Abstract

Undernutrition is a common consequence of feeding difficulties in children with Cerebral Palsy (CP). Parental perceptions and their Quality-of-Life (QoL) play a role in above concerns. Understanding this link is crucial for designing effective family-centered interventions, in order to overcome the challenges in nutritional and developmental outcomes and to improve emotional and psychological well-being of the caregivers. This study explores the linkage between the nutritional status of children with CP, caregiver perceptions of feeding concerns, and caregiver QoL. An analytical cross-sectional study was conducted in a Sri Lankan tertiary care setting, using an interviewer-administered questionnaire including clinical diagnoses, PedsQL tool and caregiver perceptions. Convenience sampling method was used. Statistical analysis included Pearson chi-square tests and ANOVA. Among 226 participants, 50% of children under 5 had Severe or Moderate Acute Malnutrition (SAM + MAM), and 41.2% aged 5–19 were underweight. Children with severe CP showed higher undernutrition rates. Most caregivers of undernourished children did not find feeding challenging and believed their children consumed adequate calories. Caregivers did not approve of non-oral feeding methods. Caregiver QoL was impacted by severity of CP (F = 10.4, p < 0.05), but not the child’s nutritional status (F = 0.58, p > 0.05). Caregiver education and support appear fundamental in improving the nutritional status of children with cerebral palsy.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12887-025-05852-w.

Keywords: Cerebral palsy, Undernutrition, Caregiver perceptions, Caregiver quality of life

Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a group of permanent disorders of the development of movement and posture, causing activity limitation, attributed to non-progressive disturbances that occurred in the developing foetal or infant brain [1]. CP affects approximately 2 in 1,000 live births each year [2]. Undernutrition is common among children with CP, especially among those with low Gross Motor Functional Classification System (GMFCS) [3–5]. Children with CP, particularly those with spastic CP, require more calories and energy than typically developing children [6].

These children face feeding problems due to oro-motor dysfunction, which may not be perceived correctly by the caregivers [7, 8]. Caregiver perceptions of oro-motor dysfunction in children with cerebral palsy are shaped by limited awareness, cultural beliefs, and emotional influences [8]. These challenges are frequently misinterpreted as behavioural problems or accepted as typical characteristics of cerebral palsy. A regional study reported that the majority of parents who perceived their child’s feeding to be adequate were, in fact, caring for children with poor nutritional status and severe malnutrition [7].

Caring for these children is challenging, especially when feeding difficulties lead to prolonged and stressful mealtimes [9, 10], taking a toll on the caregiver and affecting the child’s overall health as well as nutritional status [11]. Children with CP and their caregivers face difficulties that impact their quality of life (QoL) [12–14]. Literature reveals that the QoL for parents and caregivers of children with CP is generally low [15]. Difficulty in feeding itself is a significant burden to the caregiver [16]. Greater the feeding difficulty poorer the quality of life of the carer, as feeding is a stressful experience [17].

Sri Lanka is a lower-middle-income country where the public health sector delivers the majority of healthcare services. However, rehabilitation services for children with cerebral palsy (CP) remain underdeveloped and are typically limited to physiotherapy, speech therapy, and occupational therapy at major government hospitals. This limited infrastructure presents significant challenges and gaps in the provision of comprehensive care for children with CP, particularly in addressing feeding difficulties and nutritional needs.

Understanding the caregiver’s perception of their illness is crucial for healthcare providers to assess and support their understanding, empowerment, self-care and QoL, and developing effective feeding programs and treatment protocols. Therefore, this study aims to explore the nutritional status of children with CP, their caloric intake, caregiver perceptions of feeding difficulties and caregiver quality of life.

Materials and methods

Study design, period, and setting

This analytical cross-sectional study was conducted over one year, from March 2022 to February 2023, at Teaching Hospital Kurunegala. Located in an urbanized district of the North-western Province of Sri Lanka, Kurunegala is one of the densely populated cities with a significant population diversity. Teaching Hospital Kurunegala, serves a large number of paediatric patients, drawing patients from neighbouring districts and provinces as it is one of the few specialized paediatric neurology centres and paediatric neurology referral points in Sri Lanka.

Participants selection

Children aged 2–18 years, fulfilling the definition of CP and attending the paediatric neurology clinics at Teaching Hospital Kurunegala, were included in this study. Informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of all participants.

Sampling and sample size

All consented patients diagnosed with CP and meeting the inclusion/exclusion criteria were recruited consecutively for the study (n = 226). Inclusion criteria included children between the ages of 2–17 years diagnosed with cerebral palsy. Exclusion criteria included the presence of other significant medical conditions that could independently affect feeding, such as severe congenital anomalies involving the gastrointestinal tract or metabolic disorders, children receiving palliative care and those with incomplete medical records.

Study instrument

A four-sectioned interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to collect data. This included; Section A: Demographic Data, Section B: Clinical characteristics (Etiology, Types of CP & GMFCS), Section C: Parents’ perceptions, Section D: PedsQL and Appendix 1: Food frequency.

The questionnaire (Sections A-C) was originally developed for this study (Annex 1). It was pretested and validated among 20 patients meeting the inclusion criteria (who were excluded from the main study). Length while lying down/ recumbent length was used to measure the height of those who could not stand up. Anthropometric landmarks used for height measurement included the vertex of the head, positioned against a headboard set at a 90-degree angle, and the inferior aspect of the heel. These were compared against national growth standards specified in the local Child Health Development Record (CHDR), based on WHO multi-country growth reference curves to identify malnutrition [18]. Calorie intake was estimated by dietary assessment using serving sizes (Appendix 1). Serving sizes were converted to calorie values and compared with the Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDA) for age and sex, as outlined in the Food-Based Dietary Guidelines (FBDG) of Sri Lanka [19] to identify any calorie deficit, which was defined as an estimated daily energy intake below the recommended level.

Tool

PedsQL family impact module version 2.0 was used by the investigators to assess the caregiver’s quality of life [20]. It consists of 8 scales (Physical functioning, Emotional functioning, Social functioning, Cognitive functioning, Communication, Worry, Daily activities, and Family relationships), each with several questions. Questions were scored from 0 to 4, and for ease of interpretability, items were reverse-scored and linearly transformed to a 0-100 scale (0 = 100, 1 = 75, 2 = 50, 3 = 25, 4 = 0). If more than 50% of items were missing, the scale score was not counted. Individual scale scores were calculated as the mean of the items answered. Total scores were calculated as the sum of all 36 items, divided by 36. Higher scores indicate better functioning. The PedsQL tool was translated into two native languages (Sinhalese and Tamil) according to the PedsQL linguistic validation guideline with forward and backward translations, followed by pre-testing in a small group of caregivers (5 participants who were not included in the study) [21].

Data collection

The principal investigator, who is a paediatrician, collected data through a personal interview and data related to clinical characteristics, and food frequency (Sections A, B and Appendix 1). A paediatric neurologist independently assessed clinical characteristics and the level of disability according to Gross Motor Function Classification System- Expanded and Revised (GMFCS-ER) [22]. Parental perceptions and PedsQL were completed by the caregiver in a private, distraction-free environment to ensure confidentiality.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was completed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 25 (SPSS-25). Normality was determined with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Means were generated for each independent variable and compared with each group using the ANOVA tests. Chi-square tests were used to test the significance of relationships, and p-values < 0.05 were taken as the significance level.

Results

Study population characteristics

Data were collected from 226 children (90.03% response rate). The mean age of the sample was 6.83 ± 4.49, with 48.7% of participants under 5 years and 55.3% male. The majority of children (44.7%) were diagnosed with severe CP (GMFCS level 4–5). On examination, 77.9% were children with spastic CP of which 35.4% and 38.4% were children with diplegic CP and quadriplegic CP respectively as indicated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic factors, GMFCS level and CP classification

| N (Percentage %) | |

|---|---|

| AGE | |

| Under 5 years | 110 (48.7) |

| 5–19 years | 116 (51.3) |

| GENDER | |

| Male | 125 (55.3) |

| Female | 101 (44.7) |

| GMFCS | |

| GMFCS 1 | 33 (14.6) |

| GMFCS 2 | 39 (17.3) |

| GMFCS 3 | 53 (23.5) |

| GMFCS 4 | 42 (18.6) |

| GMFCS 5 | 59 (26.1) |

| PREDOMINANT MOTOR TYPE | |

| Spastic | 176 (77.9) |

| Dystonic | 13 (5.8) |

| Ataxic | 9 (4.0) |

| Mixed | 12 (5.3) |

| Hypotonic | 16 (7.1) |

| LIMB INVOLVEMENT IN SPASTIC CP GROUP | |

| Monoplegia | 20 (11.4) |

| Diplegic | 67 (38.1) |

| Triplegia | 12 (6.8) |

| Quadriplegia | 60 (34.1) |

| Hemiplegia | 17 (9.7) |

Feeding method and meal consistency

Majority of the participants (99.1%) were fed orally, while only a small proportion (0.9%) received nutrition via nasogastric (NG) tube. In terms of meal consistency, most children (82.7%) were provided with solid food, 15.0% required semi-solid meals, and 2.2% were fed liquids.

Nutritional status

A majority (60.6%) of the population was in a calorie deficit when compared to the recommended daily allowances [23]. It was seen that 50% of children under 5 years were in the SAM (24.5%) or MAM (25.5%) centiles, while 41.2% aged 5–19 years were underweight (thin) (Table 2). In addition, the 55 children under 5 years categorized as normal, overweight or obese, 38 (69.1%) were stunted. Furthermore, there was a significant association between nutritional status with GMFCS and limb involvement. CP severity (χ2 = 24.6, p < 0.05) and the number of limbs involved (χ2 = 10.8, p < 0.05) were directly proportional to undernourishment (SAM + MAM), with 59.3% of GMFCS 5 and 58.6% of children with quadriplegic CP also identified as undernourished children. Undernourishment was more prevalent among children at GMCFS level 5(58.6%) and quadriplegic CP. A majority (79.6%) of the underweight children were children with spastic CP.

Table 2.

Feeding type and meal consistency

| N (percentage %) | |

|---|---|

| Feeding Type | |

| Oral | 224 (99.1) |

| NG tube | 2 (0.9) |

| PEG | 0 (0.0) |

| Consistency | |

| Liquid | 5 (2.21) |

| Semi-solid | 34 (15.0) |

| Solid | 187 (82.7) |

Stunting

In this study, the frequency of stunting among children aged 2 to 18 years was assessed. Table 3 shows the number of stunted and normal height children in each age group. The prevalence of stunting decreased with age, i.e., the overall prevalence of stunting in the sample was 35.4%, with the highest percentage of stunting observed in the 1-5-year age group (51.5%). The stunting prevalence decreased in the older age groups, with 26.8% in the 6-12-year age group and 7.5% in the 13-18-year age group. Furthermore, the highest prevalence of stunting was observed in 2-year-olds, with 27 children classified as stunted, with no stunted children identified in the ages of 14, 15, 16, 17, and 18 years.

Table 3.

Nutritional status

| Age Group | Category | N (Percentage %) |

|---|---|---|

| Under 5 years | SAM | 27(24.5) |

| MAM | 28(25.5) | |

| Total | 55 (50.0) | |

| Normal | 48 (43.8) | |

| Overweight | 4 (3.6) | |

| Obese | 3 (2.7) | |

| 5–18 years | Thin | 48 (41.2) |

| Normal | 53 (45.6) | |

| Overweight | 11 (9.6) | |

| Obese | 4 (3.5) |

Caregiver perception

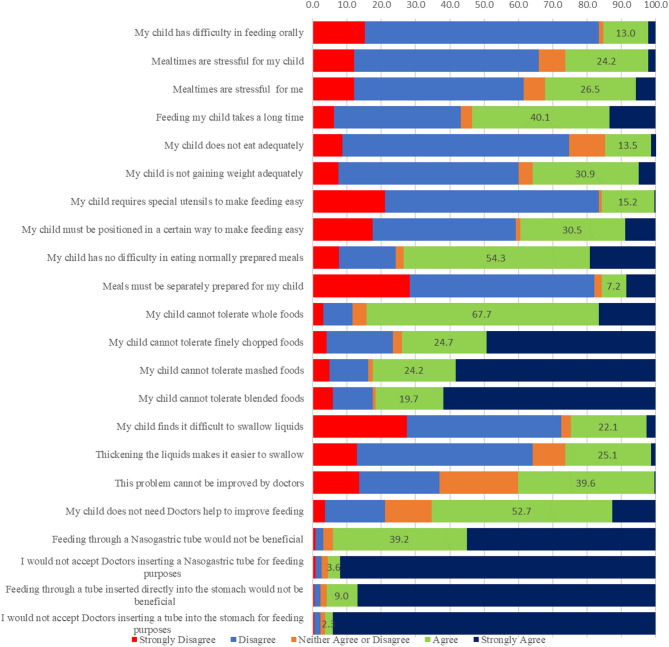

For each item, missing data were less than 2%, and maximum endorsement frequencies were below 95%. The data showed acceptable internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.73. [Supplementary Table S2] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Caregiver perception

Significant associations were found between specific caregiver perceptions and the nutritional status of their children (p < 0.05), based on chi-square analysis. Caregiver perceptions were categorized as agreement, neutrality, or disagreement with various feeding-related statements, and these were compared with the nutritional status of the child (classified as undernourished—SAM/MAM—or not undernourished). Among caregivers of undernourished children, 83.3% disagreed that oral feeding was difficult (p = 0.285), 68.6% believed their child ate adequately (p = 0.031), and 50% were either neutral or agreed that their child was gaining weight adequately (p = 0.000). A majority also disagreed that mealtimes were stressful for their child (58.9%, p = 0.039) or for themselves (52.0%, p = 0.010). Despite these children being undernourished, 40.1% of caregivers agreed that their child’s condition could not be improved by medical intervention (p = 0.740), and 65.3% disagreed that they would need a doctor’s assistance to improve feeding (p = 0.060). Furthermore, nearly all caregivers disagreed with non-oral feeding methods such as the use of nasogastric (95.5%, p = 0.050) and PEG tube feeding (96.4%, p = 0.131). These findings suggest a disconnect between objective nutritional status and caregiver perceptions, with many undernourished children’s caregivers believing their child was feeding adequately and not in need of medical or alternative feeding interventions. Additionally, significant associations were observed between caregiver perceptions and clinical characteristics such as GMFCS level, limb involvement, and tone (p < 0.05). Perceptions of feeding difficulties were more common among caregivers of children with GMFCS levels IV–V, greater limb involvement, and spastic cerebral palsy. Nonetheless, the need for and acceptance of medical intervention or alternative feeding methods remained low across most caregiver groups.

Quality of life

The proportion of missing data was less than 2%, and floor and ceiling effects were less than 10% for each summary score. Excellent total- and subscale internal consistency was demonstrated by high Cronbach’s alpha values (> 0.9) and item-total correlations (range: 0.55–0.99) [Supplementary Table S3]. Mean caregiver QoL scores in this study population were 57.9 (± 16.0), and the median total score was 53.8 out of a maximum score of 100 (highest QoL). Median summary scores for the subscales ranged from 35.0 (± 20.0) for worry to 75.0 (± 10.0) for cognitive functioning (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Means scores PedsQL tool

A one-way ANOVA test was used to compare the mean score of caregivers’ QoL across the GMFCS categories. This test revealed a significant trend (F = 10.4, p < 0.05), where the overall and sub-categorical QoL scores of the caregiver decreased with the severity of the disability (GMFCS) of their child. Caregivers with children at GMFCS level 2 scored the highest in all subcategories (total score mean = 66.7 ± 15.88), with the highest mean score seen in communication (76.30 ± 17.96) and the lowest mean score in caregiver worry (54.36 ± 24.95). A majority of the lowest subcategory scores were seen in caregivers with children at the GMFCS level 4 (total score mean = 51.60 ± 15.33), however, the lowest overall score was seen in caregivers of GMFCS 5 children (total score mean = 50.62 ± 11.88), with the lowest score being in caregiver worry (mean = 29.66 ± 15.42).

Notably, the QoL scores of caregivers decreased with the increase in the child’s number of limbs involved (F = 98.9, p < 0.05), i.e., caregivers of monoplegic CP children had the highest mean total score (65.75 ± 17.20) while caregivers of quadriplegic CP children had the lowest mean total QoL score (53.43 ± 15.24).

In terms of CP classification, caregivers of children with Ataxic CP and Mixed CP had the highest mean total QoL score (63.84 ± 11.24) and the lowest score (51.92 ± 16.92), respectively. However, there was no significant difference between the QoL (F = 0.58, p > 0.05) of caregivers whose child was underweight (54.9%) compared to caregivers whose child was not underweight (56.4%) (Table 4).

Table 4.

ANOVA test results

| ANOVA test statistic (F) | Degrees of freedom [df] (between groups, within groups) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GMFCS* QoL | 18.166 | 4, 221 | < 0.001 |

| Limb involvement* QoL | 19.45 | 4, 221 | < 0.001 |

| Predominant motor type * QoL | 0.332 | 4, 221 | 0.856 |

Discussion

This study evaluated the demographic and clinical characteristics of 226 children with CP, revealing a mean age of 6.83 ± 4.493 years and a male predominance. This was in par with some of the contemporary studies [24, 25] as well as with epidemiological studies in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMIC) [26]. A significant proportion of children were classified at GMFCS levels 4 and 5, indicating severe CP. This is higher than the proportion of 30–35% reported by Novak et al. [27], while it’s comparable with a study from LMICs [26], suggesting variability in CP severity across different cohorts. This highlights the necessity for tailored interventions for children with severe CP.

Additionally, spastic CP was the most common type, affecting majority of the children, with diplegic and quadriplegic forms being particularly prevalent. These findings align with recent studies reporting that spastic CP constitutes approximately 70–80% of cases [27]. The high prevalence of spastic forms underscores the importance of specialized care approaches.

The nutritional status assessment revealed high rates of undernutrition, with approximately half of the children under five years classified as severely acutely malnourished (SAM) or moderately acutely malnourished (MAM), and a substantial proportion of children aged 5–19 years identified as underweight. This is consistent with a recent study indicating similar undernutrition rates among children with CP in South Asia [28]. A significant association between nutritional status and both GMFCS level and limb involvement was found, with a majority of children at GMFCS level 5 and quadriplegic CP identified as undernourished. This highlights the compounded challenges faced by children with severe forms of CP and extensive motor involvement.

Spastic CP showed a strong correlation with undernutrition, with a preponderance of underweight children having this type of CP. Existing research suggests that spasticity increases energy expenditure, thereby heightening the risk of nutritional deficits [29, 30]. Furthermore, the study found that a significant proportion of the population was in a calorie deficit compared to recommended daily allowances, indicating widespread issues with meeting nutritional needs [23]. Similar challenges in maintaining adequate caloric intake in children with CP have been documented in recent research [29, 30].

Caregiver perceptions significantly influenced the nutritional status of the children. Among caregivers of undernourished children, many claimed that oral feeding was not difficult, and a considerable proportion believed their children had adequate calorie intake, despite evidence to the contrary. This gap between caregiver perceptions and actual nutritional status aligns with recent studies highlighting the need for better caregiver education [17]. Additionally, low stress perception among caregivers of undernourished children, with a majority not perceiving mealtimes as stressful, contrasts with other studies reporting high-stress levels among caregivers during feeding times [31]. The prevalent resistance to non-oral feeding methods among caregivers also reflects the need for improved education on feeding interventions [32].

The study confirmed the reliability and validity of the PedsQL in this setting, with excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.9). Findings were also consistent with results of a locally developed instrument to assess caregiver burden in CP (Caregiver difficulty scale) [33]. Caregivers’ overall QOL scores were low, with a mean of 57.9 (± 16.0), consistent with recent studies reporting lower QOL scores among caregivers of children with CP [17]. A significant trend of decreasing QOL with increasing severity of the child’s disability was observed, with caregivers of children at GMFCS level 2 scoring the highest in all subcategories, while those with children at GMFCS level 5 scored the lowest. This trend is also noted in recent literature, emphasizing the increasing burden on caregivers with more severely affected children [34, 35]. Moreover, QOL scores were affected by the number of limbs involved and the type of CP, with caregivers of quadriplegic children reporting the lowest scores, which is consistent with patterns seen in literature [36].

Interestingly, no significant difference in QOL was found between caregivers of underweight and non-underweight children, suggesting that factors other than nutritional status predominantly influence caregiver QOL. Even though the nutritional status per se has not affected the QoL of caregivers, its multifactorial effect on other aspects, such as performing activities of daily living can affect caregivers’ QoL [37]. This aligns with findings indicating that functional severity and daily caregiving demands are more significant determinants of caregiver QOL, as highlighted in a previous Sri Lankan study [35].

The paradoxical finding that many caregivers of undernourished children reported “no feeding difficulties” may be partially explained by cultural normalization, wherein chronic caregiving demands are internalized as routine, especially in settings where undernutrition is common [38]. Additionally, limited awareness of growth standards and developmental expectations among caregivers may further contribute to underreporting of stress or feeding challenges [39]. These findings highlight the importance of contextual factors in interpreting caregiver-reported outcomes and the need for caregiver education as part of holistic child health interventions.

These insights highlight the need for comprehensive, holistic management approaches that address both the nutritional and psychological needs of children with CP as well as their families. Findings call for early and targeted feeding interventions, including nutritional support and oro-motor therapy, to significantly improve growth parameters and support functional outcomes in children with CP [40, 41], with speech and language therapists playing a crucial role in the assessment and management of dysphagia. Their contribution is particularly important in low- and middle-income settings, where multidisciplinary care is essential [42].

Educating caregivers to align their perceptions with clinical realities is crucial, as is providing clear, evidence-based information to help them understand the importance of adequate nutrition and the potential benefits of alternative feeding methods. Additionally, strategies to reduce caregiver stress and improve QOL should be integrated into the care plan, including psychosocial support, access to respite care, and practical feeding solutions that minimize mealtime stress.

Limitations

The study utilized a convenience sampling method from a single centre, which may introduce potential selection bias. However, the chosen study setting—a major paediatric neurology unit serving a large and diverse patient population across a wide geographic area—is one of the few such centres in the country. This may partially mitigate concerns regarding the representativeness of the sample.

Associated factors affecting the nutrition of children with CP, such as gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, recurrent infections and constipation, were not included. This could be a potential limitation as this could also affect the overall nutritional status, perception of feeding and caregiver quality of life.

Height measurements are challenging in children with CP due to scoliosis and contractures. Segmental measurements to estimate height were not used in this study. This is a potential limitation when assessing the nutritional status.

Section C, which assessed parental perceptions of feeding difficulties, was developed by the authors based on their clinical experience with children diagnosed with cerebral palsy. However, a Delphi review was not conducted during the development of this section, which may represent a potential limitation.

CP classification (GMFCS level, CP type, limb involvement) and nutritional status may be interrelated and could independently or jointly influence caregiver quality of life. Although we analysed these factors separately in this study, we recognize that a more comprehensive multivariate approach could provide deeper insight into their contributions while accounting for potential confounding. Future research focusing on causal modelling is warranted to better understand these complex relationships.

The current study did not include an assessment of the psychological impact on caregivers, and consequently, no psychological interventions were provided to those reporting low quality of life or elevated stress levels. This limitation may represent a potential ethical consideration, highlighting the need for future studies to incorporate appropriate psychological support mechanisms when caregiver burden is evaluated.

Conclusion

This study underscores the multifaceted challenges faced by children with CP and their caregivers. High rates of undernutrition, stunting during early years, significant misconceptions about feeding and caloric intake, and low QOL among caregivers were prominent findings. Further research is essential to develop effective interventions that can improve both nutritional outcomes and caregiver well-being. In the given context, regular health education, nutritional assessment and providing nutritional supplements, and non-oral feeding methods where necessary will ensure a better nutritional outcome while improving parental attitude towards feeding. Interventions to improve parental perceptions of underlying nutritional deficiencies will significantly improve the holistic care for children with cerebral palsy in this setting.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

All patients who participated in the study.

Author contributions

SAC Conceptualised, data curation, analysis, investigation, methodology, administration, writing and editing the final draft.AA Basic Analysis and draft writing KCS Conceptualized, data curation, analysis, investigation, methodology, administration, editing the final draft SAC and KCS authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was not funded by any external authority. Authors declare that the study was solely self-funded.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of Sri Lanka College of Paediatricians (SLCP). SLCP/ERC/2022/06. Informed consent was obtained from the parents and guardians of all participants involved in the study. This study was conducted in compliance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rosenbaum PL, Paneth N, Leviton A, Goldstein M, Bax M, Damiano D, et al. A report: the definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev Med Child Neurol Suppl. 2007;109:8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McIntyre S, Goldsmith S, Webb A, Ehlinger V, Hollung SJ, McConnell K, Arnaud C, Smithers-Sheedy H, Oskoui M, Khandaker G, Himmelmann K. Global prevalence of cerebral palsy: A systematic analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2022;64(12):1494–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan PB. Nutrition and growth in children with cerebral palsy: setting the scene. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Johnson A, Gambrah-Sampaney C, Ogando-Rivas E, et al. Growth failure in children with cerebral palsy: nutritional perspectives and updates. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2019;73(5):5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaksic T, Cahill JL, O’Keeffe N, et al. Nutritional challenges in cerebral palsy: current knowledge and future perspectives. J Clin Med. 2021;10(9):1890.33925582 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell KL, Samson-Fang L. Nutritional management of children with cerebral palsy. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Gangil A, Patwari AK, Aneja S, Ahuja B, Anand VK. Feeding problems in children with cerebral palsy. Indian Pediatr. 2001;38(8):839–46. PMID: 11520994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donkor CM, Lee J, Lelijveld N, et al. Improving nutritional status of children with cerebral palsy: A qualitative study of caregiver experiences and community-based training in Ghana. Food Sci Nutr. 2019;7(1):35–43. 10.1002/fsn3.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benfer KA, Weir KA, Bell KL, Ware RS, Davies PS, Boyd RN. Oropharyngeal dysphagia and gross motor skills in children with cerebral palsy. Paediatrics. 2013;131(5). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Snider L, Majnemer A, Darsaklis V. Feeding interventions for children with cerebral palsy: a review of the evidence. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2011;31(1):58–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caregiver Challenges in Paediatric Feeding Disorders. Clinical management of children with feeding and swallowing disorders. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30(6):891–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller RE, Mangiaracina L, Littlefield S. Reducing mealtime stress for children with disabilities and their families: promoting a culture of feeding through problem-solving strategies. J Child Neurol. 2019;34(11):628–34. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raina P, O’Donnell M, Schwellnus H, Rosenbaum P, King G, Brehaut J, et al. Caregiving process and caregiver burden: conceptual models to guide research and practice. BMC Pediatr. 2004;4:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Basu AP, Pearse JE, Baggaley J, et al. Quality of life in children with cerebral palsy: perspectives of children and parents. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;60(9):871–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor C, Zhang M, Foster J, Novak I, Badawi N. Caregivers’ experiences of feeding children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review protocol of qualitative evidence. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2018;16(3):589–593. 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003521. PMID: 29521856. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Polack S, Adams M, O’banion D, Baltussen M, Asante S, Kerac M et al. Children with cerebral palsy in Ghana: malnutrition, feeding challenges, and caregiver quality of life. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology [Internet]. 2018;60(9):914–21. Available from: 10.1111/dmcn.13797 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.De Onis M, Garza C, Victora CG, Onyango AW, Frongillo EA, Martines J. The WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study: Planning, study design, and methodology. Food Nutr Bull [Internet]. 2004; 25(1_suppl_1): S15–26. Available from: 10.1177/15648265040251s104 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Ministry of Health - Sri Lanka. National Strategic Plan for Maternal and Child Health Nutrition 2021–2025 [Internet]. Colombo: Family Health Bureau; Available from: https://nutrition.health.gov.lk/english/resource/1317/

- 20.Varni JW, Sherman SA, Burwinkle TM, Dickinson PE, Dixon P. The pedsql™ family impact module: preliminary reliability and validity. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:55. 10.1186/1477-7525-2-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.PEDSQL TM (Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory TM) [Internet]. Available from: https://www.pedsql.org/translations.html [Accessed on: 11 April 2025].

- 22.Palisano RJ, Rosenbaum P, Bartlett D, Livingston MH. Content validity of the expanded and revised Gross Motor Function Classification System. Dev Med Child Neurol [Internet]. 2008;50(10):744–50. Available from: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03089.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Medical Research Institute. National Nutrition and Micronutrient Survey Sri Lanka. 2022. Available from: http://www.mri.gov.lk/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/National-Nutrition-and-Micronutrient-Survey-Sri-Lanka-2022.pdf

- 24.Downing J, Knapp KM, Talbot J, Basterfield L, Fairhurst C, McArthur P, et al. The prevalence of cerebral palsy in the North East of England by gestational age and severity of disability. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;43(3):423–30.31169415 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lungu C, Plesca D, Surugiu A, Stanescu A, Tanase M, Dinu G, et al. Differences in the prevalence of cerebral palsy in male and female patients: A study from a referral center. Med (Kaunas). 2021;57(3):278. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jahan I, Muhit M, Hardianto D, Laryea F, Chhetri AB, Smithers-Sheedy H et al. Epidemiology of cerebral palsy in low‐ and middle‐income countries: preliminary findings from an international multi‐centre cerebral palsy register. Dev Med Child Neurol [Internet]. 2021;63(11):1327–36. Available from: 10.1111/dmcn.14926 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Novak I, McIntyre S, Morgan C, Campbell L, Dark L, Morton N, et al. Early, accurate diagnosis and early intervention in cerebral palsy: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(9):897–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jahan I, Sultana R, Afroz M, Muhit M, Badawi N, Khandaker G, Dietary, Intake. Feeding Pattern, and Nutritional Status of Children with Cerebral Palsy in Rural Bangladesh. Nutrients [Internet]. 2023;15(19):4209. Available from: 10.3390/nu15194209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Sullivan PB, Lambert B, Rose M, Ford-Adams ME, Johnson A, Griffiths P. Prevalence and severity of feeding and nutritional problems in children with neurological impairment: Oxford feeding study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42(10):674–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Penagini F, Mameli C, Fabiano V, Brunetti D, Dilillo D, Zuccotti GV. Dietary intakes and nutritional issues in neurologically impaired children. Nutrients. 2015;7(11):9400–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor C, Badawi N, Novak I, Foster J. Caregivers’ feeding experiences of children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. Authorea (Authorea) [Internet]. 2024; Available from: 10.22541/au.170662719.90137473/v1

- 32.Petersen MC, Kedia S, Davis P, Newman L, Temple C. Eating and feeding are not the same: caregivers’ perceptions of gastrostomy feeding for children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology [Internet]. 2006;48(09):713. Available from: 10.1017/s0012162206001538 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Wijesinghe C, Fonseka P, Hewage C. The development and validation of an instrument to assess caregiver burden in cerebral palsy: Caregiver Difficulties Scale. Ceylon Medical Journal [Internet]. 2013;58(4):162. Available from: 10.4038/cmj.v58i4.5617 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Liu F, Shen Q, Huang M, Zhou H. Factors associated with caregiver burden among family caregivers of children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2023;13(4):e065215. Available from: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-065215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Hewawitharana BDR, Wijesinghe CJ, De Silva A, Phillips JP, Hewawitharana GP. Disability and caregiver burden: Unique challenges in a developing country. Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine [Internet]. 2023;16(3):483–91. Available from: 10.3233/prm-220070 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Surender S, Gowda VK, Sanjay KS, Basavaraja GV, Benakappa N, Benakappa A. Caregiver-reported health-related quality of life of children with cerebral palsy and their families and its association with gross motor function: A South Indian study. Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice [Internet]. 2016;7(2):223. Available from: 10.4103/0976-3147.178657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.De Zabarte Fernández JMM, Arnal IR, Segura JLP, Romero RG, Martínez GR. Carga del cuidador del paciente con parálisis cerebral moderada-grave: ¿influye el estado nutricional? An Pediatr (Barc) [Internet]. 2020;94(5):311–7. Available from: 10.1016/j.anpedi.2020.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Abdullah KL, Chien LY, Khan TM. Cultural influences on caregiving burden in parents of children with chronic illness: A systematic review. J Pediatr Nurs. 2019;45:1–9. 10.1016/j.pedn.2018.12.001.30594886 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Black MM, Walker SP, Fernald LCH, Andersen CT, DiGirolamo AM, Lu C, et al. Early childhood development coming of age: science through the life course. Lancet. 2017;389(10064):77–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31389-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sullivan PB. Gastrointestinal disorders in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities. Dev Disabil Res Rev [Internet]. 2008;14(2):128–36. Available from: 10.1002/ddrr.18 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Romano C, Van Wynckel M, Hulst J, Broekaert I, Bronsky J, Dall’Oglio L et al. European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Guidelines for the evaluation and treatment of gastrointestinal and nutritional complications in children with neurological impairment. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr [Internet]. 2017;65(2):242–64. Available from: 10.1097/mpg.0000000000001646 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Jahan I, Karim T. Multidisciplinary management of feeding difficulties in children with cerebral palsy: the role of speech and Language therapists in LMICs. Disabil CBR Incl Dev. 2020;31(3):28–43. 10.5463/dcid.v31i3.923. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.