Abstract

Seismic performance evaluation was conducted on eight circular reinforced concrete columns. Key design parameters for the columns included the number of longitudinal reinforcements, yield strength of reinforcements, vertical spacing of spirals, aspect ratio, and axial force ratio. Test results revealed that all columns exhibited stable as well as ductile response. Using the test results, drift ratios corresponding to various damage states, such as initial yielding, initial cover concrete spalling, initial core concrete crushing, buckling and fracture of longitudinal reinforcement, and the final spalled region were evaluated. The measured drift ratios were then compared with widely accepted drift ratios corresponding to damage limit states. Comparison revealed that the exiting damage limit states were notably conservative. This suggests that drift ratios for damage limit states need to be derived based on experimental observation of reinforced concrete columns designed by a national seismic design practice.

Keywords: Seismic design, Reinforced concrete column, Cyclic test, Damage limit state, Drift ratio

Subject terms: Natural hazards, Engineering

Introduction

Recently, an earthquake occurred on September 12, 2016 at the location of the 11.6 km away from Gyeongju city, South Korea. The earthquake recorded magnitude of 5.8 which has been the largest in the history of South Korea after since earthquake measurement was made1,2 After 14 months later, another earthquake took place at the location of 9 km away from Pohang city, South Korea. The magnitude of the Pohang earthquake was 5.4 which was the second largest in South Korea3. Unlike Gyeongju earthquake, structural damages were observed in the Pohang earthquake. These recent earthquakes imply that South Korea is not safe enough against earthquakes. Subsequently, seismic performance evaluation needs to be made for reinforced concrete members seismically designed by current Korean design practice. Earthquake engineering has been developed by conducting both field investigation of the structural damage and failure patterns due to earthquakes and various analytical evaluation regarding the failure causes. Both field and analytical investigate about the source of structural failure during and after earthquakes significantly improved seismic design methods ensuring the seismic performance of structures. Seismic design of reinforced concrete bridge columns has also been developed through detailed investigation on the damaged members4–6 and then the seismic design equations for the reinforced concrete columns were originated from previous experimental results.

In South Korea, the current seismic design practice for RC columns adopts a ductility demand-based approach. In this method, the amount of lateral confining reinforcement is determined according to the ductility required to withstand seismic loads. The procedure begins by designing the column for factored loads, followed by the placement of longitudinal reinforcement. Subsequently, the response modification factor is calculated using the ratio of the column’s nominal moment strength to its elastic seismic moment. The required ductility is then estimated based on the structure’s natural period, and adequate confining reinforcement is provided to ensure the column can achieve the intended ductility level.

Despite these provisions, existing design equations in South Korea are limited in their ability to predict performance levels under design loads7,8. In addition, engineering judgement criteria are required when slight or medium level of damage occurs under an earthquake event. Since these criteria can be an effective indicator for the remaining seismic performance of damaged members, they may provide useful information for repair and retrofitting of the members. This is further supported by previous studies on the seismic performance evaluation of reinforced concrete columns considering prior damage effects9–12.

Recent studies have highlighted that the seismic behavior of reinforced concrete (RC) columns is highly influenced by key parameters such as axial load level, concrete compressive strength, and member size. Saatcioglu et al.13 reported that constant axial compression reduces ductility and accelerates strength and stiffness degradation, while variable axial loads—alternating between tension and compression—induce distinct responses. Axial tension lowers flexural yield strength but delays degradation, whereas axial compression increases yield strength yet leads to faster deterioration. Z. Li et al.14 demonstrated experimentally that large high-strength RC columns experience reduced flexural strength, ductility, and energy dissipation under lateral loads due to significant size effects, consistent with Bažant’s size effect theory, underlining the importance of accounting for member size in seismic design. Additionally, J. Su et al.15 investigated the influence of reinforcement grade and concrete strength on the seismic performance of RC bridge piers, finding that higher concrete strength improves lateral capacity but reduces ductility due to smaller yield deformation, while high-strength reinforcement increases strength but can diminish energy dissipation and ductility under cyclic loading.

In light of these observations, the present study aims to experimentally evaluate the seismic performance of RC columns designed in accordance with current Korean seismic design practices. To this end, repeated lateral cyclic loading tests were conducted to observe and quantify damage state, energy dissipation, and stiffness degradation in relation to the key influencing parameters. The findings are intended to support the development of rational performance evaluation criteria and inform future revisions of seismic design guidelines for RC structures in moderate seismicity regions such as South Korea.

Column specimen and test setup

Column specimens

A total of eight reinforced concrete column specimens were designed and manufactured to evaluate seismic performance and damage limit state. These columns are satisfying the seismic design regulations of Concrete Bridge Design: Limit State Design Method16, which is used for everyday design practice in South Korea. Column section is circular with two levels of longitudinal reinforcement configurations, i.e., 20-D16 and 10-D22 resulting in 1.4% of identical reinforcement ratio. Spiral reinforcements are employed for lateral confinement with relatively dense vertical spacing of 40 mm, 55 mm and 95 mm in the expected plastic hinge regions. For other regions of the columns, 150 mm of vertical spacing is adopted for the lateral confinement reinforcement. An identical yield strength is employed for both longitudinal and transverse reinforcement. Dimension of the column section is set as 600 mm, approximately one-third scale of a typical actual bridge column in South Korea. Average compressive strength of three concrete cylinders measured at the day of column test was 26 MPa. Table 1 summarizes primary variable and material properties of the column specimens.

Table 1.

Material properties of column specimens.

| Specimen | Compressive strength of concrete  (MPa) (MPa) |

Longitudinal reinforcement | Transverse reinforcement | Aspect ratio |

Axial force ratio

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

s |  |

|

||||

| (%) | (MPa) | (mm) | (%) | (MPa) | ||||

| UNIT1 | 26 |

1.4 (20-D16) |

400 | 55/150 | 0.93 | 400 | 4 | 0.1 |

| UNIT2 | 55/150 | 0.93 | 4 | 0.15 | ||||

| UNIT3 | 55/150 | 0.93 | 3 | 0.1 | ||||

| UNIT4 | 55/150 | 0.93 | 6 | |||||

| UNIT5 | 40/150 | 1.27 | 4 | |||||

| UNIT6 | 96/150 | 0.53 | 4 | |||||

| UNIT7 | 1.4 (10-D22) | 400 | 55/150 | 0.93 | 400 | 4 | ||

| UNIT8 | 1.4 (20-D16) | 500 | 55/150 | 0.93 | 500 | 4 | ||

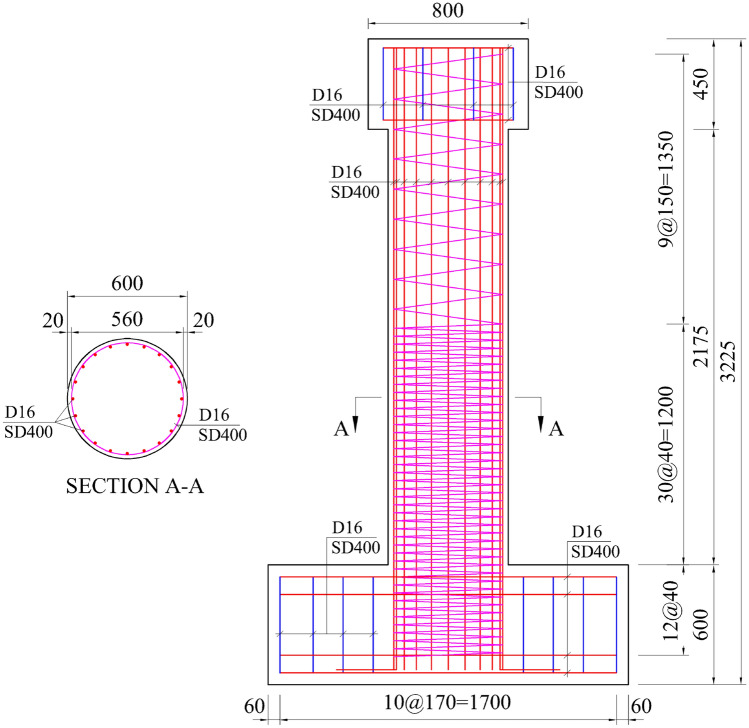

As shown in Table 1, longitudinal reinforcement ratio was set as identical in all specimens. However, three levels of vertical spacing for transverse reinforcement were employed to investigate the effect of the spacing on the column behavior. As a representative case, general layout and design details of UNIT5 column specimen are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Design details of UNIT5 column specimen (all units in mm).

Test setup

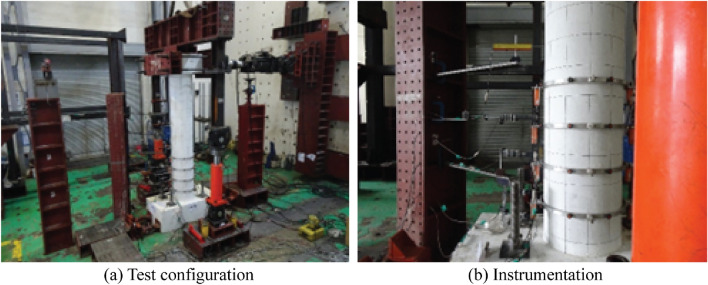

The column specimens were configured as cantilevers, with the base rigidly fixed and the top end free. Two levels of constant axial load ratios—10% and 15%—were applied at the top of the specimens using a 2,000 kN capacity hydraulic jack. To apply cyclic lateral loading, a 2,000 kN actuator with a ±250 mm stroke was installed on a reaction wall. Axial loads were delivered through two hydraulic jacks integrated into a loading frame, ensuring direct load transfer to the top of the specimens. Strain gauges were installed in the bottom region of outer-most longitudinal reinforcement in each loading direction, where plastic hinges are expected to occur. Moreover, a total of 16 LVDTs (linear Variable Displacement Transducer) were also installed to measure both lateral and vertical displacement at different heights of the column specimens. Additional LVDT was installed at the base of the column specimens to control a possible sliding. Fig. 2 shows test setup and instrumentation of the specimen UNIT4.

Fig. 2.

Representative test configuration and instrumentation.

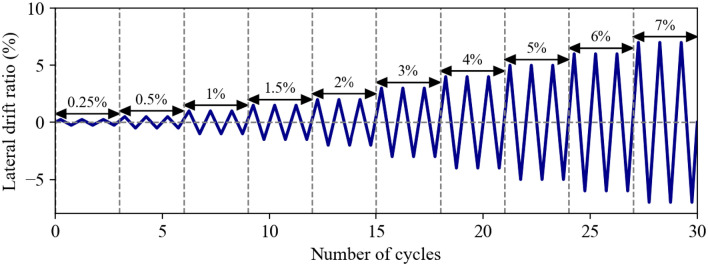

Lateral load was applied by increasing drift ratio in terms of using displacement control. Lateral load reversals consisted of three cycles at each drift ratio of ±0.25%, ±0.5%, ±1.0%. ±1.5%, ±2.0%, ±3.0%, and so on. While lateral drift ratios of relatively small increment were employed in elastic range, they were increased by 1.0% after reaching 2% of drift ratio. The graphical representation of lateral loading history is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Lateral drift ratio history.

Experimental results

Damage states

In general, similar damage behavior was observed in all column specimens. Once initial cracks formed, those cracks were propagated as drift ratio increased. Then, yielding of longitudinal reinforcement occurred as the number of cracks increased, leading to concrete cover spalling. Subsequently, fracture of longitudinal reinforcements occurred, and test was terminated. No failure was observed prior to the fracture of longitudinal reinforcements in all specimens. However, drift ratio corresponding to the fracture varied slightly in column specimens. Notably, UNIT6—with the widest vertical spacing of transverse reinforcement—experienced the earliest fracture at a drift ratio of 5%. Drift ratio and lateral displacement corresponding to the fracture are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Drift ratio and lateral displacement corresponding to the fracture.

| Specimen | Drift ratio at fracture (%) | Lateral displacement (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| UNIT1 | 6 | 144 |

| UNIT2 | 6 | 144 |

| UNIT3 | 6 | 108 |

| UNIT4 | 6 | 216 |

| UNIT5 | 6 | 144 |

| UNIT6 | 5 | 120 |

| UNIT7 | 7 | 168 |

| UNIT8 | 7 | 168 |

As observed in UNIT7, the use of larger-diameter reinforcement delayed reinforcement fracture to a higher drift level (7%) compared to UNIT1 (6%). When the total steel area is constant, using fewer, larger reinforcements reduces susceptibility to local buckling and low-cycle fatigue, both key mechanisms of reinforcement fracture in plastic hinge regions. Similarly, in UNIT8, the use of higher-yield-strength steel also delayed fracture to a 7% drift level. Higher yield strength postpones the onset of yielding and plastic strain accumulation, thereby extending the fatigue life of the reinforcement. It also allows the steel to sustain greater load before yielding, resulting in slower damage progression under cyclic loading. The enhanced lateral capacity observed further suggests that the post-yield strength of the reinforcement contributed to resisting additional drift without failure.These findings advocate a transition from conventional strength-based design to a performance-based approach that prioritizes inelastic behavior and fracture resistance in RC columns under seismic loading. By incorporating factors such as reinforcement size, reinforcement yield strength, and drift capacity, designers can enhance energy dissipation, delay reinforcement fracture, and ensure stable performance in plastic hinge regions. This comprehensive strategy promotes greater structural resilience and durability in earthquake-prone areas.

Crack pattern and initial yield

The progression of flexural cracking in the tested column specimens followed a typical pattern observed in reinforced concrete members subjected to lateral cyclic loading. After the formation of initial horizontal flexural cracks near the base of the columns during the first loading cycle, these cracks propagated further in subsequent cycles, with the development of additional new cracks. As the drift ratio increased, the spacing between these new cracks gradually decreased, indicating a more distributed cracking pattern. This behavior is consistent with the classical flexural cracking mechanism, where increased curvature leads to tighter crack spacing.

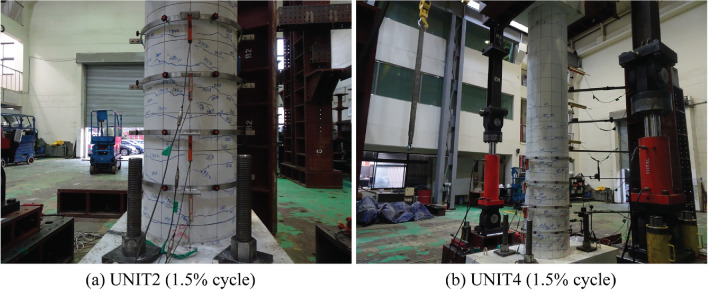

Interestingly, the formation of new cracks during the second and third cycles at the same drift ratio was limited, suggesting a stabilization of the crack pattern at a given drift level once the tensile strain demand was redistributed across the existing cracks. A notable influence of aspect ratio was observed in the crack evolution process. Specifically, specimens with lower aspect ratios exhibited denser horizontal crack spacing, implying a more localized curvature and strain demand at the base, which facilitates the development of multiple cracks in a confined zone. Fig. 4 shows representative crack patterns of specimens, UNIT2 and UNIT4 at the drift ratio of 1.5% (36 mm) before initial cover concrete spalled.

Fig. 4.

Representative crack patterns.

An increase in aspect ratio leads to a higher initial yielding displacement and a reduction in lateral force capacity. This trend is evident when comparing UNIT3, UNIT7, and UNIT4, which have aspect ratios of 3, 4, and 6, respectively. Their corresponding initial yield displacements were 11 mm, 14 mm, and 26 mm, while the peak lateral forces decreased from 236 kN to 173 kN and 124 kN. Increasing the aspect ratio of reinforced concrete columns leads to a shift from shear-dominant to flexure-dominant behavior (from shorter column to slender column), resulting in higher initial yield displacements and reduced lateral force capacity. As columns become more slender, their lateral stiffness decreases, requiring greater displacement to reach yielding. At the same time, the contribution of shear resistance diminishes, and the columns rely more heavily on flexural deformation to resist lateral loads. This combination of reduced stiffness, increased curvature demand, and lower shear contribution explains the observed increase in yielding displacement and decrease in lateral strength with higher aspect ratios.

Since the first yielding occurs at outer-most longitudinal reinforcements in both loading directions for a circular section, initial yielding was determined by the measured value of strain gauge installed at outer-most longitudinal reinforcements in the bottom of column specimens. In addition, rotation corresponding to the initial yielding was also calculated at the bottom regions of the column specimens using horizontal and vertical displacements measure by LVDTs. Table 3 summarizes initial yield displacements, lateral force and rotations corresponding to initial yielding. As observed, initial yield displacement was affected only by aspect ratio.

Table 3.

Yield displacement, lateral force and rotation corresponding to the initial yielding.

| Specimen | Yield displacement (mm) | Lateral force (kN) | Rotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| UNIT1 | 13 | 155 | 0.0042 |

| UNIT2 | 12 | 173 | 0.0035 |

| UNIT3 | 11 | 236 | 0.0054 |

| UNIT4 | 26 | 124 | 0.0041 |

| UNIT5 | 13 | 168 | 0.0045 |

| UNIT6 | 13 | 153 | 0.0044 |

| UNIT7 | 14 | 174 | 0.0049 |

| UNIT8 | 18 | 214 | 0.0056 |

Cover concrete spalling and crushing of confined concrete

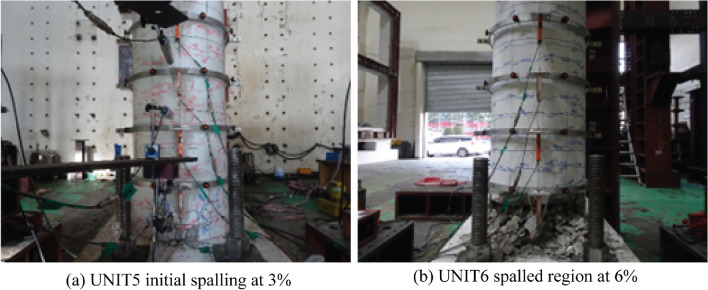

Cover concrete spalling of a column is one of important parameters for the evaluation of stiffness change and seismic performance. This is due to the fact that spalling is gradually developed along the height of column specimens in the plastic hinge region and leads to a crushing of confined concrete. Accordingly, presence and height of spalling can be a salient measure for determining repair and retrofitting of concrete members. The displacement at the time of initial spalling was visually investigated at each cycle of load steps. In addition, heights of initial cover concrete spalling were also measured along the column length. Cover spalling of unconfined concrete was progressively developed in the plastic hinge regions as the drift ratio increased, leading to crushing of confined concrete. The crushing of confined concrete may lead to an erroneous estimation of displacement measured by LVDT. Thus, applied drift ratio was evaluated when the initial crushing of confined concrete occurred. Table 4 summarizes the drift ratio and height of initial cover concrete spalling, drift ratio corresponding to initial crushing of confined concrete and buckling of longitudinal reinforcement, and final spalled region. Representative initial spalling and final spalled region for UNIT5 and UNIT6, respectively are shown in Fig. 5.

Table 4.

Lateral drift ratio by damage state.

| Specimen | Initial spalling | Initial core crushing | Buckling of reinforcement | Spalled height (mm) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drift ratio | Height | Drift ratio | Drift ratio | ||

| (%) | (mm) | (%) | (%) | ||

| UNIT1 | 2 | 100 | 5 ( cycle) cycle) |

5 ( cycle) cycle) |

300 |

| UNIT2 | 2 | 110 | 5 ( cycle) cycle) |

5 ( cycle) cycle) |

310 |

| UNIT3 | 2 | 100 | 5 ( cycle) cycle) |

6 ( cycle) cycle) |

250 |

| UNIT4 | 3 | 130 | 6 ( cycle) cycle) |

6 ( cycle) cycle) |

400 |

| UNIT5 | 3 | 110 | 6 ( cycle) cycle) |

6 ( cycle) cycle) |

200 |

| UNIT6 | 2 | 110 | 4 ( cycle) cycle) |

4 ( cycle) cycle) |

380 |

| UNIT7 | 3 | 150 | 6 ( cycle) cycle) |

6 ( cycle) cycle) |

310 |

| UNIT8 | 3 | 90 | 6 ( cycle) cycle) |

6 ( cycle) cycle) |

300 |

Fig. 5.

Representative initial spalling and final spalled region.

The onset of cover spalling occurred at drift ratios of 2% for UNIT6 and UNIT1, and was delayed to 3% for UNIT5, indicating that reducing vertical spiral spacing to a certain threshold can postpone cover spalling. Spalled heights was reduced significantly when reducing vertical spiral spacing. Core crushing occurred at drift ratios of 4%, 5%, and 6% in UNIT6, UNIT1, and UNIT5, respectively, demonstrating that the impact on delaying core crushing was even more pronounced. Tighter spiral spacing significantly contributed to improving resistance against early core degradation. Using higher yield strength (UNIT 8 vs. UNIT1) or larger diameter (UNIT7 vs. UNIT1) of longitudinal reinforcements also delayed initial spalling and core crushing. However, increasing the yield strength of longitudinal reinforcements seemed to have no impact on spalled height, while increasing the diameter of longitudinal reinforcements slightly increased spalled height. Furthermore, increasing the aspect ratio (comparing UNIT3, 7, and 4) tended to raise the drift levels at which initial spalling and core crushing occurred, but also resulted in greater spalled heights.

Based on this observation, the results suggest that current confinement strategies—typically based on minimum transverse reinforcement limits—may not be sufficient to delay critical damage such as cover spalling and core crushing under seismic loading. While code-prescribed spacing may satisfy strength and ductility requirements, the experimental evidence shows that tighter spiral spacing notably improves damage resistance, especially under large cyclic drifts. This indicates that existing provisions may underestimate the benefits of closely spaced reinforcement in enhancing post-yield performance. Revising confinement guidelines to include more performance-based criteria, particularly in plastic hinge regions, could improve seismic resilience and deformation capacity in reinforced concrete columns.

The drift ratios associated with each damage state, as presented in Table 4, can be regarded as rational criteria for predicting damage levels in the probabilistic seismic performance evaluation of reinforced concrete (RC) columns. The experimental methodology of categorizing damage states based on drift ratios merits careful consideration. This is because structural damage is typically assessed by examining the performance of individual components—such as columns, beams, and other load-bearing elements—each of which exhibits unique damage characteristics. As such, experimental observation of column behavior is essential for accurately identifying damage states linked to mechanisms such as cracking, spalling, yielding, buckling, and reinforcement fracture. This level of detail is critical, given that the field of earthquake engineering has been shaped by thorough observation and documentation of physical damage phenomena.

However, acquiring reliable experimental data—particularly local strains and rotations within the plastic hinge regions of RC columns—poses significant challenges. In light of these difficulties, drift ratio has emerged as a more practical and intuitive metric for classifying damage states. It offers a simplified yet meaningful representation of structural deformation and has thus become a widely accepted parameter in seismic performance assessments. This practicality underlies the use of drift ratio as the primary basis for damage state classification in the present column tests.

Accordingly, the onset of concrete spalling, core crushing, and reinforcement buckling were categorized as indicative of slight, moderate, and extensive damage limit states, respectively. These classifications are intuitive and align with observed damage progression. However, in the absence of standardized damage limit state definitions in South Korea, they should be regarded as exploratory classifications intended to guide further development of performance-based seismic evaluation criteria.

For evaluation purpose, drift ratios summarized in Table 4 were compared with those proposed by HAZUS17 and Dutta and Mander18. Table 5 shows comparison of drift ratio at each damage limit state. It is noteworthy that although classification of damage limit state is different in between HAZUS17 and Dutta and Mander18, proposed drift ratio at each damage limit state is identical. As observed, the present evaluation exhibited notably less conservative in comparison with those by HAZUS17 and Dutta and Mander18.

Table 5.

Comparison of drift ratios by damage limit states.

The experimentally derived drift ratios indicate that the damage thresholds proposed by both HAZUS and Dutta and Mander are conservative. The drift limits in HAZUS were developed primarily for purposes of seismic risk assessment and loss estimation, and thus adopt conservative assumptions to accommodate uncertainties and ensure broad applicability across various structural systems. In contrast, Dutta and Mander’s drift limits were based on a combination of experimental data and analytical models for specific structural types, particularly bridge columns designed according to U.S. seismic codes. These design standards are typically more conservative than those currently adopted in Korea. As a result, the drift ratios obtained in this study are less conservative than those suggested in prior literature, emphasizing the influence of national design practices and regulatory frameworks on damage limit definitions.

As for slight damage limit state, drift ratio suggested by the present test results exhibited a difference more than twice despite of the damage limit state corresponding to initial spalling. A similar difference was observed in the case of moderate damage limit state. This can be attributed to different provisions of seismic design details among different countries. The drift ratio of a column can be influenced by various variables such as specifications, material properties, cross-section dimension, yield strength and ratio of reinforcement, aspect ratio and so on. When seismic design details for these variables differ from countries, the drift ratio corresponding to damage limit state may also be different. Therefore, it is deemed necessary to conduct a study on the drift ratios for damage limit states based on experimental results of reinforced concrete columns designed in accordance with seismic design details of a country.

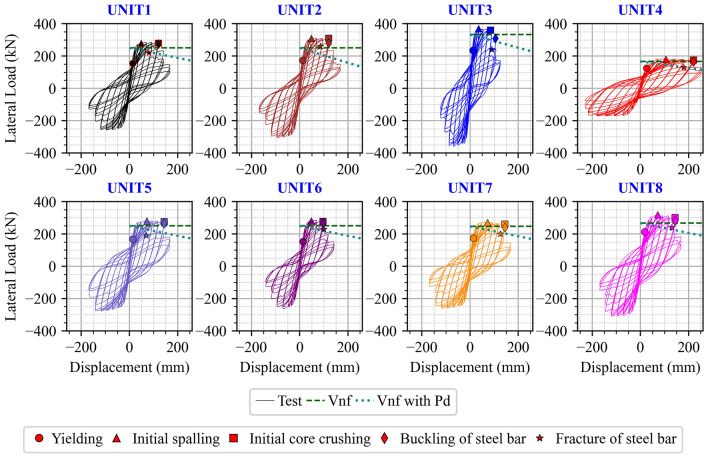

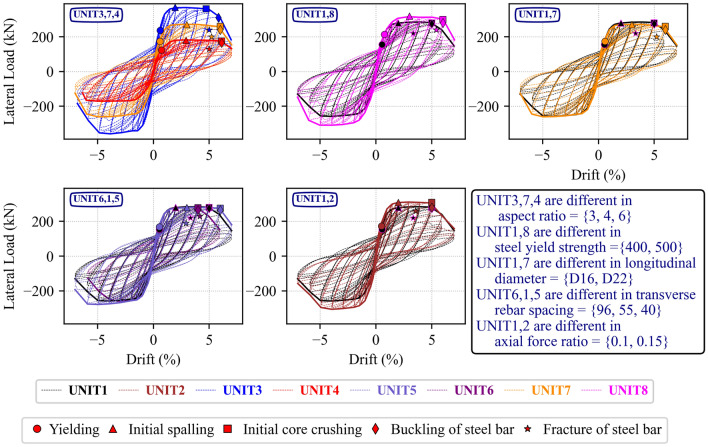

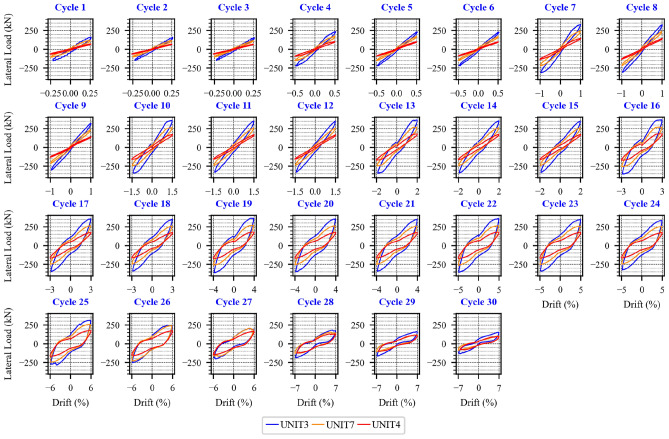

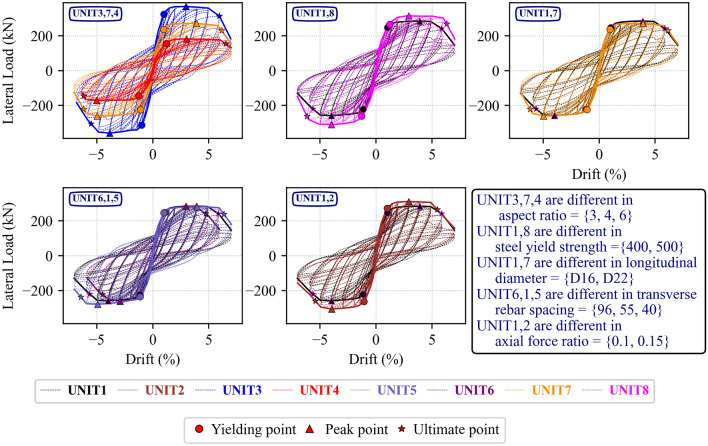

Lateral force-displacement hysteretic response

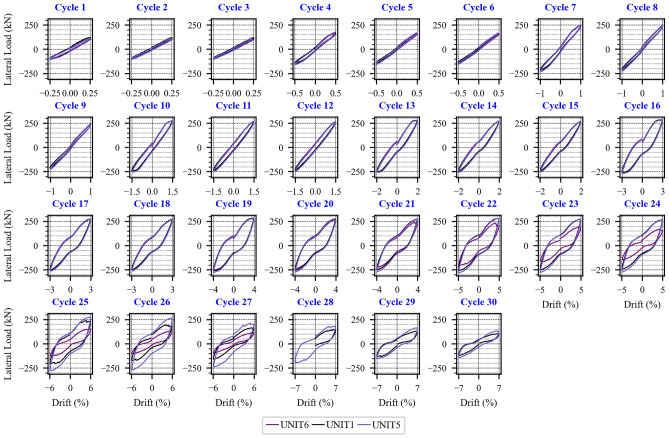

The lateral force–displacement hysteretic responses of the column specimens are presented individually and comparatively in Fig. 6 and 7. Points marked in the response indicate the onset of each damage state, i.e., initial yielding of longitudinal reinforcement, initial cover concrete spalling, crushing of confined concrete, buckling and fracture of longitudinal reinforcement, as described in the figure legend. In addition, while dashed line represent lateral force corresponding to theoretical moment strength, dotted line indicates the lateral force considering second moment effect of P- . As observed, all columns experienced no strength reduction with increasing displacement until the fracture of longitudinal reinforcement, and thus showed stable hysteretic response. As shown in the response of specimens of UNIT1, UNIT5 and UNIT6, the most stable response was observed in UNIT5 employing the smallest vertical spacing of transverse reinforcement. The hysteretic loops over every loading cycle of specimen UNIT6, 1, 5 were plotted as Fig. 8. As can be seen from the figure, before drift level of 4%, the loops of three specimens are completely identical. There is a slight difference among them when the drift level reaches to 4%, and the difference becomes significant between UNIT 6 and the others when drift level reaches 5%, the drift at steel fracture in UNIT6 (cycle 22). Compared to UNIT1 and 5, the maximum lateral load reduces significantly, the loop of UNIT 6 at this drift level is rotated to be more horizontal and the pinching effect becomes pronounced from this drift level. When the drift level reaches 6%, the steel of UNIT1 fractures in the first cycle (cycle 25) and that of UNIT5 fractures in the third cycle (cycle 27). This indicates that tighter vertical spacing of transverse reinforcements extends the inelastic deformation range prior to longitudinal reinforcements fracture.

. As observed, all columns experienced no strength reduction with increasing displacement until the fracture of longitudinal reinforcement, and thus showed stable hysteretic response. As shown in the response of specimens of UNIT1, UNIT5 and UNIT6, the most stable response was observed in UNIT5 employing the smallest vertical spacing of transverse reinforcement. The hysteretic loops over every loading cycle of specimen UNIT6, 1, 5 were plotted as Fig. 8. As can be seen from the figure, before drift level of 4%, the loops of three specimens are completely identical. There is a slight difference among them when the drift level reaches to 4%, and the difference becomes significant between UNIT 6 and the others when drift level reaches 5%, the drift at steel fracture in UNIT6 (cycle 22). Compared to UNIT1 and 5, the maximum lateral load reduces significantly, the loop of UNIT 6 at this drift level is rotated to be more horizontal and the pinching effect becomes pronounced from this drift level. When the drift level reaches 6%, the steel of UNIT1 fractures in the first cycle (cycle 25) and that of UNIT5 fractures in the third cycle (cycle 27). This indicates that tighter vertical spacing of transverse reinforcements extends the inelastic deformation range prior to longitudinal reinforcements fracture.

Fig. 6.

Lateral force-displacement hysteretic response.

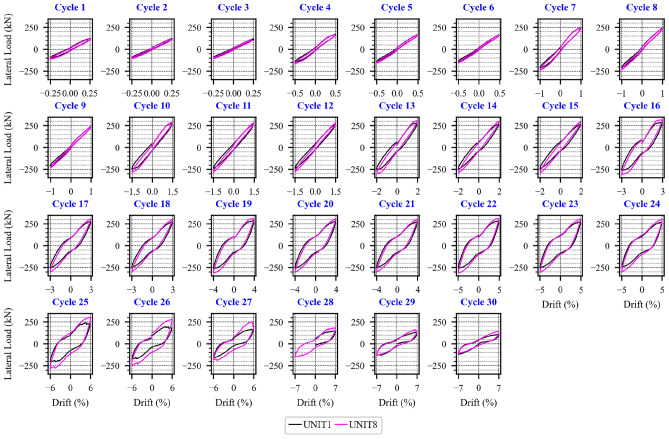

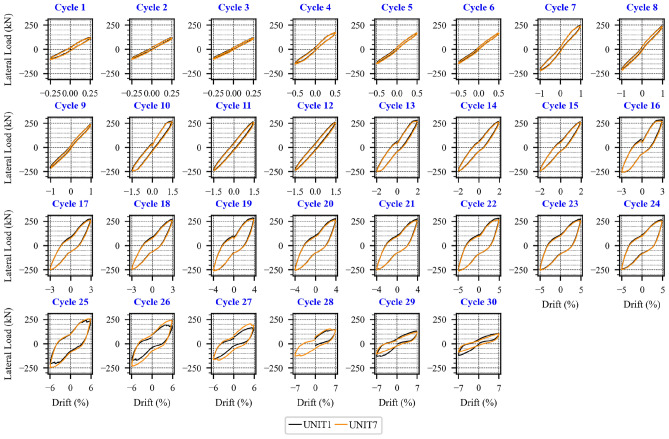

Fig. 7.

Hysteretic loops of all specimens, plotted in groups for comparison.

Fig. 8.

Hysteretic loops over every cycle of lateral loading of specimens UNIT1, 2.

Specimen UNIT7 exhibited a similar overall response to UNIT1, as both had the same longitudinal reinforcement ratio, though UNIT7 used fewer bars with larger diameters. However, reinforcement fracture in UNIT7 occurred later than in UNIT1, suggesting that larger-diameter bars are more effective in delaying fracture. Meanwhile, comparison between the hysteretic responses of UNIT1 and UNIT8 showed differences only in the peak lateral force, indicating that the yield strength of the longitudinal reinforcement had minimal impact on the overall hysteretic behavior. For a detailed representation, refer to the hysteretic loops for each loading cycle shown in Figs. 13, 14, 15 in the Appendix.

Fig. 13.

Hysteretic loops over every cycle of lateral loading of specimens UNIT3, 7, 4.

Fig. 14.

Hysteretic loops over every cycle of lateral loading of specimens UNIT1, 8.

Fig. 15.

Hysteretic loops over every cycle of lateral loading of specimens UNIT1, 7.

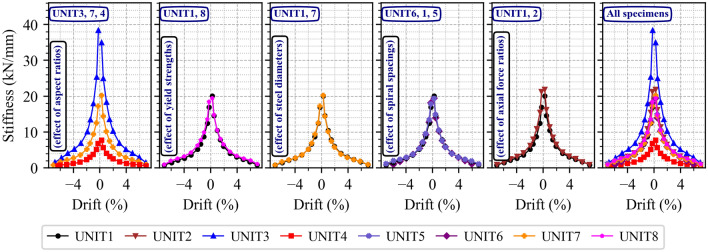

Stiffness degradation and energy dissipation capacity

Figure 9 illustrates the stiffness degradation behavior of all specimens over the examined drift ratio range. The degradation curves display symmetrical patterns in both the push and pull directions of lateral loading, attributed to the constant axial compression applied during testing. Specimens with greater aspect ratios (UNIT3, UNIT7, UNIT4) exhibited lower secant stiffness, indicating increased flexibility. In contrast, specimens subjected to higher axial compression (UNIT1 vs. UNIT8) or reinforced with higher yield strength steel (UNIT1 vs. UNIT8) showed enhanced stiffness, reflecting improved confinement and load resistance. Variations in longitudinal reinforcement diameter and transverse reinforcement spacing had minimal influence on stiffness degradation.

Fig. 9.

Secant stiffnesses of all specimens.

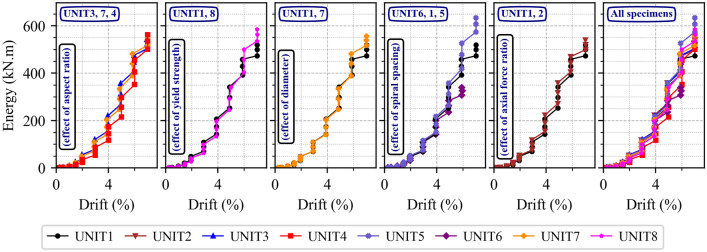

Figure 10 shows the evolution of accumulated dissipated energy over lateral loading cycles. The accumulated dissipated energy was calculated as the summation of areas of hysteretic loops from the beginning to the considered loading cycle. At a particular cycle of lateral load, the specimen with higher aspect ratios had smaller accumulated dissipated energy. Specimens under higher axial compression levels exhibit higher accumulated dissipated energy. Other parameters including yield strength, diameter of longitudinal reinforcement and vertical spacing of transverse reinforcement almost have a minimal influence on energy dissipation prior to the fracture of longitudinal longitudinal reinforcements.

Fig. 10.

Accumulated dissipated energy of all specimens.

Maximum lateral strength

The theoretical strength calculated using the equivalent rectangular stress block based on Concrete Bridge Design: Limit State Design Method16 were compared with the maximum lateral forces obtained experimentally in both push and pull directions for each column. Theoretical strength and the maximum lateral forces were summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Comparison of theoretical and experimental strength.

| Specimen | Theoretical strength | Experimental results | Error (%)  100 100 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moment capacity  (kN·m) |

Lateral force corresponding to   (kN) (kN) |

Push | Pull | Average | ||

| Maximum lateral force  (kN) (kN) |

Maximum lateral force  (kN) (kN) |

Maximum lateral force  (kN) (kN) |

||||

| UNIT1 | 599 | 250 | 284 | 254 | 269 | 7.6 |

| UNIT2 | 599 | 250 | 311 | 306 | 309 | 23.6 |

| UNIT3 | 599 | 333 | 367 | 356 | 362 | 8.7 |

| UNIT4 | 599 | 166 | 181 | 170 | 176 | 6.0 |

| UNIT5 | 599 | 250 | 281 | 274 | 278 | 11.2 |

| UNIT6 | 599 | 250 | 285 | 262 | 274 | 9.6 |

| UNIT7 | 592 | 247 | 271 | 261 | 266 | 7.7 |

| UNIT8 | 641 | 267 | 314 | 309 | 312 | 16.9 |

As presented in Table 6, the experimentally measured maximum lateral forces exceeded the theoretical strengths for all column specimens. This discrepancy is primarily attributed to nonlinear mechanisms that are not fully captured in conventional P–M interaction analyses based on simplified strain compatibility and force equilibrium. Specifically, factors such as concrete confinement, steel strain hardening, and compression strut action contribute to enhanced strength under cyclic lateral loading. While theoretical models often assume unconfined or idealized confined concrete, transverse reinforcement in real specimens improves confinement effectiveness—particularly in plastic hinge zones—resulting in increased compressive strength and ductility. Furthermore, strain hardening of longitudinal reinforcement, typically unaccounted for in elastic–perfectly plastic assumptions, contributes to increased flexural capacity. Additional effects such as localized cracking, stress redistribution, tension stiffening, and hysteretic energy dissipation under cyclic loading further raise lateral resistance beyond static predictions.

The relative increase in experimental lateral strength was more pronounced in specimens with higher axial force ratios and reinforcement yield strength. For instance, specimen UNIT2 (15% axial load ratio) exhibited a maximum lateral force approximately 15% greater than that of UNIT1 (10% axial load), indicating that increased axial compression enhances the safety margin relative to theoretical predictions. This improvement arises from several interrelated nonlinear effects: greater axial compression increases confinement through lateral restraint (Poisson effect), enhances flexural capacity by shifting the neutral axis and amplifying internal force couples, delays tensile cracking, reduces crack widths, and improves stiffness and damage resistance. These beneficial mechanisms are often underestimated or neglected in theoretical models, which tend to adopt conservative assumptions regarding degradation, bar slip, and post-yield behavior.

Finally, the maximum lateral force recorded for UNIT7, which had half the number of longitudinal reinforcement bars compared to UNIT1, was nearly identical to that of UNIT1. This suggests that, under the same design strength and detailing, the number of longitudinal bars had a negligible influence on the overall lateral strength within the tested range.

Displacement ductility

Definition of yield and ultimate displacement

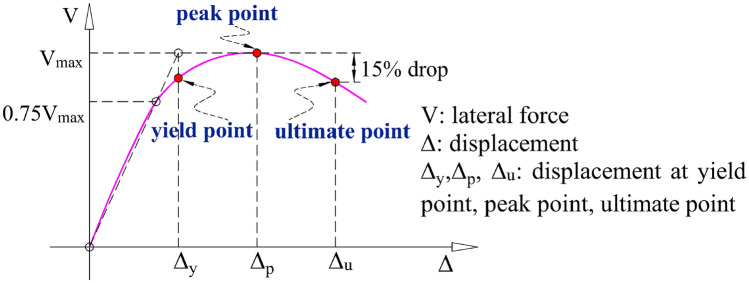

While reinforced concrete columns are in general required to retain sufficient strength to perform their functionality as structural members, they also need to have enough ductility to prevent collapse. Ductility is the ability of a structural member to undergo inelastic deformation without a rapid reduction in lateral load-carrying capacity. Thus, it is primarily quantified by the displacement ductility, expressed as the ratio of ultimate displacement to yield displacement. To assess the ductile capacity of column specimens, displacement ductility was calculated from experimental results. To obtain the displacement ductility, definitions for determining yield and ultimate displacements are needed, which can be derived from the envelope curves. Yield displacement was determined by both initial yielding of reinforcement and the procedure suggested by Ang et al.19. For the ultimate displacement, the displacement corresponding to a 15% reduction in the maximum lateral force on the envelope curve was defined as the ultimate displacement. Figure 11 schematically illustrates the procedure for determining yield and ultimate displacements, and the identified points are marked on the envelope curves in Figure 12.

Fig. 11.

Definition of yield and ultimate displacement.

Fig. 12.

Yield and ultimate displacement specified on lateral force-displacement envelope curves.

For the purpose of comparison, theoretical displacement ductility was calculated in terms of using ductility-based seismic design approach provided by Concrete Bridge Design: Limit State Design Method16. Detailed procedure for calculating the theoretical displacement ductility can be found in KIBSE16.

Comparison of displacement ductility

Table 7 summarized yield and ultimate displacement, and corresponding ductility. Yield displacements obtained from the force-displacement envelope curves exhibited slight difference between push and pull directions, which is not uncommon in the test. To account for the observed difference, average yield displacements in both push and pull directions were used.

Table 7.

Comparison of displacement ductility.

| Specimen | Experimental results | Ductility calculated by KIBSE16 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield displacement (mm) |

Ultimate displacement (mm) |

Displacement ductility |

||||

|

|

|

=

|

=

|

||

| UNIT1 | 13 | 26.9 | 137 | 10.5 | 5.1 | 3.5 |

| UNIT2 | 12 | 26.5 | 132 | 11.0 | 5.0 | 3.1 |

| UNIT3 | 11 | 16.0 | 106 | 9.6 | 6.6 | 3.7 |

| UNIT4 | 26 | 41.6 | 233 | 8.9 | 5.6 | 3.3 |

| UNIT5 | 13 | 22.4 | 152 | 11.7 | 6.8 | 4.5 |

| UNIT6 | 13 | 23.8 | 107 | 8.2 | 4.5 | 2.4 |

| UNIT7 | 14 | 25.9 | 147 | 10.5 | 5.7 | 3.5 |

| UNIT8 | 18 | 29.9 | 153 | 8.5 | 5.1 | 3.0 |

As shown in Fig. 12, displacement ductility was most pronounced in UNIT5 employing a relatively smaller vertical spacing of transverse reinforcement, while it was the least in UNIT6 with larger vertical spacing. This trend is consistent with the findings reported by Mounir Ait Belkacem et al.20. Displacement ductility obtained from experimental results exceeded significantly the ductility evaluated in accordance with the procedure by KIBSE16 in all column specimens. In particular, specimen UNIT6 exhibited 87% of extra safety margin. This indicates that reinforced concrete columns designed by the seismic design provisions of Concrete Bridge Design: Limit State Design Method16 ensure sufficient displacement ductility capacity.

Conclusions

This study conducted repeated cyclic loading test on a total of eight reinforced concrete columns satisfying the current seismic design provisions in South Korea. The findings derived from the experimental results are summarized as follows. Until the fracture of longitudinal reinforcement, all column specimens exhibited a stable and ductile response without a significant reduction in strength with increasing inelastic displacement. The displacement ductility obtained from experimental results demonstrated sufficient ductility capacity in comparison with that calculated in accordance with procedure by KIBSE16.

Initial cover concrete spalling occurred at drift ratio of 2% or 3% in the specimens. Delayed spalling was observed for specimens with the smallest vertical spacing of 40 mm, aspect ratio of 6, a larger diameter and higher yield strength of longitudinal reinforcement. As for initial crushing of confined concrete, early crushing was observed at 4% of drift ratio in the specimen with a relatively larger vertical spacing of 96 mm. However, delayed crushing at 6% of drift ratio was monitored in the specimens with a smaller vertical spacing of 40 mm, aspect ratio of 6 and higher yield strength of reinforcement.

Based on the experimental results, the drift ratios corresponding to each damage limit state were compared with those widely used drift ratios. Comparison revealed that those widely used drift ratios at each damage limit state were considerably conservative, particularly for slight and moderate damage limit states. This can be attributed to the differences in seismic design details and provisions across different countries. It is therefore deemed necessary that drift ratios for damage limit states need to be derived based on experimental observation of reinforced concrete columns designed by a national seismic design practice.

To improve the practical application of these findings, it is recommended that:

The current seismic performance evaluation guidelines in Korean codes should be revised to reflect more realistic, evidence-based drift limits, particularly for serviceability and reparability limit states.

Seismic detailing requirements should be adjusted toto enhance confinement and ductility without excessive conservatism.

National code provisions should incorporate performance-based drift limits that are experimentally verified and differentiated according to structural characteristics such as aspect ratio, reinforcement grade, and transverse reinforcement configuration.

To improve the robustness of evaluation criteria, future testing programs should incorporate higher levels of axial compression and variable axial load conditions to more accurately reflect real-world seismic demands. In addition, further research could explore the application of machine learning (ML) as a promising tool for advancing seismic assessment. By utilizing large datasets from experiments, simulations, and instrumented structures, ML models—such as neural networks, support vector machines, and ensemble methods—can effectively predict structural responses, classify damage states, and assess vulnerabilit. Integrated with sensing technologies, ML enables fast and accurate real-time evaluations, improving the overall efficiency of seismic performance assessment.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT: Ministry of Science and ICT) (No. NRF-2021R1 A2 C1011617 and RS-2024-00399324).

Appendix

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lee, D. H. & Jeon, J. S. Seismic performance assessment of a mid-rise RC building subjected to 2016 Gyeongju earthquake. J. Earthquake Eng. Soc. Korea20(7), 473–483 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee, D. H., Shim, J. Y. & Jeon, J. S. Damage potential of a domestic metropolitan railway bridge subjected to 2016 Gyeongju earthquake. J. Earthquake Eng. Soc. Korea20(7), 461–472 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dang-Vu, H., Lee, D. H., Shin, J. & Lee, K. Influence of shear-axial force interaction on the seismic performance of a piloti building subjected to the 2017 earthquake in Pohang Korea. Struct. Concr.21(1), 220–234 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee, D. H., Choi, E. & Zi, G. Evaluation of earthquake deformation and performance for RC bridge piers. Eng. Struct.27(10), 1451–1464 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee, D. H., Kim, W., Kim, D. J. & Kim, J. A new confinement scheme for reinforced concrete columns using stainless steel or glass fiber reinforced plastic. Structural Concrete22, 81–94 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee, D. H., Lee, J. H., Kim, D. J. & Kim, J. Experimental evaluation on the seismic performance of reinforced concrete bridge columns with high strength reinforcement. Struct. Concr.18(9), 81–94 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee, J. Y., Choi, S. H. & Lee, D. H. Structural behaviour of reinforced concrete beams with high yield strength stirrups. Magazine of Concrete Research68(23), 1187–1199 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee, J. Y., Lee, J. H., Lee, D. H., Hong, S. J. & Kim, H. Y. Practicability of large-scale reinforced concrete beams using grade 80 stirrups. ACI Struct. J.115(1), 269–280 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeon JS, Shafieezadeh A, Lee DH, Choi E, DesRoche R. Damage assessment of older highway bridges subjected to three-dimensional ground motions: characterization of shear-axial force interaction on seismic fragilities. Engineering Structures 87;87:47–57.

- 10.Jeon, J. S., DesRoches, R. & Lee, D. H. Post-repair effect of column jackets on aftershock fragilities of damaged RC bridges subjected to successive earthquakes. Earthquake Eng. Struct. Dyn.45(7), 1149–1168 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee, D. H., Kim, D. & Lee, K. Analytical approach for the earthquake performance evaluation of repaired/retrofitted rc bridge piers using time-dependent element. Nonlinear Dynamics56, 463–482 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee, D. H., Park, J., Lee, K. & Kim, B. H. Nonlinear seismic assessment for the post-repair response of rc bridge piers. Composites Part B: Engineering42, 1318–1329 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saatcioglu, M. & Ozcebe, G. Response of reinforced concrete columns to simulated seismic loading. ACI Structural Journal86(1), 3–12 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li, Z., Yu, C., Xie, Y., Ma, H. & Tang, Z. Size effect on seismic performance of high-strength reinforced concrete columns subjected to monotonic and cyclic loading. Engineering Structures183, 206–219 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su, J., Wang, J., Li, Z. & Liang, X. Effect of reinforcement grade and concrete strength on seismic performance of reinforced concrete bridge piers. Engineering Structures198, 109512 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 16.KIBSE (Korean Institute of Bridge and Structural Engineers). Concrete Bridge Design (Limit State Design Method) (KDS 24 14 21) Design Code and Commentary, KIBSE Seoul Korea. https://kcsc.re.kr/Search/ListCodes/102024 (in Korean). (2021).

- 17.HAZUS 99-SR2. Earthquake loss estimation methodology HAZUS, Technical Report. Federal Emergency Management Agency and National Institute of Buildings Science, Washington, DC, USA. (2004).

- 18.Dutta A, Mander JB. Capacity design and fatigue analysis of confined concrete columns. Technical Report. MCEER-98-0007, Multidisciplinary Center for Earthquake Engineering, State University of New York, Buffalo, NY, USA. (1998).

- 19.Ang, B. G., Priestley, M. J. N. & Paulay, T. Seismic shear strength of circular reinforced concrete columns. ACI Struct. J.86(1), 45–59 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belkacem, M. A., Bechtoula, H., Bourahla, N. & Belkacem, A. A. Effect of axial load and transverse reinforcements on the seismic performance of reinforced concrete columns. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng.13(2), 372–386 (2019). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.