Abstract

Background and Objectives

Long-term opioid therapy (LTOT) is frequently used for management of chronic noncancer pain, but its associations with increased risks of overdose and mortality have necessitated an evaluation of strategies for tapering or discontinuation. The process of opioid tapering is complex due to associated withdrawal symptoms and potential adverse outcomes. Thus, understanding tapering patterns and associated factors is vital for optimizing pain management, especially for vulnerable older adults.

Research Design and Methods

This cohort study used the 5% national sample of Medicare administrative claims data from 2012 to 2019. The study cohort consisted of individuals aged 65 and older on LTOT. The key outcomes were time until any tapering or rapid tapering of opioids. Various predictor variables, including sociodemographic and clinical factors, were examined. Survival curves were plotted, and Cox proportional hazards models were used for data analysis.

Results

The study cohort included 146,605 Medicare beneficiaries on LTOT, of which the largest percentages were aged 65–74 years (48.5%), women (68.0%), and non-Hispanic White (82.3%). Within the first year of LTOT use, nearly 1 in 2 individuals experienced any tapering, and about 1 in 4 individuals experienced rapid tapering. Presence of multiple chronic noncancer pain conditions, hepatic impairment, sleep disorders, higher baseline opioid dose, and LTOT initiation after 2016 were associated with increased rate of both any tapering and rapid tapering. The release of the 2016 CDC guideline was associated with a 45% and 64% increase in the hazards of any tapering and rapid tapering, respectively.

Discussion and Implications

This study estimated the incidence rate and predictors of opioid tapering among older adults in the United States. Combined with rates of opioid prescribing and prevalence of chronic pain, these epidemiological data are crucial for identifying and improving the safety and effectiveness of pain management among older adults.

Keywords: Cancer, Chronic noncancer pain, Long-term opioid therapy, Opioid tapering

Translational Significance: This study reported the incidence of opioid tapering among older adults on long-term opioid therapy (LTOT), emphasizing the need to understand tapering patterns and associated factors. We found that nearly half of older adults on LTOT experience opioid tapering, and more than 1 in 4 experience rapid tapering within 1 year. Factors such as high baseline opioid dose, comorbidities, presence of multiple CNCP conditions, and issuance of the 2016 CDC guideline were associated with a higher rate of tapering. Gaining thorough understanding of the incidence and factors associated with opioid tapering is imperative for optimizing pain management and mitigating risks.

Background and Objectives

Management of chronic pain, particularly among older adults, is complex and challenging. One salient tool in the management of chronic pain is the use of long-term opioid therapy (LTOT), which has been the subject of extensive focus as a result of the growing burden of the overdose epidemic in the United States (1,2). Literature estimates that around 10% of Medicare-enrolled older adults with a new opioid prescription transition to long-term use (3). Several studies have demonstrated that continued use of opioids, particularly at high doses, can result in an increased risk of adverse consequences such as overdose, or mortality (4–7). Therefore, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in the 2022 guideline for opioid prescribing, strongly recommends the frequent evaluation of the risk–benefit profile for individuals on LTOT with the goal of discontinuing opioids while maintaining control of pain and quality of life (8).

However, tapering and discontinuation of opioids is a challenging and high-risk process (9–11). Withdrawal symptoms are common in cases of opioid tapering resulting in outcomes ranging anywhere from pain catastrophizing, acute mental health crises, cardiovascular events, to risk of suicide (12–16). Engaging in a patient-driven, controlled, and closely monitored regimen for a slow tapering of opioid dose may actually be beneficial. A systematic review of 20 observational studies examining opioid dose tapering among individuals with chronic pain found consistent reports of either pain maintenance or even improvement (17). The use of a slow, patient-driven change in opioid dose is sine qua non to obtaining benefits from tapering. Glanz and colleagues found that adverse events related to opioid dose change are more likely when there is greater variability in dosage (18). Many other studies have also demonstrated the risks associated with rapid opioid dose tapering (13,19,20). As a result, the CDC 2022 guideline recommended “tapers of 10% per month or slower” in combination with patient agreement and interest in the process (8).

A retrospective study by Fenton et al. found that in 2008, 10.5% of adult LTOT users underwent dose tapering, and this percentage increased to 22.4% in 2017 (21). Stein and colleagues found that 72% of LTOT episodes among commercial insurance enrollees in 2017–2018 were rapidly discontinued, defined as a decrease in opioid morphine milligram equivalents (MME) greater than 10% per week (22). Another study among Vermont Medicaid enrollees found that more than half of LTOT users discontinued opioids without any taper (13). This concerning pattern in rapid tapering episodes may have been prompted by the CDC’s 2016 guideline for opioid prescribing that strongly discouraged the use of opioids (23,24). Given the trends in rapid discontinuation of opioids, further research on this phenomenon is warranted. Notably, there is inadequate research focusing on older adults who are on LTOT. These individuals are a particularly vulnerable group who are at higher risk of adverse consequences (20,25–27). Understanding the incidence, patterns, and factors associated with different velocities of tapering is crucial for optimizing pain management strategies, minimizing risks, and improving patient outcomes. This study aims to examine the incidence and patterns of opioid dose tapering and characteristics associated with tapering in a nationally representative dataset of older adults enrolled in Medicare fee-for-service.

Research Design and Methods

Study Design and Data Source

This cohort study utilized the 5% national sample of Medicare administrative claims data from 2012 to 2019. The Medicare administrative claims database contains healthcare services records, including inpatient claims, outpatient claims, and pharmacy claims that can be linked using an encrypted beneficiary identifier. Individual enrollment records and demographic characteristics were identified using a beneficiary summary file. The study was approved by the University of Mississippi Institutional Review Board and the use of Medicare data was allowed under an existing data use agreement with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (RSCH-2018-52319). This manuscript followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort studies.

Study Cohort

Medicare beneficiaries who were on LTOT between October 1, 2012, and December 31, 2018, were included in the study. LTOT was defined, as per the previous literature, as the presence of at least 3 opioid prescription claims with a cumulative 45-day supply in any 90-day period during LTOT identification period (3,4,28). The 91st day after the first occurrence of LTOT was defined as the “cohort entry date” and denoted the start of the follow-up for eligible individuals. In order to be eligible, individuals were required to be at least 65 years or older as of the cohort entry date and were required to be continuously enrolled in Medicare Parts A, B, D and no enrollment in Medicare Part C for at least 9 months prior to cohort entry and 2 months after cohort entry. Continuous enrollment was required in order to capture key study variables in the study period before cohort entry and to allow adequate time to identify the study outcome during follow-up. Individuals receiving hospice care during the 6 months prior to the cohort entry date were also excluded from the study. Eligible individuals were followed starting from 2 months after cohort entry date until the first occurrence of opioid tapering, the study outcome. During follow-up, data were censored at the date of death, loss of continuous Medicare fee-for-service eligibility, start of Medicare Part C enrollment, receiving hospice care, or the end of the study period (December 31, 2019), whichever occurred first.

Study Outcomes

The key outcome in this study was the occurrence of an opioid tapering episode, which was further categorized as “any tapering” or “rapid tapering,” based on the velocity of the change in the opioid dose. The operationalization of these 2 tapering events was based on the estimation of the velocity of opioid tapering, defined in previous research (21). Velocity of opioid tapering was estimated using the formula:

where B is the average baseline opioid dose, T is the average tapered daily dose during a given 60-day window in the follow-up period, and D is the time in months from the most recent month at the baseline dose to the earliest month at the tapered dose (21).

This formula yields an approximation of the monthly percent dose reduction, with higher numbers indicating greater rapidity of tapering. The average baseline dose (B) was calculated based on the average MME during the 90-day baseline period at the initiation of LTOT. During follow-up, the average tapered daily dose (T) was calculated for each 60-day window from the cohort entry date until the end of the follow-up period. Consecutive 60-day windows during the follow-up overlapped by 30 days, as originally proposed by Fenton and colleagues, in order to smooth the average dose estimation and allow for some variability in dose and continuity of opioid use (21). This smoothing was also critical given known limitations in estimation of average opioid dosage using claims data (21). The opioid tapering velocity (V) was calculated for each 60-day period in the follow-up, using the number of months between a given follow-up period and the most recent month at baseline dose as the time (D). Based on the CDC’s 2016 guidelines, an individual was said to be tapering during any given period if the tapering velocity for that period was greater than 10% (23). If the tapering velocity was estimated to be greater than 40%, the individual was classified as being rapidly tapered. For each eligible Medicare enrollee, the occurrence of rapid tapering and any tapering were identified, and the time to the first occurrence of each event was estimated as the time in months from cohort entry date until the middle of the given 60-day follow-up period where the event was identified.

Predictor Variables

Sociodemographic variables such as age, sex, race, and poverty level, as measured by enrollment in the low-income subsidy (LIS) program, were included in the study as predictors. In addition, clinical factors such as the presence of multiple chronic noncancer pain conditions, Parkinson’s disease, renal insufficiency, hepatic insufficiency, substance use disorder, other mental illnesses, COPD, sleep disorders, cancer, history of opioid overdose, and the Deyo–Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) were included (29). Clinical conditions of interest were assessed during the period prior to cohort entry date. Individuals were also assessed for the use of concomitant medications, evaluated by examining whether they had at least 90 days of cumulative supply during LTOT baseline period for the following medications: anticonvulsants, antidepressants, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics, and skeletal muscle relaxants. The average baseline opioid dose during the 90-day baseline period was also included as a predictor. Finally, in order to assess the impact of the 2016 CDC guideline, the year of an individual’s cohort entry was included as a predictor, with 2016 (the year of the issuance of the guideline) set as the reference category in the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics of the study cohort. Appropriate bivariate tests of significance were conducted to compare individuals who experienced any tapering or rapid tapering to those who did not experience any tapering. The unadjusted incidence rates of any tapering and rapid tapering in the study cohort were estimated as the number of events per person per month of follow-up. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to plot survival curves for the study cohort. The rate of experiencing the outcome event of interest was modeled using a Cox proportional hazards model. Two separate Cox models were run to predict rate of any tapering as well as the rate of rapid tapering, where “any tapering” and “rapid tapering” were treated as independent outcomes. Individuals who experienced “nonrapid tapering” (tapering velocity greater than 10% and less than 40%) remained at risk for “rapid tapering” and were not censored in the rapid tapering model.

The initial models included year of cohort entry (ie, LTOT initiation year) as an approach to assess the potential effect of the 2016 CDC opioid prescribing guideline on both any tapering as well as rapid tapering. The year of cohort entry was used as the predictor variable of interest in these analyses. To evaluate whether the operationalization of this variable had any meaningful impact on the results regarding the estimate of the potential impact of this guideline, a sensitivity analysis was conducted using a time-varying variable. These sensitivity analyses included a time-varying variable that flagged each follow-up period as occurring either before or after the CDC’s original guideline, which was issued in March of 2016, thereby estimating the impact of the guideline on the hazard of the outcome in the Cox model. Additionally, we conducted 3 further sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of the primary findings. First, we excluded individuals with dual eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid at baseline and censored dual-eligible individuals during the follow-up period. Second, we conducted a subgroup analysis among individuals with baseline opioid doses >50 MME. And third, we conducted a sensitivity analysis that censored individuals who had an opioid use gap of greater than 90 consecutive days during follow-up (opioid discontinuation cohort). All data management and analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

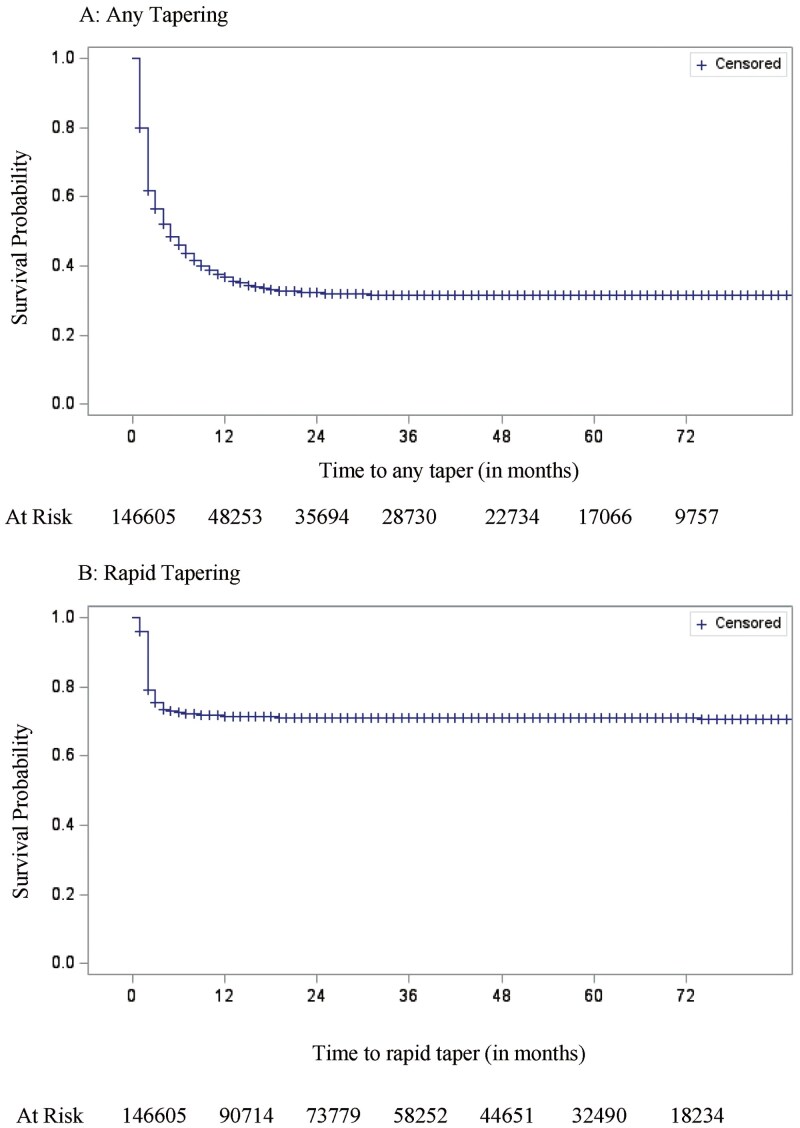

After implementing the study eligibility criteria, a total of 146,605 Medicare beneficiaries were found to be on LTOT. About half the study cohort (48.5%) was between 65 and 74 years of age, and a majority were women (68.0%) and non-Hispanic White (82.3%). About 40% of the study cohort was enrolled in the LIS program (39.4%) and 41.7% had a CCI score of 1 or 2. Entry into the study cohort was more common in 2012 and 2014 (20.9%), followed by 2013 (16.6%). Nearly half of the study cohort had a baseline average MME between 20 and 50 (45.1%), whereas 37.6% had an average MME less than 20, and 17.3% had an average MME greater than or equal to 50. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study cohort are presented in Table 1. Among all individuals who were on LTOT, 66.2% (N = 97,050) experienced a tapering event and 28.7% (N = 42,054) experienced a rapid tapering event. The average time to any tapering and rapid tapering was 27.51 (SE = 0.093) months and 56.09 (SE = 0.09) months, respectively. The survival curves depicting the incidence of any tapering and rapid tapering are shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Cohort

| Full Cohort | Any Tapering | No Tapering | p | Rapid Tapering | No Rapid Tapering* | p | |

| N = 146,605 | n = 97,050 | n = 49,555 | n = 42,054 | n = 104,551 | |||

| Age mean (SD) | 76.3 (8.1) | 76.2 (7.9) | 76.6 (8.4) | <.001 | 75.8 (7.7) | 76.5 (8.2) | <.001 |

| 65–74 years | 71,146 (48.53%) | 47,388 (66.61%) | 23,758 (33.39%) | 21,305 (29.95%) | 49,841 (70.05%) | ||

| 75–84 years | 48,398 (33.01%) | 32,735 (67.64%) | 15,663 (32.36%) | 14,054 (29.04%) | 34,344 (70.96%) | ||

| 85 years and above | 27,061 (18.46%) | 16,927 (62.55%) | 10,134 (37.45%) | 6,695 (24.74%) | 20,366 (75.26%) | ||

| Sex | <.001 | <.001 | |||||

| Male | 46,976 (32.04%) | 31,627 (67.33%) | 15,349 (32.67%) | 14,377 (30.60%) | 32,599 (69.40%) | ||

| Female | 99,629 (67.96%) | 65,423 (65.67%) | 34,206 (34.33%) | 27,677 (27.78%) | 71,952 (72.22%) | ||

| Race | <.001 | <.001 | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 120,661 (82.30%) | 79,434 (65.83%) | 41,227 (34.17%) | 34,618 (28.69%) | 86,043 (71.31%) | ||

| Black | 13,207 (9.01%) | 8,624 (65.3%) | 4,583 (34.7%) | 3,488 (26.41%) | 9,719 (73.59%) | ||

| Hispanic | 8,110 (5.53%) | 5,661 (69.8%) | 2,449 (30.2%) | 2,410 (29.72%) | 5,700 (70.28%) | ||

| Other racial groups | 4,627 (3.16%) | 3,331 (71.99%) | 1,296 (28.01%) | 1,538 (33.24%) | 3,089 (66.76%) | ||

| LIS enrollment | <.001 | <.001 | |||||

| Yes | 57,832 (39.45%) | 34,686 (59.98%) | 23,146 (40.02%) | 13,217 (22.85%) | 44,615 (77.15%) | ||

| No | 88,773 (60.55%) | 62,364 (70.25%) | 26,409 (29.75%) | 28,837 (32.48%) | 59,936 (67.52%) | ||

| LTOT initiation year | <.001 | <.001 | |||||

| 2012 | 30,592 (20.87%) | 11,205 (61.4%) | 7,031 (38.6%) | 4,809 (15.72%) | 25,783 (84.28%) | ||

| 2013 | 24,302 (16.58%) | 12,224 (76.1%) | 3,844 (23.9%) | 6,844 (28.16%) | 17,458 (71.84%) | ||

| 2014 | 30,636 (20.90%) | 15,911 (73.0%) | 5,881 (27.0%) | 7,869 (25.69%) | 22,767 (74.31%) | ||

| 2015 | 21,466 (14.64%) | 13,162 (77.6%) | 3,794 (22.4%) | 6,667 (31.06%) | 14,799 (68.94%) | ||

| 2016 | 15,972 (10.89%) | 10,764 (83.0%) | 2,199 (17.0%) | 5,881 (36.82%) | 10,091 (63.18%) | ||

| 2017 | 13,245 (9.03%) | 9,117 (83.6%) | 1,786 (16.4%) | 5,085 (38.39%) | 8,160 (61.61%) | ||

| 2018 | 10,392 (7.09%) | 4,901 (66.7%) | 2,448 (33.3%) | 4,899 (47.14%) | 5,493 (52.86%) | ||

| Multiple CNCP | <.001 | <.001 | |||||

| Yes | 49,396 (33.69%) | 78,022 (68.85%) | 35,306 (31.15%) | 15,113 (30.60%) | 34,283 (69.40%) | ||

| No | 97,209 (66.31%) | 19,028 (57.18%) | 14,249 (42.82%) | 26,941 (27.71%) | 70,268 (72.29%) | ||

| Renal impairment | <.001 | .019 | |||||

| Yes | 35,837 (24.44%) | 24,636 (68.74%) | 11,201 (31.26%) | 10,454 (29.17%) | 25,383 (70.83%) | ||

| No | 110,768 (75.56%) | 72,414 (65.37%) | 38,354 (34.63%) | 31,600 (28.53%) | 79,168 (71.47%) | ||

| Hepatic impairment | <.001 | <.001 | |||||

| Yes | 10,063 (6.86%) | 7,167 (71.22%) | 2,896 (28.78%) | 3,265 (32.45%) | 6,798 (67.55%) | ||

| No | 136,542 (93.14%) | 89,883 (65.83%) | 46,659 (34.17%) | 38,789 (28.41%) | 97,753 (71.59%) | ||

| Substance use disorder or substance abuse | <.001 | <.001 | |||||

| Yes | 56,819 (38.76%) | 39,505 (69.53%) | 17,314 (30.47%) | 17,885 (31.48%) | 38,934 (68.52%) | ||

| No | 89,786 (61.24%) | 57,545 (64.09%) | 32,241 (35.91%) | 24,169 (26.92%) | 65,617 (73.08%) | ||

| Sleep disorders | <.001 | <.001 | |||||

| Yes | 55,278 (37.71%) | 38,740 (70.08%) | 16,538 (29.92%) | 17,166 (31.05%) | 38,112 (68.95%) | ||

| No | 91,327 (62.29%) | 58,310 (63.85%) | 33,017 (36.15%) | 24,888 (27.25%) | 66,439 (72.75%) | ||

| Parkinson | .043 | .025 | |||||

| Yes | 4,633 (3.16%) | 3,131 (67.58%) | 1,502 (32.42%) | 1,261 (27.22%) | 3,372 (72.78%) | ||

| No | 141,972 (96.84%) | 93,919 (66.15%) | 48,053 (33.85%) | 40,793 (28.73%) | 101,179 (71.27%) | ||

| Mental disorder | .023 | <.001 | |||||

| Yes | 44,451 (30.32%) | 42,185 (63.46%) | 24,285 (36.54%) | 11,950 (26.88%) | 32,501 (73.12%) | ||

| No | 102,154 (69.68%) | 54,865 (68.47%) | 25,270 (31.53%) | 30,104 (29.47%) | 72,050 (70.53%) | ||

| COPD | <.001 | <.001 | |||||

| Yes | 47,419 (32.34%) | 30,441 (64.2%) | 16,978 (35.8%) | 12,554 (26.47%) | 34,865 (73.53%) | ||

| No | 99,186 (67.66%) | 66,609 (67.16%) | 32,577 (32.84%) | 29,500 (29.74%) | 69,686 (70.26%) | ||

| Opioid overdose | .652 | .452 | |||||

| Yes | 454 (0.31%) | 296 (65.2%) | 158 (34.8%) | 123 (27.09%) | 331 (72.91%) | ||

| No | 146,151 (99.69%) | 96,754 (66.2%) | 49,397 (33.8%) | 41,931 (28.69%) | 104,220 (71.31%) | ||

| History of cancer | <.001 | <.001 | |||||

| Yes | 17,115 (16.4%) | 13,486 (78.8%) | 3,629 (21.2%) | 6,723 (26.94%) | 18,234 (73.06%) | ||

| No | 87,152 (83.6%) | 63,798 (73.2%) | 23,354 (26.8%) | 35,331 (29.04%) | 86,317 (70.96%) | ||

| Concomitant medication use | <.001 | <.001 | |||||

| Yes | 66,470 (45.34%) | 32,053 (71.9%) | 12,545 (28.1%) | 16,914 (25.45%) | 49,556 (74.55%) | ||

| No | 80,135 (54.66%) | 45,231 (75.8%) | 14,438 (24.2%) | 25,140 (31.37%) | 54,995 (68.63%) | ||

| CCI | <.001 | <.001 | |||||

| 0 | 56,780 (38.73%) | 36,213 (63.78%) | 20,567 (36.22%) | 15,659 (27.58%) | 41,121 (72.42%) | ||

| 1–2 | 61,208 (41.75%) | 40,002 (65.35%) | 21,206 (34.65%) | 17,025 (27.81%) | 44,183 (72.19%) | ||

| ≥3 | 28,617 (19.52%) | 20,835 (72.81%) | 7,782 (27.19%) | 9,370 (32.74%) | 19,247 (67.26%) | ||

| Baseline opioid mean daily dose (MME) | <.001 | <.001 | |||||

| <20 | 55,138 (37.61%) | 35,091 (63.64%) | 20,047 (36.36%) | 12,407 (22.50%) | 42,731 (77.50%) | ||

| 20–50 | 66,105 (45.09%) | 45,817 (69.31%) | 20,288 (30.69%) | 21,719 (32.86%) | 44,386 (67.14%) | ||

| ≥50 | 25,362 (17.30%) | 16,142 (63.65%) | 9,220 (36.35%) | 7,928 (31.26%) | 17,434 (68.74%) |

Notes: SD = standard deviation, LIS = low-income subsidy, LTOT = long-term opioid therapy, CNCP = chronic noncancer pain, COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CCI = Deyo–Charlson comorbidity index, MME = morphine milligram equivalents.

*No rapid tapering includes nonrapid tapering and no tapering.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves showing the survival rates of any opioid tapering and rapid opioid tapering.

The incidence rate of experiencing any tapering was 3.8 per 100 person-months and the incidence rate for rapid tapering events was 0.9 per 100 person-months. State-level crude incidence rates of any tapering and rapid tapering are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Based on the Kaplan–Meier survival curves, we observed that within the first year of LTOT use, nearly 1 in 2 individuals experienced any tapering and about 1 in 4 individuals experienced rapid tapering. Bivariate tests of significance for various demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Key among these findings is that individuals who were older were less likely to experience any tapering (Mean [SD]: 76.2 [7.9] vs 76.6 [8.4]; p < .001) and rapid tapering (Mean [SD]: 75.8 [7.7] vs 76.5 [8.2]; p < .001). Men were more likely to experience both any tapering (67.3% vs 65.7%; p < .001) and rapid tapering (30.6% vs 27.8%; p < .001) compared to women, whereas individuals enrolled in LIS were less likely to experience any tapering (60.0% vs 70.3%; p < .001) and rapid tapering (22.9% vs 32.5%; p < .001). Individuals with more comorbidities were significantly more likely to experience any tapering (CCI = 0: 63.8%; CCI = 1–2: 65.4%; CCI ≥3: 72.8%; p < .001) and rapid tapering (CCI = 0: 27.6%; CCI = 1–2: 27.8%; CCI ≥3: 32.7%; p < .001). Individuals who had a baseline average opioid dose between 20 and 50 MME were also more likely to experience any tapering (MME <20: 63.6%; MME = 20–50: 69.3%; MME ≥50: 63.7%; p < .001) as well as rapid tapering (MME <20: 22.5%; MME = 20–50: 32.9%; MME ≥50: 31.3%; p < .001).

Tables 2 and 3 show the results of the Cox proportional hazards model predicting the hazard of any tapering as well as rapid tapering. After adjusting for all the other variables in the model, individuals who were 75–84 years old (HR = 1.04 [CI: 1.02–1.05]) were more likely to experience any tapering compared to individuals who were 65–74 years old. Women were significantly more likely to experience any tapering (HR = 1.04 [CI: 1.03–1.06]), whereas those using concomitant medications were less likely to experience any tapering (HR = 0.89 [CI: 0.88–0.90]) and rapid tapering (HR = 0.81 [CI: 0.79–0.83]). Hispanic individuals were more likely to be tapered (HR = 1.23 [CI: 1.20–1.26]) and rapid tapered (HR = 1.26 [1.21–1.31]) compared to non-Hispanic Whites. When using 2016 as the reference year, individuals who initiated LTOT in prior years were less likely to experience tapering and those who initiated LTOT after 2016 were more likely to experience tapering. For example, those initiating LTOT in 2012 had 51% (HR = 0.49 [CI: 0.48–0.51]) and 65% (HR = 0.35 [CI: 0.33–0.36]) lower hazard of experiencing any tapering and rapid tapering, respectively (relative to 2016), whereas those initiating LTOT in 2018 had 51% (HR = 1.51 [CI: 1.47–1.56]) and 40% (HR = 1.40 [CI: 1.35–1.46]) greater hazard of any tapering and rapid tapering, respectively (relative to 2016). Sensitivity analyses conducted using a time-varying variable to capture the CDC’s release of the opioid prescribing guidelines in 2016 were consistent with this finding (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). Results show that the release of the 2016 CDC guideline was associated with a 45% (HR = 1.45 [CI: 1.43–1.47]) and 64% (HR = 1.64 [CI: 1.61–1.68]) increase in the hazard of any tapering and rapid tapering, respectively. Among other interesting predictors, those enrolled in LIS and with lower baseline opioid dose were less likely to be tapered. These findings were also consistent with rapid tapering for these groups. Results from other sensitivity analyses were also consistent with our primary findings and reported in Supplementary Tables 4 through 7 and Supplementary Figures 1 and 2.

Table 2.

Predictors of Any Tapering among Older Adults on Long-term Opioid Therapy

| Patient Characteristics | Any Tapering | |

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p | |

| Age | ||

| 65–74 years | Reference | |

| 75–84 years | 1.04 (1.02–1.05) | <.001 |

| 85 years and above | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | .153 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1.04 (1.03–1.06) | <.001 |

| Race | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | Reference | |

| Black | 1.05 (1.03–1.08) | <.001 |

| Hispanic | 1.23 (1.20–1.26) | <.001 |

| Other racial groups | 1.21 (1.17–1.26) | <.001 |

| LIS enrollment | ||

| Yes | 0.82 (0.81–0.83) | <.001 |

| LTOT year | ||

| 2012 | 0.49 (0.48–0.51) | <.001 |

| 2013 | 0.79 (0.77–0.81) | <.001 |

| 2014 | 0.74 (0.72–0.76) | <.001 |

| 2015 | 0.84 (0.82–0.86) | <.001 |

| 2016 | Reference | |

| 2017 | 1.09 (1.06–1.12) | <.001 |

| 2018 | 1.51 (1.47–1.56) | <.001 |

| Multiple CNCP | 1.10 (1.08–1.11) | <.001 |

| Renal impairment | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | .004 |

| Hepatic impairment | 1.09 (1.06–1.11) | <.001 |

| Substance use disorder or substance abuse | 1.06 (1.04–1.07) | <.001 |

| Sleep disorders | 1.06 (1.04–1.07) | <.001 |

| Parkinson’s disease | 1.07 (1.03–1.11) | <.001 |

| Mental disorder | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | <.001 |

| COPD | 0.93 (0.91–0.95) | <.001 |

| Opioid overdose | 1.02 (0.91–1.15) | .711 |

| History of cancer | 0.86 (0.85–0.88) | <.001 |

| Concomitant medication use | 0.89 (0.88–0.90) | <.001 |

| CCI | ||

| 0 | Reference | |

| 1 or 2 | 1.03 (1.01–1.04) | <.001 |

| ≥3 | 1.07 (1.05–1.10) | <.001 |

| Baseline opioid mean daily dose (MME) | ||

| <20 | Reference | |

| 20–50 | 1.24 (1.22–1.26) | <.001 |

| ≥50 | 1.39 (1.36–1.42) | <.001 |

Notes: CI = confidence interval, LIS = low-income subsidy, LTOT = long-term opioid therapy, CNCP = chronic noncancer pain, COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CCI = Deyo–Charlson comorbidity index, MME = morphine milligram equivalents.

Table 3.

Predictors of Rapid Tapering Among Older Adults on Long-term Opioid Therapy

| Patient Characteristics | Rapid Tapering | |

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p | |

| Age | ||

| 65–74 years | Reference | |

| 75–84 years | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) | .986 |

| 85 years and above | 0.91 (0.89–0.94) | <.001 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) | .152 |

| Race | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | Reference | |

| Black | 1.03 (0.99–1.07) | .150 |

| Hispanic | 1.26 (1.21–1.31) | <.001 |

| Other racial groups | 1.27 (1.21–1.34) | <.001 |

| LIS enrollment | ||

| Yes | 0.76 (0.74–0.78) | <.001 |

| LTOT year | ||

| 2012 | 0.35 (0.33–0.36) | <.001 |

| 2013 | 0.72 (0.69–0.74) | <.001 |

| 2014 | 0.66 (0.64–0.68) | <.001 |

| 2015 | 0.81 (0.78–0.84) | <.001 |

| 2016 | Reference | |

| 2017 | 1.07 (1.03–1.11) | <.001 |

| 2018 | 1.40 (1.35–1.46) | <.001 |

| Multiple CNCP | 1.03 (1.01–1.06) | .001 |

| Renal impairment | 0.99 (0.96–1.01) | .208 |

| Hepatic impairment | 1.07 (1.03–1.11) | <.001 |

| Substance use disorder or substance abuse | 1.05 (1.03–1.07) | <.001 |

| Sleep disorders | 1.05 (1.03–1.07) | <.001 |

| Parkinson’s disease | 1.03 (0.97–1.09) | .364 |

| Mental disorder | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | .937 |

| COPD | 0.92 (0.90–0.94) | <.001 |

| Opioid overdose | 1.04 (0.87–1.24) | .670 |

| History of cancer | 0.82 (0.79–0.84) | <.001 |

| Concomitant medication use | 0.81 (0.79–0.83) | <.001 |

| CCI | ||

| 0 | Reference | |

| 1 or 2 | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | .773 |

| ≥3 | 1.02 (0.99–1.05) | .290 |

| Baseline opioid mean daily dose (MME) | ||

| <20 | Reference | |

| 20–50 | 1.66 (1.62–1.69) | <.001 |

| ≥50 | 2.07 (2.01–2.14) | <.001 |

Notes: CI = confidence interval, LIS = low-income subsidy, LTOT = long-term opioid therapy, CNCP = chronic noncancer pain, COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CCI = Deyo–Charlson comorbidity index, MME = morphine milligram equivalents.

Discussion and Implications

This study examined the incidence of tapering from LTOT among Medicare fee-for-service enrollees across the United States. The findings present novel information about the evolving trends in opioid prescribing patterns among older adults and key insights on the factors driving these patterns. Importantly, this study also examined the velocity of opioid dose tapering, allowing for identification of tapering patterns that are more aligned with current guidelines versus those that may expose patients to high risks of serious adverse reactions.

The primary finding of this study was that nearly 1 in 2 older adults on LTOT are tapered from opioid therapy within 1 year, and about 1 in 4 are tapered at a very high velocity. It is important to note these estimates of incidence rates do not account for the possibility of repeat occurrences of tapering in the same individual (ie, this study only captured the first occurrence of tapering) and are therefore likely an underestimate of the true rate. However, the incidence proportion or cumulative incidence presented in these findings are unaffected by repeated events. Further, the annual estimation of the incidence of tapering allows the findings to be more easily interpreted and contextualized. Together with annual rates of incidence of chronic pain and LTOT, this can present a complete epidemiological picture of chronic pain management.

Previous research examining all adults over the age of 18 years found that age and sex-adjusted incidence rate of tapering ranged from 12.7% in 2008 to 23.1% in 2017 (21). Stein and colleagues estimated that 72% of all high-dose LTOT treatment episodes were rapidly discontinued among adults on commercial insurance (22). Buonora and colleagues found that 42.2% of individuals at a hospital outpatient setting experienced ≥30% dose reduction within 2 years (30). However, none of these results are directly comparable with the current study due to the significant degree of variability in operational definitions of tapering as well as study sample characteristics. For example, Fenton and colleagues identified an event as a tapering episode if the velocity of dose reduction was greater than 15% (21), but did not classify any rapid tapering episodes, whereas Stein and colleagues defined rapid tapering as greater than 10% dose reduction per week (22). Further, previous research did not adequately distinguish between different velocities of opioid dose tapering, which is an important distinction for avoidance of adverse consequences (13,19,20).

This study also found key individual characteristics that predict rate of tapering. Many of the key findings such as the impact of patient sex were consistent with the existing literature exploring predictors of tapering (21,22). For example, individuals who had a higher average baseline opioid dose were found to be more likely to have tapered their dose, both in this study and in previous research (21), possibly driven by a greater recognition of the need for tapering and the changing risk-benefit profile of LTOT among individuals on higher dosages. This study substantiated the finding from Fenton and colleagues that individuals with more comorbidities were more likely to experience tapering (21). This impact of comorbidity burden on velocity of dose reduction is perhaps driven by an increased caution in dose change as well as changes in tolerance to the tapering regimen. Another key finding is the confirmation of annual trends in the incidence rate of opioid dose tapering (21,31,32), with a notable change in incidence rates during 2016–17, aligned with the release of the CDC’s original guideline for prescribing of opioids in 2016 (23). This finding was also consistent in our sensitivity analyses, which accounted not only for the year during which LTOT was initiated but also the effect of the release of the guideline on individuals who were already on LTOT prior to March 2016.

Previous research as well as the CDC’s revised guideline for prescribing opioids in 2022 warns about the prevalence and increased risks of overdose due to concomitant prescribing of opioids with other psychotropic medications (8,33–36). However, the impact of concomitant prescribing appears to be rather nuanced. Fenton and colleagues found that being coprescribed benzodiazepines was not related to tapering (21). However, this study found that concomitant use of any psychotropic medication was protective against both tapering and rapid tapering. The impact of a concomitant prescription on both patient outcomes, as well as willingness to taper opioids, is worthy of further investigation. Finally, individuals who were Hispanic had a greater hazard of tapering compared to non-Hispanic White individuals. This finding is in line with prior research showing that providers are less willing to prescribe opioids to minorities, resulting in significant disparities in burden resulting from chronic pain (30,37–39). These disparities in prescribing patterns are critical for addressing health outcomes but are understudied. Future research should explore trends in opioid prescribing across various racial and ethnic groups as well as the impact of these disparities on health outcomes.

This study’s findings should be interpreted in light of some key limitations. First, it is important to note that interpretations of findings regarding tapering presented in this study must be distinct from opioid discontinuation (40). While this study examined opioid discontinuation within the context of dose reduction it did not specifically examine whether opioids were completely discontinued. Second, presence of a tapering event does not indicate that the tapering regimen itself was beneficial for the patient. A plethora of existing research demonstrates that patients may experience serious and fatal adverse consequences as a result of tapering. Identifying indicators of whether the tapering regimen was successful was outside the scope of this study. Third, accurate estimation of average opioid dosage using claims data is prone to errors (21). However, the operationalization of monthly average doses, as well as the velocity of dose change has been used repeatedly in previous research demonstrating reliable and theory-consistent findings (20,21). Furthermore, understanding the role that specific providers play in initiating opioid tapering is crucial. However, patients may have multiple opioid claims from different providers on or near the same date, making it nearly impossible to determine which provider initiated opioid dose reduction.

Finally, caution must be exercised before generalizing these findings to individuals of younger age groups, or even other older adults enrolled in the Medicare Advantage program.

Conclusions

This study found that nearly 1 in 2 older adults on LTOT experience tapering of opioid dose, and 1 in 4 experience rapid rates of dose tapering within the first year. Individual characteristics such as higher average baseline dose, greater comorbidity burden, and belonging to a minority racial/ethnic group as well as policy characteristics such as the release of the CDC’s opioid prescribing guidelines in 2016 were found to be associated with a greater rate of opioid dose tapering. An increase in focus on identifying and carrying out interventions for individuals who are more likely to experience rapid tapering can help prevent adverse consequences associated with tapering among individuals with chronic pain.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Sujith Ramachandran, Department of Pharmacy Administration, School of Pharmacy, University of Mississippi, University, Mississippi, USA; Center for Pharmaceutical Marketing & Management, School of Pharmacy, University of Mississippi, University, Mississippi, USA.

Shishir Maharjan, Department of Pharmacy Administration, School of Pharmacy, University of Mississippi, University, Mississippi, USA.

Liang-Yuan Lin, Department of Pharmacy Administration, School of Pharmacy, University of Mississippi, University, Mississippi, USA.

John P Bentley, Department of Pharmacy Administration, School of Pharmacy, University of Mississippi, University, Mississippi, USA; Center for Pharmaceutical Marketing & Management, School of Pharmacy, University of Mississippi, University, Mississippi, USA.

Gerald McGwin, School of Public Health, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Ike Eriator, School of Medicine, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, Mississippi, USA.

Kaustuv Bhattacharya, Department of Pharmacy Administration, School of Pharmacy, University of Mississippi, University, Mississippi, USA; Center for Pharmaceutical Marketing & Management, School of Pharmacy, University of Mississippi, University, Mississippi, USA.

Yi Yang, Department of Pharmacy Administration, School of Pharmacy, University of Mississippi, University, Mississippi, USA; Center for Pharmaceutical Marketing & Management, School of Pharmacy, University of Mississippi, University, Mississippi, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse [grant number R15DA046036-02 to Y.Y.]. The sponsor had no role in any aspect of design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, and preparation of the paper.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Data Availability

Our analytic methods or coding are available to other researchers upon request. However, the original data used in this study cannot be shared by the investigators, but are available to be licensed from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. This study was not preregistered.

References

- 1. Karmali RN, Bush C, Raman SR, Campbell CI, Skinner AC, Roberts AW.. Long-term opioid therapy definitions and predictors: A systematic review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2020;29(3):252–269 https://doi.org/ 10.1002/pds.4929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, et al. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: A systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(4):276–286 https://doi.org/ 10.7326/M14-2559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ramachandran S, Salkar M, Bentley JP, Eriator I, Yang Y.. Patterns of long-term prescription opioid use among older adults in the United States: A study of Medicare administrative claims data. Pain Physician. 2021;24(1):31–40. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Salkar M, Ramachandran S, Bentley JP, et al. Do formulation and dose of long-term opioid therapy contribute to risk of adverse events among older adults? J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(2):367–374 https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s11606-021-06792-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, et al. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(2):85–92 https://doi.org/ 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li L, Setoguchi S, Cabral H, Jick S.. Opioid use for noncancer pain and risk of myocardial infarction amongst adults. J Intern Med. 2013;273(5):511–526 https://doi.org/ 10.1111/joim.12035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hoffman EM, Watson JC, St Sauver J, Staff NP, Klein CJ.. Association of long-term opioid therapy with functional status, adverse outcomes, and mortality among patients with polyneuropathy. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(7):773–779 https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.0486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dowell D, Ragan KR, Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Chou R.. CDC clinical practice guideline for prescribing opioids for pain—United States, 2022. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022;71. https://doi.org/ 10.15585/mmwr.rr7103a11–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Matthias MS, Johnson NL, Shields CG, et al. “I’m not gonna pull the rug out from under you”: Patient–provider communication about opioid tapering. J Pain. 2017;18(11):1365–1373 https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jpain.2017.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Perez HR, Buonora M, Cunningham CO, Heo M, Starrels JL.. Opioid taper is associated with subsequent termination of care: A retrospective cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(1):36–42 https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s11606-019-05227-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kuntz JL, Dickerson JF, Schneider JL, et al. Factors associated with opioid-tapering success: A mixed methods study. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2021;61(3):248–257.e1. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.japh.2020.12.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Demidenko MI, Dobscha SK, Morasco BJ, Meath THA, Ilgen MA, Lovejoy TI.. Suicidal ideation and suicidal self-directed violence following clinician-initiated prescription opioid discontinuation among long-term opioid users. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;47:29–35. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mark TL, Parish W.. Opioid medication discontinuation and risk of adverse opioid-related health care events. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;103:58–63. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gordon KS, Manhapra A, Crystal S, et al. All-cause mortality among males living with and without HIV initiating long-term opioid therapy, and its association with opioid dose, opioid interruption and other factors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;216:108291. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. James JR, Scott JM, Klein JW, et al. Mortality after discontinuation of primary care-based chronic opioid therapy for pain: A retrospective cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(12):2749–2755 https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s11606-019-05301-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. FDA Drug Safety Communication. FDA 2019. FDA identifies harm reported from sudden discontinuation of opioid pain medicines and requires label changes to guide prescribers on gradual, individualized tapering. Accessed February 28, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-identifies-harm-reported-sudden-discontinuation-opioid-pain-medicines-and-requires-label-changes. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fishbain DA, Pulikal A.. Does opioid tapering in chronic pain patients result in improved pain or same pain vs increased pain at taper completion? A structured evidence-based systematic review. Pain Med. 2019;20(11):2179–2197 https://doi.org/ 10.1093/pm/pny231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Glanz JM, Binswanger IA, Shetterly SM, Narwaney KJ, Xu S.. Association between opioid dose variability and opioid overdose among adults prescribed long-term opioid therapy. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(4):e192613 https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Agnoli A, Xing G, Tancredi DJ, Magnan E, Jerant A, Fenton JJ.. Association of dose tapering with overdose or mental health crisis among patients prescribed long-term opioids. JAMA. 2021;326(5):411–419 https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jama.2021.11013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Maharjan S, Ramachandran S, Bhattacharya K, et al. Opioid tapering and mental health crisis in older adults. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug saf. 2024;33(1):e5698. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/pds.5698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fenton JJ, Agnoli AL, Xing G, et al. Trends and rapidity of dose tapering among patients prescribed long-term opioid therapy, 2008–2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1916271 https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.16271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stein BD, Sherry TB, O’Neill B, Taylor EA, Sorbero M.. Rapid discontinuation of chronic, high-dose opioid treatment for pain: Prevalence and associated factors. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(7):1603–1609 https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s11606-021-07119-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain — United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65(No. RR-1):1–49. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dowell D, Haegerich T, Chou R.. No shortcuts to safer opioid prescribing. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2285–2287 https://doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMp1904190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wei YJJ, Chen C, Schmidt SO, LoCiganic WH, Winterstein AG.. Trends in prior receipt of prescription opioid or adjuvant analgesics among patients with incident opioid use disorder or opioid-related overdose from 2006 to 2016. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;204:107600. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. West NA, Dart RC.. Prescription opioid exposures and adverse outcomes among older adults. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25(5):539–544 https://doi.org/ 10.1002/pds.3934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Huhn AS, Strain EC, Tompkins DA, Dunn KE.. A hidden aspect of the U.S. opioid crisis: Rise in first-time treatment admissions for older adults with opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;193:142–147. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ramachandran S, Salkar M, Bhattacharya K, et al. Continuity of opioid prescribing among older adults on long-term opioids. Am J Manag Care. 2023;29(2):88–94 https://doi.org/ 10.37765/ajmc.2023.89317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA.. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–619 https://doi.org/ 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Buonora M, Perez HR, Heo M, Cunningham CO, Starrels JL.. Race and gender are associated with opioid dose reduction among patients on chronic opioid therapy. Pain Med. 2019;20(8):1519–1527 https://doi.org/ 10.1093/pm/pny137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Encinosa W, Bernard D, Selden TM. .Opioid and non-opioid analgesic prescribing before and after the CDC’s 2016 opioid guideline. Int J Health Econ Manag. 2022;22(1):1–52 https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10754-021-09307-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mazurenko O, Gupta S, Blackburn J, Simon K, Harle CA.. Long-term opioid therapy tapering: Trends from 2014 to 2018 in a Midwestern State. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;228:109108. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hernandez I, He M, Brooks MM, Zhang Y.. Exposure-response association between concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use and risk of opioid-related overdose in Medicare part D beneficiaries. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(2):e180919 https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li Y, Delcher C, Wei YJJ, et al. Risk of opioid overdose associated with concomitant use of opioids and skeletal muscle relaxants: A population-based cohort study. Clin Pharmacol Therap. 2020;108(1):81–89. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/cpt.1807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Le TT, Park S, Choi M, Wijesinha M, Khokhar B, Simoni-Wastila L.. Respiratory events associated with concomitant opioid and sedative use among Medicare beneficiaries with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2020;7(1):e000483 https://doi.org/ 10.1136/bmjresp-2019-000483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maharjan S, Kertesz SG, Bhattacharya K, et al. Coprescribing of opioids and psychotropic medications among Medicare-enrolled older adults on long-term opioid therapy. J Am Pharm Asso.: JAPhA. 2023;63(6):1753-1760.e5. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.japh.2023.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Herb JN, Williams BM, Chen KA, et al. The impact of standard postoperative opioid prescribing guidelines on racial differences in opioid prescribing: A retrospective review. Surgery. 2021;170(1):180–185 https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.surg.2020.12.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Santoro TN, Santoro JD.. Racial bias in the US opioid epidemic: A review of the history of systemic bias and implications for care. Cureus. 2018;10(12):e3733 https://doi.org/ 10.7759/cureus.3733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Singhal A, Tien YY, Hsia RY.. Racial–ethnic disparities in opioid prescriptions at emergency department visits for conditions commonly associated with prescription drug abuse. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0159224 https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0159224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Neprash HT, Gaye M, Barnett ML.. Abrupt discontinuation of long-term opioid therapy among Medicare beneficiaries, 2012–2017. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(6):1576–1583 https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s11606-020-06402-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Our analytic methods or coding are available to other researchers upon request. However, the original data used in this study cannot be shared by the investigators, but are available to be licensed from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. This study was not preregistered.