Abstract

We previously identified a stromal cell-derived inducing activity (SDIA), which induces differentiation of neural cells, including midbrain tyrosine hydroxylase-positive (TH+) dopaminergic neurons, from mouse embryonic stem cells. We report here that SDIA induces efficient neural differentiation also in primate embryonic stem cells. Induced neurons contain TH+ neurons at a frequency of 35% and produce a significant amount of dopamine. Interestingly, differentiation of TH+ neurons from undifferentiated embryonic cells occurs much faster in vitro (10 days) than it does in the embryo (≈5 weeks). In addition, 8% of the colonies contain large patches of Pax6+-pigmented epithelium of the retina. The SDIA method provides an unlimited source of primate cells for the study of pathogenesis, drug development, and transplantation in degenerative diseases such as Parkinson's disease and retinitis pigmentosa.

Initiation of vertebrate neural differentiation in the embryonic ectoderm is triggered by inductive signals emanating from axial mesoderm (1, 2). In Xenopus, neural inducers from Spemann's organizer such as Noggin and Chordin play a major role in this process (3, 4). The neural inducers bind to and inactivate bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), which suppresses neural differentiation of ectodermal cells and promotes epidermal differentiation. In Drosophila, Sog (fly homologue of Chordin) is a positive regulator of the initiation of central nervous system formation and antagonizes the activity of Dpp (fly BMP homologue), suggesting a conserved role of BMP and anti-BMP signals in neural determination across species (5).

In amphibians, suppression of BMP signaling is proven to be essential and sufficient for neural induction in ectodermal tissues. In mammals, by contrast, very few experimental data have been available regarding the mechanisms underlying early neural differentiation. Recent studies have shown that attenuation of BMP signaling is essential, but not sufficient, for neural differentiation in mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells. Addition of BMP4 suppresses neural differentiation of ES cells both in floating culture (embryoid body) (6) and in substrate-attached cell culture (7). However, blockade of BMP signals by adding soluble BMP receptor–Fc chimera proteins or by overexpressing Chordin does not significantly promote neural differentiation of mouse ES cells, suggesting that some additional signaling is required for mammalian neural induction (7).

We previously described a strong neuralizing activity present on the cell surface of stromal cells and named it SDIA (stromal cell-derived inducing activity) (7). In the absence of exogenous BMP4, mouse ES cells efficiently differentiate into neural precursors and neurons [>90% cells become neural cell adhesion molecule-positive (NCAM+)] when cultured on SDIA-possessing mouse stromal cells (PA6 cells) for a week. The SDIA method has several advantages in production of neurons as compared with previous embryoid body methods (8, 9). First, the SDIA method is technically simple. ES cells are grown in a flat culture from single cells into colonies. Second, neural differentiation of ES cells is not only efficient but also speedy; the postmitotic neuron marker TuJ (class III β-tubulin) appears on day 4–5. Finally (and most importantly), SDIA-treated ES cells differentiate into midbrain dopaminergic neurons at a high frequency; 30% of neurons derived from mouse ES cells are dopaminergic and produce significant amounts of dopamine. These cells survive at a reasonable rate (≈20%) 2 weeks after implantation in mouse striatum and extend dopaminergic neurites into the target tissue (7).

Considering the usefulness in medical research, we have recently established pluripotent embryonic stem cell lines from blastocysts of Macaca fascicularis (cynomolgus monkey), which is commonly used in preclinical studies (10). ES cells derived from primate (human and monkey) blastocysts possess a number of characteristics distinct from mouse cells, such as surface antigens, leukemia inhibitory factor-independency, and long doubling times (10–14). In this study, we have tested the SDIA method with primate ES cells and investigated its potential application for producing medically useful cells.

Materials and Methods

Maintenance of Primate ES Cells.

Cynomolgus monkey ES cell lines were established, and their pluripotency was confirmed by teratoma formation in severe combined immunodeficiency mice as described previously (10). Undifferentiated ES cells were maintained on a feeder layer of mitomycin C-treated mouse embryonic fibroblasts in DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol/1,000 units/ml leukemia inhibitory factor/20% knockout serum replacement (GIBCO)/4 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor. Subculturing of ES cells was performed by using 0.25% trypsin in PBS with 20% knockout serum replacement and 1 mM CaCl2 as described (10).

Induction of Neural Differentiation of Primate ES Cells.

PA6 cells were plated on type I collagen-coated chamber slides (Falcon) or gelatin-coated dishes and used as a feeder cell layer (7, 15). To strictly avoid contamination by incidentally differentiating cells, we manually selected undifferentiated ES cell colonies with stem cell-like morphology (tightly packed cells with a high nucleus/cytoplasm ratio; see Fig. 1A). Undifferentiated ES cell colonies were first washed twice with GMEM medium supplemented with 10% knockout serum replacement/1 mM pyruvate/0.1 mM nonessential amino acids/0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (differentiation medium). After trypsinization for 5 min at 37°C, partially dissociated ES cell clumps (10–50 cells/one clump) were plated on PA6 cells at a density of 500 clumps/10-cm dish and cultured in the differentiation medium for 3 weeks or indicated periods. Medium was changed every third day. Unlike mouse ES cells, monkey ES cells do not form colonies from single cells on PA6 cells. Low cloning efficiency has been also reported for human ES cells (12–14). It is therefore necessary to plate clumps of 10–50 undifferentiated ES cells for starting induction. Two independent ES cell lines (CMK 6 and 9; normal karyotypes) were used and found to give similar results. In some experiments, 0.5 nM BMP4 (R & D Systems) was added to the differentiation medium on day 0 and at each medium change.

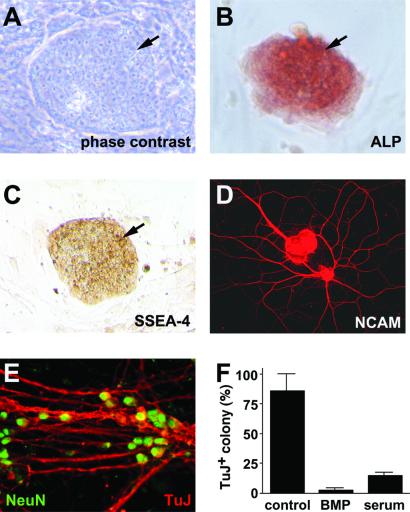

Figure 1.

Neural differentiation of monkey ES cells by SDIA. (A) Phase contrast image of an undifferentiated ES cell colony. (B and C) Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining and SSEA-4 immunostaining of undifferentiated ES cell colonies, respectively. Arrows indicate colonies of ES cells. Surrounding cells are feeder cells (mouse embryonic fibroblasts). (D) SDIA-treated ES colonies stained with anti-NCAM antibody. (E) SDIA-induced neurons double-stained with anti-NeuN (green) and TuJ (red) antibodies (high magnification view). (F) Suppression of neuronal differentiation by BMP4 and serum. Serum (instead of knockout serum replacement) was used in the differentiation medium.

Immunostaining.

The antibodies were purchased from Chemicon (NCAM/polyclonal/used in a dilution of 1:300, TH/polyclonal/1:100, NeuN/monoclonal/1:100, ChAT/polyclonal/1:20, peripherin/polyclonal/1:100, and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase (DBH)/polyclonal/1:200), Diasorin (serotonin/polyclonal/1:1,000), DSHB (Islet-1/monoclonal/1:200, and SSEA-4/monoclonal/1:50), Santa Cruz Biotechnology (GAD/polyclonal/1:10), Babco (Richmond, CA) (TuJ1/polyclonal/1:600 and Pax6/polyclonal/1:500), and Medac (Wedel, Germany) (CCK-8/polyclonal/1:100). The specificity of these antibodies was tested by using appropriate tissues or cells as positive controls. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and incubated with primary antibodies. Localization of antigens was visualized by using secondary antibodies conjugated with FITC, Cy3, or horseradish peroxidase. FITC-phalloidin was purchased from Molecular Probes.

Positive colonies were defined as colonies containing positive cells regardless of population. To estimate the efficacy of the differentiation at the cell level, colonies were randomly selected, and the numbers of positive cells were counted after a 3-week differentiation period. The numbers of total cells were examined by using DAPI, YOYO-1 (Molecular Probe), or anti-human nuclei antibody (Chemicon; also recognizing monkey nuclei). When necessary, data are given as mean ± standard deviation obtained from at least three independent experiments.

Detection of Dopamine.

Monkey ES cells were cultured on a PA6 cell layer for 3 weeks and were incubated for 15 min in Hanks' balanced salt solution (3 ml/10-cm dish) containing 56 mM KCl to induce depolarization of neurons. Then, the media were stabilized with 0.1 mM EDTA and analyzed for dopamine by using HPLC with fluorescence detection as described previously (16). Results were validated by coelution with authentic substances.

RNA Analysis.

Reverse transcriptase–PCR was performed as described previously (4). The primers used are as follows: Lmx1b, GCAGCGGCTGCATGGAGAAGATCGC and GGTTCTGAAACCAGACCTGGACCAC; Nurr1, CTCCCAGAGGGAACTGCACTTCG and CTCTGGAGTTAAGAAATCGGAGCTG; Nrp-1/Musashi1, CGAGCTCGACTCCAAAACAATTGACC and TCTACACGGAATTCGGGGAACTGGTA; and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, GTGAAGGTCGGAGTCAACG and GGTGAAGACGCCAGTGGACTC. PCR products using these primers were confirmed by sequencing.

Culture of Pigmented Epithelium.

After monkey ES cells were cultured on a PA6 cell layer for 3 weeks, a patch of pigmented cells was mechanically isolated by using a 200-μl tip and plated on a fresh PA6 cell layer in differentiation medium or on a collagen I-coated dish in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 20 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor. The pigmented cells grew reasonably fast in both cases and could be replated at least twice.

Sorting Neural Cells.

The cells were dissociated with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA for 10 min at 37°C, filtered with nylon mesh, spun down, and resuspended in Hanks' balanced salt solution containing 1% BSA. After incubation with allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD56 antibody (NKH-1, Beckman Coulter) for 20 min at 4°C, positive cells were sorted with FACS Vantage SE (Becton Dickinson). Sorted cells were cultured on a laminine/poly-l-ornithine-coated dish and were immunostained with neural- and neuron-specific antibodies such as anti-NCAM (cytoplasmic domain) and TuJ, respectively.

Transplantation Experiment.

For 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) treatment, 6-week-old severe combined immunodeficiency mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital and fixed on a stereotactic device (Narishige, Tokyo); 6-OHDA (8 mg/ml) was injected unilaterally with a glass needle at three sites into the striatum as described previously (7). SDIA-treated ES cells were implanted into the ipsilateral striatum 7 days after 6-OHDA injection. Animal experiments were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines.

ES cells were cultured on PA6 cells for 3 weeks in differentiation medium. Differentiated ES colonies were detached en bloc from feeder cells by treatment with collagenase B (1 mg/ml) and DNase I (25 μg/ml) for 5 min at room temperature. Clumps of differentiated ES cells were labeled with 5 μg/ml CM-DiI in PBS supplemented with 4 mg/ml glucose for 20 min at room temperature, rinsed twice with GMEM, and then suspended in GMEM. By using a blunt-ended 26G Hamilton syringe, 9 × 104 cells (containing 1 × 104 TH+ neurons) were slowly injected into the striatum (A + 0.9, L + 2.0, V + 3.0) over a 3-min period. In controls, suspension medium was injected. Two weeks after the transplantation, recipients were anesthetized and perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS.

Results and Discussion

Induction of Neural Differentiation in Primate ES Cells on PA6 Cells.

The monkey ES cell lines CMK 6 and 9 (10) used in this work express high levels of undifferentiated state-specific markers such as alkaline phosphatase and SSEA-4 (ES colonies are shown by arrows in Fig. 1 A–C) but not the pan-neural marker NCAM (data not shown), even after maintenance in culture for more than 6 months.

We applied the SDIA method to primate ES cells with minor modifications (see Materials and Methods). After culture on PA6 cells for 2 weeks, extensive neurites were found in a majority of primate ES cell colonies (97 ± 3%, n = 78), which contained a large number of cells positive for NCAM (neural precursors and neurons, Fig. 1D) and postmitotic neurons positive for class III β-tubulin (TuJ) and NeuN markers (Fig. 1E). At the cellular level, 45 ± 13% of the SDIA-treated primate cells (n = 420) were NCAM-positive neural cells, and 25 ± 6% (n = 660) were TuJ-positive postmitotic neurons. When primate ES cells were cultured on a gelatin-coated dish without PA6, less than 1% of cells became NCAM+ (n = 530). Our previous study with mouse ES cells has shown that SDIA treatment induces NCAM and TuJ in 92% and 53% of mouse cells, respectively (7, 15), indicating that the efficiency of neural differentiation in primate ES cells by SDIA is about half of that in mouse cells. One possible influence on this neural/non-neural ratio might be the qualitative difference of the non-neural cells. Non-neural cells in the SDIA-treated primate colonies were mostly fast-growing E-cadherin-negative mesenchymal cells, whereas those in the murine colonies were slower growing E-cadherin-positive epithelial cells (unpublished observations).

We next examined inhibitors of neural differentiation in primate cells. Our previous study with mouse ES cells has shown that BMP and serum inhibit neural differentiation of mouse cells (7). Similarly, addition of BMP4 (0.5 nM) or FBS (5%) efficiently suppressed neuronal differentiation in primate cells (Fig. 1F), suggesting that primate and mouse ES cells respond to the same positive (SDIA) and negative (BMP and serum) factors in neural differentiation.

Induction of Dopaminergic Neurons from Primate ES Cells.

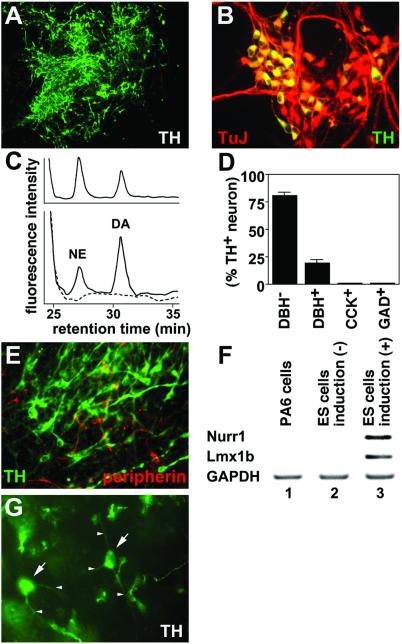

SDIA has been reported to induce TH+ dopaminergic neurons efficiently from mouse ES cells (7, 15). We therefore tested whether similar findings could be obtained with primate cells. After 2 weeks of induction, 80 ± 12% of the colonies contained TH+ cells (n = 40; Fig. 2A). At the cellular level, 35 ± 6% of the TuJ+ postmitotic neurons were TH-positive (n = 560; Fig. 2B). Next, the amount of dopamine released upon depolarization was analyzed by HPLC assay (Fig. 2C). The SDIA-treated ES cells released 1.0 pmol/107 cells in response to high K+ depolarizing stimuli, indicating that they contain a significant number of functional dopaminergic neurons (Fig. 2C Lower; authentic substances in Fig. 2C Upper). In addition to dopamine, norepinephrine was also detected at the level of 0.5 pmol/107 cells. Consistently, 81% of TH+ neurons (28% of total neurons) were DBH-negative (dopaminergic neurons) on day 18, whereas the rest were DBH-positive (norepinephrinergic/epinephrinergic neurons) (n = 200) (Fig. 2D). The dopaminergic neurons induced by SDIA were CCK-negative (positive in A10 neuron; ref. 17) and GAD-negative (positive in olfactory bulb dopaminergic neurons; ref. 18) (Fig. 2D). We next asked whether these TH+ neurons have characteristics of central nervous system or peripheral nervous system neurons. SDIA-induced TH+ neurons were negative for peripherin, which is a specific marker for PNS neurons (19) (n = 200; Fig. 2E). Further, reverse transcriptase–PCR analyses (Fig. 2F) showed that SDIA-induced neurons expressed midbrain dopaminergic neuron markers, such as Nurr1 and Lmx1b (20), whereas neither undifferentiated ES cells nor feeder cells did.

Figure 2.

SDIA-induced neurons contain a high proportion of dopaminergic neurons. (A) Immunostaining of SDIA-induced neurons with anti-TH antibody. (B) A high magnification view of SDIA-induced neurons double-stained with anti-TH (green) and TuJ (red) antibodies. Yellow neurons indicate TH+ neurons. (C) Detection of dopamine secreted by SDIA-induced neurons. Reverse-phase HPLC patterns using the 1,2-diphenylethylenediamine-derivatization method are shown. Dopamine and norepinephrine standards were used to validate the results (Upper). (Lower) A black line shows a chromatography pattern of the medium conditioned with differentiated ES cells. DA and NE indicate peaks of dopamine and norepinephrine, respectively. The dopamine and norepinephrine peaks were not detected in control medium (conditioned with feeder cells only; a broken line, Lower). (D) SDIA-induced neurons were examined by staining with anti-TH, anti-DBH, anti-CCK, and anti-GAD antibodies. Proportions of DBH−, DBH+, CCK+, and GAD+ neurons in TH+ neurons are shown. (E) SDIA-induced neurons were stained with anti-TH (green) and anti-peripherin (red) antibodies. (F) Reverse transcriptase–PCR analyses with markers (Nurr1, Lmx1b) of mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons. (G) Surviving TH+ neurons in the striatum 2 weeks after grafting. Arrows and arrowheads indicate cell bodies and neurites of TH+ neurons, respectively.

We next implanted SDIA-treated primate ES cells into the mouse striatum by the stereotaxic method. The striatum is a target nucleus of midbrain dopaminergic neurons and contains dopaminergic fibers but not cell bodies of dopaminergic neurons. SDIA-treated primate ES cells containing 1 × 104 TH+ neurons were grafted into the severe combined immunodeficiency mouse striatum from which dopaminergic fibers were depleted by 6-OHDA treatment as described previously (7). Two weeks after implantation (Fig. 2G), 8.3 ± 3.2% of implanted TH+ neurons (arrows, cell bodies) survived and extended neurites (arrowheads) in the tissue. This value is roughly comparable to that in the previous mouse study (7). We are currently attempting implantation into the monkey brain to evaluate long-term survival of primate TH+ neurons.

Temporal Regulation of Primate Neural Differentiation.

The time required for fetal development varies significantly among different mammalian species. The gestation period of mice is 20 days, whereas that of M. fascicularis is 160 days. This large difference in time (8-fold) resides mainly in the lengths of the organogenetic and the fetal periods rather than in the early embryonic period.

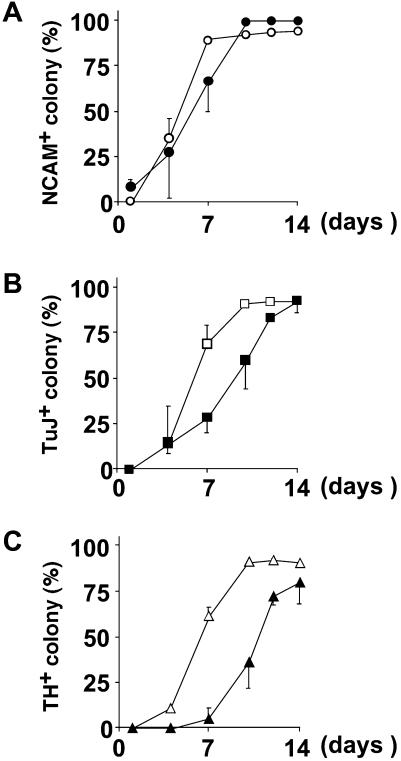

We therefore examined temporal regulation of neuronal makers during SDIA-induced neural differentiation in primate and mouse ES cells. The neural precursor marker Nrp-1/Musashi1 (21) was detected on day 4 and onward both in primate and mouse cells by reverse transcriptase–PCR analyses (data not shown). Next, temporal expression profiles of NCAM (pan-neural) and TuJ (neuronal) markers were analyzed by immunostaining as shown in Fig. 3 A and B, respectively (closed, primate cells; open, mouse cells). The expression of NCAM and TuJ took 1–3 days and 3–5 days longer in primate cells than in murine cells. TH+ cells (Fig. 3C) first appeared on day 10 in the primate colonies, whereas the onset of TH+ cell generation in the murine colonies was between days 5–7.

Figure 3.

Time course studies of neural marker expression using mouse (open) and monkey (closed) ES cells. Mouse and monkey ES cells were cultured on a PA6 feeder layer for indicated times and stained with anti-NCAM (A), TuJ (B), and anti-TH (C) antibodies.

The genesis of midbrain TH+ neurons occurs during the organogenetic period. TH+ neurons first appear in the murine midbrain on E10.5–11.5 (22, 23). In mice, the number of days required for dopaminergic neuron differentiation by SDIA in vitro (7 days) is roughly the same as that for in vivo genesis of TH+ neurons from the inner cell mass (7–8 days) (ref. 7 and Fig. 3C). In Macaca, TH+ neurons are reported to first appear about 5 weeks after implantation (24). By contrast, in vitro induction of TH+ neurons from primate ES cells by SDIA took only 10–12 days (Fig. 3C), showing that primate TH+ neurons differentiate from undifferentiated embryonic cells much faster in vitro than in vivo. One explanation might be that the speed of cell differentiation is actively reduced in primate embryos to allow sufficient numbers of precursor cells to accumulate for construction of the large primate brain. Regardless of the reason, in practice, the SDIA-based approach carries the advantage of requiring less time to produce dopaminergic neurons than had been expected from the in vivo time course.

Other Neuronal Markers Induced in SDIA-Treated Primate ES Cells.

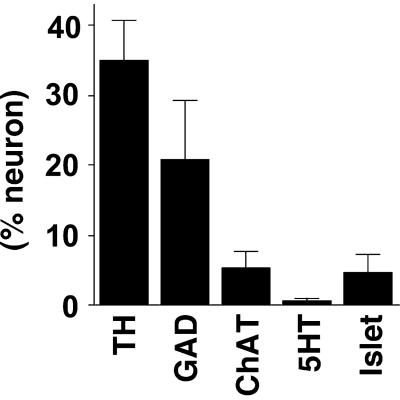

We next examined characteristics of TH-negative neurons induced by SDIA with various markers (Fig. 4). In addition to TH+ neurons, the SDIA-treated primate ES cells gave rise to GAD-positive (GABAergic; 20 ± 8% of postmitotic neurons), ChAT-positive (cholinergic; 5 ± 3%), and 5HT-positive (serotonergic; 1 ± 0.5%) neurons (n = 300). The proportion of transmitter profiles is similar to that found with SDIA-treated mouse ES cells (7). Interestingly, neurons positive for Islet-1 (marker of motoneurons and dorsal root ganglion neurons) were found in primate cells (5 ± 3%, n = 160) and in mouse cells (10–15%; K.M., H.K., and Y.S., unpublished results).

Figure 4.

Expression of neurotransmitter markers and Islet-1. SDIA-induced neurons were stained with anti-TH, anti-GAD (GABAergic), anti-ChAT (cholinergic), anti-5HT (serotonergic), and anti-Islet-1 antibodies. Positive rates per postmitotic neurons are shown.

Generation of Pigmented Epithelial Cells from Primate ES Cells.

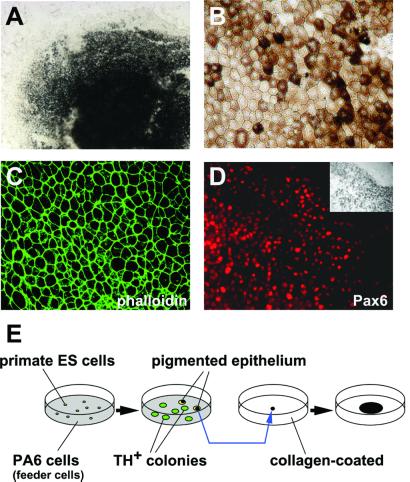

One unexpected finding from the primate study was the appearance of epithelial cells with massive pigmentation, which was rarely observed in SDIA-treated mouse ES cells or in primate ES cells cultured on the collagen-coated dish (unpublished observations). After culture on PA6 cells for 3 weeks, large patches of pigmented cells were present in 8 ± 4% of the primate ES cell colonies (n = 200; Fig. 5A) and grew at a constant rate on the feeder cells. The polygonal morphology with a compact cell–cell arrangement (Fig. 5B) was reminiscent of the pigmented epithelium of the eye (25) and clearly distinct from pigmented melanocytes derived from neural crest (26). Further, phalloidin staining showed polygonal “actin bundles” typical for pigmented epithelium (Fig. 5C) (27), rather than the “stress fiber” actin staining found in neural crest-derived pigment cells (28). From an ontogenic view, the pigmented epithelium of the eye is a derivative of the diencephalon and has the same origin (optic cup) as the neural retina. Consistently, pigmented epithelial cells from primate ES cells were positive for the optic cup marker Pax6 (reviewed in ref. 29) (Fig. 5D). These cells could be easily isolated manually under a dissecting microscope with a pipetman tip and expanded to confluency on PA6 cells as a feeder layer or on a collagen-coated dish without feeder cells (Fig. 5E; see Materials and Methods).

Figure 5.

Pigmented epithelium induced by SDIA. (A) Bright field view of induced pigmented epithelium in a primate ES colony. (B) High magnification view of pigmented epithelium 3 weeks after replating on a collagen I-coated dish. Note the polygonal shape of the cells. (C) “Actin bundles” in the pigmented epithelium stained with FITC-phalloidin. (D) Immunostaining with anti-Pax6 antibody. (Inset) Bright field view. (E) Schematic illustration of experimental procedures for expansion of pigmented epithelia. TH+ colonies did not contain pigmented cells (n = 200).

The pigmented epithelium of the eye is a target tissue of autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Therefore, the availability of primate pigmented epithelia generated in vitro should facilitate the pathogenetic and therapeutic studies of this retinal degenerative disease (30, 31). Also, because pigmented epithelia are derived from the optic cup, the SDIA method with modifications offers the potential to generate neural retinal cells such as photoreceptor cells in the future.

Application of Dopaminergic Neurons Derived from Primate ES Cells.

In this report, we have shown that primate cells are successfully coaxed to differentiate into neural cells by the SDIA method. Although the percentage of neural cells in primate cell colonies is about half of that in mouse ones (45% vs. 92% as discussed above), this may be partially compensated by selective sorting. Using single-step FACS purification with the neural-specific surface antigen CD56 as a selection marker, SDIA–induced neural cells can be enriched by ≈2-fold, i.e., to the purity of 90% NCAM+ and 54% TuJ+ (unpublished data; see Materials and Methods). Also, neural precursor cells may be enriched by using a combination of other surface-sorting markers shown in recent studies, such as CD133+, CD45−, CD34−, CD24low, and PNAlow (32, 33).

The ability to produce primate dopaminergic neurons by this simple in vitro preparation should greatly facilitate research in numerous areas of Parkinson's disease therapeutics (34–36). For instance, monkey dopaminergic neurons provide good in vitro systems for drug screening concerning the function or survival of dopaminergic neurons and for toxicity testing of substances potentially harmful to dopaminergic neurons, such as rotenone (37). This approach can be modified to a semi in vivo system by grafting these neurons into the severe combined immunodeficiency mouse brain. Also, primate dopaminergic neurons prepared by this method can be used to raise monoclonal antibodies against dopaminergic neuron-specific surface antigens for sorting.

Our present and previous (7) works have demonstrated that SDIA can induce dopaminergic neuron differentiation from murine and non-human primate ES cells. Considering the close phylogenetic relationship between humans and Macaca (both belong to the family of Catarrhini, the suborder of Anthropoidea), it is expected that the SDIA method should be applicable to the generation of dopaminergic neurons also from human ES cells. Over the last decade, a number of clinical efforts have been made for neuronal transplantation therapy for Parkinson's disease (38). Grafting fetal midbrain tissues into the striatum significantly improves motor disorders in a substantial number of cases. The bottleneck of this therapeutic strategy has been the supply of neurons along with the accompanying ethical issues. The SDIA-based approach offers a practical alternative to brain tissues from aborted fetuses. As a first step toward this goal, we are planning to perform therapeutic studies by implanting primate dopaminergic neurons generated by SDIA into the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-treated monkey brain. At the level of efficacy shown in the present work (where dopaminergic neurons occupy 28% of postmitotic neurons, which are 25% of total cells), ≈5 × 107 total cells are necessary to successfully implant 3 × 105 dopaminergic cells (an expected therapeutic dose for neural grafting) (38), given that the survival rate after grafting is 8%. This indicates that only a dozen culture dishes are needed for one transplantation, demonstrating the practical feasibility of this approach.

In conclusion, the SDIA method is a promising approach that brings stem cell therapy for Parkinson's disease toward the practical level.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to R. Yu, M. Kosaka, and N. Rao for comments on this work, to Y. Nakano for excellent technical assistance, and to Tanabe Seiyaku, Ltd. for help in primate ES cell preparation. This work was supported by grants from the Organization of Pharmaceutical Safety and Research (to Y.S.), the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (to N.N.), the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (to Y.S. and N.N.), the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (to Y.S.), and the Human Frontier Science Program Organization (to Y.S.).

Abbreviations

- BMP

bone morphogenetic protein

- ES

embryonic stem

- NCAM

neural cell adhesion molecule

- 6-OHDA

6-hydroxydopamine

- SDIA

stromal cell-derived inducing activity

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- DBH

dopamine-beta-hydroxylase

References

- 1.Hemmati-Brivanlou A, Melton D. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1997;20:43–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sasai Y, De Robertis E M. Dev Biol. 1997;182:5–20. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamb T M, Knecht A K, Smith W C, Stachel S E, Economides A N, Stahl N, Yancopolous G D, Harland R M. Science. 1993;262:713–718. doi: 10.1126/science.8235591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sasai Y, Lu B, Steinbeisser H, De Robertis E M. Nature (London) 1995;376:333–336. doi: 10.1038/376333a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Robertis E M, Sasai Y. Nature (London) 1996;380:37–40. doi: 10.1038/380037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finley M F, Devata S, Huettner J E. J Neurobiol. 1999;40:271–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawasaki H, Mizuseki K, Nishikawa S, Kaneko S, Kuwana Y, Nakanishi S, Nishikawa S-I, Sasai Y. Neuron. 2000;28:31–40. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bain G, Kitchens D, Yao M, Huettner J E, Gottlieb D I. Dev Biol. 1995;168:342–357. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee S H, Lumelsky N, Studer L, Auerbach J M, McKay R D. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:675–679. doi: 10.1038/76536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suemori H, Tada T, Torii R, Hosoi Y, Kobayashi K, Imahie H, Kondo Y, Iritani A, Nakatsuji N. Dev Dyn. 2001;222:273–279. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomson J A, Kalishman J, Golos T G, Durning M, Harris C P, Becker R A, Hearn J P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7844–7848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomson J A, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro S S, Waknitz M A, Swiergiel J J, Marshall V S, Jones J M. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amit M, Carpenter M K, Inokuma M S, Chiu C P, Harris C P, Waknitz M A, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Thomson J A. Dev Biol. 2000;227:271–278. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reubinoff B E, Pera M F, Fong C Y, Trounson A, Bongso A. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:399–404. doi: 10.1038/74447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawasaki H, Mizuseki K, Sasai Y. In: Methods in Molecular Biology. Turksen K, editor. Vol. 185. Totowa, NJ: Humana; 2001. pp. 217–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitsui A, Nohta H, Ohkura Y. J Chromatogr. 1985;344:61–70. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)82007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schalling M, Friberg K, Seroogy K, Riederer P, Bird E, Schiffmann S N, Mailleux P, Vanderhaeghen J J, Kuga S, Goldstein M, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:8427–8431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kosaka T, Hataguchi Y, Hama K, Nagatsu I, Wu J Y. Brain Res. 1985;343:166–171. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91172-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Troy C M, Brown K, Greene L A, Shelanski M L. Neuroscience. 1990;36:217–237. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90364-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smidt M P, Asbreuk C H, Cox J J, Chen H, Johnson R L, Burbach J P. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:337–341. doi: 10.1038/73902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keyoung H M, Roy N S, Benraiss A, Louissaint A, Jr, Suzuki A, Hashimoto M, Rashbaum W K, Okano H, Goldman S A. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:843–850. doi: 10.1038/nbt0901-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foster G A, Schultzberg M, Kokfelt T, Goldstein M, Hemmings H C, Jr, Ouimet C C, Walaas S I, Greengard P. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1988;6:367–386. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(88)90020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawano H, Ohyama K, Kawamura K, Nagatsu I. Dev Brain Res. 1995;86:101–113. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(95)00018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ronnekleiv O K, Naylor B R. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7330–7343. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07330.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marmor M F. In: The Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Marmor M F, Wolfensberger T J, editors. New York: Oxford Univ. Press; 1998. pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le Douarin N M, Kalcheim C. In: The Neural Crest. Le Douarin N M, Kalcheim C, editors. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1999. pp. 252–303. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burke J M. In: The Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Marmor M F, Wolfensberger T J, editors. New York: Oxford Univ. Press; 1998. pp. 86–102. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scott G, Cassidy L, Abdel-Malek Z. Exp Cell Res. 1997;237:19–28. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jean D, Ewan K, Gruss P. Mech Dev. 1998;76:3–18. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li L X, Turner J E. Exp Eye Res. 1988;47:911–917. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(88)90073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lopez R, Gouras P, Kjeldbye H, Sullivan B, Reppucci V, Brittis M, Wapner F, Goluboff E. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1989;30:586–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uchida N, Buck D W, He D, Reitsma M J, Masek M, Phan T V, Tsukamoto A S, Gage F H, Weissman I L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14720–14725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rietze R L, Valcanis H, Brooker G F, Thomas T, Voss A K, Bartlett P F. Nature (London) 2001;412:736–739. doi: 10.1038/35089085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hynes M, Rosenthal A. Neuron. 2000;28:11–14. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindvall O. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:635–636. doi: 10.1038/10844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gage F H. Science. 2000;287:1433–1438. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Betarbet R, Sherer T B, MacKenzie G, Garcia-Osuna M, Panov A V, Greenamyre J T. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1301–1306. doi: 10.1038/81834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olanow C W, Kordower J H, Freeman T B. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:102–109. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)80038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]