Abstract

The increasing prevalence of chronic respiratory diseases among older adults significantly affects morbidity and mortality rates. Hospitalizations from exacerbations and acute respiratory infections (ARIs) pose a substantial burden on healthcare systems. This study aimed to estimate the nationwide incidence of such hospitalizations among older adults with chronic respiratory diseases, identify risk factors, and assess outcomes like intensive care needs and mortality. Utilizing data from the National Health Insurance Service senior cohort (2016–2017), we analyzed patients aged 60 and above diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, or bronchiectasis. We followed hospitalization rates over two years, employing Cox regression models to identify predictors for hospitalizations. Out of 117,793 patients, 16,024 (13.6%) patients had overlapping respiratory diseases with COPD, asthma and/or bronchiectasis. Of the total population, 9.6% were hospitalized due to exacerbations or ARIs, showing an incidence rate of 10.6 per 100 patient-years. Notably, patients with multiple respiratory diseases had hospitalization rates over 20%. Of the 24,186 hospitalizations, 6.5% necessitated intensive care, and 2.2% were fatal. Increased risk of hospitalization was associated with being 85 or older, having multiple respiratory conditions, and taking certain medications such as antipsychotics and anti-dementia drugs. This study reveals a notable rate of hospitalization due to exacerbations or ARIs among older adults with chronic respiratory diseases, with age, multiple conditions, and specific medications being major risk factors. The findings underscore the need for targeted preventive strategies and careful management of this vulnerable population.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-07197-x.

Keywords: Acute respiratory infections, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Asthma, Bronchiectasis, Hospitalization, Older adult

Subject terms: Risk factors, Geriatrics, Health services, Respiratory tract diseases

Introduction

Chronic respiratory diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, and bronchiectasis, are characterized by airway inflammation and airflow limitation. These diseases are increasingly prevalent globally and rank among the leading causes of mortality1. The reported prevalence of these conditions varies across countries, with 5–16% of individuals aged 40 years and older suffering from COPD internationally1. This figure increases from 20 to 30% in patients over the age of 70 years2. The disease burden of chronic respiratory conditions increases dramatically with age. The mortality rate of patients with COPD is almost three times higher in older adults than in those aged 65 or younger 3. Similarly, hospitalization rate per 10,000 population was much higher in older patients than aged 45–64 (30.1 for 45–64 years vs. 121.3 for 65 years or older)4. The prevalence of diagnosed asthma is lower than that of COPD, estimated to affect 4–10% of older populations2. However, in older populations, there is a significant overlap between asthma and COPD, known as asthma-COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS)5. Patients with ACOS experience more frequent exacerbations and higher healthcare utilization compared with those with each disease separately6,7.

Although bronchiectasis has been considered a rare disease in developed countries, it remains prevalent in Asia, with an estimated prevalence of 1.2% in older subjects8. Bronchiectasis in older adults is characterized by greater disease severity and worse quality of life compared to younger adults9. Also, the mortality rates are higher in older patients9. While the prevalence of bronchiectasis is lower than that of COPD or asthma, its disease burden has been suggested to be comparable to that of COPD8. Among the patients with COPD, about 29.5% have bronchiectasis10. The coexistence of bronchiectasis with COPD increased severe exacerbation requiring hospitalization and intensive care unit (ICU) admission (14.1% vs. 10.4% in COPD-only patients)11. Bronchiectasis is also one of the most common comorbidities associated with asthma, with higher exacerbation rates observed in patients with both diseases12. The overlap of these three diseases is expected to be associated with increased clinical severity and mortality.

The primary reason for hospitalization in patients with COPD or asthma is acute exacerbation, which involves a sudden deterioration of symptoms beyond the expected daily variation, requiring additional healthcare services13,14. Acute exacerbations are often triggered by acute respiratory viral and bacterial infections. Recent studies have indicated that a wide variety of respiratory viruses, specifically immune responses to respiratory viral infections, are related to the severity of exacerbations of both diseases15. The coinfection with both viruses and bacteria is associated with a more severe prognosis in these patients. Severe exacerbations and acute respiratory infections (ARIs) constitute the primary causes of morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic inflammatory airway diseases, leading to a significant health and economic burden globally16. Therefore, understanding the prevalence and related factors of hospitalization due to ARIs and exacerbations is crucial for developing risk predictive models and targeted preventive strategies. While some studies have investigated the prevalence and risk factors of exacerbations, pneumonia, or acute viral infections in individual disease entities17,18, limited research has explored these clinical outcomes in patients with chronic inflammatory airway diseases, including those with overlapping conditions.

Therefore, we aimed to estimate the nationwide incidence of hospitalization outcomes due to exacerbations or ARIs, including pneumonia and influenza, in older patients with chronic inflammatory airway diseases. Given the significant disease burden in this population, we focused on older adult patients. We also identified factors related to these hospitalization outcomes, encompassing comorbidities and non-respiratory medications.

Methods

Study design, settings, and population

This study is a retrospective observational cohort study using national claims data. We used the National Health Insurance Service-Senior Cohort (NHIS-SC), which is a nationwide deidentified database comprising 18 years of cumulative records (2002–2019) of randomly sampled older adults aged 60 to 80 years. The cohort was initially established with data of 2008 and includes 511,953 individuals. From 2009 to 2018, 8% of adults who turned 60 each year were added to the cohort to account for annual replacements.

We included the patients aged 60 years and older who visited the healthcare facilities with a main diagnosis code of COPD (J41–J44), asthma (J45–J46), or bronchiectasis (J47) during 2016–2017. For our study, we defined the first visit date of the healthcare facility with the main diagnosis of target disease during the study period as the entry date, and we followed up with the patients for a period of 2 years from the entry date. The detailed codes for diagnosis are provided below.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University - approval: IRB number E2303/004 001. The requirement for informed consent to participate was waived by the Seoul National University Institutional Review Board due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Outcome definition

The primary outcome of the study was to determine the incidence of specific events of interest over 2 years. These events included hospitalization due to exacerbation of COPD, asthma, or bronchiectasis, as well as ARI, including influenza and pneumonia. The incidence rate was measured both overall and separately for each specified condition. A hospitalization event was considered relevant if the primary diagnosis was one of the aforementioned conditions and the hospital stay lasted at least two consecutive days. Additionally, the use of a neuraminidase inhibitor during hospitalization was also considered an indicator of influenza infection.

To identify exacerbation of chronic airway disease, the following international classification of diseases (ICD) 10 codes were used: chronic bronchitis (J41, J42), emphysema (J43), other COPD (J44), asthma (J45, J46), and bronchiectasis (J47). ARIs were categorized using influenza (J09–J11), viral pneumonia (J12), pneumonia due to Streptococcus pneumoniae (J13), Haemophilus influenzae (J14), or Mycoplasma pneumoniae (J157), and Chlamydia pneumoniae (J160). Other pneumonia cases were identified using J15–J18 (excluding J157 and J160). Additionally, acute pharyngitis or tonsillitis due to other specified organisms (J028, J038) and acute bronchitis or bronchiolitis due to infection (J200, J201, J204, J205, J206, J208, J210, J211, J218) were included. Due to anonymization policies, some of these conditions were grouped under masked J codes. We also evaluated the outcome of hospitalization, including intensive care admission rates and hospital mortality.

Predictive factors for hospitalization

Taking into account the characteristics of the claims database, various factors were considered as potential predictors for hospitalization. These included demographic information, comorbid diseases, Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), history of previous hospitalizations, and pharmacotherapeutic variables. Comorbidities such as diabetes (E10–E14), stroke (G45, I60–I64), heart failure (I110, I130, I255, I420, I425–I429, I43, I50, P290), myocardial infarction (I21–I22, I252), arrhythmia (I44–I49), rheumatoid disease (M05–M06, M315, M32-M34, M351, M353, M360), osteoporosis (M800–M809, M810–M819), depression (F313–316, F319–F339, F341–F39, F412, F432), and dementia (F00–F05, F061, F068, G132, G138, G30, G310–G312, G94, R418) were identified using specific diagnostic codes claimed during the year preceding the study entry date. Prior episodes of exacerbation and ARIs were determined using the same outcome definition within the year before the entry date.

Pharmacotherapeutic variables were assessed based on the World Health Organization (WHO) anatomic therapeutic classification (ATC) system, specifically focusing on drugs indicated for obstructive airway diseases (R03). This included various inhalants, systemic adrenergic agents, leukotriene receptor antagonists, xanthines, and phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) inhibitors (roflumilast) with usage considered within one month prior to the entry date. We assumed a 30-day duration for one canister of maintenance therapy inhalers and a 90-day use period for short-acting bronchodilators, excluding nebulization formulation. Additionally, the use of systemic corticosteroids (H02AB), chronic antibiotic therapy (defined as being prescribed more than 2 weeks), psycholeptics (antipsychotics N05A, anxiolytics N05B, hypnotics and sedatives N05C), psychoanaleptics (antidepressants N06A, psychostimulants N06B, anti-dementia N06D), beta-blockers (categorized as cardio-selective C07AB, cardio-nonselective C07AA) and alpha and beta blockers (C07AG), and proton pump inhibitors was also screened.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics of the study population and the incidence rate of the outcome were presented using descriptive statistics. To account for the dynamic nature of pharmacotherapeutic factors, these were treated as time-dependent variables and assessed at fixed three-month intervals. This approach allowed us for capturing changes in medication usage over time and assessing their potential impact on the outcome. All other covariates were considered to be time-independent.

Potential confounding variables such as age, sex, CCI, diabetes, heart failure, myocardial infarction, stroke, rheumatic arthritis, and dementia were adjusted for in the analysis. Time-varying covariates Cox regression models were used to estimate the association between predictive factors and the risk of the first occurrence of outcomes. Hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data management and statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide software version 7.1.

Results

Characteristics of patients

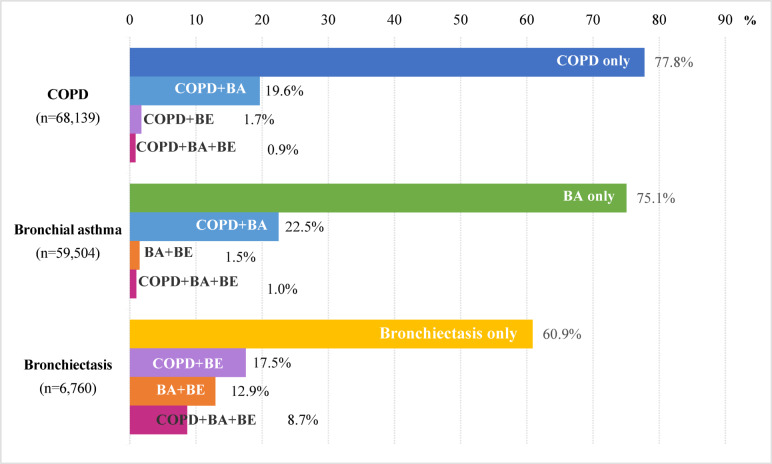

In this senior cohort database, a total of 976,037 patients utilized healthcare facilities at least once during 2016–2017. Of these, 117,793 (12.1%) patients aged 60 years or older with a primary diagnosis of COPD (N = 68,139, 7.0%), asthma (N = 59,504, 6.1%), or bronchiectasis (N = 6,760, 0.7%) were included in our analysis (Fig. 1). The mean age was 71.2 years, with 24.4% in the 60–64 age group and 16.6% aged 80 or above (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Proportions of COPD, bronchial asthma, bronchiectasis, and overlap diseases of the study population. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BA, bronchial asthma; BE, bronchiectasis.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics, medication use, and the incidence of outcome by subcategory in the study population.

| Total (N = 117,793) | Hospitalization d/t ARI* (N = 7,544) |

Hospitalization d/t exacerbation* (N = 5,227) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 71.2 ± 7.5 | 75.2 ± 7.7 | 75.2 ± 7.7 |

| 60–64 | 28,754 (24.4) | 941 (3.3) | 688 (2.4) |

| 65–69 | 24,558 (20.9) | 943 (3.8) | 693 (2.8) |

| 70–74 | 23,313 (19.8) | 1,283 (5.5) | 899 (3.9) |

| 75–79 | 21,668 (18.4) | 1,747 (8.1) | 1,228 (5.7) |

| 80–84 | 14,014 (11.9) | 1,715 (12.2) | 1,136 (8.9) |

| 85+ | 5,486 (4.7) | 915 (16.7) | 583 (10.6) |

| Sex, Male | 52,842 (44.9) | 3,861 (7.3) | 2,749 (5.2) |

| Sex, Female | 64,951 (55.1) | 3,683 (5.7) | 2,478 (3.8) |

| Diagnosis§ | |||

| COPD | 52,989 (45.0) | 3,012 (5.7) | 1,571 (3.0) |

| Bronchial asthma | 44,664 (37.9) | 2,162 (4.8) | 1,159 (2.6) |

| Bronchiectasis | 4,116 (3.5) | 290 (7.1) | 145 (3.5) |

| COPD with BA | 13,380 (11.4) | 1,638 (12.2) | 1,946 (14.5) |

| COPD with Bronchiectasis | 1,184 (1.0) | 208 (17.6) | 163 (13.8) |

| Bronchiectasis with BA | 874 (0.7) | 104 (11.9) | 115 (13.2) |

| COPD, BA, Bronchiectasis | 586 (0.5) | 130 (22.2) | 128 (21.8) |

| Time from first diagnosis | |||

| ≤ 1 year | 48,934 (41.5) | 2,444 (5.0) | 994 (2.0) |

| 1–3 years | 11,362 (9.6) | 665 (5.9) | 402 (3.5) |

| 3–5 years | 12,343 (10.5) | 830 (6.7) | 501 (4.1) |

| > 5 years | 45,154 (38.3) | 3,605 (8.0) | 2,994 (6.7) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | |||

| 1–2 | 54,729 (46.5) | 2,553 (4.7) | 1,831 (3.4) |

| 3–4 | 39,011 (33.1) | 2,598 (6.7) | 1,820 (4.7) |

| 5–6 | 16,768 (14.2) | 1,528 (9.1) | 1,008 (6.0) |

| 7 + | 7,285 (6.2) | 865 (11.9) | 568 (7.8) |

| Co-morbid condition | |||

| Hypertension | 68,782 (58.4) | 4,950 (7.2) | 3,377 (4.9) |

| Type 2 diabetes | 41,850 (35.8) | 3,256 (7.8) | 2,193 (5.2) |

| Type 1 diabetes | 1,808 (1.5) | 169 (9.3) | 112 (6.2) |

| Heart failure | 13,358 (11.3) | 1,513 (11.3) | 1,191 (8.9) |

| Arrhythmia | 8,482 (7.2) | 882 (10.4) | 606 (7.1) |

| Myocardial infarction | 3,222 (2.7) | 348 (10.8) | 264 (8.2) |

| Stroke | 11,609 (9.9) | 1,217 (10.5) | 695 (6.0) |

| Osteoporosis | 28,230 (24.0) | 2,143 (7.6) | 1,491 (5.3) |

| Rheumatoid disease | 7,711 (6.6) | 581 (7.5) | 363 (4.7) |

| Cancer | 11,684 (9.9) | 1,042 (8.9) | 691 (5.9) |

| Depression | 20,569 (17.5) | 1,897 (9.2) | 1,328 (6.5) |

| Dementia | 7,657 (6.5) | 923 (12.1) | 624 (8.2) |

| Prior acute respiratory infection | 3,490 (3.0) | 968 (27.7) | 730 (20.9) |

| Prior exacerbation | 1,803 (1.5) | 483 (26.8) | 834 (46.3) |

| Medication use at entry | |||

| Inhaler use | 27,702 (23.5) | 2,708 (9.8) | 2,907 (10.5) |

| Short-acting bronchodilator only | 4,817 (4.1) | 409 (8.5) | 387 (8.0) |

| SABA only | 4,093 (3.5) | 295 (7.2) | 273 (6.7) |

| SAMA only | 218 (0.2) | 27 (12.4) | 19 (8.7) |

| SABA + SAMA | 501 (0.4) | 87 (17.4) | 95 (19.0) |

| Maintenance inhalation | |||

| Long-acting bronchodilators | 23,636 (20.1) | 2,237 (9.5) | 2,395 (10.1) |

| LB monotherapy | 9,284 (7.9) | 795 (8.6) | 700 (7.5) |

| LABA, monotherapy | 4,997 (4.2) | 335 (6.7) | 234 (4.7) |

| LAMA, monotherapy | 2,416 (2.1) | 252 (10.4) | 245 (10.1) |

| LABA + LAMA | 1,871 (1.6) | 208 (11.1) | 221 (11.8) |

| ICS, in total | 18,092 (15.4) | 1,776 (9.8) | 1,992 (11.0) |

| ICS Monotherapy | 3,740 (3.2) | 312 (8.3) | 297 (5.7) |

| ICS + LB | 14,352 (12.2) | 1,464 (10.2) | 1,695 (11.8) |

| ICS + single LB | 14,146 (12.0) | 1,417 (10.0) | 1,629 (11.5) |

| ICS + LABA + LAMA | 206 (0.2) | 47 (22.8) | 66 (32.0) |

| Corticosteroids, systemic† | 30,489 (25.9) | 2,138 (7.0) | 1,694 (5.6) |

| Methylxanthines | 52,538 (44.6) | 4,526 (8.6) | 3,848 (7.3) |

| Doxofylline | 16,428 (13.9) | 1,595 (9.7) | 1,451 (8.8) |

| Aminophylline, theophylline | 15,385 (13.1) | 1,380 (9.0) | 1,257 (8.2) |

| Other xanthines‡ | 20,719 (17.6) | 1,551 (7.5) | 1,140 (5.5) |

| Bronchodilator, systemic | 44,107 (37.4) | 2,925 (6.6) | 2,102 (4.8) |

| Leukotriene modifiers | 25,137 (21.3) | 2,006 (8.0) | 1,793 (7.1) |

| PDE-4 inhibitors | 201 (0.2) | 46 (22.9) | 71 (35.3) |

| Antibiotics, chronic use | 7,658 (6.5) | 862 (6.5) | 699 (9.1) |

| Antipsychotics | 2,804 (2.4) | 478 (17.1) | 297 (10.6) |

| Anxiolytics | 24,821 (21.1) | 2,059 (8.3) | 1,470 (5.9) |

| Hypnotics and sedatives | 8,996 (7.6) | 885 (9.8) | 694 (7.7) |

| Antidepressants | 12,350 (10.5) | 1,160 (9.4) | 847 (6.9) |

| Stimulants | 3,973 (3.4) | 421 (10.6) | 237 (6.0) |

| Anti-dementia | 9,233 (7.8) | 1,099 (11.9) | 684 (7.4) |

| Opioids | 36,863 (31.3) | 2,706 (7.3) | 1,826 (5.0) |

| Non-tramadol opioid only | 2,261 (4.1) | 239 (10.6) | 196 (8.7) |

| Tramadol | 34,592 (29.4) | 2,467 (7.1) | 1,580 (4.6) |

| Beta-blockers | 15,700 (13.3) | 1,237 (7.9) | 753 (4.8) |

| Selective beta-blockers | 7,679 (6.5) | 558 (7.3) | 321 (4.2) |

| Alpha and beta blockers | 5,331 (4.5) | 405 (7.6) | 249 (4.7) |

| Non-selective beta blockers | 2,690 (2.3) | 274 (10.2) | 183 (6.8) |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 25,991 (22.1) | 2,046 (7.9) | 1,528 (5.9) |

*Figure in parentheses () represents the percentage out of row total, which means the incidence of subcategory.

§Based on the diagnosis code during 2016–2017.

†Injectable formulations were excluded.

‡Other xanthines include acebrophylline, theobromine, bamifylline, proxyphylline, and diprophylline.

d/t, due to; ARI, acute respiratory infection; BA, bronchial asthma; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting beta agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; LB, long-acting bronchodilators; PDE-4, phosphodiesterase-4; SABA, short-acting beta agonist; SAMA, short-acting muscarinic antagonist.

In terms of disease-specific demographics, 57.8% were diagnosed with COPD, among whom 19.6% had a concurrent asthma diagnosis, 1.7% with bronchiectasis, and 0.9% with both. Patients diagnosed with asthma comprised 50.5% of the population, with 22.4% also having COPD, 1.4% bronchiectasis, and 1.0% both conditions. Bronchiectasis was diagnosed in 5.7% of the study population, with approximately 40% of these cases co-diagnosed with COPD or asthma.

Regarding comorbidities at baseline, the prevalence rates were 35.8% for diabetes mellitus, 11.3% for heart failure, 9.9% for stroke, and 6.5% for dementia. In the year prior to study entry, 3.0% of patients had been hospitalized for ARIs of interest and 1.5% for exacerbation of respiratory disease.

Concerning pharmacotherapy, 23.5% of the study population were prescribed inhalers at entry. Inhaled long-acting bronchodilator (ILB) and inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) were prescribed to 20.1% and 15.4%, respectively, and a combination of ICS with ILB to 12.2%. Short-acting bronchodilators as the single therapy were used by 4.2%. A notable 25.9% had been prescribed oral systemic corticosteroids in the month preceding the entry date. Xanthine derivatives were prescribed to 52,538 patients (44.6%), including 15,385 patients (13.1%) on theophylline or aminophylline. Systemic bronchodilators, leukotriene modifiers, and PDE-4 inhibitors (roflumilast) were prescribed to 37.4%, 21.3%, and 0.2% of the patients, respectively.

Incidence of hospitalization due to exacerbation or acute respiratory infection

Over the 2-year follow-up period, 11,334 patients (9.6%) experienced 24,186 hospitalizations (10.6 per 100 patient-year) due to exacerbation or ARIs (Table 2). Among them, hospitalizations due to ARIs were recorded in 7,544 (6.4%) patients, totaling 11,799 cases (5.2 per 100 patient-year). The incidence of ARIs was higher in older groups, peaking at 16.7% in those aged 85 years or older. Patients with bronchiectasis exhibited the highest incidence of ARI (7.1%) with even higher in those with multiple chronic respiratory diseases – up to 22.2% in patients with all three studied diseases. The incidence of ARI also correlated with disease duration and comorbidity index, notably higher in patients with a history of ARI or exacerbation in the past year (Table 1).

Table 2.

Outcomes of hospitalizations due to exacerbations or acute respiratory infection.

| Main reason of admission | Episode (N = 24,186) N (%) |

ICU care* (N = 1,579) N (%) |

Mortality* (N = 522) N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall exacerbations | 12,387 (51.2) | 461 (3.7) | 124 (1.0) |

| COPD | 7,901 (32.7) | 348 (4.4) | 105 (1.3) |

| Asthma | 3,808 (15.7) | 89 (2.3) | 16 (0.4) |

| Bronchiectasis | 678 (2.8) | 24 (3.5) | 3 (0.4) |

| Overall acute respiratory infections§ | 11,799 (48.8) | 1,118 (9.5) | 398 (3.4) |

| Pneumonia | 9,902 (40.9) | 1,001 (10.1) | 385 (3.9) |

| Neuraminidase inhibitor use | 1,323 (5.5) | 97 (7.3) | 11 (0.8) |

| Other ARIs belong to masking J code | 574 (2.4) | 20 (3.5) | 2 (0.3) |

§If patients had diagnostic code of ARIs and were prescribed neuraminidase inhibitors during the hospitalization, they were classified as ‘neuraminidase inhibitor use’.

*In the ‘ICU care’ and ‘Mortality’ columns, figure in parentheses () represents the percentage out of row total. and N indicates the number of total number of cases in each category.

ARI, acute respiratory infections; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICU, intensive care unit.

Regarding exacerbations of chronic respiratory disease, there were 12,387 hospitalizations (5.4 per 100 patient-year) in 5,227 (4.4%) patients. The incidence of exacerbations increased with age and was pronounced in patients with overlapping chronic inflammatory respiratory disease, exceeding 20% in those with three conditions. Similar to ARI, the incidence of exacerbations rose with longer disease duration and a higher comorbidity index. Additionally, 46.3% of patients with a prior history of exacerbation experienced hospitalization (Table 1).

Outcome of hospitalizations with exacerbations or ARIs

Of the 24,186 hospitalization episodes, 1,579 cases (6.5%) necessitated ICU admission or mechanical ventilation. Moreover, 522 cases (2.2%) resulted in mortality either during the hospital stay or within 7 days post-discharge. The utilization of ICU or mechanical ventilation was highest in pneumonia admissions (10.1%), followed by cases of confirmed influenza infections treated with neuraminidase inhibitors (7.3%). Around 4% of exacerbation-related hospitalizations required ICU or mechanical ventilation support. Notably, hospital mortality was highest for pneumonia admissions (3.9%), followed by COPD exacerbations (1.3%) (Table 2).

Characteristics of patients hospitalized due to ARIs or exacerbations

Out of the total 24,186 hospitalization cases, 62.3% involved patients aged 75 or older. ICU transfers occurred in 6.5% of cases, and 2.2% ended in mortality. The 70–74 age group was more likely to require ICU care, while the 85 + age group had a 2% mortality rate. Patients aged 60–64 showed a lower likelihood of severe outcomes. Approximately 6% of patients with a history of respiratory infection required ICU care and 2.1% died during the hospitalizations (Table 3).

Table 3.

Outcome of hospitalization episodes by baseline patient characteristics.

| Hospitalization (N = 24,186) N (%) |

ICU care* (N = 1,579) N (%) |

Mortality* (N = 522) N (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| 60–64 | 2,561 (10.6) | 101 (3.9) | 18 (0.7) |

| 65–69 | 2,806 (11.6) | 162 (5.8) | 41 (1.5) |

| 70–74 | 3,756 (15.5) | 280 (7.5) | 55 (1.8) |

| 75–79 | 5,659 (23.4) | 415 (7.3) | 121 (2.1) |

| 80–84 | 5,931 (24.5) | 421 (7.1) | 155 (2.6) |

| 85+ | 3,473 (14.4) | 200 (5.8) | 121 (3.5) |

| Sex, Male | 13,060 (54.0) | 1,017 (7.8) | 341 (2.6) |

| Sex, Female | 11,126 (46.0) | 562 (5.1) | 181 (1.6) |

| Diagnosis at entry | |||

| COPD | 9,502 (39.3) | 716 (7.5) | 280 (3.0) |

| Bronchial asthma | 5,244 (21.7) | 292 (5.6) | 97 (1.9) |

| COPD with BA | 7,096 (29.3) | 451 (6.4) | 113 (1.6) |

| Bronchiectasis | 741 (3.1) | 44 (5.9) | 17 (2.3) |

| COPD with Bronchiectasis | 704 (2.9) | 35 (5.0) | 6 (0.9) |

| Bronchiectasis with BA | 327 (1.4) | 10 (3.1) | 2 (0.6) |

| COPD, BA, Bronchiectasis | 572 (2.4) | 31 (5.4) | 7 (1.2) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | |||

| 1–2 | 8,017 (33.2) | 484 (6.0) | 158 (2.0) |

| 3–4 | 8,429 (34.9) | 561 (6.7) | 174 (2.1) |

| 5–6 | 4,843 (20.0) | 332 (6.9) | 123 (2.5) |

| 7 + | 2,897 (12.0) | 202 (7.0) | 67 (2.3) |

| Co-morbid condition | |||

| Hypertension | 16,020 (66.2) | 1,094 (6.8) | 352 (2.2) |

| Type 2 diabetes | 10,477 (42.3) | 770 (7.3) | 232 (2.2) |

| Type 1 diabetes | 636 (2.6) | 47 (7.4) | 18 (2.8) |

| Heart failure | 5,761 (23.8) | 453 (7.9) | 137 (2.4) |

| Arrhythmia | 3,096 (12.8) | 228 (7.4) | 70 (2.3) |

| Myocardial infarction | 1,367 (5.7) | 77 (5.6) | 29 (2.1) |

| Stroke | 3,657 (15.1) | 239 (6.5) | 100 (2.7) |

| Rheumatoid disease | 1,662 (6.9) | 98 (5.9) | 32 (1.9) |

| Osteoporosis | 6,812 (28.2) | 421 (6.2) | 117 (1.7) |

| Cancer | 3,461 (14.3) | 225 (6.5) | 82 (2.4) |

| Depression | 6,516 (26.9) | 404 (6.2) | 148 (2.3) |

| Dementia | 3,632 (15.0) | 236 (6.5) | 100 (2.8) |

| Time from first diagnosis | |||

| ≤ 1 year | 6,049 (25.0) | 459 (7.6) | 167 (2.8) |

| 1–3 years | 2,124 (8.8) | 98 (4.6) | 44 (2.1) |

| 3–5 years | 2,526 (10.4) | 139 (5.5) | 52 (2.1) |

| > 5 years | 13,487 (55.8) | 883 (6.6) | 259 (1.9) |

| Prior pneumonia/influenza | 4,271 (17.6) | 249 (5.8) | 90 (2.1) |

| Prior exacerbation | 4,546 (18.8) | 233 (5.1) | 60 (1.3) |

*This table presents hospitalization outcomes (ICU care, and hospital death) stratified by baseline patient characteristics. Each row represents a specific patient subgroup, with corresponding outcome rates reported within that subgroup. In the ‘ICU care’ and ‘Hospital death’ columns, figure in parentheses () represents the percentage out of row total. and N indicates the number of total number of cases in each category.

BA, bronchial asthma; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICU, intensive care unit.

Predictors for hospitalization due to exacerbations or acute respiratory infections

Time-dependent Cox regression analysis revealed several significant predictors of hospitalization. Supplementary Table S1 shows the crude hazard ratios (univariable model), and Supplementary Table S2 contains the detailed results of a time-dependent Cox regression analysis (multivariable model). The final Cox model had a Nagelkerke R2 of 0.557. Older age significantly increased hospitalization hazard by more than twice, especially in those aged 80 or older (80–84, aHR = 2.44 and 85+, aHR = 3.28). Females had a lower hazard of hospitalization due to ARI compared to males (aHR = 0.78, 95% CI 0.75–0.82). Patients with both COPD and bronchiectasis showed the highest hazard ratio (aHR = 3.26, 95% CI 2.86–3.71).

Heart failure, myocardial infarction, and dementia were associated with higher hazards of 20%, 11%, and 12%, respectively. Prior acute respiratory infection and exacerbation significantly increased the hazard (aHR = 2.20 and 2.67, respectively).

Using inhaled corticosteroids was associated with an increased hazard of hospitalization, as were systemic corticosteroids and bronchodilators. Xanthines also elevated the hazard by 23–35%. Antipsychotics and anti-dementia drugs significantly increased hospitalization hazard of 1.38, and 1.55, respectively. Non-selective beta-blockers raised the risk by 30%, while beta-blockers with alpha or beta selectivity didn’t (Table 4).

Table 4.

Time-dependent Cox analysis for risk factors of hospitalization due to acute respiratory infection or exacerbation.

| Hospitalization d/t ARI or exacerbation aHR (95% CI) (N = 11,334) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| 60–64 | Ref | |

| 65–69 | 1.04 (0.96–1.13) | 0.3213 |

| 70–74 | 1.31 (1.21–1.41)* | < 0.0001 |

| 75–79 | 1.78 (1.66–1.91)* | < 0.0001 |

| 80–84 | 2.44 (2.27–2.63)* | < 0.0001 |

| 85+ | 3.28 (3.01–3.58)* | < 0.0001 |

| Sex, Male | Ref | |

| Sex, Female | 0.78 (0.75–0.82)* | < 0.0001 |

| Diagnosis* | ||

| Bronchial asthma | Ref | |

| COPD | 1.08 (1.02–1.14)* | 0.0051 |

| Bronchiectasis | 1.59 (1.41–1.79)* | < 0.0001 |

| COPD with BA | 2.29 (2.17–2.42)* | < 0.0001 |

| Bronchiectasis with BA | 2.98 (1.54–3.49)* | < 0.0001 |

| COPD with Bronchiectasis | 3.26 (2.86–3.71)* | < 0.0001 |

| COPD, BA, Bronchiectasis | 3.84 (3.29–4.49)* | < 0.0001 |

| Time from first diagnosis | ||

| ≤ 1 year | Ref | |

| 1–3 years | 1.15 (1.07–1.24)* | 0.0004 |

| 3–5 years | 1.20 (1.11–1.29)* | < 0.0001 |

| > 5 years | 1.44 (1.37–1.51)* | < 0.0001 |

| Co-morbid condition | ||

| Heart failure | 1.20 (1.14–1.27)* | < 0.0001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1.11 (1.01–1.23)* | 0.0297 |

| Stroke | 1.07 (1.01–1.13)* | 0.0328 |

| Type 1 Diabetes | 1.07 (0.93–1.22) | 0.3515 |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) | 0.9795 |

| Dementia | 1.12 (1.05–1.20)* | 0.0007 |

| Rheumatoid disease | 1.00 (0.92–1.08) | 0.9173 |

| Depression | 1.09 (1.04–1.15)* | 0.0010 |

| Osteoporosis | 1.06 (1.01–1.12)* | 0.0117 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | ||

| 1–2 | Ref | |

| 3–4 | 1.11 (1.05–1.17)* | 0.0002 |

| 5–6 | 1.14 (1.07–1.23)* | 0.0003 |

| 7 + | 1.13 (1.03–1.25)* | 0.0093 |

| Prior acute respiratory infection | 2.20 (2.06–2.36)* | < 0.0001 |

| Prior exacerbation | 2.67 (2.47–2.88)* | < 0.0001 |

| Inhaler use | 0.83 (0.57–1.21) | 0.3293 |

| Short-acting bronchodilator only | 1.95 (1.33–2.86)* | 0.0006 |

| Long-acting bronchodilator | ||

| No Long-acting bronchodilator | Ref | |

| LABA, monotherapy | 1.84 (1.31–2.58)* | 0.0005 |

| LAMA, monotherapy | 1.69 (1.12–2.56)* | 0.0135 |

| LABA + LAMA | 1.81 (1.24–2.65)* | 0.0021 |

| ICS | ||

| ICS, not use | Ref | |

| ICS, monotherapy | 2.08 (1.43–3.05)* | 0.0002 |

| ICS + single LB | 1.04 (0.84–1.30) | 0.7191 |

| ICS + LABA + LAMA | 1.47 (1.01–2.13)* | 0.0443 |

| Corticosteroids, systemic† | 1.21 (1.10–1.33)* | < 0.0001 |

| Bronchodilator, systemic | 1.03 (0.95–1.12) | 0.4390 |

| Xanthine | ||

| Theophylline | 1.34 (1.26–1.43)* | < 0.0001 |

| Doxofylline | 1.35 (1.19–1.53)* | < 0.0001 |

| Other xanthines‡ | 1.23 (1.07–1.42)* | 0.0039 |

| Leukotriene modifiers | 1.04 (0.94–1.15) | 0.4829 |

| PDE-4 inhibitors | 1.27 (0.82–1.95) | 0.2858 |

| Antibiotics, chronic use | 1.16 (1.07–1.26)* | 0.0002 |

| Concomitant medications | ||

| Antipsychotics | 1.38 (1.26–1.51)* | < 0.0001 |

| Anti-dementia | 1.55 (1.48–1.61)* | < 0.0001 |

| Hypnotics and sedatives | 1.02 (0.95–1.09) | 0.6183 |

| Stimulant | 1.06 (0.98–1.14) | 0.7922 |

| Anxiolytics | 0.98 (0.93–1.03) | 0.4515 |

| Antidepressants | 1.02 (0.99–1.06) | 0.6921 |

| Opioids, not use | Ref | |

| Non-tramadol opioid only | 1.26 (1.18–1.35)* | < 0.0001 |

| Tramadol | 1.03 (0.99–1.08) | 0.1686 |

| Beta blockers, not use | Ref | |

| Selective beta blockers | 0.99 (0.87–1.13) | 0.8924 |

| Alpha and beta blockers | 1.17 (1.02–1.35)* | 0.0275 |

| Non-selective BB | 1.30 (1.12–1.51)* | 0.0007 |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 1.13 (1.04–1.22)* | 0.0021 |

†Injectable formulations were excluded.

‡Other xanthines include acebrophylline, theobromine, bamifylline, proxyphylline, and diprophylline.

d/t, due to; aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; ARI, acute respiratory infection; BA, bronchial asthma; BB, beta blocker; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting beta agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; LB, long-acting bronchodilators; PDE-4, phosphodiesterase-4.

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed national claims data to estimate the incidence of hospitalization due to exacerbations or ARIs in older patients with overlapping chronic inflammatory diseases. Our findings revealed that 9.6% of patients aged 60 and above with such disease expected at least one hospitalization due to exacerbation or ARI within two years. This incidence was higher in patients who were older, had multiple respiratory diseases, or had a longer duration of disease, consistent with previous studies19. Interestingly, only 23.5% of the study population used inhalers at entry, a figure lower than expected considering inhalers are the main treatment for COPD and asthma, yet aligning with other Korean studies20. Such a low inhaler use rate is due to cultural preferences for oral medications, limited time for patient education, and lack of awareness about reimbursement criteria21. Among the cases of hospitalization due to exacerbation or ARI, approximately 6.5% required ICU care or mechanical ventilation, and 2.2% resulted in death. Direct comparisons should be made with caution, as differences in study populations, follow-up periods, healthcare systems, and hospitalization criteria may affect mortality rates. However, our findings are generally in line with previous research. A study from Spain reported that 2.4% of patients hospitalized with COPD exacerbations died during hospitalization or within one week of discharge22. Similarly, another study found that 4.5% of hospitalized patients with bronchiectasis died during their hospital stay23.

COPD accounted for the most significant proportion of total cases of exacerbations, while bronchiectasis had the lowest proportion. Pneumonia was the predominant ARI cause, comprising more than 80% of cases. Notably, patients aged 75 or older and those with heart failure, showed a greater likelihood of ICU admission and mortality, echoing previous findings on risk factors in the COPD population24.

Our time-varying Cox regression analysis highlighted that older age was strongly associated with the hospitalization risk, which corroborates a South Korean study linking older age with asthma exacerbation risk25. Moreover, our study also demonstrated that patients with concurrent chronic respiratory diseases also have an increased hazard of hospitalization, along with a history of exacerbation raising the risk of ARIs, aligning with previous studies26–30.

Medication usage emerged as a critical factor influencing hospitalization risk. Advanced treatment stages such as the use of long-acting beta agonist (LABA) and long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) combinations indicative of severe disease condition at entry, were associated with an increased risk of hospitalization. However, it is believed that this increased hazard is not due to the medications themselves causing hospitalization but rather because these medications are predominantly used by patients with severe conditions. In contrast, the heightened risk associated with the single therapy of short-acting bronchodilators, typically employed in less severe disease stages, suggests a potential gap in proactive disease management. This scenario implies that patients relying only on these bronchodilators might not be receiving adequate care or might be underestimating their condition’s severity, leading to a worsening of their illness and subsequent hospitalization. Similarly, a stronger likelihood of hospitalization was observed in ICS monotherapy compared to non-users or those in a combination with bronchodilators. This trend can be attributed to higher disease severity and inadequate therapy, respectively. Therefore, based on these results, combination therapies such as LABA + LAMA or ICS + LABA, rather than monotherapies like SABA or ICS only, should be considered to mitigate the risk effectively. Similarly, previous studies reported that the use of high-dose ICS as opposed to combination with bronchodilators may elevate the risk of readmission in patients with COPD and asthmatic pneumonia31,32. In addition, theophylline, a xanthine derivative, was associated with increased risk, aligning with a previous study linking its use with exacerbation33.

Moreover, medications for treating the non-respiratory conditions, such as antipsychotics or anti-dementia drug, were associated with increased hospitalization risks, corroborating earlier research34–36. Previous studies have demonstrated that antipsychotics can induce respiratory suppression and have immunosuppressive effects, potentially leading to exacerbations or respiratory infections37,38. In addition, taking anti-dementia drugs implies that patients have dementia of moderate severity or higher. Therefore, aggravated dementia in older adults can result in adverse outcomes, such as hospitalizations due to exacerbations or respiratory infections39. Beta-blockers (BB) showed varied effects based on receptor selectivity, and this is attributed to the bronchoconstrictive effect of non-selective BB40.

This study evaluated factors related to hospitalization due to ARI or exacerbation in older patients with chronic respiratory diseases, encompassing both comorbidities and non-respiratory medications. In addition, we also assessed the risk associated with hospitalization due to ARI or exacerbation in patients with coexisting chronic respiratory diseases including asthma, COPD, and bronchiectasis, which is significant in the older population—a factor not sufficiently considered in previous studies. While we attempted to capture the impact of overlapping respiratory diseases, our approach was limited by the lack of specific diagnostic codes distinguishing overlap syndromes. As a result, some cases may not have been fully identified, and further research is needed to refine methods for characterizing their clinical impact.

Using nationwide claims data covering the entire South Korean population, our findings offer several novel insights and implications for hospitalization in older adults with chronic respiratory diseases. First, we revealed the incidence of hospitalization due to ARI or exacerbation in patients with overlapping respiratory conditions. Second, our results identified specific medication including non-respiratory medication (e.g., antipsychotics and anti-dementia agents) associated with increased hospitalization hazard. These results are particularly relevant in the context of polypharmacy, which is common in the older population. Our findings can help healthcare providers identify high-risk patients who might benefit from enhanced monitoring and preventive strategies, potentially reducing the risk of subsequent hospitalizations.

However, there are several limitations in this research. Firstly, the nature of claims data may not have reflected accurate diagnoses and precluded the inclusion of detailed clinical information such as pulmonary function tests (like forced expiratory volume), dyspnea grade, or overall symptom burden, which could provide valuable context for understanding disease severity and its relationship to hospitalization risk. Furthermore, the use of ICD codes for identifying diagnoses may have introduced diagnostic misclassification, particularly for conditions like COPD and bronchiectasis, where coding inaccuracies are common. Although we attempted to minimize misclassification, it remains a limitation of our study. Additionally, while ICD-10 code J96 (respiratory failure) is often used to indicate severe exacerbations, it was not included in our primary definition of exacerbation due to its broad classification encompassing various underlying conditions beyond chronic airway diseases. In further studies, if these types of clinical data are utilized, it would help conduct research that stratifies chronic respiratory diseases by clinical severity and symptoms, identifies related risk factors, and examines their relationship with clinical outcome. Nevertheless, we considered respiratory medications as proxies for disease severity. Secondly, among the diseases causing ARIs, influenza is subject to year-to-year variability in respiratory virus circulation. This variability could potentially limit the generalizability of our study findings. Our two-year of follow-up period helped mitigate the impact of year-specific pattern. However, for better generalizability, future research should collect and analyze data across multiple years. Thirdly, anonymization policies limited the identification of specific infectious diseases, constraining our ability to detail ARIs. To mitigate this limitation, we included specific medications prescribed for the infectious disease of interest, aiming to enhance accuracy to the best extent possible. Lastly, future research should expand the age range of the study population. In this study, we focused on the study population aged 60 or older due to the significant disease burden in this older population. However, certain conditions like asthma commonly affect younger patients as well. Therefore, future studies should include a broader age spectrum to provide more comprehensive insights across all age groups.

Conclusions

Our analysis of national claims data estimates the incidence of and identifies both demographic and medication-related risk factors for hospitalization due to ARI and exacerbation in patients with chronic respiratory diseases. These findings underscore the need for further research using detailed clinical data to validate these associations and their potential as risk factors.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- ACOS

Asthma-COPD overlap syndrome

- aHR

Adjusted hazard ratio

- ARI

Acute respiratory infection

- ATC

Anatomic therapeutic classification

- BB

Beta blocker

- CCI

Charlson comorbidity index

- CI

Confidence interval

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- ICD

International classification of diseases

- ICS

Inhaled corticosteroids

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- ILB

Inhaled long-acting bronchodilator

- LABA

Long-acting beta agonist

- LAMA

Long-acting muscarinic antagonist

- NHIS

National Health Insurance Service

- NHIS-SC

National Health Insurance Service Senior Cohort

- PDE-4

Phosphodiesterase-4

- WHO

World Health Organization

Author contributions

H.C. contributed to conceptualization, data analysis, interpretation of data, writing draft and editing. K.J. contributed to conceptualization, interpretation of data, reviewing draft and editing. J.Y.L. contributed to conceptualization, design of the work, data analysis, interpretation of data, writing draft, reviewing, editing and supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT of the Government of Republic of Korea [grant number RS-2024-00334857].

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper. The raw data analyzed in this study comes from the Senior Cohort 2.0 dataset provided by the Korea National Health Insurance Sharing Service (NHIS-SC). The authors did not have any exclusive access rights to the data. Researchers who are interested and qualified can apply for access to the data by contacting the Korea NHIS. The request to access is available at https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr/bd/ay/bdaya001iv.do.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This human study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University-approval: IRB number E2303/004 001. The requirement for informed consent to participate was waived by the Seoul National University Institutional Review Board due to the retrospective nature of the study. Adult participant consent was not required because of the retrospective cohort design, which utilized de-identified claims data.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Kwanghee Jun, Email: culturevo@gnu.ac.kr.

Ju-Yeun Lee, Email: jypharm@snu.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Chen, X. et al. Global, regional, and National burden of chronic respiratory diseases and associated risk factors, 1990–2019: results from the global burden of disease study 2019. Front. Med.10, 1066804. 10.3389/fmed.2023.1066804 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Athanazio, R. Airway disease: similarities and differences between asthma, COPD and bronchiectasis. Clin. (Sao Paulo). 67, 1335–1343. 10.6061/clinics/2012(11)19 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soriano, J. B. et al. Mortality prediction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease comparing the GOLD 2007 and 2011 staging systems: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Respir. Med.3, 443–450 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.May, S. M. & Li, J. T. In Allergy and Asthma Proceedings. 4.

- 5.de Marco, R. et al. The coexistence of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): prevalence and risk factors in young, middle-aged and elderly people from the general population. PLoS One. 8, e62985. 10.1371/journal.pone.0062985 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrecheguren, M., Esquinas, C. & Miravitlles, M. The asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome (ACOS): opportunities and challenges. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med.21, 74–79. 10.1097/mcp.0000000000000118 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braman, S. S. The chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-asthma overlap syndrome. Allergy Asthma Proc.36, 11–18. 10.2500/aap.2015.36.3802 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang, B. et al. The disease burden of bronchiectasis in comparison with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a National database study in Korea. Ann. Transl. Med.7, 770. 10.21037/atm.2019.11.55 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellelli, G. et al. Characterization of bronchiectasis in the elderly. Respir. Med.119, 13–19 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du, Q., Jin, J., Liu, X. & Sun, Y. Bronchiectasis as a comorbidity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 11, e0150532 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim, Y., Kim, K., Rhee, C. K. & Ra, S. W. Increased hospitalizations and economic burden in COPD with bronchiectasis: a nationwide representative study. Sci. Rep.12, 3829. 10.1038/s41598-022-07772-6 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crimi, C., Ferri, S., Campisi, R. & Crimi, N. The link between asthma and bronchiectasis: state of the art. Respir. Int. Rev. Thorac. Dis.99, 463–476. 10.1159/000507228 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agustí, A. et al. Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease 2023 report: GOLD executive summary. Eur. Respir. J.61 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Reddel, H. K. et al. Global initiative for asthma strategy 2021: executive summary and rationale for key changes. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med.205, 17–35 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurai, D., Saraya, T., Ishii, H. & Takizawa, H. Virus-induced exacerbations in asthma and COPD. Front. Microbiol.4, 293. 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00293 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurst, J. R. et al. Understanding the impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations on patient health and quality of life. Eur. J. Intern. Med.73, 1–6. 10.1016/j.ejim.2019.12.014 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartley, B. F. et al. Risk factors for exacerbations and pneumonia in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pooled analysis. Respir. Res.21, 5. 10.1186/s12931-019-1262-0 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hwang, Y. I. et al. History of pneumonia is a strong risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation in South korea: the epidemiologic review and prospective observation of COPD and health in Korea (EPOCH) study. J. Thorac. Dis. 7, 2203 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dhamane, A. D. et al. COPD exacerbation frequency and its association with health care resource utilization and costs. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulmon. Dis. 2609–2618 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Lee, E. G. & Rhee, C. K. Epidemiology, burden, and policy of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in South korea: a narrative review. J. Thorac. Dis.13, 3888–3897. 10.21037/jtd-20-2100 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi, J. Y. et al. Nationwide use of inhaled corticosteroids by South Korean asthma patients: an examination of the health insurance review and service database. J. Thorac. Dis.10, 5405–5413. 10.21037/jtd.2018.08.110 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quintana, J. M. et al. Predictive score for mortality in patients with COPD exacerbations attending hospital emergency departments. BMC Med.12, 1–11 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim, R. K., Tremblay, A., Lu, S. & Somayaji, R. Evaluating hemoptysis hospitalizations among patients with bronchiectasis in the united states: a population-based cohort study. BMC Pulm. Med.21, 1–8 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mannino, D. M. et al. Predictors of rehospitalization and death after a severe exacerbation of COPD. Commentary. Chest. 132 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Kang, H. R. et al. Risk factors of asthma exacerbation based on asthma severity: a nationwide population-based observational study in South Korea. BMJ Open.8, e020825 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mao, B., Yang, J. W., Lu, H. W. & Xu, J. F. Asthma and bronchiectasis exacerbation. Eur. Respir. J.47, 1680–1686 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamauchi, Y. et al. Comparison of in-hospital mortality in patients with COPD, asthma and asthma—COPD overlap exacerbations. Respirology. 20, 940–946 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Müllerová, H., Shukla, A., Hawkins, A. & Quint, J. Risk factors for acute exacerbations of COPD in a primary care population: a retrospective observational cohort study. BMJ Open.4, e006171 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Müllerova, H. et al. Hospitalized exacerbations of COPD: risk factors and outcomes in the ECLIPSE cohort. Chest. 147, 999–1007 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ekström, M., Nwaru, B. I., Wiklund, F., Telg, G. & Janson, C. Risk of rehospitalization and death in patients hospitalized due to asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract.9, 1960–1968.e1964 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lau, A. W., Yam, L. C. & Poon, E. Hospital re-admission in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir. Med.95, 876–884 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim, M. H. et al. Inhaled corticosteroids in asthma and the risk of pneumonia. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res.11, 795–805 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fexer, J. et al. The effects of Theophylline on hospital admissions and exacerbations in COPD patients: audit data from the Bavarian disease management program. Deutsches Ärzteblatt Int.111, 293 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chalitsios, C. V., Fogarty, A. W., McKeever, T. M. & Shaw, D. E. Sedative medications: an avoidable cause of asthma and COPD exacerbations? Lancet Respir. Med.11, e31–e32 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuo, C. W., Yang, S. C., Shih, Y. F., Liao, X. M. & Lin, S. H. Typical antipsychotics is associated with increased risk of severe exacerbation in asthma patients: a nationwide population-based cohort study. BMC Pulm. Med.22, 1–10 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahan, R. J. & Blaszczyk, A. T. COPD exacerbation and cholinesterase therapy in dementia patients. Consultant Pharmacist®. 31, 221–225 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang, M. T. et al. Association between antipsychotic agents and risk of acute respiratory failure in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA Psychiatry. 74, 252–260 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chan, H. Y., Lai, C. L., Lin, Y. C. & Hsu, C. C. Is antipsychotic treatment associated with risk of pneumonia in people with serious mental illness? The roles of severity of psychiatric symptoms and global functioning. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol.39, 434–440. 10.1097/jcp.0000000000001090 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gupta, A., McKeever, T. M., Hutchinson, J. P. & Bolton, C. E. Impact of coexisting dementia on inpatient outcomes for patients admitted with a COPD exacerbation. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulmon. Dis. 535–544 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Huang, Y. L. et al. Impact of selective and nonselective beta-blockers on the risk of severe exacerbations in patients with COPD. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulmon. Dis. 2987–2996 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper. The raw data analyzed in this study comes from the Senior Cohort 2.0 dataset provided by the Korea National Health Insurance Sharing Service (NHIS-SC). The authors did not have any exclusive access rights to the data. Researchers who are interested and qualified can apply for access to the data by contacting the Korea NHIS. The request to access is available at https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr/bd/ay/bdaya001iv.do.