Abstract

Background and Objectives

Amisulpride is a second-generation antipsychotic drug that selectively binds to D2 and D3 dopaminergic receptors in the limbic system. In this study, the bioequivalence of an amisulpride formulation manufactured in China with the original formulation Solian® was evaluated under fasting and fed conditions in healthy Chinese subjects.

Methods

A single-centre, randomized, open, two-preparation, single-dose, two-period crossover trial in healthy adult subjects was conducted under fasting and fed conditions. A total of 42 and 36 eligible healthy subjects were enrolled in the fasting and fed studies, respectively. The subjects were randomly assigned to receive either the test or the reference formulation with a washout period of 7 days. The concentration of amisulpride in plasma was determined by liquid chromatography‒tandem mass spectrometry (LC‒MS/MS), and the pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters of amisulpride were calculated via the noncompartmental method.

Results

The geometric mean ratios (GMR) of the maximum observed concentration (Cmax), the area under the plasma concentration‒time curve (AUC) from time zero to the last sampling time (AUC0–t), and the AUC from time zero to infinity (AUC0–∞) from the test/reference formulation under fasting conditions were 93.83, 101.90, and 102.35, respectively, with corresponding 90% confidence intervals (CIs) of 83.93–104.89, 97.58–106.42, and 98.24–106.63. The GMRs of Cmax, AUC0–t, and AUC0–∞ under fed conditions were 102.23, 106.09, and 101.87, respectively, with corresponding 90% CIs of 92.49–112.99, 102.44–109.87, and 97.49–106.44. These data all satisfied the bioequivalence criteria (90% CIs in the range of 80–125%). In terms of safety, no serious adverse events were observed.

Conclusions

The test and reference amisulpride formulations were bioequivalent under fasting and fed conditions. Both formulations showed similar safety and tolerability in the population studied.

Key Points

| Both test and reference formulations of amisulpride were bioequivalent under fasting and fed conditions in healthy Chinese subjects. |

| Both test and reference formulations of amisulpride were well tolerated and safe. |

Introduction

According to a survey by the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 970 million people worldwide suffered from mental disorders in 2019, 82% of whom were from middle- and low-income countries [1]. Schizophrenia is a severe, chronic mental disorder that affects the way a person thinks, feels and behaves and may lead to cognitive impairment and social difficulties. Studies have shown that the life expectancy of people with schizophrenia is 10–20 years less than that of the general population, with serious consequences for patients and their families [2]. From 1990 to 2019, the raw prevalence (14.2–23.6 million), incidence (941,000–1.3 million), and disability-adjusted life-years (9.1–15.1 million) for schizophrenia increased by more than 65%, 37%, and 65%, respectively [3]. Currently, the number of people with schizophrenia in China is approximately 7 million, and the number is increasing [4].

Amisulpride is a second-generation antipsychotic drug that selectively binds to D2 and D3 dopaminergic receptors in the limbic system, thereby modulating neurotransmitter levels for the treatment of psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression [5]. Amisulpride may cause a range of adverse effects, including insomnia, allergic reactions and abnormally high prolactin levels. However, amisulpride is associated with a significantly lower risk of adverse extrapyramidal reactions than other antipsychotic medications [6]. Amisulpride is rapidly absorbed after oral administration, with an absolute bioavailability of 50% and a maximum concentration (Tmax) of 1–4 h; moreover, amisulpride reaches steady-state concentrations after 2–3 days of continuous administration. The drug is widely distributed in the body, with a volume of distribution of approximately 5.8 L/kg and a relatively low plasma protein binding rate of approximately 17% [7]. Therefore, amisulpride rarely interacts with alcohol or other drugs and has a high safety profile, which also gives it a unique advantage in the treatment of patients with schizophrenia with substance abuse disorders [8]. The renal clearance rate of amisulpride is 17–20 L/h, and approximately 22–25% of the oral dose is excreted in the urine as the original drug form [7].

Findings from multiple studies suggest that amisulpride is a suitable first-line treatment option for patients with first-episode and relapsing schizophrenia [9]. Importantly, different doses of amisulpride are required for patients with different effective therapeutic doses. The effective therapeutic dose for patients with recurrent negative symptoms is usually 400–600 mg/d. For patients with positive symptoms, the initial dose is 200–400 mg/d, which is gradually increased to 600–1200 mg/d within a week and then tapered according to efficacy and tolerability [10]. In patients with renal insufficiency, the half-life of amisulpride remains unchanged, but systemic clearance is reduced by one third, and attention is required to adjust the administered dose [11]. Studies have shown that there is a large interindividual variation in amisulpride plasma concentrations, with age and sex having a significant effect on amisulpride blood concentrations [12]. Amisulpride blood levels are greater in elderly and female patients than in male patients, which may be due to sex differences in the renal clearance of the drug. In addition, the combination of lithium and clozapine may also increase amisulpride blood concentrations [13].

In January 1986, the original amisulpride formulation Solian® (Licensee: SANOFI-AVENTIS FRANCE) was first approved for marketing in France. In this study, we evaluated the bioequivalence of the test amisulpride formulation (Licensee: Fujian Baonuo Pharmaceutical R&D Co.) and the reference formulation Solian® in healthy subjects under fasting and fed conditions. According to the equivalence criteria, if the 90% confidence intervals (CIs) of the maximum observed concentration (Cmax) and area under the plasma concentration‒time curve (AUC) of the test formulation are both within the range of 80.00~125.00% of the corresponding parameters of the reference formulation, then it may be concluded that the two formations are bioequivalent. Moreover, the safety of these two formulations was evaluated in healthy Chinese subjects.

Materials and Methods

Research Design

This study was a single-centre, randomized, open, two-preparation, single-dose, two-period crossover trial with healthy adult subjects. Approval from the ethics committee at Wuhan Pulmonary Hospital was obtained prior to the commencement of the study. The trial was registered at the Drug trial Registration and Information Publishing platform in China (www.chinadrugtrials.org.cn: CTR20211003). All the subjects provided informed consent prior to the start of the trial. The guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and related regulatory requirements were strictly followed during the trial.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Wuhan Pulmonary Hospital (approval number 2021-061-01).

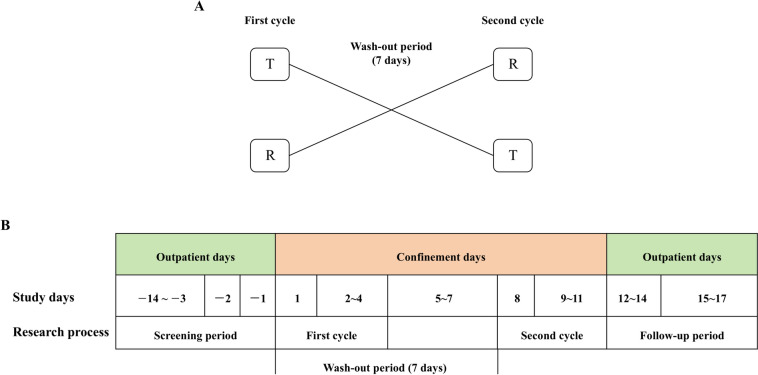

In the fasting and fed study, we assumed that α = 0.05, β = 0.2, and θ = 0.90. The coefficient of variation (CV) was 18.52%. Using these values, the lowest estimated sample size was 32 subjects. Considering that the fasting group was more likely to drop out than the fed group, 42 subjects were enrolled in the fasting test, and 36 subjects were enrolled in the fed test. The subjects were randomly assigned by SAS (9.4) at a 1:1 ratio to either the test formulation (T)-reference formulation (R) group (T-R group) or the R-T group. All the subjects were checked in at the clinical trial centre 2 days before drug administration. The subjects fasted after dinner for at least 10 h 1 day before administration. On the day of administration, for the fasting group, the subjects took either the test or the reference formulation (0.2 g) orally with 240 mL of warm water, and for the fed group, the subjects consumed a high-fat meal within 30 min prior to administration. The high-fat meal had a total of approximately 900 kcal, of which protein provided approximately 150 kcal, carbohydrates approximately 250 kcal, and fat approximately 500–600 kcal. All the subjects were prohibited from drinking water for 1 h, fasted for 4 h after dosing, and allowed to eat standard meals for approximately 4 h and 10 h after dosing. After the 7-day washout period in the clinical trial centre, cross-dosing was performed, and the procedure for the second cycle was the same as that for the first cycle (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The experimental procedure of the study; A study flow chart; B group of drugs administered

Subjects

Before the start of the trial, all potential participants were informed in detail about the possible benefits of the trial as well as the possible inconveniences and potential dangers and voluntarily signed an informed consent form. The participants were then subjected to a series of screening procedures, including the collection of demographic information, past medical history questioning, physical examination, vital sign testing, laboratory tests, electrocardiograms, chest X-rays, and alcohol content testing. Healthy Chinese men and women aged 18–65 years were included in this study, with body weights ≥ 50 kg for men and ≥ 45 kg for women and body mass indices (BMIs) in the range of 19–27 kg/m2. Participants who met the criteria after the researchers combined and evaluated the results of all tests were enrolled in the clinical trial.

Individuals who had participated in a clinical trial of another drug or engaged in smoking or alcohol abuse within the past 3 months were not included in the study. In addition, individuals who had used any medicines that interact with the amisulpride formulations or affect hepatic drug-metabolizing enzymes within 30 days prior to the trial and who had taken any medicines or supplements in the 14 days prior to the trial were excluded from the study. The enrolled subjects were not allergic to amisulpride. Pregnant or lactating women were not allowed to participate in the study.

Blood Sample Collection and Analysis Methods

At different time points before and after dosing, the investigators collected 4 mL of venous blood from the upper extremity of the subjects into EDTA-K2 anticoagulated vacuum blood collection tubes and gently inverted it six times to mix the blood with the anticoagulant (Table 1). Blood samples were centrifuged at 1700 × g for 10 min. At the end of centrifugation, the upper plasma layer was dispensed into two freezing tubes, one for the assay (volume at least 0.8 mL) and one for backup. The time of placing blood samples in a −20 °C freezer or directly in a −80 °C freezer from collection to plasma separation was controlled within 100 min (not more than 120 min). Temporary storage at −20 °C did not exceed 24 h. For long-term storage, samples were placed in a −80 °C freezer.

Table 1.

Blood collection time points

| Fasting | Fed | Allowable deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Within 1 h prior to dosing | Before a high-fat meal within 1 h before administration | – |

| 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.33, 1.67, 2, 2.33, 2.67, 3, 3.33, 3.67, 4, 4.33, 4.67, 5, 5.5, 6, 6.5, 7, 8 h after administration | 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.33, 1.67, 2, 2.33, 2.67, 3, 3.33, 3.67, 4, 4.33, 4.67, 5, 5.33, 5.67, 6, 6.5, 7, 7.5, 8 h after administration | ± 1 min |

| 10, 12 h after administration | 10, 12 h after administration | ± 3 min |

| 24, 48, 72 h after administration | 24, 48, 72 h after administration | ± 10 min |

A validated liquid chromatography‒tandem mass spectrometry (LC‒MS/MS) method was used to determine the concentration of amisulpride in the plasma of the subjects after dosing. Amisulpride-d5 was used as the internal standard. The sample (1 μL) was injected via an autosampler and separated on a Capcell PAK ADME column (2.1 × 100 mm, inner diameter (i.d.) 5 μm), with a mobile phase of (A) 0.1% formic acid–10 mM ammonium acetate in water and (B) 0.1% formic acid–10 mM ammonium acetate in methanol. The flow rate was 0.500 mL/min, and the temperature of the column was maintained at 40 °C. The mass spectrometry parameters were configured as follows: ionization was achieved via electrospray ionization (ESI) in positive ion mode, with data acquisition performed in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM). The optimized ion source conditions were as follows: TEM, 650 °C; GS1, 35 psi; GS2, 45 psi; and CAD, 8 units. Amisulpride quality control (QC) samples were validated at six concentration levels: Lower Limit of Quantification QC (LLOQ QC, 3.00 ng/mL), Low QC (LQC, 9.00 ng/mL), Medium QC1 (MQC1, 120 ng/mL), Medium QC2 (MQC2, 400 ng/mL), High QC (HQC, 1,200 ng/mL), and Dilution QC (DQC, 3,000 ng/mL). These samples were analysed across three independent batches. As summarized in Table 2, all the results met the predefined acceptance criteria (±15% deviation for accuracy and ≤ 15% relative standard deviation (RSD) for precision, except ± 20% at the LLOQ). A seven-point calibration curve for amisulpride was constructed at concentrations of 3.000, 6.000, 15.00, 60.00, 300.0, 750.0, and 1500 ng/mL. All six independent calibration curves demonstrated excellent linearity (r2 > 0.999) across the validated range of 3.000–1500 ng/mL.

Table 2.

Precision and accuracy analysis of the quality control samples

| Precision and accuracy | Maximum of precision (RSD %) | Average accuracy deviation (%) range |

|---|---|---|

| Intrabatch (all concentrations except LLOQ) | 2.66 | − 7.24 to 1.94 |

| Intrabatch (LLOQ) | 3.29 | − 2.76 to − 0.52 |

| Interbatch (all concentrations except LLOQ) | 4.58 | − 5.79 to − 2.21 |

| Interbatch(LLOQ) | 2.65 | − 1.65 |

Study Endpoints

AUC0–t, the AUC from time zero to infinity (AUC0–∞) and the Cmax were the primary endpoints of the study, whereas the secondary endpoints were the Tmax, apparent terminal half-life (t½), AUC from the time to the last quantifiable concentration extrapolated to infinity expressed as a percentage of AUC0–∞ (AUCextra%) and terminal elimination rate constant (λz). Safety evaluation indicators included adverse events/serious adverse events, clinical symptoms, vital signs, physical examination findings, laboratory test results, and 12-lead electrocardiogram findings. Vital signs (including body temperature, pulse and blood pressure) were measured within 1 h before administration and at 4.0 ± 0.5 h, 24.0 ± 0.5 h, 48.0 ± 1.0 h, and 72.0 ± 1.0 h after administration. Adverse events (AEs) were monitored throughout the study. The data manager used MedDRA 23.0 to medically code the adverse events. Adverse events were graded in accordance with the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0, which is a system used to evaluate the causal relevance of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and classify it into six levels: positive, probable, possible, probably irrelevant, to be evaluated, and unable to be evaluated.

Statistical Analysis

For the PK analysis, we used data from all subjects with at least one evaluable PK parameter of interest in at least one treatment period. Phoenix WinNonlin software (version 7.0) was used to calculate pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters via a nonatrioventricular model. Statistical data are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SDs). The PK parameters evaluated included the Cmax, Tmax, t½, λz, AUC0–t, and AUC0–∞. For the bioequivalence analysis, subjects who received at least one dosing cycle and had at least one evaluable pharmacokinetic parameter were included. According to the bioequivalence evaluation criteria, a two-sided one-tailed t-test and 90% confidence interval method were used to assess whether the two formulations of amisulpride were bioequivalent. Two formulations were considered bioequivalent if the 90% CIs of the GMRs of their main PK parameters (Cmax, AUC0–t and AUC0–∞) were within a predefined acceptable range of 80–125%.

Cmax, AUC0–t and AUC0–∞ required logarithmic conversion, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied for significance testing. The administration sequence, period and formulation were treated as fixed effects in the ANOVA model, and subject (sequence) was treated as a random effect. On the basis of the results of the statistical analysis, in the ANOVA for random-effects models, total variation was broken down into sequential variation, periodic variation and drug formulation variation to analyse the effect of differences on equivalence evaluation. Differences were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05. For the safety and tolerability analyses, all subjects who received the study formulations and who had safety records were included. SAS (version 9.4) software was used for the statistical analysis of the safety variables.

Results

Subject Characteristics

A total of 102 subjects were screened in the fasting group, and 86 subjects were screened in the fed group. After a series of screening processes, 42 subjects (including 31 males and 11 females) were successfully enrolled in the fasting group, and 36 subjects (including 27 males and 9 females) were successfully enrolled in the fed group. No subjects withdrew during the trial period, and all collected data were included in the final analysis. The detailed characteristics of the participants can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of the eligible subjects

| Fasting | Fed | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-T group | T-R group | R-T group | T-R group | |

| N | 21 | 21 | 18 | 18 |

| Age, years | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 26.0 (5.1) | 26.4 (4.6) | 27.1 (6.6) | 26.8 (5.7) |

| Min, max | 20, 38 | 19, 36 | 18, 39 | 18, 33 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 18 (85.7) | 13 (61.9) | 13 (72.2) | 14 (77.8) |

| Female | 3 (14.3) | 8 (38.1) | 5 (27.8) | 4 (22.2) |

| Height, cm | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 167.9 (8.9) | 169.2 (7.0) | 168.3 (7.6) | 169.3 (7.5) |

| Min, max | 150.5, 185.0 | 154.0, 179.5 | 155.5, 182.5 | 153.5, 182.5 |

| Weight, kg | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 63.7 (8.7) | 62.2 (8.9) | 62.6 (7.3) | 63.4 (8.1) |

| Min, max | 47.9, 81.6 | 46.0, 80.7 | 47.5, 81.0 | 46.7, 75.4 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 22.6 (2.2) | 21.6 (1.0) | 22.1 (1.9) | 22.1 (2.0) |

| Min, max | 19.17, 26.42 | 19.39, 25.49 | 19.15, 24.94 | 19.37, 25.46 |

T test formulation, R reference formulation, N number, SD standard deviation, Min minimum, Max maximum, BMI body mass index

Pharmacokinetic Analysis

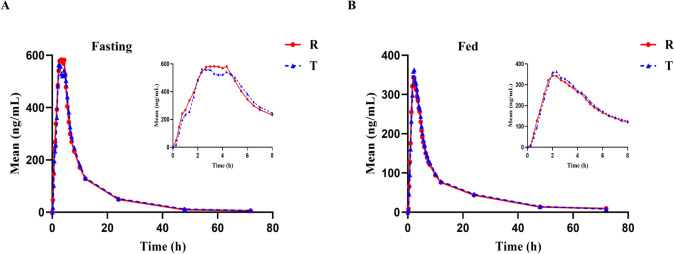

The mean plasma concentration‒time profiles of the test and reference formulations after a single dose are shown in Fig. 2. The test and reference formulations could be absorbed rapidly in healthy Chinese subjects under these two conditions. In addition, the peak times and metabolic processes of the two formulations were similar. The PK parameters for amisulpride for the test and reference drugs under fasting and fed conditions are presented in Table 4. ANOVA revealed that there were no significant differences (P > 0.05) in the dosing sequence, formulation effect or period effect of amisulpride under fasting conditions. However, under the fed condition, there was a significant difference (P < 0.05) in the formulation effect on AUC0–t and a significant difference (P < 0.05) in the period effect on Cmax (Table 5).

Fig. 2.

The mean plasma concentration–time profiles of the test and reference formulations after a single dose; A fasting group; B fed group

Table 4.

PK parameters for amisulpride under fasting and fed conditions

| Mean ± SD (CV%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting | Fed | |||

| T | R | T | R | |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 873.12 ± 383.44 (43.92) | 942.68 ± 437.31 (46.39) | 441.01 ± 181.4 (41.13) | 435.15 ± 182.24 (41.88) |

| AUC0–t (h*ng/mL) | 5734.29 ± 1557.22 (27.16) | 5652.44 ± 1537.95 (27.21) | 3697.40 ± 1125.18 (30.43) | 3508.20 ± 1072.53 (30.57) |

| AUC0–∞ (h*ng/mL) | 5867.13 ± 1541.41 (26.27) | 5762.74 ± 1541.20 (26.74) | 3908.81 ± 1181.54 (30.23) | 3832.17 ± 1098.20 (28.66) |

| Tmax (h)a | 3.83 (1.67, 5.50) | 3.17 (0.75, 5.00) | 3.00 (1.00, 4.67) | 2.33 (0.75, 5.00) |

| t½ (h) | 10.57 ± 3.86 (36.48) | 9.70 ± 3.79 (39.07) | 13.93 ± 6.80 (48.80) | 15.06 ± 8.20 (54.49) |

| λz | 0.07 ± 0.03 (38.11) | 0.08 ± 0.03 (33.19) | 0.06 ± 0.02 (35.33) | 0.06 ± 0.02 (38.50) |

T test formulation, R reference formulation, SD standard deviation, CV coefficient of variation, Cmax maximum concentration, AUC0–t the area under the plasma concentration‒time curve from 0 h to the time of the last measurable concentration, AUC0–∞ the area under the plasma concentration‒time curve from 0 h to infinity, Tmax time to reach maximum concentration, t½ apparent terminal half-life, λz terminal elimination rate

aPresented as the median (minimum, maximum)

Table 5.

Statistical analysis P-values of the effects of the dosing sequence, formulation and period

| P-values | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| LnCmax | LnAUC0–t | LnAUC0–∞ | |

| Fasting | |||

| Dosing sequence | 0.4383 | 0.1305 | 0.1480 |

| Formulation | 0.3415 | 0.4679 | 0.3459 |

| Period | 0.3443 | 0.7818 | 0.7199 |

| Fed | |||

| Dosing sequence | 0.7174 | 0.3324 | 0.2398 |

| Formulation | 0.7120 | 0.0073 | 0.4809 |

| Period | 0.0002 | 0.0530 | 0.1472 |

Cmax maximum concentration, AUC0–t the area under the plasma concentration‒time curve from 0 h to the time of the last measurable concentration, AUC0–∞ the area under the plasma concentration‒time curve from 0 h to infinity

Bioequivalence Analysis

The bioequivalence assessment and analysis of the main PK parameters were performed. The geometric mean ratio (GMR) was used for the bioequivalence evaluation, and the results are presented in Table 6. In the fasting study, compared with the reference formulation, the Cmax, AUC0–t and AUC0–∞ of amisulpride in the test formulation were 93.83, 101.90 and 102.35%, respectively. The 90% CIs for the Cmax, AUC0–t and AUC0–∞ all fell within the bioequivalence range of 80–125% and thereby met the bioequivalence criteria. In the fed study, compared with those of the reference formulation, the Cmax, AUC0–t and AUC0–∞ of amisulpride in the test formulation were 102.23, 106.09 and 101.87%, respectively. The 90% CIs of the GMRs of AUC0–t and AUC0–∞ of the test and reference formulations were in the range of 80–125% and thereby met the bioequivalence criteria.

Table 6.

Bioequivalence evaluation under fasting and fed conditions

| Geometric mean and ratio | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | R | Ratio (T/R, %) | 90% CIs | Power (%) | |

| Fasting | |||||

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 796.99 | 849.44 | 93.83 | 83.93~104.89 | 76.03 |

| AUC0–t (h*ng/mL) | 5500.85 | 5398.06 | 101.90 | 97.58~106.42 | 100.00 |

| AUC0–∞ (h*ng/mL) | 5640.20 | 5510.74 | 102.35 | 98.24~106.63 | 100.00 |

| Fed | |||||

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 408.21 | 399.31 | 102.23 | 92.49~112.99 | 94.61 |

| AUC0–t (h*ng/mL) | 3472.44 | 3273.09 | 106.09 | 102.44~109.87 | 100.00 |

| AUC0–∞ (h*ng/mL) | 3675.27 | 3607.93 | 101.87 | 97.49~106.44 | 100.00 |

T test formulation, R reference formulation, CI confidence interval, Cmax maximum concentration, AUC0–t the area under the plasma concentration‒time curve from 0 h to the time of the last measurable concentration, AUC0–∞ the area under the plasma concentration‒time curve from 0 h to infinity

Safety Analysis

In the fasting study, the data included in the safety evaluation were based on data from 42 subjects in the safety analysis set. A total of four subjects experienced adverse events (AEs); the AE rate was 9.5% (4/42). There were five mild adverse reactions, three in the T-formulation group and two in the R-formulation group, but there were no adverse drug reactions (ADRs). In the fed study, the safety evaluation data were based on data from 36 subjects in the safety analysis set. A total of five subjects experienced AEs; the AE rate was 13.9% (5/36), and a total of six AEs occurred, three in the T-formulation group and three in the R-formulation group. One AE in the T-formulation group was classified as possibly related to the drug, and five AEs were classified as probably unrelated to the drug. Notably, all adverse events observed in this study were of mild severity, and all affected patients recovered from these AEs (Table 7).

Table 7.

Adverse events in each system classified by drug category

| T | R | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Times | Number | Rate (%) | Times | Number | Rate (%) | |

| Fasting (N = 42) | ||||||

| Positive urine leukocytes | 1 | 1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Elevated blood creatine phosphokinase | 1 | 1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Elevated blood uric acid | 1 | 1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Bellyache | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1 | 2.4 |

| Diarrhoea | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1 | 2.4 |

| Fed (N = 36) | ||||||

| Lowered white blood cell count | 1 | 1 | 2.8 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Elevated arm pulse | 1 | 1 | 2.8 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 1 | 1 | 2.8 | 2 | 2 | 5.6 |

| Sore throat | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1 | 2.8 |

T test formulation, R reference formulation, N number

Discussion

Treatment for schizophrenia usually includes medication, psychotherapy and social support. Amisulpride is an aniline-substituted psychotropic sedative that selectively binds to D2 and D3 dopamine receptors in the limbic system [8]. A high dose of amisulpride primarily blocks dopaminergic neurons in the middle of the limbic system, which may account for the greater psychoinhibitory than extrapyramidal effects of amisulpride. Low-dose amisulpride primarily blocks presynaptic D2/D3 dopaminergic receptors, which could explain its effect on negative symptoms [14]. Amisulpride is predominantly eliminated via renal excretion with minimal reliance on hepatic enzyme-mediated metabolism, and existing clinical evidence has not supported significant ethnic variability in the pharmacokinetic profile of amisulpride. Our study offers actionable guidance for clinicians in other countries.

Bioequivalence evaluation of drugs ensures that generic drugs are comparable to originator drugs in terms of efficacy and safety, which is essential for promoting the rational use of drugs and reducing healthcare costs. According to the guidelines for bioequivalence studies, AUC0–t and AUC0–∞ reflect the total exposure of a drug over a period of time, whereas Cmax reflects the rate and extent of absorption of a drug; all of these parameters are primary and important parameters in the evaluation of pharmacokinetics. Under fasting and fed conditions, the trends of the mean plasma concentration‒time profiles of the test and reference formulations were consistent, and the Cmax, AUC0–t, AUC0–∞ and 90% CI were all between 80.00% and 125.00%, meeting the acceptance criteria for bioequivalence. The Tmax, t½ and λz were similar for the test and reference formulations in both the fasting and fed studies, suggesting that there was no significant difference in absorption between the two formulations. These results indicated that the test formulation and the reference formulation are equivalent in the peak concentration, degree of absorption and degree of metabolism.

Amisulpride is rapidly absorbed after oral administration, reaching a first peak at approximately 1.5 h and then a second peak at 3–4 h [15]. In this study, we found two peaks in the fasting group, which may be due to hepatoenteric circulation. Notably, this phenomenon was not observed in the fed group. Compared with those of the fasting group, the Tmax, Cmax, AUC0–t and AUC0–∞ of the fed group were lower, indicating that the high-fat diet accelerated the absorption rate of amisulpride and reduced its absorption degree and drug exposure. Although gastric contents typically delay gastric emptying and prolong Tmax [16], high-fat diets can stimulate bile secretion, whereby bile salts may increase the intestinal dissolution and permeation of amisulpride by emulsifying effects, enabling partial rapid absorption and a shortened Tmax [17]. Furthermore, lipid components in food may restrict drug dissolution through physical adsorption or complex formation, concurrently altering the gastrointestinal pH and mucosal layer properties, ultimately diminishing the overall absorption efficiency, as evidenced by the reduced Cmax and AUC [18]. Therefore, for populations with a high-fat dietary culture (e.g., Western countries), it is recommended to adhere to a fasting administration regimen to mitigate food-mediated absorption-inhibitory effects.

AEs that occurred in this study included urine leukocyte positivity, elevated blood creatine phosphokinase levels, elevated blood uric acid levels, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, lowered white blood cell counts, an elevated arm pulse, upper respiratory tract infection and sore throat, all of which have been reported in previous studies [19]. Safety evaluations indicated that all AEs were mild and that affected participants recovered without special intervention, implying that amisulpride was generally safe, acceptable and well tolerated in the fasting and fed studies. In addition, there was no significant difference in the rate of AEs between the test and reference drug groups under fasting or fed conditions.

This study has several limitations that warrant acknowledgement. First, the investigation was conducted with a limited sample size confined to healthy Chinese adult subjects, resulting in insufficient statistical power for safety data analyses and caution in extrapolating findings to psychiatric patients. Second, the single-dose design precluded a comprehensive evaluation of the PK parameters of amisulpride under various dosage regimens or long-term safety profiles. Furthermore, standardized dietary protocols, while minimizing interindividual variability, may not fully replicate real-world clinical scenarios, potentially limiting the generalizability of the results. Notably, the effects of food on amisulpride pharmacokinetics, such as the influence of meal composition or dosing-meal intervals, were not specifically addressed in this study, and further exploration through crossover or food intervention trials is needed. In future investigations, expanded sample sizes and the inclusion of heterogeneous populations (e.g., patients with schizophrenia) should be prioritized to enable multidose, multicycle monitoring for a holistic assessment of the PK/pharmacodynamic (PD) characteristics and safety thresholds of the formulation in complex pathophysiological conditions.

Conclusions

An amisulpride formulation (0.2 g) held by Fujian Baonuo Pharmaceutical R&D Co. was equivalent to the reference formulation (Solian®, 0.2 g) after a single oral dose under fasting/fed conditions in healthy Chinese subjects, and the safety profile was favourable, with only mild adverse effects being observed. The findings of this study are very relevant for patients suffering from schizophrenia, as it expands their choices.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the content of this article.

Funding Statement

This study was sponsored and funded by Fujian Baonuo Pharmaceutical R&D Co.

Ethics Approval

All the protocol and documents were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Wuhan Pulmonary Hospital (no. 2021005). This study was registered at the Drug Clinical Trial Registration and Information Publicity Platform (http://www.chinadrugtrials.org.cn/index.html) with registration no. CTR20211003.

Consent to Participate

All study participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for Publication

All researchers, participants, institutions and sponsors consented to the submission of this report to the journal.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

W.M. took responsibility for writing the manuscript and contributed to the pharmacokinetic analysis as well as data interpretation. P.Y. was responsible for the management of drugs in the study and manuscript submission. Y.H.G. participated in quality control throughout the study. P.Z.X. was involved in the management of biological samples. D.R.H. and L.G. were responsible for the conception and design of the study, data analysis and revision of the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Ronghui Du, Email: 2782044387@qq.com.

Guan Liu, Email: liuguantbdoctor@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(2):137–50. 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laursen TM, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB. Excess early mortality in schizophrenia. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:425–48. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Solmi M, Seitidis G, Mavridis D, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and global burden of schizophrenia - Data, with critical appraisal, from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019. Mol Psychiatry. 2023;28(12):5319–27. 10.1038/s41380-023-02138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu YH, Lu Q. Prevalence, risk factors and multiple outcomes of treatment delay in Chinese patients with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):748. 10.1186/s12888-023-05247-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krause M, Zhu Y, Huhn M, et al. Antipsychotic drugs for patients with schizophrenia and predominant or prominent negative symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;268(7):625–39. 10.1007/s00406-018-0869-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hadryś T, Rymaszewska J. Amisulpride – Is it as all other medicines or is it different? An update. Amisulpryd – Lek taki sam jak wszystkie czy inny? Aktualizacja. Psychiatr Pol. 2020;54(5):977–89. 10.12740/PP/OnlineFirst/109129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mauri MC, Paletta S, Di Pace C, et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics of atypical antipsychotics: an update. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2018;57(12):1493–528. 10.1007/s40262-018-0664-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Komossa K, Rummel-Kluge C, Hunger H, et al. Amisulpride versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2010(1):CD006624. 10.1002/14651858.CD006624.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Psarros C, Theleritis CG, Paparrigopoulos TJ, Politis AM, Papadimitriou GN. Amisulpride for the treatment of very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(5):518–22. 10.1002/gps.2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Psarros C, Theleritis CG, Paparrigopoulos TJ, Politis AM, Papadimitriou GN. Amisulpride for the treatment of very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(5):518–22. 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00375-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun F, Yu F, Gao Z, Ren Z, Jin W. Study on the relationship among dose, concentration and clinical response in Chinese schizophrenic patients treated with Amisulpride. Asian J Psychiatr. 2021;62: 102694. 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mauri MC, Paletta S, Maffini M, et al. Clinical pharmacology of atypical antipsychotics: an update. EXCLI J. 2014;13:1163–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergemann N, Kopitz J, Kress KR, Frick A. Plasma amisulpride levels in schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004;14(3):245–50. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li L, Li L, Shang DW, Wen YG, Ning YP. A systematic review and combined meta-analysis of concentration of oral amisulpride. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;86(4):668–78. 10.1111/bcp.14246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jang YJ, Jeong TC, Noh K, et al. Prandial effect on the systemic exposure of amisulpride. Arch Pharm Res. 2014;37(10):1325–8. 10.1007/s12272-014-0331-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yun HY, Joo Lee E, Youn Chung S, et al. The effects of food on the bioavailability of fenofibrate administered orally in healthy volunteers via sustained-release capsule. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2006;45(4):425–32. 10.2165/00003088-200645040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rohr MW, Narasimhulu CA, Rudeski-Rohr TA, Parthasarathy S. Negative effects of a high-fat diet on intestinal permeability: a review. Adv Nutr. 2020;11(1):77–91. 10.1093/advances/nmz061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koziolek M, Alcaro S, Augustijns P, et al. The mechanisms of pharmacokinetic food-drug interactions—a perspective from the UNGAP group. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2019;134:31–59. 10.1016/j.ejps.2019.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao Y, Su J. Bioequivalence of 200 mg amisulpride tablets in healthy Chinese volunteers under fasting and fed conditions. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2024;13(1):32–6. 10.1002/cpdd.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.