Abstract

Background

Role modelling is an effective teaching method in medical education. We sought to better understand role modelling by examining the insights of respected physician role models.

Methods

We conducted 30-minute in-depth interviews with 29 highly regarded role models at 2 large teaching hospitals. We coded the transcripts independently, and compared our coding for agreement. Content analysis identified several major categories of themes.

Results

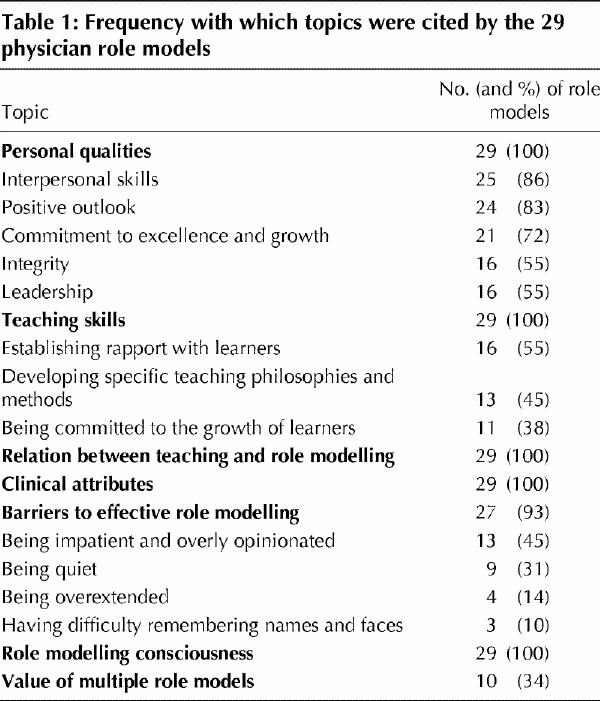

The informants identified specific characteristics related to role modelling. Subcategories under the domain of personal qualities included interpersonal skills, a positive outlook, a commitment to excellence and growth, integrity and leadership. Under the domain of teaching, the subcategories were establishing rapport with learners, developing specific teaching philosophies and methods, and being committed to the growth of learners. Subjects thought there was some overlap between teaching and role modelling, but felt that the latter was more implicit and more encompassing. Being a strong clinician was regarded as necessary but not sufficient for being an exemplary physician role model. Perceived barriers to effective role modelling included being impatient and overly opinionated, being quiet, being overextended, and having difficulty remembering names and faces. Physician role models described role modeling consciousness, in that they specifically think about being role models when interacting with learners. Subjects believed that medical learners should emulate multiple role models.

Interpretation

Highly regarded physician role models possess personal qualities, teaching abilities and exceptional clinical skills that outweigh their own barriers to serving as effective role models. Many of these positive attributes of role models represent behaviours that can be modified or skills that can be acquired.

Role modelling is thought to be an integral component of medical education.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 Physician role models affect the attitudes, behaviours and ethics of medical learners and foster professional values in trainees.7,8,9,10,11 They also influence the career choices of medical students.1,3,4,5,6,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21

Previous research about role modelling in medical education has consistently found that personal qualities, teaching skills and clinical competence are critical variables in the choice of role models by medical learners.1,5,22,23,24 These quantitative studies have not provided detailed information about the core elements of effective role modelling. We sought to better understand the many issues related to role modelling through the insights of respected physician role models.

Methods

We employed semistructured interviews for this qualitative study. The sampling strategy was purposive25 and relied on identifying informants who could be regarded as especially knowledgeable about issues related to role modelling. All internal medicine housestaff (postgraduate years 1, 2 and 3) at 2 large teaching hospitals in Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Hospital and Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, were asked to name the physicians whom they considered excellent role models.24 The 98 housestaff were given a general definition of a role model (“a person considered as a standard of excellence to be imitated”26) to allow for the identification of a wide range of attending physicians. Twenty-nine (97%) of the 30 most highly regarded role models within the Department of Medicine participated in the study (the other physician had left the institution and could not be interviewed). Each of the participating physicians had been selected as an excellent role model by 5 or more house officers (mean 12.3, range 5 to 43).

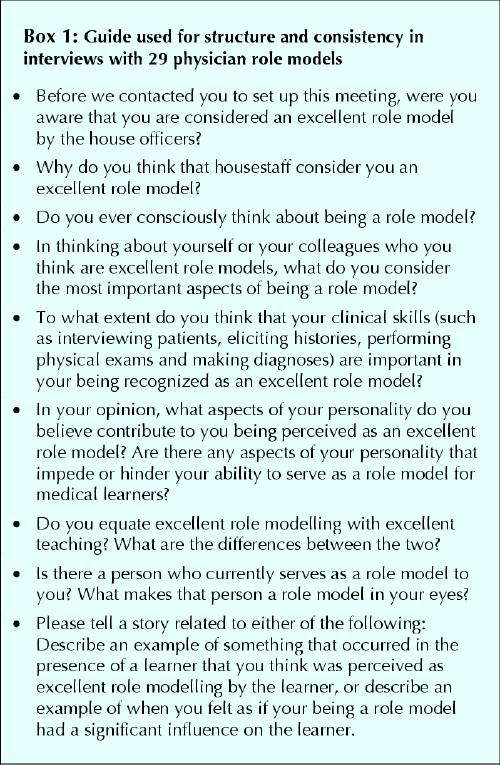

Interviews lasting approximately 30 minutes were conducted primarily in the offices of the participating physicians. One of us (S.M.W.) conducted all 29 interviews, using an interview guide (Box 1). All interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim.

Box 1.

An “editing analysis style”27 was used to analyze the transcripts. Each of us read and independently coded the transcripts. We then identified preliminary categories and subcategories, which were iteratively reviewed and revised. Finally, we developed a conceptual model to synthesize and integrate our findings. All decisions about coding and naming of categories were reached by consensus. We presented the findings to more than half of the informants, who verified that our interpretation of the data was appropriate.

The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center institutional review board.

Results

Subject characteristics

Twenty-six (90%) of the 29 attending physicians were male. The informants' mean age was 48.1 (range 35 to 75) years. One subject (3%) was an instructor, 7 (24%) were assistant professors, 12 (41%) were associate professors, and 9 (31%) were professors. The Divisions of Cardiology, Gastroenterology, General Internal Medicine, Geriatrics, Hematology/Oncology, Infectious Diseases, Pulmonary Medicine and Rheumatology were all represented by more than one physician, and one physician (3%) was from the Division of Endocrinology.

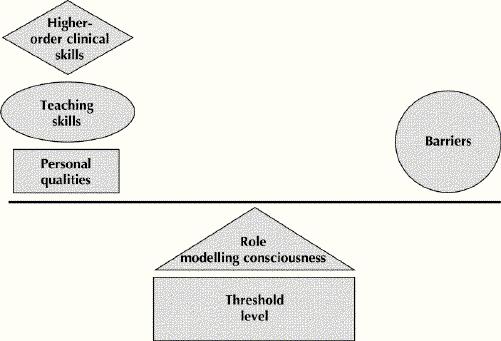

We identified several domains related to effective role modelling (Table 1). The relations between the domains are presented in the conceptual model (Fig. 1).

Table 1

Fig. 1: Illustration depicting a conceptual model for role modelling, wherein barriers to role modeling are balanced by a variety of positive attributes.

Personal qualities

Subcategories within the domain of personal qualities were interpersonal skills, a positive outlook, a commitment to excellence and growth, integrity and leadership qualities.

Interpersonal skills included being supportive, caring and respectful of others. An example is captured in the following quotation:

“I deal with house officers in a supportive way. I don't criticize them strongly, and I never lose my temper.”

Another role model mentioned that he is very careful to “attack the sin and not the sinner.”

Positive outlook included characteristics such as being enthusiastic, friendly and easy-going, as well as having job satisfaction (and showing it).

A general internist made the following comments: “I'm fairly easy-going. I try to make residents feel good about themselves. I try to inject some humour into my interactions with them.”

A gerontologist shared his opinions about complaining: “I place a very high negative value on complaining, and I think that people who complain would not make good role models.”

Commitment to excellence and growth encompassed creativity and inquisitiveness, a strong dedication to one's work, high standards, and being multitalented and well- balanced. One participant described a physician who had served as his role model:

“I would have liked to have been like him in every way. His family life, the way he approached his life, what he said, how he behaved, how he valued his students. Everything about him was something that you would like to emulate.”

Integrity related to being ethical and principled, being true to one's values and being genuine.

A pulmonary physician suggested that “Role model physicians have to have role model character and then it flows from there.… If you are trying to achieve certain standards, the motivation to achieve these standards permeates through all facets of the person.”

Several leadership qualities were described as important, including the ability to inspire, emphasis on team building, strength and pride, excellent communication skills, influence on others, and a nonjudgemental attitude.

Teaching skills

Subcategories within the domain of teaching included establishing rapport with learners, developing specific teaching philosophies and methods, and being committed to the growth of learners.

Study informants spoke about treating house officers as colleagues, being approachable, and being interested in learners as people, all of which contribute to establishing rapport.

One rheumatologist had this to say about his style for relating to house officers: “There's a certain comfortableness that I try to create. I am nonconfrontational [and] approachable, and I have the ability to get people to relax.”

Another physician spoke about the pleasure he derives from getting to know trainees: “I enjoy speaking with learners not only about cases but also about their interests, their career goals and their plans.”

The role models commented repeatedly about the development of specific teaching philosophies and methods. They stressed that learning should involve an interactive exchange between teachers and learners; should be learner-centred, encouraging self-awareness and responsibility on the part of the learner; should convey that teachers are also life-long learners who have limitations and make mistakes; and is facilitated by an approach that goes beyond the mere presentation of facts, particularly if teachers explicitly share their rationale and reasoning.

The themes that related to a commitment to the growth of learners included being a thoughtful advisor, being aware of the investment put into medical learners, increasing the self-esteem of learners and being generous (especially with time).

A gastroenterologist described the selflessness of some physician role models: “I think I've benefited from having role models, both clinically and in my research development, [who] have been generous with their time and honest about the struggles that they had to overcome to be successful.… They've been open, honest and generous.”

Relation between teaching and role modelling

The physicians contended that effectiveness in teaching and role modelling overlapped but that the latter entailed a more expansive skill set and was more implicit. The following quotation describes the wider set of responsibilities of role models:

“A teacher is someone who can teach you something or facilitate your learning, while a role model is a person from whom you want to gain some of their attributes. Role modelling is much more encompassing.”

Two physicians succinctly expressed the implicit nature of role modelling as follows:

“A role model may sometimes be articulating values silently and does this in multiple settings.”

“Role modeling has many more personal implications — the nebulous ideas of character and morality.”

Clinical attributes

Role models unanimously agreed that being a strong clinician was necessary but not sufficient for being considered a fine role model for medical learners. They felt that providing high-quality, compassionate care to patients was critical. These physician role models wanted to demonstrate other specific traits, felt to represent higher-order clinical skills, including “assuming responsibility in difficult clinical situations,” “going the extra mile for patients” and “being a patient's advocate.”

Barriers to effective role modelling

Subjects identified several factors that took away from their ability to serve as role models, including being impatient, overly opinionated and inflexible.

One general internist said, “I am easily frustrated and I can sometimes be quick to show that.… As a result, I can have flashes of being ticked off or being angry. I can be a little impatient.”

Other characteristics cited as barriers to effective role modelling include being quiet and reserved, being overextended because of too many responsibilities, and having difficulty remembering names and faces.

Role modelling consciousness

Physician role models consciously think about being role models when interacting with medical trainees. Informants were well aware that medical learners are watching the medical faculty closely. Three informants had this to say:

“When I work with residents caring for patients with substance abuse, I truly want to become a role model for how physicians can successfully take care of these patients.”

“I make a conscious effort to role model professionalism and humanism.”

“I think about trying to set a good example.… I realize that trainees are learning from us and that we ought to try to set the right tone, show equanimity and try to show how we think.”

Value of multiple role models

Although physician role models were considered to embody a range of talents, the subjects felt that it was valuable for medical learners to identify and emulate multiple role models.

One pulmonologist commented on the many physicians that he strives to copy: “Certain components of many people are ongoing role models for me. I respect that and I look up to them for their abilities. I try to learn from them.”

Another physician explained, “It's helpful using yourself as an example and also pointing out examples in other people and other situations.”

Conceptual model of role modelling

We developed the following conceptual model of role modelling. To be considered a role model by medical learners, a threshold level of clinical skills is required. If this criterion is met, there are other attributes that together establish certain physicians as excellent role models. The barriers described above can hinder an attending physician's ability to serve as a role model and may negate some of their positive qualities (Fig. 1).

A rheumatologist expressed this idea concisely: “I think you have to have clinical skills, knowledge and an analytical ability, or no one is going to even begin to think of you as a role model. But if you only have those things, you're not a role model either. So I think there are a group of skills or virtues that are permissive and then there are those which allow the permitted to have an impact on other people.”

Most informants were cognizant that learners are always watching them, and many described deliberate thoughts and efforts related to conducting themselves as role models. This “role model consciousness” was described as being especially noticeable in difficult or stressful situations. Under these circumstances, physician role models attempt to perform in an exemplary manner, demonstrating higher-order clinical skills. Two physicians explained:

“I try to be a role model when patients are antagonistic or obviously upset.”

“One of the things that trainees may have picked up on, and perhaps why they hold me as a role model, is my interactions with patients and their families under very difficult circumstances [in the intensive care unit], particularly end-of-life situations.”

The value of multiple role models, each having both positive attributes and inherent limitations, is obvious and logical. Less apparent is the fact that different clinical or teaching settings may play to the strengths or weaknesses of an individual physician, such that one's status as a positive, influential role model may vary depending on the context and setting.

Interpretation

A group of experts, the most highly regarded role models in a large and respected department of medicine, provided detailed descriptions about the specific personal qualities, teaching skills and clinical acumen that they considered most critical for effective role modelling. These findings may increase the awareness of medical educators about role modelling and may also provide suggestions for physicians who want to become excellent role models. Our findings may also have implications for faculty development programs that focus on teaching skills for physicians.

The conceptual model for effective role modelling that emerged from the data has face validity and is consistent with theory28,29 and previous research.1,3,5,6,17,24 The proposed conceptual model underscores that strong clinical skills are required if medical learners are to consider an attending physician as a role model. Whether suitable clinicians are selected as role models worth emulating ultimately depends on how they measure up in other areas. Consistency of good behaviour, both verbal and nonverbal, was felt to be indispensable for those who are considered distinguished clinicians.30 In addition, our informants spoke of role models' ability to step up their performance and be truly exemplary in difficult and demanding situations. A good analogy comes from the game of baseball: “gold glove fielders” are those who make all of the routine plays and, when needed, also make the spectacular plays.

Most of the informants were aware of their role model status and reported that they consciously think about role modelling when interacting with medical trainees. Heightened awareness of role modelling might lead attending physicians to seek out additional opportunities to model particular attitudes, behaviours or skills, and to teach often-neglected aspects of medicine and professionalism.31 This less passive approach to role modelling involves 3 steps: demonstrating the skill or behaviour, commenting on what was done and explaining what was done.32

It is interesting that virtually all of the most highly regarded role models at our institutions were easily able to identify barriers that limited their effectiveness as role models. Previously reported findings indicate that reflection, an awareness of one's shortcomings and a sense of humility are important aspects of personal growth.33,34 As illustrated by the balance in the conceptual model (Fig. 1), it appears that barriers do not preclude successful role modelling as long as the impediments are compensated by proficiency in other areas. Individual physicians striving to enhance their effectiveness as role models may want to consider their limitations and develop strategies for improvement.

Several limitations of the study should be considered in interpreting the results. First, we studied a relatively small number of attending physicians. Because the informants were highly respected role models, they represented an ideal source of “expert opinion.” Our ability to interview all but 1 of the 30 most highly regarded role models that we identified also strengthens the validity of the results. Nonetheless, caution should be exercised in generalizing the findings beyond our study. Second, the study relied exclusively on self-reporting. Although future studies that directly observe physician role models could test our findings with respect to actual behaviours, self-reporting may be the most direct approach for measuring attitudes and beliefs and is an important first step in identifying relevant issues.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that attending physician role models possess a certain level of clinical skills and are conscious of opportunities for role modelling. They also have personal qualities, specific teaching skills and higher-order clinical skills that outweigh the barriers to role modelling that they experience. Many of the attributes identified by our informants represent behaviours that can be modified or skills that can be acquired. We hope that identifying these attributes will prove helpful to individuals and institutions interested in enhancing effective role modelling.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Drs. Wright and Carrese contributed substantially to all aspects of this work including conception, design, data acquisition, writing and revising the manuscript. Each gave final approval of the version to be published.

Acknowedgements: We are indebted to Dr. David Kern and Dr. Amy Knight for their suggestions and review of the manuscript.

Dr. Wright is an Arnold P. Gold Foundation Assistant Professor of Medicine. Dr. Carrese was a Robert Wood Johnson Generalist Physician Faculty Scholar when this study was conducted.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Scott M. Wright, Division of General Internal Medicine, B2N, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, 4940 Eastern Ave., Baltimore MD 21224-2780; fax 410 550-2715; smwright@jhmi.edu

References

- 1.Wright S. Examining what residents look for in their role models. Acad Med 1996;71:290-2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Linzer M, Slavin T, Mutha S, Takayama JI, Branda L, VanEyck S, et al. Admission, recruitment, and retention: finding and keeping the generalist-oriented student. SGIM Task Force on Career Choice in Primary Care and Internal Medicine. J Gen Intern Med 1994;9(4 Suppl 1):S14-23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Ficklin FL, Browne VL, Powell RC, Carter JE. Faculty and house staff members as role models. J Med Educ 1988;63:392-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Shuval JT, Adler I. The role of models in professional socialization. Soc Sci Med 1980;14A:5-14. [PubMed]

- 5.Wright S, Wong A, Newill C. The impact of role models on medical students. J Gen Intern Med 1997;12:53-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Neumayer L, Konishi G, L'Archeveque D, Choi R, Ferrario T, McGrath J, et al. Female surgeons in the 1990s: academic role models. Arch Surg 1993;128:669-72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Barondess J. The GPEP report: III. Faculty involvement. Ann Intern Med 1985;103:454-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Branch WT, Kroenke K, Levinson W. The clinician-educator — present and future roles. J Gen Intern Med 1997;12(Suppl 2):S1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.The role of the training program. In: Guide to evaluation of residents in internal medicine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: American Board of Internal Medicine; 1992. p. 1-8.

- 10.Mufson MA. Professionalism in medicine: the department chair's perspective on medical students and residents. Am J Med 1997;103:253-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Kopelman LM. Values and virtues: How should they be taught? Acad Med 1999; 74:1307-10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Mutha S, Takayama J, O'Neil E. Insights into medical students' career choices based on third- and fourth-year students' focus-group discussions. Acad Med 1997;72:635-40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.McMurray J, Schwartz M, Genero N, Linzer M. The attractiveness of internal medicine: a qualitative analysis of the experiences of female and male medical students. Ann Intern Med 1993;119:812-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Babbott D, Levey GS, Weaver SO, Killian CD. Medical student attitudes about internal medicine: a study of U.S. medical school seniors in 1988. Ann Intern Med 1991;114:16-22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Hunt DK, Badgett RG, Woodling AE, Pugh JA. Medical student career choice: Do physical diagnosis preceptors influence decisions? Am J Med Sci 1995; 310(1):19-23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Rubeck RF, Donnelly MB, Jarecky RM, Murphy-Spencer AE, Harrell PL, Schwartz RW. Demographic, educational, and psychosocial factors influencing the choices of primary care and academic medical careers. Acad Med 1995; 70(4):318-20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Reuler J, Nardone D. Role modeling in medical education. West J Med 1994; 160(4):335-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Lublin JR. Role modeling: a case study in general practice. Med Educ 1992; 26(2):116-22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Levinson W, Kaufman K, Clark B, Tolle SW. Mentors and role models for women in academic medicine. West J Med 1991;154(4):423-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Ambrozy MD, Irby DM, Bowen JL, Burack JH Carline JD, Stritter FT. Role models' perceptions of themselves and their influence on students specialty choice. Acad Med 1997;72:1119-21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Lieu T, Schroder S, Altman D. Specialty choices at one medical school: recent trends and analysis of predictive factors. Acad Med 1989;64:622-9. [PubMed]

- 22.Paukert JL, Richards BF. How medical students and residents describe the roles and characteristics of their influential clinical teachers. Acad Med 2000; 75:843-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Matthews C. Role modeling: How does it influence teaching in family medicine? Med Educ 2000;34:443-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Wright SM, Kern DE, Kolodner KB, Howard DM, Brancati FL. Attributes of excellent attending physician role models. N Engl J Med 1998;339:1986-93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Bernard HR. Research methods in anthropology: qualitative and quantitative approaches. 2nd ed. London (UK): Sage Publications; 1994.

- 26.Webster's new world dictionary, college edition. London: World Publishing Company; 1959.

- 27.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing qualitative research. Newbury Park (CA): Sage Publications; 1992.

- 28.Bandura A. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs (NJ): Prentice Hall; 1977.

- 29.Mazur J. Learning and behavior. 3rd ed. Englewood Cliffs (NJ): Prentice Hall; 1994.

- 30.Rosenow EC 3rd. The challenge of becoming the distinguished clinician. Mayo Clin Proc 1999;74:635-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Hundert EM, Hafferty F, Christakis D. Characteristics of the informal curriculum and trainees' ethical choices. Acad Med 1996;71:624-42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Branch WT Jr, Kern D, Haidet P, Weissmann P, Gracey CF, Mitchell G, et al. The patient–physician relationship. Teaching the human dimensions of care in clinical settings. JAMA 2001;286:1067-74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Westberg J, Jason H. Fostering learners' reflection and self-assessment. Fam Med 1994;26:278-82. [PubMed]

- 34.Schon DA. Educating the reflective practitioner: toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bassey Publishers; 1987.