Abstract

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), a rare subtype of peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) with regional differences, originates from follicular T helper (Tfh) cells and is characterized by significant immunological involvement. The tumor microenvironment (TME) in AITL is complex, primarily composed of T cells, B cells, plasma cells, follicular dendritic cells and high endothelial venules. Genetically, AITL exhibits the characteristics of TET2 and DNMT3A mutations in hematopoietic stem cells, while RHOA and IDH2 mutations are detected in the Tfh cells. Subsequently, Tfh cells begin to release various chemokines and cytokines to regulate the intricate network of interactions with TME promoting development of AITL. Diagnosis remains challenging for AITL due to diverse clinical presentations and laboratory features resembling changes seen in multiple benign diseases. Several predictive models have been proposed; however, overall prognosis for AITL remains poor. Treatment strategies should be based on the patient’s age, physical condition, and comorbidities. Participation in clinical trials is recommended as an initial treatment strategy. Autologous stem-cell transplantation (ASCT) for AITL still remains to be a subject of ongoing debate. Numerous multi-phase clinical trials have been carried out for relapsed/refractory (R/R) AITL. Moreover, CAR-T and CAR-NK therapy represents promising avenues that are worthy of further exploration for the treatment of AITL.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10238-025-01754-4.

Keywords: Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL; WHO-HAEM5: nTFHL-AI), Pathogenesis, Prognosis, Therapeutic approaches

Introduction

Overview

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) is an uncommon and distinct subtype of peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) renowned for its profound inflammatory processes, with the involvement of inflammatory/immune cells in the microenvironment being more prominent compared to other malignant tumors [1, 2]. Gene expression profiling (GEP) has indicated that AITL cells originate from follicular T helper (Tfh) cells [3]. In physiological conditions, Tfh cells, which are critical participants in the formation of humoral immunity, have a significant impact on the development and function of germinal center(GC), and actively participate in the process of differentiating memory B cells and plasma cells [4–6]. Consequently, clonal expansion of Tfh cells results in disruption of the GCs equilibrium under pathological conditions, leading to pro-inflammatory phenomena, autoimmunity, and increased immunoglobulin secretion [7]. Therefore, in addition to systemic lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly, patients with AITL may also show immunologic hyperactivation like polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia or hemolytic anemia [3, 8]. Based on the 2016 revised World Health Organization (WHO) classification, AITL, follicular T-cell lymphoma, and nodal PTCL with Tfh phenotype were consolidated under a unified classification [9]. AITL has been revised to nodal T-follicular helper cell lymphoma, angioimmunoblastic-type (nTFHL-AI) in the 5th edition of the WHO Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms; however, given that the majority of recent studies continue to employ the term "AITL," this nomenclature has been preserved in this review for clarity and consistency [10].

Epidemiology

The occurrence of AITL in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma ranges from 1 to 2%, while it accounts for 15% to 20% of PTCL [11]. As the second prevalent subtype of PTCL, AITL exhibits geographical variations in its distribution [12, 13]. The prevalence of AITL is higher in Europe compared to Asia and North America [7, 12], possibly due to the rise in natural killer/T-cell (NK/T) lymphoma observed in Asia instead of representing a distinct disparity [14]. AITL is a prototypical malignancy arising from age-related clonal hematopoiesis (ACH), where hematopoietic stem or progenitor cells (HSPCs) experience clonal proliferation with age [15]. A study utilizing surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database show that AITL typically manifests in the elderly population, with an average age of diagnosis at 69 years and most cases presenting at advanced stage [16]. Results are similar in several cohort studies, of which the median age of about 62–67 years, Ann Arbor III or IV of 81–98%, and B symptoms of 60–77% [17]. Patients with AITL are often compromised by clinical relapse following temporary response, indicating poor prognosis and the urgent requirement to novel therapeutic approaches [3]. Currently, there remains a paucity of literature encompassing a comprehensive review of AITL. This review provides an overview of the pathogenesis, histopathological features, clinical manifestations, treatment strategies, and recent research advancements of AITL to enhance our comprehension of this disease.

Pathological features and pathogenesis

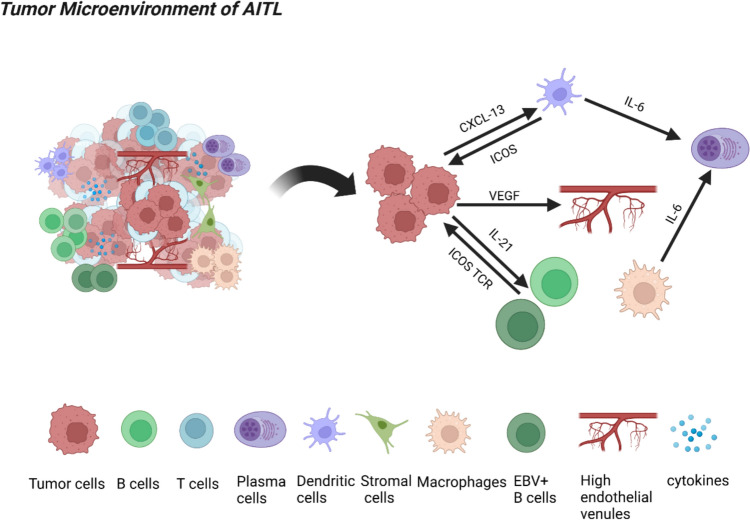

AITL has a unique tumor microenvironment with diverse immune and stromal components.

AITL displays unique pathological features, including a complex tumor microenvironment (TME) predominantly consisting of reactive hematopoietic cells, such as T and B cells, plasma cells, stromal components, and follicular dendritic cells (FDCs). Additionally, it exhibits marked arborization of high endothelial venules (HEVs) [2, 18]. Multinucleated Hodgkin lymphoma (HL)/Reed-Sternberg (RS)–like cells may be detected (Fig. 1) [19]. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection rarely affects malignant T cells but primarily targets reactive B cells. Large infected CD20+ immunoblastic cells, which morphologically mimic the RS cells of HL, are typically observed and stain positively for EBV-encoded RNA in most cases20–22. A limited proportion of neoplastic CD4+ Tfh cells, typically constituting 10% or less of the cellular population, are accompanied by extensive multi-lineage immune cells infiltration. The non-malignant TME exhibits aberrant large B cells, reactive CD8+ cells and immunoblasts [23]. Pathology of AITL is maintained through interactions between components of TME and cytokines released by neoplastic Tfh cells [18]. A recent study in China on CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in AITL demonstrated a positive correlation between the level of infiltration by CD8+ TILs and the extent of exhaustion, identified by increased expression of immune checkpoints (IC). This was associated with profound exhaustion-related biological processes [24]. High proportion of CD8+TILs was a significant risk factor for overall survival (OS) and elevated CTL levels were associated with a poor OS for AITL patients. This phenomenon may play an essential role in the unfavorable prognosis observed in patients exhibiting high CD8 + TILs and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) [24]. Therefore, this also provides certain insights for pathologists and hematologists, as the widely existing TME contributes to the identification of the disease. At the same time, non-tumor components in the microenvironment are equally worthy of attention, as they may be associated with patient prognosis and can be further explored through relevant preclinical researches.

Fig. 1.

Created in BioRender. https://BioRender.com/hqrt7be. AITL is characterized by a complex TME primarily composed of T cells, B cells, plasma cells, stromal components, and FDCs. Additionally, it exhibits prominent branching of HEVs, along with the presence of multinucleated HL/RS-like cells. The promotion of AITL is subsequently facilitated by the interaction between components within the TME and cytokines released by tumor cells

For histopathology, three patterns can be observed in AITL which is distinguished by a partial or complete obliteration of the nodal architecture. Typical lymph nodes of AITL accounting for approximately 80% of cases exhibit complete structural disappearance (pattern III) and AITL encompasses two atypical subtypes: exhibiting hyperplastic follicles (pattern I) and depleted follicles (pattern II) [2]. Immunophenotypically, along with exhibiting the presence of pan-T-cell antigens such as CD3 and CD5, AITL tumor cells exhibit the expression of Tfh cell markers, including PD1, CXCR5, BCL-6, CD10, CXCL13, and ICOS-1 [15, 25]. PD1 and ICOS showed the highest sensitivity, while CXCL13 and CD10 displayed lower but higher specificity among various Tfh markers [19].

Genetic and chromosomal alterations define AITL’s molecular profile.

AITL pathogenesis adheres to a two-hit model, where early epigenetic regulator mutations such as ten-eleven translocation-2 (TET2) and DNA methyltransferase 3A (DNMT3A) in hematopoietic progenitors and promote clonal expansion, creating a pre-malignant field. Secondary mutations—most notablyras homolog family member A (RHOA) and isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 (IDH2)—emerge within the Tfh cell lineage, driving malignant transformation [7, 12, 26]. (Fig. 2). Subsequently, Tfh cells initiate the production of cytokines and chemokines, including interleukin(IL)-6, IL-21, CXCL-13, as well as VEGF, in order to regulate the intricate network between Tfh cells and TME, ultimately facilitating the progression of AITL [7].

Fig. 2.

Created in BioRender. https://BioRender.com/o15xtf2. The multistep tumorigenesis theory of AITL posits that initial mutations occur in pre-cancerous cells, followed by subsequent mutations in T-cell functional genes. AITL is characterized by early stage hematopoietic stem-cell mutations in TET2 and DNMT3A, which are then followed by the detection of RHOA and IDH2 mutations in the Tfh cell population

TET2 gene mutations are the predominant occurrences in AITL, accounting for approximately 50% to 75% of cases, and are typically linked to adverse prognosis [20, 27]. The findings based on a study assessing the Tet2-deficient immune cells suggest that Tet2-deficient immune cells contribute to promoting the development of Tfh-like lymphoma in mice with RHOAG17V and Tet-2 deletion in all blood cells [15]. RHOA gene encodes a highly conserved guanosine triphosphatase, which belongs to the RAS superfamily and plays roles in regulating cell survival, cell cycle progression, and cytoskeleton dynamics [28, 29]. A previous meta-analysis has demonstrated a robust correlation between RHOAG17V mutation and the Tfh phenotype of AITL [29]. RHOAG17V mutations, among these genetic alterations, are also frequently detected in other T-cell lymphomas with Tfh phenotypes; however, their occurrence is rare in other types of cancers [30]. This genetic indicator is therefore regarded as a distinctive feature and diagnostic marker for Tfh lymphoma. RHOAG17V demonstrates a significant correlation with TET-2 [14], as well as IDH2; however, it is unrelated to DNMT3A mutations [29]. Mutations in IDH2 are limited to Arg172, and this specific mutation is predominantly observed in AITL [21]. IDH2 mutations aid in differentiating AITL from other Tfh-phenotype lymphomas [29]. In the Idh2/Tet2 double-mutant mouse model, malignant Tfh cells exhibit aberrant epigenetic and transcriptomic programs, including upregulation of B-cell helper cytokines and increased angiogenesis [18]. AITL sequencing studies have proved mutations in T-cell receptor (TCR) pathway genes comprising phospholipase C gamma 1 (PLCG1) gene, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) regulatory, CD28, and other genes [31].

The most frequently observed chromosome abnormalities in AITL include gain of Chromosome (chr) 5q, concurrent trisomies of 5 and 21, as well as loss of 6q [12]. Previous studies have indicated that the gain of chr5 in AITL is unique, as chr5-loss is typically seen in other hematological malignancies [26]. Co-occurrence of IDH2R172 mutation was observed in AITL with chr5 and chr21, while cases with wild-type IDH2 exhibited deletions targeting PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway [26]. In cases with chr5-gain, GEP analysis revealed a significant upregulation of genes such as IL4, IL13, and MAPK9, which are implicated in regulating cell cycle progression and T-cell differentiation (P < 0.05) [26]. Also, a significant association was found between chr5 and IDH2R172 mutation (P = 0.01); however, no association was found with recurrent mutations in DNMT3A, RHOAG17V, or TET2 [26]. By elucidating the immunophenotypes, cytogenetics and molecular genetics features of AITL, a more comprehensive understanding of its pathogenic signaling pathways can be attained. This will facilitate the selection of pertinent therapeutic agents based on specific targets and enable the implementation of clinical trials to enhance prognosis of AITL patients.

Clinical manifestations and laboratory features

Previous research has described AITL as a “protean” lymphoma because of a wide variety of clinical manifestations and laboratory features [14]. Only ~ 10% of AITL cases are diagnosed at early stage, and the majority of cases have advanced stage disease. It typically presents as a systemic disorder, with involvement of lymph nodes, B symptoms and often affects extranodal sites [14, 32]. Lymphadenopathy observed on computed tomography (CT) scans is usually mild, ranging from 1.5 to 3 cm in size [14].

Skin lesions occur in about 50% of cases, manifesting as macules, papules, or plaque-like/nodular rashes [33]. Sometimes, cutaneous involvement, a frequent extranodal manifestation of AITL, presents as the initial complaint[8]. The variable clinical and histopathological manifestations present diagnostic challenges, especially when these findings occur prior to lymph node biopsy. In a study [32] on the immunophenotypes of 19 patients with dermatological manifestations of AITL, it was observed that nearly all AITL skin infiltrations exhibited expression of at least two Tfh markers. Furthermore, there were variations in the degree of expression among the three Tfh markers. The greatest level of sensitivity was detected for PD-1, followed by BCL6, while CD10 showed comparatively lower levels. There was also a study of the impact of EBV positivity on clinicopathologic characteristics suggesting that the rate of EBV positivity in tumor tissue was notably more prevalent among individuals exhibiting skin involvement [34]. Moreover, results of EBV in situ hybridization (ISH) at the primary tumor location were positive in all patients who had EBV-positive skin lesions [34].

Approximately up to 70% of patients exhibit bone marrow involvement [14]. Bone marrow of patients with AITL typically exhibits solitary or multiple loose nodular lymphoid infiltrates, characterized by a paratrabecular or interstitial distribution pattern [30]. In some different case reports, it has been observed that patients with AITL may exhibit hypereosinophilia, while AITL itself can lead to the development of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) [35, 36]. HLH is frequently observed in AITL, with an incidence rate of 6.1% [37]. As reported in a case study [35], AITL-induced HLH may be complicated by DIC and exhibit characteristics of rapid progression. The patient’s condition can deteriorate significantly within a few weeks. Consequently, early identification and timely diagnosis, such as through the measurement of serum ferritin and soluble CD25, are critical. Simultaneously, combining standard HLH treatment regimens with lymphoma-specific therapy plays a pivotal role in improving patient outcomes. AITL is characterized by high VEGF expression, which drives angiogenesis—as evidenced by branched HEV proliferation—and supports lymphoma proliferation via autocrine/paracrine signaling [20, 38, 39]. Therefore, AITL patients will exhibit characteristic clinical manifestations accordingly. Furthermore, because of the potential occurrence of peripheral blood involvement in AITL, scholars have suggested that the differential diagnosis between AITL and CD4+ T-lymphoproliferative disorders exhibiting hyperlobated nuclei necessitates attention [40]. Circulating cells in the involved peripheral blood, determined by flow cytometry, typically exhibit a sCD3−/CD4+/CD10+ profile [7].

AITL was initially classified as an immunodysplastic syndrome (LDS), and the term LDS was suggested for its nomenclature [2]. The typical immune disorders of AITL result in immunodeficiency, rendering individuals more susceptible to bacterial and fungal infections as well as opportunistic pathogens [7]. AITL can also be characterized by immune activator, leading to an elevated sedimentation rate, elevated LDH, and positive results in autoimmune tests [14]. AITL is frequently accompanied by polyclonal plasmacytosis and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia [41]. Although less common, monoclonal gammopathy has been documented in some cases, with the potential for clonal plasmacytosis [14]. Cases with hypogammaglobulinemia have also been observed [42]. For autoimmune phenomena, hemolytic anemia, immune thrombocytopenia, polyarthritis, vasculitis, and thyroid abnormalities may also occur in AITL [12, 30]. Moreover, the statement demonstrates that a correlation has been reported between solid tumors and lymphoma, such as colorectal tumors and mesothelioma [43]. Also, there has been a case reported AITL occurring in a patient with thyroid cancer [43]. Therefore, due to the diverse clinical manifestations of AITL, it poses difficulties for clinicians to identify the disease, emphasizing the significance of accurate diagnosis and differential diagnosis.

Diagnosis

Accurately diagnosing AITL is challenging due to its broad range of clinical symptoms and histopathological changes, which may resemble those of various benign diseases, including autoimmune disease, infection, and malignant lymphoid proliferative disorders. The diagnosis is determined by conducting a biopsy on the involved tissue. Lack of diagnostic specificity in skin biopsy for cutaneous AITL necessitates reliance on lymph node biopsy with clinicopathological relevance for accurate diagnosis of AITL [42]. The preferred method for diagnosing AITL is the excision of lymph node biopsy. Subsequently, the tissue is subjected to histopathological analysis, immunohistochemical tests, ISH for EBV, and either Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing (NGS) for mutated genes [7].

AITL exhibits a diverse range of antigens associated with Tfh cells, and it is recommended that tumor cells express a minimum of two, preferably three, of these antigens including PD-1, CD10, CXCL-13, BCL-6, ICOS, SAP, and CXCR-57. A study [44] conducted in China which focused on the prognostic markers for PTCL subtypes differential diagnosis based on flow cytometric immunophenotyping analyzed these markers and subtypes of PTCLs. For AITL, the expression of characteristic markers PD-1 and CD10 is typically observed in clonal T cells with a CD4 + phenotype, while CD5 is less likely to be lost. By establishing a cut-off value for PD-1 and CD10, AITL can be distinguished from T-cell clones of uncertain significance (T-CUS). When the percentage of PD-1+ exceeds 38.01 or the percentage of CD10+ exceeds 7.46, the identification of AITL is effectively achieved. The PD-1 bright + CD10+ T-cell population demonstrates high sensitivity and specificity in effectively identifying other subtypes of PTCLs or T-CUS. Integration of CD3(-/dim) CD4+ with PD-1 and CD10 enables a comprehensive diagnosis of AITL cells. Moreover, this research indicated that the presence of CD7 and CD38 demonstrated prognostic significance. Refining the earlier gene signature for AITL, GEPs on a significantly larger series resulted in the reclassification of 14% of PTCL–not otherwise specified (NOS) cases as AITL [45]. High-sensitivity flow cytometry can substantially enhance the diagnostic accuracy of AITL. A certain study showed that in suspected cases, the abnormal high expression of PD-1 in CD4 + T cells in peripheral blood or bone marrow was helpful for sensitively differentiating AITL from other T-cell diseases [46]. Moreover, in patients with B-cell lymphoma or reactive follicular hyperplasia, no significant PD-1-expressing abnormal T cells were detected. For AITL cases that are challenging to diagnose initially using morphology and immunohistochemistry alone, flow cytometry effectively identifies features characteristic of AITL. Further investigations indicated that all cases exhibited at least one mutation in genes such as RHOA, TET2, IDH2, or DNMT3A, as identified through NGS, corroborating the findings obtained via flow cytometry. The integration of these techniques with histopathological analysis significantly improves both the accuracy and reliability of AITL diagnosis. The presence of CD28 mutations in AITL for TCR pathway genes was further confirmed by others, albeit at a lower frequency in PTCL-NOS [31]. Other study [47] of Tfh markers suggested that, histologically, the lichenoid architecture was more likely to be suggestive of primary cutaneous T‑follicular helper derived lymphoma (PCTFHL) or primary cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder with small/medium CD4+ T‑cells (SMLPD) than cutaneous AITL (cAITL), where interstitial structure was more common. In this research, BCL6 in cAITL and PCTFHL was significantly higher than that of SMLPD and CD10 expression was observed exclusively in PCTFHL and cAITL. Besides, it is worth noting that a differential diagnosis between AITL and classical HL (CHL) is necessary. In addition to the expression pattern of Tfh markers described above, one study also revealed that MUM1 was expressed in RS-like cells in AITL and formed the rosettes surrounding these cells within neoplastic T cells [48]. In CHL, however, while MUM1 was expressed in RS cells, this rosette structure was rarely observed. The microenvironment of AITL is distinguished by the presence of HEVs and significant proliferation of FDCs, while CHL usually lacks these features [49].

The utilization of positron emission tomography (PET) scanning, which provides benefits for disease stage but is not obligatory, can be employed to identify nodal or extranodal lesions that may go unnoticed during CT evaluation [20]. A research [50] aiming to evaluate 18F-FDG PET/CT in assessing bone marrow involvement in AITL indicated that PET/ bone marrow positivity obviated the necessity for repeating bone marrow biopsy to confirm its involvement. However, a negative PET/bone marrow result does not definitively exclude the possibility of bone marrow involvement. Combination of bone marrow biopsy and 18F-FDG PET/CT can enhance diagnostic accuracy of bone marrow involvement in AITL patients.

The clinical and histological manifestations of AITL usually resemble those of an infectious process. Aforementioned statement suggests a potential association between EBV infection and AITL. There have been reports indicating the simultaneous presence of EBV and human herpes virus 6 (HHV-6) in AITL and discovering that HHV-6 is capable of inducing AITL, facilitating disease progression, or both [51]. Therefore, accurate identification of viral inclusions is crucial. Failure to do so may result in diagnostic challenges, such as misdiagnosing viral lymphadenitis as T-cell lymphoma or HL. Additionally, failure to recognize other features of lymphoma in the presence of infection can also occur [51].

As mentioned above, the presence of AITL is frequently accompanied by coexisting conditions, particularly immune-related disorders and neoplasms. Integration of clinical, laboratory, and pathologic results, such as the utilization of blood tests, imaging examinations, specific immunohistochemical tests, and genetic alterations, including fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for chromosomal abnormalities, can be instrumental in the accurate diagnosis of AITL.

Prognostic factors and outcomes

At present, various predictive models exist; however, the prognosis of AITL remains generally unfavorable. Rapid disease progression renders conventional chemotherapy less effective and leads to a poor prognosis. Median survival is below 3 years, and the percentage of patients who survive beyond 5 years after diagnosis is only between 10 and 30% [52]. Commonly used prognostic tools include the IPI, the Prognostic Index for AITL (PIAI) and the Prognostic Index for T-cell lymphoma (PIT) [1, 7, 14].

Previous study has demonstrated that progression of disease within 24 months from diagnosis (POD24) holds substantial prognostic value for AITL patients, showing that the 5-year OS and progression-free survival (PFS) rates are estimated at 63% and 48%, respectively, for those who do not experience POD24, compared to 6% and 2%, respectively, for patients who experience POD24 [1]. In the same study, a new prognostic scoring model (AITL score) was established through multivariate analysis and integration of age, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, β2-microglobulin, and C-reactive protein (CRP). Based on risk stratification subgroups, significant disparities were observed in the OS and PFS outcomes among patients. This score demonstrated superior prognostic discrimination compared to the IPI/PIT/PIAI. The 5-year PFS rate for patients with a high-risk AITL score was 13%, which is significantly lower than that observed in the high-risk IPI, PIT, and PIAI groups (ranging from 24 to 27%). A scoring model specifically designed to account for the characteristics of AITL can more precisely stratify patient prognosis. Findings from a retrospective study [53] conducted in China on a predictive model for AITL demonstrated that the survival outcomes of AITL patients could be stratified by integrating extranodal sites, bone marrow involvement, as well as performance status. Patients were divided into three groups (based on the number of adverse factors), the 5-year OS rates were 86.9%, 46.3%, and 16.2% (P < 0.0001). This study suggested that compared to the IPI score, the new prognostic model demonstrated improved performance in achieving a more balanced distribution of patients across different risk groups. A study [54] conducted by another center in China revealed that pneumonia and serous cavity effusions present during initial diagnosis are identified as important prognostic indicators for OS. Therefore, experts should conduct further research on VEGF in order to improve patients’ symptoms and prognosis. The diagnostic role of PET in AITL has been mentioned above, and there was research also exploring the prognostic role of PET-CT [55]. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that total metabolic tumor volume (TMTV) and PIT were identified as independent factors of PFS and OS in AITL. Furthermore, the integration of TMTV and PIT may potentially enhance risk stratification efficacy. The findings of researches warrant the attention of Chinese scholars, aiming to develop a prognostic model of risk stratification that is better suited for Chinese AITL patients. This will effectively discern patient survival disparities and enhance patient prognosis.

The association between EBV and AITL has been established; however, the influence of EBV on its prognosis remains uncertain. A retrospective analysis [56] conducted in Korea examined the effect of EBV positivity on the prognosis of newly diagnosed AITL and PTCL-NOS. Tissue sections were subjected to ISH testing, while blood samples underwent polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays analysis in this research. Subgroup analysis revealed significant variations in complete response (CR) rates among patients who tested positive for PCR or not. The rate of recurrence was elevated in patients with positive ISH results than those with negative ISH results among patients who tested negative for PCR. Patients with EBV-positive PTCL have a worse prognosis, as their 3-year PFS rate is lower compared to those who are EBV-negative. Results of this study are worthy of attention in East Asian countries, and further multi-center studies should be conducted to explore the effect of EBV positivity on the prognosis of AITL, while optimizing the selection of tissues and methods. Clinical significance of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) has increasingly garnered attention in the prognostic prediction and disease monitoring of PTCL patients. The presence of ctDNA prior to treatment lies in its ability to function as a predictive factor for the prognosis of PTCL patients and relapsed patients exhibit higher levels of ctDNA compared to those who have achieved sustained remission [57]. For instance, a certain study has shown that tumor-specific ctDNA mutations can be detected in the plasma of 77% of AITL patients [58]. The study further found that a decrease of ≥ 1.5-log in ctDNA levels at the end of treatment was closely associated with significantly improved survival. This result suggests that ctDNA may become an effective indicator for monitoring minimal residual disease (MRD) in AITL. Additionally, ctDNA detection methods targeting AITL-specific mutations (such as RHOA G17V) can be used to assist in diagnosis and the monitoring of early recurrence [59].

Moreover, for AITL, a comprehensive model including IPI and B cells genes (BLK, CD19 and MS4A1) was obtained by Cox multivariate analysis from a study of prognostic models for PTCL originating from Spain [60]. Then, these AITL patients were subsequently classified into high or low-risk groups based on their median risk score. High-risk group had shorter OS and time to progression (TTP). Furthermore, the distinctions among the three PTCL subclasses PTCL-NOS, AITL and PTCL-TFH were confirmed by gene expression and mutational analysis. Primary distinction lies in the prevalence of the RHOAG17V mutation, which is approximately twice as common in AITL compared to PTCL-TFH, but remains undetectable in PTCL-NOS. The favorable prognosis is likely attributed to the B-cell signature, which may reflect either an early stage of the disease or T-cell cytokines released to facilitate B-cell proliferation [45]. An immunosuppressive signature in AITL patients is associated with unfavorable clinical outcomes, and targeting this immunosuppressive microenvironment may enhance antitumor immunity [45]. This provides some insights for treatment strategy selection. According to the above content, there exist diverse predictive models that can be applied to the prognostic factors of AITL, and the indicators may vary. Clinical researchers have the option to select large-scale data for validation and identify prognostic indicators that are more suitable for their specific patients.

Treatment

The selection of first-line treatment is based on patient characteristics.

Treatment options for AITL patients are based on the age, physical status, and presence of comorbidities. Based on the recommendations provided by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the preferred initial treatment strategy for AITL patients is their inclusion in clinical trials [61]. For young or in favorable performance status, first-line treatment typically involves the administration of anthracycline-containing chemotherapy regimens, such as cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (CHOP) or CHOP-like regimens, incorporating autologous stem-cell transplantation (ASCT), or not [62]. The use of anthracycline drugs is not recommended for elderly patients due to factors such as comorbidities and poor baseline physical condition. In recent years, researchers have implemented a diverse range of treatment strategies and incorporated additional drugs into the CHOP regimen. For example, there was a study [63] from the Netherlands to explore the effect of combining rituximab with CHOP regimen or CHOP plus etoposide (CHOEP) on AITL survival. Inclusion of rituximab led to an enhancement in overall response rate (ORR); however, it did not lead to a statistically significant enhancement in survival. The addition of etoposide to CHOP was discovered to enhance 3 years event free survival (EFS) for aged ≤ 60 years PTCL patients from a German study [64] and demonstrated an advantageous PFS in PTCL patients ≤ 60 years from a Sweden real-world data [65]. However, there was no discernible advantage observed in terms of OS or PFS when extending the age limit in this Sweden study. For PTCL patients with CD30+, the incorporation of brentuximab vedotin into cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (CHP) improved PFS and OS [66]. However, there was no observed improvement in PFS or OS for AITL patients. Thus, it can be observed that the benefits of combining other chemotherapy drugs or novel agents based on chemotherapy remain inconclusive, including whether there is an improvement in ORR for patients, the identification of specific drugs that enhance patient OS, the determination of an appropriate age cutoff value when combining with other drugs. Additionally, the majority of studies have examined patients encompassing all subtypes of PTCL, with limited subgroup analyses specifically focusing on AITL. These aspects still require extensive clinical studies and real-world data for verification.

The efficacy of ASCT in AITL remains controversial.

The impact of ASCT on AITL, however, continues to be a subject of ongoing debate [63]. ASCT as a first-line consolidation therapy appears to offer benefits for AITL patients who attain a minimum of partial response (PR) following induction therapy [20]. Although multiple retrospective, prospective studies have evaluated ASCT as a post-remission consolidation therapy, the specific patient population that truly benefits from this approach remains unclear. A retrospective study from a multi-center in Europe collected 269 patients ≤ 65 years with PTCL, who were diagnosed between the years 2000 and 2015, including 123 patients with AITL. No significant differences were detected in OS and PFS among cases without or with ASCT [67]. The COMPLETE study [68], a prospective United States study, recruited a total of 499 PTCL patients from 56 centers between February 2010 and February 2014. Out of the 119 individuals diagnosed with nodal PTCL, those who attained CR1 following initial treatment, 36 underwent ASCT while the remaining 83 did not receive ASCT. Additionally, there were 35 patients diagnosed with AITL. Notably, the administration of ASCT demonstrated a significant enhancement specifically in AITL patients but did not demonstrate similar benefits in other subtypes of PTCL. In the ASCT cohort, median OS and PFS were not reached for AITL patients, while in the non-ASCT group, the median OS and PFS were 24.3 months (P < 0.01) and 18.6 months (P = 0.10), respectively. In another prospective study [69] from Korea of Asia, a cumulative count of 191 PTCL patients were recruited from May 2015 to April 2018, including 60 AITL (31.4%). PFS of AITL patients who underwent ASCT was significantly higher compared to those without ASCT, while there was no statistically significant difference in OS between the two cohorts (Table 1). Therefore, it is necessary to conduct further prospective studies on patients with AITL undergoing ASCT, analyze the depth of response, age, comorbidities, and other factors, and perform stratified evaluations to clarify the influencing factors of transplantation outcomes. For allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (allo-HSCT), the increase in treatment-related mortality outweighed the beneficial impact of using first-line allo-HSCT as consolidation therapy [70].

Table 1.

Studies evaluating ASCT as a post-remission consolidation therapy

| Regions | Study design | Therapeutic approaches | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Europe, 2018 | retrospective, 269 PTCL (123 AITL) | ASCT vs. non-ASCT |

OS: 5 years OS rates of 59.2% vs. 60.4% PFS: 5 years PFS rates of 46.3% vs. 40.5% (For PTCL) |

| United States, 2019 | prospective, 35 AITL | ASCT vs. non-ASCT |

OS: NR vs. 24.3 months PFS: NR vs. 18.6 months |

| Korea, 2023 | prospective, 60 AITL | ASCT vs. non-ASCT |

OS: 3-year OS rates of 85.1% vs. 83.3% PFS: 3-year PFS rates of 77.4% vs. 28.6% |

AITL, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; ASCT, autologous stem-cell transplantation; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; NR, not reached

The treatment of R/R AITL requires individualized strategies, with targeted therapies offering new options.

Recent years have witnessed the evaluation of various treatment strategies for relapsed/refractory (R/R) AITL accompanied by a multitude of ongoing multistage clinical trials. NCCN guidelines strongly advocate prioritizing participation in clinical trials as the primary option [61]. Transplant-eligible patients outside trials receive second-line salvage chemotherapy followed by consolidation with ASCT or allo-HSCT [66]. Recently, a retrospective real-world study conducted in China across multiple centers evaluated the efficacy of HSCT in 408 patients diagnosed with PTCL, whose median age was 45.5 years old [71]. A total of 127 patients with nodal PTCL exhibited a positive response to initial treatment (the "responders"), and among them, 47 patients (37.0%) underwent consolidation therapy through HSCT, including ASCT (93.6%) and allo-HSCT (6.4%). In nodal PTCL responders, first-line ASCT held promise for achieving long-term disease control as evidenced by the plateauing of both PFS and OS curves. Responders who underwent ASCT demonstrated superior median OS and PFS compared to those who did not undergo the procedure. Among 80 responders with non-nodal PTCL who underwent HSCT, a total of 26 patients (32.5%) received HSCT, with 46.2% undergoing allo-HSCT and 53.8% opting for ASCT. For non-nodal PTCL responders, first-line allo-HSCT demonstrated superior outcomes compared to ASCT. It resulted in significantly longer PFS of 82.7 months compared to 15.8 months (P = 0.031), along with a substantially lower 3-year cumulative incidence of relapse (CIR) at 16.7% versus 56.0%. Non-relapse mortality (NRM) rates were comparable between the two groups at 10.4% and 11.0%, respectively. HSCT patterns following second-line therapy exhibited significant variability. The comparison of ASCT with allo-HSCT after salvage therapy in patients with PTCL posed challenges because of the inherent bias in selecting HSCT among different disease subtypes. The prognosis was unfavorable for patients who underwent HSCT after receiving three or more lines of therapy.

There is a diverse range of targeted drugs in R/R AITL, each with distinct mechanisms and various molecular signaling pathways, especially epigenetic modulators and immune signaling inhibitors. Among these, several studies have indicated that histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, including romidepsin, belinostat, and tucidinostat (also known as chidamide), demonstrated relatively higher response rates in AITL compared to other PTCL subtypes. Chidamide, in particular, has shown consistent efficacy across both clinical trials and real-world studies, with ORRs in AITL patients approaching or exceeding 50%. Beyond HDAC inhibitors, other therapeutic approaches targeting JAK/STAT signaling (e.g., cerdulatinib, ruxolitinib, and golidocitinib), co-stimulatory molecules (e.g., anti-ICOS antibody MEDI-570), and metabolic regulators (e.g., tipifarnib and darinaparsin) have shown promising efficacy in early-phase clinical trials. While many of these agents exhibit acceptable safety profiles, hematologic toxicities such as neutropenia, lymphopenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia remain common, and careful monitoring is required in heavily pretreated patients. A summary of key clinical trials involving these agents, including study design, efficacy outcomes, and safety profiles, is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Studies on the efficacy of different agents in R/R AITL from diverse clinical trials

| Region | Study design | Therapeutic approaches | Patient responses | Outcomes | Main grade ≥ 3 adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America [62] | Phase I, 16 AITL | MEDI-570 | ORR: 44% | PFS: 2.9 m; OS: 17.1 m | ↓CD4 + T cells (57%), lymphopenia (26%) |

| United States [74] | Phase II, 45 PTCL and 7 MF | Ruxolitinib | ORR: 25%; CBR: 35% | PFS: 2.8 m; OS: 26.2 m | Neutropenia (19%), anemia (17%) |

| United States [75] | Phase II, 16 AITL | Romidepsin + Lenalidomide | ORR: 78.6%; CR: 35.7% | PFS: 1.4 yr; 2-yr PFS:38.1%; 2-yr OS: 61.4% | Neutropenia (45%), hyponatremia (45%) |

| Japan and Korea [76] | Phase II, 55 PTCL (10 AITL) | Tucidinostat | AITL ORR: 88% | PFS: 5.6 m; OS: 22.8 m | Thrombocytopenia (51%), neutropenia (36%), lymphopenia (24%) |

| China [77] | Phase II, 83 PTCL (10 AITL) | Tucidinostat | AITL ORR: 50%; CR/CRu: 40% | PFS: 2.1 m; OS: 21.4 m | Thrombocytopenia (22%), leukopenia (13%) |

| China [78] | Real-world, 383 PTCL | Chidamide mono/with chemo | AITL ORR: 49.2% | PFS: 144.5 / 176 days | Thrombocytopenia (10.2%/18.1%) |

| China [79] | Phase II, 24 AITL | Rituximab, Lenalidomide, Chidamide | ORR: 75%; CR: 20.8%; PR: 54.2% | PFS: 10.8 m; OS: NR | Not reported; all-grade hematological toxicity: leucopenia (35.7%), anemia (21.4%) |

| Asia [80] | Phase II, 17 AITL | Darinaparsin | ORR: 29.4% | PFS: 4.0 m; OS: 13.7 m | Anemia (15.4%), thrombocytopenia (13.8%) |

| US, Spain, Korea [81] | Phase II, 38 AITL | Tipifarnib | ORR: 56.3%; CR: 28.2%; PR: 28.1% | PFS: 3.6 m; OS: 32.8 m | Thrombocytopenia (34.2%), neutropenia (28.9%) |

R/R, relapsed/refractory; AITL, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; ORR, overall response rate; PFS, progression-free survival; m, months; OS, overall survival; PTCL, peripheral T-cell lymphoma; CBR, clinical benefit rate; CR, complete response; yr, years; CR/Cru, complete response/ unconfirmed complete response; mono, monotherapy; chemo, chemotherapy; PR, partial response; NR, not reached

Further randomized clinical studies are required to validate its efficacy and safety in the future. In addition to the aforementioned medications, there has been research conducted on other targeted drugs or novel agents, such as dasatinib, bendamustine, selinexor, anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody, and inhibitors of Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2), IC and PI3K. Therefore, for R/R AITL patients, the treatment options are more abundant, and the ORR and AEs are also different. The selection of an appropriate treatment regimen should take into account the patient's molecular genetic characteristics, individual physical condition, presence of comorbidities, ease of drug management, and any contraindications to medication in order to develop a personalized plan.

In recent years, new immunotherapies such as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T and CAR-NK therapies have gradually attracted wide attention in the academic community. The main obstacle encountered in CAR-T therapy for T-cell neoplasms lies in the shared antigens between tumor cells and normal T lymphocytes, contaminated with malignant T cells [7, 66]. Tumor antigens, such as CD4, are also expressed on effector T cells, potentially leading to fratricide in CAR-T therapy. Fratricide refers to mutual attacks among effector T cells or between effector T cells and normal T cells, which may restrict their expansion capacity and in vivo persistence. To address this issue, a study employed an in vivo transduction strategy to specifically deliver the anti-CD4 CAR gene to CD8 + T cells. This approach not only successfully eradicated CD4 + malignant T cells mimicking AITL but also effectively prevented fratricide [72]. In addition, CAR-T cells may induce a reduction in the expression of targeted antigens via the trogocytosis process, potentially resulting in disease recurrence. Research has demonstrated that designing low-affinity CARs can partially mitigate this effect [73]. NK cells lack the expression of TCR/CD3 complexes and CD4, thereby positioning CAR-NK cells as a promising alternative treatment strategy. Therefore, further investigation is warranted to explore the promising prospects of CAR-T or CAR-NK therapies in order to enhance outcomes for AITL patients.

Conclusion

AITL is a PTCL subtype with geographical variations originating from Tfh cells and exhibits an unfavorable overall prognosis. Researchers have unveiled the stepwise transformation process of AITL, from the initial hit to the subsequent hit events, and identified distinct genetic alterations that offer potential for targeted drug investigation. AITL has diverse clinical manifestations and needs to be differentiated from a variety of benign and malignant diseases. Currently, apart from clinical trials, anthracyclines remain the primary treatment for AITL patients. The role of ASCT as a consolidation therapy following remission remains contentious. For R/R AITL patients, ASCT and allo-HSCT can be considered, and a range of agents is available; however, certain ones are currently undergoing investigational clinical trials, although some progress has been achieved. Prospective studies should be conducted to further explore novel therapeutic modalities, including the exploration of new agents, as well as the utilization of CAR-T and CAR-NK therapies in order to improve prognosis of AITL in the near future.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AITL

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma

- PTCL

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma

- Tfh

Follicular T helper

- TME

Tumor microenvironment

- R/R

Relapsed/refractory

- GEP

Gene expression profiling

- GC

Germinal center

- WHO

World Health Organization

- nTFHL-AI

Nodal T-follicular helper cell lymphoma, angioimmunoblastic-type

- NK/T

Natural killer/T-cell

- ACH

Age-related clonal hematopoiesis

- HSPCs

Hematopoietic stem or progenitor cells

- FDCs

Follicular dendritic cells

- HEVs

High endothelial venules

- HL

Hodgkin lymphoma

- RS

Reed-Sternberg

- EBV

Epstein-Barr virus

- TILs

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

- IC

Immune checkpoints

- OS

Overall survival

- CTLs

Cytotoxic T lymphocytes

- TET2

Ten-eleven translocation-2

- DNMT3A

DNA methyltransferase 3A

- RHOA

Ras homolog family member A

- IDH2

Isocitrate dehydrogenase 2

- IL

Interleukin

- TCR

T-cell receptor

- PLCG1

Phospholipase C gamma 1

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- chr

Chromosome

- CT

Computed tomography

- ISH

In situ hybridization

- HLH

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

- DIC

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- LDS

Immunodysplastic syndrome

- NGS

Next-generation sequencing

- T-CUS

T-cell clones of uncertain significance

- NOS

Not otherwise specified

- PCTFHL

Primary cutaneous T‑follicular helper derived lymphoma

- SMLPD

Lymphoproliferative disorder with small/medium CD4 + T‑cells

- cAITL

Cutaneous AITL

- CHL

Classical HL

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- HHV-6

Human herpes virus 6

- FISH

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

- PIAI

Prognostic Index for AITL

- PIT

Prognostic Index for T-cell lymphoma

- POD24

Progression of disease within 24 months from diagnosis

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- TMTV

Total metabolic tumor volume

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- CR

Complete response

- ctDNA

Circulating tumor DNA

- MRD

Minimal residual disease

- TTP

Time to progression

- NCCN

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- CHOP

Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone

- ASCT

Autologous stem-cell transplantation

- CHOEP

CHOP plus etoposide

- ORR

Overall response rate

- EFS

Event free survival

- CHP

Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone

- PR

Partial response

- allo-HSCT

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation

- CIR

Cumulative incidence of relapse

- NRM

Non-relapse mortality

- HDAC

Histone deacetylase

- HMA

Hypomethylating agents

- Cru

Unconfirmed CR

- TEAE

Treatment emergent adverse events

- CBR

Clinical benefit rate

- SD

Stable disease

- RP2D

Recommended phase II dose

- DOR

Duration of response

- EZH2

Enhancer of zeste homolog 2

- CAR

Chimeric antigen receptor

Author contributions

Y.F drafted the manuscript and prepared the figures and tables. Y.M performed manuscript reviewing and editing. T.L, M.L, Z.H, and Q.Y conducted the investigation and validation. M.Z revised the manuscript and was in charge of the final approval of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81974005), the Beijing Xisike Clinical Oncology Research Foundation (Grant No. Y-SYBLD2022MS-0055), the Joint Fund for Innovation and Development of Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (Grant No. 2025AFD777).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors declare full consent for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Advani RH, Skrypets T, Civallero M, Spinner MA, Manni M, Kim WS, et al. Outcomes and prognostic factors in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: final report from the international T-cell Project. Blood. 2021;138(3):213–20. 10.1182/blood.2020010387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiba S, Sakata-Yanagimoto M. Advances in understanding of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Leukemia. 2020;34(10):2592–606. 10.1038/s41375-020-0990-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohmoto A, Fuji S. Cyclosporine for angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: a literature review. Expert Rev Hematol. 2019;12(11):975–81. 10.1080/17474086.2019.1652590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmitt N, Bentebibel SE, Ueno H. Phenotype and functions of memory Tfh cells in human blood. Trends Immunol. 2014;35(9):436–42. 10.1016/j.it.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song W, Craft J. T follicular helper cell heterogeneity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2024;42(1):127–52. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-090222-102834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crotty S. T follicular helper cell differentiation, function, and roles in disease. Immunity. 2014;41(4):529–42. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lage L, Culler HF, Reichert CO, Da SS, Pereira J. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma and correlated neoplasms with T-cell follicular helper phenotype: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic advances. Front Oncol. 2023. 10.3389/fonc.2023.1177590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Botros N, Cerroni L, Shawwa A, Green PJ, Greer W, Pasternak S, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: clinical and pathological characteristics. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37(4):274–83. 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris NL, Stein H, Siebert R, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127(20):2375–90. 10.1182/blood-2016-01-643569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alaggio R, Amador C, Anagnostopoulos I, Attygalle AD, Araujo I, Berti E, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization classification of haematolymphoid tumours: lymphoid neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022;36(7):1720–48. 10.1038/s41375-022-01620-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Federico M, Rudiger T, Bellei M, Nathwani BN, Luminari S, Coiffier B, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: analysis of the international peripheral T-cell lymphoma project. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(2):240–6. 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.3647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohammed SM, Kotb A, Abdallah G, Muhsen IN, El FR, Aljurf M. Recent advances in diagnosis and therapy of angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma. Curr Oncol. 2021;28(6):5480–98. 10.3390/curroncol28060456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vose J, Armitage J, Weisenburger D. International peripheral T-cell and natural killer/T-cell lymphoma study: pathology findings and clinical outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(25):4124–30. 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.4558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lunning MA, Vose JM. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: the many-faced lymphoma. Blood. 2017;129(9):1095–102. 10.1182/blood-2016-09-692541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujisawa M, Nguyen TB, Abe Y, Suehara Y, Fukumoto K, Suma S, et al. Clonal germinal center B cells function as a niche for T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2022;140(18):1937–50. 10.1182/blood.2022015451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu B, Liu P. No survival improvement for patients with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma over the past two decades: a population-based study of 1207 cases. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3): e92585. 10.1371/journal.pone.0092585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Leval L, Parrens M, Le Bras F, Jais JP, Fataccioli V, Martin A, et al. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma is the most common T-cell lymphoma in two distinct French information data sets. Haematologica. 2015;100(9):e361–4. 10.3324/haematol.2015.126300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leca J, Lemonnier F, Meydan C, Foox J, El GS, Mboumba DL, et al. IDH2 and TET2 mutations synergize to modulate T Follicular Helper cell functional interaction with the AITL microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2023;41(2):323–39. 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang E, Yang VS, Ong SY, Kang HX, Lim BY, de Mel S, et al. Clinical features and prognostic outcomes of angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma in an Asian multicenter study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2023;64(11):1782–91. 10.1080/10428194.2023.2235043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broccoli A, Zinzani PL. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2017;31(2):223–38. 10.1016/j.hoc.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donner I, Katainen R, Kaasinen E, Aavikko M, Sipilä LJ, Pukkala E, et al. Candidate susceptibility variants in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Fam Cancer. 2019;18(1):113–9. 10.1007/s10689-018-0099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lemonnier F, Mak TW. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: more than a disease of T follicular helper cells. J Pathol. 2017;242(4):387–90. 10.1002/path.4920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pritchett JC, Yang ZZ, Kim HJ, Villasboas JC, Tang X, Jalali S, et al. High-dimensional and single-cell transcriptome analysis of the tumor microenvironment in angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma (AITL). Leukemia. 2022;36(1):165–76. 10.1038/s41375-021-01321-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu Q, Yang Y, Deng X, Chao N, Chen Z, Ye Y, et al. High CD8(+)tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes indicate severe exhaustion and poor prognosis in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Front Immunol. 2023. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1228004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng S, Zhang W, Inghirami G, Tam W. Mutation analysis links angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma to clonal hematopoiesis and smoking. Elife. 2021. 10.7554/eLife.66395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heavican TB, Bouska A, Yu J, Lone W, Amador C, Gong Q, et al. Genetic drivers of oncogenic pathways in molecular subgroups of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2019;133(15):1664–76. 10.1182/blood-2018-09-872549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Odejide O, Weigert O, Lane AA, Toscano D, Lunning MA, Kopp N, et al. A targeted mutational landscape of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2014;123(9):1293–6. 10.1182/blood-2013-10-531509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee GJ, Jun Y, Yoo HY, Jeon YK, Lee D, Lee S, et al. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma-like lymphadenopathy in mice transgenic for human RHOA with p.Gly17Val mutation. Oncoimmunology. 2020;9(1): 1746553. 10.1080/2162402X.2020.1746553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nguyen PN, Tran N, Nguyen T, Ngo T, Lai DV, Deel CD, et al. Clinicopathological implications of RHOA mutations in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: a meta-analysis: RHOA mutations in AITL. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2021;21(7):431–8. 10.1016/j.clml.2021.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xie Y, Jaffe ES. How i diagnose angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2021;156(1):1–14. 10.1093/ajcp/aqab090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Timmins MA, Wagner SD, Ahearne MJ. The new biology of PTCL-NOS and AITL: current status and future clinical impact. Br J Haematol. 2020;189(1):54–66. 10.1111/bjh.16428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oishi N, Sartori-Valinotti JC, Bennani NN, Wada DA, He R, Cappel MA, et al. Cutaneous lesions of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: Clinical, pathological, and immunophenotypic features. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46(9):637–44. 10.1111/cup.13475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stoll JR, Willner J, Oh Y, Pulitzer M, Moskowitz A, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Part I: clinical and histologic features and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(5):1073–90. 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.04.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee WJ, Won KH, Choi JW, Won CH, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. Cutaneous angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: Epstein-Barr virus positivity and its effects on clinicopathologic features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(4):989–97. 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang M, Wan JH, Tu Y, Shen Y, Kong FC, Zhang ZL. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma induced hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy: a case report. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11(5):1086–93. 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i5.1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eng V, Kulkarni SK, Kaplan MS, Samant SA, Sheikh J. Hypereosinophilia with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;124(5):513–5. 10.1016/j.anai.2020.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knauft J, Schenk T, Ernst T, Schnetzke U, Hochhaus A, La Rosée P, et al. Lymphoma-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (LA-HLH): a scoping review unveils clinical and diagnostic patterns of a lymphoma subgroup with poor prognosis. Leukemia. 2024;38(2):235–49. 10.1038/s41375-024-02135-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poullot E, Milowich D, Lemonnier F, Bisig B, Robe C, Pelletier L, et al. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma and Kaposi sarcoma: a fortuitous collision? Histopathology. 2024;84(3):556–64. 10.1111/his.15083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cortés JR, Palomero T. The curious origins of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Curr Opin Hematol. 2016;23(4):434–43. 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liapis K, Paterakis G. Circulating angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma cells. Blood. 2020;135(18):1607. 10.1182/blood.2020004944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huppmann AR, Roullet MR, Raffeld M, Jaffe ES. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma partially obscured by an Epstein-Barr virus-negative clonal plasma cell proliferation. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(2):e28–30. 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Henrie R, Cherniawsky H, Marcon K, Zhao EJ, Marinkovic A, Pourshahnazari P, et al. Inflammatory diseases in hematology: a review. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2022;323(4):C1121–36. 10.1152/ajpcell.00356.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han P, Yang L, Yan W, Tian D. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma mimicking drug fever and infectious etiology after a thyroidectomy: a case report. Medicine. 2019;98(34): e16932. 10.1097/MD.0000000000016932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pu Q, Qiao J, Liu Y, Cao X, Tan R, Yan D, et al. Differential diagnosis and identification of prognostic markers for peripheral T-cell lymphoma subtypes based on flow cytometry immunophenotype profiles. Front Immunol. 2022. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1008695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iqbal J, Wilcox R, Naushad H, Rohr J, Heavican TB, Wang C, et al. Genomic signatures in T-cell lymphoma: how can these improve precision in diagnosis and inform prognosis? Blood Rev. 2016;30(2):89–100. 10.1016/j.blre.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yabe M, Gao Q, Ozkaya N, Huet S, Lewis N, Pichardo JD, et al. Bright PD-1 expression by flow cytometry is a powerful tool for diagnosis and monitoring of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Blood Cancer J. 2020;10(3):32. 10.1038/s41408-020-0301-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Donzel M, Trecourt A, Balme B, Harou O, Mauduit C, Bachy E, et al. Deciphering the spectrum of cutaneous lymphomas expressing TFH markers. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):6500. 10.1038/s41598-023-33031-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang W, Xie J, Xu X, Gao X, Xie P, Zhou X. MUM-1 expression differentiates AITL with HRS-like cells from cHL. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(9):11372–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carbone A, Gloghini A, Cabras A, Elia G. Differentiating germinal center-derived lymphomas through their cellular microenvironment. Am J Hematol. 2009;84(7):435–8. 10.1002/ajh.21434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liang X, Yang C, Su M, Zou L. Diagnosis of bone marrow involvement in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma should be based on both [(18)F]FDG-PET/CT and bone marrow biopsy findings. Curr Med Res Opin. 2024;40(5):803–11. 10.1080/03007995.2024.2337670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Balakrishna JP, Bhavsar T, Nicolae A, Raffeld M, Jaffe ES, Pittaluga S. Human herpes virus 6 (HHV-6)-associated lymphadenitis: pitfalls in diagnosis in benign and malignant settings. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42(10):1402–8. 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iannitto E, Ferreri AJ, Minardi V, Tripodo C, Kreipe HH. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;68(3):264–71. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hong H, Fang X, Wang Z, Huang H, Lam ST, Li F, et al. Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: a prognostic model from a retrospective study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018;59(12):2911–6. 10.1080/10428194.2018.1459610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun J, He S, Cen H, Zhou D, Li Z, Wang MY, et al. A novel prognostic model for angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: A retrospective study of 55 cases. J Int Med Res. 2021;49(5):675893094. 10.1177/03000605211013274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gong H, Li T, Li J, Tang L, Ding C. Prognostic value of baseline total metabolic tumour volume of (18)F-FDG PET/CT imaging in patients with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. EJNMMI Res. 2021;11(1):64. 10.1186/s13550-021-00807-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim TY, Min GJ, Jeon YW, Park SS, Park S, Shin SH, et al. Impact of epstein-barr virus on peripheral T-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified and angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Front Oncol. 2021. 10.3389/fonc.2021.797028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huo YJ, Zhao WL. Circulating tumor DNA in NK/T and peripheral T cell lymphoma. Semin Hematol. 2023;60(3):173–7. 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2023.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim SJ, Kim YJ, Yoon SE, Ryu KJ, Park B, Park D, et al. Circulating tumor DNA-based genotyping and monitoring for predicting disease relapses of patients with peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Cancer Res Treat. 2023;55(1):291–303. 10.4143/crt.2022.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fu L, Zhou X, Zhang X, Li X, Zhang F, Gu H, et al. Circulating tumor DNA in lymphoma: technologies and applications. J Hematol Oncol. 2025;18(1):29. 10.1186/s13045-025-01673-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rodríguez M, Alonso-Alonso R, Tomás-Roca L, Rodríguez-Pinilla SM, Manso-Alonso R, Cereceda L, et al. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma: molecular profiling recognizes subclasses and identifies prognostic markers. Blood Adv. 2021;5(24):5588–98. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021005171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Horwitz SM, Ansell S, Ai WZ, Barnes J, Barta SK, Brammer J, et al. T-cell lymphomas, version 2.2022, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20(3):285–308. 10.6004/jnccn.2022.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chavez JC, Foss FM, William BM, Brammer JE, Smith SM, Prica A, et al. Targeting the inducible T-cell costimulator (ICOS) in patients with relapsed/refractory T-follicular helper phenotype peripheral T-cell and angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2023;29(10):1869–78. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Meeuwes FO, Brink M, van der Poel M, Kersten MJ, Wondergem M, Mutsaers P, et al. Impact of rituximab on treatment outcomes of patients with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; a population-based analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2022. 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schmitz N, Trümper L, Ziepert M, Nickelsen M, Ho AD, Metzner B, et al. Treatment and prognosis of mature T-cell and NK-cell lymphoma: an analysis of patients with T-cell lymphoma treated in studies of the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 2010;116(18):3418–25. 10.1182/blood-2010-02-270785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ellin F, Landström J, Jerkeman M, Relander T. Real-world data on prognostic factors and treatment in peripheral T-cell lymphomas: a study from the Swedish Lymphoma Registry. Blood. 2014;124(10):1570–7. 10.1182/blood-2014-04-573089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chang E, Tan YH, Chan JY. Novel clinical risk stratification and treatment strategies in relapsed/refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2024;17(1): 38. 10.1186/s13045-024-01560-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fossard G, Broussais F, Coelho I, Bailly S, Nicolas-Virelizier E, Toussaint E, et al. Role of up-front autologous stem-cell transplantation in peripheral T-cell lymphoma for patients in response after induction: an analysis of patients from LYSA centers. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(3):715–23. 10.1093/annonc/mdx787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Park SI, Horwitz SM, Foss FM, Pinter-Brown LC, Carson KR, Rosen ST, et al. The role of autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with nodal peripheral T-cell lymphomas in first complete remission: report from COMPLETE, a prospective, multicenter cohort study. Cancer. 2019;125(9):1507–17. 10.1002/cncr.31861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cho H, Yoon DH, Shin DY, Koh Y, Yoon SS, Kim SJ, et al. Current treatment patterns and the role of upfront autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma: a Korean nationwide, multicenter prospective registry study (CISL 1404). Cancer Res Treat. 2023;55(2):684–92. 10.4143/crt.2022.1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brink M, Huisman F, Meeuwes FO, van der Poel M, Kersten MJ, Wondergem M, et al. Treatment strategies and outcome in relapsed peripheral T-cell lymphoma: results from the Netherlands Cancer Registry. Blood Adv. 2024;8(14):3619–28. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2023012531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gao H, Zhang Z, Wang J, Jia Y, Zheng Y, Pei X, et al. Application patterns and outcomes of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in peripheral T-cell lymphoma patients: a multicenter real-world study in China. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2024;13(1):88. 10.1186/s40164-024-00557-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Krug A, Saidane A, Martinello C, Fusil F, Michels A, Buchholz CJ, et al. In vivo CAR T cell therapy against angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2024;43(1): 262. 10.1186/s13046-024-03179-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Olson ML, Mause ERV, Radhakrishnan SV, Brody JD, Rapoport AP, Welm AL, et al. Low-affinity CAR T cells exhibit reduced trogocytosis, preventing rapid antigen loss, and increasing CAR T cell expansion. Leukemia. 2022;36(7):1943–6. 10.1038/s41375-022-01585-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moskowitz AJ, Ghione P, Jacobsen E, Ruan J, Schatz JH, Noor S, et al. A phase 2 biomarker-driven study of ruxolitinib demonstrates effectiveness of JAK/STAT targeting in T-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2021;138(26):2828–37. 10.1182/blood.2021013379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ruan J, Zain J, Palmer B, Jovanovic B, Mi X, Swaroop A, et al. Multicenter phase 2 study of romidepsin plus lenalidomide for previously untreated peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2023;7(19):5771–9. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2023009767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rai S, Kim WS, Ando K, Choi I, Izutsu K, Tsukamoto N, et al. Oral HDAC inhibitor tucidinostat in patients with relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma: phase IIb results. Haematologica. 2023;108(3):811–21. 10.3324/haematol.2022.280996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shi Y, Dong M, Hong X, Zhang W, Feng J, Zhu J, et al. Results from a multicenter, open-label, pivotal phase II study of chidamide in relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(8):1766–71. 10.1093/annonc/mdv237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shi Y, Jia B, Xu W, Li W, Liu T, Liu P, et al. Chidamide in relapsed or refractory peripheral T cell lymphoma: a multicenter real-world study in China. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10(1):69. 10.1186/s13045-017-0439-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li C, HU H, Lei T, Yu H, Chen X, Peng S, et al. Updated results of a prospective study: rituximab and lenalidomide plus chidamide (RLC) for patients with relapsed/refractory angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2023;142:6221. 10.1182/blood-2023-184830. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim WS, Fukuhara N, Yoon DH, Yamamoto K, Uchida T, Negoro E, et al. Darinaparsin in patients with relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma: results of an Asian phase 2 study. Blood Adv. 2023;7(17):4903–12. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2022008615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Witzig T, Sokol L, Kim WS, de la Cruz VF, Martín GA, Advani R, et al. Phase 2 trial of the farnesyltransferase inhibitor tipifarnib for relapsed/refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2024;8(17):4581–92. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2024012806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.