Highlights

-

•

138 reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction confirmed Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) cases were investigated between October and December 2024.

-

•

Persistent symptoms in >81% of the 58 followed-up patients.

-

•

Average loss of 10.5 workdays (range: 3-60 days) due to CHIKV infection.

-

•

Sequence data analysis of 12 samples confirmed the circulation of the East-Central-South-African (ECSA) genotype, with all samples containing the E1-K211E substitution.

-

•

Reappearance of CHIKV in Bangladesh after a 7-year hiatus since 2017, which could potentially trigger a larger outbreak in the near future.

Keywords: Chikungunya, Bangladesh, ECSA genotype, 2024, E1 gene, E1-K211E

Abstract

Objectives

We investigated a new outbreak of Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) in Dhaka and nearby areas of Bangladesh in 2024, examining its epidemiology, clinical features, and genomic characteristics.

Methods

The Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research enrolled suspected Chikungunya cases from October 19 to December 31, 2024. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction was performed, and positive cases were followed up via telephone between days 21 and 28. The E1 gene of 12 samples was sequenced.

Results

Of 394 enrolled patients, 138 (35%) were CHIKV-positive, mostly male (64.5%) and over 30 years old (83.3%), with 98.6% residing in Dhaka. Common symptoms included fever (100%), arthralgia (97.8%), myalgia (83.2%), and headache (65.0%). While no fatalities were recorded, 14.5% required hospitalization with an average stay of 5.9 days, and patients lost an average of 10.5 workdays. At 28 days, 81% of 58 follow-up patients had persistent symptoms. Both hospitalization and persistent symptoms were associated with having >4 symptoms initially (incidence risk ratio: 1.14; 95% confidence interval: 1.02-1.27 and 1.19; 95% confidence interval: 1.01-1.39, respectively). Sequence analysis identified an E1-K211E substitution, with phylogenetics revealing a distinct East-Central-South-African (ECSA) sub-lineage compared to 2017 strains.

Conclusions

CHIKV is likely to re-emerge in Bangladesh amid the ongoing dengue outbreak, posing a risk of a major outbreak soon. Strengthening efforts to control Aedes mosquitoes is essential.

Introduction

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is a member of the genus Alphavirus of the family Togaviridae, transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes, primarily Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus [1]. CHIKV was first identified in Tanzania in 1950s [2] and initially caused sporadic outbreaks in Africa and Asia until 2004 [3], when a significant outbreak in Kenya in 2004 marked the beginning of a resurgence of CHIKV, resulting in extensive spread to the Indian Ocean islands, including the Comoros, Seychelles, Mauritius, and the French territories of Mayotte and La Réunion [3]. The epidemiology and transmission patterns of CHIKV shifted notably during the 2005-2006 outbreaks in La Réunion, where A. albopictus mosquitoes were identified as the primary vector [3,4]. The global spread of CHIKV has been partially attributed to its adaptation to this mosquito species, facilitated by a mutation in the envelope protein 1 (E1) gene resulting in the substitution of E1-A226V [3]. This mutation enhanced the ability of A. albopictus mosquitoes to transmit the virus to humans [3]. After this adaptation, CHIKV has been transmitted to more than 100 countries worldwide between 2014 and 2019 [1]. The CHIKV infects approximately 3 million people annually, with an estimated 1.3 to 2.7 billion people currently residing in areas at risk of CHIKV transmission [5].

CHIKV was first reported in Bangladesh in December 2008 in two adjacent north-western districts, Rajshahi and Chapai Nawabganj. Subsequently, outbreaks were reported in 2009, 2011, and 2012 [6,7]. In 2017, Bangladesh experienced the largest CHIKV outbreak with 13,176 clinically confirmed cases in 17 out of 64 districts of the country [8]. A modeling study predicted a peak prevalence of 47 cases per 1,000 people in Dhaka city during the 2017 outbreak [9]. These estimates are significantly higher than the official report of 13,176 cases [9]. The study also estimated a very high basic reproduction number (R0) of CHIKV (4.2) during the 2017 outbreak [9]. Nationwide surveillance conducted between 2015 and 2016 reported a seroprevalence of 2.4% and predicted 4.99 million people to be infected with CHIKV before the 2017 major outbreak in Bangladesh [10]. However, after 2017, CHIKV had almost disappeared from Bangladesh, with a few sporadic cases detected in the country. This study reports an outbreak of CHIKV in Dhaka and its surrounding areas in late 2024, detailing the clinical & epidemiological features of the outbreak as well as genomic characteristics of the virus.

Methods

Epidemiological data collection

During the third week of October 2024, a Chikungunya outbreak in Dhaka city was detected by the Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research (IEDCR) through the event-based surveillance system. In response to the outbreak, being the mandated institute for outbreak investigation, control, and response in Bangladesh, IEDCR established a sample collection booth to facilitate testing for suspected Chikungunya cases referred by the physicians from different corners of the city. A suspected Chikungunya case was defined as any individual presenting with fever and arthralgia/arthritis not attributable to other medical conditions. Data were collected using a pre-designed questionnaire, and informed consent was obtained from all participants during sample collection to include them in the study. A total of 394 suspected cases were enrolled during the period from 19 October to 31 December 2024.

Sample collection

Following aseptic procedures, 3-4 ml of blood was collected from each participant into tubes containing a blood clot activator. The serum was then separated and stored at a 4°C refrigerator at IEDCR until further testing could be performed. Positive serum samples were stored at −80°C for further analysis.

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing

Viral RNA was extracted from 140 µl of serum using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini-Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions. The RNA was purified and eluted in a final volume of 30 µl.

Real-time RT-PCR was performed using the Genesig Dengue, Zika, Chikungunya multiplex RT-PCR Kit (Primer Design, UK) on an ABI QuantStudio 5 thermal cycler. The thermal cycling protocol included the following steps: Reverse Transcription at 55°C for 10 minutes, enzyme activation at 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by 50 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10 seconds and annealing & extension at 60°C for 1 minute. Fluorescence data were collected during the extension phase through the VIC (DENV), FAM (ZIKV), Cy5 (CHIKV), and ROX (internal control) channels. Post-PCR analysis involved evaluating amplification curves on a linear scale. Baseline thresholds were manually set for each run. Amplification curves with a cycle threshold (CT) value of <50 were considered positive. Amplification of the internal control confirmed the absence of PCR reaction inhibition.

E1 gene sequencing

A total of 12 samples with CT values of <27 were selected for sequencing of the E1 gene using the Oxford Nanopore Sequencing technology. Viral RNA was extracted from 140 µl of serum using QIAamp Viral RNA Mini-Kit (QIAGEN, Germany), converted into first-strand cDNA using LunaScript RT SuperMix (New England Biolabs, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNA was amplified with Q5 Hot start High fidelity 2X Master mix (New England Biolabs, USA) using the three sets of primers described previously [11]. The thermal cycling protocol included the following: Initial denaturation at 98°C for 30 seconds followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 98°C for 10 seconds, annealing at 70°C/70°C/68°C (for primer 19, 20 & 21) for 30 seconds, extension at 72°C for 30 seconds and a final extension step at 72°C for 2 minutes. The primers produced a set of three overlapping amplicons of 756, 1014, and 839 bp size. The amplicons were normalized and pooled per sample in equimolar amounts and cleaned with AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, USA). The samples were end-repaired with NEBNext Ultra II end repair/dA-tailing module (New England Biolabs, USA), followed by barcoding with EXP-NBD104 (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, UK). The barcoded amplicons were normalized, pooled, and cleaned with AMPure XP beads, followed by final library preparation with Ligation Sequencing Kit SQK-LSK109 (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, UK). A total of 20 fmol of the library was loaded and sequenced in a standard flow cell FLO-MIN106 (version 9.4.1) for 6 hours. MinKNOW v22.12.5 was used for base calling (high accuracy mode) and demultiplexing of raw reads. Minimum read quality was set to nine for read filtering.

The read quality of fastq files was assessed with NanoPlot v1.42 [12]. Read Mapping and alignment were done with minimap2 [13] using the NC_004162 as reference. BAM files were sorted and indexed with samtools v1.19.2 [14]. The consensus sequence was generated with medaka v1.11.3 [15]. The sequences were submitted to the NCBI GenBank with accession no. PQ963011 to PQ963022 and in the EpiArboTM database of GISAID [16] with accession no. EPI_ISL_19683650 to EPI_ISL_19683661. Genotype was assigned using the Chikungunya typing tool hosted at the Genome Detective website [17].

Phylogenetic analysis

E1 gene sequences of human CHIKVs circulating in Asia were retrieved from the GISAID database. Sequences with long stretches of ‘N’ and without a complete collection date were excluded. A time-resolved maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed, refined, and annotated using the Nextstrain tool Augur [[18], [19], [20], [21]]. The tree was exported and visualized using Auspice [18]. The final dataset included 286 E1 genes of human CHIKV from 13 Asian countries.

Statistical analysis

All comorbidities were categorized into three major morbidity groups for inclusion in the model: Respiratory diseases (including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, and interstitial lung disease); Cardiometabolic diseases (comprising diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease, and hypertension); and Other chronic conditions (consisting of chronic liver disease, chronic kidney disease, and cancer). Participants were assigned to a morbidity group if they presented with at least one condition within the respective category. We examined the associations of outcome variables, disease severity, and different independent variables using a modified Poisson regression model. A generalized estimating equation-modified Poisson regression approach with a robust error variance option was employed to directly assess risk ratios (RRs) accompanied by 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for significance testing. Data analysis was performed using the latest version of R software [22].

Results

We tested a total of 394 suspected Chikungunya patients, of which 138 (35%) were confirmed positive for CHIKV. Additionally, 11 samples (2.8%) tested positive for Dengue virus (DENV). No co-infection with both CHIKV and DENV was detected in any of the positive cases. Among the 138 positive cases, two patients had a history of international travel (China and Hong Kong, respectively), most were male (n = 89, 64.5%) and aged ≥30 years (n = 115, 83.3%). The most common clinical symptoms included fever (100%), arthralgia (97.8%), myalgia (83.2%), and headache (64.9%). Over 47% of patients (n = 65) had at least one comorbidity, with hypertension (26.1%, n = 36) and diabetes mellitus (26.1%, n = 36) being the most prevalent. Most patients were recruited during December (n = 75), while the rest were in November (n = 58) and October (n = 5) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The daily recruited confirmed Chikungunya cases at the Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research (IEDCR), Bangladesh, between 16 October and 31 December 2024.

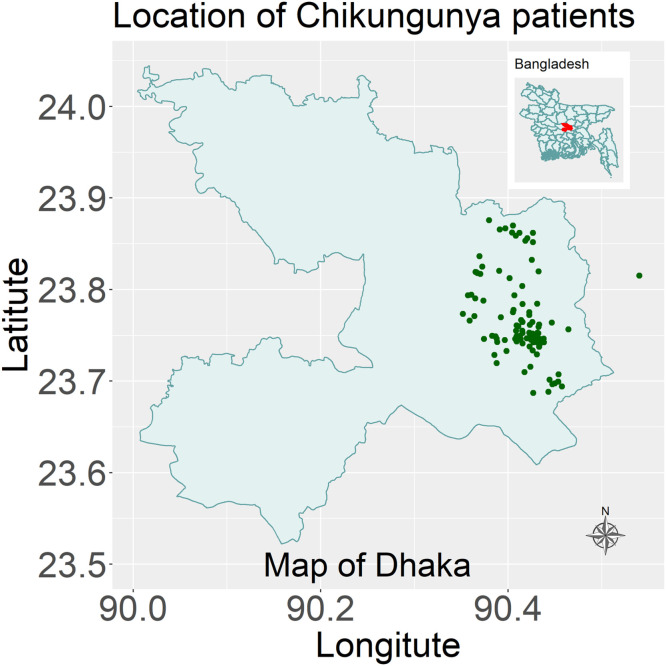

Most of the patients were recruited from Dhaka city (72 from Dhaka South City Corporation and 64 from Dhaka North City Corporation) while only two were from outside Dhaka city, one being in Narayanganj district and another one in Keraniganj, a subdistrict of Dhaka (Figure 2). The maximum distance between the two geographically separated cases was 12.21 km.

Figure 2.

The geographical location of Chikungunya cases in Bangladesh between 16 October 2024 and 31 December 2024.

We followed up with 58 patients (42.0%) to assess their health outcomes between 21 and 28 days after the initial illness. No patient died, however, 47 out of 58 patients (81.0%) reported persistent symptoms during the follow-up period, while only seven patients (12.1%) had fully recovered. The most common persistent symptoms were joint pain (96.0%), fatigue (29.4%), and joint swelling (19.6%). On average, patients lost 10.5 working days (range: 3-60 days) due to CHIKV infection. Considering the daily per capita income of US$ 6.98 in Bangladesh [23], the disease caused an average household income loss of US$ 73.3 per patient.

Among the 138 CHIKV-positive cases, 20 (14.5%) patients required hospitalization, with a mean duration of 5.9 days of hospital stay. The mean (range) age of the hospitalized patients was 52 (15-78) years, while the remaining patients had a mean age of 42.1 (12-81) years. The most common comorbidity of the patients who required hospitalization was diabetes mellitus (45%), hypertension (45%), followed by ischemic heart disease (25%). Hospitalization of patients was associated with the presence of chronic diseases (incidence RR [IRR]: 1.44, 95% CI: 1.04-1.90), cardiometabolic diseases (IRR: 1.28, 95% CI: 1.11-1.47) and having more than four clinical symptoms at initial presentation (IRR: 1.14, 95% CI: 1.02-1.27) while persistence of clinical symptoms at 28 days followed-up was associated with having >4 clinical symptoms initially (IRR: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.01-1.39) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Factors associated with hospitalization and persistent symptoms at 28-day follow-up of Chikungunya virus-positive patients in Bangladesh between 16 October and 31 December 2024, using a modified Poisson regression model.

| Variables | Hospitalization | Persistent symptoms at 28-day follow-up | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IRR (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | ||

| Age group | <30 years | Reference | Reference |

| ≥30 | 1.02 (0.92-1.12) | 1.18 (0.97 – 1.43) | |

| Gender | Female | Reference | Reference |

| Male | 1.06 (0.94- 1.19) | 0.92 (0.78-1.10) | |

| Respiratory diseases | No | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 1.10 (0.91-1.34) | 1.08 (0.87-1.34) | |

| Cardiometabolic diseases | No | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 1.28 (1.11-1.47) | 1.05 (0.88-1.24) | |

| Chronic disease | No | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 1.44 (1.04-1.99) | 1.30 (0.91-1.86) | |

| Clinical symptoms | ≤4 | Reference | Reference |

| >4 | 1.14 (1.02-1.27) | 1.19 (1.01-1.39) | |

CI, confidence interval; IRR, incidence risk ratio.

The sequencing library generated 27,195 reads that passed the quality filter. The mean read length was 853, and the mean read quality was 11.2. The read length N50 was 860. The average depth of coverage ranges from 413x – 1250x. The 12 E1 gene sequences in this study have a length of 1510 bp. They exhibit >99% nucleotide similarity among themselves. Compared to the reference sequence NC_004162, the sequences shared 97%-97.2% identity at the nucleotide level and 98.2%-98.6% identity at the amino acid level. All samples were assigned to the East-Central-South-African (ECSA) genotype. Important amino acid mutations were found in the sequences D284E, I55V, K211E, M269V, V322A & V367A. Sequencing findings and related metadata are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sequencing findings and related metadata of 12 Chikungunya viruses from and 2024 Outbreak.

| Serial | Sequence ID | Collection date (YYYY-MM-DD) | Geographical location | Sex | Age (years) | Patient status during sample collection | Accession (GISAID/ GenBank) |

Sequence length | Sequencing depth (×) | Genotype | Mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | OIS23-288 | 2024-11-07 | Dhaka | F | 49 | Live | EPI_ISL_19683650/ PQ963011 | 1510 | 987 | ECSA | D284E, I55V, K211E, M269V, V322A |

| 2 | OIS23-299 | 2024-11-10 | Dhaka | M | 48 | Live | EPI_ISL_19683651/ PQ963012 | 1510 | 1147 | ECSA | D284E, I55V, K211E, M269V |

| 3 | OIS23-306 | 2024-11-12 | Dhaka | F | 32 | Live | EPI_ISL_19683652/ PQ963013 | 1510 | 771 | ECSA | D284E, I55V, K211E, M269V |

| 4 | OIS23-309 | 2024-11-12 | Dhaka | M | 32 | Live | EPI_ISL_19683653/ PQ963014 | 1510 | 413 | ECSA | D284E, I55V, K211E, M269V, V322A |

| 5 | OIS23-313 | 2024-11-13 | Dhaka | M | 60 | Live | EPI_ISL_19683654/ PQ963015 | 1510 | 853 | ECSA | D284E, I55V, K211E, M269V, V322A |

| 6 | OIS23-347 | 2024-11-17 | Dhaka | F | 35 | Hospitalized | EPI_ISL_19683655/ PQ963016 | 1510 | 1250 | ECSA | D284E, I55V, K211E, M269V, V322A |

| 7 | OIS23-351 | 2024-11-18 | Dhaka | F | 37 | Live | EPI_ISL_19683656/ PQ963017 | 1510 | 975 | ECSA | D284E, I55V, K211E, M269V, V322A |

| 8 | OIS23-352 | 2024-11-18 | Dhaka | M | 30 | Live | EPI_ISL_19683657/ PQ963018 | 1510 | 1021 | ECSA | D284E, I55V, K211E, M269V |

| 9 | OIS23-365 | 2024-11-19 | Dhaka | F | 31 | Live | EPI_ISL_19683658/ PQ963019 | 1510 | 490 | ECSA | D284E, I55V, K211E, M269V, V322A |

| 10 | OIS23-373 | 2024-11-20 | Dhaka | M | 56 | Live | EPI_ISL_19683659/ PQ963020 | 1510 | 499 | ECSA | D284E, I55V, K211E, M269V |

| 11 | OIS23-384 | 2024-11-21 | Dhaka | F | 48 | Live | EPI_ISL_19683660/ PQ963021 | 1510 | 857 | ECSA | D284E, I55V, K211E, M269V, V367A |

| 12 | OIS23-403 | 2024-11-25 | Dhaka | M | 35 | Hospitalized | EPI_ISL_19683661/ PQ963022 | 1510 | 709 | ECSA | D284E, I55V, K211E, M269V, V322A |

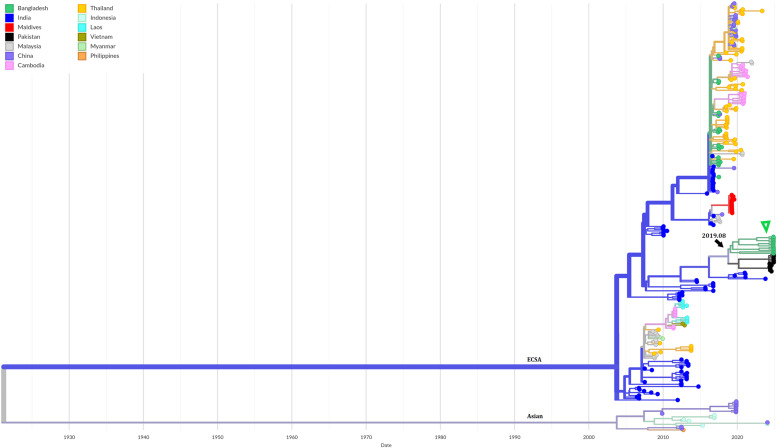

Phylogenetic analysis showed, all the sequenced cases were closely related and formed a cluster within the previously circulating Indian Ocean Lineage of the ECSA genotype (Figure 3). This cluster is related more distantly to the previously circulating Bangladeshi strains. The analyses indicate that their most recent common ancestor evolved from the previously circulating strains in the country during the early part of 2019 (CI: 2018-03-04, 2020-11-04). The phylogeography map indicates a few events of viral exchange with the neighboring countries, India, Thailand, and China (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Time-scaled phylogeny of Chikungunya viruses circulating in Asia showing 286 genomes sampled between June 2006 and November 2024. The color of the tips indicated the host country of the taxa. Branch color indicated the inferred ancestral geographic location of the descendants. Genotype was indicated adjacent to the key branches. The number above the black arrow denotes the inferred year of introduction of the currently circulating lineage in Bangladesh. The green triangle indicates the sequenced samples in this study. Numbers in the X axis represent the time in the unit of years.

Figure 4.

Geographical transmission map of Chikungunya viruses in Asia showing the regional movement of viruses. The placement of the circles (demes) in the map is according to the sampling location. The size of the demes indicates the number of sequences sampled from a specific country. Colors of the demes are according to the Countries indicated in the legend. The shape & color of the transmission lines denote the direction of the virus movement.

Discussion

The re-emergence of the CHIKV in Dhaka, Bangladesh, came after a near disappearance of the virus following the 2017 outbreak, highlighting a serious concern, especially in the context of the ongoing and large-scale dengue epidemic in Bangladesh, which continues to place significant strain on public health systems [24,25]. Although this study was limited to patients presented to a single referral center, and the findings may not be generalized, the clinical characteristics observed were consistent with previous reports of CHIKV infections, with fever, arthralgia, myalgia, and headache being the predominant symptoms [1]. Importantly, most patients (81%) who were followed up reported persistent symptoms at 28-day follow-up, underscoring the potential long-term health impact of CHIKV infections, even in the absence of fatalities.

No co-infection with CHIKV and DENV was detected in our study, although such co-infections are not uncommon, as reported in several studies [26]. The clinical impact of CHIKV and DENV co-infection remains controversial; while some studies have reported more severe clinical manifestations and longer hospital stays in co-infected patients, others have found no significant difference [26]. Given the overlapping symptoms of both diseases, misdiagnosis is likely if diagnostic testing targets only one virus, particularly in regions where both CHIKV and DENV are endemic.

The study also offers valuable insights into disease severity, revealing that it is higher in individuals with chronic diseases, cardiometabolic diseases, and the presence of more than four clinical symptoms initially. The hospitalization of 14.5% of patients and the resulting loss of workdays further highlight the significant social and economic burden of the outbreak. This is especially concerning given the fact that the healthcare systems are already strained by the ongoing dengue crisis [24].

The phylogenetic analysis revealed the evolution and emergence of a new sub-lineage within the previously circulating ECSA genotype of the virus in Bangladesh. These outbreak strains are closely related and their most recent common ancestor likely evolved during early 2019, from the previously circulating local strains rather than being introduced from external sources. Notably, the sequences in this study lack the E1-A226V substitution but carry the E1-K211E. CHIKVs sequenced during the 2017 outbreak in Bangladesh were also found to harbor this substitution [27]. This mutation was first detected in CHIKVs causing an outbreak in India during 2016 and spread extensively onwards to the countries in the region, including Bangladesh, Pakistan, Maldives, Myanmar, and Thailand, and also to African countries like Kenya [28]. Previous studies have shown that the E1-K211E substitution enhances the virus's fitness in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, resulting in increased replication and transmission of the virus in mosquitoes, contributing to the major outbreaks [29]. Given the abundance of this mosquito species in urban areas of Bangladesh [30], this finding raises serious concerns about the potential for large-scale outbreaks in major cities across the country.

Bangladesh provides a highly conducive environment for Aedes mosquito breeding, driven by factors such as rapid urbanization, extended rainfall, and widespread presence of mosquito breeding sites [31]. Additionally, the country’s temperature remains highly favorable for Aedes mosquitoes for approximately nine out of the 12 months each year [31]. CHIKV can spread rapidly, with a global basic R₀ estimated at 3.4 [32], and reaching as high as 4.2 during the 2017 outbreak in Bangladesh [9], suggesting the potential for a large-scale Chikungunya outbreak in the near future, possibly in 2025 or 2026. In 2023, Bangladesh experienced the largest dengue outbreak in its history, leading to a national crisis involving shortages of intravenous saline solutions and hospital beds [24]. In this context, the present study underscores the need for a comprehensive arboviral surveillance in the country. The study also serves as a crucial alert to prepare for a potential large-scale outbreak of Chikungunya in the near future.

Declarations of competing interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to the World Health Organization Bangladesh country office for providing Real-time polymerase chain reaction reagents for the detection of Chikungunya virus. We acknowledge the patients for providing the samples and data for this study. We also gratefully acknowledge all data contributors, i.e., the authors and their originating laboratories responsible for obtaining the specimens, and their submitting laboratories for generating the genetic sequence and metadata and sharing via the GISAID Initiative, on which the phylogenetic analysis is based. We also gratefully acknowledge the role of Md. Noman Rahman, Awlad Hossain, and Laxman Karmakar during the wet lab procedures of reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and sequencing.

Ethics statement

This study is a part of the response to Chikungunya outbreaks in Bangladesh, 2024 and thus is exempt from the formal ethical application. There are no identifiable individual-level data, and ethical approval is not required.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: AON and NH. Data curation: AON and MNH. Formal Analysis: AON, MNH, and NH. Writing original draft: NH and AON. Supervision: TS and ANA. Writing, review, and editing: IM, OQ, MRH, MHK, SS, JF, KTPP, MR, MR, ANA, and TS.

References

- 1.Vairo F., Haider N., Kock R., Ntoumi F., Ippolito G., Zumla A. Chikungunya: epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical features, management, and prevention. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33:1003–1025. doi: 10.1016/J.IDC.2019.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson MC. An epidemic of virus disease in Southern Province, Tanganyika territory, in 1952-1953. I. Clinical features. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1955;49:28–32. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(55)90080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson M., Conan A., Duong V., Ly S., Ngan C., Buchy P., et al. A model for a chikungunya outbreak in a rural Cambodian setting: implications for disease control in uninfected areas. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3120. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PNTD.0003120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yakob L., Clements ACA. A mathematical model of chikungunya dynamics and control: the major epidemic on Réunion island. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0057448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nsoesie E.O., Kraemer M.U.G., Golding N., Pigott D.M., Brady O.J., Moyes C.L., et al. Global distribution and environmental suitability for Chikungunya virus, 1952 to 2015. Euro Surveill. 2016;21 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.20.30234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khatun S., Chakraborty A., Rahman M., Nasreen Banu N., Rahman M.M., Hasan S.M.M., et al. An outbreak of chikungunya in rural Bangladesh, 2011. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9 doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PNTD.0003907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haque F., Rahman M., Banu N.N., Sharif A.R., Jubayer S., Shamsuzzaman A., et al. An epidemic of chikungunya in northwestern Bangladesh in 2011. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0212218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kabir I., Dhimal M., Müller R., Banik S., Haque U. The 2017 Dhaka chikungunya outbreak. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:1118. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30564-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahmud A.S., Kabir M.I., Engø-Monsen K., Tahmina S., Riaz B.K., Hossain M.A., et al. Megacities as drivers of national outbreaks: the 2017 chikungunya outbreak in Dhaka, Bangladesh. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15 doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PNTD.0009106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen S.W., Ribeiro Dos Santos G., Paul K.K., Paul R., Rahman M.Z., Alam M.S., et al. Results of a nationally representative seroprevalence survey of Chikungunya virus in Bangladesh. J Infect Dis. 2024;230:e1031–e1038. doi: 10.1093/INFDIS/JIAE335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sam I.C., Loong S.K., Michael J.C., Chua C.L., Wan Sulaiman W.Y., Vythilingam I., et al. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of Chikungunya virus of different genotypes from Malaysia. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0050476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Coster W., Rademakers R. NanoPack2: population-scale evaluation of long-read sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2023;39:btad311. doi: 10.1093/BIOINFORMATICS/BTAD311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:3094–3100. doi: 10.1093/BIOINFORMATICS/BTY191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Danecek P., Bonfield J.K., Liddle J., Marshall J., Ohan V., Pollard M.O., et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience. 2021;10:giab008. doi: 10.1093/GIGASCIENCE/GIAB008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.GitHub . 2024. nanoporetech/medaka: sequence correction provided by ONT Research. [Google Scholar]; https://github.com/nanoporetech/medaka, [accessed 19 February 2024]

- 16.Wallau G.L., Abanda N.N., Abbud A., Abdella S., Abera A., Ahuka-Mundeke S., et al. Arbovirus researchers unite: expanding genomic surveillance for an urgent global need. Lancet Glob Health. 2023;11:e1501–e1502. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00325-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vilsker M., Moosa Y., Nooij S., Fonseca V., Ghysens Y., Dumon K., et al. Genome Detective: an automated system for virus identification from high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:871–873. doi: 10.1093/BIOINFORMATICS/BTY695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hadfield J., Megill C., Bell S.M., Huddleston J., Potter B., Callender C., et al. Nextstrain: real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:4121–4123. doi: 10.1093/BIOINFORMATICS/BTY407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen L.T., Schmidt H.A., Von Haeseler A., Minh B.Q. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32:268–274. doi: 10.1093/MOLBEV/MSU300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katoh K., Misawa K., Kuma K.I., Miyata T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3059–3066. doi: 10.1093/NAR/GKF436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sagulenko P., Puller V., Neher RA. TreeTime: maximum-likelihood phylodynamic analysis. Virus Evol. 2018;4 doi: 10.1093/VE/VEX042. vex042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.R Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2021. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed 15 April 2025) [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Bank GDP per capita (current US$) 2023. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD [accessed 15 April 2025]

- 24.Haider N., Asaduzzaman M., Hasan M.N., Rahman M., Sharif A.R., Ashrafi S.A.A., et al. Bangladesh’s 2023 Dengue outbreak – age/gender-related disparity in morbidity and mortality and geographic variability of epidemic burdens. Int J Infect Dis. 2023;136:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2023.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hasan M.N., Rahman M., Uddin M., Ashrafi S.A.A., Rahman K.M., Paul K.K., et al. The 2023 fatal dengue outbreak in Bangladesh highlights a paradigm shift of geographical distribution of cases. Epidemiol Infect. 2025;153:e3. doi: 10.1017/S0950268824001791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dinkar A., Singh J., Prakash P., Das A., Nath G. Hidden burden of chikungunya in North India; a prospective study in a tertiary care centre. J Infect Public Health. 2018;11:586–591. doi: 10.1016/J.JIPH.2017.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melan A., Aung M.S., Khanam F., Paul S.K., Riaz B.K., Tahmina S., et al. Molecular characterization of Chikungunya virus causing the 2017 outbreak in Dhaka, Bangladesh. New Microbes New Infect. 2018;24:14–16. doi: 10.1016/J.NMNI.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phadungsombat J., Imad H.A., Nakayama E.E., Leaungwutiwong P., Ramasoota P., Nguitragool W., et al. Spread of a novel Indian Ocean lineage carrying E1-K211E/E2-V264A of Chikungunya virus east/central/South African genotype across the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and eastern Africa. Microorganisms. 2022;10:354. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10020354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agarwal A., Sharma A.K., Sukumaran D., Parida M., Dash PK. Two novel epistatic mutations (E1:K211E and E2:V264A) in structural proteins of Chikungunya virus enhance fitness in Aedes aegypti. Virology. 2016;497:59–68. doi: 10.1016/J.VIROL.2016.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rahman M.S., Faruk M.O., Tanjila S., Sabbir N.M., Haider N., Chowdhury S. Entomological survey for identification of Aedes larval breeding sites and their distribution in Chattogram. Bangladesh. Beni Suef Univ J Basic Appl Sci. 2021;10:1–11. doi: 10.1186/S43088-021-00122-X/TABLES/5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hasan M.N., Khalil I., Chowdhury M.A.B., Rahman M., Asaduzzaman M., Billah M., et al. Two decades of endemic dengue in Bangladesh (2000–2022): trends, seasonality, and impact of temperature and rainfall patterns on transmission dynamics. J Med Entomol. 2024;61:345–353. doi: 10.1093/JME/TJAE001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haider N., Vairo F., Ippolito G., Zumla A., Kock RA. Basic reproduction number of Chikungunya virus transmitted by aedes mosquitoes. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:2429–2431. doi: 10.3201/EID2610.190957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]