Abstract

Regulation of a profession is one way of helping to protect the public's interest and safety. The Behavior Analyst Certification Board ([BACB], n.d.-a) has provided certification to behavior analysts worldwide for a couple of decades to improve public confidence and set professional standards for behavior analysis. As the world grows and changes, there is an increasing need to create nation-specific regulatory bodies to meet the unique demands of behavior analysts practicing in their countries. In Australia, the use of behavior analysis and the number of practicing behavior analysts has grown in the last decade. This article describes the efforts of behavior analysts in Australia to first create a national membership body and then establish a national regulatory framework for behavior analysis. The impact of critical factors to the development of an Australian behavior analytic regulation system such as the National Disability Insurance Scheme and the history of allied health regulation in Australia is discussed. Lastly, suggestions are offered for other countries to develop their own regulatory frameworks.

Keywords: Australia, Regulation, Professional self-regulation, Behavior analysts, Professional association

As a nation, Australia has made many gains in the last 20+ years in the education and disability sectors. One area that has seen growth has been the systematic use of behavior analysis in both these sectors. Behavior analysts have practiced in Australia for many decades, and the first Australian certified by the Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB) was in 2007. The growth of behavior analysts certified by the BACB was initially slow, with only 29 certificants by 2013 (BACB, n.d.-b). One barrier to the growth of BACB certificants in these early days was the lack of an Australian university program to train future behavior analysts. Interested students could only learn from costly online courses offered internationally. There was also significant difficulty finding supervisors, resulting in Australia relying heavily on imported behavior analysts. These were significant factors in the slow growth of Australian behavior analysts.

Slow growth was not necessarily a negative; the number of formally trained behavior analysts was small, providing a sense of community and the need for that community to come together. This small community of behavior analysts helped form the Association for Behaviour Analysis Australia (ABA Australia, n.d.) in 2012. Similar to the story of many significant associations, a small and dedicated group of people set off on a mission, not exactly sure how to do it but full of passion and desire to see the job done. After navigating the complexities of opening a national-level not-for-profit on a shoestring budget, ABA Australia opened its doors for membership in January 2014.

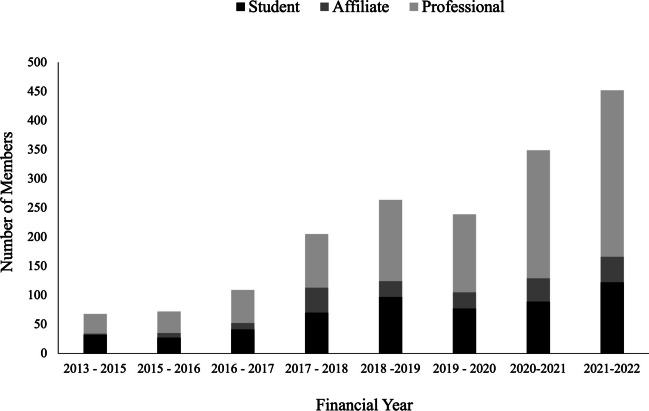

Over the last decade, ABA Australia achieved a number of accomplishments, such as submitting several papers on various inquiries by the Australian government, speaking at a senate hearing about the education system, holding annual conferences since 2016, and growing membership from 2014 to 2022 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

ABA Australia membership per financial year from 2013 to 2022. Note. The stacked bars represent the total number of members for the financial year

National Disability Insurance Scheme

As ABA Australia grew, the landscape that most behavior analysts practiced within changed significantly. This change came from a new funding system called the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS). The NDIS aims to give better “choice and control” over services so that people with disabilities can achieve their goals, increase independence, and participate in the community (NDIS, 2021a). The NDIS is implemented and overseen by the National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA), a Commonwealth government agency. This scheme was launched in 2013 and was formally adopted by all states and territories by 2020 (NDIS, 2021b). The NDIS is considered the most significant reform to disability services in decades (Warr et al., 2017). The rollout of NDIS meant greater access to many services, including applied behavior analysis (ABA), and behavior analysts had to practice within the rules and stipulations set out by government legislation.

Behavior analysts have long encountered the situation where the Australian government has failed to comprehend what ABA is, what a behavior analyst does, and who can call themselves a behavior analyst. The advocacy of using behavior analytic interventions that align with the evidence-based practices in the NDIS was challenging, in particular the need for intensive hours for young children or that adolescents and adults with disabilities would greatly benefit from such interventions. Another barrier was that the NDIA did not formally recognize certification by the BACB. Evidence of this was that behavior analysts were not listed as a service provider on any pricing arrangements from the NDIA. The pricing arrangement states the price per service and lists specific professionals to provide various services. The pricing arrangement became more refined each year, listing more professions individually (NDIA, 2022). For example, speech pathologists, occupational therapists, psychologists, and music therapists are all individually listed to provide services under the “therapeutic supports” category that many behavior analysts use for billing but must use a generic “other services” price item. It is interesting to note that pre-NDIS, there was one government funding option called Helping Children with Autism, which listed board certified behavior analysts (BCBA) as eligible providers (Department of Social Services, 2015). The Helping Children with Autism funding was discontinued with the advent of the NDIS. Despite the NDIA not listing individuals with BACB certificates on the pricing arrangement, "BCBA" appeared in other government documentation as a professional who is qualified to deliver behavior support or early intervention services (Dew et al., 2017; NDIA, 2020; Office of the Senior Practitioner, 2022), indicating that behavior analysts were making the science of behavior analysis and the need for certification known in Australia.

Types of Australian Allied Health Regulation

Developing a regulatory framework in behavior analysis depended on understanding the implementation of regulation in one of our primary areas of work, allied health. Allied health has no commonly accepted definition in Australia, but most definitions refer to professionals who assess and treat disorders using evidence-based practices (Allied Health Professions Australia AHPA, 2023; Department of Health & Aged Care, 2023). In Australia, there is further inclusion of having university qualifications, a national peak body to assess competency, a scope of practice, the autonomy of practice, and it is not medical, nursing, or dental professions (AHPA, 2023). This means that Australia considers many professions “allied health.” The allied health workforce is regulated under either the National Registration and Accreditation Scheme or professional self-regulation (Department of Health & Aged Care, 2022). Though each type of regulation is different, their history of development is closely related.

National Registration and Accreditation Scheme

In the early 2000s, the Australian government began considering the health workforce as a priority for the nation. A primary concern was the shortage of health professionals and the need to rely on overseas-trained professionals (Productivity Commission, 2005). This led to Australia's Health Workforce Productivity Commission Research in 2005. This report highlighted several issues affecting the health workforce, such as 90 different registration boards and 20 professional bodies accrediting health practitioners. The high number of registration and accreditation systems resulted in many variations in the accreditation process. It made mobility of the workforce across Australia difficult because every jurisdiction had different requirements. This report's primary suggestion was to create a national registration and accreditation system.

By 2010, the National Registration and Accreditation Scheme (NRAS) was launched (Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency [AHPRA], 2022) as the model for regulating health professionals across Australia. The NRAS was established to protect the public, provide workforce mobility for practitioners, provide training and professional development standards, promote access to health services, and provide a framework to assess overseas-trained health practitioners (Wardle et al., 2016). It is interesting that NRAS could not be implemented under common law (the national laws in Australia) for constitutional reasons, so each state and territory passed similar legislation to ensure that NRAS could be implemented.

AHPRA was formed to ensure NRAS was consistently implemented across all states and territories. In 2010, AHPRA provided oversight for 10 professions that met the requirement to be accepted into NRAS. By 2018 another five professions were accepted in NRAS (AHPRA, 2022). The professions included in NRAS were due to the perceived risk they could cause to the public (AHPA, 2012). This made sense, given many of the professions in NRAS are medically based; however, some are within the allied health field. As stated before, the allied health field is broad in Australia. However, well-established professions such as the Australian Association of Social Work ([AASW], 2023), established in 1946, and Speech Pathology Australia ([SPA], n.d.), established in 1949, were formally denied entrance into NRAS. An unforeseen effect of differentiating professions by potential risk is that it fragmented the allied health sector into professions in NRAS and everyone else. For those professions that were not included in NRAS, it is not to say that these professions were not concerned about public safety or did not want to be governed by the national law; they did not meet the “risk” requirement to be let into NRAS (Table 1).

Table 1.

Professions Included and Excluded in the National Regulation Accreditation Scheme

| Professions included in NRAS | Professions Excluded from NRAS |

|---|---|

| Psychologists | Social Workers |

| Occupational Therapists | Speech Pathologists |

| Physiotherapists | Dietitians |

| Chiropractors | Audiologists |

| Dental Practitioners | Sonographers |

| Medical Practitioners | Orthotic Prosthetists |

| Nurses and Midwives | Perfusionists |

| Optometrists | Exercise and Sports Scientists |

| Osteopaths | |

| Pharmacists | |

| Podiatrists | |

| Paramedics | |

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Practitioners | |

| Chinese Medicine Practitioners | |

| Medical Radiation Practitioners |

Professional Self-Regulation in Australia

Professional self-regulation can be defined as "a regulatory process whereby an industry-level organization (such as a trade association or a professional society), as opposed to a governmental–or firm—level organization sets and enforces rules and standards, relating to the conduct of firms in the industry" (Gupta & Lad, 1983, p. 417). Professional self-regulation tended to arise from an absence of government regulation or concern over excessive government regulation (Castro, 2011). For self-regulating professions, the professionals set standards and monitor and address any conflicts as they arise (Healy, 2016). It should be noted that professional self-regulation is a voluntary form of regulation and that the profession has no title protection.

The National Alliance of Self Regulating Health Professions (NASRHP) started as a committee of the Allied Health Professions Australia in 2008, with the purpose to support self-regulating health professions. In 2016, NASRHP became an independent organization (operating independently of the Australian government) with the nine allied health professions that were excluded from NRAS (NASRHP, 2017). Its purpose is to educate the public, increase public confidences, and oppose discriminatory practices about self-regulation. In addition, NASRHP created 11 standards for self-regulatory professions to guarantee quality and a unified framework for operation (Dietitians Association of Australia, 2016). These standards are similar to the requirements needed for inclusion into NRAS (Table 2).

Table 2.

NASRHP Membership Standards

|

Scope (Areas) of Practice Code of Ethics/Practice and/or Professional Conduct Complaints Procedure Competency Standards Course Accreditation Continuing Professional Development English Language Requirement Mandatory Declarations Professional Indemnity Insurance Practitioner Certification Requirements Recency and Resumption of Practice Requirements |

ABA Australia and Professional Self-Regulation

Over the last decade, it became apparent that an Australian-based regulatory system was needed for behavior analysts. NDIA regularly pointed out that the BACB certification was not Australian, indicating that an Australian behavior analytic regulation board must be established for behavior analysis to be considered equal with other allied health professions. In 2019, the ABA Australia board of directors voted to start researching regulatory frameworks. There was a committee formed to start that early research. Not long after this, the BACB announced that global certification would be limited (BACB, 2022). An establishing operation had been put into place for the ABA Australia board of directors to shift their effort from researching the idea of a regulatory system to creating a regulatory system for behavior analysts in Australia. The initial meetings discussed the possibility of creating a second organization to manage the regulation while ABA Australia remained the professional membership body. There were some concerns about the viability of a second company. ABA Australia was built on the blood, sweat, and tears of its amazing volunteers, it took years to become financially stable and known within the Australian community, and it would not be easy to find another group of volunteers to run a massive national regulation project promptly. Another reason ABA Australia chose to include regulation as part of its operations was that it is common practice among self-regulating professions in Australia to have the membership body (the one whose focus is dissemination and advocacy) also be the self-regulating organization. In keeping with Australian custom and from a business perspective, the board of directors chose to have only one organization to regulate behavior analysts and continue with efforts in dissemination.

In 2020, ABA Australia wrote a position paper outlining the regulation options and which one was chosen. Following this, a mammoth task analysis was created. Workgroups were established to tackle that giant task analysis. These groups were composed of many different volunteers who worked on document creation throughout 2021 and 2022. Documents were created by researching existing examples, creating a template for that document based on preferred elements of existing examples, writing a rough draft, multiple revisions, and finally, approval by the board of directors. This process created a Code of Ethical Practice, a list of professional competencies, a complaints process, and standards for professional development, supervision, and education. All these requirements and documents have been developed within Australia's cultural and social expectations. Education standards the Association for Behavior Analysis International (ABAI) set out have been adopted. Using the ABAI tiered system allowed current university programs in Australia to continue to operate without changing any course curriculum and provided public confidence that Australian behavior analysts were provided with the knowledge and skills to practice in Australia. Professional development requirements are on an annual basis in Australia. Our members can use four categories of professional development activities to acquire the required 20 hr. The supervision standards were simplified, because the number of behavior analysts holding a certification was low.

ABA Australia's certification levels have been organized into four career stages for behavior analysts. They are “certified behaviour analyst,” “certified behaviour analysts-undergraduate,” “professional,” and “affiliate.” The stages reflect the continuum of a behavior analyst developing professional expertise from entry level through expert. There are two additional levels outside the regulation model—student and supporter members. Most of the membership levels were modelled after certification levels from the BACB. The BACB certification provides a good basis for creating a quality behavior analyst, it is the world's most established behavior analytic certificate program, and has achieved massive growth in the past 20+ years. In addition, behavior analysts in Australia have been using this type of certification for decades and are very familiar with the standards. ABA Australia also relied on the support and collaboration from the BACB and the Association of Professional Behavior Analysts through the years of establishing a professional self-regulation system.

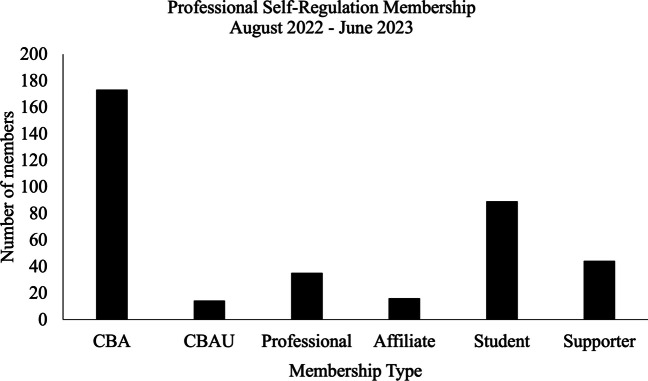

From the onset of creating a national professional self-regulation system, ABA Australia used the 11 standards to become a member of NASRHP as the foundation of their system (McLean, 2016). The 11 standards provided a clear framework and was flexible enough to incorporate aspects from the BACB certification program that Australians value as behavior analysts. It was through this process that ABA Australia developed a regulation structure that is centric to Australian behavior analysts to ensure ethical practice and public protection. Finally, on August 15, 2022, ABA Australia started taking memberships under the new model of professional self-regulation (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

ABA Australia Membership Numbers Based on Applications Approved since Starting Professional Self-Regulation on August 15, 2022

Looking Forward

There was no post-reinforcement pause for ABA Australia because processing new membership applications, continuing to improve regulation practices, and holding an annual conference are their top priorities. ABA Australia is currently working on refining their supervision standards, creating a certification exam, encouraging universities to offer behavior analytic course sequences, working toward fair representation in the NDIA and by other government agencies, and becoming full members of NASRHP.

ABA Australia has a few words of advice or encouragement for other nations who want to create their regulatory system for behavior analysts:

Understand how similar professions are regulated in your country. Make sure your model of regulation fits your country.

Regulation is a business, and you must run it like a business; if you do not, it will fail.

You do not have to have a perfect regulation system immediately (we definitely did not). It will take time to develop all the bells and whistles that you want. Do not feel pressured to have a perfect system at the beginning. What is important is that you have a solid foundation to shape into what you want.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the project conception and design. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Alayna Haberlin and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

This article was presented at the annual meetings of the Association for Behaviour Analysis Australia in Sydney, Australia in 2022.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Nonfinancial Interests

Michelle Furminger and Alexandra Brown are on the board of directors of the Association for Behaviour Analysis Australia and receive no compensation as members of the board of directors.

Financial Interests

Alayna Haberlin and Claire Connolly receive a part-time salary from the Association for Behaviour Analysis Australia.

Footnotes

The Association for Behaviour Analysis Australia acknowledges the Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of our nation. We acknowledge the traditional custodians of the lands on which our company is located and where we conduct our business. We pay our respects to ancestors and Elders, past and present. The Association for Behaviour Analysis Australia is committed to honoring Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ unique cultural and spiritual relationships to the land, waters and seas and their rich contribution to society.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Allied Health Professionals Australia. (2012). Harnessing self-regulation to support safety and quality in healthcare delivery. A comprehensive model for regulating all health practitioners. Retrieved July 10, 2022, from https://www.aopa.org.au/publications/external-resources

- Allied Health Professionals Australia. (2022). About the national scheme. Retrieved July 10, 2022, from https://www.ahpra.gov.au/About-Ahpra/What-We-Do/FAQ.aspx

- Allied Health Professionals Australia. (2023). What is allied health. Retrieved January 14, 2023, from https://ahpa.com.au/what-is-allied-health/

- Association for Behaviour Analyst Australia. (n.d.). Who we are. Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://auaba.com.au/Who-We-Are.

- Australian Association of Social Workers. (2023). A brief history of AASW. Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://www.aasw.asn.au/about-aasw/a-brief-history

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (n.d.-a). About the BACB. Retrieved July 17, 2022, from https://www.bacb.com/about/

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (n.d.-b). BACB certificant data. Retrieved January 17, 2023, from https://www.bacb.com/BACB-certificant-data.

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2022). Recent changes to the BACB’s international focus. Retrieved July 10, 2022, from https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Recent-Changes-to-International-Focus_220711.pdf

- Castro, D. (2011). Benefits and limitations of industry self-regulation for online behavioral advertising. Information Technology & Innovation Foundation. Retrieved July 10, 2022, from https://itif.org/publications/2011/12/13/benefits-and-limitations-industry-self-regulation-online-behavioral/

- Department of Health & Aged Care. (2023). About allied health care. Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved January 14, 2023, from https://www.health.gov.au/health-topics/allied-health/about

- Department of Health & Aged Care. (2022). Who can provide allied health. Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved January 14, 2023, from https://www.health.gov.au/topics/allied-health-care/who-can-provide

- Department of Social Services. (2015). Early intervention service provider panel operational guidelines. Australian Government. Retrieved July 17, 2022, from https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/05_2015/early_intervention_service_provider_panel_operational_guidelines_-_february_2015_4.pdf

- Dew, A., Jones, A., Cumming, T., Horvat, K., Dillon Savage, I., & Dowse, L. (2017). Understanding behaviour support practice: Children and young people (9–18 years) with developmental delay and disability. UNSW Sydney. Retrieved July 17, 2022, from https://www.arts.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/documents/UNSW_Understanding_Behaviour_Support_Practice_Guide_Children9to18_colour_0.pdf

- Dietitians Association of Australia. (2016). Annual Report 2016. Retrieved January 14, 2023, from https://dietitiansaustralia.org.au/sites/default/files/2021-12/Annual%20Report-2016.pdf

- Gupta, A. K., & Lad, L. J. (1983). Industry self-regulation: An economic, organizational, and political analysis. Academy of Management Review, 8, 416–425. 10.5465/amr.1983.4284383 [Google Scholar]

- Healy, K. (2016). 2015 Norma Parker address: Being a self-regulating profession in the 21st century: Problems and prospects. Australian Social Work, 69(1), 1–10. 10.1080/0312407X.2016.1103391 [Google Scholar]

- McLean, E. (2016). Self-regulating health profession peak bodies membership standards. National Alliance of Self Regulating Health Professions. Retrieved February 08, 2020, from http://nasrhp.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/SR_Standards_Full_Dec_2.pdf

- National Alliance of Self Regulating Health Professionals. (2017). About. Retrieved July 10, 2022, from https://nasrhp.org.au/about-us/

- National Disability Insurance Agency. (2020). Behavioural intervention. Retrieved July 17, 2022, from https://www.ndis.gov.au/about-us/research-and-evaluation/early-interventions-and-high-volume-cohorts/evidence-review-early-interventions-children-autism/behavioural-interventions

- National Disability Insurance Agency. (2021a). History of NDIS. Retrieved January 20, 2023, from https://www.ndis.gov.au/about-us/history-ndis.

- National Disability Insurance Agency.. (2021b). What is the NDIS. Retrieved January 14, 2023, from https://www.ndis.gov.au/understanding/what-ndis

- National Disability Insurance Agency.. (2022). Pricing arrangements and price limits 2022–23. Retrieved January 20, 2023, from https://www.ndis.gov.au/providers/pricing-arrangements

- Office of the Senior Practitioner. (2022). Implementation guideline for disability support providers. Australian Capital Territory. Retrieved July 17, 2022, from https://www.communityservices.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/1954495/Implementation -Guideline-for-Disability-Support-Providers.pdf

- Productivity Commission. (2005). Australia’s health workforce, research report. Canberra. Retrieved July 17, 2022, from https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/health-workforce/report

- Speech Pathology Australia. (n.d.). About speech pathology Australia. Retrieved January 28, 2023, from https://www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au/SPAweb/About_us/About_SPA/SPAweb/About_Us/About/About.aspx?hkey=b95cb0c9-632a-4022-85c5-79b97a250954

- Wardle, J. L., Sibbritt, D., Broom, A., Steel, A., & Adams. J (2016). Is Health practitioner regulation keeping pace with the changing practitioner and health-care landscape? An Australian Perspective. Frontiers in Public Health, 4. 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Warr, D., Dickinson, H., Olney, S., Hargrave, J., Karanikolas, A., Kasidis, V., Katsikis, G., Ozge, J., Peters, D., Wheeler, J., & Wilcox, M. (2017). Choice, control and the NDIS. University of Melbourne. Retrieved January 20, 2023, from https://socialequity.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/2598497/Choice-Control-and-the-NDIS.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.