Abstract

We propose a permutation-based explanation method for image classifiers. Current image-model explanations like activation maps are limited to instance-based explanations in the pixel space, making it difficult to understand global model behavior. In contrast, permutation based explanations for tabular data classifiers measure feature importance by comparing model performance on data before and after permuting a feature. We propose an explanation method for image-based models that permutes interpretable concepts across dataset images. Given a dataset of images labeled with specific concepts like captions, we permute a concept across examples in the text space and then generate images via a text-conditioned diffusion model. Feature importance is then reflected by the change in model performance relative to unpermuted data. When applied to a set of concepts, the method generates a ranking of feature importance. We show this approach recovers underlying model feature importance on synthetic and real-world image classification tasks.

Keywords: permutation importance, explainable AI, diffusion models

1. Introduction

Understanding AI model predictions is often important for safe deployment. However, explanation methods for image-based models are instance-based and rely on heatmaps or masks in the pixel space [18,25,28,37], and recent work has called into question their utility [1,2,10]. We hypothesize that these methods fall short in part because they are in the pixel space rather than in the concept space (e.g., presence of an object), leading to an increase in the cognitive load placed on a user. Furthermore, while useful for model debugging, it is often intractable to look at instance-based explanations for every single image in a large test set.

We propose an approach for explaining image-based models that uses permutation importance to produce dataset-level explanations in the concept space. In contrast to instance-based explanations, our method generates a ranking of feature importance by measuring the drop in model performance when one permutes each concept across all instances in the test set. While widely used with tabular data [3,4,29], it is unclear how permutation importance applies to images. For example, given a scene classifier, if we want to know to what extent it relies on a concept like the presence of a chair, one cannot simply shuffle the pixels of chairs across images in the dataset.

In light of these challenges, we present DEPICT, an approach that uses diffusion models to enable permutation importance on image classifiers. Our main insight is that while it is difficult to permute concepts in the pixel space, we can permute concepts in the text space (Fig. 1). For example, we can simply shuffle the presence of a chair in the captions of images. Then, using a text-conditioned diffusion model, we bridge from text (captions) to pixel space (image), allowing us to permute concepts across images. With the generated permuted and unpermuted test set, we can apply permutation importance as usual.

Fig. 1.

Text-conditioned diffusion enables permutation importance for images. Given images captioned with concepts, we permute concepts across captions. Then, we generate images via text-conditioned diffusion models and measure classifier performance relative to unpermuted data. If performance drops, the model relies on the concept.

Given a target model, an image test set captioned with a set of concepts, and a text-conditioned diffusion model, we show that DEPICT can generate concept-based model explanations that would otherwise be intractable via local instance-based explanations. Through experiments on synthetic and real image data, we show that our approach can more accurately capture the feature importance of classifiers over commonly used instance-based explanation approaches.

2. Related Works

We introduce DEPICT, a diffusion-enabled permutation importance approach to understand image-based classifiers. DEPICT lies at the intersection of explainable AI, generative models, and human-computer interaction.

Explainable AI.

Explainable AI allows us to understand model behavior [31]. Global explanations allow us to do so as a whole. E.g., linear models that operate directly on the input space are explainable via their weights, which reflect the importance of each input feature with respect to the model’s output [30]. The usefulness of these explanations depends in part on the interpretability of the input space. If the input space is just pixels, such explanations are unlikely to be useful. More complex models like deep neural networks require extrinsic explanation techniques. For tabular data, the input space corresponds to interpretable concepts, and dataset-specific feature importance can be calculated with permutation importance [4,8,33], which we describe in Sect.3.1. Currently, no global or even dataset-level explanation techniques that rank concepts exist for image-based models. Instead, researchers typically rely on instance-based explanations in the form of activation maps or masks [18,25,28]. Our approach helps us understand dataset-level behavior of image-based models by permuting concepts across images using text-conditioned diffusion models.

Generative AI-Enabled Classifier Explanations.

Recent breakthroughs in generative AI have helped researchers probe black-box models. For example, generative models can produce counterfactual images that subsequently change a classifier’s predictions [7,22], and such changes can be linked to either changes in natural language text, concept annotations, or expert feedback to better understand why a model prediction might change. DEPICT is similar in that it also relies on generative AI techniques to produce images with changed concepts. However, in contrast, DEPICT generates a ranking of concepts based on their effect on downstream model performance, rather than their effect on model predictions.

Concept Bottleneck Models.

Concept bottleneck models (CBMs) are interpretable models trained by learning a set of neurons that align with human-specified concepts. They support interventions on concepts compared to end-to-end models [15,17,19,21,32,34–36]. One can perform permutation on CBMs by permuting concept predictions in the bottleneck layer. DEPICT differs by handling a more common case of models. We cannot assume all models are CBMs: many important networks are black-box, non-CBM models whose parameters we do not have access to (e.g., proprietary/private data or training algorithms).

Image Editing.

Recent advances in text-to-image diffusion models [23,26,27] allow for high-quality text-conditioned image synthesis, enabling easy manipulation of images via text-edits. DEPICT relies on generative models conditioned on natural language text that can be modified to produce an edited version of an image. Prior work on image editing has focused on limited types of edits (e.g., style transfer or inserting objects [14,39]). DEPICT is an application of these techniques and advances in these areas of work would improve DEPICT.

3. Method

Overview.

In our setting, we have a set of test images and a black-box model that maps images in to predictions in . In standard permutation importance, one permutes a single feature across instances while holding the others constant and examines the drop in model performance relative to baseline. This does not yield meaningful explanations when permuting in pixel space. Instead, we assume there is a relevant concept-based text space where permuting concepts is easy (e.g., image captions). Given a text-conditioned diffusion model , we permute concepts in text space , transform captions to image space with , and use the generated images as a proxy for permutations in image space.

Accurately estimating model feature importance via this approach requires three testable assumptions: (1) Permutable concepts: we can permute a set of relevant concepts in ; (2) Effective generation: we can obtain a mapping such that can accurately classify generated instances; (3) Independent Permutation: while changing a concept for a set of instances, the other concepts in the instances do not change. These assumptions require some algorithmic decisions and data considerations that we discuss below and verify in our experiments.

3.1. Permutation Importance on Tabular Data

We begin by recounting how permutation importance is performed in tabular data [4] to aid in describing our approach. For simplicity we focus on binary classification, although permutation importance generalizes to multi-class classification and even regression. We assume: an input space (e.g., for -dimensional numerical tabular data); a classifier that maps from the input space to binary decisions; labeled examples ; and a loss evaluating performance (e.g., error). The reference performance of the classifier on the unpermuted data is given by (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Approach overview.

In tabular permutation importance (left), one obtains feature importance by permuting each feature column and measuring the impact on model performance. In diffusion-enabled image permutation importance (right), features are permuted in the diffusion model’s conditioned text space and generate dataset images for classifier evaluation. To validate results, one can check that the model can accurately classify generated images, and only the permuted concept changed.

In permutation importance, one permutes a single coordinate of the data for while holding the others fixed and measures the change in performance relative to the original model performance . Let be the examples with the th coordinate permuted among the samples. One calculates the performance of on the permuted test set, as . The permutation importance of the th coordinate for is the difference between the original accuracy and the accuracy while permuting , or . Given the inherent randomness, this process is typically repeated many times and the average importance value is used to rank the variables.

Permutation importance is not without limitation. In particular, high degrees of collinearity among input features may lead to incorrect beliefs that a particular feature is not relevant to the outcome or label [20,29]. Thus, its use in generating hypotheses of associations is limited. However, we are primarily interested in what the model is relying on and not the underlying relationships in the data generating process. If there are two highly correlated features and the model is only relying on one, permutation importance will correctly identify which one.

3.2. Permutation Importance on Image Data

We now extend permutation importance to images. We assume: a space of images ; a classifier mapping images to predictions; labeled images ; and a performance metric .

The crux of the method is a parallel concept text space and functions for moving between and . In particular, we assume there is a concept text space like scene image captions with concepts (such as the presence of a chair) that can be permuted like tabular data and turned into text easily. For simplicity, we also assume that we have corresponding concept labels for each input with each , where we can represent , a -dimensional binary vector indicating the presence of each concept. To move between the spaces, we assume a generative model that maps a concept vector to a sample image matching the concepts (Fig. 2); we also assume a concept classifier that can accurately detect whether a concept appears in an image. For instance, might be a diffusion model trained to map from a caption to an image and might be a classifier trained to recognize a set of concepts from an image (e.g., if the image contains a couch).

Given the classifier, diffusion model, and concept classifier, we now set up permutation importance for images. We start with the reference performance on unpermuted generated data, . To test the importance of the th concept, we permute the th entry in the concept space across text instances and map the text to new images, creating a new test set for each permuted concept . We repeat this process times to generate a distribution of observed differences in performance between the original generated test set and the permuted test set, , where . Large performance drops indicate the model relied on the concept, while no drop in performance suggests the concept is unimportant to the model and this particular dataset. We can then rank concepts by their average performance drop.

Importantly, the approach assumes effective generation, meaning that the classifier performs similarly on generated images from conditioned on the original dataset’s captions as it does the real images. To test whether this assumption holds we do two tests. First, we measure the difference between and , where . If the difference is large, then this assumption does not hold. If the difference is small, we look for more granular differences by computing concept classifier performance between the original images and the generated images, i.e., , where is the concept classifier performance in predicting concept . A drop in either target model performance overall or one concept via the concept classifier suggests that the assumption of effective generation does not hold.

Finally, DEPICT assumes independent permutation. If changing one concept also changes other concepts in the image space, we cannot trust the permutation importance results. Thus, after permuting concept , we calculate the concept classifier performance on the generated images before and after permutation. For all non-permuted concepts , we expect concept classifier performance to hold, and for permuted concept , we expect performance to drop.

4. Experiments and Results

To validate DEPICT, we first consider a synthetic setting where generation is easy, followed by two real-world datasets: COCO [16] and MIMIC-CXR [11, 13].

4.1. Synthetic Dataset

In our synthetic dataset, images can contain any combination of six concepts that each consist of a distinct colored geometric shape: {red, green blue} × {circle, rectangle}. Each image is generated according to an indicator variable indicating whether each shape is present. is drawn per-component from a Bernoulli distribution with . We generate the image from by placing shapes randomly, such that no two shapes overlap. We construct a caption for each image by with descriptions of each shape joined by a comma (e.g., a -colored circle at with radius is described as “ circle ”) (full details are in supplementary 8).

Given images, we generate tasks and corresponding labels. Each task is defined by a weight vector over the six indicator variables where each component is drawn uniformly over [0,1]. Given the weight vector, the score of an image with indicator vector is given by . We define a binary classification task by thresholding image scores at the median of the dataset.

Target Models.

We aim to generate concept-based explanations for a target model that predicts . We use a concept bottleneck model [15] for full control: we first predict all concepts , by training a model to predict shape presence as a vector . The target model is defined as a weighted sum of via the weights generated above, . This way, we know the exact model mechanism and consider the weight vector as the true model feature importance.

Diffusion Model.

We fine-tune Stable Diffusion [26] on 50,000 synthetic images, with captions describing the presence and location of each shape separated by commas (full details are in supplementary 8).

Using DEPICT.

To generate concept rankings, we permute each concept in the text space 500 times. For each permutation, we generate a dataset using the diffusion model and pass the images through the target model, measuring the AUROC drop compared to the unpermuted generated dataset. Then, the mean AUROC drop across all 500 permutations is used to rank concepts.

Oracle Model Feature Ranking.

We calculate standardized regression coefficients as the oracle ranking of features by multiplying each model’s weight vector by the standard deviation of the concept predictions on the real images [5,24]. We also compare to an oracle that permutes concept predictions of the real data at the bottleneck of the network in supplementary 8. We note that DEPICT does not assume access to model parameters needed to calculate such oracles.

Baselines.

We compare the ranking produced by DEPICT to a ranking produced by GradCAM [28] and LIME [25], two commonly used explanation methods for image-based classifiers. Since GradCAM and LIME generate instance-based explanations, we extend these approaches to generate a ranking by relying on concept annotations and their corresponding mask. Because we have access to the image generation process of the synthetic dataset, we generate an concept-level mask for all concepts in each image. Then, for each image, we calculate the intersection-over-union (IOU) between each concept-level mask and the GradCAM or LIME mask generated by the classifier (full details are in supplementary 8). Then, we rank concepts by their mean IOU across the entire test set. We note that computing this ranking for GradCAM and LIME requires access to image-level masks as well as the model parameters, while DEPICT does not. Because GradCAM and LIME are generated via the real images, we only generate one importance value for each concept in each image, compared to a distribution of model feature importances generated by DEPICT.

Evaluation and Results.

Evaluation consists of two parts. We quantitatively and qualitatively compare to the oracle and baselines, and we validate our assumptions of effective generation and independent permutation.

Model feature ranking evaluation.

We Plot The Depict, LIME and GradCAM generated model feature importances against the oracle (standardized weight vector ) across all 100 models and measure the Pearson’s correlation [6], with 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals. Methods that correctly rank concepts will have high correlation with the oracle. We also show boxplots of each method’s feature importances for a randomly chosen subset of models and compare to the oracle ranking. Additionally, we consider each method’s permutation importance as a prediction task for which concepts are predicted to be important. We label each concept as “important” or “not important” by binarizing the oracle model feature importances across all weight thresholds , and calculate the AUROC between the generated model feature importance and binarized feature importance. Finally, we calculate the agreement in the top-k features between the ground truth weights and each method. We consider [1,6].

Results.

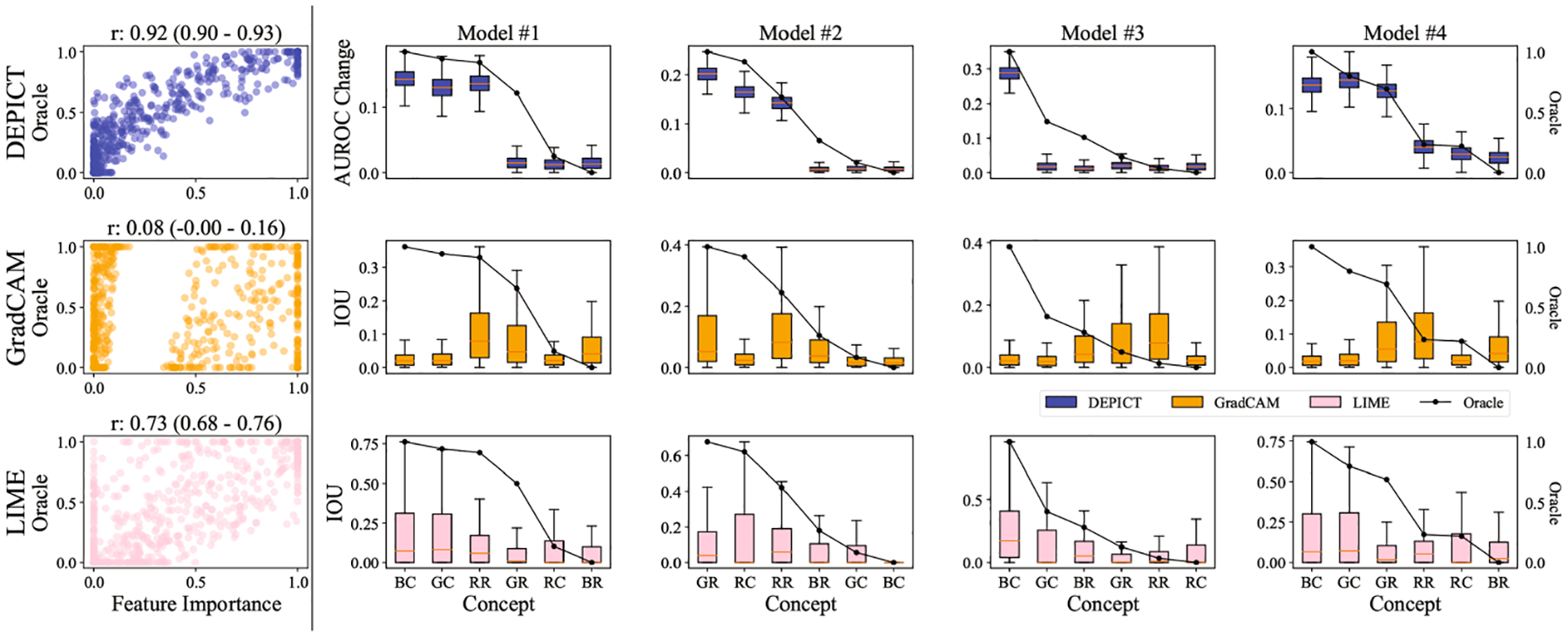

DEPICT has the highest correlation with the oracle feature weights of each model (0.92 [95%CI 0.90–0.93]), followed by LIME (0.73 [95%CI 0.68–0.76]), and GradCAM (0.08 [95%CI 0.00–0.16]) (Fig.3). Looking at individual models, while both DEPICT and LIME produce feature importance rankings which are highly correlated with the oracle, DEPICT better aligns with the magnitude of the ground truth feature importances. Furthermore, DEPICT performs on par or better than both GradCAM and LIME in terms of AUROC and top-k accuracy across all weight thresholds (Fig. 4a). If considering the oracle as permuting concepts at the bottleneck, DEPICT has a significantly higher correlation with the oracle (0.98 [0.97–0.98]) compared to GradCAM (0.07 [−0.01–0.15]) and LIME (0.72 [0.68–0.76]) (supplementary Fig. 11).

Fig. 3. Model feature importance across synthetic data models.

We compare the DEPICT ranking to GradCAM [28] and LIME [25]. Left: DEPICT has higher correlation with the standardized regression weights compared to GradCAM and LIME. Right: ranking generated for 4/100 randomly chosen classifiers. RC: red circle; BC: blue circle; GC: green circle; RR: red rectangle; BR: blue rectangle; GR: green rectangle.

Fig. 4. AUROC and top-k accuracy of methods across varying importance thresholds.

We plot DEPICT’s performance against GradCAM and LIME. Datapoints in the upper left half are DEPICT outperforming GradCAM and LIME, while in the lower half are DEPICT underperforming. Across all three sets of tasks, DEPICT outperforms both GradCAM and LIME in terms of AUROC and top-k accuracy when predicting important concepts across most thresholds.

Validation of assumptions.

To check for effective generation, we measure AUROC between real and generated images on the target and concept classifier. To check for independent permutation, we rely on a concept classifier that predicts the presence of the six shapes that we are permuting (supplementary 8). For each concept that is permuted across images (e.g., red circle), the concept classifier should perform worse in classifying the permuted concept, while still classifying the other concepts well.

Results.

In terms of effective generation, the differences in AUROC between real and generated images for all models was <= 0.12 for both the target models and concept classifiers (supplementary Tables 2, 3). Given that all AUROC values were above 0.88, we consider this effective generation for this task. Furthermore, each time a concept is permuted, the concept classifier is no longer able to classify the specific concept, while still classifying the other concepts well (supplementary Fig. 12). This validates independent permutation for each of the concepts.

4.2. Real Dataset

We evaluate DEPICT’s ability to generate concept-based explanations of image classifiers on COCO [16]. We consider two settings reflecting different levels of difficulty in ranking concepts, showing that DEPICT generates better rankings compared to baselines.

Target Models.

We consider two sets of scene classifiers. For all target models, we learn a concept bottleneck where is 15 concepts that the classifier may rely on (see supplementary 9 for full list). Then, we learn a linear classifier parameterized by to map concepts to a final prediction. We train two sets of target classifiers:

Primary feature models.

We first train binary tasks to classify images as {home or hotel} or {not}. By design, these models each rely heavily on one of 15 concepts in the image: we resampled the training data such that there was a 1:1 correlation between a concept in the image (e.g., person or couch) and the outcome, totalling 15 classifiers (full list in supplementary 9).

Mixed feature models.

We also trained six scene classification tasks, where a model classifies if an image is one of six scenes: (1) shopping and dining, (2) workplace, (3) home or hotel, (4) transportation, (5) cultural, and (6) sports and leisure. We did not resample the training data to encourage the model to rely on specific concepts, but instead used the entire training set to let the model rely on any set of concepts (see supplementary 9 for details).

Diffusion Model.

We fine-tune Stable Diffusion [26] on COCO [16] to generate images for our task (examples in Fig. 5). We use COCO concept annotations as captions. E.g., if an image contains 2 persons and 1 couch, the corresponding caption is “ 2 person, 1 couch.” We generate a scene label for each image using a network trained on the Places 365 dataset [38] (full details in supplementary 9).

Fig. 5. Generated Images.

Examples of generated images where each concept is (upper) or is not (lower) in the caption used to generate the image. The generated images reflect whether or not the concept is included in the caption.

Using DEPICT.

To generate model feature importances with DEPICT, we permute each concept in the text-space 25 times. For each permutation, we generate a dataset with the diffusion model and pass these images through the target model. The AUROC drop compared to the dataset generated with non-permuted text yields a distribution of model feature importance values per concept.

Oracle Model Feature Ranking.

We again calculate standardized regression coefficients using the learned weight vector . We also calculate an additional oracle by permuting concepts at the bottleneck in the supplementary.

Baselines.

We compare DEPICT to GradCAM [28] and LIME [25]. We measure the IOU between the GradCAM and LIME masks using each object annotation mask for each image in COCO (full details are in supplementary 9).

Evaluation and Results.

We quantitatively and qualitatively evaluate DEPICT on COCO just as we did in the synthetic setting, as well as validate the assumptions of effective generation and independent permutation using a concept classifier trained to predict the concepts in COCO (full details in supplementary 9). Furthermore, for quantitative evaluation, we consider k ∈ [1,15], as there are 15 concepts to threshold over in the COCO models.

Primary feature model evaluation.

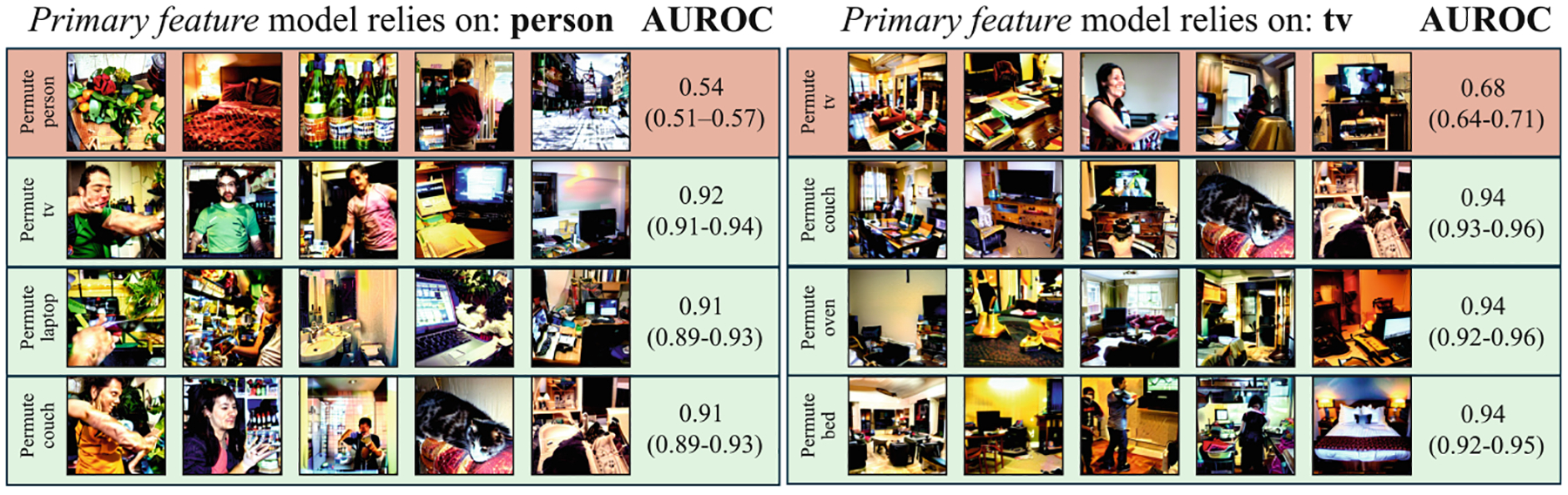

DEPICT has higher correlation with the oracle (0.73 [0.59–0.83]) compared to GradCAM (−0.10 [−0.23–0.03]) and LIME (0.15 [−0.02–0.30]) (Fig. 6). We show rankings for three of 15 randomly chosen classifiers in Fig. 6 as well as model performance on permuted datasets in Fig. 7. DEPICT also outperforms both GradCAM and LIME in terms of AUROC and top-k accuracy across most thresholds (Fig. 4b). If considering the oracle as permuting concepts at the bottleneck, DEPICT has a higher correlation with the oracle (0.90 [0.83–0.95]) compared to GradCAM (−0.05 [−0.17–0.10]) and LIME (0.19 [0.03–0.35]) (supplementary Fig. 13).

Fig. 6. Model feature importance across primary feature models.

We compare the ranking produced by DEPICT, GradCAM [28] and LIME [25] to the oracle generated by permuting concepts at the bottleneck. Left: DEPICT has higher correlation with the oracle compared to LIME and GradCAM. Right: ranking generated for 3 of the 15 classifiers. DEPICT detects the primary concept in all classifiers as well as the low importance of the non-primary concepts, while GradCAM and LIME do not.

Fig. 7. Permutation examples.

We show permutation examples for two primary feature models that rely on either “person” or “tv” when predicting home or hotel. When permuting the most important concept, model performance is low, whereas when permuting concept that the model does not rely on, model performance does not drop.

Mixed feature model evaluation.

DEPICT has higher correlation with the oracle feature importance (0.35 [−0.05–0.66]) compared to GradCAM (0.15 [−0.21–0.50]) and LIME (0.27 [0.01–0.52]) (Fig. 8). For individual scene classifiers, DEPICT generates more reasonable rankings compared to GradCAM and LIME. DEPICT also outperforms both GradCAM and LIME in terms of AUROC and top-k accuracy across most thresholds (Fig. 4c). If considering the oracle as permuting concepts at the bottleneck, DEPICT has a higher correlation with the oracle (0.49 [−0.01–0.79]) compared to GradCAM (0.17 [−0.18–0.50]) and LIME (0.30 [0.04–0.53]) (supplementary Fig. 14).

Fig. 8. Model feature importance across mixed feature models.

We compare the ranking produced by DEPICT, GradCAM [28] and LIME [25] to the oracle generated by permuting concepts at the bottleneck. Left: DEPICT has the highest correlation with the oracle model feature importance. Right: We show the ranking generated by DEPICT, GradCAM and LIME for three of the mixed feature models.

Validation of assumptions.

For the primary feature models, DEPICT achieves both effective generation in target models and concept classifiers (< 0.10 AUROC change between real and generated images) (supplementary Tables 4, 5) and independent permutation (minimal changes in concept classifier performance for non-permuted concepts) (supplementary Fig. 15). For the mixed feature models, DEPICT achieves effective generation for three of the six scene classifiers (supplementary Tables 6, 7) and independent permutation on all classifiers (supplementary Fig. 16).

4.3. DEPICT in Practice: A Case Study in Healthcare

Until now, we have applied DEPICT to datasets in which all concepts that a model might rely on can be permuted. However, depending on the diffusion model and/or our knowledge of important concepts, we may only have the ability to permute on a subset of concepts on which the model relies. Here, we discuss how DEPICT can apply in such scenarios. Rather than generating a ranking of all concepts, we ask the question: does the model rely on a specific concept?

We consider MIMIC-CXR [12,13], a dataset of paired X-rays and radiology reports. We consider the task of classifying pneumonia from the patient’s chest X-ray. We use patient demographics as concepts (Fig. 9): body mass index (BMI) > 30, age > 60, sex = Female, and prepend them to the patient’s radiology report, e.g., “Age: 1, BMI: 0, Sex: 1, Findings:…”, where “Findings:” is the beginning of the report. The presence of the entirety of the radiology report text allows the diffusion model to generate high quality images. Since concept masks are not available, we cannot apply GradCAM and LIME.

Fig. 9. Generated X-rays.

We show generated X-rays with patient age, body mass index (BMI), and sex permuted. While difficult to permute such concepts in pixel space, a diffusion model can map permutations from text (e.g., “age>60”) to pixel space.

Target Models.

We train three target models on MIMIC-CXR to predict the presence of pneumonia on the chest X-ray. By design, these models were trained such that they heavily rely on either the patient’s age, body mass index (BMI) or sex. To achieve this, we resampled the training data such that there was a 1:1 correlation between each concept and the outcome of pneumonia. Furthermore, the target model was a concept bottleneck constrained to 17 concepts: 13 radiological findings on the chest X-rays, along with patient age, BMI, and sex (full details in supplementary 10).

Diffusion Model.

We fine-tune Stable Diffusion [26] on MIMIC-CXR X-rays and radiology reports prepended with concepts (details in supplementary 10).

Using DEPICT.

To generate feature importances, we permute each concept 25 times. While permuting only a few concepts per classifier does not generate a full ranking, a significant model performance drop on the permuted test set reflects that the model relies on the concept in some way. We discuss validation of assumptions when not all concepts can be permuted in the supplementary 10.

Results.

The difference in classification AUROC between real and generated chest X-rays for all three target models as well as concept classifiers on the permutable concepts ranges from 0.0 to 0.04 (supplementary Tables 8, 9), suggesting effective generation. For independent permutation, we observe some changes in concept classifier performance after permutation when classifying concepts such as lung opacity and lung lesion (supplementary Fig. 18). Thus, one must proceed with caution about interpreting the importance of BMI, age, and sex, as they may be confounded by changes to other concepts such as lung opacity or lung lesion.

For all three target models, permuting patient BMI, age, and sex results in a significant drop in model performance (BMI: 0.70 [0.70–0.71] vs. 0.97 [0.96–0.97]; age: 0.59 [0.59–0.59] vs. 0.85 [0.83–0.87]; sex: 0.53 [0.53–0.54] vs. 1.00 [0.99–1.00]) (Table 1). We can conclude that the models rely on these concepts in some way. DEPICT could allow model developers to probe models pre-deployment to potentially catch when models are relying on a concept that they should not be.

Table 1. DEPICT applied to MIMIC-CXR.

We show AUROC and 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals on real and generated images for the models that rely on patient age, BMI, or sex. When permuting the concepts, model performance significantly drops, showing that the models rely on each of the concepts in some way.

| BMI | Age | Sex | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Real Images | 0.98 (0.97 – 0.98) | 0.89 (0.87 – 0.91) | 1.00 (1.00 – 1.00) |

| Generated Images | 0.97 (0.96 – 0.97) | 0.85 (0.83 – 0.87) | 1.00 (0.99 – 1.00) |

| DEPICT | 0.70 (0.70 – 0.71) | 0.59 (0.59 – 0.59) | 0.53 (0.53 – 0.54) |

5. Limitations

DEPICT’s success relies on the diffusion model’s ability to permute concepts effectively and independently. In the experiments involving the synthetic dataset, DEPICT’s ranking was highly correlated with the ranking generated by directly permuting concepts at the bottleneck (supplementary Fig. 11). Subsequently, DEPICT’s ranking was also highly correlated with the ranking of the standardized regression weights (Fig. 3). On the other hand, as DEPICT’s ranking’s correlation with the ranking generated by permuting at the bottleneck decreased (supplementary Fig. 13, 14), so did its correlation with the logistic regression weights (FigS. 6, 8).

Furthermore, when the diffusion model is conditioned on both permutable and non-permutable text (e.g., as in Sect. 4.3), the diffusion model could struggle to permute concepts in the image space if there are mentions of permutable concepts in the non-permutable text space (e.g., if one is trying to permute the patient age, and the radiology report mentions the original age of the patient). While the concept classifier is used to ensure that the concept of interest has been indeed permuted, this still limits the applicability of DEPICT. Moving forward, DEPICT’s success relies on good generative models that can map permuted concepts in the text space to the image space effectively.

6. Conclusion

Understanding the reason behind AI model predictions can aid the safe deployment of AI. To date, image-based model explanations have been limited to instance-based explanations the pixel space [25,28], which are difficult to interpret [1,2,9]. Instead, DEPICT generates image-based explanations at the dataset-level in the concept space. While directly permuting concepts in pixel space is difficult, DEPICT permutes concepts in the text space and then generates new images reflecting the permutations via text-conditioned diffusion. DEPICT relies on a text-conditioned diffusion model that effectively generates images and independently permutes concepts across images. While we have included checks to verify these assumptions, we cannot guarantee that such a diffusion model is available. However, given the rapid progress of the field, we expect that the availability or the ability to train such models will improve, increasing the feasibility of DEPICT.

Supplementary Material

The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-73039-9_3.

Acknowledgements.

We thank Donna Tjandra, Fahad Kamran, Jung Min Lee, Meera Krishnamoorthy, Michael Ito, Mohamed El Banani, Shengpu Tang, Stephanie Shepard, Trenton Chang and Winston Chen for their helpful conversations and feedback. This work was supported by grant R01 HL158626 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).

References

- 1.Adebayo J, Muelly M, Abelson H, Kim B: Post hoc explanations may be ineffective for detecting unknown spurious correlation. In: International Conference on Learning Representations (2021) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adebayo J, Muelly M, Liccardi I, Kim B: Debugging tests for model explanations (2020). arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.05429

- 3.Altmann A, Toloşi L, Sander O, Lengauer T: Permutation importance: a corrected feature importance measure. Bioinformatics 26(10), 1340–1347 (2010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breiman L: Random forests. Mach. Learn 45, 5–32 (2001) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bring J: How to standardize regression coefficients. Am. Stat 48(3), 209–213 (1994) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen I, et al. : Pearson correlation coefficient. Noise Reduction Speech Process. 1–4 (2009) [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeGrave AJ, Cai ZR, Janizek JD, Daneshjou R, Lee SI: Dissection of medical AI reasoning processes via physician and generative-AI collaboration. medRxiv (2023) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher A, Rudin C, Dominici F: All models are wrong, but many are useful: learning a variable’s importance by studying an entire class of prediction models simultaneously. J. Mach. Learn. Res 20(177), 1–81 (2019) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jabbour S, Fouhey D, Kazerooni E, Sjoding MW, Wiens J: Deep learning applied to chest X-rays: exploiting and preventing shortcuts. In: Machine Learning for Healthcare Conference, pp. 750–782. PMLR (2020) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jabbour S, et al. : Measuring the impact of AI in the diagnosis of hospitalized patients: a randomized clinical vignette survey study. JAMA 330(23), 2275–2284 (2023) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson A, Pollard T, Mark R, Berkowitz S, Horng S: MIMIC-CXR database (version 2.0. 0). PhysioNet 10, C2JT1Q (2019) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson A, Bulgarelli L, Pollard T, Horng S, Celi LA, Mark R: Mimic-iv. PhysioNet (2020). Available online at: https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/1.0/(Accessed 23 Aug 2021)

- 13.Johnson AE, et al. : MIMIC-CXR, a de-identified publicly available database of chest radiographs with free-text reports. Sci. Data 6(1), 317 (2019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim G, Kwon T, Ye JC: Diffusionclip: text-guided diffusion models for robust image manipulation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 2426–2435 (2022) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koh PW, et al. : Concept bottleneck models. In: International Conference on Machine Learning, pp. 5338–5348. PMLR (2020) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin TY, et al. : Microsoft coco: common objects in context. In: Computer Vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, September 6–12, 2014, Proceedings, Part V 13. pp. 740–755. Springer; (2014) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Losch M, Fritz M, Schiele B: Interpretability beyond classification output: Semantic bottleneck networks (2019). arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.10882

- 18.Lundberg SM, Lee SI: A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst 30, 4765–4774 (2017) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morales Rodŕıguez D, Pegalajar Cuellar M, Morales DP: On the fusion of soft-decision-trees and concept-based models. Available at SSRN 4402768 (2023)

- 20.Nicodemus KK, Malley JD: Predictor correlation impacts machine learning algorithms: implications for genomic studies. Bioinformatics 25(15), 1884–1890 (2009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oikarinen T, Das S, Nguyen LM, Weng TW: Label-free concept bottleneck models (2023). arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.06129

- 22.Prabhu V, Yenamandra S, Chattopadhyay P, Hoffman J: Lance: Stress-testing visual models by generating language-guided counterfactual images (2023). arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.19164

- 23.Ramesh A, Dhariwal P, Nichol A, Chu C, Chen M: Hierarchical text-conditional image generation with clip latents. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.06125 1(2), 3 (2022) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rao CR, Miller JP, Rao D: Essential Statistical Methods for Medical Statistics. North Holland Amsterdam, The Netherlands: (2011) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ribeiro MT, Singh S, Guestrin C: ”why should i trust you?” explaining the predictions of any classifier. In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, pp. 1135–1144 (2016) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rombach R, Blattmann A, Lorenz D, Esser P, Ommer B: High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 10684–10695 (2022) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saharia C, et al. : Photorealistic text-to-image diffusion models with deep language understanding. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst 35, 36479–36494 (2022) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Selvaraju RR, Cogswell M, Das A, Vedantam R, Parikh D, Batra D: Gradcam: visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, pp. 618–626 (2017) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strobl C, Boulesteix AL, Kneib T, Augustin T, Zeileis A: Conditional variable importance for random forests. BMC Bioinf. 9, 1–11 (2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tibshirani R: Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat Methodol 58(1), 267–288 (1996) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tjoa E, Guan C: A survey on explainable artificial intelligence (xai): toward medical xai. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst 32(11), 4793–4813 (2020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang B, Li L, Nakashima Y, Nagahara H: Learning bottleneck concepts in image classification. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 10962–10971 (2023) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wei P, Lu Z, Song J: Variable importance analysis: a comprehensive review. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf 142, 399–432 (2015) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong LJ, McPherson S: Explainable neural network-based modulation classification via concept bottleneck models. In: 2021 IEEE 11th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC), pp. 0191–0196. IEEE; (2021) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Y, Panagopoulou A, Zhou S, Jin D, Callison-Burch C, Yatskar M: Language in a bottle: language model guided concept bottlenecks for interpretable image classification. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 19187–19197 (2023) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuksekgonul M, Wang M, Zou J: Post-hoc concept bottleneck models (2022). arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.15480

- 37.Zhou B, Khosla A, Lapedriza A, Oliva A, Torralba A: Learning deep features for discriminative localization. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 2921–2929 (2016) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou B, Lapedriza A, Khosla A, Oliva A, Torralba A: Places: A 10 million image database for scene recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell 40(6), 1452–1464 (2017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu JY, Park T, Isola P, Efros AA: Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, pp. 2223–2232 (2017) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.