Abstract

In wood defect detection, factors such as few-shot sample scarcity, diverse defect types, and complex background interference severely limit the model’s recognition accuracy and generalization ability. To address the above issues, this paper proposes an improved Faster RCNN model based on a dual attention mechanism (DAM). The model integrates cross-attention and spatial attention modules to enhance the expression of key region features, suppresses texture noise interference; the improved Wood-Region Proposal Network (WRPs) module utilizes feature mean pooling and cross-layer fusion strategies to significantly improve the quality and robustness of candidate box generation; in addition, the Wood-Feature Reconstruction Head (WFRH) module effectively enhances the adaptability to new classes and few-shot defects through multi-branch classification and weighted fusion mechanisms. After synergistic optimization of all modules, the model demonstrates superior detection accuracy and category discrimination capability. Experimental results show that the proposed method achieves state-of-the-art performance on the PASCAL VOC and FSOD datasets, particularly in the identification of 17 types of wood defects, where AP50 and AP75 are improved by 25% and 7.9%, respectively, validating the significant advantages of the proposed DAM mechanism under few-shot and complex background conditions. The findings of this study provide practical technical references for intelligent and efficient few-shot detection in real-world wood quality inspection tasks.

Keywords: Few-shot, Wood, Defect detection, Cross-attention, Spatial attention

Subject terms: Computational science, Computer science

Introduction

As an integral part of traditional manufacturing, wood processing and testing play a crucial role in driving industrial modernization through improvements in production efficiency and product quality. Object detection technology has demonstrated broad application prospects in wood classification, defect detection, and quality assessment, capable of significantly optimizing production processes and resource allocation1. However, due to the scarcity of wood samples, their variable textures, and complex features, current object detection models face challenges such as low detection accuracy and insufficient generalization ability under few-shot conditions in this field2,3.

In few-shot detection tasks, models must learn effective feature representations with only a limited number of training samples, facing the dual challenges of data scarcity and weak model generalization ability4,5. De Blaere et al. constructed the SmartWoodID database, providing a data foundation for few-shot detection. It mainly focuses on cross-sectional images, making it difficult to cover the diverse feature variations in real-world environments6. He et al. attempted to combine GANs with few-shot learning to expand the sample size and improve performance, but the diversity and authenticity of the generated samples remain challenging7. In terms of recognition accuracy, Figueroa-Mata et al. used convolutional neural networks to classify native tree species in Costa Rica and optimized accuracy through data augmentation, but the recognition performance was still limited in samples with small inter-class differences8. Additionally, Ghosh et al. proposed strategies such as resampling and loss function adjustment to address the class imbalance problem, which effectively mitigated bias but still posed overfitting risks under real-world data distributions9. Han et al. proposed FGLAM feature fusion method also showed potential but requires improved stability under complex textures or significant spectral variations8. Therefore, effectively addressing the challenges of insufficient few-shot data, low detection accuracy, and complex texture background interference in wood surface defect detection is the core problem this study aims to solve.

In this study, we designed a dual attention mechanism (DAM) that integrates spatial attention and cross-attention, embedded in the Faster RCNN architecture, aiming to construct a robust and efficient small sample target detection model for wood. The model enhances the representation ability of key region features through a modular design, significantly improving detection accuracy and model generalization ability. The contributions of this study are as follows:

(1) We propose a dual attention feature extraction strategy that integrates cross-attention and spatial attention mechanisms for few-shot wood defect detection tasks, significantly improving the model’s adaptability to new categories and discrimination performance while enhancing the response of key target regions. (2) Addressing the issue of false detections in small samples and complex texture backgrounds in traditional RPN modules, the Wood-RPN module is designed, introducing feature mean pooling and cross-layer prediction fusion mechanisms to achieve dual improvements in robustness and accuracy in the region proposal generation process. (3) We designed the Wood-Feature Reconstruction Head module, combining a multi-branch classification strategy and a dynamic weight fusion mechanism to effectively enhance the model’s ability to reconstruct fine-grained target features, thereby improving its detection performance and generalization ability under complex background conditions.

Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method achieves outstanding detection performance on the wood defect benchmark dataset and the PASCAL VOC and FSOD public datasets, fully validating the model’s effectiveness and generalizability in few-shot object detection tasks. This provides theoretical innovation and practical support for intelligent wood detection scenarios.

Methods

Few-shot object detection

Few-shot learning is an approach to address the challenge of the scarcity of labeled data, aiming to improve the generalization ability of models with few-shot labeled data. The core idea is to learn the commonalities in different subtasks during model training so that the model can adapt quickly to new tasks to meet the needs of practical applications10 ,11. Each of the four main approaches in few-shot learning has advantages and disadvantages.

Metric-based learning methods, such as twin networks12 and prototype networks13improve classification performance by modeling the distance between samples, with the advantages of being able to avoid the overfitting problem and improve classification accuracy, however, their effectiveness relies on good feature representations and effective distance metrics, which places high demands on model design14.

Meta-learning approaches, such as MAML15 and Meta RCNN16have a strong generalizability ability because they train the model on multiple tasks so that it can quickly adapt to new tasks, however, such approaches usually require many training tasks, resulting in a long training time and high consumption of computational resources, and more complex model design15.

Data augmentation methods, such as generative adversarial networks17 and feature space transformations18extend the dataset by generating or synthesizing new samples to improve the robustness and generalization ability of the model, however, the quality of the generated samples directly affects the performance of the model, and parameter tuning is more complex19.

Multimodal approaches, such as aligned variational autoencoders and multimodal embedding models20,21enhance the performance of the model by combining information from different modalities, such as visual and linguistic, and exploiting intermodal complementarities. Although this approach can improve the classification performance and robustness of the model, the acquisition and processing of multimodal data are more complex and it is challenging to design effective fusion strategies22,23.

Model architecture design

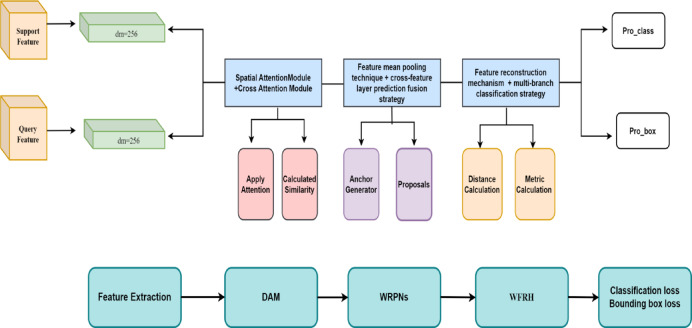

This flow demonstrates a few-shot object detection model that combines a dual-attention mechanism and a feature reconstruction strategy, designed for few-shot learning environments, as shown in Fig. 1. Through this flow, the model can learn effective features from limited data and accurately detect and localize targets in new images. The model consists of several key modules, including feature extraction, a spatial attention module, a cross-attention module, a region suggestion network, and a feature reconstruction header. Through the collaborative work of these modules, the model improves detection accuracy and demonstrates good generalizability in a few-shot environment. The model performs well in few-shot environments through the synergistic work of the above modules and can effectively learn and accurately detect targets from limited data.

Fig. 1.

Model structure for few-shot object detection in wood.

As shown in the mathematical model code Table 1 above, this paper integrates a multi-module complex algorithm into the DAM-Faster RCNN object detection framework. By combining feature extraction, spatial attention enhancement, cross-attention matching, region proposal generation, and feature reconstruction modules, an efficient detection model suitable for few-shot wood defect detection is constructed. The modules are connected in series according to the information processing flow to form an end-to-end joint training structure: first, the feature extraction module encodes the support images and query images based on a shared backbone network to generate basic visual features; then, the spatial attention module extracts key target regions from the support images to enhance discriminative feature expression; next, the cross-attention module optimizes the target representation through multi-dimensional matching between the support and query images, improving cross-sample feature consistency; then, the improved Wood-RPN module generates high-quality candidate boxes based on the fused salient features and extracts local region features through ROI Pooling; finally, the Wood-Feature Reconstruction Head completes defect classification and localization prediction.

Table 1.

DAM-Faster RCNN: Few-shot defect detection method.

The above modules are functionally complementary and highly compatible in terms of interfaces, with good integration feasibility. The introduction of the attention mechanism effectively improves the model’s generalization ability in few-shot tasks, where spatial attention helps suppress background interference, while cross-attention strengthens inter-class guidance. The feature reconstruction module further optimizes the stability and consistency of feature expression, alleviating the problem of support-query feature alignment difficulties. The overall model retains the detection efficiency of Faster RCNN in terms of architecture, while effectively addressing the issues of low detection accuracy and weak generalization ability caused by complex and diverse defect categories under few-shot conditions through refined module integration. It demonstrates stronger robustness and adaptability, particularly in complex texture backgrounds and multi-class fine-grained defect detection tasks.

DAM

DAM is a combination of cross-attention and spatial-attention modules used to construct a neural network based on a full cross-attention mechanism, designed for a few-shot learning task, as shown in Fig. 2. The module enhances the performance of the model in few-shot scenarios by encoding the features of support samples and query samples and dynamically aggregating the feature information of the support samples into the representation of the query samples via the spatial attention mechanism. The module first extracts the multilevel features of the support and query sets through a convolution layer, then integrates the limited support features through a weighted support aggregation strategy, and accurately matches the similarity of the support and query features through a spatial attention mechanism. Finally, the decoder module optimally adjusts the query features to improve the detection accuracy of the target object. This design not only effectively solves the feature scarcity problem under few-shot conditions, but also enhances the adaptability and stability of the model on new categories for targets and prevents the catastrophic forgetting phenomenon. The experimental results show that this module significantly improves the average accuracy of the model in few-shot object detection tasks, especially in scenarios with extremely limited data, and provides new solutions and ideas for the field.

Fig. 2.

Model structure of the DAM.

To systematically sort out the execution logic of the module and clarify the change relationship of the feature dimensions in each stage, this paper further summarizes its core operation flow and feature flow path. Table 2 systematically presents the specific operation steps, input and output dimensions, and corresponding functions of each stage of the DAM module. The module integrates the cross-attention mechanism based on supporting feature-weighted aggregation and the spatial attention mechanism based on convolutional matching. It constructs a path for joint modeling of intra-class feature prior and spatial saliency. By introducing dynamic convolution and attention guidance strategies, the model effectively improves the recognition accuracy of the target region in few-shot scenarios.

Table 2.

Dimensional change table for DAM Module.

| Step | Operation | Input dimension | Output dimension |

Descriptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | convolutional encoding | [m, c, w, h] | [m, 1, w, h] | Generating Attention Maps |

| 2 | Weighting support features with attention maps | [m, 1, w, h] | [m, c, w, h] | Support for feature weighting |

| 3 | Flatten the feature map spatial dimension |

[m, c, w, h] [n, c,w, h] |

[m, c,l] [n, c,l] |

Calculate the similarity between the query and the supporting features and generate the similarity matrix |

| 4 | Softmax for normalization |

[m, c,l] [n, c,l] |

[m, n] | Get the attention map |

| 5 | Weighting Value | [m, n] | [m, c, w, h] | Fusing support features to query features |

| 6 | Integration support features | [m, c, w, h] | [c, w,h] | Integration of the two branches of attention |

In the spatial attention module, the support features are encoded by convolution and an attention map is generated:

| 1 |

Where  is the Sigmoid function, and apply it to the original feature map to generate an attention map of shape [m, 1, w, h], which is used to weight the support features.

is the Sigmoid function, and apply it to the original feature map to generate an attention map of shape [m, 1, w, h], which is used to weight the support features.

| 2 |

Where  denotes element-by-element multiplication.

denotes element-by-element multiplication.

In the cross-attention module, support features and query features are used as values and queries, respectively, with the shapes [n, c, h, w] and [m, c, h, w].

is made similarity with each support feature

is made similarity with each support feature  . First Flatten feature map space dimensions:

. First Flatten feature map space dimensions:

| 3 |

The attention distribution is obtained by calculating the similarity between the query and the supporting features, generating the similarity matrix and Softmax for normalisation:

| 4 |

Reconstructing support features with similarity:

| 5 |

Generate a fused feature map for each query sample, reconstructed Reshape as

| 6 |

.

The result of the eventual fusion of the two branches of attention:

| 7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

Where  as learnable weights. The output combines the enhanced features of spatial saliency and category structure.

as learnable weights. The output combines the enhanced features of spatial saliency and category structure.

WRPNs

In the field of deep learning and target detection, the optimal design of the RPNs is the key to improving detection accuracy and efficiency. To address the challenges of target detection in few-shot and complex backgrounds, this paper proposes the WRPNs module, which provides innovative improvements over the traditional RPNs as shown in Fig. 3. The WRPNs module introduces the feature mean pooling technique and cross-feature layer prediction fusion strategy, which aims to increase the cohesiveness of feature expression by eliminating redundant information, thus increasing the robustness of the model to different scales and complex backgrounds. In addition, the module optimizes the anchor generation mechanism and candidate region screening process, which improves the accuracy of target localization and significantly reduces the false and missed detection rates through refined encoding and decoding strategies. In the model training phase, WRPNs employ a supervised learning mechanism to guide the model training via accurate target location labels, which significantly accelerates the convergence speed of the model and enhances the accuracy and stability of target localization compared with traditional self-supervised methods. Even in the case of a variable target size, complex background, or partial occlusion, WRPNs still show achieve excellent detection performance. Therefore, this paper kindly introduces target frame regression and the design of multiple loss functions to optimize the location and classification performance of the prediction frame.

Fig. 3.

Model structure of the WRPNs. This figure illustrates the workflow of WRPNs in the wood detection task. First, the backbone network generates an input feature map with the shape [c, w, h], where c, w, and h represent the number of channels, width, and height, respectively. This feature map is passed as input to the RPN head, which contains a 3 × 3 convolutional layer to extract more localized features. This is followed by two 1 × 1 convolutional layers, which output the category score and bounding box regression. The anchor generator generates anchor points with different scales and aspect ratios, which are used as candidate regions. With proposals, the network predicts candidate frames that may contain the target and further filters them for high quality with Filter Proposals. The filtered proposals boxes are passed to the ROI pooling layer to normalize regions of different sizes to a fixed size, providing input for subsequent bounding box regression and classification. Ultimately, the loss function, which consists of the bounding box regression error and the classification error together, computes the training error of the model and is used to optimize the model. This process effectively performs target detection of wood defects under few-shot conditions, improving detection accuracy and generalizability.

Bounding box regression

Target box regression is used to calculate the offset and scaling of the predicted bounding box concerning the reference box, and is mainly used in the regression header of the network output to adjust the predicted box to be closer to the real target position, as shown in Eq. 10.

| 10 |

includes the center coordinates and width and height of the predicted bounding box.

includes the center coordinates and width and height of the predicted bounding box. : represents the center coordinates and width and height of the anchor box.

: represents the center coordinates and width and height of the anchor box. : represents the predicted bounding box regression parameters indicating translation and scaling of the anchor box to the target box.

: represents the predicted bounding box regression parameters indicating translation and scaling of the anchor box to the target box.

Loss function

Classification loss

Classification loss is used for the classification loss component of the target detection task, the main purpose of which is to measure the discrepancy between the model’s classification predictions and the true labels and to help the model continuously adjust the parameters to improve the prediction accuracy during the training process is shown in Eq. 11.

| 11 |

Included among these :Predicted Object ness Score.

:Predicted Object ness Score.  : actual objectness labels, 1 for the target box and 0 for the background box.

: actual objectness labels, 1 for the target box and 0 for the background box. : The number of samples used to normalize the classification loss.

: The number of samples used to normalize the classification loss.

Boundary frame losses

Bounding boxes are usually used for bounding box regression in target detection tasks to help the model gradually adjust the predicted bounding boxes during the training process so that they are closer to the real target position and improve the accuracy of detection, as shown in Eq. 12 and Eq. 13.

| 12 |

| 13 |

Included among these : Predicted bounding box regression parameters.

: Predicted bounding box regression parameters.  : True bounding box regression parameters.

: True bounding box regression parameters.  : The number of samples used to normalize the regression loss.

: The number of samples used to normalize the regression loss.  : Smooth L1 loss function.

: Smooth L1 loss function.

WFRH

In the research field of target detection and few-shot learning intersection, effective fusion of feature reconstruction techniques and region suggestion networks is regarded as a key challenge to break through the bottleneck of detection performance. Traditional target detection models are often limited in performance in few-shot sizes and complex background situations, making it difficult to accurately identify target categories and maintain localization accuracy. To address this problem, this paper proposes the Wood-Feature Reconstruction Head module (WFRH), which innovatively integrates the feature reconstruction mechanism with the multi-branch classification strategy to significantly improve the target detection capability of the model in complex environments. The module enhances the discriminative and generalization ability of feature expression by supporting the fine alignment of query features and introducing the design of a multilayer perceptron and a lightweight convolutional layer combination. In addition, for the common background interference problem in wood detection, the module introduces a special background classification branch to accurately distinguish the foreground from the background, which significantly reduces the risk of false detection.

Based on this, Wood-Feature Reconstruction Head further designed an intelligent weighted fusion mechanism (shown in Fig. 4) for integrating classification results from multiple encoding paths. The mechanism consists of three complementary feature encoders (Flatten, Conv, and Score) that extract the feature distance between the support and the query, respectively, and form three different similarity scoring tensors, denoted as:

| 14 |

Fig. 4.

Intelligent weighted fusion mechanism.

Where  is the number of candidate frames,

is the number of candidate frames,  is the number of categories, and 1 indicates the background class. Subsequently, normalised fusion weights are generated by introducing a vector of learnable parameters

is the number of categories, and 1 indicates the background class. Subsequently, normalised fusion weights are generated by introducing a vector of learnable parameters  , using the softmax function:

, using the softmax function:

| 15 |

The final fused classification distance is denoted as:

| 16 |

The weighting mechanism can adaptively learn the importance of different branches during the training process, so as to fully exploit the information redundancy and complementarity of multi-view feature representations, and improve the classification robustness and stability of the model in complex backgrounds and scenarios with high inter-class similarity.

Boundary box projections

The main focus of bounding box prediction is to generate the regression parameters of the bounding box through the fully connected layer, which in turn adjusts the position and size of the anchor box to more accurately locate the target object in the image, as shown in Eq. 17.

| 17 |

x includes input features, typically high-dimensional features extracted from support features and query features. Fully connected layer for generating bounding box regression parameters.

Fully connected layer for generating bounding box regression parameters.

Ancillary losses

The role of auxiliary loss is to force the support features of the same category to be more similar and the support features of different categories to be more distinguishable by measuring the similarity between the support features during the model training process. This auxiliary loss can help the model to better learn the differences between the categories in the case of few-shot, and thus improve the classification or detection accuracy of the model, as shown in Eq. 18.

| 18 |

Included among these  : encoding of support features. M: Normalization factor for the loss term.

: encoding of support features. M: Normalization factor for the loss term.

Experiments and results

Datasets

In this study, a total of 837 images covering 17 different types of wood defects were acquired, as shown in Table 3. By accurately labeling the defects in each image, 2189 defect instances were obtained. These wood defects include dry knots, wrapped knots, corner knots, decay knots, leaf knots, edge knots, resins, beard knots, core streaks, small knots, splits, defects, bark sacs, and molds. Therefore, an in-depth study of these defects via deep learning is highly important for accurate protection and efficient utilization of wood.

Table 3.

Wood defect detection dataset. There are 17 types in the dataset and the dataset has a total of 837 images with a total of 2,189 defect counts.

Experimental setup

For the wood dataset, the experimental setup is such that we randomly split the 17 classes into base classes and new classes at a ratio of 8:2. For the n-way k-shot problem, we split the classes into multiple tasks. Each task contains n classes of support images and query images, which are distinct from each other across tasks.

In the concrete implementation of our experiments, we used ResNet50 and a feature pyramid network (FPN) for our model. We used the pretrained ResNet50 provided by PyTorch, with the standard batch size set to 16. During training, the learning rate was 0.002 for the first 56,000 iterations and was tuned to 0.0002 for the next 4000 iterations. The optimizer used the standard stochastic gradient descent method, with the momentum parameter set to 0.9 and the weights decayed to 1e-4. the query image’s The short side of the query image is adjusted to 600 pixels and the long side is limited to no more than 1000 pixels. The supported image was cropped according to a ground truth bounding box with 16-pixel padding and then the image was resized to 320 × 320. We used typical evaluation metrics AP50 and AP75 for the performance evaluation of the model.

Ablation experiment

Attention mechanisms are widely used in deep learning models, especially in computer vision tasks, where performance can be significantly improved by enhancing the feature representation of the model. This ablation experiment aims to systematically evaluate the impact of different attention mechanisms on the performance of few-shot object detection models, specifically exploring the contributions of several configurations to the AP50 and the AP75. Firstly, no attention, which serves as a baseline model without using any attention mechanism; second, cross-attention, which uses the cross-attention mechanism to align and fuse features from different inputs to capture the correlation between the inputs; and then cross-attention + spatial Attention, which further combines the spatial Attention mechanism with the cross-attention mechanism to focus on the key locations in the feature maps to enhance attention to important regions; and finally self-attention, which employs the self-attention mechanism to model the global dependencies of input features and capture the long-distance dependencies between features. The comparative analysis of these configurations allows us to gain a deeper understanding of the specific impact of different attention mechanisms on model performance.

In the experimental setup, to rigorously evaluate the impact of different attention mechanisms, this experiment introduces the above attention mechanisms one by one under the same training and testing environments, and adopts AP50 and AP75 as the main evaluation metrics. The AP reflects the average detection accuracy of the model under all IoU thresholds, whereas the AP50 focuses on the detection accuracy when the IoU is greater than 0.5, and the AP75 focuses on the detection accuracy when the IoU is greater than 0.75. By analyzing these metrics, the effects of different attention mechanisms on model performance can be comprehensively evaluated.

This ablation experiment systematically assessed the contributions of different attention modules to a model’s performance by comparing the performances of the no-attention mechanism, self-attention mechanism, cross-attention mechanism, and cross-attention + spatial attention mechanism in a target detection task, as illustrated in Table 4. The experimental results show that the baseline model without the attention mechanism performed the worst, demonstrating the importance of the attention mechanism in improving feature representation. The cross-attention module significantly improved the AP50 and AP75 of the model, proving its effectiveness in feature fusion. The cross-attention + spatial attention module further confirms the model’s performance, especially in complex scenarios with excellent feature capture ability, which suggests that the dual design can better integrate multidimensional feature information and enhance the robustness and accuracy of the model. In contrast, the self-attention mechanism, despite showing good results in global feature modeling, results in slightly lower performance than cross-attention + spatial attention because of its computational complexity and lack of attention to local details. Overall, the cross-attention and spatial attention modules perform optimally in terms of balancing performance and computational complexity, showing superiority in few-shot object detection.

Table 4.

The results of ablation experiments.

| Methodologies | AP50 | AP75 |

|---|---|---|

| No attention | 8.7 | 18.4 |

| Self-attention | 16.5 | 21.5 |

| Cross-attention | 20.8 | 25.3 |

| Cross-attention + spatial attention | 33.7 | 26.3 |

Loss analysis

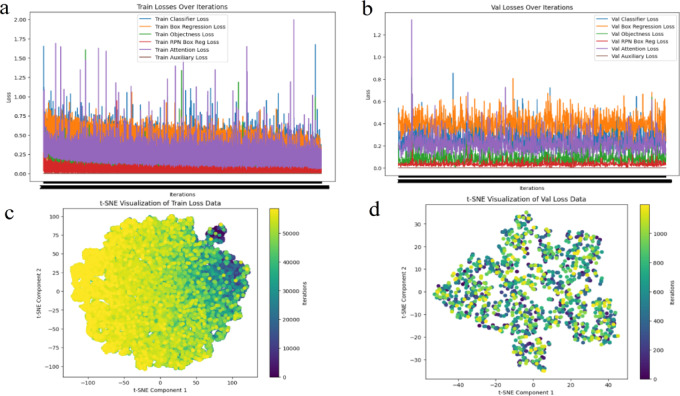

This experiment aims to evaluate the performance of different loss functions in the target detection task and to understand the impact of each loss term on the model performance through the trend of loss changes during training and validation and the visualization of the t-SNE feature distribution. We conduct experiments using a model based on the Faster RCNN architecture with multiple loss functions including classification loss, bounding box regression loss, targeting loss, RPN regression loss, attention loss, and auxiliary loss. The experimental steps include recording the dynamics of each loss term in the training set, evaluating the convergence and stability of the model, and testing the generalization ability of the model in the validation set. Moreover, we use t-SNE to visualize the features in the training and validation sets in reduced dimensions and analyze the distribution of the features in the low-dimensional space as a means of assessing the effectiveness of the model in extracting features. Through these analyses, we hope to reveal the role of different loss functions in model optimization and provide a strong basis for further improving the performance of target detection.

By analyzing the performance of the Faster RCNN model embedded with cross-attention and spatial-attention mechanisms in the wood few-shot object detection task, it can be seen that the model demonstrates excellent learning and generalization capabilities when dealing with few-shot data. Firstly, from the trend plots of the training and validation losses illustrated in Fig. 5a, b, it can be observed that the loss function of the model gradually converges during the iteration process, indicating that it can learn effectively with limited samples and maintain a stable detection performance on the validation set. This also reflects the key role of the cross-attention and spatial attention mechanisms in enhancing the feature correlation between the support set and the query set, helping the model to focus on the target region more precisely. In addition, as shown in Fig. 5c and Fig. 5d, the t-SNE visual analysis demonstrates the low-dimensional embedding effect of the model in the high-dimensional feature space, revealing an obvious clustering structure, which further proves that the model can effectively capture the neighboring distributions of similar feature samples and enhance the detection ability of new categories. In summary, the model successfully addresses the challenges in few-shot object detection through modular design and an optimized feature enhancement mechanism, which significantly improves the detection accuracy and generalization performance.

Fig. 5.

Trend plot of loss analysis. (a) Trend of training loss. (b) Trend of the validation loss. (c) t-SNE visualization analysis of training data. (d) t-SNE visualization analysis of test data.

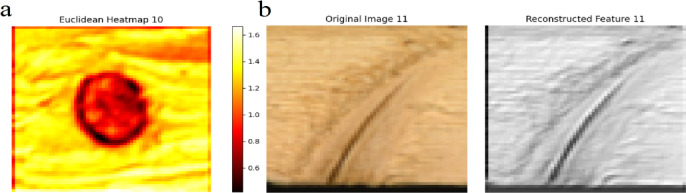

Feature reconstruction analysis

We conducted a visualization experiment for feature reconstruction on the wood dataset. This experiment contains five categories of edge knots, corner knots, leaf knots, dry knots, and no defects, and each category contains five support images and one query image. Using a real bounding box, the support images and the query image are cropped to instances, then filled with 16-pixel zeros and scaled to 320 × 320. These images are fed into a backbone network for feature extraction, and then directly fed into the wood-feature reconstruction header for feature reconstruction to visually evaluate and improve the model’s performance in the few-shot wood defect detection task and ensure that the model can still have a high detection accuracy and high quality of the wood defect detection in the limited data. still have high detection accuracy and strong generalization ability.

The Faster RCNN model embedded with cross-attention and spatial attention mechanisms demonstrates excellent performance in the wood few-shot target detection task. The feature reconstruction results illustrated in Fig. 6a, show that the model can successfully reproduce the wood defect features in the support image in the query image, demonstrating its excellent feature extraction and reconstruction capabilities under limited sample conditions. The Fig. 6b shows the Euclidean distance heatmap and Softmax heatmap further demonstrating the model’s ability to accurately localize and classify the knots and scars in the regions. The model exhibits high confidence and low distances in these regions and can capture key defect features accurately.

Fig. 6.

Feature reconstruction analysis plots. (a) Feature reconstruction plot. (b) Euclidean distance thermogram and softmax thermogram.

The Euclidean distance thermogram in Fig. 7a shows the model’s high focus on key defect regions, especially in the crack and knothole areas, demonstrating its acuity in feature capture. Despite some response from the background regions, overall, the model’s attention mechanism effectively focuses on the target features. The comparative analysis of Fig. 7b also shows that the model can successfully capture the main contours of wood cracks, demonstrating a high feature reconstruction accuracy. In summary, the model possesses multiple advantages in feature extraction, defect reconstruction, and accurate classification, and can effectively extract and reconstruct the main features of wood defects under limited data conditions, especially in key regions such as knots and scars, demonstrating high localization and classification accuracy. Although there is still room for improvement in dealing with background interference and detail reconstruction, the model performs well in few-shot object detection for wood. Nevertheless, optimization of background interference suppression and detail reconstruction will be a key direction for future research.

Fig. 7.

Comparison of feature reconstruction methods. (a) Euclidean distance thermogram of the drying scar. (b) Comparative analysis of the original and reconstructed images.

Discussion

Comparison of experimental setups

In this study, we use two datasets, PASCAL VOC and FSOD, for model evaluation, following the training settings of FSRW24,25respectively. For the n-way k-shot problem, the experiments divide the categories into multiple tasks, each containing n categories of support and query images. The model uses ResNet50 as the backbone network, and all the experiments are performed on 2 Tesla A100 GPUS with a batch size of 16. The learning rate is set to 0.002 for the first 56,000 iterations, and 0.0002 for the subsequent 4,000 iterations, and the optimizer is stochastic gradient descent with a momentum coefficient of 0.9 and a weight decay coefficient of 1e-4. In terms of data processing, the shorter side of the query image is adjusted to 600 pixels, the longer D-side is limited to 1000 pixels, and the supported image is cropped according to the real labeled bounding box, and adjusted to a size of 320 × 320 after filling the surrounding area is filled with a 0 value of 16 pixels.

PASCAL VOC dataset

In this study, we split the 20 categories into 15 base categories and 5 new categories based on the PASCAL VOC07/12 dataset, with three different new categories split according to the experimental configuration of FSRW. For more details on these three splits, Novel-class split1 split: bird, bus, cow, motorbike, and sofa; Novel-class split2 split into empty bottle, cow, horse, sofa; Novel-class split3: boat, cat, motorbike, sheep, sofa. In the first stage, the model is trained on 15 base categories. In the second phase, the model was fine-tuned on 5 new categories.

In the few-shot object detection task, the different algorithms show significant differences in the PASCAL VOC dataset, especially in terms of stability and accuracy when dealing with new category segmentation, as shown in Table 5. Meta Det achieves an m AP of 49.6% in the 10-shot setting in the Novel-class split1 but decreases significantly to 20.2% in the 1-shot setting in split3, indicating insufficient generalizability to new categories. The Meta RCNN has a good mAP of 53.7% in the 10-shot setting in split1, but only 9.7% in the 1-shot setting in split2, which also has limited generalizability ability. In contrast, the TFA w/fc and TFA w/cos show greater stability, with TFA w/fc achieving mAP of 56.9% in the 10-shot setting of split1, whereas the TFA w/cos, by introducing cosine similarity, achieves mAP of 56.2% in split1 and maintains mAP of 49.5% even in the 5-shot setting of split3 49.5% mAP. FSCE enhances feature learning through contrast learning and performs well under all splits, especially reaching 39.3% m AP in the 3-shot setting of split2, demonstrating strong generalizability.

Table 5.

Accuracy changes for different algorithms on the PASCAL VOC dataset.

| Methods/shot | Novel-class split1 | Novel-class split2 | Novel-class split3 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 19 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 10 | |

| Meta Det26 | 18.7 | 20.7 | 30.5 | 36.5 | 49.6 | 21.6 | 22.8 | 27.8 | 31.4 | 42.5 | 20.2 | 24.1 | 29.3 | 43.6 | 44.3 |

| Meta RCNN27 | 17.9 | 26.7 | 34.5 | 43.7 | 53.7 | 9.7 | 20.4 | 30.4 | 35.1 | 46.2 | 15.7 | 19.3 | 28.6 | 42.7 | 48.8 |

| TFA w/fc28 | 36.4 | 29.4 | 44.0 | 55.4 | 56.9 | 18.1 | 29.1 | 33.6 | 35.7 | 38.5 | 27.3 | 33.7 | 42.9 | 49.5 | 49.7 |

| TFA w/cos28 | 36.9 | 36.5 | 45.1 | 55.9 | 56.2 | 24.0 | 26.8 | 32.3 | 34.8 | 39.2 | 30.7 | 35.2 | 42.9 | 49.5 | 49.7 |

| FSCE29 | 38.9 | 41.9 | 52.3 | 53.4 | 58.7 | 27.9 | 31.7 | 39.3 | 33.2 | 47.8 | 33.6 | 34.7 | 39.5 | 50.7 | 53.7 |

| Ours | 38.4 | 42.3 | 53.6 | 56.0 | 59.6 | 24.8 | 33.7 | 38.7 | 45.9 | 53.8 | 29.7 | 37.8 | 45.9 | 51.5 | 53.9 |

Our proposed Ours method maintains a high mAP under all segmentation conditions, e.g., 59.6% in the 10-shot setting of split1, 53.8% in the 10-shot setting of split2, and more than 50% in split3, etc. The Ours method demonstrates excellent detection accuracy and stability, especially in split3, because of the innovative feature learning mechanism and architectural optimization. With the innovative feature learning mechanism and architectural optimization, the method demonstrates excellent detection accuracy and stability, especially when dealing with few-shot and complex scenes. In summary, our method is the most stable and accurate in few-shot object detection and has a significant competitive advantage over other methods, especially under the new category segmentation conditions, which significantly improves the accuracy and generalizability of few-shot object detection.

FSOD dataset

The FSOD dataset is a specially constructed dataset for few-shot learning scenarios, containing a total of 1000 categories, of which the training set contains 800 categories and the test set contains 200 categories. The FSOD data are derived from the ImageNet and Open Images V4 datasets, and compared with the traditional dataset PASCAL VOC, FSOD provides richer categories. However, the FSOD dataset has a significant imbalance, and the data distribution shows a typical long-tailed distribution. In addition, the semantics of the categories in the training and test sets differ significantly, which makes model evaluation more difficult.

The performance of target detection algorithms in the 5-way 5-shot learning configuration on the FSOD dataset shows significant variation as shown in Table 6. The LSTD method achieves 23.7% on AP50 and 13.9% on AP75. This result indicates that LSTD has some capability in few-shot detection. However, its performance declines significantly on the high-precision AP75 metric. This drop may be due to its limited ability to generalize and capture complex target features effectively. In contrast, the AP50 and AP75 of the FSOD model under the same configuration are 27.1% and 18.7%, respectively, which is a significant improvement over LSTD, especially in the AP75 metric, the advantages of FSOD in feature extraction and generalizability ability. The classical Faster RCNN framework performs weakly in the few-shot environment, with both its AP50 and AP75 similar those of LSTD, indicating its lack of adaptability in dealing with new target features.

Table 6.

Comparison of the accuracies of different algorithms on the FSOD dataset.

Our approach shows significant advantages in few-shot object detection. Under the 5-way 5-shot configuration, the model achieves 30.3% and 26.7% on AP50 and AP75, respectively, which is the best among all the compared algorithms, and especially demonstrates excellent high-precision detection on the AP75 metric. By integrating the optimization module, the cross-attention and spatial attention modules, the region suggestion network, and the feature reconstruction header, our model excels in feature extraction and background interference suppression, achieving both improved detection accuracy and generalizability ability. This result highlights the great potential of our method in the field of few-shot object detection, surpassing existing conventional methods.

Conclusion

In this study, we propose an innovative model architecture for the few-shot target detection challenges faced in the wood processing and inspection industry. The model integrates several modules, such as feature extraction, spatial attention, cross-attention, a region suggestion network and a feature reconstruction head, and exhibits excellent detection accuracy and good generalization ability under limited data conditions. Through this study, we have successfully solved the overfitting problem that traditional target detection models are prone to in the case of few-shot and significantly improved the detection accuracy, which provides a more intelligent and efficient solution in the field of wood inspection.

We plan to further optimize the model structure and perform finer feature extraction and classification for different types of wood defects. In addition, we explore more data enhancement methods to extend the application of the model to diverse wood defect scenarios to improve the robustness and adaptability of the model. Moreover, although there is still room for improvement in addressing background interference and detail reconstruction, the model performs well in wood few-shot detection, but optimization in background interference suppression and detail reconstruction will be a key direction for future research. Finally, we will consider applying the model to other computer vision tasks facing data scarcity problems to verify its generality and scalability.

Author contributions

X.T. planned the study and drafted the manuscript. Z.L. provided the relevant equipment and funding support. X.T. and M.Q. drafted the manuscript. F.L. was involved in writing the experimental code for the computational analysis. J.Y., H.X. and W.D carried out the data collection and pre-processing. This paper was written with input from all authors.

Funding

This work was funded by the Key R&D Program Project of Yunnan Province: Key Technology Research and Application Demonstration of Public Rail Intermodal Intelligent Logistics Park, and supported by Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects (grant NO. 202501AT070245).

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xingyu Tong and Mingming Qin contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Zhang, H. et al. Towards high quality object detection via dynamic training. in Computer Vision – ECCV 2020 260–275 (Springer, 2020). 10.1007/978-3-030-58555-6_16

- 2.Chen, K. et al. Hybrid task cascade for instance segmentation. in. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 4969–4978 (IEEE, Long Beach, CA, USA). (2019). 10.1109/CVPR.2019.00511

- 3.Jiménez-Guarneros, M., Fuentes-Pineda, G. & Cross-Subject EEG-Based emotion recognition via semisupervised multisource joint distribution adaptation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas.72, 1–11 (2023).37323850 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma, C., Mi, J., Gao, W. & Tao, S. SSGAN: A semantic Similarity-Based GAN for Small-Sample image augmentation. Neural Process. Lett.56, 1–21 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao, H. et al. A deep convolutional generative adversarial Networks-Based method for defect detection in small sample industrial parts images. Appl. Sci.12, 6569 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Blaere, R. et al. SmartWoodID-an image collection of large end-grain surfaces to support wood identification systems. Database (Oxford) 034 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.He, X., Luo, Z., Li, Q., Chen, H. & Li, F. DG-GAN: A high quality defect image generation method for defect detection. Sensors23, 5922 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Figueroa-Mata, G., Mata-Montero, E., Valverde-Otárola, J. C. & Arias-Aguilar, D. Zamora-Villalobos, N. Using deep learning to identify Costa Rican native tree species from wood cut images. Front. Plant. Sci.13, 789227 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghosh, K. et al. The class imbalance problem in deep learning. Mach. Learn.113, 4845–4901 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang, L., Zuo, L., Du, Y. & Zhen, X. Learning to adapt with memory for probabilistic Few-Shot learning. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol.31, 4283–4292 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ho, S., Liu, M., Gao, S. & Gao, L. Learning to learn for few-shot continual active learning. Artif. Intell. Rev.57, 1–21 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koch, G. R. & [PDF] Siamese neural networks for one-shot image recognition | semantic scholar. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Siamese-Neural-Networks-for-One-Shot-Image-Koch/f216444d4f2959b4520c61d20003fa30a199670a

- 13.Feng, J., Cui, J., Wei, Q., Zhou, Z. & Wang, Y. A classification model of legal consulting questions based on Multi-Attention prototypical networks. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst.14, 1–9 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang, Y., Yao, Q., Kwok, J. & Ni, L. M. Generalizing from a few examples: A survey on few-shot learning. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1904.05046v3 (2019).

- 15.Finn, C., Abbeel, P. & Levine, S. Model-agnostic meta-learning for fast adaptation of deep networks. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1703.03400v3 (2017).

- 16.Hospedales, T. M., Antoniou, A., Micaelli, P. & Storkey, A. J. Meta-learning in neural networks: A survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1–1. 10.1109/TPAMI.2021.3079209 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Gui, S. et al. Model compression with adversarial robustness: A unified optimization framework. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.03538v3 (2019).

- 18.Antipov, G., Baccouche, M. & Dugelay, J. L. Face aging with conditional generative adversarial networks. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1702.01983v2 (2017).

- 19.Goodfellow, I. J. et al. Generative adversarial networks. arXiv.org (2014). https://arxiv.org/abs/1406.2661v1

- 20.Tsai, Y. H. H. et al. Multimodal transformer for unaligned multimodal language sequences. in 6558–6569 (2019). 10.18653/v1/P19-1656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Elnaggar, A. et al. ProtTrans: toward Understanding the Language of life through Self-Supervised learning. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell.44, 7112–7127 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li, Q., Gkoumas, D., Lioma, C. & Melucci, M. Quantum-inspired multimodal fusion for video sentiment analysis. Preprint at (2021). 10.48550/ARXIV.2103.10572

- 23.Hu, R. & Singh, A. UniT: multimodal multitask learning with a unified transformer. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2102.10772v3 (2021).

- 24.Kang, B. et al. Few-shot object detection via feature reweighting. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1812.01866v2 (2018).

- 25.Fan, Q., Zhuo, W., Tang, C. K. & Tai, Y. W. Few-shot object detection with attention-RPN and multi-relation detector. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1908.01998v4 (2019).

- 26.Wang, Y. X., Ramanan, D. & Hebert, M. Meta-learning to detect rare objects. in IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 9924–9933 (IEEE, Seoul, Korea (South), 2019). 10.1109/ICCV.2019.01002

- 27.Yan, X. et al. Meta R-CNN: Towards general solver for instance-level low-shot learning. in. IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 9576–9585 (IEEE, Seoul, Korea (South), 2019). 10.1109/ICCV.2019.00967

- 28.Wang, X., Huang, T. E., Darrell, T., Gonzalez, J. E. & Yu, F. Frustratingly simple few-shot object detection. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.06957v1 (2020).

- 29.Sun, B., Li, B., Cai, S., Yuan, Y. & Zhang, C. F. S. C. E. Few-shot object detection via contrastive proposal cncoding. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2103.05950v2 (2021).

- 30.Chen, H., Wang, Y., Wang, G. & Qiao, Y. LSTD: A low-shot transfer detector for object detection. AAAI 32, (2018).

- 31.Ren, S., He, K., Girshick, R., Sun, J. & Faster, R-C-N-N. Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst.28, (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.