curtin BM, Mason JB, Fehring KA, Springer BD. Should depression be treated before lower extremity arthroplasty?? J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(10):3143–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park C, Garcia AN, Cook C, Gottfried ON. Effect of change in preoperative depression/anxiety on patient outcomes following lumbar spine surgery. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;199:106312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sorel JC, Veltman ES, Honig A, Poolman RW. The influence of preoperative psychological distress on pain and function after total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone Joint J. 2019;101–B(1):7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keefe FJ, Somers TJ. Psychological approaches to Understanding and treating arthritis pain. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6(4):210–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edwards RR, Haythornthwaite JA, Smith MT, Klick B, Katz JN. Catastrophizing and depressive symptoms as prospective predictors of outcomes following total knee replacement. Pain Res Manag. 2009 Jul-Aug;14(4):307–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Löbner M, Luppa M, Matschinger H, Konnopka A, Meisel HJ, Günther L, Meixensberger J, Angermeyer MC, König HH, Riedel-Heller SG. The course of depression and anxiety in patients undergoing disc surgery: a longitudinal observational study. J Psychosom Res. 2012;72(3):185–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.