ABSTRACT

Klebsiella pneumoniae is primarily an opportunistic pathogen known for causing healthcare-associated infections in individuals with significant risk factors and comorbidities. These bacteria are typically multidrug-resistant (MDR), a phenotype conferred in part by the production of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases and/or carbapenemases. By comparison, so-called hypervirulent K. pneumoniae (hvKp) are defined by their ability to cause severe community-acquired infections in otherwise healthy individuals. Although hvKp lineages have historically not been MDR, there has been a recent emergence of strains with both hypervirulence and multidrug resistance phenotypes. Treatment of infections caused by MDR K. pneumoniae can be difficult, and new preventative measures are needed. As a step toward the development of a vaccine directed to prevent or moderate infections caused by these pathogens, we tested the ability of capsule polysaccharide (CPS) derived from eight selected K. pneumoniae capsule types (KLs) to elicit rabbit antibodies that recognize important KLs isolated from human infections. Seventy-one out of 84 (84.5%) contemporary K. pneumoniae clinical isolates tested were recognized by CPS-specific rabbit antisera. There was the unexpected binding of the antibodies to some isolates with KLs not included in the CPS-antigen cocktails. Notably, rabbit IgG purified from CPS-specific antisera promoted and/or enhanced human PMN bactericidal activity toward all but one of the selected clinical isolates that were not killed by PMNs outright (in the absence of specific antibody). These data provide support to the idea that a CPS-antigen cocktail could be developed to protect against the K. pneumoniae KLs that are the most frequent cause of human infections.

IMPORTANCE

Klebsiella pneumoniae is among the leading causes of death by infectious agents. Many of the prominent K. pneumoniae lineages are resistant to multiple classes of antibiotics, and options for treatment are limited. New countermeasures that prevent infections are needed. Here we tested the ability of capsule polysaccharide (CPS) antigen mixtures (or cocktails) to elicit rabbit antibodies that recognize K. pneumoniae from a large collection of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing clinical isolates. Importantly, these antibodies had the ability to promote opsonophagocytic killing by human PMNs. Our results provide proof-of-concept for a CPS vaccine cocktail approach that could be developed to prevent infections caused by the most important K. pneumoniae lineages.

KEYWORDS: CPS-conjugate, carbapenem-resistance, antibiotic resistance, immunization, opsonophagocytosis

INTRODUCTION

Klebsiella pneumoniae is an important cause of human infections globally (1). The microbe is ranked among the top four bacterial pathogens associated with infection-related deaths and estimated years of life lost (1). Deaths occur most often early (0–5 years) or late in life, consistent with the role of K. pneumoniae as a commensal microbe and opportunistic pathogen (1). For example, Verani et al. reported recently that K. pneumoniae is associated with ~21% of child deaths in seven countries located in sub-Saharan Africa (2). Boceska et al. found that K. pneumoniae was the most abundant gram-negative bacterium isolated from neonatal sepsis among low- and middle-income countries (3), and Kumar et al. reported the pathogen as the leading cause of newborn sepsis deaths globally (4). The high prevalence of K. pneumoniae infections is coupled with antibiotic resistance, and notably, K. pneumoniae often harbor plasmids that encode extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) and carbapenemases (5). Indeed, most of the isolates recovered by Verani et al. were resistant to antibiotics recommended for treatment of severe infections, and up to 30% were resistant to carbapenem antibiotics (2). Thus, treatment options are limited, and antibiotic therapy for patients with severe infections has a relatively high rate of failure. In the United States, strains classified as sequence type (ST) 307 (KL102) and ST258 (KL106/107) are the most prominent clinical isolates that encode ESBLs and/or carbapenemases (6, 7). Infections and syndromes caused by these organisms include urinary tract and intraabdominal infections, pneumonia, and bacteremia, and occur primarily in healthcare settings in individuals with significant comorbidities and risk factors for infection. Strains associated with these infections have been termed classical K. pneumoniae (cKp) by Russo et al. (8, 9).

By comparison, strains that cause invasive infections in the community (outside of healthcare settings) in otherwise healthy individuals have been described as hypervirulent K. pneumoniae (hvKp) (8, 9). These infections often manifest as abscesses in major organs such as the liver, lungs, and kidneys and may be followed by metastatic spread (10). HvKp strains were initially identified as having a hypermucoviscous (hmv) colony phenotype on solid culture media, but subsequent studies have shown that some hvKp clinical isolates lack an hmv phenotype (10, 11). The hmv phenotype was originally linked to enhanced production of capsule polysaccharide (CPS), a K. pneumoniae surface structure that is essential for evasion of host defenses and the hypervirulence phenotype. However, our understanding of the role of hmv changed in recent years. Walker et al. identified rmpD, a gene located in the rmp operon between rmpA and rmpC, as essential for the hmv phenotype but not CPS production in K. pneumoniae (12, 13). The finding that rmpA regulates expression of both rmpD and rmpC (a gene required for CPS biosynthesis) provides a possible explanation for previous ambiguity with hmv and CPS production (13). Although the hmv phenotype requires CPS synthesis machinery (14), CPS production is independent of hmv (12). The studies by Walker et al. also revealed that hmv contributes to immune evasion by blocking the binding and uptake of K. pneumoniae by phagocytic cells (12), a finding supported by Mike et al. by using human lung epithelial cells (15). Thus, hmv and CPS each contribute to immune evasion by K. pneumoniae.

Clinical isolates from patients with hvKp infections harbor a virulence plasmid that contains genes and gene loci involved in siderophore biosynthesis (iutA, iroBCDN, iucABCD) and molecules that regulate capsule production; rmpA within the rmpADC operon, as described above, and/or rmpA2 (9, 16, 17). The most abundant hvKp clinical isolates are often classified as CPS type 1 (KL1)/ST23 or type 2 (KL2)/ST86 or ST65, although this can vary based on geographic location (18, 19). Compared with cKp, infection with strains identified as hvKp is far less frequent except in China and Vietnam, in which hvKp infections have been reported as 46–69% and 39% of all K. pneumoniae infections (9, 18, 19). HvKp clinical isolates were historically susceptible to antibiotics, an important attribute that likely influenced treatment outcomes (19).

Notably, there has been a recent emergence of strains with both MDR and hypervirulence characteristics, so-called MDR-hvKp. For example, Gu et al. reported ST11 carbapenem-resistant and hvKp recovered from patients in 2016 (20). This MDR hvKp ST11 strain developed from the acquisition of a virulence plasmid by cKp (carbapenem-resistant ST11) (20). Inasmuch as these strains can cause severe infections for which treatment options are limited, there is a need to develop alternative therapeutic or preventative countermeasures. A vaccine that targets K. pneumoniae CPS is one such preventative approach that has been evaluated previously (reviewed by Choi et al. [21]). Previous studies by Cryz et al. reported that 25 K. pneumoniae capsule serotypes accounted for ~70% of the bacteremia isolates recovered from patients in 1979–1984 (22). The authors concluded a polyvalent CPS-based vaccine is a feasible approach for protection against a majority of bacteremia capsule serotypes of that era (22). Indeed, multiple studies from the mid-1980s to mid-1990s demonstrated that a polyvalent CPS-based vaccine elicits antibodies specific for K. pneumoniae CPS and is safe in humans (23–27). Despite these results, the vaccine was ultimately not moved forward.

At present, passive and active vaccine approaches are directed largely at the CPS or lipopolysaccharide (LPS, O-antigen). For example, Pennini et al. and Cohen et al. demonstrated that monoclonal antibodies specific for K. pneumoniae LPS O-antigens confer protection against death in mouse infection models (28, 29). Diago-Navarro et al. showed that mouse monoclonal antibodies specific for K. pneumoniae K1 CPS decreased K. pneumoniae virulence in mouse infection models (30, 31). Consistent with the findings in mouse infection models, Kobayashi et al. reported that antibodies specific for ST258 CPS promote opsonophagocytic killing of ST258 clinical isolates by human neutrophils (32). Studies by Hegerle et al. showed that administration of polyclonal antisera specific for K. pneumoniae O-antigen conjugates protected mice against death following intravenous K. pneumoniae infection (33). Recent studies have also tested the ability of purified CPS to elicit protection against severe K. pneumoniae infection. For instance, Malachowa and colleagues demonstrated that vaccination of non-human primates with purified ST258 CPS decreased the severity of ST258 pneumonia compared with control animals (34), and Feldmann et al. reported that vaccination with CPS bioconjugates protected mice against death in an experimental model of hvKp infection (35).

Although progress has been made, our understanding of the ability of purified K. pneumoniae CPS to elicit antibodies that bind contemporary KL types remains incompletely determined. To provide additional insight on this topic, we tested rabbit antisera specific to CPS from eight selected cKp and hvKp clinical isolates for immunogenicity and function against a broader collection of clinical isolates with varied KL types.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Generation of CPS-specific rabbit polyclonal antisera

CPS from eight selected clinical isolates was purified in two separate groups/batches (labeled hvKp and cKp), and contaminating endotoxin was inactivated using previously published methods (36–38) (Table 1). CPS alone does not elicit long-lived immune responses because the response is T-cell independent and the B-cell response is limited (39). To address this issue, carrier proteins such as CRM197 (a diphtheria toxoid) can be covalently linked to CPS vaccine antigens to elicit T-cell dependent immune responses and long-term immunity (39, 40). In our current study, we used unconjugated CPS and CPS conjugated with recombinant CRM197 (CPSCRM) to produce rabbit antisera for up to 14 weeks after initial immunization (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

K. pneumoniae clinical isolatesa

| Isolate | MLST | Capsule type (KL/K type) |

O-antigen type | wzi | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 53370 | 23 | KL1 (K1) | O1 | wzi1 | hvKp |

| 56575 | 86 | KL2 (K2) | O1 | wzi2 | hvKp |

| 56661 | 147 | KL64 (K64) | O2 | wzi64 | MDR-hvKp |

| 53374 | 11 | KL64 (K64) | O2 | wzi64 | MDR-hvKp |

| 50220 | 258 | KL51 (K51) | O3b | wzi50 | cKp |

| 50219 | 258 | KL106 | O2afg | wzi29 | cKp |

| 30684 (NJST258_2) | 258 | KL107 | O2afg | wzi154 | cKp |

| 56203 | 307 | KL102 | O2afg | wzi173 | cKp |

cKp, classical K. pneumoniae; hvKp, hypervirulent K. pneumoniae; MDR hvKp, multidrug resistant and hypervirulent K. pneumoniae.

Fig 1.

Production of CPS-specific antisera in rabbits. Blood and serum samples (Blood) were obtained from rabbits at the time points indicated. Two rabbits were immunized with each CPS cocktail (four cocktails in total comprised of CPS or CPSCRM derived from strains in Table 1) at weeks 0, 3, 6, and 10, as described in Materials and Methods. The resulting rabbit antisera were labeled as αhvKp, αhvKpCRM, αcKp, and αcKpCRM. CFA, complete Freund’s Adjuvant; CPS, capsule polysaccharide; CPSCRM, capsule polysaccharide conjugated to recombinant CRM197; IFA, incomplete Freund’s Adjuvant; PI, preimmune.

We next measured rabbit antibody titers using flow cytometry (Fig. 2 and 3). Isolate 56661 (KL64/ST147) was included in both immunization groups as a reference. Unconjugated CPS from hvKp and MDR hvKp isolates 53370, 56575, 53374, and 56661 failed to elicit production of CPS-specific antibody by rabbits, or the animals produced limited levels of specific antibody (Fig. 2). By comparison, rabbits immunized and boosted with the CPSCRM cocktail from these isolates developed relatively high titer antisera (labeled as αhvKpCRM) against each isolate (Fig. 2). These results are consistent with the known ability of CPS conjugates such as CRM197 to elicit improved and long-lived (T-cell dependent) immune responses to CPS (41, 42). Rabbits immunized with a CPSCRM cocktail derived from cKp isolates 30684, 50219, 50220, 56203, and 56661 also developed relatively high titer antisera (labeled as αcKpCRM) specific for each isolate by flow cytometry (Fig. 3). Unexpectedly, rabbits immunized with a cocktail of unconjugated CPS also developed high titers of antibodies against each of the three ST258 isolates (30684, 50219, 50220) and 56661, albeit there were noted differences in the kinetics of antibody generation toward capsule antigens from 50219 and 56661 (Fig. 3). It is possible that the presence of TLR ligand contaminants in the CPS cocktail, as has been shown previously for commercial pneumococcal CPS preparations, enhanced rabbit antibody responses to the cKp CPS cocktail (43). This result merits further investigation, and identification of a specific mechanism that could assist vaccine development for K. pneumoniae.

Fig 2.

Titer of antisera generated with CPS from hvKp or MDR hvKp strains. Four rabbits were immunized with CPS (two animals) or CPS conjugated to recombinant CRM197 (CPSCRM; two animals) derived from isolates 53370, 56575, 53374, and 56661 as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Antibody titers were estimated by flow cytometry at the indicated time after immunization (3–14 weeks). (B) Preimmune sera were tested for immunoreactivity with clinical isolates using flow cytometry. Data in panel (A) are presented as the averaged Geo Mean FL of sera from the two rabbits immunized with CPS or two rabbits immunized with CPSCRM. Panel (B) shows Geo Mean FL data of preimmune sera from each of the four rabbits at a 1:2,000 dilution (the lowest dilution used for panel (A)). The Geo Mean FL of the preimmune sera from these four rabbits was 25–137, depending on the strain tested. αhvKp, rabbit antisera specific for CPS derived from 53370, 56575, 53374, and 56661. αhvKpCRM, rabbit antisera specific for CPSCRM derived from 53370, 56575, 53374, and 56661.

Fig 3.

Titer of antisera generated with CPS from cKp strains. Four rabbits were immunized with CPS (two animals) or CPS conjugated to recombinant CRM197 (CPSCRM; two animals) derived from isolates 30684, 50219, 50220, 56203, and 56661 as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Antibody titers were estimated by flow cytometry at the indicated time after immunization (3–14 weeks). (B) Preimmune sera were tested for immunoreactivity with clinical isolates using flow cytometry. (C) Representative histogram overlay of flow cytometer data. Bacteria (strain 50220) were stained with secondary antibody alone (black line), preimmune sera (1:2,000 dilution) plus secondary antibody (green line), or immune sera (1:2,000 dilution of αcKpCRM from week 11) plus secondary antibody (purple line) as indicated. Data in panel (A) are the Geo Mean FL of sera from two rabbits immunized with CPS or two rabbits immunized with CPSCRM. Panel (B) shows Geo Mean FL data of preimmune sera from each of the four rabbits tested at a 1:2,000 dilution (the lowest dilution used for panel (A)). The Geo Mean FL of the preimmune sera from these four rabbits was 22–263, depending on the strain tested. αcKp, rabbit antisera specific for CPS derived from 30684, 50219, 50220, 56203, and 56661; αcKpCRM, rabbit antisera specific for CPSCRM derived from 30684, 50219, 50220, 56203, and 56661.

Recognition of K. pneumoniae clinical isolates by CPS-specific rabbit antisera

Inasmuch as αhvKpCRM and αcKpCRM were optimal (compared with αhvKp and αcKp) for binding to all strains from which CPS was obtained, we used these antisera to test recognition/binding of 76 selected clinical isolates from recent archived collections at the Center for Discovery and Innovation, and this includes >1,000 genomically characterized ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae clinical isolates. We selected capsule types (KLs) that in aggregate represented ~58% of clinical isolates in this ESBL strain collection. To test the specificity of the antisera, we evaluated the binding of αhvKpCRM and αcKpCRM to multiple isolates with KLs identical to that of the strains used to produce CPS antigens (Fig. 4). Indeed, most of the isolates tested were recognized by capsule-type specific antisera regardless of differences in multilocus ST. For example, all KL1 (8), KL51 (7), KL64 (9), KL102 (8), KL106 (3), and KL107 (4/4) isolates tested were recognized by CPS-specific antisera, and all but one of the KL2 (10/11) isolates tested were bound by specific antisera (Fig. 4). Thus, 98% of these isolates (49/50) were recognized by CPS-specific antisera. In addition to these KL types, αhvKpCRM and/or αcKpCRM bound KL151 (5/5), KL114 (5/5), KL15 (5/5), and KL3 (4/5) isolates to varied levels (Fig. 4). A comparison of the published composition and structure of three of these capsule types (KL3, KL15, and KL114; that for KL151 is not known) did not provide a clear explanation for cross-reactivity with αhvKpCRM (44–50). Of all isolates tested (76 query isolates + 8 CPS antigen isolates; 84 in total), 71 (84.5%) were recognized by αhvKpCRM and/or αcKpCRM. These results provide support to the idea that a K. pneumoniae capsule vaccine approach has potential to target the most abundant KL types recovered from human infections.

Fig 4.

Specificity of CPS-specific rabbit antisera. Seventy-six selected K. pneumoniae clinical isolates were evaluated for recognition by CPS-specific rabbit antisera (1:2,000 dilution of αcKpCRM or αhvKpCRM as indicated). Eight clinical isolates used to generate αcKpCRM or αhvKpCRM (Table 1) were included as controls (indicated by asterisks and red text). Test isolates were selected from a larger collection of strains based on the prevalence of KL types and/or were of clinical interest. Data shown are the average Geo Mean FL (×1,000) of two separate flow cytometry experiments. The Geo Mean FL of these samples ranged from 23 to 111,109.

Killing of K. pneumoniae clinical isolates can be enhanced by CPS-specific IgG

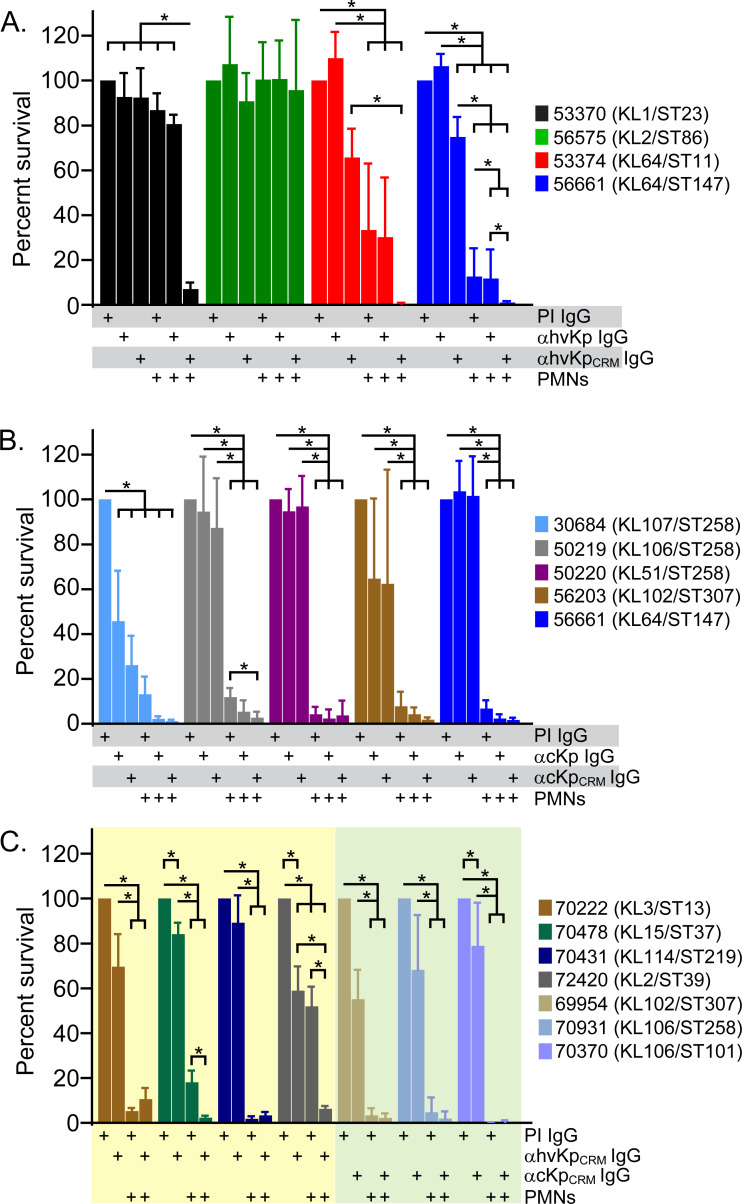

To determine whether antibody surface binding (Fig. 4) confers opsonophagocytic killing, we assessed the ability of CPS-specific antibodies to enhance or promote PMN bactericidal activity (Fig. 5). Inasmuch as CPS-specific rabbit antisera were comprised primarily of IgG (92–99% of surface-bound antibodies), we used purified IgG in PMN phagocytosis assays. We first tested the survival of isolates used to generate CPS-specific antisera (Fig. 5A and B). Notably, the survival of six out of eight isolates was reduced significantly by interaction with human PMNs without added CPS-specific IgG (with 10% NHS) (Fig. 5A through C). For example, the survival of isolate 56203, which is an ESBL-producing ST307/KL102 isolate and representative of the most abundant KL type in the ESBL strain collection, was reduced to 7.8 ± 6.5% of control assays that lack PMNs (P = 0.0003) (Fig. 5B). These results are not unexpected, since human PMNs are the primary cellular defense against bacterial infections and kill most bacteria readily. On the other hand, survival of hvKp isolates 53370 (ST1/KL1) and 56575 (KL2/ST86) was not reduced significantly by interaction with human PMNs alone, findings consistent with our recent studies of PMN-hvKp interaction (51). Compared with assays containing PMNs and preimmune (non-specific) IgG, those with CPS-specific IgG promoted/enhanced killing of isolates 53370, 53374 (ST11/KL64), 56661 (ST147/KL147), and 50219 (ST258/KL106) (Fig. 5A and B). The inability of αhvKpCRM IgG to promote PMN killing of the KL2/ST86 isolate 56575 merits further investigation, since the titer of this antisera was similar to that for other isolates (Fig. 2). Nonetheless, the findings in general underscore the ability of CPS-specific antibody to promote opsonophagocytic killing of K. pneumoniae by PMNs.

Fig 5.

Ability of CPS-specific IgG to promote PMN bactericidal activity. (A through C) Survival of the indicated K. pneumoniae clinical isolates during phagocytic interaction with human PMNs in the presence or absence of CPS-specific IgG (100 µg/mL) was determined as described in Materials and Methods. All assays contained 10% NHS as a source of complement. Plus sign “+” below each bar indicates the components (PMNs, preimmune IgG [PI IgG], and immune IgG [αcKpCRM or αhvKpCRM]) added to that assay well. Data are the mean ± standard deviation of three to five separate experiments (blood donors). Statistics were performed using raw or LogY-transformed CFU data as described in Materials and Methods. *P < 0.05 for the indicated comparisons using a repeated-measures one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s posttest. Each of these 15 isolates produced CPS during culture in vitro.

We next tested the ability of αhvKpCRM or αcKpCRM IgG to promote or enhance serum and PMN bactericidal activity toward selected clinical isolates that were recognized by rabbit antisera but not used in the preparation of CPS antigen cocktail (Fig. 5C). Survival for three of these isolates, 70478, 72420, and 70370, was decreased significantly by CPS-specific IgG in the presence of 10% NHS (present in all assays) (Fig. 5C). These findings are consistent with the ability of antibodies to promote complement-mediated killing of some strains of K. pneumoniae. As with the eight isolates tested in Fig. 5A and B, the survival of the seven clinical isolates tested was reduced significantly during phagocytic interaction with human PMNs, albeit to varied levels (e.g., survival was 0.3 ± 0.09% for isolate 70370 compared with 52.0 ± 8.8% for 72420) (Fig. 5C). Notably, the addition of CPS-specific IgG enhanced PMN killing of isolates 70478 and 72420 significantly (Fig. 5C). For instance, the survival of isolate 72420, a KL2/ST39 isolate, decreased from 52.0 ± 8.8% in the presence of non-specific IgG to 6.3 ± 1.3% with CPS-specific IgG (P = 0.003) (Fig. 5C). The ability of CPS-specific antibody to extend the range of opsonophagocytic killing beyond KLs included in the CPS antigen cocktail has the potential to assist in the development of a broadly protective K. pneumoniae vaccine.

Concluding comment

Multiple studies published throughout the 1980s demonstrated K. pneumoniae CPS is well suited as a vaccine antigen (22, 23, 26, 27, 36, 52–55). Notably, 70% of Klebsiella bacteremia isolates from that era were represented by 25 capsule serotypes, and CPS from these serotypes could be prepared readily for use in a vaccine (22, 36). These studies led to the development of a 24-valent K. pneumoniae CPS vaccine that was tested for safety and immunogenicity in humans (24, 25). Four decades later, our findings with contemporary strains, including those that are MDR, are compatible with these previous studies. Indeed, 21 capsule types comprise 75% of all isolates in our contemporary ESBL strain collection, and type-specific antibody promoted phagocytic killing by neutrophils. Our work extends knowledge in this area using a CPS conjugate approach, which promoted relatively broad recognition of K. pneumoniae capsule types and optimal PMN bactericidal activity. The extent to which a K. pneumoniae CPS conjugate vaccine could be developed (e.g., number of KLs to include) to moderate or prevent severe infections merits further investigation. Based on the success of current licensed pneumococcal vaccines, a similar vaccine approach with K. pneumoniae capsule seems feasible.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Purification and analysis of CPS

Characteristics and descriptions of K. pneumoniae clinical isolates used to generate rabbit CPS-specific antisera are provided in Table 1. CPS from K. pneumoniae isolates was extracted and purified from spent culture medium using a method modified from Cryz et al. (36). Bacteria were cultured for 16 h in 500 mL HYEM medium (2% [wt/vol] Hy-Case SF, 0.3% [wt/vol] yeast extract, and 2% [wt/vol] maltose) at 37°C with shaking (220 rpm). Cultures were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 30 min at room temperature (RT), and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 µm polyethersulfone (PES) filter. CPS was precipitated from filtered supernatant by adding 0.5% (final concentration) hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (CETAB; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and stirring for 1 h at RT. Precipitated CPS was centrifuged at 4,200 × g for 30 min at RT, the supernatant was aspirated, and CPS pellet was dissolved in 50 mL of 1 M CaCl2. The CPS solution was stirred for 1–16 h at RT (the time needed to dissolve CPS varied with each isolate). Contaminating nucleic acids were precipitated by adding 25% (vol/vol) ethanol (final concentration) with stirring for 2 h at 4°C. The CPS-containing supernatant was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C to pellet precipitated nucleic acids. CPS was then precipitated from the clarified supernatant by adding 80% (vol/vol) ethanol (final concentration), and CPS was pelleted by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 30 min at RT. The supernatant was discarded, and the CPS pellet was air-dried for 30 min at RT. Dried CPS was suspended in 20 mL sterile Milli-Q water (SMQ) and kept at RT overnight to dissolve completely. Dissolved CPS samples were stored at 4°C until used.

Contaminating (LPS in CPS preparations was inactivated by adding 0.1 M NaOH (final concentration) and 80% (vol/vol) ethanol (final concentration) and incubating for 1 h at 37°C. NaOH was neutralized at the end of the detoxification time by adding acetic acid to a final concentration of 0.1 M. Detoxified samples were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min at RT. The supernatant was aspirated, and the CPS pellet was air-dried for 30 min at RT. The CPS pellet was dissolved in SMQ and dialyzed against 3 L of SMQ in Slide-A-Lyzer dialysis cassettes (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) (20,000 molecular weight cut-off [MWCO]). Buffer was changed two times during dialysis. CPS was then concentrated in an Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA) (100,000 nominal molecular weight limit [NMWL]), by centrifugation at 3,000 × g. Purified CPS was quantified using a standard uronic acid assay (56, 57), and any protein contaminants were determined using a Pierce BCA Protein Assay (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA).

K. pneumoniae isolate 50220 secreted little CPS into the culture medium. Therefore, we modified the method used by Domenico et al. to extract CPS from the bacterial surface (37). CPS preparations extracted with this method had more contaminating protein by comparison, and samples required further purification using gel filtration chromatography. In brief, bacteria were cultured for 16 h in 500 mL Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C with shaking (220 rpm). Cultures were then centrifuged at 17,700 × g for 30 min at 4°C to pellet bacteria. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in extraction buffer (0.1% Zwittergent 3–14 in 50 mM sodium citrate buffer, pH 4.5) to one-tenth of the original culture volume. CPS was extracted for 30 min in a water bath at 42°C. Extracted samples were centrifuged at 17,700 × g for 5 min at 4°C and the CPS-containing supernatant was filtered through a 0.22-µm-pore-size PES filter. CPS samples were stored at 4°C until the gel filtration step. Samples were loaded onto a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 gel filtration column (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA) and fractionated with isocratic elution (buffer = 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5/100 mM NaCl). Fractions were screened for CPS using a uronic acid assay, and CPS-containing fractions were pooled and concentrated to a volume of 20 mL. Subsequent steps for LPS inactivation and buffer exchange were performed as described above. Purified CPS was quantified with a uronic acid assay, and contaminating protein was determined using a Pierce BCA Protein Assay (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA).

Conjugation of recombinant CRM197 to K. pneumoniae CPS

Storage buffer containing EcoCRM, a recombinant CRM197 carrier protein (Fina Biosolutions, Rockville, MD), was exchanged with reaction buffer (200 mM HEPES, pH 8.8) using Amicon Ultra-15 filters (10,000 NMWL). CPS (0.5–2 mg) from each isolate was cyanylated with 10 mg/mL (final concentration) 1-cyano-4-dimethylaminopyridinium tetrafluoroborate (CDAP; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Reaction mixtures were vortexed for 30 s in screw-cap glass vials, followed by the addition of triethylamine (Sigma-Aldrich) at a final concentration of 0.2 M with gentle mixing for 2 min. EcoCRM (0.25–1 mg) in 200 mM HEPES, pH 8.8 (1:1 or 1:2 ratio of EcoCRM:CPS) was added to each vial. The conjugation reactions were rotated slowly (6 rpm) for 40 h at RT and protected from light. CPS conjugated to EcoCRM (CPSCRM) was dialyzed against SMQ and concentrated in Amicon filters as described above. CPSCRM was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and protein visualized with Gel Code Blue Stain (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). CPS was quantified with a uronic acid assay, and contaminating protein was determined using a Pierce BCA Protein Assay.

Anti-CPS antibody production in rabbits

Antigen preps were generated by combining equal amounts of purified CPS or CPSCRM derived from each selected Kp clinical isolate (Table 1) for a final concentration of 1 mg/mL in SMQ. Antigen cocktails were then shipped to Pacific Immunology Corporation (Ramona, CA) for generation of antibodies in rabbits (NIH Animal Welfare Assurance Number: A4182-01; USDA License Number: 93R-0283). In brief, preimmune sera were obtained from rabbits at the start of the immunization protocol. Rabbits were then immunized with cocktails containing CPS or CPSCRM derived from isolates 30684, 56203, 50219, 50220, and 56661 (rabbit group 1 and rabbit group 2) or isolates 53370, 56575, 53374, and 56661 (rabbit group 3 and rabbit group 4) and AdjuLite Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA). There were two rabbits per antigen group (eight rabbits in total). Rabbits were boosted with CPS or CPSCRM combined with Incomplete Freund’s Adjuvant (IFA) according to the immunization schedule provided in Fig. 1, and rabbit blood was collected on the days indicated in Fig. 1 for subsequent generation of serum. Serum was stored frozen at −80°C until use.

For experiments shown in Fig. 5, IgG was purified from rabbit antisera with protein G Sepharose (Protein G HP SpinTrap), according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA).

Determination of antibody titers by flow cytometry

Antibody titers were determined by flow cytometry as described previously (32). For strains shown in Table 1 and for 76 isolates selected from recent archived collections at CDI, which included >1,000 genomically characterized ESBL-producing clinical isolates from diverse geographic locations in the United States. Bacteria were cultured to mid-exponential phase of growth in LB medium, and 400 µL of each culture was pelleted by centrifugation at 4,300 × g for 4 min at RT. In some experiments, bacteria were cultured to late stationary phase of growth (overnight) in LB or HYEM medium (Fig. S1). Supernatant was discarded, and bacteria were washed in 1 mL DPBS and pelleted again. Bacteria were resuspended in 1 mL blocking buffer (2% bovine serum albumin [BSA] in DPBS) and kept on ice for 1 h. Samples were centrifuged again, and bacterial pellets were resuspended in 1 mL DPBS. A 100 µL aliquot of bacteria was added to microcentrifuge tubes containing 100 µL rabbit serum that had been pre-diluted appropriately (as indicated in figures and legends) in DPBS. Samples were incubated on ice for 30 min. Samples were then diluted with 800 µL wash buffer (0.8% BSA in DPBS), centrifuged again, and the supernatant was discarded. Pellets were resuspended in 100 µL DPBS containing a 1:500 dilution of goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Jackson, Bar Harbor, ME). Mixtures were chilled on ice for 30 min, diluted with 800 µL wash buffer, and centrifuged as described above to pellet cells. Pellets were resuspended in 200 µL wash buffer, transferred to FACS tubes, and analyzed on a FACSCelesta Flow Cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Estimated titers of rabbit immune serum were determined by comparison with rabbit preimmune serum (1:2,000 dilution) plus secondary detection antibody, which was used as the negative control for these experiments and had very low geometric mean fluorescence (GMF, range: 22–263). As reported previously, estimated titers were determined based on the highest dilution of immune sera that resulted in surface binding greater than that of the preimmune serum controls (32). For data shown in Fig. 4, a GMF of 3,500 was set at the conservative cut-off value (42nd percentile) for moderate/strong antisera cross-reactivity (Fig. S1B). This cut-off value was determined based on the GMF values of preimmune sera at 1:2,000 dilution (22–263) and the range of GMF for all samples used for Fig. 4 (23–111,109, median GMF for immune sera is 7144) (Fig. S1B).

Antibody typing with rabbit antisera was assessed by flow cytometry essentially as described above for determination of titers, except bacteria were incubated with a 1:2,000 dilution of rabbit antisera followed by detection with FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies specific for rabbit IgG, IgA, or IgM (Abcam, Boston, MA).

Preparation of human PMNs

Heparinized venous blood was obtained from healthy volunteers in accordance with a protocol (01-I-N055) approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects at the National Institutes of Health. All blood donors provided informed consent prior to participation in the study. Polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs or neutrophils) were isolated from heparinized venous blood with standard dextran sedimentation of erythrocytes and Hypaque-Ficoll gradient centrifugation (58). PMNs were suspended at 107 cells/mL in RPMI 1640 medium buffered with 1 mM Hepes, pH 7.2 (RPMI/H) and kept at ambient temp until used. Purity and viability of isolated neutrophils were determined by flow cytometry (BD FACSCelesta, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). PMN preparations (n = 11) were comprised of 98.9 ± 0.5% granulocytes (typically 95–98% neutrophils and 2–5% eosinophils) and viability was 99.4 ± 0.5% as assessed by propidium iodide uptake. Human serum was prepared from coagulated venous blood as described previously (51).

PMN bactericidal activity

PMN bactericidal activity assays were performed as described, but with a few modifications (51). In brief, 24-well polystyrene tissue culture plates were precoated with 20% normal human serum (NHS) at 37°C for 60 min, a step necessary to prevent PMN activation by polystyrene (59, 60). NHS was aspirated, and plates were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline. Bacteria (2.5 × 106 CFUs in 100 µL RPMI/H) were combined with 44 µg purified IgG (100 µg/mL final concentration in the assay) for 5 min at ambient temp. Purified IgG was tested in pilot studies at 10, 50, and 100 µg/mL final concentration, and 100 µg/mL was selected for these assays. We note that CPS-specific IgG in human sera is often at or above 100 µg/mL following administration of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (61, 62). The bacteria-IgG mixture was then combined with PMNs (5 × 105 in 100 µL RPMI/H; 5:1 bacteria PMN ratio) and autologous human serum (10% final concentration) in 24-well culture plates in a final vol of 444 µL. Plates were centrifuged at 450 × g for 6 min to synchronize phagocytosis, and then they were incubated at 37°C for 60 min. Saponin (0.1% final conc) was added to each assay well to terminate phagocytosis, and plates were chilled on ice for 15 min. An aliquot of each assay was diluted in saline, plated on LB agar, and percent survival was determined as described (51).

Statistical analyses

Bacterial survival data (in colony forming units, CFUs) were analyzed in Prism 10 for Windows 64-bit (GraphPad Prism, version 10.2.3). Shapiro-Wilk test and visualization by QQ plot were used to determine whether data were normally distributed. Data were analyzed using a repeated-measures ANOVA and Tukey’s posttest to correct for multiple comparisons. Data that failed the Shapiro-Wilk test were LogY transformed and analyzed using a repeated-measures ANOVA and Tukey’s posttest. Statistics for data shown in Fig. 5A through C were conducted on raw CFU data. The CFU data were in turn converted to percentages relative to the control samples containing bacteria and preimmune IgG (and 10% NHS, which was present in all assays).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Frank R. DeLeo, Email: fdeleo@niaid.nih.gov.

Daria Van Tyne, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be made fully available and without restriction, upon request.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.03338-24.

Influence of bacterial culture conditions and geometric mean fluorescence (Geo Mean FL or GMF) cut-off value for cross-reactivity.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ikuta KS, Swetschinski LR, Robles Aguilar G, Sharara F, Mestrovic T, Gray AP, Davis Weaver N, Wool EE, Han C, Gershberg Hayoon A, et al. , Collaborators GAR . 2022. Global mortality associated with 33 bacterial pathogens in 2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. The Lancet 400:2221–2248. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02185-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Verani JR, Blau DM, Gurley ES, Akelo V, Assefa N, Baillie V, Bassat Q, Berhane M, Bunn J, Cossa ACA, et al. 2024. Child deaths caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae in sub-Saharan Africa and south Asia: a secondary analysis of child health and mortality prevention surveillance (CHAMPS) data. Lancet Microbe 5:e131–e141. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(23)00290-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boceska BK, Vilken T, Xavier BB, Kostyanev T, Lin Q, Lammens C, Ellis S, O’Brien S, da Costa RMA, Cook A, et al. 2024. Assessment of three antibiotic combination regimens against gram-negative bacteria causing neonatal sepsis in low- and middle-income countries. Nat Commun 15:3947. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-48296-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kumar CK, Sands K, Walsh TR, O’Brien S, Sharland M, Lewnard JA, Hu H, Srikantiah P, Laxminarayan R. 2023. Global, regional, and national estimates of the impact of a maternal Klebsiella pneumoniae vaccine: a bayesian modeling analysis. PLoS Med 20:e1004239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1004239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Murray CJL, Ikuta KS, Sharara F, Swetschinski L, Robles Aguilar G, Gray A, Han C, Bisignano C, Rao P, Wool E, et al. 2022. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. The Lancet 399:629–655. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arias CA, Komarow L, Chen L, Hanson BM, Weston G, Cober E, Garner OB, Jacob JT, Satlin MJ, et al. , Multi-Drug Resistant Organism Network I . 2020. Molecular and clinical epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant enterobacterales in the USA (CRACKLE-2): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 20:731–741. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30755-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shropshire WC, Dinh AQ, Earley M, Komarow L, Panesso D, Rydell K, Gómez-Villegas SI, Miao H, Hill C, Chen L, Patel R, Fries BC, Abbo L, Cober E, Revolinski S, Luterbach CL, Chambers H, Fowler VG Jr, Bonomo RA, Shelburne SA, Kreiswirth BN, van Duin D, Hanson BM, Arias CA. 2022. Accessory genomes drive independent spread of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae clonal groups 258 and 307 in Houston, TX. MBio 13:e0049722. doi: 10.1128/mbio.00497-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pomakova DK, Hsiao CB, Beanan JM, Olson R, MacDonald U, Keynan Y, Russo TA. 2012. Clinical and phenotypic differences between classic and hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumonia: an emerging and under-recognized pathogenic variant. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 31:981–989. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1396-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Russo TA, Marr CM. 2019. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Clin Microbiol Rev 32:e00001–00019. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00001-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Catalán-Nájera JC, Garza-Ramos U, Barrios-Camacho H. 2017. Hypervirulence and hypermucoviscosity: two different but complementary Klebsiella spp. phenotypes? Virulence 8:1111–1123. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2017.1317412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee HC, Chuang YC, Yu WL, Lee NY, Chang CM, Ko NY, Wang LR, Ko WC. 2006. Clinical implications of hypermucoviscosity phenotype in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates: association with invasive syndrome in patients with community-acquired bacteraemia. J Intern Med 259:606–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01641.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Walker KA, Treat LP, Sepúlveda VE, Miller VL. 2020. The small protein RmpD drives hypermucoviscosity in Klebsiella pneumoniae. MBio 11:e01750-20. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01750-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Walker KA, Miner TA, Palacios M, Trzilova D, Frederick DR, Broberg CA, Sepúlveda VE, Quinn JD, Miller VL. 2019. A Klebsiella pneumoniae regulatory mutant has reduced capsule expression but retains hypermucoviscosity. MBio 10:e00089-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00089-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ovchinnikova OG, Treat LP, Teelucksingh T, Clarke BR, Miner TA, Whitfield C, Walker KA, Miller VL. 2023. Hypermucoviscosity regulator RmpD interacts with Wzc and controls capsular polysaccharide chain length. MBio 14:e0080023. doi: 10.1128/mbio.00800-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mike LA, Stark AJ, Forsyth VS, Vornhagen J, Smith SN, Bachman MA, Mobley HLT. 2021. A systematic analysis of hypermucoviscosity and capsule reveals distinct and overlapping genes that impact Klebsiella pneumoniae fitness. PLoS Pathog 17:e1009376. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cheng HY, Chen YS, Wu CY, Chang HY, Lai YC, Peng HL. 2010. RmpA regulation of capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis in Klebsiella pneumoniae CG43. J Bacteriol 192:3144–3158. doi: 10.1128/JB.00031-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yang X, Liu X, Chan E-C, Zhang R, Chen S. 2023. Functional characterization of plasmid-borne rmpADC homologues in Klebsiella pneumoniae . Microbiol Spectr 11:e0308122. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.03081-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yu F, Lv J, Niu S, Du H, Tang YW, Pitout JDD, Bonomo RA, Kreiswirth BN, Chen L. 2018. Multiplex PCR analysis for rapid detection of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenem-resistant (sequence type 258 [ST258] and ST11) and hypervirulent (ST23, ST65, ST86, and ST375) strains. J Clin Microbiol 56:e00731-18. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00731-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu YM, Li BB, Zhang YY, Zhang W, Shen H, Li H, Cao B. 2014. Clinical and molecular characteristics of emerging hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infections in mainland China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:5379–5385. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02523-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gu D, Dong N, Zheng Z, Lin D, Huang M, Wang L, Chan E-C, Shu L, Yu J, Zhang R, Chen S. 2018. A fatal outbreak of ST11 carbapenem-resistant hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Chinese hospital: a molecular epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis 18:37–46. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30489-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Choi M, Tennant SM, Simon R, Cross AS. 2019. Progress towards the development of Klebsiella vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines 18:681–691. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2019.1635460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cryz SJ, Mortimer PM, Mansfield V, Germanier R. 1986. Seroepidemiology of Klebsiella bacteremic isolates and implications for vaccine development. J Clin Microbiol 23:687–690. doi: 10.1128/jcm.23.4.687-690.1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cryz SJ, Mortimer P, Cross AS, Fürer E, Germanier R. 1986. Safety and immunogenicity of a polyvalent Klebsiella capsular polysaccharide vaccine in humans. Vaccine 4:15–20. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(86)90092-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Edelman R, Talor DN, Wasserman SS, McClain JB, Cross AS, Sadoff JC, Que JU, Cryz SJ. 1994. Phase 1 trial of a 24-valent Klebsiella capsular polysaccharide vaccine and an eight-valent Pseudomonas O-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine administered simultaneously. Vaccine 12:1288–1294. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(94)80054-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Campbell WN, Hendrix E, Cryz S, Cross AS. 1996. Immunogenicity of a 24-valent Klebsiella capsular polysaccharide vaccine and an eight-valent Pseudomonas O-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine administered to victims of acute trauma. Clin Infect Dis 23:179–181. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.1.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cryz SJ, Fürer E, Germanier R. 1985. Safety and immunogenicity of Klebsiella pneumoniae K1 capsular polysaccharide vaccine in humans. J Infect Dis 151:665–671. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.4.665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cryz SJ, Cross AS, Sadoff GC, Que JU. 1988. Human IgG and IgA subclass response following immunization with a polyvalent Klebsiella capsular polysaccharide vaccine. Eur J Immunol 18:2073–2075. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830181230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pennini ME, De Marco A, Pelletier M, Bonnell J, Cvitkovic R, Beltramello M, Cameroni E, Bianchi S, Zatta F, Zhao W, Xiao X, Camara MM, DiGiandomenico A, Semenova E, Lanzavecchia A, Warrener P, Suzich J, Wang Q, Corti D, Stover CK. 2017. Immune stealth-driven O2 serotype prevalence and potential for therapeutic antibodies against multidrug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Nat Commun 8:1991. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02223-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cohen TS, Pelletier M, Cheng L, Pennini ME, Bonnell J, Cvitkovic R, Chang CS, Xiao X, Cameroni E, Corti D, Semenova E, Warrener P, Sellman BR, Suzich J, Wang Q, Stover CK. 2017. Anti-LPS antibodies protect against Klebsiella pneumoniae by empowering neutrophil-mediated clearance without neutralizing TLR4. JCI Insight 2:e92774. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.92774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Diago-Navarro E, Calatayud-Baselga I, Sun D, Khairallah C, Mann I, Ulacia-Hernando A, Sheridan B, Shi M, Fries BC. 2017. Antibody-based immunotherapy to treat and prevent infection with hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Clin Vaccine Immunol 24:e00456-16. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00456-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Diago-Navarro E, Motley MP, Ruiz-Peréz G, Yu W, Austin J, Seco BMS, Xiao G, Chikhalya A, Seeberger PH, Fries BC. 2018. Novel, broadly reactive anticapsular antibodies against carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae protect from infection. MBio 9:e00091-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00091-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kobayashi SD, Porter AR, Freedman B, Pandey R, Chen L, Kreiswirth BN, DeLeo FR. 2018. Antibody-mediated killing of carbapenem-resistant ST258 Klebsiella pneumoniae by human neutrophils. MBio 9:e00297-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00297-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hegerle N, Choi M, Sinclair J, Amin MN, Ollivault-Shiflett M, Curtis B, Laufer RS, Shridhar S, Brammer J, Toapanta FR, Holder IA, Pasetti MF, Lees A, Tennant SM, Cross AS, Simon R. 2018. Development of a broad spectrum glycoconjugate vaccine to prevent wound and disseminated infections with Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS One 13:e0203143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Malachowa N, Kobayashi SD, Porter AR, Freedman B, Hanley PW, Lovaglio J, Saturday GA, Gardner DJ, Scott DP, Griffin A, Cordova K, Long D, Rosenke R, Sturdevant DE, Bruno D, Martens C, Kreiswirth BN, DeLeo FR. 2019. Vaccine protection against multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in a nonhuman primate model of severe lower respiratory tract infection. MBio 10:e02994-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02994-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Feldman MF, Mayer Bridwell AE, Scott NE, Vinogradov E, McKee SR, Chavez SM, Twentyman J, Stallings CL, Rosen DA, Harding CM. 2019. A promising bioconjugate vaccine against hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116:18655–18663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1907833116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cryz SJ, Fürer E, Germanier R. 1985. Purification and vaccine potential of Klebsiella capsular polysaccharides. Infect Immun 50:225–230. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.1.225-230.1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Domenico P, Diedrich DL, Cunha BA. 1989. Quantitative extraction and purification of exopolysaccharides from Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Microbiol Methods 9:211–219. doi: 10.1016/0167-7012(89)90038-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Domenico P, Schwartz S, Cunha BA. 1989. Reduction of capsular polysaccharide production in Klebsiella pneumoniae by sodium salicylate. Infect Immun 57:3778–3782. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.12.3778-3782.1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pollard AJ, Perrett KP, Beverley PC. 2009. Maintaining protection against invasive bacteria with protein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccines. Nat Rev Immunol 9:213–220. doi: 10.1038/nri2494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hickey JM, Toprani VM, Kaur K, Mishra RPN, Goel A, Oganesyan N, Lees A, Sitrin R, Joshi SB, Volkin DB. 2018. Analytical comparability assessments of 5 recombinant CRM197 proteins from different manufacturers and expression systems. J Pharm Sci 107:1806–1819. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2018.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bröker M, Costantino P, DeTora L, McIntosh ED, Rappuoli R. 2011. Biochemical and biological characteristics of cross-reacting material 197 CRM197, a non-toxic mutant of diphtheria toxin: use as a conjugation protein in vaccines and other potential clinical applications. Biologicals 39:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2011.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Avci FY, Kasper DL. 2010. How bacterial carbohydrates influence the adaptive immune system. Annu Rev Immunol 28:107–130. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sen G, Khan AQ, Chen Q, Snapper CM. 2005. In vivo humoral immune responses to isolated pneumococcal polysaccharides are dependent on the presence of associated TLR ligands. J Immunol 175:3084–3091. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Haudiquet M, Buffet A, Rendueles O, Rocha EPC. 2021. Interplay between the cell envelope and mobile genetic elements shapes gene flow in populations of the nosocomial pathogen Klebsiella pneumoniae. PLoS Biol 19:e3001276. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Geyer H, Himmelspach K, Kwiatkowski B, Schlecht S, Stirm S. 1983. Degradation of bacterial surface carbohydrates by virus-associated enzymes. Pure and Applied Chemistry 55:637–653. doi: 10.1351/pac198855040637 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dutton GG, Parolis H, Joseleau JP, Marais MF. 1986. The use of bacteriophage depolymerization in the structural investigation of the capsular polysaccharide from Klebsiella serotype K3. Carbohydr Res 149:411–423. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)90061-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lindberg B, Lindh F, Lönngren J, Sutherland IW. 1979. Structural studies of the capsular polysaccharide of Klebsiella type 30. Carbohydr Res 76:281–284. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(79)80031-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Merrifield EH, Stephen AM. 1979. Structural studies on the capsular polysaccharide from Klebsiella serotype K64. Carbohydr Res 74:241–257. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)84780-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Parolis H, Parolis LAS, Whittaker DV. 1992. Re-investigation of the structure of the capsular polysaccharide of Klebsiella K15 using bacteriophage degradation and inverse-detected NMR experiments. Carbohydr Res 231:93–103. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(92)84011-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pan YJ, Lin TL, Chen CT, Chen YY, Hsieh PF, Hsu CR, Wu MC, Wang JT. 2015. Genetic analysis of capsular polysaccharide synthesis gene clusters in 79 capsular types of Klebsiella spp. Sci Rep 5:15573. doi: 10.1038/srep15573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. DeLeo FR, Porter AR, Kobayashi SD, Freedman B, Hao M, Jiang J, Lin YT, Kreiswirth BN, Chen L. 2023. Interaction of multidrug-resistant hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae with components of human innate host defense. MBio 14:e0194923. doi: 10.1128/mbio.01949-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cryz SJ Jr, Fürer E, Germanier R. 1984. Prevention of fatal experimental burn-wound sepsis due to Klebsiella pneumoniae KP1-O by immunization with homologous capsular polysaccharide. J Infect Dis 150:817–822. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.6.817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cryz S J Jr, Fürer E, Germanier R. 1986. Immunization against fatal experimental Klebsiella pneumoniae pneumonia. Infect Immun 54:403–407. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.2.403-407.1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Trautmann M, Cryz SJ, Sadoff JC, Cross AS. 1988. A murine monoclonal antibody against Klebsiella capsular polysaccharide is opsonic in vitro and protects against experimental Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. Microb Pathog 5:177–187. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(88)90020-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jones RJ, Roe EA. 1984. Vaccination against 77 capsular types of Klebsiella aerogenes with polyvalent Klebsiella vaccines. J Med Microbiol 18:413–421. doi: 10.1099/00222615-18-3-413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Blumenkrantz N, Asboe-Hansen G. 1973. New method for quantitative determination of uronic acids. Anal Biochem 54:484–489. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(73)90377-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Filisetti-Cozzi TM, Carpita NC. 1991. Measurement of uronic acids without interference from neutral sugars. Anal Biochem 197:157–162. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90372-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kremserova S, Nauseef WM. 2020. Isolation of human neutrophils from venous blood. Methods Mol Biol 2087:33–42. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-0154-9_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Nathan CF. 1987. Neutrophil activation on biological surfaces. Massive secretion of hydrogen peroxide in response to products of macrophages and lymphocytes. J Clin Invest 80:1550–1560. doi: 10.1172/JCI113241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. DeLeo FR, Allen LA, Apicella M, Nauseef WM. 1999. NADPH oxidase activation and assembly during phagocytosis. J Immunol 163:6732–6740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Parker AR, Park MA, Harding S, Abraham RS. 2019. The total IgM, IgA and IgG antibody responses to pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination (Pneumovax(R)23) in a healthy adult population and patients diagnosed with primary immunodeficiencies. Vaccine 37:1350–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.01.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bucciol G, Schaballie H, Schrijvers R, Bosch B, Proesmans M, De Boeck K, Boon M, Vermeulen F, Lorent N, Dillaerts D, Kantsø B, Jørgensen CS, Emonds M-P, Bossuyt X, Moens L, Meyts I. 2020. Defining polysaccharide antibody deficiency: measurement of anti-pneumococcal antibodies and Anti-Salmonella typhi antibodies in a cohort of patients with recurrent infections. J Clin Immunol 40:105–113. doi: 10.1007/s10875-019-00691-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Influence of bacterial culture conditions and geometric mean fluorescence (Geo Mean FL or GMF) cut-off value for cross-reactivity.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made fully available and without restriction, upon request.