Case

Mrs. J, a 72-year-old woman whom you are treating for continuing hip pain related to arthritis (diclofenac 75 mg/d), has been relatively healthy, but her blood pressure has been increasing recently. Over the last 3 visits it has been 184/92 mm Hg on average. Mrs. J is physically active and uninterested in dietary advice. She is a nonsmoker who does not drink alcohol. Her body mass index is 26 kg/m2, and physical examination reveals a pulsatile mass in the upper abdomen. The rest of the examination is unremarkable. Electrolyte and creatinine levels, complete blood count, and urinalysis and electrocardiography results are all within normal ranges. The fasting glucose level is 5.6 mmol/L, total cholesterol 5.4 mmol/L, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol 1.1 mmol/L and triglycerides 1.3 mmol/L. Ultrasonography of the abdomen shows a tortuous aorta with no aneurysm. What drugs are recommended as starting therapy? Once this therapy has been started, what will you add as a second drug? As a third drug? Does the most recent evidence concerning treatment of hypertension, reflected in the 2001 revisions of the Canadian recommendations for the management of hypertension, mandate any changes from previous practice in the approach to therapy?

This article summarizes the “take-home messages” from the 2001 Canadian recommendations for the management of hypertension1,2 and describes how they might affect the care of a patient such as Mrs. J. The Canadian hypertension recommendations are based on a systematic review of the relevant literature, assessed according to an evidence-based grading scheme.3 Since 1999 there have been annual updates to Canada's hypertension recommendations.4,5,6,7 The 2001 version includes an updated section on the management of hypertension in people with diabetes and new recommendations for therapy after the acute phase of stroke or transient ischemic attack. The new recommendations also specify a lower threshold for initiating therapy in those over 60 years of age. The previous recommendation to switch first-line therapies when response is inadequate has been dropped in favour of a recommendation to combine first-line therapies in this situation. There are also new and comprehensive sections on management of patients with hyperaldosteronism and pheochromocytoma. The full recommendations and their scientific rationale are published elsewhere.1,2

Diagnosis of hypertension

Was Mrs. J's blood pressure measured accurately?

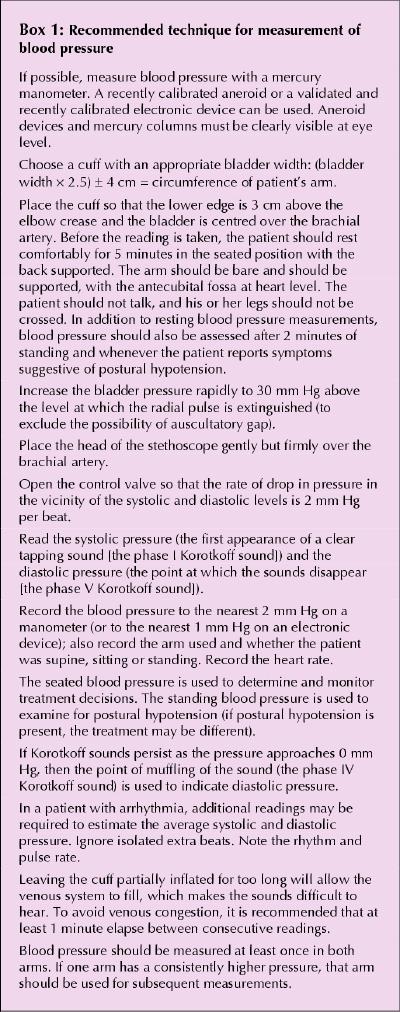

Accurate measurement of blood pressure is the first step in diagnosing hypertension and should be carried out at all appropriate visits (Box 1).

Box 1.

One of the most important aspects of blood pressure measurement is having the patient rest in a quiet, comfortable room for 5 minutes immediately before readings are taken. The patient should rest in the room and in the position (usually seated) in which the first readings will be taken. Talking increases blood pressure by, on average, 7 mm Hg,8 so speech should be discouraged. It is also important to assess blood pressure in various positions (seated or prone, standing) and in different limbs (both arms and one or both legs). These simple steps can help to determine if there is an obstruction of blood flow to one arm that could obscure a diagnosis of hypertension; they can also provide clues to secondary causes of hypertension or atherosclerosis. A drop in blood pressure of more than 20/10 mm Hg when the patient is standing (relative to the seated or prone position) indicates the need for caution during antihypertensive therapy.

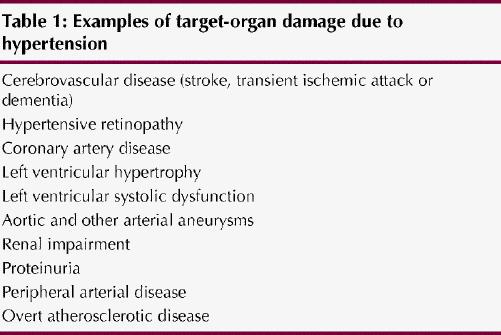

Hypertension can be diagnosed immediately if there is a hypertensive urgency or crisis or in 3 visits if the patient is clinically stable but has target-organ damage (Table 1). However, diagnosis requires up to 5 visits if there is no target-organ damage and the initial blood pressure is less than 180/105 mm Hg. The recommendation to take up to 5 visits for a diagnosis represents a substantial workload for the physician, but patients whose blood pressure falls to less than 140/90 mm Hg with observation are not at greater risk of cardiovascular disease because of their blood pressure.9,10,11

Table 1

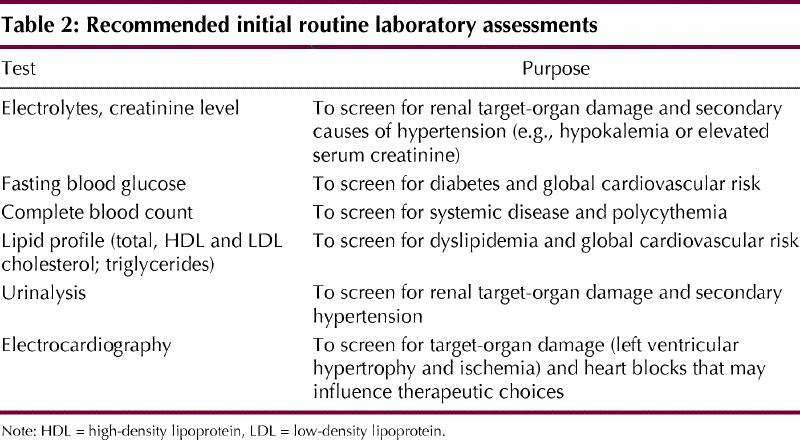

What other laboratory tests should be ordered?

All hypertensive patients should undergo routine laboratory assessment (Table 2). Determination of serum electrolyte levels is particularly important, since hypokalemia is a marker of primary or secondary hyperaldosteronism. Elevated serum creatinine level and abnormal urinalysis results (e.g., casts, hematuria or proteinuria) are important as potential indicators of renal causes of hypertension or hypertensive target-organ damage and as cardiovascular risk factors. Electrocardiography is recommended both to assess for target-organ damage (e.g., old myocardial infarction) and to indicate the prognosis (e.g., left ventricular hypertrophy indicates a poor prognosis). A complete blood count is recommended to screen for systemic disease.

Table 2

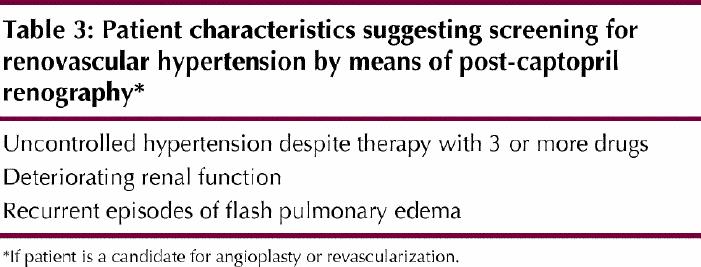

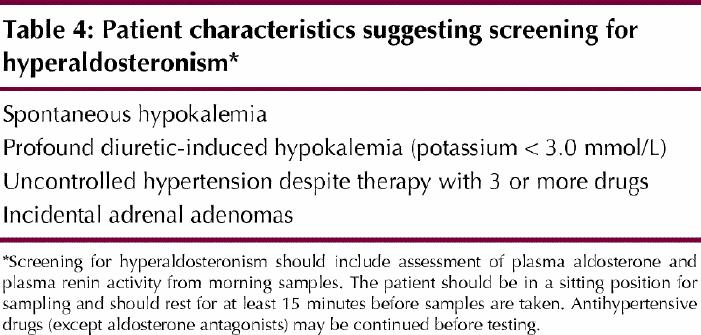

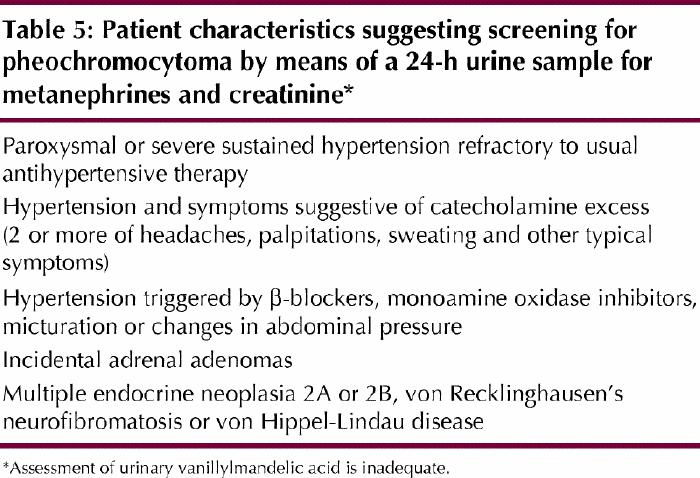

Patients with features of secondary hypertension should undergo further testing. The 2001 update includes new recommendations for screening patients for renovascular hypertension (Table 3), hyperaldosteronism (Table 4) and pheochromocytoma (Table 5). It is estimated that renovascular hypertension occurs in approximately 1% of hypertensive patients, hyperaldosteronism in 1% to 15% and pheochromocytoma in approximately 0.1%. (Comprehensive recommendations for the diagnosis and management of hyperaldosteronism and pheochromocytoma are included with the detailed hypertension recommendations.1) False-positive results are common in unselected patients, so these tests should not be ordered routinely.

Table 3

Table 4

Table 5

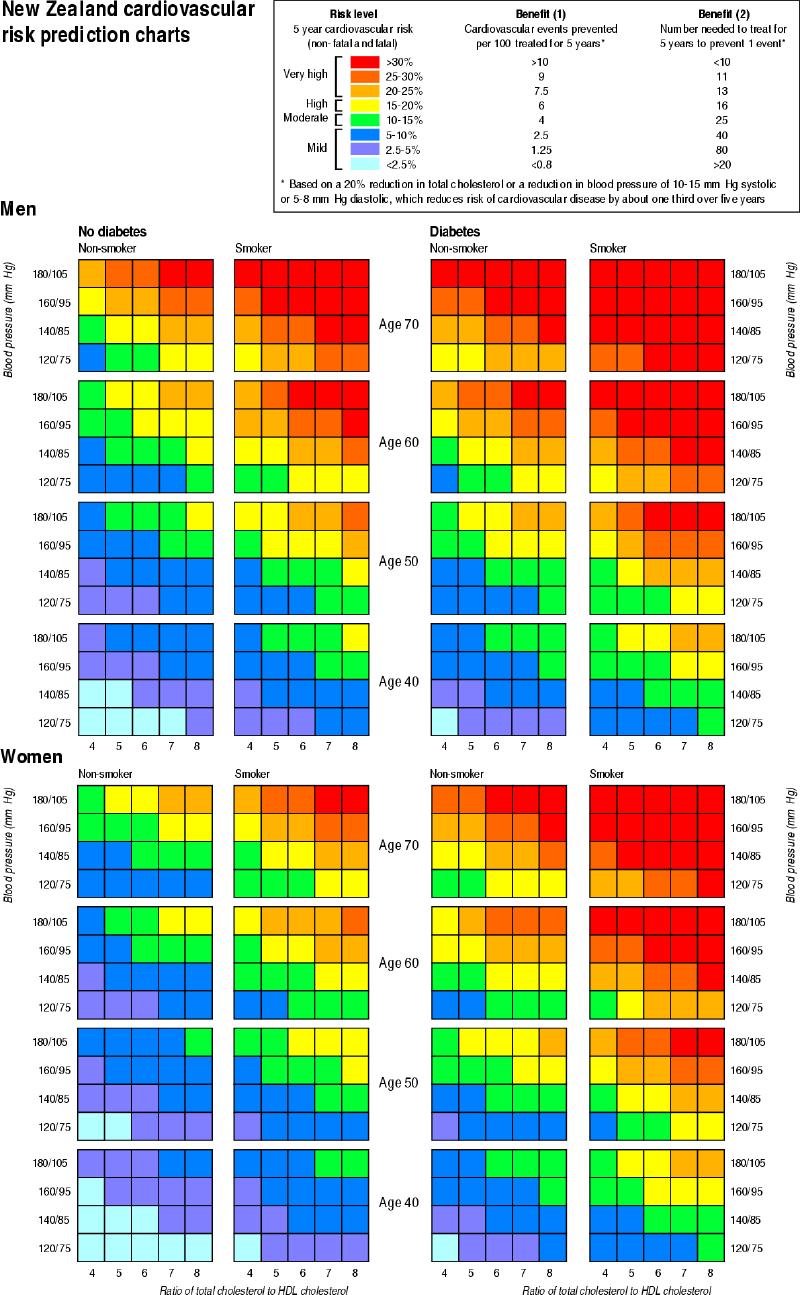

A fasting glucose and lipid profile (total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides) is essential to determine the patient's cardiovascular prognosis. Because cardiovascular risk can vary more than 10-fold at a given blood pressure level, it is important to assess the patient's global cardiovascular risk and adopt a multifactorial approach for treating hypertension. A variety of methods, including charts, formulas, and programs for desktop computers or personal digital assistants, can be used.12,13,14,15,16 For example, the use of a risk chart can improve a patient's reduction in systolic blood pressure.17 According to the New Zealand risk chart shown in Fig. 1, Mrs. J's 5-year risk of a cardiovascular event is 15% to 20%.

Fig. 1: The New Zealand risk charts represent a quick and easy method of categorizing a patient's 5-year cardiac risk on the basis of blood pressure, age, smoking status, presence of diabetes and ratio of total to high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol.12 For people with the same blood pressure, there is substantially greater risk when other risk factors are present. To use the chart for the patient described in this article, select the bottom left column of risk panels (for women who are not diabetic and who are not smokers). Using the age category of 70 years and the highest of her systolic and diastolic pressure, select the blood pressure category of 180/105 mm Hg. Her ratio of total to HDL cholesterol is 4.9 or close to 5, which puts her in a yellow risk category. Yellow corresponds to a risk of 15% to 20% of a cardiovascular event within 5 years. Antihypertensive treatment would be expected to prevent 1 event for every 16 people treated. The Framingham 10-year risk assessment methods may also be used.13–16 Reproduced with permission from BMJ.

Is office-based measurement of blood pressure enough?

Self-measurement and 24-hour ambulatory measurement of blood pressure continue to be recommended for assessing office-induced elevation of blood pressure; self-measurement is also recommended as a way to improve patient compliance with therapy. Only devices meeting international standards should be used for this purpose.18,19 Daytime blood pressures above 135/85 mm Hg obtained with self-measurement or ambulatory measurement are associated with elevated cardiovascular risk.

Management

What lifestyle modifications should Mrs. J undertake?

Individualized lifestyle modification is recommended for all patients who have or are at risk for hypertension. In selected patients, a single lifestyle intervention can prevent hypertension from developing or can reduce blood pressure to an extent similar to that accomplished by a single antihypertensive medication. The lifestyle modification might be the sole therapy or it might be used in conjunction with pharmacotherapy to significantly enhance the effectiveness of the medication.2,20 All of the lifestyle modifications suggested in the hypertension recommendations improve general health, in addition to lowering blood pressure. A diet high in fresh fruit, vegetables and low-fat dairy products and low in saturated fat and salt is effective at reducing blood pressure. Commonly referred to as the DASH diet,21 this diet is also consistent with Canada's guide to healthy eating.22 Regular cardiorespiratory physical activity (e.g., brisk walking) is also a highly effective means of lowering blood pressure.23 Low-risk alcohol consumption, defined as abstinence or moderate alcohol consumption (less than 2 standard drinks per day) is effective for heavy alcohol consumers. For those who are overweight, the single most effective intervention is weight loss. For comprehensive reduction of cardiovascular risk, a smoke-free environment is critical.

What pharmacotherapy would you recommend?

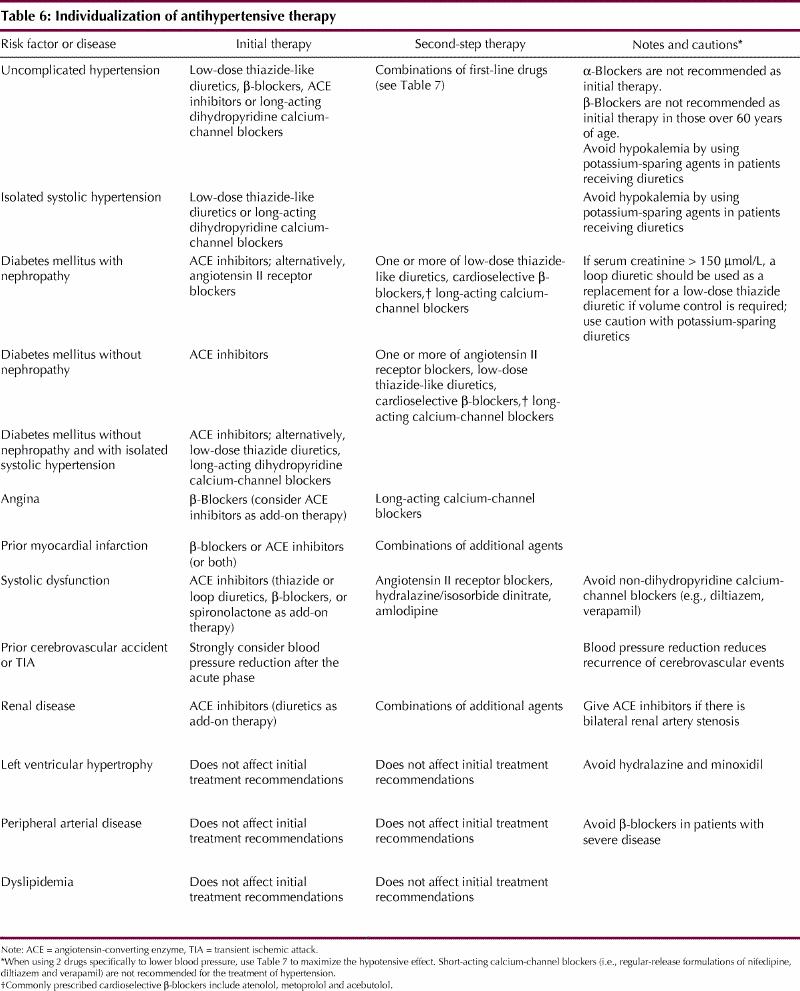

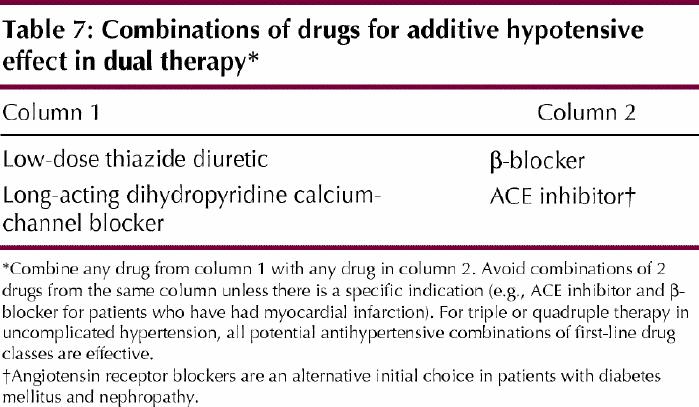

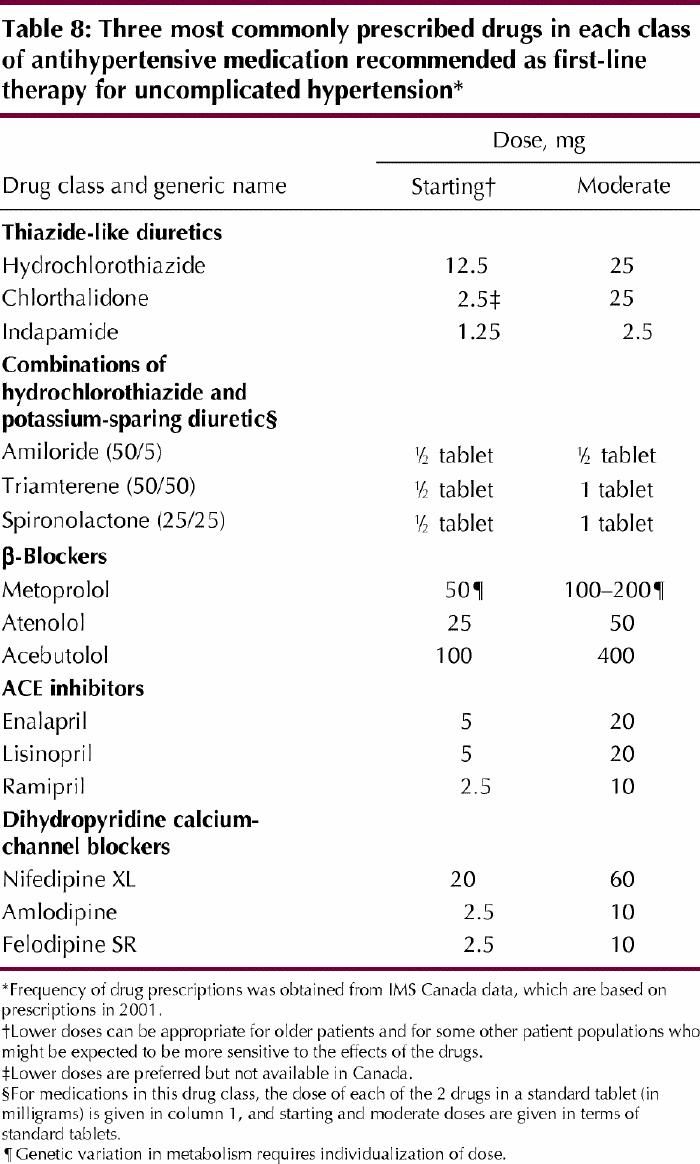

Drug treatment is recommended if the diastolic blood pressure is greater than 90 mm Hg and the patient has cardiovascular disease, other target-organ damage or cardiovascular risk factors. Most hypertensive patients have additional risk factors or target-organ damage; however, if such are not present, the recommendation is to treat diastolic blood pressure of 100 mm Hg or more and systolic blood pressure of 160 mm Hg or more. Drugs suitable as initial treatment for hypertension are listed in Table 6 (and guidelines for combining drugs are given in Table 7; see also below). Table 8 summarizes the most common examples of the major drug classes and gives starting and moderate doses. β-blockers are not recommended as first-line therapy in those 60 years of age or older, and α-blockers are not recommended as first-line therapy. In these settings, these drugs are not as effective as diuretics in preventing cardiovascular complications. Short-acting calcium-channel blockers may increase cardiovascular complications and should not be used as antihypertensive agents. Low-dose thiazide diuretics are effective first-line drugs. Diuretics may not prevent cardiovascular complications if hypokalemia occurs.24 Prevention of hypokalemia by using low doses and combinations of thiazide and potassium-sparing diuretics is important.

Table 6

Table 7

Table 8

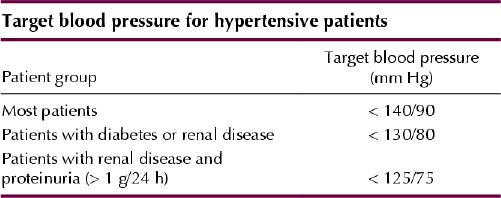

What blood pressure target would you set for Mrs. J?

Regardless of the approach used, perhaps the most important message from the recommendations is that we as physicians must do a better job in helping our patients to achieve the recommended blood pressure targets. Treatment targets for hypertension should be less than 140/90 mm Hg in general, less than 130/80 mm Hg in those with diabetes or renal disease, and less than 125/75 mm Hg in those with renal disease and proteinuria (greater than 1 g/24 hours).

Combinations of medications should be used if the initial choice of drug is only partially effective in lowering blood pressure to the target level. Switching to an alternative first-line agent should be considered only if there is intolerance. Table 7 indicates recommended combinations of first-line agents. For patients with uncomplicated hypertension who are receiving triple or quadruple therapy, all potential combinations of first-line antihypertensive agents are effective. Several factors may explain lack of response to appropriate single or combination medications: nonadherence, secondary hypertension, interfering drugs or lifestyle (e.g., weight gain, excess sodium or alcohol consumption), or office-induced increases in blood pressure (the “white coat effect”).

Case revisited

Mrs. J's blood pressure is probably being adversely affected by the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (diclofenac) that she is receiving for her arthritis.25 Acetaminophen should be tried to determine if it will provide adequate pain relief. Antihypertensive pharmacotherapy is indicated to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease. The first-line choice for systolic and diastolic hypertension is a low-dose thiazide diuretic, an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or a long-acting dihydropyridine calcium-channel blocker. β-Blockers are less effective in those over 60 years of age, such as Mrs. J, and should not be used as first-line therapy in this age group.

The patient is first given a low-dose thiazide diuretic, but her serum potassium level is 3.2 mmol/L on follow-up, so treatment is switched to a potassium-sparing diuretic combination drug. You anticipate that additional agents will probably be required to achieve a target blood pressure of less than 140/90 mm Hg; use Table 7 to select an ACE inhibitor as the second agent. You may have to discontinue the potassium-sparing diuretic to avoid hyperkalemia. If a third agent is required, either a β-blocker or a dihydropyridine calcium-channel blocker would be reasonable (Table 7).

Comments

Hypertension is a growing concern in our society. The increase in the prevalence of this condition is in part related to changes in levels of physical activity and diet and increases in obesity and the average age of the Canadian population. Major pharmacological advances that should have made blood pressure control easier have instead resulted in an overreliance on single-drug therapy. This has in turn been associated with deterioration in blood pressure control and increases in treatment costs.26 Systematic approaches to managing hypertension are needed. Physicians should become familiar with combination antihypertensive therapy to optimize patient outcomes and prevent disease. Future efforts to improve blood pressure management need to incorporate greater participation by patients and multidisciplinary health care teams.

Figure.

Acknowledgments

The Canadian Hypertension Recommendations Working Group acknowledges the expert secretarial support of Leslie Holmes.

Footnotes

Contributors: Dr. Campbell, the principal author, wrote the paper and revised it according to input from Drs. Feldman and Drouin. Drs. Feldman and Drouin provided substantial input toward and provided a critique of the original manuscript and subsequent revisions.

This project was sponsored by the Canadian Coalition for High Blood Pressure Prevention and Control, the Canadian Hypertension Society, the College of Family Physicians of Canada, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, and the Adult Disease Division and Bureau of Cardio-Respiratory Diseases and Diabetes, Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention and Control, Health Canada.

The work was financially supported, through unrestricted grants, by Bayer Health Care Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim-GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb Canada Inc., Crystaal, Merck Frosst Canada Inc., Novartis Pharmaceuticals Canada Inc., Pfizer Canada Inc., Servier Canada Inc. and Solvay Pharma.

Competing interests: Drs. Campbell, Feldman and Drouin are paid consultants for several companies that manufacture drugs used in the treatment of hypertension and in this capacity have received travel assistance to attend advisory board meetings. They have also received honoraria and other compensation from several companies for conducting research related to the material in this article, as well as speaker fees and educational grants.

Correspondence to: Dr. Norman R.C. Campbell, Rm. 1435, Health Sciences Centre, 3330 Hospital Dr. NW, Calgary AB T2N 4N1; fax 403 283-6151; ncampbel@ucalgary.ca

References

- 1.Zarnke KB, McAlister FA, Campbell NRC, Levine M, Schiffrin EL, Grover S, et al, for Canadian Hypertension Recommendations Working Group. The 2001 Canadian recommendations for the management of hypertension: part one — assessment for diagnosis, cardiovascular risk, causes and lifestyle modification. Can J Cardiol 2002;18:604-24. [PubMed]

- 2.McAlister FA, Zarnke KB, Campbell NRC, Feldman RD, Levine M, Mahon J, et al, for Canadian Hypertension Recommendations Working Group. The 2001 Canadian recommendations for the management of hypertension: part two — therapy. Can J Cardiol 2002;18:625-41. [PubMed]

- 3.Zarnke KB, Campbell NRC, McAlister F, Levine M, for the Canadian Hypertension Recommendations Working Group. A novel process for updating recommendations for managing hypertension: rationale and methods. Can J Cardiol 2000;16:1094-102. [PubMed]

- 4.Feldman RD, Campbell N, Larochelle P, Bolli P, Burgess ED, Carruthers SG, et al, for the Task Force for the Development of the 1999 Canadian Recommendations for the Management of Hypertension. 1999 Canadian recommendations for the management of hypertension. CMAJ 1999;161(12 Suppl):S1-17. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Canadian Hypertension Recommendations Working Group. Summary of the 2000 Canadian hypertension recommendations. Can J Cardiol 2001;17: 535-8. [PubMed]

- 6.Zarnke KB, Levine M, McAlister FA, Campbell NRC, Myers MG, McKay DW, et al, for Canadian Hypertension Recommendations Working Group. The 2000 Canadian recommendations for the management of hypertension: part two — diagnosis and assessment of people with high blood pressure. Can J Cardiol 2001;17:1249-63. [PubMed]

- 7.McAlister FA, Levine M, Zarnke KB, Campbell N, Lewanczuk R, Leenan F, et al, for Canadian Hypertension Recommendations Working Group. The 2000 Canadian recommendations for the management of hypertension: part one — therapy. Can J Cardiol 2001;17:543-559. [PubMed]

- 8.Campbell NRC, McKay DW. Accurate blood pressure measurement: Why does it matter? [editorial]. CMAJ 1999;161:277-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Rosner B, Polk BF. Predictive values of routine blood pressure measurements in screening for hypertension. Am J Epidemiol 1983;117:429-42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Perry HM, Miller JP. Difficulties in diagnosing hypertension: implications and alternatives. J Hypertens 1992;10:887-96. [PubMed]

- 11.Brueren MM, Petri H, van Weel C, van Ree JW. How many measurements are necessary in diagnosing mild to moderate hypertension? Fam Pract 1997; 14: 130-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Jackson R. Updated New Zealand cardiovascular disease risk–benefit prediction guide. BMJ 2000;320:709-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Guidelines Subcommittee. 1999 World Health Organization — International Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension. J Hypertens 1999;17:151-83. [PubMed]

- 14.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 2001;285:2486-97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Grundy SM, Pasternak R, Greenland P, Smith S, Fuster V. Assessment of cardiovascular risk by use of multiple-risk-factor assessment equations. A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology. Circulation 1999;100:1481-92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Ramsay LE, Williams B, Johnston GD, MacGregor GA Poston L, Potter JF, et al. Guidelines for management of hypertension: report of the third working party of the British Hypertension Society. J Hum Hypertens 1999;13:569-92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Montgomery AA, Fahey T, Peters TJ, MacIntosh C, Sharp DJ. Evaluation of computer based clinical decision support system and risk chart for management of hypertension in primary care: randomized controlled trial. BMJ 2000; 320:686-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.O'Brien E, Waeber B, Parati G, Staessen J, Myers M, on behalf of European Society of Hypertension Working Group on Blood Pressure Monitoring. Blood pressure measuring devices: recommendations of the European Society of Hypertension. BMJ 2001;322:531-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.British Hypertension Society Information Service. Automatic digital blood pressure devices for clinical use or home self-measurement. London (UK): British Hypertension Society; [no date]. Available: www.hyp.ac.uk/bhsinfo/bpmdigit.html (accessed 2002 Aug 13).

- 20.Campbell NRC, Burgess E, Taylor G, Wilson E, Cleroux J, Fodor JG, et al. Lifestyle changes to prevent and control hypertension. Do they work? CMAJ 1999; 160:1341-3. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, Appel LJ, Bray GA, Harsha D, et al. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet. N Engl J Med 2001;344:3-10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Canada's food guide to health eating for people four years and over. Ottawa: Health Canada; rev 2001 July. Available: www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hppb/nutrition/pube/foodguid/foodguide.html (accessed 2002 Aug 13).

- 23.Cleroux J, Feldman RD, Petrella RJ. Lifestyle modifications to prevent and control hypertension. 4. Recommendations on physical exercise training. CMAJ 1999;160(9 Suppl):S21-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Franse L, Pahor M, Di Bari M, Somes GW, Cushman WC, Applegate WB. Hypokalemia associated with diuretic use and cardiovascular events in the systolic hypertension in the elderly program (SHEP). Hypertension 2000;35: 1025-30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Wooltorton E. What's all the fuss? Safety concerns about COX-2 inhibitors rofecoxib (Vioxx) and celecoxib (Celebrex). CMAJ 2002;166:1692-3. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Wolf HK, Andreou P, Bata IR, Comeau DG, Gregor RD, Kephart G, et al. Trends in the prevalence and treatment of hypertension in Halifax County from 1985 to 1995. CMAJ 1999;161:699-704. [PMC free article] [PubMed]