Abstract

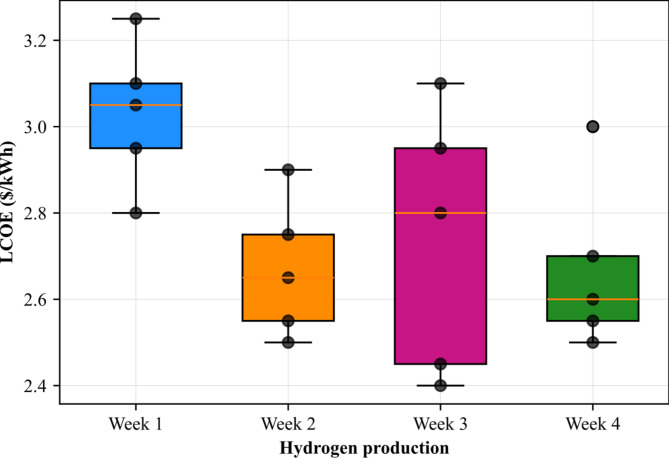

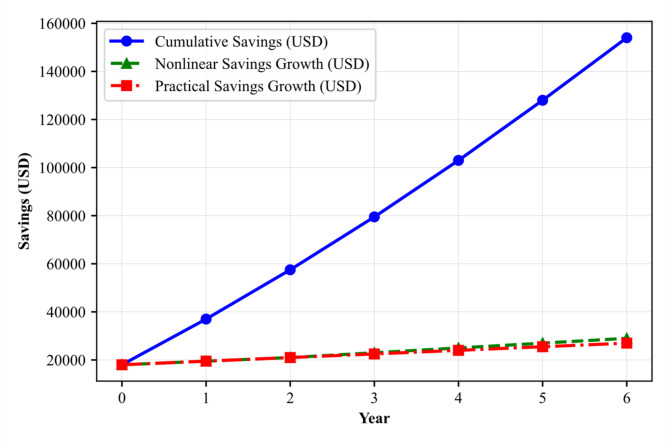

This study is focusing on the techno-economic optimization of hybrid renewable energy systems and the energy. The system integrates geothermal, wind, and solar sources for sustainable hydrogen production its important. The objective is to maximize energy efficiency, reduce operational costs, and ensure stable energy delivering. A simulation-based framework is used for analyse system behaviour under various environmental conditions it helps. The scope includes defining parameter, sensitivity analysis, and optimization using iterative algorithms which are complex. Time-step simulations evaluating energy dynamics help to and performance trade-offs, which is necessary for understanding. The proposed hybrid system achieves 78.5% energy efficiency and 64.3% exergy efficiency, and this is good. It produces 500 kg of hydrogen daily with an LCOE of $0.085 per kWh, which is quite low. Sensitivity results show that a 15% increase in wind speed improves output by 10%, and this is significant. A 20% drop in solar irradiance reduces output by 8%, which is not good. Geothermal contributes 40% of the total energy share, with wind and solar supplying 35% and 25%, respectively, and this shows balance. Optimization improves hydrogen production efficiency by 12% and leads to a six-year payback period, which is reasonable. The system shows resilience under load changes, supporting its robustness that is impressive. The findings validate the system’s scalability and economic potential, which is promising for future. Future work will explore advanced storage and real-time adaptive control.

Keywords: Techno-economic optimization, Hybrid renewable energy systems, Hydrogen production, Energy efficiency, Exergy efficiency, Levelized cost of energy, Sustainability

Subject terms: Engineering, Electrical and electronic engineering

Introduction

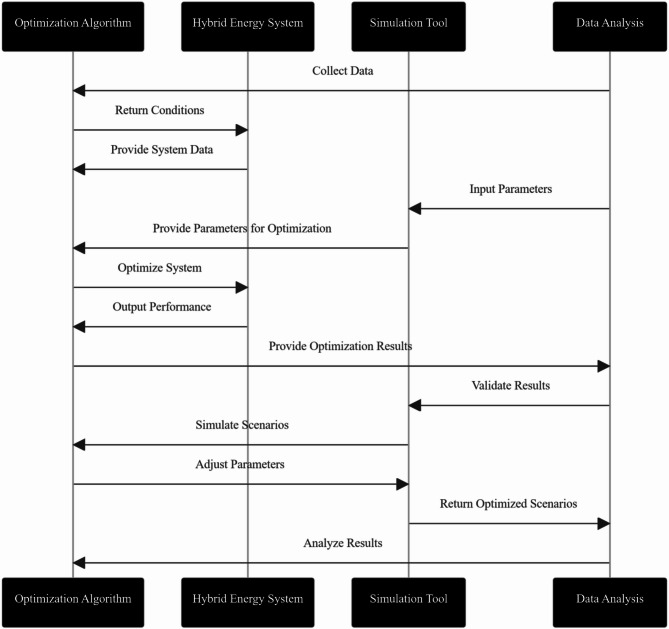

Hybrid renewable energy systems (HRES) combine various renewable sources. These systems optimize energy production by integrating different resources. Wind, solar, and geothermal sources enhance energy reliability and sustainability. The techno-economic optimization process ensures both efficiency and economic viability. This process balances technical performance with cost-effectiveness as in Fig. 1. Optimizing both aspects helps to improve system sustainability and scalability. Increasing global energy demands make sustainable solutions crucial. Renewable energy systems address the need for sustainable energy. Hybrid systems provide a reliable alternative to fossil fuels. Energy production from renewable sources often faces variability challenges. These challenges include fluctuating energy generation based on weather. Hybrid systems mitigate this issue through resource diversification. Hybrid renewable systems help stabilize energy supply and demand. Combining multiple energy sources ensures consistent energy generation. These systems offer reliability even with fluctuating resource availability. Hydrogen production from surplus renewable energy offers a sustainable solution. It serves as an energy carrier for future needs. Hydrogen production increases the overall efficiency of hybrid systems. Technological advancements allow better integration of renewable energy sources. Wind, solar, and geothermal technologies provide flexible energy options. These innovations maximize the efficiency of hybrid systems. Hybrid systems reduce greenhouse gas emissions significantly. They contribute to cleaner energy production and environmental sustainability. Reducing emissions is a critical benefit of hybrid systems. Energy storage enhances hybrid system reliability and efficiency. Hybrid systems incorporate energy storage to manage supply and demand. Storage ensures energy availability even during fluctuating resource conditions. Exergy efficiency is a critical aspect of system optimization. It minimizes energy waste by maximizing useful energy output. Exergy efficiency improves overall system performance and reduces operational costs. Economic considerations are essential when optimizing hybrid systems. Financial analysis ensures systems are both cost-effective and sustainable. Economic feasibility plays a significant role in hybrid system optimization. The levelized cost of energy (LCOE) is a vital metric. It allows comparison of the cost-effectiveness of various technologies. LCOE helps determine the economic viability of hybrid systems. Previous studies have explored techno-economic optimization of HRES. These studies provide insights into the challenges and benefits. They highlight strategies for improving system performance and cost-effectiveness.

Fig. 1.

Systematic approach of techno-economic optimization in hybrid energy systems.

Traditional energy systems have environmental and economic drawbacks. Hybrid systems offer cleaner alternatives to fossil-fuel-based generation. They ensure greater reliability compared to conventional systems. Evaluating system performance requires considering environmental factors. Key factors include wind speed, solar irradiance, and geothermal heat flow. These factors impact the overall energy production of hybrid systems. Variability in renewable resources affects system performance significantly. Sensitivity analysis helps evaluate how resource fluctuations impact output. Understanding these variations improves system reliability and optimization. Dynamic simulations help predict system behavior under various conditions. These simulations evaluate system performance over different time frames. Simulating various scenarios ensures hybrid systems operate optimally. Hybrid systems can balance multiple energy resources effectively. Optimizing energy production across resources ensures system reliability. Integration of resources is key to maximizing overall energy output. Sensitivity analysis evaluates system resilience against external factors. Resource fluctuations and environmental changes are accounted for. This analysis helps improve hybrid system performance under variable conditions. Energy flows must be carefully modeled in hybrid systems. Modeling energy flows helps integrate multiple subsystems efficiently. Optimizing these flows ensures that energy production meets demand consistently. Economic and energy efficiency often involve trade-offs. Systems must balance cost-effectiveness with performance outcomes. Identifying the right trade-off improves system viability and profitability. Hybrid renewable systems face several adoption barriers. These include technological, financial, and operational challenges. Overcoming these barriers is essential for wider system implementation. Optimization algorithms improve the evaluation of hybrid systems. These algorithms predict system performance and optimize energy production. They also help minimize costs and maximize efficiency. Cost-benefit analysis assesses the financial feasibility of hybrid systems. It compares the potential benefits with system installation costs. This analysis provides critical information for decision-making. Balancing energy production and hydrogen storage is essential. Effective storage strategies help optimize hydrogen production and usage. Hybrid systems rely on storage for efficient energy utilization. Hydrogen plays an important role in hybrid renewable systems. It serves as a clean energy carrier for storage. Integrating hydrogen production enhances system sustainability and efficiency. Time-step simulations provide valuable long-term system predictions. These simulations assess system performance under different operating conditions. Simulating various scenarios ensures energy production remains optimal. Current trends show significant growth in hybrid renewable systems. Technological advancements continue to improve system performance and efficiency. Hybrid systems are becoming increasingly important for sustainable energy. Techno-economic analysis is key in optimizing renewable energy systems. It integrates technical, economic, and environmental factors for decision-making. This analysis helps balance performance, cost, and environmental sustainability. The optimization methodology maximizes the energy output of hybrid systems. It integrates resource utilization and economic considerations into the design. The methodology helps ensure hybrid systems are both reliable and cost-effective.

Related works

This research focuses on the techno-economic optimization of hybrid renewable systems. The study evaluates both technical and economic aspects for sustainable solutions1. It highlights the importance of hydrogen generation through hybrid systems. Strategies for its viability as a sustainable energy source are assessed2. The article discusses the optimization of hybrid systems for islands. It emphasizes off-grid solutions and renewable energy feasibility in remote areas3. Another study explores hybrid systems using the waste-to-X principle. It assesses industrial applications for large-scale energy solutions4. Research integrating electric vehicle stations with hybrid systems improves performance. Multi-objective optimization enhances both economic and technical outcomes5. A comparative study evaluates different hybrid systems. The goal is to identify the most efficient and cost-effective solutions6. Focusing on remote Bangladesh, the research explores solar-wind hybrid systems. This enhances reliability and cost-efficiency for off-grid solutions7. Hybrid grid configurations in Turkey are analyzed for optimization. Various techniques are used to support grid integration and performance8. The importance of hybrid systems for rural electrification in Bangladesh is explored. This focuses on environmentally friendly energy solutions tailored to local needs9. A techno-economic analysis examines hybrid energy systems across applications. The goal is to enhance reliability and reduce costs10. Hydrogen production for refueling stations is studied through optimization. Renewable source viability and scalability are assessed for hydrogen production11. The paper also analyzes hybrid systems combining photovoltaics, diesel, and battery storage. It provides insights into energy optimization for rural electrification12. Hybrid systems incorporating wind, PV, and fuel cells are explored. The focus is on improving energy generation efficiency and sustainability13. Techno-economic perspectives on grid-connected systems for urban applications are presented. The goal is to reduce costs and improve energy access14. The integration of IoT technology optimizes hybrid renewable systems. Advanced dispatch strategies improve system reliability and performance15. A hybrid system using wind, solar, and thermoelectric energy is optimized. The focus is on performance, sustainability, and system integration16. Additionally, the feasibility of hydrogen energy storage is evaluated. This enhances sustainability and performance of hybrid systems17. Techno-economic optimization using pre-feasibility analysis tools improves performance. The emphasis is on energy storage and system sustainability18. A multi-energy storage hybrid system is evaluated using HOMER software. The goal is to optimize both technical and economic factors19. Research on remote area hybrid systems emphasizes economic and environmental benefits. Off-grid electrification techniques are optimized for sustainable energy solutions20. The optimization of stand-alone hybrid systems is explored. A two-stage nested approach provides cost-effective energy solutions22. Component degradation in hybrid photovoltaic-wind-battery systems is studied. The aim is to improve system lifetime and reduce costs23. The techno-economic assessment of hybrid storage systems is explored. It integrates renewable energy with storage to optimize system efficiency24. A case study on hybrid renewable systems for health clinics is presented. It highlights cost-effective and reliable power solutions for healthcare25. Optimal sizing of hybrid systems is analyzed. A multidimensional approach supports green energy growth in Cameroon26. Techno-economic modeling of hybrid microgrids explores rural electrification. Optimization algorithms like HOMER improve energy access for underserved areas27. Stochastic optimization of hybrid systems integrates solar, wind, and hydrokinetic resources. This improves reliability and reduces operational costs28. A multiscale approach optimizes off-grid systems for rural electrification. It enhances design and financial feasibility for remote areas29. Comparative studies on standalone and grid-tied systems are presented. The focus is on improving performance and cost-efficiency in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa30. Techno-economic and environmental analyses of hybrid PV/wind systems are applied. These are assessed for campus-based energy solutions with sensitivity analysis31. Hybrid microgrid systems in residential Bangladesh areas are analyzed. The aim is to optimize energy generation for reliability and cost-effectiveness32. Machine learning models are used to optimize hybrid renewable systems. The focus is on improving performance through environmental and economic factors33. Off-grid hybrid systems for green hydrogen production are evaluated. Multi-criteria decision-making assesses various configurations for sustainable solutions34. Artificial rabbit algorithms optimize hybrid PV/wind/fuel cell systems. The goal is to improve energy generation while reducing costs35. Techno-socio-enviro-financial perspectives are used to optimize stand-alone systems. Red-tailed hawk algorithms enhance system design for sustainability36. A predictive technique for sizing and managing hybrid systems is used. It helps optimize renewable energy solutions for large-scale implementation37. Socio-techno-economic-environmental factors are integrated into sizing hybrid systems. This improves both energy sustainability and economic feasibility38. Multi-criteria decision-making approaches optimize hybrid systems for decentralized power. Green hydrogen production is enhanced by technical, economic, and environmental factors39. Optimization of hybrid PV/wind/battery/diesel systems for isolated areas improves reliability. Costs are reduced for off-grid energy solutions40. Hybrid-renewable pumped hydropower systems in Saudi Arabia are assessed. The focus is on large-scale, sustainable energy applications41. A hybrid microgrid-hydrogen system is optimized for fuel production. Renewable energy integration is key for sustainable fuel solutions42. Energy storage configurations for renewable systems are optimized. This analysis improves performance and reduces costs43. Hybrid power system configurations are analyzed for cost-effective solutions. Technical and economic factors are considered for sustainability44. Techno-economic optimization for isolated hybrid microgrids is studied. This focuses on electrification in Aswan city using hybrid systems45. The comparison of nuclear and hybrid systems for energy production is presented. It identifies optimal renewable energy configurations in Mersin, Turkey46. Hybrid systems for rural Morocco combine PV, wind, and pumped hydropower. The aim is to improve energy access and sustainability47. The planning of off-grid hybrid systems for wetland areas is optimized. This study offers insights into energy solutions for developing regions48. Techno-economic performance evaluation of hybrid energy systems in Bahia, Brazil, is presented. The focus is on practical implementation and economic feasibility49. Modeling and techno-economic assessment of power systems is explored. Clean energy solutions, including green hydrogen production, are optimized for environmental impact50. The work in51 actually goes into discussing the integrated and very complex techno-economic-environmental design for the off-grid microgrids. The study in52 mainly focuses on the techno-economic optimization of hybrid solar systems combined with additional storage. In53, a detailed review of the different hybrid renewable energy systems is actually presented, covering the relevant technical aspects. The research in54 carefully explores the optimal sizing for hybrid systems using a broad socio-techno-economic-environmental view, which is quite important. The work in55 particularly emphasizes optimizing hybrid systems for rural areas with a very thorough environmental evaluation. In56, load scheduling could potentially improve microgrid performance, but it’s not included, mainly due to resilience focus. The study in57 incorporates load-source management to improve the rural electrification goal and also enhance sustainability. The research in58 specifically focuses on optimizing hybrid systems for villages, addressing the community’s needs and other factors. The paper in59 presents the case study, which focuses on hybrid power generation for local communities, contributing to their needs. The work in60 thoroughly explores hydrogen storage systems, which can improve system performance and sustainability, focusing also on the environmental impacts. Several research gaps in hybrid renewable energy systems are identified:

Current optimization techniques rely on static energy demand. Future research should incorporate dynamic, real-time load forecasting models. These models must address the variability in energy consumption patterns.

Existing studies overlook the effects of system degradation. Future research must factor in degradation rates to estimate long-term costs. Incorporating these factors will help improve the accuracy of economic assessments.

The potential of hydrogen storage is underexplored in hybrid systems. Research should explore its role in improving energy storage efficiency. Hydrogen can enhance the flexibility of energy systems but needs further investigation.

Most models focus on capital investment without considering flexibility. Future studies must address the importance of system adaptability in optimization. This will help tackle uncertainties in energy generation and consumption.

The social impact and acceptance of these systems are overlooked. Research should focus on understanding the public’s concerns and awareness. Social and cultural factors can influence the success of hybrid systems.

Addressing these gaps will enable the development of more efficient and sustainable hybrid renewable energy systems. The research focuses on optimizing hybrid renewable energy systems. The main objectives of this particular study, which is focused on investigating renewable energy systems, are:

To attempt to optimize hybrid renewable systems that are integrating a variety of renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, and geothermal sources, in order to achieve the maximum possible efficiency and cost-effectiveness, to the greatest extent possible, and.

To thoroughly evaluate, in a detailed manner, the impact, in terms of both performance and sustainability, of storage technologies, along with load forecasting, on the overall performance and functionality of the entire system.

The overall goal of this study is to provide, in a manner that can be scaled up, reliable, dependable, and economically feasible energy solutions for off-grid locations and remote applications, in a way that meets their energy needs, to a great degree. The main contributions are as follows:

To optimize hybrid systems for cost savings that includes minimizing both capital and operational expenditures while ensuring reliability.

To enhance the integration of renewable energy sources. Wind, solar, and battery systems are considered for maximum sustainability.

To improve energy storage methods for hybrid systems. Battery and hydrogen storage technologies will be explored for increased efficiency.

By addressing these objectives, the research contributes to the advancement of hybrid energy systems. It offers solutions for energy management, sustainability, and economic feasibility in the context of renewable energy.

The novelty of this research lies in its integrated approach to optimizing hybrid renewable systems with a strong focus on hydrogen production, cost-effectiveness, and system adaptability. Unlike existing studies, this work combines real-time sensitivity analysis with techno-economic modeling to enhance energy management and storage performance in dynamic environments. This is not like other studies, which often overlook the importance of real-time data. This approach is unique and very innovative, which is why it is important to highlight it.

The research article is structured to ensure a comprehensive and logical progression of ideas. Each section plays a crucial role in the overall flow of the study. The organization is as follows, Introduction and Background section introduces the topic and its relevance. It establishes the context for hybrid renewable systems in sustainable energy solutions. In related works section a thorough review of existing literature is presented. It highlights previous research findings and identifies gaps in the current knowledge. “Design and optimization of hybrid renewable energy systems” outlines the methodologies employed in the study. It details the optimization techniques, system models, assumptions, and performance evaluation criteria. “Proposed techno-economic optimization of hybrid renewable energysystems” proposes a techno-economic optimization approach. It focuses on cost-effectiveness and sustainability in hybrid renewable energy systems. Results and discussion section presents and interprets the findings of the study. It discusses the optimization results, cost savings, efficiency, and sustainability of the proposed hybrid systems. The conclusion summarizes key findings and implications. It also suggests potential future research directions for further development and refinement.

Design and optimization of hybrid renewable energy systems

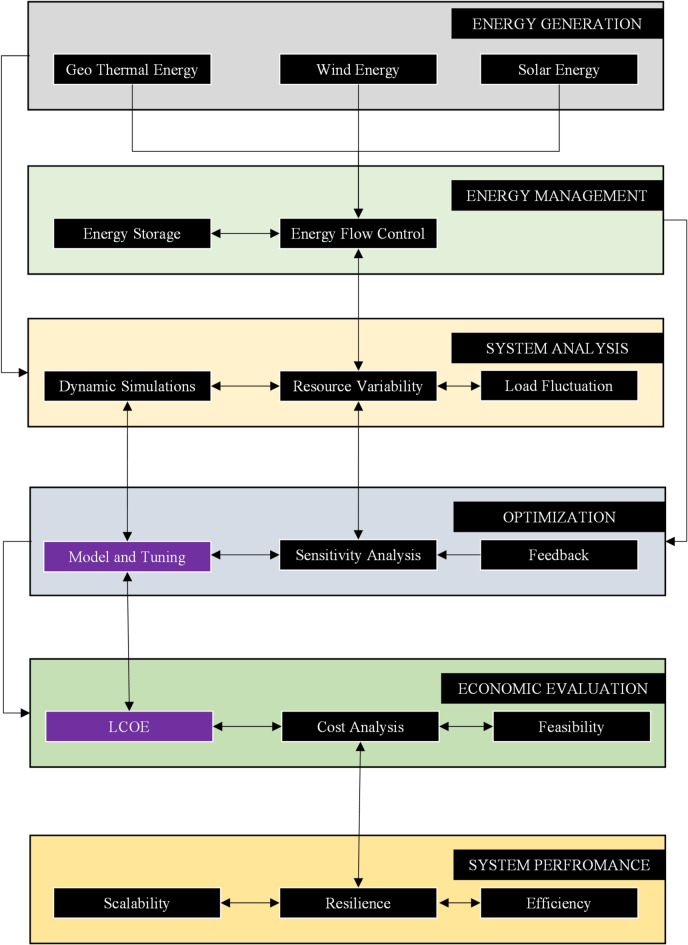

Figure 2 illustrates a schematic representation of a proposed hybrid renewable energy system. The system integrates wind, solar, and geothermal energy sources with hydrogen production units. This diagram provides a comprehensive overview of how these components work together. Each component is designed to optimize energy generation, storage, and distribution efficiently. Wind Energy represents the wind turbines used for energy generation. These turbines capture kinetic energy from wind and convert it into electricity. Solar Energy represents solar photovoltaic panels that harness solar radiation for energy. The panels convert sunlight directly into electrical energy, complementing wind power. Geothermal Energy represents geothermal energy converters that use heat from the earth. These converters extract heat from deep underground to generate electricity. Hydrogen Production represents units that convert surplus energy into hydrogen. This hydrogen is stored as a clean energy carrier for future use. System Simulation represents the simulation tools used to model the system’s energy flow. These tools simulate system behavior under different conditions to predict energy performance. Energy Storage represents batteries or other systems used for storing energy. These systems manage the surplus energy generated during peak periods for later use. Optimization Model represents the algorithm that optimizes system parameters.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of the proposed hybrid renewable energy system integrating wind, solar, and geothermal energy sources with hydrogen production units.

It adjusts key factors like cost, efficiency, and scalability to achieve an ideal balance. Sensitivity Analysis represents the evaluation of how varying input factors impact system performance. These factors include variables like wind speed and solar irradiance. Dynamic Simulations represent simulations assessing system performance over time. These simulations account for different time-step variations in resource availability. Resource Variability represents the analysis of fluctuations in renewable resource availability. These fluctuations can impact energy production and system stability. Economic Analysis represents the evaluation of the system’s cost-effectiveness. It considers both the benefits and feasibility of the system from an economic standpoint. Cost-Benefit Analysis represents the detailed financial analysis of the hybrid system. This analysis compares costs against the expected benefits to determine system viability. System Reliability represents the assessment of the system’s stability. It evaluates how well the system performs under varying environmental conditions. Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) represents the cost calculation used to measure the system’s cost-effectiveness. It accounts for the total cost per unit of energy over the system’s lifetime. Optimization Feedback represents the iterative optimization process. This process adjusts system parameters based on simulation results to improve performance. Energy Efficiency represents the measurement of energy quality and efficiency. It helps identify areas where energy waste can be minimized. Hydrogen Storage represents the storage units that store hydrogen produced from surplus energy. These units ensure clean energy is available when needed. Final System Design represents the overall optimized design after all analyses. This design integrates all subsystems to work harmoniously for optimal performance. Performance Evaluation represents the final assessment of the system’s overall efficiency. It considers energy output, operational stability, and performance under different conditions. Renewable Energy Integration represents the process of combining wind, solar, and geothermal energy. This integration ensures a balanced energy mix that minimizes variability. Energy Flow Control represents the system responsible for managing the energy across subsystems. This block ensures that energy is efficiently distributed throughout the system. Energy Efficiency represents the ongoing assessment of system performance improvements. It identifies areas for further optimization to enhance overall efficiency. Load Fluctuations represents the system’s ability to adapt to changes in energy demand and supply. It ensures stability during peak or low-demand periods. Optimization Tuning represents the fine-tuning of optimization algorithms. This process adjusts parameters to achieve the best system performance. Dynamic Adjustment represents real-time changes to the system based on simulation data. These adjustments ensure the system adapts to varying conditions efficiently. Energy Output represents the total energy generated by the system. This output includes energy from renewable resources and hydrogen production. System Performance represents the overall evaluation of the system’s efficiency and stability. It measures the success of all optimization processes and operational goals. Scalability & Practicality represents the system’s potential to be scaled for larger applications. It evaluates the feasibility of applying this system to various environments. System Resilience represents the system’s ability to maintain its performance despite resource variability. This ensures consistent energy production and system reliability. Finally, Economic Feasibility represents the financial analysis of the hybrid system. This analysis ensures that the system is economically viable in real-world applications.

The performance of hybrid renewable energy systems, which combine wind, solar, and geothermal energy sources, is influenced by various environmental conditions. These factors directly impact each technology’s energy generation potential and shape the techno-economic optimization needed for sustainable energy solutions. Table 1 presents the parameters essential for assessing wind turbines, solar panels, and geothermal systems, helping optimize their performance. Understanding these parameters is key for designing efficient and cost-effective hybrid systems in the transition to renewable energy. Wind speed plays a significant role in wind turbine performance. Wind turbines operate most efficiently at wind speeds between 5 and 15 m/s. At this range, turbines capture wind energy effectively, converting it into electricity. Wind speeds below this range produce insufficient energy, while higher speeds can stress turbines. Wind direction also impacts turbine performance, as turbines need to face prevailing winds. Proper turbine placement ensures they consistently capture wind energy, optimizing performance. Wind shear, or changes in wind speed with altitude, also affects energy capture. Wind shear values of 0.1–0.3 indicate favorable conditions for tall turbines, which can access higher wind speeds. These conditions allow turbines to generate more power, improving efficiency. Solar irradiance refers to the amount of solar energy received per unit area. It ranges from 400 to 1000 W/m2, depending on location and weather conditions. Areas with high solar irradiance are ideal for solar energy generation. Higher irradiance levels increase the potential for energy capture by solar panels. Solar panel efficiency depends on how effectively they convert solar radiation into electricity. With efficiencies ranging from 10 to 22%, more efficient panels produce more power. The solar angle, or the angle of incident sunlight, affects solar energy absorption. Solar angles of 15° to 75° ensure maximum solar energy absorption across varying latitudes. Solar panels must be oriented correctly to optimize power generation at different times. Geothermal energy relies on heat extracted from the Earth’s interior. Geothermal heat flow measures how much heat can be extracted for energy. This varies from 50 to 150 mW/m2 depending on geological conditions. Areas with higher heat flow are better for geothermal energy extraction. However, geothermal depth affects the extraction process; deeper resources are harder to access. Geothermal depths typically range from 500 to 3000 m, and deeper reservoirs are costlier to exploit. Geothermal conversion efficiency refers to how well heat is converted into electricity. A conversion efficiency of 10–30% determines how effectively energy is extracted. Higher conversion efficiency results in more usable power from geothermal resources.

Table 1.

Key environmental factors for hybrid energy system optimization.

| Condition | Description | Value range | Unit | Source/reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wind speed | Wind speed impacting energy generation | 5 to 15 m/s | meters per second (m/s) | 1,7 |

| Solar irradiance | Solar energy received per unit area | 400 to 1000 W/m2 | watts per square meter (W/m2) | 3,8 |

| Geothermal heat flow | Heat energy extracted from Earth’s interior | 50 to 150 mW/m2 | milliwatts per square meter (mW/m2) | 4,16 |

| Ambient temperature | Temperature affecting system efficiency | 10 °C to 35 °C | Celsius (°C) | 6,9 |

| Relative humidity | Water vapor in the air affecting performance | 30–80% | Percentage (%) | 9,10 |

| Precipitation | Rainfall or snowfall affecting energy generation | 0 to 200 mm/month | millimeters per month (mm/month) | 11,17 |

| Solar angle | Angle of solar radiation hitting the surface | 15° to 75° | Degrees (°) | 6,12 |

| Wind direction | Direction of wind affecting turbine placement | North, South, East, West | Direction (°) | 1,7 |

| Geothermal depth | Depth of geothermal energy resources | 500 to 3000 m | meters | 4,5 |

| Cloud cover | Percentage of sky covered by clouds | 20–80% | Percentage (%) | 6,13 |

| Wind turbine efficiency | Conversion efficiency of wind energy to electricity | 25–45% | Percentage (%) | 1,6 |

| Solar panel efficiency | Conversion efficiency of solar radiation to electricity | 10–22% | Percentage (%) | 8,14 |

| Geothermal conversion efficiency | Efficiency of geothermal energy conversion | 10–30% | Percentage (%) | 4,16 |

| Air density | Density of air impacting energy capture | 1.1 to 1.3 kg/m3 | kilograms per cubic meter (kg/m3) | 5,7 |

| Ground reflectivity (Albedo) | Reflectivity affecting solar panel output | 0.2 to 0.6 | Dimensionless (0 to 1) | 8,12 |

| Turbulence intensity | Fluctuations in wind speed affecting turbines | 0.05 to 0.15 | Dimensionless | 1,13 |

| Solar temperature coefficient | Effect of temperature on solar panel efficiency | − 0.3% to − 0.5%/°C | Percentage per °C | 8,9 |

| Wind shear | Change of wind speed with height | 0.1 to 0.3 | Dimensionless | 5,7 |

| Surface roughness | Roughness of land surface affecting wind flow | 0.01 to 0.05 m | meters | 6,10 |

| Heat transfer coefficient | Rate of heat transfer in geothermal systems | 3 to 5 W/m K | watts per meter per Kelvin (W/m K) | 5,16 |

| Geothermal well flow rate | Rate of geothermal fluid extraction | 20 to 100 l/s | liters per second (l/s) | 4,16 |

Ambient temperature directly impacts the efficiency of renewable energy systems. Temperatures between 10 °C and 35 °C are optimal for system performance. Extreme temperatures may reduce the efficiency and lifespan of systems. Relative humidity, which ranges from 30 to 80%, also affects system efficiency. High humidity levels can reduce the air density, impacting wind turbine efficiency. For solar panels, humidity increases cloud cover, reducing sunlight exposure. Precipitation, including rain or snow, obstructs solar irradiance and wind turbine movement. Areas experiencing 0 to 200 mm/month of precipitation may experience system downtime. Excessive precipitation results in lower energy production, reducing system performance. Cloud cover reduces solar energy generation by blocking sunlight. Areas with 20–80% cloud coverage face less efficient solar production. More cloud coverage means reduced solar irradiance, thus lowering power output. Ground reflectivity, or albedo, refers to the amount of sunlight reflected onto solar panels. Albedo values between 0.2 and 0.6 increase solar panel energy capture. Higher reflectivity results in more sunlight being directed to the panels. Turbulence intensity measures fluctuations in wind speed that affect wind turbines. With values between 0.05 and 0.15, turbulence affects turbine efficiency and performance. Excessive turbulence can reduce energy capture and increase mechanical stress on turbines. Air density impacts the energy capture potential of wind turbines. A higher air density allows turbines to generate more power. The typical range for air density is between 1.1 and 1.3 kg/m2. In areas with denser air, turbines can extract more energy from the wind. Surface roughness, or land irregularity, also affects wind flow near the ground. A surface roughness value between 0.01- and 0.05-m influences wind turbine performance. Rougher surfaces create more turbulence, potentially reducing turbine efficiency. The heat transfer coefficient defines how efficiently geothermal systems extract heat. Values ranging from 3 to 5 W/m K indicate effective heat transfer for geothermal systems. Higher heat transfer coefficients improve energy extraction, boosting geothermal power generation. Geothermal well flow rate measures the volume of geothermal fluid extracted. A flow rate between 20 and 100 l per second is typical. Higher flow rates allow geothermal systems to extract more energy, increasing output. These factors—wind speed, solar irradiance, geothermal heat flow, temperature, and humidity—are crucial for optimizing renewable energy systems. By selecting appropriate sites based on these parameters, developers can design efficient systems. Maximizing energy generation while minimizing costs requires careful consideration of each parameter. Hybrid systems that integrate wind, solar, and geothermal technologies can achieve higher efficiency. By leveraging these renewable resources together, hybrid systems offer a more sustainable energy solution.

Proposed techno-economic optimization of hybrid renewable energy systems

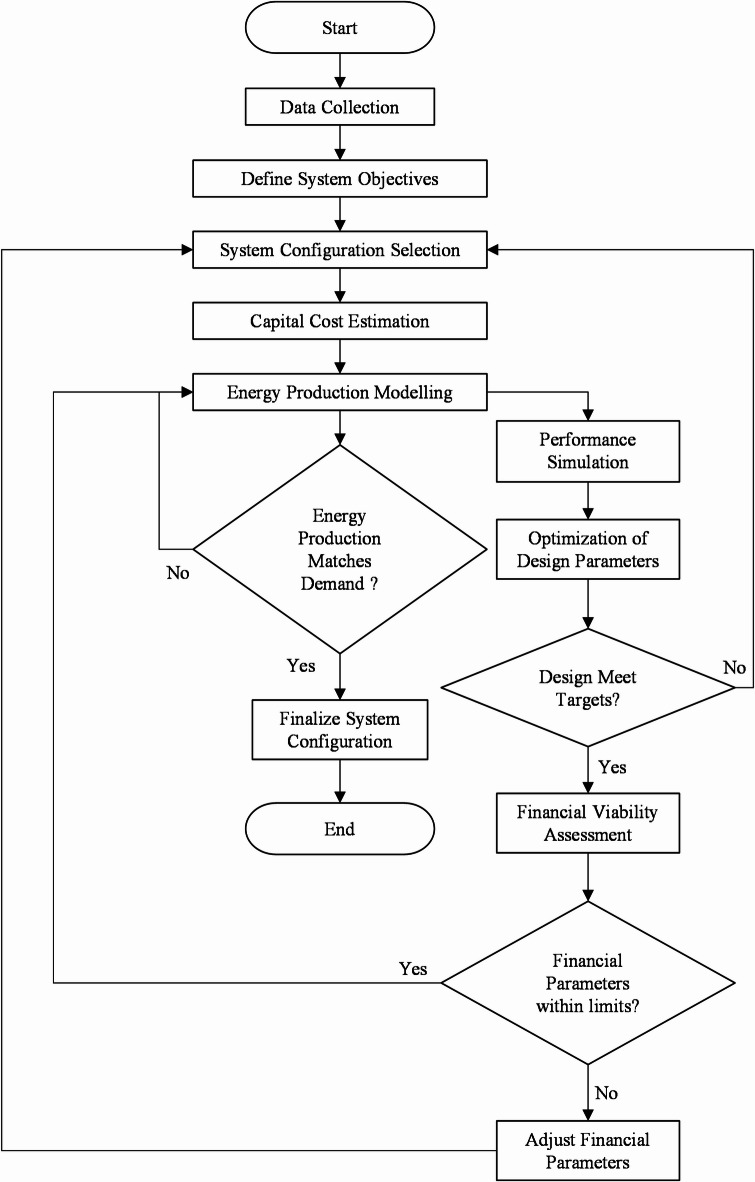

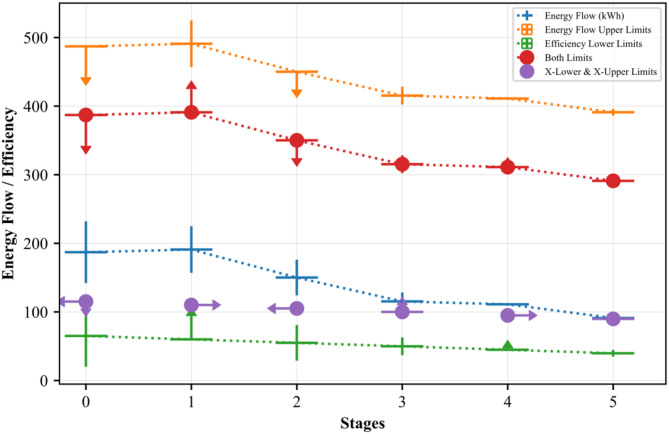

Figure 3: Flowchart for the techno-economic optimization process of the hybrid renewable energy system outlines a comprehensive sequence of steps for optimizing hybrid renewable energy systems, integrating wind, solar, and geothermal resources. The process begins with Data Collection, which is crucial for gathering all necessary data that influences system design. The collected data spans environmental conditions, resource availability, demand forecasts, and economic parameters, all of which form the basis for subsequent decisions. Without accurate and comprehensive data, the optimization process cannot proceed effectively, as the system’s performance and financial feasibility directly depend on this information. Environmental data, such as wind speed and solar irradiance, inform energy production estimates, while economic data ensures the optimization aligns with financial goals, helping identify the most cost-effective solution. Moreover, understanding demand patterns ensures the designed system can meet load requirements effectively, without excess production or deficiencies in energy supply. The first step, Data Collection, involves gathering environmental, resource, demand, and economic data to inform the system design. This data provides the foundation for accurately modeling energy production, system performance, and financial viability. In this step, wind speed, solar irradiance, geothermal heat flow, demand forecasts, and economic parameters like fuel costs and capital costs are collected. Accurate data on wind speed and solar radiation ensures that energy production models reflect real-world conditions, while demand forecasts inform the design of the energy system to meet varying loads. Without comprehensive data, optimization and financial assessments cannot be accurately conducted.

Fig. 3.

Flow chart for the techno-economic optimization process of the hybrid renewable energy system.

For wind energy, the equation

| 1 |

. is used, where  is the energy generated from wind (kWh),

is the energy generated from wind (kWh),  represents the air density (kg/m3), A is the area swept by the turbine blades (m2),

represents the air density (kg/m3), A is the area swept by the turbine blades (m2),  is the power coefficient of the turbine (dimensionless), and V is the wind velocity (m/s). This equation calculates the energy generation from wind, which is influenced by factors such as air density, wind speed, and turbine efficiency. For solar energy, the Eq.

is the power coefficient of the turbine (dimensionless), and V is the wind velocity (m/s). This equation calculates the energy generation from wind, which is influenced by factors such as air density, wind speed, and turbine efficiency. For solar energy, the Eq.

| 2 |

is employed, where  is the energy generated from solar (kWh),

is the energy generated from solar (kWh),  is the area of the solar panel (m2), G is the solar irradiance (W/m2),

is the area of the solar panel (m2), G is the solar irradiance (W/m2),  represents the efficiency of the solar panel (dimensionless),

represents the efficiency of the solar panel (dimensionless),  is the temperature coefficient of the solar panel (per °C), T is the temperature (°C), and

is the temperature coefficient of the solar panel (per °C), T is the temperature (°C), and  is the reference temperature (°C). This equation accounts for the effects of temperature on solar panel efficiency, as temperature increases can reduce the panel’s ability to generate energy. Geothermal energy generation is modeled using the Eq.

is the reference temperature (°C). This equation accounts for the effects of temperature on solar panel efficiency, as temperature increases can reduce the panel’s ability to generate energy. Geothermal energy generation is modeled using the Eq.

| 3 |

where  is the energy generated from geothermal sources (kWh),

is the energy generated from geothermal sources (kWh),  is the geothermal heat flow (W),

is the geothermal heat flow (W),  is the temperature difference (°C), and

is the temperature difference (°C), and  is the specific heat capacity of the geothermal fluid (J/kg°C). This equation estimates the energy produced based on the heat transfer and temperature variation in geothermal systems.

is the specific heat capacity of the geothermal fluid (J/kg°C). This equation estimates the energy produced based on the heat transfer and temperature variation in geothermal systems.

After Data Collection, the next step is Define System Objectives, where optimization goals like cost reduction and energy efficiency are set. These objectives help guide the optimization process by focusing on the most important outcomes such as minimizing costs while maximizing energy production. Defining clear system objectives ensures that the project remains focused on achieving the best possible performance while meeting financial and environmental goals. The main objectives in this phase typically include reducing capital and operational costs, increasing system efficiency, and maximizing renewable energy use. Setting these goals ensures that every step in the optimization process is aligned with achieving the desired results.

Setting optimization goals involves ensuring that energy production, cost efficiency, and sustainability are the key performance indicators. These goals drive the system design process and ultimately determine the techno-economic viability of the project. By focusing on reducing costs while maximizing energy efficiency, the system can provide a reliable power supply without exceeding budget constraints. Defining system objectives helps prioritize the design considerations, ensuring that the system is both technically viable and economically sustainable. Without these clear objectives, the system design may lack direction and fail to meet necessary performance or financial targets. The capital (CAPEX) and operational (OPEX) expenditures used in this study are derived from literature values reported in references6,7. These values were adapted to reflect the local context by incorporating regional cost adjustments, inflation indexing, and technology-specific parameters relevant to the system design. All values were normalized in alignment with the economic modeling framework presented in the total system cost is determined by the Eq.

| 4 |

where  is the total system cost (in dollars),

is the total system cost (in dollars),  represents the cost of wind turbines (in dollars),

represents the cost of wind turbines (in dollars),  is the cost of solar panels (in dollars),

is the cost of solar panels (in dollars),  refers to the cost of geothermal systems (in dollars),

refers to the cost of geothermal systems (in dollars),  is the cost of energy storage systems (in dollars), and

is the cost of energy storage systems (in dollars), and  indicates the cost of control systems (in dollars). This equation calculates the overall investment required to deploy and operate the hybrid renewable system by aggregating the individual costs of each component. The energy efficiency objective is represented by the equation

indicates the cost of control systems (in dollars). This equation calculates the overall investment required to deploy and operate the hybrid renewable system by aggregating the individual costs of each component. The energy efficiency objective is represented by the equation

| 5 |

where  is the total system efficiency (in percentage),

is the total system efficiency (in percentage),  refers to the total energy output (in kWh), and

refers to the total energy output (in kWh), and  represents the total available energy from all sources (in kWh). This equation helps evaluate how effectively the hybrid system utilizes the available energy resources to generate power, where a higher efficiency percentage indicates better utilization of the renewable resources.

represents the total available energy from all sources (in kWh). This equation helps evaluate how effectively the hybrid system utilizes the available energy resources to generate power, where a higher efficiency percentage indicates better utilization of the renewable resources.

In terms of sustainability, the objective is represented by the equation

| 6 |

where  represents the total greenhouse gas emissions (in kg CO2),

represents the total greenhouse gas emissions (in kg CO2),  refers to emissions associated with wind (in kg CO2),

refers to emissions associated with wind (in kg CO2),  represents emissions associated with solar (in kg CO2),

represents emissions associated with solar (in kg CO2),  represents emissions associated with geothermal (in kg CO2), and

represents emissions associated with geothermal (in kg CO2), and  is the offset from carbon credits (in kg CO2). This equation calculates the environmental impact of the hybrid energy system, ensuring that greenhouse gas emissions are minimized through the adoption of renewable energy sources and the use of carbon offset mechanisms. Once the System Objectives are defined, the next step is System Configuration Selection, where the most suitable combination of renewable energy sources is chosen based on available resources. The choice of energy sources depends on the specific environmental conditions at the installation site, such as wind speed, solar irradiance, and geothermal heat flow. The objective is to select a mix of renewable resources that can efficiently meet the energy demand while being cost-effective. Each resource—wind, solar, and geothermal—has unique characteristics that must be optimized based on their availability. This step ensures that the hybrid system is appropriately designed to take advantage of the most effective renewable resources for the location. In the next step, the optimal combination of renewable energy sources is chosen to meet the energy demand while considering environmental conditions. The selection of energy sources is driven by factors such as location-specific wind speed, solar irradiance, and geothermal heat flow, with each energy source contributing to the system’s overall efficiency. The goal is to choose a mix of wind, solar, and geothermal systems that will work together to provide consistent and reliable power. The energy generation potential from each source must be balanced to minimize costs and maximize efficiency. By evaluating the energy mix, system designers ensure that the chosen configuration is sustainable, cost-effective, and capable of meeting load requirements.

is the offset from carbon credits (in kg CO2). This equation calculates the environmental impact of the hybrid energy system, ensuring that greenhouse gas emissions are minimized through the adoption of renewable energy sources and the use of carbon offset mechanisms. Once the System Objectives are defined, the next step is System Configuration Selection, where the most suitable combination of renewable energy sources is chosen based on available resources. The choice of energy sources depends on the specific environmental conditions at the installation site, such as wind speed, solar irradiance, and geothermal heat flow. The objective is to select a mix of renewable resources that can efficiently meet the energy demand while being cost-effective. Each resource—wind, solar, and geothermal—has unique characteristics that must be optimized based on their availability. This step ensures that the hybrid system is appropriately designed to take advantage of the most effective renewable resources for the location. In the next step, the optimal combination of renewable energy sources is chosen to meet the energy demand while considering environmental conditions. The selection of energy sources is driven by factors such as location-specific wind speed, solar irradiance, and geothermal heat flow, with each energy source contributing to the system’s overall efficiency. The goal is to choose a mix of wind, solar, and geothermal systems that will work together to provide consistent and reliable power. The energy generation potential from each source must be balanced to minimize costs and maximize efficiency. By evaluating the energy mix, system designers ensure that the chosen configuration is sustainable, cost-effective, and capable of meeting load requirements.

The total energy production from the hybrid system is calculated using the equation

| 7 |

where  represents the total energy generated by the hybrid system (in kWh),

represents the total energy generated by the hybrid system (in kWh),  is the energy generated from wind (in kWh),

is the energy generated from wind (in kWh),  is the energy produced from solar (in kWh), and

is the energy produced from solar (in kWh), and  denotes the energy produced from geothermal sources (in kWh). This equation sums the individual energy contributions from each renewable source to determine the total energy output of the hybrid system. The renewable resource availability factor is represented by the Eq.

denotes the energy produced from geothermal sources (in kWh). This equation sums the individual energy contributions from each renewable source to determine the total energy output of the hybrid system. The renewable resource availability factor is represented by the Eq.

| 8 |

where  indicates the renewable resource availability factor (in percentage),

indicates the renewable resource availability factor (in percentage),  is the available energy from resources (in kWh), and

is the available energy from resources (in kWh), and  represents the maximum possible energy generation (in kWh). This factor helps assess how effectively the hybrid system utilizes the available resources in relation to their maximum potential, ensuring that the system is designed to optimize resource availability. The system cost efficiency is calculated by the Eq.

represents the maximum possible energy generation (in kWh). This factor helps assess how effectively the hybrid system utilizes the available resources in relation to their maximum potential, ensuring that the system is designed to optimize resource availability. The system cost efficiency is calculated by the Eq.

| 9 |

where  is the cost efficiency of the system (in percentage),

is the cost efficiency of the system (in percentage),  is the total capital cost of the system (in dollars), and

is the total capital cost of the system (in dollars), and  is the total energy generated by the system (in kWh). This equation evaluates how cost-effective the hybrid energy system is by comparing the capital investment against the total energy production, with a lower cost efficiency value indicating that the system is less economical in terms of energy production per unit cost. Following System Configuration Selection, the next step is Capital Cost Estimation, where the initial investment required for the system components is calculated. This estimation includes all costs related to the procurement and installation of wind turbines, solar panels, geothermal systems, storage units, and control systems. Estimating the capital cost is essential for determining the overall feasibility of the project, as it provides the baseline for the financial evaluation. Accurate capital cost estimation allows for the identification of potential cost-saving opportunities and informs decision-making regarding system size and components. This step ensures that the project remains within budget while achieving the desired technical performance. Capital cost estimation involves calculating the total investment needed for the system components, considering factors such as the number and size of components, installation costs, and associated infrastructure. This estimation is crucial for assessing the project’s financial feasibility and ensuring that the costs align with the financial objectives. A comprehensive capital cost estimation helps identify areas where cost reductions may be necessary and provides a solid financial basis for the project. It is also essential for determining the return on investment (ROI) and for setting appropriate funding and financing strategies. Accurate cost estimation also provides stakeholders with clear financial expectations and helps prevent budget overruns. The total capital cost of the system is calculated using the Eq.

is the total energy generated by the system (in kWh). This equation evaluates how cost-effective the hybrid energy system is by comparing the capital investment against the total energy production, with a lower cost efficiency value indicating that the system is less economical in terms of energy production per unit cost. Following System Configuration Selection, the next step is Capital Cost Estimation, where the initial investment required for the system components is calculated. This estimation includes all costs related to the procurement and installation of wind turbines, solar panels, geothermal systems, storage units, and control systems. Estimating the capital cost is essential for determining the overall feasibility of the project, as it provides the baseline for the financial evaluation. Accurate capital cost estimation allows for the identification of potential cost-saving opportunities and informs decision-making regarding system size and components. This step ensures that the project remains within budget while achieving the desired technical performance. Capital cost estimation involves calculating the total investment needed for the system components, considering factors such as the number and size of components, installation costs, and associated infrastructure. This estimation is crucial for assessing the project’s financial feasibility and ensuring that the costs align with the financial objectives. A comprehensive capital cost estimation helps identify areas where cost reductions may be necessary and provides a solid financial basis for the project. It is also essential for determining the return on investment (ROI) and for setting appropriate funding and financing strategies. Accurate cost estimation also provides stakeholders with clear financial expectations and helps prevent budget overruns. The total capital cost of the system is calculated using the Eq.

| 10 |

where  represents the total capital cost (in dollars),

represents the total capital cost (in dollars),  is the cost associated with wind turbines (in dollars),

is the cost associated with wind turbines (in dollars),  denotes the cost of solar panels (in dollars),

denotes the cost of solar panels (in dollars),  represents the cost of geothermal systems (in dollars),

represents the cost of geothermal systems (in dollars),  refers to the cost of energy storage systems (in dollars), and

refers to the cost of energy storage systems (in dollars), and  is the cost for control systems (in dollars). This equation adds up the individual costs of all the components necessary for the system to function, providing a comprehensive picture of the initial investment required for deployment. To assess the cost-efficiency of the system in terms of energy production, the cost per unit of energy is calculated using the equation

is the cost for control systems (in dollars). This equation adds up the individual costs of all the components necessary for the system to function, providing a comprehensive picture of the initial investment required for deployment. To assess the cost-efficiency of the system in terms of energy production, the cost per unit of energy is calculated using the equation

| 11 |

where  is the cost per unit of energy (in dollars per kWh),

is the cost per unit of energy (in dollars per kWh),  is the total capital cost (in dollars), and

is the total capital cost (in dollars), and  is the total energy produced by the system (in kWh). This equation indicates how much the system costs per unit of energy produced, helping to assess whether the energy generation is financially viable and cost-effective. Another essential calculation in the financial assessment is the break-even point for capital recovery, which determines the time required for the system to generate enough revenue to recover the initial investment. This is calculated using the equation

is the total energy produced by the system (in kWh). This equation indicates how much the system costs per unit of energy produced, helping to assess whether the energy generation is financially viable and cost-effective. Another essential calculation in the financial assessment is the break-even point for capital recovery, which determines the time required for the system to generate enough revenue to recover the initial investment. This is calculated using the equation

| 12 |

where  represents the time to break even (in years),

represents the time to break even (in years),  is the total capital cost (in dollars), and

is the total capital cost (in dollars), and  is the annual revenue generated from the system (in dollars). This equation helps estimate how many years it will take for the system to pay back its initial investment based on the annual income it generates. By determining this time frame, stakeholders can evaluate whether the system is a viable long-term investment, ensuring that the return on investment (ROI) is achieved within an acceptable period. Energy production modeling is a crucial step in assessing the expected energy output of the hybrid renewable energy system based on environmental data. This step involves simulating how much energy each renewable resource—wind, solar, and geothermal—can generate under varying environmental conditions, such as changes in weather, time of day, and seasonal variations. Accurate modeling ensures that the system can consistently meet the energy demand, providing both reliability and stability. In this step, the environmental data collected earlier is used to estimate the generation potential from each energy source, factoring in potential downtimes or fluctuations in availability. Additionally, it helps in optimizing the system design by assessing the expected capacity factor and generation patterns, guiding decisions about system component sizing and storage needs.

is the annual revenue generated from the system (in dollars). This equation helps estimate how many years it will take for the system to pay back its initial investment based on the annual income it generates. By determining this time frame, stakeholders can evaluate whether the system is a viable long-term investment, ensuring that the return on investment (ROI) is achieved within an acceptable period. Energy production modeling is a crucial step in assessing the expected energy output of the hybrid renewable energy system based on environmental data. This step involves simulating how much energy each renewable resource—wind, solar, and geothermal—can generate under varying environmental conditions, such as changes in weather, time of day, and seasonal variations. Accurate modeling ensures that the system can consistently meet the energy demand, providing both reliability and stability. In this step, the environmental data collected earlier is used to estimate the generation potential from each energy source, factoring in potential downtimes or fluctuations in availability. Additionally, it helps in optimizing the system design by assessing the expected capacity factor and generation patterns, guiding decisions about system component sizing and storage needs.

The total energy generation by the hybrid system is determined by adding the energy produced from all renewable sources, wind, solar, and geothermal. This is captured by the equation

| 13 |

where  represents the total energy generated by the system (in kWh),

represents the total energy generated by the system (in kWh),  is the energy produced by wind (in kWh),

is the energy produced by wind (in kWh),  is the energy produced by solar (in kWh), and

is the energy produced by solar (in kWh), and  is the energy produced from geothermal sources (in kWh). This equation provides the total amount of electricity generated by the system, ensuring the integrated use of multiple renewable resources to meet energy demand. The energy produced from each source is combined to evaluate the system’s overall performance, helping identify any shortfalls or excess production relative to demand.

is the energy produced from geothermal sources (in kWh). This equation provides the total amount of electricity generated by the system, ensuring the integrated use of multiple renewable resources to meet energy demand. The energy produced from each source is combined to evaluate the system’s overall performance, helping identify any shortfalls or excess production relative to demand.

Next, the energy capacity factor (CF) is an important metric for evaluating how effectively the system operates relative to its rated capacity. This is calculated by the equation

| 14 |

where CF represents the capacity factor (in percentage),  is the actual energy output of the system (in kWh), and

is the actual energy output of the system (in kWh), and  is the rated capacity of the system (in kWh). The capacity factor measures how much energy is generated relative to the maximum potential energy output. A higher capacity factor indicates a more efficient system, as it consistently operates near its rated capacity. This metric helps identify inefficiencies or overestimations in energy generation potential, enabling further optimization of the system design. Lastly, the energy availability ratio is calculated to assess whether the energy produced by the system meets the demand requirements. The equation

is the rated capacity of the system (in kWh). The capacity factor measures how much energy is generated relative to the maximum potential energy output. A higher capacity factor indicates a more efficient system, as it consistently operates near its rated capacity. This metric helps identify inefficiencies or overestimations in energy generation potential, enabling further optimization of the system design. Lastly, the energy availability ratio is calculated to assess whether the energy produced by the system meets the demand requirements. The equation

| 15 |

which determines the energy availability ratio, where  is the energy availability ratio (in percentage),

is the energy availability ratio (in percentage),  is the energy produced by the system (in kWh), and

is the energy produced by the system (in kWh), and  is the energy demand or load (in kWh). This equation helps assess the adequacy of the hybrid system’s energy generation to meet the required energy demand. A higher energy availability ratio indicates that the system consistently meets or exceeds demand, while a lower ratio may suggest the need for additional energy production capacity or storage to ensure reliable power supply. Performance simulation involves modeling the system’s behavior under different environmental scenarios to assess its overall efficiency and reliability. This step simulates how the system would perform during real-world conditions such as varying weather patterns, fluctuating renewable resource availability, and changing energy demands. By running these simulations, the team can identify weaknesses or inefficiencies in the system, ensuring that it can operate optimally despite external factors. The simulation also provides insight into the potential impacts of system downtime or resource unavailability, helping to fine-tune system components and optimize the configuration. This step ensures that the hybrid system is designed to meet demand reliably and efficiently under all potential environmental conditions. One of the primary performance indicators is system efficiency under simulation, calculated using the equation

is the energy demand or load (in kWh). This equation helps assess the adequacy of the hybrid system’s energy generation to meet the required energy demand. A higher energy availability ratio indicates that the system consistently meets or exceeds demand, while a lower ratio may suggest the need for additional energy production capacity or storage to ensure reliable power supply. Performance simulation involves modeling the system’s behavior under different environmental scenarios to assess its overall efficiency and reliability. This step simulates how the system would perform during real-world conditions such as varying weather patterns, fluctuating renewable resource availability, and changing energy demands. By running these simulations, the team can identify weaknesses or inefficiencies in the system, ensuring that it can operate optimally despite external factors. The simulation also provides insight into the potential impacts of system downtime or resource unavailability, helping to fine-tune system components and optimize the configuration. This step ensures that the hybrid system is designed to meet demand reliably and efficiently under all potential environmental conditions. One of the primary performance indicators is system efficiency under simulation, calculated using the equation

| 16 |

Here,  represents the simulation efficiency (in percentage),

represents the simulation efficiency (in percentage),  is the energy generated by the system during the simulation (in kWh), and

is the energy generated by the system during the simulation (in kWh), and  is the total available energy (in kWh). This equation helps evaluate how much of the available energy was successfully converted into usable power during the simulation, accounting for real-world inefficiencies or losses. High simulation efficiency indicates that the system is performing well under the simulated conditions, whereas lower values suggest potential improvements in system design or operation. Another important metric in performance simulation is system availability, which indicates the proportion of time the system is producing energy. This is determined using the equation

is the total available energy (in kWh). This equation helps evaluate how much of the available energy was successfully converted into usable power during the simulation, accounting for real-world inefficiencies or losses. High simulation efficiency indicates that the system is performing well under the simulated conditions, whereas lower values suggest potential improvements in system design or operation. Another important metric in performance simulation is system availability, which indicates the proportion of time the system is producing energy. This is determined using the equation

| 17 |

where  is the system availability (in percentage),

is the system availability (in percentage),  is the energy produced while the system is operational (in kWh), and

is the energy produced while the system is operational (in kWh), and  is the total energy generation potential (in kWh). This measure reflects the fraction of time the system is able to produce energy compared to its maximum potential. A high system availability percentage indicates that the system operates efficiently without significant downtime, ensuring consistent power output. If the availability is lower than expected, adjustments may be needed to reduce downtime or enhance system reliability. Finally, downtime loss quantifies the energy lost due to system inoperability. The equation

is the total energy generation potential (in kWh). This measure reflects the fraction of time the system is able to produce energy compared to its maximum potential. A high system availability percentage indicates that the system operates efficiently without significant downtime, ensuring consistent power output. If the availability is lower than expected, adjustments may be needed to reduce downtime or enhance system reliability. Finally, downtime loss quantifies the energy lost due to system inoperability. The equation

| 18 |

calculates the downtime loss, where  represents the loss due to system downtime (in kWh),

represents the loss due to system downtime (in kWh),  is the system availability (in percentage), and

is the system availability (in percentage), and  is the total energy generation potential (in kWh). This equation highlights the impact of system downtime on overall energy generation. A higher downtime loss indicates more frequent or longer periods of inoperability, which directly impacts system performance and overall energy supply. Minimizing downtime loss is crucial for ensuring that the hybrid renewable energy system can meet demand consistently and efficiently, even under challenging environmental conditions. Optimization of design parameters is the process of fine-tuning system configurations to achieve optimal energy production, cost efficiency, and sustainability. This step ensures that energy production meets demand while minimizing costs and improving overall system performance. If the initial parameters, such as energy production, cost, and efficiency, do not meet the desired targets, the system configuration must be redesigned. This can involve resizing the renewable energy sources, optimizing component efficiencies, or modifying system storage configurations. The goal is to make adjustments that result in a better balance between technical performance and financial feasibility, ensuring the hybrid system meets all objectives. One of the primary metrics for optimization is the cost-energy ratio, calculated using the equation

is the total energy generation potential (in kWh). This equation highlights the impact of system downtime on overall energy generation. A higher downtime loss indicates more frequent or longer periods of inoperability, which directly impacts system performance and overall energy supply. Minimizing downtime loss is crucial for ensuring that the hybrid renewable energy system can meet demand consistently and efficiently, even under challenging environmental conditions. Optimization of design parameters is the process of fine-tuning system configurations to achieve optimal energy production, cost efficiency, and sustainability. This step ensures that energy production meets demand while minimizing costs and improving overall system performance. If the initial parameters, such as energy production, cost, and efficiency, do not meet the desired targets, the system configuration must be redesigned. This can involve resizing the renewable energy sources, optimizing component efficiencies, or modifying system storage configurations. The goal is to make adjustments that result in a better balance between technical performance and financial feasibility, ensuring the hybrid system meets all objectives. One of the primary metrics for optimization is the cost-energy ratio, calculated using the equation

| 19 |

Here,  represents the cost-energy ratio (in percentage),

represents the cost-energy ratio (in percentage),  is the total capital cost (in dollars), and

is the total capital cost (in dollars), and  is the total energy produced by the system (in kWh). This ratio helps evaluate how much capital investment is required to produce a given amount of energy. A lower cost-energy ratio indicates a more cost-efficient system, suggesting that the system is generating more energy per unit of investment. The goal in this optimization step is to minimize the cost-energy ratio while maximizing energy production to achieve the best financial returns. Efficiency optimization is another key aspect of design parameter optimization, where the focus is on improving the energy output of the system. The efficiency optimization is calculated using the equation

is the total energy produced by the system (in kWh). This ratio helps evaluate how much capital investment is required to produce a given amount of energy. A lower cost-energy ratio indicates a more cost-efficient system, suggesting that the system is generating more energy per unit of investment. The goal in this optimization step is to minimize the cost-energy ratio while maximizing energy production to achieve the best financial returns. Efficiency optimization is another key aspect of design parameter optimization, where the focus is on improving the energy output of the system. The efficiency optimization is calculated using the equation

| 20 |

where  represents the optimization efficiency (in percentage),

represents the optimization efficiency (in percentage),  is the optimized energy output (in kWh), and

is the optimized energy output (in kWh), and  is the expected energy output (in kWh). This equation helps assess how close the actual energy production is to the expected output under optimized conditions. A higher optimization efficiency indicates that the system is operating at or near its maximum potential. If the efficiency is lower than expected, further adjustments to system design or operational parameters may be necessary to achieve better results. Energy storage efficiency is also a critical parameter in optimizing the overall system performance. It is calculated using the equation

is the expected energy output (in kWh). This equation helps assess how close the actual energy production is to the expected output under optimized conditions. A higher optimization efficiency indicates that the system is operating at or near its maximum potential. If the efficiency is lower than expected, further adjustments to system design or operational parameters may be necessary to achieve better results. Energy storage efficiency is also a critical parameter in optimizing the overall system performance. It is calculated using the equation

| 21 |

where  represents the storage efficiency (in percentage),

represents the storage efficiency (in percentage),  is the energy stored in storage systems (in kWh), and

is the energy stored in storage systems (in kWh), and  is the total energy generated by the system (in kWh). This measure evaluates how effectively the energy storage system retains energy for later use, ensuring that excess energy generated during periods of high production can be utilized when demand exceeds supply. A higher storage efficiency indicates that a larger proportion of the generated energy is being stored and available for later use, which is essential for maintaining consistent energy supply. Reducing storage losses and improving storage systems are key goals in this optimization process to enhance the system’s overall performance and reliability. The Techno-Economic Evaluation step involves analyzing the overall financial feasibility and performance of the system. This evaluation assesses whether the hybrid renewable energy system provides an acceptable return on investment (ROI) and whether it meets all financial performance targets. The techno-economic evaluation integrates the technical performance (energy production, system efficiency) with economic parameters (capital costs, operational expenses). It helps in determining if the system is financially viable, both in terms of initial investment and long-term returns. The results of this evaluation guide decision-making about further optimizations, adjustments to the system design, and necessary cost reductions to improve economic feasibility. One of the primary financial metrics used is the Return on Investment (ROI), which evaluates the profitability of the system. The equation for ROI is given by

is the total energy generated by the system (in kWh). This measure evaluates how effectively the energy storage system retains energy for later use, ensuring that excess energy generated during periods of high production can be utilized when demand exceeds supply. A higher storage efficiency indicates that a larger proportion of the generated energy is being stored and available for later use, which is essential for maintaining consistent energy supply. Reducing storage losses and improving storage systems are key goals in this optimization process to enhance the system’s overall performance and reliability. The Techno-Economic Evaluation step involves analyzing the overall financial feasibility and performance of the system. This evaluation assesses whether the hybrid renewable energy system provides an acceptable return on investment (ROI) and whether it meets all financial performance targets. The techno-economic evaluation integrates the technical performance (energy production, system efficiency) with economic parameters (capital costs, operational expenses). It helps in determining if the system is financially viable, both in terms of initial investment and long-term returns. The results of this evaluation guide decision-making about further optimizations, adjustments to the system design, and necessary cost reductions to improve economic feasibility. One of the primary financial metrics used is the Return on Investment (ROI), which evaluates the profitability of the system. The equation for ROI is given by

| 22 |

where  represents the annual revenue from energy sales (in dollars),

represents the annual revenue from energy sales (in dollars),  is the annual operational costs (in dollars), and

is the annual operational costs (in dollars), and  is the total capital cost (in dollars). ROI is expressed as a percentage and measures how much profit is generated for every dollar invested in the system. A positive ROI indicates that the system is financially viable and can provide returns to the investors. If the ROI is negative or too low, the project may not be economically viable, and adjustments may be necessary to improve financial returns. Another important metric in the techno-economic evaluation is the Net Present Value (NPV), which assesses the value of future cash flows over time, discounted to the present value. The equation for NPV is

is the total capital cost (in dollars). ROI is expressed as a percentage and measures how much profit is generated for every dollar invested in the system. A positive ROI indicates that the system is financially viable and can provide returns to the investors. If the ROI is negative or too low, the project may not be economically viable, and adjustments may be necessary to improve financial returns. Another important metric in the techno-economic evaluation is the Net Present Value (NPV), which assesses the value of future cash flows over time, discounted to the present value. The equation for NPV is

| 23 |

where  represents the revenue in year t (in dollars), r is the discount rate (in percentage),