Abstract

Kidney tubular damage is an important prognostic determinant in diabetic kidney disease (DKD). A vital homeostatic function of the proximal tubule is active tubular secretion of waste products via organic anion transporters (OATs), including protein-bound uremic toxins (PBUTs) that accumulate in plasma in tubular dysfunction. We here hypothesize that PBUT clearance may be a sensitive tubular function marker, and tested this in a DKD mouse model and in type 2 diabetic patients. Among the PBUTs with the highest OAT affinity (i.e., indoxyl sulfate (IS), hippuric acid (HA) and kynurenic acid (KA)), plasma concentrations were higher and urinary excretions were lower 6 and 8 months after DKD induction in mice. These parameters correlated better with tubular atrophy, f4/80 scores and tubular injury markers than conventional filtration markers. In patients, the clearance of IS, HA, KA and p-cresyl sulfate (PCS) was associated with urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) and kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1), independent of eGFR. In multiple regression analysis, additionally adjusted for relevant risk factors for tubular injury, the clearance of IS, HA and PCS remained significantly associated with urinary NGAL. In conclusion, IS, HA, KA and PCS clearance may represent a biomarker of kidney tubular function in DKD.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-07248-3.

Keywords: Diabetic kidney disease, Tubular function marker, Protein-bound uremic toxins, Indoxyl sulfate, Hippuric acid

Subject terms: Biomarkers, Nephrology

Introduction

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is the leading cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and subsequent kidney failure requiring renal replacement therapy, and is associated with comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases and hypertension1. Early identification of the disease would allow timely intervention to delay its progression to the advanced stages and the onset of concurrent medical conditions. Since DKD is often asymptomatic at early stages, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the 2022 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Clinical Practice Guidelines recommend screening diabetic patients for estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and urinary albumin creatinine ratio (UACR) at least once per year2. Still, the lack of sensitivity and reliability of these measures in the diagnosis of DKD is recognized as well3. Recent evidence indicates that the efficiency of eGFR and albuminuria in risk prediction is limited in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D)4,5. Many diabetic patients with kidney disease have minimal or no albuminuria, and DKD could progress without albuminuria6. Furthermore, both markers primarily represent either loss of function (decrease in eGFR) or damage (albuminuria) at the glomerular level, which has long been thought to be the primary site of injury of diabetes-related kidney impairment. New studies highlighted the involvement of the proximal tubule in the pathogenesis of DKD as well and suggested that tubular lesions correlate better than glomerular lesions with kidney dysfunction7,8. Tubular injury markers appeared elevated earlier than microalbuminuria and were associated with an early decline in kidney function and progression of DKD9.

Proximal tubular secretion is an active process that can be influenced by various conditions and may not parallel GFR. Hyperglycemia in diabetic patients directly affects tubular cells via various mechanisms, including reactive oxygen species (ROS) overproduction and apoptosis, which are linked to DKD progression10. Protein overload in DKD may induce proximal tubular epithelial cell inflammation and tubulointerstitial fibrosis9. Tubular damage is an essential prognostic determinant of DKD11, and eGFR and albuminuria-based diagnostic methods are inefficient in detecting tubular damage12. Several tubular injury markers, such as kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1)13 and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL)14, have been identified for the detection of tubular injury in DKD. Although highly sensitive in detecting acute kidney failure, these markers may be less suitable for determining chronic tubular dysfunction.

Protein-bound uremic toxins (PBUTs) are small molecules (< 500 Da) derived from dietary proteins produced by gut microbial metabolism. Within the systemic circulation, these toxins are bound to plasma proteins, predominantly albumin, and are primarily eliminated by the kidneys through active tubular secretion. This process involves uptake via organic anion transporters (OAT1 and OAT3) at the proximal tubule cell basolateral membrane, followed by luminal efflux through transport proteins including multidrug resistance protein 4 (MRP4) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) at the apical membrane15,16. Once tubular function is impaired, PBUTs are inefficiently cleared and accumulate in plasma. Increased plasma indoxyl sulfate (IS) concentration has been reported at early stages of DKD, and correlated with renal function in diabetic patients17,18. Growing evidence has been pointing towards the relation between PBUT plasma concentration and the progression of CKD19–21 and kidney failure in DKD patients22. Furthermore, reduced clearance of PBUTs is associated with the progression of kidney disease and all-cause mortality23 and increased intestinal uptake of their precursor (p-cresol) was associated with cardiovascular events independent of eGFR24.

Here we hypothesize that plasma concentration and clearance of PBUTs may serve as biomarkers of kidney tubular function in DKD. To this end, we measured six prototypical PBUTs (IS, hippuric acid (HA), kynurenic acid (KA), p-cresyl glucuronide (PCG), p-cresyl sulfate (PCS) and indole-3-acetic acid (IAA)) in samples available from an experimental long term DKD mouse model and from diabetic patients, and investigated the associations of PBUT parameters with histological and/or biochemical markers of kidney tubular injury.

Results

Preclinical study

Evaluation of tubular damage in DKD mice

High-dose streptozotocin (STZ) induced diabetes mellitus in C57BL/6 mice, ensured by structural and functional features of DKD as documented previously25. For additional data, including morphological details, the reader is referred to that study. The characteristic features of kidney tubular damage were evident after 6 and 8 months following the induction of diabetes (Table 1). Examination of tubular histology using tubular atrophy scores (TAS) showed a tenfold increase after 6 months and 7.5-fold after 8 months (Table 1 and Suppl. Figure 1). Compared to the control mice, diabetic mice showed a significant increase in plasma and urinary markers of tubular injury. In contrast, markers for glomerular filtration (plasma Cr and Cys C) and glomerular damage (albuminuria) were not significantly elevated except for albuminuria after 8 months (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the control and DKD mice after 6 and 8 months.

| Parameters | 6 months | 8 months | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | DKD | Control | DKD | |

| N (% male) | 15(40) | 16 (44) | 19 (47) | 23 (61) |

| Urine volume (ml) | 1.52 ± 0.96 | 15.3 ± 10.5*** | 1.57 ± 1.09 | 21.6 ± 26.07*** |

| Plasma creatinine (μg/ml) | 1.97 ± 0.83 | 2.55 ± 1.10 | 1.55 ± 0.53 | 1.68 ± 0.43 |

| Plasma cystatin C (μg/ml) | 2.18 ± 1.59 | 2.50 ± 1.72 | 0.95 ± 0.53 | 1.51 ± 1.76 |

| Albuminuria (mg/g Cr) | 326 ± 91 | 420 ± 141 | 268 ± 158 | 413 ± 174** |

| Kim-1 gene expression | 0.04 ± 0.05 | 0.04 ± 0.04 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.03 ± 0.03* |

| Plasma NGAL (ng/ml) | 107 ± 40.5 | 174 ± 51.8*** | 76.5 ± 13.0 | 145 ± 14.8*** |

| Urine NGAL (mg/g Cr) | 0.23 ± 0.09 | 2.02 ± 2.02*** | 0.46 ± 0.31 | 39.1 ± 44.5** |

| Tubular atrophy scores | 0.17 ± 0.10 | 1.72 ± 0.50*** | 0.19 ± 0.15 | 1.43 ± 0.49*** |

| Creatinine clearance (ml/24 h) | 246 ± 147 | 280 ± 122 | 337 ± 164 | 537 ± 432 |

Data are mean ± SD. The non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test or parametric unpaired t-test was performed for statistical analysis, based on the data normality determined by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05. Kim-1: kidney injury molecule-1; NGAL: neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin.

Significant values are in [bold].

DKD mice show increased PBUT plasma concentrations and decreased clearance

Among the PBUTs with high OAT affinity, i.e., IS, HA and KA26, plasma concentrations were 1.7-, 2.4- and 1.9-fold higher after 6 months and 1.9-, 2.4- and 2.2-fold higher after 8 months in DKD, respectively (Fig. 1A–C). Urine PBUT/creatinine ratios normalized for plasma PBUT, used as a surrogate for PBUT clearance, were 2.4-, 5.4- and 2.3-fold lower after 6 months and 2.3-, 1.6-, 2.1-fold lower after 8 months (Fig. 1D-F), and fractional excretions were 1.6-, 4.4-, and 1.8- fold lower after 6 months and 1.7-, 1.4-, 1.7-fold lower after 8 months in DKD (Fig. 1G-I), respectively. Other PBUTS, i.e., PCG, PCS and, IAA were not significantly affected (Suppl. Figure 2).

Fig. 1.

PBUTs plasma concentration, surrogate clearance and fractional excretion in DKD mice and healthy controls. Data are presented as mean ± SD. The non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test or parametric unpaired t-test was performed for statistical analysis based on the data normality determined by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05. DKD: diabetic kidney disease; IS: indoxyl sulfate; HA: hippuric acid; KA: kynurenic acid.

PBUTs correlate better with tubular atrophy than commonly used filtration markers

Next, we evaluated whether the PBUT parameters correlate with the histopathology. All animals were included in the analysis (i.e., controls and DKD mice, sacrificed at 6 and 8 months). Plasma concentration of IS (r = 0.49; P < 0.001), HA (r = 0.68; P < 0.001) and KA (r = 0.40; P = 0.002) positively and surrogate clearance of IS (r = -0.44; P = 0.001), HA (r = -0.37; P = 0.007) and KA (r = -0.44; P = 0.11) negatively correlated with TAS (Suppl. Figure 3). The mice were then grouped based on their TAS: 0 to 0.1 (n = 7), 0 to 0.3 (n = 21), 0 to 0.5 (n = 27), 0 to 1.0 (n = 32), 0 to 1.3 (37), 0 to 1.5 (n = 48), 0 to 2.0 (n = 55) to evaluate the relative sensitivity among commonly used biomarkers and PBUTs to various grades of tubular atrophy. Plasma HA correlated with tubular atrophy starting already at TAS ≤ 0.5 and became stronger with higher TAS. For plasma IS and KA, the correlation became significant at TAS ≤ 1.0, for HA surrogate clearance at TAS ≤ 1.3 and for albuminuria, IS and KA surrogate clearance at TAS ≤ 1.5 (Table 2). Of note, the plasma concentration and surrogate clearance of IS and KA correlated with TAS already at a very low level (TAS ≤ 0.1) but not significantly due to the small sample size (Table 2). In comparison, plasma Cys C, plasma Cr and Cr clearance did not correlate with TAS at any level. PBUTs with non-significant changes in plasma concentration, surrogate clearance and fractional excretion did not correlate with tubular atrophy (Suppl. Table 1).

Table 2.

Correlation of PBUTs and commonly used markers with tubular atrophy scores.

| Markers | Tubular atrophy scores | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAS ≤ 2.0 | TAS ≤ 1.5 | TAS ≤ 1.3 | TAS ≤ 1.0 | TAS ≤ 0.5 | TAS ≤ 0.3 | TAS ≤ 0.1 | |

| Plasma hippuric acid | 0.71*** | 0.74*** | 0.67*** | 0.55** | 0.45* | 0.33 | 0.06 |

| Plasma indoxyl sulfate | 0.54*** | 0.58*** | 0.53*** | 0.37* | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.63 |

| Plasma kynurenic acid | 0.46*** | 0.52*** | 0.37* | 0.38* | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.71 |

| Hippuric acid surrogate clearance | − 0.47*** | − 0.54*** | − 0.40* | − 0.27 | − 0.16 | − 0.15 | − 0.08 |

| Kynurenic acid surrogate clearance | − 0.48*** | − 0.54*** | − 0.32 | − 0.37 | − 0.19 | − 0.17 | − 0.70 |

| Indoxyl sulfate surrogate clearance | − 0.47*** | − 0.53*** | − 0.26 | − 0.16 | − 0.22 | − 0.47* | − 0.91 |

| Albuminuria | 0.48*** | 0.48** | 0.19 | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.37 |

| Plasma creatinine | 0.14 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.13 | − 0.04 | − 0.07 | 0.20 |

| Plasma cystatin C | − 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.00 | − 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.16 | − 0.34 |

| Creatinine clearance | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.16 | − 0.02 | 0.01 | − 0.03 |

Analyses include both control and diabetic animals, sacrificed at 6 and 8 months. Non-parametric Spearman correlation was performed and the data are presented as Spearman rank, where ‘- ‘ indicates negative correlation. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05. PBUTs: protein-bound uremic toxins; sur.cl: surrogate clearance; cl: clearance.

Significant values are in [bold].

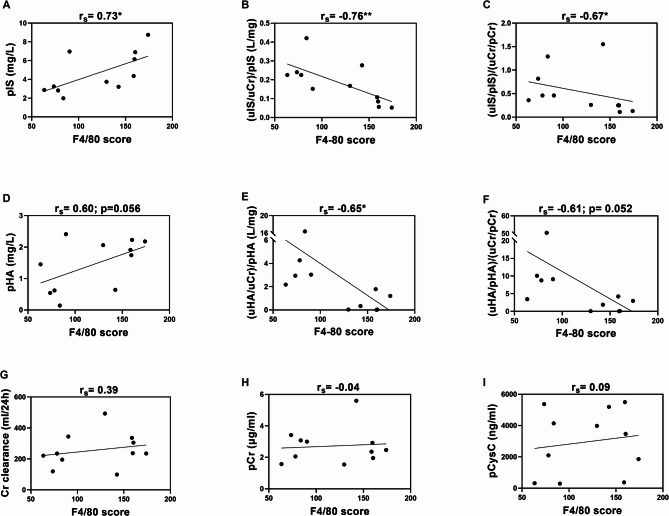

PBUTs correlate with interstitial inflammation in the kidney

Renal interstitial inflammatory cell infiltration, one of the common features in DKD27,28, was evident by an increase of f4/80 positive macrophages after 6 months. Of note, 8 months data were not available. Diabetic mice showed a 1.9-fold increase in f4/80 positive cells in the kidney (141.9 ± 10 vs. 75.5 ± 3.4, P < 0.01) per high power field compared to control mice. This f4/80 score, representing interstitial macrophage infiltration, positively correlated with the plasma concentration and negatively with surrogate clearance and fractional excretion of IS and HA, but not with KA and the conventional markers (Fig. 2, Suppl. Table 2). PBUTs with non-significant changes in plasma concentration, surrogate clearance and fractional excretion did not correlate with tubular atrophy (Suppl. Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Correlation of f4/80 score with plasma concentration, clearance and fractional excretion of IS (A–C), HA (D–F), Cr clearance (G), plasma Cr (H), plasma Cys C (I). Non-parametric spearman correlation was performed, and the data are presented as spearman rank, where ‘-’ indicates negative correlation. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05. IS: indoxyl sulfate; HA: hippuric acid; KA: kynurenic acid; Cr: creatinine; Cys C: cystatin C; uCr: Urinary creatinine.

PBUTs correlate better with tubular damage markers than commonly used filtration markers

Plasma and urinary NGAL have been demonstrated as early markers for acute kidney injury (AKI)29–32 and in particular for tubular damage33. Systematic review and meta-analyses suggested both serum and urinary NGAL as sensitive biomarkers of kidney disease in DKD patients, with pooled sensitivity and specificity ranging from 0.90 to 0.9814,34. Cys C is filtered by the glomerulus but catabolized completely after uptake by proximal tubule cells. Impaired reabsorption by the tubules may lead to its increased urinary excretion in DKD35–37 Kim-1 is a transmembrane tubular protein only detectable in acute events of kidney injury38, and studies indicated that urinary Kim-1 reflects lesions of proximal tubule at early stage of DKD39.

Plasma PBUT concentrations correlated better with tubular injury (plasma and urinary NGAL) and function (urinary Cys C) markers than the markers for glomerular filtration (plasma Cr and Cys C) and damage (albuminuria) both at 6 and 8 months, except for KA with plasma NGAL after 6 months and IS with urinary Cys C after 8 months (Table 3, Suppl. Figures 4–11). Similarly, PBUTs surrogate clearance and fractional PBUT excretion showed a significant negative correlation with the tubular markers at 6 months. However, after 8 months the correlation between surrogate clearance and fractional excretion of IS and HA and tubular markers was lost. PBUTs with non-significant change in plasma concentration, clearance and fractional excretion did not show notable correlation with tubular markers, except for surrogate clearance of PCG, PCS and IAA with plasma NGAL after 6 months (Suppl. Table 1). Plasma and urinary Kim-1 were undetectable in our samples; however, the expression of Kim-1 gene (Havcr1) in kidney tissues was significantly higher in diabetic mice after 8 months (Table 1) but did not correlate with any of the markers evaluated here.

Table 3.

Correlation of PBUTs and commonly used filtration markers with tubular markers.

| Markers | Plasma NGAL | uNGAL/uCr | uCysC/uCr | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months | 8 months | 6 months | 8 months | 6 months | 8 months | |

| Plasma indoxyl sulfate | 0.50** | 0.44** | 0.50* | 0.36* | 0.54** | 0.32 |

| Plasma hippuric acid | 0.54** | 0.65*** | 0.63** | 0.66*** | 0.74*** | 0.45* |

| Plasma kynurenic acid | 0.23 | 0.58*** | 0.43* | 0.48** | 0.53* | 0.40* |

| Indoxyl sulfate surrogate clearance | − 0.45* | − 0.09 | − 0.64** | − 0.12 | − 0.45* | − 0.28 |

| Hippuric acid surrogate clearance | − 0.58** | − 0.30 | − 0.68*** | − 0.23 | − 0.71*** | − 0.14 |

| Kynurenic acid surrogate clearance | − 0.40* | − 0.50** | − 0.44* | − 0.56** | − 0.47* | − 0.36* |

| Indoxyl sulfate fractional excretion | − 0.57** | 0.06 | − 0.48* | 0.09 | − 0.38 | − 0.14 |

| Hippuric acid fractional excretion | − 0.48* | − 0.13 | − 0.58** | 0.02 | − 0.59** | − 0.00 |

| Kynurenic acid fractional excretion | − 0.39 | − 0.40* | − 0.36 | − 0.41* | − 0.41 | − 0.23 |

| Plasma creatinine | 0.23 | − 0.05 | 0.31 | 0.24 | 0.05 | 0.17 |

| Creatinine clearance | 0.31 | − 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.45* | 0.40 | 0.10 |

| Plasma Cystatin C | 0.33 | − 0.11 | 0.41 | − 0.14 | 0.05 | − 0.14 |

| Albuminuria | 0.39 | − 0.05 | 0.27 | 0.51** | 0.36 | 0.52** |

Non-parametric Spearman correlation was performed, and the data are presented as Spearman rank, where ‘-’ indicates negative correlation. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05. PBUTs: protein-bound uremic toxins; cl: clearance; NGAL: neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; Cr: creatinine; Cys C: cystatin C; uCr: Urinary creatinine.

Significant values are in [bold].

Clinical study

Patient characteristics

Baseline characteristics and medications (including ACEi and ARB) of the study population (N = 33) are summarized in Table 4 and Suppl. Table 3, respectively. The patients included in this study were at an early stage of kidney function decline with an eGFR between 50–90 ml/min/1.73 m2 in the majority of patients (Suppl. Figure 12). Among PBUTs, the clearance (mean ± SD) ranged from 6.1 ± 6.3 ml/min for IAA to 377.0 ± 271.5 ml/min for HA (Table 5).

Table 4.

Patient demographic and characteristics.

| Characteristic | Total (N = 33) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61 ± 9 |

| Sex (female/male) (n) | 8/25 |

| Caucasian (n, %) | 30 (91) |

| Body weight (kg) | 96 ± 22 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 31 ± 5.5 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 142 ± 13 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 78 ± 6.7 |

| Smoking status (n, %) | 9 (27.3) |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 10 ± 7 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 59 ± 15 |

| Cardiovascular disease history (n, %)a | 10 ± 30 |

| Estimated GFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 72 ± 19 |

| Serum creatinine (µmol/L) | 91.3 ± 20.5 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 6.8 ± 2.2 |

| Plasma cystatin C (ng/ml) | 325 ± 8 |

| UAER (mg/24 h)* | 613 (208–1102) |

| UACR (mg/mmol)* | 51.1 (22.2–89.8) |

Data are given as mean ± SD and *median (25th to 75th percentile); aCardiovascular disease history defined as history of coronary artery disease or peripheral vascular disease; UAER: urinary albumin excretion rate; UACR: urinary albumin creatinine ratio.

Table 5.

Plasma concentration and clearance of PBUTs.

| Toxins | Plasma concentration (ng/ml) | Clearance (ml/min) |

|---|---|---|

| Indoxyl sulfate | 2860.3 ± 1924.8 | 46.2 ± 35.3 |

| Hippuric acid | 1870.3 ± 1154.4 | 377.0 ± 271.5 |

| Kynurenic acid | 12.0 ± 4.4 | 133.6 ± 53.8 |

| p-cresyl glucuronide | 78.4 ± 75.5 | 275.8 ± 221.9 |

| p-cresyl sulfate | 9715.8 ± 6957.3 | 12.8 ± 5.8 |

| Indole-3-acetic acid | 1003.7 ± 1028.5 | 6.1 ± 6.3 |

Data are given as mean ± SD.

PBUT clearance correlates better with tubular damage markers than commonly used filtration markers

Table 6 depicts comparative ranks of Pearson correlation of log-transformed PBUT clearance and commonly used biomarkers with urinary markers of kidney tubular injury (urinary NGAL and KIM-1) and function (urinary Cys C). The clearance of IS, HA, KA and PCS negatively correlated with urinary NGAL and KIM-1, whereas conventional markers, including eGFR and UAER, did not show any correlation except for creatinine clearance with urinary NGAL. Urinary Cys C only showed a negative correlation with IAA clearance (Table 6). However, in contrast to our preclinical findings, plasma PBUT concentrations did not correlate with tubular injury markers.

Table 6.

Comparative rank of (Pearson) correlation of (log-transformed) PBUT clearance and commonly used markers with kidney tubular injury markers.

| Markers | Correlation with uNGAL/uCr | Correlation with uKIM-1/uCr |

Correlation with uCysC/uCr |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indoxyl sulfate clearance | − 0.51** | − 0.48** | 0.05 |

| Hippuric acid clearance | − 0.54** | − 0.49** | − 0.15 |

| Kynurenic acid clearance | − 0.52** | − 0.51** | − 0.08 |

| p-cresyl sulfate clearance | − 0.56** | − 0.45* | − 0.32 |

| p-cresyl glucuronide clearance | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.24 |

| Indole-3-acetic acid clearance | − 0.33 | − 0.27 | − 0.44* |

| Serum creatinine | − 0.06 | − 0.11 | 0.16 |

| Urea | − 0.23 | − 0.32 | − 0.04 |

| Plasma cystatin C | − 0.11 | − 0.24 | 0.01 |

| eGFR | − 0.11 | − 0.00 | − 0.15 |

| UAER | − 0.13 | − 0.18 | 0.34 |

| Creatinine clearance | − 0.41* | − 0.33 | − 0.31 |

cl, clearance; uCr, urine creatinine; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; KIM-1, kidney injury molecule-1; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; UAER, urinary albumin excretion rate.

Significant values are in [bold].

Association of PBUT clearance with tubular damage markers

Lower clearances of IS, HA, KA and PCS were associated with increased concentration of urinary NGAL and KIM-1 in the unadjusted model (Model 1), with an estimated decrease in (log-transformed) clearance of 6.87–12.45 ml/min and 0.45–0.89 ml/min for every µg/mmol Cr increase in urinary NGAL and KIM-1, respectively (Tables 7 and 8). These associations remained significant after adjustment for eGFR (Model 2) (Tables 7 and 8). Further adjustment for age, sex and race (Model 3) resulted in a slight attenuation of the estimates, however, the clearance of IS, HA and PCS remained significantly associated with urinary NGAL and KIM-1. In Model 4, after adjustment with all available risk factors, lower clearance of PCS remained significantly associated with urinary NGAL (Table 7). In contrast, UAER and creatinine clearance showed no significant association with urinary KIM-1 and NGAL, except for creatinine clearance with urinary NGAL in model 1 and 2, while their estimates were very low (Tables 7 and 8). Next, we tested these associations with an average clearance of 4 PBUTs: IS, HA, KA and PCS, which was significantly associated with urinary NGAL and KIM-1 in all 4 models, with an estimated decrease in (log-transformed) clearance of 8.03–12.99 ml/min and 0.56–0.90 ml/min for every µg/mmol Cr increase in urinary NGAL and KIM-1, respectively (Table 9). The sensitivity of these associations was further evaluated in a subgroup of patients stratified for eGFR. The average clearance of IS, HA, KA and PCS was significantly associated with urinary NGAL and KIM-1 in all 4 models with high eGFR subgroup (> 70 mL/min/1.73 m2) (Suppl. Table 4).

Table 7.

Association of PBUT clearance (log-transformed) with (creatinine normalized) urinary NGAL (uNGAL/uCr) in multiple regression model.

| Biomarker | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (Standard error) | P value | Estimate (Standard error) | P value | Estimate (Standard error) | P value | Estimate (Standard error) | P value | |

| Indoxyl sulfate clearance | − 7.53 (2.34) | 0.004 | − 7.57 (2.49) | 0.005 | − 5.62 (2.22) | 0.018 | − 4.75 (2.73) | 0.096 |

| Hippuric acid clearance | − 6.87 (2.00) | 0.002 | − 7.01 (2.11) | 0.003 | − 5.04 (1.83) | 0.011 | − 3.86 (2.12) | 0.083 |

| Kynurenic acid clearance | − 12.45 (3.83) | 0.003 | − 12.40 (3.88) | 0.003 | − 7.41 (3.75) | 0.059 | − 4.03 (5.04) | 0.433 |

| p-cresyl sulfate clearance | − 11.75 (3.23) | 0.001 | − 11.78 (3.37) | 0.002 | − 9.33 (2.77) | 0.002 | − 8.38 (3.47) | 0.025 |

| p-cresyl glucuronide clearance | 0.13 (1.66) | 0.940 | 0.12 (1.68) | 0.943 | 0.12 (1.42) | 0.932 | 1.39 (1.52) | 0.373 |

| Indole-3-acetic acid clearance | − 2.91 (1.55) | 0.070 | − 2.91 (1.66) | 0.090 | − 2.71 (1.27) | 0.043 | − 2.38 (1.37) | 0.098 |

| UAER |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.483 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.343 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.223 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.221 |

| Creatinine clearance | − 0.01 (0.01) | 0.021 | − 0.01 (0.01) | 0.023 | − 0.01 (0.00) | 0.054 | − 0.01 (0.01) | 0.127 |

#UAER was not included as a confounder.

cl, clearance; UAER, urinary albumin excretion rate; Cr, Creatinine; uCr, urine creatinine; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; Model 1: Unadjusted; Model 2: Model 1 + eGFR; Model 3: Model 2 + age, sex and race; Model 4: Model 3 + UAER, smoking status, BMI and blood pressure.

Significant values are in [bold].

Table 8.

Association of PBUT clearance (log-transformed) with (creatinine normalized) urinary KIM-1 (uKIM-1/uCr) in multiple linear regression models.

| Biomarker | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (Standard error) | P value | Estimate (Standard error) | P value | Estimate (Standard error) | P value | Estimate (Standard error) | P value | |

| Indoxyl sulfate clearance | − 0.52 (0.17) | 0.006 | − 0.54 (0.18) | 0.006 | − 0.41 (0.16) | 0.021 | − 0.36 (0.20) | 0.085 |

| Hippuric acid clearance | − 0.45 (0.15) | 0.006 | − 0.48 (0.16) | 0.005 | − 0.35 (0.14) | 0.018 | − 0.26 (0.15) | 0.103 |

| Kynurenic acid clearance | − 0.89 (0.28) | 0.003 | − 0.89 (0.28) | 0.004 | − 0.51 (0.28) | 0.086 | − 0.25 (0.37) | 0.505 |

| p-cresyl sulfate clearance | − 0.68 (0.25) | 0.011 | − 0.71 (0.26) | 0.011 | − 0.52 (0.23) | 0.030 | − 0.37 (0.27) | 0.194 |

| p-cresyl glucuronide clearance | 0.03 (0.12) | 0.784 | 0.03 (0.12) | 0.788 | 0.01 (0.11) | 0.900 | 0.10 (0.11) | 0.378 |

| Indole-3-acetic acid clearance | − 0.17 (0.11) | 0.144 | − 0.19 (0.12) | 0.133 | − 0.17 (0.10) | 0.092 | − 0.15 (0.10) | 0.144 |

| UAER | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.314 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.291 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.301 | 0.00 (0.00)# | 0.270 |

| Creatinine clearance | − 0.00 (0.00) | 0.061 | − 0.00 (0.00) | 0.066 | − 0.00 (0.00) | 0.126 | − 0.00 (0.00) | 0.233 |

#UAER was not included as a confounder.

cl, clearance; UAER, urinary albumin excretion rate; Cr, Creatinine; uCr, urine creatinine; KIM-1, kidney injury molecule-1; Model 1: Unadjusted; Model 2: Model 1 + eGFR; Model 3: Model 2 + age, sex and race; Model 4: Model 3 + UAER, smoking status, BMI and blood pressure.

Significant values are in [bold].

Table 9.

The association of average clearance of 4 PBUTs with urinary tubular injury markers in multiple linear regression models.

| Biomarker | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (Standard error) | P value | Estimate (Standard error) | P value | Estimate (Standard error) | P value | Estimate (Standard error) | P value | |

| Association of (log-transformed) average clearance of 4 PBUTs (IS, HA, KA and PCS) with uNGAL/uCr | ||||||||

| Average PBUT clearance |

− 12.48 (2.63) |

< 0.001 | − 12.99 (2.77) | < 0.001 | − 9.10 (2.68) | 0.002 | − 8.03 (3.59) | 0.036 |

| Association of (log-transformed) average clearance of 4 PBUTs (IS, HA, KA and PCS) with uKIM1/uCr | ||||||||

| Average PBUT clearance | − 0.83 (0.20) | < 0.001 | − 0.90 (0.21) | < 0.001 | − 0.65 (0.20) | 0.004 | − 0.56 (0.26) | 0.046 |

uCr, urine creatinine; IS, indoxyl sulfate; HA, hippuric acid; KA, kynurenic acid; PCS, p-cresyl sulfate; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; KIM-1, kidney injury molecule-1; Model 1: Unadjusted; Model 2: Model 1 + eGFR; Model 3: Model 2 + age, sex and race; Model 4: Model 3 + UAER, smoking status, BMI and blood pressure.

Similar to Pearson correlations, only IAA clearance was associated with urinary Cys C after adjustment with eGFR and this association remained significant in all models (Suppl. Table 5).

Contrary to the preclinical findings (Table 3), but like the Pearson correlations (Table 6), the plasma concentration of PBUTs were not associated with kidney tubular injury markers (Suppl. Table 6).

Discussion

In the present study, we hypothesized that PBUTs plasma concentration and clearance may be sensitive tubular function markers in DKD. This was tested in a long-term streptozotocin-induced DKD mouse model and in type 2 diabetic patients. Major finding of our study is that, in both experimental and human DKD, reduced clearance of PBUTs with high OAT1 affinity, i.e., IS, HA and KA, and PCS in human DKD, were related to tubular injury, and this remained significant after adjustment for glomerular filtration (using fractional PBUT excretion in experimental DKD and multiple regression in human DKD). The relationship was present even for mild tubular atrophy in experimental DKD and mild human DKD (eGFR > 70 mL/min/1.73 m2), suggesting that PBUT clearance is a sensitive marker for tubular function.

Although DKD is traditionally viewed primarily as a glomerular disease, tubulointerstitial injury is a major feature of DKD with important prognostic significance9,40,41. Tubular injury was shown to be an early event in the pathogenesis of DKD, which may precede albuminuria40. In diabetic kidneys, increased SGLT2-mediated glucose uptake in proximal tubular cells induces oxidative stress and inflammation9,40–42 leading to tubulointerstitial histological changes, including hypertrophy, thickening of the tubular basement membrane and interstitial inflammation, subsequently contributing to renal structural modifications such as tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis. These alterations correlate with kidney function decline and ultimately play a significant role in the development and progression of DKD11,43–46. Early detection of incipient DKD is important as timely initiation of adequate treatment may slow progression and improve patient outcomes. This study suggests that PBUT clearance may play a role in this.

PBUTs are dietary metabolites generated by gut microbial metabolism and eliminated primarily by active tubular secretion in the renal proximal tubule via influx transporters at the basolateral side, such as OAT1 and 3, and efflux transporters at the apical side, such as MRP4 and BCRP16,47. Numerous studies conducted with various (animal and human) models demonstrated the uptake of PBUTs by these transporters, with IS, HA and KA having the highest affinities48–51. In tubular dysfunction, particularly impairment of the secretory mechanisms in the proximal tubule, this secretion process is compromised. As a result, PBUTs cannot be effectively transported into the urine and, consequently, accumulate in plasma15,16. Previous studies emphasized the importance of plasma concentration and clearance of PBUTs in the assessment of the secretory function of kidneys12,51. However, PBUTs as indicators of secretory function of kidney tubules has not yet been investigated in DKD. Our data suggest that PBUT clearance reflects renal tubular dysfunction in DKD and may be used for early detection.

In experimental DKD plasma PBUT concentration was also related to tubular injury but in human DKD this was not the case. The PBUTs studied here are tryptophan and phenol derivatives, generated endogenously by gut microbial metabolism of dietary proteins. Their plasma concentrations may, therefore, be influenced by various factors, including variability in protein intake, colonic microbial metabolism and hepatic metabolism process52–54. In uremic condition, the composition and function of gut microbiome may change, leading to inter-individual and inter-species variation in colonic metabolism of dietary proteins and subsequent metabolites53. Due to the experimental setup, these factors are comparable among the mice thus variation in plasma PBUT is primarily determined by tubular function, while in humans these factors may have caused large inter-individual variability in plasma PBUTs. In principle, fractional excretions should represent renal tubular function more accurately than clearance. However, the correlation strengths of fractional excretions in our preclinical data were weaker than those of clearances, possibly due to a small proportion of creatinine that is excreted via tubular secretion which may attenuate the association (when both denominator and numerator of the ratio partly represent tubular function). However, this was not found in diabetic patients where fractional excretion was not affected by creatinine secretion (Suppl. Table 7).

On the other hand, the efficiency of PBUTs in assessing tubular function might be affected by, for example, saturation of or competition for in- and efflux transporters, especially in DKD patients on multiple drugs that excrete via tubular secretion55,56.

Tubular injury (such as NGAL, KIM-1) and function (such as Cys C) markers, showed promising efficacy in early detection of DKD in various preclinical and clinical studies5,39,57–59. In our study, PBUT parameters demonstrated better relations with these markers than conventional markers such as creatinine clearance and albuminuria. This is in accordance with kidney physiology since PBUTs are primarily excreted at the tubular level while tubular secretion only represents a minor fraction of creatinine clearance, and both glomerular and tubular injury may cause albuminuria. The independent associations of PBUT clearance with urinary NGAL and KIM-1 suggest that PBUT clearance may -like these markers- be used for early DKD detection. However, while NGAL and KIM1 are induced by injured proximal epithelial cells, PBUT clearance reflects function of the secretory transport system of these cells. In our study, we were unable to assess transporter expression due to insufficient sample material. Literature suggested that these transporters are downregulated under diabetic conditions, likely as a consequence of hyperglycemia induced oxidative stress and impaired insulin signaling60–62. Notably, such downregulation may theoretically precede the increase in levels of tubular injury markers. Remarkably, clearance of IS, HA and KA was not associated with urinary Cys C reflecting dysfunction of the cubilin and megalin mediated endocytic uptake of proteins in proximal tubular cells63,64.

Also for prediction of progression of DKD, urinary NGAL and KIM-1 appear to be the most promising among the available markers, although some longitudinal studies have reported a suboptimal performance of KIM-1 in predicting renal failure in long-term diabetes5,57. In a prospective cohort study of 3416 CKD patients PBUT clearance, but not PBUT plasma concentration, was associated with CKD progression and all-cause mortality23. A case–control study in DKD patients showed an association between plasma concentration of pCS, but not IS and HA, and the risk of kidney failure22. Long term prospective studies should elucidate whether PBUT clearance also has prognostic significance in DKD.

While our findings support PBUTs as potential biomarkers of early DKD, our study has important limitations. Firstly, since this was a retrospective study, we did not have all samples available for statistical analyses and for investigating the expression of renal transporters involved in PBUT clearance. Secondly, diabetes was induced in mice by streptozotocin, which may have contributed to damage to tubular epithelial cells via activation of p53 signaling in acute phases65, however, this was unexpected to influence tubular damage after 6 months. Thirdly, we could not use 24 h urine excretion of PBUTs to calculate clearance in mice due to a suspected systemic error during urine collection from the metabolic cages. Finally, the cohort of diabetes patients was rather small, and we could not evaluate the association of PBUT clearance with histology score of tubular atrophy from patient’s biopsies or with the gold standard measurements of tubular function, such as the clearance of para-amino hippuric acid.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that plasma concentration and clearance of IS, HA and KA correlate with histological scores of kidney tubular damage and with available tubular markers, stronger than with conventional markers creatinine clearance and albuminuria in a long-term experimental mouse DKD model. In a cohort of type 2 diabetic patients, clearance of IS, HA, and PCS associated with kidney tubular injury markers independent of eGFR and other relevant confounders. Together, these findings suggest that the clearance of IS, HA, KA and PCS may serve as biomarkers for tubular dysfunction in DKD. The evaluation of tubular function in addition to the filtration function could facilitate detecting site-specific injury and may help in early detection of DKD. Future studies should focus on validation in large cohorts of DKD patients.

Materials and methods

Reagents

IS, KA, HA, IAA and acetic acid (HAc; LC–MS grade) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). PCS and PCG were purchased from AlsaChim (Illkirch-Graffenstaden, France). Water (LC–MS grade), acetonitrile (ACN; HPLC-S grade) and methanol (HPLC grade) were obtained from Biosolve (Valkenswaard, The Netherlands). Formic acid (analytical grade) was obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Ultrapure water was produced by a Milli-Q® Advantage A10 Water Purification Systems (Merck, The Netherlands). The isotopically labeled internal standards d5-KA and d5-IAA were purchased from CDN Isotopes (Pointe-Claire, Quebec, Canada), 13C6-IS and d5-HA and were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA, USA), d7-PCS (potassium salt) was purchased from IsoSciences (Ambler, PA, USA) and d7-PCG was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (North York, Ontario, Canada).

Diabetic nephropathy mouse model

We used a long-term streptozotocin (STZ)-induced murine DKD model previously documented by Falke et al.25. Briefly, diabetes mellitus was induced in C57BL6/J mice by a single intraperitoneal injection of 200 mg/kg STZ, concentration 30 mg/ml, dissolved in 100 mM sodium citrate buffer, pH 4.5 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The buffer alone was used for the control animals. 24 h urine was collected by metabolic cages. Mice were sacrificed 6 and 8 months post-STZ administration using a KXA injection (an anesthetic combination of ketamine, xylazine, and acepromazine), and plasma and kidney tissues were harvested. All experiments were approved of the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of the University of Utrecht (DEC number 2009.II.11.129), and performed in accordance with their guidelines and regulations. This study used samples (stored at − 80 °C) based on availability (6 months: 15 control vs. 16 DKD; 8 months: 19 control vs. 23 DKD). The methods for tubular atrophy (TA) scoring and macrophage infiltration were documented previously25. The study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Tubular atrophy and F4/80 scoring

Renal tissues were paraffin-embedded and sectioned at a thickness of 3 μm. Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining was performed to evaluate tissue morphology. Tubular atrophy was assessed independently by two experienced observers who were blinded to the slide identities. The scoring was done in 10 randomly selected cortical fields at × 100 magnification using a semiquantitative scale. The average score across the ten fields was used for subsequent statistical analysis. Images were captured using a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope equipped with a Nikon DXM1200 digital camera and Nikon ACT-1 software (version 2.70; Nikon Netherlands, Lijnden, the Netherlands).

Macrophage infiltration was assessed in frozen kidney sections. Sections were fixed in acetone, blocked, and incubated with a rat anti-mouse F4/80 antibody (Serotec Benelux, Oxford, UK) to detect macrophage-specific antigen. Subsequently, sections were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated rabbit anti-rat secondary antibody (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), followed by goat anti-rabbit Powervision-HRP (Klinipath, Duiven, The Netherlands). Detection was performed using Nova Red substrate (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), and sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. F4/80-positive cells were counted per high-power field (field area 0.245 mm2) in a blinded manner. Only cells showing F4/80 positivity in both the nucleus and cytoplasm were considered truly positive.

Type 2 diabetic patient cohort

The samples of type 2 diabetic patients were obtained from a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over clinical trial, which was registered in the Netherlands Trial Register (NTR 4439), was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Groningen, the Netherlands (METc 2014/111), and was conducted in accordance with their guidelines and regulations, the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines66. All participants (N = 33) provided written informed consent before any study procedure started. This clinical trial involved 3 consecutive cross-over treatment periods of 6 weeks with washout periods of 6 weeks in between. The current study utilized the baseline samples from this trial when patients were unaffected by the test drugs.

PBUTs quantification in plasma and urine by LC–MS/MS

Equipment and LC–MS/MS condition

An Accela LC system (quaternary pump and autosampler), coupled to a TSQ Quantum Ultra triple quadrupole mass spectrometer with heated electrospray ionization (ESI; Thermo Fischer Scientific (San Jose, CA, USA)), was used for this study. The software for controlling, data recording and processing (Xcalibur version 2.07) was supplied by Thermo Fischer Scientific (San Jose, CA, USA). A Waters ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.8 µm particles) combined with an ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 VanGuard pre-column (5 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.8 µm particles) was kept at a temperature of 40 °C. Mixed isocratic and gradient elution at a flow rate of 0.45 mL/min was applied for analyte separation. In the mobile phase, solvent A consisted of 0.2% (v/v) HAc, and solvent B was ACN. The final method was an initial isocratic composition of 5% B held for 1 min, followed by a linear increase to 15% B for the next 1 min, and to 20% B in another 1 min. Then, B was increased linearly to 80% over the next minute to flush the column. To re-equilibrate, B was reduced back to the initial isocratic composition of 5% and was held for 2 min.

Sample pre-treatment and quantification

Samples were pretreated prior to LC–MS/MS analysis. The plasma samples were diluted two times, and urine samples ten (mice) or four (patients) times with ultrapure water. Then, 20-µL of (diluted) plasma or urine was pipetted into a 1.5-mL Eppendorf tube. Ultra-pure water was used as a surrogate matrix for calibration curve and quality control samples. Subsequently, 30 µL of cold (4 °C) ACN with stable-isotope internal standards were added. Samples were vortexed for 5 min on a plate vortexer and centrifuged for 5 min at 4000 g. A 35-µL sample of the supernatant was then collected in a 1-ml round-bottom well of a polypropylene 96-deep well plate and diluted with 200 µl of ultra-pure water. Finally, the plate was gently shaken before placing in the autosampler for analysis.

The calibration was obtained by eight different concentrations of standard for each analyte using linear regression analysis. The peak area was normalized with the respective labeled internal standards for each analyte before extracting the quantified values using the calibration curve. The reliability of quantification was further ensured by four quality control samples with different concentrations in every measurement. We then measured the total plasma concentration and urinary concentration of PBUTs.

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis and Real-Time qPCR

Total RNA from homogenized mouse kidneys was isolated by the following method. After homogenizing the kidney tissue, 5 min of incubation was allowed to ensure complete dissociation of nucleoproteins complex. Then 200 µl of chloroform per 1 mL of homogenate was added and centrifuged for 15 min at 12,000 g at 4 °C following a gentle mix by pipetting and 2–3 min of incubation. The colorless aqueous layer of the supernatant containing the RNA was then treated with 500 µl of isopropanol and incubated for 10 min after a gentle mix before the next centrifugation for 10 min at 12,000 g at 4 °C. After discarding the supernatant, the precipitated total RNA was resuspended in 1 mL of 75% ethanol ((v/v) with water) before a brief vortex and centrifuge for 5 min at 7500 g at 4 °C. Then the obtained pellet was air-dried for 5–10 min and resuspended in 30µL of RNase-free water, followed by incubation in a heat block set at 55–60 °C for 15 min before quantification using the NanoDrop® ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, DE, USA).

The synthesis of cDNA was performed using 1000 ng of total mRNA per sample and using the iScriptTM Reverse Transcription Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) and T100™ Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Subsequently, Real-Time PCR was performed using the iQ SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories) as indicated in the manufacturer’s protocol and by means of CFX96TM Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The data were analyzed using Bio-Rad CFX ManagerTM Software version 3.1 (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and expressed as relative gene expression. β-actin was used as housekeeping gene for normalization. Specific sense and anti-sense primers for β-actin (forward: TAAGGCCAACCGTGAAAAG; reverse: ACCAGAGGCATACAGGGACA), and Kim-1 (forward: ATGAATCAGATTCAAGTCTTC; reverse: TCTGGTTTGTGAGTCCATGTG) were synthesized by Biolegio (Nijmegen, The Netherlands).

Biochemical analyses

Blood glucose level in mice was measured (Medisense Precision Xtra; Abbott, Bedford, IN) 3 days after the intraperitoneal STZ injection to determine hyperglycemia. After 5 days, the condition of diabetic mice was stabilized by slow-release insulin pellets (Linshin, Scarborough, Canada). Creatinine concentrations were determined by enzymatic assays (J2L Elitech, Labarthe Inard, France).

The concentration of NGAL, KIM-1 and cystatin C (Cys C) in plasma and urine samples were determined by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) using Duoset kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, USA) for humans or mice. Mouse plasma samples were diluted 250 and 500 times, and mouse urine samples 1000 and 500 times for NGAL and Cys C measurement, respectively. The urine samples from diabetic patients were diluted 20, 50 and 50 times for measuring KIM-1, NGAL and Cys C, respectively, before following the manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance was determined using the Microplate Absorbance Reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) set to 450 nm. Each sample was measured in duplicates and quantification was done using Microplate Manager software (version 6.0, Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Calculations

For the mice, we used the urinary PBUT/ creatinine ratio normalized for plasma PBUT concentration (Eq. 1) as a surrogate for PBUT clearance (instead of the 24h PBUT clearance calculated with the 24h urine volume) since we suspected a systematic error in the 24h urine collection with relatively more loss of urine for the non-diabetic mice than for the polyuric (Table 1) diabetic mice. This was based on the observation that 24h creatinine excretion (calculated with 24 h urine volume) for diabetic mice was 50% higher than that of nondiabetic mice, i.e., 701 ± 60 vs. 418 ± 39 µg/d (P = 0.001) after 6 months and 932 ± 343 vs. 469 ± 48 µg/d (P = 0.016) after 8 months, respectively. In theory it is very unlikely that the 24h creatinine excretion reflecting muscle mass is significantly higher in diabetic mice than in healthy controls. We therefore suspect that a higher fraction of the 24h urine was left in the metabolic cages for the healthy controls than for the polyuric diabetic mice, causing this systematic error. Accordingly, urinary tubular injury markers were expressed as creatinine-normalized and not as absolute amounts excreted in 24h. The fractional excretion of PBUTs in mice was calculated by Eq. 2. The clearance of PBUTs for diabetic patients was calculated from 24 h urine samples in a standard manner, as stated in Eq. 3. The MDRD equation was used to calculate eGFR from serum creatinine. The fractional excretion of PBUTs in patients was calculated by normalizing total clearance with eGFR (not adjusted for body surface area), as indicated in Eq. 4 instead of Eq. 2, to minimize the influence of secretion fraction of creatinine. Urinary tubular markers were normalized using creatinine concentration in urine, consistent with the approach used in the preclinical study.

|

1 |

|

2 |

|

3 |

|

4 |

where  and

and  represent the urine and plasma concentration of a specific PBUT;

represent the urine and plasma concentration of a specific PBUT;  and

and  represent the urine and plasma concentration of creatinine, respectively. Urine concentrations were measured in the 24h urine.

represent the urine and plasma concentration of creatinine, respectively. Urine concentrations were measured in the 24h urine.

Statistical analyses

The statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software for Mac, version 9 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and R studio 2021.09.1 (Build 372© 2009–2021 RStudio, PBC). Data are expressed as mean ± SD, mean (SD), and median (IQR), as appropriate. In the preclinical data, differences between groups were analyzed by nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test based on the data normality, determined by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Spearman correlation coefficients were used to test correlations between variables. For patients, PBUT clearance values were log-transformed to attain normal distribution. Then the correlation of tubular injury markers with all variables were tested using Pearson correlation. The estimates of association were calculated by multiple linear regression models. The univariate model (Model 1) was followed by multivariate regression models (Models 2–4), where the estimates were adjusted for eGFR in Model 2, additionally adjusted for age, sex and race in Model 3, and finally also UAER, smoking status, BMI and blood pressure in Model 4. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05 in all cases.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 813839. We further acknowledge financial support from the European Commission (KIDNEW, HORIZON-EIC-2022 Pathfinder program, grant agreement no. 101099092), and KidneyX (MI-TRAM), a public-private partnership between the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) and the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). This research was also supported by the Dutch Kidney Foundation Kolff+ program (DETOX; 22OK1019) and the Consortium Grant CP1805 “TASKFORCE.” R.M. is a member of the ESAO/ERA-EDTA-endorsed Work Group EUTox. We are grateful to Hiddo J.L. Heerspink and Bettine Haandrikman (Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands) for providing us with the samples and data of the IMPROVE study.

Author contributions

KGFG, a nephrologist specializing in chronic kidney disease and hypertension, and RM, an experimental nephrology expert, contributed to the study’s conception, design, supervision, and manuscript editing. TQN and RG, senior pathologists, assisted with the animal study and related analyses. RB, a technician, aided with the animal study. SMM provided data handling expertise. RWMV supervised patient data analysis, and RWS offered analytical support. SA, a PhD student, conducted the experiments, performed data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript review and agreed upon it.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent

The clinical study was registered in the Netherlands Trial Register (NTR 4439), complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines, and was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Groningen, the Netherlands (METc 2014/111) (28). All participants (N = 33) provided written informed consent before any study procedure started. All animal experiments were performed with the approval of the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of the University of Utrecht (DEC number 2009.II.11.129).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Atkins, R. C. The epidemiology of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int.67, S14–S18. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.09403.x (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta, S., Dominguez, M. & Golestaneh, L. Diabetic Kidney Disease: An Update. Med Clin North Am107, 689–705. 10.1016/j.mcna.2023.03.004 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Boer, I. H. et al. Diabetes Management in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Diabetes Care45, 3075–3090. 10.2337/dci22-0027 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossing, P. et al. Executive summary of the KDIGO 2022 Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes Management in Chronic Kidney Disease: an update based on rapidly emerging new evidence. Kidney Int.102, 990–999. 10.1016/j.kint.2022.06.013 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khanijou, V., Zafari, N., Coughlan, M. T., MacIsaac, R. J. & Ekinci, E. I. Review of potential biomarkers of inflammation and kidney injury in diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes Metab Res Rev38, e3556. 10.1002/dmrr.3556 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunkler, D. et al. Risk Prediction for Early CKD in Type 2 Diabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol10, 1371–1379. 10.2215/cjn.10321014 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porrini, E. et al. Non-proteinuric pathways in loss of renal function in patients with type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol.3, 382–391. 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00094-7 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nosadini, R. et al. Course of renal function in type 2 diabetic patients with abnormalities of albumin excretion rate. Diabetes49, 476–484. 10.2337/diabetes.49.3.476 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duan, S. et al. Current Challenges and Future Perspectives of Renal Tubular Dysfunction in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne)12, 661185, 10.3389/fendo.2021.661185 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Wei, P. Z. & Szeto, C. C. Mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetic kidney disease. Clin. Chim. Acta496, 108–116. 10.1016/j.cca.2019.07.005 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilbert, R. E. Proximal Tubulopathy: Prime Mover and Key Therapeutic Target in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Diabetes66, 791–800. 10.2337/db16-0796 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang, K. & Kestenbaum, B. Proximal Tubular Secretory Clearance: A Neglected Partner of Kidney Function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol13, 1291–1296. 10.2215/cjn.12001017 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trutin, I., Bajic, Z., Turudic, D., Cvitkovic-Roic, A. & Milosevic, D. Cystatin C, renal resistance index, and kidney injury molecule-1 are potential early predictors of diabetic kidney disease in children with type 1 diabetes. Front Pediatr10, 962048. 10.3389/fped.2022.962048 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He, P. et al. Significance of Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin as a Biomarker for the Diagnosis of Diabetic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Kidney Blood Press Res45, 497–509. 10.1159/000507858 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nigam, S. K. What do drug transporters really do?. Nat Rev Drug Discov14, 29–44. 10.1038/nrd4461 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mutsaers, H. A. et al. Uremic toxins inhibit transport by breast cancer resistance protein and multidrug resistance protein 4 at clinically relevant concentrations. PLoS ONE6, e18438. 10.1371/journal.pone.0018438 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao, H. et al. The roles of gut microbiota and its metabolites in diabetic nephropathy. Front Microbiol14, 1207132. 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1207132 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atoh, K., Itoh, H. & Haneda, M. Serum indoxyl sulfate levels in patients with diabetic nephropathy: Relation to renal function. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract.83, 220–226. 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.09.053 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barreto, F. C. et al. Serum indoxyl sulfate is associated with vascular disease and mortality in chronic kidney disease patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol4, 1551–1558. 10.2215/cjn.03980609 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin, C. J. et al. Indoxyl sulfate predicts cardiovascular disease and renal function deterioration in advanced chronic kidney disease. Arch Med Res43, 451–456. 10.1016/j.arcmed.2012.08.002 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu, I. W. et al. p-Cresyl sulphate and indoxyl sulphate predict progression of chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant26, 938–947. 10.1093/ndt/gfq580 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niewczas, M. A. et al. Uremic solutes and risk of end-stage renal disease in type 2 diabetes: metabolomic study. Kidney Int.85, 1214–1224. 10.1038/ki.2013.497 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen, Y. et al. Kidney Clearance of Secretory Solutes Is Associated with Progression of CKD: The CRIC Study. J Am Soc Nephrol31, 817–827. 10.1681/ASN.2019080811 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poesen, R. et al. Cardiovascular disease relates to intestinal uptake of p-cresol in patients with chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol15, 87. 10.1186/1471-2369-15-87 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Falke, L. L. et al. Hemizygous deletion of CTGF/CCN2 does not suffice to prevent fibrosis of the severely injured kidney. Matrix Biol31, 421–431. 10.1016/j.matbio.2012.06.002 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Gelder, M. K. et al. Protein-Bound Uremic Toxins in Hemodialysis Patients Relate to Residual Kidney Function, Are Not Influenced by Convective Transport, and Do Not Relate to Outcome. Toxins (Basel)12, 10.3390/toxins12040234 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Calle, P. & Hotter, G. Macrophage Phenotype and Fibrosis in Diabetic Nephropathy. Int J Mol Sci21, 10.3390/ijms21082806 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Kelly, K. J. & Dominguez, J. H. Rapid Progression of Diabetic Nephropathy Is Linked to Inflammation and Episodes of Acute Renal Failure. Am. J. Nephrol.32, 469–475. 10.1159/000320749 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khawaja, S., Jafri, L., Siddiqui, I., Hashmi, M. & Ghani, F. The utility of neutrophil gelatinase-associated Lipocalin (NGAL) as a marker of acute kidney injury (AKI) in critically ill patients. Biomarker Research7, 4. 10.1186/s40364-019-0155-1 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cruz, D. N. et al. Plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin is an early biomarker for acute kidney injury in an adult ICU population. Intensive Care Med36, 444–451. 10.1007/s00134-009-1711-1 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuwabara, T. et al. Urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin levels reflect damage to glomeruli, proximal tubules, and distal nephrons. Kidney Int.75, 285–294. 10.1038/ki.2008.499 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yi, A. et al. Effectiveness of Plasma and Urine Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin for Predicting Acute Kidney Injury in High-Risk Patients. Ann Lab Med41, 60–67. 10.3343/alm.2021.41.1.60 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sancho-Martínez, S. M. et al. Impaired Tubular Reabsorption Is the Main Mechanism Explaining Increases in Urinary NGAL Excretion Following Acute Kidney Injury in Rats. Toxicol. Sci.175, 75–86. 10.1093/toxsci/kfaa029 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang, X. Y. et al. Urine NGAL as an early biomarker for diabetic kidney disease: accumulated evidence from observational studies. Ren. Fail.41, 446–454. 10.1080/0886022x.2019.1617736 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Togashi, Y., Sakaguchi, Y., Miyamoto, M. & Miyamoto, Y. Urinary cystatin C as a biomarker for acute kidney injury and its immunohistochemical localization in kidney in the CDDP-treated rats. Exp Toxicol Pathol64, 797–805. 10.1016/j.etp.2011.01.018 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koyner, J. L. et al. Urinary cystatin C as an early biomarker of acute kidney injury following adult cardiothoracic surgery. Kidney Int.74, 1059–1069. 10.1038/ki.2008.341 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garg, V. et al. Novel urinary biomarkers in pre-diabetic nephropathy. Clin. Exp. Nephrol.19, 895–900. 10.1007/s10157-015-1085-3 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vaidya, V. S. et al. Kidney injury molecule-1 outperforms traditional biomarkers of kidney injury in preclinical biomarker qualification studies. Nat Biotechnol28, 478–485. 10.1038/nbt.1623 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gluhovschi, C. et al. Urinary Biomarkers in the Assessment of Early Diabetic Nephropathy. J Diabetes Res2016, 4626125. 10.1155/2016/4626125 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Magri, C. J. & Fava, S. The role of tubular injury in diabetic nephropathy. Eur J Intern Med20, 551–555. 10.1016/j.ejim.2008.12.012 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kern, E. F., Erhard, P., Sun, W., Genuth, S. & Weiss, M. F. Early urinary markers of diabetic kidney disease: a nested case-control study from the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT). Am. J. Kidney Dis.55, 824–834. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.11.009 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vallon, V. The proximal tubule in the pathophysiology of the diabetic kidney. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol300, R1009-1022. 10.1152/ajpregu.00809.2010 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jain, M. Histopathological changes in diabetic kidney disease. Clinical Queries: Nephrology1, 127–133. 10.1016/S2211-9477(12)70006-7 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tervaert, T. W. C. et al. Pathologic Classification of Diabetic Nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.21, 556–563. 10.1681/asn.2010010010 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zeni, L., Norden, A. G. W., Cancarini, G. & Unwin, R. J. A more tubulocentric view of diabetic kidney disease. J Nephrol30, 701–717. 10.1007/s40620-017-0423-9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fiseha, T. & Tamir, Z. Urinary Markers of Tubular Injury in Early Diabetic Nephropathy. International Journal of Nephrology2016, 4647685. 10.1155/2016/4647685 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Enomoto, A. et al. Interactions of human organic anion as well as cation transporters with indoxyl sulfate. Eur J Pharmacol466, 13–20. 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01530-9 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu, W., Bush, K. T. & Nigam, S. K. Key Role for the Organic Anion Transporters, OAT1 and OAT3, in the in vivo Handling of Uremic Toxins and Solutes. Sci. Rep.7, 4939–4939. 10.1038/s41598-017-04949-2 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deguchi, T. et al. Characterization of uremic toxin transport by organic anion transporters in the kidney. Kidney Int65, 162–174. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00354.x (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nigam, S. K. et al. Handling of Drugs, Metabolites, and Uremic Toxins by Kidney Proximal Tubule Drug Transporters. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN10, 2039–2049. 10.2215/cjn.02440314 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Masereeuw, R. et al. The kidney and uremic toxin removal: glomerulus or tubule?. Semin Nephrol34, 191–208. 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2014.02.010 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Poesen, R. et al. The Influence of Dietary Protein Intake on Mammalian Tryptophan and Phenolic Metabolites. PLoS ONE10, e0140820. 10.1371/journal.pone.0140820 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahmed, S. et al. Animal Models for Studying Protein-Bound Uremic Toxin Removal—A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci24 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Armani, R. G. et al. Gut Microbiome in Chronic Kidney Disease. Curr Hypertens Rep19, 29. 10.1007/s11906-017-0727-0 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bush, K. T., Singh, P. & Nigam, S. K. Gut-derived uremic toxin handling in vivo requires OAT-mediated tubular secretion in chronic kidney disease. JCI Insight5, 10.1172/jci.insight.133817 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Mihaila, S. M. et al. Drugs Commonly Applied to Kidney Patients May Compromise Renal Tubular Uremic Toxins Excretion. Toxins (Basel)12, 10.3390/toxins12060391 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Liu, H., Feng, J. & Tang, L. Early renal structural changes and potential biomarkers in diabetic nephropathy. Front Physiol13, 1020443. 10.3389/fphys.2022.1020443 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oraby, M. A., El-Yamany, M. F., Safar, M. M., Assaf, N. & Ghoneim, H. A. Dapagliflozin attenuates early markers of diabetic nephropathy in fructose-streptozotocin-induced diabetes in rats. Biomed. Pharmacother.109, 910–920. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.100 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Togashi, Y. & Miyamoto, Y. Urinary cystatin C as a biomarker for diabetic nephropathy and its immunohistochemical localization in kidney in Zucker diabetic fatty (ZDF) rats. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol.65, 615–622. 10.1016/j.etp.2012.06.005 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Phatchawan, A., Chutima, S., Anusorn, L. & Varanuj, C. Decreased Renal Organic Anion Transporter 3 Expression in Type 1 Diabetic Rats. Am. J. Med. Sci.347, 221–227. 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3182831740 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu, C. et al. The altered renal and hepatic expression of solute carrier transporters (SLCs) in type 1 diabetic mice. PLoS ONE10, e0120760. 10.1371/journal.pone.0120760 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lungkaphin, A. et al. Impaired insulin signaling affects renal organic anion transporter 3 (Oat3) function in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. PLoS ONE9, e96236. 10.1371/journal.pone.0096236 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 63.Jensen, D. et al. Megalin dependent urinary cystatin C excretion in ischemic kidney injury in rats. PLoS ONE12, e0178796. 10.1371/journal.pone.0178796 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Conti, M. et al. Urinary cystatin C as a specific marker of tubular dysfunction. Clin Chem Lab Med44, 288–291. 10.1515/cclm.2006.050 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nakai, K. et al. Streptozotocin induces renal proximal tubular injury through p53 signaling activation. Sci Rep13, 8705. 10.1038/s41598-023-35850-w (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Petrykiv, S. I., Laverman, G. D., de Zeeuw, D. & Heerspink, H. J. L. The albuminuria-lowering response to dapagliflozin is variable and reproducible among individual patients. Diabetes Obes Metab19, 1363–1370. 10.1111/dom.12936 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.