Abstract

Migraine is a genetically influenced complex neurological disease characterized by attacks of moderate to severe headaches and a variety of concomitant symptoms. Migraine disease can significantly impact individuals’ daily activities and quality of life. It is a major cause of disability and loss of productivity, which can be exacerbated by migraine-related stigma. Recent advances in migraine treatment and ongoing research may offer additional options for patients; however, treatment barriers still exist, resulting in underdiagnosis and undertreatment of migraine disease, especially in some minority and vulnerable groups. Primary care and emergency department providers are often the first point of contact for patients with migraine disease, so there is opportunity for them to assist in addressing these barriers, particularly with strategies to make care more patient-centered. Managed care organizations can also play a role in overcoming these barriers and supporting equitable access.

Plain language summary

Migraine is a disorder of the brain and is influenced by a person’s genetics. It causes attacks of moderate to severe headaches and other symptoms. Migraine disease can be very disruptive to people’s lives both at home and at work. New migraine treatments have become available, and others are being studied, but some people still have difficulty getting treatment. Front-line providers and managed care organizations can help overcome some of these difficulties.

Implications for managed care pharmacy

Migraine is a genetically influenced complex neurological disease that can significantly impact individuals’ daily activities and quality of life. It is a major cause of disability and loss of productivity. Managed care organizations can play a role in overcoming barriers to diagnosis and appropriate treatment of migraine disease and help to support equitable access.

Overview of Migraine Disease

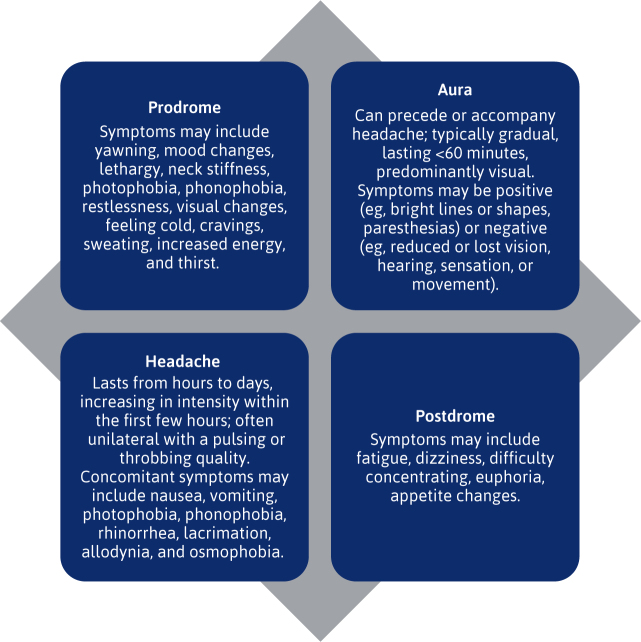

Migraine is a genetically influenced complex neurological disorder. It is characterized by attacks of moderate to severe headaches and a variety of concomitant symptoms including but not limited to nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia, and osmophobia. 1 The migraine headache phase may be preceded by a prodrome phase and followed by a postdrome phase. Aura may precede or accompany the headache phase (Figure 1). 1

FIGURE 1.

Phases of Migraine Attack 1 , 61 , 62

The migraine headache phase may be preceded by a prodrome phase and followed by a postdrome phase. Aura, when present, may precede or accompany the headache phase.

Although the pathophysiology of migraine disease is not completely understood, the trigeminovascular system, which relays head pain signals to the brain, plays a key role. 1 Activated trigeminovascular neurons relay the migraine pain signal from the periphery to the central nervous system, and repeated activation over time results in a state of nervous system hypersensitivity and sustained pain. 1

Several molecules have been associated with the pathophysiology of migraine disease and represent both current and future pharmacologic treatment targets. 1 , 2 For example, activation of serotonin receptors causes vasoconstriction and inhibition of peptides such as calcitonin gene–related peptide (CGRP), which results in pain relief. 3 Additionally, pituitary adenylate cyclase–activating polypeptide (PACAP) is being studied as a potential therapy based on proposed mechanisms including vasodilatation, effects on the parasympathetic nervous system, mast cell degranulation, activation of sensory afferents, and central effects. 1 , 2 , 4

DIAGNOSIS

Migraine is a primary headache disorder that includes migraine with and without aura, and chronic migraine, which may also be with or without aura. 5 The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3), developed by the International Headache Society, provides diagnostic criteria for migraine disease and other headache disorders. Criteria specific to migraine diagnoses are listed in Table 1. Also listed in Table 1 are the ICHD-3 diagnostic criteria for migraine-related conditions including probable migraine and medication overuse headache, which can result from overuse of acute treatment for migraine attacks. 5

TABLE 1.

ICHD-3 Diagnostic Criteria 5

| Diagnosis | ICHD-3 criteria |

|---|---|

| Migraine without aura |

|

| Migraine with aura |

|

| Chronic migraine |

|

| Probable migraine |

|

| Medication overuse headache |

|

Adapted from the International Headache Society ICHD-3.

d = day; h = hour; ICHD = International Classification of Headache Disorders; mo = month; NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Although not included in the ICHD-3 criteria, the term episodic migraine is also commonly used to differentiate from chronic migraine. 6 Episodic migraine describes fewer than 15 headache days per month, some of which are migraine days, whereas chronic migraine is 15 or more headache days per month, at least 8 of which are migraine days. 5 , 6

CONDITION PROGRESSION

Migraine attacks in some patients may increase in frequency over time from episodic to chronic. 7 , 8 This process is referred to as transformation or chronification. Although the exact mechanisms underlying this process are not fully understood, numerous risk factors have been identified. These include disease characteristics (eg, headache frequency, frequent and persistent nausea, presence of cutaneous allodynia), treatment-related factors (eg, suboptimal acute treatment, acute medication overuse, barbiturate-containing or opioid medications), comorbidities (eg, psychiatric disorders, metabolism-related conditions, traumatic head injury), lifestyle factors (eg, frequent exposure to stressful events, adverse childhood experiences), and demographic factors (eg, being female, hormonal status). 7 , 8 The actions with the best evidence for protection against chronification are to optimize acute and preventive medications. 8

CONDITION BURDEN

Approximately 2.81 billion individuals globally had migraine disease or tension-type headache in 2021, with female individuals aged 15 to 49 years being the most affected. 9 The global burden of migraine disease increased from 1990 to 2021 based on both prevalence (increased by 1.6% to a prevalence of 14,246.5/100,000) and years lived with disability (increased by 0.6% to 532.7/100,000 years lived with disability). 10 Among disorders affecting the nervous system in 2021, it was the third highest globally and the second highest in North America based on disability-adjusted life-years. In the same year, it was the leading cause of nervous system disability-adjusted life-years for children and adolescents aged 5 to 19 years (380.0/100,000) and the second highest for adults aged 20 to 59 years (750.8/100,000). It is significantly more prevalent in female individuals, with a female to male ratio in 2021 of 1.69. 10

Patients with migraine disease experience significant burden during migraine attacks, with common symptoms including head pain, aura, affected vision, photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and cognitive effects. 1 , 11 They also experience burden due to treatment side effects and between attacks during the interictal phase. 11 Interictal burden includes decreased health-related quality of life, lifestyle modifications in anticipation of an attack, and impacts on work, career, daily activities, and relationships. Emotional impacts such as anger, depression, anxiety, and hopelessness are also common. Preventive treatments improve health-related quality of life and functioning for many patients, but breakthrough attacks are common, and with some treatments, patients have reported varying efficacy between doses. 11

Like other invisible or concealable conditions, migraine disease is stigmatized, and migraine disease–related stigma is associated with more disability, greater interictal burden, and reduced quality of life. 12 Stigma may result, for example, when individuals appear well between attacks. They are often expected to function normally and, if unable, may be viewed as avoiding responsibility or participation because of laziness or poor work ethic. Additionally, instead of recognizing migraine as a neurological disorder, it gets incorrectly attributed to factors like stress, mood disorders, poor sleep, diet, and hydration. This may lead to patients blaming themselves or being blamed by others for their condition. There is also evidence that migraine is not considered a significant neurological disorder among physicians, which could lead them to devalue the treatment needs of patients with migraine disease. 12 Minimal headache education in medical school for many physicians may further compound this bias. 13

MANAGEMENT

Management of migraine disease is focused on alleviating the symptoms of acute attacks, reducing the frequency and severity of attacks, and improving individual quality of life. 1 , 14 Treatment plans for migraine disease should include acute treatment for all patients and preventive treatment when indicated. 14 Patients also benefit from discussing optimization of lifestyle, maintaining a headache diary, and counseling on available nonpharmacologic treatments. 14

Acute Pharmacologic Treatment.

All patients should be offered acute treatment for migraine disease and education to decrease their risk of medication overuse headache. 14 Principles of acute pharmacologic treatment selection and acute pharmacologic treatments with established and probable efficacy in migraine disease as listed by the American Headache Society (AHS) are detailed in Table 2. These include but are not limited to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen and caffeine combinations medications, ergot derivatives, selective serotonin 1F receptor agonists (ditans), selective serotonin 1B/1D receptor agonists (triptans), and small molecule CGRP receptor antagonists (gepants). Peripheral nerve block may also be used particularly when patients require rescue treatment when initial acute medication does not provide pain relief. 14

TABLE 2.

| Acute | Preventive |

|---|---|

| Principles of treatment selection | |

Use evidence-based treatments

Assess benefit vs risk Consider a self-administered rescue treatment Avoid medication overuse Criteria for initiating acute treatment with gepants, ditans, or neuromodulatory devices:

|

Use evidence-based treatments Start low and titrate When reaching a therapeutic dose, give an adequate trial of at least 3 mo Establish realistic expectations Consider factors to optimize treatment and maximize adherence, such as:

|

| Pharmacologic treatments with established efficacy in migraine disease | |

Nonspecific to migraine disease

Specific to migraine disease

|

CGRP receptor antagonists

Candesartan Divalproex sodium Frovatriptan Metoprolol OnabotulinumtoxinA Propranolol Timolol Topiramate Valproate sodium |

| Pharmacologic treatments with probable efficacy in migraine disease | |

Nonspecific to migraine disease

Specific to migraine disease

|

Amitriptyline Atenolol Lisinopril Memantine Nadolol OnabotulinumtoxinA + CGRP mAb Venlafaxine |

Adapted from The American Headache Society Consensus Statement: Update on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice.

CGRP = calcitonin gene–related peptide; IM = intramuscular; IV = intravenous; mAb = monoclonal antibody; mo = month; NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

It should be noted that gepants are not associated with medication overuse headache. 14 In contrast, neither butalbital nor opioids are recommended in the treatment of migraine disease except as a last resort because of significant risk of medication overuse headache. 14 , 15

The goals of acute treatment are to (1) achieve rapid and consistent freedom from pain and associated symptoms, (2) restore ability to function, (3) minimize need for repeat dosing or rescue medications, (4) avoid or minimize adverse events, (5) optimize self-care and reduce health care resource utilization (eg, emergency department [ED] visits, diagnostic imaging, outpatient services), and (6) maintain affordability to patients. 14

Patient-oriented, validated outcome measures of acute treatment success can help determine whether patients have experienced a meaningful response and identify the need for adjustments to a treatment plan. 14 The AHS recommends several tools of varying lengths, with questions evaluating, for example, patient satisfaction with their acute treatment based on efficacy (eg, 2-hour pain freedom, pain relief), function, ease of use, cost, and tolerability. 14 , 16 – 18

Preventive Pharmacologic Treatment.

Preventive treatment is indicated for frequent attacks, severe disability despite acute treatment, acute treatment contraindication or side effects, medication overuse headache risk, or patient preference. 14 Principles of preventive pharmacologic treatment selection and preventive pharmacologic treatments with established and probable efficacy in migraine disease as listed by the AHS are detailed in Table 2. These include but are not limited to CGRP receptor antagonist monoclonal antibodies (CGRP mAbs), the gepants atogepant and rimegepant, candesartan, divalproex sodium, metoprolol, onabotulinumtoxinA, propranolol, timolol, topiramate, and valproate sodium. 14

The goals of preventive treatment are to (1) reduce attack frequency, severity, and duration, (2) improve function and reduce disability, (3) improve responsiveness to and avoid escalation in use of acute treatment, (4) reduce reliance on poorly tolerated, ineffective, or unwanted acute treatments, (5) improve health-related quality of life, (6) reduce headache-related distress and psychological symptoms, (7) enable patients to manage their own disease to enhance a sense of personal control, and (8) reduce overall cost associated with migraine disease treatment. 14

Determining the efficacy and tolerability of preventive treatment should be patient driven. 14 Outcome measures that may be important to patients include a reduction in days with headache or migraine (eg, 50% reduction in days per month with headache or migraine), a significant decrease in migraine attack severity and duration, improved response to acute treatment, reduction in migraine-related disability and improvement in functioning, and improvement in health-related quality of life and reduction in psychological distress due to migraine. 14

Nonpharmacologic Treatment

Lifestyle.

The mnemonic SEEDS (sleep, exercise, eat, diary, and stress) can assist with lifestyle management for patients with migraine disease. 19 It includes standard sleep hygiene to maximize sleep quantity and quality, exercise for 30 to 60 minutes 3 to 5 times a week, regular healthy meals and adequate hydration, and low or stable caffeine intake. Additionally, it emphasizes patients should keep a migraine attack diary to establish a baseline pattern, assess response to treatment, and monitor analgesia. The importance of coping with condition-related and other stress is also highlighted and can be done, for example, through cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness, relaxation, biofeedback, and developing health care provider (HCP)–patient trust to minimize anxiety. 19

Neuromodulation.

All patients with a confirmed diagnosis of migraine disease may be offered treatment with a neuromodulatory device, which modulates pain mechanisms involved in headache by stimulating the nervous system with an electric current or a magnetic field. 14 , 20 They can be used for both acute and preventive treatment alone or in combination with pharmacologic therapy. Neuromodulatory devices can especially be considered in patients who prefer to avoid medication; those with a history of poor medication tolerability, significant medication contraindications, or inadequate response to medication; those at risk of medication overuse headache or migraine chronification; and those who are indicated for preventive treatment. 14 , 21

Biobehavioral therapies.

Cognitive behavioral therapy, biofeedback, and relaxation therapies have good evidence for their use as preventive therapies. 14 Limited evidence and clinical experience also support their use as acute therapies. Additionally, mindfulness-based therapies and acceptance and commitment therapy are active topics of research and have a growing evidence base for use in migraine disease. 14

Complementary/alternative therapies.

Physical therapy, massage therapy, and acupuncture may be used as complementary or alternative therapies in migraine disease. 21 Meta-analyses of evidence for acupuncture, for example, indicates reduction in the frequency of migraine attacks and is less likely than medication to result in adverse effects. 21

Dietary/herbal supplementation.

Dietary and herbal supplements can be used as part of a migraine disease treatment plan. Magnesium, Coenzyme Q10, and riboflavin have evidence for their use in migraine disease. 21 , 22

EMERGING TREATMENTS

The discussion below provides brief summaries of selected treatments for migraine disease that are in advanced stages of development.

Lu AG09222.

Lu AG09222 is a monoclonal antibody, which targets PACAP and inhibits its effects. 2 In a phase 2, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, the safety and efficacy of Lu AG09222 were evaluated in a total of 237 participants (Lu AG09222 750 mg n = 97, Lu AG09222 100 mg n = 46, placebo n = 94). 23 The primary endpoint was the mean change from baseline in the number of migraine days per month in the Lu AG09222 750 mg group as compared with the placebo group. The mean number of baseline migraine days per month was 16.7, and the mean change from baseline was −6.2 days in the Lu AG09222 750 mg group and −4.2 days in the placebo group (difference, −2.0 days; 95% CI, −3.8 to −0.3; P = 0.02). Adverse events with a higher incidence in the Lu AG09222 750 mg group than in the placebo group during the 12-week observation period included COVID-19, nasopharyngitis, and fatigue. 23

Digital Therapeutics.

Digital therapeutics used in migraine disease are primarily smartphone applications. 24 These may, for instance, link patients with headache experts online to diagnose migraine disease or provide treatment options, offer digital diaries and other tools to diagnose and track migraine attacks, and support nonpharmacologic treatment including providing digital cognitive behavioral therapy. The evidence for digital therapeutics is still evolving, and much of it is focused on the use of digital diaries. 24 However, one published protocol describes a new study to assess the efficacy of several interdisciplinary digital interventions compared with conventional treatment options. 25 Digital interventions will include headache nurse counseling, cognitive behavioral therapy, and physical therapy in addition to a headache diary. The primary outcome measure will be the number of headache days at 3 months compared with baseline, with secondary objectives of evaluating components such as adherence, credibility, clinical contact, and cost-effectiveness in comparison with conventional treatment delivery. 25

Optimal Management in Various Practice Settings

Primary barriers to optimal management in migraine disease include patient reluctance to initiate a discussion about their migraine disease symptoms with their HCP, delays in receiving a correct diagnosis of migraine disease, and being offered a minimally appropriate standard-of-care treatment once a diagnosis is established. 26 , 27 Because primary care providers (PCPs) and ED providers are often the first point of contact for patients with migraine disease within the health care system, there is opportunity for them to assist in addressing these barriers. 27 For instance, acknowledging that migraine disease is underdiagnosed, especially among women, and proactively asking patients about headaches or number of days they are headache-free. Also, using empowering, nonstigmatizing language such as migraine attacks vs migraines, which helps to acknowledge there is a wide range of symptoms other than head pain that may be experienced during an attack and may encourage patients to discuss them. 27

Additionally, owing to the limited number of headache specialists, it is important for these front-line HCPs to be comfortable treating migraine disease as well as knowing when to refer patients to another HCP. 27 Knowing how to recognize a likely patient with migraine disease (ie, if the patient mentions head pain plus 2 of photophobia, nausea, or inability to focus) is a key first step. 27 , 28 Once identified, a trial of at least 2 acute migraine disease treatments and 2 preventive migraine disease treatments is suggested before referring the patient to a neurologist or a headache specialist. 27

However, there are differences in barriers to diagnosis and treatment options among PCPs. 29 Lack of diagnosis may be due to factors such as unclear patient histories, prioritizing other comorbidities, insufficient time, or lack of education. 13 , 29 Diagnosis and treatment may also be impacted by length of time in clinical practice. 29 It is important, therefore, that training programs, health systems, and professional societies and others that provide clinician continuing education contribute to increasing familiarity with migraine disease and its treatments and decreasing barriers to migraine care. 13 , 29

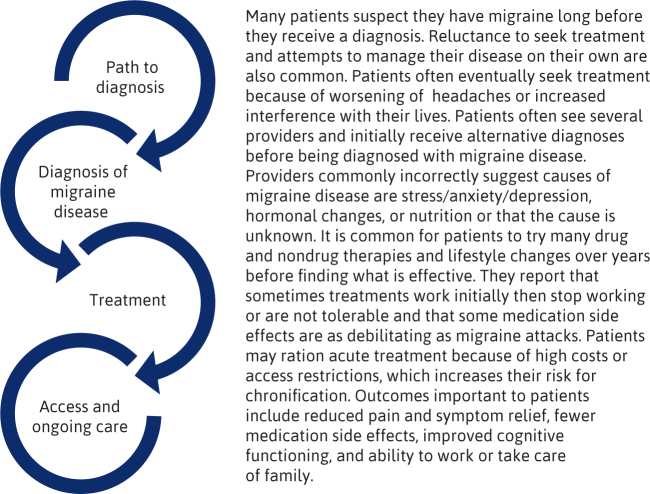

A more detailed description regarding the patient journey with migraine disease and how these barriers may affect it can be found in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Health Disparities Among a Diverse Migraine Disease Population

Disparities exist in the diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes of underserved patients with migraine disease and other headache disorders. 30 These disparities are based on race, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and geography, among other factors. For example, although the prevalence of severe headache and migraine disease is reportedly similar among Black, Hispanic, and White individuals in the United States, Black and Hispanic patients are 25% and 50% less likely, respectively, to receive a migraine disease diagnosis compared with White patients, and Black men receive the least care for migraine disease. Additionally, Black patients report more headache days per month, higher pain intensity, and poorer quality of life than White patients, indicating potentially more severe disease or a greater extent of undertreatment, or both. 30 Undertreatment may be at least in part due to a persistent incorrect stereotype that Black patients are more pain tolerant. 30 , 31

There are few data on potential disparities among native/indigenous people in America despite them having the highest prevalence of migraine (19.2%); however, they are more likely to experience allodynia, which is associated with poor treatment outcomes. 30 There are also limited data on potential disparities and the experience of migraine among Asian Americans. 30

Among sexual minority groups, the prevalence of migraine disease is higher compared with those who are heterosexual, which may in part be due to sexual minority stress consisting of prejudice, stigma, and discrimination and may also be influenced by gender-affirming hormone therapy. 32 , 33 Although data specific to biases in migraine disease or other headache disorders are lacking, biases among health care professions students and HCPs toward sexual and gender minority patients have been documented in the health care literature. 30 These patients also report discrimination from HCPs and are more likely to delay or avoid necessary medical treatment compared with nonminority patients. 30

Lower-income groups have a 60% higher rate of migraine disease compared with higher-income groups, and they are less likely to receive acute migraine disease treatment, putting them at higher risk for migraine disease progression. 30 It has been proposed that this disparity may be due to social selection, a situation in which individuals may be unable to perform their regular educational and occupational responsibilities, leading to a decline in social status because of migraine disease disability, or social causation, a situation in which low socioeconomic status is linked to increased stress, which causes an increased duration or incidence of disability. 30

Geographic disparities also exist, as the density of headache specialists is lower in rural states and there are limited or no training programs in some areas. 30 Additionally, social stigma and privacy concerns act as even greater barriers to health care access in rural communities where there is little anonymity. Transportation, travel time, longer wait times, and greater income loss because of additional time off work for health care visits also pose challenges for rural patients. Technology such as telehealth may provide a solution for some but can compound disparity for rural patients if they do not have access to sufficient technological infrastructure or knowledge, for example. 30

Fostering Patient-Centered Care

A primary need expressed by patients is to have their opinions heard, validated, and respected by their HCP because despite its significant associated disability, many patients feel they and migraine disease as a disorder are not taken seriously. 34 A more patient-centered approach can be achieved through HCP awareness of and work to mitigate their biases and, as previously discussed, through the use of empowering, nonjudgmental language. 27 , 34 Care can also be more patient-centered by using a shared decision-making process, which requires HCPs to have the most current knowledge regarding migraine disease and its treatment and to use it to discuss varying treatment characteristics and help patients weigh the pros and cons of each option. 34 Additionally, asking patients to keep a headache diary and reviewing it at each visit includes patients as active participants in their care and allows for improved monitoring of symptoms, function, and treatment effect. 19 , 27 , 34

Regarding treatments, patient preferences include nonpharmacologic options, long-lasting effect, high effectiveness, rapidity of action, lower cost and improved access, and having a self-management/self-delivery option. 34 Treatment outcomes important to patients include side effects, addiction potential, function, pain reoccurrence, and nonheadache symptoms. This highlights the value of HCPs being mindful of migraine symptoms beyond headache, such as aura, nausea/vomiting, photophobia, and phonophobia, and how migraine disease may affect functioning. 34 It also reinforces the AHS recommendation to use patient-oriented, validated tools to evaluate treatment effectiveness. 14 , 31

Managed Care Considerations in Migraine Disease

SUPPORTING EQUITABLE ACCESS TO CARE

Equity in access to migraine disease care can be supported clinically, in terms of clinician education and training, and by addressing systemic disparities in research. 30 Suggested clinical strategies include using telemedicine and encouraging migraine disease care in primary and secondary settings to mitigate geographic disparities and limited specialist availability, promoting screenings to determine and help address unmet needs, and proactively considering accessibility issues to optimize care once initiated. 30

Managed care organizations (MCOs) can play a role in these strategies, for example, by allowing coverage of telehealth visits in accordance with relevant laws, advocating for expansion of legislation related to telehealth, providing resources to their members to address challenges with use of technology, and ensuring the availability of translating services for telehealth visits on platforms they promote. 30 Additionally, they can continuously review and improve HCP networks when possible, and work with relevant stakeholders such as HCPs and employer groups, to increase migraine disease screenings and improve quality of care. 30

MCOs can also work with their HCP partners to provide education on migraine disease and its treatments when appropriate, and work with their drug development partners through education or joint forums like those facilitated by AMCP, for example, to improve representation of minority and vulnerable groups in research and evidence generation. 30

These considerations for supporting equitable access to care in migraine disease are listed in Table 3.

TABLE 3 .

| Focus | Considerations |

|---|---|

| Supporting equitable access to care |

|

| Managing treatments for migraine disease | Coverage policy—The coverage determination process should be clear and efficient. The following criteria elements may be considered:

Preferred medications/step therapy—Consider guideline recommendations such as from the American Headache Society and American College of Physicians. Quantity limits—Consider prescribing information maximum dosages and risks of medication overuse headache and chronification with acute treatments. Value-based arrangement—Consider outcomes-based contracts for newer or more costly medications to ensure cost-effective use. Nonpharmacologic treatments—Consider strategies to encourage appropriate use including coverage when applicable. |

MANAGING TREATMENTS FOR MIGRAINE DISEASE

In a 2020 review of the acute migraine disease treatments lasmiditan—a serotonin agonist—and the gepants, rimegepant and ubrogepant, the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) concluded that the evidence does not demonstrate superiority of these newer agents vs existing less-expensive treatment options (eg, triptans), nor does it show major differences in the safety and efficacy between rimegepant and ubrogepant. 35 As a result, in the final policy recommendations, they state it is reasonable for payers to develop coverage criteria based on clinical evidence, clinical practice guidelines, and input from clinical experts and patients for these therapies to ensure their prudent use. They also indicate it is reasonable for payers to prefer certain products, provided there is a path to appeal for coverage of nonpreferred products when clinically appropriate. 35 This might be in the case of triptan nonresponse, which reportedly occurs in approximately 30% of patients, or contraindications to triptans, for example. 14

Since this review, rimegepant has gained an indication for preventive treatment of episodic migraine, and the new gepant, zavegepant (intranasal spray), has been approved for the acute treatment of migraine attacks (details of all the most recently approved novel pharmacologic treatments in migraine disease can be found in Table 4). 36 , 37 MCOs should consider these and other ongoing developments along with the currently available clinical and value evidence in their management strategy for acute migraine disease treatments.

TABLE 4 .

| Product | Dosage form | Indications | Approval date |

|---|---|---|---|

| CGRP receptor antagonist monoclonal antibodies (CGRP mAbs) | |||

| Eptinezumab | Intravenous injection | Preventive treatment of migraine attacks in adults | February 2020 |

| Erenumab | Subcutaneous injection | Preventive treatment of migraine attacks in adults | May 2018 |

| Fremanezumab | Subcutaneous injection | Preventive treatment of migraine attacks in adults | September 2018 |

| Galcanezumab | Subcutaneous injection | Preventive treatment of migraine attacks in adults | September 2018 |

| Treatment of episodic cluster headache | June 2019 | ||

| Small molecule CGRP receptor antagonists (gepants) | |||

| Atogepant | Oral tablet | Preventive treatment of migraine attacks in adults | April 2023 |

| Rimegepant | Oral disintegrating tablet | Acute treatment of migraine attacks with/without aura | February 2020 |

| Preventive treatment of episodic migraine disease | May 2021 | ||

| Ubrogepant | Oral tablet | Acute treatment of migraine attacks with/without aura | December 2019 |

| Zavegepant | Nasal spray | Acute treatment of migraine attacks with/without aura | March 2023 |

| Selective serotonin 1F receptor agonists (ditans) | |||

| Lasmiditan | Oral tablet | Acute treatment of migraine attacks with/without aura | October 2019 |

CGRP = calcitonin gene–related peptide.

ICER also conducted a review of the preventive CGRP mAbs erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab in 2018, acknowledging their then-new mechanism of action and lack of long-term safety and efficacy data. 38 Like acute treatments, their recommendations for these medications stated it was reasonable for payers to implement coverage criteria to ensure prudent use and to prefer certain products, with nonpreferred products accessible by appeal. 38

Since this review, a more robust body of evidence for all CGRP receptor antagonists is available and the AHS has provided a consensus statement indicating that CGRP receptor antagonists may be a first-line option for preventive treatment of migraine disease. 39 This recommendation is based on their assessment that the efficacy and tolerability of CGRP receptor antagonists are equal to or greater than those of older first-line treatments and that serious adverse events with CGRP receptor antagonists are rare. 39

An even more recent comparative effectiveness analysis performed by the American College of Physicians, however, led to the recommendation that a trial of metoprolol, propranolol, valproate, venlafaxine, or amitriptyline is appropriate prior to initiation of a CGRP receptor antagonist. 40 Other groups encourage caution when using these results owing to limitations with the data used in the analysis. 41 For example, many of the studies use outdated methods and definitions of migraine and often included patients with mild disease. 41

Also since the ICER review, the CGRP mAb eptinezumab (intravenous injection) and the gepant atogepant (oral tablet) have been approved for the preventive treatment of migraine attacks (details of all the most recently approved novel pharmacologic treatments in migraine disease can be found in Table 4). 42 , 43 MCOs should consider these and other ongoing developments along with the currently available clinical and value evidence in their management strategy for preventive migraine disease treatments.

A detailed list of managed care considerations in migraine disease can be found in Table 3.

Conclusions

Migraine disease is a complex neurological condition with significant burden globally, as well as to individual patients. Recent advances in migraine disease treatment and ongoing research may offer additional options for patients; however, treatment barriers still exist and result in underdiagnosis and undertreatment of migraine disease, especially in some minority and vulnerable groups. There is opportunity for front-line providers and MCOs to address these barriers, particularly with strategies to make care more patient-centered, and to support equitable access.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author acknowledges Jennifer Robblee, MD, MSc, FRCPC, Kylie Gagan, RN, BSN, MHD, Brooke Whittington, PharmD, Jennifer L. Evans, PharmD, BCACP, C-TTS, and Brittany V. Henry, PharmD, MBA, for their technical editing of the manuscript. The author also acknowledges the Association of Migraine Disorders.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pescador Ruschel MA, De Jesus O. Migraine Headache. Updated July 5, 2024. In: StatPearls. [Internet] StatPearls Publishing; 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560787/ [PubMed]

- 2. Chiang CC, Porreca F, Robertson CE, Dodick DW. Potential treatment targets for migraine: Emerging options and future prospects. Lancet Neurol . 2024;23(3):313-24. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(24)00003-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Khan J, Asoom LIA, Sunni AA, et al. Genetics, pathophysiology, diagnosis, treatment, management, and prevention of migraine. Biomed Pharmacother . 2021;139:111557. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Guo S, Jansen-Olesen I, Olesen J, Christensen SL. Role of PACAP in migraine: An alternative to CGRP? Neurobiol Dis . 2023;176:105946. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2022.105946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1-211. doi: 10.1177/0333102417738202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goadsby PJ, Evers S. International Classification of Headache Disorders - ICHD-4 alpha . Cephalalgia . 2020;40(9):887-8. doi: 10.1177/0333102420919098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Torres-Ferrús M, Ursitti F, Alpuente A, et al. ; School of Advanced Studies of European Headache Federation (EHF-SAS). From transformation to chronification of migraine: pathophysiological and clinical aspects. J Headache Pain . 2020;21(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01111-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lipton RB, Buse DC, Nahas SJ, et al. Risk factors for migraine disease progression: A narrative review for a patient-centered approach. J Neurol . 2023;270(12):5692-710. doi: 10.1007/s00415-023-11880-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, Aali A, et al. ; GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2024;403(10440):2133-61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00757-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Steinmetz JD, Seeher KM, Schiess N, et al. ; GBD 2021 Nervous System Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of disorders affecting the nervous system, 1990-2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Neurol. 2024;23(4):344-81. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(24)00038-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lo SH, Gallop K, Smith T, et al. Real-World experience of interictal burden and treatment in migraine: A qualitative interview study. J Headache Pain . 2022;23(1):65. doi: 10.1186/s10194-022-01429-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shapiro RE, Nicholson RA, Seng EK, et al. Migraine-related stigma and its relationship to disability, interictal burden, and quality of life: Results of the OVERCOME (US) Study. Neurology . 2024;102(3):e208074. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000208074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pace A, Orr SL, Rosen NL, Safdieh JE, Cruz GB, Sprouse-Blum AS. The current state of headache medicine education in the United States and Canada: An observational, survey-based study of neurology clerkship directors and curriculum deans. Headache . 2021;61(6):854-62. doi: 10.1111/head.14134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ailani J, Burch RC, Robbins MS; Board of Directors of the American Headache Society. The American Headache Society Consensus Statement: Update on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache . 2021;61(7):1021-39. doi: 10.1111/head.14153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Langer-Gould AM, Anderson WE, Armstrong MJ, et al. The American Academy of Neurology’s top five choosing wisely recommendations. Neurology . 2013;81(11):1004-11. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828aab14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lipton RB, Kolodner K, Bigal ME, et al. Validity and reliability of the Migraine-Treatment Optimization Questionnaire. Cephalalgia . 2009;29(7):751-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01786.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kilminster SG, Dowson AJ, Tepper SJ, Baos V, Baudet F, D’Amico D. Reliability, validity, and clinical utility of the Migraine-ACT questionnaire. Headache . 2006;46(4):553-62. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00403.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kimel M, Hsieh R, McCormack J, Burch SP, Revicki DA. Validation of the revised Patient Perception of Migraine Questionnaire (PPMQ-R): Measuring satisfaction with acute migraine treatment in clinical trials. Cephalalgia . 2008;28(5):510-23. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01524.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Robblee J, Starling AJ. SEEDS for success: Lifestyle management in migraine. Cleve Clin J Med . 2019;86(11):741-9. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.86a.19009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. American Migraine Foundation . Non-Invasive Neuromodulation Devices. Published December 14, 2017. Accessed April 3, 2025. https://americanmigrainefoundation.org/resource-library/non-invasive-neuromodulation-devices/

- 21. Song X, Zhu Q, Su L, et al. New perspectives on migraine treatment: a review of the mechanisms and effects of complementary and alternative therapies. Front Neurol . 2024;15:1372509. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2024.1372509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tepper SJ, Tepper K. Nutraceuticals and Headache 2024: Riboflavin, Coenzyme Q10, Feverfew, Magnesium, Melatonin, and Butterbur. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2025;29(1):33. doi: 10.1007/s11916-025-01358-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ashina M, Phul R, Khodaie M, Löf E, Florea I. A monoclonal antibody to PACAP for migraine prevention. N Engl J Med . 2024;391(9):800-9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2314577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen X, Luo Y. Digital therapeutics in migraine management: A novel treatment option in the COVID-19 era. J Pain Res . 2023;16:111-7. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S387548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Niiberg-Pikksööt T, Laas K, Aluoja A, Braschinsky M. Implementing a digital solution for patients with migraine-Developing a methodology for comparing digitally delivered treatment with conventional treatment: A study protocol. PLOS Digit Health . 2024;3(2):e0000295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pdig.0000295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lanteri-Minet M, Leroux E, Katsarava Z, et al. Characterizing barriers to care in migraine: Multicountry results from the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes - International (CaMEO-I) study. J Headache Pain . 2024;25(1):134. doi: 10.1186/s10194-024-01834-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dehlin J, Starling AJ. The Patient-Centered Visit & Shared Decision Making in the Management of Migraine. NeurologyLive. Published April 30, 2021. Accessed January 17, 2025. https://www.neurologylive.com/peers-perspectives/the-patient-centered-visit-shared-decision-making-in-the-management-of-migraine

- 28. Lipton RB, Dodick D, Sadovsky R, et al. ; ID Migraine validation study. A self-administered screener for migraine in primary care: The ID Migraine validation study. Neurology . 2003;61(3):375-82. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000078940.53438.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Callen E, Clay T, Alai J, et al. Migraine care practices in primary care: Results from a national US survey. Fam Pract . 2024;41(3):277-82. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmad054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kiarashi J, VanderPluym J, Szperka CL, et al. Factors associated with, and mitigation strategies for, health care disparities faced by patients with headache disorders. Neurology . 2021;97(6):280-9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000012261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hoffman KM, Trawalter S, Axt JR, Oliver MN. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 2016;113(16):4296-301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516047113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nagata JM, Ganson KT, Tabler J, Blashill AJ, Murray SB. Disparities across sexual orientation in migraine among US adults. JAMA Neurol . 2020;78(1):117-8. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.3406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hranilovich JA, Kaiser EA, Pace A, Barber M, Ziplow J. Headache in transgender and gender-diverse patients: A narrative review. Headache . 2021;61(7):1040-50. doi: 10.1111/head.14171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Urtecho M, Wagner B, Wang Z, et al. A qualitative evidence synthesis of patient perspectives on migraine treatment features and outcomes. Headache . 2023;63(2):185-201. doi: 10.1111/head.14430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Atlas S, Touchette D, Agboola F, et al. Acute Treatments for Migraine: Effectiveness and Value. Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Published February 25,2020. Accessed January 20, 2025. https://icer.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/ICER_Acute-Migraine_Final-Evidence-Report_092221.pdf

- 36. Newswire PR. FDA Approves Biohaven’s NURTEC® ODT (rimegepant) for Prevention: Now the First and Only Migraine Medication for both Acute and Preventive Treatment. Published May 27, 2021. Accessed January 16, 2025. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/fda-approves-biohavens-nurtec-odt-rimegepant-for-prevention-now-the-first-and-only-migraine-medication-for-both-acute-and-preventive-treatment-301301304.html#:˜:text=(NYSE%3A%20BHVN)%2C%20today,15%20headache%20days%20per%20month.

- 37. Pfizer . Pfizer’s ZAVZPRET™ (zavegepant) Migraine Nasal Spray Receives FDA Approval. Published March 10, 2023. Accessed January 16, 2025. https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/pfizers-zavzprettm-zavegepant-migraine-nasal-spray

- 38. Ellis A, Otuonye I, Kumar V, et al. Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP) Inhibitors as Preventive Treatments for Patients with Episodic or Chronic Migraine: Effectiveness and Value. Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Published July 3, 2018. Accessed January 20, 2025. https://icer.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ICER_Migraine_Final_Evidence_Report_070318.pdf

- 39. Charles AC, Digre KB, Goadsby PJ, Robbins MS, Hershey A; Headache Society American. Calcitonin gene-related peptide-targeting therapies are a first-line option for the prevention of migraine: An American Headache Society position statement update. Headache . 2024;64(4):333-41. doi: 10.1111/head.14692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Qaseem A, Cooney TG, Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta I, et al. ; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Prevention of episodic migraine headache using pharmacologic treatments in outpatient settings: A clinical guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med . 2025;178(3):426-33. doi: 10.7326/ANNALS-24-01052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Robblee J, Hakim SM, Reynolds JM, Monteith TS, Zhang N, Barad M. Nonspecific oral medications versus anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibodies for migraine: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Headache . 2024;64(5):547-72. doi: 10.1111/head.14693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lundbeck . FDA approves Lundbeck’s VYEPTI™ (eptinezumab-jjmr) – the first and only intravenous preventive treatment for migraine. Published February 21, 2020. Accessed January 16, 2025. https://www.lundbeck.com/us/newsroom/2020/fda-approves-lundbeck-s-vyepti---eptinezumab-jjmr----the-first-a

- 43. AbbVie . U.S. FDA Approves QULIPTA® (atogepant) for Adults With Chronic Migraine. Published April 17, 2023. Accessed January 16, 2025. https://news.abbvie.com/2023-04-17-U-S-FDA-Approves-QULIPTA-R-atogepant-for-Adults-With-Chronic-Migraine

- 44. Joshi S, Bioc J, Stone S. Mind over migraines: Disease burden, innovative therapies, and managed care trends in treating migraines. Presented at: AMCP 2025; April 2, 2025; Houston, TX.

- 45. Vyepti . Prescribing information. Lundbeck Seattle BioPharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2024. Accessed November 7, 2024. https://www.lundbeck.com/content/dam/lundbeck-com/americas/united-states/products/neurology/vyepti_pi_us_en.pdf

- 46. Aimovig . Prescribing information. Amgen, Inc.; 2024. Accessed November 7, 2024. https://www.pi.amgen.com/-/media/Project/Amgen/Repository/pi-amgen-com/Aimovig/aimovig_pi_hcp_english.pdf

- 47. Novartis . Novartis and Amgen announce FDA approval of Aimovig (TM) (erenumab), a novel treatment developed specifically for migraine prevention. Published May 18, 2018. Accessed January 16, 2025. https://www.novartis.com/news/media-releases/novartis-and-amgen-announce-fda-approval-aimovigtm-erenumab-novel-treatment-developed-specifically-migraine-prevention

- 48. Ajovy . Prescribing information. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc.; 2022. Accessed November 7, 2024. https://www.ajovy.com/globalassets/ajovy/ajovy-pi.pdf

- 49. Teva . Teva Announces U.S. Approval of AJOVY™ (fremanezumab-vfrm) Injection, the First and Only Anti-CGRP Treatment with Both Quarterly and Monthly Dosing for the Preventive Treatment of Migraine in Adults. Published September 14, 2018. Accessed January 16, 2025. https://ir.tevapharm.com/news-and-events/press-releases/press-release-details/2018/Teva-Announces-US-Approval-of-AJOVY-fremanezumab-vfrm-Injection-the-First-and-Only-Anti-CGRP-Treatment-with-Both-Quarterly-and-Monthly-Dosing-for-the-Preventive-Treatment-of-Migraine-in-Adults/default.aspx

- 50. Emgality . Prescribing information. Eli Lilly and Co; 2021. Accessed November 7, 2024. https://pi.lilly.com/us/emgality-uspi.pdf

- 51. Lilly . Lilly’s Emgality™ (galcanezumab-gnlm) Receives U.S. FDA Approval for the Preventive Treatment of Migraine in Adults. Published September 27, 2018. Accessed January 16, 2025. https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/lillys-emgalitytm-galcanezumab-gnlm-receives-us-fda-approval

- 52. Lilly . FDA Approves Emgality® (galcanezumab-gnlm) as the First and Only Medication for the Treatment of Episodic Cluster Headache that Reduces the Frequency of Attacks. Published June 4, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2025. https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/fda-approves-emgalityr-galcanezumab-gnlm-first-and-only

- 53. Qulipta . Prescribing information. AbbVie, Inc.; 2023. Accessed November 7, 2024. https://www.rxabbvie.com/pdf/QULIPTA_pi.pdf

- 54. Nurtec ODT . Prescribing information. Pfizer, Inc.; 2023. Accessed November 7, 2024. https://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=19036

- 55. BioSpace . Biohaven’s NURTEC™ ODT (rimegepant) Receives FDA Approval for the Acute Treatment of Migraine in Adults. Published February 27, 2020. Accessed January 16, 2025. https://www.biospace.com/biohaven-s-nurtec-odt-rimegepant-receives-fda-approval-for-the-acute-treatment-of-migraine-in-adults

- 56. Ubrelvy . Prescribing information. AbbVie, Inc.; 2023. Accessed November 7, 2024. https://www.rxabbvie.com/pdf/ubrelvy_pi.pdf

- 57. AbbVie . Allergan Receives U.S. FDA Approval for UBRELVY™ for the Acute Treatment of Migraine with or without Aura in Adults. Published December 23, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2025. https://news.abbvie.com/index.php?s=2429&item=123530

- 58. Zavzpret . Prescribing information. Pfizer, Inc.; 2023. Accessed November 7, 2024. https://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=19471

- 59. Reyvow . Prescribing information. Eli Lilly and Co; 2022. Accessed November 7, 2024. https://pi.lilly.com/us/reyvow-uspi.pdf

- 60. Lilly . Lilly’s REYVOW™ (lasmiditan), The First and Only Medicine in a New Class of Acute Treatment for Migraine, Receives FDA Approval. Published October 11, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2025. https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/lillys-reyvowtm-lasmiditan-first-and-only-medicine-new-class

- 61. McGinley JS, Mangrum R, Gerstein MT, et al. Symptoms across the phases of the migraine cycle from the patient’s perspective: Results of the MiCOAS qualitative study. Headache . 2025;65(2):303-14. doi: 10.1111/head.14817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Thomsen AV, Ashina H, Al-Khazali HM, et al. Clinical features of migraine with aura: A REFORM study. J Headache Pain . 2024;25(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s10194-024-01718-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Seng E, Lampl C, Viktrup L, et al. Patients’ experiences during the long journey before initiating migraine prevention with a calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibody (mAb). Pain Ther . 2024;13(6):1589-615. doi: 10.1007/s40122-024-00652-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Davies PTG, Lane RJM, Astbury T, Fontebasso M, Murphy J, Matharu M. The long and winding road: The journey taken by headache sufferers in search of help. Prim Health Care Res Dev . 2019;20:e4. doi: 10.1017/S1463423618000324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]