Abstract

Objective

To assess the existing body of evidence and impact of digital interventions on occupational health care.

Methods

The search strategy and review process were conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines. The search was carried out during a period from January 1, 2013 to June 5, 2023, using the SCOPUS and Ovid Medline databases. After the identification of the relevant records, screening was conducted in 3 stages, following specific predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. A data-extraction model was created on the basis of the aim of the review. The quality of the selected studies was evaluated using the Effective Public Health Practice framework. Owing to the heterogeneity of the outcome measures, we used narrative synthesis to summarize the findings.

Results

We identified 382 records in SCOPUS and 441 in Ovid Medline. We selected 54 studies to be included in the evidence synthesis. The health targets of the interventions varied widely, but we identified 2 main focus areas: sedentary behavior (n=17, 32%) and mental health (n=14, 26%). Even when the studies had the same health target, the outcomes and chosen measures varied widely. Given the considerable effect of the primary outcome, mental health appears to be a good target for digital interventions. Online training and computer software could be especially effective.

Conclusion

The potential positive impact of digital interventions on mental health, especially online training, should be leveraged by health care professionals and providers. In order to provide more specific recommendations for health care professionals, occupational health care researchers should strive for consensus on outcome measures.

Article Highlights.

-

•

Digital interventions should be considered, not only for mental health promotion but also for healthy lifestyle and cardiovascular health.

-

•

Online training appears to be suitable for addressing mental health issues such as burnout and depression in the workplace, and although they require initial investment, such interventions are subsequently quite easily scalable.

-

•

Given that mental health is now a major global concern, especially among younger adults, all tools that can help reduce the mental health-related disease burden are extremely important, from both societal and employer perspectives.

-

•

A consensus on specific outcome measures for evaluating the impact of digital health in occupational health care is essential for obtaining easily comparable results and providing more detailed advice for health care professionals and policy makers.

Workplace wellbeing is becoming increasingly important, emphasizing preventive measures and to move beyond traditional boundaries. The current key focuses are promoting mental health, preventing overwork, managing the labor force, and enhancing safety. Improved occupational health care benefits employees, employers, and the broader community, creating a transition from worker health to citizen health.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Digitalization and globalization are also impacting our work practices and preferences, and this new trend, known as work 4.0, is accompanied by health implications such as increased stress, musculoskeletal problems, and mental health issues.3,6

The World Health Organization defines digital health as “a broad umbrella term encompassing eHealth (which includes mHealth), as well as emerging areas, such as the use of advanced computing sciences in ‘big data’, genomics and artificial intelligence.”7 eHealth in turn is defined as “the use of information and communications technology in support of health and health-related fields” and mHealth as “the use of mobile wireless technologies for health.” mHealth falls under the concept eHealth.7

Digital interventions are increasingly being used in response to the current needs and trends in occupational health care, yet there is still much room for improvement compared with their use in data-driven fields.2 Digital interventions are cost effective and scalable, which means they show potential for achieving health benefits. An aspect to consider in the use of digital interventions is engaging patients in the use of new digital tools. Health care professionals, especially physicians, play a key role in this because a recommendation from a physician can be vital in promoting this needed engagement. However, health care professionals require solid scientific evidence before they are willing to recommend a new tool.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14

Despite the vast potential of digital interventions for addressing occupational health care needs, we still need to know more about which digital interventions to focus on in order to improve key prevention targets in occupational health care, which digital interventions to develop, and how to do this. Thus, the aim of this systematic review was to assess the existing body of evidence on the overall impact of digital interventions in occupational health care, in both experimental and real-world settings.

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

This study was a systematic review. We included all types of digital interventions that aligned with the definition given earlier: any digital, mobile, or wireless technology used to promote occupational health objectives. This encompasses interventions such as smartphone applications, wearables, chat platforms, messaging services, virtual appointments, and patient portals. In order to capture as comprehensive a view of the existing evidence as possible, we imposed no restrictions in terms of occupation or health targets. Moreover, as long as the study focused on the digital aspect, the intervention did not have to be exclusively digital; it could also encompass other aspects.

During the identification of relevant record duplicates, we excluded articles published before 2013 and not translated into English, as well as book chapters. We also excluded the following types of texts: review articles, editorial pieces, letters, and opinions. Studies that did not focus on evaluating the impact of a digital intervention or whose therapy area was not occupational health care were also excluded. Supplemental Appendix 1 (available online at https://www.mcpdigitalhealth.org/) presents the reasons for excluding each study at the full-text stage.

The search strategy and review process were conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines.15 We used the SCOPUS and Ovid Medline databases to search for results; the main search was conducted on June 5, 2023. Based on the mapping concept and PICO methodology16 for answering research questions, we combined the following terms for the search: digital health interventions, mhealth, mobile health, telemedicine, health application, e-health, OR health-IT with occupational health care AND occupational health, AND further with impact, assessment, improved health, improved outcomes, and value. Supplemental Appendix 2 (available online at https://www.mcpdigitalhealth.org/) presents more in-depth details on the search strategy. All records were screened independently by 2 reviewers (M.M.J.-M and A.M.R. or M.K.L.), and when opinions differed, all 3 reviewers evaluated the record in question and discussed whether it should be included or excluded. The full text of the remaining studies was assessed independently by 2 of the authors (M.M.J.-M. and A.M.R. or M.K.L.), using the same procedure as used for the screening. When the full text was not immediately available, the corresponding authors of the articles in question were contacted (3 corresponding authors were contacted, of who 2 responded and made the articles available for this review). M.M.J.-M. built a data-extraction model in Excel which the other reviewers tested (Table 1). After approval, data were extracted from the remaining studies. Data on publication details were automatically extracted via Zotero, whereas all other data were manually retrieved by the reviewers.

Table 1.

Data-Extraction Model Variables

| Publication details | Study details | Population | Intervention | Results | Conclusion | Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Start date | Type of worka | Type of interventionb | Time point for follow-up | Conclusion | Evaluation of biasc |

| Publication year | End date | Work classification | Health targetd | Timepoint for follow-up (weeks) | ||

| Author | Year conducted | Inclusion criteria | Duration of intervention | Primary outcomee | ||

| Publication title | Country | Exclusion criteria | Measure (primary outcome) | |||

| ISSN | Study design | Sample size | Outcome (primary) | |||

| DOI | Study design | Recruitment process | Secondary outcomes | |||

| Objective | Intervention group: age | Outcome (secondary) | ||||

| Retention ratef | Intervention group: sex | Measure (secondary outcome) | ||||

| Start date | Control (yes or no) | Significant or not, primary outcome | ||||

| End date | Control group age | Significant or not, primary outcome | ||||

| Control group sex |

DOI, digital object identifier; ISSN, international standard serial number.

Type of work was classified as either blue-collar (manual labor) or white-collar (office work, admin work, or similar) work.

Type of intervention was classified as smartphone applications, online interventions (delivered via the internet), computer software (local delivery), wearables, blended (digital component paired with nondigital intervention), online training (longer interventions with clear educational component), or a combination of any of the mentioned interventions (4 of the blended interventions contained a smartphone application component).

Bias was evaluated by the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) and reported as quality of study: weak, moderate, or strong.

Health target, that is, the target of the intervention was classified into sedentary behavior; mental health; healthy lifestyle; cardiovascular diseases; diabetes mellitus; complaints of the arm, neck, and shoulder (CANS); sickness absence; access to care; or process or a combination of the mentioned targets.

If not stated clearly in the study, primary outcome was assumed to be the first outcome measured.

Retention rate was calculated as the population at the end of the study divided by the population at the start of the study.

Data Analysis

Owing to the heterogeneity of the outcome measures, we used a narrative synthesis to summarize the findings. The significance was determined according to a P-value of <.05, CIs, odds ratios, or similar metrics. Three studies used a mixed-method or qualitative approach, which meant they did not report the statistical significance of their primary outcomes.

To evaluate bias and the quality of the studies, we used the Effective Public Health Practice Project model. This model takes several categories such as study design, population selection, and confounders into consideration. All categories are graded, and a final classification is calculated.17 The choice of the evaluation tool was based on the need to support all types of studies and on its previous successful evaluations of digital interventions.10 Supplemental Appendix 4 (available online at https://www.mcpdigitalhealth.org/) shows the final classification into weak, moderate, or strong.

Results

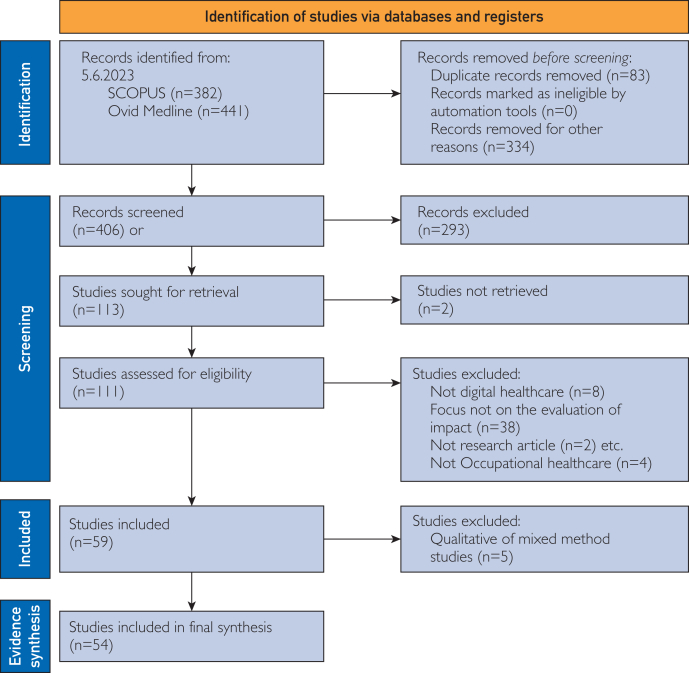

In total, 382 records were identified in SCOPUS and 441 in Ovid Medline in June 2023, which had been published between January 2013 and June 2023. After screening and eligibility evaluation, 59 studies remained. After we applied the data-extraction model, the final number of studies selected for the evidence synthesis was 54 (Figure, Supplemental Appendixes 2 and 3, available online at https://www.mcpdigitalhealth.org/).

Figure.

PRISMA flow chart of screening of records on impact of digital interventions in occupational health care.15

Main Characteristics

Table 211,18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70 presents the main characteristics of all studies (N=54) included in the evidence synthesis. Of these studies, 22 (41%) focused on white-collar workers, 7 (13%) on blue-collar workers, and 25 (46%) examined a mix of blue-collar and white-collar workers. Further analysis revealed that the health care sector (n=9, 19%) and office workers (n=13, 24%) were common study populations. Thirty studies (56%) were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), making this the most common study type. Thirty-two studies (59%) had control groups. With respect to the types of digital interventions used, 24 studies (44%) used smartphone applications, either alone or as part of a multicomponent intervention. The health targets of the interventions varied widely, but we identified 2 primary focus areas: sedentary behavior (n=17, 32%) and mental health (n=14, 26%). Additionally, 2 studies (3.7%) addressed a combined outcome of mental health and sedentary behavior.

Table 2.

Main Characteristics of Studies Included

| Reference, year | Country | Study design | Work classification | Sample size | Intervention | Target of intervention | Primary outcome | Significance of primary indicator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carr and Kevitt,18 2023 | Ireland | Cross-sectional | Mixed | 73 | Telecare | Access to care | User satisfaction | NA |

| Willman,19 2023 | United Kingdom | Mixed-method evaluation | White-collar | 135 | Telecare | Access to care | NA | NA |

| Hutting et al,20 2015 | Netherlands | RCT | Mixed | 123 | Blended intervention | CANS | Disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand questionnaire score | Not significant |

| Kouwenhoven-Pasmooij et al,21 2018 | Netherlands | RCT | Mixed | 493 | Online training/intervention | Cardiovascular health | Self-rated health | Significant |

| Ryu et al,22 2021 | Korea | Intervention study | White-collar | 87 | Application | Cardiovascular health | Cardiovascular-related health status | Significant |

| Simons et al,23 2017 | Netherlands | RCT | White-collar | 116 | Blended intervention | Cardiovascular health | Cardiovascular health, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein, blood pressure, blood glucose, and glycated hemoglobin | Significant |

| Widmer et al,24 2014 | United States | Cohort | Mixed | 152 | Online training/intervention | Cardiovascular health | Framingham Risk Score | Significant |

| Widmer et al,25 2016 | United States | Cohort | Mixed | 30,974 | Application, online training/intervention | Cardiovascular health | Weight, waist circumference, body mass index, blood pressure, lipids, and glucose at 12 mo | Significant |

| Lavaysse et al,26 2022 | United States | RCT | Mixed | 125 | Application, wearable, messages | Diabetes | Absenteeism and presenteeism | Not significant |

| Nagata et al,27 2022 | Japan | RCT | Mixed | 103 | Application, wearable, e-mail | Diabetes | Glycated hemoglobin | Significant |

| Nundy et al,28 2014 | Chicago, United States | Quasi-experimental | Mixed | 74 | Messages | Diabetes | Glycated hemoglobin, lipid profile, body mass index, and blood pressure | Significant |

| Röhling et al,29 2020 | Germany | RCT | Mixed | 30 | Blended intervention | Diabetes | Difference in weight reduction | Significant |

| Balk-Møller et al,30 2017 | Denmark | RCT | Mixed | 566 | Blended intervention | Healthy lifestyle | Changes in body weight | Significant |

| Johnson et al,31 2021 | United States | Intervention study | Mixed | 296 | Telecare | Healthy lifestyle | Weight loss percent | Significant |

| Kempf et al,32 2019 | Germany | RCT | White-collar | 104 | Telecare | Healthy lifestyle | Body weight reduction at 12 mo | Significant |

| Park et al,11 2022 | South Korea | Prospective observational study | Mixed | 1171 | Application | Healthy lifestyle | Changes in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, body weight, body mass index, waist, circumference, fasting blood glucose, triglyceride, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels | Significant |

| Wipfli et al,33 2019 | United States | Cohort | Blue-collar | 134 | Online training/intervention | Healthy lifestyle | Body weight, fruit and vegetable consumption, and physical activity | Significant |

| Bolier et al,34 2014 | Netherlands | RCT | White-collar | 1140 | Online training/intervention | Mental health | Positive mental health | Significant |

| Comtois et al,35 2022 | United States | RCT | Mixed | 1356 | Application | Mental health | Anxiety and suicidal behavior | Significant |

| Costa et al,36 2022 | United States | Cohort | Mixed | 7785 | Application, wearable | Mental health | Mean change in depression | Not significant |

| De Kock et al,37 2022 | United Kingdom | RCT | Mixed | 169 | Application | Mental health | Mental wellbeing and anxiety | Significant |

| Ebert et al,38 2018 | Germany | CBA | White-collar | 264 | Online training/intervention | Mental health | No. of participants who achieved symptom-free status | Significant |

| Gayed et al,39 2019 | Australia | RCT | White-collar | 210 | Online training/intervention | Mental health | Change in managers’ self-reported confidence in creating a mentally healthy workplace in which the mental health needs of their employees are appropriately supported | Significant |

| Gwain et al,40 2022 | United States | Cohort | White-collar | 43 | Messages | Mental health | Prevalence of depressive symptoms | Significant |

| Jukic et al,41 2020 | Slovenia | Intervention study | White-collar | 17 | Application | Mental health | Participants’ cardiovascular fitness levels | Not significant |

| Lokman et al,42 2017 | Netherlands | RCT | Mixed | 220 | Online training/intervention, e-mails | Mental health | Health care use and absenteeism from work | Significant |

| Meyer et al,43 2018 | Australia | Mixed-method evaluation | Mixed | 178,350 | Application, wearable, online training | Mental health | Psychological wellbeingwell | Significant |

| Michelsen and Kjellgren,44 2022 | Sweden and United Kingdom | Intervention study | Mixed | 50 | Online training/intervention | Mental health | Risk of burnout | Significant |

| Sasaki et al,45 2021 | Vietnam | RCT | Blue-collar | 962 | Application | Mental health | Work engagement | Not significant |

| Umanodan et al,46 2014 | Japan | RCT | Blue-collar | 266 | Computer software | Mental health | Psychological distress, work engagement, and work performance | Significant |

| Volker et al,47 2015 | Netherlands | RCT | Mixed | 220 | Online training/intervention | Mental health | Duration until first return to work | Significant |

| Atkins et al,48 2020 | Finland | RCT | Mixed | 26,804 | Blended intervention | Process | Education of mean number of medium-term (4-14 calendar days) sickness absences | Not significant |

| Chen et al,49 2019 | China | RCT | Blue-collar | 1211 | Blended intervention | Process | Self-reported appropriate use of respiratory protective equipment | Significant |

| Boerema et al,50 2019 | Netherlands | Intervention study | White-collar | 15 | Application, wearable | Sedentary behavior | Physical activity, total sedentary time, and No. of sedentary spells | Not significant |

| Bort-Roig, et al,51 2020 | Spain | RCT | White-collar | 141 | Application | Sedentary behavior | Total sitting time, sedentary spells, and breaks | Not significant |

| Cooley et al,52 2014 | Australia | Qualitative evaluation | Mixed | 46 | Computer software | Sedentary behavior | Microsystem, mesosystem, and exosystems of Bronfenbrenner (1992) model | Not applicable |

| Gilson et al,53 2017 | Australia | Intervention study | Blue-collar | 44 | Blended intervention | Sedentary behavior | Physical activity | Not significant |

| Huang et al,54 2023 | Taiwan | RCT | White-collar | 223 | Application, online training, messages | Sedentary behavior | Physical activity measured using metabolic equivalents | Not significant |

| Judice et al,55 2015 | Portugal | RCT | White-collar | 10 | Computer software | Sedentary behavior | Sitting time and standing time, sit/stand transitions | Significant |

| Kouwenhoven-Pasmooij et al,56 2017 | Netherlands | Intervention study | Blue-collar | 51 | Blended intervention | Sedentary behavior | Average physical activity per day | Significant |

| Lau and Faulkner,57 2019 | Canada | Intervention study | Mixed | 843 | Blended intervention | Sedentary behavior | Daily steps | Not significant |

| Lee et al,58 2019 | South Korea | Quasi-experimental | Mixed | 79 | Blended intervention | Sedentary behavior | Daily walking steps | Significant |

| Lennefer et al,59 2020 | Germany | Intervention study | White-collar | 121 | Application, online training/intervention | Sedentary behavior | No. of steps, job control, self-efficacy, emotional strain, and negative effect | Significant |

| MacDonald et al,60 2020 | United Kingdom | Mixed-method evaluation | White-collar | 80 | Application | Sedentary behavior | Streaks in sedentary behavior at work and total sedentary behavior at work | Not significant |

| Mainsbridge et al,61 2014 | Australia | RCT | Mixed | 29 | Computer software | Sedentary behavior | Mean arterial pressure | Significant |

| Mainsbridge et al,62 2018 | Australia | Cohort | White-collar | 228 | Computer software | Sedentary behavior | Mean arterial pressure | Significant |

| Maylor et al,63 2018 | United Kingdom | RCT | White-collar | 89 | Blended intervention | Sedentary behavior | Workplace sitting time | Not significant |

| Morris et al,64 2020 | Australia | RCT | White-collar | 56 | Application | Sedentary behavior | Behavioral outcomes (worktime sitting, standing, stepping, prolonged sitting, and physical activity) | Significant |

| Pedersen et al,65 2014 | Australia | RCT | White-collar | 34 | Computer software | Sedentary behavior | Workplace daily energy expenditure | Significant |

| Thogersen-Ntoumani et al,66 2020 | Australia | RCT | White-collar | 97 | Blended intervention | Sedentary behavior | Steps, standing, and sitting | Not significant |

| Haile et al,67 2020 | United Kingdom | Intervention study | White-collar | 41 | Application | Sedentary behavior and mental health | Sitting and physical activity | Significant |

| Muniswamy et al,68 2022 | India | RCT | White-collar | 64 | Online training/intervention, social media, telecare | Sedentary behavior and mental health | Physical health | Not significant |

| Notenbomer et al,69 2018 | Netherlands | RCT | Mixed | 82 | Online training/intervention | Sickness absence | No. of register-based sickness absence episodes | Not significant |

| Van Schaaijk et al,70 2019 | Netherlands | RCT | Blue-collar | 124 | Application | Work ability | Work ability, vitality, work-related fatigue | Not significant |

Statistically significant: P<.05.

CBA, cost-benefit analysis; CANS, complaints of the arm, neck and shoulder; NA, not applicable; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Ten studies were conducted in the Netherlands20,21,23,34,42,47,50,56,69,70; 9 each in Australia39,43,52,53,61,62,64, 65, 66 and in the United States of America24, 25, 26,28,31,33,35,36,40; 5 in the United Kingdom19,37,60,63,67; 4 in Germany29,32,38,59; 3 in South Korea11,22,58; and 2 in Japan.27,46 Finally, Canada, China, Denmark, Finland, India, Ireland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Taiwan, and Vietnam18,30,41,44,45,48,49,51,54,55,57,68 all had 1 study each.

Significance of Primary Outcome

Regarding the significance of the primary indicator, 51 studies were included in the analysis. Three studies18,19,52 did not report statistical significance of the primary outcome and were thus excluded from this part of the analysis. A significant effect of the primary outcome was observed for 32 of the 51 (63%) studies. Table 3 presents the significance of the primary outcome by target and Table 4 by digital intervention.

Table 3.

Significance of Primary Outcome Reported by Health Target

| Health target | Significant | Not significant | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complaints of the arm, neck and shoulder | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Cardiovascular health | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Diabetes | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Healthy lifestyle | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Mental health | 10 | 4 | 14 |

| Process measure | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Sedentary behavior | 8 | 8 | 16 |

| Sedentary behavior and mental health | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Sickness absence | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Work ability | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 33 | 18 | 51 |

Table 4.

Significance of Primary Outcome by Digital Intervention

| Type classification | Significant | Not significant | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Application | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| Application, messages, online training | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Application, online training/intervention | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Application, wearable | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Application, wearable, e-mails | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Application, wearable, messages | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Application, wearable, online training | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Blended intervention | 7 | 5 | 12 |

| Computer software | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Messages | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Online training/intervention | 7 | 2 | 9 |

| Online training/intervention, e-mails | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Online training/intervention, social media, telecare | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Telecare | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Total | 33 | 18 | 51 |

As regards sedentary behavior, 8 of the 17 studies (47%) reported a significant positive effect.55,56,58,59,61,62,64,65 Smartphone applications were used in 7 of the 17 studies, 3 (43%)59,64,67 of which reported a significant effect.

A more detailed examination of mental health revealed that 11 of the 14 studies (79%) reported a significant positive effect.34,35,37, 38, 39, 40,42, 43, 44,46,47 Of these, all 6 studies34,39,42,44,47,71 that investigated the effects of online training on mental health had significant positive effects on the primary outcome. Significant positive effects were also observed in 3 of the 6 studies (50%) that included smartphone application interventions.35,37,43

All 5 studies (100%) targeting healthy lifestyle11,30, 31, 32, 33 reported significant results. The interventions used were telecare,31,32 smartphone applications,11 online interventions,33 and blended interventions.30 Regarding cardiovascular health, significant results were observed in all 5 studies (100%).18,21, 22, 23, 24, 25 The interventions used smartphone applications alone,22 in combination with online training,25 or online trainings alone,21,24 and 1 was a blended intervention.23 For diabetes, significant results were obtained in 3 of the 4 (75%) interventions that used smartphone applications in combination with wearables, e-mails, messaging, and blended interventions.27, 28, 29

Using the Effective Public Health Practice Project framework (Table 5), the overall quality of the studies (including the evaluation of risk of bias) was rated as high in 7 cases,19,21,30,50,51,61,67 moderate in 17 cases,18,20,24,28,32,36,37,41,42,47,49,53,58,62,63,68,70 and weak in 28 cases.11,22,23,26,27,29,31,33, 34, 35,38, 39, 40,43, 44, 45, 46,48,54, 55, 56, 57,59,60,64, 65, 66,69 and not applicable in 2.25,52 Potential selection bias was the most commonly identified bias and was frequently acknowledged by the researchers themselves. The generalizability of the results was also a frequently highlighted issue because the study populations were often quite small or highly specific. None of the studies were excluded from the analysis on the basis of the risk of bias. Supplemental Appendix 4 provides further details on the quality of the studies.

Table 5.

Evaluation of Bias According to Effective Public Health Practice Framework

| Strong | Moderate | Weak | NA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sedentary behavior | 350,51,61 | 453,58,62,63 | 954, 55, 56, 57,59,60,64, 65, 66 | 152 |

| Mental health | 0 | 536,37,41,42,47 | 934,35,38, 39, 40,43, 44, 45, 46 | |

| Mental health and sedentary behavior | 167 | 168 | 0 | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 121 | 124 | 222,23 | 125 |

| Diabetes | 0 | 128 | 326,27,29 | |

| Healthy behavior | 130 | 132 | 311,31,33 | |

| Access to care | 119 | 118 | — | |

| Process | 0 | 149 | 148 | |

| Complaints of the arm neck and shoulder | 0 | 120 | 0 | |

| Sickness absence | 0 | 0 | 169 | |

| Work ability | 0 | 170 | — |

NA, not applicable.

Discussion

In this systematic review, the aim of which was to assess the existing body of evidence on the impact of digital interventions in occupational health care, we observed that digital intervention research in occupational health care focuses on mental health and sedentary behavior. It appears that online training or interventions may have significant effects, and overall, significant effects were more prominent in the studies of healthy lifestyle, cardiovascular diseases, and mental health. We also concluded that heterogeneity is a significant issue in outcome measures and that it affects whether results can be pooled and more detailed conclusions drawn.

The identified focus of digital interventions targeting mental health and sedentary behavior in occupational health care is in line with that in the existing literature.3,5 It is also in line with the current trends and needs of workplace wellbeing, such as focusing on preventive measures, because sedentary behavior poses the risk of an array of chronic diseases and mental health problems, with the added burden to mental wellbeing brought by global digital developments that can be seen in workplaces today.3,6

According to this review, computer applications and online training often had a positive impact on selected occupational health care outcomes. This was the case in all 5 studies of computer applications and in 8 of 11 studies of online training or interventions. Of the studies primarily focusing on mental health, 11 of 14 studies reported a significant positive effect, whereas of the 16 studies examining sedentary behavior, only 8 reported a significant positive effect, 1 study reported no significance in this matter. Previous systematic reviews of digital intervention studies of both mental health and sedentary behavior have also observed similar small effects.2 Digital interventions have been found to have positive effects on mental health; these effects being stronger among workers with initially high stress levels.72 Although fewer of the studies in this review focused on healthy lifestyle and cardiovascular health than those on mental health, 5 of each, both health targets show promise, and all 5 healthy lifestyle studies found a significant primary outcome measure, as did the 5 cardiovascular health studies. However, it would be fruitful to further investigate this promising trend in focused reviews using the same metrics because this would enable the comparison of results and provide reliable information on the impact of digital interventions on mental health and other interesting occupational health care focuses.

It was also interesting to note that of the 54 included studies, only 2 had patient experience or engagement as their primary outcome, and 20 of the included studies did not take patient engagement, satisfaction, or experience into consideration at all. As encouragement of patient engagement is recommended, especially in digital interventions, we had hoped that this ratio would have been even higher.2 This result should be interpreted with caution because we did not include a specific search term for patient engagement. However, we did not restrict the target of the digital interventions or the chosen outcome for this review.

We were unable to pool the results owing to the wide variations in the selection of health targets and subsequent choice of outcome measures. Previous systematic reviews have also identified the heterogeneity of studies, especially in terms outcome measurement, as an issue. For instance, Howarth et al2 found moderate evidence of purely digital interventions, with effects ranging from sleep and mental health to sedentary behavior, but mentioned lack of consensus on outcome measure as hampering stronger evidence.

Regarding the quality of the included studies, a common issue was selection bias, either in the form of voluntary participants who were perhaps more susceptible to changing their habits or behaviors or in obtaining enough participants from the initially chosen population. Additionally, many studies saw attrition and retention rates as issues; these were often influenced by various factors such as lengthy questionnaires or technical issues with the digital intervention components. This can partly be explained by the fact that a portion of the included studies were pilot studies, and thus, the researchers involved were often also the developers of the intervention, seeking a deeper understanding of its effects. Furthermore, their restrictions on individuals with access to digital tools in their field of work or, further still, to smartphones, create inequalities and make the generalizability of the results challenging. Some studies even required a specific type of smartphone for participation in the study,51 or even more interestingly, participation in the intervention group,64 thereby causing a clear risk of bias. Finally, regarding publication bias, there was a nonsignificant effect regarding the primary outcome in 19 of the 54 studies, which might signal that the risk of publication bias is acceptable. However, closer examination of the significance of all included measures revealed that the ratio changed drastically to nonsignificant effects in only 3 of the 54 studies.

Despite over 2 decades of research and use of digital interventions in occupational health care, there are few signs that developers or researchers take into account existing evidence when developing their projects and reaching consensus on outcome measures as recommended.9 To combine results and offer more specific, quantifiable recommendations to health care professionals and providers, occupational health care researchers should really strive for consensus on outcome measures.

Given that mental health, especially that of younger adults, is now a major global concern, all tools that can potentially help reduce the societal disease burdens related to mental health are extremely important.73 It is also noteworthy that all studies discussed in this study span the past decade and that not all their participants had as much experience with digital tools in general as the digitally native generations that have increasingly entered the workforce. The potential of these younger generations and its possible implications is something researchers should explore.

Strengths and Limitations of the Research

We recognize several strengths in our study. One is its broad scope, encompassing both the digital interventions used in the included studies and the health targets addressed. Another important strength was our goal to reflect real-world settings, leading us to include various study types, as long as they consisted of original research. In practice, digital interventions are typically part of larger intervention groups targeting health improvement and are not generally implemented in isolation, as is the case in RCTs. However, because they minimize any confusion caused by other concurrent factors affecting the workers in addition to the interventions, RCTs still play an important role in research.

Our study has certain limitations that should be considered when evaluating the significance of the results. For instance, its inclusive approach may have led to variation in the overall quality of the included studies, at least when assessed using the quality assessment tools available. This variation can be viewed as a limitation of the systematic review. Another limitation is the heterogeneity of the studies, which, as mentioned earlier, prevented us from pooling the results for meta-analysis. Consequently, the outcomes were categorized as significant or not significant rather than presented with actual means with CIs, odds ratios, or similar metrics, leading to a more simplified interpretation of the findings.

In the future, it would be essential for occupational health care researchers to reach consensus on key outcome measures. This would ensure comparable results, thereby providing reliable information for health care professionals. Occupational health care should pay special attention to the possibilities in mental health. Another aspect to consider is whether the focus should be solely on improving difficult outcomes or whether it would be more beneficial to invest in empowering patients and enhancing patient satisfaction, as well as health care professionals’ satisfaction and the usability of the intervention.

Conclusion

The potential positive impact of digital interventions on mental health, especially online training, should be leveraged by health care professionals and providers in the future. Their potential to support the management of cardiovascular disease and diabetes, and to promote a healthy lifestyle is also noteworthy. Online training is well suited to addressing mental health issues such as burnout and depression in workplace settings, and although they require an initial investment, such interventions are subsequently quite scalable in office environments for instance, where they can have a substantial impact. This offers an excellent opportunity to address one of the key targets of combating the global mental health problem.

Potential Competing Interests

Dr Matintupa received grants from Finska Läkaresällskapet for her doctoral studies, which was used for the work on this manuscript and received grants from Waldemar von Frenckells stiftelse and Svenska Österbottniska Samfundet. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Grant Support: Open access was funded by Helsinki University Library. This research used a grant (M.M.J.-M.) received from Finska Läkaresällskapet, Waldemar von Frenckells stiftelse, and Svenska Österbottniska Samfundet for her doctoral studies.

Data Previously Presented: An abstract of this study was presented at the 23rd Nordic Congress of General Practice 2024, in Turku, Finland, June 13, 2024.

Supplemental material can be found online at https://www.mcpdigitalhealth.org/. Supplemental material attached to journal articles has not been edited, and the authors take responsibility for the accuracy of all data.

Supplemental Online Material

References

- 1.Sepulveda M.J. From worker health to citizen health: moving upstream. J Occup Environ Med. 2013;55(12 Suppl):S52–S57. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howarth A., Quesada J., Silva J., Judycki S., Mills P.R. The impact of digital health interventions on health-related outcomes in the workplace: a systematic review. Digit Health. 2018;4 doi: 10.1177/2055207618770861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison J., Dawson L. Occupational Health: meeting the challenges of the next twenty years. Saf Health Work. 2015;7(2):143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Burton J. World Health Organization; 2010. WHO Healthy Workplace Framework and Model: Background and Supporting Literature and Practices.https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/113144 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sano Y., Yoshikawa T., Nakashima Y., et al. Analysis of occupational health activities through classifying reports from medical facilities in Japan. Sangyo Eiseigaku Zasshi. 2020;62(3):115–126. doi: 10.1539/sangyoeisei.2019-010-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zorzenon R., Lizarelli F.L., de A., Moura D.B.A. What is the potential impact of industry 4.0 on health and safety at work? Saf Sci. 2022;153 doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2022.105802. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2019. WHO Guideline: Recommendations on Digital Interventions for Health System Strengthening.https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/311941 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oakman J., Kinsman N., Stuckey R., Graham M., Weale V. A rapid review of mental and physical health effects of working at home: how do we optimise health? BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1825. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09875-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stratton E., Lampit A., Choi I., et al. Trends in effectiveness of organizational ehealth interventions in addressing employee mental health: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(9) doi: 10.2196/37776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buckingham S.A., Williams A.J., Morrissey K., Price L., Harrison J. Mobile health interventions to promote physical activity and reduce sedentary behaviour in the workplace: a systematic review. Digit Health. 2019;5 doi: 10.1177/2055207619839883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park J.H., Jung S.E., Ha D.J., et al. The effectiveness of e-healthcare interventions for mental health of nurses: a PRISMA-compliant systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022;101(25) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000029125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cotie L.M., Prince S.A., Elliott C.G., et al. The effectiveness of eHealth interventions on physical activity and measures of obesity among working-age women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2018;19(10):1340–1358. doi: 10.1111/obr.12700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thai Y.C., Sim D., McCaffrey T.A., Ramadas A., Malini H., Watterson J.L. A scoping review of digital workplace wellness interventions in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS One. 2023;18(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0282118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leigh S., Ashall-Payne L. The role of health-care providers in mHealth adoption. Lancet Digit Health. 2019;1:e58–e59. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(19)30025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schardt C., Adams M., Owens T., Keitz S., Fontelo P. Utilization of the PICO framework of improve searching PubMed for clinical question. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007;7:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas B.H., Ciliska D., Dobbins M., Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004;1(3):176–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carr P., Kevitt F. Service user satisfaction with telemedicine in an occupational healthcare setting. Occup Med (Lond) 2023;73(4):205–207. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqad047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Willman A.S. Evaluation of eConsult use by Defence Primary Healthcare primary care clinicians using a mixed-method approach. BMJ Mil Health. 2023;169(e1):e39–e43. doi: 10.1136/bmjmilitary-2020-001660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hutting N., Detaille S.I., Engels J.A., Heerkens Y.F., Staal J.B., Nijhuis-van der Sanden M.W. Development of a self-management program for employees with complaints of the arm, neck, and/or shoulder: an intervention mapping approach. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2015;8:307–320. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S82809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kouwenhoven-Pasmooij T.A., Robroek S.J.W., Kraaijenhagen R.A., et al. Effectiveness of the blended-care lifestyle intervention “PerfectFit”: a cluster randomised trial in employees at risk for cardiovascular diseases. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):766. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5633-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryu H., Jung J., Moon J. Effectiveness of a mobile health management program with a challenge strategy for improving the cardiovascular health of workers. J Occup Environ Med. 2021;63(3):e132–e137. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simons L.P.A., Hafkamp M.P.J., Van Bodegom D., Dumaij A., Jonker C.M. Improving employee health; lessons from an RCT. Int J Netw Virtual Organ. 2017;17(4):341–353. doi: 10.1504/IJNVO.2017.088485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Widmer R.J., Allison T.G., Keane B., Dallas A., Lerman L.O., Lerman A. Using an online, personalized program reduces cardiovascular risk factor profiles in a motivated, adherent population of participants. Am Heart J. 2014;167(1):93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Widmer R.J., Allison T.G., Keane B., et al. Workplace digital health is associated with improved cardiovascular risk factors in a frequency-dependent fashion: a large prospective observational cohort study. PLoS One. 2016;11(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lavaysse L.M., Imrisek S.D., Lee M., et al. One drop improves productivity for workers with type 2 diabetes: one drop for workers with type 2 diabetes. J Occup Environ Med. 2022;64(8):e452–e458. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagata T., Aoyagi S.S., Takahashi M., Nagata M., Mori K. Effects of feedback from self-monitoring devices on lifestyle changes in workers with diabetes: 3-month randomized controlled pilot trial. JMIR Form Res. 2022;6(8) doi: 10.2196/23261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nundy S., Dick J.J., Chou C.H., Nocon R.S., Chin M.H., Peek M.E. Mobile phone diabetes project led to improved glycemic control and net savings for Chicago plan participants. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2014;33(2):265–272. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Röhling M., Martin K., Ellinger S., Schreiber M., Martin S., Kempf K. Weight reduction by the low-insulin-method—a randomized controlled trial. Nutrients. 2020;12(10):1–17. doi: 10.3390/nu12103004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balk-Møller N.C., Poulsen S.K., Larsen T.M. Effect of a nine-month web- and app-based workplace intervention to promote healthy lifestyle and weight loss for employees in the social welfare and health care sector: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(4) doi: 10.2196/jmir.6196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson K.E., Alencar M.K., Miller B., Gutierrez E., Dionicio P. Exploring sex differences in the effectiveness of telehealth-based health coaching in weight management in an employee population. Am J Health Promot. 2021;35(2):262–265. doi: 10.1177/0890117120943363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kempf K., Röhling M., Martin S., Schneider M. Telemedical coaching for weight loss in overweight employees: a three-armed randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2019;9(4) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wipfli B., Hanson G., Anger K., et al. Process evaluation of a mobile weight loss intervention for truck drivers. Saf Health Work. 2019;10(1):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bolier L., Ketelaar S.M., Nieuwenhuijsen K., Smeets O., Gärtner F.R., Sluiter J.K. Workplace mental health promotion online to enhance well-being of nurses and allied health professionals: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Internet Interv. 2014;1(4):196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2014.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Comtois K.A., Mata-Greve F., Johnson M., Pullmann M.D., Mosser B., Arean P. Effectiveness of mental health apps for distress during COVID-19 in US unemployed and essential workers: remote pragmatic randomized clinical trial. JMIR MHealth UHealth. 2022;10(11) doi: 10.2196/41689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Costa F., Janela D., Molinos M., et al. Impacts of digital care programs for musculoskeletal conditions on depression and work productivity: longitudinal cohort study. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(7) doi: 10.2196/38942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Kock J.H., Latham H.A., Cowden R.G., et al. Brief digital interventions to support the psychological well-being of NHS staff during the COVID-19 pandemic: 3-arm pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment Health. 2022;9(4) doi: 10.2196/34002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ebert D.D., Kahlke F., Buntrock C., et al. A health economic outcome evaluation of an internet-based mobile-supported stress management intervention for employees. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2018;44(2):171–182. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gayed A., Bryan B.T., LaMontagne A.D., et al. A cluster randomized controlled trial to evaluate HeadCoach: an online mental health training program for workplace managers. J Occup Environ Med. 2019;61(7):545–551. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gwain G.C., Amu H., Bain L.E. Improving employee mental health: a health facility-based study in the United States. Front Public Health. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.895048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jukic T., Ihan A., Strojnik V., Stubljar D., Starc A. The effect of active occupational stress management on psychosocial and physiological wellbeing: a pilot study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2020;20(1):321. doi: 10.1186/s12911-020-01347-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lokman S., Volker D., Zijlstra-Vlasveld M.C., et al. Return-to-work intervention versus usual care for sick-listed employees: health-economic investment appraisal alongside a cluster randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2017;7(10) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meyer D., Jayawardana M.W., Muir S.D., Ho D.Y.T., Sackett O. Promoting psychological well-being at work by reducing stress and improving sleep: mixed-methods analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(10) doi: 10.2196/jmir.9058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Michelsen C., Kjellgren A. The effectiveness of web-based psychotherapy to treat and prevent burnout: controlled trial. JMIR Form Res. 2022;6(8) doi: 10.2196/39129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sasaki N., Imamura K., Tran T.T.T., et al. Effects of Smartphone-based stress management on improving work engagement among nurses in Vietnam: secondary analysis of a three-arm randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(2) doi: 10.2196/20445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Umanodan R., Shimazu A., Minami M., Kawakami N. Effects of computer-based stress management training on psychological well-being and work performance in Japanese employees: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Ind Health. 2014;52(6):480–491. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.2013-0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Volker D., Zijlstra-Vlasveld M.C., Anema J.R., et al. Effectiveness of a blended web-based intervention on return to work for sick-listed employees with common mental disorders: results of a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(5) doi: 10.2196/jmir.4097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Atkins S., Reho T., Talola N., Sumanen M., Viljamaa M., Uitti J. Improved recording of work relatedness during patient consultations in occupational primary health care: a cluster randomized controlled trial using routine data. Trials. 2020;21(1):256. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-4168-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen W., Li T., Zou G., et al. Results of a cluster randomized controlled trial to promote the use of respiratory protective equipment among migrant workers exposed to organic solvents in small and medium-sized enterprises. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(17):3187. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16173187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boerema S., van Velsen L., Hermens H. An intervention study to assess potential effect and user experience of an mHealth intervention to reduce sedentary behaviour among older office workers. BMJ Health Care Inform. 2019;26(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjhci-2019-100014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bort-Roig J., Chirveches-Perez E., Gine-Garriga M., et al. An mHealth workplace-based “sit less, move more” program: impact on employees’ sedentary and physical activity patterns at work and away from work. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(23):8844. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17238844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cooley D., Pedersen S., Mainsbridge C. Assessment of the impact of a workplace intervention to reduce prolonged occupational sitting time. Qual Health Res. 2014;24(1):90–101. doi: 10.1177/1049732313513503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gilson N.D., Pavey T.G., Wright O.R., et al. The impact of an m-Health financial incentives program on the physical activity and diet of Australian truck drivers. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):467. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4380-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang S.J., Hung W.C., Shyu M.L., Chou T.R., Chang K.C., Wai J.P. Field Test of an m-Health worksite health promotion program to increase physical activity in Taiwanese employees: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Workplace Health Saf. 2023;71(1):14–21. doi: 10.1177/21650799221082304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Judice P.B., Hamilton M.T., Sardinha L.B., Silva A.M. Randomized controlled pilot of an intervention to reduce and break-up overweight/obese adults’ overall sitting-time. Trials. 2015;16:490. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-1015-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kouwenhoven-Pasmooij T.A., Robroek S.J.W., Ling S.W., et al. A blended web-based gaming intervention on changes in physical activity for overweight and obese employees: Influence and usage in an experimental pilot study. JMIR Serious Games. 2017;5(2) doi: 10.2196/games.6421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lau E.Y., Faulkner G. Program implementation and effectiveness of a national workplace physical activity intervention: UPnGO with ParticipACTION. Can J Public Health. 2019;110(2):187–197. doi: 10.17269/s41997-018-0170-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee S.H., Ha Y., Jung M., Yang S., Kang W.S. The effects of a mobile wellness intervention with FitBit use and goal setting for workers. Telemed E-Health. 2019;25(11):1115–1122. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2018.0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lennefer T., Reis D., Lopper E., Hoppe A. A step away from impaired well-being: a latent growth curve analysis of an intervention with activity trackers among employees. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2020;29(5):664–677. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2020.1760247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.MacDonald B., Gibson A.M., Janssen X., Kirk A. A mixed methods evaluation of a digital intervention to improve sedentary behaviour across multiple workplace settings. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(12):4538. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mainsbridge C.P., Cooley P.D., Fraser S.P., Pedersen S.J. The effect of an e-health intervention designed to reduce prolonged occupational sitting on mean arterial pressure. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(11):1189–1194. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mainsbridge C., Ahuja K., Williams A., Bird M.L., Cooley D., Pedersen S.J. Blood pressure response to interrupting workplace sitting time with non-exercise physical activity results of a 12-month cohort study. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60(9):769–774. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maylor B.D., Edwardson C.L., Zakrzewski-Fruer J.K., Champion R.B., Bailey D.P. Efficacy of a multicomponent intervention to reduce workplace sitting time in office workers: a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60(9):787–795. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morris A.S., Mackintosh K.A., Dunstan D., et al. Rise and recharge: effects on activity outcomes of an e-health smartphone intervention to reduce office workers’ sitting time. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(24):1–18. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pedersen S.J., Cooley P.D., Mainsbridge C. An e-health intervention designed to increase workday energy expenditure by reducing prolonged occupational sitting habits. Work. 2014;49(2):289–295. doi: 10.3233/WOR-131644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thogersen-Ntoumani C., Quested E., Smith B.S., et al. Feasibility and preliminary effects of a peer-led motivationally-embellished workplace walking intervention: a pilot cluster randomized trial (the START trial) Contemp Clin Trials. 2020;91(101242342) doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2020.105969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Haile C., Kirk A., Cogan N., Janssen X., Gibson A.M., MacDonald B. Pilot testing of a nudge-based digital intervention (Welbot) to improve sedentary behaviour and wellbeing in the workplace. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):5763. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Muniswamy P., Gorhe V., Parashivakumar L., Chandrasekaran B. Short-term effects of a social media-based intervention on the physical and mental health of remotely working young software professionals: a randomised controlled trial. Appl Psychol Health Well-Being. 2022;14(2):537–554. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Notenbomer A., Roelen C., Groothoff J., Van Rhenen W., Bültmann U. Effect of an eHealth intervention to reduce sickness absence frequency among employees with frequent sickness absence: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(10) doi: 10.2196/10821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Van Schaaijk A., Nieuwenhuijsen K., Frings-Dresen M. Work ability and vitality in coach drivers: An rct to study the effectiveness of a self-management intervention during the peak season. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(12):2214. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16122214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ebert D.D., Lehr D., Smit F., et al. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of minimal guided and unguided internet-based mobile supported stress-management in employees with occupational stress: a three-armed randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:807. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moe-Byrne T., Shepherd J., Merecz-Kot D., et al. Effectiveness of tailored digital health interventions for mental health at the workplace: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. PLoS Digit Health. 2022;1(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pdig.0000123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.World Health Organization . WHO; 2022. World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health For All. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.