Abstract

Harris County, Texas, remains at continuous risk to mosquito-borne diseases due to its geographic landscape and abundance of medically important mosquito vectors. Targeted mitigation of these mosquitoes requires accurate identification of these mosquitoes taxa. Currently, there is a paucity of genetic information to inform molecular identification and phylogenetic relationships beyond well-studied mosquito species. Here we utilized a genome skimming approach using shallow shot gun sequencing to generate data and assemble the mitochondrial genomes of 37 mosquito species collected in Harris County, Texas. This report includes the complete mitochondrial genome for 25 newly sequenced species spanning 10 genera; the genomes were consistent with reference genomes in the GenBank database having 37 genes (13 protein-coding, 2 rRNA and 22 tRNA), and average AT content of 78.74%. Bayesian and maximum likelihood tree topologies using just the easily aligned 13 concatenated protein coding genes confirmed phylogenetic placement of species for Aedes, Anopheles and Culex genera clustering in single clades as expected. Furthermore, this approach provided more robust phylogenetic placement/identity of study taxa when compared to the use of the traditional cytochrome oxidase I partial gene barcode sequence for molecular identification. This study demonstrates the utility of genome skimming as a cost-effective alternative approach to generate reference sequences for the validation of mosquito identification and taxonomic rectification, knowledge necessary for guiding targeted vector interventions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-04864-x.

Introduction

The steady expansion of human–vector interactions has facilitated the emergence and re-emergence of vector-borne diseases worldwide1,2. Among these vectors, mosquitoes contribute to an extensive list of illnesses which account for more than half of vector-related fatalities annually3. Notwithstanding the medical significance of mosquitoes as vectors, there is a clear disparity in the availability of genetic data in public databases4–7, demonstrating a bias towards a relatively small number of well-studied taxa in the Aedes, Anopheles and Culex genera4,8–11. Apart from the prominent species in these genera, there are a plethora of other mosquitoes, many belonging to morphologically cryptic species complexes which play a role in maintaining and driving pathogen transmission in human and non-human cycles12.

With a human population of over 4.8 million, Harris County is the most populous county in Texas and third most populous county in the United States13. The county’s geography consists predominantly of forests in the northern and eastern regions, with savanna grasslands and coastlands located in the southern and western regions. Houston, the largest city in the county, is situated in a gulf coastal plain ecosystem; built on flat topology with a vast system of bayous, human-created canals and rivers, making the city prone to recurrent flooding14. This ecosystem provides an optimal breeding environment for the 56 mosquito species recorded from Harris County. These mosquitoes are classified into 10 genera15 and approximately 25% of these species are of known medical importance. Harris County is well acquainted with outbreaks of mosquito-related illnesses predominately transmitted from Aedes and Culex species16–18, with recent reports from the Harris Country Public Health Mosquito and Vector Control Division (HCPH-MVCD) identifying pools of Culex mosquitoes testing positive for the West Nile Virus (WNV) after flooding events19. For mosquito control operations like HCPH-MVCD, surveillance of mosquito counts, species identification and when available, pathogen detection, drive decisions for mitigation strategies and public engagement.

Despite having well-trained personnel, misidentification of specimens can occur due to a myriad of factors including poor specimen quality. Misidentification is particularly common in species complexes, where mosquitoes are morphologically similar and may occupy similar ecological niches20–22. Inaccurate identification may lead to ambiguous surveillance data, which could have a negative impact on deployment and success of mitigation strategies23. Mosquito species are conventionally identified using taxonomic keys based on morphology, and often validated if necessary or possible with molecular barcodes targeting the cytochrome oxidase I gene (COI) and internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) regions24,25. However, traditional barcoding approaches like these are constrained by the paucity of genomic reference data available for comparison against query sequences26 and in power to redress taxonomic discrepancies in cryptic species complexes4,27. This emphasizes the importance of reference sequences from well-curated voucher specimens in genomic repositories such as NCBI’s GenBank database. These data may in turn may be used to develop rapid and cost-effective toolsets for accurate identification of mosquito taxa.

Over the last few decades, mosquito phylogenetics using molecular data ranging from short genetic sequences to full genomes have been of interest due the ability of genetic data to confirm taxonomy which has been historically been built on morphological characteristics4,7,10. Though morphological taxonomy remains an integral and valuable tool, molecular phylogenetics is important in compensating for limitations such as the accurate identification of cryptic species and damaged/incomplete specimens28–30. It is crucial to differentiate between vector and non-vector species for development and implementation of targeted mitigation strategies31. Advancements in sequencing technologies and computational approaches have facilitated a dramatic increase in genomic datasets including the mitochondrial genomes for a wide range of organisms including insects32–35. Mitochondrial genomes (mitogenomes) have proven successful in resolving species identification, population structure, molecular taxonomy and evolutionary studies of metazoans4,9,10,36. The mitogenome exists as a circular, double-stranded DNA molecule which encodes 2 ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes, 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs), 22 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes and a non-coding region control region (CR) associated with DNA and RNA synthesis. Characteristics such as a high copy number, absence of introns, low incidence of recombination and maternal inheritance contribute to the usefulness of the mitogenome in molecular identification and inferring well-supported phylogenies4,29. Use of the concatenated sequence of the 13 PCGs is the preferred choice for phylogenetic analyses within the mitogenome versus use of the full 37 genes, as the highly conserved tRNAs and complex secondary structure of the rRNA gene sequences may confound phylogenetic analysis37–39. Additionally, the vast majority of mitogenome analyses, including those for mosquitoes, have focused on the PCGs, have proven highly informative, and allows for more direct comparison between different studies5,10,40.

Genetic information of any kind for the mosquitoes of Harris County is currently limited, with publicly available data for less than 30% of the 56 mosquito species that have been recorded and are considered present. To strengthen the capacity of the HCPH-MVCD for accuracy and confirmation of identification of damaged specimens or cryptic species using molecular and phylogenetic approaches, this study aimed to (i) generate complete mitochondrial reference genomes for well-curated mosquito specimens from Harris County and (ii) demonstrate the resolution of phylogenetic approaches using mitogenomes to inform species identification among morphologically cryptic taxa within the Culicidae.

Results

Mosquito collection

Specimens of 37 of the 56 known mosquito species reported from Harris County were collected in April 2022 and from January to December 2023. These species represented 10 Culicidae genera (Aedes, Anopheles, Culex, Culiseta, Coquillettidia, Mansonia, Othopodomyia, Psorophora, Toxorhynchites and Uranotaenia) from diverse habitats.

Sequencing, mitochondrial genome statistics and characteristics

The 37 single mosquito specimens yielded a total of 1,213,000,000 paired end reads; ranging from 16.51 (Ae. vexans) to 63.64 (Ae. infirmatus) million reads each. This included genomic data for 25 newly characterized mitogenomes where no sequence data were previously available. Mitochondrial genome size was relatively consistent within genera with Or. signifera having the largest contig size of 17,190 bp and An. crucians the smallest contig size of 15,365 bp. For most species, less than 25% of the sequence reads from each specimen was used for mitogenome assembly (Table 1).

Table 1.

Statistics for 37 mosquito mitochondrial genomes from Harris County.

| Genus | Morphological ID | Total Reads | Assembled Reads | Contig size | % Mitogenome Reads* | Organelle coverage | GenBank Accession # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aedes (Ae.) | Ae. aegypti | 26975832 | 38310 | 16113 | 0.14 | 435 | PQ587029 |

| Ae. albopictus | 27246916 | 28710 | 15792 | 0.11 | 320 | PQ587030 | |

| Ae. atlanticus | 29085822 | 9494 | 15717 | 0.03 | 109 | PQ613903 | |

| Ae. canadensis | 41588598 | 72440 | 16751 | 0.17 | 737 | PQ613904 | |

| Ae. epactius | 33941702 | 12580 | 16642 | 0.04 | 130 | PQ613905 | |

| Ae. fulvus pallens | 41992456 | 103172 | 15857 | 0.25 | 1103 | PQ613906 | |

| Ae. hendersoni | 41401854 | 33370 | 16580 | 0.08 | 345 | PQ613907 | |

| Ae. infirmatus | 63647434 | 49556 | 15813 | 0.08 | 584 | PQ613908 | |

| Ae. sollicitans | 40134970 | 80518 | 16538 | 0.20 | 809 | PQ613909 | |

| Ae. taeniorhynchus | 43100752 | 20644 | 15334 | 0.05 | 243 | PQ587024 | |

| Ae. triseriatus | 37476150 | 32134 | 17147 | 0.09 | 326 | PQ613910 | |

| Ae. vexans | 16512148 | 8242 | 15913 | 0.05 | 98 | PQ613911 | |

| Anopheles (An.) | An. crucians | 20848844 | 24580 | 15365 | 0.12 | 275 | PQ613901 |

| An. quadrimaculatus | 34712696 | 8136 | 15461 | 0.02 | 94 | PQ613902 | |

| An. punctipennis | 21053782 | 27980 | 15435 | 0.13 | 307 | PQ587025 | |

| Culex (Cx.) | Cx. coronator | 16925452 | 3458 | 15539 | 0.02 | 44 | PQ587026 |

| Cx. erraticus | 20232184 | 1130 | 15587 | 0.01 | 339 | PQ587027 | |

| Cx. nigripalpus | 23130354 | 7152 | 15468 | 0.03 | 83 | PQ587035 | |

| Cx. quinquefasciatus | 30838686 | 25718 | 15586 | 0.08 | 302 | PQ587042 | |

| Cx. restuans | 21859126 | 11940 | 15587 | 0.05 | 136 | PQ587043 | |

| Cx. salinarius | 18230256 | 5882 | 15575 | 0.03 | 76 | PQ587044 | |

| Cx. tarsalis | 28299258 | 8182 | 15580 | 0.03 | 93 | PQ585801 | |

| Cx. territans | 28313248 | 20958 | 15819 | 0.07 | 224 | PQ587045 | |

| Culiseta (Cs.) | Cs. inornata | 17936044 | 2430 | 15731 | 0.01 | 33 | PQ587047 |

| Coquillettidia (Cq.) | Cq. perturbans | 23226770 | 14824 | 15815 | 0.06 | 165 | PQ587046 |

| Mansonia (Ma.) | Ma. titillans | 21894818 | 32954 | 16251 | 0.15 | 343 | PQ585800 |

| Orthopodomyia (Or.) | Or. signifera | 18279636 | 30842 | 17190 | 0.17 | 294 | PQ587048 |

| Psorophora (Ps.) | Ps. ciliata | 49189054 | 61290 | 15742 | 0.12 | 658 | PQ587050 |

| Ps. columbiae | 42164646 | 37394 | 16073 | 0.09 | 472 | PQ587031 | |

| Ps. cyanescens | 40042142 | 21948 | 15724 | 0.05 | 242 | PQ587051 | |

| Ps. discolor | 21490068 | 14198 | 16366 | 0.07 | 157 | PQ587032 | |

| Ps. ferox | 40215612 | 25340 | 15735 | 0.06 | 294 | PQ587028 | |

| Ps. horrida | 32592526 | 5448 | 16410 | 0.02 | 50 | PQ591851 | |

| Ps. longipalpus | 71315786 | 66448 | 15675 | 0.09 | 715 | PQ587033 | |

| Ps. mathesoni | 93442960 | 83096 | 15645 | 0.09 | 909 | PQ587034 | |

| Toxorhynchites (Tx.) | Tx. rutilus | 28588608 | 8104 | 15580 | 0.03 | 94 | PQ585799 |

| Uranotaenia (Ur.) | Ur. lowii | 35949868 | 13574 | 16360 | 0.04 | 57 | PQ587049 |

% Mitogenome reads were calculated as assembled reads in relation to total reads for the specimen. The rows shaded in bold indicate newly sequenced mitogenomes from this study.

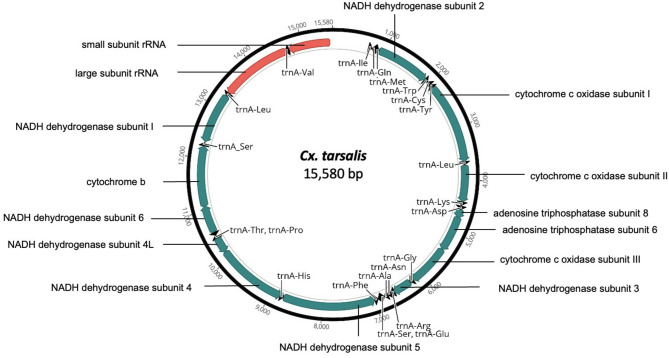

The mitogenomes generated in this study were comparable to reference mosquito mitogenomes retrieved from the GenBank database in encompassing 37 genes; 13 Protein Coding Genes (PCGs), 22 transfer RNAs (tRNAs), 2 ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs) and a control region (Fig. 1). Among the 10 genera, the length of the concatenated PCGs ranged from 11,220 bp for Cx. restuans to 11,243 bp for Ps. ciliata; with an average AT content of 78.74% (Table S1). Additionally, all mitochondrial genomes resulted in positive AT and negative GC skews (Table S2).

Fig. 1.

Structural representative of a mosquito mitochondrial genome of public health importance in Harris County, Texas. Culex tarsalis is usually captured at specific sites following flooding events. The teal, black and salmon color blocks represent the PCGs, tRNAs and rRNAs respectively.

Phylogenetic analysis and Culex species nucleotide diversity

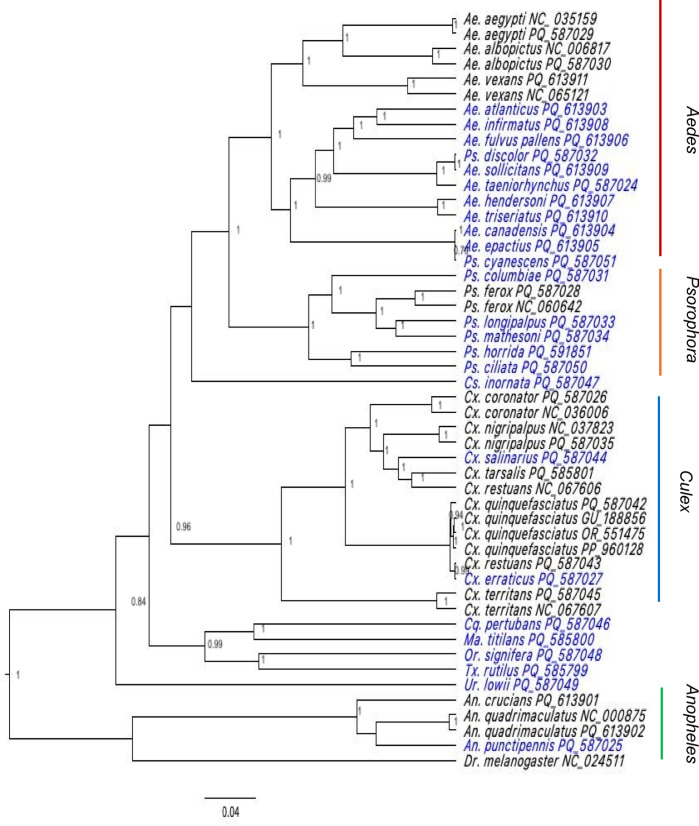

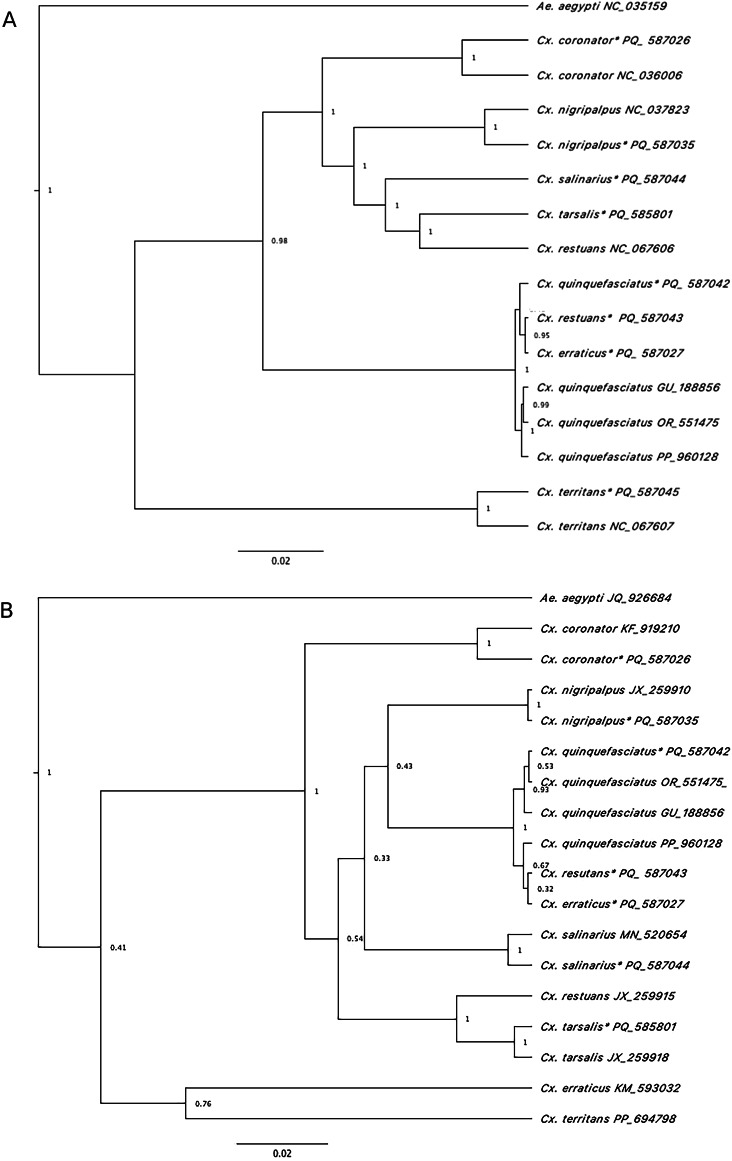

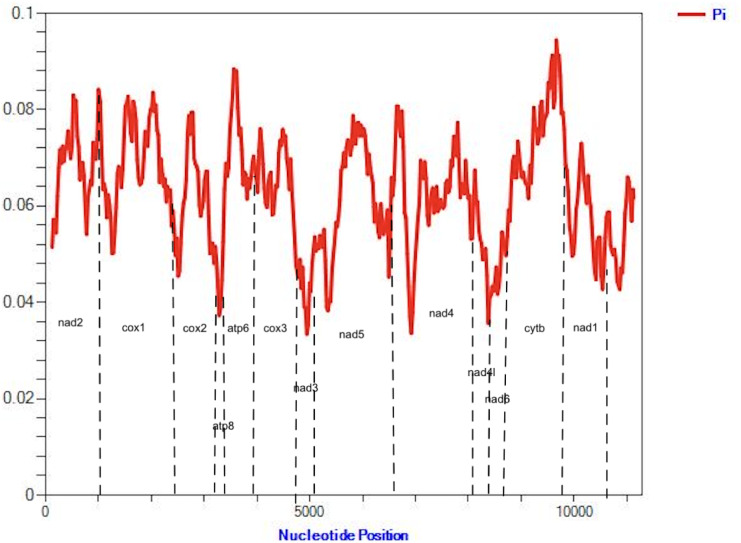

Maximum likelihood (Figure S1) and Bayesian analyses resulted in similar tree topologies, with Aedes, Anopheles, Culex and Psorophora genera separating into 4 strongly supported primary clades, demonstrating bootstrap values greater that 70% and posterior probabilities close to 1. Single specimens representing 4 other genera (Coquillettidia, Mansonia, Orthopodomyia, Toxorhynchites) separated into a single well-supported clade (Fig. 2). Single specimens representing Uranotaenia and Culiseta separated on single branches of their own. Mitogenomes from well-characterized species in this study cluster with reference genomes of the same species from the GenBank database except for Ps. cyanescens and Ps. discolor that clustered with Aedes species. Despite similar topologies, phylogenies using the 13 PCGs of the mitochondrial genome generally had better support compared to those utilizing only the commonly used COI region; species belonging to the Culex genus were utilized for this example for both Bayesian (Fig. 3) and maximum likelihood (Figure S2) analyses. Of note in the Culex-focused phylogenetic comparison, Cx. restuans NCBI reference sequence clustered with Cx. tarsalis in both analyses. Additionally, specimen sequences of Cx. restuans and Cx. erraticus derived from specimens from Harris County clustered with Cx. quinquefasciatus in both analyses rather then with reference sequences from those taxa where available (Fig. 3). Sliding window analysis demonstrated that nucleotide diversity (Pi) for Culex species were the highest for NAD2 (0.081), COXI (0.062), NAD5 (0.058) and NAD4 (0.053) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree for the 37 mosquito species from Harris County, Texas. Accession numbers starting with ‘PQ’ were sequenced in this study. Mitogenomes of the 25 species newly characterized are indicated with blue. The tree was constructed using the concatenated 13 PCGs using BEAST with the General Reversible Time (GTR + G + 1) model. Numbers at the nodes represent posterior probabilities based on Bayesian inferences.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic reconstruction using Bayesian Inference based on A. concatenated 13 PCGS of Culex species mitogenomes sequenced in the study (asterisk) and 7 Culex mitogenomes from NCBI GenBank B. Extracted COI genes from Culex species sequenced in this study (asterisk) and COI regions from Culex species on GenBank repository.

Fig. 4.

Sliding window analysis of protein coding genes among 8 Culex mosquito mitochondrial genomes sequenced in this study.

Discussion

Despite advancements in sequencing technologies, and the expanding medical importance of mosquitoes, there remains a dearth of mosquito sequence data—only a small proportion of known mosquito species have any sequence data publicly available. In NCBI’s GenBank repository, we found 12 reference accessions (Table S1) representing less than one quarter of the species historically reported from Harris County. Due to their correlation with the transmission of mosquito-borne diseases globally, “Ae. albopictus” or “Ae. Aegypti” generated more than 100 hits when compared to other medically significant mosquito species. Here we utilized a genome skimming approach to rapidly and inexpensively generate new mitogenomes for 37 mosquito species belonging to 10 genera. This shallow whole genome sequencing approach has been previously used for evolutionary investigations and mitochondrial genome recovery in a range of organisms including mosquitoes34,41–43.

More importantly, we were able to assemble complete mitogenomes with sufficient 30X to 339X higher organelle coverage using as little as 1% (Table 1) of the reads recovered from sequencing. This is the first report to generate novel sequence data and annotations for so many (n = 25) mosquito species from the United States in a single study.

The findings of low GC content, positive AT and negative GC skews in assemblages generated in this study and 37 genes are characteristic of mosquito mitochondrial genomes which have been reported across genera in earlier studies6,9,10,36. The phylogenetic relationships among Culicidae remains poorly characterized beyond well-studied vector species due to limitations in morphological identification, reference sequence data, reliable molecular markers, comparable data across collection series, and the growing recognition of cryptic species complexes. These facts lead to the unresolved phylogenetic status of species belonging to defined genera, some of which are common to Harris County. Although there has been an expansion in efforts to generate molecular information for a generous number of species, sampling efforts are often biased to known or targeted vector species, limited sampling efforts and data mining from sequence databases for understudied species4,7,10. During our sequence search for comparison and tree building strategies in this study, our 25 novel mitogenomes clustered within the broader Aedes, Anopheles, Culex and Psorophora genera with the under-represented Genus/species groups separating as expected (Fig. 2). However, outliers such as Ps. cyanescens and Ps. discolor fell within Aedes clades, which may be due to the unresolved taxonomic rectification of Psorophora and Aedes genera which are estimated to have diverged approximately 102 million years ago (MYA)7.

As an example of the greater resolution full mitogenomes provide over traditional barcoding approaches, we narrowed our focus to Culex species phylogenetics due to the long-term occurrence of West Nile virus outbreaks in Harris County and the continued incongruence of morphological identification with molecular analyses for members of this genus44–46. Many species belonging to the genus Culex have a global distribution. The genus is divided into subgenera which are then further split into subgroups, which adds to the complexity of species in this broad genus and the difficulty in rectifying taxonomic discrepancies. Many studies have used a range of strategies47,47,48 to understand the phylogenetic relationships of the Culex subgenus, with many focusing on complexities of the Pipiens group45,46. Notably, Cx. salinarius and Cx. restuans are nominotypical members of complexes together with Cx. quinquefasciatus in the Pipiens group. We were able to generate sequence data and assemble mitochondrial genomes for 8 Culex species (Table 1) from Harris County, including 2 new records that were not present in the GenBank database. Furthermore, phylogenetic analyses using Bayesian (Fig. 3A) and maximum likelihood (Figure S2A) approaches based on the 13 concatenated PCGs derived similar topologies, for Cx. quinquefasciatus representatives of the Pipiens group. However, both trees based on the concatenated PCGs resulted in stronger phylogenetic relationships when compared to using only the single COI gene for tree construction. Using just the single COI gene (barcode) is routinely utilized due to the easy acquisition of COI sequence data and absence of additional genomic data (Fig. 3B, S2B). However, the lack of discrete resolution within the Cx. quinquefasciatus cluster may be due to the biological complexities and genetic variability among members of this group , which was identified in previous studies49,50. Mitochondrial genome approaches have demonstrated limited power to discriminate between taxonomic groups where genetic introgression or hybridization may still occur51,52. Nuclear genomic data53,54 may provide the resolution required to unravel such biological complexities. such as hybridization and introgression in mosquito species complexes , which have shown to be limited when using mitochondrial analyses51,52.

Nucleotide diversity among protein coding genes vary across mosquito genera and prior studies have suggested that the NAD5 and NAD4, as well as other genes, may serve as more suitable targets for development of discriminatory markers for Culicidae55–57. Analysis of the protein coding genes of Culex species using a sliding window analysis (Fig. 4) demonstrated that NAD2, COXI, NAD5 and NAD4 have the highest nucleotide diversity, in that order, much more than the commonly used COXI gene. This suggests that these genes may have more potential for development of alternative barcoding tools for identification of these mosquito species4,5,36.

The rise in arboviral outbreaks in the Americas is unlikely to abate58. Approximately 25% of the mosquito species reported from Harris County are known to serve as vectors of arboviral pathogens, hence accurate identification of these species is critical for surveillance and design of appropriate mitigation strategies. The mitogenomes generated in this study will serve as reference sequences to verify accurate morphological identification both locally and globally. In addition, the 25 novel mitogenomes reported here significantly add to the volume of data currently available to better resolve the phylogenetic relationships among Culicidae taxa world-wide.

Methods

Sample collection and morphological identification

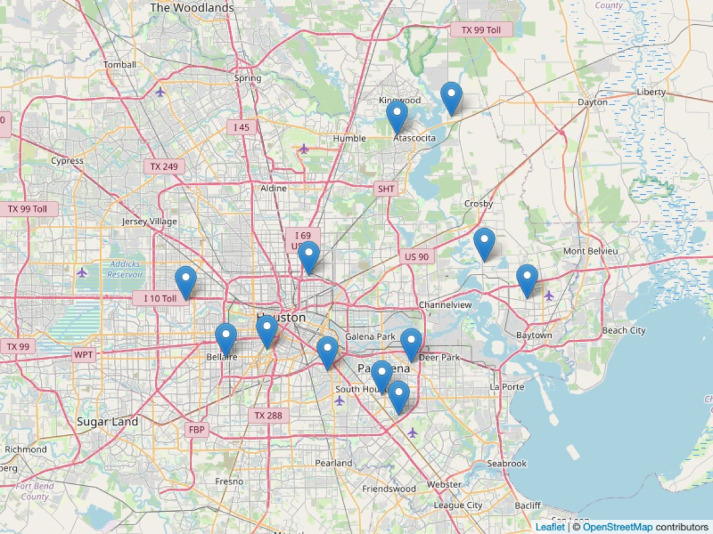

Mosquito specimens were collected in April 2022 and from January to December 2023 throughout Harris County during routine entomological surveys by the HCPH-MVCD (Fig. 5) using gravid and storm sewer traps (John W. Hock, Gainesville, FL). Adults were sorted and identified using a taxonomic key59 by HCPH-MVCD staff and targeted species of morphologically intact and verified specimens were shipped to the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (Maryland, U.S.A.) for molecular analysis.

Fig. 5.

Harris county entomology surveillance study sites This map was generated using the leaflet package(v.2.2.2) in R (v.4.2.1), with OpenStreetMap as a tile provider. Blue plots indicate locations of mosquito collections utilized for this study.

Total DNA extraction and sequencing

Single mosquito specimens were pre-processed using a previously described treatment60. Briefly, single specimens were incubated at 56 °C after homogenization in a cocktail mixture containing 98 μL of PK buffer (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA) and 2 μL of Proteinase K (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA). This was followed by an extraction protocol as described by the manufacturer (Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit, Hilden, Germany). Extracted DNA was quantified using the Qubit dsDNA assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and stored at − 20°C prior to sequencing and shipped to SeqCenter (Pittsburgh, USA) for library construction and sequencing on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 system. Libraries were sequenced to a minimum depth of 6.67 million paired-end 150 bp reads for species in the Anopheles, Coquillettidia, Culiseta, Mansonia, Orthopodomyia and Toxorhynchites genera; while specimens belonging to the Aedes, Culex, Psorophora and Uranotaenia genera were sequenced to a minimum depth of 13.3 million paired-end 150 bp reads.

Mitochondrial genome assembly, annotation and sequence analysis

Mitogenomes were assembled using NOVOPlasty (RRID:SCR_017335) version 4.3.161, with reference mitochondrial genomes (NC_035159, NC_014574, NC_064603, NC_054327, NC_060642) as seed sequences and k-mer set at 39. MITOchondrial genome annotation server (MITOS)62 was utilized for automated annotations using the invertebrate genetic code under default settings. Start and stop codon locations were manually adjusted in Geneious Prime (RRID:SCR_010519) version 2023.2.1 (Biomatters, Auckland, Australia) to match reference mosquito mitochondrial genomes, with sequences and annotations submitted to the GenBank database. DnaSP version 6 was used to calculate nucleotide diversities (Pi’s) among the PCGs genes using a sliding window approach over a 250 bp window which overlapped by 25 bp steps across the alignment of the 8 Culex mitochondrial genome sequences generated in this study.

Phylogenetic analysis

Using the MAFFT amino acid alignment mode as implemented in the Geneious Prime (RRID:SCR_010519) version 2023.2.1 (Biomatters, Auckland, Australia), the protein coding genes of the mitogenomes generated in this study and those from available mosquito reference sequences (NC_035159, NC_006817, NC_065121, NC_000875, NC_036006, NC_037823, NC_014574, NC_067606, NC_067607 and NC_060642) and Drosophila melanogaster sequence (NC_024511), were imported from the GenBank repository, aligned and exported in nexus format. The best fit base pair substitution model for the aligned sequence matrix was determined using jModelTest (v2.1.10) software63 under default settings according to Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). Phylogenetic analyses were performed using maximum likelihood in Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) X version 10.0.564 with bootstrap set at 1000 replicates and Bayesian inference analysis was performed in Bayesian Evolutionary Analysis by Sampling Trees (BEAST) 265 using three independent runs under default settings with an application of 20% burn-in rate for tree building purposes. Trees were visualized using FigTree v.1.4.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Harris County Public Health (HCPH), specifically the Mosquito Vector Control Division (MVCD) and the field staff involved in the collection of field material. Many thanks to Dr. Courtney Standlee for comments on the manuscript.

Author contributions

R.L.M.N.A., D.E.N., C.G. and J.M.P. conceived and designed the study. R.L.M.N.A. performed laboratory extractions, R.L.M.N.A. and C.G. completed bioinformatic analyses and annotations of the genomic datasets. M.A.S. coordinated and supervised field collections caried out by J.V., B.N., K.P., B.H. and J.V., I.H., J.V. and K.P. morphologically identified specimens. J.M.P., D.E.N. and E.J. attained funding, R.L.M.N.A., D.E.N., C.G. and J.M.P. drafted the manuscript. M.R., S.D.W.F, M.V. and H.R. provided logistic support, read and approved the manuscript with all authors.

Funding

This study was supported by funding from the NSF-Accelerator Project D-688: Computing the Biome (2134862).

Data availability

The datasets generated in this study are available on the NCBI database BioProject accession PRJNA1179547.The assembled mitochondrial sequences are openly available in the NCBI GenBank database under the accession numbers PQ585799 – PQ585801, PQ587024 – PQ587035, PQ587042 – PQ587051, PQ591851, PQ613901 – PQ613911.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Simard, F. The Mosquitome: A new frontier for sustainable vector control. in Mosquitopia: The Place of Pests in a Healthy World (eds. Hall, M. & Tamïr, D.) (Routledge, New York, 2022). [PubMed]

- 2.Schrama, M. et al. Human practices promote presence and abundance of disease-transmitting mosquito species. Sci. Rep.10, 13543 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vector-borne diseases. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/vector-borne-diseases.

- 4.Da Silva, A. F. et al. Culicidae evolutionary history focusing on the Culicinae subfamily based on mitochondrial phylogenomics. Sci. Rep.10, 18823 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.do Nascimento, B. L. S. et al. First description of the mitogenome and phylogeny of Culicinae species from the Amazon Region. Genes (Basel)12, 1983 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Ma, X. et al. First description of the mitogenome and phylogeny:Aedes vexans and Ochlerotatus caspius of the Tribe Aedini (Diptera: Culicidae). Infect. Genet. Evol.102, 105311 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soghigian, J. et al. Phylogenomics reveals the history of host use in mosquitoes. Nat. Commun.14, 6252 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Consortium, T. A. gambiae 1000 G. et al. Genome variation and population structure among 1142 mosquitoes of the African malaria vector species Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles coluzzii. Genome Res.30, 1533–1546 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Guo, J. et al. Complete mitogenomes of Anopheles peditaeniatus and Anopheles nitidus and phylogenetic relationships within the genus Anopheles inferred from mitogenomes. Parasite Vectors14, 452 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, D.-H. et al. Mitogenome-based phylogeny of mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). Insect Sci.31, 599–612 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foster, P. G. et al. Phylogeny of Anophelinae using mitochondrial protein coding genes. R. Soc. Open Sci.4, 170758 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferraguti, M. Mosquito species identity matters: Unraveling the complex interplay in vector-borne diseases. Infect. Dis.56, 685–696 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris County, Texas Population 2024. https://worldpopulationreview.com/us-counties/tx/harris-county-population.

- 14.Nava, M. R. & Debboun, M. A taxonomic checklist of the mosquitoes of Harris County, Texas. J. Vector Ecol.41, 190–194 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knight, K. L. & Stone, A. A Catalog of the Mosquitoes of the World (Diptera: Culicidae). (Entomological Society of America, 1977).

- 16.Rios, J., Hacker, C. S., Hailey, C. A. & Parsons, R. E. Demographic and spatial analysis of west nile virus and St. Louis encephalitis in Houston, Texas. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc.22, 254–263 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Murray, K. O. et al. Identification of dengue fever cases in Houston, Texas, with evidence of autochthonous transmission between 2003 and 2005. Vector-Borne Zoonot. Dis.13, 835–845 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez, D. et al. West Nile Virus Outbreak in Houston and Harris County, Texas, USA, 2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis.23, 1372–1376 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.West Nile virus found in dozens of mosquitoes in Harris County. https://www.houstonchronicle.com/politics/houston/article/westnilefoundacrossharriscounty-19521271.php.

- 20.Beebe, N. W. DNA barcoding mosquitoes: Advice for potential prospectors. Parasitology145, 622–633 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erlank, E., Koekemoer, L. L. & Coetzee, M. The importance of morphological identification of African anopheline mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) for malaria control programmes. Malar. J.17, 43 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng, Xl. Unveiling mosquito cryptic species and their reproductive isolation. Insect Mol. Biol.29, 499–510 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevenson, J. C. & Norris, D. E. Implicating cryptic and novel anophelines as malaria vectors in Africa. Insects8, 1 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jinbo, U., Kato, T. & Ito, M. Current progress in DNA barcoding and future implications for entomology. Entomol. Sci.14, 107–124 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan, A. et al. DNA barcoding: complementing morphological identification of mosquito species in Singapore. Parasit. Vectors7, 569 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moraes Zenker, M., Portella, T. P., Pessoa, F. A. C., Bengtsson-Palme, J. & Galetti, P. M. Low coverage of species constrains the use of DNA barcoding to assess mosquito biodiversity. Sci. Rep.14, 7432 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bohmann, K., Mirarab, S., Bafna, V. & Gilbert, M. T. P. Beyond DNA barcoding: The unrealized potential of genome skim data in sample identification. Mol. Ecol.29, 2521–2534 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jörger, K. M. & Schrödl, M. How to describe a cryptic species? Practical challenges of molecular taxonomy. Front. Zool.10, 59 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong, Z., Wang, Y., Li, C., Li, L. & Men, X. Mitochondrial DNA as a molecular marker in insect ecology: Current status and future prospects. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am.114, 470–476 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo, Y. et al. Molecular evidence for new sympatric cryptic species of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in China: A new threat from Aedes albopictus subgroup?. Parasit. Vectors11, 228 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson, A. L. et al. The importance of vector control for the control and elimination of vector-borne diseases. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.14, e0007831 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lamelas, L. et al. Complete mitochondrial genome of three species of the genus microtus (Arvicolinae, Rodentia). Animals10, 2130 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kneubehl, A. R. et al. Amplification and sequencing of entire tick mitochondrial genomes for a phylogenomic analysis. Sci. Rep.12, 19310 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoban, M. L. et al. Skimming for barcodes: rapid production of mitochondrial genome and nuclear ribosomal repeat reference markers through shallow shotgun sequencing. PeerJ10, e13790 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arcila-Galvis, J. E., Arango, R. E., Torres-Bonilla, J. M. & Arias, T. The Mitochondrial genome of a plant fungal pathogen Pseudocercospora fijiensis (Mycosphaerellaceae), comparative analysis and diversification times of the sigatoka disease complex using fossil calibrated phylogenies. Life11, 215 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.da Silva, F. S. et al. Sequencing and description of the complete mitochondrial genome of Limatus durhamii (Diptera: Culicidae). Acta Trop.239, 106805 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hudelot, C., Gowri-Shankar, V., Jow, H., Rattray, M. & Higgs, P. G. RNA-based phylogenetic methods: Application to mammalian mitochondrial RNA sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol.28, 241–252 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Butenko, A., Lukeš, J., Speijer, D. & Wideman, J. G. Mitochondrial genomes revisited: Why do different lineages retain different genes?. BMC Biol.22, 15 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang, L. et al. Complete mitochondrial genomes reveal robust phylogenetic signals and evidence of positive selection in horseshoe bats. BMC Ecol. Evol.21, 199 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones, C. M. et al. Complete Anopheles funestus mitogenomes reveal an ancient history of mitochondrial lineages and their distribution in southern and central Africa. Sci. Rep.8, 9054 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trevisan, B., Alcantara, D. M. C., Machado, D. J., Marques, F. P. L. & Lahr, D. J. G. Genome skimming is a low-cost and robust strategy to assemble complete mitochondrial genomes from ethanol preserved specimens in biodiversity studies. PeerJ7, e7543 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Papaiakovou, M. et al. Evaluation of genome skimming to detect and characterise human and livestock helminths. Int. J. Parasitol.53, 69–79 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ali, R., Gebhardt, M. E., Lupiya, J. S., Muleba, M. & Norris, D. E. The first complete mitochondrional genome of Anopheles gibbinsi using a skimming sequencing approach. F1000 Res.13, 553 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Harbach, R. E., Culverwell, C. L. & Kitching, I. J. Phylogeny of the nominotypical subgenus of Culex (Diptera: Culicidae): Insights from analyses of anatomical data into interspecific relationships and species groups in an unresolved tree. Syst. Biodivers.15, 296–306 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller, B. R., Crabtree, M. B. & Savage, H. M. Phylogeny of fourteen Culex mosquito species, including the Culex pipiens complex, inferred from the internal transcribed spacers of ribosomal DNA. Insect Mol. Biol.5, 93–107 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aardema, M. L., Olatunji, S. K. & Fonseca, D. M. The Enigmatic Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) species complex: Phylogenetic challenges and opportunities from a notoriously tricky mosquito group. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am.115, 95–104 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laurito, M., de Oliveira, T. M., Almirón, W. R. & Sallum, M. A. M. COI barcode versus morphological identification of Culex ( Culex ) (Diptera: Culicidae) species: a case study using samples from Argentina and Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz108, 110–122 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Montalvo-Sabino, E. et al. Description of new morphological variation of Culex (Culex) coronator Dyar and Knab, 1906 and first report of Culex (Carrollia) bonnei Dyar, 1921 found in the Central Region of Peru. Neotrop. Entomol.53, 987–996 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.García-Escobar, G. C. González, J. J. T. & Aguirre-Obando, O. A. Assessing phylogeographic patterns and genetic diversity in Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) via mtDNA sequences from public databases. Zool. Stud.63(58), 1–16 (2024).

- 50.Wilke, A. B. B., Vidal, P. O., Suesdek, L. & Marrelli, M. T. Population genetics of neotropical Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasit. Vectors7, 468 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Extensive introgression in a malaria vector species complex revealed by phylogenomics. Science. 347, 1258524 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Zadra, N., Rizzoli, A. & Rota-Stabelli, O. Chronological incongruences between mitochondrial and nuclear phylogenies of aedes mosquitoes. Life11, 181 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dietz, L. et al. Standardized nuclear markers improve and homogenize species delimitation in Metazoa. Methods Ecol. Evol.14, 543–555 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reidenbach, K. R. et al. Phylogenetic analysis and temporal diversification of mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) based on nuclear genes and morphology. BMC Evol. Biol.9, 298 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Demari-Silva, B. et al. Mitochondrial genomes and comparative analyses of Culex camposi, Culex coronator, Culex usquatus and Culex usquatissimus (Diptera:Culicidae), members of the coronator group. BMC Genom.16, 831 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.da Silva, F. S. et al. Mitochondrial genome sequencing and phylogeny of Haemagogus albomaculatus, Haemagogus leucocelaenus, Haemagogus spegazzinii, and Haemagogus tropicalis (Diptera: Culicidae). Sci. Rep.10, 16948 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Krzywinski, J. et al. Analysis of the evolutionary forces shaping mitochondrial genomes of a Neotropical malaria vector complex. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol.58, 469–477 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oropouche Fever in the Americas—Level 1–Level 1—Practice Usual Precautions—Travel Health Notices | Travelers’ Health | CDC. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/notices/level1/oropouche-fever-brazil.

- 59.Darsie, R. F. Identification and geographical distribution of the mosquitoes of North America, North of Mexico. Parasitology131, 580 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen, T.-Y. et al. A magnetic-bead-based mosquito DNA Extraction protocol for next-generation sequencing. Jove Vis. Exp.15, 170 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dierckxsens, N., Mardulyn, P. & Smits, G. NOVOPlasty: De novo assembly of organelle genomes from whole genome data. Nucleic Acids Res.45, e18 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bernt, M. et al. MITOS: Improved de novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol Phylogenet. Evol.69, 313–319 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Posada, D. jModelTest: Phylogenetic model averaging. Mol. Biol. Evol.25, 1253–1256 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C. & Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol.35, 1547–1549 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bouckaert, R. et al. BEAST 2: A software platform for bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comput. Biol.10, e1003537 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated in this study are available on the NCBI database BioProject accession PRJNA1179547.The assembled mitochondrial sequences are openly available in the NCBI GenBank database under the accession numbers PQ585799 – PQ585801, PQ587024 – PQ587035, PQ587042 – PQ587051, PQ591851, PQ613901 – PQ613911.