Abstract

Just as kindness is prioritized in mate selection, warmth and fairness are often favored in cooperative social interactions, sometimes over competence and wealth, suggesting that these traits may influence social status. We conducted three studies to examine how heterosexual men (N = 193) and women (N = 178) from the U.S. evaluate men’s faces for mating- and status-relevant traits, both alone and in combination with vignettes describing their economic resources and ethical reputation. The vignettes presented all men as generally smart, nurturant, and healthy, but pitted economic resources against ethical reputation surrounding care and fairness. Study 1, pitting men’s ethics against their resources, found that an ethical reputation enhanced ratings of long-term mating attractiveness, prestige, intelligence, and kindness, but short-term mating attractiveness and physical dominance ratings were unaffected. Study 2, pitting men’s parent’s ethics against parental resources, yielded results consistent with Study 1. Study 3, pitting men’s ethical history related to their adolescence with their current resources, found similar results to studies 1 and 2 with one key difference: women lowered prestige ratings for men with an unethical past, and men lowered physical dominance ratings for these men. The discussion reassesses notions of status and resources, exploring their relative significance in mating evaluations.

Keywords: Mate preferences, Reputation, Status, Prestige, Altruism, Resources

Subject terms: Evolution, Sexual selection

Introduction

Heterosexual women and men prefer kind, understanding, and intelligent mates1,2a finding that is consistent across cultures3,4. While both sexes prioritize these traits in mate preferences, one of the traits that shows maximal sex difference is resource acquisition potential. Women, more than men, prioritize a mate’s ability to acquire resources1,5. From an evolutionary perspective, these findings have been interpreted through the lens of parental investment theory6. As women’s obligatory parental investment is greater than men’s in terms of gestation, lactation, and care expended to offspring during the protracted human childhood, women prioritize potential mates’ ability to acquire resources and their commitment to provide for the family2,7. In line with this notion, a man’s economic resources and displays of kindness serve as cues to his resource acquisition potential and willingness to provide for his partner and future offspring1,2.

High income men are high in mate value. Women in the U.S. and China were more sensitive than men to increases in a potential mate’s salary in influencing their perceived attractiveness8. High-income men enjoy greater mating success9reporting higher frequency of sex and a greater number of biological children10. They are also more likely to marry and less likely to divorce11. Given these associations, it is not surprising that studies presenting men’s photographs with luxury cars and apartments receive higher attractiveness ratings by heterosexual women compared to those presented with cheaper brands12,13. However, when two men with the same amount of money use it toward flashy versus frugal spending, the former is associated with increased attractiveness for the short term, and the thoughtful, rational spending is associated with long-term mating attractiveness14,15. Mating primes increase men’s conspicuous consumption of luxury items16; they compete to purchase luxury brands, leading to feelings of higher status17. Interestingly, men perceive other men with luxury brands as ambitious, intelligent, and oriented toward short-term mating17. These findings support the notion that long-term mating attractiveness depends on men’s ability to provide resources and economic stability to potential mates and offspring.

Like high-income men, kind4 and altruistic18 men are also perceived as high in mate value. Although “kindness” and “altruism” have slightly different meanings, several studies including those referenced below have used these words and others such as “generosity” and “helping” interchangeably, all of which have been described as behaviors that benefit others but pose some cost to the actor19–23. Women tend to prefer altruistic men, especially for long-term mating contexts19,24–28. Non-altruistic men receive higher short-term than long-term attractiveness ratings25,29although this finding is not consistent across cultures30. Altruistic displays, like wealth displays, increase in the presence of women16,31–33and men often compete with one another employing these displays34,35. Also, like wealthy men, altruistic men compared to non-altruistic men report higher self-perceived desirability and greater mating success23,36,37even when controlling for narcissism23,38. Altruism has also been associated with reproductive success39.

The consistent finding that women favor altruism in long-term relationships is interpreted as evidence of selection for good parental and partner qualities that helped to sustain committed relationships24,28,31. Along the same lines, although women prefer altruistic men, they do not want their mates to direct unfettered kindness and trustworthiness to all individuals; they would rather that more kindness and trustworthiness be directed to themselves and their families and friends than strangers22. Women would like their potential mates to direct more dominance than kindness to other men22. Another study employing the ultimatum game found that women preferred moderately altruistic to highly altruistic men29. The evolutionary interpretation is that mating with men who displayed indiscriminate altruism may have been disadvantageous to women as they would not have enjoyed resource privileges relative to others22. Consider that although altruistic men are generally virtuous, they do not seem to be paragons of sexual virtue. While they experience reproductive success39 and are desired by women for committed relationships, given the reported number of casual sex partners23,36,37it is not clear that men’s altruism is particularly well designed to fulfill women’s preference for long-term, target-specific altruism. This conundrum is perhaps another example of conflict between the sexes40,41; men’s altruistic acts and targets may not exactly match women’s preferences.

Nevertheless, altruism may suggest good character in general19,42. Prestige, a route to social status that is often differentiated from dominance, is earned through generous, wasteful, and sacrificial behaviors leading the community at large to voluntarily grant deference to benefactors43. High testosterone levels in men correlate with greater generosity in the dictator game, potentially promoting status-seeking44. In economic games people tend to value fairness over wealth45. Both prestige46 and altruism21,47have been associated with moral intuitions. Women prefer prestigious long-term mates to dominant ones48,49 who, like dominant men, have a high potential for reproductive success50. It is possible that women prefer altruistic men as long-term partners because they have earned high status through a strong ethical reputation.

Whereas the pair bonding-based explanation focuses on kind men channeling resources to long-term mates and offspring, the prestige-based rationale for men’s kind acts involves good ethical conduct more broadly, which explicitly signals consideration of the broader group’s needs and norms. In the former explanation, women’s preference for kind long-term mates likely evolved due to direct benefits that women (and offspring) gained through men’s generosity directed to them. In the latter explanation, women’s preferences evolved to favor high-status mates where status has been granted voluntarily by potential competitors and collaborators for men’s magnanimity and integrity. This conjecture is further supported by discussions involving leveling coalitions51self-domestication52the emergence of social tolerance53 and cooperation54. Additionally, links between prestige and prosociality55and parallels between men’s evaluations of other men’s prestige/dominance and women’s evaluations of these men’s long-term mating attractiveness/short-term evaluations56 necessitate the inclusion of men (in addition to women) as evaluators of status and mating-relevant traits of other men.

Note that ethical conduct and economic resources do not readily go hand in hand in the minds of most lay people. The rich are generally perceived as selfish (although this is not necessarily the case57) and are held to higher ethical standards58. Positions of power are occupied by dominant men, who are more likely to engage in dishonest behavior59. Whereas norm violation is associated with dominance-strategists, norm abidance has been associated with prestige-oriented individuals60–63. Both norm abidance and norm violation involve costs. There are opportunity costs that prevent ethical men from pursuing expedient strategies for self and family enhancement64. Conversely, unethical men may face costs related to risky behaviors that jeopardize their future prospects63,65. According to the costly signaling hypothesis, it can be argued that only men who are capable of weathering costs engage in these behaviors66,67.

Status is socially negotiated whether it is coerced through apparent dominance differentials68 or is freely conferred through prestige processes55,69. Finally, like women’s preference for wealthy9 and kind/ethical mates1,4social valuation or devaluation associated with benevolent acts and wrongdoing70–72is a cross-cultural phenomenon. When wealth and ethics-based social valuation are in conflict, how do evaluations of men’s status and mating prospects vary? The current study investigates how women and men evaluate men with abundant economic resources but who have a reputation of questionable ethics versus men with fewer resources but a strong ethical reputation.

The evaluations focus on short-term mating attractiveness, long-term mating attractiveness, prestige, physical dominance, kindness, and intelligence. The study particularly considers these evaluations in scenarios where both groups of men are also reputed to be similarly smart, sociable, nurturant, and physically active– traits that imply resource acquisition capacity, potential investment in kin and close acquaintances, and good health.

In this paper, we present three vignette-based studies, each differing in the target characteristics. Study 1 varied the ethical reputation of the men (personal ethics), Study 2 varied the ethical reputation of the men’s parents (parental ethics), and Study 3 varied the ethical reputation of the men during adolescence (developmental ethics). The ethical/non-ethical vignettes (see vignettes via the OSF link) have some overlap with items in the Self-report Altruism (SRA) Scale73. Some examples from the SRA scale are: I have given money to a charity; I have pointed out a clerk’s error (in a bank, at the supermarket) in undercharging me for an item; I have helped a classmate who I did not know that well with an assignment; I have bought charity Christmas cards deliberately because I knew it was for a good cause. These behaviors not only incur some cost to the actor while benefiting another but also appear to tap moral intuitions such as care and fairness (or proportionality, per more recent convention)74two intuitions that tend to move in tandem with each other75. Fairness has also been linked to honesty-humility76,77. The vignettes were presented as descriptions in a gossip magazine; both survey and experimental research suggest that receivers believe gossip to be true and they modify their behavior based on it78–80. Even so, we use the term ethical reputation in the remainder of the manuscript. Using “ethical reputation” aligns with the idea of morality as perceived through third-party descriptions, whereas “ethics” could blur this distinction.

Method

The study was approved by the institutional ethics board at Pace University, NY, and participants were treated in keeping with the Helsinki agreement. Participants were recruited through the Centiment panel service. The materials, procedural details, and statistical analyses that are common to the three studies are reported once in detail. Participant details and specific vignette examples are reported separately for each of the three studies.

Materials and procedure

The Qualtrics survey contained six photographs of men of various ethnicities procured through the website unsplash.com, which is free to the public (see all faces via OSF link). Upon providing informed consent, participants completed the demographic section (age, ethnicity, health, sexual orientation, English fluency, and location of residence), provided information on the use of hormonal contraceptives (for women) and rated their own attractiveness. Participants who moved on to the next section reported that they were heterosexual, healthy, and fluent in English. The next section, face-only rating, consisted of the six male faces where each of the faces was presented on a separate page with six accompanying 100-point slider scales comprising anchors of 0 (disagree) and 100 (agree). For each face, participants indicated their agreement (How likely are you to agree with the following statements? ) with each of the six statements below, the order of which was randomized for every participant.

This man is attractive for a short-term purely sexual relationship.

This man is attractive for a long-term committed relationship.

If this man got in a fistfight with an average male undergraduate this man would probably win.

This man is a prestigious person who is respected, admired, talented, and successful.

This man is kind and understanding.

This man is intelligent.

For male participants, the first two statements were slightly revised to read: This man is attractive to women for a short-term purely sexual relationship/long-term committed relationship. The final section of the survey consisted of the face-plus-vignette rating section where three of the six faces were associated with high ethics-low resources vignettes and the other three faces were associated with low ethics-high resources vignettes (see example presentation via OSF link). The high and low ethics vignettes were counterbalanced across faces and participants. Participants were asked to read the descriptions as though these were in a gossip magazine. While some of the previous studies employed a dual exposure method, in which participants were presented with the altruistic and non-altruistic vignettes, along with target photographs, in a randomized but sequential or simultaneous manner19,25,81we employed a pre-vignette exposure (face-only rating) and a post-vignette exposure method (face-plus-vignette rating) where these sections were separated by four filler/distractor tasks called “Find the Hidden Object” (see example via OSF link). This was done in order to reduce any retention/rehearsal of ratings in the face-only rating section in spite of the typical limits on information processing capacity82,83. In this way we addressed potential acquiescence bias to some extent, as our dependent variables were the difference scores (pre-exposure subtracted from post-exposure, see below). There were two simple attention check questions as well, and a wrong answer to any of those terminated the survey.

Statistical analyses

We conducted the statistical analyses using R (v.4.3.0), employing linear mixed-effects models with the ‘lme4’ (v.1.1–33)84 and ‘lmerTest’ (v.3.1-3)85 packages. In each model, random intercepts were specified separately for the faces and the raters. Changes in rating scores between the face-with-vignette section and the face-only section were included as dependent variables. Traits evaluation and ethics manipulation, along with their interaction effects, were treated as independent variables. Survey versions were included as covariates. Simple effects were examined to explore the specific impact of the ethics manipulation within each trait evaluation.

Study 1 (Personal ethics)

Participants

A total of 60 women (M = 23.58 years; SD = 3.39) and 64 men (M = 29.58 years; SD = 2.14) from the U.S. participated in the surveys. Note that the male raters’ average age is similar to that of the target men (29.83 years; see vignettes via OSF link). Also, the difference between our female raters’ and target men’s average ages is consistent with the robust finding that women prefer older men as mates86. About 55% of the men identified as White non-Latino, 30% as African American, 5% Asian American, 3% non-White Latino, 1% Middle Eastern, and 6% as other. About 62% of the women identified as White non-Latino, 18% as African American, 5% as Asian American, 5% as non-White Latino, and 10% as other.

Example Vignettes (see other vignettes via OSF link):

High Personal Ethics Low Resources (Ethical men from hereon).

Derek is 31 and single, and lives near your city. He enjoys playing baseball in the summer months and being outside. He loves to spend quality time with his niece and nephew. Derek is not wealthy. His neighbors and friends remark that he works hard and always encourages it; he would not even accept gifts from his team members, let alone bribes. Everyone who knows Derek thinks he has incredible potential and is very friendly.

Low Personal Ethics High Resources (Unethical men from hereon).

Derek is 31 and single, and lives near your city. He enjoys playing baseball in the summer months and being outside. He loves to spend quality time with his niece and nephew. Derek is very wealthy. His neighbors and friends remark that he sometimes engages in bribery to fill his pockets without doing a lot of real work. Everyone who knows Derek thinks he has incredible potential and is very friendly.

Results

Women’s ratings

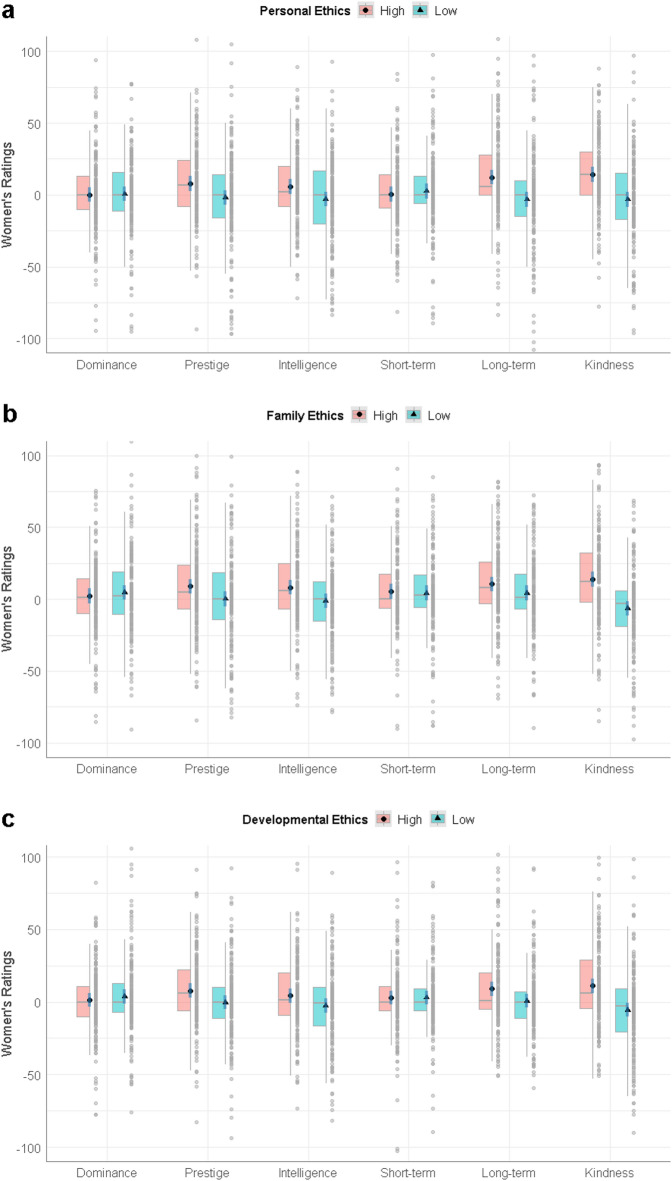

Mixed effects models for changes in women’s ratings are reported in Table 1. We found a significant interaction between traits and ethics (ps < 0.001; Table 1). Simple effects were further examined and presented in Fig. 1a; ratings were significantly higher in high ethics than in low ethics for all traits, except dominance and short-term attractiveness (Table 2).

Table 1.

Results of mixed effects models on changes in women’s and men’s ratings across vignettes.

| Gender | Ethics | Model | SS | df | MS | F | p | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Personal | Trait | 6928 | 5 | 1386 | 1.81 | 0.109 | 0.04 | 0.12 |

| Ethics | 34,643 | 1 | 34,643 | 45.14 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Survey Group | 786 | 1 | 786 | 1.02 | 0.316 | ||||

| Trait x Ethics | 28,273 | 5 | 5655 | 7.37 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Women | Parental/Family | Trait | 3858.2 | 5 | 771.6 | 1.15 | 0.330 | 0.04 | 0.21 |

| Ethics | 26730.9 | 1 | 26730.9 | 39.96 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Survey Group | 1934.8 | 1 | 1934.8 | 2.89 | 0.095 | ||||

| Trait x Ethics | 26878.4 | 5 | 5375.7 | 8.04 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Women | Developmental | Trait | 3225.4 | 5 | 645.1 | 1.11 | 0.351 | 0.03 | 0.16 |

| Ethics | 20763.8 | 1 | 20763.8 | 35.87 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Survey Group | 19.8 | 1 | 19.8 | 0.03 | 0.854 | ||||

| Trait x Ethics | 20988.5 | 5 | 4197.7 | 7.25 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Men | Personal | Trait | 6551 | 5 | 1310 | 2.79 | 0.016 | 0.02 | 0.16 |

| Ethics | 37,611 | 1 | 37,611 | 80.05 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Survey Group | 1192 | 1 | 1192 | 2.54 | 0.113 | ||||

| Trait x Ethics | 28,015 | 5 | 5603 | 11.92 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Men | Parental/Family | Trait | 1086.9 | 5 | 217.4 | 0.51 | 0.767 | 0.04 | 0.19 |

| Ethics | 20414.5 | 1 | 20414.5 | 48.09 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Survey Group | 2164.5 | 1 | 2164.5 | 5.10 | 0.027 | ||||

| Trait x Ethics | 14910.7 | 5 | 2982.1 | 7.03 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Men | Developmental | Trait | 3938.5 | 5 | 787.7 | 1.85 | 0.100 | 0.02 | 0.19 |

| Ethics | 8637.4 | 1 | 8637.4 | 20.31 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Survey Group | 115.0 | 1 | 115.0 | 0.27 | 0.605 | ||||

| Trait x Ethics | 5511.0 | 5 | 1102.2 | 2.59 | 0.024 |

Fig. 1.

Post-hoc comparisons between high and low ethics for women’s ratings across vignettes. Ratings differ significantly between high and low ethics for each trait, except dominance and short-term attractiveness in personal (a), family/parental (b), and developmental (c) ethic vignettes.

Table 2.

Results of simple effects tests for mixed effects models on changes in women’s and men’s ratings across vignettes for each trait.

| Gender | Ethics | Model | Estimate | SE | df | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Personal | Dominance Low vs. High | 0.43 | 2.79 | 294.00 | 0.15 | 0.878 |

| Prestige Low vs. High | -9.73 | 3.01 | 289.42 | -3.23 | < 0.001 | ||

| Intelligence Low vs. High | -8.82 | 2.85 | 289.66 | -3.09 | 0.002 | ||

| Short-term Low vs. High | 2.27 | 2.84 | 294.00 | 0.80 | 0.426 | ||

| Long-term Low vs. High | -15.45 | 3.31 | 288.85 | -4.67 | < 0.001 | ||

| Kindness Low vs. High | -17.16 | 2.80 | 289.49 | -6.12 | < 0.001 | ||

| Women | Parental/Family | Dominance Low vs. High | 2.50 | 2.77 | 279.08 | 0.91 | 0.366 |

| Prestige Low vs. High | -8.75 | 3.00 | 279.07 | -2.92 | 0.004 | ||

| Intelligence Low vs. High | -9.49 | 2.62 | 279.14 | -3.62 | < 0.001 | ||

| Short-term Low vs. High | -1.05 | 2.78 | 279.07 | -0.38 | 0.707 | ||

| Long-term Low vs. High | -6.28 | 2.71 | 279.13 | -2.32 | 0.021 | ||

| Kindness Low vs. High | -20.24 | 2.70 | 279.06 | -7.51 | < 0.001 | ||

| Women | Developmental | Dominance Low vs. High | 2.43 | 2.44 | 294.00 | 0.99 | 0.321 |

| Prestige Low vs. High | -8.06 | 2.56 | 294.00 | -3.15 | 0.002 | ||

| Intelligence Low vs. High | -6.83 | 2.59 | 294.00 | -2.64 | 0.009 | ||

| Short-term Low vs. High | 0.22 | 2.25 | 299.00 | 0.10 | 0.923 | ||

| Long-term Low vs. High | -8.30 | 2.47 | 299.00 | -3.36 | < 0.001 | ||

| Kindness Low vs. High | -16.66 | 2.68 | 294.00 | -6.22 | < 0.001 | ||

| Men | Personal | Dominance Low vs. High | -1.35 | 1.19 | 959.02 | -1.13 | 0.257 |

| Prestige Low vs. High | -6.16 | 1.27 | 959.03 | -4.86 | < 0.001 | ||

| Intelligence Low vs. High | -5.57 | 1.23 | 959.01 | -4.52 | < 0.001 | ||

| Short-term Low vs. High | 1.92 | 1.24 | 959.03 | 1.55 | 0.122 | ||

| Long-term Low vs. High | -5.92 | 1.33 | 959.02 | -4.44 | < 0.001 | ||

| Kindness Low vs. High | -10.84 | 1.36 | 959.02 | -7.95 | < 0.001 | ||

| Men | Parental/Family | Dominance Low vs. High | -1.52 | 2.06 | 319.00 | -0.74 | 0.463 |

| Prestige Low vs. High | -10.83 | 2.05 | 314.59 | -5.27 | < 0.001 | ||

| Intelligence Low vs. High | -6.42 | 1.98 | 314.13 | -3.24 | 0.001 | ||

| Short-term Low vs. High | 1.41 | 2.07 | 314.38 | 0.68 | 0.495 | ||

| Long-term Low vs. High | -4.78 | 2.20 | 319.00 | -2.18 | 0.030 | ||

| Kindness Low vs. High | -13.52 | 2.29 | 314.31 | -5.92 | < 0.001 | ||

| Men | Developmental | Dominance Low vs. High | -4.50 | 1.76 | 319.00 | -2.55 | 0.011 |

| Prestige Low vs. High | -2.79 | 2.03 | 314.00 | -1.37 | 0.171 | ||

| Intelligence Low vs. High | -4.27 | 2.09 | 314.00 | -2.05 | 0.042 | ||

| Short-term Low vs. High | 1.67 | 2.07 | 319.00 | 0.81 | 0.420 | ||

| Long-term Low vs. High | -4.53 | 2.27 | 319.00 | -2.00 | 0.047 | ||

| Kindness Low vs. High | -8.82 | 2.16 | 319.00 | -4.08 | < 0.001 |

Men’s ratings

Mixed effects models for changes in men’s ratings are reported in Table 1. We found a significant interaction between traits and ethics (ps < 0.05; Table 1). Simple effects were further examined and presented in Fig. 2a; ratings were significantly higher in high ethics than in low ethics for all traits, except for dominance and short-term attractiveness (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Post-hoc comparisons between high and low ethics for men’s ratings across vignettes. Ratings differ significantly between high and low ethics for each trait, except dominance and short-term attractiveness in personal (a) and family/parental (b) ethic vignettes. Ratings differ significantly between high and low ethics for each trait, except prestige and short-term attractiveness in developmental (c) ethic vignettes.

Discussion

Women preferred ethical men to unethical men for long-term mating contexts. They also perceived them to be kinder, more intelligent, and more prestigious than unethical men. Men’s ratings demonstrated the same patterns. It is interesting that physical dominance ratings did not change between the two types of vignettes. This suggests that higher altruism or ethical displays need not necessarily be considered an alternative strategy deployed by physically weaker men. Further, short-term mating ratings did not change across the ethical and unethical vignettes. Short-term attractiveness appears to follow physical dominance preferences similar to previous studies87,88.

The finding that women and men considered ethical men who are relatively less wealthy as kinder, more prestigious, and more suitable for long-term mating contexts, is in line with earlier findings that kindness ranks higher than resource acquisition potential1,45,89. Given that both ethical and unethical men were presented as smart, savvy, or of high potential, the higher intelligence scores attached to ethical men are noteworthy. It is possible that participants simply provided socially desirable responses. This possibility, however, applies to several studies on mate preferences including those adopting the trait-ranking method and vignette-method. Even so, when social desirability is controlled for, altruism still emerges as a desirable trait23and stated and revealed mate preferences need not be misaligned90. Another possibility is that lower ratings for unethical men are a form of sanctioning. If the motive was to impose a penalty on unethical men, ratings should have been lowered across all traits; the plausibility is weakened as ratings were lowered for only a subset of traits and not all traits. Further, if social desirability is a motivating factor, it still remains to be answered why a preference for ethical reputation would be socially desirable, and this exploration may be relevant to studies examining status perceptions and, thereby, mating-relevant perceptions (a point we return to under General Discussion). A third possibility is that women tend to avoid future economic instability by perceiving unethical men as too risky for long-term mating contexts. Perhaps ethical men promise more financial stability45.

Therefore, in study 2, we employed vignettes where men’s parents were wealthy-but-unethical or not wealthy-but-ethical, while keeping the men’s characteristics the same in both high and low “parental ethics” vignettes. In this way, we made sure that women’s evaluations would not be swayed by variations in men’s financial stability as the men in both categories were presented as possessing the same potential for resource acquisition. If women are particularly attentive to the reputation of potential mates (and men of potential competitors) and not as much to the reputation of their kin or familial environment, we should not expect changes to any of the ratings, as the men themselves in both categories were presented as possessing the same traits. If, however, economic resources are most important in long-term mating and status evaluations, women (and men) may favor smart, loving, and healthy men of wealthy parents regardless of parents’ ethics. Alternatively, given that family status and support are status-enhancing91 and prosocial and risky behaviors have been discussed as both heritable92,93 and influenced by parental environment94reputation regarding parents’ ethical practices may influence their sons’ mating and status prospects.

Study 2 (Parental ethics)

Participants

A total of 57 women (M = 24.02 years; SD = 3.28) and 64 men (M = 28.95 years; SD = 2.44) from the U.S. participated in the surveys. About 47% of the women identified as White non-Latino, 26% as African American, 9% as Asian American, 9% as non-White Latino, 3% as Middle Eastern, and 5% as other. About 56% of the men identified as White non-Latino, 22% as African American, 6% as Asian American, 6% as non-White Latino, 1% as Middle Eastern, and 8% as other.

Materials

The men in these vignettes remained smart, nurturant, social, and healthy but the ethics and resources of the parents varied (see other vignettes via OSF link).

Example Vignette (see other vignettes via OSF link)

High Parental Ethics Low Parental Resources (Ethical parents from hereon).

Derek is 31 and single, and lives near your city. He enjoys playing baseball in the summer months and being outside. He loves to spend quality time with his niece and nephew. Derek’s parents are not wealthy. Their neighbors and friends remark that they work hard and always encourage it; they would not even accept gifts from their team members, let alone bribes. Everyone who knows Derek thinks he has incredible potential and is very friendly.

Low Parental Ethics High Parental Resources (Unethical parents from hereon).

Derek is 31 and single, and lives near your city. He enjoys playing baseball in the summer months and being outside. He loves to spend quality time with his niece and nephew. Derek’s parents are very wealthy. The neighbors and friends remark that they sometimes engage in bribery to fill their pockets without doing a lot of real work. Everyone who knows Derek thinks he has incredible potential and is very friendly.

Results

Women’s ratings

Mixed effects models for changes in women’s ratings are reported in Table 1. We found a significant interaction between traits and ethics (ps < 0.001; Table 1). Simple effects were further examined and presented in Fig. 1b; similar to Study 1, ratings were significantly higher for sons of ethical parents than for sons of unethical parents for all traits, except dominance and short-term attractiveness (Table 2).

Men’s ratings

Mixed effects models for changes in men’s ratings are reported in Table 1. We found a significant interaction between traits and ethics (ps < 0.05; Table 1). Simple effects were further examined and presented in Fig. 2b; similar to study 1, ratings were significantly higher for sons of ethical parents than for sons of unethical parents for all traits, except for dominance and short-term attractiveness (Table 2).

Discussion

Men who had ethical parents with relatively limited resources were evaluated as kinder, more prestigious, more intelligent, and more suitable for the long term than men who had unethical parents with abundant resources. It is not clear whether holding men accountable for their natal families’ questionable ethics is a “socially desirable” response or a form of cross-generational sanctioning of unethical behavior. Similar to Study 1 discussion, sanctioning of unethical behavior should have led to lowered ratings across all traits. Our findings, however, undermine this argument, as ratings for all traits were not lowered; short-term attractiveness and physical dominance were unaffected. This pattern of findings shows that the ethical reputation of not just the individual but also close kin influences women’s and men’s evaluations related to mating and status. Given the stability of behavior over time, in study 3, we modified vignettes to vary men’s past ethical practices, specifically from their adolescent days, and current resources, but otherwise possessing the same desirable traits.

Study 3 (Developmental ethics)

Participants

A total of 61 women (M = 23.82 years; SD = 2.97) and 65 men (M = 28.52 years; SD = 2.19) from the U.S. participated in the surveys. About 54% of the women identified as White non-Latino, 25% as African American, 8% as Asian American, 7% as non-White Latino, 1% as Middle Eastern, and 4% as other. About 52% of the men identified as White non-Latino, 34% as African American, 8% as non-White Latino, 3% as Asian American, and 3% as other.

Materials

The men in both high and low (developmental) ethics vignettes remained smart, nurturant, social, and healthy. The resources and ethics parts of the vignettes were modified; while the resources concerned the man’s current resources, the ethics concerned his past.

Example Vignette (see other vignettes via OSF link)

High Developmental Ethics Low Current Resources (Ethical past/history).

Derek is 31 and single, and lives near your city. He enjoys playing baseball in the summer months and being outside. He loves to spend quality time with his niece and nephew. Derek is not wealthy. His peers and friends remark that his hard work was always praised in high school; he would not even accept gifts from friends in return for his help with homework. Everyone who knows Derek thinks he has incredible potential and is very friendly.

Low Developmental Ethics High Current Resources (Unethical past/history).

Derek is 31 and single, and lives near your city. He enjoys playing baseball in the summer months and being outside. He loves to spend quality time with his niece and nephew. Derek is very wealthy. His peers and friends remark that he used to be caught cheating on tests and assignments in high school. Everyone who knows Derek thinks he has incredible potential and is very friendly.

Results

Women’s ratings

Mixed effects models for changes in women’s ratings are reported in Table 1. We found a significant interaction between traits and ethics (ps < 0.001; Table 1). Simple effects were further examined and presented in Fig. 1c; similar to studies 1 and 2, ratings were significantly higher for men with an ethical past than for those with an unethical past for all traits, except dominance and short-term attractiveness (Table 2).

Men’s ratings

Mixed effects models for changes in men’s ratings are reported in Table 1. We found a significant interaction between traits and ethics (ps < 0.05; Table 1). Simple effects were further examined and presented in Fig. 2c; ratings were significantly higher for men with an ethical past than for men with an unethical past for all traits, except for short-term attractiveness similar to studies 1 and 2 (Table 2), and prestige (not dominance) as opposed to studies 1 and 2.

Discussion

Women’s ratings showed the same pattern as studies 1 and 2 where ratings were lower for all traits in scenarios involving an unethical past except dominance and short-term mating. Interestingly, men’s ratings showed a difference from those of studies 1 and 2. Similar to studies 1 and 2, ratings for kindness, intelligence, and long-term mating attractiveness for wealthy men with an unethical past were lowered but not short-term attractiveness. As opposed to studies 1 and 2, male ratings for prestige did not differ between the two conditions; instead, they lowered the ratings for physical dominance for men with an unethical history. It is interesting to see a potential association between men’s attributions of physical dominance capabilities to other men based on their ethical reputation during a period of life characterized by a surge in steroid hormones and rapid somatic, cognitive, and social growth. Below we discuss this in detail.

Additional tests

Additional tests were conducted to examine whether age, ethnicity, relationship status, self-attractiveness ratings, and contraceptive use (women only) affected ratings (Table 3). Among women, younger age was marginally associated with higher ratings. Among men, relationship status significantly influenced their ratings. However, pair-wise comparisons between relationship statuses showed a significant difference only for ratings between polyamorous relationships and divorced or separated (p = .044). While men in polyamorous relationships significantly reported higher ratings than divorced or separated men, the comparison may be less meaningful as there were only two men in polyamorous relationships.

Table 3.

Results of mixed effects models for age, ethnicity, relationship status, self-attractiveness ratings, and contraceptive use.

| Gender | Model | SS | df | MS | F | p | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Ethics | 81,421 | 1 | 81,421 | 118.77 | < 0.001 | 0.03 | 0.15 |

| Vignette | 1083 | 2 | 542 | 0.79 | 0.456 | |||

| Survey Group | 632 | 1 | 632 | 0.92 | 0.338 | |||

| Age | 2,654 | 1 | 2654 | 3.87 | 0.051 | |||

| Ethnicity | 1343 | 5 | 269 | 0.39 | 0.854 | |||

| Relationship status | 3089 | 4 | 772 | 1.13 | 0.346 | |||

| Self-attractiveness Ratings | 14 | 1 | 14 | 0.02 | 0.887 | |||

| Contraceptive Use | 232 | 1 | 232 | 0.34 | 0.562 | |||

| Ethics x Vignette | 946 | 2 | 473 | 0.69 | 0.502 | |||

| Men | Ethics | 37,650 | 1 | 37,650 | 79.39 | < 0.001 | 0.03 | 0.16 |

| Vignette | 484 | 2 | 242 | 0.51 | 0.601 | |||

| Survey Group | 1280 | 1 | 1,280 | 2.7 | 0.102 | |||

| Age | 37 | 1 | 37 | 0.08 | 0.781 | |||

| Ethnicity | 2190 | 5 | 438 | 0.92 | 0.467 | |||

| Relationship status | 7952 | 8 | 994 | 2.1 | 0.039 | |||

| Self-attractiveness Ratings | 549 | 1 | 549 | 1.16 | 0.283 | |||

| Ethics x Vignette | 1419 | 2 | 709 | 1.5 | 0.224 |

In mixed effects models that tested for sex differences, we found a significant two-way interaction effect between sex and ethics, and between traits and ethics (Table 4). In follow-up tests, we found that women’s ratings were higher than men’s ratings for high ethics (t = -2.08, p = .038), in line with previous findings showing higher endorsement from women than men for values related to care and harm95but the sexes did not differ in ratings for low ethics (t = -0.07, p = .943). Pairwise comparisons for traits and ethics showed similar patterns reported above; ratings were significantly higher in high ethics than in low ethics for all traits (ps < 0.001), except short-term attractiveness and dominance. We also found a significant three-way interaction effect between sex, ethics, and traits (Table 4). We found significant two-way interaction effects for long-term attractiveness (p = .051) and kindness (p < .001), and further examined simple effects. For long-term attractiveness, we found that women’s ratings were significantly higher than men’s ratings for high ethics (t = -2.70, p = .007), but not for low ethics (t = -0.40, p = .688). For kindness, we found that women’s ratings were marginally higher than men’s ratings for high ethics (t = -1.92, p = .056), but not for low ethics (t = 1.70, p = .090).

Table 4.

Results of mixed effects models for sex differences on changes in women’s and men’s ratings across vignettes.

| Model | SS | df | MS | F | p | Marginal R2 | Conditional R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 925 | 1 | 925 | 1.63 | 0.202 | 0.03 | 0.16 |

| Ethics | 115,704 | 1 | 115,704 | 204.03 | < 0.001 | ||

| Trait | 12,780 | 5 | 2556 | 4.51 | < 0.001 | ||

| Survey Group | 166 | 1 | 166 | 0.29 | 0.589 | ||

| Sex x Ethics | 5230 | 1 | 5230 | 9.22 | 0.002 | ||

| Sex x Traits | 3752 | 5 | 750 | 1.32 | 0.251 | ||

| Ethics x Traits | 93,082 | 5 | 18,616 | 32.83 | < 0.001 | ||

| Sex x Ethics x Traits | 8021 | 5 | 1604 | 2.83 | 0.015 |

General discussion

The main findings that we discuss below are the following: (a) reputation about men’s personal ethics trumps that of resources in status- and mating-relevant evaluations about them, (b) men’s ethical reputation from an earlier developmental stage and that of their parents have largely similar effects on mating-relevant evaluations about them and (c) the sexes differ in evaluations of men’s status based on their adolescent ethical reputation. As we detail below, these findings necessitate clarification of the concepts of status and resources. They also warrant a reassessment of the relative significance of, and links between, status and resources in mate preferences.

Ethical reputation trumps resources in evaluations of men’s status and mating-relevant characteristics

Women and men pay attention to the ethical reputation of potential mates and competitors. This finding makes the most sense when discussed in terms of recent, empirically based proposals on status allotment. Women prefer high-status men as mates2and among the most status-increasing criteria are the following: being a trusted group member, always being honest, being kind, being intelligent, and being a hard worker. By contrast, being known as a thief, getting dismissed from school, and bringing social shame to one’s family were among the most status-decreasing criteria91. Further, even though women, compared to men, show an enhanced preference for mates’ resource acquisition ability, there appears to be no sex difference in how this ability affects men’s and women’s status except in the specific realm of hunting; hunting ability enhances men’s status more than women’s91. Similarly, holding a leadership position influences men’s status more than women’s91.

The potential benefits of a hunting reputation have been examined in some detail, and before moving forward, it is relevant to summarize recent discussions. A plausible argument has been that hunters may be better providers96,97. Ancestral women, with their higher load of parental investment, would have appreciated partners who were better providers. This conjecture is still being debated, and it is unclear whether better hunters’ mates or the hunters themselves are consistent recipients of better nutrition, raising uncertainty about the centrality of the family provisioning hypothesis98,99. Secondly, although not substantiated by overwhelming evidence, it remains possible that better hunters are sought after by women as mates (and men as coalitional members) because they signal inimitable qualities of mental and physical fitness100,101. Work with the Hadza, for example, has shown a small but clear sex difference in ranking motives for food acquisition and sharing; while family provisioning is important to both sexes, men are more likely than women to prioritize skill signaling over family provisioning102. Considering the opportunity cost associated with the norm of widely sharing hunted meat with community members, it has been argued that hunting is probably a signal of generosity or commitment to the group rather than cryptic qualities related to hunting prowess103. Compared to examples of fitness signals in other species demonstrating high signal efficacy, e.g., peacock feathers and stotting behavior in gazelles, hunting can often be a solitary activity with a limited audience to directly assess a hunter’s skill, strength, or ecological knowledge. By contrast, a hunter’s generosity toward the community is conspicuous103. Other research in egalitarian societies has also shown that leaders are expected to keep less to themselves and share more104. Note that generosity has also been linked to the ability to generate material benefits105. These findings and those of the current study align with cross-cultural work that shows that men’s benefit generation ability and willingness are given the highest status, whereas cost infliction ability and willingness with no apparent benefit to a group do not enhance status106. Moreover, individuals assume their status levels depending on the value they think they provide to a group107. In the current study, men’s (and women’s) attribution of high prestige to ethical men despite their relatively low financial standing is also explicable within the same framework; prestige accordance is a display of enhanced support for and deference to those who appear to reliably generate benefit for others55,69. Less able hunters, for example, prefer to join camps of better hunters rather than avoid them for fear of competition for access to resources including mates103,108.

Although resource acquisition ability by men and women does not show a sex difference in status associations, marrying a poor person diminishes women’s status more than men’s91. Women’s status compared to men’s is enhanced by marrying someone with more money than themselves91. However, securing intelligent mates also raises women’s status more than men’s91. While it is true that intelligence and income are strongly correlated109it is also true that intelligence and perceptions of morality and prosociality are positively correlated110 (but also see, Munoz Garcia et al. (2023) for links between intelligence and dishonest behavior111). In the current study, too, ethical men received higher intelligence and prestige scores than unethical, wealthy men from both men and women. Income is one of several social status indicators112and because women are hypergamous, we can expect them to show enhanced preferences for status indicators. It is not, however, clear that women’s preference for high-status men has been evolutionarily sustained by the direct benefits women gained through men’s family provisioning.

Parental ethics trumps parental resources in evaluations of men’s status and mating-relevant characteristics

While men’s mating-relevant characteristics (physical activity, intelligence, and care toward family and pets) in the ethical-but-unwealthy family category and those in the unethical-but-wealthy family category remained the same, the wealth and ethical reputation of the parents varied; some of the men had wealthy parents with questionable ethics and others had ethical parents with less wealth. Parental income and education113,114 are indicators of socioeconomic status, and economic resources are one of the primary cues in women’s mate choice. Therefore, fine men from wealthy families regardless of parents’ ethical inclinations should offer better economic prospects through large inheritance possibilities. Intelligent, loving sons of wealthy but unethical parents were, however, rated lower in prestige, intelligence, kindness, and long-term mating attractiveness than similarly credentialed sons of ethical but non-wealthy parents. There is the possibility of family wealth being confiscated or lost eventually should the dishonesty grow more chronic and get fully exposed. WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) communities are typically characterized by individualism, atomized families, limited kinship networks, high relational mobility, bilateral inheritance opportunities115,116 and stronger responsiveness to monetary incentives117. If it were cultural input that primarily shaped mate preferences, and input from market economies and globalized communities emphasized the role of economic resources in status formation and mating decisions, then it does not easily follow that young WEIRD individuals should base their mating and status assessments of smart, nurturant, and loving men in terms of their parents’ ethical rather than economic status only to steer clear of potential inheritance loss.

Also note that men’s and women’s evaluations were aligned. What appears to be relatively invariant across cultures is status gained or lost through social reputation based on helpful or unhelpful acts, respectively, which benefits or taints the social prospects of not only the individual in question but also their kin70,91. Thus far it is reasonable to conclude that wealthy men are assets to potential mates and friends but not at the cost of questionable ethical reputations associated with them or their parents.

Sex-differences in status assessments based on men’s adolescent ethics

Evaluations of physical dominance and short-term mating attractiveness were not affected by men’s ethical reputation or information on their wealth. Physical dominance is more reliably gauged visually through morphological features. For example, facial and bodily dominance are honest signals of success in physical competition118–120. Further, men’s short-term mating attractiveness is generally predicted by measures of masculinity and dominance, and perceptions of physical attractiveness87,121,122typically referred to as good gene indicators123. Unlike earlier studies, even the costs typically associated with risk-taking behaviors did not seem to enhance the unethical men’s short-term mating attractiveness124,125. There has, however, been a shift in the discussion of the utility of women’s short-term mating strategies; these may be a means to men with higher mate value126but a recent study lent support to a dual mating strategy88; affair partners were reported to be more physically attractive than primary partners who were more parentally attractive.

Another finding worth discussing is the sex difference in status-evaluations related to adolescent ethical history. Whereas women’s ratings presented the same pattern as with personal and parental vignettes, men’s ratings showed a reversal in ratings of prestige and physical dominance. Women gave low prestige ratings to men with unethical pasts, but men gave them low physical dominance ratings. Physical dominance is related to muscularity127 and strength128. Boys develop muscularity concerns129 affecting their self-esteem during adolescence130and low self-esteem has been positively correlated with adolescent delinquency131. Research has also shown a negative correlation between adolescent insecurity and popularity-motivated prosocial behaviors132–134. From an intrasexual competition perspective, men are more predisposed to physical competition135 and to other men’s dominance cues136,137especially when they are heterosexual and primed with cues of the opposite sex138. In the current study, every scenario dealt with questions related to long-term and short-term mating attraction to women alongside other mating-relevant items, potentially acting like a priming condition throughout. It is possible that men associated the various minor delinquencies with weaker physical dominance. To the extent that physical capacity at adolescence is predictive of physical capacity in adulthood139it makes sense that men lowered ratings of physical dominance for men with unethical adolescent histories. In terms of current prestige, however, the men in both scenarios were similarly intelligent, friendly, and embedded in wide social networks, and thus the prestige ratings were not affected. For women, unlike men, cues of physical dominance may not be as salient unless they are primed for self-protection138and insofar as prosocial behavior is stable from adolescence to adulthood140,141it makes sense that women gave higher prestige ratings to men with ethical histories. Of course, these explanations require empirical verification.

The findings also highlight the significance of both physical dominance and ethical reputation in contributing to high status; “kindness” need not be considered an alternative strategy mostly employed by less dominant men, and physically dominant men need not be rarely ethical. Physical strength positively affects perceptions of men’s status142. Leaders in egalitarian societies are physically dominant and relationally wealthy104. Even in modern democratic societies like the U.S., taller men win more votes in presidential elections143; taller men are accorded not only higher formidability-related status but also higher intelligence and generosity144. Also, political leaders who display virtuous behaviors are more influential and those who display psychopathic behaviors become less influential145. The bottom line is that displays of prosociality are expected of high-status individuals104,106,146 even though they may choose different recipient groups as beneficiaries of their generosity and good will147.

Conclusion

Resource acquisition ability is typically discussed in terms of the acquisition of wealth or other tangible items (e.g., food, gifts) mainly in the service of a man’s nuclear family7but it is essential to extend it to other kinds of resources such as general social standing and relational wealth. Occupational prestige, for example, has health benefits controlling for income114. Social support in traditional societies is associated with better health148. Relational wealth, too, provides health and fertility benefits, and is heritable149. Even parental income and children’s mental health have been found to share a genetic link150. Theoretical proposals are certainly inclusive of some of these additional phenomena72but in our assessment, empirical studies, especially in WEIRD populations, seem to disregard the multiple interpretations of resources. Many studies discuss preferences related to long-term mating and short-term mating as strategies to direct attention to cues of resources (direct benefits) and good genes (indirect benefits). There is uncertainty about the nature of benefits that facilitated the evolution of women’s preference for wealthier, kinder, and more intelligent mates.

A limitation may be that not being wealthy and not being ethical may not be equivalent in their dosages; the former may be judged less negatively than the latter. However, given that temporally based mate preferences are largely discussed as diverging along the lines of good gene- and good dad-indicators, studies investigating long-term preferences tend to focus on men’s resources and men’s attention toward their nuclear families. Broader social norms and niceties are not considered as being directly relevant to mating in the way that resources and good dad/partner qualities are. Despite portraying the norm violators as both wealthy and likely to be attentive to their families, the current study’s findings, revealing an overall preference for generally ethical men to affluent men as long-term mates, encourages us to rethink the nature of social status and its role in influencing mate preferences. Also, as Table 3 shows, the differences in vignettes in each category, i.e., the differences in the types of ethical and unethical acts did not influence ratings.

Another limitation is that the current study did not adequately separate wealth from ethically based status; for example, smart, friendly, and ethical men aged about thirty years may eventually be financially successful. It is relevant to mention the results of another vignette-based study done about two decades ago that pitted men’s creativity and wealth151. The study used stronger resource-poor language than used in our study: “To make extra money to support his schooling, he sold…he will probably never make very much money”, and “created huge cash flow problems…. has very little money left”. An unexpectedly consistent finding was that women (across all fertility levels) preferred these resource-poor but creative men over wealthy, lackluster men as long-term mates despite both categories of men being presented as “highly desirable” or “most eligible bachelors”. The authors wondered why women did not prefer money over creative displays and suggested that they were probably convinced of creative men’s future resource acquisition potential. Two points to consider are: women’s reproductive value and fecundity peak during the late teens/early twenties and mid-twenties to early thirties, respectively86and the average preferred and observed age difference between spouses is about three years1,2. If women’s preference for wealth is one instance of evidence of adaptation to gain access to resources, this preference should be most evident during the life stage where women are most likely to gestate and lactate. By this logic, young 24-year-old-women in our study should favor the wealthier 30-year-old men, or at least the ones with wealthier parents, and not wait for the less wealthy 30-year-old men, or the ones with ethical parents to be eventually wealthier. While we of course cannot deny the importance of wealth in general, our findings question the primacy of direct benefits via wealth in young women’s choice of high-status long-term mates. It seems more parsimonious to state that women’s mate preferences track men’s status hierarchies where status is conferred by the group in light of locally valued skills and qualities.

A recent study on mate preferences in a Jewish community—Haredi—is illustrative of this point; the study demonstrates that not only is the role of economic resources downplayed in determining men’s status, but it also shows sex-related reversal in mate preferences152,153. Haredi men, compared to Haredi women, rank economic resources as highly desirable in potential mates; this makes sense as Haredi men climb the status hierarchy by mastering religious knowledge, and Haredi women focus on bringing in resources in order for their mates to be able to devote more time to religious pursuits. This study shows that status is not accorded to (and women do not favor) men’s behavior leading to resource acquisition for the benefit of their nuclear families. Instead, status is accorded to (and women prefer) men’s behavior that is considered beneficial to the community at large, specifically the pursuit of spiritual enlightenment and thereby the promise of spiritual advisement for the perceived betterment of a community.

A point to stress here is that we are not implying that individuals need to be genuinely and consistently ethical/moral to be preferred as mates or friends. We should only expect that they will try to appear and be known as ethical70,103; it is highly reasonable to expect that many would do what they can to serve themselves and their immediate kin first154–156 but not at the risk of being labeled harmful or unhelpful to the larger group. These kinds of simultaneous negotiations with multiple individuals in nested groups157 require high levels of social cognition and executive functioning158,159. More work is needed to examine socially adept displays of magnanimity and integrity, which will likely include vocal and verbal displays (along with other expressive modalities160,161), considering that we are a gregarious and loquacious species55,162,163. Also, ethical reputations can vary depending on group affiliations; one group’s morality may not overlap with that of another group. Future studies need to include samples from different cultures (with culture-sensitive vignettes, as needed), and also investigate women’s and men’s status- and mating-relevant evaluations of women by pitting ethical reputation against their physical attractiveness, both of which men potentially prioritize in mates19,86,164.

Finally, did participants simply provide socially desirable responses? Firstly, participants were anonymously recruited through an external company and completed the study in a virtual format, which should have minimized social desirability concerns. As mentioned under Methods, the use of difference scores and distractor tasks between the pre- and post-vignette exposures should have somewhat countered potential acquiescence bias. Also, it is not entirely convincing that 21st century young WEIRD individuals consider it socially desirable to amplify evaluations of men’s intelligence, kindness, prestige, and long-term attractiveness based on their parents’ and adolescent ethical reputation rather than their current personal character and potential. Additionally, what may be construed as socially desirable responding is compatible with an evolutionarily informed normative psychology account165,166. Given prestige-biased cultural learning and conformist transmission, the current findings may reflect our capacity for internalizing social norms and making normative judgements in partnership formations including mate choice, as suggested by the close tracking among prestige and prestige-linked traits such as intelligence and kindness based on ethical reputation. Prestige is a phylogenetically younger strategy than dominance, and this difference may influence evaluations for short-term mating contexts (typically favoring physical attractiveness and dominance) and long-term mating contexts (favoring prestige-indicators, which are also culture-dependent167 and sometimes overlaps with dominance-indicators), a matter that warrants further investigation. There is room for exploration of evolutionary trade-offs as well, that is the degree to which multiple desirable traits manifest simultaneously (say physical dominance- and prestige-markers). Integrating notions of social selection168,169evolutionary trade-offs170and gene-culture co-evolution165,171 in future work on mate choice will be informative.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Mackenzie Zinck’s assistance in creating the outline of the Qualtrics survey and some of the vignettes. The authors also extend sincere thanks to the three anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback.

Author contributions

SK and MLF developed the study design and vignettes. SK created the surveys with input from MLF, collected data with the help of Centiment Panel, wrote the first draft and further reviewed and edited the draft. TA analyzed and wrote up all of the results, prepared figures and tables, and reviewed and edited the draft. MLF collected the faces and reviewed and edited the draft.

Data availability

The data have been made available online at https://osf.io/bu85a/?view_only=c1d9df62cadd4fb6920f5cf0fe1f995a.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Buss, D. M. Sex differences in human mate preferences: evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behav. Brain Sci.12, 1–49 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buss, D. M. & Schmitt, D. P. Mate preferences and their behavioral manifestations. Annu. Rev. Psychol.70, 77–110 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aung, T., Conard, P., Crowell, D., Sanchez, J. & Pentek, W. Cross-cultural comparisons: Intersexual selection. in Encyclopedia of Sexual Psychology and Behavior (ed. Shackelford, T. K.) 1–14 (Springer International Publishing, 2023). 10.1007/978-3-031-08956-5_722-1

- 4.Walter, K. V. et al. Sex differences in mate preferences across 45 countries: A Large-Scale replication. Psychol. Sci.31, 408–423 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li, N., Bailey, J., Kenrick, D. & Linsenmeier, J. The necessities and luxuries of mate preferences: testing the tradeoffs. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol.82, 947–955 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trivers, R. Parental investment and sexual selection. in Sexual Selection Descent Man378 (1972).

- 7.Hughes, S. M. & Aung, T. Modern-day female preferences for resources and provisioning by long-term mates. Evolutionary Behav. Sci.11, 242–261 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang, G. et al. Different impacts of resources on opposite sex ratings of physical attractiveness by males and females. Evol. Hum. Behav.39, 220–225 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jonason, P. K. & Thomas, A. G. Being more educated and earning more increases romantic interest: data from 1.8 M online daters from 24 nations. Hum. Nat.33, 115–131 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopcroft, R. L. Sex, status, and reproductive success in the contemporary united States. Evol. Hum. Behav.27, 104–120 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hopcroft, R. L. High income men have high value as long-term mates in the U.S.: personal income and the probability of marriage, divorce, and childbearing in the U.S. Evol. Hum. Behav.42, 409–417 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunn, M. J. & Hill, A. Manipulated luxury-apartment ownership enhances opposite-sex attraction in females but not males. J. Evolutionary Psychol.12, 1–17 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunn, M. J. & Searle, R. Effect of manipulated prestige-car ownership on both sex attractiveness ratings. Br. J. Psychol.101, 69–80 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kruger, D. J. & Kruger, J. S. What do economically costly signals signal?? A life history framework for interpreting conspicuous consumption. Evolutionary Psychol. Sci.4, 420–427 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sundie, J. M. et al. Peacocks, porsches, and Thorstein veblen: conspicuous consumption as a sexual signaling system. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol.100, 664–680 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griskevicius, V. et al. Blatant benevolence and conspicuous consumption: when romantic motives elicit strategic costly signals. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol.93, 85–102 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hennighausen, C., Hudders, L., Lange, B. P. & Fink, H. What if the rival drives a porsche?? Luxury Car spending as a costly signal in male intrasexual competition. Evol. Psychol.14, 1474704916678217 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phillips, T., Ferguson, E. & Rijsdijk, F. A link between altruism and sexual selection: genetic influence on altruistic behaviour and mate preference towards it. Br. J. Psychol.101, 809–819 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barclay, P. Altruism as a courtship display: some effects of third-party generosity on audience perceptions. Br. J. Psychol.101, 123–135 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barclay, P. Strategies for Cooperation in biological markets, especially for humans. Evol. Hum. Behav.34, 164–175 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhogal, M. S., Galbraith, N. & Manktelow, K. Physical attractiveness, altruism and Cooperation in an ultimatum game. Curr. Psychol.36, 549–555 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lukaszewski, A. W. & Roney, J. R. Kind toward whom? Mate preferences for personality traits are target specific. Evol. Hum. Behav.31, 29–38 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnocky, S., Piché, T., Albert, G., Ouellette, D. & Barclay, P. Altruism predicts mating success in humans. Br. J. Psychol.108, 416–435 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farrelly, D. Altruism as an indicator of good parenting quality in long-term relationships: further investigations using the mate preferences towards altruistic traits scale. J. Soc. Psychol.153, 395–398 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farrelly, D., Clemson, P. & Guthrie, M. Are women’s mate preferences for altruism also influenced by physical attractiveness?? Evol. Psychol.14, 147470491562369 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farrelly, D. & King, L. Mutual mate choice drives the desirability of altruism in relationships. Curr. Psychol.38, 977–981 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore, D. et al. Selflessness is sexy: reported helping behaviour increases desirability of men and women as long-term sexual partners. BMC Evol. Biol.13, 182 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oda, R., Okuda, A., Takeda, M. & Hiraishi, K. Provision or good genes?? Menstrual cycle shifts in women’s preferences for Short-Term and Long-Term mates’ altruistic behavior. Evol. Psychol.12, 888–900 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhogal, M. S., Farrelly, D., Galbraith, N., Manktelow, K. & Bradley, H. The role of altruistic costs in human mate choice. Pers. Indiv. Differ.160, 109939 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo, Q., Feng, L. & Wang, M. Chinese undergraduates’ preferences for altruistic traits in mate selection and personal advertisement: evidence from Q-sort technique. Int. J. Psychol.52, 145–153 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhogal, M. S., Galbraith, N. & Manktelow, K. A research note on the influence of relationship length and sex on preferences for altruistic and cooperative mates. Psychol. Rep.122, 550–557 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts, G. Human cooperation: the race to give. Curr. Biol.25, R425–R427 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Vugt, M. & Iredale, W. Men behaving nicely: public goods as Peacock Tails. Br. J. Psychol.104, 3–13 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McAndrew, F. T. & Perilloux, C. Is self-sacrificial competitive altruism primarily a male activity? Evol. Psychol.10, 50–65 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tognetti, A., Dubois, D., Faurie, C. & Willinger, M. Men increase contributions to a public good when under sexual competition. Sci. Rep.6, 29819 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arnocky, S. et al. Actually, it does: Fatal errors in Judd. Evol. Behav. Sci. 17, 472–481 (2023). (2022).

- 37.Peñaherrera-Aguirre, M. Altruism does predict human mating success, albeit the effect sizes are relatively small. Evolutionary Behav. Sci.17, 482–488 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stavrova, O. & Ehlebracht, D. A longitudinal analysis of romantic relationship formation: the effect of prosocial behavior. Social Psychol. Personality Sci.6, 521–527 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allen, M. S., Robson, D. A., Mishra, M. & Laborde, S. A prospective and retrospective 10-year study of altruism and reproductive success. Evolutionary Behav. Sci.18, 299–307 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dawkins, R. The Selfish Gene (Oxford University Press,1989).

- 41.Buss, D. M. The Evolution of Desire: Strategies of Human Mating (Hachette, 2016).

- 42.Roberts, G. et al. The benefits of being seen to help others: indirect reciprocity and reputation-based partner choice. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci.376, 20200290 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bliege Bird, R. & Smith, E. A. Signaling theory, strategic interaction, and symbolic capital. Curr. Anthropol.46, 221–248 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Novakova, J. et al. Generosity as a status signal: Higher-testosterone men exhibit greater altruism in the dictator game. Evol. Hum. Behav.45, 106615 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raihani, N. J. & Barclay, P. Exploring the trade-off between quality and fairness in human partner choice. Royal Soc. Open. Sci.3, 160510 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khanipour, H., Pourali, M. & Atar, M. Prestige and dominance as differential correlates of moral foundations and its clinical implications. Pract. Clin. Psychol.9, 1–8 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amormino, P., Ploe, M. L. & Marsh, A. A. Moral foundations, values, and judgments in extraordinary altruists. Sci. Rep.12, 22111 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kruger, D. J. & Fitzgerald, C. J. Reproductive strategies and relationship preferences associated with prestigious and dominant men. Pers. Indiv. Differ.50, 365–369 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Snyder, J. K. et al. Trade-offs in a dangerous world: women’s fear of crime predicts preferences for aggressive and formidable mates. Evol. Hum. Behav.32, 127–137 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Von Rueden, C., Gurven, M. & Kaplan, H. Why do men seek status? Fitness payoffs to dominance and prestige. Proc. R Soc. B. 278, 2223–2232 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pandit, S. A. & van Schaik, C. P. A model for leveling coalitions among primate males: toward a theory of egalitarianism. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol.55, 161–168 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hare, B. Survival of the friendliest: Homo sapiens evolved via selection for prosociality. Ann. Rev. Psychol.68, 155–186 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cieri, R. L., Churchill, S. E., Franciscus, R. G., Tan, J. & Hare, B. Craniofacial feminization, social tolerance, and the origins of behavioral modernity. Curr. Anthropol.55, 419–443 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Henrich, J. & Muthukrishna, M. The origins and psychology of human Cooperation. Ann. Rev. Psychol.72, 207–240 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henrich, J., Chudek, M. & Boyd, R. The big man mechanism: how prestige fosters Cooperation and creates prosocial leaders. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci.370, 20150013 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Karthikeyan, S. et al. Articulatory effects on perceptions of men’s status and attractiveness. Sci. Rep.13, 2647 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Andreoni, J., Nikiforakis, N. & Stoop, J. Higher socioeconomic status does not predict decreased prosocial behavior in a field experiment. Nat. Commun.12, 4266 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Trautmann, S. T., Wang, X., Wang, Y. & Xu, Y. High-status individuals are held to higher ethical standards. Sci. Rep.13, 15111 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim, K. H. & Guinote, A. Cheating at the top: trait dominance explains dishonesty more consistently than social power. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull.48, 1651–1666 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brady, G. L., Kakkar, H. & Sivanathan, N. Perilous and unaccountable: the positive relationship between dominance and moral hazard behaviors. Journal Personality Social Psychology No Pagination Specified-No Pagination Specified. 10.1037/pspi0000448 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kakkar, H., Sivanathan, N. & Gobel, M. S. Fall from grace: the role of dominance and prestige in the punishment of High-Status actors. AMJ63, 530–553 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Kleef, G. A. When and how norm violators gain influence: dominance, prestige, and the social dynamics of (counter)normative behavior. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass. 17, e12745 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Kleef, G. A. et al. Rebels with a cause? How norm violations shape dominance, prestige, and influence granting. PLoS One. 18, e0294019 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hawkes, K. & O’Connell, J. F. Blurton jones, N. G. More lessons from the Hadza about men’s work. Hum. Nat.25, 596–619 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kelly, S. & Dunbar, R. I. Who dares, wins : heroism versus altruism in women’s mate choice. Hum. Nat.12, 89–105 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grafen, A. Biological signals as handicaps. J. Theor. Biol.144, 517–546 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zahavi, A. Mate selection—A selection for a handicap. J. Theor. Biol.53, 205–214 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cheng, J. T., Tracy, J. L., Ho, S. & Henrich, J. Listen, follow me: dynamic vocal signals of dominance predict emergent social rank in humans. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen.145, 536–547 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Henrich, J. & Gil-White, F. J. The evolution of prestige: freely conferred deference as a mechanism for enhancing the benefits of cultural transmission. Evol. Hum. Behav.22, 165–196 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Robertson, T. E., Sznycer, D., Delton, A. W., Tooby, J. & Cosmides, L. The true trigger of shame: social devaluation is sufficient, wrongdoing is unnecessary. Evol. Hum. Behav.39, 566–573 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sznycer, D. et al. Shame closely tracks the threat of devaluation by others, even across cultures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.113, 2625–2630 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sznycer, D. et al. Cross-cultural regularities in the cognitive architecture of pride. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.114, 1874–1879 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Philippe Rushton, J., Chrisjohn, R. D. & Cynthia Fekken, G. The altruistic personality and the self-report altruism scale. Pers. Indiv. Differ.2, 293–302 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Atari, M. et al. Morality beyond the WEIRD: how the Nomological network of morality varies across cultures. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol.125, 1157–1188 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Clark, C. B. et al. A behavioral economic assessment of individualizing versus binding moral foundations. Pers. Indiv. Differ.112, 49–54 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ścigała, K. A., Arkoudi, I., Schild, C., Pfattheicher, S. & Zettler, I. The relation between Honesty-Humility and moral concerns as expressed in Language. J. Res. Pers.103, 104351 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hilbig, B. E., Thielmann, I., Wührl, J. & Zettler, I. From Honesty–Humility to fair behavior – Benevolence or a (blind) fairness norm? Pers. Indiv. Differ.80, 91–95 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dores Cruz, T. D. et al. Gossip and reputation in everyday life. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci.376, 20200301 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Peters, K. & Fonseca, M. A. Truth, lies, and gossip. Psychol. Sci.31, 702–714 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Samu, F. & Takács, K. Evaluating mechanisms that could support credible reputations and cooperation: cross-checking and social bonding. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci.376, 20200302 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Margana, L., Bhogal, M. S., Bartlett, J. E. & Farrelly, D. The roles of altruism, heroism, and physical attractiveness in female mate choice. Pers. Indiv. Differ.137, 126–130 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 82.Miller, G. A. The magical number seven, plus or minus two: some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychol. Rev.63, 81–97 (1956). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cowan, N. The magical mystery four: how is working memory capacity limited, and why?? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci.19, 51–57 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear Mixed-Effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw.67, 1–48 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B. & Christensen, R. H. B. LmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal Stat. Software82, (2017).

- 86.Conroy-Beam, D. & Buss, D. M. Why is age so important in human mating? Evolved age preferences and their influences on multiple mating behaviors. Evolutionary Behav. Sci.13, 127–157 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hughes, S. M. & Gallup, G. G. Sex differences in morphological predictors of sexual behavior: shoulder to hip and waist to hip ratios. Evol. Hum. Behav.24, 173–178 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 88.Murphy, M., Phillips, C. A. & Blake, K. R. Why women cheat: testing evolutionary hypotheses for female infidelity in a multinational sample. Evol. Hum. Behav.45, 106595 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 89.Eisenbruch, A. B. & Krasnow, M. M. Why warmth matters more than competence: A new evolutionary approach. Perspect. Psychol. Sci.17, 1604–1623 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Conroy-Beam, D. & Buss, D. M. How are mate preferences linked with actual mate selection?? Tests of mate preference integration algorithms using computer simulations and actual mating couples. PLoS One. 11, e0156078 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]