Abstract

Background

Population ageing and rising levels of non-communicable diseases are increasing the number of people living with and dying from advanced serious illnesses globally. Many of these people are hospitalised more than once in their last year of life. While there is sound evidence on what patients and their families require for safe and high-quality hospital palliative care, enabling this remains a challenge. This study aimed to understand the clinician, team, and organisational-level barriers and enablers to integrating good palliative care into acute care.

Methods

An exploratory-descriptive, qualitative study involving semi-structured interviews and practical thematic analysis was conducted. Medical, nursing and allied health disciplines were recruited from three wards (cancer care, mixed general medicine/renal and mixed general medicine/respiratory) within a large Australian metropolitan hospital.

Results

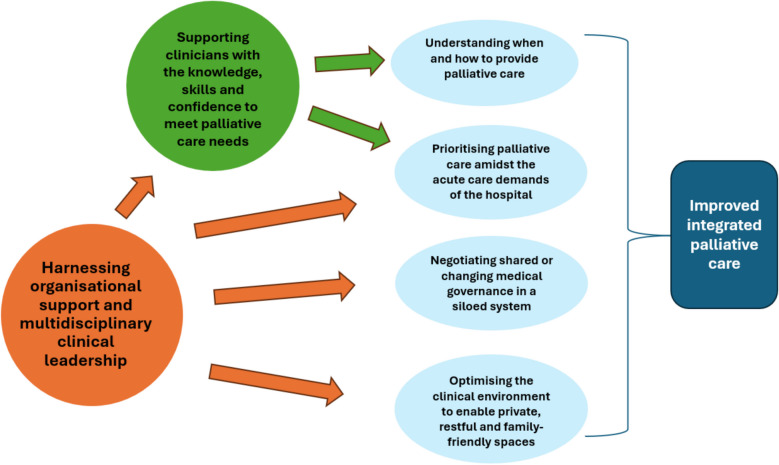

Eighty-eight interviews (nursing (n = 39); medicine (n = 24); allied health (n = 25)) were undertaken, with a median duration of 25.5 min (range 5 to 55 min). Most participants were female (n = 73, 83%), holding a Bachelor's degree (n = 86, 98%) and ranged from new graduates to participants with over 40 years of post-registration experience. The analysis generated six themes, reflecting the challenges of providing optimal palliative care within acute hospital wards:

1. Understanding when and how to provide palliative care

2. Negotiating shared or changing medical governance in a siloed system

3. Supporting clinicians with the knowledge, skills and confidence to meet palliative care needs

4. Prioritising palliative care amidst the acute care demands of the hospital

5. Optimising the clinical environment to enable private, restful and family-friendly spaces

6. Harnessing organisational support and multidisciplinary clinical leadership

Conclusions

This study reveals complex, multi-level organisational barriers to integrating palliative care within the acute hospital which will need to be addressed for effective and sustained improvement. Harnessing organisational support and multidisciplinary clinical leadership is key to successful change. Improvements with a focus on developing clinician knowledge, skills, and confidence in palliative care need to pay attention to organisational siloes that constrain shared care, cultures of care that prioritise cure and efficiency, clinical uncertainty in the context of advanced serious illness and optimising the environment for quality palliative care.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12904-025-01815-1.

Keywords: Palliative care, Terminal care, Hospital, Quality improvement, Qualitative research, Multidisciplinary care, Acute hospital care, Implementation

Introduction

Globally, the number of people living with and dying from advanced serious illness continues to increase due to the rise in the ageing population and non-communicable illnesses [1]. In the last 12 months of life, individuals with advanced serious illness (patients with palliative care needs) experience high levels of hospitalisation relating to medical exacerbations of their disease [2, 3]. The hospital setting plays a vital role in palliative care [4, 5]. However, aligning care delivery to meet the needs for safe and high-quality care from the perspectives of patients and their families remains an area for improvement [6–11]. A practice model that enables optimal palliative care for inpatients in their final year of life is of significant interest globally [2, 4, 12].

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines palliative care as: “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients (adults and children) and their families who are facing problems associated with life-threatening illness. It prevents and relieves suffering through the early identification, correct assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, whether physical, psychosocial or spiritual” [13]. That is, palliative care focuses on optimising quality of life within the context of advanced serious illness [13]. It is not disease-specific nor prognosis-dependent [13]. Within the Australian context, the national strategy references this same definition and highlights access to quality care across all settings as a key guiding principle for health care delivery [14]. The Australian Government Department of Health states that “palliative care is for people of any age who have been diagnosed with a serious illness that cannot be cured” [15] with this manuscript adopting the terminology of advanced serious illness to describe the patient population of focus. However, exactly how quality care for people with advanced serious illness should be operationalised remains unclear, with the default describing palliative care as care provided by specialist palliative care services [16]. Most Australians dying from an expected death do not access specialist palliative care and those who do, mostly do so in the last few weeks of their life [16]. Within Australia, hospitals remain the setting where most people with palliative care needs die, [17] while policy reform continues to focus on increasing resourcing and support within the primary care setting. [16] Designated and detailed policy to support integrated care for people with advanced serious illness receiving care within the Australian acute care context is lacking. [18] This is important given the complexity of needs at this time and the multiple clinicians involved in advising or guiding care planning and provision [10].

Optimising quality of life where diagnostic and prognostic uncertainty exists for inpatients with advanced serious illness is challenging [5, 19, 20]. Clinicians must simultaneously balance the need for acute medical interventions to manage disease exacerbation/progression and symptoms whilst ensuring sufficient attention to planning for deterioration and potential death [19–21]. Supporting clinical teams to enable such care is complex due to the focus on physical biomedical needs within the acute care environment, [20, 22, 23] the lack of resourced structures, systems and processes to prioritise complex communication, [5, 20, 24] and the varied understandings of how to integrate with specialist palliative care services [25, 26]. Globally, integrating palliative care for inpatients with advanced serious illness and acute medical deterioration remains a key area for improvement [4, 5, 8, 10].

It is crucial to precisely define the term'integrating palliative care,'as the terminology related to palliative care, end-of-life care, supportive care, and terminal care is applied inconsistently across different countries [27, 28]. In this paper, palliative care is defined in accordance with the WHO definition [13] and terminal care is the terminal phase of care, where death is likely within days [29, 30]. Specialist palliative care (SPC) is defined as care provided by clinicians with specialist skills in this field [31]. Integrated palliative care refers to enabling palliative care in practice for all inpatients living with advanced serious illnesses [32]. This concept is relevant to multiple clinical disciplines including those working in a wide range of specialties, as well as those working in SPC. Whilst sharing many similar attributes, integrated palliative care differs from supportive care which is defined as inclusive of care for those with early stage disease and survivorship concerns in addition to those with advanced disease and into bereavement [27].

A recent international Delphi study to define core indicators for hospital-based palliative care highlighted the multidisciplinary nature of effective palliative care delivery and the importance of structural, organisational and clinician factors to support multi-level integration [4]. These indicators clarify roles for all clinicians working with patients who have palliative care needs and opportunities to strengthen integration with SPC services [4]. However, it was noted that implementing integrated palliative care for inpatients is poorly described and understood and is a key research priority [4].

As part of a larger multi-methods improvement study that aimed to empower clinicians to understand and improve inpatients'experience of palliative care, we sought to understand the barriers and enablers at the clinician, team and organisational levels to integrate good palliative care into the acute care setting from the perspectives of multidisciplinary acute care clinicians.

Methods

Design and theoretical approach

This qualitative study was undertaken as part of the first phase of a larger mixed-methods project evaluating the effect of a complex intervention that included collection and feedback of patient experience data and facilitation to empower ward-based quality improvements for inpatients with advanced serious illnesses. The project was underpinned by the integrated Promoting Action on Research in Health Services (i-PARIHS) implementation framework, which proposes that successful implementation is a function of the change (innovation), people involved in the change (recipients), and context (setting), enabled by active facilitation [33]. i-PARIHS has been widely used to help plan, implement and evaluate complex multidisciplinary improvements in healthcare [33].

An exploratory-descriptive, qualitative approach using semi-structured interviews and practical thematic analysis was employed to obtain an in-depth understanding of the context from the clinician's perspective, informing subsequent phases of the research [34–36]. Pragmatism informed the study design, prioritising the exploration of varied viewpoints (different acute specialties and clinical disciplines) to inform practical outcomes for clinical change [34, 37–39].

Setting and participants

Setting

The study was undertaken in a large Australian publicly funded tertiary referral hospital in a metropolitan setting. Eligible participants were recruited from three wards (cancer care, mixed general medicine/renal and mixed general medicine/respiratory) selected because they provide acute clinical care for large numbers of patients with advanced serious illnesses. A health-service funded specialist palliative care team composed of medical and nursing specialists is available for consultative advice relating to complex palliative care needs for inpatients with advanced serious illness. Referral to this consult service occurs via medical specialists.The weekday (Mon-Fri) SPC service also provide after-hours on-call support and provide regular education for multidisciplinary clinicians across the hospital (mentorship, inservices and professional education days). On one of the wards, a collaborative renal supportive care service is also available, comprising nephrology and specialist palliative care medical and nursing specialists. The hospital has adopted a multidisciplinary care plan for the dying person which is commenced once a medical decision that the patient is dying is formally made. This care plan aims to provide guidance for high quality terminal care tailored to individual need inclusive of: medication rationalisation, pre-emptive prescription of symptom management medications, confirming advance care planning documentation, optimising communication (patients, families and multidisciplinary team), personalising care (spiritual, cultural), reviewing assessments and interventions and care after death. Each participating ward has a mix of 4-bedded shared rooms with one bathroom per room and a small number of private rooms with en-suite facilities prioritised for patients with infectious conditions, terminal care, or other unique care needs.

Participants

Eligible participants included clinicians or clinical managers from medical, nursing and allied health disciplines working within the participating wards, including:

Nurses employed within the participating wards.

Medical consultants and the junior doctors (PGY 1–7) they support. The junior doctors were allocated to the participating wards rotating every 2–6 months.

Allied health professionals aligned with the participating wards, including more junior team members who rotate between clinical specialties every 6–12 months.

Research team

A nurse researcher with palliative care and qualitative research expertise (CV) conducted all interviews, and the analysis was supported by a team of experienced researchers with clinical (oncology, palliative care, internal medicine), implementation and qualitative research expertise. The principal researcher maintained a reflexive journal after each interview and throughout analyses, which informed team discussions to support rigour and clarify any areas requiring consensus to support coding, categorisation and theming work [34, 40, 41].

Recruitment

Clinicians and clinical managers from participating wards were invited to participate in this study through in-person communication by the project team at regular ward meetings and emails from clinical managers. Two email reminders were sent (each 1–2 weeks apart), after which time a non-response was assumed. For those who expressed interest in participation, a member of the research team provided an information sheet and offered further discussion about the study. Written consent was obtained prior to participation in the interview.

Data collection

Data collection took place from June to November 2022. Semi-structured interviews were conducted during working hours in a private room or via phone. The interview guide was aligned with the i-PARIHS constructs of recipients (e.g. values and beliefs, learning environment, professional boundaries) and the local and organisational context (e.g. leadership, past experience of change, history of innovation, culture) (Refer to Table 1).

Table 1.

The semi-structured interview question guide

| 1. Can you tell me about your current clinical position and why you have chosen to participate in this study? |

| 2. Does your current role lead in the care for people with palliative care needs frequently, or not so much? |

| 3. Do you see palliative care as part of your role? |

| 4. Could you explain to me what your view is of someone with palliative care needs? |

| 5. Throughout your career, have you received any specific training (formal or informal) in relation to palliative care? |

| 6. In an ideal world, what would best care look like for people with serious illness? |

| 7. Thinking about your ward area, do you feel there are any areas of palliative care provision that could be improved? |

| 8. What makes it hard to provide good palliative care in your ward? Prompt here in relation to identified areas for optimal care |

| 9. Can you tell me about any previous improvement experience you have? Prompt re prior project work |

| 10. Do you believe you can lead in improvements within your ward? What resources do you need to enable this? |

Descriptive demographic data included age, gender, professional role, highest level of education and years of clinical registration. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and field notes were taken.

Data analysis

This study applied an integrated thematic analysis approach using recently described methods of ‘practical thematic analysis’ [35, 36]. This approach was chosen as findings were primarily intended to inform context-sensitive improvements in practice. Analysis included data immersion, coding, categorisation and generation of themes, integrating both deductive and inductive methods. The coding team (CV, GS and AM) read through all interviews from the first ward to familiarise with the data, and independently coded three transcripts, extracting data relevant to the research question and assigning it to codes from an existing i-PARIHS qualitative analysis codebook [42]. The i-PARIHS codebook was developed by experts in both qualitative methods and implementation science [42] to provide clarity about the key i-PARIHS constructs (innovation, context, recipients, facilitation activities). This focusses researchers on conceptually meaningful codes aligned to foundational constructs that inform successful change [42]. Through regular discussion of the data, this generic codebook was iteratively adapted to the project and applied by two coders (CV, GS) to each ward’s complete dataset within Microsoft Excel (ongoing integrated coding). The coding team met after coding each ward’s dataset to resolve any discrepancies, review example quotes for each code and discuss overarching concepts and meanings. Codes and selected illustrative quotes were summarised into tables for each ward by CV, and the coding team members compared across wards to develop draft themes, which were iteratively developed and refined through two structured discussions into shared themes. The entire research team then reviewed the summary findings. Supplementary Table 1 provides a detailed overview of the analysis steps.

Ethical issues

Ethical approval was granted by Townsville Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee in May 2022 with reference number HREC/2022/QTHS/84709. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed written consent was obtained from each interview participant. Transcripts were deidentified for analysis.

Reporting

The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) [43] informed reporting of results.

Results

Eighty-eight interviews were undertaken (nursing – 39; medicine – 24; allied health – 25), with a median duration of 25.5 min (range 5 to 55 min). Two allied health professionals worked across two wards, so data were available from 33 participants on ward 1, 28 on ward 2 and 29 on ward 3. Table 2 provides descriptive details of the participants. Participants were mostly female (n = 73, 83%), well-educated (n = 86, 98% with Bachelor degrees and n = 22, 25% with additional Masters or PhD qualifications) and represented broad experience levels from new graduate through to over 40 years since registration. Of 39 nurses, one was an assistant, 28 were registered nurses (12 with higher duties such as nurse specialist or nurse consultancy roles), 4 were nurse educators, 4 were nurse unit managers and two were nursing directors. Of 24 doctors, 12 were consultants, 7 were registrars (vocational trainees) and 5 were interns or junior house officers (prevocational trainees). The 25 allied health professionals included 7 physiotherapists, 5 occupational therapists, 4 pharmacists, 4 social workers, 3 speech pathologists and 2 dietitians.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant numbers | Ward 1 | Ward 2 | Ward 3 | TOTAL |

| 33 (37) | 28 (31) | 29 (32) | 88a (100) | |

| Median age (range) | 36yrs | 31.5yrs | 35yrs | 34yrs |

| (24-64yrs) | (25 −63yrs) | (23-63yrs) | (23-64yrs) | |

| Female, n (%) | 29 (88) | 24 (86) | 20 (69) | 73 (83) |

| Discipline, n (%) | ||||

| Nursing | 16 (49) | 11 (39) | 12 (41) | 39 (44) |

| Medicine | 7 (21) | 8 (29) | 9 (31) | 24 (27) |

| Allied health professional | 10 (30) | 9 (32) | 8 (28) | 25 (29) |

| Median years of clinical | 9yrs | 8yrs | 12yrs | 9yrs |

| experience, n (%) | (2—42yrs) | (1—39yrs) | (0.5–46yrs) | (0.5–46yrs) |

aTwo allied health professionals contributed interview data pertaining to two wards (wards 2 and 3)

When reporting data that is representative of all included disciplines (nursing, allied health professionals and medicine), the term ‘participants’ will be used. Where one discipline contributed unique perspectives, they will be noted by their respective discipline.

The analysis generated six themes that describe the challenges and opportunities for improving integrated palliative care within acute hospital wards:

Understanding when and how to provide palliative care

Negotiating shared or changing medical governance in a siloed system

Supporting clinicians with the knowledge, skills and confidence to meet palliative care needs

Prioritising palliative care amidst the acute care demands of the hospital

Optimising the clinical environment to enable private, restful and family-friendly spaces

Harnessing organisational support and multidisciplinary clinical leadership

Theme 1—Understanding when and how to provide palliative care

Participants described the challenge of providing palliative care within the hospital setting in relation to a lack of understanding about what palliative care is. This impacted their ability to optimise care both within the context of clinical uncertainty and outside of the biomedical focus.

Preconceived ideas about palliation

Although many participants were able to provide a broad definition of palliative care consistent with the WHO definition, [13] they noted that their actual clinical practice reflected a focus mainly on referral to SPC and/or terminal care. Palliative care also seemed to be synonymous with care provided by the SPC service, although participants rarely used the term “specialist” palliative care.

It’s good to link them in early but most of the time I feel like our practice has been to refer when someone is dying imminently as opposed to planning in advance if that makes sense. (Ward 3, Medical 3, with 1 year experience)

Participants also noted that patients and families often equated palliative care with terminal care, which may be reinforced by clinician perceptions that palliative care refers solely to input from SPC clinicians or terminal care provision.

And some patients don’t want to be involved in palliative care because they have this thought around it being that they’re about to die when clearly palliative care offers a lot more than that terminal phase of life … And so I think then there’s those pre-conceived ideas around palliation and I think we just need to change all of that. (Ward 1, Nursing 12, with 27 years’ experience)

Navigating the ‘grey zone’ of care provision prior to a specialist palliative care referral

Medical and nursing participants expressed the challenges of enabling optimal care when the goals of care are not clear and patients are still receiving active therapy within the context of advanced serious illness. This led to clinical teams feeling powerless to address suffering and unclear about when referral to specialist palliative care may be appropriate.

… it’s distressing to both me and my residents [medical team members] when we see patients are suffering and we feel powerless to get the palliative care team involved or we are stuck in the grey zone... it’s when they’re stable but they’re badly stable where we know we feel this is not going in the right direction but we feel a bit powerless and we don’t know whether to just keep treating them actively or get palliative care involved earlier. (Ward 1, Medical 7, 4 years experience)

And it’s always navigating that grey space of someone coming in acutely unwell and you know having sort of active management and several MERTS (medical emergency responses) and all these sorts of you know sometimes futile but still attempted interventions to sort of have some sort of positive outcome before there was a trigger to actually engage palliative care which was often sort of at the last minute. (Ward 2, Nursing 10, with 8 years experience)

Medical consultants deciding to lead palliative care provision without SPC input led to discomfort and uncertainty by other health professionals on the ward.

I feel like sometimes I palliate someone and then I just want to see how quickly they’re deteriorating or not and there’s always a lot of anxiety from the ward. Like they want me to I guess it comes from nursing staff they want me to refer to palliative care whereas sometimes I think like this is really uncomplicated, they’re comfortable I don’t think we actually need to refer to palliative care. (Ward 2, Medical 3, with 9 years experience)

Nurses often described their need to advocate for earlier decision making with the treating team, because only the medical team can refer to SPC, and often felt powerless to progress this. Some suggested that shared prognostic tools might help to navigate clinical uncertainty (termed as the ‘grey zone’ by participants) more effectively.

I just feel like if there was you know I don’t know some kind of tool you know that we could use and we could use as evidence in a way like something that gave us some kind of not just subjective but you know something that was a bit more I don’t know just evidence. That we could say you know these things are happening tick, tick, tick, tick you know we need to start looking at you know palliative type options and be doing something better for this patient. Because what we’re doing now is not great (Ward 1, Nursing 13, with 9years experience)

Getting terminal care right is a high priority for clinical teams but a focus on procedural and physical care is noted

Participants described taking pride in advocating for and providing good terminal care. Nursing participants noted particular attention is paid to nursing team allocation to optimise care.

… I think it’s a big part of what we do and I feel like a lot of or I’d say the majority of the nurses take a lot of pride in how we are with palliative care patients and trying to what I was talking about before like trying to give really dignified deaths on the ward. (Ward 1, Nursing 1, with 14 years experience)

Quite often if someone is very end of life and they have a rapport with the other nurse rather than swapping all the time you just say right you focus on that one, you’ve got a rapport going with the family you know the patient and I’ll pick up the slack elsewhere. (Ward 3, Nursing 4, with 21 years experience)

However, when discussing terminal care, participants noted concerns about the tendency to focus primarily on procedural and physical aspects of care whilst not providing adequate attention to psychosocial aspects of care and support.

I think a lot of people just do like the two-hour plan thing and the Niki and that’s all that they think of as palliative care as a regular thing. But I reckon there could be more responsibilities and more roles that people could play a part in. (Ward 2, Nursing 8, with 7 years experience)

The perceived need for a patient to have commenced on the care plan for the dying person ahead of enabling optimal palliative care was described, and care provision was linked with response to symptom distress specifically, rather than holistic person-centred care.

… obviously our nurses are really our eyes and ears in all of this because we’re not there all the time. I think they are over all fairly attuned to the signs of physical distress but I think there probably is some reluctance to manage symptoms before we get to the care plan of the dying patient and so on. I think that really sort of signals you know a change in how we’re doing things that helps the nursing staff and empowers the nursing staff I think to use the tools that we’ve got which is largely medications unfortunately I guess. (Ward 3, Medical 4, with 16 years experience)

Theme 2—Negotiating shared or changing medical governance in a siloed system

Operationalising shared care

Doctors noted that the specialist palliative care service was helpful and responsive in optimising inpatient palliative care, coordinating complex discharges and providing proactive patient follow up. They also valued the emotional support provided when care can be distressing.

I think I actually like the palliative care service here I think it’s great. I think that they’re proactive you know so they’ve obviously got like some way of flagging that if a patient’s known to them in the community that sometimes they’ll see the patients before we even see them in the Emergency Department. So they’re a proactive team. They provide very helpful suggestions. They seem to have pretty good availability and certainly if something’s urgent then they’ll be able to give us good and timely advice. (Ward 1, Medical 2, with 6 years experience)

However, some doctors also identified the importance of continuity of care from the physician teams within the context of advanced serious illness, both due to their established relationships and the need for disease-specific expertise.

I don’t like the idea of a patient becoming you know essentially no longer treatable and leaving their care to palliative care so like a complete step down of one team to another. I like more of an integrated model and on Ward 1 it works kind of well and also painfully that palliative care don’t have in-patients so I guess it does kind of foster that relationship of you staying with the team that’s known you best for the longest but palliative care do a lot of the in-patient management. So that kind of works well but it can also be quite an imposition when you’re seeing a patient and having very little input you’re more there just for the sake of being a figure head. (Ward 1, Medical 3, with 7 years experience)

The complexity of this shared responsibility led to tensions regarding the specific roles and responsibilities within the shared care model, which were noted by the other clinical specialities.

… the issue really is that palliative care are only a consult service and for a lot of people who have been in the system for a long time consult service means you consult which means you give advice but you don’t actually do that…Palliative care in this hospital don’t really operate like that and that is partly because most other teams in the hospital are quite happy with that …A lot of our consultants feel that they should just come in, give advice but not actually do it whereas the palliative care team often do do it and that has caused some angst in the past as well. (Ward 1, Medical 4, with 26 years experience)

Participants proposed novel models of integration, including the co-location of services, the co-location of beds, and the direct alignment of a palliative care physician with each specialty service.

I actually think we should have a palliative care person that works for us… I feel like if we employed a palliative care person I’m not sure how that would work with them and the palliative care team but I think if we felt like they were part of our team and they had some understanding of where we were coming from more… It would mean also that we would be more likely to reach out for advice and those sorts of things. (Ward 1, Medical 4, with 26 years experience)

Participants suggested a range of changes to work practices to support shared care including joint visits, joint rounds or explicit integration of palliative care into multidisciplinary team meetings.

I think that it would work better if you know the teams were integrated a bit more like time permitting you know seeing patients who are in that more sort of palliative phase together on ward rounds with medical oncology and also palliative care I think would be very, very useful. (Ward 1, Medical 2, with 6 years experience)

Most participants specifically noted complexity due the absence of designated specialist palliative care inpatient beds for patients transitioning to terminal care. Many participants noted that this led to either unnecessary transfers of patients to other facilities or to unnecessarily complex shared care arrangement where the coordinating unit no longer contributed to care decisions:

I guess the difficulty with palliative care here at [Hospital X] is that they don’t have admitting rights. We don’t have a specific palliative care unit so any patient that is deemed to be palliative you know we can palliate them here at [Hospital X] but sometimes we transfer them to another palliative care unit so that can be you know you don’t want it to be unsettling things for them in their last days and things. (Ward 3, Nursing 5, with 25yrs experience)

it’s actually quite tricky sometimes there are some patients who are obviously palliative, who obviously should be being looked after by the palliative care service but they don’t have the beds here and the patient’s too sick to move elsewhere. So there are some patients where we’re sort of babysitting them really but the palliative care team are looking after them. (Ward 1, Medical 4, with 25 years experience)

Some nurses recognized that ward co-located palliative care beds could offer opportunities to maintain nursing continuity of care for inpatients who had received care on their wards often over several years. Such a model enables the team to focus on the intent for care and prioritise such care provision within a busy acute care environment. They also recognsied that it could improve nursing skills by working alongside specialist palliative care more often:

… I’d love to have four palliative care beds attached to our unit because what happens is we look after our patients for years and they come backwards and forwards. We get to know a lot of them and they get to know the nurses and you know when they walk in it’s like hi, hello no matter how sick they are they get to know the team. And then so many of our patients have a period of acute care with us before they actually decline and then if they don’t have a rapid decline and miss the opportunity to be transferred to a palliative care unit they want to die with us. They’ve had the same team, the same nurses all along they don’t want to be sent off to a palliative care unit. (Ward 1, Nursing 10, with 42yrs experience)

Obviously palliative care doesn’t have beds in this hospital…I’d be happy for that to be part of my specialty kind of thing. I think that would be an improved outcome I think if you had more involvement with the palliative care doctors and team all the team you’d probably learn a lot. (Ward 3, Nursing 1, with 28yrs experience)

Theme 3—Supporting clinicians with the knowledge, skills and confidence to meet palliative care needs

Education and mentorship to enhance confidence in palliative care

Participants spoke about their desire and need for education and support to enable improved confidence in palliative care provision, particularly in relation to having difficult conversations and establishing goals of care. Allied health clinicians also noted their need to better understand how the multidisciplinary team can best work together. Participants noted challenges with prioritising learning within busy clinical workloads, meeting the needs of rotational staff with varied experience and learning needs, inclusive of new graduate nurses.

I would definitely say I don’t feel skilled in the palliative care sector and I don’t know if many of my colleagues would. We have a lot of new graduates in the medical case load so they’re just trying to get on top of their own profession but yeah I don’t think there’s a lot of education about it all. (Ward 2, Allied health 7, with 4 years’ experience)

Grads it’s something that scares them and they still are scared because they know that its coming… and when we run our transition programs it is something that they consistently bring up as something that does worry them. About what am I going to do? How am I going to make that person feel safe? And how do I deal with conversations of palliative care with my patients when they’re asking me things that maybe I don’t feel confident about? But also how do we advocate for our patients? How do we explain palliative care to them? Like how do they get educated on palliative care when we don’t know palliative care? (Ward 1, Nursing 8, with 9 years’ experience)

Clinical mentorship was recognised as important for enabling skill development in palliative care. Nurses highlighted the value of learning on the job in relation to complex communication with patients and families and advocating for optimal care.

… plus my senior nurse always mentioned when I was like a junior if you do not have any confidence, if you do not very feel comfortable to go and talk to any palliative patient or like any family members they always take a part and then I can watch on to you know sort of like their conversation. And now I’ve learnt a lot from what I’ve seen so that I can now like you know go and talk to the patient or even family with a bit of confidence. (Ward 1, Nursing 4, with 4 years’ experience)

Some participants also recognised the need for staff support.

But I think also that staff self-care education is important not for neglect as well because it’s a very confronting area to work in… So I think a part of that education process around what is palliative care, how do we also look after our staff and make sure that we’re in the best mind set to provide the best care if that makes sense. (Ward 1, Allied health 10, with 14 years’ experience)

Clarity about the role of specialist palliative care

Junior doctors articulated a need for more guidance and support in when and how to engage with specialist palliative care clinicians. They specifically described needing to understand the different informational priorities for specialist palliative care clinicians and how integrated care works in practice.

…like in the beginning it was quite tricky just knowing who to refer to, what [specialist] palliative care cares about, what [specialist] palliative care doesn’t care about in terms of patient progress and stuff. Because I remember distinctly on my surgical term I had to change the way that I talked to [specialist] palliative care doctors versus the way I was talking to my surgical team. Because obviously they had different competing priorities which as the intern you sort of have to know everything and then you have to relay that information to the nurses who are looking after them. So I found that quite challenging. (Ward 3, Medical 6, with 1 year experience)

Allied health clinicians also requested greater clarity about the role and team composition for specialist palliative care, how to access their expertise and share information:

I don’t know who the palliative I know some of the doctors but not all of them and so therefore wouldn’t know who to approach or ask for help or ask questions to. And even their notes maybe they provide more description on what they think the patient might need for comfort rather than it just being managing pain with medication. Because I know that they have a nurse that also comes around. I don’t know if they have an allied health person in their team. (Ward 2, Allied Health 1, with 2 yrs experience)

Theme 4—Prioritising palliative care amidst the acute care demands of the hospital

Balancing clinical priorities within acute care

Participants spoke about the complexity of prioritising patients with predominantly palliative care needs whilst also prioritising the care needs of patients requiring a curative approach. Participants noted that patients with palliative care needs are often prioritised less than patients who are clinically unstable, new admissions or ready for discharge.

… you know you get pulled in a lot of different directions and I guess when, as much as I hate to say this but if the palliative care patient is comfortable and they’re pain free and they have their family there you will have to concentrate on the acute patient that is unstable. So I suppose if you could just concentrate more on them I suppose and just not be pulled in so many directions but I guess that’s just like it is … (Ward 1, Nursing 1, with 14 years’ experience)

Like everything happens, we have to deal with the acute medical problems and so many people are so acutely unwell that the palliation and getting some systems controls and planning for the future does get a bit missed. (Ward 1, Medical 7, with 4 years’ experience)

Look in gen med it’s all about discharging people so unfortunately sometimes we overlook the needs of palliative patients and I don’t know how we can change that. (Ward 3, Allied health 7, with 6 years’ experience)

In addition to this alignment with organisational priorities, participants spoke about the skill needed to mentally switch between acute and emergent clinical responses, to the provision of palliative care.

Like your brain needs to switch between the very acute setting you know doing everything you could to save to someone’s life and then straight change to someone that we are withdrawing from treatment and just making them comfortable. So that’s two completely different brain sets sometimes it’s just difficult. (Ward 2, Nursing 3, with 12 years’ experience)

Adequate resourcing for optimal palliative care in the hospital setting

Adequate time, space and skill mix impacts the ability to support quality palliative care within the hospital setting, especially after hours when senior clinical support is more limited.

I think patient load would definitely be one of the issues because we’re just so busy all of the time and with palliative care a lot of that is the emotional support. I think the nurses just generally don’t have time to sit down and provide that emotional support for the patient and the families and also because we’re acute we have lots of new grads as well some of them not experienced in delivering this kind of care. (Ward 2, Nursing 3, with 12 years’ experience)

There’s not enough time for honestly after hours in particular any of the patient’s care needs. All you need is one sick person on a ward. One properly sick person having a MERT [medical emergency response] and no one gets good care. Yes of course that’s a factor. (Ward 3, Medical 2, with 31 years’ experience)

Medical leadership to establish a clear understanding of the illness and expectations for the future

Nursing and allied health clinicians noted the critical role for medical leadership to establish shared understanding of the illness and expectations for the future and support honest and clear discussions within the team and with patients and families.

… that should be like a consultant like a really clear plan not someone who doesn’t know this person walking in and going okay I don’t know what to do, am I doing blood cultures again? (Ward 2, Nursing 10, with 8 years’ experience)

Like if the patient has had a disease progression it’s really important I think for the team to communicate that to us as the allied health team so that we understand that this is potentially now a new base line so it might not necessarily be appropriate to advocate for that pathway so what can we offer. (Ward 1, Allied health 6, with 8 years’ experience)

However, clear communication of medical plans was often complicated by the varied skills and experience of staff in a teaching hospital, the complexity of staff rostering, and organisational silos created within and between departments.

… so I think having access to you know the decision maker, the senior clinician that is sort of comfortable making calls and supporting the junior staff throughout the day would then mean that there is better planning in the after-hours space and a little bit more consistency. (Ward 2, Nursing 10, with 8 years’ experience)

… and I think it’s just because it’s happening as an out-patient and maybe we just don’t see it but when we come to the ward like we just don’t really know what’s been happening as an out-patient and maybe the discussions have been had but it’s not just documented. (Medical 7, with 4 years’ experience)

Mechanisms to enable effective communication across the full multi-disciplinary team

Participants recognised the difficulties of communicating complex care needs and person-centred goals of care for inpatients with palliative care needs across specialties and disciplines. Challenges included early identification of goals of care, engagement of family carers and how to ensure the full multidisciplinary team is informed of ongoing changes. Daily multidisciplinary team meetings and technological solutions to support rapid family meeting planning were identified as useful.

I do find that there’s a lot of people duplicating and you think that somebody else has arranged something but they haven’t but then some other situation everybody’s organised it... How do we make sure that everybody’s on the same page and that’s quite time consuming... (Ward 1, Medical 1, with 19 years’ experience)

… we had MDTs [multidisciplinary team meetings] every single day with all of the allied health and all of the like key stakeholders and I felt that really helped to refocus everything and get all the necessary people in one place to make faster decision making. (Ward 1, Medical 5, with 2 years’ experience)

Theme 5—Optimising the clinical environment to enable private, restful and family-friendly spaces

Need for private space to support quality palliative care

Most participants described the challenges of providing terminal care within the constraints of limited private rooms.

I think it’s really that end of life where if we’ve used up all of our single rooms, which often happens because of other requirements from infection control and that sort of thing I think it’s like maybe three or something single rooms and they’re not terribly big. So at that sort of end-of-life stage if a patient is at the care of the dying pathway I find it quite awkward in those smaller rooms or even worse if a single room isn’t available. (Ward 1, Medical 2, with 6yrs experience)

Environmental factors also impact the ability to provide optimal communication. Specifically, participants described the need for space that provides the opportunity for privacy and prioritised time that is not interrupted.

... Like we’ve normalised being able to just interrupt whenever the hell we like and I think we’ve lost that respect to important conversations when nurses or doctors or allied health members are doing really important cognitive assessments or conveying bad news or asking what the patient’s wishes and values are. We don’t make a safe space for that as all and I would like to see improvement for that. (Ward 2, Nursing 2, with 19yrs experience)

Participants also explained that acute ward environments impacted on patients’ ability to rest, due to limited space, large numbers of clinical teams, and noise from confused patients and emergency clinical responses. Some participants who had experience of working in inpatient specialist palliative care units noted the noise level and restfulness of the ward to be palpably different to the general ward environment.

Those wards are gross, you know you’re in a four-bed bay, they’re mixed genders, they’re dirty, there’s a really high sort of movement across the ward in terms of patients but then also the number of staff up there is extreme. It’s not a place that constitutes rest for anyone. (Ward 1, Allied health 3, with 5yrs experience)

In other hospitals when you go to a ward that’s a palliative care unit it’s just a totally different feel you know like it’s calm, it’s welcoming, it's supportive. Whereas you come into a ward that’s an acute ward it’s chaos and it’s not the most ideal environment to have palliative care patients. (Ward 2, Nursing 4, with 20 yrs experience)

Family friendly wards

Participants described a lack of designated and welcoming areas for family members to meet, to discuss and to engage in legacy work. They also identified a need for greater permission-giving for families to bring in comforting or meaningful items from home.

So at a minimum we need a family room. Somewhere for people to go and discuss, somewhere for families to get together and they can sit and discuss things as well. Not just have staff in there with them but just somewhere for families to be … I don’t know if we were talking really extravagant I would love to see a double bed in one room just once just so I can have patients lie together with their family when they want to. You know having family altogether. (Ward 1, Nursing 11, with 26yrs experience)

… more permission giving from staff essentially around please bring in your creature comforts, please bring in your doona or your own pillow. Please bring in some music. Yes your family’s here, here’s the kitchen family you can make your loved one a cup of tea whenever you like, not have these codes on the kitchen for some reason because there’s hot water in there probably and big signs saying do not sit here … Family friendly. (Ward 1, Allied health 1, with 5yrs experience)

Theme 6—Harnessing organisational support and multidisciplinary clinical leadership

Participants recognised that addressing the barriers identified would require dedicated time and resources to create sustainable innovation and change in providing optimal inpatient palliative care. Some also recognized that implementing change required additional skills.

I think so just to be given hours to actually like where you’re not pulled on line, like it’s protected time I guess to get things done … But I think if you for like I guess proper innovation and things like that I think you need like uninterrupted protected time where you can do the work. (Ward 1, Nursing 1, with 14yrs experience)

If there was some sort of practical you could do on how to do a project. I don’t know if that’s out there already. I haven’t had the time… I think people have got good ideas but they don’t really know how to go about changing. (Ward 1, Nursing 2, with 17yrs experience)

Participants valued opportunities for clinical teams to collectively reflect on local data, including patient and family feedback and clinical outcomes, to identify why improvement should occur and canvas practical clinician-driven solutions, rather than solutions being imposed top down. This was essential to harnessing clinician and organisational support in order to create optimal inpatient palliative care innovation and change.

I think it’s like looking through I guess the data or the evidence that you can pull on whatever area that you’re investigating and I think that goes a long way in reflecting what really is happening as opposed to what you think is happening. So I would say that’s probably driven like doing audits has probably gone a long way in driving and then based off those results to do quality improvement. (Ward 1, Allied health 4, with 5yrs experience)

… in the end if this is what we need to do we need to drill in why it’s so important. Why it’s important for us as clinicians and why is it important for the patient and their family that we are changing this thing or what we’re doing or what we’re looking at the practice for. And if you have a clear reason as to why you shouldn’t be able to stand there and argue that because if it’s a good enough why then that’s the reason. (Ward 3, Nursing 6, with 7yrs experience)

Participants recognised the need for genuine multidisciplinary engagement, and also identified the complexities of doing this in a siloed system with varied authorities and communication systems and frequent changes in team members related to shift work and term rotations.

I guess it’s just having the whole team on board and not just limiting to a nurse champion but you need the involvement of everyone medical oncology, radiation oncology, all the disciplines it can’t just be one voice. I’m just trying to think because everyone can work so differently and separately on the ward and trying to ensure it just needs to be just the general speak of the team on the ward. (Ward 1, Allied Health 2, with 6yrs experience)

Don’t even bother talking to doctors below the level I wouldn’t consultants, they change every whatever it is 10 or 12 weeks or something. Obviously the only people who are going to probably drive, push doctor wise is the consultants so you can get their opinions but they’re not going to drive the change... (Ward 3, Medical 2, with 31yrs experience)

Many participants identified the importance of the nurse unit manager (NUM) in providing leadership in change at the ward level, as well as the value of champions and leadership across multiple healthcare disciplines.

I suppose in terms of communicating to all the nursing staff in particular the NUM would be a key player and then yeah that would probably be the main way of disseminating the information most broadly. (Ward 3, Allied health 4, with 12yrs experience)

But having champions like have champions from different disciplines I think are key. People who are motivated to make change and are enthusiastic and you know that always goes a lot and people I think that’s probably it just the champions is my only key. (Ward 2, Medical 7, with 10yrs experience)

I think some of the nurses there are some tends to be the newer nurses that are open to change and making things better but I think there are a lot of nurses set in their ways that wouldn’t be open to change … I don’t think it would be confronting I think honestly it would be more of a I can’t be bothered or I just don’t want to do it. Like I’m just going to keep doing what I’m doing. (Ward 2, Nursing 9, with 1.5yrs experience)

Discussion

This qualitative study offers valuable insights into the challenges of delivering optimal inpatient palliative care within the context of three wards in a large Australian teaching hospital, as perceived by clinicians. Outcomes generated underscore the importance of organisational support and multidisciplinary clinical leadership in enabling both skill development and models of care that prioritise the complex care requirements of patients living with advanced serious illnesses. This includes environments that enable privacy, rest and family inclusion. Figure 1 provides an overview of study outcomes and their relationship to the provision of integrated palliative care. This study firmly notes the complexity of successfully enabling integrated palliative care within an environment that is resourced, skilled, and designed for acute, episodic medical care. These findings closely resonate with recent outcomes from the global core indicator set for integrated palliative care within the hospital setting Delphi study [4].

Fig. 1.

Key challenges and opportunities impacting inpatient integrated palliative care

Integrating palliative care within the hospital context is complex, and there is little evidence about how to achieve this [4, 10]. A recent cross-sectional study of 120 patients screened to have advanced serious illness noted four themes that influenced their quality of care: 1) Feeling supported inclusive of quality person-centred care focused on what matters most for each patient and their family; 2) Feeling informed with regular, honest communication about immediate care and what to expect into the future; 3) Feeling heard and sharing in decision making; and 4) Navigating the clinical environment noting attention to light, temperature and noise impacted patient wellbeing [6]. That is, patients living with advanced serious illness noted with clarity their need for excellent clinical care in addition to feeling well-informed and provided with opportunities to participate in decision-making within an environment conducive to rest. [6–9, 11].

Yet, as this study highlighted, there is a mismatch between what patients need (integrated palliative care) [6–9, 11] and how clinicians operationalise inpatient palliative care (terminal care or referral to SPC). This mismatch creates tension that is felt by patients who describe their care as disjointed and devoid of open discussions about future expectations, [6] while clinicians describe the challenges of navigating the ‘grey zone’ of providing palliative care within the context of prognostic uncertainty [5, 19, 20, 44]. The critical question of when and how to deliver quality inpatient palliative care should be the focus of future innovations that incorporate elements known to impact inpatient palliative care positively. This study suggests that if we cannot support clinical teams in better understanding their palliative care role within a shared care model, then inpatients living with advanced serious illnesses will continue to struggle to be well-informed, supported, and heard. While this outcome aligns with the global literature, which identifies the challenges of providing integrated palliative care, there is a lack of guidance on how to address this care gap, [4, 10] beyond capacity-building [45–48]. This study highlights the need to reorient the focus of building clinicians'palliative care capabilities onto understanding when and how to enable integrated palliative care, how to advocate across multidisciplinary teams to facilitate this within entrenched medical governance systems, and how to prioritise palliative care alongside urgent acute care demands. This reform is important as continuing to focus on the skill development of individual clinicians alone is unlikely to enable the system-level changes required to provide integrated palliative care.

If the current system continues to privilege acute, episodic care and fails to appreciate the complexities of inpatients living with advanced serious illness, true change will remain elusive [4, 5, 10]. This is critically important given the majority of Australians dying from an expected death continue to do so within the hospital setting [49] and in addition to deaths in hospital we also know a large proportion of patients require one or several admissions to hospital in their last year of life [6, 7, 10, 50–52]. At present, optimal care for this population of patients cannot be assured. [6, 8–11, 18, 50, 52].

Several recent studies have sought to understand better how to facilitate integrated palliative care, with a focus on shared governance between specialties, screening for need, and identifying key triggers that support reassessment by clinical teams. [53–56]. These studies emphasize the importance of carefully considering local contexts to achieve a meaningful impact, with no universal implementation model identified [4, 53–56]. Nevertheless, a focus on articulating how each ward or unit understands how integrated palliative care works for their context and patient population may facilitate improved palliative care provision over time [56]. Importantly, continuing efforts to improve understanding and attitudes about what palliative care could be and how this care could be constructed is required globally [57].

The tension expressed within our qualitative study regarding the definition of palliative care warrants attention. Globally, terminology to describe caring for people with advanced serious illnesses is complex, ambiguous and poorly understood [27, 28]. Despite the WHO [13] providing a comprehensive definition of palliative care over two decades ago, this has yet to be operationalised at service delivery levels. In part, this has occurred because there is a mismatch between policies advocating population-level care for all individuals living with advanced serious illness (in line with the WHO definition) and actual care delivery [58]. Our study found clinicians operationalised palliative care as either terminal care or referral to SPC, and it is well known that referrals to SPC often only occur in the final days of life [26, 52]. Although systems and referral criteria for optimal engagement with SPC are essential, [59] the design of models of shared care must be responsive to governance structures (often siloed medical practices) and evolving clinical needs over time.

The physical environment of acute hospitals must balance competing clinical needs for regular observation, risk management and urgent clinical responses with therapeutic needs for privacy, engagement with family, and rest. Hospital environments which facilitate a sense of identity, belonging and safety can improve care experiences for patients with palliative care needs and their families [6–9, 11, 60, 61]. Although some argue the need to create spaces that express the unique philosophy of care for people with palliative care needs, [62] similar design considerations support high quality person-centred care in other major inpatient groups such as patients living with cognitive impairment and frailty [63] yet hospitals continue to struggle to optimise space for rest, privacy and engagement [64].

Enabling change in relation to integrated palliative care within the hospital context is complex and remains an aspirational goal [4]. Hospital contexts are complex, adaptive, continuously responding to changing needs, highly regulated and fiscally constrained [65–68]. Therefore, understanding how best to support clinical teams to respond to the increasing demographic of people living with advanced illness and palliative care needs is urgently needed. Our study provides new understanding of the challenges clinicians grapple with to enable what patients with palliative care needs and their families require for high quality care [6, 9, 11, 69]. This understanding was shared across three different ward contexts (Supplementary file 2). This contextual understanding can help in the design and implementation of new approaches to integrating palliative care.

Strengths and limitations

Several strengths are evident in this qualitative study, which is founded on a robust approach to recruitment, data collection, and analysis. The analysis method using the iPARIHS qualitative coding framework [42] ensured a focus on individual, system and organisational factors impacting care delivery. A multidisciplinary research team and robust processes for research team coding, review and consensus supported rigorous analysis with a strong focus on clinical application within the local context. The two key limitations of this study are that recruitment occurred within one site which may limit generalisability of findings and exploration of optimal care for diverse populations did not occur. Given the question route for interviews focused on ‘ideal palliative care’, the lack of discussion about cultural and spiritual care is in itself an important finding that requires further exploration.

Conclusions

Our findings of multi-level barriers help to explain why integrated palliative care within the acute hospital setting remains elusive. Harnessing organisational support and multidisciplinary clinical leadership is key to successful change. Improvements with a focus on developing clinician knowledge, skills, and confidence in palliative care need to be supported by attention both to the organisational siloes that constrain shared care for people living with advanced disease and to the culture that prioritises a curative approach and high efficiency. Understanding how to best support clinical uncertainty in the context of advanced illness is crucial for providing care that aligns with what matters most to this population of patients and their families. Optimising the environment to enable privacy, rest and family inclusion also contributes to quality palliative care.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the participation and time from the three participating wards within this study. Many of these interviews were held within periods impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and their continued participation is a testament to their commitment to high quality palliative care.

Data management and sharing

Raw data are contained within this manuscript in the form of participant quotes and within supplementary files. The corresponding author is available to contact for further information.

Abbreviations

- SPC

Specialist Palliative Care

- iPARIHS

Integrated Promoting Action on Research in Health Services

- WHO

World Health Organization

- NUM

Nurse Unit Manager

Authors’ contributions

C.V, G.K and A.M led the coding and analysis work. All authors reviewed the themes and contributed to consensus discussions as these were finalised. C.V and A.M wrote the main manuscript text with extensive reviewer input from G.K throughout. All authors reviewed the manuscript as it progressed to final format.

Data availability

Raw data are contained within this manuscript in the form of participant quotes and within supplementary files. The corresponding author is available to contact for further information.

Declarations

J.L Phillips is a Senior Editorial Board Member for BMC Palliative Care and C Virdun is an Editor for BMC Palliative Care.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was granted by Townsville Hospital and Health Service (THHS) Human Research Ethics Committee in May 2022 with reference number HREC/2022/QTHS/84709. The THHS Human Research Ethics Committee reviewed this ethics submission on request from the local ethics committee due to a local weather event (flooding) impacting workflow. The THHS Human Research Ethics Committee is certified by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) to review and approve multi-centre research under the national approach. Local governance approval from Metro North Hospital and Health Service (governing the participating hospital) was obtained prior to study commencement. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed written consent was obtained from each interview participant. Transcripts were deidentified for analysis.

Competing interests

J.L Phillips is a Senior Editorial Board Member for BMC Palliative Care and C Virdun is an Editor for BMC Palliative Care. Given J.L Phillips; position as Senior Editorial Board Member for BMC Palliative Care we are requesting a waiver of the APC please.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sleeman KE, De Brito M, Etkind S, Nkhoma K, Guo P, Higginson IJ, et al. The escalating global burden of serious health-related suffering: projections to 2060 by world regions, age groups, and health conditions. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(7):e883–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.May P, Roe L, McGarrigle CA, Kenny RA, Normand C. End-of-life experience for older adults in Ireland: results from the Irish longitudinal study on ageing (TILDA). BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NíChróinín D, Goldsbury DE, Beveridge A, Davidson PM, Girgis A, Ingham N, et al. Health-services utilisation amongst older persons during the last year of life: a population-based study. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nevin M, Payne S, Smith V. Identification of core indicators for the integration of a palliative care approach in hospitals: An international Delphi study. Palliative Medicine. 2024:02692163241283540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Nevin M, Hynes G, Smith V. Healthcare providers’ views and experiences of non-specialist palliative care in hospitals: a qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis. Palliat Med. 2020;34(5):605–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh GK, Mudge A, Matthews R, Yates P, Phillips JL, Virdun C. Experience of care from the perspectives of inpatients with palliative care needs: a cross-sectional study using a patient reported experience measure (PREM). BMC Palliat Care. 2024;23(1):177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Virdun C, Luckett T, Davidson P, Lorenz K, Phillips J. Hospital patients’ perspectives on what is essential to enable optimal palliative care: a qualitative study. Palliat Med. 2020;34(10):1402–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Virdun C, Luckett T, Davidson PM, Lorenz K, Phillips J. Generating key practice points that enable optimal palliative care in acute hospitals: Results from the OPAL project’s mid-point meta-inference. Int J Nurs Stud Adv. 2021;3:100035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Virdun C, Luckett T, Davidson PM, Phillips J. Dying in the hospital setting: a systematic review of quantitative studies identifying the elements of end-of-life care that patients and their families rank as being most important. Palliat Med. 2015;29(9):774–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Virdun C, Luckett T, Davidson PM, Phillips J. Strengthening palliative care in the hospital setting: a codesign study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2024;14(e1):e798–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Virdun C, Luckett T, Lorenz K, Davidson PM, Phillips J. Dying in the hospital setting: a meta-synthesis identifying the elements of end-of-life care that patients and their families describe as being important. Palliat Med. 2016;31(7):587–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark D, Centeno C, Clelland D, Garralda E, López-Fidalgo J, Downing J, et al. How are palliative care services developing worldwide to address the unmet need for care. U: Connor SR, ur Global Atlas of Palliative Care. 2020 2:10–6.

- 13.World Health Organization. WHO Definition of Palliative Care 2020 [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care.

- 14.Australian Government Department of Health. National Palliative Care Strategy 2018. Australia; 2018.

- 15.Australian Government Department of Health DaA. What is palliative care? 2025 [Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/topics/palliative-care/about-palliative-care/what-is-palliative-care#:~:text=aged%20care%20home.-,Who%20is%20palliative%20care%20for?,care%20for%20years%20if%20needed.

- 16.Palliative Care Australia and KPMG. Investing to save. The economics of increased investment in palliative care in Australia. Canberra, Australia: https://palliativecare.org.au/kpmg-palliativecare-economic-report; 2020.

- 17.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Classifying Place of Death in Australian Mortality Statistics Australia2021 [Available from: Accessed May 24. 2024 https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/research/classifying-place-death-australian-mortality-statistics#results.

- 18.Virdun C. Optimising care for People with palliative care needs, and their families, in the Australian hospitaL setting: the OPAL Project: University of Technology Sydney; 2021.

- 19.Ellis-Smith C, Tunnard I, Dawkins M, Gao W, Higginson IJ, Evans CJ. Managing clinical uncertainty in older people towards the end of life: a systematic review of person-centred tools. BMC Palliat Care. 2021;20:1–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bloomer M. Palliative care provision in acute and critical care settings: what are the challenges? Palliat Med. 2019;33(10):1239–40. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higginson I, Rumble C, Shipman C, Koffman J, Sleeman K, Morgan M, et al. The value of uncertainty in critical illness? An ethnographic study of patterns and conflicts in care and decision-making trajectories. BMC Anesthesiol. 2015;16:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cardona-Morrell M, Kim J, Turner RM, Anstey M, Mitchell IA, Hillman K. Non-beneficial treatments in hospital at the end of life: a systematic review on extent of the problem. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(4):456–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hillman K, Barnett AG, Brown C, Callaway L, Cardona M, Carter H, et al. The conveyor belt for older people nearing the end of life. Intern Med J. 2024;54(8):1414–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan CW, Chow MC, Chan S, Sanson-Fisher R, Waller A, Lai TT, et al. Nurses’ perceptions of and barriers to the optimal end-of-life care in hospitals: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(7–8):1209–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Connolly M, Ryder M, Frazer K, Furlong E, Escribano TP, Larkin P, et al. Evaluating the specialist palliative care clinical nurse specialist role in an acute hospital setting: a mixed methods sequential explanatory study. BMC Palliat Care. 2021;20:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boddaert MS, Stoppelenburg A, Hasselaar J, van der Linden YM, Vissers KC, Raijmakers NJ, et al. Specialist palliative care teams and characteristics related to referral rate: a national cross-sectional survey among hospitals in the Netherlands. BMC Palliat Care. 2021;20:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hui D, De La Cruz M, Mori M, Parsons HA, Kwon JH, Torres-Vigil I, et al. Concepts and definitions for “supportive care”,“best supportive care”,“palliative care”, and “hospice care” in the published literature, dictionaries, and textbooks. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:659–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hui D, Nooruddin Z, Didwaniya N, Dev R, De La Cruz M, Kim SH, et al. Concepts and definitions for “actively dying”,“end of life”,“terminally ill”,“terminal care”, and “transition of care”: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47(1):77–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eagar K, Green J, Gordon R. An Australian casemix classification for palliative care: technical development and results. Palliat Med. 2004;18(3):217–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Australian Health Services Research Institute (AHSRI). Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration Wollongong2020 [Available from: http://www.pcoc.org.au/.

- 31.Forbat L, Johnston N, Mitchell I. Defining ‘specialist palliative care’: findings from a Delphi study of clinicians. Aust Health Rev. 2019;44(2):313–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The University of Edinburgh. SPICT [Available from: https://www.spict.org.uk/.

- 33.Harvey G, Kitson A. PARIHS revisited: from heuristic to integrated framework for the successful implementation of knowledge into practice. Implement Sci. 2015;11(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunter D, McCallum J, Howes D. Defining exploratory-descriptive qualitative (EDQ) research and considering its application to healthcare. Journal of Nursing and Health Care. 2019;4(1).

- 35.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saunders CH, Sierpe A, von Plessen C, Kennedy AM, Leviton LC, Bernstein SL, et al. Practical thematic analysis: a guide for multidisciplinary health services research teams engaging in qualitative analysis. BMJ. 2023;381:e074256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Creswell, J and Creswell J,. Research Design. Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Method approaches (5th Ed). California, United States: SAGE publications, Inc; 2018.

- 38.Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ. Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educ Res. 2004;33(7):14–26. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andrew S, Halcomb EJ, editors. Mixed Methods Research for Nursing and the Health Sciences. West Sussex, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2009.

- 40.Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. The Lancet. 2001;358(9280):483–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ritchie MJ, Drummond KL, Smith BN, Sullivan JL, Landes SJ. Development of a qualitative data analysis codebook informed by the i-PARIHS framework. Implementation science communications. 2022;3(1):98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Etkind SN, Barclay S, Spathis A, Hopkins SA, Bowers B, Koffman J. Uncertainty in serious illness: A national interdisciplinary consensus exercise to identify clinical research priorities. PLoS ONE. 2024;19(2):e0289522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yates P. Developing the primary palliative care workforce in Australia. Cancer Forum. 2007;31(1).

- 46.Yates P, Nash R, Hegarty M, Currow D, Devery K, Mitchell G, et al. The Palliative Care Curriculum PCC4U Project: A progress report on uptake. 2008.

- 47.Gillan PC, Johnston S. Nursing students satisfaction and self-confidence with standardized patient palliative care simulation focusing on difficult conversations. Palliat Support Care. 2024;22(5):1237–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Orr F, Kelly M, Virdun C, Power T, Phillips A, Gray J. The development and evaluation of an integrated virtual patient case study and related online resources for person-centred nursing practice. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;51:102981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Admitted patient care 2017–18: Australian hospital statistics. Health services series no. 90. Cat. no. HSE 225. Canberra: AIHW.; 2019.

- 50.To T, Hakendorf P, Currow DC. Screening for End-of-Life in Acute Hospitals: A Cross-Sectional Survey. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®. 2024:10499091231226299. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Mudge AM, Douglas C, Sansome X, Tresillian M, Murray S, Finnigan S, et al. Risk of 12-month mortality among hospital inpatients using the surprise question and SPICT criteria: a prospective study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2018;8(2):213–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mitchell I, Lacey J, Anstey M, Corbett C, Douglas C, Drummond C, et al. Understanding end-of-life care in Australian hospitals. Aust Health Rev. 2021;45(5):540–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Castro JA, Hannon B, Zimmermann C. Integrating palliative care into oncology care worldwide: the right care in the right place at the right time. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2023;24(4):353–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim JM, Godfrey S, O’Neill D, Sinha SS, Kochar A, Kapur NK, et al. Integrating palliative care into the modern cardiac intensive care unit: a review. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2022;11(5):442–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.El-Jawahri A, LeBlanc TW, Kavanaugh A, Webb JA, Jackson VA, Campbell TC, et al. Effectiveness of integrated palliative and oncology care for patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(2):238–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]