Abstract

Background

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is a primary contributor to end-stage renal disease, yet the underlying molecular mechanisms remain incompletely understood. This study aims to elucidate the role of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and RBP-alternative splicing (AS) regulatory networks in the pathogenesis of DN.

Methods

Two RNA-seq datasets (GSE117085 and GSE142025) were retrieved from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database. Regulated alternative splicing events (RASEs) and genes (RASGs) of RASEs, along with differentiated RBPs, were identified. Validated differentiated RBPs were correlated with clinical features using the Nephroseq v5 online platform. Using the DN mouse model and RT-qPCR, validated the alternative splicing of RNA.

Results

Our analysis revealed 15 differentiated RBP genes and 423 RASEs in the kidney cortex of DN rats compared to controls. Enrichment analysis highlighted lipid metabolism pathways for RASGs. Seven of the identified RBPs were validated in kidney biopsy samples from DN patients versus controls. A co-deregulatory network was constructed based on dysregulated RBPs and RASEs, with select RASGs identified. In vivo experiments, compared to normal mice, the mRNA levels of RPS19 were significantly elevated in the renal tissues of DN mice, while the levels of CPEB4 and CRYZ were markedly decreased.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides evidence implicating dysregulated RBPs and RBP-AS regulatory networks in the development of diabetic nephropathy. The validated RBPs exhibited close associations with clinical biomarkers, reinforcing their potential as therapeutic targets for DN. These findings enhance our understanding of the molecular basis of DN and offer new insights for future research and intervention strategies.

Clinical trial

Not applicable.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12882-025-04237-6.

Keywords: Diabetic nephropathy, Transcriptome, Alternative splicing, RNA binding protein, Co-expression

Introduction

Diabetic nephropathy (DN), one of the diabetes microvascular complications, is the major contributor to end-stage renal disease (ESRD). DN is clinically characterized by albuminuria and/or impaired glomerular filtration [1, 2]. The current treatment of DN is limited to controlling blood pressure and glucose and alleviating high glomerular filtration by the renin-angiotensin system and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, while kidney dialysis and translation are required for advanced cases [3, 4]. However, the molecular mechanisms leading to DN are still not fully understood. Previous studies have suggested that the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy involves a multifactorial interaction between metabolic and hemodynamic factors. DN mainly presents with the thickening of the glomerular basement membrane, expansion of the glomerular mesangial matrix, and Kimmelstiel-Wilson nodule [5]. Moreover, it was reported that structural abnormalities of DN result often result from altered kidney extracellular and intracellular molecule pathways, which are attributed to chronic metabolic and hemodynamic changes induced by prolonged hyperglycemia [6].

Alternative splicing (AS) is a process that enables a messenger RNA (mRNA) to be edited into different isoforms by rearranging the pattern of intron and exon elements. It is estimated that around 95% of human multi-exon genes generate several different transcripts by AS, and the AS process is important for various biological activities and tissue specificity [7]. The disruption of AS has been noted in various diseases, including cancer, diabetes, and vitiligo [8–10]. There is evidence that DN is associated with a transition of expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) A splice isoform. In late DN, the glomerulus expresses more VEGF-A165a mRNA than VEGF-A165b mRNA, while in the early stages, the VEGF-A165b mRNA isoform is more expressed [11].

AS is mainly regulated by trans-acting RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and cis-acting regulatory sequences [12]. RBPs, critical effectors of gene expression, can promote exon inclusion or skip through their interaction with splicing regulatory elements. Consequently, changes in the levels and activity of RBPs can lead to AS dysregulation [13–15]. In this study, we investigated the involvement of dysregulated RBPs and AS regulatory networks in DN, which may provide new indications for studying the pathogenesis of DN.

Materials and methods

The obtainment of public data

The data on gene expression for GSE117085 and GSE142025 [16] were retrieved from the SRA datasets (https://catalog.data.gov/dataset/sequence-read-archive-sra). These datasets consisted of tissue samples obtained from the kidney. GSE117085 comprised six DN rat samples and six control samples. The GSE142025 dataset comprised twenty kidney biopsy samples from advanced DN patients and nine control samples from unaffected areas of tumor nephrectomies.

The conversion of SRA files to fastq format was carried out by the fastq-dump tool from NCBI SRA. The FASTX Toolkit (v.0.0.13; http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/) was then utilized to eliminate low-quality sequences from the original data. The evaluation of clean reads was conducted through FastQC software.

The selection of differentially expressed genes (DEGs)

The TopHat2 tool was utilized to align clean reads to the human GRch38 genome with the allowance of 4 mismatches [17]. By analyzing uniquely mapped reads, the read count and reads per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped (RPKM) values were estimated for each gene. RPKM values were then employed to determine the level of gene expression. Based on both the log2fold change (≥ 1.5 or ≤ 0.75) and P ≤ 0.05, DEGs were identified by DESeq2 [18].

The search of alternative splicing

Alternative splicing events (ASEs) were recognized and measured by the ABLas pipeline [19, 20]. To begin, ABLas identified ten exclusive forms of ASEs using splicing junction reads, including alternative 5’ splice site (A5SS), exon skipping (ES), alternative 3’splice site (A3SS), A3SS&ES, intron retention (IR), A5SS&ES, mutually exclusive exons (MXE), cassette exon, mutually exclusive 3’UTRs (3pMXE), and mutually exclusive 5’UTRs (5pMXE). The regulated ASE (RASE) ratio was calculated—an expression used to represent the changing ratio of constitutively spliced and alternatively spliced reads from two samples. The criteria for detecting RASEs were set to be RASE ratio ≥ 0.2 and P < 0.05. The t-test was employed to ascertain the statistical significance of RASE ratio for repeated comparisons.

The construction of the RBP and RASE networks

A correlation analysis was conducted to explore the relationship between the RASE PSI value and differential RBP expression. Certain RASEs and RBPs that have correlation coefficients > 0.7 and P < 0.01 were considered relevant and used to construct networks. The Gene Ontology (GO) Biological Process with the greatest enrichment of the top 10 was chosen and depicted in the network diagram. The network diagram was generated with Cytoscape software.

Functional enrichment analysis

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways and GO terms were identified using the KOBAS 2.0 server [21]. The following were the screening standards for the GO enrichment analysis: a minimum of five input genes for every pathway; a corrected P-value (FDR) < 0.05. For KEGG enrichment analysis and screening, a corrected P value (FDR) < 0.05 was necessary for labeling. The hypergeometric test and the Benjamini-Hochberg FDR controlling technique were applied to determine the increased significance of each term. Furthermore, the Reactome (http://reactome.org) dataset was employed to find the enrichment of certain gene sets.

Other statistical analyses

The clustering of two samples was demonstrated using principal component analysis (PCA) performed with the Factoextra R Package (https://cloud.r-project.org/package=factoextra). The RNA-seq data and genomic annotations were shown using an internal script called Sogen, following normalization of the reads for each gene in the samples utilizing TPM (Tags Per Million). The Pheatmap R Package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pheatmap/index.html) was used to perform the hierarchical clustering according to Euclidean distance. In the Nephroseq v5 web platform (http://v5.nephroseq.org), the relationship between RBP genes and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and urine albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR) was explored with Pearson correlation.

In vivo experimental verification

SPF-grade C57BL/6 mice, purchased from the Hubei Province Experimental Animal Research Center, were used in this study, which received the ethical approval of Hubei Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Laboratory Animal Management and Use Committee (Ethical approval number: Safety Assessment Center (Fu) No. 202410271). The experiment consisted of two groups, each containing five mice. The control group (Con) was fed a standard diet. The DN group was fed a high-sugar, high-fat diet for four weeks, during which the mice exhibited significant weight gain. Subsequently, the DN group received intraperitoneal injections of streptozotocin (STZ, Aladdin, China) at a low dose (40 mg/kg, with a working concentration of 10 mg/ml) for five consecutive days. Blood glucose levels were measured at 4-, 8-, and 12-weeks post-injection. A fasting blood glucose level of ≥ 11.2 mmol/L confirmed the successful establishment of the DN mouse model. All mice were deeply anesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of 2.5% tribromoethanol (Tigergene, China) at a dose of 0.2 mL/10 g body weight and then killed by cervical dislocation to obtain the kidney tissues. Kidney tissues were collected and homogenized in Trizol for RNA extraction. The extracted RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the HiScript II Select qRT SuperMix II (VAZYME). Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) was subsequently performed using the AceQ qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (VAZYME) with specific primer sequences (Table 1). Data analysis was conducted using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Comparisons between two groups were made using Student’s t-test, statistical significance was defined as a P-value < 0.05.

Table 1.

Primer sequence

| Name | Primer | Sequence | Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mus b-actin | Forward | CACGATGGAGGGGCCGGACTCATC | 240 bp |

| Reverse | TAAAGACCTCTATGCCAACACAGT | ||

| Mus RPS19 | Forward | GCTGGCCAAACATAAAGAGC | 156 bp |

| Reverse | CTGGGTCTGACACCGTTTCT | ||

| Mus CPEB4 | Forward | AAGAAAATCCAGGGGACAGT | 189 bp |

| Reverse | AAGAAGGTGCTATCGCTGC | ||

| Mus CRYZ | Forward | CCACCAAGGAGGAATTTCAA | 158 bp |

| Reverse | AATCATTTTCCCCGTCTTCC |

Results

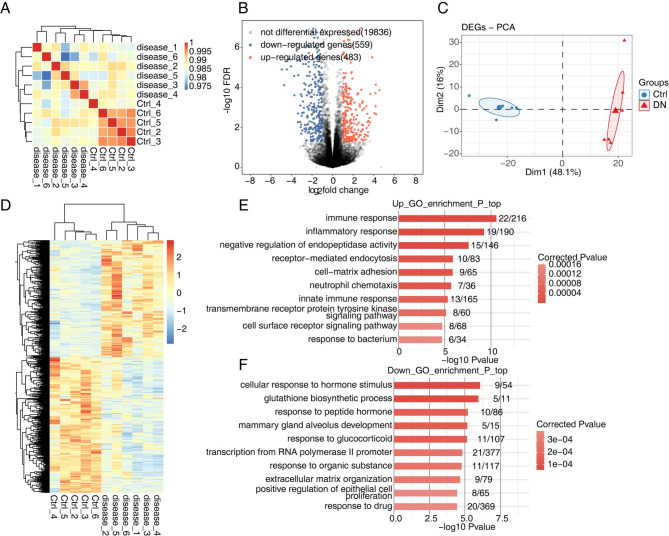

DEGs in diabetic rat kidney cortex vs. healthy rats

GSE117085 contains 6 DN rat samples and 6 control samples from the kidney cortex. Sample correlation analysis showed an obvious individual difference among the samples in the disease group, while sample variation among the control samples was small (Fig. 1A). Next, we calculated the DEGs between DN and control samples. Overall, 1042 DEGs were identified between DN samples vs. normal samples, including 559 downregulated and 483 upregulated DEGs (Fig. 1B). PCA provided an overview of the internal structure of DEGs between DN and control groups (Fig. 1C). Then, the clustering heat map showed the different expression patterns of the 1042 DEGs (Fig. 1D). GO enrichment analysis was then performed to further explore the biological process of DEGs. The top biological process (BP) terms of the GO analysis from upregulated or downregulated DEGs are presented in Fig. 1E and F, respectively. Upregulated DEGs were mainly associated with processes involved in immune response, inflammatory response, negative regulation of endopeptidase activity, receptor-mediated endocytosis, cell-matrix adhesion, neutrophil chemotaxis, and innate immune response (Fig. 1E); downregulated genes were mainly associated with cellular response to hormone stimulus, glutathione biosynthetic process, response to peptide hormone, mammary gland alveolus development, response to glucocorticoid, and transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter (Fig. 1F). Furthermore, the KEGG pathway analysis showed that the main pathways enriched in upregulated DEGs were cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, ECM-receptor interaction, and T‑cell receptor signaling pathway (Figure S1A), while renin-angiotensin system, steroid hormone biosynthesis, and bile secretion were mainly enriched by downregulated DEGs (Figure S1B). Moreover, Reactome pathway analysis revealed that the upregulated DEGs were mainly enriched in the chemokine receptors bind chemokines, interleukin-10 signaling, and post-translational protein phosphorylation, while downregulated DEGs were mainly enriched in the nuclear receptor transcription pathway, glutathione synthesis and recycling, and NGF-stimulated transcription (Figure S1C, D).

Fig. 1.

Transcriptome analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in non-diabetic rat kidney cortex (Ctrl) and diabetic rat kidney cortex (Disease). (A) The hierarchical clustering heat map shows sample correlation between Disease and Ctrl samples. (B) The volcano plot shows all DEGs between Disease and Ctrl samples. P-value ≤ 0.05 and FC (fold change) ≥ 1.5 or 0.75. (C) Principal component analysis (PCA) based on reads per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped (FPKM) value of all DEGs. The ellipse for each group is the confidence ellipse. (D) The hierarchical clustering heat map shows expression levels of all DEGs. (E, F) The bar plot shows the most enriched GO biological process results of the up-regulated DEGs (E) and down-regulated DEGs (F)

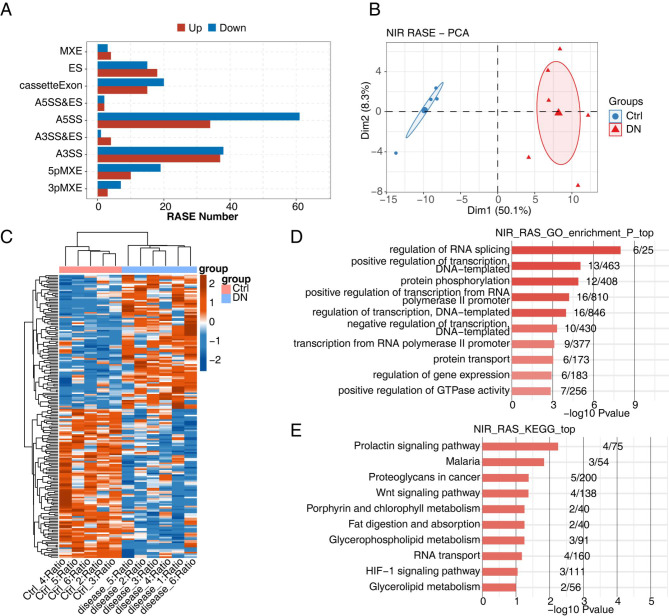

The regulated alternative splicing events and genes in DN rat kidney cortex

Alternative splicing (AS) is one of the main contributors to the diversity of gene transcripts that may contribute to the development of DN [11]. Thus, we made a comprehensive analysis of AS pattern in GSE117085. In total, 35,693 high-confidence ASEs were detected in DN and normal rat kidney cortex transcriptome, including 2282 known ASEs and 33,411 novel ASEs (Figure S2A). Next, ASEs in DN rat and control were compared, and 423 RASEs with high confidence were found. Among these RASEs, the numbers of A3SS and A5SS were relatively high (Fig. 2A). PCA result showed a clear difference between the DN group and the control group for both non-intron retention (NIR) RASEs (Fig. 2B) and intron retention (NIR) RASEs (Figure S2B). In addition, the clustering heat map showed significantly different PSI levels of NIR RASEs (Fig. 2C) and IR RASEs (Figure S2C). GO enrichment analysis showed that the top three functions of RASGs were regulation of RNA splicing, positive regulation of transcription DNA template, and protein phosphorylation; less common functions included positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter, negative regulation of transcription DNA-template, transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter, protein transport, regulation of gene expression, and positive regulation of GTPase activity (Fig. 2D). In addition, enriched KEGG pathways included those involved in the prolactin signaling pathway, malaria, and proteoglycans in cancer, followed by the wnt signaling pathway, porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism, fat digestion and absorption, glycerophospholipid metabolism, RNA transport, and glycerolipid metabolism (Fig. 2E). Reactome pathway analysis revealed the nuclear receptor transcription pathway, prolactin receptor signaling, and GRB7 events in ERBB2 signaling (Figure S2D).

Fig. 2.

Transcriptome analysis of alternative splicing regulation in disease and Ctrl samples. (A) The bar plot shows the number of all significant regulated alternative splicing events (RASEs). X-axis: RASE number. Y-axis: the different types of AS events. (B) PCA based on PSI (percent-spliced-in) value of all non-intron retention (NIR) RASEs. The ellipse for each group is the confidence ellipse. (C) PSI heat map of all significant NIR RASEs. AS filtered should have detectable splice. Junctions in all samples and at least 80% of samples should have > = 10 splice junction supporting reads. (D) Bar plot showing the most enriched GO biological process results of the NIR-regulated alternative splicing genes (RASGs). (E) Bar plot showing the most enriched KEGG pathways results of the NIR RASGs

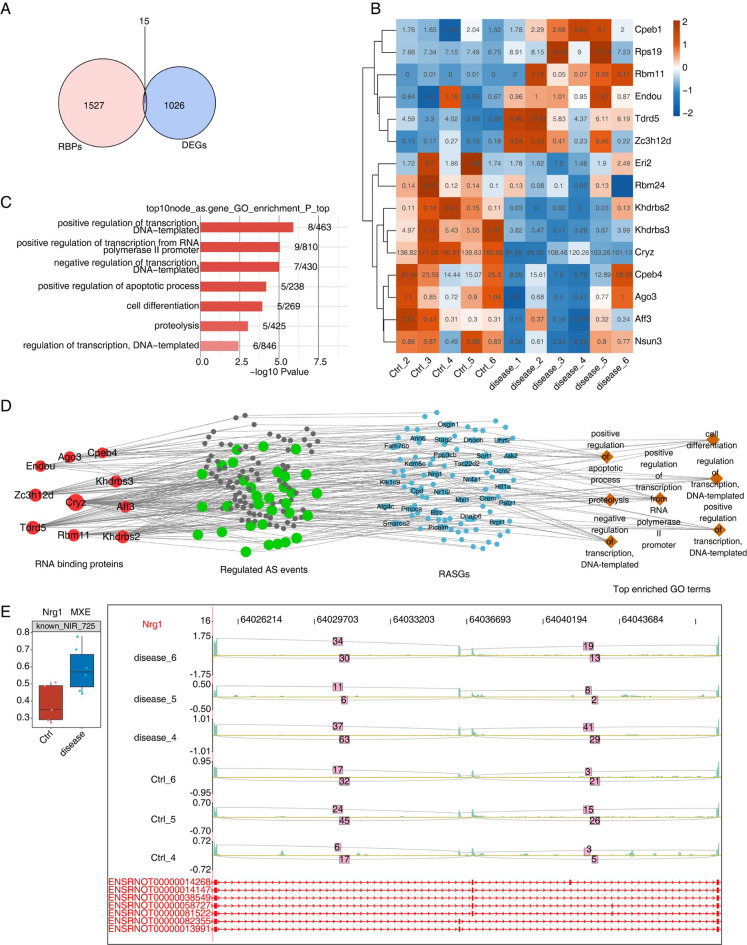

Differentially expressed RBPs are co-expressed with the alternative splicing genes

Dysregulated ASEs may be modulated by differentially expressed RBPs [12]. To further elucidate the underlying mechanisms of dysregulated alternative splicing in DN, we analyzed the transcriptome abnormalities of RBP genes using an overlapping analysis of the RBP list and the DEGs discovered in the rat RNA-seq data above. A total of 1042 DEGs were identified between DN samples vs. normal samples, among which 15 RBPs were differentially expressed (Fig. 3A). The heat map showed a significantly different distribution of the 15 RBPs (Fig. 3B); the number represents the value of each sample expression, while the color (from red to green) indicates the expression level of multiple genes in multiple samples. Previous studies found that certain RBP genes can influence target gene expression by AS, and the level of that RBP gene may be associated with the PSI levels of ASEs of that target gene [22]. Therefore, the Spearman correlation for each differentially expressed RBP and RASE pair was calculated, and a dysregulation network was created (Fig. 3D). We discovered that 13 RBPs regulate tens of RASEs. Among RASG associated with RBPs, NRG1, ARV1, SL1C12A1, CP, KRT7, and CDK13 showed prominent change (Fig. 3E and S3C). The top enriched GO biological processes of co-disturbed RASGs included positive regulation of the apoptotic process, proteolysis, and positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter (Fig. 3C). Enriched KEGG pathways included those involved in RNA transport, porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism, and fat digestion and absorption (Figure S3A). Reactome pathway analysis revealed that nuclear receptor transcription pathway, GRB7 events in ERBB2 signaling, and SLBP independent processing of histone pre-mRNAs (Figure S3B).

Fig. 3.

Correlation analysis between differentially expressed RNA binding protein genes and NIR RASEs. (A) Venn diagram showing differentially expressed RNA binding protein genes (RBPs). (B) The hierarchical clustering heat map shows expression levels of differential expressed RBPs in A. (C) The bar plot exhibits the most enriched GO biological process results illustrated for RASGs co-disturbed by top hub RBPs. (D) The co-deregulation of alternative splicing network between top hub RBPs (the red color represents the number of connections) and RASEs (the green circles include NIR RASEs) in DN. The top enriched GO biological process of co-disturbed RASGs is shown in blue and brown color. (E) The box plot showed PSI levels of NRG1, which detected mutually exclusive exons (MXE), and the IGV-sashimi plot showed the RASEs and binding sites across mRNA of NRG1. Reads distribution of RASE was plotted in the up panel, and the transcripts of each gene are shown below

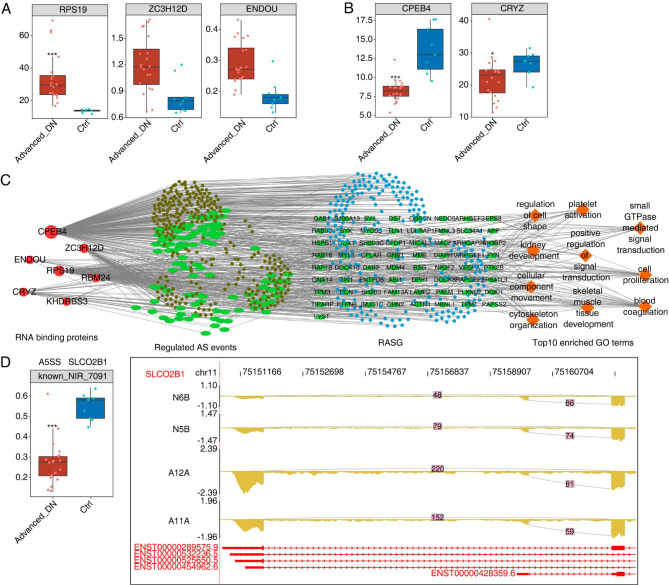

RBPs-alternative splicing co-expression networks on DN

To make a solid validation of DN-related RBPs detected in rat samples, the GSE142025 dataset from human samples was downloaded and analyzed for validation. Seven RBPs showed (ZC3H12D, ENDOU, CPEB4, RBM24, KHDRBS3, CRYZ, and RPS19) consistent expression changes in human samples (DN vs. control samples). Among them, three RBPs, i.e., RPS19, CPEB4, and CRYZ, revealed significant differences (Fig. 4A, B). We also found that dozens of RASEs were correlated with expression levels of the seven RBPs in human samples (Fig. 4C). GO biological process of co-disturbed RASGs was highly enriched for regulation of cell shape, kidney development, and cellular component movement (Fig. 4C). Among RASGs associated with RBPs, several genes (SLCO2B1, TPM1, TACC1, WNK1, GALNT11, SLC26A6, MAPKAP1, LYST) had prominent changes, which should be further investigated (Fig. 4D and S4A).

Fig. 4.

RBPs-alternative splicing co-expression networks on diabetic nephropathy in GSE142025 datasets. (A, B) Box plot shows expression levels of upregulated (A) or downregulated RBPs (B) in Fig. 3A. *** P < 0.001, * P < 0.05. (C) The co-deregulation of alternative splicing network between top hub RBPs (red color) and RASEs (green color, which includes NIR RASEs in GSE142025 datasets) in DN. The top enriched GO biological process of co-disturbed RASGs is shown in blue and brown color. (D) The box plot shows PSI levels of SLCO2B1, which detected alternative 5’splice site (A5SS), and IGV-sashimi plot shows the RASEs and binding sites across mRNA of SLCO2B1. Reads distribution of RASE is plotted in the up panel, and the transcripts of each gene are shown below. *** P < 0.001

Validation of the detected RBP genes in Nephroseq database

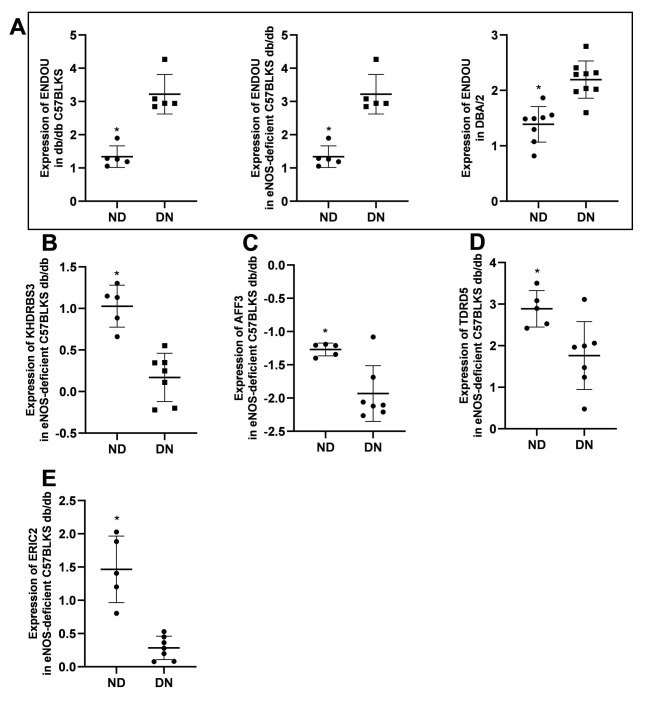

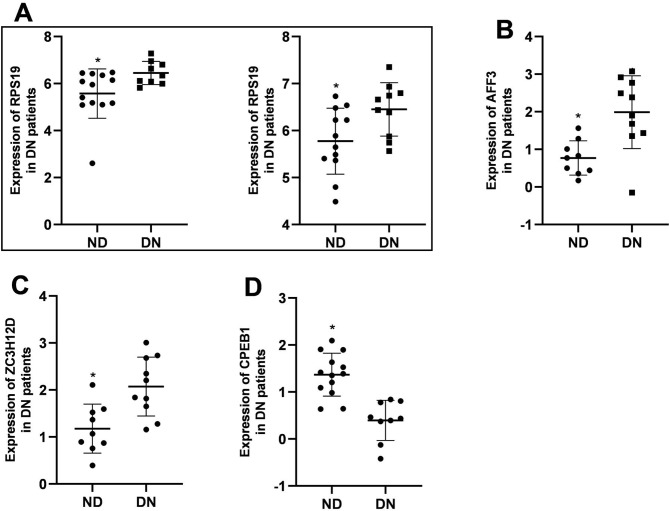

Nephroseq is a powerful database incorporating pre-analyzed genome-wide gene expression data and clinical data [23]. Using the data from Nephroseq v5 online platform (http://v5.nephroseq.org), we further validated the expression levels of the detected 15 RBP genes in kidney and explored the correlation of these genes with clinical data. We found that the expression of ENDOU was increased (Fig. 5A) while that of KHDRBS3, AFF3, TDRD5, and ERIC2 were decreased (Fig. 5B-E) in DN mice compared with normal controls. The expression levels of RPS19, AFF3, and ZC3H12D were increased (Fig. 6A-C), while that of CPEB1 was decreased in patients with DN compared to normal control (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 5.

The expression pattern of RBP genes in Nephroseq database. (A) The expression of ENDOU increased in db/db C57BLKS (left panel), eNOS-deficient C57BLKS db/db (middle panel), and DBA/2 mice (right panel). (B) The expression of KHDRBS3 decreased in eNOS‐deficient C57BLKS db/db mice. (C) The expression of AFF3 decreased in eNOS‐deficient C57BLKS db/db mice. (D) The expression of TDRD5 decreased in eNOS‐deficient C57BLKS db/db mice. (E) The expression of ERIC2 decreased in eNOS‐deficient C57BLKS db/db mice. * P < 0.05, ND vs. DN

Fig. 6.

The expression pattern of RBP genes in kidney in DN patients. (A) The expression of RPS19 increased in DN patients of Woroniecka Diabetes TubInt (left panel) and Schmid Diabetes TubInt (right panel). (B) The expression of AFF3 increased in DN patients of ERCB Nephrotic Syndrome TubInt. (C) The expression of ZC3H12D increased in DN patients of ERCB Nephrotic Syndrome TubInt. (D) The expression of CPEB1 decreased in DN patients of Woroniecka Diabetes TubInt. * P < 0.05, ND vs. DN

Exploring the correlation of RBP genes with urine ACR and eGFR in Nephroseq database

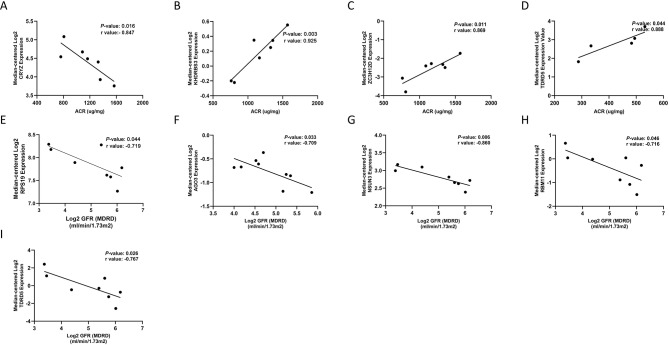

Both urine ACR and eGFR are important biomarkers for DN. Urine ACR reflects the severity of albuminuria, while eGFR can be used to assess impaired glomerular filtration rate [24]. The level of two markers also reflects the activity and severity of DN. By exploring the correlation of RBP genes with ACR and eGFR, we can further determine the clinical significance of these genes. We noted that the expression level of CRYZ in kidney was negatively correlated with ACR in DN mice (Fig. 7A), while that of KHDRBS3, ZC3H12D, and TDRD5 were positively correlated with ACR (Fig. 7B-D); the expression levels of RPS19, AGO3, NSUN3, RBM11, and TDRD5 in kidney were negatively correlated with eGFR in DN patients (Fig. 7E-I).

Fig. 7.

Correlation of RBP gene with ACR and eGFR in DN mouse model and DN patients. (A) CRYZ is negatively correlated with ACR in DN mouse models. (B) KHDRBS3 is positively correlated with ACR in DN mouse models. (C) ZC3H12D is positively correlated with ACR in DN mouse models. (D) TDRD5 is positively correlated with ACR in DN mouse models. ACR, albumin to creatinine ratio. (E) RPS19 is negatively correlated with eGFR in DN patients. (F) AGO3 is negatively correlated with eGFR in DN patients. (G) NSUN3 is negatively correlated with eGFR in DN patients. (H) RBM11 is negatively correlated with eGFR in DN patients. (I) TDRD5 is negatively correlated with eGFR in DN patients. eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate

In vivo experimental verification

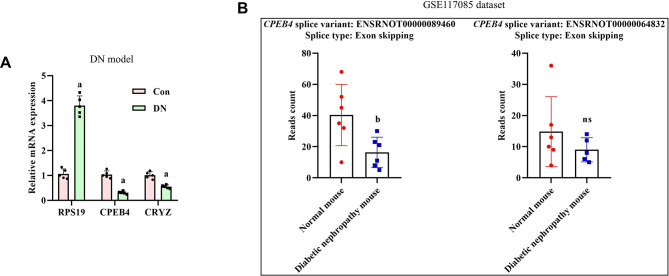

To support the aforementioned findings, we conducted in vivo validation experiments. We assessed the mRNA expression levels of RPS19, CPEB4, and CRYZ in the STZ-induced DN model. As illustrated in Fig. 8A, compared to the control group, the DN group exhibited a significant upregulation in RPS19 mRNA expression, while the mRNA levels of CPEB4 and CRYZ were markedly downregulated. These results are consistent with the conclusions derived from the analysis of the GSE142025 dataset and the Nephroseq database. To further validate the mRNAs discovered in in vivo experiments, we analyzed the different splice variants (SVs) of genes derived from mice and humans using the GSE117085 and GSE142025 datasets. In the mouse dataset (GSE117085), we identified two SVs of CPEB4: ENSRNOT00000064832 and ENSRNOT00000089460. CPEB4 exhibited three types of alternative splicing events: Alternative 5’ splice site (A5SS), Alternative 3’ splice site (A3SS), and Exon Skipping (ES). Notably, the reads count for ENSRNOT00000089460 undergoing ES were significantly lower in the DN group compared to the control group (Fig. 8B, Supplement Table 1). This trend aligns with our in vivo experimental findings, which showed reduced CPEB4 in DN. Additionally, some mice did not exhibit detectable CPEB4 splice variants (SVs). To understand these discrepancies, we compared our findings with a human dataset (GSE142025). This comparison revealed that the detection of SVs can be inconsistent across different datasets (Supplement Table 2). This inconsistency may result from low expression levels of specific SVs, tissue-specific expression patterns, or limitations of the detection methodologies used. In the human dataset, DN was categorized into Advanced and Early stages. CPEB4 has 14 SVs, of which 4 were suitable for comparison. Notably, the expression levels of these 4 CPEB4 SVs were lower in patients with Advanced DN compared to healthy individuals. For CRYZ, among its 12 SVs, 7 were available for comparison. However, significant differences between Advanced DN patients and healthy individuals were observed only for ENST00000370872.7 (ES) and ENST00000417775.5 (cassetteExon). RPS19 has 2 SVs, and their expression levels were elevated in Advanced DN patients compared to healthy individuals.

Fig. 8.

Quantitative real-time PCR to detect the alternative splicing in DN model (A), splice variants of CPEB4 in the GSE117085 dataset (B).aP < 0.05 vs. the Con group, bP < 0.05 vs. the normal mouse group, nsP > 0.05 vs. the normal mouse group

Discussion

We analyzed two datasets from the SRA database with bioinformatics tools in this study, after which we acquired a comprehensive AS profile and built an RBP-AS co-dysregulation network in DN. As a result, a series of specific RASGs and clinically relevant RBPs were discovered, which provides clues for further research. Finally, the expression levels of alternatively spliced RNAs were validated through animal experiments, providing robust support for this study.

Aberrant pre-mRNA alternative splicing has been widely accepted as a novel contributor to disease [25]. In this study, 35,693 ASEs were identified in kidney from rat samples. Approximately 90% of ASEs were reported for the first time. Among them, 423 events were differentially regulated between DN rats and normal controls, suggesting RASEs are prevalent in DN. GO enrichment analysis showed that the top three functions of RASGs were regulation of RNA splicing, positive regulation of transcription DNA template, and protein phosphorylation. Mutations in regulatory sequences and the transcription factors, cofactors, and noncoding RNAs have been found in different diseases, including diabetes. For example, Liu et al. found that methylation levels may increase abnormally under high glucose concentrations [26].

KEGG analysis further showed that RASGs were mainly enriched in lipid metabolism pathways, such as fat digestion and absorption, glycerophospholipid metabolism, and glycolipid metabolism. Lipid metabolism in DN patients is usually altered, making cellular components such as the podocyte more sensitive to injury and exacerbating DN progression [27]. In addition, disruption of lipid metabolism results in mitochondrial malfunction and lipid change in the mitochondria [28]. Although disordered lipid metabolism in DN is a well-known occurrence, abnormal alternative splicing of genes involved in lipid metabolism has been rarely studied and may be worthy of further exploration.

RBPs can function as splice factors and can participate in AS process by forming a splicing regulatory machine. Analysis of RBP binding profiles with co-regulated AS provides an effective means for unraveling molecular mechanisms of disease. Human genetic studies provided new evidence that polymorphisms and mutations in RBPs are linked to diabetes [29]. In this study, we identified 15 differentially expressed RBPs between DN rat and control samples and seven RBPs were also differentially expressed between DN patients and controls. We did not identify shared RASEs in human and rat samples. Alternative splicing patterns are more similar between organs within a species than between identical organs from different species [12]. The RBP-RASE co-expression network was then constructed in rat and human samples. Dozens of RASEs were intimately associated with RBPs, implying these RBPs may regulate these RASEs. The two regulatory systems shared several RBPs, suggesting an abnormal RBP-AS regulatory relationship in DN patients and rats. Several prominent RASGs were identified from the RBP-RASE regulation network in human and rat samples, thus providing a useful clue for further research of abnormal AS in DN.

In recent years, many clinical trials have addressed DN; however, most failed to provide relevant insight [30–34]. This could be due to the species difference between human and animal models, which suggests that pathogenesis gained in an animal model cannot be successfully translated into human clinical trials. The shared RBPs that have a good correlation with ACR and eGFR in both human and animal models are helpful in revealing the pathogenesis of DN patients. In this study, 15 differentially expressed RBPs in rats were validated in GSE33744 of human samples and the Nephroseq dataset. Most had a consistent statistically significant expression in DN patients and DN mice. AFF3 is significantly expressed in the DN mice model while being downregulated in DN patient cohort in the Nephroseq dataset. Despite their high resemblance, the discrepancy in AFF3 expression between DN patients and mice mode may reflect some variances between the two species. Variants in AFF3 have been reported in a genome-wide association study (the total human sample set included 7,514 cases and 9,045 reference samples) for type 1 diabetes [35]. Moreover, KHDRBS3 (KH RNA binding domain containing signal transduction associated 3) and TDRD5 (Tudor domain containing 5) were decreased in DN mice compared with control, and both were positively correlated with ACR (a well-known marker to identify kidney disease that can occur as a complication of diabetes) in DN mice.

In addition, Ribosomal Protein S19 (RPS19) expression was increased in DN patients in the GSE33744 dataset (human samples) and in DN patients in the Nephroseq dataset. Furthermore, RPS19 expression was negatively correlated with eGFR in DN patients. Mutations in the RPS19 protein, which is required for a specific step in the maturation of 40 S ribosomal subunits, are associated with Diamond Blackfan anemia [36]. However, to date, no association between RPS19 and DN has been reported. Recent research has identified Cytoplasmic Polyadenylation Element Binding Protein 4 (CPEB4) as a critical gene associated with diabetic nephropathy, suggesting its involvement in the pathogenesis of this condition [37, 38]. CPEB4, as a pivotal RNA-binding protein, plays a critical role in various physiological and pathological processes [39, 40]. These findings suggest that CPEB4 may be involved in the pathological progression of DN, although the precise mechanisms remain unclear. Research has indicated that the CPEB4 protein plays a significant role in regulating alternative splicing events. However, current studies have primarily focused on neurogenesis and autism [41, 42]. Nevertheless, current research on the regulation of alternative splicing by CPEB4 specifically in DN remains limited. The comprehensive role of CPEB4 in modulating alternative splicing within DN is still unclear. Studies have identified an association between Crystallin Zeta (CRYZ) and ovarian cancer drug resistance, as well as pulmonary arterial hypertension [43, 44]. Although Gulzar Alam et al. reported that CRYZ is highly expressed in the kidney, they did not elucidate its connection to regulated alternative splicing [45]. Moreover, current research on CRYZ and regulated alternative splicing is quite limited. In our study, we observed high expression of the alternatively spliced gene RPS19 and low expression of CPEB4 and CRYZ in both the GSE142025 dataset and the Nephroseq database. We further confirmed these findings in animal models.

SVs are mRNA variants generated through alternative splicing, enabling a single gene to encode multiple protein isoforms. This is crucial in regulating gene expression and cellular function, particularly in disease conditions where aberrant splicing can occur and result in dysfunction. Studies have indicated that approximately 94% of multi-exon genes in humans undergo alternative splicing [46]. Studies by Ting et al. have demonstrated an association between the expression of splicing variants of the SDF-1 gene and the development of diabetic nephropathy [47]. Jung et al. discovered that alternative splicing of the CHI3L1 gene can regulate protein secretion, which may be relevant to the progression of diabetic nephropathy [48]. Given that we performed in vivo experiments, we focused on analyzing the expression levels of SVs in the GSE117085 dataset. The discovery that the SV ENSRNOT00000089460 of CPEB4 undergoes ES and exhibits decreased read counts in DN mice highlights the crucial role of alternative splicing in disease mechanisms. Similarly, one limitation of this study is the absence of SV expression level detection in DN mice. However, to address this limitation, we analyzed SV expression levels in the GSE142025 dataset and found differential expression of certain SVs between patients and healthy individuals. Through the analysis of these two datasets, we also observed that SV expression is complex and variable. Therefore, future studies should not only examine SV expression levels in mice but also investigate the relationship between SVs and DN pathogenesis in the context of DN progression. Furthermore, exploring the correlation between clinical indicators of DN and SVs may offer new insights for early screening and prevention of DN. Altogether, the above findings suggest that RPS19, CPEB4, and CRYZ may reflect the severity of DN and could be further explored.

To sum up, the present study suggests the involvement of dysregulated RNA binding protein and alternative splicing regulatory networks in DN, which seems to be translated from species to species. Yet, this preliminary study needs to be further verified using cell and animal models and clinical trials. In addition, future studies are needed to explore the potential clinical meaning of the molecules identified in this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1: Figure S1. Transcriptome analysis of DEGs in diabetic rat kidney cortex (Disease) and non-diabetic rat kidney cortex (Ctrl). (A, B) The bar plot shows the most enriched KEGG pathways results of the up-regulated (A) and down-regulated DEGs (B). (C, D) The scatter plot shows the most enriched Reactome pathways results of the up-regulated (C) and down-regulated DEGs (D).

Supplementary Material 2: Figure S2. Alternative splicing regulation in Ctrl and Disease samples. (A) The bar plot shows the number of detected alternative splicing events (ASEs). X-axis: ASE number; Y-axis: the different types of AS events. (B) PCA based on PSI value of all intron retention (IR) RASEs. The ellipse for each group is the confidence ellipse. (C) PSI heatmap of all significant IR RASEs. AS filtered should have detectable splice junctions in all samples, and at least 80% of samples should have ≥ 10 splice junction supporting reads. (D) The scatter plot exhibiting the most enriched Reactome pathways results of the NIR RASGs.

Supplementary Material 3: Figure S3. Correlation analysis between NIR RASEs and differentially expressed RBP genes. (A) Bar plot exhibits the most enriched KEGG pathways results illustrated for RASGs co-disturbed by top hub RBPs. (B) Scatter plot exhibits the most enriched Reactome pathways results illustrated for RASGs co-disturbed by top hub RBPs. (C) Box plot shows PSI levels of Arv1, which detected alternative 3’splice site (A3SS), and the IGV-sashimi plot shows the regulated alternative splicing events and binding sites across mRNA of Arv1. Reads distribution of RASE is plotted in the up panel, and the transcripts of each gene are shown below.

Supplementary Material 4: Figure S4. Verifying the regulation of alternative splicing on diabetic nephropathy in GSE142025 datasets. (A) The box plot shows PSI levels of TPM1, which detected alternative 5’splice site (A5SS), and the IGV-sashimi plot (B) shows the regulated alternative splicing events and binding sites across mRNA of TPM1. Reads distribution of RASE is plotted in the up panel, and the transcripts of each gene are shown below. *** P < 0.001.

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable.

Author contributions

Yu Wang performed the bioinformatic analysis and drafted the manuscript. Jing-jing Zhang and Qian Tang participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Data availability

SRA database (https://catalog.data.gov/dataset/sequence-read-archive-sra, accession number: SRP153385 and SRP237545. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Declarations

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the IACUC (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee) of Hubei Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Laboratory Animal Management and Use Committee (Ethical approval number: Safety Assessment Center (Fu) No. 202410271). The study adhered to the regulations for the management of experimental animals and/or met the ARRIVE 2.0 requirements.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.McCullough KP, Morgenstern H, Saran R, Herman WH, Robinson BM. Projecting ESRD incidence and prevalence in the united States through 2030. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30(1):127–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang L, Long J, Jiang W, et al. Trends in chronic kidney disease in China. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(9):905–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, et al. Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist Irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(12):851–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson BV, Correa-Rotter R, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1436–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fineberg D, Jandeleit-Dahm KA, Cooper ME. Diabetic nephropathy: diagnosis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9(12):713–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amorim RG, Guedes GDS, Vasconcelos SML, Santos JCF. Kidney disease in diabetes mellitus: Cross-Linking between hyperglycemia, redox imbalance and inflammation. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019;112(5):577–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keren H, Lev-Maor G, Ast G. Alternative splicing and evolution: diversification, exon definition and function. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(5):345–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oltean S, Bates DO. Hallmarks of alternative splicing in cancer. Oncogene. 2014;33(46):5311–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dlamini Z, Mokoena F, Hull R. Abnormalities in alternative splicing in diabetes: therapeutic targets. J Mol Endocrinol. 2017;59(2):R93–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J, Yu S, Hu W, et al. Comprehensive analysis of cell population dynamics and related core genes during vitiligo development. Front Genet. 2021;12:627092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oltean S, Qiu Y, Ferguson JK, et al. Vascular endothelial growth Factor-A165b is protective and restores endothelial glycocalyx in diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(8):1889–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ule J, Blencowe BJ. Alternative splicing regulatory networks: functions, mechanisms, and evolution. Mol Cell. 2019;76(2):329–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maguire SL, Leonidou A, Wai P, et al. SF3B1 mutations constitute a novel therapeutic target in breast cancer. J Pathol. 2015;235(4):571–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen M, Manley JL. Mechanisms of alternative splicing regulation: insights from molecular and genomics approaches. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(11):741–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li T, Li S, Chen D, et al. Transcriptomic analyses of RNA-binding proteins reveal eIF3c promotes cell proliferation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2017;108(5):877–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan Y, Yi Z, D’Agati VD, et al. Comparison of kidney transcriptomic profiles of early and advanced diabetic nephropathy reveals potential new mechanisms for disease progression. Diabetes. 2019;68(12):2301–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, et al. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 2013;14(4):R36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. EdgeR: a bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(1):139–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin L, Li G, Yu D, et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals the complexity of alternative splicing regulation in the fungus verticillium dahliae. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1):130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xia H, Chen D, Wu Q, et al. CELF1 preferentially binds to exon-intron boundary and regulates alternative splicing in HeLa cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech. 2017;1860(9):911–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie C, Mao X, Huang J et al. KOBAS 2.0: a web server for annotation and identification of enriched pathways and diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 39(suppl_2):W316–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Fu XD, Ares M Jr. Context-dependent control of alternative splicing by RNA-binding proteins. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15(10):689–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.You S, Xu J, Wu B et al. Comprehensive Bioinformatics Analysis Identifies POLR2I as a Key Gene in the Pathogenesis of Hypertensive Nephropathy. Front Genet. 2021; 12:698570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Lopez-Giacoman S, Madero M. Biomarkers in chronic kidney disease, from kidney function to kidney damage. World J Nephrol. 2015;4(1):57–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang GS, Cooper TA. Splicing in disease: disruption of the splicing code and the decoding machinery. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8(10):749–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J, Lang G, Shi J. Epigenetic regulation of PDX-1 in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2021;14:431–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Herman-Edelstein M, Scherzer P, Tobar A, Levi M, Gafter U. Altered renal lipid metabolism and renal lipid accumulation in human diabetic nephropathy. J Lipid Res. 2014;55(3):561–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ducasa GM, Mitrofanova A, Fornoni A. Crosstalk between lipids and mitochondria in diabetic kidney disease. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19(12):144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nutter CA, Kuyumcu-Martinez MN. Emerging roles of RNA-binding proteins in diabetes and their therapeutic potential in diabetic complications. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2018;9(2):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Tuttle KR, Bakris GL, Toto RD, et al. The effect of Ruboxistaurin on nephropathy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(11):2686–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brosius FC, Tuttle KR, Kretzler M. JAK Inhibition in the treatment of diabetic kidney disease. Diabetologia. 2016;59(8):1624–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Navarro-González JF, Mora-Fernández C, Muros de Fuentes M, et al. Effect of Pentoxifylline on renal function and urinary albumin excretion in patients with diabetic kidney disease: the PREDIAN trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(1):220–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Zeeuw D, Coll B, Andress D, et al. The endothelin antagonist Atrasentan lowers residual albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(5):1083–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heerspink HJL, Parving HH, Andress DL, et al. Atrasentan and renal events in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease (SONAR): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10184):1937–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barrett JC, Clayton DG, Concannon P, et al. Genome-wide association study and meta-analysis find that over 40 loci affect risk of type 1 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2009;41(6):703–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martinez Barrio A, Eriksson O, Badhai J, et al. Targeted resequencing and analysis of the Diamond-Blackfan anemia disease locus RPS19. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(7):e6172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Z, Fu X, Zhou F, Zhang D, Xu Y, Fan Z, Wen S, Shao Y, Yao Z, He Y. Huaju Xiaoji formula regulates ERS-lncMGC/miRNA to enhance the renal function of hypertensive diabetic mice with nephropathy. J Diabetes Res. 2024;2024(1):6942156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Song J, Yang H. Down-regulation of CPEB4 alleviates preeclampsia through the Inhibition of ferroptosis by PFKFB3. Crit Reviews™ Eukaryot Gene Expression. 2024;34(3):73–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Kozlov E, Shidlovskii YV, Gilmutdinov R, Schedl P, Zhukova M. The role of CPEB family proteins in the nervous system function in the norm and pathology. Cell Bioscience. 2021;11(1):64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riechert E, Kmietczyk V, Stein F, Schwarzl T, Sekaran T, Jürgensen L, Kamuf-Schenk V, Varma E, Hofmann C, Rettel M, Gür K. Identification of dynamic RNA-binding proteins uncovers a Cpeb4-controlled regulatory cascade during pathological cell growth of cardiomyocytes. Cell Rep. 2021;35(6):109100. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Qu W, Jin H, Chen BP, Liu J, Li R, Guo W, Tian H. CPEB3 regulates neuron-specific alternative splicing and involves neurogenesis gene expression. Aging. 2020;13(2):2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parras A, Anta H, Santos-Galindo M, Swarup V, Elorza A, Nieto-González JL, Picó S, Hernández IH, Díaz-Hernández JI, Belloc E, Rodolosse A. Autism-like phenotype and risk gene mRNA deadenylation by CPEB4 mis-splicing. Nature. 2018;560(7719):441–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lulli M, Trabocchi A, Roviello G, Catalano M, Papucci L, Parenti A, Molli A, Napoli C, Landini I, Schiavone N, Lapucci A. Targeting z-Crystallin by aspirin restores the sensitivity to cisplatin in resistant A2780 ovarian cancer cells. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1377028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Xu X, Li H, Wei Q, Li X, Shen Y, Guo G, Chen Y, He K, Liu C. Novel targets in a high-altitude pulmonary hypertension rat model based on RNA-seq and proteomics. Front Med. 2021;8:742436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alam G, Luan Z, Gul A, Lu H, Zhou Y, Huo X, Li Y, Du C, Luo Z, Zhang H, Xu H. Activation of farnesoid X receptor (FXR) induces Crystallin zeta expression in mouse medullary collecting duct cells. Pflügers Archiv-European J Physiol. 2020;472:1631–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stevens M, Oltean S. Alternative splicing in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(6):1596–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ting KH, Yang PJ, Su SC, Tsai PY, Yang SF. Effect of SDF-1 and CXCR4 gene variants on the development of diabetic kidney disease. Int J Med Sci. 2024;21(14):2851–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jung H, Kim YE, Kim EM, Kim KK. Alternative splicing of CHI3L1 regulates protein secretion through conformational changes. Genes Genomics. 2025;47(5):571–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Figure S1. Transcriptome analysis of DEGs in diabetic rat kidney cortex (Disease) and non-diabetic rat kidney cortex (Ctrl). (A, B) The bar plot shows the most enriched KEGG pathways results of the up-regulated (A) and down-regulated DEGs (B). (C, D) The scatter plot shows the most enriched Reactome pathways results of the up-regulated (C) and down-regulated DEGs (D).

Supplementary Material 2: Figure S2. Alternative splicing regulation in Ctrl and Disease samples. (A) The bar plot shows the number of detected alternative splicing events (ASEs). X-axis: ASE number; Y-axis: the different types of AS events. (B) PCA based on PSI value of all intron retention (IR) RASEs. The ellipse for each group is the confidence ellipse. (C) PSI heatmap of all significant IR RASEs. AS filtered should have detectable splice junctions in all samples, and at least 80% of samples should have ≥ 10 splice junction supporting reads. (D) The scatter plot exhibiting the most enriched Reactome pathways results of the NIR RASGs.

Supplementary Material 3: Figure S3. Correlation analysis between NIR RASEs and differentially expressed RBP genes. (A) Bar plot exhibits the most enriched KEGG pathways results illustrated for RASGs co-disturbed by top hub RBPs. (B) Scatter plot exhibits the most enriched Reactome pathways results illustrated for RASGs co-disturbed by top hub RBPs. (C) Box plot shows PSI levels of Arv1, which detected alternative 3’splice site (A3SS), and the IGV-sashimi plot shows the regulated alternative splicing events and binding sites across mRNA of Arv1. Reads distribution of RASE is plotted in the up panel, and the transcripts of each gene are shown below.

Supplementary Material 4: Figure S4. Verifying the regulation of alternative splicing on diabetic nephropathy in GSE142025 datasets. (A) The box plot shows PSI levels of TPM1, which detected alternative 5’splice site (A5SS), and the IGV-sashimi plot (B) shows the regulated alternative splicing events and binding sites across mRNA of TPM1. Reads distribution of RASE is plotted in the up panel, and the transcripts of each gene are shown below. *** P < 0.001.

Data Availability Statement

SRA database (https://catalog.data.gov/dataset/sequence-read-archive-sra, accession number: SRP153385 and SRP237545. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].