Abstract

We aimed to determine the clinical impact of prior vaccination against Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) on COVID-19 infection associated acute ischemic stroke (AIS). Using the TriNetX COVID-19 Research Network, an international electronic health record database, we identified AIS cases admitted between April 1, 2021 and September 30, 2022 that had a COVID-19 diagnosis up to 30 days before hospitalization. The study cohort was divided into two groups: those with and without vaccination against COVID-19. The two groups were matched for demographics, comorbidities, and antithrombotics taken before AIS with 1:1 propensity score matching. Cox proportional hazard analysis was performed to report primary (all-cause mortality) and secondary outcomes at 7 and 30 days after AIS. We identified 3,573 vaccinated (71 ± 12 (mean ± SD) years, 49% females) and 46,329 unvaccinated patients (65 ± 15 years, 45% females) who met the study criteria. After propensity score matching, 3,569 patients were in both groups. Vaccinated individuals had significantly lower rates of all-cause mortality [7 days: 3.3% vs 5.0%; HR = 0.66; 95% CI = 0.52–0.83 and 30 days: 8.2% vs 9.5%; HR = 0.83; 95% CI = 0.71–0.97], intracranial hemorrhage [7 days: 4.1% vs 6.2%; HR = 0.66; 95% CI = 0.53–0.82 and 30 days: 4.5% vs 6.7%; HR = 0.66; 95%CI = 0.53–0.81], venous thromboembolism [7 days: 3.5% vs 7.8%; HR = 0.44; 95% CI = 0.35–0.56 and 30-days: 4.6% vs 8.9%; HR = 0.51; 95% CI = 0.41–0.63] and acute myocardial infarction [7 days: 4.1% vs 7.0%; HR = 0.58; 95% CI = 0.46–0.73 and 30 days: 4.7% vs 7.6%; HR = 0.60; 95% CI = 0.49–0.75)]. Prior vaccination against COVID-19 is associated with reduced rates of all-cause mortality, intracranial hemorrhage, venous thromboembolism, and acute myocardial infarction within 30 days of COVID-19 associated AIS.

Subject terms: Stroke, Cerebrovascular disorders

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has had a profound impact on global health since December 2019. One potential complication of COVID-19 is acute ischemic stroke (AIS), especially in patients with cardiovascular disease1,2, which is associated with increased morbidity and mortality compared to AIS without COVID-192–4. Introducing vaccines against COVID-19 in December 2020 dramatically altered the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, with over 13.64 billion total vaccine doses administered worldwide5.

Vaccinations against COVID-19 have demonstrated efficacy in protecting against severe respiratory distress, averting hospitalization and long-term sequelae of COVID-19 infection. These vaccinations prevent severe COVID-19 infection and reduce the rates of hospitalization, intensive care unit admission, and emergency department visits during infection6. COVID-19 vaccination is also associated with reduced risk of AIS after COVID-19 infection7, as well as lower stroke severity at hospital discharge8 and at follow-up9. However, existing literature has not explored morbidity and mortality outcomes in COVID-19 infection associated AIS among patients with and without COVID-19 vaccination.

Considering that COVID-19 vaccination reduces the risk of complications such as AIS during infection, it may also be associated with lower risk of severe sequelae from AIS in the setting of COVID-19 breakthrough infection. Therefore, we compared the risk of mortality and serious complications between those with and without COVID-19 vaccination who experienced AIS in the setting of recent COVID-19 breakthrough infection (COVID-19-associated AIS cases) using a large, deidentified, international patient database.

Results

Baseline characteristics

On TriNetX, 3573 vaccinated and 46,329 unvaccinated patients who were hospitalized for AIS within 30 days of being infected with COVID-19 were identified, with an average age of 71 ± 12 years vs 65 ± 15 years, respectively (Table 1). After propensity score matching, 3,569 individuals remained in both the vaccinated and unvaccinated cohorts. Among 3569 patients in the vaccinated cohort, 2453 (68.7%) had received a Pfizer mRNA vaccine, 997 (27.9%) received a Moderna mRNA vaccine, and the remaining 119 (3.3%) received non-mRNA vaccines (either AstraZeneca or Johnson&Johnson).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with COVID-19 associated stroke before and after propensity matching

| Before matching | After matching | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Unvaccinated N = 46,329 | Vaccinated N = 3,573 | P Value | Std Diff | Unvaccinated N = 3,569 | Vaccinated N = 3,569 | P-Value | Std Diff |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age, overall, years | 65 ± 15 | 71 ± 12 | < 0.001 | 0.43 | 72 ± 12 | 71 ± 12 | <0.001 | 0.10 |

| Female | 20,818 (45) | 1733 (49) | <0.001 | 0.07 | 1742 (49) | 1729 (48) | 0.76 | 0.01 |

| White | 32,142 (69) | 2552 (71) | 0.01 | 0.05 | 2615 (73) | 2551 (72) | 0.09 | 0.04 |

| Black or African American | 8571 (19) | 728 (20) | 0.01 | 0.05 | 663 (19) | 725 (20) | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| Asian | 865 (2) | 85 (2) | 0.03 | 0.04 | 108 (3) | 85 (2) | 0.09 | 0.04 |

| Unknown race | 4530 (10) | 189 (5) | <0.001 | 0.17 | 164 (5) | 189 (5) | 0.17 | 0.03 |

| Medical History | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 24,745 (53) | 2938 (82) | < 0.001 | 0.65 | 2940 (82) | 2934 (82) | 0.85 | 0.004 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 16,583 (36) | 2385 (67) | <0.001 | 0.65 | 2352 (66) | 2381 (67) | 0.47 | 0.02 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 15,940 (34) | 1757 (49) | <0.001 | 0.30 | 1674 (47) | 1754 (49) | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| Coronary artery disease | 10,146 (22) | 1590 (45) | < 0.001 | 0.49 | 1510 (42) | 1586 (44) | 0.07 | 0.04 |

| Heart failure | 8318 (18) | 1321 (37) | < 0.001 | 0.44 | 1233 (35) | 1317 (37) | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Atrial fibrillation and flutter | 7183 (16) | 1136 (32) | < 0.001 | 0.39 | 1132 (32) | 1133 (32) | 0.98 | 0.001 |

| Overweight and obesity | 10,647 (23) | 1319 (17) | <0.001 | 0.31 | 1232 (35) | 1315 (37) | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 8263 (18) | 1383 (39) | < 0.001 | 0.48 | 1292 (36) | 1379 (39) | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| Chronic lower respiratory diseases | 9998 (22) | 1447 (41) | <0.001 | 0.42 | 1366 (38) | 1443 (40) | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| Tobacco use | 10,045 (22) | 576 (16) | < 0.001 | 0.14 | 510 (14) | 576 (16) | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| Ischemic stroke | 14,988 (32) | 1986 (56) | <0.001 | 0.48 | 1910 (54) | 1983 (56) | 0.08 | 0.04 |

| Nontraumatic intracerebral hemorrhage | 2322 (5) | 248 (7) | <0.001 | 0.08 | 235 (7) | 248 (7) | 0.54 | 0.02 |

| Nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage | 1179 (3) | 100 (3) | 0.36 | 0.02 | 92 (3) | 100 (3) | 0.56 | 0.01 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 5740 (12) | 693 (19) | <0.001 | 0.19 | 628 (18) | 693 (19) | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 2239 (5) | 349 (10) | <0.001 | 0.19 | 327 (9) | 347 (10) | 0.42 | 0.02 |

| Other venous embolism and thrombosis | 6164 (13) | 632 (18) | <0.001 | 0.12 | 552 (16) | 629 (18) | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| Medications | ||||||||

| Aspirin | 18,889 (41) | 2333 (65) | <0.001 | 0.51 | 2279 (64) | 2329 (65) | 0.22 | 0.03 |

| Clopidogrel | 7055 (15) | 1024 (29) | <0.001 | 0.33 | 993 (28) | 1022 (29) | 0.45 | 0.02 |

| Warfarin | 3702 (8) | 631 (18) | <0.001 | 0.29 | 596 (17) | 628 (18) | 0.32 | 0.02 |

| Apixaban | 3704 (8) | 658 (18) | <0.001 | 0.31 | 648 (18) | 655 (18) | 0.83 | 0.01 |

| Rivaroxaban | 1469 (3) | 297 (8) | <0.001 | 0.22 | 267 (8) | 295 (8) | 0.22 | 0.03 |

| Dabigatran | 213 (0.5) | 42 (1) | <0.001 | 0.08 | 43 (1) | 42 (1) | 0.91 | 0.003 |

Values are represented as mean (standard deviation) or N (% of column).

Vaccination against COVID-19 is associated with improved survival and reduced major complications in COVID-19-associated AIS cases

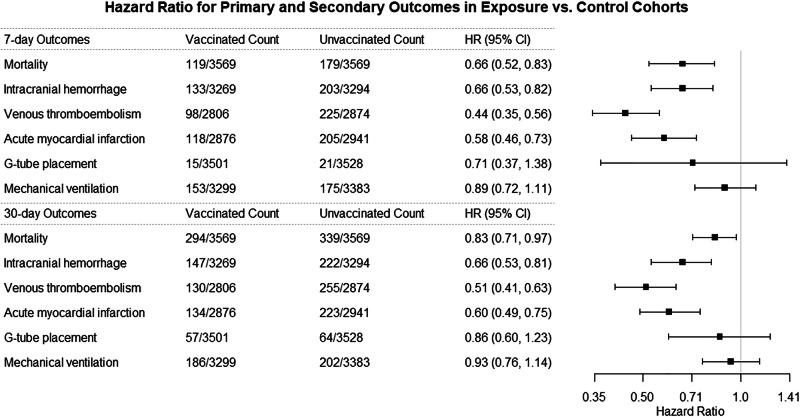

Among patients diagnosed with AIS within 30 days of COVID-19 infection, all-cause mortality was significantly lower in the vaccinated cohort compared to the unvaccinated cohort at 7 days (3.3% vs 5.0%; HR = 0.66; 95% CI = 0.52–0.83) and 30 days (8.2% vs 9.5%; HR = 0.83; 95% CI = 0.71–0.97) after AIS (Table 2, Fig. 1). Vaccinated patients also had lower rates of intracranial hemorrhage [7 days: 4.1% vs 6.2%; HR = 0.66; 95% CI = 0.53–0.82 and 30 days: 4.5% vs 6.7%; HR = 0.66; 95% CI = 0.53–0.81)], venous thromboembolism [7 days: 3.5% vs 7.8%; HR = 0.44; 95% CI = 0.35–0.56 and 30 days: 4.6% vs 8.9%; HR = 0.51; 95% CI = 0.41–0.63)] and acute myocardial infarction [7 days: 4.1% vs 7.0%; HR = 0.58; 95% CI = 0.46–0.73 and 30 days: 4.7% vs 7.6%; HR = 0.60; 95% CI = 0.49–0.75)] (Table 2, Fig. 1). There was no significant difference in the rates of mechanical ventilation and G-tube placement at 7 and 30 days between the two groups (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Table 2.

7- and 30-days outcome in propensity-matched COVID-19-associated stroke cases with and without vaccination

| All patients in study | Pfizer subgroup | Moderna subgroup | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccinated N = 3,569 Events / Subjects (% Risk) | Unvaccinated N = 3,569 Events / Subjects (% Risk) | HR (95% CI), P value, log rank test | Vaccinated N = 2,453 Events / Subjects (% Risk) | Unvaccinated N = 2,453 Events / Subjects (% Risk) | HR (95% CI) P value | Vaccinated N = 997 Events / Subjects (% Risk) | Unvaccinated N = 997 Events / Subjects (% Risk) | HR (95% CI) P value | |

| 7 days outcomes | |||||||||

| All-cause mortality | 119 / 3569 (3.3%) | 179 / 3569 (5.0%) | 0.66 (0.52, 0.83) | 77 / 2453 (3.1%) | 107 / 2453 (4.4%) | 0.71 (0.53, 0.95) | 41 / 997 (4.1%) | 41 / 997 (4.1%) | 0.99 (0.64, 1.52) |

| Intracranial hemorrhage* | 133 / 3269 (4.1%) | 203 / 3294 (6.2%) | 0.66 (0.53, 0.82) | 87 / 2256 (3.9%) | 139 / 2264 (6.1%) | 0.62 (0.48, 0.81) | 45 / 909 (5.0%) | 53 / 910 (5.8%) | 0.85 (0.60, 1.30) |

| Venous thromboembolic events* | 98 / 2806 (3.5%) | 225 / 2874 (7.8%) | 0.44 (0.35, 0.56) | 59 / 1979 (3.0%) | 150 / 2031 (7.4%) | 0.40 (0.29, 0.54) | 39 / 749 (5.2%) | 46 / 755 (6.1%) | 0.85 (0.56, 1.31) |

| Acute myocardial infarction* | 118 / 2876 (4.1%) | 205 / 2941 (7.0%) | 0.58 (0.46, 0.73) | 67 / 2016 (3.3%) | 149 / 2061 (7.2%) | 0.45 (0.34, 0.60) | 47 / 773 (6.1%) | 65 / 798 (8.1%) | 0.74 (0.51, 1.08) |

| G-tube placement* | 15 / 3501 (0.4%) | 21 / 3528 (0.6%) | 0.71 (0.37, 1.38) | 12 / 2406 (0.5%) | 12 / 2428 (0.5%) | 1.00 (0.45, 2.23) | 10 / 982 (1.0%) | 10 / 988 (1.0%) | 0.33 (0.07, 1.64) |

| Mechanical ventilation* | 153 / 3299 (4.6%) | 175 / 3383 (5.2%) | 0.89 (0.72, 1.11) | 105 / 2248 (4.7%) | 141 / 2321 (6.1%) | 0.76 (0.59, 0.98) | 56 / 938 (6.0%) | 44 / 942 (4.7%) | 1.3 (0.86, 1.90) |

| 30-days outcomes | |||||||||

| All-cause mortality | 294 / 3569 (8.2%) | 339 / 3569 (9.5%) | 0.83 (0.71, 0.97) | 192 / 2453 (7.8%) | 217 / 2453 (8.8%) | 0.85 (0.70, 1.03) | 97 / 997 (9.7%) | 96 / 997 (9.6%) | 0.98 (0.74, 1.29) |

| Intracranial hemorrhage* | 147 / 3269 (4.5%) | 222 / 3294 (6.7%) | 0.66 (0.53, 0.81) | 98 / 2256 (4.3%) | 149 / 2264 (6.6%) | 0.65 (0.50, 0.84) | 47 / 909 (5.2%) | 57 / 910 (6.3%) | 0.82 (0.56, 1.20) |

| Venous thromboembolic events* | 130 / 2806 (4.6%) | 255 / 2874 (8.9%) | 0.51 (0.41, 0.63) | 81 / 1979 (4.1%) | 178 / 2031 (8.8%) | 0.45 (0.35, 0.59) | 48 / 749 (6.4%) | 60 / 755 (7.9%) | 0.79 (0.54, 1.16) |

| Acute myocardial infarction* | 134 / 2876 (4.7%) | 223 / 2941 (7.6%) | 0.60 (0.49, 0.75) | 75 / 2016 (3.7%) | 162 / 2061 (7.9%) | 0.46 (0.35, 0.61) | 54 / 773 (7.0%) | 68 / 798 (8.5%) | 0.81 (0.57, 1.16) |

| G-tube placement* | 57 / 3501 (1.6%) | 64 / 3528 (1.8%) | 0.86 (0.60, 1.23) | 40 / 2406 (1.7%) | 45 / 2428 (1.9%) | 0.86 (0.56, 1.32) | 14 / 982 (1.4%) | 14 / 988 (1.4%) | 0.96 (0.46, 2.02) |

| Mechanical ventilation* | 186 / 3299 (5.6%) | 202 / 3383 (6.0%) | 0.93 (0.76, 1.14) | 129 / 2248 (5.7%) | 163 / 2321 (7.0%) | 0.80 (0.64, 1.01) | 67 / 938 (7.1%) | 53 / 942 (5.6%) | 1.3 (0.88, 1.82) |

*The denominator is less than the total number listed in the column header due to exclusion of patients who had a outcome of interest before the index stroke. New outcome of interest that occurred only after the index stroke were calculated.

Fig. 1. Outcomes of COVID-19-associated AIS cases with and without COVID-19 vaccination.

Comparison of outcomes at 7 and 30 days between propensity-score matched COVID-19-associated AIS cases in the exposure (vaccinated) and control (unvaccinated) cohorts.

The association between COVID-19 vaccination, mortality, and morbidity in COVID-19-associated AIS cases varies by vaccination type

Within the exposure cohort in TriNetX, 2460 patients received the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine, and 997 patients received the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine (Supplementary Table 3 and 4). Compared to the unvaccinated cohort, patients who received the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine had lower rates of all-cause mortality, although this was only significant at the 7 day timepoint [7 days: 3.1% vs 4.4%; HR = 0.71; 95% CI = 0.53–0.95 and 30 days: 7.8% vs 8.8%; HR = 0.85; 95% CI = 0.70–1.03)] (Table 2). The Pfizer COVID-19 cohort also experienced reduced rates of intracranial hemorrhage [7 days: 3.9% vs 6.1%; HR = 0.62; 95% CI = 0.48–0.81 and 30 days: 4.3% vs 6.6%; HR = 0.65; 95% CI = 0.50–0.84)], venous thromboembolism [7 days: 3.0% vs 7.4%; HR = 0.40; 95% CI = 0.29–0.54 and 30 days: 4.1% vs 8.8%; HR = 0.45; 95% CI = 0.35–0.59], and acute myocardial infarction [7 days: 3.3% vs 7.2%; HR = 0.45; 95% CI = 0.34–0.60 and 30 days: 3.7% vs 7.9%; HR = 0.46; 95% CI = 0.35–0.61] at 7 and 30 days after hospitalization (Table 2). They also displayed lower rates of mechanical ventilation at 7 days but not at 30 days after hospitalization. There was no significant difference in G-tube placement between the two cohorts (Table 2).

Compared to the unvaccinated cohort, patients who received the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine did not display significant differences in all-cause mortality, intracranial hemorrhage, venous thromboembolism, acute myocardial infarction, mechanical ventilation, or G-tube placement at 7- and 30-days after hospitalization (Table 2).

The association between COVID-19 vaccination, mortality, and morbidity in COVID-19-associated AIS cases varies by viral variant

In the first temporal segment of the study (April 1, 2021 to November 30, 2021), when the Delta variant of COVID-19 was prevalent, vaccination against COVID-19 was associated with reduced rates of intracranial hemorrhage [7 days: 3.6% vs 7.0%; HR = 0.52; 95% CI = 0.37–0.73 and 30 days: 4.0% vs 7.7%; HR = 0.51; 95% CI = 0.37–0.71], venous thromboembolism [7 days: 3.2% vs 9.4%; HR = 0.33; 95% CI = 0.23–0.48 and 30 days: 4.0% vs 10.7%; HR = 0.36; 95% CI = 0.26–0.50] and acute myocardial infarction [7 days: 4.3% vs 8.5%; HR = 0.50; 95% CI = 0.36–0.70 and 30 days: 4.9% vs 9.2%; HR = 0.52; 95% CI = 0.38–0.71] (Table 3). There was no association with reduced mortality in the vaccinated cohort.

Table 3.

Seven- and thirty-day outcomes in propensity-matched COVID-19-associated stroke cases at two different timepoints

| Part 1: April 1, 2021 to November 30, 3021 (Delta variant period) | Part 2: December 01, 2021 to September 30, 2022 (Omicron variant period) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccinated N = 1543 Events / Subjects (% Risk) | Unvaccinated N = 1543 Events / Subjects (% Risk) | HR (95% CI), P value, log rank test | Vaccinated N = 2083 Events / Subjects (% Risk) | Unvaccinated N = 2083 Events / Subjects (% Risk) | HR (95% CI) P value, log rank test | |

| 7 days outcomes | ||||||

| All-cause mortality | 42 / 1543 (2.7%) | 56 / 1543 (3.6%) | 0.74 (0.50, 1.10) | 81 / 2083 (3.9%) | 102 / 2083 (4.9%) | 0.78 (0.59, 1.05) |

| Intracranial hemorrhage* | 51 / 1399 (3.6%) | 97 / 1390 (7.0%) | 0.52 (0.37, 0.73) | 86 / 1917 (4.5%) | 109 / 1923 (5.7%) | 0.79 (0.59, 1.04) |

| Venous thromboembolic events* | 38 / 1205 (3.2%) | 114 / 1219 (9.4%) | 0.33 (0.23, 0.48) | 59 / 1631 (3.6%) | 136 / 1695 (8.0%) | 0.44 (0.33, 0.60) |

| Acute myocardial infarction* | 53 / 1225 (4.3%) | 107 / 1264 (8.5%) | 0.50 (0.36, 0.70) | 67 / 1684 (4.0%) | 132 / 1719 (7.7%) | 0.51 (0.38, 0.69) |

| G-tube placement* | 10 / 1514 (0.7%) | 13 / 1512 (0.9%) | 0.61 (0.25, 1.47) | 10 / 2041 (0.5%) | 14 / 2063 (0.7%) | 0.43 (0.16, 1.11) |

| Mechanical ventilation* | 55 / 1425 (3.9%) | 73 / 1455 (5.0%) | 0.76 (0.54, 1.08) | 102 / 1932 (5.3%) | 92 / 1976 (4.7%) | 1.13 (0.85, 1.50) |

| 30-days outcomes | ||||||

| All-cause mortality | 110 / 1543 (7.1%) | 122 / 1543 (7.9%) | 0.87 (0.67, 1.12) | 195 / 2083 (9.4%) | 201 / 2083 (9.7%) | 0.93 (0.77, 1.14) |

| Intracranial hemorrhage* | 56 / 1399 (4.0%) | 107 / 1390 (7.7%) | 0.51 (0.37, 0.71) | 96 / 1917 (5.0%) | 115 / 1923 (6.0%) | 0.83 (0.63, 1.09) |

| Venous thromboembolic events* | 48 / 1205 (4.0%) | 131 / 1219 (10.7%) | 0.36 (0.26, 0.50) | 80 / 1631 (4.9%) | 156 / 1695 (9.2%) | 0.52 (0.40, 0.68) |

| Acute myocardial infarction* | 60 / 1225 (4.9%) | 116 / 1264 (9.2%) | 0.52 (0.38, 0.71) | 77 / 1684 (4.6%) | 141 / 1719 (8.2%) | 0.55 (0.41, 0.72) |

| G-tube placement* | 29 / 1514 (1.9%) | 33 / 1512 (2.2%) | 0.85 (0.52, 1.40) | 28 / 2041 (1.4%) | 43 / 2063 (2.1%) | 0.63 (0.39, 1.01) |

| Mechanical ventilation* | 71 / 1425 (5.0%) | 93 / 1455 (6.4%) | 0.77 (0.56, 1.04) | 116 / 1932 (6.0%) | 100 / 1976 (5.1%) | 1.18 (0.90, 1.54) |

*The denominator is less than the total number listed in the column header due to exclusion of patients who had an outcome of interest before the index stroke. New outcome of interest that occurred only after the index stroke were calculated.

In the second temporal segment of the study (December 1, 2021 to September 30, 2022), when the Omicron variant of COVID-19 was prevalent, vaccination against COVID-19 was associated with reduced rates of venous thromboembolism [7 days: 3.6% vs 8.0%; HR = 0.44; 95% CI = 0.33–0.60 and 30 days: 4.9% vs 9.2%; HR = 0.52; 95% CI = 0.40–0.68] and acute myocardial infarction [7 days: 4.0% vs 7.7%; HR = 0.51; 95% CI = 0.38–0.69 and 30 days: 4.6% vs 8.2%; HR = 0.55; 95% CI = 0.41–0.72]. There was no association with reduced mortality or intracranial hemorrhage in the vaccinated cohort (Table 3).

Discussion

In this retrospective, observational, electronic health record (EHR) based study, we found that patients with COVID-19 infection-associated AIS who were previously vaccinated against COVID-19 displayed significantly greater survival at 7 days and 30 days after AIS compared to unvaccinated patients. It is unclear whether the reduced risk of mortality in the vaccinated cohort is due to reduced severity of AIS in this cohort or the fact that vaccinated patients were less likely to die from COVID-19 infection itself, or the combination of both effects. Our findings that vaccinated patients had better AIS-specific outcomes, suggest that severity of AIS may partially account for the reduced risk of overall mortality in the vaccinated cohort.

Vaccinated patients had also benefited from lower rates of post-AIS intracranial hemorrhage, venous thromboembolism, and acute myocardial infarction. It is well known that severe COVID-19 can trigger hypercoagulability and vascular damage10, so perhaps vaccination prevents progression to the point of such severe physiologic derangements and consequently reduces the risk of these cerebrovascular and cardiovascular insults. While mechanical ventilation and long-term enteral nutrition from G-tube placement due to dysphagia could be indirect measures of the stroke complications, there was no difference between vaccinated and unvaccinated groups.

Additionally, patients who received the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine experienced significantly better survival and lower rates of intracranial hemorrhage, venous thromboembolism, and acute myocardial infarction compared to unvaccinated patients; however, this relationship was not observed in the Moderna vaccine cohort. This suggests that Pfizer vaccination may more effectively reduce the risk of AIS sequelae after COVID-19 infection compared to Moderna vaccination. By contrast, there is evidence that the Moderna vaccine is more effective in preventing severe COVID-1911,12, so more research is needed into this comparison.

We also evaluated the relationship between COVID-19 vaccination and overall mortality and morbidity of COVID-19-associated AIS cases in the setting of distinct temporal periods that featured different dominant COVID-19 variants. Vaccinated patients experienced significantly reduced rates of venous thromboembolism and acute myocardial infarction during the periods of Delta and Omicron COVID-19 variant dominance. However, significant reduction in the risk of intracranial hemorrhage was only observed in the Delta variant dominant sub-analysis. Therefore, COVID-19 viral variant may function as a minor effect modifier with respect to the relationship between COVID-19 vaccination and morbidity in COVID-19-associated AIS cases.

One prior study evaluated if vaccination against COVID-19 triggers development of AIS and affects stroke outcomes. In this study, 78% (n = 45/58) of patients received a complete vaccination course (two doses)13. Among these, 36/45 patients developed neurological symptoms of AIS within 60 days of completing vaccination. There was no difference in mortality in previously vaccinated cases with AIS (13.8%) compared to unvaccinated AIS cases (8.6%, p = 0.23). In the current study, the effect of vaccine-related AIS was eliminated by including only patients who experienced AIS more than 60 days (2 months) after completing the full vaccination course. In this case, AIS cases with breakthrough COVID-19 infection and previous vaccination display lower mortality and morbidity compared to unvaccinated AIS cases.

There have been controversies if COVID-19 vaccination is associated with increased risk of AIS. A meta-analysis reported that the prevalence of AIS after COVID-19 vaccination is comparable to that in the general population14. In our study, patients in the vaccination exposure cohort had completed full course of COVID-19 primary vaccination at least two months before AIS. Hence, AIS is unlikely to have been due to COVID-19 vaccination.

There are several important limitations in this study that are inherent to the TriNetX database. As the patient EHR data available for analysis do not represent a random sample of all COVID-19-associated AIS cases, the results may not be generalizable to all patients who present with this combination of diagnoses. Although all patients in the vaccinated cohort and 95% of unvaccinated cohort were from the United States, about 5% of unvaccinated cohort were from other countries, the details of which are not known and this could potentially bias our study results. TriNetX does not provide information about cause of death, stroke severity, and etiology, limiting the interpretations that can be drawn as to why the association between COVID-19 vaccination and reduced morbidity and mortality in this patient population exists. Similarly, as this is a retrospective observational study, conclusions about a direction of causality in the relationship cannot be made, considering that unmeasured or uncontrolled confounders that were not or could not be matched for between the two cohorts may explain it.

Although the TriNetX platform does not support built-in power calculations, we conducted a post hoc analysis using SAS to assess statistical power in the Moderna subgroup. Given the sample size and observed effect sizes, the estimated power to detect differences across key outcomes was low. Therefore, the lack of statistically significant findings in the Moderna subgroup may reflect limited power rather than a true absence of effect, and these results should be interpreted with caution. Additionally, survivorship bias could have skewed the results as perhaps survivors in the unvaccinated cohort who survived were healthier than their counterparts in the vaccinated cohort, who were aided in surviving by the vaccination series. Cases who were fully vaccinated at least two months before the diagnosis of AIS were included in the exposure cohort, but besides that the time between vaccination and AIS was not accounted for. Therefore, the effect of recent versus remote vaccination on the outcomes of interest was not measured. Additionally, the analysis did not distinguish between those cases experiencing first versus recurrent COVID-19 infection, which could have also been a confounder in elucidating the relationship between infection, AIS, and the outcomes of interest.

Despite these limitations, this study provides insights into the relationship between vaccination against COVID-19 and outcomes in COVID-19-associated AIS cases. Future work should focus on better understanding the head-to-head comparison of Pfizer vs. Moderna or other vaccinations, as well as better understanding the mechanism through which COVID-19 vaccination reduces the risk of severe AIS sequelae in the setting of COVID-19.

In conclusion, among patients with COVID-19-associated AIS, those who had received prior vaccination for COVID-19 had lower risk of mortality and complications for intracranial hemorrhage, venous thromboembolism and acute myocardial infarction compared to those who did not have prior vaccination for COVID-19. Vaccination against COVID-19 should be encouraged, particularly in the population of patients who are at higher risk of having a stroke. Even if vaccination against COVID-19 does not eliminate the risk of infection, the findings here demonstrate that vaccination is associated with a significant reduction in morbidity and mortality in the event of COVID-19-associated AIS.

Methods

Study design and data source

This is a retrospective cohort study utilizing TriNetX, a global federated health research network providing access to electronic health records (EHR), including diagnoses, procedures, medications, laboratory values, and genomic information. We utilized the COVID-19 Research Network in TriNetX, which contains EHR data for over 121 million unique patients in 88 healthcare organizations from ten countries. TriNetX only uses aggregated counts and statistical summaries of de-identified information, so protected health information and personal data are not made available to users of the platform. Therefore, Institutional Review Board approval was not required for this study. The codes for demographics, diagnoses, procedures, and medication prescriptions used in this study are available in Supplementary Table S1.

Study population

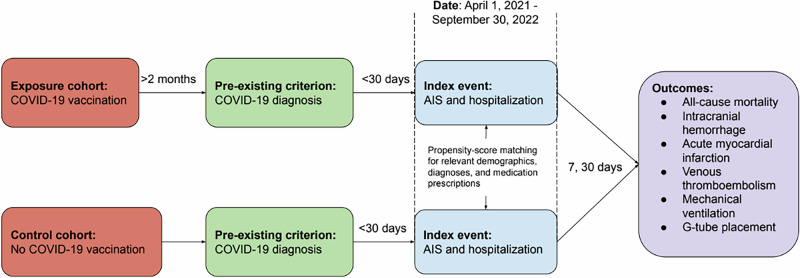

Adult patients were included in the study if they were hospitalized for AIS between April 1, 2021 and September 30, 2022 and had a diagnosis of COVID-19 up to 30 days before the diagnosis of AIS (Fig. 2). The TriNetX codes used to identify COVID-19 diagnosis, AIS, and hospitalization are available in Supplementary Table S1. Patients were excluded from the study if (1) hospitalization for AIS occurred before April 1, 2021 or after September 30, 2022 or (2) there was no COVID-19 diagnosis within 30 days before hospitalization for AIS.

Fig. 2. Study design.

Patients hospitalized with a diagnosis of AIS and who had COVID-19 infection in the preceding one month were categorized into two groups based on COVID-19 vaccination status. They were compared at 7 and 30 days after admission for the outcomes of interest listed.

Patients were divided into two cohorts: the vaccinated (exposure) cohort and the unvaccinated (control) cohort. Patients in the vaccinated cohort had received two doses of Pfizer (BNT162b2), two doses of Moderna (mRNA-127), two doses of Astrazeneca (ChAdOx1) or one dose of Johnson & Johnson (Ad26.COV2.S) COVID-19 vaccine at least two months before the diagnosis of AIS (Supplementary Table S2). The unvaccinated group included patients who did not receive any of the above four COVID-19 vaccines based on documentation in their EHRs. Patients in these cohorts were identified for analysis on May 9, 2023. At the time of the search, 85 health care organizations that met the study criteria were included in the study. All patients in the vaccinated cohort were from the United States. In the unvaccinated cohort, 95% of patients were from the United States and 5% were from other countries. TriNetX only reports the percentage of patients from the United States versus other countries without specifying which other countries are represented in the cohorts. Among all AIS admissions between April 1, 2021 and September 20, 2022 in the database, 39% had a documented COVID-19 infection in the 30 days prior to admission.

Outcomes

Outcomes were assessed at 7 and 30 days after the diagnosis of AIS (Fig. 2). All-cause mortality was the primary outcome, while the following common AIS complications were secondary outcomes: intracranial hemorrhage (intracerebral hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage), acute myocardial infarction, venous thromboembolism (pulmonary embolism and other venous embolism and thrombosis), mechanical ventilation, and G-tube placement15.

Statistical analysis

All calculations were performed on TriNetX using its built-in analytics function. Chi-squared tests were used for categorical variables and an independent samples t tests for continuous variables. A 1:1 propensity score matching was performed between the exposure and control cohorts for the following variables that were considered to potentially influence the outcomes studied: age, sex (male / female), race (White, Black, Asian, unknown), Hispanic ethnicity, medical history (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation / flutter, overweight and obesity, chronic kidney disease, chronic lower respiratory diseases, tobacco use, ischemic stroke, non-traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage, non-traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage, acute myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism and other venous embolism and thrombosis) and medications (aspirin, clopidogrel, warfarin, apixaban, rivaroxaban and dabigatran). Age was considered as a continuous variable and all other above variables were included as categorical variables for propensity score matching. The TriNetX platform uses nearest-neighbor matching with a tolerance level of 0.01 and a difference between propensity scores ≤ 0.1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to estimate the probability of survival at the end of 7- and 30-day timepoint after AIS. The matched cohorts were compared by Cox proportional hazard analysis for secondary outcomes and reported with hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for comparison of time-to-event rates. To assess the risk of secondary outcomes (intracranial hemorrhage, acute myocardial infarction, venous thromboembolism, mechanical ventilation, and G-tube placement), patients with prior history of the same diagnosis or procedure when admitted for index AIS were excluded to ensure only true occurrences, and not follow-up for prior occurrences, were analyzed.

Two subgroup analyses were performed. First, patients who received the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccination (Pfizer vaccine cohort) were compared to the control cohort, as were patients who received the Moderna COVID-19 vaccination (Moderna vaccine cohort). These two vaccination subgroups were chosen for analysis as they accounted for the majority of patients in the exposure cohort (69% and 28%, respectively). Second, the original analyses were divided temporally into two parts based on the dominant COVID-19 variant: patients admitted with AIS between April 1, 2021 to November 30, 2021 (Part 1) when the Delta variant was dominant and patients admitted with AIS between December 1, 2021 to September 30, 2022 (Part 2) when the Omicron variant was dominant (Supplementary Table S3) 16,17. In all subgroup analyses, propensity-score matching and Cox proportional hazard analyses were conducted between the exposure (vaccinated) and control (unvaccinated) cohorts to generate HR and 95% CI as outlined above.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

N.N. conceived, designed, and supervised the study; contributed to interpretation of results and manuscript preparation. N.E. conducted the study and drafted the manuscript. M.P.G. contributed to study design, result interpretation and manuscript preparation. S.O., R.R., and R.X. contributed to result interpretation, reviewing and editing the manuscript for intelluctual content. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Data availability

All relevant data analyzed for this study using the online TriNetX Analytics platform are reported in this article and Supplemental Material. Access to TriNetX research network requires a subscription / sharing agreement with TriNetX. Relevant de-identified aggregated data analyzed from TriNetX are available from the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Nader El Seblani, Maria P. Gorenflo.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41541-025-01158-1.

References

- 1.Qureshi, A. I. et al. Acute ischemic stroke and COVID-19: an analysis of 27,676 patients. Stroke52, 905–912 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nannoni, S., de Groot, R., Bell, S. & Markus, H. S. Stroke in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J. Stroke16, 137–149 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison, S. L., Fazio-Eynullayeva, E., Lane, D. A., Underhill, P. & Lip, G. Y. H. Higher mortality of ischaemic stroke patients hospitalized with COVID-19 compared to historical controls. Cerebrovasc. Dis.50, 326–331 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marti-Fabregas, J. et al. Impact of COVID-19 infection on the outcome of patients with ischemic stroke. Stroke52, 3908–3917 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization COVID-19 vaccination, World data, https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/vaccines.

- 6.Thompson, M. G. et al. Effectiveness of Covid-19 vaccines in ambulatory and inpatient care settings. N. Engl. J. Med385, 1355–1371 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim, Y. E., Huh, K., Park, Y. J., Peck, K. R. & Jung, J. Association between vaccination and acute myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke after COVID-19 infection. JAMA328, 887–889 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El Naamani, K. et al. The effect of COVID-19 vaccines on stroke outcomes: a single-center study. World Neurosurg.170, 834–839 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rizzo, P. A. et al. COVID-19 vaccination is associated with a better outcome in acute ischemic stroke patients: a retrospective observational study. J. Clin. Med.11, 6878 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Abou-Ismail, M. Y., Diamond, A., Kapoor, S., Arafah, Y. & Nayak, L. The hypercoagulable state in COVID-19: incidence, pathophysiology, and management. Thromb. Res. 194, 101–115 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ioannou, G. N., Locke, E. R., Green, P. K. & Berry, K. Comparison of Moderna versus Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine outcomes: a target trial emulation study in the U.S. Veterans Affairs healthcare system. EClinicalMedicine45, 101326 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Islam, N., Sheils, N. E., Jarvis, M. S. & Cohen, K. Comparative effectiveness over time of the mRNA-1273 (Moderna) vaccine and the BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) vaccine. Nat. Commun.13, 2377 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stamenkovic, M. et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with acute ischemic stroke previously vaccinated against COVID-19. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis.31, 106483 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stefanou, M. I. et al. Acute arterial ischemic stroke following COVID-19 vaccination: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology99, e1465–e1474 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Behrouz, R. & Birnbaum, L. A. Complications of Acute Stroke: An Introduction (Springer, 2019).

- 16.Antonelli, M., Pujol, J. C., Spector, T. D., Ourselin, S. & Steves, C. J. Risk of long COVID associated with delta versus omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2. Lancet399, 2263–2264 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang, C. & Han, J. Will the COVID-19 pandemic end with the delta and omicron variants? Environ. Chem. Lett.20, 2215–2225 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data analyzed for this study using the online TriNetX Analytics platform are reported in this article and Supplemental Material. Access to TriNetX research network requires a subscription / sharing agreement with TriNetX. Relevant de-identified aggregated data analyzed from TriNetX are available from the authors.