Abstract

Progressing from acute kidney injury (AKI) to chronic kidney disease (CKD) is acknowledged as a significant clinical challenge. Our recent works indicated that PR domain-containing 16 (PRDM16) impedes the progression of AKI and DKD. Nonetheless, the specific function and regulatory mechanism of PRDM16 during the AKI to CKD transition remain incompletely understood. In this investigation, it was identified that PRDM16 mitigates TGF-β1-induced renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis in BUMPT cells. From a mechanistic perspective, PRDM16 was found to enhance the expression of eif6, which subsequently suppressed TGF-β, CTGF, and NLRP3 levels via the suppression of the Wnt/β-catenin/SP1 signaling cascade. Additionally, knock-in of PRDM16 in kidney proximal tubules resulted in increased expression of eIF6, thereby restraining the stimulation of the Wnt/β-catenin/SP1 pathway, reducing the production of TGF-β, CTGF, and NLRP3, and consequently limiting renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis progression in both unilateral ureteral obstruction and ischemia–reperfusion-injury mouse models.Moreover, overexpression of PRDM16 following ischemia-induced AKI was shown to attenuate renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis and the eIF6/Wnt/β-catenin/SP1/TGF-β, CTGF, and NLRP3 axis. Finally, the PRDM16/eIF6/Wnt/β-catenin/SP1/TGF-β, CTGF, and NLRP3 axis were analyzed in renal biopsies from individuals with minimal change disease and severe obstructive nephropathy. Collectively, these findings indicate that PRDM16-mediated eIF6 induction serves to impede the transition from AKI to CKD by suppressing the Wnt/β-catenin/SP1/TGF-β, CTGF, and NLRP3 axis.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00018-025-05766-x.

Keywords: AKI, PRDM16, CKD, eIF6

Introduction

The homeostasis of the kidneys played a pivotal role in adjustment of normal physiological function [1, 2]. Therefore, once the homeostasis of the kidneys is disrupted, kidney function impairment can lead to development of AKI and CKD [3–6]. While dialysis has been employed as a treatment strategy for severe acute kidney injury (AKI), the morbidity and mortality rates associated with AKI continue to remain elevated [7, 8]. Moreover, AKI presents a considerable threat to the later onset of chronic kidney disease (CKD), and effective methods to halt the transition from AKI to CKD remain elusive [9–11]. Various mediators have been linked to the advancement from AKI to CKD [10, 12, 13]. Among these, renal tubular epithelial cells (TECs) are crucial contributors to this process [14, 15]. Damaged TECs contribute to tubulointerstitial fibrosis and CKD progression by producing a range of fibrogenic factors, including TGF-β, CTGF, and NLRP3 [16–21]. The above data suggested that imbalance of renal tubular homeostasis mediated the progression of AKI to CKD transition. Nevertheless, the specific regulatory mechanisms governing the production of multiple factors by injured TECs during the transition from AKI to CKD remain largely unexplored.

Certain research has suggested that the advancement of AKI to CKD is mediated by the involvement of HMGB1, HDAC3, NLRP3-NOD, and VNN1 in tubular cells [22–25]. However, both Elabela and SIK1 have been observed to exert opposite effects [26, 27]. PRD1-BF1-RIZ1 homologous domain-containing protein 16 (PRDM16) is recognized as a potent activator of beige adipocytes [28–32]. Our recent findings have demonstrated that PRDM16 contributes to reduced tubulointerstitial fibrosis in diabetic kidney disease (DKD) [33]. Furthermore, another study has also suggested that PRDM16 inhibits the progression of AKI induced by LPS, cisplatin, and ischemia [34, 35]. The above data suggested that PRDM16 could be considered as a homeostasis regulation factor. Nevertheless, the specific function and control mechanisms of tubular PRDM16 in the progression from AKI to CKD remain poorly understood.

In this investigation, it was observed that PRDM16 expression is elevated in unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) models. PRDM16 functions to suppress TGF-β1-induced renal fibrosis (RF). Mechanistically, PRDM16 acts by restraining the Wnt/β-catenin/SP1 signaling cascade via the upregulation of eif6, which consequently downregulates TGF-β, CTGF, and NLRP3 expression. Therefore, these observations indicate that PRDM16 plays an important role in maintaining renal homeostasis by inhibiting the transition of AKI to CKD, and its overexpression may represent a novel therapeutic strategy.

Methods

Antibodies and reagents

Anti-fibronectin (FN; ab2413), anti-PRDM16 (106410), anti-SP1 (ab227383), anti-Wnt (ab15251), anti-beta-Catenin (phospho) (ab314450), anti-beta-Catenin (non-phospho) (ab305261), anti-NLRP3 (ab263899), anti-IL-1β (ab283822), anti-CTGF (ab318348), anti-TGF-beta1 (ab229856), α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; 1 A4), and anti-Collagen I (ab138492) were procured from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). The anti-Collagen III antibody (22734–1-AP) was procured from Proteintech (Chicago, USA), and anti-beta-Tubulin (T0023) was provided by Affinity Biosciences (MA, USA). Anti-eIF6 (LL0223) was sourced from Zen-Bioscience (Chengdu, Sichuan province, China). Secondary antibodies were acquired from ThermoFisher Scientific (Massachusetts, MA, USA). Protein signals were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence assay kit (#180–5001, Tanon, Shanghai, China). The siRNAs targeting PRDM16 were produced by Ruibo Biology Company (Guangdong, Guangzhou, China). Doxycycline (DOX) was procured from the Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Cell propagation and TGFβ1 administration

BUMPT cells, an immortalized mouse proximal tubular cell line, were kept in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (Sigma-Aldrich, Missouri, MO, USA) comprising 1% penicillin‒streptomycin (Gibco, 15140163) and 10% fetal bovine serum, in an environment comprising 5% CO2 at 37 °C. When the cell density reached approximately 80—90% confluence, cells were passaged at a ratio of 1:3. That is, for every flask of cells at the appropriate confluence, the cells were trypsinized, and then the cell suspension was divided into three equal parts and seeded into three new flasks for further culture.Upon reaching roughly 70% confluence, they underwent serum starvation overnight and were then exposed to 5 ng/mL recombinant TGFβ1 (R&D Systems) for durations of 6, 12, and 24 h. This concentration was determined based on prior experimental findings [33, 36]. A cell line stably expressing PRDM16 was previously established, and detailed methods can be found in our earlier publication [33]. Additionally, when the cells attained around 50% confluence, transfection with PRDM16 and eIF6 siRNA was performed using Lipofectamine 2000.

Animal model

To validate the function of tubular PRDM16 in the progression from AKI to CKD, mouse models with proximal tubule-specific PRDM16 knockout and knock-in were developed. Detailed methodologies for mouse model construction and breeding strategies are available in a previous publication [33]. The UUO paradigm was implemented by obstructing the left ureter, as earlier outlined, with mice being euthanized on the seventh-day post-surgery [37, 38]. Ischemic renal damage was triggered by clamping both kidneys for 28 min, succeeded by a 28-day reperfusion interval [39]. All animals were kept on a 12-h alternating light and dark cycle with unimpeded availability of sustenance and hydration. This investigation received approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital, China (NO. 2018065 l).

Histological and immunohistochemical analyses

Renal tubular and glomerular tissue morphology, structure, and damage were assessed using Hematoxylin–eosin staining. The distribution and content of collagen fibers in renal tissues were evaluated through Masson staining. F4/80 staining was utilized to determine macrophage distribution and quantify changes within inflammatory regions, facilitating the analysis of inflammation’s extent and progression. Detailed procedures can be found in our previous publication [40]. Immunohistochemical assays were performed using anti-Col I (dilution 1:100), anti-Col III (dilution 1:100), anti-FN (dilution 1:50), anti-α-SMA (dilution 1:100), and anti-F4/80 (dilution 1:100) antibodies, following previously established protocols [33]. The stained samples were assessed with a UV epi-illumination microscope (Olympus).

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT‐qPCR)

Total RNA was procured from BUMPT cells or kidney tissue using Trizol reagent obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). The isolated RNA was subsequently reverse-transcribed into first-strand cDNA with the PrimeScript RT Reagent kit and gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa, catalog number RR037 A), according to protocols detailed in previous studies [33]. The synthesized cDNA was subsequently utilized as a template in a reaction containing TB Green (TaKaRa, catalog number RR820 A) on a LightCycler 96 system (Roche), with specific primer pairs employed for amplification. PRDM16: CAGCAACCTCCAGCGTCACATC (forward) and GCGAAGGTCTTGCCACAGTCAG (reverse); eIF6: GATTGGTGTGCTTTCTGTGGTCTG (forward) and GGTACTTGGCTTGGCTTCATTCAG (reverse). Relative quantification was performed using ΔΔCT values, while absolute quantification was based on a standard curve.

ChIP analysis

ChIP assays were conducted utilizing a ChIP kit obtained from Millipore (Boston, MA, USA). Anti-HA-tag and Anti-SP1 antibodies were employed to isolate DNA bound to proteins. Mouse IgG was employed as a control. The primer sequences utilized for ChIP are as follows: eIF6: CTGCCTAAATGAATGGCCACAG (forward) and TTCAGGGTGAGGTTGTGAGC (reverse); TGF-β: GCTGTGTTCATTGCTGTGTCC (forward) and GTTTCTAGTGGCCTCAATGCAC (reverse); CTGF: ATGTGGCTGGCTTAACAAGG (forward) and CGGCAAAGACTAATTTTGGAGAC (reverse); NLRP3: GAGGAGGCTCTGTCAATAATAGT (forward) and GCTGTCCTCTGACTTGTGCT (reverse).

Human samples

This research was granted authorization by the Review Board of the Second Xiangya Hospital, People’s Republic of China (No. Z1184-02). Kidney biopsy specimens were collected from paracancerous tissue (n = 6) and OB (n = 6), with informed consent obtained from all patients. The research affirms its adherence to applicable ethical standards for studies involving human subjects, complies with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and follows the directives provided by the Ministry of Science and Technology for the Review and Approval of Human Genetic Resources.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for peritumoral renal tissue as the control cohort for OB tissue:

Inclusion criteria: 1. Specimens must be obtained from the same surgical sample as the renal cancer tissue; 2. Pathological confirmation is required to establish the tissue as normal renal tissue; 3. Patients must not have undergone local treatment for the kidney prior to surgery nor received kidney radiotherapy; and 4. Age and gender must correspond to those of the patients with OB.

Exclusion criteria: Individuals with coexisting severe kidney diseases, serious systemic conditions, pregnancy or lactation, mental illness, cognitive impairment, or a recent history of major surgery or severe trauma are excluded.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for Minimal change disease and severe OB patients:

Inclusion criteria:

Present typical symptoms of nephrotic syndrome, namely massive proteinuria (24-h urinary protein quantification > 3.5 g in adults and > 50 mg/kg in children), hypoalbuminemia (plasma albumin < 30 g/L), severe edema and hyperlipidemia;Urine routine examination is mainly proteinuria, and serum creatinine and urea nitrogen are within the normal range or slightly elevated;Under light microscopy, glomeruli are basically normal, and fatty degeneration can be seen in proximal tubular epithelial cells.; age range between 18 and 75 years.

Severe OB patients: Urinary tract obstruction of confirmed etiology; substantial increase in serum creatinine levels (typically exceeding 2 times the upper limit of normal); significant decline in glomerular filtration rate (generally below 30 ml/min/1.73 m2); pronounced hydronephrosis (separation of renal collecting system greater than 3 cm); severe dilation of the ureter; age range between 18 and 75 years.

Exclusion criteria: Patients with other severe kidney diseases, serious systemic conditions, pregnancy or lactation, mental illness, cognitive impairment, or a recent history of major surgery or severe trauma are excluded.

Statistics

Data are denoted as means ± SD. Comparisons between two cohorts were executed utilizing two-tailed t-tests. For multiple cohort comparisons, one-way ANOVA was utilized. The Kruskal–Wallis test was employed for non-parametric comparisons among multiple cohorts. Statistical significance was established by a P-value below 0.05.

Study approval

All animal experimental procedures and protocols were approved by theInstitutional Ethics Committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital, China (NO. 2018065 l). Procedures involving specimens obtained from human subjects were performed according to a protocol approved (No. Z1184-02) by the Review Board of the Second Xiangya Hospital, People’s Republic of China.

Results

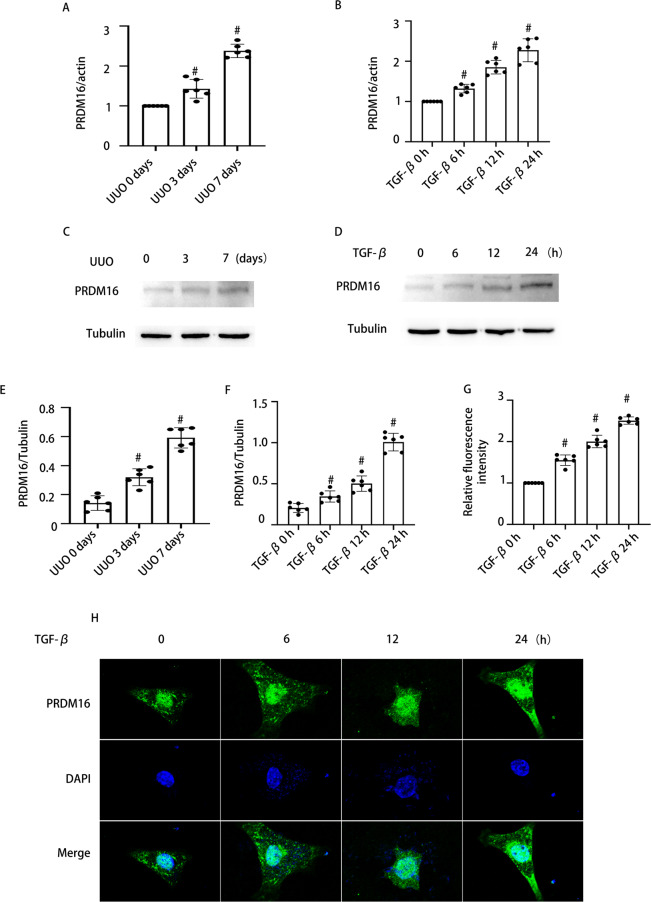

The expression of PRDM16 increased when treated with TGF-β1 in BUMPT cells and the kidneys of UUO mice

To confirm the upregulation of PRDM16 induced by TGF-β1 in BUMPT cells and UUO mouse kidneys, we first conducted an analysis. RT-qPCR results indicated a significant increase in PRDM16 mRNA levels post TGF-β1 treatment in both BUMPT cells and UUO mouse kidneys (Fig. 1A-B). Similarly, western blot (WB) demonstrated an elevated expression of PRDM16 at the protein level under the same conditions (Fig. 1C-F). Additionally, the relative fluorescence intensity analysis revealed that PRDM16 levels were progressively enhanced in BUMPT cells at 6, 12, and 24 h after TGF-β1 treatment (Fig. 1G-H). These outcomes highlight the possible involvement of PRDM16 in the process of RF.

Fig. 1.

Expression of PRDM16 exposed to TGF-β1 in BUMPT cells and the kidneys of UUO mice and individuals with OB. A-B The mRNA levels of PRDM16, as determined by RT-qPCR, in BUMPT cells with and without TGF-β stimulation, along with the renal tissue of UUO mice. C-D WB of PRDM16 and β-Tubulin in BUMPT cells subjected to TGF-β1 treatment or left untreated, as well as in kidney samples from UUO mice. E–F The grayscale analysis (GSY) between them. H Immunofluorescence examination to visualize PRDM16 expression and distribution in BUMPT cells. J Relative fluorescence intensity. Quantification of the PRDM16 -positive cells. Original magnification × 600. Scale bar: 20 µM. Data are denoted as the means ± SD (n = 6). #p < 0.05, vs. control cohort

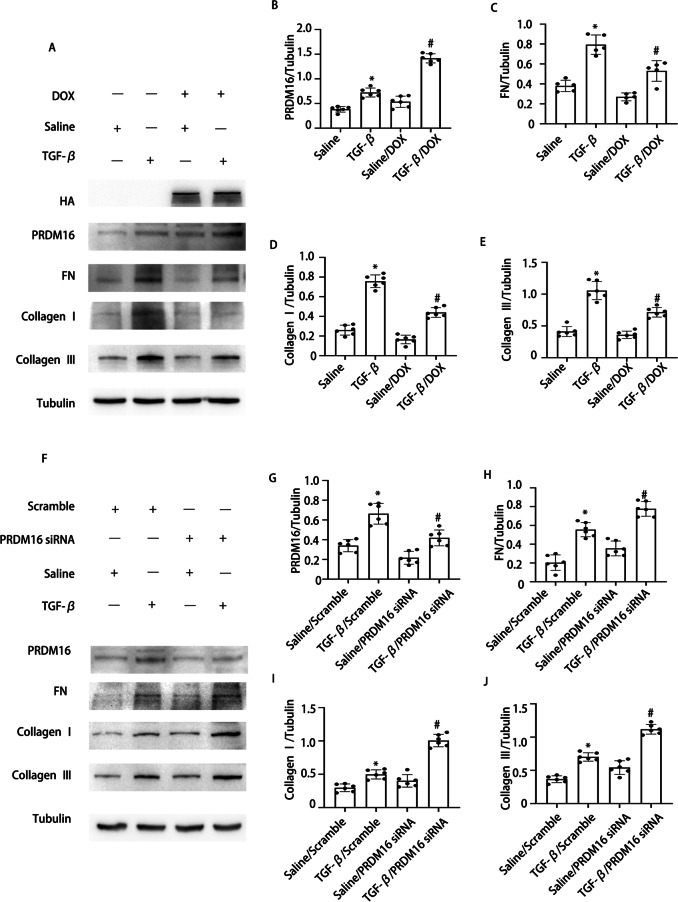

PRDM16 ameliorated TGF-β induced collagen I, collagen III, and fibronectin expression

Our prior research has indicated that PRDM16 mitigates HG-induced RF. To further explore PRDM16’s function in TGF-β-mediated fibrosis, a PRDM16 overexpressing cell line, and PRDM16 siRNA were utilized. WB results revealed that the DOX-induced PRDM16 overexpression markedly inhibited TGF-β-induced collagen I, collagen III, and fibronectin expression (Fig. 2A-E). Additionally, WB indicated a notable enhancement of collagen I, collagen III, and fibronectin expression after siPRDM16 treatment under TGF-β stimulation (Fig. 2F-J). These findings suggest that PRDM16 mitigates fibrosis when exposed to TGF-β activation.

Fig. 2.

PRDM16 facilitated the TGF-β1-induced expression of fibronectin collagen I and collagen III in BUMPT cells. BUMPT cells underwent transfection with DOX and PRDM16 siRNA, then exposed to 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 or left untreated for 24 h. A WB of PRDM16, FN, HA, collagen I, collagen III, and β-Tubulin in BUMPT cells with or without TGF-β1 and DOX treatment. B-E The GSY between them. F WB of PRDM16, FN, collagen I, collagen III, and β-Tubulin in BUMPT cells with or without TGF-β1 and PRDM16 siRNA treatment. G-J The GSY between them. Representative WB from each cohort (n = 6). Data are denoted as mean ± SD (n = 6). *p < 0.05, TGF-β with Scramble cohort vs. Saline with Scramble cohort; #p < 0.05, TGF-β with DOX cohort or TGF-β with PRDM16 siRNA cohort vs. TGF-β with Scramble cohort

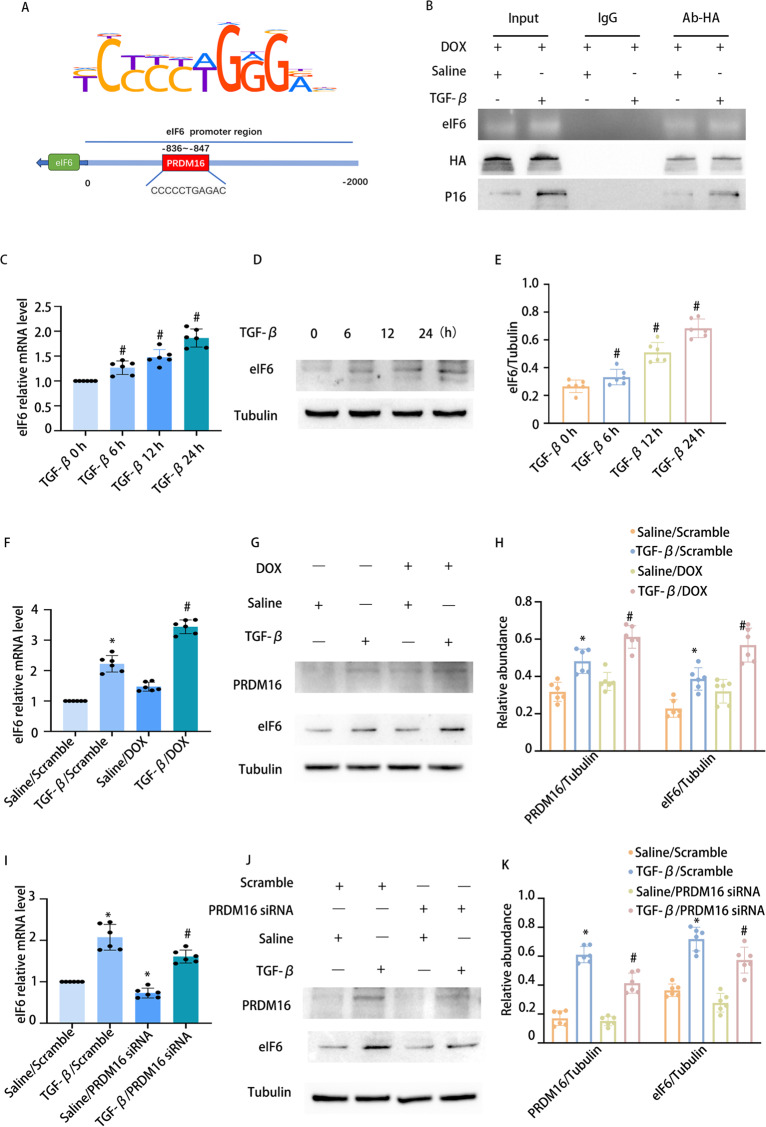

PRDM16, as a transcription factor (TF), modulates the expression of eIF6

To elucidate the mechanism by which PRDM16 mitigates fibrosis, we sought to investigate the direct interaction between PRDM16 and eIF6. Bioinformatic analysis identified a potential PRDM16 binding motif within the promoter region of the murine EIF6 gene (Fig. 3A). Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays confirmed PRDM16’s binding to the promoter region of murine eIF6 (Fig. 3B). RT-qPCR and WB indicated an increase in eIF6 expression following TGF-β treatment in BUMPT cells at 6, 12, and 24 h (Fig. 3C-E). Moreover, both RT-qPCR and WB outcomes demonstrated that eIF6 expression was markedly elevated by PRDM16 overexpression under TGF-β treatment (Fig. 3F-H). Conversely, eIF6 expression was markedly reduced by siPRDM16 during TGF-β treatment (Fig. 3I-K).

Fig. 3.

PRDM16 facilitated the TGF-β1-induced fibrosis in BUMPT cells via eIF6. BUMPT cells underwent transfection with DOX and PRDM16 siRNA, then exposed to 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 or left untreated for 24 h. A Bioinformatic analysis revealed that the promoter region of the murine eIF6 gene had a putative PRDM16 binding motif. B ChIP assays for PRDM16 were executed utilizing chromatin procured from BUMPT cells. DNA precipitates were amplified using primers flanking the putative PRDM16 binding regions. C eIf6 mRNA levels in BUMPT cells with or without TGF-β treatment were evaluated by RT-qPCR. D eIf6 and β-Tubulin protein expression in BUMPT cells with or without TGF-β1 treatment was examined by WB. E The GSY between them. F eIf6 mRNA expression in BUMPT cells subjected to TGF-β or DOX treatment or left untreated was quantified by RT-qPCR. G WB of eIf6 & PRDM16 and β-Tubulin in BUMPT cells subjected to TGF-β treatment, DOX administration, or left untreated. H The GSY between them. I eIf6 mRNA levels in BUMPT cells subjected to TGF-β treatment, PRDM16 siRNA transfection, or left untreated were quantified by RT-qPCR. J WB of eIf6 & PRDM16 and β-Tubulin in BUMPT cells exposed to TGF-β, PRDM16 siRNA, or left untreated. K The GSY between them. Data are denoted as mean ± SD (n = 6). *p < 0.05, TGF-β with Scramble cohort vs. Saline with Scramble cohort; #p < 0.05, TGF-β with DOX cohort or TGF-β with PRDM16 siRNA cohort vs. TGF-β with Scramble cohort

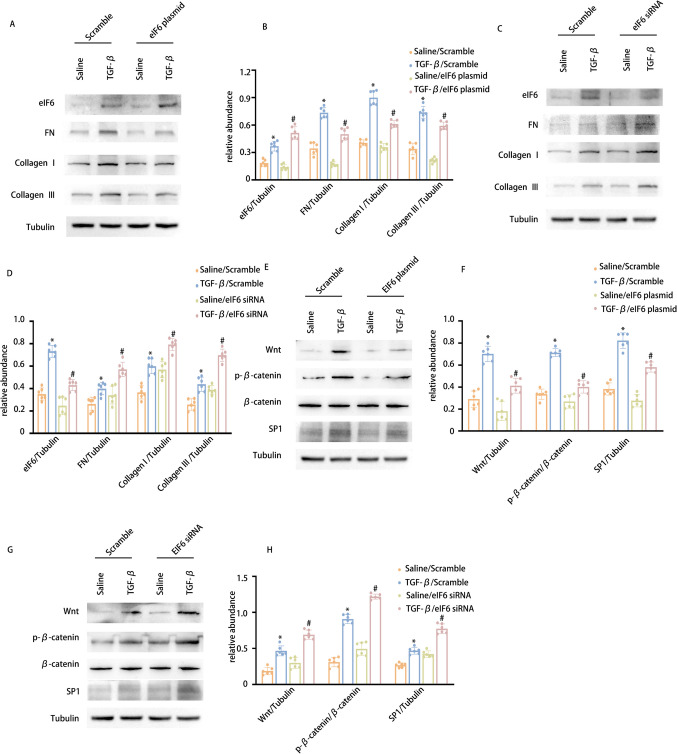

eIF6 suppresses TGF-β1-induced collagen I, collagen III, and fibronectin expression, along with the inactivation of the Wnt/β-catenin/SP1 pathway

The findings above suggest that PRDM16 regulates the expression of eIF6. To investigate eIF6’s influence on TGF-β-induced fibrosis, we initially assessed its effects. WB results demonstrated that eIF6 overexpression mitigated TGF-β-induced collagen I, collagen III, and fibronectin expression (Fig. 4A-B). Conversely, eIF6 suppression led to an increase in TGF-β-induced production of these proteins (Fig. 4C-D). However, the anti-fibrotic mechanism of eIF6 remains to be fully elucidated. Recent studies have indicated that eIF6 specifically suppresses the Wnt pathway at the beta-catenin protein level without involving proteasomal degradation in colon cancer cells [41]. Moreover, it has been established that the Sp1 family of zinc-finger TFs is triggered by Wnt/β-catenin signaling in zebrafish cells [42]. This finding still requires validation in renal tubular cells. Consistently, WB results demonstrated that eIF6 overexpression attenuated TGF-β-induced stimulation of the Wnt/β-catenin/SP1 pathway, whereas eIF6 knockdown produced the contrary outcome (Fig. 4E-H). Taken together, these findings suggest that eIF6 inhibits both RF and the downregulation of the Wnt/β-catenin/SP1 cascade during TGF-β treatment.

Fig. 4.

eIF6 modulates SP1 via the Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade, consequently diminishing the TGF-β1-induced production of collagen I, collagen III, and fibronectin. BUMPT cells underwent transfection with eIf6 plasmid and siRNA, then exposed to 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 or left untreated for 24 h. A WB of eIf6, FN, collagen I, collagen III, and β-Tubulin in BUMPT cells with or without TGF-β1 and eIf6 plasmid treatment. B The GSY between them. C WB of eIf6, FN, collagen I, collagen III, and β-Tubulin in BUMPT cells with or without TGF-β1 and eIf6 siRNA treatment. D The GSY between them. E WB of SP1, Wnt, β-catenin, p-β-catenin, and β-Tubulin in BUMPT cells with or without TGF-β1 and eIf6 plasmid treatment. F The GSY between them. G WB of SP1, Wnt, β-catenin, p-β-catenin, and β-Tubulin in BUMPT cells with or without TGF-β1 and eIf6 siRNA treatment. H The GSY between them Data are denoted as mean ± SD (n = 6). *p < 0.05, TGF-β with Scramble cohort vs. Saline with Scramble cohort; #p < 0.05, TGF-β with eIf6 plasmid cohort or TGF-β with eIf6 siRNA cohort vs. TGF-β with Scramble cohort

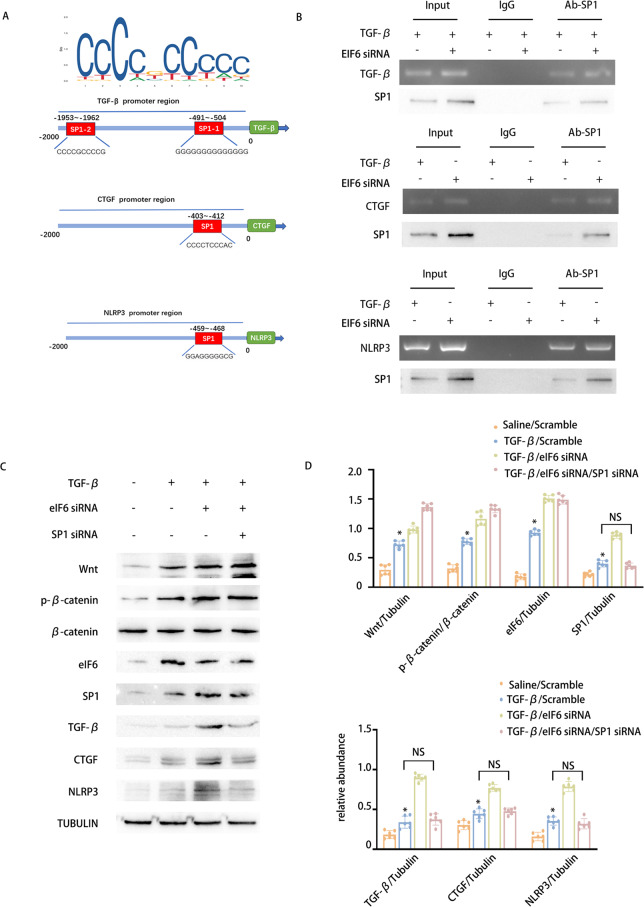

eIF6 suppresses the Wnt/β-catenin/SP1 axis to reduce the expression of fibrosis and inflammation factors, including TGF-β, CTGF, and NLRP3

Our prior research has suggested that eIF6 inhibits the stimulation of the Wnt/β-catenin/SP1 pathway. Nevertheless, the precise mechanisms through which the Wnt/β-catenin/SP1 axis influences fibrosis remain largely unclarified. It is well established that SP1 functions as a TF capable of modulating the expression of numerous genes. TGF-β1, CTGF, and NLRP3 are recognized as key mediators of fibrosis and inflammation during the transition from AKI to CKD. Therefore, we investigated whether SP1 regulates their expression. Initially, bioinformatic analysis predicted the presence of a potential SP1 binding motif within the promoter regions of the TGF-β1, CTGF, and NLRP3 genes. Subsequently, chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments verified that SP1 attaches to the promoter regions of murine TGF-β1, CTGF, and NLRP3, and this binding was enhanced by the knockdown of eIF6 (Fig. 5A-B). To further explore whether SP1 mediates the influence of eIF6 on TGF-β1, CTGF, and NLRP3 expression, siRNAs targeting EIF6 and SP1 were individually or concurrently transfected into BUMPT cells, succeeded by a 24-h TGF-β1 treatment. WB revealed that EIF6 knockdown elevated TGF-β-induced expression of TGF-β1, CTGF, and NLRP3, while SP1 depletion counteracted these outcomes (Fig. 5C-D). In conclusion, these outcomes suggest that eIF6 suppresses the stimulation of the Wnt/β-catenin/SP1 pathway to downregulate the expression of TGF-β, CTGF, and NLRP3.

Fig. 5.

eIF6 affects the expression of TGF-β、CTGF and NLRP3 via the Wnt/β-catenin/SP1 pathway.The eIf6 and SP1 siRNAs were introduced into BUMPT cells, which were subsequently exposed to 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 or left untreated for 24 h. A Bioinformatic analysis revealed that the promoter region of murine CTGF & TGF-β1 & NLRP3 gene existed a putative SP1 binding motif. B ChIP assays for SP1 were executed with chromatin procured from BUMPT cells. DNA obtained through precipitation was amplified utilizing oligonucleotides encompassing the putative SP1 binding sites for CTGF, TGF-β1, and NLRP3. C WB of eIf6, Wnt, β-catenin, SP1, and β-Tubulin in BUMPT cells subjected to TGF-β1 treatment, eIf6 siRNA, and SP1 siRNA, or left untreated. D The GSY between them. Data are denoted as mean ± SD (n = 6). *p < 0.05, TGF-β1 with Scramble cohort or TGF-β1 with eIf6 siRNA cohort or TGF-β1 with SP1 siRNA cohort vs. Saline with Scramble cohort

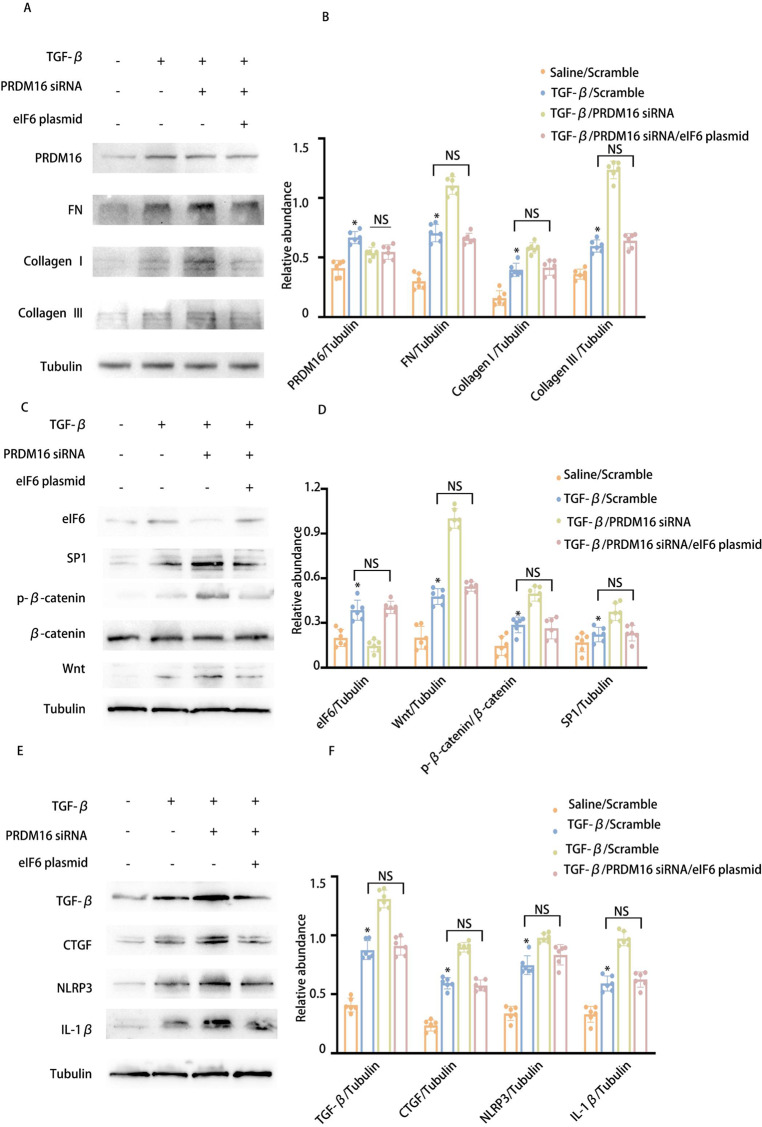

Inhibition of PRDM16 can reverse the anti-fibrotic effect of eIF6

Our previous study identified that eIF6 inhibits fibrosis via the Wnt/β-catenin/SP1/TGF-β, CTGF, and NLRP3 axis and that PRDM16 regulates eIF6 expression at the transcriptional level. To explore whether eIF6 facilitates PRDM16’s effects on the Wnt/β-catenin/SP1/TGF-β, CTGF, and NLRP3 pathways, PRDM16 siRNA and an eIF6 plasmid were transfected either individually or in combination into BUMPT cells, succeeded by TGF-β1 treatment for 24 h. WB results indicated that PRDM16 knockdown increased the stimulation of the Wnt/β-catenin/SP1 axis and elevated TGF-β, CTGF, and NLRP3 expression, effects that were reversed by eIF6 overexpression (Fig. 6A-F). These outcomes confirm that PRDM16 suppresses the stimulation of the Wnt/β-catenin/SP1/TGF-β, CTGF, and NLRP3 pathways to attenuate RF through the upregulation of eIF6.

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of PRDM16 can reverse the anti-fibrotic effect of eIF6. The eIf6 plasmid and siRNA were introduced into BUMPT cells, which were subsequently exposed to 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 or left untreated for 24 h. A WB of PRDM16, eIf6, FN, collagen I, collagen III, and β-Tubulin in BUMPT cells subjected to TGF-β1 treatment, eIf6 plasmid transfection, and PRDM16 siRNA knockdown. B The GSY between them. Data are denoted as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, TGF-β with Scramble cohort or TGF-β with PRDM16 siRNA cohort vs. Saline with Scramble cohort. C WB of eIf6, Wnt, β-catenin, SP1, and β-Tubulin in BUMPT cells subjected to TGF-β1 treatment, eIf6 plasmid transfection, and PRDM16 siRNA knockdown. D The GSY between them. E WB of TGF-β1, CTGF, NLRP3, IL-1β, and β-Tubulin in BUMPT cells subjected to TGF-β1 treatment, eIf6 plasmid transfection, and PRDM16 siRNA knockdown. F The GSY between them. Data are denoted as the means ± SD (n = 6). *p < 0.05, TGF-β with eIf6 plasmid cohort or TGF-β with eIf6 siRNA cohort vs. TGF-β with Scramble cohort

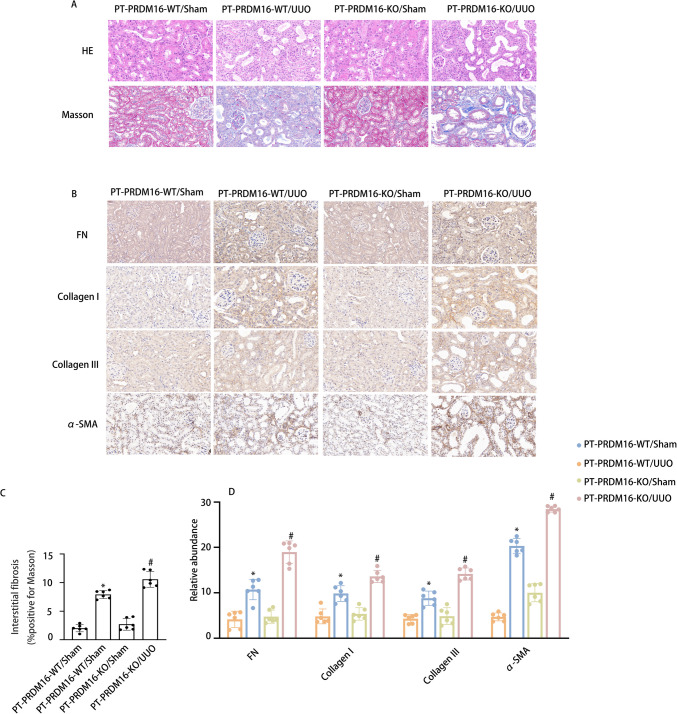

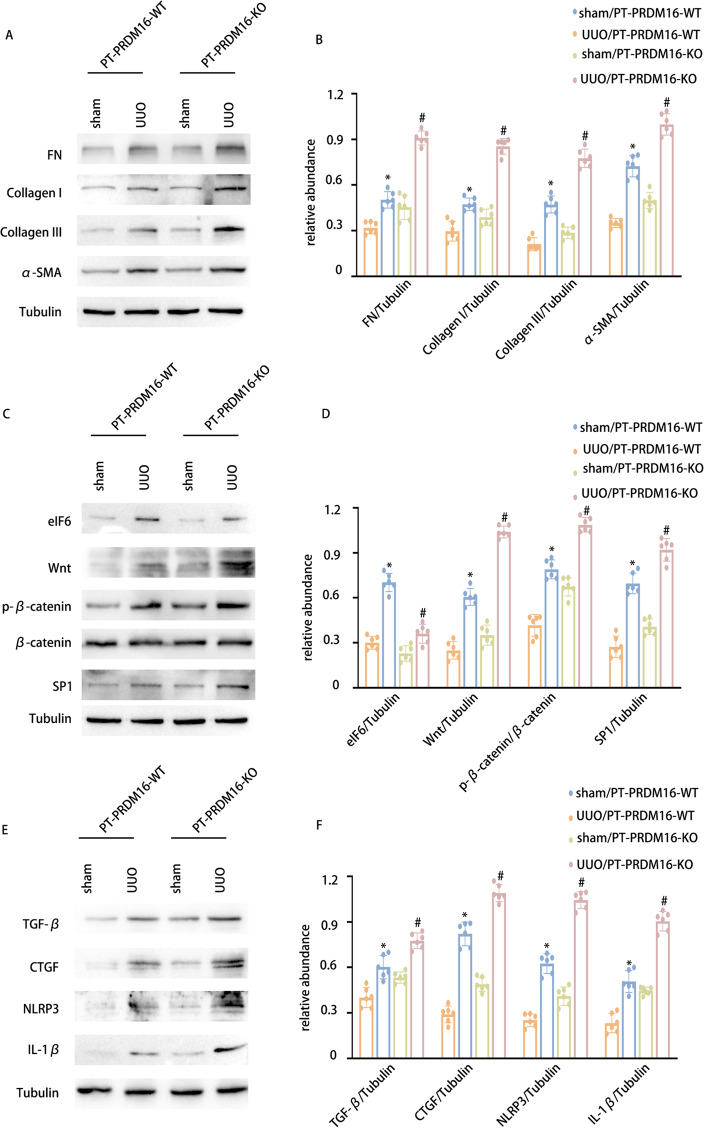

PRDM16-KO aggravated the RF in UUO and IR 28-day mice via the eIF6/Wnt/β-catenin/SP1 axis

To elucidate the function of tubular PRDM16, a mouse model of PRDM16 knockout (KO) in the kidney’s proximal tubules was developed. Details regarding the breeding protocol and genetic identification of PRDM16-KO mice are described in our earlier publications [33]. PT-PRDM16-WT and PT-PRDM16-KO littermate mice underwent UUO for 7 days and IR for 28 days. HE staining revealed that PT-PRDM16-KO mice displayed a notable elevate in tubular dilation and atrophy induced by UUO and IR. Masson’s trichrome staining revealed a significant enhancement in ECM accumulation in PT-PRDM16-KO tissues following UUO and IR induction (Fig. 7 & Supplementary Fig. 1 A-C). Immunohistochemical staining indicated that PRDM16-KO elevated collagen I, collagen III, fibronectin, and α-SMA expression in response to UUO and IR (Fig. 7 & Supplementary Fig. 1D-E). Moreover, WB outcomes indicated that PRDM16-KO markedly elevated collagen I, collagen III, fibronectin, α-SMA, Wnt, β-catenin, SP1, TGF-β, CTGF, NLRP3, and IL-1β expression while decreasing EIF6 expression under UUO and IR conditions (Fig. 8 & Supplementary Fig. 2A-F). These findings provide substantial evidence supporting the inference that PT-PRDM16-KO mice could potentially aggravate kidney fibrosis triggered by UUO and IR.

Fig. 7.

PRDM16-KO attenuates tubulointerstitial fibrosis in UUO mice. A Hematoxylin–eosin-stained and Representative Masson’s trichrome-stained paraffin-embedded mouse kidney sections. B Semiquantitative scores of tubulointerstitial fibrosis in the kidney cortex. C Immunohistochemical staining of FN, collagen I, collagen III, α-SMA, and F4/80. D Quantification analysis of FN, collagen I, collagen III and α-SMA staining. Original magnification × 400. Scar Bar: 100 µM. Data are denoted as the means ± SD (n = 6). *p < 0.05, UUO with PRDM16-WT cohort vs. sham with PRDM16-WT cohort; #p < 0.05, UUO with PRDM16-KO vs. UUO with PRDM16-WT cohort

Fig. 8.

PRDM16-KO aggravates the expression of FN, Collagen I, collagen III, and α-SMA in UUO mice via/eIF6/Wnt/β-catenin/SP1-axis. A WB of FN, collagen I, collagen III, and α-SMA and β-Tubulin in the cortex of the kidney. B The GSY between them. C WB of eIF6, Wnt, p-β-catenin, β-catenin, SP1, and β-Tubulin in the cortex of the kidney. D The GSY between them. E WB of TGF-β1, CTGF, NLRP3 IL-1β, and β-Tubulin in the cortex of the kidney. F The GSY between them. Data are denoted as the means ± SD (n = 6). *p < 0.05, UUO with PRDM16-WT cohort vs. sham with PRDM16-WT cohort; #p < 0.05, UUO with PRDM16-KO vs. UUO with PRDM16-WT cohort

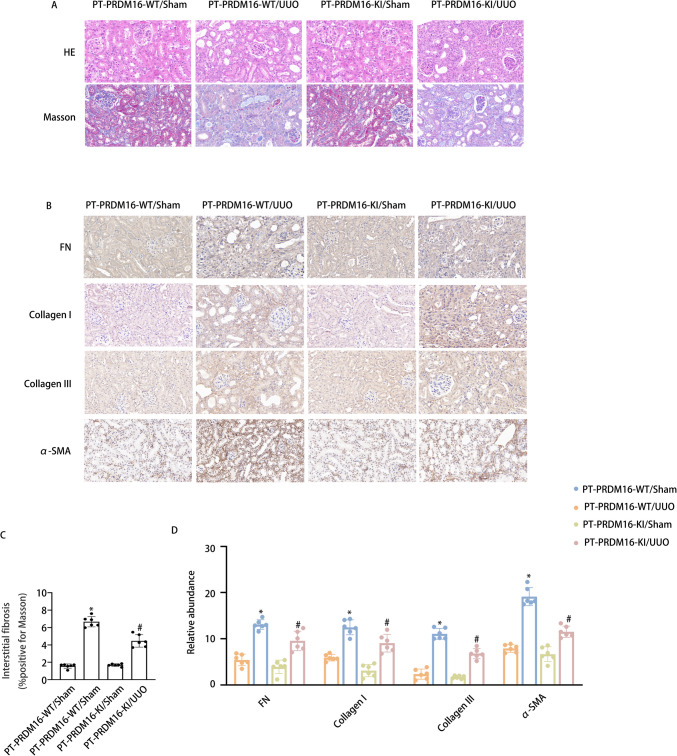

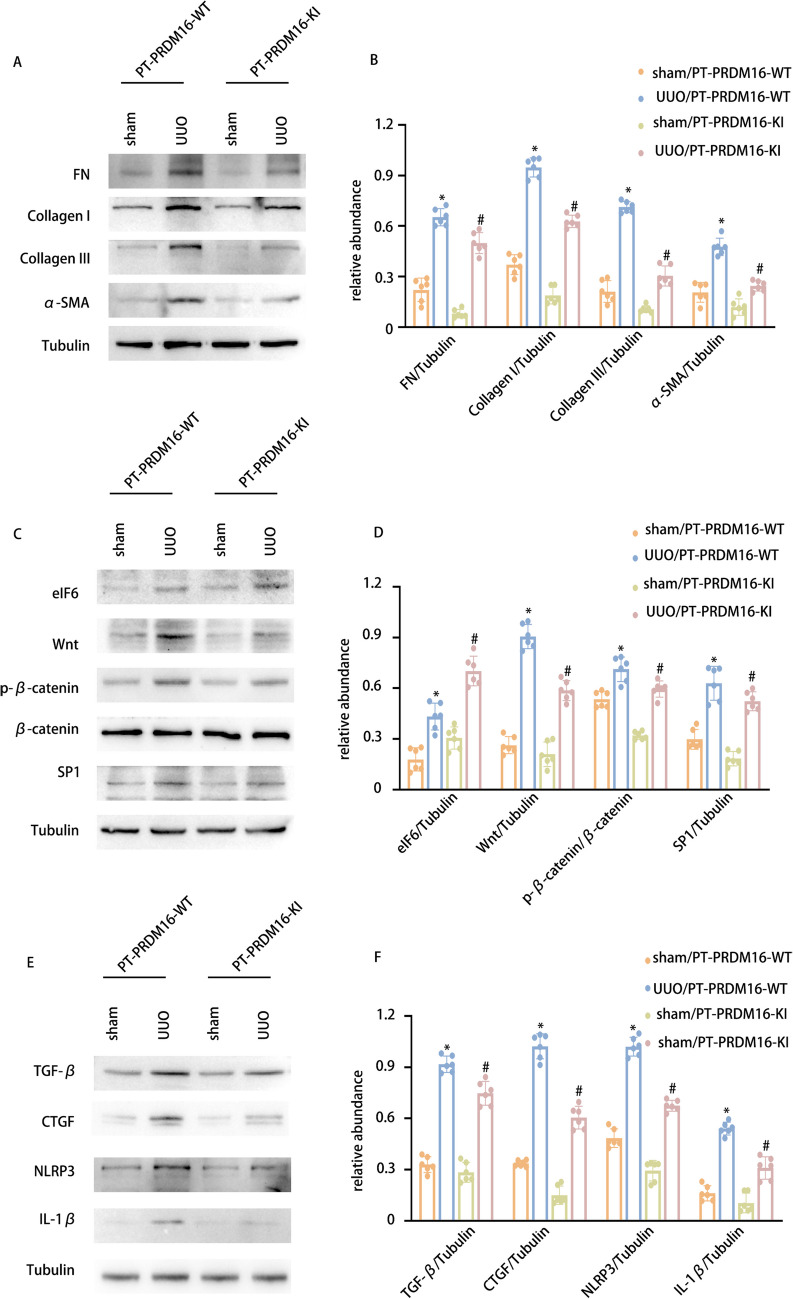

PRDM16-KI mitigated the RF in UUO and IR 28-day mice via the eIF6/Wnt/β-catenin/SP1 axis

In addition to generating a PRDM16-KO mouse model, a PRDM16 knock-in (KI) mouse model was also constructed. The breeding protocol and genetic identification methods for PRDM16-KI mice are detailed in our previously published work [33]. Littermate mice of PT-PRDM16-WT and PT-PRDM16-KI underwent UUO and IR for 28 days. Staining analyses, including HE and Masson’s trichrome staining, revealed that PRDM16-KI markedly reduced tubular epithelial disruption, RF, and glomerular hypertrophy induced by UUO and IR (Fig. 9 & Supplementary Fig. 3 A-C). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated that PRDM16-KI decreased fibronectin, collagen I, collagen III, and α-SMA levels following UUO and IR induction (Fig. 9 & Supplementary Fig. 3D-E). Furthermore, WB results indicated that PRDM16-KI markedly mitigated collagen I, collagen III, fibronectin, α-SMA, Wnt, β-catenin, SP1, TGF-β, CTGF, NLRP3, and IL-1β expression, while enhancing EIF6 expression under UUO and IR conditions (Fig. 10 & Supplementary Fig. 4A-F). These findings provide compelling evidence to support the inference that PT-PRDM16-KI mice could alleviate RF resulting from UUO and IR.

Fig. 9.

PRDM16-KI alleviated tubulointerstitial fibrosis in UUO mice. A Hematoxylin–eosin-stained and Representative Masson’s trichrome-stained paraffin-embedded mouse kidney sections. B Semiquantitative scores of tubulointerstitial fibrosis in the kidney cortex. C Immunohistochemical staining of FN, collagen I, collagen III, α-SMA, and F4/80. D Quantification analysis of FN, collagen I, collagen III,and α-SMA staining. Original magnification × 400. Scar Bar:100 µM. Data are denoted as the means ± SD (n = 6). *p < 0.05, UUO with PRDM16-WT cohort vs. sham with PRDM16-WT cohort; #p < 0.05, UUO with PRDM16-KI vs. UUO with PRDM16-WT cohort

Fig. 10.

PRDM16-KI attenuates the expression of FN, Collagen I, collagen III, and α-SMA in UUO mice via/eIF6/Wnt/β-catenin/SP1-axis. A WB of FN, collagen I, collagen III, and α-SMA and β-Tubulin in the cortex of the kidney. B The GSY between them. C WB of eIF6, Wnt, p-β-catenin, β-catenin, SP1, and β-Tubulin in the cortex of the kidney. D The GSY between them. E WB of TGF-β1, CTGF, NLRP3 IL-1β, and β-Tubulin in the cortex of the kidney. F The GSY between them. Data are denoted as the means ± SD (n = 6). *p < 0.05, UUO with PRDM16-WT cohort vs. sham with PRDM16-WT cohort; #p < 0.05, UUO with PRDM16-KI vs. UUO with PRDM16-WT cohort

Overexpression of PRDM16 attenuates renal interstitial fibrosis regardless of its early protective effect against AKI

Previous research has shown that PRDM16 exerts a protective effect on AKI. To determine whether PRDM16’s influence on the AKI to CKD transition operates independently of its protective role in AKI, mice were injected with an ADV-PRDM16 plasmid via the tail vein 48 h post-ischemic AKI. The results demonstrated that kidney function deterioration, tubular injury, and interstitial fibrosis induced by I/R were markedly ameliorated by the ADV-PRDM16 plasmid (Supplementary Figs. 5 & 6). HE and Masson’s staining analyses revealed that the ADV-PRDM16 plasmid markedly reduced IR-induced renal interstitial fibrosis (Supplementary Figs. 5 & 6). Immunohistochemical staining indicated that the ADV-PRDM16 plasmid decreased fibronectin, collagen I, collagen III, and α-SMA expression following IR induction (Supplementary Figs. 5 & 6). Moreover, WB results demonstrated that the ADV-PRDM16 plasmid notably mitigated collagen I, collagen III, fibronectin, α-SMA, Wnt, β-catenin, SP1, TGF-β, CTGF, NLRP3, and IL-1β expression, while enhancing EIF6 expression under IR conditions (Supplementary Fig. 5 & 6). Collectively, these findings suggest that PRDM16 mitigates the progression of AKI to CKD independently of its initial protective effect on AKI.

PRDM16/eIF6/Wnt/β-catenin/SP1-axis in the human kidneys

To further substantiate the protective role of PRDM16 in the AKI-CKD transition, tissues were collected from patients with MCD and severe OB, with peritumoral renal tissues serving as controls. The patients’ basic information is presented in Supplementary Table (1). Initially, HE and Masson staining were utilized to assess tubular injury and the extent of RF in individuals with MCD and severe OB (Supplementary Fig. 7 A). Additionally, WB results revealed that severe OB was linked to diminished expression of PRDM16 and eIF6, alongside increased FN, collagen I, collagen III, α-SMA, Wnt, β-catenin, SP1, TGF-β1, CTGF, NLRP3, and IL-1β expression, in comparison to MCD (Supplementary Fig. 7B–G). Integrating these findings with previous data, it can be concluded that PRDM16 suppresses the progression of AKI to CKD via the eIF6/Wnt/β-catenin/SP1/TGF-β, CTGF and NLRP3 pathways.

Discussion

The precise mechanisms of homeostatic unbalance underlying the injury of renal TECs contributing to renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis during the progression from AKI to CKD remain incompletely elucidated. This investigation revealed that PRDM16 is elevated in renal tubular cells under conditions of UUO and OB and serves to prevent renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Mechanistically, PRDM16 was found to activate eIF6, which subsequently suppresses the production of TGF‐β1, CTGF, and NLRP3 by diminishing Wnt, β-catenin, and SP1 expression. Finally, both UUO and ischemia–reperfusion-injury (IRI) models were examined, and these findings were corroborated in human OB kidney samples. The data suggests that PRDM16 in TECs functions as a critical homeostasis regulation factor to suppress the progression of renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis and inflammation during transition of AKI to CKD.Although this study has revealed the important role and mechanism of PRDM16 in inhibiting the transition from acute kidney injury (AKI) to chronic kidney disease (CKD), there are still some limitations. In terms of experimental models, although mouse models of unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) and ischemia–reperfusion injury (IRI) were used to simulate the process of kidney diseases, there are differences between animal models and the pathophysiological processes of human diseases. These models cannot fully reflect the complex situation of the transition from AKI to CKD in humans, which may affect the translation of research results into clinical applications.

Many transcription factors played a critical role in kidney development and the balance of homeostasis [43], such as GLI3,Glis2, PAX2 and SALL4 [44–48]. PRDM16 also belongs to a transcription factor. It has been primarily implicated in the biogenesis of brown and beige adipocytes [29, 49, 50]. Previous studies have shown that PRDM16 inhibits adipose tissue fibrosis as well as cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and fibrosis [51–54]. Our recent research has also indicated that PRDM16 represses RF in early diabetic kidney disease (DKD) [33] and reduces cisplatin- and ischemia-induced AKI [34, 35]. In the current study, the data revealed that PRDM16 in tubular cells not only inhibited TGF‐β1-induced RF in vitro(Fig. 2) but also ameliorated UUO- and IRI-induced renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis and inflammation in vivo (Figs. 7, 8, 9 and 10, Supplementary Fig. 1–4). Furthermore, it was demonstrated that PRDM16’s prevention of RF and inflammation following ischemic AKI is independent of its protective effects against ischemic AKI (Supplementary Fig. 5–6). These outcomes indicate that PRDM16 acts as a critical homeostasis regulation factor of kidney fibrosis and inflammation.

PRDM16, a TF, is implicated in regulating metabolic processes through the control of multiple gene transcriptions [55]. PRDM16 downregulates the expression of GTF2IRD1 to reduce TGF-β levels in adipose tissue fibrosis [51]. In the context of cardiac fibrosis, PRDM16 inhibits fibrosis by repressing the TGF-β signaling cascade [52]. Our recent study also identified that PRDM16 induces TRPA1 to diminish TGF-β expression by inactivating the MAPK signaling pathway in DKD [33]. In our research, predictions and ChIP assays verified that PRDM16 attaches to the promoter region of eukaryotic initiation factor 6 (eIF6) (Fig. 3). EIF6 also referred to as protein p27BBP (beta 4 binding protein), functions as a modulator of TGF-β1 expression and negatively influences collagen synthesis [56]. Consistently, in this investigation, it was corroborated that eIF6 suppresses TGF-β1-induced RF [Fig. 4]. Moreover, we expanded upon previous findings and elucidated the underlying mechanism whereby eIF6 not only inhibits TGF-β1 expression but also reduces CTGF and NLRP3 levels by repressing the Wnt/β-catenin/SP1 axis (Figs. 4 and 5). Recent research has demonstrated that injured tubular cells promote the generation of fibrogenic factors, encompassing TGF-β and CTGF [16–20], and that the inflammatory factor NLRP3 [22, 24] plays a pivotal role during the AKI to CKD transition. Our findings demonstrate that PRDM16 enhances the expression of eIF6, which in turn suppresses TGF-β, CTGF, and NLRP3 in tubular cells, thereby ameliorating the progression from AKI to CKD. This finding was further validated in tubular PRDM16 knock-in or knockout mice models with UUO or IRI, as well as in individuals with MCD and OB patients (Supplementary Fig. 7).

In summary, our research demonstrates that PRDM16 mitigates RF and inflammation during the transition from AKI to CKD. Mechanistically, PRDM16 transcriptionally upregulates eIF6 expression, which subsequently downregulates profibrotic genes expression, encompassing TGF-β and CTGF, and pro-inflammatory factors like NLRP3 by inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin/SP1 axis. In addition, these observations suggest that PRDM16 acts as a critical homeostasis regulation factor to inhibit development of fibrosis and inflammation and represents a possible therapeutic avenue for the AKI to CKD transition. Furthermore, the data uncover a novel anti-fibrotic and anti-inflammatory pathway involving PRDM16, eIF6, Wnt/β-catenin/SP1, TGF-β, CTGF, and NLRP3.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- BUMPT

Boston university mouse proximal tubule

- AKI

Acute kidney injury

- PRDM16

PRD1-BF1-RIZ1 homologous domain-containing protein 16

- SP1

Specificity Protein 1

- eIF6

Eukaryotic initiation factor 6

- PC

Paracancerous tissue of kidney

- MCD

Minimal change nephropathy

- OB

Obstructive nephropathy

- DOX

Doxycycline

- BUN

Blood Urea Nitrogen

Author contributions

Lidong Wu and Dongshan Zhang was responsible for conceptualization, data curation, project administration, and resource management, as well as writing, reviewing, and editing. Yang Xia and Xingjin Li performed cell experiments, compiled and analyzed the data, and contributed to manuscript preparation. Xiaozhou Li executed animal experiments and examined clinical data. Yong Guo, Shuanfa Qiu, Yijian Li, and Huiling Li supplied reagents and materials. All authors participated in the manuscript review.

Funding

The investigation was partly funded by awards from the National Natural Science Foundation of China [82370703, 82090024, 82171088].

Data availability

All data is included in the manuscript and/or supporting information.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The researchers affirm the absence of any competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xiaozhou Li, Yang Xia, and Xingjin Li contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Lidong Wu, Email: ndefy94005@ncu.edu.cn.

Dongshan Zhang, Email: dongshanzhang@csu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Wang S, Qin L (2022) Homeostatic medicine: a strategy for exploring health and disease. Curr Med (Cham, Switzerland) 1(1):16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meizlish ML, Franklin RA, Zhou X, Medzhitov R (2021) Tissue homeostasis and inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol 39:557–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fries C, Hermiston ML (2023) Challenging T-ALL to IL-7Rp dual inhibition. Blood 142(2):124–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puelles VG, Huber TB (2022) Kidneys control inter-organ homeostasis. Nat Rev Nephrol 18(4):207–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang PM, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Lan HY (2019) Macrophages: versatile players in renal inflammation and fibrosis. Nat Rev Nephrol 15(3):144–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanaka S, Portilla D, Okusa MD (2023) Role of perivascular cells in kidney homeostasis, inflammation, repair and fibrosis. Nat Rev Nephrol 19(11):721–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park S, Baek SH, Ahn S, Lee KH, Hwang H, Ryu J, Ahn SY, Chin HJ, Na KY, Chae DW, Kim S (2018) Impact of electronic acute kidney injury (AKI) alerts with automated nephrologist consultation on detection and severity of AKI: a quality improvement study. Am J Kidney Dis 71(1):9–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aklilu AM, Kumar S, Nugent J, Yamamoto Y, Coronel-Moreno C, Kadhim B, Faulkner SC, O’Connor KD, Yasmin F, Greenberg JH, Moledina DG, Testani JM, Wilson FP (2024) COVID-19-associated acute kidney injury and longitudinal kidney outcomes. JAMA Intern Med 184(4):414–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Venkatachalam MA, Weinberg JM, Kriz W, Bidani AK (2015) Failed tubule recovery, AKI-CKD transition, and kidney disease progression. J Am Soc Nephrol 26(8):1765–1776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He L, Wei Q, Liu J, Yi M, Liu Y, Liu H, Sun L, Peng Y, Liu F, Venkatachalam MA, Dong Z (2017) AKI on CKD: heightened injury, suppressed repair, and the underlying mechanisms. Kidney Int 92(5):1071–1083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wonnacott A, Meran S, Amphlett B, Talabani B, Phillips A (2014) Epidemiology and outcomes in community-acquired versus hospital-acquired AKI. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol: CJASN 9(6):1007–1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo R, Duan J, Pan S, Cheng F, Qiao Y, Feng Q, Liu D, Liu Z (2023) The road from AKI to CKD: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets of ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis 14(7):426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang M, Bai M, Lei J, Xie Y, Xu S, Jia Z, Zhang A (2020) Mitochondrial dysfunction and the AKI-to-CKD transition. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 319(6):F1105-f1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Z, Zhang C (2022) From AKI to CKD: maladaptive repair and the underlying mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci 23(18):10880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferenbach DA, Bonventre JV (2015) Mechanisms of maladaptive repair after AKI leading to accelerated kidney ageing and CKD. Nat Rev Nephrol 11(5):264–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kellum JA, Romagnani P, Ashuntantang G, Ronco C, Zarbock A, Anders HJ (2021) Acute kidney injury. Nat Rev Dis Primers 7(1):52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geng H, Lan R, Singha PK, Gilchrist A, Weinreb PH, Violette SM, Weinberg JM, Saikumar P, Venkatachalam MA (2012) Lysophosphatidic acid increases proximal tubule cell secretion of profibrotic cytokines PDGF-B and CTGF through LPA2- and Gαq-mediated Rho and αvβ6 integrin-dependent activation of TGF-β. Am J Pathol 181(4):1236–1249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ninichuk V, Gross O, Segerer S, Hoffmann R, Radomska E, Buchstaller A, Huss R, Akis N, Schlöndorff D, Anders HJ (2006) Multipotent mesenchymal stem cells reduce interstitial fibrosis but do not delay progression of chronic kidney disease in collagen4A3-deficient mice. Kidney Int 70(1):121–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimura M, Asano M, Abe K, Miyazaki M, Suzuki T, Hishida A (2005) Role of atrophic changes in proximal tubular cells in the peritubular deposition of type IV collagen in a rat renal ablation model. Nephrol, Dial, Transplant 20(8):1559–1565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberts AB, Sporn MB, Assoian RK, Smith JM, Roche NS, Wakefield LM, Heine UI, Liotta LA, Falanga V, Kehrl JH et al (1986) Transforming growth factor type beta: rapid induction of fibrosis and angiogenesis in vivo and stimulation of collagen formation in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 83(12):4167–4171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang G, Yu T, Chai X, Zhang S, Liu J, Zhou Y, Yin D, Zhang C (2024) Gradient rotating magnetic fields impairing F-Actin-related gene CCDC150 to inhibit triple-negative breast cancer metastasis by inactivating TGF-β1/SMAD3 signaling pathway. Research (Washington, D. C.) 7:0320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao ZB, Marschner JA, Iwakura T, Li C, Motrapu M, Kuang M, Popper B, Linkermann A, Klocke J, Enghard P, Muto Y, Humphreys BD, Harris HE, Romagnani P, Anders HJ (2023) Tubular epithelial cell HMGB1 promotes AKI-CKD transition by sensitizing cycling tubular cells to oxidative stress: a rationale for targeting HMGB1 during AKI recovery. J Am Soc Nephrol 34(3):394–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang L, Chen F, Dong J, Wang R, Bi G, Xu D, Zhang Y, Deng Y, Lin W, Yang Z, Cao W (2023) HDAC3 aberration-incurred GPX4 suppression drives renal ferroptosis and AKI-CKD progression. Redox Biol 68:102939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng T, Tan Y, Qiu J, Xie Z, Hu X, Zhang J, Na N (2021) Alternative polyadenylation trans-factor FIP1 exacerbates UUO/IRI-induced kidney injury and contributes to AKI-CKD transition via ROS-NLRP3 axis. Cell Death Dis 12(6):512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen J, Lu H, Wang X, Yang J, Luo J, Wang L, Yi X, He Y, Chen K (2022) VNN1 contributes to the acute kidney injury-chronic kidney disease transition by promoting cellular senescence via affecting RB1 expression. FASEB J 36(9):e22472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiong M, Chen H, Fan Y, Jin M, Yang D, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Petersen RB, Su H, Peng A, Wang C, Zheng L, Huang K (2023) Tubular Elabela-APJ axis attenuates ischemia-reperfusion induced acute kidney injury and the following AKI-CKD transition by protecting renal microcirculation. Theranostics 13(10):3387–3401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu J, Qiao J, Yu Q, Liu B, Zhen J, Liu Y, Ma Q, Li Y, Wang Q, Wang C, Lv Z (2021) Role of SIK1 in the transition of acute kidney injury into chronic kidney disease. J Transl Med 19(1):69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Q, Li H, Tajima K, Verkerke ARP, Taxin ZH, Hou Z, Cole JB, Li F, Wong J, Abe I, Pradhan RN, Yamamuro T, Yoneshiro T, Hirschhorn JN, Kajimura S (2022) Post-translational control of beige fat biogenesis by PRDM16 stabilization. Nature 609(7925):151–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kajimura S (2015) Promoting brown and beige adipocyte biogenesis through the PRDM16 pathway. Int J Obes Suppl 5(Suppl 1):S11–S14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang W, Ishibashi J, Trefely S, Shao M, Cowan AJ, Sakers A, Lim HW, O’Connor S, Doan MT, Cohen P, Baur JA, King MT, Veech RL, Won KJ, Rabinowitz JD, Snyder NW, Gupta RK, Seale P (2019) A PRDM16-driven metabolic signal from adipocytes regulates precursor cell fate. Cell Metab 30(1):174-189.e5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chi J, Cohen P (2016) The multifaceted roles of PRDM16: adipose biology and beyond. Trends Endocrinol Metab 27(1):11–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harms MJ, Ishibashi J, Wang W, Lim HW, Goyama S, Sato T, Kurokawa M, Won KJ, Seale P (2014) Prdm16 is required for the maintenance of brown adipocyte identity and function in adult mice. Cell Metab 19(4):593–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu F, Jiang H, Li X, Pan J, Li H, Wang L, Zhang P, Chen J, Qiu S, Xie Y, Li Y, Zhang D, Dong Z (2024) Discovery of PRDM16-mediated TRPA1 induction as the mechanism for low tubulo-interstitial fibrosis in diabetic kidney disease. Adv Sci (Weinh) 11(7):e2306704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng Q, Xing J, Li X, Tang X, Zhang D (2024) PRDM16 suppresses ferroptosis to protect against sepsis-associated acute kidney injury by targeting the NRF2/GPX4 axis. Redox Biol 78:103417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li X, Xu F, Zhang P, Mao L, Guo Y, Li H, Xie Y, Li Y, Liao Y, Chen J, Wu D, Zhang D (2024) Overexpression of PRDM16 attenuates acute kidney injury progression: genetic and pharmacological approaches. MedComm 5(10):e737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yi L, Ai K, Li H, Qiu S, Li Y, Wang Y, Li X, Zheng P, Chen J, Wu D, Xiang X, Chai X, Yuan Y, Zhang D (2021) CircRNA_30032 promotes renal fibrosis in UUO model mice via miRNA-96-5p/HBEGF/KRAS axis. Aging 13(9):12780–12799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang R, Xu X, Li H, Chen J, Xiang X, Dong Z, Zhang D (2017) p53 induces miR199a-3p to suppress SOCS7 for STAT3 activation and renal fibrosis in UUO. Sci Rep 7:43409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang D, Sun L, Xian W, Liu F, Ling G, Xiao L, Liu Y, Peng Y, Haruna Y, Kanwar YS (2010) Low-dose paclitaxel ameliorates renal fibrosis in rat UUO model by inhibition of TGF-beta/Smad activity. Lab Inv J Tech Methods Pathol 90(3):436–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li X, Pan J, Li H, Li G, Liu X, Liu B, He Z, Peng Z, Zhang H, Li Y, Xiang X, Chai X, Yuan Y, Zheng P, Liu F, Zhang D (2020) DsbA-L mediated renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis in UUO mice. Nat Commun 11(1):4467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ai K, Pan J, Zhang P, Li H, He Z, Zhang H, Li X, Li Y, Yi L, Kang Y, Wang Y, Xiang X, Chai X, Zhang D (2022) Methyl-CpG-binding domain protein 2 contributes to renal fibrosis through promoting polarized M1 macrophages. Cell Death Dis 13(2):125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ji Y, Shah S, Soanes K, Islam MN, Hoxter B, Biffo S, Heslip T, Byers S (2008) Eukaryotic initiation factor 6 selectively regulates Wnt signaling and beta-catenin protein synthesis. Oncogene 27(6):755–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thorpe CJ, Weidinger G, Moon RT (2005) Wnt/beta-catenin regulation of the Sp1-related transcription factor sp5l promotes tail development in zebrafish. Development (Cambridge, England) 132(8):1763–1772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uhlenhaut NH, Treier M (2008) Transcriptional regulators in kidney disease: gatekeepers of renal homeostasis. Trends Genet: TIG 24(7):361–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gill PS, Rosenblum ND (2006) Control of murine kidney development by sonic hedgehog and its GLI effectors. Cell Cycle (Georgetown, Tex.) 5(13):1426–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim YS, Kang HS, Herbert R, Beak JY, Collins JB, Grissom SF, Jetten AM (2008) Kruppel-like zinc finger protein Glis2 is essential for the maintenance of normal renal functions. Mol Cell Biol 28(7):2358–2367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harshman LA, Brophy PD (2012) PAX2 in human kidney malformations and disease. Pediatr Nephrol (Berlin, Germany) 27(8):1265–1275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Che J, Wu P, Wang G, Yao X, Zheng J, Guo C (2020) Expression and clinical value of SALL4 in renal cell carcinomas. Mol Med Rep 22(2):819–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Han W, Chu Q, Li J, Dong Z, Shi X, Fu X (2023) Modulating myofibroblastic differentiation of fibroblasts through actin-MRTF signaling axis by micropatterned surfaces for suppressed implant-induced fibrosis. Research (Washington, D.C.) 6:0049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seale P, Kajimura S, Yang W, Chin S, Rohas LM, Uldry M, Tavernier G, Langin D, Spiegelman BM (2007) Transcriptional control of brown fat determination by PRDM16. Cell Metab 6(1):38–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seale P, Bjork B, Yang W, Kajimura S, Chin S, Kuang S, Scimè A, Devarakonda S, Conroe HM, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Rudnicki MA, Beier DR, Spiegelman BM (2008) PRDM16 controls a brown fat/skeletal muscle switch. Nature 454(7207):961–967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hasegawa Y, Ikeda K, Chen Y, Alba DL, Stifler D, Shinoda K, Hosono T, Maretich P, Yang Y, Ishigaki Y, Chi J, Cohen P, Koliwad SK, Kajimura S (2018) Repression of adipose tissue fibrosis through a PRDM16-GTF2IRD1 complex improves systemic glucose homeostasis. Cell Metab 27(1):180-194.e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nam JM, Lim JE, Ha TW, Oh B, Kang JO (2020) Cardiac-specific inactivation of Prdm16 effects cardiac conduction abnormalities and cardiomyopathy-associated phenotypes. Am J Physiol. Heart Circ Physiol 318(4):H764-H777 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Cibi DM, Bi-Lin KW, Shekeran SG, Sandireddy R, Tee N, Singh A, Wu Y, Srinivasan DK, Kovalik JP, Ghosh S, Seale P, Singh MK (2020) Prdm16 deficiency leads to age-dependent cardiac hypertrophy, adverse remodeling, mitochondrial dysfunction, and heart failure. Cell Rep 33(3):108288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun B, Rouzbehani OMT, Kramer RJ, Ghosh R, Perelli RM, Atkins S, Fatahian AN, Davis K, Szulik MW, Goodman MA, Hathaway MA, Chi E, Word TA, Tunuguntla H, Denfield SW, Wehrens XHT, Whitehead KJ, Abdelnasser HY, Warren JS, Wu M, Franklin S, Boudina S, Landstrom AP (2023) Nonsense variant PRDM16-Q187X causes impaired myocardial development and TGF-β signaling resulting in noncompaction cardiomyopathy in humans and mice. Circ Heart Fail 16(12):e010351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jiang N, Yang M, Han Y, Zhao H, Sun L (2022) PRDM16 regulating adipocyte transformation and thermogenesis: a promising therapeutic target for obesity and diabetes. Front Pharmacol 13:870250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shu Q, Tan J, Ulrike VD, Zhang X, Yang J, Yang S, Hu X, He W, Luo G, Wu J (2016) Involvement of eIF6 in external mechanical stretch-mediated murine dermal fibroblast function via TGF-β1 pathway. Sci Rep 6:36075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data is included in the manuscript and/or supporting information.