Abstract

We previously demonstrated that the neural cell adhesion molecule (N-CAM) inhibited the proliferation of cultured rat hippocampal progenitor cells and increased the number of neurons generated. We demonstrate here that the continued presence of fibroblast growth factor 2 along with N-CAM or brain-derived neurotrophic factor over 12 days of culture greatly increased the number of both progenitors and neurons. These progenitor-derived neurons expressed neurotransmitters, neurotransmitter receptors, and synaptic proteins in vitro consistent with those expressed in the mature hippocampus. Progenitor cells cultured on microelectrode plates formed elaborate neural networks that exhibited spontaneously generated action potentials after 21 days. This activity was observed only in cultures grown in the presence of fibroblast growth factor 2 and either N-CAM or brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Analysis of neuronal activity after various pharmacological treatments indicated that the networks formed functional GABAergic and glutamatergic synapses. We conclude that mitogenic growth factors can synergize with N-CAM or neurotrophins to generate spontaneously active neural networks from neural progenitors.

The controlled differentiation of multipotent progenitor or stem cells into neurons may prove fundamental to the development of cellular therapies for neurological trauma and disease. Agents that alter the differentiation properties of neural progenitors may bias these cells to acquire or maintain desired neuronal phenotypes in vitro or in vivo. The determination of appropriate culture conditions and of regulators of differentiation is necessary to convert progenitors into neurons that are physiologically active and that can integrate into functional neural networks.

Neurotrophins are important regulators of hippocampal neural stem cell differentiation (1, 2). The neurotrophins brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and NT-3 promote the differentiation of hippocampal progenitor cells into excitatory and inhibitory neurons after removal of the mitogenic growth factor fibroblast growth factor (FGF)2 (3). Differentiation induced by either BDNF or NT-3 has been reported to up-regulate the expression of functional channels and receptors in primary cultures of embryonic hippocampal progenitors (4), but so far it has not been shown that treated cells exhibit spontaneous action potentials. It is known, however, that the inclusion of FGF2 in neuronal cultures increases the proliferation of neuroblasts, supports an elaborate extension of processes, enhances neuronal survival, and modulates synaptic transmission (5–7).

On the basis of these observations, the present study examined the influences of FGF2 together with BDNF or the neural cell adhesion molecule (N-CAM) on progenitor differentiation and physiological activity. N-CAM influences cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, neurite outgrowth, and fasciculation during development and in the adult (8). Our previous studies indicated that N-CAM binding inhibited proliferation of rat hippocampal progenitor cells (9) in culture similar to its effect on astrocytes (10, 11). Moreover, N-CAM also promoted progenitor differentiation toward a neuronal phenotype in the presence or absence of FGF2 (9), indicating that this CAM exhibited neurotrophin-like activity. In the present study, we have found that, on addition of either N-CAM or BDNF, hippocampal progenitors differentiate into similar types of neurons and that, in the presence of FGF2, functional neuronal networks that exhibit spontaneous activity are generated.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Materials were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich unless indicated. The following antibodies were used: nestin (PharMingen); microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2B) (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY); glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), neuron specific enolase (Dako); neurofilament protein-M/H, synaptotagmin, synapsin 1, glutamate decarboxylase (GAD65/67), glutamate receptor 2/3 (GluR2/3) (Chemicon); N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor (NR1) (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY). Dopamine, 2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid, and 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX) were from Research Biochemicals (Natick, MA). Trimethylolpropane phosphate (TMPP) was supplied by the Naval Health Research Center/Toxicology Detachment (Wright–Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, OH).

Hippocampal Progenitor Cell Culture.

Hippocampi were dissected from embryonic day (E) 16 rat embryos, as reported (9). In brief, isolated hippocampal progenitors were resuspended in Neurobasal medium supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin, glutamine, and the synthetic mixture B27 (NB/27) (Life Technologies) in the presence of FGF2 (20 ng/ml) and then plated on a poly l-lysine and laminin substrate (9). Two days after plating, 96% of the cells stained for nestin, an intermediate filament protein present in neural progenitors (12–14). Approximately 75% of the cells incorporated BrdUrd over 24 h, and no cells expressed the neuronal markers, MAP2B and Tau.

Immunocytochemistry.

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 5% goat serum in PBS, and the cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. Primary antibodies were incubated with the cells for 2 h at dilutions from 1:500 to 1:1,000. After washing three times for 5 min with 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS, the secondary antibody [Texas red-anti-mouse or FITC-anti-rabbit (1:500) (Molecular Probes)] was applied and incubated for 1 h, and the slides were washed as described above. Cell nuclei were counterstained with the DNA-binding dye 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Slides were mounted in Slowfade (Molecular Probes) and observed by fluorescence microscopy using a Zeiss Axioplan microscope.

Cell Counts.

Hippocampal progenitors were plated (10,000 cells/well) on poly l-lysine and laminin-coated eight-well slides (Becton Dickinson) in NB/B27 (see above) with FGF2 (20 ng/ml) for 2 days and treated with N-CAM (10 μg/ml) or BDNF (100 ng/ml) in fresh medium with or without added FGF2 for a further 8 days; media and additives were replenished every 2 days. Cell counts were determined with a Bauer's hemocytometer by using the Trypan blue exclusion test (15). Cell viability was 97–99%. On day 10, parallel cultures were fixed and immunostained. For each treatment, five randomly selected fields comprising at least 400 cells were counted for neural progenitors (nestin+), neurons (MAP2B+), and astrocytes (GFAP+), the numbers of which were expressed as a percentage of the total number of cells assessed by DAPI staining.

Differentiation and Characterization of Neuronal Phenotypes.

Hippocampal progenitors (15,000 cells/well) were plated in NB/B27 media with FGF2 on polyl-lysine and laminin-coated eight-well slides and grown for 4 days, with FGF2 and media added after 2 days of culture. On day 4, medium was replenished and cells were treated with N-CAM or BDNF and FGF2. Cells were cultured for an additional 10 days with media and additives replenished every 2 days. On day 14, cells were fixed and processed for immunocytochemistry for the antigens indicated in the text.

Microelectrode Arrays.

The techniques used to prepare microelectrode arrays (MEAs) have been described elsewhere (16, 17). The electrode array consists of a central 0.8-mm2 recording matrix of 64 microelectrodes. The hydrophobic surfaces of the MEAs were activated via butane flaming through a stainless steel mask, followed by application of polyd-lysine and laminin. Hippocampal progenitor cells were plated (10,000 cells/cm2 on MEAs and expanded with FGF2 for 4 days, with fresh media and FGF2 added after 2 days of culture. Cells were treated with N-CAM or BDNF in NB/B27 media with or without FGF2 for a further 4 days, and media were changed every 2 days. On day eight, cultures were incubated in NB/B27 with 2 mM glutamine and cultured for up to 3 weeks. No subsequent additions of FGF2, N-CAM, or BDNF were made. E18 primary hippocampal cultures were plated at a density of 80,000 cells/cm2 onto MEAs in DMEM supplemented with 5% FCS and 5% horse serum. After 1 week of culture, medium was changed to DMEM supplemented with 5% horse serum. One-half of the medium was exchanged every 4 days.

Extracellular Recording Procedures and Data Analysis.

MEAs were placed into constant-bath recording chambers (18) and maintained at 37°C on a microscope stage. The pH (7.4) was maintained with a continuous stream of filtered, humidified, 5% CO2 in air. Drugs at the concentrations noted in the legends and figures were added by pipette directly to the 1 ml of constant volume bath. Stock solutions were prepared so that sample volumes added never exceeded 2% of the total bath volume (for water-soluble compounds) or 0.2% (for DMSO-soluble compounds). Control applications of vehicle-only confirmed that these volumes did not change network activity.

Neuronal activity was recorded with a two-stage 64-channel amplifier system (Plexon, Dallas), and digitized simultaneously via a Dell 410 (Austin, TX) workstation. Total system gain was normally 20 K. Spike identification and separation were accomplished with a template-matching algorithm (Plexon) in real time to provide single-unit spike rate data. An experimental episode mean was obtained by averaging 1-min bin values comprising the time period from the addition of each pharmacological substance to the next manipulation (wash or drug addition). Significance was tested with a paired Student's t test. Mean spike traces were constructed by averaging 60-sec bins of activity from all recorded units. Burst identification was performed with a maximum interval algorithm to identify occurrences in unit spike trains when three or more consecutive spikes were separated by ≤33-ms interspike intervals. Burst rate traces were calculated by averaging individual burst rates/60 sec across all identified units.

Results

Effects of N-CAM and BDNF on Total Cell Counts and Generation of Neurons.

Although standard conditions for differentiating neural progenitors involve the removal of FGF2 (3, 4, 19, 20), we observed that cells grown in the presence of FGF2 in long-term culture appeared healthier, i.e., they were phase bright and extended more processes. We therefore tested the influence of FGF2, N-CAM, and BDNF on cell number from day 2 through day 10 of culture. Cultures grown in the presence of FGF2 yielded approximately three times as many cells as cultures grown without the mitogen (Fig. 1A). From these data, we calculated that when FGF2 is present, the progenitors have a doubling time of 1.7 days. Addition of N-CAM or BDNF to these cultures resulted in a slightly lower cell number in the presence of FGF2. In the absence of FGF2, the cell number remained constant under all conditions. These findings suggested that FGF2 supports cell proliferation even in the presence of N-CAM or BDNF.

Figure 1.

Effect of N-CAM and BDNF on total cell number and neuron generation. Cells were cultured as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Cell counts are the average ± SD from three experiments in duplicate. (B) The number of nestin+, MAP2B+, and GFAP+ cells at day 10 was determined by counting a minimum of 400 cells in five randomly selected fields.

To assess the types of cells present after 10 days in culture, the total number of progenitors (nestin+), neurons (MAP2B+), and astrocytes (GFAP+) were counted in cultures with or without treatment with FGF2 and neurotrophins (Fig. 1B). In the absence of FGF2, a small number of cells expressed astrocyte and neuronal antigens. Addition of either N-CAM or BDNF increased the number of neurons and decreased the number of progenitors. Overall, a similar trend was observed in the presence of FGF2, except that the total number of neurons and progenitors was greatly increased. The number of GFAP+ cells was similar in cultures with or without FGF2. Thus when hippocampal progenitors are cultured in the presence of FGF2, more neurons are generated, a greater number of progenitors are maintained, and, even in the presence of FGF2, N-CAM and BDNF effectively initiated differentiation of cells.

Characterization of Neuronal Subtypes Induced by N-CAM and BDNF.

We investigated whether adding either N-CAM or BDNF to progenitors gave rise to similar neuronal phenotypes. After 14 days, progenitor cultures differentiated in the presence of either N-CAM (Fig. 2) or BDNF (not shown) were immunostained with a variety of neuronal marker antibodies, the reactivity of which was consistent with the phenotype of neurons in the hippocampus in vivo (21–25). The differentiated neurons expressed the classical neuronal marker proteins MAP2B (Fig. 2 A, C, D, and F), neuron-specific enolase (NSE) (Fig. 2A), and Tau (Fig. 2B). Double-labeling experiments demonstrated that NSE and Tau were expressed in all MAP2B+ cells. Some of the MAP2B+ cells also expressed the neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (Fig. 2C) and its biosynthetic enzyme, GAD65/67 (not shown) as well as GluR2/3 (Fig. 2E), NR1 (not shown), and the GABAA receptor (Fig. 2D). The neuronal glutamate transporter EAAC1 was expressed and often colocalized with GluR2/3 (Fig. 2E). The presynaptic markers synapsin (Fig. 2F) and synaptotagmin (not shown) were detected in a subset of MAP2B+ neurons.

Figure 2.

Immunocytochemical staining of differentiated progenitors. Cells were cultured in the presence of N-CAM as described in Materials and Methods. After 14 days, cells were processed for immunocytochemistry for the antigens, as noted. D, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Development of Spontaneously Generated Action Potentials.

Morphological and immunohistochemical examination revealed that hippocampal progenitors differentiated into dense networks of cells that expressed characteristic neurotransmitters, receptors, and synaptic proteins. To determine whether these networks could fire action potentials and to examine the types of synapses formed, cells were cultured on MEAs in a variety of conditions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Culture conditions tested for spontaneous activity in progenitor-derived neuronal networks

| Condition | Spontaneous activity | Earliest evidence for spontaneous activity |

|---|---|---|

| 4-d FGF2 + 4-d FGF2 | No | Not detected at >30 days |

| 4-d FGF2 + 4-d N-CAM + FGF2 | Yes | 20 days |

| 4-d FGF2 + 4-d BDNF + FGF2 | Yes | 20 days |

| 4-d FGF2 + 4-d medium only | No | Not detected at >30 days |

| 4-d FGF2 + 4-d N-CAM | No | Not detected at >30 days |

| 4-d FGF2 + 4-d BDNF | No | Not detected at >30 days |

In all conditions, progenitors were initially expanded in the presence of NB/B27 supplemented with FGF2 (20 ng/ml) for 4 days, and then N-CAM (10 μg/ml) or BDNF (100 ng/ml) was added with NB/B27 in the presence or absence of FGF2 for 4 days to induce differentiation. Media were replenished every 2 days. After the initial 8-day culture period, cells were replenished with media containing NB/B27 + 2 mM glutamine. Spontaneous activity was demonstrated only in progenitor cell cultures differentiated with N-CAM or BDNF in the presence of FGF2, a response identified as early as 20 days in culture.

Elaborate networks of somata and processes were formed after 10–14 days under all conditions, but spontaneously generated action potentials were observed only in cultures initially differentiated with either N-CAM or BDNF in the presence of FGF2 (Table 1). Under all other culture conditions, activity could not be evoked by addition of glutamate, NMDA, bicuculline, or elevated potassium (not shown). Electrical activity was observed in progenitor-derived neurons at 21 days in culture (Fig. 3A). The emergence of activity in different cultures varied from 20 to 24 days. Once the activity emerged, however, it developed rapidly within 24–36 h, progressing from predominantly tonic uncorrelated activity to a higher frequency (0.5–50 Hz) phasic bursting pattern that appeared to involve the majority of units within the network (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Demonstration of spontaneous activity in networks of progenitor-derived neurons differentiated in the presence of N-CAM (A, B) and E18 hippocampal primary neurons (C, D) at comparable stages of in vitro development on MEAs. Vertical tick marks indicate spike times recorded from single neurons. Units of activity from separate electrodes in the MEA are displayed vertically, with A–D representing 45 s of activity in the horizontal axis.

E18 primary hippocampal neurons served as a control for activity development. In these cultures, spontaneous activity appeared after only 7 days of culture (Fig. 3C), and the firing frequency increased after a further 10–12 days (Fig. 3D), resulting in phasic bursting patterns resembling those in the progenitor cultures at day 22. Thus, although the activity of progenitor-derived neurons resembled that of cultures of differentiated neurons, it took longer to emerge. Progenitors passaged on plates or those first grown as neurospheres (26) both exhibited spontaneous firing (not shown).

The increase in bursting and spiking frequency was accompanied by a transition from immature action potentials (1.0–3.0 ms wide) (Fig. 4A Left) to mature action potentials (0.3–0.7 ms wide) (Fig. 4A Right) (27). Cross-correlograms of action potentials indicated that individual neurons in both populations were interconnected through mono- and polysynaptic pathways (Fig. 4B), providing further evidence of network interactions. The dependence of electrical activity on voltage-gated Na+ channels was shown by application of tetrodotoxin (1 μM), which inhibited all spiking (not shown).

Figure 4.

Maturation of action potentials in progenitor-derived neuronal networks. (A) Representative figure demonstrating changes in action potential shape in a culture differentiated with BDNF (100 ng/ml) in the presence of FGF2 (at 24 d in culture). Shallow broad action potentials characteristic of initial spontaneous activity (Left) change to faster more depolarized potentials within 24 h (Right). (B) Cross-correlograms were calculated from 1,400 s of spiking activity from four single units referenced to a fifth unit. The spiking activity reveals variable latencies in firing after the reference, consistent with both mono- and polysynaptic connectivity in different units in the MEA. Horizontal dash lines represent mean firing rate calculated for a Poisson spike train.

Pharmacological Characterization of Progenitor-Derived Neuronal Networks.

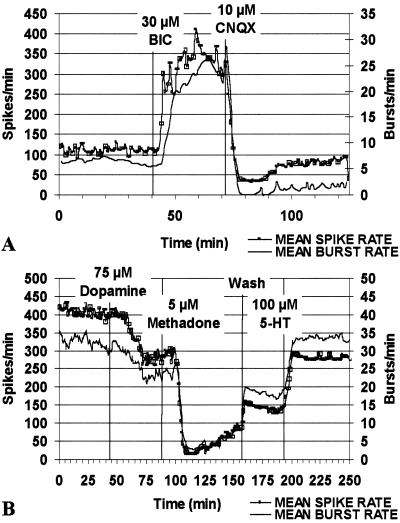

Cells were treated with receptor agonists and antagonists to determine further the types of functional synapses and neurotransmitter receptors present in the network. Antagonism of GABAA receptors with bicuculline increased activity, demonstrating the presence of functional GABAergic synapses (Fig. 5A). Subsequent application of the glutamatergic α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA)/kainate receptor antagonist CNQX produced a rapid decrease in both bursting and spiking patterns showing that AMPA/kainate glutamate receptors contributed to the spontaneous activity (Fig. 5A). TMPP increased spike activity (not shown), similar to that elicited by bicuculline confirming the presence of GABAergic synapses with GABAA receptors (28–30). Activity was increased in the presence of NMDA, which was reversed by the addition of the NMDA receptor-specific antagonist, 2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (APV), indicating the presence of NMDA receptors (not shown). Both APV and CNQX decreased the level of spontaneous activity, consistent with the contribution of both NMDA-type and AMPA/kainate-type glutamate receptors to the spontaneous activity.

Figure 5.

Spontaneous activity in progenitor-derived neuronal networks is mediated through inhibitory and excitatory synapses and is modulated by receptor agonists and antagonists. (A) Disinhibition with the GABAA antagonist bicuculline (30 μM, 42 min) elicited increases in network activity within 3 min, demonstrating the presence of functional GABAergic synapses. Application of the AMPA/kainate receptor antagonist CNQX (10 μM, 75 min) produced a rapid decrease in both bursting and spiking patterns, demonstrating the presence of glutamatergic synapses. Mean spike and burst rates were calculated from the activity of 23 single units in a culture differentiated with BDNF and FGF2 (at 28 d in culture). (B) Application of dopamine (75 μM, 50 min) or methadone (5 μM, 93 min) inhibited both bursting and spiking patterns, revealing the presence of dopaminergic and opioid receptors. Application of 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) (100 μM) caused an increase in burst and spike activity demonstrating the presence of serotonin receptors. Mean spike and burst rates were calculated from the activity of 33 single units in a culture differentiated with N-CAM and FGF2 (at 25 d in culture), as described above.

Further pharmacological characterization was done to explore other postsynaptic receptors expressed by progenitor-derived networks. Sequential application of dopamine and the μ-opioid agonist, methadone, decreased activity, revealing the presence of dopamine and opiate receptors, respectively (Fig. 5B). Some of the drug-induced suppression of activity was reversed after drug washout. Subsequent addition of 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) increased activity, indicating that functional serotonin receptors were present. Complex responses to carbachol, a nonhydrolyzable acetylcholine analogue, and its antagonists atropine and methyllycaconitine provided evidence of muscarinic and α7-nicotinic cholinergic receptors, respectively (not shown).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that hippocampal progenitor cells can differentiate into neuronal networks that exhibit spontaneously generated action potentials. Activity depended on the inclusion of FGF2 and either N-CAM or neurotrophic agents in the culture medium. N-CAM and BDNF appear equally efficacious in neural progenitor differentiation in terms of the numbers of neurons produced, the phenotype of neurons generated, and physiological activity of progenitor-derived neurons. In the presence of FGF2, the number of progenitors was significantly higher under all treatment conditions, suggesting that progenitor expansion may be limited by early removal of FGF2, a protocol often used in inducing differentiation of hippocampal stem cells (4, 19, 31–33). BDNF and N-CAM effectively promoted differentiation even in the presence of FGF2, recommending the inclusion of this growth factor during the culture of progenitors.

Our experiments demonstrate that cells derived from a population of neural precursors exhibit the characteristics of functional neurons in that the cells form excitatory and inhibitory connections that fire action potentials spontaneously. Action potentials were observed after 20 days in culture, depended on tetrodotoxin-sensitive Na+ channels, and were propagated by GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons. Progenitor-derived networks responded to a battery of pharmacological agents, suggesting that they expressed receptor populations representative of mature hippocampal neurons in vivo (21–25). Both passaged progenitor cells and cells grown in neurosphere cultures (26) produced active neural networks, indicating that proliferative progenitors gave rise to the networks and that networks did not arise via the selection for differentiated neurons in the primary cultures. Such progenitor-derived neurons may provide a suitable source of cells for toxicology applications (34) and should be particularly useful in further analyses of cellular and molecular events that are necessary and sufficient for the emergence of spontaneous activity.

The finding that FGF2 and either N-CAM or BDNF were required for the generation of spontaneous action potentials in progenitor-derived neurons suggests that critical signaling events are induced by binding of both growth factors and neurotrophins to their receptors. Previous studies in which FGF2 was removed before differentiation failed to reveal spontaneous activity (3, 4, 19, 20). In our studies, the number of neurons generated in the presence of FGF2 alone or with BDNF or N-CAM without FGF2 is sufficient to support network activity (35), but no such activity was observed. Whether the requirement for FGF2 is related to effects on signaling or to alterations in the proportion of neurons, astrocytes, and progenitors in the cultures requires further investigation.

The activity of networks derived from E16 progenitors was compared with that of networks derived from E18 hippocampal neurons. These E18 networks formed functional synapses that fired spontaneously within 7 days, consistent with previous studies (36–38). The onset of spontaneous activity in progenitor-derived networks was delayed by 10–14 days relative to the E18 networks. The maturation of activity, however, was accelerated in progenitor-derived networks compared with E18 cultures, developing in 2 versus 10 days, respectively. The differences in the time course of maturation of these two cultures may relate to the differential synthesis or insertion of receptor channels (39, 40), or to single-channel open probability (41–43) needed to convert existing synapses from a silent to a functional state (44). They may also relate to presynaptic mechanisms such as the number of docked vesicles (45). All of these parameters could be influenced by the different conditions and deserve subsequent study.

Although spontaneous activity arose when cells were treated with either BDNF or N-CAM together with FGF2, the addition of each of these agents alone was unable to produce networks that fired spontaneous action potentials. Moreover, in such cultures, activity could not be evoked with glutamate, NMDA, bicuculline, or elevated potassium levels, even though sodium channels were present. This finding is in apparent contrast to previous studies using embryonic rat hippocampal progenitors grown under different culture conditions in which spontaneous activity was not observed but in which activity could be evoked with glutamate agonists (3, 4). Evoked activity has also been reported in neurons derived from precursors from other central nervous system regions (4, 19, 31–33). Previous studies were performed at the single-cell level by using patch–clamp recordings (4, 19, 31–33) or with measurement of alterations in intracellular calcium levels (19, 20), as opposed to the MEAs used in the present study, which measured network activity from multiple cells. It is noteworthy that the percentage of cells capable of firing evoked action potentials in previous reports was highly variable. For example, only 6% of neurons derived from subventricular zone progenitors fired action potentials in response to current injection, whereas 64% of spinal cord-derived cells did so (31). Action potentials were elicited in 30% of neurons derived from adult hippocampal progenitors (33). Thus, different culture conditions and tissue sources can have profound effects on the electrophysiological responsiveness of neurons derived from stem cells in culture.

A number of factors may account for the different results observed among the present studies and the various in vitro studies cited here. These include differences in culture media, the use of serum-containing versus defined media (3, 4, 31, 33), the concentrations of neurotrophins (3), or the substrates used for cell attachment (3, 46). The conditions used in previous studies produced cultures in which the majority of neurons were either glutamatergic or GABAergic (3, 38), a condition that may not lead to an adequate balance of excitatory and inhibitory connections capable of producing spontaneously self-regulating neural networks. Moreover, the ratio of astrocytes to neurons differed among culture conditions. The metabolic function of astrocytes is known to be critical for synaptic development in vitro (47–49).

Our experiments suggest that interactions between growth factor and neurotrophin signaling may be important for the formation of electrically active neuronal networks. The present approach should prove useful for the further characterization of cues that allow progenitors to progress from neuronal-marker positive but electrophysiologically silent cells to spontaneously active neural networks.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anna Tran, Sarah Hutchinson, and Craig Frederickson for excellent technical assistance, Yvonne Park for excellent administrative assistance, and Drs. Elisabeth Walcott, Joseph Gally, Peter Vanderklish, and Frederick Jones for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service Grants HD09635 and HD16550, the Neurosciences Research Foundation, and a grant from the G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Foundation. S.K.M. is a Fellow of the Skaggs Institute of Chemical Biology.

Abbreviations

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- N-CAM

neural cell adhesion molecule

- MEAs

microelectrode arrays

- En

embryonic day n

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- CNQX

6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione

- FGF2

fibroblast growth factor 2

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- AMPA

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

References

- 1.Palmer T D, Takahashi J, Gage F H. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1997;8:389–404. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1996.0595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shetty A K, Turner D A. J Neurobiol. 1998;35:395–425. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19980615)35:4<395::aid-neu7>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vicario-Abejon C, Collin C, Tsoulfas P, McKay R D. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:677–688. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sah D W, Ray J, Gage F H. J Neurobiol. 1997;32:95–110. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199701)32:1<95::aid-neu9>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanaka T, Saito H, Matsuki N. Brain Res. 1996;723:190–195. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00245-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brewer G J. Exp Neurol. 1999;159:237–247. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freese A, Finklestein S P, DiFiglia M. Brain Res. 1992;575:351–355. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90104-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crossin K L, Krushel L A. Dev Dyn. 2000;218:260–279. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(200006)218:2<260::AID-DVDY3>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amoureux M C, Cunningham B A, Edelman G M, Crossin K L. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3631–3640. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03631.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sporns O, Edelman G M, Crossin K L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:542–546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krushel L A, Tai M-H, Cunningham B A, Edelman G M, Crossin K L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2592–2596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hockfield S, McKay R D. J Neurosci. 1985;5:3310–3328. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-12-03310.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lendahl U, Zimmerman L B, McKay R D G. Cell. 1990;60:585–595. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90662-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stemple D L, Anderson D J. Cell. 1992;71:973–985. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90393-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allison D C, Ridolpho P. J Histochem Cytochem. 1980;28:700–703. doi: 10.1177/28.7.6156203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gross G W. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1979;26:273–279. doi: 10.1109/tbme.1979.326402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gross G W, Wen W Y, Lin J W. J Neurosci Methods. 1985;15:243–252. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(85)90105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gross G W. Enabling Technologies for Cultured Neural Networks. San Diego: Academic; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalyani A J, Piper D, Mujtaba T, Lucero M T, Rao M S. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7856–7868. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-19-07856.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma W, Maric D, Li B S, Hu Q, Andreadis J D, Grant G M, Liu Q Y, Shaffer K M, Chang Y H, Zhang L, et al. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:1227–1240. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blozovski D, Hess C. Behav Brain Res. 1989;35:209–220. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(89)80142-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gurevich E V, Kordower J H, Joyce J N. J Chem Neuroanat. 2000;20:307–325. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(00)00108-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pasqualetti M, Nardi I, Ladinsky H, Marazziti D, Cassano G B. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1996;39:223–233. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(96)00026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snyder E W, Shearer D E, Dustman R E, Beck E C. Psychopharmacology. 1979;63:89–95. doi: 10.1007/BF00426927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Zee E A, Matsuyama T, Strosberg A D, Traber J, Luiten P G. Histochemistry. 1989;92:475–485. doi: 10.1007/BF00524759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reynolds B A, Weiss S. Science. 1992;255:1707–1710. doi: 10.1126/science.1553558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shepherd G M. Neurobiology. New York: Oxford; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins G M, Gardier R W. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1990;105:103–112. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(90)90362-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kao W Y, Liu Q Y, Ma W, Ritchie G D, Lin J, Nordholm A F, Rossi J, 3rd, Barker J L, Stenger D A, Pancrazio J J. Neurotoxicology. 1999;20:843–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keefer, E. W., Gramowski, A., Stenger, D. A., Pancrazio, J. J. & Gross, G. W. (2001) Bioelectrochem. Bioenerg., in press.

- 31.Liu R H, Morassutti D J, Whittemore S R, Sosnowski J S, Magnuson D S. Exp Neurol. 1999;158:143–154. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma W, Liu Q-Y, Maric D, Sathonoori R, Chang Y-H, Barker J L. J Neurobiol. 1998;35:277–286. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19980605)35:3<277::aid-neu5>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toda H, Takahashi J, Mizoguchi A, Koyano K, Hashimoto N. Exp Neurol. 2000;165:66–76. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stenger D A, Gross G W, Keefer E W, Shaffer K M, Andreadis J D, Ma W, Pancrazio J J. Trends Biotechnol. 2001;19:304–309. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(01)01690-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rhoades B K, Gross G W. Brain Res. 1994;643:310–318. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fletcher T L, De Camilli P, Banker G. J Neurosci. 1994;14:6695–6706. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06695.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matteoli M, Verderio C, Krawzeski K, Mundigl O, Coco S, Fumagalli G, De Camilli P. J Physiol (Paris) 1995;89:51–55. doi: 10.1016/0928-4257(96)80551-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vicario-Abejon C, Collin C, McKay R D, Segal M. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7256–7271. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-18-07256.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liao D, Scannevin R H, Huganir R. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6008–6017. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-06008.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roovers K, Davey G, Zhu X, Bottazzi M E, Assoian R K. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3197–3204. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.10.3197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levine E S, Crozier R A, Black I B, Plummer M R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10235–10239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jarvis C R, Xiong Z G, Plant J R, Churchill D, Lu W Y, MacVicar B A, MacDonald J F. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:2363–2371. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.5.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levine E S, Kolb J E. J Neurosci Res. 2000;62:357–362. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20001101)62:3<357::AID-JNR5>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ben-Ari Y, Khazipov R, Leinekugel X, Caillard O, Gaiarsa J L. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:523–529. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Collin C, Vicario-Abejon C, Rubio M E, Wenthold R J, McKay R D, Segal M. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:1273–1282. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vicario-Abejon C, Johe K K, Hazel T G, Collazo D, McKay R D. Neuron. 1995;15:105–114. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ullian E M, Sapperstein S K, Christopherson K S, Barres B A. Science. 2001;291:657–661. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5504.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pfrieger F W, Barres B A. Science. 1997;277:1684–1687. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nagler K, Mauch D H, Pfrieger F W. J Physiol. 2001;533:665–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]