Abstract

Background

Individuals living with cancer and survivors of cancer who self-identify as Hispanic experience higher pain burden and greater barriers to pain management compared with their non-Hispanic counterparts. The Society for Integrative Oncology-ASCO guideline recommends acupuncture and massage for cancer pain management. However, Hispanic individuals’ expectations about these modalities remain under-studied and highlight a potential barrier to treatment utilization in this population.

Methods

We conducted a subgroup analysis of baseline data from two randomized clinical trials to evaluate ethnic differences in treatment expectations about integrative pain treatment modalities among Hispanic and non-Hispanic cancer patients and survivors of cancer. The Mao Expectancy of Treatment Effects (METE) instrument was used to measure treatment expectancy for electro-acupuncture, auricular acupuncture, and massage therapy.

Results

Results of this study demonstrated that Hispanic participants reported greater expectation of benefit from electroacupuncture, auricular acupuncture, and massage (all P<0.01). After controlling for age, gender, race, and education, Hispanic ethnicity remained significantly associated with greater expectation of benefit from integrative therapies for pain (coef.=1.47, 95% CI, 0.67–2.27). Non-white race (coef.=1.04, 95% CI, 0.42–1.65), no college education (coef.=1.16, 95% CI, 0.59–1.74), and female gender (coef.=0.94, 95% CI, 0.38–1.50) were also associated with a greater expectation of benefit from integrative therapies.

Conclusions

Pain management should be informed by a shared decision-making approach that aligns treatment expectancy with treatment selections to optimize outcomes. Compared with non-Hispanic participants, Hispanic individuals reported higher expectation of benefit from acupuncture and massage, highlighting the potential role for integrative therapies in addressing ethnic pain disparities.

Trial Registration: NCT02979574; NCT04095234

Background and Conceptual Framework

Hispanic cancer patients and survivors experience a greater pain and symptom burden relative to their non-Hispanic white (NHW) counterparts, but Hispanic individuals are more likely to be under-treated for their pain and to have doubts about relying solely on medications.1,2 Aligning treatment expectancy with treatment selection has been shown to improve treatment outcomes.3

Acupuncture and massage are non-pharmacologic modalities with increasing availability at comprehensive cancer centers and a growing evidence base for cancer pain management. Recent guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and Society of Integrative Oncology (SIO) recommend both acupuncture and massage for treating cancer-related pain.4 The views of Hispanic persons towards these modalities remain under-studied, highlighting a potential barrier to uptake in this population.

Using baseline data from two randomized clinical trials (RCTs), we assessed the treatment expectations and views towards integrative therapies for pain management among Hispanic individuals with cancer and survivors of cancer.

Methods

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

This study is a secondary analysis of baseline data from two RCTs. The Personalized Electroacupuncture vs Auricular Acupuncture Comparativeness Effectiveness (PEACE) trial was a three-arm, parallel-group RCT that compared electro-acupuncture versus auricular acupuncture to usual care for chronic musculoskeletal pain among English-speaking adult survivors of various cancer types. The Integrative Medicine for Pain in Patients with Advanced Cancer Trial (IMPACT) was a two-arm, parallel-group RCT that evaluated the comparativeness effectiveness of electroacupuncture versus massage therapy for pain in English- or Spanish-speaking adult patients living with advanced cancer. Both trials were conducted at the main urban campus of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and five regional suburban sites in New York and New Jersey. The IMPACT trial also enrolled participants at the Baptist Health Miami Cancer Institute. Recruitment strategies for both studies included a multi-pronged approach. First, institutional patient databases were queried to identify potential participants who fulfilled basic eligibility criteria, and recruitment letters were mailed to these identified individuals. Second, the research team presented the studies to clinicians who cared for the target populations and provided instructions on how to refer potential participants to the studies. Third, information about the studies was posted on ClinicalTrials.gov and public-facing institutional websites and presented at cancer support groups and patient advocacy organizations. Once interested and potentially eligible participants were identified or referred to the study, they met with a study clinician to confirm eligibility. Eligible patients then completed informed consent, followed by baseline assessments. Details of the study protocols have been published previously.5,6

The terms Hispanic, Latina/o, and Latinx define an ethnic population and are used interchangeably by the United States census. Other sources distinguish between terms, with Hispanic referring to persons whose ancestry includes a Spanish-speaking country and Latina/o or Latinx referring to people whose culture has ties to a Latin American country.7 The word Hispanic is used in this study as it was the self-defined term asked of participants in both RCTs.

Data Collection, Main Outcomes, and Measures

Socio-demographics, cancer history, and clinical characteristics were assessed at baseline. The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) was used to evaluate pain severity and interference. Participants also completed the Mao Expectancy of Treatment Effects (METE) instrument at baseline. The METE is a validated four-item scale that assesses expectation of outcome and benefit for various interventions.8 Participants were asked to rate from 1 to 5 their agreement with the following items for each integrative therapy being studied in the trial (e.g., electroacupuncture, auricular acupuncture, and massage): my pain will improve a lot; I will be able to cope with my pain better; the symptoms of my pain will disappear; my energy level will increase. The METE scale ranges from 4 through 20, with higher scores indicating greater expectancy of treatment benefit.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were presented as means and percentages. Baseline characteristics were compared between Hispanic and NHW participants by two-sample t-test and Pearson’s chi-squared test. A two-sample t-test of mean baseline METE scores for Hispanic vs. NHW participants was administered for each integrative modality. PEACE and IMPACT baseline datasets were pooled to conduct a multivariate linear regression, with Hispanic ethnicity as the independent variable and mean METE score for combined integrative modalities being the dependent variable. Covariates included race (non-white vs. white), education (no college education vs. college education or higher), gender (female vs. male) and age (continuous variable).

Results

Compared to NHW counterparts, Hispanic cancer survivors reported greater pain severity. Similarly, Hispanic patients living with advanced cancer reported greater pain severity and pain-related interference. Other participant characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics for PEACE and IMPACT Randomized Clinical Trials.

| PEACE | (Survivors of cancer) | Ethnicity | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanic (n=35) | Non-Hispanic (n=316) | |||

| Mean age (SD), years | 60.02 (11.75) | 61.95 (12.75) | 0.396 | |

| Gender (%) | 0.518 | |||

| Male | 9 (25.7%) | 98 (31.0%) | ||

| Female | 26 (74.3%) | 218 (69.0%) | ||

| Race (%) | <0.001 | |||

| White | 18 (51.4%) | 248 (78.5%) | ||

| Non-white | 17 (48.6%) | 68 (21.5%) | ||

| Education (%) | 0.024 | |||

| College education or higher | 20 (57.1%) | 237 (75.0%) | ||

| High school education or less | 15 (42.9%) | 79 (25.0%) | ||

| Site of primary tumor (%) | 0.932 | |||

| Breast | 18 (51.4%) | 142 (44.9%) | ||

| Prostate | 2 (5.7%) | 37 (11.7%) | ||

| GI/Colorectal | 2 (5.7%) | 13 (4.1%) | ||

| Hematologic | 5 (14.3%) | 45 (14.2%) | ||

| Melanoma | 1 (2.9%) | 16 (5.1%) | ||

| Lung | 1 (2.9%) | 11 (3.5%) | ||

| GU | 6 (17.4%) | 52 (16.5%) | ||

| Mean BPI severity (SD) | 5.88 (1.62) | 5.16 (1.71) | 0.018 | |

| Mean BPI interference (SD) | 5.46 (1.97) | 4.93 (2.34) | 0.190 | |

| IMPACT | (Persons with advanced cancer) | Ethnicity | p | |

| Hispanic (n=46) | Non-Hispanic (n=247) | |||

| Mean age (SD), years | 59.96 (13.44) | 52.61 (16.00) | 0.001 | |

| Gender (%) | 0.053 | |||

| Male | 9 (19.6%) | 84 (34.0%) | ||

| Female | 37 (80.4%) | 163 (66.0%) | ||

| Race (%) | 0.001 | |||

| White | 25 (54.3%) | 192 (77.7%) | ||

| Non-white | 21 (45.7%) | 55 (22.3%) | ||

| Education (%) | 0.029 | |||

| College education or higher | 25 (54.3%) | 174 (68.2%) | ||

| High school education or less | 21 (45.7%) | 72 (31.9%) | ||

| Site of primary tumor (%) | 0.150 | |||

| Breast | 15 (32.6%) | 44 (17.8%) | ||

| Prostate | 1 (2.2%) | 27 (10.9%) | ||

| GI/Colorectal | 6 (13.0%) | 29 (11.7%) | ||

| Hematologic | 8 (17.4%) | 55 (22.3%) | ||

| Lung | 5 (10.9%) | 23 (9.3%) | ||

| Other | 5 (10.9%) | 15 (9.1%) | ||

| Gynecologic | 4 (8.7%) | 39 (15.8%) | ||

| Head/Neck | 2 (4.35%) | 15 (6.1%) | ||

| Mean BPI severity (SD) | 5.93 (1.46) | 5.02 (1.70) | 0.001 | |

| Mean BPI interference (SD) | 5.44 (2.03) | 4.63 (2.19) | 0.021 | |

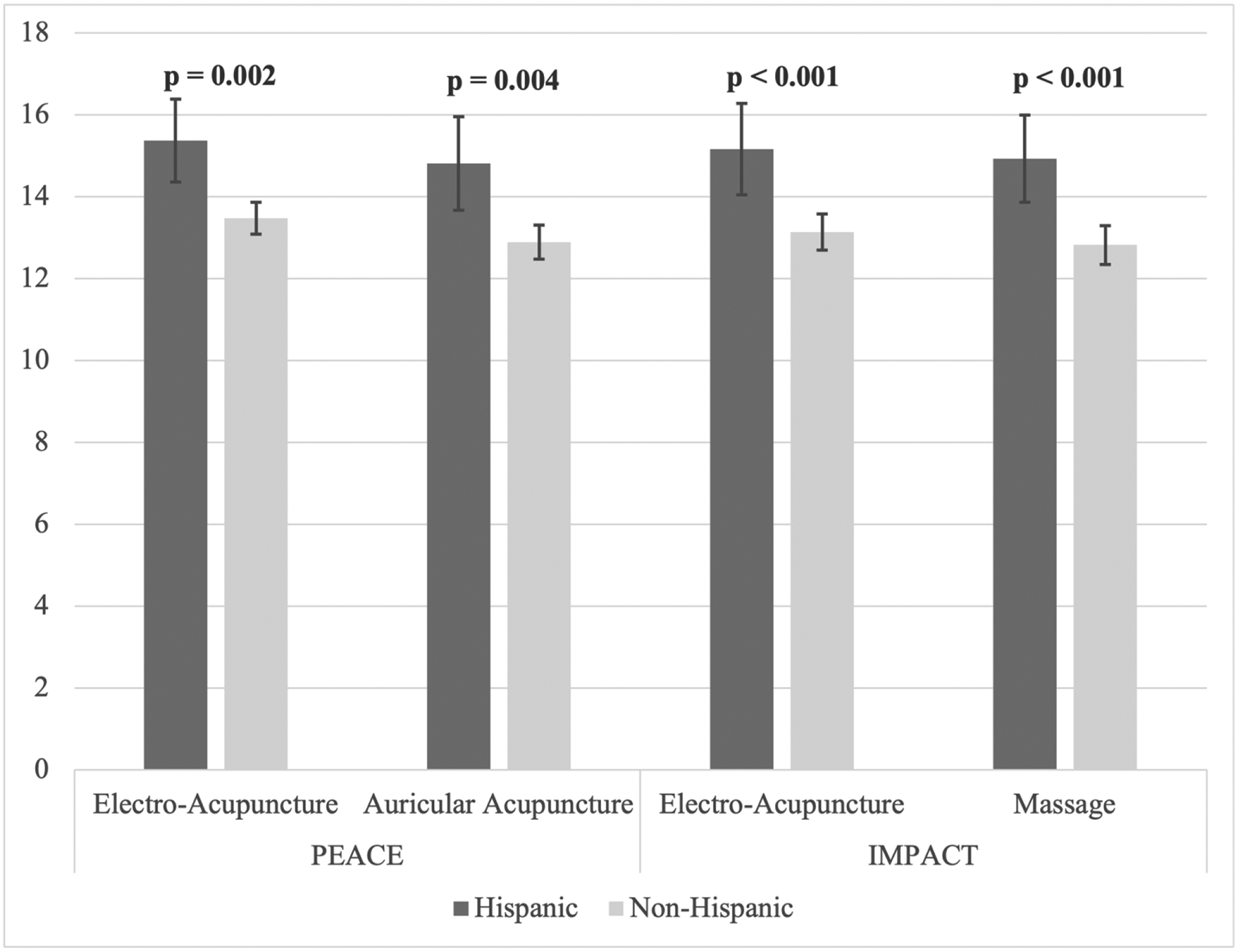

Hispanic cancer patients and survivors reported higher METE scores for electro-acupuncture, auricular acupuncture, and massage therapy, relative the NHW counterparts (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

METE Scores for Each Integrative Pain Modality by Ethnicity

(Created in Microsoft Excel)

Hispanic ethnicity remained significantly associated with higher METE scores after adjusting for age, gender, race, and education (Table 2). Non-white race, no college education, and female gender were also associated with higher METE scores.

Table 2.

Multivariate Linear Regression of Combined METE Scores for All Integrative Modalities

| Characteristic | Coefficient (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Hispanic ethnicity (vs. non-Hispanic) | 1.47 (0.67–2.27) | <0.001 |

| Non-white race (vs. white) | 1.04 (0.42–1.65) | 0.001 |

| No college education (vs. college and above) | 1.16 (0.59–1.74) | <0.001 |

| Female gender (vs. male) | 0.94 (0.38–1.50) | 0.001 |

| Age | 0.01 (−0.01–0.03) | 0.311 |

Discussion

In this exploratory subgroup analysis of baseline data from two RCTs, Hispanic ethnicity was associated with greater expectation of benefit from acupuncture and massage, even after adjusting for other sociodemographic covariates. Both modalities are recommended for cancer pain management in a recently published SIO-ASCO guideline.4 Our findings suggest that these evidence-based therapies were viewed favorably among Hispanic study participants and can help inform more effective shared decision-making about pain care approaches. Treatment barriers related to patients, clinicians, and health systems remain substantial and need to be addressed to promote equitable pain management.

Traditional non-pharmacologic therapies are widely used to treat pain among some Hispanic households and encompass a multitude of healing practices, with remedies made both in the home and by traditional healers.2 Acupuncture and massage may offer similarities to trusted forms of pain management used by Hispanic cancer survivors or persons living with cancer. Physical touch may be a more acceptable, and even integral, component of interpersonal connection in some Hispanic cultures, potentially contributing to greater acceptability of therapies that emphasize touch, including massage and acupuncture.9

In addition to Hispanic ethnicity, non-white race, no college education, and female gender were also found to be significantly associated with greater expectation of benefit from integrative pain management modalities. Despite their positive expectancy towards integrative therapies, individuals with minoritized backgrounds and lower educational attainment use these modalities at lower rates, reflecting underlying inequities in access to integrative therapies that remain unaddressed.10

First, one study limitation is that Hispanic participants made up approximately 10% of total participants in the RCTs and all Hispanic participants reported English as their preferred language. Given that the geographic origins and cultural practices of the U.S. Hispanic population are heterogeneous, larger sample sizes, more detailed demographic reporting, and greater inclusion of non-English-speaking individuals are needed to capture these cultural variations. Further assessment of migration history and cultural background is integral to understanding the views of diverse Hispanic communities. Second, the analyses were limited to baseline data and do not capture changes in beliefs over time or after the treatment experience. Additional research is necessary to investigate the association between expectation of benefit and response to treatment from integrative therapies. Third, this study also lacked information on participants’ prior experience with integrative pain therapies. Participants who choose to enroll in clinical trials are likely to have higher treatment expectations than the general population, so findings may not fully represent all Hispanic populations.8 Nevertheless, this study suggests that Hispanic individuals are open to participating in clinical trials, and greater efforts should be made to promote more diverse representation in future studies. Lastly, the clinical trials recruited from academic medical centers with urban and suburban sites. Future research should also recruit from community medical centers, particularly in rural and underserved settings, to enhance generalizability of these findings.

New Contributions to the Literature

Pain management should be informed by a shared decision-making approach that aligns treatment expectancy with treatment selections to optimize outcomes.3 This study supports a higher expectation of benefit from acupuncture and massage among Hispanic cancer patients and survivors with musculoskeletal or generalized pain, relative to their non-Hispanic counterparts, highlighting the potential role for integrative therapies in addressing pain disparities. Future research should focus on the dissemination and implementation of these evidence-based therapies to promote equitable pain management in Hispanic communities affected by cancer.

References

- 1.Samuel CA, Mbah OM, Elkins W, et al. Calidad de Vida: a systematic review of quality of life in Latino cancer survivors in the USA. Qual Life Res. 2020;29(10):2615–2630. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02527-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torres CA, Thorn BE, Kapoor S, DeMonte C. An Examination of Cultural Values and Pain Management in Foreign-Born Spanish-Speaking Hispanics Seeking Care at a Federally Qualified Health Center. Pain Med. 2017;18(11):2058–2069. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnw315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keefe JR, Amsterdam J, Li QS, Soeller I, DeRubeis R, Mao JJ. Specific expectancies are associated with symptomatic outcomes and side effect burden in a trial of chamomile extract for Generalized Anxiety Disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;84:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.09.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mao JJ, Ismaila N, Bao T, et al. Integrative Medicine for Pain Management in Oncology: Society for Integrative Oncology-ASCO Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2022. Dec 1;40(34):3998–4024. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.01357. Epub 2022 Sep 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mao JJ, Liou KT, Baser RE, et al. Effectiveness of Electroacupuncture or Auricular Acupuncture vs Usual Care for Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain Among Cancer Survivors: The PEACE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(5):720–727. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.0310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romero SAD, Emard N, Baser RE, et al. Acupuncture versus massage for pain in patients living with advanced cancer: a protocol for the IMPACT randomised clinical trial. BMJ Open. 2022;12(9):e058281. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-058281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopez MH, Krogstad JM, Passel JS. Who is Hispanic? Pew Research Center. Accessed March 28, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/09/15/who-is-hispanic/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mao JJ, Xie SX, Bowman MA. Uncovering the Expectancy Effect: The Validation of the Acupuncture Expectancy Scale. Altern Ther Health Med. 2010;16(6):22–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burleson MH, Roberts NA, Coon DW, Soto JA. Perceived cultural acceptability and comfort with affectionate touch: Differences between Mexican Americans and European Americans. J Soc Pers Relatsh. 2019;36(3):1000–1022. doi: 10.1177/0265407517750005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM, Nahin RL. Trends in the Use of Complementary Health Approaches Among Adults: United States, 2002–2012. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2015;(79):1–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]