Abstract

The high-resolution NMR structure of apolipophorin III from the sphinx moth, Manduca sexta, has been determined in the lipid-free state. We show that lipid-free apolipophorin III adopts a unique helix-bundle topology that has several characteristic structural features. These include a marginally stable, up-and-down helix bundle that allows for concerted opening of the bundle about “hinged” loops upon lipid interaction and buried polar/ionizable residues and buried interhelical H-bonds located in the otherwise hydrophobic interior of the bundle that adjust protein stability and facilitate lipid-induced conformational opening. We suggest that these structural features modulate the conformational adaptability of the lipid-free helix bundle upon lipid binding and control return of the open conformation to the original lipid-free helix-bundle state. Taken together, these data provide a structural rationale for the ability of exchangeable apolipoproteins to reversibly interact with circulating lipoprotein particles.

Exchangeable apolipoproteins constitute a functionally important family of proteins that play critical roles in lipid transport and lipoprotein metabolism (1). Available structural and biophysical data on members of this protein family indicate that lipid-free exchangeable apolipoproteins share a common molecular architecture, the elongated up-and-down amphipathic α-helix bundle (2–4). Contact with a lipid surface induces a conformational change in the helix bundle, wherein the protein opens about “hinged” loops that connect helical segments (3, 5). The open, lipid-associated conformation appears to be an extended α-helical structure that presents a continuous hydrophobic surface. A recently published NMR structure of apolipoprotein C-I in a lipid-mimetic environment supports this model (6). Further, the x-ray crystal structure of a human apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) N-terminal truncation mutant, apoA-I(Δ1–43), shows a continuously curved, extended α-helical structure that represents a putative lipid-bound conformation of this protein (7). A recently published secondary structure of an apoA-I C-terminal truncation mutant, apoA-I(Δ187–243), in the presence of SDS micelles, indicates a similar location of helix segments as shown in the x-ray crystal structure, although no tertiary interactions were observed between helices (8). Other experimental data, including monolayer balance (9), fluorescence spectroscopy (10), near UV circular dichroism spectroscopy (11), surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy (12), Fourier-transformed IR spectroscopy (13), and disulfide-bond engineering (14) support a conformational opening in helix-bundle exchangeable apolipoproteins upon lipid binding. This conformational adaptability raises the question as to which structural features in the lipid-free helix bundle regulate this process, and this question remains unanswered.

Apolipophorin III (apoLp-III) is a prototypical exchangeable apolipoprotein found in many insect species that functions in transport of diacylglycerol (DAG) from the fat body lipid storage depot to flight muscles in the adult life stage. This transport is in response to adipokinetic hormone-stimulated activation of fat body triacylglycerol lipase, which converts triacylglycerol into DAG. Newly generated DAG is then loaded onto pre-existing high-density lipophorin (HDLp), a process that converts HDLp to low density lipophorin (LDLp). This process partitions extra DAG into the lipophorin phospholipid surface (15), creating binding sites for apoLp-III. LDLp then circulates through the hemolymph and DAG is removed and delivered to flight muscle tissue. Reduction in the amount of surface localized DAG causes apoLp-III to dissociate from the particle, regenerating HDLp to complete a shuttle cycle. We report here a high-resolution NMR structure of lipid-free apoLp-III from the sphinx moth, Manduca sexta, which adopts a unique helix-bundle topology. We demonstrate that apoLp-III contains several characteristic structural features that modulate conformational opening of lipid-free apoLp-III upon lipid binding and control return of the open conformation to the original lipid-free helix-bundle state. Based on structural similarities with other lipid-free helix-bundle apolipoproteins, we anticipate that our results have important implications for understanding the molecular basis of exchangeable apolipoprotein–lipoprotein interactions.

Experimental Procedures

NMR Spectroscopy and Structure Determination.

NMR spectral resonances were assigned by using a series of three-dimensional (3D) NMR experiments (4). Two 3D nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY) experiments, 15N-edited NOESY and 13C-edited NOESY, were used to generate NOE distance restraints. A 3D HNHA experiment was used to obtain 3JαH-NH coupling constants that gave rise to φ dihedral angle restraints. The talos program was also used to predict the dihedral angles based on chemical shift information (16). Subsequently, structure calculations were performed based on 2,257 nonhydrogen-bond NOE restraints and 198 dihedral angle restraints with a simulated annealing protocol (17) using x-plor (version 3.1) (18). The NOE-derived distance restraints were given upper bounds of 2.7, 3.5, 5.0, and 6.0 Å based on the measured NOE intensities. Structure calculations were carried out semiautomatically by using a computer program to resolve ambiguous NOEs (19). Structure calculations were carried out in an iterative manner and each iteration generated 50 NMR structures. The generated structures were analyzed for identification of distance restraints with violations >0.3 Å. These NOEs were checked for ambiguity, followed by generation of a new distance restraint set for the next calculation. Ten iterations were carried out and the final iteration generated 50 structures with no NOE violations >0.3 Å or dihedral angle violations >2.0 degrees. Forty best-fit NMR structures were used for statistics calculation.

Structural Analysis.

The NMR structure of M. sexta apoLp-III and the x-ray crystal structures of human apolipoprotein E N-terminal domain and L. migratoria apoLp-III were analyzed by using procheck (20) and vadar (21) programs. Both programs analyze the coordinates of proteins and give secondary structure locations. The vadar program also provides the fractional solvent accessible surface area (ASA) of the side chain of each residue, as well as H-bonding information. From the ASA, we identified buried/partially buried polar and ionizable residues. The threshold used was an ASA <0.35. The dali program (22) was used to search helix-bundle proteins from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The coordinates of 20 typical helix bundles, including two-, three-, four-, and five-helix bundles, were submitted to dali. We also submitted the coordinates of two single-helix polypeptides in the dali search, to ensure that our search retrieved most helix-bundle proteins. A program has been written that automatically analyzes dali results and creates a list of PDB codes for potential helix-bundle proteins or proteins that contain helix-bundle domains. The PDB coordinates based on the list were downloaded and analyzed by using insightii and vadar. The same program was also used to summarize vadar results, including secondary structures, buried polar/ionizable residues and H-bond information.

Results and Discussion

Structure Description.

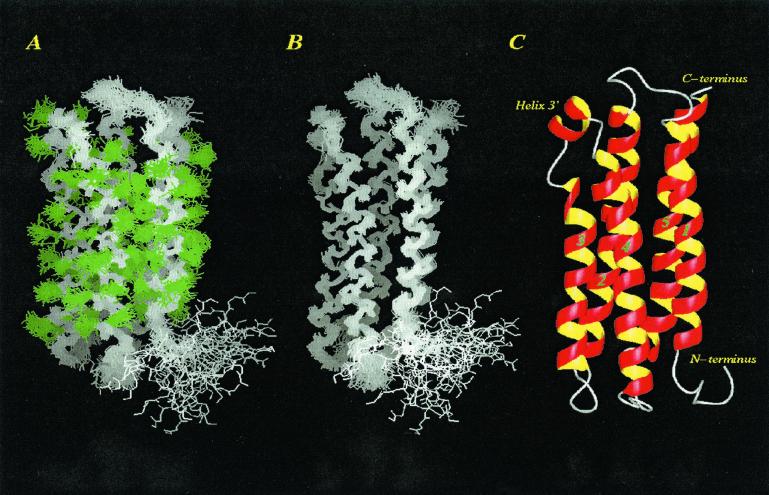

Fig. 1 depicts 40 best-fit NMR structures and a ribbon representation of the averaged structure of lipid-free M. sexta apoLp-III. The molecule consists of five long, amphipathic α-helices that form an up-and-down helix bundle with short loops connecting the helices. The bundle is organized in such a way that the hydrophobic faces orient toward each other, creating a hydrophobic core, whereas the hydrophilic surfaces are directed toward the solvent. Individual helical segments encompass the following amino acids: helix 1, residues 10–30; helix 2, residues 40–66; helix 3, residues 70–93; helix 3′, residues 95–100; helix 4, residues 104–128; and helix 5, residues 140–164. A striking aspect of the apoLp-III helix-bundle structure is the short helix, helix 3′, in terms of its location, orientation, and solvent-exposed nature. Analysis of the NMR structures indicates that side-chain heavy atoms located within the hydrophobic core are well defined, whereas atoms on hydrophilic surfaces are more flexible. Table 1 shows structural statistics and rms deviations (rmsds) for the ensemble of 40 structures, indicating a high-resolution NMR structure. The precision of the NMR structure allows for accurate analysis of H-bond patterns and tertiary contacts within the apoLp-III helix-bundle structure. procheck analysis indicated that 137 residues (82.5%) are located in most favored regions, 21 residues (12.7%) are in additional allowed regions, and five residues (3.0%) are in generously allowed regions of the Ramachandran plot. Three residues (1.8%), i.e., A8, N129, and M130, are in the disallowed regions. A8 is located in the N-terminal flexible tail. N129 and M130 are located in the loop between helix 4 and helix 5.

Figure 1.

NMR structure of lipid-free M. sexta apoLp-III. (A and B) Superposition of 40 best-fit NMR-derived structures of apoLp-III, with backbone atoms displayed in white and side-chain heavy atoms displayed in green. (C) Ribbon representation of an energy minimized, average structure of apoLp-III (PDB code 1EQ1). A and B were prepared by using insightii (Molecular Simulations, Waltham, MA), and C was prepared by using molmol (23).

Table 1.

Structural statistics for 40 best-fit NMR-derived structures of lipid-free M. sexta apoLp-III

| Structural statistics | 〈SA〉 | 〈SA〉 |

|---|---|---|

| rmsd (distance restraints) 〈Å〉* | ||

| All (2,257) | 0.018 ± 0.002 | 0.015 |

| Intra-residue (565) | 0.008 ± 0.002 | 0.005 |

| Sequential (569) | 0.015 ± 0.003 | 0.014 |

| Medium range (<i, i + 4) (532) | 0.013 ± 0.003 | 0.009 |

| Long range (>i, i + 4) (591) | 0.014 ± 0.003 | 0.012 |

| rmsd (torsion angle restraints) 〈deg〉† | ||

| Φ angles (108) | 0.46 ± 0.10 | 0.48 |

| s angles (90) | 0.34 ± 0.12 | 0.36 |

| x-plor energies (kcal mol−1) | ||

| E (total) | 159 ± 46 | 130 |

| E (bond) | 12 ± 1 | 10 |

| E (angle) | 55 ± 10 | 54 |

| E (improper) | 22 ± 2 | 23 |

| E (van der Waals) | 50 ± 3 | 53 |

| E (NOE) | 12 ± 1 | 11 |

| E (dihedral) | 1 ± 0.2 | 1 |

| rmsd from idealized geometry | ||

| Bonds (Å) | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Angle (deg) | 0.41 ± 0.02 | 0.40 |

| Improper (deg) | 0.35 ± 0.02 | 0.30 |

| Structural rmsd for secondary structure regions (Å) | ||

| Backbone | Heavy | |

| 〈SA〉 vs 〈SA〉‡ | 0.52 ± 0.12 | 1.09 ± 0.18 |

| 〈SA〉 vs 〈SA〉§ | 0.89 ± 0.25 | |

| 〈SA〉 vs 〈SA〉¶ | 1.55 ± 0.40 |

〈SA〉 is the energy minimized average structure of 40 NMR structures.

NOE force constant = 50 kcal/mole Å−2.

Torsion angle force constant = 200 kcal/mole Å−2.

Atoms of well-defined secondary structure regions: Residues 10–30, 40–66, 70–93, 103–128, and 140–164.

All heavy atoms of buried residues.

All heavy atoms of exposed residues.

Unique ApoLp-III Helix-Bundle Topology.

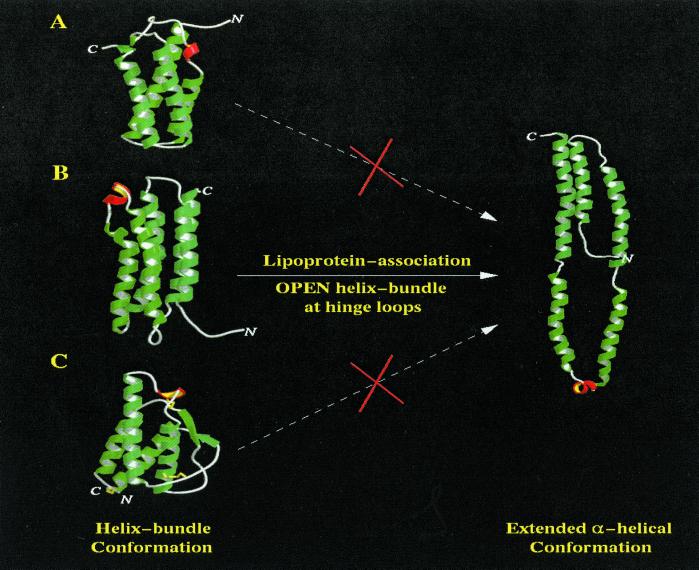

The helix-bundle structure of lipid-free apoLp-III is unable to bind lipid surfaces in the absence of a conformational change because its exposed surfaces are hydrophilic, whereas the hydrophobic faces are sequestered in the bundle. A conformational adaptation hypothesis has been proposed, first by Breiter et al. (3) for L. migratoria apoLp-III, then by Weisgraber (2) for apolipoprotein E N-terminal domain. In this model, interaction with a lipid surface induces helix-bundle opening about hinge loops at one end of the molecule, thereby exposing a continuous hydrophobic surface capable of binding to lipid surfaces. This hypothesis is widely accepted because it is supported by considerable experimental evidence, obtained by using different approaches (9–14). Using NMR techniques, evidence for a conformational adaptation of apoLp-III was obtained at the amino acid level (24). Furthermore, the NMR structures of apolipoprotein C-I (6) and apolipoprotein A-I(Δ187–243) (8), determined in a lipid-mimetic environment, display analogous open α-helical conformations. This hypothesis also suggests that any helix-bundle proteins capable of undergoing such a conformational adaptation will be able to reversibly bind to lipoprotein surfaces. However, physiologically only exchangeable apolipoproteins share such a biological function. This observation raises an important question as to why other helix-bundle proteins, such as chemokines or cytochrome c, are not able to bind to lipid surfaces. To address this question, we searched the PDB for all helix-bundle proteins. Our rationale was to compare helix-bundle topologies available in the PDB, to determine whether apoLp-III is a special helix bundle that is uniquely suited for lipid binding-induced conformational opening. Using the dali program, we located and downloaded a total of 636 helix-bundle proteins or proteins that contain helix-bundle domains. Further analysis using the insightii and vadar programs identified 149 unique helix-bundle structures, including two-, three-, four-, and five-helix bundles. We carefully studied each of these and compared them with apoLp-III. Our results indicated that apoLp-III indeed possesses a unique helix-bundle topology that is specially suited for lipid binding-induced conformational opening. Our results further identified two other helix bundles (lipid-free apolipoprotein E N-terminal domain and lipid-free L. migratoria apoLp-III) that share a similar bundle topology. Interestingly, all three proteins belong to the exchangeable apolipoprotein family. Their up-and-down helix bundle can easily open at hinge loops. As a consequence, an open conformation, exposing a large continuous hydrophobic surface, represents a feasible alternate, lipoprotein-associated state (Fig. 2B). Other helix bundles are unable to open because of their bundle topology. For example, chemokine proteins are up-up-down-down helix bundles (25) and cytochrome c is an up-and-down bundle with long loops that form short β-strands (26). These helix-bundle topologies do not permit a simple concerted opening because either the long loops form knots (IL-4; Fig. 2C) or the short β-sheet connecting the long loops will be disrupted (cytochrome c; Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Helix-bundle topology and conformational opening. In the apoLp-III helix bundle (B), short loops connecting long helices serve as hinges, about which helical segments in the bundle reposition, adopting an extended open α-helical structure. By contrast, in cytochrome c (A, PDB code 1CCH), the up-and-down helix bundle is connected by a long loop with a short β-strand, and in IL-4 (C, PDB code 1RCB), the up-up-down-down helix bundle is connected by long loops and a short β-strand. Opening of these helix bundles is hindered by the molecular organization of their respective bundles.

Helix 3′ and Lipid Surface Recognition.

Another distinct structural feature of the apoLp-III helix bundle is helix 3′. This short helix (-P95DVEKE100-), connects helix 3 and helix 4 in the bundle. It is located at one end of the molecule, exposed to solvent, adopting an orientation approximately perpendicular to the long axis of the bundle. Sequence alignment of apoLp-IIIs from four distinct lepidopeteran species reveals the highest degree of sequence conservation for this region, suggesting an important role in apoLp-III biological function. Interestingly, this short helix is also found in the apolipoprotein E N-terminal domain (four-helix bundle) and L. migratoria apoLp-III (five-helix bundle), but not in other helix bundles downloaded from the PDB. The short helix of the apolipoprotein E N-terminal domain comprises the most conserved sequence in this protein, although no specific biological function has been assigned to this region. Despite the fact that helix 3′ is short, its amino acid sequence is amphipathic, containing both hydrophobic and hydrophilic residues. A widely accepted concept, proposed by Segrest and coworkers (27), indicates that the amphipathic α-helix serves as a secondary structural motif for lipid binding. It is also envisioned that the apoLp-III helix bundle will initiate lipid binding through one end of the bundle (3). Thus, helix 3′ constitutes the best candidate amphipathic helix in apoLp-III to initiate contact with lipoprotein surface-binding sites. Direct experimental evidence, obtained from site-directed mutagenesis studies, indicates helix 3′ functions in apoLp-III recognition of lipid surfaces (28). We suggest that this helix, along with two long connecting helices (helix 3 and helix 4), constitute a “helix–short helix–helix” recognition motif for initiating apoLp-III interaction with lipoprotein surfaces (4). Another helix-bundle protein that has a topology similar to apoLp-III is the tail domain of human vinculin (29). Although this domain does not contain a short helix analogous to helix 3′, it is proposed that a “basic collar” region at one end of the bundle interacts with anionic lipid containing membrane surfaces. Following this, the five-helix bundle is proposed to undergo conformational opening in a manner analogous to apoLp-III as part of its role in the assembly of the actin cytoskeleton.

Buried Polar/Ionizable Residues and Helix-Bundle Opening.

Although apoLp-III possesses a unique bundle topology that allows for helix-bundle opening, it also contains characteristic structural features that regulate the conformational adaptation process. Lipid-free apoLp-III is a marginally stable protein (ΔG0H2O = 1.29 kcal/mol, ref. 10) and this marginal stability likely facilitates bundle opening. Whereas interhelical hydrophobic interactions confer stability to the bundle conformation, other structural features must be responsible for its inherent low stability. Using the vadar program, we found numerous polar residues (Gln, Asn, Ser, and Thr) and ionizable residues (Asp, Glu, His, Arg, and Lys), located in the otherwise hydrophobic interior of the bundle. Based on the NMR structure, we prepared a helix wheel diagram of apoLp-III (Fig. 3) that displays the location and orientation of residues in each of the five helices. A general conclusion obtained from this figure is that the hydrophobic surfaces of the helices in apoLp-III are rather small, especially those in helix 1 and helix 3, providing a structural basis for the low stability of the helix bundle. Furthermore, a total of 29 buried/partially buried polar/ionizable residues were identified in the helix bundle that also contributes to apoLp-III low stability. Using a color coding scheme, Fig. 3 not only identifies buried/partially buried polar/ionizable residues, completely buried hydrophobic residues, and completely exposed hydrophilic residues (based on their ASA values), it also provides accurate locations and orientations of these residues. In addition to the residues listed in Fig. 3, several buried polar/ionizable residues are located in loop regions and helix 3′. For example, K34 (ASA: 0.10) is located in loop 1 between helices 1 and 2, H94 (ASA: 0.21) is located in loop 3 between helices 3 and 3′, E98 (ASA: 0.23) is located on helix 3′, and N134 (ASA: 0.13) and K140 (ASA: 0.05) are located in the loop between helices 4 and 5. On the basis of this analysis, we postulate that the location and orientation of buried/partially buried hydrophilic residues serves to modulate apoLp-III stability. vadar results further indicated that several partially buried polar/ionizable residues are located on helix 5, including E153 (ASA: 0.34), E154 (ASA: 0.29), Q156 (ASA: 0.33), and K158 (ASA: 0.38), making helix 5 the most weakly associated helix in the apoLp-III helix bundle.

Figure 3.

Helix wheel diagram of the apoLp-III five-helix bundle. Each circle represents one residue and is labeled by sequence number and amino acid. The color code indicates residues with different ASA values based on vadar calculation. Residues have been classified as indicated.

Five completely buried hydrophilic residues orient toward the hydrophobic center (E13, Q20, S47, T115, and S119), whereas nine completely/partially buried hydrophilic residues are positioned between helices 2 and 3 (N40, K44, D48, S55, S58, E77, R80, E84, and E88), and five completely/partially buried polar/ionizable residues are found between helices 1 and 4 (E10, K17, S24, K105, and Q109). In contrast, two partially buried hydrophilic residue are present between helices 1 and 5 (Q26 and Q156), and between helices 3 and 4 (T76 and E118), with four buried/partially buried hydrophilic residues observed between helices 2 and 5 (Q60, D147, H151, and E154). In addition, Fig. 3 demonstrates that helix–helix interactions between helices 3 and 4, between helices 2 and 5, and between helices 1 and 5 are hydrophobic, whereas helix interfaces between helices 2 and 3 and helices 1 and 4 are much less hydrophobic, containing many buried/partially buried hydrophilic residues. These results suggest that the interface between helices 2 and 3 and between helices 1 and 4 are less stable. As a consequence, the preferred bundle opening occurs about short hinged loops that connect helices 2 to 3 and helices 4 to 5 (Fig. 2). This event creates an α-helical open conformation with helices 3 and 4 on one side and helices 1, 2, and 5 on the other, consistent with earlier disulfide-bond engineering experiments (14). In this manner, the spatial arrangement of buried polar/ionizable residues provides a structural rationale for the specific helix repositioning that occurs during conformational opening.

The intrinsic low stability of lipid-free apoLp-III is crucial for reversible lipoprotein-binding activity. The presence of buried polar/ionizable residues, which affect bundle stability, provide a structural basis for this property. Soulages and coworkers (12) reported a binding constant in the μM range for apoLp-III–lipid interaction. A μM binding constant corresponds to a binding free energy of ≈8 kcal/mole. In the case of a stable helix bundle, helix–helix interactions will be dominant, resulting in maintenance of the bundle state rather than bundle opening upon recognition of a lipid surface. On the other hand, a minimum intrinsic stability is required so that apoLp-III can efficiently return to its helix-bundle conformation after release from a lipoprotein surface. In this sense, buried polar/ionizable residues in the lipid-free helix-bundle modulate apoLp-III conversion between lipid-free and lipid-associated states, whereas the intrinsic marginal stability of the bundle facilitates both conformational opening and recovery of the lipid-free helix bundle. The fact that the observed free energy of unfolding of most lipid-free apolipoproteins is <4.5 kcal/mole (30), supports this concept. Other helix bundles, such as ROP dimer, adopt a stable up-and-down four-helix bundle with no short helix (ΔG0H2O = 17.1 kcal/mole for the dimer; ref. 31). The high stability of this helix bundle would preclude opening in the presence of lipids.

Buried H-Bonds, Buried Salt Bridges, and ApoLp-III Helix-Bundle Recovery.

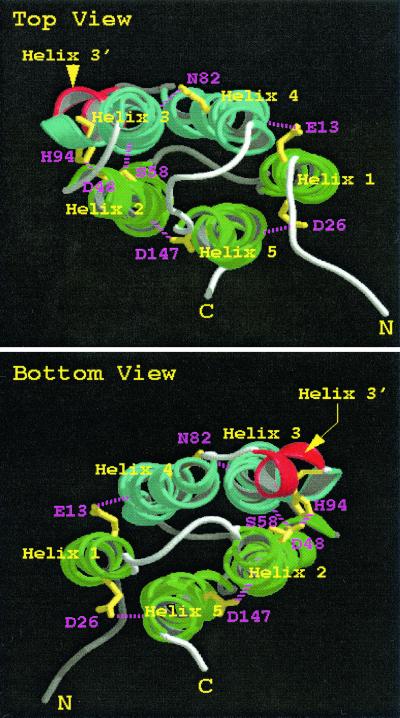

vadar analysis further indicates that several buried polar/ionizable residues form buried hydrogen bonds (Fig. 4). Table 2 lists 12 interhelical H-bonds observed in apoLp-III, including buried, partially buried, and completely exposed interhelical H-bonds, as well as two potential buried salt bridges. Four buried H-bonds are identified, including H-bonds between E13 and V116 (helices 1 and 4), between D48 and H94 (helix 2 and loop3), between S58 and E84 (helices 2 and 3), and between F57 and D147 (helices 2 and 5). The rest are either partially buried or completely exposed. It is worth noting that the side chains of hydrophobic residues cannot serve as H-bond donors or acceptors. Rather, it is buried polar/ionizable residues that provide donors and acceptors to form buried H-bonds in the hydrophobic interior of the apoLp-III helix bundle. Lipid-induced conformational opening effectively replaces hydrophobic helix–helix interactions in the bundle by hydrophobic helix–lipid interactions in the apoLp-III–lipid complex. Given the increased stability of lipid-associated apoLp-III (10), the open conformation will be retained until metabolic processes eliminate lipoprotein surface binding sites, resulting in apoLp-III release from the lipoprotein surface. Recovery of the specific apoLp-III helix-bundle conformation requires specific driving forces. It is anticipated that, upon release from a lipoprotein surface, the initial force driving recovery of the bundle conformation is re-establishment of interhelical hydrophobic interactions that are rather unspecific. This reorganization occurs because an exposed hydrophobic surface in the open conformation is unstable, and reforming helix–helix hydrophobic contacts to a form helix bundle avoids this situation. However, buried H-bonds located in the otherwise hydrophobic interior provide a specific driving force for recovery of apoLp-III's unique helix-bundle state from a lipid-bound open conformation.

Figure 4.

Interhelical H-bonds in the helix bundle. Top view (Upper) and bottom view (Lower) of the helix bundle. Buried H-bonds are highlighted by pink dotted lines. Light blue helices are helices 3 and 4, green helices are helices 1, 2, and 5.

Table 2.

Interhelical H-bonds and potential buried salt bridges in M. sexta apoLp-III

| H1 | L1 | H2 | H3 | L3 | H4 | H5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helix 1 | — | ND | ND | ND | ND | E13s–V116b* | Q26s–H160s |

| 0.10–0.16 | 0.18–0.63† | ||||||

| Q26s–H160s | |||||||

| 0.18–0.63 | |||||||

| Loop 1 | ND | — | ND | ND | ND | ND | S33s–A163b |

| 0.53–0.08 | |||||||

| Helix 2 | ND | ND | — | S58s–E84s | D48s–H94s | ND | Q53s–E154s |

| 0.01–0.32 | 0.07–0.21 | 0.40–0.29 | |||||

| D48–H94 | F57b–D147s | ||||||

| 0.07–0.21 | 0.00–0.09 | ||||||

| Helix 3 | ND | ND | ND | — | ND | ND | ND |

| Helix 4 | K124s–E10s | E118s–N82s | — | D147–H151 | |||

| 0.57–0.33 | ND | ND | 0.15–0.41 | ND | 0.09–0.18 | ND | |

| E118s–N82s | |||||||

| 0.15–0.41 | |||||||

| Helix 5 | ND | ND | E154s–Q53s | ND | ND | ND | — |

| 0.29–0.40 |

ND: not detectable. Potential buried salt bridges, based on the distance between negatively charged and positively charged residues, are highlighted in bold.

The residues that are involved in the H-bonds, s: refers to side-chain atom, b: backbone atom. For example, E13s–V116b presents an H-bond between side-chain atom of E13 and backbone atom of V116.

The numbers represent fractional ASA of the residues that are involved in the H-bonds.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Central Research Committee award to J.W. from the Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Grant AHA 0130546Z from the American Heart Association, Midwest Affiliate (to J.W.), and grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL64159) and Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to R.O.R).

Abbreviations

- apoLp-III

apolipophorin III

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- NOE

nuclear Overhauser effect

- ASA

accessible surface area

- rmsd

rms deviation

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.rcsb.org (PDB ID code 1EQ1).

References

- 1.Breslow J L. Annu Rev Med. 1991;42:357–371. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.42.020191.002041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson C, Wardell M R, Weisgraber K H, Mahley R W, Agard D A. Science. 1991;252:1817–1822. doi: 10.1126/science.2063194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breiter D R, Kanost M R, Benning M M, Wesenberg G, Law J H, Wells M A, Rayment I, Holden H M. Biochemistry. 1991;30:603–608. doi: 10.1021/bi00217a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang J, Gagne S M, Sykes B D, Ryan R O. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17912–17920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.17912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weisgraber K H. Adv Protein Chem. 1994;45:249–302. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60642-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rozek A, Sparrow J T, Weisgraber K H, Cushley R J. Biochemistry. 1999;38:14475–14484. doi: 10.1021/bi982966h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borhani D W, Rogers D P, Engler J A, Brouillette C G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12291–12296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okon M, Frank P G, Marcel Y L, Cushley R J. FEBS Lett. 2001;487:390–396. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02375-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawooya J K, Meredith S C, Wells M A, Kézdy F J, Law J H. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:13588–13591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryan R O, Oikawa K, Kay C M. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:1525–1530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weers P M M, Kay C M, Oikawa K, Wientzek M, Van der Horst D J, Ryan R O. Biochemistry. 1994;33:3617–3624. doi: 10.1021/bi00178a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soulages J L, Salamon Z, Wells M A, Tollin G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5650–5654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raussens V, Narayanaswami V, Goormaghtigh E, Ryan R O, Ruysschaert J-M. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23089–23093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Narayanaswami V, Wang J, Kay C M, Scraba D G, Ryan R O. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26855–26862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang J, Liu H, Sykes B D, Ryan R O. Biochemistry. 1995;34:6755–6761. doi: 10.1021/bi00020a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cornilescu G, Delaglio F, Bax A. J Biomol NMR. 1999;13:289–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1008392405740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nigles M, Clore G M, Gronenborn A M. FEBS Lett. 1988;229:129–136. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80559-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brunger A T. x-plorManual. New Haven, CT: Yale Univ.; 1992. , version 3.1. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McInnes C, Wang J, O'Conner-McCourt M, Sykes B D. J. Biol. Chem. 1998. 27357–27363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laskowski R A, MacArthur M W, Moss D S, Thornton J M. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;47:110–119. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wishart D S, Willard L, Richards F M, Sykes B D. vadar: A Comprehensive Program for Protein Structure Evaluation. Edmonton, AB, Canada: University of Alberta; 1994. , version 1.2. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holm L, Sander C. J Mol Biol. 1993;233:123–138. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wuthrich K. J Mol Graphics. 1996;14:51–55. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Sahoo D S, Sykes B D, Ryan R O. Biochem Cell Biol. 1998;76:276–283. doi: 10.1139/bcb-76-2-3-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rozwarski D A, Gronenborn A M, Clore G M, Bazan J F, Bohm A, Wlodawer A, Hatada M, Karplus P A. Structure (London) 1994;2:159–173. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamtekar S, Hecht M H. FASEB J. 1995;9:1013–1022. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.11.7649401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Segrest J P, Garber D W, Brouillette C G, Harvey S C, Anantharamaiah G M. Adv Protein Chem. 1994;45:303–369. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60643-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Narayanaswami V, Wang J, Schieve D, Kay C M, Ryan R O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4366–4371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bakolitsa C, de Pereda J M, Bagshaw C R, Critchley D R, Liddington R C. Cell. 1999;99:603–613. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81549-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gursky O, Atkinson D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2991–2995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vlassi M, Cesareni G, Kokkinidis M. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:817–827. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]