Abstract

Background

In calves with diarrhea, it is critical to accurately determine the severity of dehydration and provide adequate fluid therapy. However, objective criteria are still limited. The aim of this study, a prospective cohort diagnostic study, is to compare caudal vena cava maximum diameter with expiration (CVCmax), caudal vena cava minimum diameter with inspiration (CVCmin), and caudal vena cava collapsibility index (CVC-CI) measurements before and after fluid therapy and to establish cut-off values for distinguishing between moderately and severely dehydrated calves. Twenty-four calves, with their degree of dehydration assessed based on enophthalmos and skin elasticity duration, were divided into two equal groups. Group I: consisted of 12 calves with an estimated degree of dehydration of 8–10% and were considered moderately dehydrated (degree of enophthalmos 4–6 mm, skin elasticity duration (s) 2–5). Group II: consisted of 12 calves with an estimated degree of dehydration 10–12% and were considered severely dehydrated (degree of enophthalmos 6–8 mm, skin elasticity duration (s) 5–10). Clinical examination, complete blood count and blood gas analysis, hemodynamic parameters (heart rate, respiratory rate, capillary refill time (CRT), L-lactate, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and mean arterial pressure (MAP)) and ultrasonographic examinations were performed for 48 h: before treatment (hour 0), immediately after the first fluid bolus, and at hours 8, 24, and 48 after the first fluid bolus. The Friedman test was used for within-group comparisons over time, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for between-group comparisons at different time points. Categorical data were analysed using the chi-squared test, and Fisher’s exact test was used when expected cell counts were less than 5. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to determine the sensitivity, specificity, and cut-off (lower limit) of CVC diameter and CVC-CI (%) compared with selected parameters (SBP, DBP, MAP, and L-lactate) to discriminate between moderate and severe dehydration. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

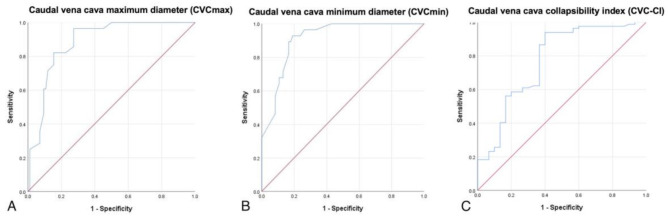

CVCmax and CVCmin increased significantly after treatment in diarrheic calves (P < 0.05). Additionally, a significant decrease in CVC-CI (%) was observed in the treated diarrheic calves. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis showed that the area under the curve (AUC) of CVCmax was 0.885 (95% CI: 0.823–0.946; P < 0.001), with 82% sensitivity and 85% specificity at the intercept point of 1.05, the AUC of CVCmin was 0.913 (95% CI: 0.861–0.964; P < 0.001), with 89% sensitivity and 84% specificity at the intercept point of 0.66, and were the most reliable parameters in differentiating between moderate and severe dehydration.

Conclusion

A significant increase in CVCmax and CVCmin diameters, along with a significant decrease in CVC-CI, was observed with fluid therapy. The CVCmax and CVCmin diameters can provide valuable information for distinguishing between moderately and severely dehydrated calves.

Keywords: Calf, Dehydration, Neonatal diarrhea, Caudal vena cava, Caudal vena cava collapsibility index

Background

Calves with neonatal diarrhea often develop hypovolemic shock due to dehydration from fluid and electrolyte loss. Insufficient fluid therapy in calves with neonatal diarrhea is associated with increased morbidity, letality [1, 2].

Although clinical findings, complete blood count and blood gas analysis, hemodynamic parameters and urine specific gravity can be used to assess the severity of dehydration and response to fluid therapy in human and veterinary medicine, their sensitivity and specificity still need improvement [2–9]. The cornerstone of treatment for hypovolemic shock is the rapid administration of large volumes of fluids. If hypovolemic patients are not adequately resuscitated, they risk progressing to multiple organ failure. Fluid therapy aims to restore circulating volume and improve tissue perfusion. However, determining the optimal amount of fluid required can be challenging. Insufficient IV fluid administration can result in poor tissue perfusion, ischemia, anaerobic metabolism, and ultimately, cell death and patient mortality [1–6]. Therefore, numerous studies have been initiated in veterinary and human medicine to develop more reliable and accurate methods for assessing these parameters [10–13].

In recent years, ultrasound has become a widely used hemodynamic tool to determine fluid balance in human medicine [14, 15]. Ultrasound measurement of inferior vena cava (IVC) diameter and its respiratory variation, as well as the calculation of the inferior vena cava collapsibility index (IVC-CI), are performed in cases of hypovolemia, intravascular status assessment, and monitoring response to fluid therapy in human medicine [16–19]. The inferior vena cava (Idem. CVC) can assess changes in volume status earlier than traditional vital signs [15, 18].

The caudal vena cava is the largest vein in the body, known for its high compliance, absence of valves, and thin, elastic walls, which allow it to dilate easily. It is not influenced by compensation mechanisms that increase vascular resistance, making it highly responsive to changes in hydration status [20–22]. The caudal vena cava diameter decreases significantly during fluid volume depletion and rapidly expands during fluid therapy. Therefore, it may be a valuable tool for assessing the severity of dehydration and monitoring the response to fluid therapy [20–22]. During spontaneous breathing, the diameter of the CVC shrinks during inspiration and the diameter of the CVC expands during expiration. These changes in vessel diameter due to respiratory motion and the relative change of the vessel during the respiratory cycle are evaluated as the CVC-CI. The CVC-CI reflects intravascular volume status and can be used to determine fluid responsiveness [7, 8, 23–27]. As intravascular volume decreases, the percentage of collapse and the CVC-CI increase [28].

There are a few studies on ultrasonographic measurement CVC diameter in veterinary medicine [2, 27, 28]. These studies focus on the measurement of CVC diameter from different views, the determination of CVC diameter values, changes in CVC diameter associated with fluid loss, and the prediction of fluid response using CVC-CI. A study conducted in calves suggests that the CVC diameter can be easily assessed using ultrasound in calves under 4 months of age, and that CVC diameter can be used to evaluate intravascular volume status [2]. However, no studies have been conducted on long-term fluid therapy and the monitoring of changes in CVC diameter and CVC-CI. This prospective cohort diagnostic study was designed with the hypothesis that CVC diameter and CVC-CI can be used to evaluate hemodynamic changes in dehydrated calves. The aim of this study is to compare caudal vena cava maximum diameter with expiration (CVCmax), caudal vena cava minimum diameter with inspiration (CVCmin), and caudal vena cava collapsibility index (CVC-CI) measurements before and after fluid therapy and to establish cut-off values for distinguishing between moderately and severely dehydrated calves.

Materials and methods

Animal material and group design

Calves with neonatal diarrhea from small and medium-sized farms in Konya and its surroundings were brought to the Animal Hospital of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Selcuk University by their owners for diagnosis and treatment. The study animals consisted of 24 calves, aged 2–15 days, with acute diarrhea. Of these, 13 were male and 11 were female, and they were divided into Group 1 (8 males, 4 females) and Group 2 (5 males, 7 females). The calves included 11 Holstein, 10 Simmental, 2 Mandafon, and 1 Danish Red. The calves were divided into two groups by scoring the degree of dehydration according to clinical examination findings [29]. Clinical examination, complete blood count and blood gas analysis, hemodynamic parameters (heart rate, respiratory rate, capillary refill time (CRT), L-lactate, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), mean arterial pressure (MAP)), and ultrasound were performed before treatment (hour 0), immediately after the first fluid bolus, and at hours 8, 24, and 48 after the first bolus. Calves that had received fluid therapy, were fed milk in the previous 12 h, exhibited abdominal distension, omphalophlebitis, respiratory distress, pneumonia, or were suspected of having congenital heart disease (heart murmur, distension of the jugular vein, etc.) were excluded from the study, as these factors could affect the measurement of caudal vena cava diameter.

Clinical criteria for determination of degree of dehydration

The degree of enophthalmos in the calves was determined by measuring the position of the eyeball in the orbit with a millimeter caliper. In addition, the duration of skin elasticity in the cervical region was determined in seconds (s) [29, 30]. Calves whose dehydration score was determined based on enophthalmos and skin elasticity were divided into two groups.

Group I

Consisted of 12 calves with an estimated degree of dehydration of 8%–10% and were considered moderately dehydrated (degree of enophthalmos 4–6 mm, skin elasticity duration (s) 2–5).

Group II

Consisted of 12 calves with an estimated degree of dehydration 10%–12% and were considered severely dehydrated (degree of enophthalmos 6–8 mm, skin elasticity duration (s) 5–10).

Clinical examination protocol

Information such as breed, age, sex, duration of illness, last feeding time, and whether any treatment was received prior to clinic presentation were recorded for all calves included in the study. Rectal temperature, heart rate (cardiac auscultation), respiratory rate, suckling reflex, posture, capillary refill time (CRT) and mucous membranes of the calves were assessed. The pulse (femoral or auricular) and the subjective temperature of the ears were not assessed in the calves. Clinical findings of the calves such as posture, sucking reflex, fecal consistency, and dehydration were scored according to the modified scoring system [31, 32] (Table 1). Body weights of the calves were measured before treatment. In addition, withers height and chest circumference were measured and recorded while the calf was standing. Fecal samples obtained from calves by rectal palpation were analyzed for Rotavirus, Coronavirus, Cryptosporidium parvum, Giardia, and Escherichia coli (F5) using a commercially available immunochromatographic rapid antigen test kit (BoviD-5 Ag, Bionote, Inc. Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Table 1.

Scoring is used to the evaluation of posture, sucking reflex, stool consistency and dehydration score in calves (Smith 2009, Boccardo et al. 2017, Dore et al. 2019)

| Scoring | Clinical findings |

|---|---|

| Posture | |

| 0 | Normal, related to the environment |

| 1 | Sternal position, swaying posture on standing |

| 2 | Continuous sternal, costal recumbency |

| 3 | Lateral recumbency, sometimes comatose |

| Sucking reflex | |

| 0 | Strong |

| 1 | Weak |

| 2 | Chewing movement or absent |

| Stool consistency | |

| 0 | Normal, shaped |

| 1 | Soft consistency |

| 2 | Mild diarrhea, semi-liquid, occasionally solid stools |

| 3 | Severe diarrhea, completely watery, no solids |

| Dehydration score | |

| 0 | Normal (<5%) |

| 1 | Mild dehydration (6%–8%) |

| 2 | Moderate dehydration (8%–10%) |

| 3 | Severe dehydration (10%–12%) |

Blood pressure measurements

Mean arterial pressure (MAP), systolic blood pressure (SBP), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were measured indirectly using an oscillometric technique with a cuff at the level of the Arteria mediana and Arteria digitalis communis on the forelimb of the recumbent calf (approximately at the midpoint of the metacarpus) (Compact 7, Medical Econet, Germany). The first reading was discarded, and the next 3 readings were averaged.

Complete blood count and blood gas analyses

Blood samples were collected from the jugular vein puncture using K3-EDTA tubes (5 mL) and heparin injectors (2.5 mL) for complete blood count and blood gas analyses, respectively. Analyses were performed within 5–10 min after blood collection, and total leukocyte count (WBC), lymphocytes (LYM), monocytes (MON), granulocytes (GRA), erythrocytes (RBC), hemoglobin (Hb), and hematocrit (HCT) were measured using a fully automated blood cell counter (MS4e Melet Schloesing Laboratories, France). Potassium (K+), pH, L-lactate, bicarbonate (HCO3-), and base excess (BE) were measured with an automated blood gas analyzer (ABL 90 Flex, Radiometer, Brea, CA, USA).

Measurement of caudal vena cava diameter by ultrasound

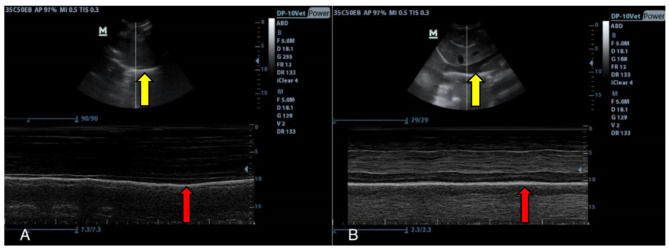

The calves were placed in the supine position and the hair was shaved in an area of approximately 10 cm x 10 cm, from the subxiphoid region to the umbilical cord and gel applied (Fig. 1). Caudal vena cava diameter measurements were performed using a 5 MHz convex transducer (Mindray DC-6 Vet, China) with a depth setting between 12 and 20 cm. The transducer cursor was placed transversely in the subxiphoid region facing the cranial side for B-mode imaging. The liver and diaphragm were imaged first and used as acoustic windows. After obtaining the CVC image, the transducer was rotated 90° clockwise and a longitudinal image of the CVC (2 differentiated horizontal and parallel lines) was obtained in the sagittal axis. The image was differentiated from the aortic vessel by the absence of arterial pulsation, its entry into the right atrium, deformation upon applying pressure to the abdomen with the probe, changes in diameter due to respiration, and the connection of the hepatic veins to the vena cava at an approximately 30° angle [2, 28, 33]. To determine the maximum visible width of the CVC, the transducer was moved slowly along the longitudinal axis of the CVC and the transducer was moved slightly so that the M-mode was usually perpendicular to the CVC. To standardize CVC diameter measurements, the M-mode examination was performed 2 cm caudal to the point where the hepatic vein enters the CVC, according to the method recommended by the American College of Emergency Physicians [34]. During the measurement, extreme care was taken to avoid stressing the calf, and minimal force was applied to the transducer so that the vessel diameter would not be affected by strong pressure [35]. The image obtained was frozen and the starting point was selected by pressing the set button key and the ultrasound was measured using the trackball to the second mark. During one respiratory cycle, the inspiratory and expiratory diameters of the CVC were measured in cm from the inner wall of the vessel lumen to the opposite inner wall (hyperechoic endothelial borders of the vessels were excluded) (Fig. 1). The transducer was oriented at lateral and medial angles to visualize the largest diameters in M-mode. The narrowest diameter of the CVC was considered the minimum diameter of the caudal vena cava during inspiration (CVCmin) and the widest diameter was considered the maximum diameter of the caudal vena cava during expiration (CVCmax). The procedure was repeated for 3 respiratory cycles and averaged to standardize the measurements. Data were excluded if the difference between measurements in any two images was greater than 0.2 cm. Ultrasonographic CVC diameter measurements were performed after 12 h of fasting [29, 36, 37]. All ultrasound procedures were performed by the same person (A.E.) and the calves were not sedated for the ultrasound measurements.

Fig. 1.

Schematic view (A) and method of measurement of the caudal vena cava from the subxiphoid (subcostal) area in the longitudinal axis (B) and view of the CVC in a calf. B-mode (top image); the M-mode line showing the liver, diaphragm and CVC crosses the CVC perpendicularly at the level of the diaphragm and is located 1.5–2 cm caudal to the entrance of the right hepatic vein into the CVC. M-mode (bottom image); longitudinal section and measurement of CVCmin and CVCmax diameters with M-mode (C). The M-mode image shows 3 respiratory cycles (SA, right atrial entry; HV, hepatic vein; CVCmin, measurement during inspiration; CVCmax, measurement during expiration)

Calculation of CVC-CI (%)

The CVC diameter of each calf in 3 respiratory cycles was measured and averaged, and the CVC-CI was calculated. The value of CVC-CI was calculated using the formula: ([CVCmax-CVCmin]/CVCmax) x 100% [9, 38].

Treatment protocol

The calves were hospitalized for 48 h and an intravenous catheter was placed in the auricular vein. According to the degree of dehydration determined by clinical signs, the initial fluid bolus was calculated using the formula: Replacement fluid (L) = dehydration percentage (%) x body weight (kg) [39]. To minimize the risk of potential pulmonary edema, the initial fluid bolus was administered using an infusion pump at a rate of 32 mL/min over a period of 3–4 h. Daily maintenance fluid treatment was administered at a dose of 80 mL/kg [39], 8 h after the initial bolus treatment, which was delivered using an infusion pump at a rate of 32 mL/min over a period of 3–4 h. Base excess was determined from blood gas results, and the required amount of bicarbonate (mEq) was calculated using the following formula: Bicarbonate requirement (mEq) = body weight (kg) x base deficit (mEq/L) x 0.6 (L/kg) [39]. Isotonic 0.9% NaCl and 1.3% NaHCO3- solutions (Carbotek, Teknovet®, Istanbul) were administered taking into account the BE value. In calves diagnosed with hypoglycemia, 200 mL of 30% dextrose (30% Dextrose, Polifleks®, Istanbul) was added to their fluid therapy. All sick calves in the severe dehydration group received hydroxyethyl starch (HES) solution (6% HES, Voluven®, Germany), a colloid, at a dose of 10 mL/kg/hour prior to crystalloid treatment [39]. The calves were fed only 1.5–2 L of semi-skimmed (1.5% fat) milk twice a day during their hospital stay, as D-lactic acidosis was suspected. Hypothermic calves were gradually warmed with infrared heaters. All calves received the broad-spectrum β-lactam antimicrobial ceftiofur sodium (Ceftivil, Vilsan®, Istanbul) intramuscularly (IM) at a dose of 2.2 mg/kg twice daily, off-label, for the treatment of enteritis and secondary infections. Such antibiotics should only be used under specified conditions, under veterinary supervision and in the correct dose to prevent antimicrobial resistance and protect public health. As supportive treatment, 5 mL of subcutaneous (SC) vitamin C (Vita-C Vetoquinol, Novakim®, Kocaeli) and 2 mL of vitamins A, D and E (Ademin, Ceva-Dif®, Istanbul) were administered IM once a day.

Statistical analysis

Power analysis

Power analysis (https://clincalc.com/stats/samplesize.aspx. Updated June 23, 2024. Accessed September 16, 2024.) was performed to determine the optimal sample size for the study. The confidence interval (CI) for the dehydrated groups was 95% and the margin of error was 0.5 according to Cohen’s Delta. Considering the likelihood of dehydration in calves with diarrhea, evaluation of CVC diameter in healthy neonatal calves [2], and accepted the effect size as 0.15% (power = 85%), it was concluded that at least 22 calves should be included in the study group. Considering the results of the power analysis, it was deemed appropriate to include 24 calves in the study groups as 12 moderately and 12 severely dehydrated calves.

Analysis of variances

The SPSS 25 statistical program (IBM Corp. 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0 Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) was used to evaluate the data. The one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the assumptions of normal distribution (parametric or nonparametric) of the data. Due to non-parametric distribution, data were presented as median (min/max). In order to determine the significant difference between the time points of the evaluation in the same group, the Friedman’s test was used. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for the comparison of the study groups (group I and group II) at the difference time point of the evaluation. The chi-squared test was used to analyze categorical data. In cases where > 20% of the expected cell counts were less than 5, Fisher’s exact test was used. The Spearman correlation test was used to determine the correlation between continuous and ordinal variables, while the Pearson correlation test was used to determine the correlation between continuous and binary variables. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to determine the sensitivity, specificity, and cut-off (lower limit) of CVC diameter and CVC-CI (%) compared with selected parameters (SBP, DBP, MAP, and L-lactate) to discriminate between moderate and severe dehydration. A value of P < 0.05 was accepted for the significance level of the tests.

Results

Clinical examination findings

The enophthalmos and skin elasticity duration values for each calf in Group I and Group II at the time of study inclusion (before treatment) are presented in (Table 2). The physiological parameters and demographic characteristics of the calves included in the study are presented in (Table 3). The statistical significance of the clinical examination findings of the calves in both groups at different time periods is presented in (Table 4). Watery diarrhea, loss of sucking reflex, moderate or severe dehydration, prolonged CRT, sternal or comatose appearance, hypothermia, mucosal dryness, and depression were observed in all calves before treatment. Of the calves included in the study, 4 died, one calf in group I at 36 h, two in group II at 8 h and one at 36 h. Calves with improved general condition and suckling reflex were discharged at 48 h. The distribution of etiological agents detected in the feces of the calves was as follows: E. coli (F5) 58%, Rotavirus 25%, Coronavirus 17%, and C. parvum 21%. There was no difference in etiological agents between the two groups.

Table 2.

The enophthalmos and skin elasticity duration values for each calf in groups I and II at study inclusion (before treatment)

| Group I (moderately dehydrated) | Enophthalmos (mm) and skin elasticity (s) duration | Group II (severely dehydrated) | Enophthalmos (mm) and skin elasticity (s) duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 mm–4 s | 1 | 7 mm–10 s |

| 2 | 6 mm–5 s | 2 | 8 mm–9 s |

| 3 | 5 mm–2 s | 3 | 6 mm–8 s |

| 4 | 5 mm–5 s | 4 | 8 mm–6 s |

| 5 | 5 mm–5 s | 5 | 8 mm–10 s |

| 6 | 5 mm–5 s | 6 | 7 mm–9 s |

| 7 | 6 mm–4 s | 7 | 8 mm–5 s |

| 8 | 4 mm–5 s | 8 | 8 mm–10 s |

| 9 | 5 mm–5 s | 9 | 7 mm–10 s |

| 10 | 5 mm–4 s | 10 | 7 mm–9 s |

| 11 | 6 mm–4 s | 11 | 8 mm–10 s |

| 12 | 6 mm–4 s | 12 | 8 mm–10 s |

Table 3.

The comparison of age, sex, body weight, chest circumference, and withers height between the groups is presented with the median and range (minimum-maximum) values in parentheses

| Parameter | Group I (moderately dehydrated) | Group II (severely dehydrated) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (days) | 5 (2–12) | 3 (2–15) | P > 0.05 |

| Gender (male/female) | 8/4 | 5/7 | P > 0.05 |

| Body weight (kg) | 39.50 (28–56) | 40.50 (29.50–48) | P > 0.05 |

| Chest circumference (cm) | 79.25 (74–89) | 81 (73–87) | P > 0.05 |

| Withers height (cm) | 78.25 (70–88) | 77.50 (71–85) | P > 0.05 |

Table 4.

The comparison of clinical examination findings of calves within and between groups at set intervals is presented with the median and range (minimum-maximum) values in parentheses

| Parameter | Before-treatment | After the first fluid bolus | 8. hour | 24. hour | 48. hour | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rectal temperature (C°) (38.0–38.6)* | I. group | 37.85a (35.80–39) | 38.30ab (38-39.20) | 38.5b (38-39.30) | 38.35ab (37.80–38.60) | 38.50ab (37.80–38.80) |

| II. group | 34.80a (33-38.10) | 37.60ab (33.50–38.40) | 38.30b (36.10–39.90) | 38.30ab (35.30–39.10) | 38.15ab (37.80–38.90) | |

| P (intergroup) | < 0.05 | < 0.001 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | |

| Respiratory rate (/minute)(16–30)* | I. group | 40 (20–80) | 43 (17–84) | 36 (19–54) | 38 (20–50) | 36 (22–44) |

| II. group | 40 (18–55) | 40 (26–75) | 30 (16–48) | 32 (16–42) | 31 (18–35) | |

| P (intergroup) | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | |

| Heart rate (beats/min)(110–140)* | I. group | 140 (88–176) | 140 (120–180) | 136 (100–156) | 137 (90–170) | 128 (106–144) |

| II. group | 120ac (58–151) | 152b (124–180) | 138abc (112–150) | 120c (100–160) | 115c (110–124) | |

| P (intergroup) | < 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | < 0.05 | |

| Degree of dehydration | I. group | 2a (2–2) | 1b (1–1) | 1b (1–2) | 1b (0–1) | 1b (0–2) |

| II. group | 3a (3–3) | 1b (1–1) | 1b (1–3) | 1b (0–3) | 1b (0–1) | |

| P (intergroup) | < 0.001 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | |

| CRT (s) (< 2 s)* | I. group | 4a (4–4) | 3b (3–3) | 3b (3–4) | 2b (1–3) | 2b (1–4) |

| II. group | 5a (5–5) | 3b (3–3) | 3ab (3–4) | 2b (1–4) | 2b (1–3) | |

| P (intergroup) | < 0.001 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | |

| Posture | I. group | 2a (2–3) | 1ac (1–2) | 0bc (0–2) | 0bc (0–3) | 0b (0–1) |

| II. group | 3a (2–3) | 1ac (1–2) | 0bc (0–1) | 0bc (0–1) | 0b (0–0) | |

| P (intergroup) | < 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | |

| Stool | I. group | 3 (1–3) | 3 (1–3) | 3 (1–3) | 3 (0–3) | 1 (0–3) |

| II. group | 3a (3–3) | 2ac (2–3) | 1bc (0–3) | 1bc (0–3) | 1b (0–2) | |

| P (intergroup) | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | < 0.01 | < 0.05 | > 0.05 | |

| Sucking reflex | I. group | 2a (2–2) | 1b (0–2) | 0b (0–2) | 0b (0–2) | 0b (0–1) |

| II. group | 2a (2–2) | 1ac (1–2) | 0bc (0–2) | 0bc (0–2) | 0b (0–0) | |

| P (intergroup) | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | |

Note: The dehydration degree was determined based on enophthalmos (mm) and skin elasticity (s)

*: Reference values, Abbreviations: CRT, capillary refill time. Different letters (a, b, c) in the same row are statistically significant (P < 0.05).*Group I: moderately dehydrated calves; Group II: severely dehydrated calves

Complete blood count and blood gas findings

Hemogram and blood gas results of calves with neonatal diarrhea are shown in (Table 5). The WBC, GRA, RBC, HCT, and Hb values of the calves were significantly higher than those of the post-treatment hours. Venous pH, HCO3− and BE levels of the calves were significantly lower, and K+ and L-lactate concentrations were significantly higher before treatment (P < 0.05).

Table 5.

The complete blood count and blood gas analysis findings in dehydrated calves at set intervals is presented with the median and range (minimum-maximum) values in parentheses

| Parameter | Before-treatment | After the first fluid bolus | 8. hour | 24. hour | 48. hour | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (m/mm3) 7.95 (5.25–11.33)* | I. group | 17.84a (8.93–57.71) | 11.03ab (6.12–37.86) | 11.69ab (6.90-44.29) | 10.46ab (6-20.62) | 8.36b (3.89–20.09) |

| II. group | 22.64 (8.28–40.15) | 11.45 (5.21–25.56) | 21.25 (7.06–46.05) | 9.77 (5.93–47.90) | 9.25 (5.79–20.51) | |

| P (intergroup) | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | |

| LYM (m/mm3) 2.27 (1.70–3.53)* | I. group | 3.54 (2.48–38.89) | 2.73 (0.83–18.96) | 2.75 (1.77–28.56) | 3.76 (1.52–11.77) | 3.45 (1.61–14.84) |

| II. group | 9.42 (2.49–37.01) | 3.39 (1.39–21.95) | 7.39 (2.58–45.86) | 5.15 (2.63–47.75) | 5.46 (1.92–11.25) | |

| P (intergroup) | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | |

| MON (m/mm3) 0.34 (0.18–0.84)* | I. group | 0.69 (0.40–1.38) | 0.58 (0.27–1.43) | 0.50 (0.19–1.62) | 0.56 (0.21–2.51) | 0.52 (0.24–0.81) |

| II. group | 0.65 (0.16-4.74) | 0.36 (0.09–3.59) | 0.59 (0.09–3.78) | 0.55 (0.09–2.04) | 0.48 (0.28–3.42) | |

| P (intergroup) | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | |

| GRA (m/mm3) 4.76 (1.39–9.26)* | I. group | 9.99a (5.21–20.05) | 6.40ab (2.34–18.15) | 7.42ab (1.68–14.94) | 6.39ab (0.59–8.51) | 4.46b (0.76–11.32) |

| II. group | 9.01a (2.98–19.61) | 5.10ab (1.10-13.31) | 7.01ab (0.10-21.77) | 6.37ab (0.06–13.47) | 3.45b (1.66–5.84) | |

| P (intergroup) | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | |

| RBC (m/mm3) (7.89 ± 0.81)* | I. group | 10.08a (7.75–14.93) | 7.13b (5.74–11.09) | 7.94ab (6.59–11.37) | 8.19ab (5.76–11.08) | 7.78ab (5.66–11.79) |

| II. group | 9.99a (5.03–13.90) | 7.24b (4.37–9.76) | 8.59ab (3.63–10.76) | 9.30ab (7.08–10.43) | 9.25ab (6.06–11.57) | |

| P (intergroup) | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | |

| HCT (%) (33.10 ± 8.76)* | I. group | 43.20a (27.5–73.30) | 30.35b (20.20–53.70) | 33.80ab (23.10–55.70) | 32.55ab (19.70–53.10) | 32.90ab (18.70–54.70) |

| II. group | 42.50 (17.30–64.60) | 29.60 (14.90–42.10) | 35.30 (20.20–49.30) | 40.50 (28.70–46.60) | 37.70 (25.80–47.00) | |

| P (intergroup) | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | |

| Hb (g/dL) (9.55 ± 1.65)* | I. group | 13.85a (9.20–21.30) | 9.80b (7.30–15.80) | 11.15ab (8.10–16.70) | 10.15ab (6.60–15.70) | 10.10ab (6.60–16.80) |

| II. group | 14 (3.30–18) | 10.50 (5.50–14) | 12.10 (9.90–15.60) | 11.40 (8.30–13.70) | 11.15 (7.80–12.60) | |

| P (intergroup) | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | |

| pH (7.41 ± 0.03)* | I. group | 7.11a (6.92–7.32) | 7.33b (7.21–7.43) | 7.28ab (7.17–7.44) | 7.38b (7.28–7.44) | 7.37b (7.27–7.44) |

| II. group | 7.09a (6.88–7.27) | 7.30ab (7.19–7.33) | 7.33b (7.30–7.42) | 7.36b (7.30–7.39) | 7.39b (7.26–7.41) | |

| P (intergroup) | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | |

| K+ (mmol/L) (4.46 ± 0.30)* | I. group | 5.50a (4.40–8.10) | 4.30b (3.70–5.50) | 4.55ab (3.30–5.60) | 4.20b (3.10–6.40) | 4.60ab (3.90–6.30) |

| II. group | 6.80a (4.10–8.30) | 4.60b (4.10–6.50) | 4.60b (4-6.90) | 4.30b (3.80–5.40) | 4.45b (3.80–5.40) | |

| P (intergroup) | < 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | |

| Glucose (mg/dL) 103.00 (82.00– 137.00)* | I. group | 90 (28–161) | 84.50 (33–130) | 87 (15–153) | 78 (8-155) | 79 (63–139) |

| II. group | 83 (4-181) | 112 (35–193) | 75 (36–144) | 71 (30–143) | 73.50 (59–94) | |

| P (intergroup) | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | |

| L-lactate (mmol/L) 4.00 (2.60–5.20)* | I. group | 5.55a (0.50–9.30) | 4.45ac (0.90–8.80) | 2.15abc (0.50–7.20) | 1.80abc (0.40–6.60) | 1.4b (0.70–3.50) |

| II. group | 6.10a (0.8–15) | 5.80ac (2-13.20) | 2.60abc (2.10–10.80) | 2.40abc (1.40-6) | 1.60b (0.7-2) | |

| P (intergroup) | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | |

| BE (mmol/L) 0.25 (− 7.20–5.40)* | I. group |

-13a (-26.80–2.30) |

-3.55ab (-9.80-4.80) |

-4.30ab (-9.30-4.70) |

1b (-6.70-5.50) | 1.50b (-8-7.10) |

| II. group |

-13a (-22.90-1.70) |

-1.60ab (-6.30-3.70) |

-0.30b (-8-10.20) |

2.20b (-1.40-7.50) | 1.75b (-9-4.90) | |

| P (intergroup) | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | |

| HCO3− (mmol/L) (24.96 ± 3.66)* | I. group | 16.30a (5.60–25) | 22.45ab (17.90–29) | 22.55ab (19.20–29.60) | 26.25b (20–30) | 26.50b (18.90–31.10) |

| II. group | 16.30a (7.90–28.60) | 24.70ab (20-31.80) | 25.90b (17.80–34.70) | 28.20b (24.50–32.30) | 26.65b (18-29.70) | |

| P (intergroup) | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | |

*: Reference values, Abbreviations: WBC, total leukocyte count; LYM, lymphocytes; MON, monocytes; GRA, granulocytes; RBC, red blood cells; HCT, hematocrit; Hb, hemoglobin; K+, potassium; BE, base excess; HCO3−, bicarbonate. Different letters (a, b, c) in the same row indicate statistical significance ( P < 0.05). *Group I: moderately dehydrated calves; Group II: severely dehydrated calves

Ultrasound and blood pressure measurement findings

Ultrasound and blood pressure findings in calves with neonatal diarrhea are presented in (Table 6). Significant increases in SBP, DBP, and MAP after fluid therapy were generally observed in both groups. SBP was significantly lower in calves with severe dehydration compared to those with moderate dehydration before treatment (P < 0.05). CVCmax and CVCmin, increased statistically after treatment in dehydrated calves (P < 0.05). A statistically significant decrease in CVC-CI (%) was observed in calves with diarrhea after treatment. There was no difference in CVCmax and CVCmin between groups (P > 0.05). When compared between groups, CVC-CI (%) was higher in the before treatment period only in calves in group I (P < 0.05). The change in CVC diameter of a calf was visualized by ultrasound before and immediately after the first fluid bolus treatment (Fig. 2).

Table 6.

Blood pressure and CVC ultrasound findings in dehydrated calves at set intervals is presented with the median and range (minimum-maximum) values in parentheses

| Parameter | Before-treatment | After the first fluid bolus | 8. hour | 24. hour | 48. hour | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP (mmHg) (> 90 mmHg)* | I. group | 111.50a (78–152) | 145.50b (91–165) | 132ab (105–153) | 140b (67–172) | 140ab (99–169) | |

| II. group | 88a (60–127) | 151b (93–188) | 116ab (84–147) | 115ab (86–157) | 133.50b (114–163) | ||

| P (intergroup) | < 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | ||

| DBP (mmHg) (> 77 mmHg)* | I. group | 59.50a (39–92) | 84.50b (52–117) | 86b (64–101) | 85ab (29–122) | 80ab (65–132) | |

| II. group | 51a (40–85) | 83b (45–132) | 70ab (47–90) | 75ab (32–104) | 81.50b (75–98) | ||

| P (intergroup) | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | < 0.01 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | ||

| MAP (mmHg) (> 65 mmHg)* | I. group | 77a (52–108) | 99b (65–133) | 101.50ab (64–116) | 101.50b (42–138) | 93ab (82–144) | |

| II. group | 66a (47–99) | 106b (61–125) | 82ab (65–105) | 100ab (50–122) | 95,50ab (68–116) | ||

| P (intergroup) | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | < 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | ||

| CVCmax (cm) | I. group | 0.89a (0.71–1.14) | 1.63b (0.97–2.13) | 1.31ab (0.62–2.04) | 1.33ab (0.80–1.76) | 1.33ab (0.86–1.76) | |

| II. group | 0.88a (0.71–1.14) | 1.59b (1.11–2.39) | 1.07ab (0.96–1.75) | 1.11ab (1.04–1.51) | 1,21b (1.10–1.67) | ||

| P (intergroup) | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | ||

| CVCmin (cm) | I. group | 0.44a (0.30–0.68) | 1.10b (0.44–1.50) | 0.82ab (0.44–1.15) | 0.80b (0.44–1.24) | 0.71b (0.53–1.21) | |

| II. group | 0.48a (0.33–0.65) | 0.95b (0.72–1.91) | 0.79b (0.55–1.33) | 0.72ab (0.55–0.95) | 0.85b (0.68–0.95) | ||

| P (intergroup) | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | ||

| CVC-CI (%) | I. group | 50.83a (40-57.74) | 36.93b (23.48–54.63) | 41.70ab (21.87-45) | 32.90b (25.78–46.66) | 40.44b (21.87–57.73) | |

| II. group | 45.56a (28.88–57.89) | 33.56b (20.08–42.59) | 34.81ab (21-46.61) | 38.26ab (27.27–47.11) | 35.87ab (24.54–43.80) | ||

| P (intergroup) | < 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | ||

Note: Blood pressure was measured using the oscillometric technique with a cuff placed at the level of the Arteria mediana and Arteria digitalis communis on the forelimb of the recumbent animal, approximately at the midpoint of the metacarpus

*: Reference values, Abbreviations: SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure; CVCmax, caudal vena cava maximum diameter with expiration; CVCmin, caudal vena cava minimum diameter with inspiration; CVC-CI (%), caudal vena cava collapsibility index. Different letters (a, b) in the same row are statistically significant (P < 0.05). *Group I: moderately dehydrated calves; Group II: severely dehydrated calves

Fig. 2.

CVC diameter B-mode (top image) and M-mode (bottom image) views of the calf before fluid treatment (A), CVC diameter B-mode (top image) and M-mode (bottom image) views of the same calf after fluid treatment (B)

Correlation analysis

The results of the correlation analysis are shown in (Table 7). The degree of dehydration, CRT, posture, and sucking reflex of all calves included in the study were negatively correlated with CVCmax-CVCmin and positively correlated with CVC-CI (P < 0.05). Venous pH, BE, and HCO3− were positively correlated with CVCmax-CVCmin and negatively correlated with CVC-CI (%) (P < 0.05). RBC, HCT were negatively correlated with CVCmax-CVCmin and positively correlated with CVC-CI (%) (P < 0.05). CVCmax-CVCmin was positively correlated with SBP, DBP and MAP and negatively correlated with CVC-CI (%) (P < 0.05).

Table 7.

Spearman’s rank correlation of CVCmax, CVCmin, and CVC-CI with clinical examination, complete blood count and blood gas analysis and hemodynamic parameters before treatment in dehydrated calves (n:24) (*P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01)

| Variable | CVCmax | CVCmin | CVC-CI (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree of dehydration | -0.573** | -0.596** | 0.422** |

| CRT | -0.523** | -0.530** | 0.360** |

| Posture | -0.457** | -0.454** | 0.317** |

| Sucking reflex | -0.487** | -0.479** | 0.278** |

| pH | 0.526** | 0.492** | -0.286** |

| K+ | -0.359** | -0.380** | 0.338** |

| BE | 0.517** | 0.497** | -0.299** |

| HCO3− | 0.486** | 0.469** | -0.282** |

| WBC | -0.379** | -0.316** | 0.099 |

| RBC | -0.417** | -0.395** | 0.217* |

| HCT | -0.383** | -0.355** | 0.197* |

| Hb | -0.289** | -0.261** | 0.129 |

| SBP | 0.398** | 0.382** | -0.234** |

| DBP | 0.340** | 0.340** | -0.238** |

| MAP | 0.369** | 0.381** | -0.285** |

| CVCmax | 1.000 | 0.924** | -0.437** |

| CVCmin | 0.924** | 1.000 | -0.720** |

| CVC-CI (%) | -0.437** | -0.720** | 1.000 |

Abbreviations: CRT, capillary refill time; K+, potassium; BE, base excess; HCO3−, bicarbonate; WBC, total leukocyte count; RBC, red blood cells; HCT, hematocrit; Hb, hemoglobin; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure; CVCmax, caudal vena cava maximum diameter with expiration; CVCmin, caudal vena cava minimum diameter with inspiration; CVC-CI (%), caudal vena cava collapsibility index

ROC analysis results

The results of ROC analysis showed that the area under the curve (AUC) of CVCmax was 0.885 (95% CI: 0.823–0.946; P < 0.001), with 82% sensitivity and 85% specificity at the cut-off point of 1.05, AUC of CVCmin was 0.913 (95% CI: 0.861–0.964; P < 0.001), with 89% sensitivity and 84% specificity at the cut-off point of 0.66, were found to be the most reliable parameters for discrimination between moderate and severe dehydration (Table 8; Fig. 3).

Table 8.

The area under the curve (AUC), standard error, confidence interval (95%) values sensitivity, specificity, and cut-off (lower limit) of ultrasonographic and selected variables for discrimination between moderate and severe dehydration in calves before treatment

| Variable | AUC | Standard error | p value | Asymptotic 95% confidence interval | Sensitivity | Specificity | Lower limit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||||

| CVC-CI (%) | 0.771 | 0.055 | < 0.001 | 0.664 | 0.879 | 86 | 64 | 44.26 |

| CVCmax | 0.885 | 0.032 | < 0.001 | 0.823 | 0.946 | 82 | 85 | 1.05 |

| CVCmin | 0.913 | 0.026 | < 0.001 | 0.861 | 0.964 | 89 | 84 | 0.66 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 0.793 | 0.051 | < 0.001 | 0.692 | 0.893 | 78 | 69 | 123 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 0.799 | 0.053 | < 0.001 | 0.695 | 0.904 | 75 | 71 | 73 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 0.797 | 0.052 | < 0.001 | 0.695 | 0.899 | 82 | 72 | 88 |

| L-lactate (mmol/L) | 0.675 | 0.064 | < 0.01 | 0.550 | 0.799 | 71 | 67 | 4.30 |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; CVCmax, caudal vena cava maximum diameter with expiration; CVCmin, caudal vena cava minimum diameter with inspiration; CVC-CI (%), caudal vena cava collapsibility index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure

Fig. 3.

ROC analysis plot based on CVCmax (A), CVCmin (B), and CVC-CI (%) for discrimination between moderate and severe dehydration

Discussion

The evaluation of CVC diameter has been conducted in small animals, foals, and more recently, in calves [2, 27, 28]. However, our study is the first to evaluate the feasibility of ultrasound assessment of CVC and CVC-CI before and after fluid replacement in neonatal calves with diarrhea. This study may demonstrate that CVC and CVC-CI measurements can be used to evaluate treatment monitoring in the same way as other common parameters.

Hypovolemia, metabolic acidosis, and hypotension are common in calves with neonatal diarrhea. Because calves are more sensitive to fluid loss, hypovolemic shock due to dehydration is a major cause of mortality in neonatal calves [1, 40]. Calves with neonatal diarrhea are hemodynamically stable if they can tolerate their losses [1, 40, 41]. Clinical findings such as loss of sucking reflex, collapse of the eyeball into the orbit, prolonged CRT, decreased skin elasticity, pallor of the mucous membranes, cold extremities, hypothermia, bradycardia due to hyperkalemia, rapid and deep respiration, depression, and watery feces observed in all calves in our study due to dehydration and acidosis are consistent with the previous reports [39, 42–49].

Although the decrease in heart rate after fluid therapy suggests some degree of pre-existing hypovolemia, studies in dogs show that the ability of heart rate to predict fluid response is variable [9]. Contrary to our expectation, the heart rate of the severely dehydrated calves was significantly lower before treatment (P < 0.05) than immediately after treatment. Because heart rate is affected by pain, anxiety, fever, anemia, infection, and acid-base status in the body [9, 50], it has been reported to be an unreliable marker for assessing hypovolemia and fluid response. One study reported that there was no significant change in heart rate immediately after fluid therapy when comparing fluid-responsive and non-responsive cases [51]. When all these data were evaluated, it was found that heart rate was not a reliable marker in assessing the degree of dehydration and response to fluid therapy.

Local or systemic inflammation caused by enteritis in calves with neonatal diarrhea causes changes in some hematologic parameters such as WBC, GRA, HCT, RBC and Hb with hemodynamic status and dehydration [38]. By reducing the negative effect of lipopolysaccharides on tissues, restoring the circulation and microcirculation of calves in the study after treatment and returning all these parameters to reference values are consistent with previous data [38, 52–56].

Metabolic acidosis is commonly observed in sick calves during the neonatal period [57]. In the present study, significant changes were observed in the levels of pH, BE, and HCO3− in all calves after treatment, compared to before treatment (P < 0.05). When group I and group II calves were evaluated, there was no difference (P > 0.05) in pH, BE, and HCO3−, indicating no relationship between the severity of dehydration and metabolic acidosis [58]. In our study, mild and moderate increases in K+ were observed, consistent with previous studies [59–62], and returned to reference ranges as extracellular volume and pH increased with fluid therapy [39]. In addition, hyperlactatemia, which was observed in all calves, decreased with fluid therapy due to improved tissue perfusion and returned to reference ranges [42, 47, 63]. Blood lactate concentration is an indicator of tissue perfusion, as it reflects increased anaerobic cellular metabolism in hypovolemic patients [9]. However, hyperlactatemia can occur independently of fluid volume, often resulting from hypoxia and intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Hyperlactatemia is observed for both L (L-lactate) and D (D-lactate) and is not restricted to L (associated with intrinsic hypoxia) or D (associated with extrinsic hypoxia caused by bacterial infection) [9]. In this study, the absence of a correlation between CVC and CVC-CI with L-lactate levels can be attributed to the complex etiology of hyperlactatemia. This condition is influenced by various factors, such as regional and microvascular circulation disorders, rather than by macrovascular circulation alone [64].

Although SBP < 90 mmHg or MAP < 65 mmHg is defined as hypotension in calves [65, 66], it has been recognized that hypotension is not always seen with fluid loss [9]. In our study, the absence of hypotension in all calves with dehydration can be explained by compensatory mechanisms that increase vascular resistance in response to hypovolemia [9, 67]. A study conducted in humans reported no increase in MAP values despite fluid therapy [68]. Although fluid volume is increased with fluid therapy, factors such as the distribution of this fluid in the body and vascular tone may not have a direct effect on MAP. While fluid infusions can cause vasodilation, the body’s vasoconstrictive mechanisms often do not result in a significant increase in MAP [50, 67, 68]. However, in the presented study, significant increases in SBP, DBP, and MAP values were observed in the calves that received fluid therapy, particularly after the initial fluid bolus treatment.

In healthy humans, IVC-CI ranges from 20 to 50% [69]. In humans, IVC-CI is negatively correlated with volume status and central venous pressure. Although there are limited studies of CVC-CI to assess fluid response in cats and dogs [70–73], no studies were found in calves. In the present study, while CVCmax-CVCmin diameters increased significantly after treatment, CVC-CI values decreased significantly. Contrary to our expectation, the CVC-CI value of calves in the severe dehydration group (group II) was lower than that of calves in the moderate dehydration group (group I). There are several reasons for this, including individual differences in diameter values, differences in respiratory rate and effort of the calves during measurement, increased intra-abdominal pressure [74], CVC-CI being affected by pressure and vascular compliance [75], and the low sensitivity of CVC-CI as an indicator of hypovolemia [27]. According to the ROC analysis results of our study, the CVCmin-CVCmax diameter may reflect the volume status more than the arterial system-based variables such as blood pressure [68]. On the other hand, CVC diameter and CVC-CI were significantly correlated with clinical findings indicating dehydration, complete blood count, blood gas analysis and hemodynamic parameters. The correlation between CVC diameter and CVC-CI with clinical signs of dehydration, complete blood count, blood gas analysis, and hemodynamic parameters indicates that ultrasonographic findings are consistent with parameters associated with hypovolemia in calves with neonatal diarrhea. Moreover, the correlations observed between CVCmax, CVCmin, and CVC-CI with clinical signs and blood pressure parameters can be considered closely associated with the improvement in the overall condition of calves following fluid therapy. Notably, CVCmax and CVCmin diameters provide valuable insights for distinguishing between moderately and severely dehydrated calves.

According to the ROC analysis results obtained in our study, CVCmin-CVCmax diameter measurements were more successful than CVC-CI calculation in predicting the degree of dehydration. Similarly, CVCmin diameter change measurements were relatively more successful than CVCmax diameter change measurements. This may be related to the fact that CVCmin is the minimum CVC diameter during inspiration and the blood in the lumen of the CVC shrinks as much as possible. On the other hand, CVCmax is the maximum CVC diameter, which is expected to be more affected by conditions associated with forced expiration, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or tachypnea [68]. In human medicine, an increase of 0.3 cm in IVC values after fluid therapy may indicate that fluid therapy is adequate [67]. In the present study, there is an increase of 0.74 cm in mean CVCmax diameter immediately after fluid treatment in group I calves compared to the before treatment period, and an increase of 0.71 cm in mean CVCmax diameter immediately after fluid treatment in group II calves compared to the before treatment period. Similarly, an increase of 0.66 cm in mean CVCmin diameter was noted in group I calves after fluid treatment compared to the before treatment period, and an increase of 0.47 cm in mean CVCmin diameter was noted in group II calves after fluid treatment compared to the before treatment period. These data may indicate that the calves in our study received adequate fluid after the first bolus.

In the present study, when the changes in CVCmin, CVCmax, and CVC-CI were analyzed at different time points, the greatest change was observed after the first fluid bolus. We believe that this is due to the decreased sensitivity of prolonged replacement therapy in showing the volume status of diameters, the higher proportion of fluid given initially when the percentage of dehydration is high, the adequacy of fluid therapy, and the fact that at most 30% of the fluid given remains in the intravascular space and moves to the extravascular space over time [68, 76]. However, as fluid infusion continues, more fluid moves to the extravascular space due to less dehydration. In addition, the differences in these values in humans, cats, dogs, and foals may be due to their different anatomical structures and species [2]. It may also be explained by the difference in breathing patterns between calves, which breathe at their own pace, and humans, who are asked to take “deep breaths” or are ventilated [77].

There is no consensus on a standard reference diameter in human and veterinary medicine due to variations in body size in adult and pediatric populations [78–81]. In fact, one study reported that IVC diameter was not significantly affected by individual characteristics [81]. In another study, although it was reported that patient height and thoracic measurements may affect CVC value [82], breed and sex were found to have no effect on CVC measurement in a study conducted in calves [2]. In the present study, we believe that CVC diameter were minimally affected by demographic variables because the age, sex, body weight, thoracic circumference, and withers height of the calves in both groups were similar [83].

The evaluation of the CVC diameter can be challenging in cases with abdominal distension [9]. Therefore, measurements were performed in calves considering the abomasal emptying time (12 h). The time required to obtain optimal imaging and complete measurements was approximately 5 min. This method could represent a promising, non-invasive procedure for monitoring fluid therapy in hospital or field settings, as it was well-tolerated by calves. In our experience, no adverse events were observed during the ultrasound examination. In both human and veterinary medicine, ultrasonographic measurement of the CVC is considered reliable and a simple technique following a brief training session [84].

Our study has some limitations. A major limitation of our study is the absence of measurements of the CVC diameter and CVC-CI in healthy calves with normal hydration. Since calves that received fluid therapy were not included in our study, the CVC diameter and CVC-CI measured before treatment (hour 0) served as an important reference point for the measurements and comparisons made at different time points. In addition, there are many clinical conditions in which CVC-CI cannot be appropriately used to predict fluid responsiveness [74]. These include high inspiratory effort, increased intra-abdominal pressure, right-sided chronic heart failure, and local factors such as thrombosis or mass compression of the CVC [22, 74]. The calves in this study were conscious, and therefore respiratory rate and effort could not be standardized. Echocardiography was not performed in this study, and the presence of undetected early heart disease may have affected the CVC and CVC-CI. Another potential limitation of the study is that the measurements were performed by only one person, which could introduce variability and lead to measurement errors. The transducer pressure can affect the measured CVC diameter [35, 82, 84]. Although care was taken not to apply pressure during image acquisition, inadvertent excessive pressure may have artificially collapsed the CVC. Finally, in other species, changes in abdominal CVC diameter have been evaluated using many sonographic windows, whereas our study evaluated data from only a single sonographic window. Although this is the most commonly described window in human medicine, there may be other windows that would allow better measurement of the CVC. In addition, as mentioned above, animal positioning may have influenced our results. The comparison of multiple windows for obtaining images of the CVC in calves warrants further research in veterinary medicine.

Conclusion

Future studies should focus on determining the normal reference ranges for CVC diameter and CVC-CI in healthy calves with normal hydration. As values are reported for normally hydrated calves, a more objective distinction could be made between non-dehydrated and dehydrated calves. CVCmax, CVCmin, and CVC-CI measurements can provide valuable information for monitoring fluid therapy. Specifically, CVCmax and CVCmin diameters can offer critical insights for distinguishing between moderately and severely dehydrated calves.

Acknowledgements

The manuscript has been produced from thesis of Dr. Alper ERTURK. The authors thank Assoc. Prof. Amir Naseri for his contributions to the statistical analysis of this study.

Abbreviations

- AUC

Area under the curve

- BE

Base excess

- IVC-CI

Inferior vena cava collapsibility index

- CVC-CI

Caudal vena cava collapsibility index

- CI

Confidence interval

- CRT

Capillary refill time

- CVC

Caudal vena cava

- CVCmax

Caudal vena cava maximum diameter with expiration

- CVCmin

Caudal vena cava minimum diameter with inspiration

- DBP

Diastolic blood pressure

- GRA

Granulocytes

- Hb

Hemoglobin

- HCO3−

Bicarbonate

- HCT

Hematocrit

- HES

Hydroxyethyl starch

- IVC

Inferior vena cava

- K+

Potassium

- LYM

Lymphocytes

- MAP

Mean arterial pressure

- MON

Monocytes

- RBC

Red blood cells

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- WBC

Total leukocyte count

Author contributions

A.E and M.S led the research activity; data managed and analyzed, drafted the manuscript and prepared the manuscript for final publication. A.E, and M.S helped during data management (data collection, data entry), and follow up the research activity and preparing the manuscript for publication. A.E, and M.S helped during data analysis, and preparing the manuscript for final publication.

Funding

This study was supported by Selcuk University Scientific Research Project Office with project number 19102032.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during the current study are included in this article. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, AE, upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approved by the Ethics Board of Selcuk University Veterinary Faculty Experimental Animals Production and Research Center (SUVDAMEK) Ethics Board (approval number: 2021/150). Every procedure was carried out in accordance with the relevant laws and standards. The study was conducted in compliance with the ARRIVE standards. The owner(s) of the animal gave their informed consent for us to use them in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sen I, Constable PD. General overview to treatment of strong ion (metabolic) acidosis in neonatal calves with diarrhea. Eurasian J Vet Sci. 2013;29(3):114–20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casalta H, Busoni V, Eppe J. Ultrasonographical assessment of caudal Vena Cava size through different views in healthy calves: a pilot study. Vet Sci. 2022;9(7):308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson M, Davis DP, Coimbra R, Via G, Tavazzi G, Price S, et al. Diagnosis and monitoring of hemorrhagic shock during the initial resuscitation of multiple trauma patients: a review. J Emerg Med. 2003;24(4):413–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Backer D, Scolletta S. Year in review 2010: critical care-cardiology. Crit Care. 2011;15(6):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis H, Jensen T, Johnson A. 2013 AAHA/AAFP fluid therapy guidelines for dogs and cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2013;49(3):149–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalantari K, Chang JN, Ronco C. Assessment of intravascular volume status and volume responsiveness in critically ill patients. Kidney Int. 2013;83(6):1017–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyd JH, Sirounis D, Maizel J. Echocardiography as a guide for fluid management. Crit Care. 2016;20:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monnet X, Marik PE, Teboul JL. Prediction of fluid responsiveness: an update. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boysen SR, Gommeren K. Assessment of volume status and fluid responsiveness in small animals. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8:630643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorelick MH, Shaw KN, Murphy KO. Validity and reliability of clinical signs in the diagnosis of dehydration in children. Pediatrics. 1997;99(5):e6–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansen B, DeFrancesco T. Relationship between hydration estimate and body weight change after fluid therapy in critically ill dogs and cats. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2002;12(4):235–43. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silverstein DC, Hopper K. Small animal critical care medicine. 1rd ed. St Louis: MO: Elsevier;; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGarvey J, Thompson J, Hanna C, Gorelick MH, Shaw KN, Murphy KO, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of clinical signs for assessment of dehydration in endurance athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44(10):716–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Preau S, Bortolotti P, Colling D. Diagnostic accuracy of the inferior Vena Cava collapsibility to predict fluid responsiveness in spontaneously breathing patients with sepsis and acute circulatory failure. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(3):e290–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson BD, Schlader ZJ, Schaake MW. Inferior Vena Cava diameter is an early marker of central hypovolemia during simulated blood loss. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;25(3):341–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi YA, Kwon H, Lee JH. Comparison of sonographic inferior Vena Cava and aorta indexes during fluid administered in children. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(9):1529–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Behnke S, Robel-Tillig E. Index from diameter of inferior Vena Cava and abdominal aorta of newborns-a relevant method for evaluation of hypovolemia. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2020;224(4):199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mercolini F, Di Leo V, Bordin G. Central venous pressure Estimation by ultrasound measurement of inferior Vena Cava and aorta diameters in pediatric critical patients: an observational study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2021;22(1):e1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sänger F, Dorsch R, Hartmann K. Ultrasonographic assessment of the caudal Vena Cava diameter in cats during blood donation. J Feline Med Surg. 2022;24(6):484–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feissel M, Michard F, Faller JP. The respiratory variation in inferior Vena Cava diameter as a guide to fluid therapy. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:1834–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitakule MM, Mayo P. Use of ultrasound to assess fluid responsiveness in the intensive care unit. Open Crit Care Med J. 2010;3(1):33–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Nicolò P, Tavazzi G, Nannoni L. Inferior Vena Cava ultrasonography for volume status evaluation: an intriguing promise never fulfilled. J Clin Med. 2023;12(6):2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kicher BJ, Himelman RB, Schiller NB. Noninvasive Estimation of right atrial pressure with 2-dimensional and doppler echocardiography: a simultaneous catherization and echocardiographic study. Am J Cardiol. 1990;66(4):493–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brennan JM, Ronan A, Goonawardena S. Handcarried ultrasound measurement of the inferior Vena Cava for assesment of intravascular volume status in the outpatient Hemodialysis clinics. Clin J Am Nephrol. 2006;1:749–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagdev A, Merchant RC, Tirado-Gonzales A, et al. Emergency department bedside ultrasonographic measurement of the caval index for noninvasive determination of low central venous pressure. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:290–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monnet X, Julien F, Ait-Hamou N. Lactate and venoarterial carbon dioxide difference/arterial-venous oxygen difference ratio, but not central venous oxygen saturation, predict increase in oxygen consumption in fluid responders. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(6):1412–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bucci M, Rabozzi R, Guglielmini C, et al. Respiratory variation in aortic blood peak velocity and caudal Vena Cava diameter can predict fluid responsiveness in anaesthetised and mechanically ventilated dogs. Vet J. 2017;227:30–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tuplin MC, Romero AE, Boysen SR. Influence of the respiratory cycle on caudal Vena Cava diameter measured by sonography in healthy foals: a pilot study. J Vet Intern Med. 2017;31(5):1556–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith GW. Treatment of calf diarrhea: oral fluid therapy. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2009;25(1):55–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trefz FM, Lorch A, Feist M. Construction and validation of a decision tree for treating metabolic acidosis in calves with neonatal diarrhea. BMC Vet Res. 2012;8(1):1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boccardo A, Biffani S, Belloli A, et al. Risk factors associated with case fatality in 225 diarrhoeic calves: a retrospective study. Vet J. 2017;228:38–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doré V, Foster DM, Ru H, et al. Comparison of oral, intravenous, and subcutaneous fluid therapy for resuscitation of calves with diarrhea. J Dairy Sci. 2019;102(12):11337–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weyman A. Right ventricular inflow tract. In: Weyman A, editor. Principles and practice of echocardiography. USA: Lea and Febiger; 1994. pp. 853–4. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American society of echocardiography and the European association of cardiovascular imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovas Imaging. 2015;16(3):233–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bowra J, Uwagboe V, Goudie A. Interrater agreement between expert and novice in measuring inferior Vena Cava diameter and collapsibility index. Emerg Med Australas. 2015;27(4):295–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nappert G, Lattimer JC. Comparison of abomasal emptying in neonatal calves with a nuclear scintigraphic procedure. Can J Vet Res. 2001;65(1):50–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miyazaki T, Miyazaki M, Yasuda J. Ultrasonographic imaging of abomasal curd in preruminant calves. Vet J. 2009;179(1):109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seifi HA, Mohri M, Shoorei E. Using haematological and serum biochemical findings as prognostic indicators in calf diarrhea. Comp Clin Path. 2006;15(3):143–7. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith GW, Berchtold J. Fluid therapy in calves. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2014;30(2):409–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hartmann H, Finsterbusch L, Lesche R. Fluid balance of calves. II. Fluid volume in relation to age and the influence of diarrhea. Arch Exp Veterinarmed. 1984;38:913–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berchtold J. Treatment of calf diarrhea: intravenous fluid therapy. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2009;25(1):73–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lorenz I, Gentile A, Klee W. Investigations of D-lactate metabolism and the clinical signs of D‐ lactataemia in calves. Vet Rec. 2005;156(13):412–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guzelbektes H, Coskun A, Sen I. Relationship between the degree of dehydration and the balance of acid-based changes in dehydrated calves with diarrhea. Bull Vet Inst Pulawy. 2007;51(1):83–7. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fecteau G, Smith BP, George LW. Septicemia and meningitis in the newborn calf. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2009;25(1):195–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bellino C, Arnaudo F, Biolatti C. Development of a diagnostic diagram for rapid field assessment of acidosis severity in diarrheic calves. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2012;240(3):312–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dawes ME, Tyler JW, Hostetler DE, et al. Clinical examination, diagnostic testing, and treatment options for neonatal calves with diarrhea. Bov Pract. 2014;48:61–75. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heller MC, Chigerwe M. Diagnosis and treatment of infectious enteritis in neonatal and juvenile ruminants. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2018;34(1):101–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coşkun A, Aydoğdu U, Başbuğ O. İshalli Yenidoğan Buzağılarda elektrolit Bozukluklarının Prevalansı. Turk Vet J. 2020;2(2):62–6. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kells NJ, Beausoleil NJ, Johnson CB. Indicators of dehydration in healthy 4-to 5-day-old dairy calves deprived of feed and water for 24 hours. J Dairy Sci. 2020;103(12):11820–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nette RW, Ie EH, Vletter WB. Norepinephrine-induced vasoconstriction results in decreased blood volume in dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplan. 2006;21(5):1305–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Glassford NJ, Eastwood GM, Bellomo R. Physiological changes after fluid bolus therapy in sepsis: a systematic review of the contemporary literature. Crit Care. 2014;18(2):1–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taylor JA. Leukocyte responsees in ruminants. In: Bernart FF, Joseph GZ, Nemi CJ, editors. Schalm’s veterinary hematology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Wiliams and Wilkins; 2000. pp. 391–401. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Uzlu E, Karapehlivan M, Çitil M. İshal semptomu Belirlenen Buzağılarda serum Sialik Asit Ile Bazı Biyokimyasal parametrelerin Araştırılması. Van Vet J. 2010;21(2):83–6. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paydar S, Bazrafkan H, Golestani N. Effects of intravenous fluid therapy on clinical and biochemical parameters of trauma patients. Emerg. 2014;2(2):90–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Öcal N, Yasa Duru S, Yağcı BB. İshalli Buzağılarda asit-baz Dengesi Bozukluklarının Saha Şartlarında Tanı ve Sağaltımı. Kafkas Univ Vet Fak Derg. 2006;12(2):175–83. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Panousis N, Siachos N, Kitkas G. Hematology reference intervals for neonatal Holstein calves. Res Vet Sci. 2018;118:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Constable PD, Stämpfli HR, Navetat H. Use of a quantitative strong ion approach to determine the mechanism for acid-base abnormalities in sick calves with or without diarrhea. J Vet Intern Med. 2005;19(4):581–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grove-White DH. Monitoring and management of acidosis in calf diarrhea. J R Soc Med. 1998;91(4):195–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mokhber Dezfouli MR, Dalir Naghadeh B, Mortaz E. The role of electrolytes in the genesis of cardiac arrhythmias in cattle. J Vet Med. 2000;55(1):63–8. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Constable PD, Grünberg W. Hyperkalemia in diarrheic calves: implications for diagnosis and treatment. Vet J. 2013;195(3):271–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Trefz F, Constable PD, Sauter-Louis C. Hyperkalemia in neonatal diarrheic calves depends on the degree of dehydration and the cause of the metabolic acidosis but does not require the presence of acidemia. J Dairy Sci. 2013;96:7234–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Constable PD, Hinchcliff KW, Done SH. Veterinary medicine: a textbook of the diseases of cattle, horses, sheep, pigs, and goats. 11rd ed. Elsevier: St. Louis MO;; 2017.

- 63.Lorenz I, Gentile A. D-lactic acidosis in neonatal ruminants. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2014;30(2):317–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nguyen HB, Rivers EP, Knoblich BP, et al. Early lactate clearance is associated with improved outcome in severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1637–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Naseri A, Sen I, Turgut K. Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular systolic function in neonatal calves with naturally occurring sepsis or septic shock due to diarrhea. Res Vet Sci. 2019;126:103–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Naseri A, Ider M. Comparison of blood gases, hematological and monitorization parameters and determine prognostic importance of selected variables in hypotensive and non-hypotensive calves with sepsis. Eurasian J Vet Sci. 2021;37(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yanagawa Y, Sakamoto T, Okada Y. Hypovolemic shock evaluated by sonographic measurement of the inferior Vena Cava during resuscitation in trauma patients. J Trauma. 2007;63:1245–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yamanoğlu NGÇ, Yamanoğlu A, Parlak İ. The role of inferior Vena Cava diameter in volume status monitoring; the best sonographic measurement method? Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(3):433–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ferrada P, Anand RJ, Whelan J. Qualitative assessment of the inferior Vena Cava: useful tool for the evaluation of fluid status in critically ill patients. Am Surg. 2012;78:468–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nelson NC, Drost WT, Lerche P, et al. Noninvasive Estimation of central venous pressure in anesthetized dogs by measurement of hepatic venous blood flow velocity and abdominal venous diameter. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2010;51:313–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Meneghini C, Rabozzi R, Franci P. Correlation of the ratio of caudal Vena Cava diameter and aorta diameter with systolic pressure variation in anesthetized dogs. Am J Vet Res. 2016;70:137–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alves FS, Miranda FG, Rezende RZ. Caudal Vena Cava collapsibility index in healthy cats by ultrasonography. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec. 2020;72:1271–6. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Donati PA, Guevara JM, Ardiles V. Caudal Vena Cava collapsibility index as a tool to predict fluid responsiveness in dogs. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2020;30(6):677–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Via G, Tavazzi G, Price S. Ten situations where inferior Vena Cava ultrasound May fail to accurately predict fluid responsiveness: a physiologically based point of view. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(7):1164–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.de Valk S, Olgers TJ, Holman M. The caval index: an adequate non-invasive ultrasound parameter to predict fluid responsiveness in the emergency department? BMC Anesthesiol. 2014;14(1):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tintinalli JE, Krome RL, Ruiz E. Emergency medicine: a comprehensive study guide. Adv Emerg Nurs J. 1992;14(3):74. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Darnis E, Boysen S, Merveille AC, Sartor R, Mamprim MJ, Takahira RK, et al. Establishment of reference values of the caudal Vena Cava by fast-ultrasonography through different views in healthy dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2018;32(4):1308–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Masugata H, Senda S, Okuyama H. Age-related decrease in inferior Vena Cava diameter measured with echocardiography. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2010;222(2):141–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sartor R, Mamprim MJ, Takahira RK. Morphometric evaluation by ultrasonographic exam of the portal Veinm vaudal vein and abdominal aorta in healthy dogs of diferent body weights. Arch Vet Sci. 2010;15(3):143–8. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ng L, Khine H, Taragin BH. Does bedside sonographic measurement of the inferior Vena Cava diameter correlate with central venous pressure in the assessment of intravascular volume in children? Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29(3):337–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gui J, Guo J, Nong F. Impact of individual characteristics on sonographic IVC diameter and the IVC diameter/aorta diameter index. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(11):1602–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Darnis E, Merveille AC, Desquilbet L. Interobserver agreement between non-cardiologist veterinarians and a cardiologist after a 6‐hour training course for echographic evaluation of basic echocardiographic parameters and caudal Vena Cava diameter in 15 healthy Beagles. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2019;29(5):495–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cambournac M, Goy-Thollot I, Violé A. Sonographic assessment of volaemia: development and validation of a new method in dogs. J Small Anim Pract. 2018;59(3):174–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Del Prete C, Freccero F, Lanci A, Gui J, Guo J, Nong F, et al. Transabdominal ultrasonographic measurement of caudal Vena Cava to aorta derived ratios in clinically healthy neonatal foals. Vet Med Sci. 2021;7(5):1451–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during the current study are included in this article. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, AE, upon reasonable request.