Highlights

-

•

Online adaptive radiation (oART) is a novel treatment that may improve outcomes.

-

•

Daily oART allows for smaller PTV margins leading to lower doses to organs at risk.

-

•

Daily adaptive plan assessment provides more information than reference plans.

Keywords: Adaptive radiation, Ct based, Prostate cancer, Margin reduction, Dosimetry

Abstract

Background

Online adaptive radiation (ART) is a novel treatment approach that allows for a new daily treatment plan based on cone beam CT (CBCT) imaging. This daily adaptation facilitates precise tumor and organ-at-risk (OAR) localization and minimizes the impact of interfractional motion, allowing for planning target volume (PTV) margin reduction. Isotropic PTV margins for localized non-stereotactic adaptive prostate radiation performed on an ETHOS linear accelerator with HyperSight have been reduced from standard 7 mm to 5 mm. This study assesses the impact of margin reduction by evaluating the dose metrics of patient reference plans, as well as daily treated plans, for 7 mm vs 5 mm PTV margins.

Methods

Patients with prostate cancer receiving moderately hypofractionated adaptive radiation were initially treated with a 7 mm PTV margin (n = 10). This retrospective study generated 5 mm PTV margin treatment plans (n = 10) for these patients for comparison. In addition, a full adaptive 20 fraction treatment course was simulated with margin reduction to identify differences not recognized with reference plan comparison alone.

Results

Bladder V40.8 and V48.6 but not V60 were significantly reduced in 5 mm treatment plans compared to 7 mm treatment plans. However, when daily treated plan data was examined bladder V60 was lower for the 5 mm PTV case. Similarly, rectum doses V24.6-V57 but not V60 were significantly reduced in 5 mm PTV margin treatment plans. Further differences were identified when looking at the daily treated plan data as opposed to simply comparing reference plans.

Significance

In the era of online ART, with significant data available, such as daily treated plan dosimetry, analysis of reference plans alone may not be sufficient. PTV margin reduction, made possible due to the use of online ART, reduced the volume of bladder and rectum receiving <60 Gy, which may reduce toxicity and secondary malignancy risk.

Introduction

Online adaptive radiation (ART) is a treatment paradigm where an adapted treatment plan is generated based on the daily anatomy. Online ART is being investigated across many disease sites and using various treatment platforms [[1], [2], [3], [4]]. Our centre commissioned the first-in-the-world installation of Ethos with HyperSight (Varian Medical Systems, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, DE), combining AI-assisted ART capabilities with next-generation cone-beam CT (CBCT).

Online ART relies on optimization of many daily planning elements including in-room image guidance, deformable image registration, AI-driven auto-contouring, and rapid plan re-optimization and dose calculation [5]. This increase in planning complexity is being explored to account for day-to-day variation in patient anatomy that may be unaccounted for in a static reference plan (i.e. same fluence delivered each day). By imaging, contouring, and replanning daily, online ART reduces the need to account for interfractional variation and the PTV margin can be reduced to account for primarily intrafractional motion. Prior to the use of online ART, margin reduction in prostate cancer radiotherapy, primarily with the use of fiducial marker insertion, has been shown to lead to lower doses to OARs which may correlate to less patient toxicity [[6], [7], [8], [9]]. However, when PTV margins are reduced for non-adaptive radiotherapy, there is increased risk of reduced target coverage due to daily set up uncertainties, as well as motion. It is also unclear how to apply prior data regarding margin reduction to online ART as the target volumes can change daily. Margin reduction using online ART has been shown to lead to lower doses to OARs in bladder cancer, anal canal, rectal cancer and prostate cancer (using MRI-based online ART) [[10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]].

For localized prostate cancer, moderately hypofractionated radiation (60 Gy in 20 fractions) has become a commonly used dose regimen. Standard PTV margins for localized prostate irradiation range from 5 mm to 10 mm, with 7 mm used most [[16], [17], [18], [19]]. At our centre, a 7 mm isotropic PTV margin is used around the prostate and proximal seminal vesicles for non-adaptive non-stereotactic localized prostate cancer cases. A local review of shift data from initial prostate patients treated with online ART on ETHOS was conducted showing a 3D vector shift of 1.19 mm with no shifts exceeding 4 mm after 9 mins [20]. In addition, a review of literature was conducted [18,21] and the PTV margin for adaptive non-stereotactic prostate radiation was reduced to 5 mm.

This study compares 7 mm PTV margin reference plans to 5 mm PTV margin reference plans to report on the dosimetric impact of PTV reduction on reference plan dosimetry. As a secondary analysis, a full 20 fraction adaptive treatment course with a 5 mm PTV margin was simulated to compare to a delivered 7 mm PTV treatment course to determine if any differences in dosimetric impact of margin reduction were appreciated compared to simply comparing reference plans. To our knowledge, this is the first in-depth analysis of the impact of margin reduction using CT-based online ART for prostate cancer.

Methods

This project was reviewed by an institutional Research Ethics Board (REB) and full REB review was waived as the project was deemed to be part of institutional quality improvement and safety portfolio.

Patient eligibility

Starting on January 4, 2024, patients with localized intermediate risk prostate cancer were treated with moderately hypofractionated online ART (60 Gy in 20 fractions) using an ETHOS linear accelerator with HyperSight CBCT (Varian Medical Systems). Following initiation of adaptive moderately hypofractionated prostate RT, adaptive stereotactic radiation (36.25 Gy/40 Gy in 5 fractions) was implemented and will not be described in this report. Originally, a 7 mm PTV margin was used (n = 10) and currently patients are being treated with a 5 mm PTV margin.

Planning details

All treatment planning was completed in Ethos Treatment Management (ETM 1.0) or the ETM 1.0 emulator. An RT intent is required for planning which includes a list of clinical goals grouped by priority (Table 1). In addition to the priority group, the relative priority of the constraint within each group is ranked and impacts the optimization accordingly. More information regarding the Intelligent Optimization Engine (IOE) is provided elsewhere [22]. For the reference plan all structures were contoured manually (including prostate and seminal vesicles). The CTV was automatically defined as prostate plus the proximal 1 cm of seminal vesicles. The PTV margin was 7 mm for original reference plans. A 9 or 12 field IMRT plan was generated for each patient. VMAT plans were not used due to the extended time for daily plan optimization as well as inferior plan quality relative to IMRT with ETM 1.0 [23].

Table 1.

Dose constraints, variances, priorities and rank list order for reference treatment planning. P level: 1 = “most important”, 2 = “very important”, 3 = “important”, 4 = “less important”, R = “report values only”.

| OAR | Priority Level | Rank Order | Constraint/Goal | Variance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder | |||||

| V40.8 (%) | 3 | 19 | ≤ 40 % | < 50 % | |

| V48.6 (%) | 2 | 10 | ≤ 20 % | < 25 % | |

| V60 (%) | 2 | 11 | ≤ 5 % | < 7 % | |

| D0.03cc (Gy) | 1 | 4 | ≤ 60 Gy | < 62 Gy | |

| Rectum | |||||

| V24.6 (%) | R | N/A | ≤ 70 % | < 80 % | |

| V32.4 (%) | R | N/A | ≤ 60 % | < 70 % | |

| V40.8 (%) | 3 | 13 | ≤ 50 % | < 60 % | |

| V43.5 (%) | 3 | 14 | ≤ 40 % | < 50 % | |

| V52.8 (%) | 3 | 15 | ≤ 25 % | < 30 % | |

| V57 (%) | 2 | 7 | ≤ 14 % | < 15 % | |

| V60 (%) | 1 | 1 | ≤ 3.0 % | < 4 % | |

| D0.03cc (Gy) | 2 | 8 | ≤ 60 Gy | < 62 Gy | |

| Penile Bulb | |||||

| Dmean (Gy) | 4 | 21 | ≤ 48 Gy | < 52.5 Gy | |

| Femoral Heads | |||||

| V44 (%) | R | N/A | ≤ 5 % | < 7 % | |

| D0.03cc (Gy) | 3 | 16/17 | ≤ 50 Gy | < 52 Gy | |

| Bowel Bag | |||||

| V43.5 (cc) | 3 | 18 | ≤ 195 cc | < 350 cc | |

| V46.2 (cc) | 3 | 12 | ≤ 2cc | < 10 cc | |

| Small Bowel | |||||

| D0.03cc (Gy) | 1 | 5 | ≤ 52 Gy | < 52 Gy | |

| Large Bowel | |||||

| D0.03cc (Gy) | 1 | 6 | ≤ 60 Gy | < 61 Gy | |

| Target Volume | P Level | Rank Order | Constraint/Goal | Variance | |

| CTV | |||||

| V99% (%) | 1 | 3 | ≥ 99 % | > 95 % | |

| PTV | |||||

| V95% (%) | 1 | 2 | ≥ 99 % | > 98 % | |

| V99.9% (%) | 4 | 20 | ≥ 93 % | > 90 % | |

| D0.03cc (%) | 2 | 9 | ≤ 105 % | < 107 % | |

Treatment details

During online ART, a pre-adaptive CBCT is taken and used for the online adaptive replanning. A synthetic CT, used for dose calculation, is generated using the Hounsfield units (HU) of the fan beam CT (FBCT) and the anatomy of the pre-adaptive CBCT. AI derived contours were reviewed and edited as needed by the Radiation Oncologist. Two plans are generated: the scheduled plan (original reference plan calculated on the synthetic CT and daily contours) and the adapted plan (a new plan calculated on the synthetic CT and daily contours attempting to meet the planning directives). Pretreatment QA is performed using an independent dose-calculation QA software: Mobius (Varian Medial System, Palo Alto, CA). A post-adaptive CBCT is taken to ensure no significant anatomical change and to allow for any required shifts to be applied and then treatment is delivered.

Data extraction and statistical analysis

Dosimetric data was extracted from the ten 7 mm PTV margin reference plans in ETM and recorded anonymously. The planning FBCT was then imported into ETM 1.0 to create a new reference plan with a 5 mm PTV margin. The 5 mm PTV margin plans were created with the identical FBCT, contours (except for the PTV), RT intent (i.e. constraints and priorities) and constraint ranking in dose preview as the original 7 mm PTV margin plan for each patient. All statistics were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 10.3.1 for Windows, GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts USA, https://www.graphpad.com). Dose metrics from treatment plans using 7 mm and 5 mm PTV margins (n = 10) were assessed for normality using the D’Agostino and Pearson test, parametric data were subsequently analyzed using a paired t-test while non-parametric data were assessed with Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test.

Simulation of adaptative treatment

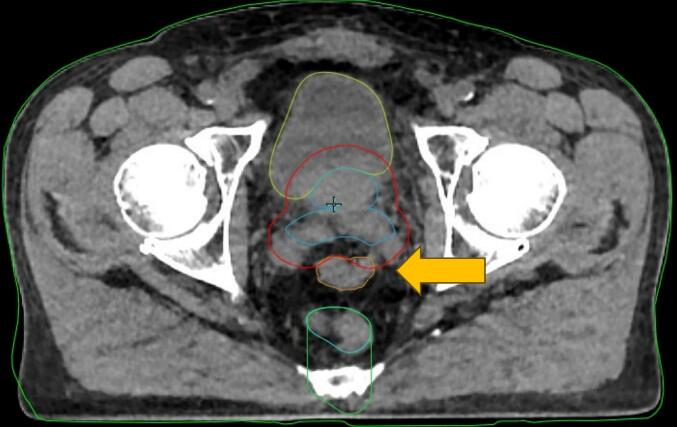

Following review of reference plans, patient 10 was selected for in-depth analysis with simulation of all 20 fractions using the 5 mm PTV margin. The adaptive fractions were simulated in the ETM 1.0 emulator with a radiation oncologist performing and/or reviewing contour edits and selecting plan for treatment. Patient 10 was selected because they had a loop of large bowel falling close to the superior edge of the PTV daily resulting in challenging anatomy (Fig. 1). This anatomy resulted in variable PTV sparing depending on bowel proximity and the study team also noticed bladder constraints were harder to achieve and hypothesized this was due to the inability to allow dose spill posteriorly (at the level of the seminal vesicles) due to the presence of the large bowel loop.

Fig. 1.

Axial HyperSight CBCT of fraction 8 for patient 10 showing large bowel (orange arrow and contour) loop falling inferiorly and abutting superior PTV (red contour) at level of seminal vesicles. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Results

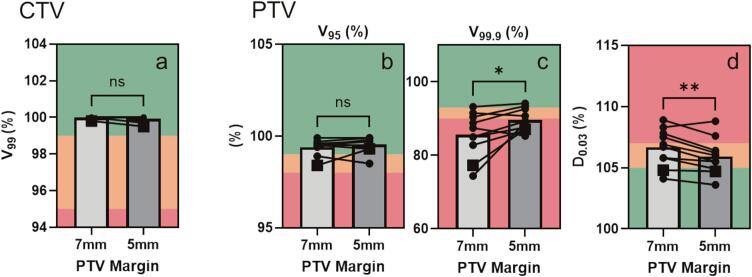

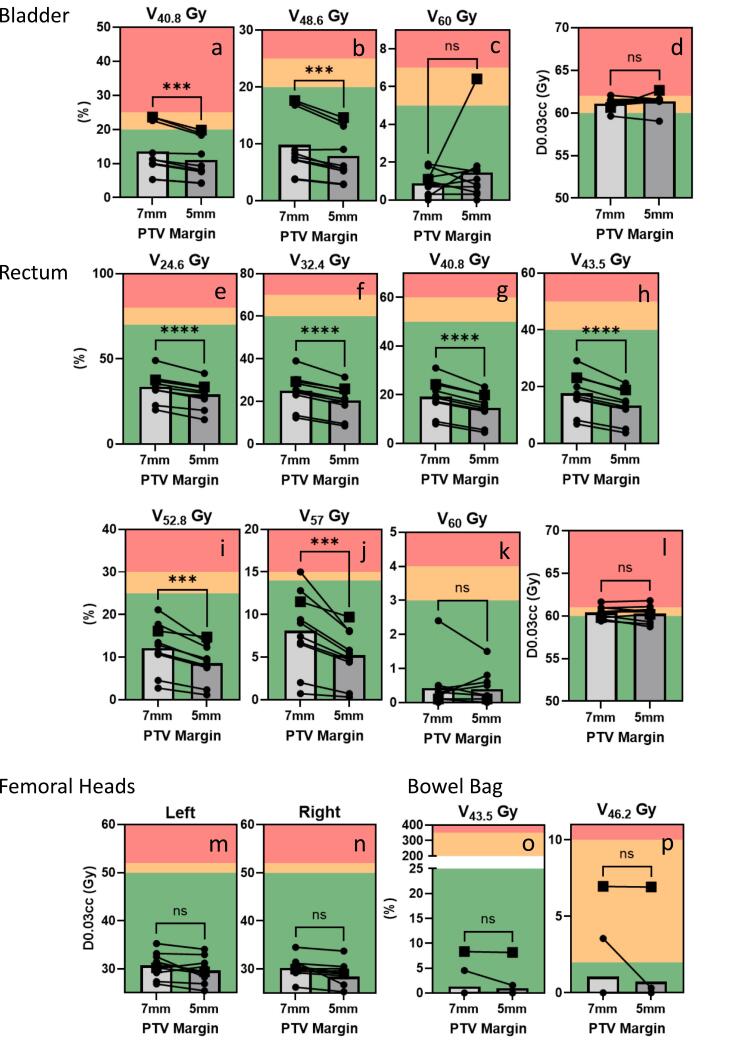

Dosimetric data was extracted from ten 7 mm PTV margin reference plans and compared to dosimetric data when a 5 mm PTV margin was used instead (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Target volume metrics in treatment plans using either 7 mm or 5 mm PTV margins. A) CTV V99%. B) PTV V95% C) PTV V99.9 % D) PTV D0.03 cc. Dose goals: green denotes that a priori goal is met, yellow denotes the goal is marginally met, and red denotes that the treatment plan has failed to meet the dose goal. Data from patient 10 (i.e. Patient selected for sub-analysis) is denoted with the square icon. Significance determined for parametric data using paired t-test and for non-parametric data Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test; p < 0.05*, p < 0.001**, p < 0.0001***; n = 10. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 3.

OAR metrics for reference plans using 7 mm or 5 mm PTV margins. Goals: green denotes that a priori goal is met, yellow denotes the goal is marginally met, and red denotes that the treatment plan has failed to meet the dose goal. Significance determined for parametric data using paired t-test and for non-parametric data Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test; p < 0.05*, p < 0.001**, p < 0.0001***; n = 10. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Table 2.

Target volume and OAR dosimetry for treatment plans using 7 mm vs 5 mm PTV margins.

|

Mean |

Mean of Difference | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OAR | Priority | n | 7 mm | 5 mm | p-value | |||

| Bladder | ||||||||

| V40.8 (%) | 3 | 10 | 13.57 | 11.1 | −2.47 | 0.0005 | *** | |

| V48.6 (%) | 2 | 10 | 9.84 | 7.85 | −1.99 | 0.0007 | *** | |

| V60 (%) | 2 | 10 | 0.89 | 1.46 | 0.57 | 0.3434 | ||

| D0.03 (Gy) | 1 | 10 | 61.11 | 61.34 | 0.237 | 0.3267 | ||

| Rectum | ||||||||

| V24.6 (%) | R | 10 | 33.68 | 28.98 | −4.7 | <0.0001 | **** | |

| V32.4 (%) | R | 10 | 24.97 | 20.48 | −4.49 | <0.0001 | **** | |

| V40.8 (%) | 3 | 10 | 19.12 | 14.64 | −4.48 | <0.0001 | **** | |

| V43.5 (%) | 3 | 10 | 17.59 | 13.32 | −4.27 | <0.0001 | **** | |

| V52.8 (%) | 3 | 10 | 12.09 | 8.56 | −3.53 | 0.0002 | *** | |

| V57 (%) | 2 | 10 | 8.1 | 5.2 | −2.9 | 0.001 | *** | |

| V60 (%) | 1 | 10 | 0.43 | 0.39 | −0.04 | 0.7509 | ||

| D0.03 (Gy) | 2 | 10 | 60.38 | 60.26 | −0.116 | 0.4549 | ||

| Penile Bulb | ||||||||

| Dmean (Gy) | 4 | 10 | 18.03 | 19.81 | 1.779 | 0.5692 | ||

| Right Femoral Head | ||||||||

| D0.03 (Gy) | R | 10 | 30.17 | 28.39 | −1.775 | 0.0576 | ||

| Left Femoral Head | ||||||||

| D0.03 (Gy) | R | 10 | 30.73 | 29.67 | −1.052 | 0.0727 | ||

| Bowel Bag | ||||||||

| V43.5 (%) | 3 | 10 | 1.284 | 0.968 | −0.316 | 0.3127 | ||

| V46.2 (%) | 3 | 10 | 1.05 | 0.722 | −0.328 | 0.3372 | ||

| Mean | Mean of Difference | |||||||

| Target Volume | Priority | n | 7 mm | 5 mm | p-value | |||

| CTV | ||||||||

| V99 (%) | 1 | 10 | 99.98 | 99.92 | −0.06 | 0.1679 | ||

| PTV | ||||||||

| V95 (%) | 1 | 10 | 99.39 | 99.54 | 0.15 | 0.2126 | ||

| V99.9 (%) | 4 | 10 | 85.58 | 89.58 | 4 | 0.0298 | * | |

| D0.03 (%) | 2 | 10 | 106.7 | 105.9 | −0.74 | 0.0046 | ** | |

CTV/PTV dosimetry comparison

As would be expected, the 99.9 % isodose covers a significantly greater percent of the target in 5 mm PTV margin treatment plans vs 7 mm PTV margin plans (5 mm plan 89.58 %, 7 mm 85.58 %; Fig. 2c; Table 2). PTV D0.03 cc is significantly reduced in treatment plans using a 5 mm PTV margin compared to a 7 mm PTV margin (Fig. 2d, Table 2); however, the magnitude of this difference is relatively small at 0.74 %.

OAR dose comparison

The volume of bladder receiving 48.6 Gy and 40.8 Gy was significantly reduced for 5 mm PTV margin plans compared to 7 mm PTV margin plans (Fig. 3a–b, Table 2). Bladder V60Gy and D0.03 cc were both not significantly different between treatment plans using 7 mm PTV margin vs 5 mm PTV margin (Fig. 3c–d, Table 2).

The volume of rectum receiving 57 Gy, 52.8 Gy, 43.5 Gy, 40.8 Gy, 32.4 Gy and 24.6 Gy were all significantly reduced in the 5 mm PTV margin plans compared to the 7 mm PTV margin plans (Fig. 3e–l). The rectum V60 and D0.03 cc both were not significantly reduced with PTV reduction.

There was no significant difference in dosimetry for penile bulb, femoral heads or bowel bag with margin reduction (Fig. 3m–p, Table 2). Only one case (patient 10, selected for secondary analysis) had large bowel close enough to impact plan dosimetry and there was no impact of margin reduction on large bowel dosimetry, likely due to the constraint of D0.03cc <60–61 Gy being easy to meet, even with 7 mm PTV margin.

Comparison of simulated adaptative treatment

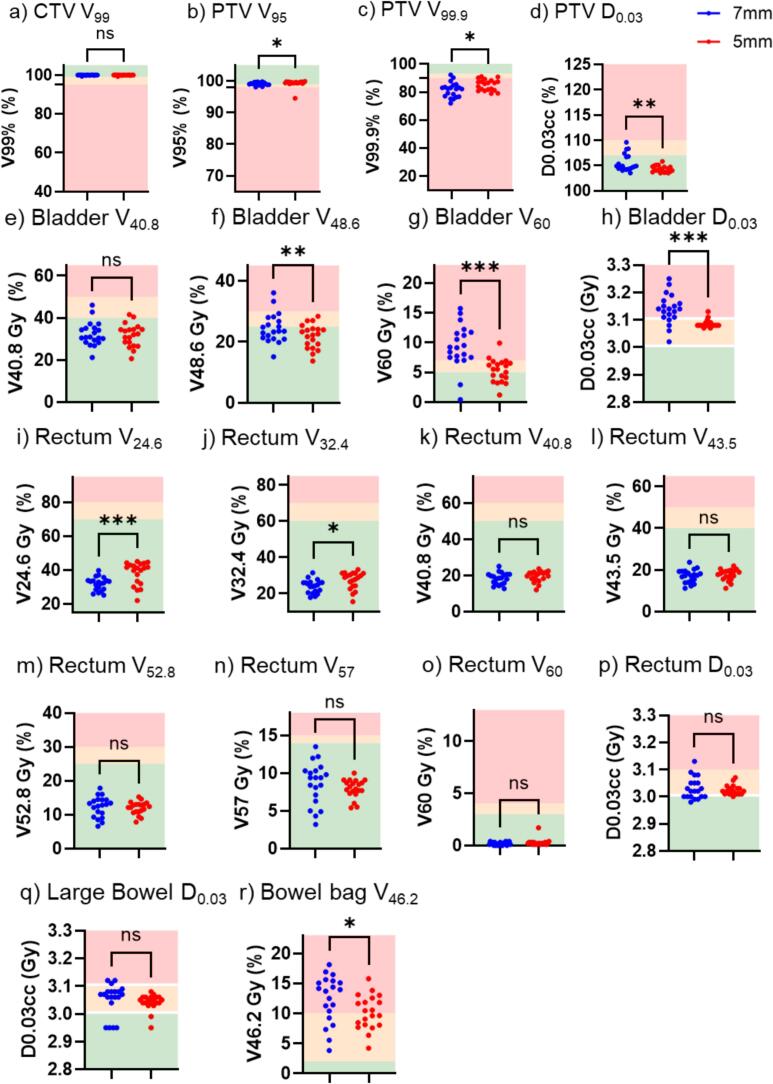

Patient 10 was treated using the scheduled plan for 5/20 fractions when using 7 mm margin vs. 2/20 fractions with the 5 mm margin. Use of a 5 mm PTV margin for daily adaptive sessions led to higher PTV V95 % and PTV V99.9 % coverage, although the magnitude of the change was small (Fig. 4). The PTV D0.03 cc was also significantly lower for the 5 mm PTV fractions (Fig. 4d). Bladder V48.6 Gy, V60 Gy and D0.03 cc was decreased with the use of 5 mm PTV margins (Fig. 4f–h). For this patient, 5 mm PTV margins led to a slightly higher Rectum V24.6 Gy and V32.4 Gy but no significant difference in rectum V40.8 Gy, V43.5 Gy, V52.8 Gy, V57Gy, V60 Gy or D0.03 cc (Fig. 4i–p). The V46.2 Gy to bowel bag was slightly lower with 5 mm PTV margins (Fig. 4r). There was no significant difference in dosimetry for femoral heads, large bowel or penile bulb.

Fig. 4.

Target volume and OAR metrics for 20 treated (or simulated) fractions using either 7 mm or 5 mm PTV margins. OAR absolute doses in Gy are displayed as a per fraction dose. Goals: green denotes that a priori goal is met, yellow denotes the goal is marginally met, and red denotes that the treatment plan has failed to meet the dose goal. Significance determined for parametric data using paired t-test and for non-parametric data Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test; p < 0.05*, p < 0.001**, p < 0.0001***; n = 10. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Discussion

PTV margin reduction from 7 mm to 5 mm led to improvements in reference plans including better coverage of PTV by prescription dose (V99.9 %), lower hot spots (D0.03 cc) and improvements in some OAR constraints (Bladder V40.8, V48.6 and Rectum V57, V52.8, V43.5, V40.8, V32.4 and V24.6). There was no significant change in high priority constraints (P1): CTV V99 %, PTV V95 %, Bladder V60 or Rectum V60. This shows that the ETM 1.0 plan optimization was able achieve these goals (perhaps at the expense of other metrics) in both 7 mm and 5 mm PTV margin workflows. It was the lower priority goals and constraints where the benefit of margin reduction was observed. Margin reduction, leading to smaller target volumes, results in improved dose to nearby OARs as shown by lower volumes of OARs receiving dose levels below the prescription dose. This may have a clinical impact on both acute or late toxicity as well as secondary malignancy risk and requires further investigation.

When performing online ART, the reference plan may never actually be delivered to the patient if the adaptive plan is chosen daily. Therefore, evaluation of the daily dosimetry of the treated plans (whether adapted plan or scheduled plan (i.e. reference plan on that day’s anatomy)) may reveal additional information beyond what’s seen in reference plan comparison alone. For this analysis, patient 10 was chosen for in-depth analysis of the 20 treated 7 mm PTV margin fractions and simulation of a full 20 fraction treatment course using a 5 mm PTV margin was undertaken in the ETM 1.0 emulator. This revealed that changes noted between reference plan dosimetry with margin reduction (Fig. 2, square icons) did not perfectly reflect what happened when all 20 fractions were analyzed. For example, there was no difference in PTV D0.03 cc values between reference plans for this specific patient, but an improvement (p value <0.001) when the individual fractions were analyzed (Fig. 4d). In addition, the reference plan for patient 10 with a 5 mm PTV margin had a high bladder V60 and D0.03 cc however, when the 20 fractions were analyzed, both these metrics were significantly lower for the 5 mm PTV margin fractions with a p value of <0.001 (Fig. 4g,h). Interestingly, the decrease in rectal dosimetry seen in the comparison of reference plans was not seen for patient 10 when all 20 fractions were analyzed and there was actually higher rectum V24.6 and V32.4 with the 5 mm PTV margin (Fig. 4i-p). In addition, there was no difference in bowel bag dosimetry between reference plans but an improvement with the 5 mm PTV margins when all 20 fractions were analyzed (Fig. 4r). These differences illustrate the importance of analyzing fractional data, in addition to reference plan dosimetry, when investigating dosimetric outcomes of online ART.

For patient 10, the scheduled plan was chosen for 5 and 2 fractions, for the 7 mm PTV and 5 mm PTV plans respectively, due to acceptable target coverage and lower bladder V60Gy. Bladder V60Gy was ranked lower on the rank order list which resulted in target coverage being prioritized for the adaptive plans. This rank order was used standardly for our patients, but the authors hypothesize that the presence of the large bowel/bowel bag at the superior PTV led to an anatomical challenge resulting in slightly higher bladder doses due to inability to allow dose wash posteriorly. To account for this, the case could have been replanned with bladder V60Gy ranked above target coverage, if desirable.

For the fractional analysis of the 20 7 mm PTV and 5 mm PTV fractions for patient 10, it was chosen to report out the individual fractional data as opposed to the accumulated delivered dose in the treatment monitoring workspace. This was chosen due to the known contour error in ETM 1.0 in the calculation of the delivered dose to structures when a post-adaptive shift is applied. Improved accuracy of delivered dose could be achieved by manually modifying the target and OAR contours to match the organ positions on the post-adaptive CBCT, a feature which is not currently available in ETM 1.0 and was beyond the scope of this work.

An outlier can be seen in Fig. 3 for Bladder V60 where one 5 mm PTV margin reference plan leads to a higher bladder V60 than its corresponding 7 mm PTV margin plan. This outlier case was identified and examined. There was no identifiable anatomical reason for a higher bladder V60Gy with a smaller PTV margin so what the authors hypothesize is that this plan represented a local minima in plan optimization where a re-run of the plan may have generated an alternate optimization leading to a more favorable bladder V60. However, since this V60 was within the variance and still deemed to be a clinically acceptable reference plan the authors did not pursue repeated optimization. Interestingly, the plan where this occurred was for patient 10, and upon detailed analysis it is seen that although the reference plan bladder V60 was unfavorable, on daily treatment the 5 mm PTV margin lead to a significantly lower bladder V60 (Fig. 4G) again showing that reference plan dosimetry does not tell the whole story when dealing with online ART.

Christiansen et al. investigated the dosimetric impact of PTV margin reduction (from 7 mm to 2–5 mm; prostate margin) for high-risk prostate cancer patients receiving prostate and regional nodal irradiation using MRI-Linac and similarly found reduction in dose to bladder and rectum, more pronounced for lower dose washes [10]. For non-adaptive prostate radiation Arumugam et al. showed that for every 1 mm of PTV reduction from 7 mm to 3 mm there is a decrease of 0.5 ± 1.8 % V60 for the rectum (V60 starting at 3.5 % for 7 mm PTV) and 3 ± 7 % for V60Gy for the bladder (V60 starting at 12 % for 7 mm PTV) [24]. This can be compared to the V60 for bladder and rectum in our 7 mm PTV margin plans using ART as 0.89 % and 0.43 % respectively, which would not allow for much further improvement. While the benefit of margin reduction across many disease sites is known, how this prior data applies in an era of modern radiation planning, including with the use of online ART, requires clarification.

Limitations of this study include the small sample size and therefore statistical significance levels have been indicated with p < 0.0001 (***) being most likely to indicate a true difference. Online adaptive radiation on ETHOS does not allow for the use of triggered imaging to track fiducials and PTV margins should be selected to adequately account for intrafractional motion, in addition intrafractional CBCTs can be taken to monitor for motion. Another limitation is the inability to use dose accumulation to overlay daily plans to get an accurate view of the total delivered dose due to the uncertainty in the registration of daily CBCTs, especially when shifts are applied after the initial CBCT acquisition. To account for this, daily fractional data was extracted and analyzed individually. In addition, the OAR doses are based on contours from the initial CBCT prior to the adaptive workflow and contours were not modified based on the pre-treatment CBCT so the doses could vary if the anatomy changed significantly during the adaptive workflow. An additional limitation of this study, and of most current online ART, is the inability to dose calculate directly on the daily image necessitating the use of a synthetic CT. It has, however, been determined that HyperSight CBCT images provide sufficient HU accuracy for dose calculation and future versions of ETM will allow for direct dose calculation on daily HyperSight CBCT [25]. Future work in this field should seek to capture patient toxicity data from margin reduction due to online ART as well as assess the variation between reference plan dosimetry and cumulative daily treated plan dosimetry.

Conclusion

Online ART is a novel step forward in terms of radiation treatment precision that comes with a significant investment of time and resources compared to standard radiation therapy. Performing ART allows for PTV margin reduction, without the use of fiducial markers, as inter-fractional variability is removed by performing daily re-contouring and re-planning. Our work shows that PTV margin reduction for non-stereotactic online adaptive prostate cancer radiation from 7 mm to 5 mm reduces the volume of bladder and rectum receiving <60 Gy (as well as potentially bladder V60Gy, as shown in the secondary analysis of individual fractions), which may reduce toxicity or secondary malignancy risk. In the era of online ART, with significantly more data available, such as daily treated plan dosimetry, analysis of reference plans alone may not tell the whole story. Analyzing the daily treated plans can create a more accurate picture of what dose the patient received based on their changing daily anatomy.

Funding statement

Work on this project was funded by the CARO-CROF Pamela Catton Summer Studentship Award.

Data statement

Patient level data for this study is not available due to data sharing restrictions of our organization.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Margaret L. Dahn: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. R.Lee MacDonald: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Investigation, Data curation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Amanda Cherpak: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Stefan Allen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Hannah M. Dahn: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Resources, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: [Amanda Cherpak, and Robert Lee MacDonald report honoraria, consulting fees, and support for attending meetings, and hold research grants with financial support from Varian Medical Systems. Hannah Dahn reports speaker fees from Varian Medical Systems. Margaret Dahn and Stefan Allen declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper].

Contributor Information

Margaret L. Dahn, Email: meg.dahn@dal.ca.

Hannah M. Dahn, Email: Hannah.dahn@nshealth.ca.

References

- 1.Ng J., Gregucci F., Pennell R.T., Nagar H., Golden E.B., Knisely J.P.S., et al. MRI-LINAC: a transformative technology in radiation oncology. Front Oncol. 2023;27:13. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1117874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu H., Schaal D., Curry H., Clark R., Magliari A., Kupelian P., et al. Review of cone beam computed tomography based online adaptive radiotherapy: current trend and future direction. Radiat Oncol. 2023;18(1):144. doi: 10.1186/s13014-023-02340-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lavrova E., Garrett M.D., Wang Y.F., Chin C., Elliston C., Savacool M., et al. Adaptive radiation therapy: a review of CT-based techniques. Radiol Imaging Cancer. 2023;5(4) doi: 10.1148/rycan.230011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avkshtol V., Meng B., Shen C., Choi B.S., Okoroafor C., Moon D., et al. Early experience of online adaptive radiation therapy for definitive radiation of patients with head and neck cancer. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2023;8(5) doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2023.101256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim-Reinders S., Keller B.M., Al-Ward S., Sahgal A., Kim A. Online adaptive radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol* Biol *Phys. 2017;99(4):994–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gauthier I., Carrier J.F., Béliveau-Nadeau D., Fortin B., Taussky D. Dosimetric impact and theoretical clinical benefits of fiducial markers for dose escalated prostate cancer radiation treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol* Biol* Phys. 2009;74(4):1128–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammoud R., Patel S.H., Pradhan D., Kim J., Guan H., Li S., et al. Examining margin reduction and its impact on dose distribution for prostate cancer patients undergoing daily cone-beam computed tomography. Int J Radiat Oncol* Biol* Phys. 2008;71(1):265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang S.H., Catton C., Jezioranski J., Bayley A., Rose S., Rosewall T. The effect of changing technique, dose, and PTV margin on therapeutic ratio during prostate radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol* Biol* Phys. 2008;71(4):1057–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumarasiri A., Chetty I.J., Devpura S., Pradhan D., Aref I., Elshaikh M.A., et al. Radiation therapy margin reduction for patients with localized prostate cancer: a prospective study of the dosimetric impact and quality of life. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2024;25(3) doi: 10.1002/acm2.14198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christiansen R.L., Dysager L., Hansen C.R., Jensen H.R., Schytte T., Nyborg C.J., et al. Online adaptive radiotherapy potentially reduces toxicity for high-risk prostate cancer treatment. Radiother. Oncol. 2022;167:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2021.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foroudi F., Wong J., Kron T., Rolfo A., Haworth A., Roxby P., et al. Online adaptive radiotherapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: results of a pilot study. Int J Radiat Oncol* Biol* Phys. 2011;81(3):765–771. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Åström L.M., Behrens C.P., Storm K.S., Sibolt P., Serup-Hansen E. Online adaptive radiotherapy of anal cancer: normal tissue sparing, target propagation methods, and first clinical experience. Radiother Oncol. 2022;176:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2022.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kensen C.M., Janssen T.M., Betgen A., Wiersema L., Peters F.P., Remeijer P., et al. Effect of intrafraction adaptation on PTV margins for MRI guided online adaptive radiotherapy for rectal cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2022;17(1):110. doi: 10.1186/s13014-022-02079-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kron T., Wong J., Rolfo A., Pham D., Cramb J., Foroudi F. Adaptive radiotherapy for bladder cancer reduces integral dose despite daily volumetric imaging. Radiother Oncol. 2010;97(3):485–487. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grønborg C., Vestergaard A., Høyer M., Söhn M., Pedersen E.M., Petersen J.B., et al. Intra-fractional bladder motion and margins in adaptive radiotherapy for urinary bladder cancer. Acta Oncol (Madr) 2015;54(9):1461–1466. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2015.1062138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dearnaley D., Syndikus I., Mossop H., Khoo V., Birtle A., Bloomfield D., et al. Conventional versus hypofractionated high-dose intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer: 5-year outcomes of the randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 CHHiP trial. LancetOncol. 2016;17(8):1047–1060. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30102-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yartsev S., Bauman G. Target margins in radiotherapy of prostate cancer. Br J Radiol. 2016;89(1067) doi: 10.1259/bjr.20160312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Byrne M., Teh A.Y.M., Archibald-Heeren B., Hu Y., Rijken J., Luo S., et al. Intrafraction motion and margin assessment for ethos online adaptive radiotherapy treatments of the prostate and seminal vesicles. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2024;9(3) doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2023.101405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brand V.J., Milder M.T.W., Christianen M.E.M.C., Hoogeman M.S., Incrocci L. Seminal vesicle inter- and intra-fraction motion during radiotherapy for prostate cancer: a review. Radiother Oncol. 2022;169:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2022.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cherpak A., Degiobbi J., Macdonald L., Riopel A., Robar J., Zhan K., et al. Pulling the trigger: transitioning from triggered imaging with auto beam-hold to fiducial. Med Phys. 2024;51(8):5785–5835. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ray X., Moazzezi M., Bojechko C., Moore K.L. Data-driven margin determination for online adaptive radiotherapy using batch automated planning. Int J Radiat Oncol* Biol* Phys. 2020;108(3):e370. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Archambault Y., Boylan C., Bullock D. Making on-line adaptive radiotherapy possible using artificial intelligence and machine learning for efficient daily re-planning. Med PhysInt J. 2020;8:77–86. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sibolt P., Andersson L.M., Calmels L., Sjöström D., Bjelkengren U., Geertsen P., et al. Clinical implementation of artificial intelligence-driven cone-beam computed tomography-guided online adaptive radiotherapy in the pelvic region. Phys Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2021;17:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.phro.2020.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arumugam S., Wong K., Do V., Sidhom M. Reducing the margin in prostate radiotherapy: optimizing radiotherapy with a general-purpose linear accelerator using an in-house position monitoring system. Front Oncol. 2023;13:13. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1116999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robar J.L., Cherpak A., MacDonald R.L., Yashayaeva A., McAloney D., McMaster N., et al. Novel technology allowing cone beam computed tomography in 6 seconds: a patient study of comparative image quality. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2024;14(3):277–286. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2023.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]