Abstract

Due to the limitations of traditional observational studies, investigating the association between inflammatory factors and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) remains challenging. In this study, we employed Mendelian randomization (MR) combined with meta-analysis to assess the causal relationship between 91 inflammatory factors and IBD. We selected genome-wide association study (GWAS) data for inflammatory factors and IBD from GWAS databases and conducted 2-sample MR analyses using the inverse-variance weighted (IVW) method, MR-Egger regression, and weighted median estimator. The MR analyses were performed for 91 inflammatory factors with IBD outcome data from 2 different databases. Subsequently, a meta-analysis of the main IVW results was conducted, followed by multiple corrections of the meta-analysis results. Conduct MR analysis between inflammatory factors and subtypes of IBD (Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis [UC]), followed by reverse causality validation of positive inflammatory factors with IBD and its subtype outcome data. In the IVW analysis of the 91 inflammatory factors with IBD outcome data from the GWAS catalog database, C-X-C motif chemokine 9 (CXCL9) was found to be positively associated with the risk of IBD (OR = 1.24, 95% CI = 1.09–1.41, P = .001). Similarly, in the IVW analysis with IBD outcome data from the IEU database, CXCL9 was also positively associated with the risk of IBD (OR = 1.76, 95% CI = 1.12–2.76, P = .015). Meta-analysis and multiple corrections showed a significant association between CXCL9 and IBD (OR = 1.27, 95% CI = 1.12–1.44, P = .001). In the MR analysis of IBD subtypes, the inflammatory factor CXCL9 showed a significant causal association with UC using the IVW method (OR = 1.77, 95% CI = 1.39–2.44, P = .0004), with a P-value of .038 after multiple testing correction. However, no significant causal association was observed between CXCL9 and Crohn disease = 3.28). In the reverse MR analysis, no causal effect of IBD and UC on CXCL9 was found. CXCL9 exhibits a causal relationship with IBD, functioning as a disease-progression risk factor that elevates UC risk, suggesting potential therapeutic targets for alleviating symptoms and slowing progression in UC patients.

Keywords: bidirectional Mendelian randomization analysis, inflammatory bowel disease, inflammatory factors, meta-analysis, multiple corrections

1. Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) represents a chronic and relapsing inflammatory disorder affecting the gastrointestinal tract, primarily comprising ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn disease (CD). It is characterized by persistent or episodic immune dysregulation that leads to intestinal inflammation. Clinically, individuals may experience abdominal discomfort, frequent loose stools, and hematochezia, alongside systemic features such as elevated body temperature, reduced hemoglobin levels, and extraintestinal manifestations including arthropathy, dermatologic and mucosal abnormalities, ocular involvement, hepatobiliary complications, and an increased risk of thrombotic episodes.[1,2] IBD is estimated to impact nearly 1 million individuals in the United States and about 2.5 million across Europe. Moreover, its prevalence has extended to regions including the Middle East, South America, and Asia, highlighting its emergence as a major concern in global public health.[3,4]

In recent years, growing evidence suggests that the development and exacerbation of IBD are closely linked to immune-mediated production of pro-inflammatory mediators. Imbalances in cytokines – such as interleukins (ILs), chemokines, and tumor necrosis factors – are thought to contribute to chronic and relapsing intestinal inflammation. Among them, ILs serve as pivotal signaling molecules across various inflammatory cascades, and have been extensively studied for their involvement in the onset, progression, and therapeutic targeting of IBD.[5,6] For example, a longitudinal observational study investigated mucosal cytokine profiles in 55 patients with UC, assessing 10 different interleukins during disease flare-ups. The findings highlighted IL-8 as the most reliable biomarker for predicting disease recurrence. In addition, clinical research has corroborated the involvement of numerous chemokines in IBD pathophysiology. In one study, Raja Fayad and colleagues quantified serum levels of various chemokines in a cohort comprising 42 individuals with CD and 10 healthy participants. Their analysis revealed markedly elevated concentrations of several chemokines – such as CCL25, CCL23, CXCL5, CXCL13, CXCL10, and CXCL11 – in patients with IBD relative to healthy controls.[7,8]

Chemokines such as CCL25, CCL23, CXCL5, CXCL13, CXCL10, and CXCL11 contribute to the pathogenesis of IBD through diverse molecular pathways and cell-specific actions, influencing both acute inflammatory responses and the transition to tissue fibrosis. CCL25, a gut-selective chemokine predominantly produced by intestinal epithelial cells under the control of retinoic acid signaling, mediates the recruitment of α4β7 + T lymphocytes via interaction with the CCR9 receptor. In the context of UC, dysregulated Th17 cell trafficking through this axis may compromise mucosal immune tolerance and facilitate epithelial barrier breakdown. Meanwhile, CCL23 interacts with CCR1 and CCR4 receptors to attract monocytes and Th2 cells and is implicated in eosinophil activation and IL-5 production, which may aggravate mucosal injury through disruption of the mucus layer and the development of crypt abscesses.[9]

Within the CXC chemokine family, CXCL5 functions as a potent neutrophil attractant, markedly elevated in response to epithelial and stromal injury during UC exacerbations. Its expression levels have been shown to parallel fecal calprotectin concentrations and correlate with endoscopic disease severity. CXCL10 and CXCL11, acting through the CXCR3 receptor, promote a Th1-type immune response and are particularly enriched in granulomatous lesions characteristic of CD. These chemokines are associated with interferon-γ–mediated macrophage activation and contribute to tissue remodeling. CXCL13, on the other hand, plays a more tissue-specific role by recruiting B lymphocytes and follicular helper T cells via CXCR5 signaling in areas of transmural inflammation. This recruitment facilitates the development of tertiary lymphoid structures, which not only support local autoantibody generation but may also impair immune regulation through PD-1/PD-L1 interactions, thereby promoting the progression of chronic intestinal fibrosis.[10,11]

From a translational perspective, chemokines such as CXCL5 and CXCL10 have been integrated into certain disease activity indices for IBD assessment. Meanwhile, elevated CXCL13 levels have been linked to resistance against anti-TNF therapies and an increased likelihood of postoperative relapse. The tissue-specific expression patterns of CCL25 – predominantly found in the small intestine – and CCL23 – preferentially upregulated in the colon – may serve as useful biomarkers to distinguish between IBD subtypes. Therapeutic strategies targeting these chemokine pathways are actively being developed. Although the CCR9 antagonist Vercirnon did not achieve its primary endpoints in several clinical trials, its ability to influence the Th17/Treg axis continues to attract scientific attention. Preliminary findings on CXCR3 blockade agents such as Vesencumab, as well as neutralizing antibodies against CXCL13 like MILRID, indicate the potential for dual modulation of Th1-driven and B cell–mediated immune responses.[12]

In the multifaceted pathogenesis of IBD, chemokines contribute to both inflammatory amplification and structural remodeling of intestinal tissue through dynamic, temporospatial interactions. During the acute inflammatory stage, CXCL5 and CXCL10 exhibit coordinated activity across distinct receptors. CXCL5 signals through CXCR2 to activate neutrophils, promoting the release of elastase and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which directly impair epithelial barrier function. Concurrently, CXCL10 facilitates the recruitment of monocytes that subsequently polarize into pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages, producing TNF-α and IL-1β. These cytokines, in turn, stimulate further CXCL5 expression by epithelial cells, establishing a self-reinforcing “neutrophil–monocyte” inflammatory loop. This chemokine synergy is particularly evident during UC exacerbations, and emerging clinical evidence indicates that concurrent inhibition of CXCR2 and CXCR3 may lead to marked reductions in endoscopic inflammation scores.[13]

In the chronic stage of disease, CD-associated transmural inflammation is predominantly shaped by the interplay between CXCL13 and CXCL10/CXCL11. CXCL13-induced clustering of B cells contributes not only to the production of antimicrobial antibodies and profibrotic mediators – such as IL-13 and TGF-β – but also enhances antigen presentation, thereby activating Th1 cells recruited via CXCL10 signaling.[14] These Th1 cells release interferon-γ (IFN-γ), which promotes fibroblast activation and collagen deposition, establishing a self-perpetuating loop of lymphoid tissue expansion and fibrosis. In parallel, the regulatory role of CCL25 is tightly modulated by the inflammatory milieu. Under homeostatic conditions, CCL25 supports Treg cell trafficking and suppresses immune overactivation. However, in the chronic inflammatory environment characteristic of IBD, upregulated CCL25 preferentially attracts CCR9 + Th17 cells. These cells secrete IL-17A, further inducing epithelial production of CXCL5 and IL-8, thereby collaborating with neutrophils to exacerbate crypt abscess formation and epithelial erosion. This Th17/Treg disequilibrium is particularly evident in individuals with genetic predispositions, such as those harboring ATG16L1 variants.[15–17]

The bifunctional receptor-binding capacity of CXCL11 (targeting both CXCR3 and CXCR7) adds an additional layer of complexity to chemokine-mediated synergy. Through CXCR3, CXCL11 amplifies Th1-driven immune responses, whereas engagement with CXCR7 promotes endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis, potentially enhancing immune cell infiltration. This aberrant neovascularization contributes to intestinal hypoxia and fibrotic remodeling, which may be instrumental in the development of fistulizing disease in Crohn pathology.

From a therapeutic standpoint, strategies involving multi-target modulation are drawing increasing interest. For instance, the combined use of CXCR3 antagonists with JAK inhibitors offers the potential to dampen Th1 activity and systemic cytokine surges concurrently. Similarly, co-targeting CXCL13 with neutralizing antibodies alongside anti-integrin agents like vedolizumab may disrupt both tertiary lymphoid organogenesis and lymphocyte trafficking. Nonetheless, the intrinsic redundancy and compensatory mechanisms within the chemokine signaling network present ongoing hurdles. Inhibition of CXCL10, for example, may result in compensatory upregulation of CXCL11, while CCL25 blockade could impair physiological gut immune surveillance. Moving forward, the integration of single-cell spatial transcriptomics holds promise for unraveling context-dependent cellular interactions, ultimately facilitating precision-guided immunomodulatory interventions.[17,18]

Although prior research has indicated potential associations between inflammatory mediators and the pathogenesis of IBD, current findings remain inconclusive and lack comprehensive validation. Many studies are limited by small sample sizes and methodological inconsistencies, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions regarding these relationships. Observational designs are particularly prone to biases such as residual confounding and reverse causality, and often fall short due to the absence of robust data from randomized controlled trials.

To overcome these limitations, Mendelian randomization (MR) offers a genetic approach that emulates randomized allocation, thereby minimizing confounding and improving causal inference. When integrated with meta-analytic techniques, MR becomes a powerful tool to assess the causal impact of specific exposures on disease outcomes. In this study, we applied a 2-sample MR framework combined with meta-analysis to evaluate the potential causal links between 91 inflammatory biomarkers and IBD. The findings aim to provide novel insights into disease mechanisms and inform future strategies for IBD prevention, diagnosis, and therapy.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This study examines the causal relationship between 91 inflammatory factors (as exposure variables) and IBD (as the outcome variable) using significant related single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as instrumental variables (IVs). We employed a 2-sample MR approach for causal analysis, conducted Cochran Q test to assess heterogeneity, and performed sensitivity analyses to verify the reliability of the results. Following MR analysis, we conducted a meta-analysis of the results, applying multiple corrections using the Bonferroni method. Moreover, MR analyses were performed separately between inflammatory factors and CD as well as UC. Finally, based on the definitive positive results, reverse causality validation was conducted for the positive inflammatory factors in relation to the outcome and its subtypes.

The MR analysis is based on the satisfaction of the following 3 core assumptions: IVs are closely related to the exposure; IVs are not associated with confounding factors that affect the exposure-outcome relationship; and IVs influence the outcome solely through the exposure, without affecting the outcome via other pathways.[19,20] It is worth mentioning that this study involves the processing and analysis of data from a public GWAS database; therefore, ethical review is no longer required.

In MR analysis, the inverse-variance weighted (IVW) method serves as the core approach, offering the highest statistical power and computational efficiency under the assumption that IVs have no horizontal pleiotropy. However, its results are susceptible to invalid IVs or heterogeneity, necessitating sensitivity tests (e.g., Cochran Q) to validate the assumption’s validity. MR-Egger regression tests for horizontal pleiotropy through the intercept term, relaxing the strict assumption that “all IVs are valid” (requiring only the instrument strength independent of direct effect, or InSIDE, assumption). However, the intercept test has low statistical power, and in the presence of directional pleiotropy, MR-Egger may still lead to bias.

The weighted median method has a higher tolerance for invalid IVs (allowing up to 50% of instruments to be invalid) and provides more robust estimates in scenarios with strong heterogeneity. However, its estimation precision is generally lower than IVW, and it requires the majority of IVs to be valid. The simple mode method estimates causal effects based on the mode principle, making it insensitive to outliers and computationally straightforward. However, it assumes that most IVs have effects concentrated around a single true value, which may fail if the IV effect distribution is widely dispersed. The weighted mode method builds on the simple mode approach by incorporating weights (e.g., IV precision), reducing the influence of outliers and improving reliability. However, its result stability depends on the appropriateness of the weights and is sensitive to weak IVs.

In MR studies, result determination is typically based on a joint assessment of IVW, MR-Egger, and the weighted median method. Specifically, if the P-value from the IVW method is <.05 and the beta estimates from IVW, MR-Egger, and the weighted median method are in the same direction, the result is considered significant. Otherwise, it is classified as a null result.

2.2. Data sources

The datasets included in this MR combined with meta-analysis study were obtained from publicly accessible aggregated genome-wide association study (GWAS) data. IBD data were sourced from 2 databases: the GWAS catalog database and the IEU database. The GWAS catalog database data (http://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/databases/gwas/summary_statistics/GCST004001-GCST005000/GCST004131/harmonised/28067908-GCST004131-EFO_0003767.h.tsv.gz) includes 9083 cases and 403,098 controls of European ancestry.[21] The IEU database data (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/files/ieu-a-294/ieu-a-294.vcf.gz) comprises 31,665 cases and 33,977 controls of European ancestry.[22] Data for inflammatory factors were obtained from a study involving 14,824 individuals of European ancestry, specifically from GWAS IDs GCST90274758 to GCST90274848.[23] The GWAS data for UC and CD were both sourced from the IEU OpenGWAS database. Specifically, the UC dataset (GWAS ID: ieu-a-970) included 13,768 cases and 33,977 controls, while the CD dataset (GWAS ID: ieu-a-12) comprised 17,897 cases and 33,977 controls.[22] Since all data were derived from publicly accessible studies, our research did not require patient consent or ethical approval.

2.3. Selection of instrumental variables

First, we set P < 1 × 10−5 as the genome-wide significance threshold to select SNPs closely associated with IBD and inflammatory factors. Next, we calculate the F-statistic for each exposure SNP using the formula F = (beta/s)² and exclude SNPs with an F-value <10 to ensure strong instrument validity.

Subsequently, we compute the minor allele frequency (MAF) based on the effect allele frequency (EAF). If the EAF is <0.5, it is assigned as the MAF; if the EAF is >0.5, the MAF is calculated as 1 – EAF. Only SNPs with an MAF >0.01 are retained to exclude rare variants.

Next, we perform MR instrument selection, incorporating linkage disequilibrium pruning to reduce redundancy and overfitting in the analysis. By setting clump_kb = 10,000 and clump_r2 = 0.001, we ensure that SNPs within a 10,000-kilobase (kb) window are considered independent if their pairwise r2 is <0.001, thereby minimizing the impact of highly linked SNPs on the results.[24,25]

Overall, the selection criteria for IVs in this study are as follows: P < 1 × 10−5, F > 10, MAF > 0.01, clump_kb = 10,000, and clump_r2 = 0.001. After applying these criteria to the GWAS data of 91 inflammatory factors, only 2095 SNPs met the final selection standards.[26]

3. Statistical analysis

This investigation utilized MR to examine the causal effects of 91 inflammatory biomarkers on IBD, leveraging summary-level outcome data from 2 independent genetic databases. MR analyses were conducted using the R package “TwoSampleMR,” incorporating multiple analytical methods including inverse-variance weighting (IVW), MR-Egger regression, and the weighted median approach. The IVW method served as the principal estimator for causal inference. To evaluate heterogeneity across IVs, Cochran Q statistic was computed for both IVW and MR-Egger outputs. The presence of horizontal pleiotropy was assessed using the MR-Egger intercept test, while the MR-PRESSO method was applied to detect potential outlier SNPs and correct for horizontal pleiotropic effects.[27,28]

To assess the robustness of our findings, we employed a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis, sequentially removing each individual SNP to determine its influence on the overall causal estimate. Results were deemed supportive of a causal relationship if the IVW method yielded statistically significant outcomes (P < .05), with no indication of horizontal pleiotropy or heterogeneity, and the direction of the β coefficient remained consistent across iterations. Under these conditions, the association was considered reliable, even if supplementary methods (e.g., MR-Egger or weighted median) did not reach statistical significance.[29] Meta-analysis was then performed on the primary IVW results, followed by reverse causal validation on the positive results with IBD outcome data. All analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.3.2).

4. Results

When selecting SNPs associated with each inflammatory factor and IBD, we set the genome-wide significance threshold at P < 1 × 10−5. The F-statistics for the SNPs of the 91 inflammatory factors ranged from 19.53 to 1180.18 (Table S1, Supplemental Digital Content, https://links.lww.com/MD/P275). All IVs had F-statistics >10, indicating no weak instrument bias. Sensitivity analysis results showed that MR-Egger regression indicated no horizontal pleiotropy (Table S2, Supplemental Digital content, https://links.lww.com/MD/P276), and Cochran Q test showed no heterogeneity among the IVs (Table S3, Supplemental Digital content, https://links.lww.com/MD/P277).

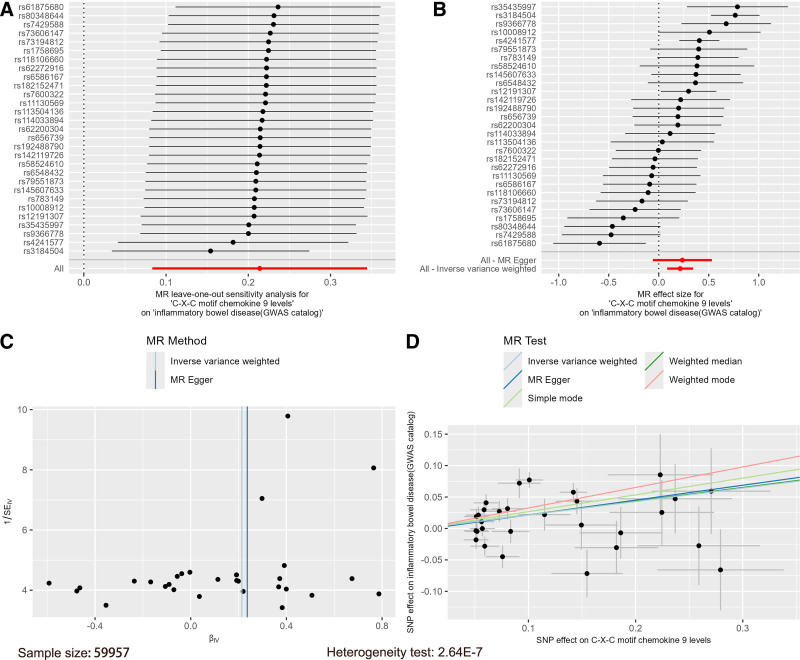

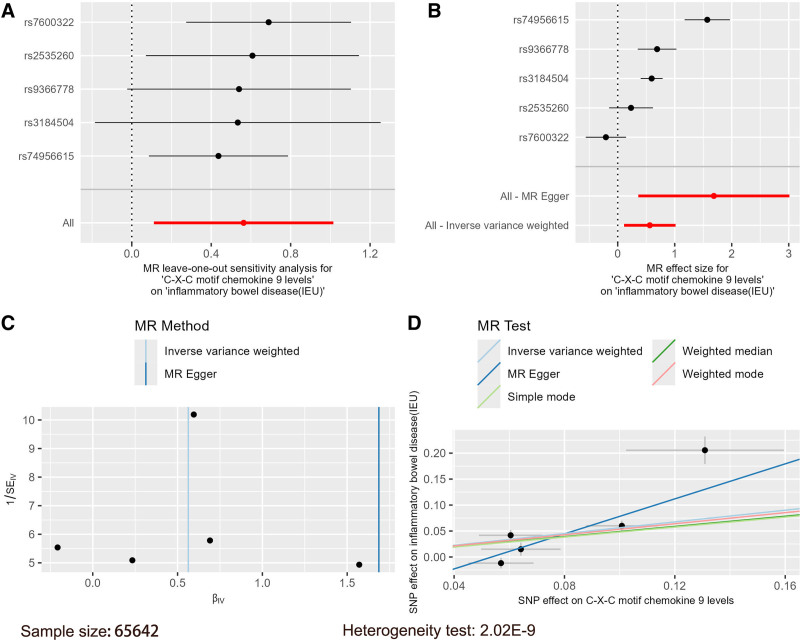

Using the 91 inflammatory factors as exposures, IBD data from the GWAS catalog database and the IEU database were used as outcomes in 2-sample MR analyses. IVW results indicated that with IBD from the GWAS catalog database as the outcome, CXCL9 was positively associated with IBD (OR = 1.24, 95% CI = 1.09–1.41, P = .001), and an MR combination chart was generated for this result (Fig. 1). Similarly, with IBD from the IEU database as the outcome, CXCL9 was also positively associated with IBD risk (OR = 1.76, 95% CI = 1.12–2.76, P = .015), increasing the risk of IBD, and an MR combination chart was also generated for this result (Fig. 2). The β values from MR-Egger and weighted median analyses were consistent in direction with the IVW results (Table S4, Supplemental Digital Content, https://links.lww.com/MD/P278).

Figure 1.

Mendelian randomization combination chart of C-X-C motif chemokine 9 on IBD (GWAS catalog). GWAS = genome-wide association study, IBD = inflammatory bowel disease.

Figure 2.

Mendelian randomization combination chart of C-X-C motif chemokine 9 on IBD (IEU).

Subsequently, we performed a meta-analysis of the IVW results from the MR analysis (Table S5, Supplemental Digital Content, https://links.lww.com/MD/P279), with multiple corrections applied. The meta-analysis and multiple corrections results showed a significant association between CXCL9 and IBD (OR = 1.27, 95% CI = 1.12–1.44, P = .001) (Table S6, Supplemental Digital Content, https://links.lww.com/MD/P280), and a forest plot was generated for the final meta-analysis and corrected results (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of C-X-C motif chemokine 9 after meta-analysis and multiple corrections.

IBD consists of 2 types: CD and UC. Based on the previous analysis results, we further conducted 2-sample MR analyses between 91 inflammatory factors and both CD and UC separately, applying multiple correction procedures. After multiple corrections, only the inflammatory factor CXCL9 showed a strong significant association with UC, with the beta estimates from the 3 main MR methods consistently pointing in the same direction.

Specifically, in the MR analysis of 91 inflammatory factors with CD, CXCL9 showed an IVW result of (OR = 1.79, 95% CI = 1.04–3.10, P = .036). However, after multiple correction adjustments, P increased to 3.28, indicating no significant causal association. In contrast, in the MR analysis of 91 inflammatory factors with UC, CXCL9 showed an IVW result of (OR = 1.77, 95% CI = 1.39–2.44, P = .0004), and after multiple correction adjustments, P = .038. Furthermore, the beta estimates from all 3 MR methods were consistent in direction, showing a positive correlation, indicating a significant causal association between CXCL9 and UC.

Overall, there is a significant association between the inflammatory factor CXCL9 and IBD. More specifically, CXCL9 is significantly associated with UC, while no clear causal relationship is observed between CXCL9 and CD (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mendelian randomization analysis results of inflammatory factors in CD and UC.

| Classification of IBD | OR (95% CI) | P | P adjust |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crohn disease | 1.79 (95% CI:1.04–3.10) | .036 | 3.28 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 1.77 (95% CI:1.39–2.44) | .0004 | .038 |

CD = Crohn disease, CI = confidence interval, IBD = inflammatory bowel disease, OR = odds ratio, UC = ulcerative colitis.

Using IBD data from the GWAS catalog database and the IEU database as exposures, and the inflammatory factor CXCL9 as the outcome, we conducted another 2-sample MR analysis. IVW results indicated that when IBD from the GWAS catalog database was used as the exposure, there was no causal relationship between IBD and CXCL9 (OR = 1.02, 95% CI = 0.99–1.03, P = .35). Similarly, when IBD from the IEU database was used as the exposure, there was no causal relationship between IBD and CXCL9 (OR = 1.03, 95% CI = 1.00–1.06, P = .06) (Table S7, Supplemental Digital Content, https://links.lww.com/MD/P281).

5. Discussion

To explore the potential causal link between inflammatory mediators and IBD, we performed a bidirectional MR analysis combined with meta-analysis, utilizing publicly accessible GWAS summary data. In the forward MR direction, we identified a significant positive association between CXCL9 levels and increased IBD risk. The meta-analysis further confirmed this relationship. Conversely, the reverse MR analysis revealed no evidence supporting a causal effect of IBD on circulating CXCL9 concentrations.

These results indicate a likely causal role of CXCL9 in the development and progression of IBD, positioning it as a pro-inflammatory factor contributing to disease exacerbation. CXCL9, a chemokine within the CXC family, is encoded on human chromosome 4 and comprises 103 amino acids. It is predominantly secreted by macrophages, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts in response to interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) stimulation. Functionally, CXCL9 interacts with the CXCR3 receptor to attract immune cells – including T lymphocytes, natural killer cells, and macrophages – to inflamed tissue sites, thereby intensifying local inflammation and inducing the production of additional inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, which collectively amplify the immune response.[30–33] Research by Seegert et al revealed that IL-16 is markedly upregulated in inflamed colonic tissues of individuals with IBD. This cytokine appears to contribute to disease pathogenesis by attracting and activating CD4+ T cells and stimulating the release of other key pro-inflammatory mediators. These observations support the notion that CXCL9 may exert comparable effects in IBD, potentially functioning in a parallel pathway that enhances mucosal immune cell recruitment and promotes sustained inflammation.[34]

In addition, CXCL9 may influence the intestinal microenvironment by modulating the composition and homeostasis of the gut microbiota, thereby fostering a pro-inflammatory milieu. Elevated levels of CXCL9 have also been implicated in promoting apoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells, which disrupts the mucosal barrier and further aggravates intestinal inflammation.[35] A previous study highlighted a therapeutic strategy targeting the CXCL9 pathway, reporting that the phytochemical curcumin can inhibit the CXCL9 inflammatory cascade.[36] A separate study integrating meta-analysis of serum proteomic data with forward MR based on protein quantitative trait loci (pQTL) further established a causal link between elevated CXCL9 concentrations and heightened risk of UC. Taken together, these findings highlight the pivotal role of CXCL9 in the pathophysiology of IBD and point toward its potential as a therapeutic target and biomarker for disease prevention and intervention strategies.[37,38]

Earlier research has demonstrated that chemokines such as CCL20, CXCL10, CXCL16, and CCL25 exhibit elevated expression in inflamed intestinal tissues relative to non-inflamed controls. Additionally, individuals with IBD present with significantly higher circulating or tissue levels of multiple chemokines – including CCL25, CCL23, CXCL5, CXCL13, CXCL10, CXCL11, and CCL21 – when compared to healthy individuals.[39–42] However, our analysis did not replicate these previously reported associations. Several factors may account for this discrepancy, including variation in the selection of inflammatory markers among different studies, the unique biological roles and expression dynamics of individual cytokines and chemokines, as well as population heterogeneity, which can influence cytokine profiles and impact the reproducibility of findings across cohorts.

In the context of IBD – especially UC – CXCL9 contributes to intestinal inflammation and disrupts the equilibrium between the epithelial barrier and gut microbiota through multiple interconnected mechanisms. It is produced by intestinal epithelial cells, macrophages, and activated T lymphocytes in response to stimuli such as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), or lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Upon binding to its receptor CXCR3, CXCL9 promotes the recruitment of Th1 cells, cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, and inflammatory monocytes into the intestinal mucosa. This leads to the establishment of a self-sustaining inflammatory loop, wherein infiltrating immune cells secrete IFN-γ, IL-12/23, and other pro-inflammatory cytokines. These mediators activate signaling cascades such as NF-κB and STAT1 in epithelial cells, inducing further chemokine production – including CXCL10 – and amplifying Th1/Th17-driven immune responses.[43–45]

This pro-inflammatory milieu directly undermines intestinal barrier integrity. Elevated levels of IFN-γ contribute to epithelial cell apoptosis through both Fas/FasL-dependent and mitochondrial-mediated apoptotic pathways. Simultaneously, IFN-γ inhibits the Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade, thereby impairing intestinal stem cell renewal and mucosal regeneration. Moreover, inflammatory cytokines stimulate the phosphorylation of myosin light chain kinase, resulting in the disruption of tight junction architecture by altering the expression and localization of proteins such as occludin and members of the claudin family – ultimately aggravating intestinal permeability, commonly referred to as “leaky gut.” The mucus barrier is also significantly compromised: IL-13–mediated activation of the STAT6 pathway suppresses goblet cell maturation and reduces MUC2 mucin secretion, while TNF-α and IFN-γ attenuate the production of key antimicrobial peptides – including α-defensins, lysozyme, and REG3γ – secreted by Paneth cells, thereby weakening the gut’s chemical defense mechanisms.[46–48]

Disruption of the intestinal barrier contributes to microbial dysbiosis. Enhanced epithelial permeability permits oxygen diffusion into the gut lumen, favoring the proliferation of facultative anaerobic pathogens such as adherent-invasive Escherichia coli. These bacteria utilize FimH adhesins to adhere to and invade epithelial cells, triggering NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Sulfate-reducing bacteria (e.g., Desulfovibrio species) produce hydrogen sulfide (H2S), which accumulates within mitochondria and exacerbates oxidative stress in epithelial cells.

At the same time, commensal microbiota are disrupted. Beneficial short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-producing Firmicutes, such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, are significantly depleted, leading to SCFA deficiency. This impairs anti-inflammatory signaling, particularly through reduced stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) and diminished histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition. Altered bile acid metabolism further aggravates inflammation through the accumulation of deoxycholic acid (DCA), which activates the pro-inflammatory farnesoid X receptor (FXR) pathway.

In parallel, microbial products such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and flagellin chronically activate intestinal macrophages via the TLR4/5–MyD88 signaling cascade, promoting IL-23/IL-17 axis activation and stimulating further CXCL9 production. Additionally, microbiota-derived tryptophan metabolites interfere with the Treg/Th17 equilibrium through the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), perpetuating a pathological feedback loop between mucosal inflammation and microbial imbalance.[49–51]

Therapeutically targeting the CXCL9/CXCR3 signaling axis represents a promising approach for IBD management. Pharmacologic blockade using CXCR3 antagonists such as AMG487 or monoclonal antibodies against CXCL9 (e.g., MEDI-565) has demonstrated efficacy in preclinical models, resulting in reduced immune cell infiltration, reestablishment of epithelial tight junction integrity, and increased abundance of beneficial microbiota such as Akkermansia muciniphila. Adjunctive strategies, including butyrate supplementation or fecal microbiota transplantation, may exert indirect inhibitory effects on CXCL9 expression by restoring SCFA concentrations and enhancing microbial diversity. Furthermore, epigenetic modulation using histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors or DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) inhibitors has shown potential to suppress CXCL9 transcription by silencing its promoter activity.[52,53]

Clinical evidence indicates that circulating CXCL9 levels are positively correlated with endoscopic disease severity in UC and may predict resistance to anti-TNF therapy, suggesting its potential utility as a stratification biomarker. Overall, CXCL9 appears to act as both an amplifier of inflammation and a disruptor of gut microbial balance in UC, positioning it as a pivotal target for interrupting the vicious cycle of barrier dysfunction, dysbiosis, and immune overactivation. These findings not only deepen our mechanistic understanding of CXCL9’s contribution to IBD pathogenesis – particularly in UC – but also provide a theoretical basis for novel clinical intervention strategies.

Despite the methodological strengths of this study compared to conventional observational approaches, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, potential sample selection bias may affect the external validity of our findings. The current analysis is based exclusively on GWAS data from individuals of European descent, which helps mitigate confounding due to population stratification but may limit the applicability of results to other ethnic groups. Genetic background, environmental exposures, and microbial composition can vary considerably across populations, potentially influencing immune signaling and host–microbiota interactions. For instance, immune pathways or microbiome-related mechanisms relevant to CXCL9 activity may differ in non-European cohorts. Therefore, replication of these findings in diverse populations, particularly in regions with distinct epidemiological patterns of IBD, is essential.

Second, the phenotypic granularity of available GWAS data remains limited. Current datasets lack detailed stratification based on clinically relevant variables such as disease activity (e.g., active vs quiescent), lesion localization, or sex. Given that the immune landscape and microbial ecology in IBD can vary substantially by disease stage or sex, this lack of resolution constrains the ability to fully characterize mechanistic heterogeneity. Future research should prioritize the inclusion of genetically diverse populations and integrate high-resolution clinical phenotyping with longitudinal multi-omics data. Such efforts will be crucial for elucidating CXCL9-mediated pathways in specific subgroups and advancing the development of precision medicine strategies for IBD.

6. Conclusion

This study, using bidirectional MR combined with meta-analysis, provides strong evidence for a causal relationship between elevated CXCL9 levels and increased risk of IBD, particularly UC. Mechanistically, CXCL9 promotes intestinal inflammation by recruiting CXCR3+ immune cells, activating Th1/Th17 signaling pathways, impairing mucosal barrier integrity through tight junction disruption and reduced mucin secretion, and facilitating microbial dysbiosis. These processes establish a self-sustaining cycle of inflammation and barrier damage. CXCL9’s early and disease-specific elevation also supports its potential role as a predictive biomarker for disease onset and progression.

Furthermore, emerging preclinical data suggest that targeting the CXCL9/CXCR3 axis – with monoclonal antibodies or small-molecule inhibitors – can reduce immune infiltration, enhance barrier repair, and restore microbial balance. Clinical translation of these findings may benefit from combination strategies, such as co-administering microbiota-directed therapies or epithelial-protective agents. Future research should validate these results in diverse populations and across different UC phenotypes and stages, ultimately contributing to precision medicine approaches that move beyond symptomatic control toward mechanistic, targeted intervention.

Acknowledgments

Firstly, we extend our deep gratitude to all individuals and researchers who contributed to the GWAS data for this study. Moreover, we sincerely thank and acknowledge the staff involved with the associated public databases. Finally, we express our heartfelt appreciation to every author who contributed to this research.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Xiang Ji, Afen Wu, Dehua Zha, Ming Li.

Data curation: Xiang Ji, Ming Li.

Formal analysis: Xiang Ji, Afen Wu, Dehua Zha, Ming Li.

Investigation: Xiang Ji, Afen Wu, Dehua Zha.

Methodology: Xiang Ji, Afen Wu, Dehua Zha, Ming Li.

Project administration: Xiang Ji, Afen Wu, Dehua Zha, Ming Li.

Software: Xiang Ji.

Supervision: Ming Li.

Validation: Xiang Ji, Afen Wu, Ming Li.

Visualization: Xiang Ji, Afen Wu, Dehua Zha.

Writing – original draft: Xiang Ji, Afen Wu, Dehua Zha.

Writing – review & editing: Ming Li.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations:

- CD

- Crohn disease

- CI

- confidence interval

- CXCL9

- C-X-C motif chemokine 9

- GWAS

- genome-wide association study

- IBD

- inflammatory bowel disease

- IFN-γ

- interferon-gamma

- IL

- interleukins

- IVs

- instrumental variables

- IVW

- inverse variance weighted

- MR

- Mendelian randomization

- OR

- odds ratio

- SNPs

- single nucleotide polymorphisms

- UC

- ulcerative colitis

- WME

- weighted median estimator

Our analysis used publicly available GWAS catalog database and IEU database. No new data were collected, and no new ethical approval was required.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article.

How to cite this article: Ji X, Wu A, Zha D, Li M. Causal relationship between inflammatory factors and inflammatory bowel disease: A bidirectional Mendelian randomization study combined with meta-analysis. Medicine 2025;104:26(e42988).

Contributor Information

Xiang Ji, Email: xiang10302024@163.com.

Afen Wu, Email: 18855137142@163.com.

Dehua Zha, Email: 1905127377@qq.com.

References

- [1].Zhang YZ, Li YY. Inflammatory bowel disease: pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:91–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hanauer SB. Inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and therapeutic opportunities. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:S3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2017;390:2769–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Understanding and preventing the global increase of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:313–21.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Neurath MF. Cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:329–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Neurath MF. Targeting immune cell circuits and trafficking in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:970–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kugathasan S, Saubermann LJ, Smith L, et al. Mucosal T-cell immunoregulation varies in early and late inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2007;56:1696–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hanzel J, Ma C, Casteele NV, Khanna R, Jairath V, Feagan BG. Vedolizumab and extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. Drugs. 2021;81:333–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Papadakis KA, Prehn J, Moreno ST, et al. CCR9-positive lymphocytes and thymus-expressed chemokine distinguish small bowel from colonic Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:246–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wurbel MA, McIntire MG, Dwyer P, Fiebiger E. CCL25/CCR9 interactions regulate large intestinal inflammation in a murine model of acute colitis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Duan ZL, Wang YJ, Lu ZH, et al. Wumei Wan attenuates angiogenesis and inflammation by modulating RAGE signaling pathway in IBD: network pharmacology analysis and experimental evidence. Phytomedicine. 2023;111:154658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Arabpour M, Saghazadeh A, Rezaei N. Anti-inflammatory and M2 macrophage polarization-promoting effect of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;97:107823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ding RL, Zheng Y, Bu J. Exploration of the biomarkers of comorbidity of psoriasis with inflammatory bowel disease and their association with immune infiltration. Skin Res Technol. 2023;29:e13536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Jerala M, Hauptman N, Kojc N, Zidar N. Expression of fibrosis-related genes in liver and kidney fibrosis in comparison to inflammatory bowel diseases. Cells. 2022;11:314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Nagata N, Takeuchi T, Masuoka H, et al. Human gut microbiota and its metabolites impact immune responses in COVID-19 and its complications. Gastroenterology. 2023;164:272–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zhang Y, Wang J, Sun H, et al. TWIST1+FAP+ fibroblasts in the pathogenesis of intestinal fibrosis in Crohn’s disease. J Clin Invest. 2024;134:e179472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Meng J, Li X, Xiong Y, Wu Y, Liu P, Gao S. The role of vitamin D in the prevention and treatment of tuberculosis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Infection. 2024;53:1129–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Singh UP, Venkataraman C, Singh R, Lillard JW, Jr. CXCR3 axis: role in inflammatory bowel disease and its therapeutic implication. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2007;7:111–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Xu W, Zhang T, Zhu Z, Yang Y. The association between immune cells and breast cancer: insights from Mendelian randomization and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2024;111:230–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Luo J, le Cessie S, van Heemst D, Noordam R. Diet-derived circulating antioxidants and risk of coronary heart disease: a Mendelian randomization study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].de Lange KM, Moutsianas L, Lee JC, et al. Genome-wide association study implicates immune activation of multiple integrin genes in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Genet. 2017;49:256–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Liu JZ, van Sommeren S, Huang H, et al. ; International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium. Association analyses identify 38 susceptibility loci for inflammatory bowel disease and highlight shared genetic risk across populations. Nat Genet. 2015;47:979–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zhao JH, Stacey D, Eriksson N, et al. ; Estonian Biobank Research Team. Genetics of circulating inflammatory proteins identifies drivers of immune-mediated disease risk and therapeutic targets. Nat Immunol. 2023;24:1540–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ellingjord-Dale M, Papadimitriou N, Katsoulis M, et al. Coffee consumption and risk of breast cancer: a Mendelian randomization study. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0236904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Luo S, Li W, Li Q, et al. Causal effects of gut microbiota on the risk of periodontitis: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13:1160993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Xu W, Zhang T, Zhu Z, Yang Y. The association between immune cells and breast cancer: insights from Mendelian randomization and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2025;111:230–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Burgess S, Thompson SG. Interpreting findings from Mendelian randomization using the MR-Egger method. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32:377–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Verbanck M, Chen CY, Neale B, Do R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat Genet. 2018;50:693–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Burgess S, Butterworth A, Thompson SG. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37:658–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Zhao Q, Kim T, Pang J, et al. A novel function of CXCL10 in mediating monocyte production of proinflammatory cytokines. J Leukoc Biol. 2017;102:1271–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Groom JR, Luster AD. CXCR3 in T cell function. Exp Cell Res. 2011;317:620–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Dufour JH, Dziejman M, Liu MT, Leung JH, Lane TE, Luster AD. IFN-gamma-inducible protein 10 (IP-10; CXCL10)-deficient mice reveal a role for IP-10 in effector T cell generation and trafficking. J Immunol. 2002;168:3195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cole KE, Strick CA, Paradis TJ, et al. Interferon-inducible T cell alpha chemoattractant (I-TAC): a novel non-ELR CXC chemokine with potent activity on activated T cells through selective high affinity binding to CXCR3. J Exp Med. 1998;187:2009–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Seegert D, Rosenstiel P, Pfahler H, Pfefferkorn P, Nikolaus S, Schreiber S. Increased expression of IL-16 in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2001;48:326–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Fang G, Kong F, Zhang H, Huang B, Zhang J, Zhang X. Association between inflammatory bowel disease and interleukins, chemokines: a two-sample bidirectional mendelian randomization study. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1168188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sadeghi M, Dehnavi S, Asadirad A, et al. Curcumin and chemokines: mechanism of action and therapeutic potential in inflammatory diseases. Inflammopharmacology. 2023;31:1069–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lin L, Yu H, Xue Y, Wang L, Zhu P. Proteome-wide mendelian randomization investigates potential associations in heart failure and its etiology: emphasis on PCSK9. BMC Med Genomics. 2024;17:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Cao J, Wan X, Su Q, Zhou Z. A commentary on “Bone grafting for femoral head necrosis in the past decade: a systematic review and network meta-analysis” (Int J Surg. 2023;10.1097. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000231). Int J Surg. 2024;110:569–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Konstantinidis AO, Adamama-Moraitou KK, Pardali D, et al. Colonic mucosal and cytobrush sample cytokine mRNA expression in canine inflammatory bowel disease and their correlation with disease activity, endoscopic and histopathologic score. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0245713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kulkarni N, Pathak M, Lal G. Role of chemokine receptors and intestinal epithelial cells in the mucosal inflammation and tolerance. J Leukoc Biol. 2017;101:377–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Reinecker HC, Steffen M, Witthoeft T, et al. Enhanced secretion of tumour necrosis factor-alpha, IL-6, and IL-1 beta by isolated lamina propria mononuclear cells from patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;94:174–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ye X, Liu S, Hu M, Song Y, Huang H, Zhong Y. CCR5 expression in inflammatory bowel disease and its correlation with inflammatory cells and β-arrestin2 expression. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:551–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Koper OM, Kamińska J, Sawicki K, Kemona H. CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11, and their receptor (CXCR3) in neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2018;27:849–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lim RJ, Salehi-Rad R, Tran LM, et al. CXCL9/10-engineered dendritic cells promote T cell activation and enhance immune checkpoint blockade for lung cancer. Cell Rep Med. 2024;5:101479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Wen T, Liu T, Chen H, Liu Q, Shen X, Hu Q. Demethylzeylasteral alleviates inflammation and colitis via dual suppression of NF-κB and STAT3/5 by targeting IKKα/β and JAK2. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;142(Pt B):113260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Luan X, Lei T, Fang J, et al. Blockade of C5a receptor unleashes tumor-associated macrophage antitumor response and enhances CXCL9-dependent CD8+ T cell activity. Mol Ther. 2024;32:469–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Marcovecchio PM, Thomas G, Salek-Ardakani S. CXCL9-expressing tumor-associated macrophages: new players in the fight against cancer. J ImmunoTher Cancer. 2021;9:e002045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Tokunaga R, Zhang W, Naseem M, et al. CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11/CXCR3 axis for immune activation – a target for novel cancer therapy. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;63:40–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Pan M, Wei X, Xiang X, Liu Y, Zhou Q, Yang W. Targeting CXCL9/10/11-CXCR3 axis: an important component of tumor-promoting and antitumor immunity. Clin Transl Oncol. 2023;25:2306–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Tan L, Li X, Qin H, et al. Identified S100A9 as a target for diagnosis and treatment of ulcerative colitis by bioinformatics analysis. Sci Rep. 2024;14:5517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Chen J, Zhou Y, Sun Y, et al. Bidirectional Mendelian randomisation analysis provides evidence for the causal involvement of dysregulation of CXCL9, CCL11 and CASP8 in the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:777–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Zamiri K, Kesari S, Paul K, et al. Therapy of autoimmune inflammation in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: dimethyl fumarate and H-151 downregulate inflammatory cytokines in the cGAS-STING pathway. FASEB J. 2023;37:e23068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Liu P, Meng J, Tang H, et al. Association between bariatric surgery and outcomes of total joint arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2025;111:1541–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.