Abstract

Background

Despite the 2012 WHO recommendation to add single low dose primaquine (SLDPQ, 0.25 mg/kg body weight) to artemisinin-based combination treatments (ACTs) for blocking the transmission of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum, there are currently no weight-based regimens founded on robust evidence.

Methods

Applying published safety, transmission blocking and pharmacokinetic data, and exploring pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships of age-based dosing of SLDPQ in African children with acute, uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum, we derived weight-based, stand-alone, ACT-, triple ACT-, and vivax-matched regimens by following allometric dosing principles and simulating PQ exposure (area under the concentration time curve). The ACTs were dihydroartemisinin piperaquine (DHAPP), artesunate pyronaridine (ASPYR), artesunate amodiaquine (ASAQ), artesunate mefloquine (ASMQ), artemether lumefantrine (AL), and ALAQ. Tablet strengths were predefined: 2.5, 3.75, 5, 7.5, and 15 mg, and no tablet fractions were allowed. The maximum mg/kg dose was set at 0.5, and, primarily for ease of ACT co-blistering, 1 tablet = 1 dose. We assessed different mg/kg doses and selected the dosing associated with a predicted median exposure closest to 1200 ng*h/mL, the exposure predicted for a 60 kg individual given 15 mg of PQ.

Results

The designed 8 regimens had 4–8 dosing bands. The stand-alone, DHAPP, and ASPYR regimens contain the full line of PQ tablets and all other regimens, except AL (2.5, 7.5, 15 mg) and ALAQ (2.5, 5, 7.5, 15 mg), use 3.75 mg. The 2.5 mg tablet resulted in a maximum dose of 0.56 mg/kg for ASAQ, as this regimen starts at 4.5 kg body weight, whilst all other regimens start at 5 kg and resulted in 0.5 mg/kg. Substituting 3.75 mg with 5 mg results in maximum doses of 0.56 mg/kg (ASAQ, ASMQ) and 0.63 mg/kg (other regimens), risking greater toxicity. Across all dosing bands, 0.17 − 0.56 mg/kg doses predict exposures of ~ 500 − 2000 ng*mL/h. Regimens with more dosing bands had less variations in exposure.

Conclusions

These regimens offer flexibility for malaria control programmes and guidance for drug manufacturers wishing to co-blister SLDPQ with ACTs. The WHO should reinstate the 3.75 mg tablet for prequalification and determine which regimens should be incorporated into their treatment guidelines to advance malaria elimination.

Trial registration

The trial is registered at ISRCTN, number 11594437.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12916-025-04153-4.

Keywords: Primaquine, Transmission blocking, Plasmodium falciparum, Allometric dosing, Haemolysis, Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

Background

In order to counter the threat of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum that was emerging in the Mekong subregion, the WHO recommended in 2012 the addition of single low dose primaquine (SLDPQ, 0.25 mg/kg body weight) to block the transmission of resistant parasites and, if deployed widely, SLDPQ would benefit malaria endemic communities [1]. The optimal dose remains elusive despite a body of research that includes dose ranging studies and weight- and aged-based regimens [2–7].

An aged-based regimen for Africa was proposed in 2018 [8], intending to achieve transmission blocking efficacy with safety in glucose-6-phopshate dehydrogenase deficient (G6PDd) individuals. Based on limited evidence at the time, suggested therapeutic dose ranges were 0.15–0.5 mg PQ base/kg body weight for individuals aged ≥ 6 years and 0.15–0.4 mg PQ base/kg for children aged 1–5 years, given their greater propensity to haemolyse compared to older children and adults when treated for malaria [9]. For children aged 6 months– < 1 year, a cautious 1.25 mg dose was suggested.

Using 2.5, 5, 7.5, and 15 mg tablets, this age-based regimen was tested in > 560 children aged < 12 years in a placebo-controlled trial of 1137 patients that included 284 G6PD deficient boys and girls and 119 heterozygous girls [6]. Reassuringly, SLDPQ had the same tolerability and transfusion rate as placebo (~ 1%), consistent with transfusion rates in other settings of ~ 1–1.5% [10–12]. Moreover, receiving SLDPQ and being G6PD deficient were not independently associated with any deleterious post-treatment effects on the initial absolute and factional fall in haemoglobin (Hb), the nadir Hb concentration, and Hb recovery. Indeed, compared to G6PD normal children, G6PDd children had a more robust reticulocyte response and a higher mean day 42 Hb concentration, especially, in those with low baseline Hb concentrations [13].

PQ disposition was characterised by wide interindividual variation in maximum concentrations (Cmax) and exposures [area under the drug concentration time curve (AUC)] as well as an increased body weight-normalised elimination clearance (Additional file 1: Fig. S1) that peaked at ~ 18 months (median wt 10 kg) and plateaued at 6 years (median wt 17.5 kg) for a median fold difference of 1.6 [14].

For malaria control programmes (MCPs), SLDPQ safety remains troubling despite growing evidence of the very low risk of clinically significant haemolysis [5, 15–20]. In their systematic review of mostly falciparum-infected African patients [15], Stepniewska et al. reported that an increase of 0.1 mg/kg in PQ in 194 G6PDd African individuals (presumed G6PD A− , median age 21 years, IQR 12–30) resulted in a mean Hb decrease of 0.27 (95% CI 0.19–0.34) g/dL; the predicted median Hb falls were -2.9 vs. -1.3 g/dL in 0.75 and 0.25 mg/kg recipients, respectively. This meta-analysis supports the WHO-recommended target dose of 0.25 mg/kg but was hampered by only half of the studies administering PQ on D0 (~ 16%) or D1 (~ 34%), and the number of children < 5 years with G6PDd was small: 28 from Africa and 21 from Asia.

Increasing experience with the 0.75 mg/kg target dose in severe SE Asian G6PD variants in vivax patients remains mostly reassuring [21], despite one transfusion in a G6PDd Cambodian male [22], as well as data from Shekalaghe et al. in asymptomatic Tanzanian children aged ≤ 12 years [23]. A significant minority received > 1 mg/kg [8] but the resulting haemolysis (mean fall 2.5 g/dL) in the G6PDd children was well tolerated.

Gametocyte carriage is a surrogate marker of infectivity and gametocytaemia has a sigmoidal relationship to infectivity; thus, transmission blocking efficacy is best assessed by mosquito infectivity studies [24]. PQ and its predecessor, plasmoquine, rapidly reduce mosquito infectivity, often within 24 h [2, 25–28], with two studies suggesting similar effectiveness of 15, 30, and 45 mg [27, 28]. However, Chotsiri et al. quantified the dose–response relationship [29] in predominantly asymptomatic, older (median age 12 years), G6PD normal, falciparum-infected males [2]. The predicted median times to no infected mosquitoes were ~ 17 (placebo), ~ 2.5 (0.0625 mg/kg), and 1.5 (0.125 mg/kg) days vs. ~ 17 and ~ 10 h for 0.25 and 0.5 mg/kg, respectively. These data show a clinically small difference in efficacy between the two highest doses and support the WHO-recommended, PQ target dose of 0.25 mg/kg.

Hitherto, safety and PK data have been lacking in young, G6PDd African children with acute uncomplicated falciparum malaria, a key target group. Having closed this gap, we embarked on designing SDLPQ regimens, with an emphasis on tolerability, at a time of the rapid spread of artemisinin resistance in eastern Africa [30–34].

Methods

Study details

Full descriptions of study details are explained elsewhere [6, 14]. Briefly, we gave age-based doses of SLDPQ/placebo to Ugandan and Congolese children, aged 6 months–11 years with acute uncomplicated falciparum malaria and a Hb ≥ 6 g/dL. Genotyping characterised G6PD, alpha thalassaemia, sickle cell, and cytochrome (CYP) P450 2D6 metaboliser status (PK substudy, n = 250). The study took place between July 2017 and November 2019 in Mbale, eastern Uganda, and Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and was approved by all pertinent ethics committees. In the 250 patient subset, Mukaka et al. performed a non-compartmental analysis to estimate the pharmacokinetic parameters and then assessed the independent factors affecting those parameters, in particular, primaquine exposure (AUC0-last) [14]. The trial was registered on the 9th of May 2017 at the ISRCTN, number 11594437.

Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationship

Through scatter plots and simple and multivariable linear regressions, we examined the relationships between PQ mg/kg dose, Cmax, and AUC0-last [14] and (i) Hb fractional fall (%): 100 × (nadir Hb − baseline Hb)/baseline Hb, (ii) peak methaemoglobin (metHb) from D1–3, (iii) gametocyte carriage over time, and (iv) the percent reduction in gametocytaemia (gam ct, Eq. 1) as a pharmacodynamic (PD) surrogate marker of transmission blocking efficacy.

| 1 |

Pharmacokinetic model to predict PQ exposure

Following age-dosed PQ, resulting in mg/kg doses of 0.07 to 0.41, 45% (113/250) of the measured AUCs fell between 500 and 1000 ng*h/mL, 27% (n = 70) were > 1000 ng*h/mL, leaving 28% < 500 ng*h/mL (Fig. 1) [14].

Fig. 1.

Measured primaquine exposure as a function of the mg/kg dose administered in G6PD deficient children and a combination of G6PD heterozygous females and normal children

Although these exposures resulted in good safety and a significant reduction in gametocyte carriage vs. placebo [6], we hypothesise that optimal exposures would be achieved by tighter dosing around the 0.25 mg/kg target dose by using weight-based regimens.

Four covariates were independently associated with PQ exposure: mg/kg dose, age, baseline Hb, and the CYP 2D6 activity score (AS) [14], resulting in Eq. 2 below.

| 2 |

This equation predicts that, on average, for every 0.1 mg/kg dose increase, the AUC will increase by 305 ng*h/mL, and by 22 ng*h/mL for every 1-year increase in age whilst increases of 1 g/dL of Hb at presentation and one unit of AS will decrease the AUC by 30 and 166 ng*h/mL, respectively.

This AUC model is validated only for children aged 6 months– < 12 years and the goodness of fit analysis showed a good correlation between observed and predicted AUC0-last values, with no trends in residual plots (Additional file 1: Fig. S2). However, we have gone beyond the model limits and report the AUCs across the weight spectrum from 4.5 to 90 kg and capped the age at 18 years. Accordingly, an 18 years old, 60 kg person dosed with 15 mg of primaquine and with a Hb of 10 g/dL and an AS of 1.5 has a predicted AUC of 1200 ng*h/mL. Given the dose proportional pharmacokinetics of primaquine [35, 36], this predicted AUC is consistent with the calculated median AUC0–24 of 4311 ng*h/mL when 45 mg was given to 7 P. falciparum patients (mean weight 51 kg, mean PQ dose = 0.88 mg/kg) [37], and to the median AUC0–24 of 1090 − 1130 ng*h/mL reported in healthy Thai adults given 30 mg [38–40]. The observed exposure differences between studies suggest a disease effect on PQ disposition and the data from Edwards et al. support our prediction formula as being roughly applicable to adults with falciparum malaria [37].

Dose selection

We prospectively defined several restrictions/parameters. The tablet strengths for testing were 2.5, 3.75, 5, 7.5, and 15 mg. No tablet fractions were allowed, and 1 tablet would equal 1 dose (primarily for ACT co-blistering) but using two PQ tablet strengths was also explored. The stand-alone regimen (i.e. independent of an ACT/triple ACT) used the full line of PQ tablet strengths and includes a 22.5 mg dose for the heavier individuals, resulting in 6 dosing bands. We also explored replacing 3.75 mg with 5 mg in case the 3.75 mg tablet is not available in the future. PQ safety was favoured over PQ transmission blocking efficacy and so 0.5 mg/kg of PQ was set as the maximum dose. However, this was not possible for the ASAQ regimen because it starts at 4.5 kg, resulting in 0.56 mg/kg with the lowest tablet strength.

Dosing was also designed to match commonly used ACTs (4 − 8 dosing bands): (i) artemether lumefantrine (AL, 4 bands), artesunate amodiaquine (ASAQ, 4 bands), artesunate mefloquine (ASMQ, 4 bands), artesunate pyronaridine (ASPYR, 7 bands), dihydroartemisinin piperaquine (DHAPP, 8 bands), (ii) a new triple ACT, ALAQ (5 bands), and (iii) a proposed antirelapse regimen for P. vivax infections (5 bands) [41].

A 700,000+ African anthropometric database [8] was used to define weight-age relationships, selecting the median ages for each 1 kg interval from 5 to 90 kg. In all dose simulations, we assumed a baseline Hb of 10 g/dL, an AS of 1.5, i.e. a normal CYP 2D6 metaboliser (AS = 1.25–2.25 [42]), which was the majority metaboliser status in the PK substudy, 150/250 (60%), and that all weights above 38 kg were associated with an age variable of 18 years. Different doses were evaluated for each body weight by predicting individual exposures from Eq. 2. The dose generating a median exposure in the dosing band closest to 1200 ng*h/mL was deemed the most appropriate dose for that particular weight band.

A higher mg/kg dose is needed in younger children to compensate for their relatively higher clearance/kg and achieve comparable exposures to adults. Therefore, we also estimated the mg/kg dose in children according to the allometric scale equation below (Eq. 3, BW = body weight) [43] and used a target adult dose of 15 mg of PQ in a 60 kg person (0.25 mg/kg). The allometric line was plotted against the proposed mg/kg doses achieved by the selected dosing regimens.

| 3 |

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 1137 malaria-infected children [6], median age of 5 years, were randomised to AL or DHAPP and SLDPQ/placebo; 239 were G6PD-c.202T (A−) hemizygous males, 45 G6PD-c.202T homozygous females, 119 G6PD A− heterozygous females, and 418 and 202 were G6PD-c.202C normal males and females, respectively (17 unknown status). Some 15% had sickle cell trait and more than half had α-thalassaemia: silent carriers (αα/α −), ~ 43%, and trait (α − /α −), ~ 10%. 1129/1137 (99.3%) were of normal nutritional status. The mean baseline Hb concentration was 10.6 g/dL, ~ 7% (76/1137) had a Hb < 8 g/dL, the asexual parasitaemia geometric mean was 14,599 (range 7–2,172,060)/µL, and 18% had baseline gametocytes. The administered PQ dose ranged from 0.07 to 0.41 mg/kg for a median of 0.21 mg/kg. More details are shown in Additional file 1: Table S1.

PKPD haemoglobin relationship

In the G6PDd patients, there was substantial overlap in and very similar correlations for the Hb fractional fall between the SLDPQ and placebo recipients (Fig. 2 and Additional file 1: Fig. S3). In the SLDPQ recipients, there was no relationship between Hb fractional fall and the PQ Cmax and AUC (Additional file 1: Fig. S4).

Fig. 2.

Changes in the fractional fall in haemoglobin as a function of the mg/kg dose of primaquine. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was 0.12 and an increase of 0.1 mg/kg of primaquine predicts a mean decrease in the fractional fall of 1.8 (95% CI: -0.56 to 4.2)%. Results in the placebo group were similar: r = 0.16, 2.2 (-1.07 to 5.5)%

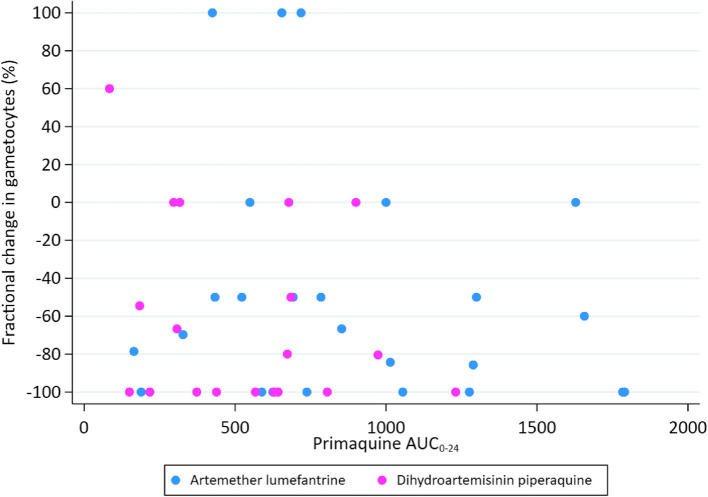

PKPD gametocyte relationships

There was no relationship between the PQ Cmax (data not shown) and AUC (Fig. 3) and the percent reduction in gametocytaemia on D2. However, children receiving a median dose of ≥ 0.21 mg/kg had significantly lower gametocyte carriage by D3 vs. D7, compared to children receiving < 0.21 mg/kg (Additional file 1: Fig. S5).

Fig. 3.

Percent reduction in day 2 gametocytaemia excluding 3 outlying values > 100%, as a function of primaquine exposure [adjusted R2 (aR.2) = -0.0111, p = 0.484, univariate analysis]

PKPD methaemoglobin relationships

The increases in metHb were modest with much overlap between PQ and placebo. There were no independent associations between the maximum D1 − D3 metHb values and (i) age, (ii) being on SLDPQ/placebo (Fig. 4), and (iii) PQ mg/kg dose, Cmax, and AUC (Additional file 1: Fig. S6).

Fig. 4.

Distribution of peak methaemoglobin values (%) by age in the placebo and single low dose primaquine arms (aR.2 = -0.0015, p = 0.419, univariate analysis)

SLDPQ regimens and predicted exposures

The predicted AUCs for the proposed stand-alone, ACT-, triple ACT-, and vivax-matched regimens are shown in Fig. 5. In these regimens, one tablet is equivalent to 1 dose, but in the stand-alone regimen we have used a combination of 7.5 + 15 mg tablets (i.e. 22.5 mg) in the highest weight band. All other regimens, including those with mixed doses of 11.25, 22.5, and 30 mg, are shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S7.

Fig. 5.

The dosing regimens and their predicted primaquine exposures for the stand-alone regimen and matched regimens for dihydroartemisinin piperaquine (DHAPP), artesunate pyronaridine (ASPYR), ALAQ triple, artesunate amodiaquine (ASAQ), artesunate mefloquine (ASMQ), artemether lumefantrine (AL), and Plasmodium vivax. The red line represents the targeted median exposure of 1200 ng*h/mL

The first dosing band of all regimens uses 2.5 mg of PQ, resulting in maximum doses of 0.56 mg/kg for ASAQ (weight 4.5 kg) and 0.5 mg/kg for all the others. These values are similar to the dose suggested by the allometric equation of 0.47 mg/kg for a 5 kg patient (Additional file 1: Fig. S8). The minimum PQ dose in the first weight band is 0.17 mg/kg in the AL regimen, resulting in an AUC of ~ 500 ng*h/mL compared to 750 − 1000 ng*h/mL minimum values for the other regimens. A 90 kg individual would also receive a minimum of 0.17 mg/kg of PQ with 15 mg, resulting in a predicted minimum exposure of ~ 800 ng*h/mL.

Plots of PQ dose (mg/kg) for selected SLDPQ regimens vs. body weight, overlayed with the allometric line, show greater variation for regimens with fewer dosing bands (Additional file 1: Fig. S8).

The peak median clearance/kg occurred at 18 months. At this age, a child has a median weight of 10 kg with a 5th − 95th centile range of 7.4 − 13.6 kg. If given 3.75 mg of PQ, she/he would receive a median (5th − 95th) dose of 0.375 (0.28 − 0.51) mg/kg, which becomes 0.5 (0.37 − 0.68) mg/kg with a 5 mg tablet. These median mg/kg doses compare to 0.39 mg/kg predicted by the allometric equation. If dosed more tightly by weight, e.g. 8 − 10.9 kg, the resulting mg/kg ranges are 0.34 − 0.47 and 0.46 − 0.63, respectively. Exposures and mg/kg doses for the 3.75 and 5 mg tablets are illustrated in Additional file 1: Figs. S7 and S8.

Discussion

We have designed SLDPQ regimens for malaria elimination to cover currently used ACTs, a new triple ACT, and, for MCPs who prefer a more straight forward approach, a stand-alone regimen for universal use, and one matched to a proposed vivax regimen for vivax endemic countries.

To derive our regimens, we followed the WHO-recommended target dose of 0.25 mg/kg (15 mg in a 60 kg adult, translating to an AUC of ~ 1200 ng*h/mL [14]), took into account published and newly generated PK data, favouring safety over efficacy, and predefined the tablet strengths with the option of mixing tablets but not using tablet fractions. Although our model was robust and showed a good correlation between observed and predicted AUCs, we extrapolated beyond the data to simulate AUCs outside of the age/weight limits of our patients to make dose recommendations. These AUCs should be considered rough estimates and be interpreted with some caution. Clearly, we need more PQ PK studies in the under-1s, older children, and adults to develop better models. Designing optimal PQ regimens is hampered by the inability to measure the oxidative metabolites that underlie PQ’s mechanisms of action regarding transmitting blocking efficacy and haemolytic toxicity [44, 45]. Thus, dose–response relationships have to be approximated using PQ PK, cognisant that PQ is prodrug that is subject to metabolic polymorphism by CYP 2D6 [45].

MCPs worry about the potential haemolytic toxicity of SLDPQ and this explains partly its limited deployment. Extensive analysis by our group in acutely sick, African children with falciparum malaria [6, 13] has helped establish SLDPQ safety and complements the evidence in Stepniewska et al.’s meta-analysis [15]. With the relatively narrow dose range of 0.07–0.41 mg/kg (IQR 0.17–0.25), there was essentially no relationship between PQ dose and exposure and Hb fractional fall and peak metHb. This is consistent with a small study of healthy G6PDd and normal Malian adults, given higher doses of 0.4, 0.45, and 0.5 mg/kg in whom Hb declines (fractional falls mostly ≤ 10%) and modest metHb increases were unrelated to PQ Cmax and AUC0-last [46]. By contrast, Stepniewska et al. predict an upper 95% CI Hb decrease of 0.34 g/dL/0.1 mg/kg PQ dose increase and a median fall of ~ 3 g/dL for 0.75 mg/kg. These data, data of PQ as mass drug administration [16, 23], and historical data when 0.75 mg/kg was used for transmission blocking [47], all suggest strongly SLDPQ safety across a spectrum of G6PD variants at the 0.25 mg/kg target dose [5, 48].

Most of the proposed regimens use 3.75 mg, resulting in less variability in the younger children and adequate PQ exposures with minimum, predicted AUCs of ~ 600 in ACT regimens (ASAQ and ASMQ), ~ 750 (vivax-matched regimen), and ~ 800–1000 ng*h/mL for the other 3 regimens. The WHO withdrew this tablet strength from prequalification some years back for reasons that remain unclear but they now have the opportunity to reconsider this decision. Moreover, using 5 mg instead of 3.75 mg significantly increases the maximum doses to ~ 0.6 mg/kg and exposures to ~ 2000 ng*h/mL that will likely increase the risk of, particularly, abdominal pain and early vomiting. Background rates of early vomiting in ACT-treated, young children (6–24 months) are ~ 7% for AL and 15% for DHAPP [49], and ~ 2% for AL, ~ 4.5% for ASAQ, and 9% for DHAPP in under-5 children [11]. The lack of a 3.75 mg tablet would also limit options for co-blistering SLDPQ with several ACTs for young children.

All regimens use a 2.5 mg tablet for the first dosing band because this is the lowest, WHO-mandated PQ tablet strength, resulting in maximum mg/kg doses of 0.5 (0.56 for ASAQ) and predicted exposures of ~ 1750 (~ 1900 ASAQ) ng*h/mL. Data on PQ at any dose in very young children who are treated with ACTs are very limited so collecting tolerability data, notably gastrointestinal upset and early vomiting requiring redosing, will be crucial. Our group is in the early stages of developing PQ granules, which are ideally suited for young children. They offer far greater dosing flexibility than fixed dosed tablets and can be given without water, and could, e.g. be dosed at 2 mg in the first weight band to minimise toxicity. Much more development work needs to be done before granules can be registered or, if requested, prequalified by the WHO.

With concrete dosing options for SLDPQ, the question now is where do we go from here? For co-blistering with ACTs, cost and manufacturing practicalities demand that only one PQ tablet is co-blistered but the stand-alone regimen offers the possibility of mixing tablet strengths. The WHO should consider reinstating the 3.75 mg tablet not just for transmission blocking but also for under-1 children with P. vivax, if they tolerate poorly the 5 mg dose [41]. Moreover, this would avoid the inconvenience of splitting a 7.5 mg tablet. In considering their next move, many MCPs will to look to the WHO for guidance. The WHO should seize the opportunity to examine the merits of these SLDPQ regimens and incorporate them into the WHO Malaria Guidelines.

Faced with the rapid expansion of de novo artemisinin-resistant P. falciparum across eastern Africa [30–34], the WHO needs to act quickly and be bolder in recommending SLDPQ as part of a comprehensive strategy to counter this threat, which, over time, is likely to bring increasing misery, morbidity, and mortality [50, 51]. We cannot wait years for the results of large, cluster-randomised trials to prove that a given strategy impedes the development or spread of artemisinin resistance.

Conclusions

Some 12 years after the WHO recommended using SLDPQ, we present the first evidenced-based regimens of SLDPQ, offering flexible options for malaria elimination. The proposed doses should be well tolerated across the G6PDd severity spectrum and, with 1 tablet = 1 dose, easily co-blistered and administered. The case for 3.75 mg is compelling and the WHO needs to consider with some urgency reinstating it. More research is needed on PQ granules as a future option for small children.

Time is pressing to counter artemisinin resistance and deployment of SLDPQ needs to be accelerated with the full backing of the WHO.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1 Body weight-normalised clearance of primaquine (14). Fig. S2 Goodness of fit plots for the AUC prediction equation. Fig. S3 The distributions of the nadir haemoglobin (A) and fractional change in haemoglobin (B) from baseline to day of nadir haemoglobin within 14 days in children who received single low dose primaquine or placebo. Fig. S4 Scatter plots of the nadir haemoglobin and fractional change in haemoglobin vs. the maximum primaquine concentration in ng/mL (panels A and B) and primaquine exposure in ng*h/mL (panels C and D). Fig. S5 Gametocyte carriage over time as a function of the mg/kg dose of primaquine. Panel A shows children who received < 0.21 mg/kg and B those received ≥ 0.21 mg/kg. Fig. S6 Scatterplots of the maximum methaemoglobin from days 1 to 3 and the mg/kg dose of primaquine (A), the primaquine Cmax in ng/mL (B), and primaquine exposure in ng*h/mL (C). Fig. S7 Predicted AUCs for single low dose primaquine in ACT-matched and stand-alone regimens. Fig. S8 SLDPQ mg/kg doses of SLDPQ regimens vs. an allometric line. The allometric line formula is adapted from Holford and Anderson (43): primaquine dose = 15 mg × (body weight in kg/60)0.75. Table S1 Baseline characteristics of falciparum-infected Ugandan and Congolese children in the safety trail of single low dose primaquine (6). Table S2 Modelled weight for age Table (8). Table S3 Modelled age for weight Table (8).

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their guardians for participating in the study and the laboratory technicians, nurses, and data managers from both sites as well as MORU’s CTSG for making the study happen. MM, WRT & JT are supported by the Wellcome Trust of Great Britain through its core grant (220211) to the Mahidol-Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit research programme. For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission. TNW is funded through a Senior Research Fellowship from Wellcome (202800/Z/16/Z). KM and POO received funding from Wellcome East African Overseas Programme Award from the Wellcome Trust 203077/Z/16/Z. JNP is supported by the EDCTP2 grant “Developing Paediatric Primaquine”, reference RIA2019PD-2893.

Abbreviations

- ACT

Artemisinin-based combination therapy

- AL

Artemether-lumefantrine

- AQ

Amodiaquine

- AS

Artesunate or activity score

- AUC0-t

Area under the drug concentration time curve from 0 to the last PK sample

- BW

Body weight

- CI

Confidence interval

- Cmax

Maximum concentration

- CYP

Cytochrome

- D

Day

- DHAPP

Dihydroartemisinin piperaquine

- DPP-IMPRIMA

Developing Paediatric Primaquine-Implementing Single Low Dose Primaquine in Africa

- IQR

Interquartile range

- G6PDd

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

- Hb

Haemoglobin

- L

Lumefantrine

- MCPs

Malaria control programmes

- MQ

Mefloquine

- PD

Pharmacodynamic

- PK

Pharmacokinetics

- PQ

Primaquine

- PYR

Pyronaridine

- SLDPQ

Single low dose primaquine

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

WRJT conceived the original study and co-wrote the grant with NJPD. Site PIs were PO-O (Mbale) and MAO (KIMORU). WRJT & MM conceived the design and analysis for this dosing paper. WRJT, MM, NC, & CT analysed the data and co-wrote the first draft of the paper. JNNP, TNW, KM, NJW & JT critically reviewed the paper. All authors have seen and approved the final submitted version and agreed to publication.

Funding

This work was cofunded by the UK Medical Research Council, Wellcome, and UK Aid through the Global Health Trials (grant reference MR/P006973/1). The funders had no role in the study design, execution, and analysis and decisions regarding publication. UK Medical Research Council, Wellcome Trust, and UK Aid through the Global Health Trials, MR/P006973/1.

Data availability

We have provided much detailed analysis in this paper. Nevertheless, deidentified individual participant data and relevant supplementary data and documents (e.g., data dictionary, protocol, and participant information sheet) will be available to applicants who provide a sound proposal to the Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit Data Access Committee (datasharing@tropmedres.ac). A data access agreement will be put in place before sharing.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

These were obtained from the following: Ministry of Higher and University Education, the University of Kinshasa Public Health School Ethics Committee, and the city of Kinshasa Provincial Government Health Minister (135/MIN.SAN.AFFSOC and ACHUM/CM/JD/2017), Mbale Regional Hospital Institutional Review Committee (MRRH-REC OUT – COM 006/2017), National Drug Authority (CTA0028), and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (HS2205), and Oxford University Tropical Research Ethics Committee (reference 53–16). All parents/guardians gave fully informed consent to join the study and for the data to be published.

Consent for publication

This was obtained from parents/guardians at the signing of the consent form.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.White NJ, Qiao LG, Qi G, Luzzatto L. Rationale for recommending a lower dose of primaquine as a Plasmodium falciparum gametocytocide in populations where G6PD deficiency is common. Malar J. 2012;11:418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dicko A, Brown JM, Diawara H, Baber I, Mahamar A, Soumare HM, et al. Primaquine to reduce transmission of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Mali: a single-blind, dose-ranging, adaptive randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(6):674–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goncalves BP, Pett H, Tiono AB, Murry D, Sirima SB, Niemi M, et al. Age, weight, and CYP2D6 genotype are major determinants of primaquine pharmacokinetics in African children. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy (Medline). 2017;61(5):e02590–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Eziefula AC, Bousema T, Yeung S, Kamya M, Owaraganise A, Gabagaya G, et al. Single dose primaquine for clearance of Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes in children with uncomplicated malaria in Uganda: a randomised, controlled, double-blind, dose-ranging trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(2):130–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dysoley L, Kim S, Lopes S, Khim N, Bjorges S, Top S, et al. The tolerability of single low dose primaquine in glucose-6-phosphate deficient and normal falciparum-infected Cambodians. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor WR, Olupot-Olupot P, Onyamboko MA, Peerawaranun P, Weere W, Namayanja C, et al. Safety of age-dosed, single low-dose primaquine in children with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency who are infected with Plasmodium falciparum in Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023;23(4):471–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mosha D, Kakolwa MA, Mahende MK, Masanja H, Abdulla S, Drakeley C, et al. Safety monitoring experience of single-low dose primaquine co-administered with artemether-lumefantrine among providers and patients in routine healthcare practice: a qualitative study in Eastern Tanzania. Malar J. 2021;20(1):392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor WR, Naw HK, Maitland K, Williams TN, Kapulu M, D’Alessandro U, et al. Single low-dose primaquine for blocking transmission of Plasmodium falciparum malaria - a proposed model-derived age-based regimen for sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zwang J, D’Alessandro U, Ndiaye JL, Djimde AA, Dorsey G, Martensson AA, et al. Haemoglobin changes and risk of anaemia following treatment for uncomplicated falciparum malaria in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Price RN, Simpson JA, Nosten F, Luxemburger C, Hkirjaroen L, ter Kuile F, et al. Factors contributing to anemia after uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;65(5):614–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Onyamboko MA, Fanello CI, Wongsaen K, Tarning J, Cheah PY, Tshefu KA, et al. Randomized comparison of the efficacies and tolerabilities of three artemisinin-based combination treatments for children with acute Plasmodium falciparum malaria in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(9):5528–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fanello CI, Karema C, Avellino P, Bancone G, Uwimana A, Lee SJ, et al. High risk of severe anaemia after chlorproguanil-dapsone+artesunate antimalarial treatment in patients with G6PD (A-) deficiency. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(12): e4031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onyamboko MA, Olupot-Olupot P, Were W, Namayanja C, Onyas P, Titin H, et al. Factors affecting haemoglobin dynamics in African children with acute uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria treated with single low-dose primaquine or placebo. BMC Med. 2023;21(1):397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mukaka M, Onyamboko MA, Olupot-Olupot P, Peerawaranun P, Suwannasin K, Pagornrat W, et al. Pharmacokinetics of single low dose primaquine in Ugandan and Congolese children with falciparum malaria. EBioMedicine. 2023;96: 104805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stepniewska K, Allen EN, Humphreys GS, Poirot E, Craig E, Kennon K, et al. Safety of single-dose primaquine as a Plasmodium falciparum gametocytocide: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bancone G, Chowwiwat N, Somsakchaicharoen R, Poodpanya L, Moo PK, Gornsawun G, et al. Single low dose primaquine (0.25 mg/kg) does not cause clinically significant haemolysis in G6PD deficient subjects. PloS one. 2016;11(3):e0151898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mwaiswelo R, Ngasala BE, Jovel I, Gosling R, Premji Z, Poirot E, et al. Safety of a single low-dose of primaquine in addition to standard artemether-lumefantrine regimen for treatment of acute uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Tanzania. Malar J. 2016;15:316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen I, Diawara H, Mahamar A, Sanogo K, Keita S, Kone D, et al. Safety of single-dose primaquine in G6PD-deficient and G6PD-normal males in Mali without malaria: an open-label, phase 1, dose-adjustment trial. J Infect Dis. 2018;217(8):1298–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tine RC, Sylla K, Faye BT, Poirot E, Fall FB, Sow D, et al. Safety and efficacy of adding a single low dose of primaquine to the treatment of adult patients with Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Senegal, to reduce gametocyte carriage: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2017;65(4):535–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bastiaens GJH, Tiono AB, Okebe J, Pett HE, Coulibaly SA, Goncalves BP, et al. Safety of single low-dose primaquine in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficient falciparum-infected African males: two open-label, randomized, safety trials. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(1): e0190272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor WRJ, Meagher N, Ley B, Thriemer K, Bancone G, Satyagraha A, et al. Weekly primaquine for radical cure of patients with Plasmodium vivax malaria and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023;17(9): e0011522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kheng S, Muth S, Taylor WR, Tops N, Kosal K, Sothea K, et al. Tolerability and safety of weekly primaquine against relapse of Plasmodium vivax in Cambodians with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. BMC Med. 2015;13:203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shekalaghe SA, ter Braak R, Daou M, Kavishe R, van den Bijllaardt W, van den Bosch S, et al. In Tanzania, hemolysis after a single dose of primaquine coadministered with an artemisinin is not restricted to glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase-deficient (G6PD A-) individuals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(5):1762–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White NJ. Primaquine to prevent transmission of falciparum malaria. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(2):175–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mackerras MJ, Ercole QN. Observations on the action of quinine, atebrin and plasmoquine on the gametocytes of Plasmodium falciparum. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1949;42(5):455–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dick GW, Bowles RV. The value of plasmoquine as a gametocide in sub-tertian malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1947;40(4):447–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rieckmann KH, McNamara JV, Kass L, Powell RD. Gametocytocidal and sporontocidal effects of primaquine upon two strains of Plasmodium falciparum. Mil Med. 1969;134(10):802–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burgess RW, Bray RS. The effect of a single dose of primaquine on the gametocytes, gametogony and sporogony of Laverania falciparum. Bull World Health Organ. 1961;24:451–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chotsiri P, Mahamar A, Hoglund RM, Koita F, Sanogo K, Diawara H, et al. Mechanistic modeling of primaquine pharmacokinetics, gametocytocidal activity, and mosquito infectivity. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2022;111(3):676–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mihreteab S, Platon L, Berhane A, Stokes BH, Warsame M, Campagne P, et al. Increasing prevalence of artemisinin-resistant HRP2-negative malaria in Eritrea. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(13):1191–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uwimana A, Legrand E, Stokes BH, Ndikumana JM, Warsame M, Umulisa N, et al. Emergence and clonal expansion of in vitro artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum kelch13 R561H mutant parasites in Rwanda. Nat Med. 2020;26(10):1602–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uwimana A, Umulisa N, Venkatesan M, Svigel SS, Zhou Z, Munyaneza T, et al. Association of Plasmodium falciparum kelch13 R561H genotypes with delayed parasite clearance in Rwanda: an open-label, single-arm, multicentre, therapeutic efficacy study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(8):1120–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balikagala B, Fukuda N, Ikeda M, Katuro OT, Tachibana SI, Yamauchi M, et al. Evidence of artemisinin-resistant malaria in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(13):1163–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bwire GM, Ngasala B, Mikomangwa WP, Kilonzi M, Kamuhabwa AAR. Detection of mutations associated with artemisinin resistance at k13-propeller gene and a near complete return of chloroquine susceptible falciparum malaria in southeast of Tanzania. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mihaly GW, Ward SA, Edwards G, Nicholl DD, Orme ML, Breckenridge AM. Pharmacokinetics of primaquine in man. I. Studies of the absolute bioavailability and effects of dose size. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1985;19(6):745–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daher A, Pinto DP, da Fonseca LB, Pereira HM, da Silva DMD, da Silva L, et al. Pharmacokinetics of chloroquine and primaquine in healthy volunteers. Malar J. 2022;21(1):16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edwards G, McGrath CS, Ward SA, Supanaranond W, Pukrittayakamee S, Davis TM, et al. Interactions among primaquine, malaria infection and other antimalarials in Thai subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1993;35(2):193–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jittamala P, Pukrittayakamee S, Ashley EA, Nosten F, Hanboonkunupakarn B, Lee SJ, et al. Pharmacokinetic interactions between primaquine and pyronaridine-artesunate in healthy adult Thai subjects. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(1):505–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pukrittayakamee S, Tarning J, Jittamala P, Charunwatthana P, Lawpoolsri S, Lee SJ, et al. Pharmacokinetic interactions between primaquine and chloroquine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(6):3354–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanboonkunupakarn B, Ashley EA, Jittamala P, Tarning J, Pukrittayakamee S, Hanpithakpong W, et al. Open-label crossover study of primaquine and dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine pharmacokinetics in healthy adult Thai subjects. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(12):7340–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor WR, Hoglund RM, Peerawaranun P, Nguyen TN, Hien TT, Tarantola A, et al. Development of weight and age-based dosing of daily primaquine for radical cure of vivax malaria. Malar J. 2021;20(1):366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caudle KE, Sangkuhl K, Whirl-Carrillo M, Swen JJ, Haidar CE, Klein TE, et al. Standardizing CYP2D6 genotype to phenotype translation: consensus recommendations from the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium and Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group. Clin Transl Sci. 2020;13(1):116–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holford NHG, Anderson BJ. Allometric size: the scientific theory and extension to normal fat mass. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2017;109S:S59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Camarda G, Jirawatcharadech P, Priestley RS, Saif A, March S, Wong MHL, et al. Antimalarial activity of primaquine operates via a two-step biochemical relay. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marcsisin SR, Reichard G, Pybus BS. Primaquine pharmacology in the context of CYP 2D6 pharmacogenomics: current state of the art. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;161:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chotsiri P, Mahamar A, Diawara H, Fasinu PS, Diarra K, Sanogo K, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of primaquine and its metabolites in African males. Malar J. 2024;23(1):159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nosten F, Imvithaya S, Vincenti M, Delmas G, Lebihan G, Hausler B, et al. Malaria on the Thai-Burmese border: treatment of 5192 patients with mefloquine-sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine. Bull World Health Organ. 1987;65(6):891–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ashley EA, Recht J, White NJ. Primaquine: the risks and the benefits. Malar J. 2014;13:418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Creek D, Bigira V, Arinaitwe E, Wanzira H, Kakuru A, Tappero J, et al. Increased risk of early vomiting among infants and young children treated with dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine compared with artemether-lumefantrine for uncomplicated malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83(4):873–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trape JF, Pison G, Preziosi MP, Enel C, Desgrees du Lou A, Delaunay V, et al. Impact of chloroquine resistance on malaria mortality. C R Acad Sci III. 1998;321(8):689–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dhorda M, Kaneko A, Komatsu R, Kc A, Mshamu S, Gesase S, et al. Artemisinin-resistant malaria in Africa demands urgent action. Science. 2024;385(6706):252–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Fig. S1 Body weight-normalised clearance of primaquine (14). Fig. S2 Goodness of fit plots for the AUC prediction equation. Fig. S3 The distributions of the nadir haemoglobin (A) and fractional change in haemoglobin (B) from baseline to day of nadir haemoglobin within 14 days in children who received single low dose primaquine or placebo. Fig. S4 Scatter plots of the nadir haemoglobin and fractional change in haemoglobin vs. the maximum primaquine concentration in ng/mL (panels A and B) and primaquine exposure in ng*h/mL (panels C and D). Fig. S5 Gametocyte carriage over time as a function of the mg/kg dose of primaquine. Panel A shows children who received < 0.21 mg/kg and B those received ≥ 0.21 mg/kg. Fig. S6 Scatterplots of the maximum methaemoglobin from days 1 to 3 and the mg/kg dose of primaquine (A), the primaquine Cmax in ng/mL (B), and primaquine exposure in ng*h/mL (C). Fig. S7 Predicted AUCs for single low dose primaquine in ACT-matched and stand-alone regimens. Fig. S8 SLDPQ mg/kg doses of SLDPQ regimens vs. an allometric line. The allometric line formula is adapted from Holford and Anderson (43): primaquine dose = 15 mg × (body weight in kg/60)0.75. Table S1 Baseline characteristics of falciparum-infected Ugandan and Congolese children in the safety trail of single low dose primaquine (6). Table S2 Modelled weight for age Table (8). Table S3 Modelled age for weight Table (8).

Data Availability Statement

We have provided much detailed analysis in this paper. Nevertheless, deidentified individual participant data and relevant supplementary data and documents (e.g., data dictionary, protocol, and participant information sheet) will be available to applicants who provide a sound proposal to the Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit Data Access Committee (datasharing@tropmedres.ac). A data access agreement will be put in place before sharing.