Abstract

Background

Hypertension is the leading cause of preventable deaths globally. However, reports on its prevalence and risk factors in rural sub-Saharan Africa have been inconsistent, making targeted interventions challenging. This study examines the prevalence, awareness, and associated factors of hypertension among adults in a rural community in southwestern Uganda.

Methods

We conducted a baseline survey in Ngango, Mbarara district, enrolling adults aged 18–79 years from eleven villages. Research assistants and community health workers recruited participants from their homes using the WHO STEPS questionnaire, collecting data on demographics, lifestyle behaviors (tobacco and alcohol use, diet, and physical activity), and other risk factors. Blood pressure (BP) was measured three times, with hypertension defined as BP ≥140/90 mmHg or self-reported antihypertensive use. Logistic regression was applied to identify factors associated with hypertension.

Results

A total of 953 adults were enrolled, with a median age of 43 years (IQR: 30–57). Women accounted for 61.5%, and only 43.5% recalled ever having their blood pressure measured. Hypertension prevalence was 27.3%, with 61.5% of cases undiagnosed. Among those receiving treatment (27.7%), 65.3% had controlled blood pressure. Despite 66.8% of participants reporting regular physical activity, 63.7% were overweight. The key factors associated with hypertension included age over 40 years (OR: 2.26), consuming fewer than three servings of fruits or vegetables per week (OR: 1.62), and being overweight (OR: 1.57) or obese (OR: 2.73).

Conclusion

Hypertension is highly prevalent in rural southwestern Uganda, underscoring the need for targeted interventions—especially within a relatively young and physically active population.

Keywords: blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, rural Uganda, Sub-Saharan Africa

Plain language Summary

Hypertension (high blood pressure) is a leading cause of preventable deaths worldwide. However, data on its impact and risk factors in rural sub-Saharan Africa remain inconsistent, making targeted interventions challenging. This study examines the prevalence, awareness, and associated factors of hypertension in a rural community in southwestern Uganda. We conducted a community-based survey across all eleven villages of Ngango Parish, Mbarara District, enrolling adults aged 18–79 years. Research assistants and community health workers collected demographic data (age, sex), behavioral factors (smoking and alcohol consumption), and lifestyle characteristics (diet and physical activity) through household visits. Blood pressure was measured three times while participants were seated comfortably. Hypertension was defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg or self-reported use of antihypertensive medication. We performed statistical analysis to identify factors associated with hypertension.

Results: We enrolled 953 participants with a median age of 43 years. Women constituted the majority (61.5%). Hypertension was present in 27.3% of individuals, yet awareness was low—only 38.5% knew they had the condition, and just 27.7% were receiving treatment. Despite 66.8% of participants reporting good physical activity, more than half (63.7%) were overweight (BMI > 25 kg/m²).

Key factors associated with hypertension included age over 40 years, consuming fewer than three servings of fruits or vegetables per week, and being overweight or obese.

We conclude that hypertension is common in rural southwestern Uganda, affecting even younger and physically active individuals. This highlights the urgent need for targeted health interventions to address hypertension in these communities.

Key Points

More than 1 in 4 adults in rural Uganda have hypertension, despite high levels of physical activity (67%)

Hypertension awareness and control rates remain below the global targets

Our data show that interventions targeting modifiable risk factors are urgently needed to reduce the rural hypertension burden.

Introduction

Hypertension is the leading cause of preventable death worldwide.1 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), hypertension prevalence is highest in sub-Saharan Africa, with average blood pressure levels in the region exceeding the global average.2 An estimated 10.8 million deaths annually are linked to high blood pressure, with 88% occurring in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).3 However, in rural sub-Saharan Africa, many individuals with hypertension remain undiagnosed and untreated, while those who receive a diagnosis often struggle with inadequate blood pressure control.4,5

In Uganda, hypertension prevalence varies significantly across geographic regions, with rural areas experiencing a growing burden.6 However, most hypertension studies in the country have focused on urban populations,7,8 or hospital-based settings,9,10 leaving gaps in understanding the condition within rural communities.

Population-based studies in rural areas are essential to better understand hypertension trends. To address the knowledge gap in the epidemiology of hypertension in rural Uganda, we conducted a cross-sectional study to assess its prevalence, awareness, and associated factors among adults in a rural community in southwestern Uganda.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This cross-sectional survey is part of the ongoing Comprehensive Hypertension Improvement in Rural Uganda (CHIRU) study, a mixed-methods implementation science cohort. The CHIRU study aims to enhance hypertension management in Ngango Parish, Kagongi Subcounty, Western Uganda, by integrating community health workers (CHWs)—locally known as village health teams (VHTs). Ngango Parish, an administrative unit comprising multiple villages, was the focus of this study. We enrolled adult residents from eleven villages between September 25, 2023, and November 30, 2023.

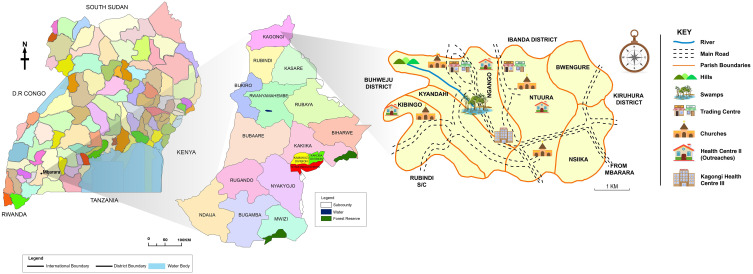

Ngango Parish is one of six parishes in Kagongi Subcounty, Mbarara District (Figure 1), located approximately 270 km southwest of Kampala, Uganda’s capital. This parish was purposively selected for the study as it hosts the only public health facility whose health workers participated in the original cohort study. The local community primarily consists of subsistence farmers.

Figure 1.

Map of Mbarara district showing Kagongi subcounty and Ngango parish.

Community Engagement and Study Population

Ngango Parish comprises 11 villages, each supported by two community health workers (CHWs). These CHWs were introduced to the research team by their coordinator at the local health center. These CHWs are community members trained by the government and serve as a crucial bridge between the community and healthcare facilities. Their role extends beyond linkage—they provide health education, first aid, and manage common illnesses such as diarrhea, malaria, and pneumonia in children,11,12 and HIV in adults.13

Before the study began, CHWs shared population records with the research team, revealing that Ngango Parish has 4355 residents, including 2133 adults (49% of the total population)—991 males and 1142 females.

The study targeted adults aged 18–79 years who had lived in Ngango Parish for at least six months and provided informed consent. Prior to data collection, the research team—including the principal investigator (PI) and research assistants—held meetings with local council leaders and CHWs to introduce the study and coordinate visits to each village. To minimize disruptions to the community’s daily routines, data collection was scheduled for afternoons, Monday through Saturday, aligning with farming and church activities.

To encourage participation, local council leaders and CHWs used megaphones and local radio broadcasts to spread awareness. Announcements were also made at communal gatherings, including places of worship, to inform residents about the study. The research team conducted house-to-house visits across all 11 villages, including trading centers and shops, recruiting all eligible adults found at home.

Study Procedures

Training and Data Collection

Community health workers (CHWs) completed a one-week training on hypertension management using the CDC’s hypertension management curriculum.14 Research assistants underwent three days of training, focusing on study procedures and administration of the STEPS tool. During data collection, each trained research assistant was paired with a CHW to facilitate the process, ensuring that data was gathered from participants in their homes.

Study Measurements

Data were collected using the WHO STEPS tool for noncommunicable disease (NCD) surveillance during household visits.15 This stepwise approach to chronic disease risk factor surveillance employed an interviewer-administered questionnaire structured into three distinct steps:

Step 1

We collected data on demographic, socioeconomic, and behavioral characteristics, including lifestyle factors such as tobacco use, alcohol consumption, salt intake, fruit and vegetable consumption, and physical activity.

Current alcohol users were defined as participants who had consumed alcohol in the past 30 days. Salt intake was assessed by asking participants how often they added salt to their food before tasting or during meals. It was categorized as: 1) “Too much” if salt was always added at the table, 2) “Enough” if salt was rarely added, and 3) “Little” if salt was never added at the table Physical activity was evaluated based on daily work, usual modes of transportation, and time spent sitting each day. Each participant was asked whether they had ever had their blood pressure measured, and awareness was assessed by determining whether they knew they had high blood pressure.

Step 2

Physical measurements included weight, height, waist and hip circumferences, and blood pressure. Blood pressure was measured on the left arm while participants were seated with legs uncrossed and back supported, following at least five minutes of rest. An appropriately sized cuff (22–42 cm) was used with a battery-powered digital blood pressure monitor (Omron 3 Series, Omron, Kyoto, Japan). The device automatically recorded three BP measurements, taken two minutes apart, and the average of the last two readings was documented.

Height was measured manually with participants standing upright against a wall. A tape measure was used to determine height, recorded to the nearest centimeter. Participants stood barefoot, with their back and head against the wall, heels together, and fully stretched.

Weight was measured using a pre-calibrated digital scale (SECA 877), with participants wearing light clothing and no footwear. Measurements were recorded to the nearest tenth of a kilogram.

Step 3

Blood sugar levels were measured using On Call® Plus glucometers (ACON USA), calibrated each morning before data collection. Participants with a random blood sugar (RBS) reading >11.1 mmol/L were scheduled for a follow-up test the next morning after an overnight fast.

Data collection and management were conducted using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap, Vanderbilt University), a cloud-based, secure, HIPAA-compliant system.16

Covariates

Descriptive analyses included baseline demographics such as age, sex, education level, marital status, and occupation. Additionally, comorbidities—such as diabetes mellitus (DM)—were assessed, alongside body mass index (BMI), dietary salt intake, and fruit and vegetable consumption. Lifestyle factors and social habits, including physical activity, smoking, and alcohol consumption, were also examined.

Study Outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was the prevalence of hypertension among adults in the rural community. Hypertension was defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg, based on the 2020 International Society of Hypertension (ISH) Global Hypertension Practice Guidelines,17 or the use of antihypertensive medication. Using the same guidelines, blood pressure readings were categorized as follows: 1) Normal blood pressure: SBP<130 mmHg and DBP <85 mmHg, 2) High normal blood pressure (prehypertension): SBP 130–139 mmHg and/or DBP 85–89 mmHg, 3) Grade 1 hypertension: SBP 140–159 mmHg and/or DBP 90–99 mmHg and 4) Grade 2 hypertension: SBP ≥160 mmHg and/or DBP ≥100 mmHg. All classifications were based on the average of the last two readings from the three blood pressure measurements taken for each participant.

Secondary outcomes included hypertension awareness, the proportion of participants with controlled hypertension, and the identification of factors associated with hypertension. Hypertension awareness was defined as the percentage of participants knew they had high blood pressure among those diagnosed with hypertension in the study. Controlled hypertension was defined as BP <140/90 mmHg among individuals taking antihypertensive medications. Diabetes mellitus (DM) was defined as a fasting blood sugar >7.0 mmol/L and/or self-reported use of antidiabetic medications. High BMI was defined as a BMI ≥ 25 kilograms/meters.2

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data: means and standard deviations for normally distributed continuous variables and medians with interquartile ranges for skewed continuous variables. Categorical variables are reported as counts and percentages. Baseline characteristics were compared between participants with and without hypertension using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and the chi-square (χ²) test for categorical variables. Hypertension prevalence was calculated as the percentage of participants with a blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg or those taking prescribed antihypertensive medications.

To identify factors associated with hypertension, variables were selected based on domain knowledge, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), physical activity, education level, occupation, comorbidities (eg, diabetes mellitus), salt and fruit intake, smoking, and alcohol use. Binary logistic regression was conducted at both univariate and multivariate levels. Variables with p < 0.23 in the univariate analysis, along with biologically plausible factors—diabetes mellitus, physical inactivity, and diet (fruit/vegetable and salt consumption)—were included in the multivariable analysis. Results are presented as crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p values. Factors with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. We used the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) cross-sectional study checklist when writing our report.18

Results

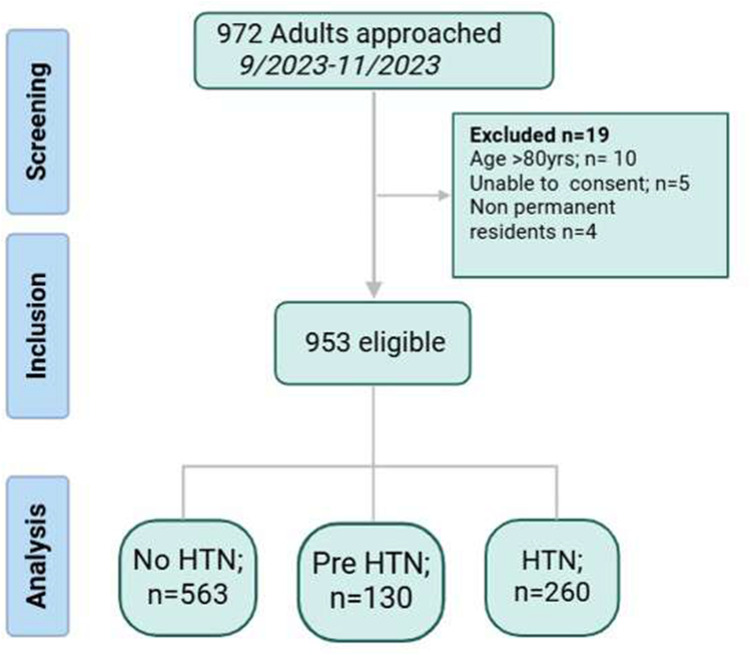

Between September and November 2023, we screened 972 adults in Ngango Parish for eligibility and included 953 participants for this study, as shown below (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Study flow diagram.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Participants

Among the 953 participants, 586 (61.5%) were female, and the median (IQR) age was 43 (30--57) years. Six out of every 10 individuals were overweight (BMI >24.9 kg/m2), although 66.8% reported being physically active. Fewer than half of the participants (415/953; 43.5%) recalled having ever had their BP measured. The median (IQR) random blood sugar level of the participants was 5.7 (4.9--6.7) mmol/L, with only 30 (3.1%) participants having diabetes mellitus. Other baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The participants were evenly distributed among all the participating villages (Figure S1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Participants

| Total N=953 |

No HTN N=693 |

HTN N=260 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex n (%) | ||||

| Male | 367 (38.5) | 270 (39.0) | 97 (37.3) | 0.64 |

| Female | 586 (61.5) | 423 (61.0) | 163 (62.7) | |

| Age median (IQR) | 43 (30–57) | 39 (28–54) | 52 (35–65) | <0.001 |

| Marital status N= 921 n (%) | ||||

| Single | 136 (14.8%) | 109 (16.3) | 27 (10.6) | 0.026 |

| Married | 655 (71.1%) | 474 (71.1) | 181 (71.3) | |

| Separated/Widowed | 130 (14.1%) | 84 (12.6) | 46 (18.1) | |

| Own a mobile phone n (%) | ||||

| No | 444 (46.6) | 325 (46.9) | 119 (45.8) | 0.76 |

| Yes | 509 (53.4) | 368 (53.1) | 141 (54.2) | |

| Monthly income, median (IQR), USD | 39.5 (15.8–79.0) | 39.5 (18.4–65.8) | 39.5 (15.8–79.0) | 0.26 |

| Education level N=946 n (%) | ||||

| No Formal Education | 158 (16.7) | 98 (14.2) | 60 (23.3) | <0.001 |

| Primary | 555 (58.7) | 404 (58.6) | 151 (58.8) | |

| Secondary and Above | 233 (24.6) | 187 (27.1) | 46 (17.9) | |

| BMI median (IQR) kg/m2 | 26.7 (23.7–30.3) | 26.3 (23.4–29.7) | 27.8 (24.5–31.6) | <0.001 |

| BMI category* n (%) | ||||

| Underweight | 28 (2.9) | 21 (3.0) | 7 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| Normal | 318 (33.4) | 249 (35.9) | 69 (26.5) | |

| Overweight | 348 (36.5) | 260 (37.5) | 88 (33.8) | |

| Obesity | 259 (27.2) | 163 (23.5) | 96 (36.9) | |

| RBS median (IQR) mmol/l | 5.7 (4.9–6.7) | 5.7 (4.9–6.7) | 5.7 (4.8–6.8) | 0.67 |

| Diabetes Mellitus n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 30 (3.1) | 16 (2.3) | 14 (5.4%) | 0.015 |

| No | 923 (96.9) | 677 (97.7) | 246 (94.6%) | |

| Ever had a BP measured n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 415 (43.5) | 265 (38.2) | 150 (57.7) | <0.001 |

| No | 538 (56.5) | 428 (61.8) | 110 (42.3) | |

| Reported salt intake, N=898, n (%) | ||||

| Too much | 90 (10.0) | 65 (9.9) | 25 (10.3) | 0.10 |

| Enough | 498 (55.5) | 379 (57.8) | 119 (49.2) | |

| Little | 310 (34.5) | 212 (32.3) | 98 (40.5) | |

| Daily Fruit and Vegetable Servings, N=933, n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 142 (15.2) | 98 (14.4) | 44 (17.3) | 0.24 |

| 2 | 527 (56.5) | 378 (55.7) | 149 (58.7) | |

| 3 | 125 (13.4) | 99 (14.6) | 26 (10.2) | |

| >4 | 139 (14.9) | 104 (15.3) | 35 (13.8) | |

| Physical activity n (%) | ||||

| No | 316 (33.2) | 231 (33.3) | 85 (32.7) | 0.85 |

| Yes | 637 (66.8) | 462 (66.7) | 175 (67.3) | |

| Current Alcohol Use n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 171 (17.9) | 121 (17.5) | 50 (19.2) | 0.53 |

| No | 782 (82.1%) | 572 (82.5%) | 210 (80.8%) | |

| Current smoker n (%) | ||||

| No | 863 (90.6%) | 633 (91.3%) | 230 (88.5%) | 0.18 |

| Yes | 90 (9.4%) | 60 (8.7%) | 30 (11.5%) |

Notes: *BMI categories: underweight <18.5 kg/m2, normal 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, overweight 25–29.9 kg/m2 and obesity >30 kg/m2.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range.

Prevalence and Distribution of Hypertension and Prehypertension Among Study Participants

The overall prevalence of hypertension in this rural community population was 27.3% (260/953), whereas 13.6% (130/953) had pre-hypertension. The prevalence of hypertension was similar among males and females (26.4% vs 27.8%, p value 0.64). Most of the participants had stage 1 hypertension (47%), followed by prehypertension (38%) and grade 2 hypertension (15%) (Figure S2).

Awareness and Control of Hypertension

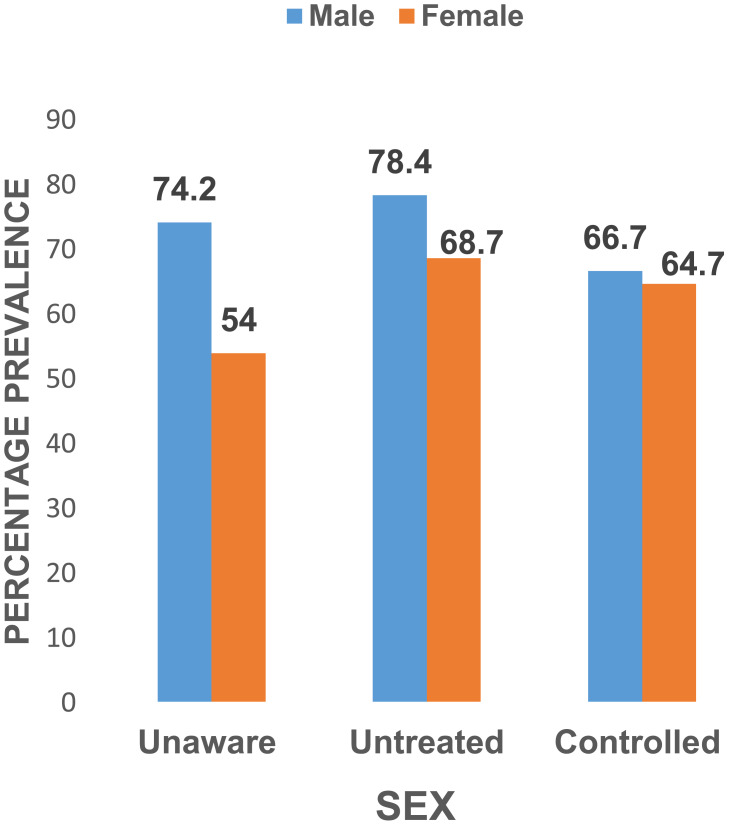

Among the 260 participants with hypertension, 160 (61.5%) were unaware that they had hypertension, 72 (27.7%) were on treatment and 47/72 (65.3%) had their blood pressure controlled. Females were more likely to be aware of and on treatment for hypertension, although males had better BP control among those receiving treatment. (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

A bar graph showing the proportion of participants aware of their hypertension status, those not on medication, and those with controlled hypertension by sex.

Factors Associated with Hypertension Among Adults in Ngango Parish

Compared with younger participants, those aged 40 years and above had greater odds of having hypertension (OR 2.26, 95% CI 1.53--3.33, p <0.001). Consuming fewer than 3 fruit or vegetable servings per week (OR 1.62 95% CI 1.11--2.35, p 0.012), and a higher BMI (overweight (OR 1.57; 95% CI 1.05--2.34, p 0.028) and obesity (OR 2.73; 95% CI 1.80--4.15, p <0.001)) were also associated with hypertension. There was no significant association between hypertension and diabetes mellitus, alcohol intake, smoking, salt/fruit/vegetable consumption or physical activity (Table 2 and Figure S3).

Table 2.

Factors Associated with Hypertension Among Adults in Ngango Parish

| Characteristic | Univariable | Multivariable | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COR (95% CI) | P value | AOR (95%) | P value | |

| Age > 40 | 2.391 (1.766–3.235) | <0.001 | 2.259 (1.534–3.326) | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 0.932 (0.695–1.251) | 0.64 | 1.012 (0.702 1.459) | 0.948 |

| Education | ||||

| No formal education | 2.489 (1.579–3.924) | <0.001 | 1.655 (0.891–3.075) | 0.111 |

| Primary education | 1.519 (1.047–2.206) | 0.028 | 1.126 (0.675–1.878) | 0.650 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | 1.542 (0.978–2.429) | 0.062 | 0.686 (0.354–1.328) | 0.264 |

| Separated/Widowed | 2.211 (1.270–3.847) | 0.005 | 0.686 (0.314–1.496) | 0.343 |

| Occupation | ||||

| Business | 1.550 (0.728–3.302) | 0.256 | 1.416 (0.606–3.312) | 0.422 |

| Farmer | 1.515 (0.804–2.856) | 0.198 | 1.174 (0.526–2.622) | 0.695 |

| Student | 0.580 (0.240–1.397) | 0.224 | 0.660 (0.232–1.874) | 0.435 |

| Retired | 3.077 (0.722–13.110) | 0.129 | 3.507 (0.701–17.556 | 0.127 |

| Owns a phone | ||||

| Yes | 1.046 (0.786–1.393) | 0.756 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.408 (1.158–5.007) | 0.019 | 1.726 (0.777–3.837) | 0.180 |

| BMI category | ||||

| Underweight | 1.203 (0.491–2.947) | 0.686 | 0.914 (0.329–2.543) | 0.864 |

| Overweight | 1.22 (0.852–1.751) | 0.276 | 1.5706 (1.051–2.344) | 0.028 |

| Obesity | 2.125 (1.472–3.068) | <0.001 | 2.735 (1.801–4.154) | <0.001 |

| Physical Activity | ||||

| Yes | 1.029 (0.760–1.394) | 0.851 | 0.898 (0.629–1.282) | 0.554 |

| Less than 3 fruit and Veg servings weekly | 1.349 (0.969–1.880) | 0.079 | 1.618(1.113–2.353) | 0.012 |

| Salt Intake | ||||

| Too much | 1.208 (0.767–1.903) | 0.414 | 1.140 (0.779–2.304) | 0.291 |

| Little | 1.187 (0.890–1.584) | 0.243 | 1.547 (1.092–2.190) | 0.014 |

| Current alcohol use | 1.126 (0.781–1.622) | 0.526 | 0.967(0.600–1.463) | 0.775 |

| Current smoker | 1.376 (0.866–2.187) | 0.177 | 1.285 (0.736–2.243) | 0.378 |

Notes: Bolded factors are those that were statistically significant.

Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; COR, crude odds ratio.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study of individuals living in rural Uganda revealed a high prevalence of hypertension, low awareness rates, and moderate hypertension control among those receiving treatment. Older age and higher BMI were identified as key risk factors. While hypertension epidemiology has been extensively studied in urban populations in Uganda, data from rural communities remain limited, making this study an important contribution to the field.

Although the prevalence of hypertension in our rural population was lower than the Ugandan national average (31.5%),6 it remains one of the highest reported in rural western Uganda, contributing to the literature on geographic variations in hypertension prevalence. One possible reason for these differences is variations in blood pressure measurement protocols across studies, which can complicate direct comparisons.

Another concerning reason for the higher prevalence observed in our study may be its increasing trend over time. For example, a 2013 study from rural western Uganda reported a hypertension prevalence of 14.6%, whereas our findings indicate 27%, nearly double, just a decade later.19

Nationwide surveys have also shown a steady rise in hypertension prevalence. In 2015, the national prevalence was 26.6%, increasing to 31.5% by 2018. Similarly, in western Uganda, the prevalence increased from 26.3% to 36.1% over the same period.6,20

Another survey reported that western Uganda had the highest hypertension incidence rate at 19%.21 This rising trend among rural populations has also been observed in other sub-Saharan African studies.22–24 These findings underscore the urgent need for longitudinal studies that include diverse communities, providing a more comprehensive understanding of hypertension burden in Uganda.

Consistent with current understanding of hypertension pathophysiology,25,26 we found that older age, low fruit/vegetable consumption, and high BMI were significantly associated with hypertension in our study. However, the high prevalence of overweight and obesity among these rural dwellers was unexpected.

Consistent with current understanding of hypertension pathophysiology, we found that older age, low fruit/vegetable consumption, and high BMI were significantly associated with hypertension in our study. However, the high prevalence of overweight and obesity among these rural dwellers was unexpected. Traditionally, individuals living in rural Africa are considered physically active due to their daily farming work and have not adopted a Westernized lifestyle to a significant extent.19,23,27–29 Our findings raise important questions about dietary and lifestyle transitions in these communities.

We postulate that despite self-reported high levels of physical activity, the high prevalence of overweight and obesity among rural dwellers maybe to be driven by dietary patterns rather than a sedentary lifestyle. Rural Ugandan diets are often monotonous, high in glycemic-index staple foods, and rich in sugary items, all of which are linked to elevated BMI levels.30 In fact, inadequate fruit and vegetable consumption was prevalent among participants, with 72% reporting ≤2 servings per day, well below the recommended 5 servings, which have been shown to reduce all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease-related deaths.31 Given the rising rates of overweight and obesity among rural dwellers, there is an urgent need for innovative strategies to address this key hypertension risk factor.

The low rates of hypertension awareness observed in this study are concerning but, unfortunately, consistent with findings from other African studies.32,33 This underscores the urgent need for ongoing strategies to address the burden of hypertension.

Notably, only two out of every five individuals had ever had their blood pressure measured, highlighting the significant gaps in screening, treatment, and control within these settings. Despite low awareness levels, those receiving treatment exhibited fairly good hypertension control, a trend also observed in previous studies.24 This finding presents a key opportunity to improve outcomes by increasing hypertension awareness and ensuring more individuals receive appropriate treatment. Leveraging the existing framework of community health workers, we efficiently screened adults from nearly 600 households in just a few months, demonstrating that this approach can be an effective strategy for raising awareness in rural communities.

Although studies have shown an inverse relationship between education level and hypertension, this was not statistically significant in our population. However, there was a trend suggesting that individuals without formal education had higher odds of hypertension compared to those with formal education. Clinicians may need to consider this when providing care in similar settings.

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of several study limitations. First, this was a cross-sectional study, with blood pressure measured in a single encounter, which may have led to an overestimation of hypertension prevalence. We were unable to confirm elevated BP on multiple occasions, nor could we rule out white coat hypertension. Second, while we assessed associations between behavioral risk factors and hypertension, potential social desirability bias may have influenced self-reported alcohol use, smoking, fruit and vegetable consumption, salt intake, and physical activity. Additionally, we did not examine other common foods and dietary patterns in this population. Finally, while we moved from home to home our data collection involved convenience sampling, as we enrolled only those individuals available at home during household visits. However, we used a validated WHO data collection instrument, ensuring confidence in our measurements. Moreover, conducting BP measurements at home, rather than in a clinical setting, likely minimized the risk of white coat hypertension, as participants were more relaxed in familiar environments.

Despite its limitations, this study was innovative in its approach, utilizing home-to-home visits conducted in the afternoons, a time when most individuals had returned from their fields. By including all adults found at home, we obtained a strong representation of the community.

The finding that less than half of adults had ever had their blood pressure measured underscores the urgent need for more accessible BP monitoring. One potential solution is community-placed BP machines overseen by Village Health Teams (VHTs), which could complement existing BP measurement practices, currently limited to health facility visits or occasional health camps.

Conclusion

We report a high prevalence of hypertension and low disease awareness among relatively young, physically active individuals in rural Uganda. Despite the low awareness levels, hypertension control among those receiving treatment was fair.

Our findings highlight the urgent need for interventions to improve hypertension awareness at the community level, including scaling up screening programs and delivering targeted health education to rural populations.

Future research should focus on identifying unique risk factors for hypertension, such as dietary patterns, common foods, and obesity, in this young and physically active population. Additionally, implementing targeted interventions, such as engaging community health workers to measure blood pressure and refer hypertensive individuals to health facilities, could help generate local, evidence-based solutions for improving hypertension management.

Acknowledgment

We are profoundly grateful to Prof. Ivers Louise for her guidance and mentorship throughout the manuscript preparation. We are also thankful to the research assistants and village health team members for their diligent efforts and dedication. We extend our sincere appreciation to all the study participants from the villages of Ngango Parish, Kagongi Subcounty, whose participation and cooperation were crucial to the success of this research. Finally, we acknowledge support from the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number D43 TW010543. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This paper has been uploaded to medRxiv as a preprint: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.09.03.24313036v1.full.pdf.

Funding Statement

Funding for this work came from the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Global Health’s project entitled “First Mile: Powering the Academic Medical Center to Delivery Healthcare in the Community in Uganda”, which was supported by the Hansjoerg Wyss Medical Foundation.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethical Considerations/Approval

The protocol received ethical approval from the Mbarara University of Science and Technology Research and Ethics Committee (MUST-2023-382) and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (HS3770ES). All study participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 2013.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

Dr. Grace Kansiime is a Fogarty Global Health Fellow supported by the Fogarty International Centre (NIH Grant number D43TW010543) and reports personal fees from AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, grants from NIH, non-financial support from Phillips Pharm Ltd (Microlabs) outside the submitted work. Edwin Nuwagira is supported by the Fogarty International Institute (Grant number K43TW012781). The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Zhou B, Carrillo-Larco RM, Danaei G, et al. Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet. 2021;398(10304):957–980. PMID: 34450083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. A Global Report on Hypertension: The Race Against a Silent Killer; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou B, Perel P, Mensah GA, Ezzati M. Global epidemiology, health burden and effective interventions for elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18(11):785–802. PMID: 34050340. doi: 10.1038/s41569-021-00559-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogah OS, Rayner BL. Recent advances in hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa. Heart. 2013;99(19):1390–1397. PMID: 23708775. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-303227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferdinand KC. Uncontrolled hypertension in sub‐Saharan Africa: now is the time to address a looming crisis. J Clin Hypertension. 2020;22(11):2111. PMID: 32951284. doi: 10.1111/jch.14046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lunyera J, Kirenga B, Stanifer JW, et al. Geographic differences in the prevalence of hypertension in Uganda: results of a national epidemiological study. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0201001. PMID: 30067823. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batte A, Gyagenda JO, Otwombe K, et al. Prevalence and predictors of hypertension among adults in Mbarara City, Western Uganda. Chronic Illness. 2023;19(1):132–145. PMID: 34786975. doi: 10.1177/17423953211058408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Twinamasiko B, Lukenge E, Nabawanga S, et al. Sedentary lifestyle and hypertension in a periurban area of Mbarara, Southwestern Uganda: a population based cross sectional survey. Int J Hypertension. 2018;2018:1–8. PMID: 29854432. doi: 10.1155/2018/8253948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saasita PK, Senoga S, Muhongya K, Agaba DC, Migisha R. High prevalence of uncontrolled hypertension among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a hospital-based cross-sectional study in southwestern Uganda. Pan African Med J. 2021;39(1). PMID: 34527158. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2021.39.142.28620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herbst AG, Olds P, Nuwagaba G, Okello S, Haberer J. Patient experiences and perspectives on hypertension at a major referral hospital in rural southwestern Uganda: a qualitative analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1):e040650. PMID: 33408202. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rukundo GB, Kwesiga B, Ario AR. Improving malaria reporting by village health teams under integrated community case management: a policy brief; 2016.

- 12.Musoke D, Gonza J, Ndejjo R, Ottosson A, Ekirapa-Kiracho E. Uganda’s village health team program. Health People. 2020;405. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perry S, Fair CD, Burrowes S, Holcombe SJ, Kalyesubula R. Outsiders, insiders, and intermediaries: village health teams’ negotiation of roles to provide high quality sexual, reproductive and HIV care in Nakaseke, Uganda. BMC Health Services Res. 2019;19:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4395-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hypertension Management Training Curriculum. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/healthprotection/ncd/training/hypertension-management-training.html. Accessed July 15, 2023.

- 15.The WHO STEPwise approach to noncommunicable disease risk factor surveillance (STEPS) Question-by-Question Guide; 2020.

- 16.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. PMID: 18929686. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Unger T, Borghi C, Charchar F, et al. 2020 International Society of Hypertension Global Hypertension Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2020;75(6):1334–1357. PMID: 32370572. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.120.15026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–349. PMID: 17947786. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kotwani P, Kwarisiima D, Clark TD, et al. Epidemiology and awareness of hypertension in a rural Ugandan community: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1151. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guwatudde D, Mutungi G, Wesonga R, et al. The epidemiology of hypertension in Uganda: findings from the national non-communicable diseases risk factor survey. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138991. PMID: 26406462. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiggundu T, Zalwango S, Migisha R, et al. Trends and distribution of hypertension in Uganda, 20162021; 2023.

- 22.Sani RN, Connelly PJ, Toft M, et al. Rural-urban difference in the prevalence of hypertension in West Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Human Hypertension. 2024;38(4):352–364. PMID: 35430612. doi: 10.1038/s41371-022-00688-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma JR, Mabhida SE, Myers B, et al. Prevalence of hypertension and its associated risk factors in a rural Black population of Mthatha Town, South Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(3):1215. PMID: 33572921. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18031215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okello S, Muhihi A, Mohamed SF, et al. Hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control and predicted 10-year CVD risk: a cross-sectional study of seven communities in East and West Africa (SevenCEWA). BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1–13. PMID: 33187491. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09829-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lionakis N, Mendrinos D, Sanidas E, Favatas G, Georgopoulou M. Hypertension in the elderly. World J Cardiol. 2012;4(5):135–147. PMID: 22655162. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v4.i5.135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oliveros E, Patel H, Kyung S, et al. Hypertension in older adults: assessment, management, and challenges. Clin Cardiol. 2020;43(2):99–107. PMID: 31825114. doi: 10.1002/clc.23303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Princewel F, Cumber SN, Kimbi JA, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with hypertension among adults in a rural setting: the case of Ombe, Cameroon. Pan African Med J. 2019;34(1). PMID: 32117515. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2019.34.147.17518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mustapha A, Ssekasanvu J, Chen I, et al. Hypertension and socioeconomic status in south central Uganda: a population-based cohort study. Global Heart. 2022;17(1). PMID: 35174044. doi: 10.5334/gh.1088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kandala N-B, Nnanatu CC, Dukhi N, Sewpaul R, Davids A, Reddy SP. Mapping the Burden of Hypertension in South Africa: a Comparative Analysis of the National 2012 SANHANES and the 2016 Demographic and Health Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5445. PMID: 34069668. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18105445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holmager TLF, Meyrowitsch DW, Bahendeka S, Nielsen J. Food intake and cardiometabolic risk factors in rural Uganda. Arch Public Health. 2021;79(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s13690-021-00547-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang DD, Li Y, Bhupathiraju SN, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and mortality: results from 2 prospective cohort studies of US men and women and a meta-analysis of 26 cohort studies. Circulation. 2021;143(17):1642–1654. PMID: 33641343. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Osei-Yeboah J, Owusu-Dabo E, Owiredu WK, Lokpo SY, Agode FD, Johnson BB. Community burden of hypertension and treatment patterns: an in-depth age predictor analysis:(The Rural Community Risk of Non-Communicable Disease Study-Nyive Phase I). PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0252284. PMID: 34383770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bamba G, Anne-Laure J, Kumar N, et al. Prevalence of severe hypertension in a Sub-Saharan African community. Int J Cardiol Hypertension. 2019;2:100016. PMID: 33447749. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchy.2019.100016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.