Summary

Background

Cognitive impairment and dementia are highly associated with obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Recent studies have demonstrated that GLP-1 receptor agonists can improve cognitive function through brain activation in patients with T2DM, compared to other oral glucose-lowering drugs. Mazdutide, a dual agonist of the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) and the glucagon receptor (GCGR), has been shown to simultaneously reduce body weight, blood glucose levels, and other comorbidities associated with obesity in patients with T2DM. While its insulinotropic and glucose-lowering effects through the GLP-1 pathway are well-established, mazdutide may also enhance energy expenditure via activation of the GCGR pathway. However, its potential impact on cognitive function remains to be elucidated.

Methods

This study aimed to investigate the effects of mazdutide on cognitive behaviour and cerebral pathology in male db/db mice, a model of T2DM, in comparison to dulaglutide, a GLP-1 receptor agonist. All animal findings are applicable to male mice only. Behavioural tests were conducted to evaluate cognitive function, and pathological analyses were performed to assess neurodegenerative markers in the brain. Furthermore, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomics analyses were employed to explore the underlying molecular mechanisms of mazdutide's effects.

Findings

Compared to dulaglutide, mazdutide significantly improved cognitive performance in db/db mice, as evidenced by comprehensive behavioural tests. Pathological assessments revealed improvements in neuronal structure and brain tissue integrity in the mazdutide-treated group. Multi-omics analyses further identified distinct molecular pathways involved in neuroprotection, energy metabolism, and synaptic plasticity, suggesting that dual GLP-1/GCGR activation contributes to enhanced cognitive resilience.

Interpretation

Our findings indicate that mazdutide, via its dual GLP-1/GCGR activation effects, exerts multifactorial improvements in cognitive function in the context of obesity and T2DM. These results suggest that mazdutide is a promising therapeutic option for mitigating cognitive deficits associated with metabolic disorders.

Funding

Medical Science and Technology Research and Development Plan Major Project Jointly Constructed by the Henan Province and Ministerial Departments in China (No. SBGJ202301010).

Keywords: Mazdutide, GLP-1R/GCGR dual agonism, Diabetes-associated cognitive dysfunction, db/db mice

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

T2DM is strongly linked to accelerated cognitive decline, with clinical epidemiological studies showing a 1.5–2-fold increased dementia risk and faster progression from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to Alzheimer's disease compared to population without diabetes. Obesity exacerbates dementia through metabolic dysregulation, neuroinflammation, and blood-brain barrier (BBB) impairment, yet conventional therapies (lifestyle interventions, GLP-1R monotherapy) have limited efficacy due to incomplete weight loss, side effects, or failure to address neurocognitive mechanisms. Large-scale and high-quality clinical trials from the REWIND cohort have conclusively demonstrated that GLP-1R agonists, such as dulaglutide, can reduce the risk of cognitive impairment by 14% (HR 0·86, 95% CI: 0·79–0·95, p = 0·0018). However, their single-receptor targeting limits the extent of metabolic and neurocognitive benefits. Dual/triple agonists (e.g., tirzepatide) show enhanced glycaemic/weight control and synaptic plasticity improvements in animal models, but their neurocognitive mechanisms remain poorly understood. Mazdutide, a GLP-1R/GCGR dual agonist, exhibits superior weight loss (11–15%) and multiple metabolic benefits in Phase III trials. To date, mazdutide has undergone numerous clinical trials, with its efficacy and safety in T2DM and weight reduction comprehensively validated, but its neurocognitive effects were unexplored. Therefore, limited understanding of how dual GLP-1R/GCGR activation exerts its effects in DACD. No preclinical or clinical data on mazdutide's neurocognitive efficacy or mechanisms compared to GLP-1R monotherapy.

Added value of this study

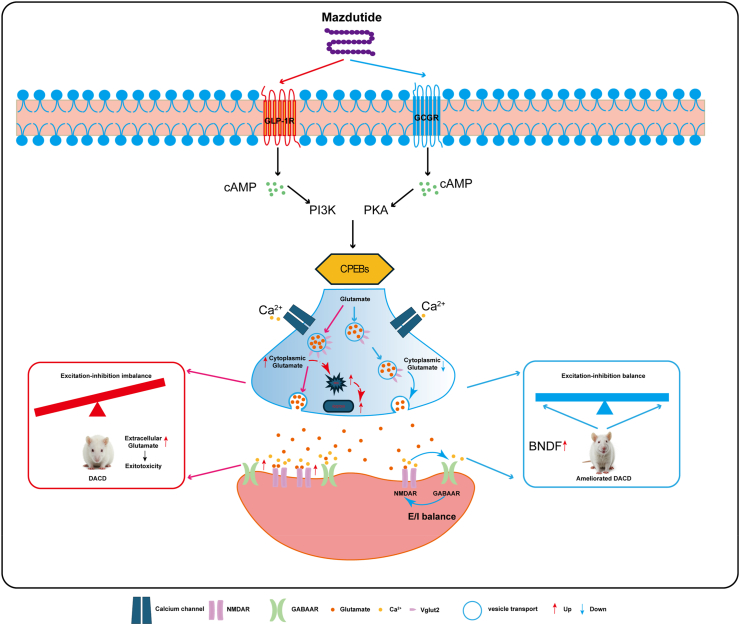

This study provides preclinical evidence that mazdutide performs better than GLP-1R monotherapy (dulaglutide) in ameliorating DACD, achieving greater weight loss (18·3% vs. 10·8%), glycaemic control, and reversal of hippocampal synaptic plasticity deficits. Besides, mazdutide restored neuronal integrity (Nissl bodies, NEUN+ cells), reduced demyelination, and enhanced synaptic plasticity. Importantly, we elucidated the critical mechanisms underlying the advanced improvement of cognitive impairment and pathological alterations, identifying Slc17a6/VGlut2-mediated glutamatergic dysregulation as a key factor in DACD. Mazdutide's achieves a balanced excitatory-inhibitory neurotransmission by downregulating VGlut2 expression and modulating NMDA/GABA receptor crosstalk. Multi-omics integration revealed that mazdutides dual receptor activation preferentially engages distinct pathways (neurotransmission, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation) compared to dulaglutide, highlighting GCGR's role in neuroprotection, which suggested that dual GLP-1R/GCGR activation may play a dynamically regulatory role in glutamatergic neurotransmission and enhance overall metabolic processes. These results implied that balanced GCGR co-activation enhances neurocognitive benefits compared to GLP-1R agonism alone, offering a mechanistic rationale for dual agonists in DACD. Multiple lines of evidence for cognitive improvement have established the link between VGlut2-mediated glutamate homoeostasis and DACD, offering valuable insights for future research.

Implications of all the available evidence

Mazdutide emerges as a promising therapeutic candidate for DACD, integrating robust metabolic benefits (weight loss, glycaemic control) with multimodal neuroprotection. Our findings highlight the superiority of dual agonists over single-receptor agents dulaglutide for patients with T2DM at high risk of cognitive decline in future therapeutic strategy. We emphasised the excitatory-inhibitory balance (via VGlut2/NMDA/GABA) as a potential therapeutic target in DACD. This study suggests that glucagon receptor (GCGR) activation may uniquely counteract glutamate excitotoxicity, a pathway less targeted by existing glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs). Future clinical trials should validate mazdutide's cognitive benefits in populations with T2DM and explore its potential in non-diabetic neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., Alzheimer's disease). Further mechanistic studies are needed to elucidate how GCGR activation directly modulates VGlut2 and whether mazdutide crosses the blood-brain barrier to exert central effects. Overall, this study provides insights into understanding how dual GLP-1R/GCGR agonism mitigates DACD, offering a blueprint for developing next-generation therapies that concurrently target metabolic and neurocognitive dysfunction in T2DM.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a major global health challenge, imposing profound medical and socioeconomic burdens through its systemic complications. Among these, the association between type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and accelerated cognitive decline has been well-documented, with diabetes-associated cognitive dysfunction (DACD) being a significant yet often underdiagnosed complication.1 Cognitive deficits associated with T2DM give rise to abnormal behaviours, including verbal memory, impaired attention, executive functioning and processing and motor speed, collectively impacting multiple cognitive domains.2 Clinical studies consistently demonstrate that patients with T2DM face a 1·5-to 2-fold elevated risk of dementia compared to population without diabetes, while progression rates from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to Alzheimer's disease (AD) among patients with T2DM ranges between 6% and 25%, significantly higher than the 0·2%–3·9% prevalence observed in the general population of similar age groups.3 Despite these alarming statistics, the lack of widely accepted early biomarkers and insufficient recognition of prediabetes-induced neurotoxicity frequently delay interventions until irreversible cerebral damage occurs.2 A deeper understanding of the neuropathological mechanisms of DACD is crucial for advancing diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

The aetiological complexity of DACD arises from intertwined metabolic dysregulations, with insulin resistance, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, glucose toxicity, and cerebral microvascular dysfunction constituting key pathological drivers.4 Notably, obesity—present in 60–90% of patients with T2DM globally—acts as a critical amplifier of these processes.5 Adipose tissue, functioning as an endocrine organ, secretes pro-inflammatory cytokines and hormones that exacerbate systemic insulin resistance while directly impairing blood-brain barrier integrity and neuronal survival.6 This dual role establishes obesity as both a metabolic catalyst and a direct mediator of neurocognitive decline in T2DM.7,8 Consequently, weight management plays a crucial role in mitigating DACD progression, supported by evidence that sustained 5–15% weight loss induces T2DM remission and reduces dementia risk.9 However, conventional lifestyle interventions often fail to achieve durable results in populations with diabetes due to physiological counter-regulatory mechanisms,10 while existing pharmacotherapies (e.g., insulin, sulfonylureas) frequently exacerbate weight gain or induce hypoglycaemia.11 These limitations underscore the need for therapeutic approaches that simultaneously address glycaemic control, weight reduction, and neuroprotection.

Recent advances in incretin-based therapies have significantly influenced treatment strategies. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs), exemplified by dulaglutide, demonstrate pleiotropic benefits including weight loss, glycaemic stabilisation, and preclinical evidence of blood-brain barrier penetration and neuroprotection.12 Building on this foundation, dual/triple receptor agonists targeting GLP-1R, glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide receptor (GIPR), and glucagon receptor (GCGR) may provide additional therapeutic benefits through synergistic modulating energy expenditure and glucose homoeostasis. Tirzepatide (GLP-1R/GIPR co-agonist), for instance, not only surpasses GLP-1RAs in glycaemic and weight control but also reverses hippocampal synaptic plasticity deficits in diabetic models.13 Nevertheless, the translation of these metabolic benefits into cognitive improvements remains incompletely characterised, particularly regarding pathway-specific neurorestorative mechanisms.14,15

Mazdutide (IBI362/LY3305677), a GLP-1R/GCGR dual agonist modelled on oxyntomodulin, has demonstrated potential as a candidate therapy. By balancing GLP-1R-mediated insulin sensitisation with GCGR-driven energy expenditure, mazdutide achieves superior weight reduction (11·3–14·84% over 24–48 weeks) while circumventing the hyperglycaemic risk inherent to isolated GCGR activation.16, 17, 18 Phase III trials confirm its favourable safety profile and cardiometabolic benefits in populations with obesity and T2DM,18 yet its impact on neurocognitive function has not been extensively studied. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial, as GCGR activation may modulate neuroinflammation-related pathways differently compared to GLP-1R-selective agents, and the substantial weight loss induced by mazdutide could exert unique effects on metabolism-mediated brain dysfunction.

Here, we present preclinical evidence that mazdutide ameliorates DACD progression through multimodal mechanisms, demonstrating neuroprotective effects distinct from GLP-1R monotherapy. Employing an integrative multi-omics approach—encompassing transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomics profiling—we systematically dissect the distinctive signalling networks engaged by mazdutide versus dulaglutide. Our findings provide evidence supporting the therapeutic potential of mazdutide for DACD and offer insights into mechanistic pathways that could inform personalised therapy for diabetic neurocognitive complications.

Methods

Drug treatment

Mazdutide (IBI362) was generously provided by Innovent Biologics, Inc. (Suzhou, China). Based on dose-response relationships established in prior preclinical studies, three escalating doses of mazdutide were selected: 50 μg/kg (low dose), 100 μg/kg (medium dose), and 200 μg/kg (high dose). Dulaglutide (Trulicity®, Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA) at 200 μg/kg served as the positive control. To minimise inter-individual variability, a standardised injection volume of 0·5 mL per mouse was administered via dorsal subcutaneous (s.c.) injection, with dosing conducted once every three days.

Animals and study design

The db/db mouse is a widely accepted model for studying T2DM and associated cognitive impairment, as it replicates key pathophysiological features of human DACD such as hyperglycaemia, insulin resistance, and neurodegeneration. Due to the potential influence of hormonal fluctuations on behavioural performance in females, only male mice were used in this study. Adult male db/db (C57BLKS/J-leprdb/leprdb) mice (TGP221027WX1) aged 6 weeks and weighing 28–34 g were purchased from Cyagen Biosciences Co. Ltd. (Suzhou, China). Age-matched heterozygote littermates (db/+) that are not diabetic were used as healthy controls. The experimental animals were housed under controlled environmental conditions, maintained at a temperature of 24 ± 1 °C, with a 12-h light-dark cycle, and humidity maintained at 50% ± 10%. They were provided adequate food and water throughout the duration of the study.

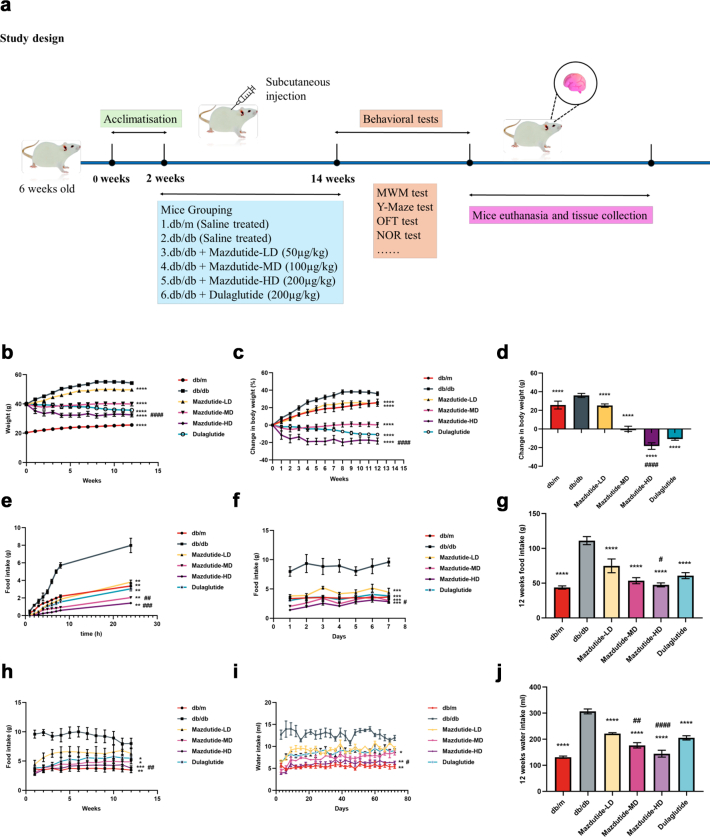

Sample size estimation was based on preliminary data from platform-crossing counts in the Morris water maze (mean difference = 2·46, standard deviation = 1·45). Power analysis (two-sided α = 0·05, power = 0·9) indicated that at least 10 mice per group were required for behavioural testing. Allowing for a 20% potential attrition rate, we enrolled 13 mice per group. Histological staining and RT-qPCR were conducted on 3–4 mice per group, and transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic analyses were performed using 3–6 mice per group. This design aligns with standard practice in the field (6–20 mice per group for behavioural studies)19, 20, 21 and ensures statistical validity while minimising animal usage. After a 2-week acclimatisation period, mice were randomly allocated into six experimental groups (n = 13 per group) using a simple randomisation method based on random number tables: normal control group (db/m), db/db model group (db/db), db/db + low-dose mazdutide group (Mazdutide-LD, 50 μg/kg), db/db + medium-dose mazdutide group (Mazdutide-MD, 100 μg/kg), db/db + high-dose mazdutide group (Mazdutide-HD, 200 μg/kg), and dulaglutide positive control group (Dulaglutide, 200 μg/kg). All mice except for db/db and db/m groups were subjected to subcutaneous injection of mazdutide or dulaglutide once every three days for 12 weeks while mice in db/db and db/m groups were subcutaneously injected with corresponding volume of normal saline. All animals were monitored daily, with predefined humane endpoints (e.g., severe illness, impaired mobility). No animals met exclusion criteria, and all completed the study and were included in the final analysis. Throughout the experiments, we monitored blood glucose levels, recorded body weights, closely observed mice’s food intake and water consumption conducted comprehensive behavioural tests after the treatment of drug administration. All behavioural and biochemical assessments were conducted in a consistent and balanced order to minimise potential confounding. Behavioural tests were performed by personnel not involved in the experimental design, to minimise potential bias. Following behavioural assessments, animals were deeply anaesthetised via intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg body weight) and euthanised by cervical dislocation to ensure humane endpoint compliance. Then, the tissue samples were collected by snap-freezing in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C or directly stored in 4% paraformaldehyde for histological analysis. Fig. 1a illustrates the experimental design timeline with the time of assays and manipulations.

Fig. 1.

Effect of mazdutide on body weight, food and water intake in db/db mice. (a) Study design illustration during the period of drug administration in db/db mice. (b) Effect on body weight and relative (c) and absolute (d) change following once-every-three days treatment (12 weeks) with dual GLP-1R/GCGR agonist mazdutide with low-, middle-, and high-dose (50, 100, 200 μg/kg) or dulaglutide (200 μg/kg). (e–h) 24 h, one week and 12 weeks of food intake after administration of saline, mazdutide, and dulaglutide. (i, j) The changes of water consumption within consecutive 12 weeks and total water intake. (b–d) n = 13/group; (e–j) n = 4 cages/group (3–4 mice per cage), data represent cage means. Data are represented as mean ± SD and were analysed by repeated-measures two-way ANOVA (b, c, e, f, h, i), one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey's multiple comparison test (d, g, j) at study end. ∗p < 0·05, ∗∗p < 0·01, ∗∗∗p < 0·001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0·0001 compared with db/db mice group; #p < 0·05, ##p < 0·01, ###p < 0·001, ####p < 0·0001 compared mazdutide group with dulaglutide group.

Behavioural testing experimental design

Open field test

The open field test (OFT) was conducted to measure general locomotor activity and exploratory behaviour.22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 The test apparatus consisted of a rectangular arena (50 cm × 50 cm × 40 cm; Noldus Ethovision video tracking system) divided into central and peripheral zones. Each mouse was placed in the central area and allowed to explore freely for 5 min. The total distance travelled, number of entries into the central zone, and time spent in the centre were recorded using the video-tracking system. These parameters provide a general assessment of spontaneous activity in a novel environment. While commonly reported in studies assessing anxiety-like behaviour, interpretation should consider that such measures are not specific to anxiety and may be influenced by multiple factors.

Morris water maze (MWM) tests

The Morris water maze is a widely used behavioural task in behavioural neuroscience to assess spatial learning.22 The experimental setup consisted of a large circular pool with a diameter of 1·5 m and a height of 35 cm (Shanghai Xinruan Information Technology Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China), filled with water maintained at approximately 24–25 °C. Mice underwent place navigation test for five consecutive days. On the sixth day, a probe trial test was conducted, in which mice were placed in the pool for 60 s without the platform. The time spent in the target quadrant, latency to locate the platform, and the number of platform crossings were recorded. Data acquisition was automated using a video tracking system (SuperMaze software, Shanghai Xinruan Information Technology Co. Ltd, China). Additionally, the time spent in the target quadrant during the probe trial was also analysed as an indicator of spatial memory retention.

MWM reversal

To assess the flexibility of spatial learning and memory in mice, following the completion of the classic Morris water maze experiment, we conducted reversal MWM tests. Reversal learning with the submerged platform was placed in the opposite quadrant.23 Likewise, we measured the time of mice spent searching for the first platform in the new target quadrant, the number of platform crossings.

Y-maze tests

The Y-maze, constructed from dark-coloured polyethylene plastic and consisting of three arms of equal length (30 cm long, 15 cm high, and 5 cm wide), labelled A, B, and C, is used to evaluate short-term memory in mice.24 This maze facilitates the assessment of spontaneous alternation behaviour, which requires interaction across different regions of the brain. Mice are positioned at the junction of the three arms and allowed to freely explore the maze undisturbed for 8 min. Spontaneous alternation, defined as consecutive entries into all three distinct arms in any sequence (i.e., ABC, ACB, CAB, BCA, CBA, BAC), is manually recorded. The total number of arm entries and alternations is documented from the video. The percentage of spontaneous alternations is calculated as (number of spontaneous alternations/(total number of arm entries − 2)) × 100.

Novel object recognition (NOR) test

The NOR task utilises natural inclination of mice to explore novel objects over familiar ones, providing a method to assess their non-spatial memory performance.25 As described previously, mice were initially placed into the testing box for 5 min one day prior to the NOR test. The NOR test consists of two trials: a 10-min sample exploration during which the mice familiarise themselves with two identical objects placed in the left and right corners of the testing box, and a subsequent testing trial (also 10 min) in which one of the familiar objects is replaced with a novel object. The time spent exploring each object during both the training and testing sessions was recorded using stopwatches. A recognition index (RI) for each animal was calculated using the discrimination ratio TN/(TF + TN), where TN represents the time spent exploring the novel object and TF represents the time spent exploring the familiar object.

Motor coordination assessments in mice

The “beam-walking” assay was utilised to evaluate motor coordination of mice, as described previously. In our study, the apparatus consisted of three beams: a 17 mm round plastic beam, a 11 mm round plastic beam, and a 5 mm square wood beam. Mice were trained on the beams continuously for 3 days, with 4 trials each day, to traverse the beams and enter a closed box at the end of each trial. Once baseline performance was stable, the latency to traverse the midpoint of each beam (at a distance of 80 cm) and the number of times the hind limbs slipped off each beam were recorded for each trial. The average scores for each beam at specific time points were then calculated and utilised for analysis.

Light-dark box test

The light–dark box system comprised two compartments: one dark compartment and one illuminated compartment (130 lux).26, 27, 28 The apparatus was positioned in an isolated room, shielded from any external interferences and noises, and equipped with a low-intensity white light source. The number of transitions between compartments and the time spent in each compartment were recorded for 5 min.

Rotarod test

Motor performance and motor balance were assessed using the accelerating-rotarod test (TSE Systems, Germany).27 Mice were placed on the rod, which accelerated from 4 to 30 rpm over a period of 3 min and then maintained a constant speed for an additional 4 min. The latency of the mice to fall off or reach the maximum observation period of 7 min was recorded. Latency to fall and speed were used as indicator of motor coordination and balance.

H&E staining

Mice brains were isolated from euthanised animals and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight at 4 °C, followed by embedding in paraffin. Brain slices were then de-paraffinized in xylene, rehydrated through a graded ethanol series, and stained with H&E (Biosharp, Wuhan, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The stained sections were imaged under a microscope.

Nissl staining

Nissl staining was performed to detect Nissl bodies within neurons, serving as an indicator of neural damage. The staining was carried out using a Nissl staining kit (Solarbio, China) according to the provided protocol. The brain sections were imaged under an optical microscope, and pathological changes in neurons and the number of Nissl bodies in the hippocampus were observed (400× magnification, Leica, Heidelberg, Germany).

Luxol fast blue (LFB) staining

LFB was performed according to previous description. Spinal cords were removed and fixed, dewaxed, rehydrated, and stained with 0·1% LFB. The corpus callosum and the spinal cord were analysed for the blue positive area to assess the degree of myelination. All images were analysed using Image J software (Broken Symmetry Software).

Immunochemistry staining

For immunochemical staining analysis, brain sections were treated with 3% H2O2 in methanol for 10 min to remove endogenous peroxidase. They were then blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at room temperature for 1 h and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies: rabbit anti-NeuN (ab177487, abcam; 1:1000), rabbit anti-MAP2 (ZRB2290, ZooMAb; 1:100), rabbit anti-MBP (ab216668, abcam; 1:300). After being washed, slices were then incubated with secondary antibodies (31460, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1:500). This study did not employ any custom or in-house antibodies. All antibodies were obtained from commercial sources and have been pre-validated by the manufacturers. Relevant RRIDs are provided in Supplementary Table S3. The stained sections were mounted on microscope slides and observed using a fluorescence microscope. For quantification of NeuN, MAP2, and MBP, four coronal sections (200 μm apart) per mouse were collected, and optical density was calculated using ImagePro Plus 6·0 software.

Golgi–Cox staining

Golgi–Cox staining was employed to assess the morphology of dendritic spines of hippocampal neurons, as described previously.26 Briefly, the brains of mice were dissected and processed using the Golgi–Cox Impregnation & Staining System according to the manufacturer's instructions (super Golgi Kit, Bioenno Tech, LLC). After impregnation, coronal sections (100 μm) were prepared at room temperature using a vibratome. These sections were then mounted on gelatine-coated glass slides and stained for further processing, in accordance with the manufacturer's guidelines. Analyses focused on individual CA3 and CA1 pyramidal neurons with fully impregnated dendritic trees, examining total dendritic length, the number of dendritic branches, and dendritic spine density per 10 μm. Images were captured using a confocal microscope (LSM880, Zeiss, Germany). Dendritic spines were reconstructed and analysed using Fiji and NeuronStudio (Version 0·9·92, http://research.mssm.edu/cnic/tools-ns.html).

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from mouse brain tissues using the RNA isolator Total RNA Extraction Reagent (R401-01, Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing, China), following the manufacturer's protocol. Subsequently, genomic DNA (gDNA) was removed, and reverse transcription was performed using the HiScript II Q RT SuperMix (Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing, China) to obtain cDNA for real-time quantitative analysis. This analysis was conducted using the ChamQ SYBR colour qPCR Master Mix (Q411-02, Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing, China) on the CFX Connect™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, USA) with primers selected based on previous studies. The relative mRNA level was quantified by the Ct value, and relative expression levels were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method. Details of the gene primer pairs are provided in Supplementary Table S4 in the Supplementary Materials.

Transcriptomic analysis

After euthanasia, mouse brain tissue samples (n = 3 per group) were dissected and immediately frozen on dry ice, then stored at −80 °C until further processing. The brain tissues were collected and sent to APExBIO Technology LLC for RNA-seq processing. Briefly, total RNA was extracted from the tissues using a standardised protocol and assessed for quality and quantity. Each sample was required to have at least 10 μg of RNA, with a concentration ranging from 200 to 350 ng/μL. All RNA samples exhibited high purity, with A260/280 ratios between 2·0 and 2·1. The sample mRNA libraries were prepared using the Illumina platform, and the raw reads were trimmed for adaptor sequences and low-quality bases. Clean reads were aligned to the reference genome, and gene expression levels were quantified. Differential expression analysis was performed to identify genes associated with neurological function, followed by functional enrichment analysis to elucidate relevant biological pathways.

Proteomic analysis

The brain tissue samples were lysed using SDT protein lysate buffer (containing 4% SDS, 10 mM DTT, and 100 mM TEAB) after liquid nitrogen grinding. Complete lysis was achieved through sonication in an ice water bath for 5 min. The lysate was transferred to clean tubes and subjected to a reaction at 95 °C for 8 min, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 g at 4 °C for 15 min. The resulting supernatant was supplemented with an adequate amount of iodoacetamide (IAM) and incubated in darkness at room temperature for 1 h. Subsequently, four-fold volume of pre-cooled acetone at −20 °C was mixed with the supernatant for precipitation and maintained at −20 °C for 2 h. The precipitate was centrifugated at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the sediment was collected. After washing twice with prechilled acetone, the protein was resuspended in 100 mM TEAB (8 M urea, pH = 8·5).

Protein samples dissolved in 100 μL buffer were digested at 37 °C for 4 h with trypsin and 100 mM TEAB buffer, followed by the addition of trypsin and CaCl2 for overnight digestion. The pH was adjusted to less than 3 by adding formic acid, and the samples were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 5 min at room temperature. The supernatant was slowly eluted in 0·1% formic acid, 3% acetonitrile using a C18 desalting column. Then, the appropriate eluent (0·1% formic acid, 70% acetonitrile) was added for washing three times, and the filtrate was collected and lyophilised. The eluents were freeze-dried and resuspended in 0·1% formic acid (flowing phase A, 10 μL). After centrifugation at 14,000 g (at 4 °C) for 20 min, 1 μL supernatant was transferred to a C18 column (300 μm × 5 mm, Thermo Scientific). The peptide was isolated using a μPAC Neo High Throughput column (Thermo Scientific) to perform gradient separation using acetonitrile with 0·1% formic acid (flowing phase B, 80% acetonitrile, 0·1% formic acid). The elution gradients were as follows: 0–0·1 min (4%–6%); 0·1–1·1 min (6%–12%); 1·1–4·3 min (12%–22·5%); 4·3–6·1 min (22·5%–45%); 6·1–8 min (flowing phase B maintained at 99%). Peptides were separated and analysed by the Orbitrap Astral mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) for DIA (data-independent acquisition) analysis.

All resulting spectra were searched against the proteome data using the proteomics software Spectronaut 17. The search included variable modifications of carbamidomethyl, methionine oxidation, and N-terminal acetylation. The false discovery rate (FDR) cutoff for peptide and protein identifications was set at 0·01. When peptides identified were shared between two proteins, they were merged and reported as a single protein group. Missing values in the proteomic data were considered missing not at random (MNAR), as they primarily resulted from low-abundance proteins falling below the detection limit. Proteins completely missing across all samples were excluded, while partially missing values were imputed using half the minimum non-zero value in the dataset to simulate left-censored low-abundance signals. The overall missing rate was extremely low (<0·05% in all samples), minimising any potential impact on downstream analyses. After log2 transformation [P_{k} = T.test(Log2(R_{ik}; i/in A), Log2(R_{ik}; i/in B))], differentially expressed proteins between two groups (Control vs. Model; Model vs. Mazdutide; Model vs. Dulaglutide) were identified using univariate analysis (t-test) with significance set at p < 0·05 for subsequent analysis. Differentially expressed proteins were further analysed using volcano plots and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis. PPI networks were analysed using the STRING database.

Metabolomics analysis

Brain samples were analysed using LC/MS (Liquid Chromatograph Mass Spectrometer) method. Throughout the analytical process, samples were maintained in an automatic sampler at 8 °C. Separation was achieved using an ultra-high performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) system equipped with an HSS T3 chromatography column (2·5 μm, 2·1 mm × 150 mm). The injection volume was set to 2 μL, the column temperature was maintained at 40 °C, and the flow rate was set at 0·3 mL/min. The chromatographic mobile phase consisted of four components: A (0·1% formic acid in water), B (0·1% formic acid in methanol), C (0·05% acetic acid in water), and D (0·05% acetic acid in methanol). Quality control (QC) samples, consisting of a mixture of all samples under analysis, were interspersed within the sample queue to monitor and evaluate system stability and experimental data reliability. Each sample underwent electrospray ionisation (ESI) in both positive (ESI+) and negative (ESI−) ion modes for mass spectrometry acquisition. Following UPLC separation, mass spectrometric analysis was performed using a mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) with the following conditions: heater temperature 300 °C, sheath gas flow rate of 50 arb, auxiliary gas flow rate 13 arb, spray voltage ±2·5 kV, S-lens RF level 50%, capillary temperature 325 °C. The scan range was set from 70 to 1050 m/z, with separate scans conducted for positive and negative ions. Data analysis was performed using Xcalibur version 4·1 software.

To ensure reliable and high-quality metabolomics data, rigorous QC was implemented. QC samples were intermittently injected multiple times between formal sample injections to assess method stability and data quality. Although slight differences among QC samples may exist due to potential systematic errors in sample extraction and analysis, smaller differences indicate higher method stability and better data quality. Raw data extraction, peak identification, and quality control processing were conducted using hardware and software from Metabolon. Compound identification was based on accurate mass and ion spectrum by comparing with entries in a library of purified standards and literature, with library matching of each compound in every sample checked and adjusted when necessary.

Ethics

All experimental procedures were conducted in strict accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals issued by the Ethical Committee of the Guangdong Medical Experimental Animal Centre, China (Approval No. D202311-2). Humane care was provided to all animals throughout the study. Furthermore, all animal experiments were designed and reported in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Statistics

Other than RNA sequencing proteomic and metabolomic data, other data were analysed by t-tests or one-way ANOVA when two groups or three and more groups were compared with the GraphPad Prism software (version 9·5·1), respectively. One-way or two-way ANOVA was appropriately used for comparisons among multiple groups in terms of behavioural tests, RT-qPCR, histological analysis and immunochemistry staining followed by post hoc Tukey's multiple comparisons test. To further account for multiplicity across endpoints, FDR correction was also applied to both raw ANOVA and unadjusted pairwise p values. For outcomes measured repeatedly in the same animals over time, repeated-measures two-way ANOVA was applied. Data were presented as means ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise indicated. p < 0·05 was presented as statistically significant.

Role of funders

This study was supported by the Health Commission of Henan Province, China (No. SBGJ202301010). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, data Formal analysis, data interpretation, manuscript writing, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Results

Mazdutide demonstrated significant effects on body weight loss and food intake reduction in db/db mice

Firstly, we evaluated the effect of mazdutide on body weight loss and food intake. As Fig. 1a shown, eight-week-old db/db mice (n = 13/group) were treated for 12 weeks with different subcutaneous (s.c.) doses of mazdutide (50, 100, 200 μg/kg) and dulaglutide (200 μg/kg) administered once every three days. Significant loss of body weight at all doses were observed compared with db/db model group (RM two-way ANOVA, p < 0·0001, Fig. 1b). Dose-dependent effects on body weight change were observed following treatment with mazdutide (Fig. 1b–d). Compared with baseline, saline-treated db/db model group exhibited a body weight change of +36·033% within 12 weeks (Fig. 1d). However, there was apparently dose-dependent reduction in body weight during mazdutide treatment, with changes of +25·178%, +0·246%, and −18·270%, respectively, at the end of treatment (Fig. 1d). Particularly, Mazdutide-HD showed statistically significant reductions in body weight compared with dulaglutide administration (ANOVA + Tukey's, p < 0·0001, Fig. 1d). Further analysis demonstrated, different dose of mazdutide (50, 100, 200 μg/kg) and dulaglutide robustly suppressed food intake and water consumption relative to saline treated models in db/db mice after administration (Fig. 1e–j). The dose-dependent effect of mazdutide in decreasing food intake was evident at 0–24 h (Fig. 1e) or within one week (Fig. 1f) or during consecutive 12-weeks treatment (Fig. 1h), at which time mazdutide also significantly suppressed water consumption (Fig. 1i). A consistent trend of significant dose-dependent reductions in total food and water intake was observed following mazdutide administration compared with saline-treated db/db mice over 12 weeks (Fig. 1g–j). The strongest anorectic effect and reduction in water consumption were observed with Mazdutide-HD compared to dulaglutide (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·032, Fig. 1g; p < 0·0001, Fig. 1j).

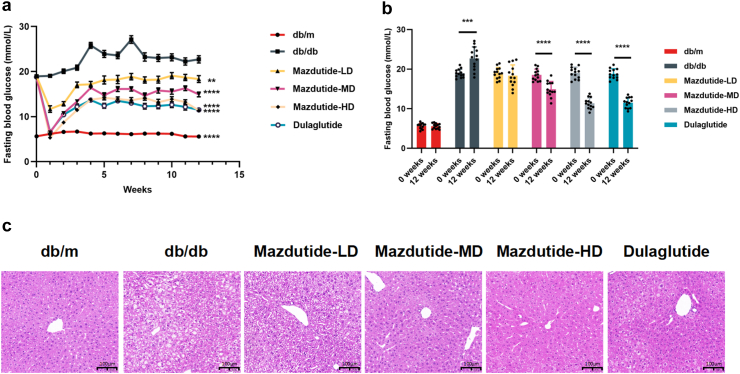

Mazdutide exhibits metabolic effects, in db/db mice

Compared to the db/db model group, both mazdutide and dulaglutide resulted in a reduction of blood glucose levels for up to 12 weeks. Although there was an initial decrease in fasting glucose levels in the first weeks after drug administration due to marked reduction of food intake, then the altered glucose levels eventually stabilised at significantly lower levels in comparison to the db/db mice (Fig. 2a). Each group at the study end (+12 weeks) was compared to their baseline blood glucose levels, and it was found that there was a significant increase in blood glucose levels in the db/db group (t-test, p = 0·0002) and no significant difference in db/m control group. Mazdutide was shown to lower glucose levels in a dose-dependent manner, with the high dose of mazdutide (Mazdutide-HD) showing comparable effects to dulaglutide (Fig. 2b). Finally, the H&E staining sections of liver tissues suggested that both mazdutide and dulaglutide decreased hepatic steatosis and inflammation, while mazdutide improved these parameters in a dose-dependent manner. Mazdutide-HD at 200 μg/kg showed significantly greater hepatic protection than dulaglutide (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

12-week treatment effects of mazdutide and dulaglutide in db/db mice. (a, b) Effects on blood glucose level (n = 13). (c) Representative liver section images of H&E staining in saline (db/db and db/m), mazdutide and dulaglutide treatments are shown (scale bar: 100 μm, 200× magnification). Data are represented as mean ± SD and were analysed by repeated-measures two-way ANOVA (a) and two-tailed paired t-test with post hoc Tukey's multiple comparison test (b) at study end. ∗∗p < 0·01, ∗∗∗p < 0·001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0·0001 compared with db/db mice group.

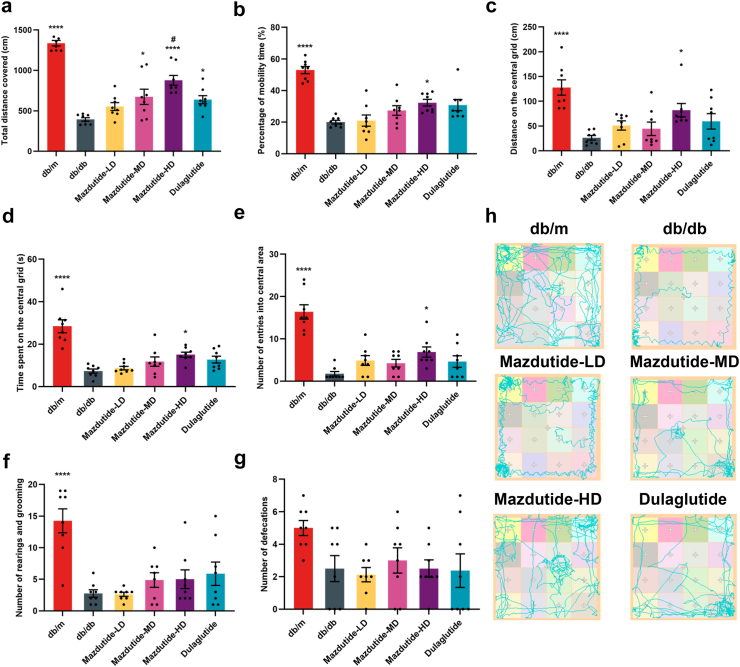

Mazdutide treatment improve locomotor activity and exploratory behaviour in db/db mice

The OFT was used to assess locomotor activity and exploratory behaviour in mice (Fig. 3), providing a means to evaluate the effect of mazdutide treatment on autonomous activity, exploratory tendencies, and anxiety of experimental animals within novel environments. In the OFT, the total distance travelled was significantly increased in Mazdutide-MD (ANOVA + Tukey's, FC = 1·71, p = 0·013), Mazdutide-HD (ANOVA + Tukey's, FC = 2·22, p < 0·0001), and dulaglutide groups (ANOVA + Tukey's, FC = 1·62, p = 0·041). High-dose mazdutide induced a greater increase in locomotor activity compared with dulaglutide (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·048, Fig. 3a). Mazdutide-HD also significantly increased the travelled distance on the central grid (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·035) and percentage of mobility time (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·032) as compared to the db/db group (Fig. 3b and c). We also found that the Mazdutide-HD-treated mice had an increased number of entries into the central areas (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·046) and time spent on the central grid (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·045) in comparison to the db/db group (Fig. 3d and e). Finally, no significant differences were observed in rearing, grooming, or defecation frequency compared with the db/db group (Fig. 3f and g).

Fig. 3.

Mazdutide improves exploratory behaviours in T2DM db/db mice. (a) Total distance travelled in the open field; (b) Percentage of mobility time; (c) Distance on the central grid; (d) Time spent on the central grid; (e) Number of entries into central area; (f) Number of rearings and groomings; (g) Number of defecations; (h) Representative travel pathway of mice exploration during the open field tests (OFT). Results are expressed as mean ± SD and were analysed by one-way ANOVA (a-g) with post hoc Tukey's multiple comparison test. db/db, db/m, Mazdutide-LD, Mazdutide-MD, Mazdutide-HD, and Dulaglutide (n = 8) mice per group. ∗p < 0·05, ∗∗∗∗p < 0·0001 compared with db/db group; #p < 0·05 compared Mazdutide with Dulaglutide group.

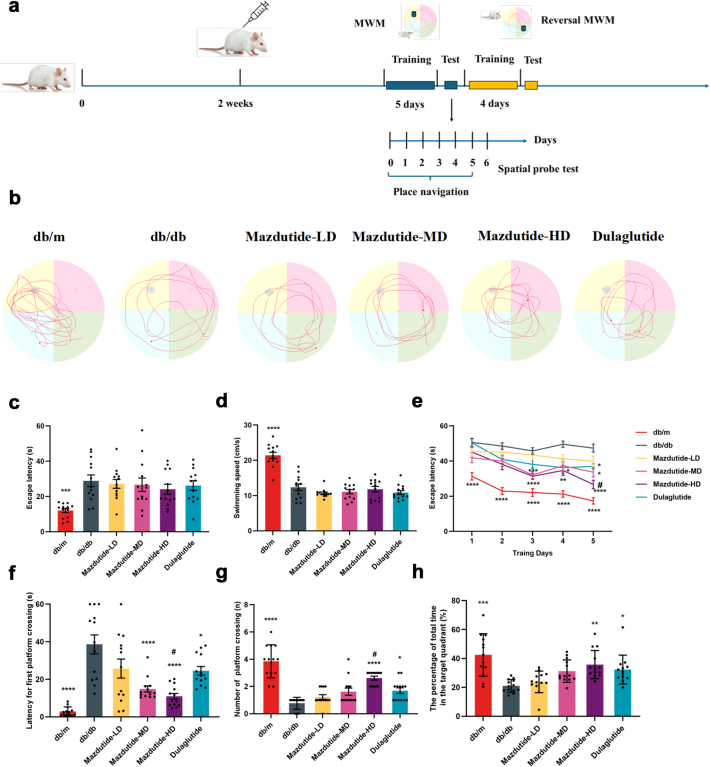

Mazdutide treatment ameliorate learning and memory deficits in db/db mice

The ability of spatial learning and memory on db/db mice was assessed after three doses of mazdutide and dulaglutide positive control group treatment. MWM task was performed to observe the training process of mice. Fig. 4a showed the timeline of MWM and reversal MWM, including the training and test process. Results showed that swimming speed in normal db/m mice group were better than other five groups and had shorter latency time, no difference was found in other five groups (Fig. 4c and d). The escape latency among Mazdutide-MD (RM two-way ANOVA, p = 0·010), Mazdutide-HD (RM two-way ANOVA, p < 0·0001), and dulaglutide (RM two-way ANOVA, p = 0·010) groups were evidently shorter than that in the db/db model group at day 5, and Mazdutide-HD showed a stronger effect than dulaglutide group in improving memory to find the hidden platform (Fig. 4e). Besides, less time was spent in the Mazdutide-MD (ANOVA + Tukey's, p < 0·0001), Mazdutide-HD (ANOVA + Tukey's, p < 0·0001), and dulaglutide (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·032) groups than db/db mice, and the escape latency was significantly reduced in Mazdutide-HD group than dulaglutide treatment (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·041) when mice firstly crossed the platform (Fig. 4f). Furthermore, the number of platform crossing in the spatial probe trials was dose-dependent increase in mazdutide groups (Fig. 4g). Mazdutide-HD (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·002) and dulaglutide (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·040) spent more time in the target quadrant than this in db/db group (Fig. 4h). Results of the MWM tests suggest that the learning and memory ability of db/db mice can be improved by mazdutide and increasing the dosage of the mazdutide appears to enhance this effect.

Fig. 4.

Mazdutide attenuates the learning and memory impairments in T2DM db/db mice. (a) The time axis diagram of Morris water maze (MWM) and reversal MWM tests; (b) Representative traces in MWM test; (c) The mean escape latency and (d) the swimming speed (cm/s) before the orientation navigation experiment; (e) The escape latency of five consecutive days training in the quadrant of the platform; (f) Latency of first crossing to the platform in spatial probe test; (g) Number of crossing the platform; (h) The percentage of total time in the target quadrant. db/db, db/m, Mazdutide-LD, Mazdutide-MD, Mazdutide-HD, and Dulaglutide (n = 13) mice per group. Data are represented as mean ± SD and were analysed by repeated-measures two-way ANOVA (e), one-way ANOVA (c, d, f, g, h) with post hoc Tukey's multiple comparison test at study end. ∗p < 0·05, ∗∗p < 0·01, ∗∗∗p < 0·001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0·0001 compared with db/db group; #p < 0·05 compared Mazdutide with Dulaglutide group.

Next, we assessed the reversal learning and memory in db/db mice by providing additional training trials on days 7–10 with the platform in this new location Supplementary Figure S1a. Consistent results were observed in Supplementary Figure S1b and c we observed Mazdutide-HD significantly reduced the time spent for the first platform crossing (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·048, Supplementary Figure S1d) and the number of platforms crossing of mice (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·047, Supplementary Figure S1e). Regarding spontaneous alteration changes in the Y maze (Supplementary Figure S1f and g), the transition from low to high doses of mazdutide (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·009, p < 0·0001, p < 0·0001) and dulaglutide (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·0001) demonstrated marked spontaneous alteration restoration, with Mazdutide-HD showing superior efficacy as compared with dulaglutide (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·039). WMM and Y maze tests indicated that mazdutide has potential in improving spatial memory and learning in db/db mice, evidence supporting the potential therapeutic efficacy of mazdutide in mitigating cognitive impairments.

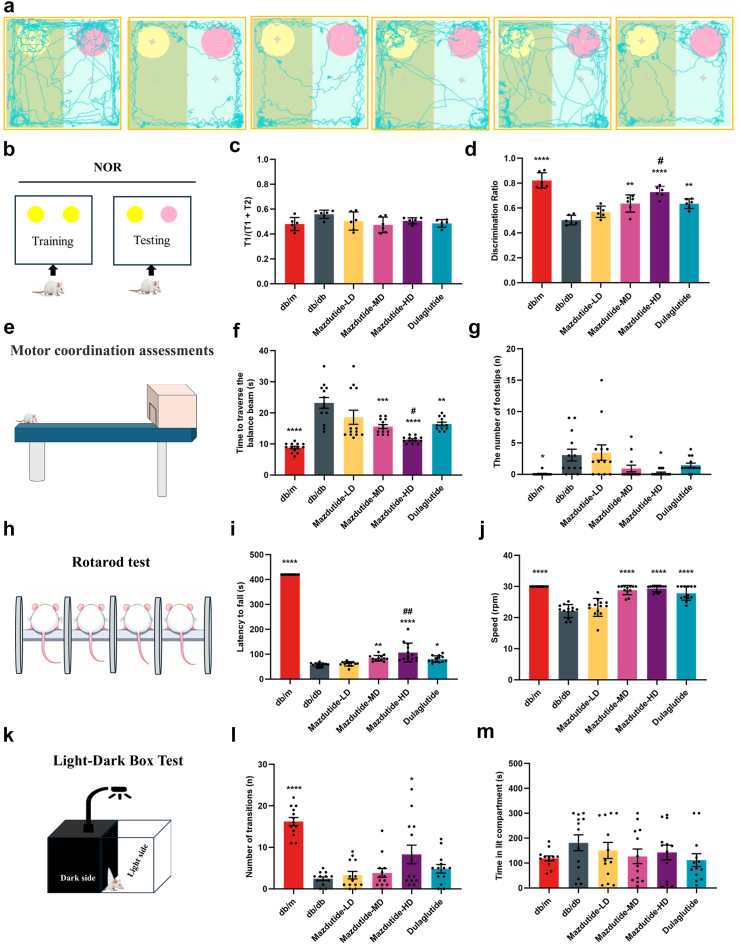

Mazdutide improves motor coordination, balance and anxiety-like behaviour

To further determine whether cognitive functions, including working memory, motor coordination, and anxiety-like behaviour were altered in response to mazdutide, we subjected the db/db mice to a battery of behaviour tests. Short-term memory impairment and attention deficits were evaluated through NOR tests (Fig. 5a and b), the exploration time spent in T1 phase was at a similar level for all tested groups (Fig. 5c). We observed db/db mice showed no preference between a familiar and novel objects, Mazdutide-MD (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·002), Mazdutide-HD (ANOVA + Tukey's, p < 0·0001), and dulaglutide groups (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·002) significantly discriminated new objects compared to the db/db group (Fig. 5d). Meanwhile, there were significant differences in discrimination ratio between Mazdutide-HD and dulaglutide group (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·040), suggesting that mice after Mazdutide-HD treatment showed exploratory preference for novel objects (Fig. 5a, b, and d). Motor coordination, balance can be assessed with Beam-walking and rotarod tests. Beam-walking performance data exhibited consistent results in improving a progressive cognitive impairment in motor and balance ability (Fig. 5e–g). db/db increased the time to traverse the balance beam (Fig. 5f). Mazdutide-HD apparently improved beam-walking performance by decreasing the time spent in balance beam (ANOVA + Tukey's, p < 0·0001, Fig. 5f) and number of foot slips (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·046, Fig. 5g). Moreover, the latency to fall (s) and speed in the rotarod test significantly increased after Mazdutide-MD, Mazdutide-HD, and dulaglutide administration (Fig. 5h–j). Motor coordination and rotarod tests suggest that mazdutide, particularly Mazdutide-HD could help mitigate balance and motor coordination deficits, common symptoms observed in db/db mice. Meanwhile, anxiety-like behaviour amelioration with Mazdutide-HD showed in the significant increased number of transitions (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·016, Fig. 5l) in the Light-Dark Box (LDB) test (Fig. 5k), but time spent in the lit compartment did not differ significantly among groups (Fig. 5m), limiting the strength of the conclusion. Combined with OFT assessment and the dose-dependent increase in the number of light-dark transitions observed in the LDB test, albeit statistically non-significant, suggests a potential trend toward reduced anxiety-like behaviour in mazdutide-treated mice.

Fig. 5.

Mazdutide comprehensively ameliorate cognitive impairment of db/db mice in other multiple cognitive behaviours. (a–d) Results of the novel object recognition (NOR) test. (e–g) Results of beam-walking test. (h–j) Results of rotarod test. (k–m) Results of light/dark (LD) transition test. (a–b) The travel traces and schematic diagram of NOR test. (c, d) Percentage of exploration time spent in T1 phase on the novel object (c) and the object-location discrimination ratio (d). (e–g) The diagram of beam-walking test (e); time spent to traverse the balance beam (f) and the number of foot slips on the beam (g). (h–j) Schematic diagram of rotarod test (h); (i) latency to fall and (j) rotarod speed (j). (k–m) Schematic diagram of light/dark (LD) transition test (k); (m) time spent in the lit box and number of transitions (l). Data are represented as mean ± SD in (c, d, i, j) and mean ± SEM in (f, g, l, m), and were analysed by one-way ANOVA (c, d, f, g, i, j, l, m) with post hoc Tukey's multiple comparison test at study end. n = 6 for c, d; n = 13 for f, g, i, j, l, m.∗p < 0·05, ∗∗p < 0·01, ∗∗∗p < 0·001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0·0001 compared with db/db group; #p < 0·05, ##p < 0·01 compared Mazdutide with Dulaglutide group.

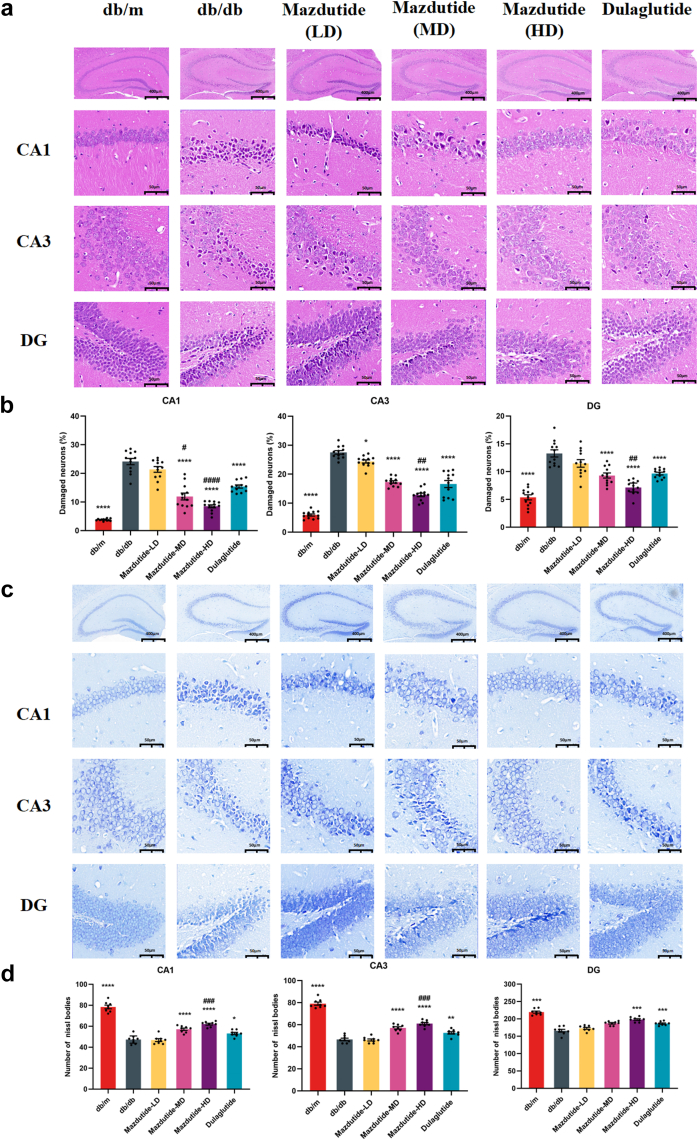

Mazdutide ameliorates the neuronal injury and death of the hippocampus in db/db mice

The hippocampus serves as a crucial neural centre associated with learning and memory, closely related to cognitive functions. To investigate whether mazdutide could ameliorate structural brain damage in db/db mice, we employed H&E and Nissl staining to observe damage and neuronal death in the CA1, CA3, and DG areas of the hippocampus (Fig. 6). In the db/m control group, hippocampal neurons appeared as large, polygonal, and closely arranged with normal cell morphology and uniform nuclear staining in CA1, CA3, and DG regions of the hippocampus. In contrast, severe pathological damage was evident in db/db model group by the loosely arranged neuronal cells, nuclear pyknosis, tissue cavitation, and structural disorganisation in H&E sections (Fig. 6a) and unclear structures of Nissl bodies (Fig. 6c).

Fig. 6.

The histological changes in CA1, CA3, and DG regions of mouse hippocampus of db/m, db/db, Mazdutide-LD, Mazdutide-MD, Mazdutide-HD, and Dulaglutide groups by H&E and Nissl staining. (a) Representative micrographs of H&E staining (scale bar = 400 μm) in the CA1, CA3, and DG regions (scale bar = 50 μm); (b) The percentage of damaged neurons in the CA1, CA3, and DG regions (n = 4, three visual fields were counted per mouse); (c) Representative micrographs of Nissl staining (scale bar = 400 μm) in the CA1, CA3, and DG regions (scale bar = 50 μm); (d) Quantitative analysis of the number of Nissl bodies in hippocampus of in the CA1, CA3, and DG regions (n = 4, two visual fields were counted per mouse); Data are shown as means ± SEM and were analysed by one-way ANOVA (b, d) with post hoc Tukey's multiple comparison test at study end. ∗p < 0·05, ∗∗p < 0·01, ∗∗∗p < 0·001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0·0001 compared with db/db group; #p < 0·05, ##p < 0·01, ###p < 0·001, ####p < 0·0001 compared Mazdutide with Dulaglutide group.

However, these histological damage features were improved by Mazdutide-LD, Mazdutide-MD, Mazdutide-HD, and dulaglutide treatment. Of note, Mazdutide-HD in ameliorating neural injury showed greater effects than dulaglutide in CA1, CA3, and DG regions (ANOVA + Tukey's, p < 0·0001, p = 0·004, p = 0·009, Fig. 6b), respectively. Meanwhile, Nissl staining also revealed similar results in attenuating neuron loss. As expected, the number of Nissl bodies was significantly increased, especially in the CA1 and CA3 regions of the hippocampus in the mice of the Mazdutide-HD group (Fig. 6c), indicating that Mazdutide-HD could alleviate T2DM-induced neuron loss to some extent in the CA1, CA3, and DG regions of the hippocampus of mice as compared to the db/db group (ANOVA + Tukey's, p < 0·0001, p < 0·0001, p = 0·0003, Fig. 6d). These results suggest that mazdutide may have neuroprotective effects and could mitigate T2DM-induced neuronal damage in the hippocampus.

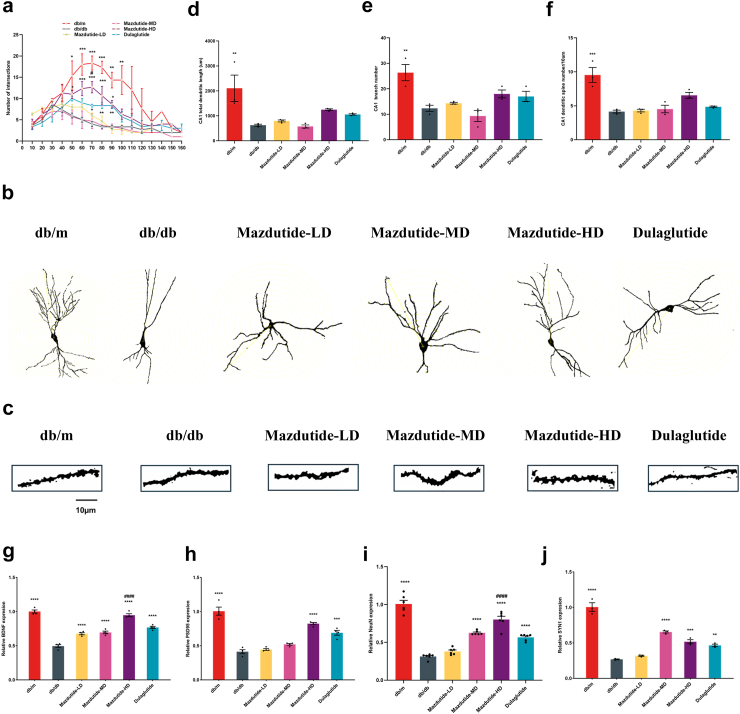

Mazdutide preserves dendritic arborisation and spine density in the hippocampus of db/db mice

Behavioural changes and neuronal damage indicated that long-term diabetes or obesity can lead to disorders in neurological regulation, disrupting the transmission of nerve signals and resulting in cognitive deficits. This disruption in synaptic plasticity contributes to dysregulated synaptogenesis. To investigate the potential regulatory effects of mazdutide on neuroplasticity and neurogenesis, we assessed spine density in synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis in the hippocampus of mice via Golgi-Cox staining and RT-qPCR assays. We next analysed the protective effect of mazdutide on T2DM-induced hippocampus abnormalities through observation of morphology of Golgi-stained CA1 and CA3 neurons (Fig. 7, Supplementary Figure S2). The results revealed a significant reduction of the number of dendritic intersections of pyramidal neurons at 50 μm–100 μm in CA1 and 60 μm–110 μm in CA3 from the cell body in db/db group compared to db/m group; mazdutide treatment, particularly Mazdutide-HD, mitigated this effect (Fig. 7a and b, Supplementary Figure S2a and b). Specifically, to assess the function and morphology of dendrites, we examined the elimination of postsynaptic dendritic spines in the hippocampus using Golgi-Cox staining. The results showed a remarkable loss of synaptic density in db/db mice. However, compared with the db/db group, mazdutide administration attenuated the decrease of several spines in db/db mice (Fig. 7c, Supplementary Figure S2c). Overall, Mazdutide-HD showed greater effects in preserving hippocampal dendritic arborisations (Fig. 7d–f, Supplementary Figure S2d–f), with significantly increased spine numbers/10 μm to the db/db group. Finally, the expression level of Bdnf, Psd95, Neun, and Syn1 were significantly increased in Mazdutide-HD treatment group (ANOVA + Tukey's, p < 0·0001, p < 0·0001, p < 0·0001, p = 0·0008, Fig. 7g–j). These findings suggested that Mazdutide-HD could preserve neuronal morphology and reduce loss of dendritic spines.

Fig. 7.

Mazdutide ameliorated abnormal neuronal morphology and loss of dendritic spines in the hippocampal CA1 region of db/db mice. (a) Quantification of dendritic intersections of neuronal dendrites in the hippocampus among the six groups in CA1; (b) Representative images of hippocampal neuronal tracings. (c) Representative images of Golgi-stained dendritic spine segments from the hippocampal CA1 region from each experimental group. Scale bar, 10 μm (d) total dendritic length in CA1 area; (e) the number of neuronal branches in the CA1 area of hippocampus and (f) CA1 dendritic spine number per 10 μm of hippocampal neurons; (g–j) BDNF, PSD95, NEUN, and SYN1 mRNA expression collectively reflect neuronal survival status, synaptic structure, and plasticity. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM and were analysed by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey's multiple comparison test. n = 3 for a, d, e, f, j; n = 4 for g, h; n = 6 for i. ∗p < 0·05, ∗∗p < 0·01, ∗∗∗p < 0·001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0·0001 compared with db/db group; #p < 0·05, ####p < 0·0001 compared Mazdutide with Dulaglutide group.

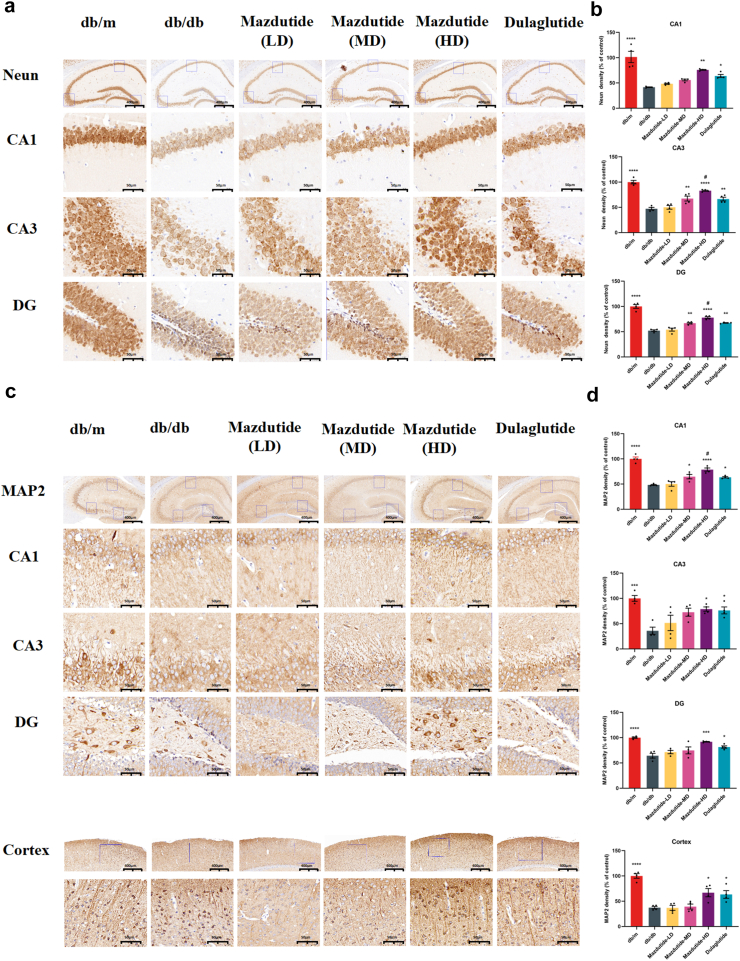

Mazdutide is associated with increased NEUN and MAP2 immunoreactivity of db/db mice to mitigate neurodegenerative pathology

Since learning and memory processes are intricately linked to neurogenesis and neural signal transduction in the brain, we sought to verify whether mazdutide could stabilise the microtubules of the dendritic cytoskeleton, and support the neurone's morphological integrity and functions. To comprehensively assess the ameliorated efficacy of mazdutide on mice with cognitive deficits, we selected NEUN and MAP2 as neuronal markers in all layers of the hippocampus (CA1, CA3, DG) and cortex. Representative immunohistochemistry results are showed in Fig. 8, immunopositive plaques of NEUN and MAP2 could be seen in each group. The highest positive density of NEUN and MAP2 protein levels in all layers of hippocampus and cortex were found in db/m group in comparison to other groups (Fig. 8a,c). Following mazdutide treatment, a notable dose-dependent augmentation in the expression levels of these proteins was observed across the CA1, CA3, and DG regions of the hippocampus (Fig. 8b,d). In detail, consistent with previous results, Mazdutide-HD showed significantly greater effects in all brain areas of db/db mice, although Mazdutide-MD significantly increased the partly regions in brain of NEUN and MAP2 expression (NEUN in CA3, DG; MAP2 in CA1). In comparison to dulaglutide, the Mazdutide-HD group exhibited a notable increase in the density of NEUN, MAP2-immunopositive aggregates within the hippocampus. Specifically, significant elevations were observed in NEUN deposition within the CA3 (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·031) and DG regions (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·040), MAP2 expression in CA1 (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·047, Fig. 8b,d). In addition, we also observed the evident alterations in MAP2 immunoreactivity in the cortex of mice brain (Fig. 8c). Specifically, the aggregates of MAP2 exhibited marked increase following treatment with Mazdutide-HD and dulaglutide. In summary, these findings collectively suggest that mazdutide plays a crucial role in enhancing cognitive function by ameliorating neurodegenerative pathological features associated with T2DM and obesity. Moreover, the pharmacological properties of this unimolecular dual oxyntomodulin analogue appear to extend beyond metabolic benefits, as suggested by its potential effects on cognitive deficits. This effect may be mediated through the balanced activation of GLP-1R and GCGR pathways.

Fig. 8.

Immunohistochemical staining for neuronal nuclei (NeuN) and MAP2 in db/db, db/m, mazdutide-LD, mazdutide-MD, mazdutide-HD, and dulaglutide groups. (a, c) Representative immunohistochemical staining slices in the whole hippocampus (scale bar = 400 μm, 100× magnification) and its magnified CA1, CA3, and DG regions (scale bar = 50 μm, 400× magnification). (b, d) Quantitative analysis results of NeuN and MAP2 density (% of control) in the all groups (n = 4). ∗p < 0·05, ∗∗p < 0·01, ∗∗∗p < 0·001 compared with db/db model group; #p < 0·05 compared Mazdutide with Dulaglutide group.

Mazdutide protects against myelin decline induced by T2DM and obesity

Myelination plays a crucial role in motor learning, adaptively responsive to sensory cues based on environmental feedback. The proper insulation and trophic support for axons provided by myelination are essential for the nervous system function, meanwhile, myelin remodelling is tightly associated with the increase of myelin sheaths in the adult CNS.29, 30, 31, 32 Myelin basic protein (MBP), as the marker of myelination, was utilised to characterise the myelin alterations during T2DM and obesity in db/db mice following treatment with mazdutide. Results in Supplementary Figure S3a showed an apparently reduction of MBP-positive signals in the hippocampus and cortex of db/db model group. However, long-term mazdutide was associated with alleviation of demyelination in a dose-dependent manner, with Mazdutide-HD showing a significant increase in MBP density (ANOVA + Tukey's, p < 0·0001, p < 0·0001, p < 0·0001, p = 0·0003, Supplementary Figure S3b–e). Additionally, the MBP-positive area was significantly higher in the Mazdutide-HD-treated group compared to the dulaglutide group (ANOVA + Tukey's, p = 0·030, p = 0·023, p = 0·040, Supplementary Figure S3c–e). Notably, demyelination was observed in the spinal cord through LFB staining. In contrast, mazdutide treatment was associated with more neatly arranged myelin sheaths, suggesting that less demyelination occurred in mazdutide groups than in the db/db group (Supplementary Figure S3f). Recent studies suggest that protecting the integrity of myelin could be a potential target to delay the development and slow progression of AD.33

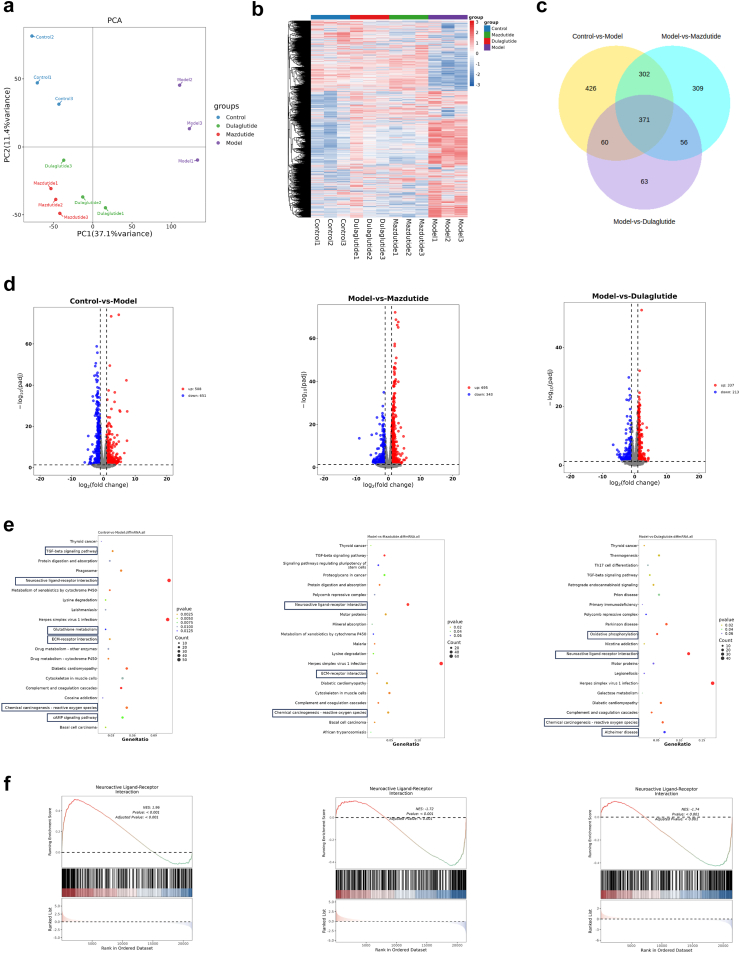

Mazdutide and dulaglutide induce the alteration of transcriptional profile in DACD

After confirming the long-term physiological characteristics of diabetes and obesity, to investigate the underlying mechanism of mazdutide, we performed bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) to assay its effect on gene expression with |log2FC| ≥ 1 and p < 0·05 as strict criteria to identify differential genes in the hippocampus of db/db, db/m, dulaglutide, and Mazdutide-HD mice, and heatmap was established to identify and correlate changes of the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between several groups. Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed that there was a significant difference in gene expression related to T2DM or obesity, as expected, that control db/m group formed a distinct cluster from model db/db group (Fig. 9a), which indicated that DACD was associated with alterations in the transcriptional profile of db/db mice. Notably, we found that a large number of genes were markedly differentially expressed in model db/db group (Fig. 9b). The heatmap showed that the administration of Mazdutide-HD or dulaglutide resulted in a significant divergence in drug effects compared to the db/db group. The gene expression results of DEGs were determined by Venn diagram, and there were some common and different genes in Control, Model, Mazdutide and Dulaglutide groups (Fig. 9c). Upon further analysis, we observed the apparently gene expression changes in Fig. 9d with 508 exhibiting up-regulation and 651 exhibiting down-regulation between Control and Model groups. Specifically, 695 upregulated genes and 343 downregulated genes were identified in mazdutide compared to Model group. And dulaglutide treatment affected 550 DEGs with 337 upregulated and 213 downregulated genes were detected, when comparing with Model group. The number of DEGs in mazdutide-treated group was much higher than that in dulaglutide-treated group, suggesting that mazdutide may have had a greater effect on modulating cognition-associated brain transcription than dulaglutide.

Fig. 9.

Transcriptomic analysis reveals an abundance of gene profiles across the disease spectrum of hippocampus in DACD. (a) Principal component analysis (PCA) of Control, Model, Mazdutide, and Dulaglutide. (b) Heatmap of the gene expression profile in all groups. (c) Venn diagram of DEGs (Control vs. Model), DEGs (Model vs. Mazdutide), and DEGs (Model vs. Dulaglutide). (d) Volcano plots depicting the numbers of up-regulated (red) and down-regulated (blue) DEGs between Control vs. Model, Model vs. Mazdutide, and Model vs. Dulaglutide. (e) The top 20 KEGG terms of DEGs between Control vs. Model, Model vs. Mazdutide, and Model vs. Dulaglutide. (f) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) for KEGG in Model, Mazdutide, and Dulaglutide groups in certain pathways. n = 3.

GO enrichment was performed to characterise significant alterations of biological process of DEGs induced by T2DM and mazdutide treatment (Supplementary Figure S4a). The most abundant DEGs were obtained in Control vs. Model, and the collagen-containing extracellular matrix process, amide transport process, inhibitor activity process, and regulation of feeding behaviour were main biological processes. Surprisingly, consistent enrichment pathway in collagen-containing extracellular matrix process, regulation of peptidase activity processes was mainly enriched in db/db vs. mazdutide. Regulation of oxidoreduction-driven active transmembrane transporter activity and feeding behaviour, besides collagen-containing extracellular matrix process, were enriched in Dulaglutide group when comparing to db/db group. It is noteworthy that collagen-containing extracellular matrix processes were enriched in all three comparisons, indicating that mazdutide and dulaglutide treatment may have influenced collagen-containing extracellular matrix process in T2DM or obesity-associated cognition in db/db mice.

According to KEGG pathway analysis, many of the upregulated genes in Model group were related to neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway (Fig. 9e) that's one of the most significantly enriched pathways related with AD, suggesting that neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction signalling pathway was also closely associated with DACD, which may be linked to disrupted neural function. The dysfunction of neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway affected the physiological and behavioural responses, including cognition, emotion, and motor control involving the transmission and regulation of neurotransmitter signals.32 Besides, we also found long-term T2D and obesity leading to DACD was closely associated with inflammatory pathways, such as Tgf-β signalling pathway and ECM-receptor interaction pathway. Similarly, these pathways were also enriched in model vs. mazdutide groups. In contrast, Parkinson and Alzheimer disease pathways were associated with dulaglutide treatment. To further explore the alterations of pathway, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was conducted to show the opposing trend in the comparative groups with a significance threshold of p < 0·05 with |NES| > 1. Results demonstrated that DACD is involved in multiple disease processes, primarily including neural excitability abnormalities induced by neurotransmitter signalling dysregulation and neuroinflammation. Treatment with mazdutide and dulaglutide exhibited polyvalent regulatory effects on neurotransmitter system homoeostasis and inhibitory effects on neuroinflammation. As shown in Fig. 9f, the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway was significantly upregulated in the Model group. After mazdutide and dulaglutide treatment, most of the upregulated genes showed a clear callback trend. Although cAMP signalling pathway was enriched in the model group compared to control group, the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factors (BDNF) was down-regulated, and the expression of BDNF was significantly increased after mazdutide treatment (Supplementary Figure S4b). This suggests that mazdutide promotes the survival of nerve cells.

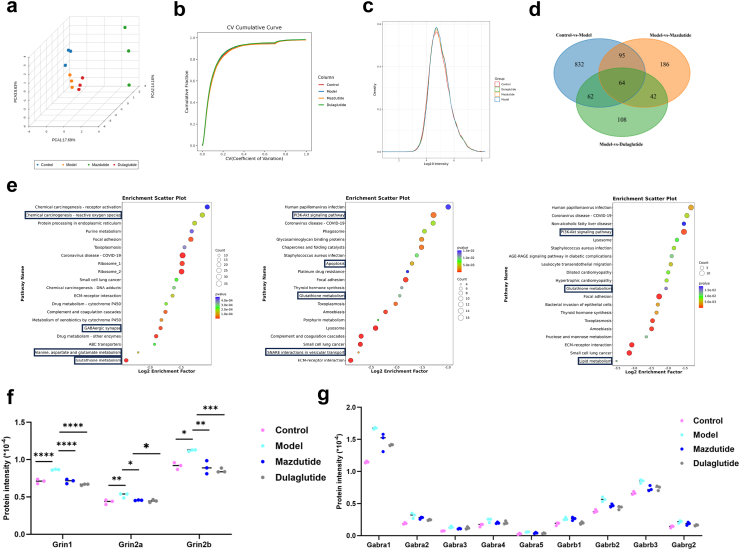

Mazdutide and dulaglutide induce proteomic changes in db/db mice further reveals important signalling pathway

Transcriptome analysis reveals that DACD induces multiple pathological processes, including neurotransmitter signalling dysregulation and neuroinflammation. Liquid chromatography (LC) coupled with data-independent acquisition (DIA) mass spectrometry (MS) was conducted to quantify proteins, resulting in the quantification of a total of 8308 proteins. Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed a clear separation between the Model and Control groups, with the protein pattern partially reversed by mazdutide treatment (Fig. 10a). The coefficient of variance (CV) cumulative curve and unimodal distributions of protein intensities indicated a high degree of reproducibility and no detectable protein degradation (Fig. 10b and c). Differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) were identified using criteria of fold change (FC) > 1·5 and p-value < 0·05. Venn diagram analysis showed that 1053, 387, and 276 DEPs were detected in the comparisons of Control vs. Model, Model vs. Mazdutide, and Model vs. Dulaglutide, respectively (Fig. 10d). Similarly, significant alterations in the protein profile occurred in db/db mice, and mazdutide was associated with the differential expression of more proteins than dulaglutide.

Fig. 10.

Proteomic analysis reveals the potential regulatory role of mazdutide and dulaglutide on DACD. (a) PCA shows a clear separation among Control, Model, Mazdutide, and Dulaglutide groups. Each n = 3. (b) Coefficient of Variation (CV) represented better repeatability within groups. (c) The unimodal distributions of the protein intensities suggest no obvious degradation in samples. (d) Venn diagram of DEPs (Control vs. Model), DEPs (Model vs. Mazdutide), and DEPs (Model vs. Dulaglutide). (e) The top 20 KEGG terms of differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) between Control vs. Model, Model vs. Mazdutide, and Model vs. Dulaglutide. (f, g) Protein quantification analysis for NMDAR and GABAA. n = 3. ∗p < 0·05, ∗∗p < 0·01, ∗∗∗p < 0·001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0·0001.

We subsequently investigated the impact of these DEPs on DACD-associated biological processes and the efficacy of mazdutide and dulaglutide in mitigating cognitive impairment. GO enrichment analysis in Supplementary Figure S5a was conducted to identify significant candidate DEPs induced by DACD. Our observations revealed that most upregulated DEPs were primarily involved in sensory perception of smell, G protein-coupled receptor signalling, glutathione metabolism, and neurotransmitter uptake processes in the Control vs. Model group. In the Model vs. Mazdutide group, enriched biological processes included regulation of sensory perception of smell, G protein-coupled receptor signalling, positive regulation of integrin-mediated signalling pathways, protein polymerisation, and protein-containing complex assembly. Distinctly enriched processes in the Model vs. Dulaglutide group encompassed positive regulation of muscle cell differentiation and brain development. Notably, both mazdutide and dulaglutide were implicated in regulating G protein-coupled receptor signalling processes and positively regulating integrin-mediated signalling pathways. However, mazdutide was uniquely associated with regulation of smell dysfunction, a process linked to early indicators of prodromal neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease.34

KEGG enrichment analysis in Fig. 10e indicated that DACD significantly altered glutathione metabolism, focal adhesion, GABAergic synapse function and ECM-receptor interaction. Notably, similar pathways, including focal adhesion, ECM-receptor interaction, and glutathione metabolism, were enriched in both the Mazdutide and Dulaglutide treatment groups. Furthermore, the PI3K-Akt signalling pathway was significantly enriched by both mazdutide and dulaglutide, ameliorating DACD by mediating neuronal survival and reducing amyloidβ-plaque deposition.35 Interestingly, GSEA results also suggested that the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway was significantly upregulated in the Model relative to Control group, which was consistent with our transcriptomic analysis (Supplementary Figure S5a). We found the levels of NMDA receptor (NMDAR) was significantly increased in model group, including Grin1, Grin2a, and Grin2b, but this trend was remarkably reversed by mazdutide and dulaglutide, suggesting that excitotoxicity caused by overactivation of NMDAR is associated with neuronal death in AD brain. Meanwhile, we also observed GABAergic receptors were consistently upregulated in model compared to control group, mazdutide and dulaglutide decreased the expression of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-related genes (Fig. 10f and g). In addition, our results showed that mazdutide down-regulates SNARE interactions in vesicular transport pathway and apoptosis-related pathway compared with the model group, such as apoptosis pathway and p53 signalling pathway (Supplementary Figure S5b). Taken together, these findings suggested that long-term diabetes and obesity pathophysiological states affected abnormal neurotransmitter uptake and transmission, as well as neuronal excitatory/inhibition processes related to subsequent oxidative stress and inflammatory response. Mazdutide and dulaglutide treatment may have ameliorated cognitive dysfunction through multiple common regulatory pathways, potentially involving GLP-1R activation in the progression of DACD. However, the specific mechanistic differences between the dual GLP-1/GCGR agonist, mazdutide, and GLP-1 mono-agonist, dulaglutide are worthy of further exploration.

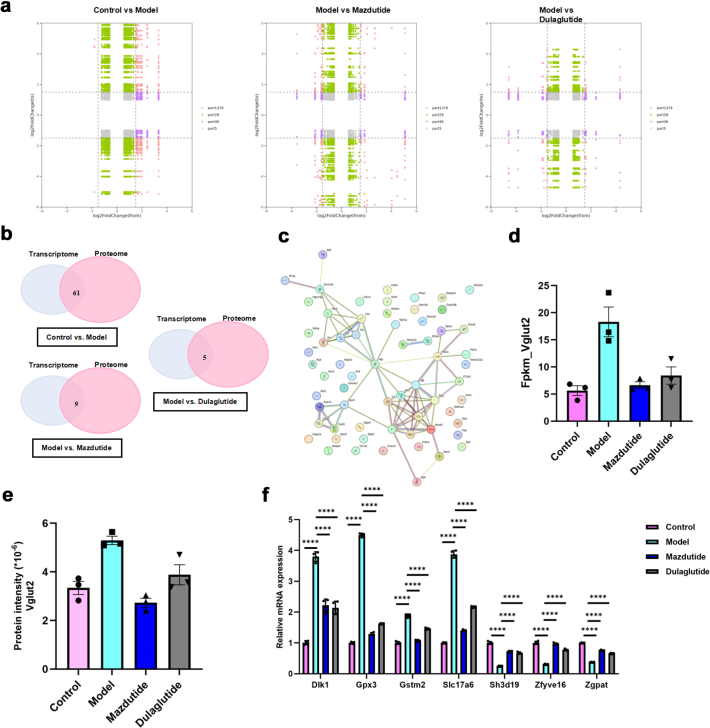

Integrated transcriptomic and proteomic analysis uncover mazdutide's specific regulatory process associated with neurotransmitter signalling

Previous data indicate that mazdutide is associated with improvements in DACD, and many common enriched pathways in transcriptomics and proteomics data consistently suggested pluripotent regulatory mechanisms between mazdutide and dulaglutide were largely due to the activation of GLP-1R. To further elucidate the specific regulatory mechanism of mazdutide distinct from dulaglutide, we analysed the key regulatory pathways and potential targets across Control vs. Model, Model vs. Mazdutide, and Model vs. Dulaglutide comparisons using integrated transcriptome and proteome data. These targets were further categorised into nine regions based on their expression patterns to reveal complex correlation between the alterations of mRNA and protein expression identified in transcriptomic and proteomic datasets. We observed consistent expression profiles between genes and proteins, encompassing commonly upregulated and downregulated genes/proteins in part 3 and part 7 of nine-quadrant plot (Fig. 11a). The common genes/proteins were provided in Supplementary Table S1. We identified 61, 9, and 5 co-differentially expressed targets with consistent regulatory profile in Control vs. Model, Model vs. Mazdutide, and Model vs. Dulaglutide groups by intersecting DEGs and DEPs from transcriptome and proteome profiles (Fig. 11b, Supplementary Table S1). Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis using the STRING database (http://string-db.org/) pinpointed densely connected regions (Fig. 11c). In the network, we found Gstm2 and Vglut2 were upregulated in Model relative to Control groups and reversed by mazdutide, whereas GPX3 and Hp (Haptoglobin) were reversed by dulaglutide. The GO terms of Gstm2 and Vglut2 were related to glutathione transferase activity and neurotransmitter loading into synaptic vesicle, which was closely associated with neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway. The GO terms of Gpx3 and Hp were related to response to oxidative stress and antioxidant activity. These results suggested that mazdutide may have preferentially regulated neurotransmission dysfunction associated with neurotoxicity through balancing the activation of GLP-1 and GCGR effect compared to dulaglutide. Transcriptomic and proteomic profiling consistently identified Vglut2 as a key downregulated target in mazdutide-treated mice, with reductions of 70% (mRNA) and 37% (protein) in the mice brain compared to the DACD model group (Fig. 11d and e). Notably, mazdutide exhibited stronger Vglut2 suppression than dulaglutide, a GLP-1R mono-agonist, suggesting synergistic benefits of dual receptor activation. Both mazdutide and dulaglutide can exert neuroprotective effects by regulating the PI3K-Akt signalling pathway. This is consistent with previous studies (which largely rely on GLP-1 receptor activation).36 RT-qPCR results in Fig. 11f suggested that candidate genes were more potently regulated by mazdutide in DACD, potentially linked to GCGR activation. In addition, mazdutide affected the balance of glutaminergic system which widely involved in synaptic plasticity and neurological disorders. Glutamate as key regulatory substance is widely involved in the metabolism of glutathione, transmission of neurotransmitter, energy metabolism as well as antioxidative effect, which further suggests multiple regulatory mechanisms of mazdutide in modulating the excitatory/inhibitory balance in DACD progression. The correlation of Vglut2 with multiple pathways such as nicotine addiction, synaptic vesicle cycling, retrograde endogenous cannabinoid signalling, and glutamatergic synapses not only underscores its pivotal roles in the strength and direction of synaptic transmission within the nervous system but also offers valuable insights into synergistic effect of downregulating Vglut2 and NMDA genes by mazdutide alleviates excitotoxicity to sustain balanced excitation-inhibition balance.

Fig. 11.

Integrated analysis of proteomics and transcriptomics data. (a) Nine-quadrant plot shows the correlation of gene expression alterations between the mRNA and protein levels. (b) A Venn diagram shows the common DEPs and DEGs with consistent regulatory profile. (c) Protein network showing the protein–protein interactions (PPIs) between the 51 DEPs constructed using STRING software. (d, e) Transcriptomic analysis of Vglut2 mRNA levels and proteomic quantification of Vglut2 protein levels across experimental groups. (f) RT-qPCR was used to validate consistent DEGs and DEPs, which was reversed by Mazdutide or Dulaglutide compared to Model group (n = 4). ∗∗∗∗p < 0·0001.

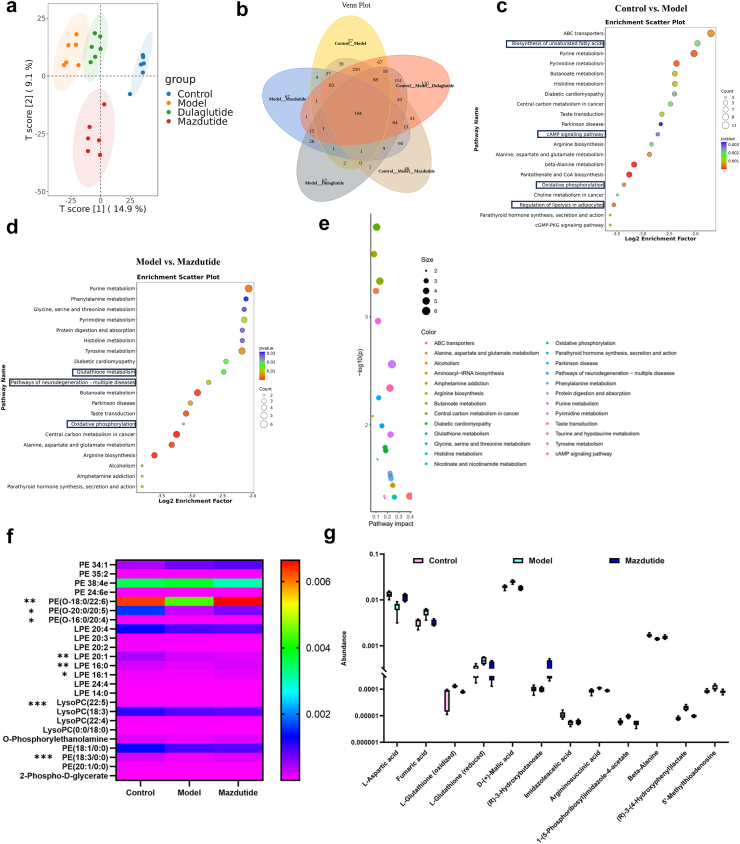

The untargeted metabolomics revealed that potential metabolic biomarkers of mazdutide

After identifying key targets regulated by mazdutide and dulaglutide, metabolomics analysis was utilised to identify and compare the differentially accumulated metabolites (DAMs) and metabolic profiles among mazdutide, and dulaglutide. Firstly, we examined the data with PCA to obtain the general metabolic trend. A total of 3272 annotated metabolites were detected (number of ESI+ and ESI− ions was 1779 and 1723, respectively). As Fig. 12a and b shown, Control, Model, Mazdutide, and Dulaglutide groups were separated by OPLS-DA and data were in 95% confidence intervals. Similar patterns or characteristics were observed in the metabolic profiles between the Mazdutide and Control groups. However, a distinct separation between mazdutide and dulaglutide suggests that the metabolic states of Mazdutide group were significantly different from the db/db model group. A total of 732 annotated metabolites were selected between Model and Control group. Relative to Control vs. Model group, 507 and 568 annotated metabolites were screened in Model vs. Mazdutide and Model vs. Dulaglutide, respectively (Supplementary Table S2). The metabolomics showed that mazdutide was enriched in cAMP signalling pathway after treatment, suggesting that mazdutide does have the properties of GLP-1 agonist, which may activate the expression of cAMP/PKA signalling regulation Vglut2 and improve synaptic plasticity (Fig. 13).

Fig. 12.

The untargeted metabolomics revealed potential metabolites of candidate targets regulated by mazdutide. (a) PCA showed that Control group, Model group, Mazdutide group, and Dulaglutide group were well distinguished. (b) A Venn diagram shows DEMs in different groups. (c, d) The top 20 KEGG terms of DEMs between Control vs. Model and Model vs. Mazdutide. (e) KEGG pathway enrichment and impact score distribution for selected pathways in Model vs. Mazdutide groups. (f) The altered metabolites with a VIP value exceeding 1.0 were selected and visualised using a heat map. (g) Potential metabolic biomarkers were screened by mazdutide in corresponding enriched pathways (n = 6). ∗p < 0·05, ∗∗p < 0·01, ∗∗∗p < 0·001.

Fig. 13.