Summary

Esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) is a highly lethal cancer of the upper gastrointestinal tract with rising incidence in western populations. To decipher EAC disease progression and therapeutic response, we perform multiomic analyses of a cohort of primary and metastatic EAC tumors, incorporating single-nuclei transcriptomic and chromatin accessibility sequencing along with spatial profiling. We recover tumor microenvironmental features previously described to associate with therapy response. We subsequently identify five malignant cell programs, including undifferentiated, intermediate, differentiated, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and cycling programs, which are associated with differential epigenetic plasticity and clinical outcomes, and for which we infer candidate transcription factor regulons. Furthermore, we reveal diverse spatial localizations of malignant cells expressing their associated transcriptional programs and predict their significant interactions with microenvironmental cell types. We validate our findings in three external single-cell RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and three bulk RNA-seq studies. Altogether, our findings advance the understanding of EAC heterogeneity, disease progression, and therapeutic response.

Keywords: esophageal adenocarcinoma, gastrointestinal cancer, computational biology, epigenetics, transcriptomics, spatial transcriptomics, single cell, oncology, bioinformatics

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Multi-omics reveals five distinct malignant programs in esophageal adenocarcinoma

-

•

Malignant programs exhibit unique chromatin accessibility and epigenetic plasticity

-

•

Spatial mapping reveals distinct tumor-microenvironment interactions and programs

-

•

Malignant programs correlate with clinical stages and therapy responses in patients

Yates and Mathey-Andrews et al. dissect the cellular and spatial heterogeneity of esophageal adenocarcinoma across clinical stages. They identify five malignant cell programs with distinct transcriptomic and epigenetic profiles, linked to disease progression, prognosis, and immune response. These programs interact with the tumor microenvironment, highlighting potential therapeutic targets.

Introduction

Esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) is believed to arise from Barrett’s esophagus, an uncommon metaplastic condition.1,2,3,4,5,6,7 EAC is exceptionally lethal, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 5% for patients with non-resectable disease or detectable metastases, representing over half of diagnosed patients.7,8 The recalcitrant and heterogeneous response to treatment underscores the need to understand EAC progression at a cellular level and delineate malignant cell and tumor microenvironment (TME) heterogeneity in therapy-resistant and metastatic settings.4,9

While recent studies explored EAC at single-cell resolution to identify candidate immune and stromal cell types relevant to pathogenesis,9,10 malignant cell states and their heterogeneity in EAC across disease stages—crucial for predicting disease progression, metastasis, and therapeutic response—remain largely undetermined.11,12 Moreover, epigenetic heterogeneity, vital for understanding malignant cell plasticity,12 as well as spatial relationships between distinct cell types and states, remains unexplored in EAC. Given recent advances of single-cell and spatial transcriptomics (ST) technologies,13,14,15 we hypothesized that joint inference of transcriptional, epigenetic, and spatial heterogeneity in EAC across disease stages, metastatic foci, and therapeutic exposures may provide insights into programs dictating lethal disease. Our analysis uncovered malignant cell programs and their spatial localizations and interactions with microenvironmental cell types that inform EAC disease progression and therapeutic resistance.

Results

Characterizing the transcriptional and chromatin accessibility landscape of primary and metastatic EAC

In our discovery cohort, we analyzed 13 biopsies from therapy-naive and therapy-exposed patients with EAC. Multiome sequencing (single-nuclei RNA sequencing [snRNA-seq] and single-nuclei assay for transposase-accessible chromatin [ATAC] sequencing [snATAC-seq]) was performed on samples from 10 patients. Visium ST was conducted on a subset of 5 matched samples from 3 patients (Figures 1A and S1; Table S1; STAR Methods). Additionally, Xenium ST was performed on 6 samples from 3 patients and on 10 samples from 3 additional patients profiled exclusively using Xenium (Figures 1A and S1; Table S1; STAR Methods). OncoPanel18 analysis provided genomic profiling data for seven patients, revealing that all were mismatch repair proficient but exhibited a heterogeneous genetic background. Recurrent genetic alterations included TP53 mutations (5/7 patients), CDKN2A mutations (3/7), and amplifications in KRAS (3/7) and CDH4 (3/7) (Tables S2, S3, S4, and S5).

Figure 1.

EAC primary and metastatic samples show a diverse landscape of TME and malignant cells in transcriptomic and epigenetic data

(A) Schematic representation of the study workflow. Biopsies from 10 patients in our discovery cohort, including normal adjacent tissue (NAT), primary tissue, and metastatic samples, were subjected to single-nuclei RNA and ATAC sequencing using 10X Chromium technology. For a subset of these patients as well as three additional patients, matched primary and metastatic samples were profiled with 10X Visium and 10X Xenium spatial transcriptomics (ST) technologies. For single-nuclei data, cells were annotated by cell type and categorized into malignant and TME components. TME subtypes were linked to metastasis, with validation against an external pan-cancer fibroblast atlas.16 The malignant cell components underwent analysis using consensus non-negative matrix factorization (cNMF) to uncover malignant programs, which were further characterized for transcriptional and epigenetic heterogeneity at a single-cell and spatial level and candidate master transcription factors. External validation was performed in two single-cell validation cohorts,9,10 and associations with clinical and molecular characteristics, as well as survival, were assessed in three bulk validation cohorts.7,10,17

(B) Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) representation of the full cohort in Harmony-corrected integrated transcriptomic data, with major cell type compartments labeled and cell counts indicated.

(C) Proportion of major cell types in each sample based on transcriptomic data, with percentages for compartments representing over 5% of the total sample composition.

(D) UMAP representation of the full cohort in Harmony-corrected integrated ATAC data, with cell type annotations transferred from the RNA annotations. “NA” denotes cells without paired associated RNA information.

(E) Proportion of major cell types in each sample based on ATAC data, with percentages for compartments representing over 5% of the total sample composition.

After preprocessing, we identified 70,658 high-quality cells with expression information for 21,444 genes within the snRNA-seq data and 33,705 cells with chromatin accessibility information for 311,978 genomic regions within the snATAC-seq data, represented for visualization purposes only in Harmony19-corrected space (STAR Methods; Figures 1B–1E and S1). Seven major cellular compartments were delineated: carcinoma, epithelial/nerve, myeloid, muscle, fibroblast, and lymphoid, for which we uncovered various cell subtypes (Figures 1B and S2). Malignant cells represented an average of 54% of all cells across tumor samples (interquartile range: 48%–63%; Figure 1C).

The EAC TME contains distinct macrophage, lymphoid, and fibroblast populations

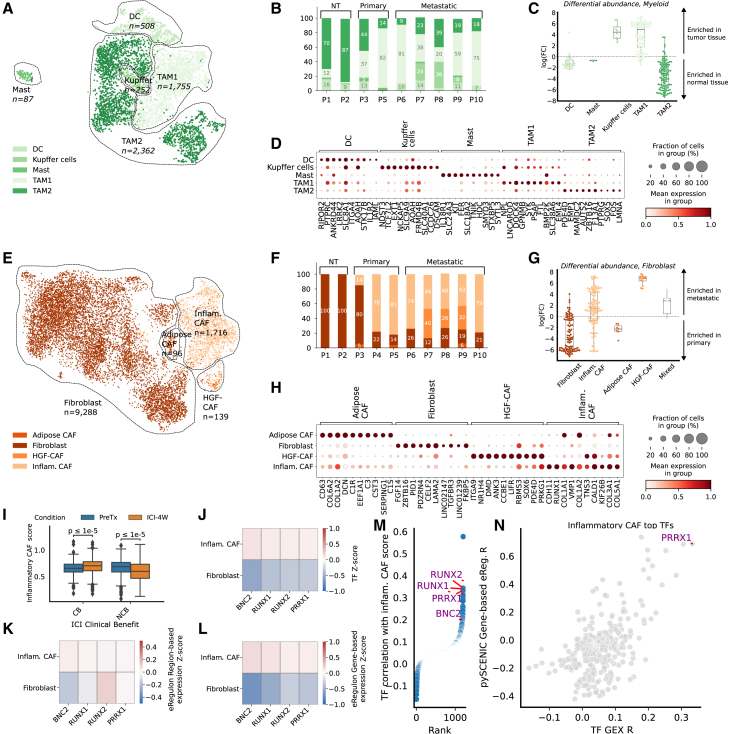

Although the response of EAC to immunotherapy can vary, recent studies have demonstrated that specific myeloid cell subtypes within EACs are associated with the effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs).9 We found 5 distinct cell subtypes within the myeloid compartment, including two tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) populations (TAM1 and TAM2; Figures 2A and 2B). TAM1 cells, exhibiting pro-inflammatory gene expression patterns,21,22,23 were significantly enriched in tumor samples, whereas TAM2 cells, exhibiting characteristics of anti-inflammatory macrophages,24,25 were differentially enriched in normal adjacent tissue though still detectable in tumor tissue (one-sample t tests p < 0.0001) (Figure 2C).20

Figure 2.

The EAC TME contains several pro- and anti-inflammatory populations of macrophages and RUNX1/RUNX2/PRRX1/BNC2-regulated inflammatory cancer-associated fibroblasts enriched in metastatic samples

(A) Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) representation of the myeloid compartment in Harmony-corrected integrated transcriptomic data, with annotated subtypes indicated.

(B) Proportion of myeloid subtypes per patient.

(C) Distribution of Milo20 fold change scores between normal-adjacent and tumor samples for myeloid cells; Milo scores measure differential abundances of specific cell subtypes by assigning cells to overlapping neighborhoods in a k-nearest neighbor graph.

(D) Marker genes of annotated myeloid subtypes, with cells grouped by subtype and expression information provided.

(E) UMAP representation of the fibroblast compartment in Harmony-corrected integrated transcriptomic data, with annotated subtypes indicated.

(F) Proportion of fibroblast subtypes per patient.

(G) Distribution of Milo fold change scores between metastatic and primary tumor samples for fibroblast subtypes, with labeling and exclusion criteria similar to (C).

(H) Marker genes of annotated fibroblast subtypes, with cells grouped by subtype and expression information provided.

(I) Distribution of the inflammatory cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF) score in the stromal compartment of Carroll et al.’s9 cohort, stratified by response to immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy: clinical benefit (CB) and no clinical benefit (NCB). The inflammatory CAF program is scored on the entire cohort. Paired measurements of patients were made before treatment (PreTx) and after a 4-week ICI treatment window (ICI-4W). The distribution of the inflammatory CAF score is compared among the CB and NCB groups across PreTx and ICI-4W time points. Significance testing is conducted using a Mann-Whitney test to assess differences between the CB and NCB groups.

(J–L) Results for SCENIC+-derived transcription factor (TF) candidates for inflammatory fibroblasts, with cells grouped by subtype and Z scores of TF expression (J), eRegulon gene-based expression (K), and eRegulon region-based expression (L) are shown.

(M) TF gene expression correlation with inflammatory CAF score in the external pan-cancer fibroblast validation cohort of Luo et al.,16 with candidate TFs identified with the SCENIC+ analysis highlighted.

(N) Correlation of all available TFs’ gene expression and SCENIC-estimated gene-based eRegulon score with the inflammatory CAF score in the pan-cancer fibroblast atlas.16 Only PRRX1’s eRegulon activity, but not BNC2 and RUNX1/2, was estimated using SCENIC.

These TAM subpopulations resembled previously described populations in the pan-cancer tumor-infiltrating myeloid cell atlas26 and a study in EAC by Carroll et al.9 (Figure S3). Importantly, the TAM1 cells resembled the TAMs from the latter study, linked to higher monocyte content and selective ICI response. In contrast, TAM2 appeared similar to the M2 macrophages from the same study, linked to lower monocyte content and resistance to ICI.

Lymphoid cells in the TME also play a critical role in therapy response and cancer progression.27,28,29 Within the lymphoid compartment, we identified five distinct subtypes: B cells, CD4+ T cells (TCD4+), CD8+ T cells (TCD8+), regulatory T cells (Tregs), and natural killer cells (Figure S2). B cells, which have been recently linked to ICI response through their involvement in forming tertiary lymphoid structures,30,31 were notably depleted in metastatic samples (one-sample t test p < 0.001, Figure S2). This aligns with previous findings in melanoma32 and colorectal cancer,33 where B cell depletion is linked to enhanced tumor growth and metastasis. Given their connection to tertiary lymphoid structures and their impact on ICI response, strategies aimed at restoring or modulating B cell populations may hold potential for improving immunotherapy efficacy in EAC.

Finally, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) have also been previously implicated in tumor progression and therapy resistance.34,35 We identified four distinct CAF populations in our cohort (Figures 2E and 2F), including an inflammatory CAF population (iCAF) (expressing e.g., CDH11, RUNX1, and COL1A1) enriched in metastatic EAC tumor samples and non-activated fibroblasts displaying relative abundance in primary EAC tumors (one-sample t test p < 0.0001) (Figures 2G and 2H; STAR Methods).20 These CAF populations were also consistently recovered in external pan-cancer and EAC-specific cohorts, encompassing a total of 246 tumor samples (Figure S4).9,16

We next examined whether the presence of iCAFs correlated with selective ICI response in an external cohort.9 Among the non-clinical benefit (non-CB) patient group (defined as the group of patients showcasing less than 12 months of progression-free survival), there was a significant decrease in iCAF gene signature scores following ICI treatment consistent across patients. In contrast, a minimal increase in the iCAF score (that was inconsistent across patients) was observed pre- and post-ICI in the clinical benefit (CB) group (Figures 2I and S4).

Leveraging our paired snRNA-seq/ATAC-seq data, we used SCENIC+36 to identify candidate master transcription factor (mTF) regulons associated with the iCAF population.36 RUNX1, RUNX2, PRRX1, and BNC2, previously implicated in various oncogenic processes,37,38,39,40,41 were nominated as candidate mTFs of these cells (Figures 2J–2L) and further corroborated within the external pan-cancer CAF atlas16 (Figures 2M and 2N). Notably, attempts to link the iCAF-identified mTFs to ICI response revealed no strong associations, primarily due to high dropout rates. This finding further emphasizes the value of using cell subtype signatures over individual genes (Figure S4).

Overall, distinct macrophage, lymphoid, and CAF cells associated with therapy response populate the microenvironment of both primary and metastatic EAC.

Five malignant cell programs are identified across primary and metastatic EAC tumor samples

In contrast to TME investigations, tumor-intrinsic cellular programs relevant to progression, metastasis, and therapy resistance in EAC remain poorly understood.11,12,42 To uncover unique gene activity programs operant among the EAC tumor compartment, we employed consensus non-negative matrix factorization (cNMF) and identified five cNMF programs consistently present across different patients (cNMF1 to cNMF5) (Figures 3A–3C; STAR Methods). We conducted gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) to assess enrichment of established biological pathways from MSigDB within the five cNMF malignant cell programs and then compared the identified programs with the pan-cancer tumor cell programs from Gavish et al.42 and the Barrett’s esophagus programs described by Nowicki-Osuch et al.1 (Figures 3D and S5).

Figure 3.

Five recurrent transcriptomic programs characterize EAC malignant cells with distinct RNA profiles

(A) Illustration of the methodology employed for identifying transcriptomic programs. For each patient, consensus non-negative matrix factorization (cNMF) is performed on the malignant cell compartment, followed by manual filtration to retain high-quality programs characterized by gene weightings. Pairwise cosine similarity between programs across all patients is computed to cluster programs using hierarchical clustering with average linkage.

(B) Cosine similarity matrix representing the similarity between cNMF-derived programs across all samples, clustered using hierarchical clustering with average linkage. The five identified programs (cNMF1 through cNMF5) are delineated.

(C) UMAP representation of the malignant cell compartment using unintegrated transcriptomic data, colored according to their program score (cNMF1 through cNMF5) and sample ID.

(D) GSEA enrichment of the five programs in the 50 hallmarks of cancer, based on genes ranked according to their weight contribution to cNMF programs. Hallmarks are grouped according to category. Enrichments that did not reach significance (FDR = 0.05) are blanked out.

(E) GSEA enrichment plots for selected programs described by Nowicki et al. in Barrett’s esophagus.

(F) GSEA enrichment plots for hallmarks G2M checkpoint in cNMF2 and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in cNMF3.

(G) Distribution of the five program scores in metastatic and primary samples. Significance is computed using the Mann-Whitney U test. The difference in median score is indicated as Δ.

(H and I) Cosine similarity between programs derived with cNMF in external datasets and cNMF1 through cNMF5 programs, derived in the Carroll et al. dataset (H) and in the Croft et al. dataset (I). The cosine similarity is computed between the cNMF-derived gene weights of programs for all patients in the external datasets and the median gene weight associated with each cNMF program derived in the discovery set.

cNMF1 resembled the intermediate columnar profile in Barrett’s esophagus1 (normalized enrichment score [NES] = 2.5, false discovery rate [FDR] q < 0.0001; Figure 3E) and showed enrichment in MYC targets, oxidative phosphorylation, and MTORC1 signaling pathways, akin to previously described Gavish et al.’s programs “EMT-III” and “Interferon/MHC-II (II).” cNMF2 exhibited properties consistent with a cell cycling program (NES = 2.5, FDR q < 0.0001; Figure 3F), reminiscent of Gavish et al.’s program “Cell cycle G2/M.” cNMF3 resembled a classical epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) program (NES = 2.0, FDR q < 0.0001; Figure 3F), enriched in EMT and WNT beta-catenin pathways, aligned with Gavish et al.’s program “EMT-I.” cNMF4 resembled the differentiated Barrett’s esophagus program (NES = 3.8, FDR q < 0.0001; Figure 3E),1 displayed enrichment in tumor necrosis factor, interferon-gamma, and interferon-alpha signaling, and appeared similar to Gavish et al.’s programs “PDAC-classical,” “PDAC-related,” and “Epithelial senescence.” Finally, cNMF5 resembled the undifferentiated Barrett’s esophagus program (NES = 2.6, FDR q < 0.0001; Figure 3E).

Moreover, cNMF4 (differentiated esophagus program) was significantly enriched in malignant cells of primary EAC tumors (difference in median score between primary and metastatic malignant cells Δ = −0.35, p < 0.0001), while cNMF5 (undifferentiated esophagus program) exhibited a slight enrichment in malignant cells of metastatic EAC samples (Δ = 0.07, p < 0.0001) (Figure 3G).

To validate the robustness of the malignant cell cNMF programs uncovered in our study, we similarly performed cNMF on two external single-cell datasets sourced from Croft et al.10 and Carroll et al.,9 across an aggregate of 6,838 malignant cells from 17 patient tumors. In the Carroll et al. dataset, we identified several programs consistent with cNMF1, cNMF2, cNMF4, and cNMF5; moreover, in the Croft et al. dataset, we observed enrichment of cNMF1, cNMF3, and cNMF4 programs, supporting the generalizability of the identified malignant cell programs across datasets (Figures 3F, 3G, and S5).

The five malignant cell programs displayed differential chromatin accessibility patterns and epigenetic plasticity

We next leveraged the paired snRNA-seq/ATAC-seq data to interrogate the connection between observed transcriptional programs and epigenetic diversity, aiming to decipher whether distinct EAC malignant cell programs correspond to specific chromatin accessibility patterns (Figure 4A). We correlated the score of malignant cNMF programs with the normalized ATAC peak counts and identified significant associations between all cNMF programs and differentially accessible chromatin regions, denoted as cNMF-related peaks (Figure 4B). We uncovered distinct chromatin accessibility patterns across cells representing cNMF programs (200 top-scoring cells, STAR Methods), with several genes of interest displaying differential promoter accessibility, including AKT2,43 MKI67,44 SPARC,45,46 BHLHE41,47,48 and ANXA1149 (Figures 4C and 4D). These variations in promoter and enhancer accessibility suggest a potential functional link between epigenetic alterations and evolution trajectories of tumor cells. Of note, cNMF1, cNMF2, and cNMF3 generally displayed less distinct chromatin accessibility profiles than cNMF4 and cNMF5 (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

EAC malignant cell programs display unique ATAC profiles and epigenetic plasticity

(A) UMAP representation of the malignant cell compartment using unintegrated snATAC-seq data, color-coded according to their cNMF gene signature score (cNMF1 through cNMF5) and sample ID. The program score is transferred from the RNA annotation.

(B) Number of open chromatin regions significantly correlated with each program (FDR < 0.05, Pearson’s R > 0.1).

(C) Heatmap illustrating chromatin accessibility in cNMF-associated regions for representative program cells. Cells are scored using cNMF signatures derived from RNA, with the top 5% unique cells in each score selected as representative cells. The top 200 regions with the higher correlation between chromatin accessibility and each program are represented.

(D) Chromatin accessibility of representative cNMF program cells for genes of interest. Genes are selected based on their association with the regions of the highest correlation between chromatin accessibility and gene signature scores of cNMF programs. Chromatin accessibility of promoters for AKT2, MKI67, SPARC, BHLHE41, and ANXA11 is depicted for representative cells of cNMF1 through cNMF5 and all remaining carcinoma cells.

(E) This heatmap illustrates the accuracy of classifying cells into cNMF programs based on chromatin accessibility profiles. Cells are scored using the average Z score of chromatin accessibility across the top 200 cNMF-associated regions, and the highest score determines their chromatin accessibility identity. Each point represents the percentage of cells with a given transcriptional identity (e.g., cNMF3) classified under a specific chromatin accessibility identity (e.g., cNMF1). Off-diagonal points indicate cells whose transcriptional and chromatin accessibility identities differ, suggesting potential plasticity or transitions between programs.

(F) Distribution of the epigenetic plasticity scores across representative cells of cNMF1 to cNMF5. Average Z scores of ATAC accessibility vectors are transformed into a probability distribution using a softmax transformation with temperature, and the plasticity score is computed as the Shannon entropy over the resulting probability distribution.

(G) Representation of the candidate master transcription factors (mTFs) associated with programs consistent across datasets. We jointly model chromatin accessibility and gene expression to obtain candidate master transcription factors for each cNMF program in the discovery cohort that are subsequently validated in the two external validation cohorts. The identified mTFs consistent across datasets are represented.

Epigenetic plasticity, particularly the modulation of chromatin accessibility in malignant cells, is a recognized hallmark of cancer.50 To determine if the identified cNMF programs exhibited chromatin states that facilitate transcriptional program diversity (epigenetic plasticity, as defined by Burdziak et al.51), we compared the paired transcriptional gene expression and chromatin accessibility profiles among malignant cells. Additionally, we analyzed the distribution of epigenetic plasticity scores within the malignant cells representing each cNMF program (Figures 4E and 4F; STAR Methods).

We assigned cells two identities, a transcriptional identity based on the highest score of signature genes and a chromatin accessibility identity based on the expression of cNMF-related peaks. Cells with strong cNMF4 and cNMF5 signature scores (within the top 5% of score distribution; STAR Methods), representing differentiated and undifferentiated programs, respectively, exhibited mostly concordant transcriptional gene expression and chromatin accessibility identities, as well as low epigenetic plasticity, consistent with the hypothesized stable identity of these programs (Figures 4E and 4F). Conversely, cells from the cell cycling program, cNMF2, displayed discordant expression of chromatin accessibility patterns characteristic of different programs along with high epigenetic plasticity.52,53 cNMF1 also displayed high epigenetic plasticity, and certain malignant cells expressing the program had chromatin accessibility profiles that also associated with cNMF4 and cNMF5, consistent with the proposed intermediate nature of cNMF1 between the continuum represented by cNMF5 and cNMF4 programs (Figures 4E and 4F).

Furthermore, cells within the EMT-like cNMF3 program displayed mixed chromatin accessibility identity and high epigenetic plasticity, consistent with previous observations of EMT state plasticity and its reversible nature.54,55 Based on the snATAC-seq scores, i.e., the average Z score of normalized counts over cNMF-related peaks, we speculate that cNMF3 cells predominantly originate from the cNMF1 and cNMF5 pools rather than the cNMF4 pool, potentially suggesting that terminally differentiated EAC cells do not undergo EMT (Figure 4E).

Predicted transcription factor regulons of the malignant cell programs

To ascertain whether the identity of malignant cell cNMF programs was governed by a specific set of mTFs, we next inferred the gene regulatory network underlying cell programs in our dataset leveraging the paired multiome data with SCENIC+36 and also evaluated these findings in the external Croft el al. and Carroll et al. datasets for reproducibility (STAR Methods; Figures 4G and S6).

Candidate mTFs included E2F756 for cNMF2; ZEB1,57,58 TCF7L1,59 and MAFB60,61 for cNMF3; FOXO1 and FOXO3,62 MXD1,63,64 LCOR,65,66 CREB3L1,67,68,69 MAFK,70 PPARD,71,72 and HNF4A1,73,74,75 (tumor suppressor transcription factors [TFs] and/or associated with favorable prognosis) for cNMF4; and MECOM76,77 and HMGA278,79 for cNMF5. Notably, no mTF was robustly identified across datasets for cNMF1. We therefore identified a set of candidate mTFs reproducibly associated with each malignant cell program except cNMF1 in three independent datasets (summarized in Figure 4G). Lastly, the expression of genes coding for candidate mTFs identified for cNMF4 and cNMF5 was analyzed along the axis of expression of these two hypothesized opposing programs by ranking cells according to their relative cNMF4 to cNMF5 expression. The mTFs showed a consistent positive and negative gradient of expression along the cNMF5 to cNMF4 axis (Figure S6), supporting their role in orchestrating these program expressions.

Malignant and TME cell programs in EAC display differential spatial enrichment in defined tumor regions

To assess whether the malignant cell programs identified in the snRNA-seq data exhibit spatial heterogeneity within individual EAC tumor samples, we performed Visium and Xenium ST on additional EAC tissue from matched patients (STAR Methods). For Visium samples, we categorized ST spots into pure tumor regions, mixed regions containing both malignant cells and TME cells in similar proportions, or regions of normal tissue, using CNV (copy-number variation) profiles inferred from the spatial data (STAR Methods, Figures 5A and S7). Deconvoluted ST spot cell type proportions and gene expression80 broadly agreed with CNV assignments (Figures S7 and S8).We scored the five malignant cell cNMF programs based on the corrected, deconvoluted carcinoma-specific gene expression matrix and found that they displayed distinct spatial distributions within the EAC tumor samples (Figures 5A and S7).

Figure 5.

Single-nuclei-derived transcriptional programs highlight different spatial regions of EAC tumors

(A) Spatial transcriptomics (ST) slides of P8 primary tumor A, colored according to cNMF program score and the CNV-derived label. For each spot, we infer the CNV profile with inferCNV and assign spots to tumor, mixed, and normal status. cNMF scores are computed as the average Z score of signature genes using the deconvolved carcinoma-specific gene expression profile of spots derived with Cell2Location.

(B) Average cNMF score according to the position of the spots compared to the tumor-leading edge. For each tumor spot, we compute the distance to the edge as the shortest path to a normal or mixed spot. The distribution of cNMF scores with standard error is represented for normal spots, mixed spots, and spots of a certain distance to the edge.

(C) cNMF scores for carcinoma cells and cell type annotations in a subset of Xenium-profiled samples (P4_A, P11_B, and P12_D). cNMF scores are computed as the average Z score across all carcinoma cells of signature genes included in the Xenium panel.

(D) CellCharter cluster assignments for a subset of Xenium-profiled samples (P4_A, P11_B, and P12_D).

(E) CellCharter cluster cell type proportion: each cell is assigned a cluster and we represent the proportion of the different cell types in each of the CellCharter clusters.

(F) Distribution of cNMF scores of carcinoma cells belonging to the CellCharter clusters with a substantial amount of carcinoma cells (>5%), CC1, CC2, CC3, and CC4. For all comparisons, Mann-Whitney U p < 0.000005.

In most samples, cNMF1 was primarily expressed in the tumor core, characterized by greater distances from the periphery, while cNMF4 was more localized at the tumor edge (Figure 5B). The spatial distribution of cNMF5 and cNMF2 varied, whereas cNMF3, which was less frequently detected in snRNA-seq, was expressed in only three samples (P8_A, P8_B, and P5) and exhibited a scattered enrichment pattern across the tumor (Figures 5A and S7). To further validate the spatial organization of these programs, we analyzed Xenium-profiled data (which allows for true single-cell resolution) from 16 samples spanning six patients, including three profiled exclusively with Xenium. Using canonical marker analysis, we annotated cell types and scored cNMF programs in carcinoma cells (STAR Methods). The cNMF programs showed distinct spatial localization within the tumor, consistent with the Visium data (Figures 5C, S9, and S10). Notably, cNMF4 and cNMF5 were strongly expressed in specific tumor regions and were often co-expressed in regions with high cNMF1 expression, reinforcing its intermediate identity. cNMF2-expressing cells were frequently clustered in small regions of cycling cells, whereas cNMF3-expressing cells were more diffusely distributed across the tumor, except in localized areas, consistent with the Visium data observations.

To systematically identify shared spatial niches within tumors, we applied the CellCharter (CC) method,81 which uncovered eight distinct CC clusters (CC1–CC8) across all 16 samples, each enriched in specific cell types and exhibiting distinct spatial patterns (Figures 5D, 5E, and S10). Clusters CC1, CC2, CC3, and CC4 represented carcinoma cells with varying degrees of non-malignant cell infiltration (carcinoma content 8%–87%; Figure 5E). CC1 was composed mostly of carcinoma cells, CC2 showed infiltration by myeloid, stromal, and T cells, CC3 contained both carcinoma and normal epithelial cells with some immune infiltration, and CC4 was highly infiltrated with stromal and myeloid cells. The remaining clusters displayed <5% of carcinoma cells. CC5, CC6, and CC7 represented stromal and immune niches, with CC5 enriched in myeloid cells, CC6 dominated by stromal cells, and CC7 enriched in stromal and B cells. Finally, CC8 represented a normal epithelial cell niche (Figure 5E).

We next examined whether carcinoma cells in different spatial niches expressed distinct cNMF programs (Figure 5F; for all comparisons, Mann-Whitney U p < 0.000005). In clusters highly infiltrated with immune cells (CC2 and CC4), carcinoma cells exhibited strong expression of the cNMF3 programs, while cells in the pure carcinoma cluster (CC1) showed similar levels of all programs except cNMF3. The CC3 cluster displayed high expression of both cNMF1 and cNMF4, consistent with the proposed differentiated identity of cNMF4, which may reflect early EAC cells clustering with normal epithelial cells. Interestingly, CC3 was frequently located at the tumor margin (Figures 5F and S10), aligning with the Visium findings that cNMF4 expression is enriched at the tumor edge.

These results demonstrate that malignant cell programs exhibit distinct and reproducible spatial patterns within EAC tumors. Similarly, stromal, lymphoid, and myeloid programs identified earlier also showed distinct spatial localization within EAC tumors, as shown by deconvolution estimates in Visium-profiled samples and the distribution of non-malignant CC clusters in Xenium-profiled samples (Figures 5D, S8, and S10). Among stromal programs, RUNX1 expression closely aligned with the iCAF score in the Visium data, whereas other candidate mTFs showed weaker correlations (Figure S8). However, in the sparse Xenium data, none of these candidate mTFs showed substantial expression. These findings establish RUNX1 expression as a marker for iCAFs and suggest its role in regulating this population. Together, these results confirm the existence of distinct tumor microenvironment programs and their spatial compartmentalization within EAC tumors.

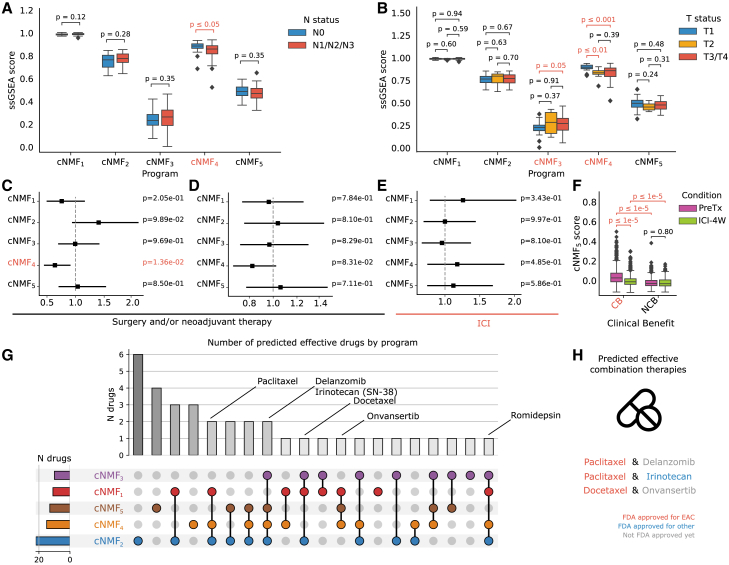

Malignant cell programs in EAC correlate with clinical characteristics, patient prognosis, and predicted drug sensitivity

We then sought to determine whether any of the identified malignant cell cNMF programs were associated with distinct clinical prognostic stages and therapeutically relevant states. By projecting these programs into the primary EAC The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) cohort, we observed that cNMF4 was significantly linked with lower T and N stages, whereas cNMF3 exhibited a moderate association with higher T stages, consistent with its EMT-like nature82 (Figures 6A and 6B). Other programs did not display significant associations with these clinical stages, and no malignant cell program showed significant associations with M staging (Figure S11).

Figure 6.

Discovered malignant programs have different clinical characteristics and predicted drug sensitivity

(A and B) Link between uncovered programs and (A) N stage, i.e., proxy of the number of nearby lymph nodes that have cancer, and (B) T stage, i.e., size and extent of the main tumor in the TCGA bulk cohort.7 Patients are scored using single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) with a cancer-specific gene signature. Statistical testing is performed using the Mann-Whitney U test.

(C–E) Hazard ratio associated with scores in bulk validation cohorts of (C) TCGA, (D) Hoefnagel et al., and 17 (E) Carroll et al.9 Cox proportional hazard univariate models are employed using disease-specific survival for TCGA and overall survival for Hoefnagel et al. and Carroll et al. The p values are estimated using the Wald test.

(F) Distribution of the cNMF5 score in the malignant cell compartment of Carroll et al.’s cohort,9 stratified by response to immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy: clinical benefit (CB) and no clinical benefit (NCB). The cNMF5 program is scored on the full cohort. Paired measurements of patients were made before treatment (PreTx) and after a 4-week ICI treatment window (ICI-4W). The distribution of the cNMF5 score is compared among the CB and NCB groups across PreTx and ICI-4W time points. Significance testing is conducted using a Mann-Whitney U test.

(G) Predicted drug sensitivity by program. scTherapy is used to infer which drugs may be effective against EAC cells exhibiting specific tumor programs. The upset plot represents the total number of drugs predicted to target cells expressing a specific program on the left, as well as the size of the intersection represented in the middle on the top. Drugs of interest are indicated on the plot.

(H) Selected predicted candidate combination therapies that could target cells in all five programs at a time are represented.

We also investigated whether the identified malignant programs were linked to specific mutations in TCGA dataset. Among these, cNMF1 scores were significantly elevated in patients with non-silent somatic mutations in CDKN2A (Figure S11). However, no significant associations were observed for the other cNMF scores, suggesting that highly recurrent somatic mutations observed in EAC are unlikely to be the primary drivers of cNMF program abundance.

We then investigated the relationship between the malignant cell programs and patient survival using a univariate Cox proportional hazard model in two external bulk EAC patient cohorts treated with conventional therapies, namely surgery and neoadjuvant chemotherapy (TCGA7 and Hoefnagel et al.17), and one external EAC patient cohort treated with ICI (Carroll et al.9) (STAR Methods). Higher cNMF4 scores were predictive of improved patient survival in the first two patient cohorts exposed to conventional therapies (p = 0.01 and p = 0.08, respectively), but not in the third patient cohort exposed to ICI (p = 0.49) (Figures 6C–6E). The association of cNMF4 with less aggressive clinical features in this context is consistent with other program-specific features previously shown (i.e., enrichment in primary tumors, differentiated transcriptional profile, and link to TFs associated with improved patient prognosis).

Finally, we investigated whether the cNMF programs displayed differential enrichment in therapy exposure categories of the external EAC patient cohort treated with ICIs. We assessed the distribution shift of the cNMF5 gene signature score in Carroll et al.’s single-cell data and observed that the score was high in patients experiencing CB to ICI both pre- and post-ICI exposure compared to non-CB patients (Mann-Whitney U p < 1e−5, Figure 6F). In addition, the cNMF5 program gene signature score was significantly lower post ICI exposure only in patients experiencing a CB (Figure 6F). These patterns were consistent on a per-individual patient sample basis (Figure S11).

To assess whether the identified programs are associated with differential sensitivity to existing therapies, we used scTherapy83 to predict drug responses in EAC cells expressing each program. Our analysis revealed a broad spectrum of predicted sensitivities, with cNMF2-expressing cells responsive to the largest number of compounds and cNMF3-expressing cells exhibiting the lowest overall drug sensitivity (Figure 6G). Notably, no single drug was predicted to target EAC cells in all five programs simultaneously; however, delanzomib, a next-generation proteasome inhibitor84; romidepsin, an HDAC inhibitor85; and SN-38, the active metabolite of irinotecan and a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved chemotherapy previously shown to have potential in EAC86; were the only agents predicted to affect four out of five programs (Figure 6G; Table S6).

Leveraging these predictions, we identified potential combination therapies by pairing drugs that together putatively target all five cNMF programs (Figure 6H). Among these combinations, some included FDA-approved chemotherapy agents for EAC, such as paclitaxel and docetaxel. Specifically, the combination of paclitaxel with delanzomib84 or with irinotecan86 was predicted to effectively target all five programs. Additionally, the combination of docetaxel and onvansertib, a Polo-like kinase 1-selective therapeutic recently granted FDA fast-track designation for metastatic colorectal cancer,87 also emerged as a potential therapeutic strategy.

Thus, in aggregate, the cNMF programs identified in our study exhibited distinct associations with patient survival, therapy exposure status in external EAC cohorts, and predicted drug sensitivity. Notably, no single agent was predicted to target all five programs simultaneously, highlighting potential resistance mechanisms to standard chemotherapy. Furthermore, these findings pointed to rational combination strategies that could be explored in preclinical models to overcome therapy resistance, offering a potential path toward more effective treatment approaches.

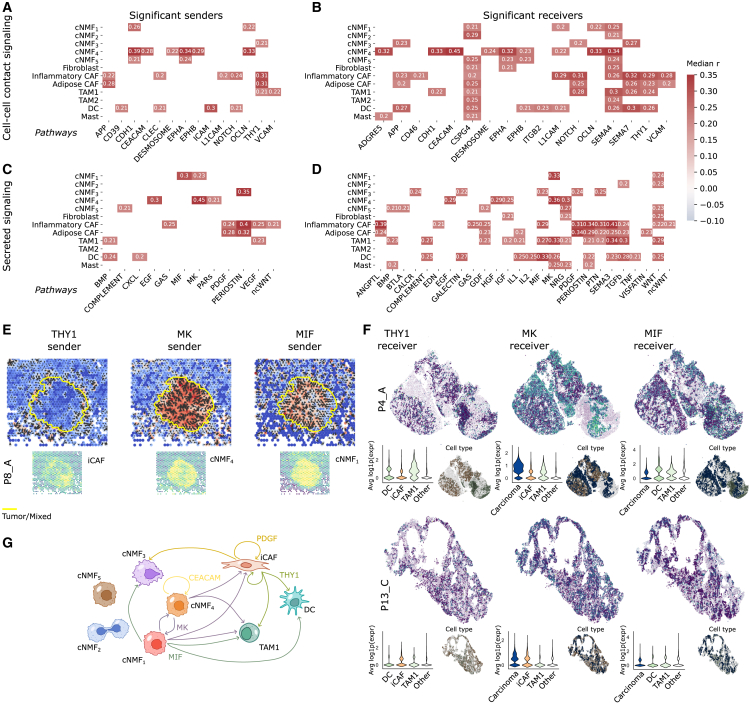

Co-occurring groups of TME cells are linked with malignant cell programs

Lastly, given our findings of the key roles of tumor cell programs in EAC, we sought to understand whether and how the malignant cells interacted with specific TME cells (including the key myeloid and CAF populations described earlier). We first conducted an analysis of ecotypes, i.e., co-occurring abundance of tumor immune and stromal microenvironment cells, as measured in deconvolved data, in EAC.88 Leveraging the external TCGA, Hoefnagel et al., and Carroll et al. EAC patient cohorts (n = 268 patients), we identified two major ecotypes: “immune-desert” (predominantly comprising malignant cells and endothelial cells) and “immune-activated” (featuring a mixture of myeloid, lymphoid, and stromal cells; Figure S12; STAR Methods). A high cNMF3 gene signature score in deconvoluted samples was significantly associated with the immune-activated ecotype across all studies, consistent with findings on Xenium experiments and supporting the role of malignant-stromal and malignant-myeloid interactions in driving EMT89,90,91 (Figure S12). cNMF5 exhibited a significantly lower gene signature score in the immune-activated ecotype in two out of the three external cohorts (Figure S12).

Next, we predicted signaling interactions between malignant cells and TME cells using ST data (STAR Methods).92 Malignant cells exhibited predicted interactions with all TME compartments, with the strongest signals (i.e., highest impact on gene expression as predicted by node-centric expression models; STAR Methods) involving myeloid and lymphoid cells (STAR Methods; Figure S12).9 To explore spatially activated signaling pathways, we performed computational cell-cell interaction analyses, assessing ligand-receptor interactions from cell-cell contact within 200 μm and secreted ligand-receptor interactions within 400 μm (STAR Methods; Figures 7A–7E).93 This analysis revealed numerous autocrine and paracrine signaling pathways associated with malignant and TME program expression. For instance, CEACAM signaling was predominantly produced and received by cNMF4-expressing cells, suggesting a self-reinforcing loop, while platelet-derived growth factor signaling was secreted primarily by CAFs and strongly received by both CAFs and cNMF3-high malignant cells (Figures 7A–7D).

Figure 7.

Uncovered malignant programs show associations with clinical and molecular characteristics, prognosis, and distinct ecotypes

(A–D) Pathways significantly correlated with TME and malignant programs. Using COMMOT, sender and receiver activity scores were assigned to each spot for specific pathways and correlated with program scores. The heatmap displays the median Pearson’s r across samples for pathways significantly correlated with a program in at least 4/5 samples; (A) and (B) depict significant sender and receiver signals for cell-cell contact pathways, while (C) and (D) show significant signals for secreted pathways.

(E) Directionality of THY1, MK, and MIF signaling in sample P8_A. Spots are colored based on sender activity for each pathway, with arrows indicating the estimated direction of signaling. Yellow outlines mark tumor/mixed tissue boundaries. Bottom graphs display program scores significantly correlated with THY1, MK, and MIF sender signals.

(F) Receiver activity of the THY1, MK, and MIF pathways in two Xenium samples (P4_A and P13_C). The top illustrates the average expression of receptor genes included in the Xenium panel. The left inset shows the distribution of average receptor gene expression across relevant cell populations, while the right inset highlights cell types predicted to participate in these pathways based on COMMOT analysis.

(G) Schematic representation of inferred interactions between malignant cells expressing cNMF programs and iCAFs, TAM1 macrophages, and DCs. Recurrent interactions between cells are depicted with colored arrows.

Among contact-dependent signaling pathways, THY1 signaling was particularly enriched in iCAFs, with strong receiver activity in iCAFs, TAM1 macrophages, and dendritic cells (DCs) (Figures 7A and 7B). THY1 signaling facilitates leukocyte transmigration via integrin binding and supports immune cell recruitment to inflammatory sites.94,95,96 Thy-1+ CAFs have also been linked to increased collagen deposition, contributing to extracellular matrix stiffness and remodeling, which may alter TME architecture.97 We also identified significant midkine (MK) signaling activity, with strong sender activity in cNMF1- and cNMF4-expressing regions and receiver activity in these populations and myeloid-rich areas (Figures 7C and 7D). MK signaling was spatially enriched within tumor regions, though no consistent signaling directionality was observed (Figure 7E). Given MK’s known role in tumorigenesis, its expression by malignant cells may drive immune-tolerant macrophage activation and promote an inflamed but ICI-resistant TME.98,99,100,101

Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) signaling was also highly active, with cNMF1-expressing cells acting as major senders and cNMF3-high cells, iCAFs, TAM1 macrophages, and DCs showing strong receiver activity (Figures 7C and 7D). MIF expression was concentrated within tumor regions (Figure 7E), aligning with its established role in promoting gastric and other carcinomas,102,103,104 as well as driving tumorigenesis through chronic inflammation and immune evasion.105,106

We validated these interactions using the Xenium-profiled data, analyzing genes from the Xenium panel (Figure S13). Cells predicted to interact through the THY1, MK, and MIF pathways frequently showed close spatial proximity (Figures 7F and S10). Moreover, these cells consistently displayed strong receiver activity. Across samples, iCAFs, TAM1 macrophages, and DCs exhibited robust expression of THY1 receptor genes; carcinoma cells, iCAFs, and TAM1 macrophages expressed MK receptor genes; and carcinoma cells, TAM1 macrophages, and DCs expressed MIF receptor genes (Figures 7F and S13). Of the ligands included in the Xenium panel, only THY1 ligand expression could be assessed, and it was consistently overexpressed in iCAFs (Figure S13).

Together, these findings highlight complex and spatially organized signaling networks between malignant cells and the TME, identifying potentially targetable pathways that could influence EAC progression and therapeutic response (Figure 7G).

Discussion

Despite progress in dissecting EAC and Barrett’s esophagus biology, as well as relating biological programs to selective therapeutic response across treatment modalities, the complexities of its malignant cell compartment, epigenetic variations, and disease progression remain poorly understood. Leveraging a multi-modal profiling strategy across primary and metastatic EAC samples, our study unveiled considerable heterogeneity within and between tumors. In addition to identifying previously described myeloid and stromal compartments, this study defines EAC malignant cell heterogeneity across primary and metastatic sites in distinct clinical settings across transcriptomic, chromatin accessibility, and spatial dimensions. We identified five major malignant cell programs, shared across patients in our study and external EAC patient cohorts, that possessed distinct chromatin accessibility profiles and spatial distributions. Among the programs identified, cNMF5, cNMF1, and cNMF4 delineated a continuum from undifferentiated to differentiated programs, mirroring a trajectory observed in Barrett’s esophagus,1 cNMF2 represented a cell cycling program, and cNMF3 emerged as a rarer EMT-associated program. Furthermore, we identified candidate TFs for various programs and a concordance between transcriptional programs and estimated epigenetic plasticity, contributing to the growing evidence emphasizing the significance of epigenetic plasticity as a facilitator of cancer progression and metastasis through increased heterogeneity.107,108,109,110,111 We highlighted the differential spatial distribution of malignant cell program gene signature scores and the complexity of the tumor ecosystem, further supporting prior studies reporting that malignant cells express distinct cellular pathways at the tumor edge and core.112 Finally, we identified recurrent interactions between cells with high expression of cNMF programs and TME cell types, which could in turn influence therapy response, notably to ICI or targeted therapies that have shown strong dependency to TME cells and malignant cell heterogeneity.113,114,115,116

In particular, the identified association between iCAF presence and ICI response suggested potential mechanisms through which iCAFs may mediate immune evasion. iCAFs secrete cytokines (e.g., interleukin-6) and chemokines (e.g., CXCL9 and CXCL10) that recruit various immune cells to the TME, including immunosuppressive populations such as Tregs and myeloid-derived suppressor cells, as well as cytotoxic CD8+ T cells.117,118,119 During ICI therapy, the resulting immune-activated environment may reduce immunosuppressive populations, indirectly destabilizing iCAFs by disrupting their interactions with other TME components. Additionally, ICI treatment could promote the repolarization of iCAFs into other fibroblast subsets.118 In patients where iCAF depletion occurs, the loss of these cells may hinder the influx of peripheral CD8+ T cells and weaken support for pre-existing CD8+ T cells, contributing to poor ICI outcomes in non-CB patients. Given the enrichment of iCAFs in metastatic tissue and their association with ICI response, future studies could investigate their potential role in this process. Furthermore, recent work has highlighted the heterogeneity of iCAFs, revealing multiple potential origins120 and diverse spatial distributions.121 These findings underscore the complex role of iCAFs in shaping immune responses and modulating ICI efficacy.

Broadly, our study underscores the clinical importance of tumor cell heterogeneity in primary and metastatic EAC, elucidating the association of distinct tumor cell states with clinical characteristics, ICI response, and potential TME interplay, marking a key step toward understanding EAC formation and progression.

Limitations of the study

There are several limitations in our study. Firstly, the discovery cohort comprised 10 samples, with 8 being tumor samples, hindering direct linkage between proportions of TME cells and clinical characteristics with malignant cell composition. Consequently, we mostly depended on bulk validation cohorts to further elucidate these associations. Second, sampling and processing biases may affect differential abundance testing and limit the interpretability of the results. Notably, metastatic tumors were obtained from diverse anatomical sites, meaning that observed TME composition differences may reflect site-specific characteristics rather than metastatic status alone. Third, one of the single-cell validation cohorts had very few malignant cells (∼400 cells), suggesting that larger, clinically integrated single-cell EAC cohorts with sufficient malignant cells are needed to further validate our cNMF results. Fourth, the relatively small size of the ST samples necessitates caution in interpreting quantitative conclusions. Fifth, while we obtained somatic panel sequencing data for seven of the eight tumors profiled with snRNA-seq and snATAC-seq, we were unable to generate matched whole-genome or exome sequencing data. As a result, we cannot rule out the potential influence of genetic heterogeneity on cell type composition and malignant program abundance. Sixth, while we used Xenium ST to validate findings from Visium ST, we did not perform immunohistochemistry or immunofluorescence profiling, which would have provided complementary protein-level validation of the transcriptomic data. Seventh, while we proposed candidate combination therapies based on our analyses, we did not experimentally test their efficacy. Lastly, the heterogeneous nature of the cohort, including variations in metastatic status, treatment regimen, and anatomical location, further emphasizes the need for larger and clinically representative molecular cohorts to further investigate the findings from this study.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Eliezer M. Van Allen (EliezerM_VanAllen@dfci.harvard.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

-

•

Raw sequencing data for single-nuclei RNA- and ATAC-seq generated in this study are deposited in the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap/) with accession number phs003438.v1. Processed data are available at the Broad Single Cell Portal (https://singlecell.broadinstitute.org/single_cell) (SCP: SCP3028 and SCP3029). Raw and processed data for Visium and Xenium ST profiled samples are available on Zenodo (https://zenodo.org/): with DOI https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15341263. Existing single-cell and bulk sequencing data can be downloaded from EGA (EGAS00001006468, EGAS00001006469) for Carroll et al.’s paper. Remaining existing single-cell data can be downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) website, accession numbers GSE222078 (Croft et al.) and GSE210347 (Luo et al.). Remaining existing bulk data can be downloaded from the GEO website, accession number GSE207527, for Hoefnagel et al.’s data, and from the UCSC Xena browser for the Cancer Genome Atlas ESCA cohort (https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/?cohort=TCGA%20Esophageal%20Cancer%20(ESCA)&removeHub=https%3A%2F%2Fxena.treehouse.gi.ucsc.edu%3A443). Details on how to download the data used for the analysis are detailed on GitHub: https://github.com/vanallenlab/EAC-multiome. Source data are provided with this paper.

-

•

All the code needed to reproduce this analysis is available on Zenodo (DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15269379) and GitHub at the following address: https://github.com/vanallenlab/EAC-multiome.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Single Cell Core at Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, for performing the multiome snRNA-seq/ATAC-seq sample preparation. They would also like to thank the patients and their families, as well as hospital personnel. Funding sources that supported this project include the Ambrose Monell Foundation (E.M.V.A.), NIH R50CA265182 (J.P.), U2CCA233195 (E.M.V.A.), R01CA227388 (E.M.V.A.), R01CA279221 (E.M.V.A.). T32CA092203 (C.M.-A.), and Swiss National Science Foundation grant number 205321_207931 (J.Y.).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, J.Y., C.M.-A., V.B., and E.M.V.A.; methodology, J.Y., C.M.-A., V.B., and E.M.V.A.; formal analysis, J.Y., V.B., and E.M.V.A.; investigation, J.Y., C.M.-A., S.H., K.B., B.T., S.C., A.K., S.B., S.K.C., Z.L., A.K.R., N.S.S., V.B., and E.M.V.A.; resources, C.M.-A., J.P., A. Gagné, A. Garza, C.H., J.R., E.S., G.B., A.J.A., and M.C.; writing – original draft, J.Y.; writing – review and editing, all authors contributed; visualization, J.Y.; funding acquisition, V.B. and E.M.V.A.; supervision, V.B. and E.M.V.A.

Declaration of interests

E.M.V.A.—advisory/consulting: Enara Bio, Manifold Bio, Monte Rosa, Novartis Institute for Biomedical Research, Serinus Bio, and TracerDx; research support: Novartis, BMS, Sanofi, and NextPoint; equity: Tango Therapeutics, Genome Medical, Genomic Life, Enara Bio, Manifold Bio, Microsoft, Monte Rosa, Riva Therapeutics, Serinus Bio, Syapse, and TracerDx; travel reimbursement: none; patents: institutional patents filed on chromatin mutations and immunotherapy response, and methods for clinical interpretation; intermittent legal consulting on patents for Foaley & Hoag; editorial boards: Science Advances.

A.J.A. has consulted for Anji Pharmaceuticals, Affini-T Therapeutics, Arrakis Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Kestrel Therapeutics, Merck & Co., Inc., Mirati Therapeutics, Nimbus Therapeutics, Oncorus, Inc., Plexium, Quanta Therapeutics, Revolution Medicines, Reactive Biosciences, Riva Therapeutics, Servier Pharmaceuticals, Syros Pharmaceuticals, T-knife Therapeutics, Third Rock Ventures, and Ventus Therapeutics. A.J.A. holds equity in Riva Therapeutics and Kestrel Therapeutics. A.J.A. has research funding from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Deerfield, Inc., Eli Lilly, Mirati Therapeutics, Nimbus Therapeutics, Novartis, Novo Ventures, Revolution Medicines, and Syros Pharmaceuticals.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT in order to improve readability and language. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

Experimental model and study participant details

Patients samples

The 13 patient samples (eleven tumor tissue and two non-paired normal adjacent tissue) were collected with written informed consent and ethics approval by the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board under protocol numbers 14–408, 03–189, or 17-000. The nomenclature designates: normal adjacent tissue samples as P1 and P2; primary tissue samples as P3, P4, and P5; metastatic samples as P6, P7, P8, P9, and P10; and samples exclusively profiled with Xenium P11, P12, and P13. There were two female and 11 male patients, ages 36 to 78 (average 61 years). Four patients were treatment-naïve while nine had received prior treatment. Further patient details are provided in Table S1.

Method details

Patient tissue sample collection and dissociation for multiome snRNA-seq/ATAC-seq

Nuclei isolation was performed on frozen biopsy specimens as previously described.122 Low-retention microcentrifuge tubes (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA) were used throughout the procedure to minimize nuclei loss. Briefly, patient tissue was separated from optimal cutting temperature (OCT) by removing the OCT with sharp tweezers and scalpels. Tissues were then manually dissociated into a single-nuclei suspension by chopping the tissue with fine spring scissors for 10 min, homogenizing in TST solution, filtering through a 30 μm MACS SmartStrainer (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany), and centrifuging for 10 min at 500 g at 4C. The resulting nuclei pellet was resuspended in a lysis buffer to permeabilize the nuclei before centrifuging again for 10 min at 500 g at 4C. The final nuclei pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of 10x Genomics Diluted Nuclei Buffer and trypan blue-stained nuclei were counted by eye using INCYTO C-Chip Neubauer Improved Disposable Hemacytometers (VWR International Ltd., Radnor, PA, USA).

Approximately 16,000–25,000 nuclei per sample were loaded per channel of the Chromium Next GEM Chip J for processing on the 10x Chromium Controller (10x Genomics, Pleasanton, CA, USA) followed by transposition or cDNA generation and library construction according to manufacturer’s instructions (Chromium Next GEM Single Cell Multime ATAC + Gene Expression User Guide, Rev F). Libraries were normalized and pooled for sequencing on two NovaSeq SP-100 flow cells (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

snRNA and snATAC multiome processing

snRNA-seq and snATAC paired data preprocessing

The paired snRNA-seq and snATAC-seq samples were sequenced using Illumina HiSeq X. Subsequently, the raw bcl files were aligned to the human reference genome GRCh38 for each sample via Cell Ranger Arc 2.0.

snRNA-seq specific processing and cell type annotation

To mitigate potential ambient RNA contamination within the RNA assay of the multiome data, we used Cellbender123 to computationally remove ambient RNA counts from each count matrix.

After, Scrublet124 was employed to identify cell barcodes that may be potential doublets from the ambient RNA-adjusted RNA count matrices, and these barcodes were subsequently removed. The resulting doublet-free ambient RNA-adjusted count matrices were then employed for further downstream analyses.

RNA assay quality control procedures were conducted for each individual patient sample using Scanpy.125 Cell barcodes with fewer than 200 unique genes expressed, genes expressed in fewer than three cells, and cell barcodes exhibiting greater than 20% of all RNA expression counts mapped to mitochondrial genes (pctMT) were filtered out. RNA expression per cell was normalized via counts per 10k (CP10k), i.e., dividing the counts by the library size of the cell and normalizing to 10,000 total counts per cell, followed by log(x+1) transformation. After performing Leiden clustering (resolution = 0.7) on the 15-nearest neighbor graph of the RNA assay per individual patient sample, component cell types were manually annotated by evaluating canonical marker gene expression per cluster identified through differential expression (DE) utilizing the overestimated variance t-test.

The copy number variation (CNV) profile of each cell per individual patient sample was computed utilizing a Python implementation of InferCNV (https://github.com/icbi-lab/infercnvpy), employing a mixture of non-malignant cells as a reference (annotated fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and immune cells) based on their presence in the sample. Cells were clustered according to their CNV profile using Leiden clustering, with clusters labeled as malignant or non-malignant depending on their average CNV score. Subsequently, cells were assigned a malignant or non-malignant status based on their cluster membership per individual patient sample.

Refinement of cell type annotation was performed by analyzing cells from all patients of a single type after integration. For each major TME cell type (T/NK, myeloid, endothelial, fibroblast, muscle), cells having a relatively lower pctMT (<15%) were further analyzed downstream. We strengthened the pctMT threshold only in the TME compartment, as malignant and epithelial cells can display higher basal levels of mitochondrial counts.126 Cells were subsetted per cell type and all cells of the same type were integrated using Harmony,19 followed by Leiden clustering to obtain subclusters. The integration was performed on a cell-type level rather than on the full set of cells to obtain more fine-grained integration. Manual annotation of subclusters was carried out using marker genes identified through differential gene expression with an overestimated variance t-test as before.

Annotations of myeloid cell populations were cross-referenced with pan-cancer myeloid annotations from Cheng et al.,26 while cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF) cells were compared to pan-cancer CAF annotations from Luo et al.16 For visualization only, we integrated the fully annotated cohort using Harmony, opting not to use the cell-type-specific Harmony integration.

snATAC-seq specific preprocessing

The processed snATAC-seq data was acquired utilizing CellRanger Arc 2.0 (snapshot 28). Subsequently, the Signac package was employed for comprehensive processing of the ATAC data127 (https://stuartlab.org/signac/). Adhering to the guidelines outlined in the 10X multiome Signac vignette, the filtered counts and ATAC fragments obtained from CellRanger Arc 2.0 were utilized to re-call peaks using MACS2128 (https://pypi.org/project/MACS2/). Additionally, peaks located in non-standard chromosomes and genomic blacklisted regions were excluded. The consolidated peaks from all samples underwent further filtration, removing those with a width below 20 bp or exceeding 10,000 bp.

Cell type annotations were directly transferred from the snRNA annotations, as the RNA and ATAC measurements were paired. Cells excluded during standard quality control in the RNA measurements but not in the ATAC measurements were annotated as NA. Subsequently, a comprehensive quality control assessment was conducted on the entire set of cells across all samples. Cells with ATAC counts falling below 1000 or exceeding 100,000, a nucleosome signal surpassing 2, a TSS enrichment below 3, or a fraction read in peaks below 0.15 were filtered out.

Normalization of the ATAC count matrix was executed utilizing the term-frequency inverse-document-frequency (TF-IDF) transformation, following default parameters in Signac. Dimensionality reduction was carried out using Latent Semantic Indexing (LSI) with 40 components on the TF-IDF normalized matrix, with UMAP computed on the harmony-corrected LSI components.

snRNA-seq analysis

Differential abundance testing

Differential abundance testing for the myeloid, CAF, and lymphoid compartments was conducted employing the milopy package20 (https://github.com/emdann/milopy). Of note, the sampling bias, i.e., the fact the resection from the tumor tissue and adjacent normal tissue may vary in tissue size and baseline abundance and types of cells across the tissue, as well as the processing bias, i.e., the fact cells differentially suffer from dissociation and processing, might bias differential abundance testing and limit the interpretability of differential abundance results. For the myeloid compartment, differential abundance testing compared normal adjacent tissue with tumor tissue. For the CAF compartment, differential abundance testing compared primary with metastatic tissue. The Milo method was executed on the cell-type specific Harmony-corrected principal components (PC), utilizing a 20-nearest neighbors graph. Neighborhoods were assigned labels through majority voting: if over 60% of cells within a neighborhood belonged to an individual cell type, the neighborhood was labeled accordingly. Otherwise, the label "mixed" was assigned.

Malignant cell program discovery through consensus negative matrix factorization (cNMF) and characterization

To dissect the malignant cell compartment, we employed consensus non-negative matrix factorization (cNMF)129 (https://github.com/dylkot/cNMF) per individual patient sample and then aggregated the results as described below. cNMF was performed on a sample-level rather than on the full cohort to avoid detecting patient-specific programs primarily driven by technical factors such as batch effects or copy-number variation (CNV) profiles. Cells annotated as putatively malignant based on canonical marker gene expression but not from clustering on inferCNVpy copy number score were filtered. For each sample, cNMF was performed on the RNA counts matrix of the 2,000 most highly variable genes, selecting the number of components (k) based on recommended criteria (i.e., inspecting the error and stability plot and picking the smallest k that minimized error while maximizing stability). Density threshold was set to 0.1 for each sample. cNMF programs expressed in too few cells or showing expression of TME-related genes, potentially indicating contamination, were manually removed.

The cNMF gene expression programs generated per individual patient sample were characterized by a vector of weights per gene representing its contribution to the program. These programs were combined across all samples by calculating their pairwise cosine similarity after removing small (high score in <10 of cells) or contaminated programs. Hierarchical clustering with an average linkage method was then applied to group similar programs into five clusters. A cNMF program was defined by the median weight of clustered gene expression programs, with the top 100 contributing genes used as a gene signature for the cNMF program. Cells from all patients were scored for the resulting cNMF gene signatures using the scanpy scoring method, i.e., the average gene expression of signature genes subtracted with the average gene expression of control genes.

The programs were compared to pan-cancer programs described in Gavish et al.42 For each combination of program uncovered in our dataset and program uncovered in the Gavish et al. publication, we computed the fraction of genes that were found in both programs on the number of genes from the Gavish et al. programs captured in our dataset. We also compared the programs to the Barrett’s esophagus programs described by Nowicki-Osuch et al.1 using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA).130 Finally, GSEA130 was run using the prerank function on the ranked list of genes associated with each program, using the hallmarks of cancer as a search database.131

Validation of malignant cell programs in external datasets

In order to assess the reproducibility of the malignant cell cNMF programs identified within our cohort, we conducted a similar analysis on the malignant cell compartment of two external single-cell RNA sequencing studies focusing on esophageal adenocarcinoma: the datasets from Carroll et al.9 and Croft et al.10 Following the methodology outlined in the previous section, we applied cNMF to derive programs for each sample in these external datasets. Subsequently, we computed the cosine similarity between each of these programs and the cNMF programs previously identified in our own dataset. This comparative analysis allowed us to determine the degree of recurrence and consistency of the identified programs across multiple independent datasets.

snATAC analysis and link with snRNA

Link between snRNA and snATAC

To establish a connection between the programs identified in the malignant cell compartment and ATAC peaks, we calculated the Pearson correlation in malignant cells between the TF-IDF-normalized peak accessibility and program score transferred from the snRNA-seq. We then filtered out peaks in the 25% least expressed category in malignant data before performing the correlation computation. Subsequently, we determined the false-discovery rate (FDR) corrected q-value associated with correlation for each peak. Peaks with an FDR q-value below 0.05 and a Pearson correlation coefficient exceeding 0.1 were considered significantly correlated with a specific program.

Representative cells and link between RNA and ATAC identity

To establish the connection between the transcriptomic and epigenetic characteristics of cells, we identified representative cells for each cNMF program. Specifically, we selected cells within the top 5% highest cNMF score for each program, ensuring exclusivity by removing cells that ranked in the top 5% for two or more programs. These cells were designated as cNMF representative cells and were utilized to depict genome tracks surrounding genes of interest. Notably, due to differential recovery rates of ATAC and RNA, the proportion of representative cells with paired ATAC measurements varied.

To characterize the ATAC identity of cells, we identified the top 200 most significantly correlated regions with each cNMF program as cNMF-associated regions. Subsequently, we computed the Z score for each region, estimating the mean and standard deviation across the population of cNMF representative cells. The ATAC data were then scored for each program using the mean Z score of cNMF-associated regions, and each cell was assigned an ATAC identity based on the maximum score. A comparison between RNA and ATAC identities was performed using a confusion matrix.

Drawing inspiration from previous work,51 we assigned a plasticity score to each cell using Shannon’s entropy as a measure of plasticity. We assigned a probability of belonging to a program using a softmax transformation with temperature. Let be the ATAC score associated with cNMFi in cell j; we transformed the score in probability

The temperature parameter T was chosen to optimize the calibration curve associated with RNA and ATAC identity correspondence (Figure S14). The plasticity score of cell j was then computed as

We finally computed the distribution of plasticity scores in the cNMF representative populations.

Spatial transcriptomics (ST) analysis

Visium ST data preparation and sequencing

FFPE-embedded tissue sections of 3–10 μm thickness were sectioned then placed on a slide. H&E staining was performed by Brigham and Women’s Hospital Pathology Department core facility. When available, 2–4 FFPE scrolls of 10–20 μm thickness were collected in microtubes and stored at −200C. RNA quality was assessed using FFPE scrolls or from tissue sections previously placed on a slide by gently removing the FFPE section with a sterile blade and immediately transferring it to a microtube. RNA extraction was carried out using a Qiagen RNeasy FFPE kit. RNA integrity, measured by DV200 value, was determined using the Agilent 4200 TapeStation with RNA High Sensitivity ScreenTape was used. FFPE H&E-stained slides were imaged according to the Visium CytAssist Spatial Gene Expression Imaging Guidelines Technical note. Briefly, using the Leica Aperio VERSA scanner microscope, slides were scanned at 10× magnification. Next, the hardest coverslip was removed, and the sample deparaffinized according to the 10X Genomics Visium CytAssist Spatial Tissue Preparation guide (CG000518 Rev C) and FFPE – deparaffinization and decrosslinking guide (CG000520 Rev B). Hardset coverslips were removed by immersing them in xylene for 10 min, twice for each slide. Then, slides were immersed in 100% ethanol for 3 min, 2 times, followed by immersion in 96% ethanol for 3 min twice and finally in 70% ethanol for 3 min. Slides were incubated overnight at 4°C before proceeding to destaining and decrosslinking according to the guidelines. Next, the slide was placed in the Visium CytAssist Tissue Slide Cassette and destained by incubating on a low profile thermocycler adapter in a thermal cycler (BioRad C1000 Touch) at 420C in 0.1 N HCL. Subsequently, decrosslinking with 10X buffers was performed at 950C for 1 h. All 5 downstream steps were followed according to the Visium CytAssist Spatial Gene Expression User Guide (CB000495, Rev E) including using 6.5 mm × 6.5 mm Visium capture area slides; (1) Probe hybridization; (2) Probe ligation, (3) Probe Release & Extension; (4) Pre-amplification and SPRIselect cleanup; (5) Visium CytAssist Spatial Gene Expression - Probe Based library construction. Visium Human Transcriptome probe set v2.0 used, which contains 18,536 genes targeted by 54,5018 probes. 2.4% (451) of these genes are excluded by default due to predicted off-target activity to a different gene. All cleanup methods were performed using SPRIselect beads (Beckman Coulter), Qiagen EB buffer, and 10X Magnetic separator. Cycle number determination for GEX sample index PCR was performed using Kapa SYBR Fast qPCR Master Mix and qPCR amplification plots were visualized on the 7900HT Real-Time PCR system. Dual Index TS Set A, contains a mix of one unique i7 and one unique i5 sample index was used for sample index PCR. GEX Post-Library Construction QC was performed on Agilent TapeStation DNA High-Sensitivity ScreenTape. Libraries were normalized and pooled for sequencing on NextSeq 150 flow cells (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Xenium ST data preparation

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections (5 μm) from six patients were placed on Xenium slides following the demonstrated protocol guide (CG000578). Deparaffinization and tissue permeabilization were performed according to the 10x Genomics Xenium User Guide (GC000580). Probe hybridization and cell segmentation staining were carried out following the 10x Genomics User Guide (CG000760 Rev B). The hybridized slide was then loaded onto the Xenium Analyzer in accordance with the User Guide (CG000584 Rev G). The 5K Prime Human Pan-Tissue & Pathway Panel was used for this study. Post-Xenium Analyzer run H&E staining was performed according to the demonstrated protocol CG000613.

We acknowledge the Molecular Imaging Core (mic.dana-farber.org) at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute for Xenium staining and imaging.

Visium ST data preprocessing and cell type annotation

Following the Visium spatial transcriptomics sequencing, the raw bcl files were demultiplexed using bcl2fastq and aligned to the human reference genome GRCh38 for each sample via SpaceRanger (v2.1.1). Quality control procedures were conducted individually for each patient using Squidpy.132 Spots with fewer than 5,000 counts, genes expressed in fewer than 10 spots, and spots exhibiting over 30% reads mapped to mitochondrial DNA (pctMT) were filtered out.

The copy number variation (CNV) profile of each cell was computed utilizing a Python implementation of InferCNV (https://github.com/icbi-lab/infercnvpy). To get an initial estimate of malignant versus normal ST spots, used as input to inferCNV, we employed a method inspired from the STARCH method initialization.133 Briefly, we ran PCA on the log(1+CP10K) normalized ST data and clustered the data using K-means (k=2). We assigned the cluster with the highest average expression to the tumor cluster and the remaining cluster to normal. Normal spots are used as reference for the inferCNV algorithm. We then clustered spots according to their CNV profile using Leiden clustering and assigned clusters with a strong CNV profile to tumor spots. Clusters with a similar CNV profile to the tumor spots but with a weaker overall signal were assigned to mixed spots. Finally, spots with no CNV profile or with a CNV profile opposite to the tumor profile were labeled as normal spots. Hence, this procedure yields a refined assignment to spots to mostly tumor, mixed tumor and TME, and mostly TME regions. We further refined the annotations by spatially smoothing annotations: if a tumor or normal spot contained one or zero spots in the 6-nearest neighbors of the same category, the label was reassigned to the majority label of the neighborhood (tumor, mixed, or normal).

We then computed the distance of each tumor spot to the periphery of the tumor using the shortest path to the nearest normal or mixed spot. Spots with a small assigned distance were hence located at the tumor periphery, while spots with a large assigned distance were located at the tumor core.