Abstract

Yield in cereals is a function of seed number and weight; both parameters are largely controlled by seed sink strength. The allosteric enzyme ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (AGP) plays a key role in regulating starch biosynthesis in cereal seeds and is likely the most important determinant of seed sink strength. Plant AGPs are heterotetrameric, consisting of two large and two small subunits. We transformed wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) with a modified form of the maize (Zea mays L.) Shrunken2 gene (Sh2r6hs), which encodes an altered AGP large subunit. The altered large subunit gives rise to a maize AGP heterotetramer with decreased sensitivity to its negative allosteric effector, orthophosphate, and more stable interactions between large and small subunits. The Sh2r6hs transgene was still functional after five generations in wheat. Developing seeds from Sh2r6hs transgenic wheat exhibited increased AGP activity in the presence of a range of orthophosphate concentrations in vitro. Transgenic Sh2r6hs wheat lines produced on average 38% more seed weight per plant. Total plant biomass was increased by 31% in Sh2r6hs plants. Results indicate increased availability and utilization of resources in response to enhanced seed sink strength, increasing seed yield, and total plant biomass.

Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is one of the world's most important crop plants. An estimated 610 million metric tons of wheat seed were harvested worldwide in the 1997/98 growing season (1). Wheat seed yield is determined by seed number and weight. Starch is the major component of wheat yield, comprising 70% of wheat seed dry weight. ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (AGP; EC 2.7.7.27), an allosterically regulated heterotetramer consisting of two large and two small subunits, catalyzes the rate-limiting reaction in starch biosynthesis in plants (reviewed in refs. 2 and 3). AGP uses the substrates glucose 1-phosphate and ATP to produce ADP-glucose and pyrophosphate (4). ADP-glucose is then used as the glucose donor for starch synthases. The positive allosteric effector of AGP is 3-phosphoglycerate, whereas the negative allosteric effector is orthophosphate (Pi) (2, 3). Maize endosperm AGP (5) large subunits are encoded by Shrunken2 (Sh2) (6), whereas small subunits are encoded by Brittle2 (Bt2) (7).

Inhibition of AGP activity by Pi appears to limit starch biosynthesis and yield in crop plants. Evidence for this has come from studies of a modified AGP large subunit in maize (8) and from use of an altered bacterial AGP in potato (9). In both cases, AGP modification caused reduced sensitivity to Pi inhibition, resulting in enhanced yield, manifested as increased seed weight in maize (8) and increased starch content in potato (9). Instability of AGP may be an additional limitation on cereal yield. AGP is perhaps the most heat-labile starch biosynthetic enzyme in maize (10–12). A single amino acid substitution in the maize large subunit that conditions more stable large subunit–small subunit interactions (13) may lead to enhanced AGP activity and increased yield. Thus, either decreased sensitivity to allosteric inhibition or increased AGP heterotetramer stability could enhance AGP activity, resulting in increased yield.

Starch biosynthetic enzyme activity within a sink organ is a major determinant of sink strength (14). In wheat, a minority of flowers develop into mature seeds (15, 16). Because AGP is the rate-limiting step in starch biosynthesis, an increase in AGP activity within the endosperm of wheat seeds should increase developing seed sink strength and overall plant productivity.

Here we test the hypothesis that increased AGP activity within developing wheat seed endosperm increases yield. Wheat was transformed with a modified maize Sh2 gene (Sh2r6hs), which encoded an altered AGP large subunit, giving rise to an AGP heterotetramer with decreased sensitivity to inhibition by Pi and more stable large subunit–small subunit interactions. Wheat expressing the transgene produced more seed weight and total plant biomass. Possible explanations for this increased availability and utilization of resources are discussed.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid Constructs Used for Transformation.

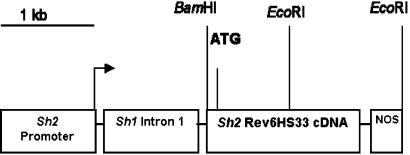

Construct pRQ101A was used for selection of transformed wheat lines. It contains the bar gene (17) controlled by the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter (CaMV 35S) and the nopaline synthase (NOS) terminator. The bar gene confers resistance to the herbicides bialaphos (Meiji Seika Kaisha, Tokyo) and glufosinate (AgrEvo, Wilmington, DE). Construct pSh2r6hs contains a 1,557-bp modified maize Sh2 cDNA coding sequence (Sh2r6hs) (Fig. 1) with two alterations relative to the wild-type Sh2 sequence (18). The rev6 mutation is a 6-bp insertion resulting in the addition of tyrosine and serine at amino acid positions 495 and 496 of the AGP large subunit. This insertion renders AGP less sensitive to Pi inhibition (8). The second change, hs33, is a point mutation causing substitution at amino acid position 333 of tyrosine for histidine and confers more stable large subunit–small subunit interactions in the AGP heterotetramer (13). This modified Sh2 coding sequence, Sh2r6hs, was combined in pUC19 with the maize endosperm Sh2 promoter and 5′ untranslated-sequences (18), the Sh1 intron 1 cassette (19), and NOS 3′ terminator.

Figure 1.

Structure of the expression construct pSh2r6hs. The Sh2 promoter, modified Sh2 coding region, Sh1 intron 1 cassette, and nopaline synthase polyadenylation region are shown as open boxes drawn approximately to scale. Lines represent short pieces of polylinker DNA that connect the gene elements and are not to scale. The plasmid vector pUC19 is not shown. The transcription start site is designated by the arrow, and the translation initiation site is shown as ATG. Relevant restriction endonuclease sites are indicated.

Wheat Transformation.

The approach used for production of fertile transgenic wheat plants was adapted from that described by Weeks et al. (20) and Altpeter et al. (21). Immature embryos 0.5–1.5 mm long were isolated from greenhouse-grown wheat variety Hi-Line (22) and placed on S1 callus induction medium [4.32 g MS Basal Medium (Sigma)/150 mg l-asparagine/40 mg of thiamine/20 g of maltose/2 mg of 2,4-dichlorophenoxy-acetic acid/2.5 g of phytagel per liter, pH 5.7–5.8)] for 5–8 days in the dark at 25°C. Calli were then moved to S1 medium supplemented with 0.4 M sorbitol 4 h before bombardment. Constructs pSh2r6hs and pRQ101A were precipitated on 1-μm-diameter gold particles in a 1:1 molar ratio by using a standard protocol (23). Calli were bombarded twice by using 1,550-psi rupture disks and 6-cm target distance in a Biolistic PDS-1000/He Particle Delivery System (Bio-Rad). After ≈17 h, calli were moved to a selection medium consisting of S1 medium supplemented with an additional 20 g/liter of maltose and 5 mg/liter of bialaphos, maintained for 3 weeks in the dark at 25°C, and then placed on regeneration medium. Regeneration medium was same as selection medium but without 2,4-D and containing 1 mg/liter of kinetin and 0.5 mg/liter of indoleacetic acid. Once shoots reached ≈0.5 cm in height, plantlets were moved to rooting medium (2.16 g of MS Basal Medium/75 mg of l-asparagine/20 mg of thiamine/10 g of maltose/2.5 g of phytagel/5 mg of bialaphos/0.01 mg/liter of 1-naphthalene-acetic acid per liter, pH 5.7–5.8) in the light at 25°C. Regenerated plantlets were transferred to soil, allowed to grow for 1–3 weeks, and sprayed with 0.1% glufosinate to identify transgenics.

PCR Screening of Transgenic Lines.

PCR using genomic DNA from T0 plants was done to identify transgenic lines containing the Sh2r6hs sequence. Genomic DNA was isolated (24) and resuspended in TE medium (10 mM Tris/1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0). PCR reactions were performed by using an upstream PCR primer, 5′-CTGGATGTGAACTCAAGGACTCCGTG-3′, that hybridizes beginning 293 bases upstream of the stop codon of the Sh2r6hs cDNA and a downstream primer, 5′-GGCTTAACTATGCGGCATCAGAGC-3′, complementary to the pUC sequence beginning 257 bases downstream of the nopaline synthase terminator. This primer pair produces an amplified product of 826 bp. Cycling parameters consisted of 94°C for 3 min, 40 cycles of 94°C 45 s, 48°C 30 s, and 72°C 90 s, followed by 72°C for 5 min.

Southern, Northern, and Western Blot Analyses.

For Southern blot analysis, 20 μg of genomic DNA isolated (24) from homozygous T2 plants was digested with EcoRI (Promega), fractionated on 0.7% agarose gels, and transferred to a nylon membrane (Osmonics, Minnetonka, MN). The membrane was probed with the 32P-labeled Sh2r6hs coding sequence labeled by the random primer method (New England BioLabs). Hybridized membranes were washed twice in 2× sodium chloride/sodium phosphate/EDTA (SSPE) (3.6 M NaCl/0.2 M NaH2PO4/0.02 M EDTA, pH 7.3) and twice in 0.2× SSPE at 65°C (15 min/wash) and exposed to x-ray film with an intensifying screen at −80°C.

RNA for Northern blot analysis was extracted from 20 days postanthesis (dpa) homozygous T3 seeds ground in liquid nitrogen, by using a LiCl method (25). Ten micrograms of total RNA per lane was separated on a denaturing formaldehyde agarose gel and blotted onto a nylon membrane. Membranes were probed with the 32P-labeled Sh2r6hs coding sequence (see above) or a 1.7-kb maize Bt2 cDNA sequence (7). Probes were prepared and membranes were washed and detected as described above.

Total buffer soluble protein was extracted from 20-dpa homozygous T3 seeds by grinding kernels in SDS sample buffer (90 mM Tris, pH 6.8/19% vol/vol glycerol/2% SDS/5% β-mercaptoethanol/0.1% bromophenol blue/0.1% xylene cyanol) using 150 μl of buffer/20 mg of fresh seed weight followed by heating at 70°C for 15 min. Aliquots of protein samples were fractionated in 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose (Osmonics). Lanes were loaded with 8 μl for gels probed with SH2 antibody and 8 μl of a 1/10 dilution of protein samples made in SDS sample buffer for gels probed with the BT2 antibody. Antibody probing was done by using rabbit polyclonal anti-SH2 or anti-BT2 primary antibodies (26) at concentrations of 1/3,000 and goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Fisher) at a concentration of 1/10,000. Detection was accomplished by using an Enhanced Chemiluminescence kit according to instructions from the manufacturer (Amersham Pharmacia Pharmacia Biotech).

AGP Activity Assays.

AGP activity assays were performed essentially as described previously (8) by using seeds harvested 20 dpa ground in liquid nitrogen. Means with standard errors were calculated from three replicates for each combination of reaction conditions. AGP activity data reported for each sample were proportional to time of assay and dilution of the crude enzyme preparation.

Plant Yield Data Collection and Analysis.

All yield data were obtained by using weights of seeds, leaves, and stems that had been counted and weighed after drying to an equivalent moisture content. Means for positive and negative group plants were compared by using the two-sample t test with unequal variances and α = 0.05. T0 transgenic wheat plants were grown to maturity in the greenhouse. Twenty-four T1 seeds from each T0 plant were planted. At the two-leaf stage, seedlings were sprayed with 0.1% glufosinate to identify resistant plants. Resistant seedlings were grown to maturity. Progeny tests were conducted on T1 plants by planting T2 seeds derived from a single T1 plant. Two-leaf T2 seedlings were tested with 0.1% glufosinate and T1 plants giving rise only to resistant T2 seedlings (>11) were considered homozygous.

On the basis of PCR results, phenotypic data from T0 and T1 plants, and preliminary Western blot analyses, eight PCR positive T1 lines (152–2, 152–7, 152–9, 152–10, 155–4, 161–5, 161–8, and 161–12) were chosen for production of T2 plants and T3 seeds. One PCR negative line (161) was randomly chosen for this purpose. Two homozygous T2 seedlings were transplanted per 8-inch pot, and 20–40 homozygous T2 plants per transgenic line were analyzed. The pots were arranged randomly in the greenhouse. For expression analysis, seeds from a separate group of plants were harvested at 20 dpa at ≈1:00 p.m. and frozen at −80°C.

Phenotypic data for T2 wheat plants containing the maize AGP large subunit were compared with data from lines lacking the introduced subunit. Data means were calculated for the two plants in a pot, and each pot was treated as an experimental unit.

A T3 generation plant homozygous for Sh2r6hs from transgenic line 161–12 was crossed with the untransformed variety (Hi-Line). Fifty randomly selected F2 generation progeny were grown to maturity in the greenhouse. Plants were progeny tested by Southern blotting, probing for Sh2r6hs as described above, and classified as Sh2r6hs homozygous positive, heterozygous, or homozygous negative.

Greenhouse Conditions.

All plants were grown in a greenhouse in the Montana State University Bozeman Plant Growth Center. Greenhouse conditions consisted of target temperatures of 22°C and 14°C for day and night, respectively, and with supplemental lighting providing 400 μE m−2⋅s−1 consisting of 1,000-W metal halide lamps on from 5:00 a.m. until 1:30 p.m. and from 4:00 p.m. until 9:00 p.m. Plants were watered as needed with 7.5 g of Peters 20–20-20 General Purpose NPK plant food per liter of water (The Scotts Company, Marysville, OH).

Results

Production of Transgenic Lines.

A total of 1,298 calli derived from immature wheat embryos were cotransformed with pSh2r6hs (Fig. 1) and pRQ101A in five separate experiments. Twenty-eight fertile wheat lines resistant to 0.1% glufosinate (indicating presence and functioning of the introduced bar gene) were generated. PCR analysis of leaf genomic DNA revealed that 17 lines (61%) also contained the Sh2r6hs sequence (data not shown). The 17 PCR-positive T0 lines averaged 33% more seeds per plant at maturity than did the 11 PCR-negative lines (182 vs.136). In addition, heads containing 40 or more seeds occurred at twice the frequency within the PCR-positive group than in the PCR-negative group (28 vs. 14%).

Transgene Segregation.

χ2 analysis of glufosinate-resistant versus -sensitive progeny of T0 plants was performed, testing fit to a 3:1 ratio. For seven of the nine transgenic lines studied, segregation ratios were consistent with transgene integration at only one locus (Table 1). Segregation ratios of progeny of the 161–1 and 161–5 T0 plants were less than 3/1, which is inconsistent with integration at more than one locus. These ratios likely reflect the misclassification of transgenic seedlings as nontransgenic.

Table 1.

Presence and expression of the modified maize AGP large subunit transgene in nine transgenic wheat lines

| Line* | PCR | Northern | Western | Resistant/sensitive progeny of T0 plants | χ2† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 161-1 | − | − | − | 9/8 | 4.4 |

| 152-2 | + | − | − | 17/3 | 1.07‡ |

| 152-9 | + | − | − | 7/5 | 1.77‡ |

| 161-5 | + | − | − | 10/10 | 6.67 |

| 152-10 | + | + | − | 16/5 | 0.016‡ |

| 152-7 | + | + | + | 21/3 | 2.0‡ |

| 155-4 | + | + | + | 17/2 | 2.12‡ |

| 161-8 | + | + | + | 17/4 | 0.31‡ |

| 161-12 | + | + | + | 7/4§ | 0.76‡¶ |

Line number is comprised of bombardment number followed by transgenic plant number from that bombardment.

χ2 values test fit of counts of resistant/sensitive progeny of T0 plants to 3:1 ratio.

χ2 values consistent with integration at a single locus.

Counts of resistant heterozygous/resistant homozygous T1 plants determined by progeny testing T2 seeds obtained from resistant single T1 plants. Counts of resistant/sensitive progeny of T0 plants were not obtained for 161-12.

χ2 values test fit of resistant heterozygous/homozygous T1 plant counts to 2:1 ratio.

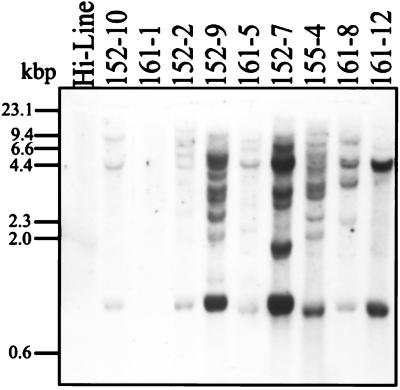

Southern, Northern, and Western Blot Analyses.

EcoRI-digested leaf genomic DNA from homozygous T2 plants of nine transgenic lines, and an untransformed Hi-Line control was used for Southern blot analysis (Fig. 2). The blot was probed with the 32P-labeled Sh2r6hs cDNA. As expected, there was no significant hybridizing signal from the untransformed control or from line 161–1. The eight PCR-positive lines each showed unique banding patterns, indicating independent transformation events. The complex banding patterns and variable signal strength suggested the presence of multiple copies of Sh2r6hs.

Figure 2.

Southern blot analysis of nine transgenic wheat lines and an untransformed Hi-Line control. Twenty micrograms of EcoRI-digested total wheat leaf DNA was fractionated on a 0.7% agarose gel, blotted to a nylon membrane, and probed with 32P-labeled Sh2r6hs.

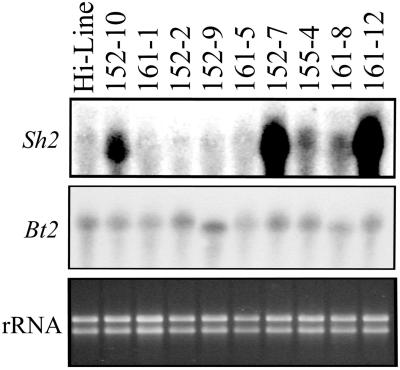

RNA analysis was performed by using total RNA extracted from 20-dpa homozygous T3 seeds (Fig. 3). No Sh2r6hs hybridizing transcripts were detected from the untransformed Hi-Line control or from line 161–1. Among the eight PCR-positive lines, five contained a detectable Sh2r6hs transcript with 152–7 and 161–12 exhibiting strongest expression. Probing of a duplicate membrane with Bt2, which hybridizes to the native wheat AGP small subunit mRNA, indicated that samples were loaded relatively equally and at a similar developmental stage.

Figure 3.

Analysis of RNA from nine transgenic wheat lines and an untransformed Hi-Line control. Ten micrograms of total RNA from 20-dpa seeds was fractionated on a formaldehyde agarose gel, blotted to nylon, and probed with 32P-labeled Sh2r6hs or Bt2. Comparable ethidium bromide staining and discrete bands of rRNA fractionated in an agarose gel indicate similar loading from lane to lane and lack of RNA degradation.

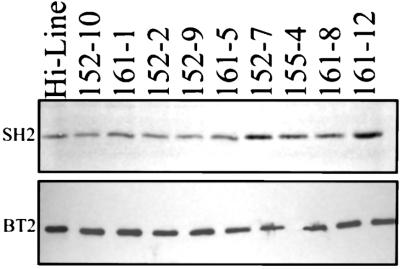

Presence of SH2R6HS was analyzed by Western blotting (Fig. 4). The SH2 antibodies recognize both the SH2R6HS and the native wheat AGP large subunit. Signal from the Hi-Line control, 161–1, and the three PCR-positive lines lacking Sh2r6hs mRNA expression (152–2, 152–9, and 161–5) is attributable to SH2 antibody binding to the native wheat AGP large subunit only. Four of the five Sh2r6hs mRNA-positive lines showed increased signal attributable to the presence of SH2R6HS. Among these four lines, 152–7 and 161–12 exhibited the strongest signal. In line 152–10, Sh2r6hs hybridizing transcripts were detected with no increase in SH2 antibody recognized protein. Similar signal strengths from line to line when probed with anti-BT2 antibodies indicated similar loading of protein samples. PCR, Northern blot, and Western blot results for the nine transgenic lines analyzed are summarized in Table 1. Of eight PCR-positive lines chosen for in-depth study, five express Sh2r6hs mRNA and, in four of these five, the transgene protein product is detectable.

Figure 4.

Immunoblot analysis of nine transgenic wheat lines and an untransformed Hi-Line control. Total proteins from 20-dpa seeds were fractionated by PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with SH2 or BT2 polyclonal antibodies. SH2 antibody binds to both the native wheat and introduced altered maize AGP large subunits. Enhanced signal in 155–4, 161–8, 152–7, and 161–12 was seen in each of three independent samples of developing seeds. Enhanced signals were quantified densitometrically and were roughly 1.5× that of the SH2 level from control Hi-Line for lines 161–8 and 155–4 and 2× that of Hi-Line for 152–7 and 161–12. BT2 antibody binds to the native wheat AGP small subunit.

AGP Activity Assays.

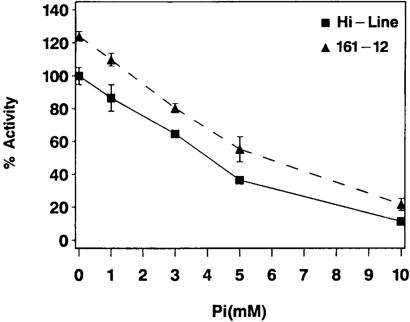

Endosperm AGP activity of SH2R6HS-positive line 161–12 was compared with that of untransformed Hi-Line by using in vitro assays (Fig. 5). Samples of 20-dpa T3 seeds were used for AGP extraction. Reactions contained 10 mM 3-phosphoglycerate and 0, 1, 3, 5, or 10 mM Pi. AGP activity is expressed as a percentage of the activity of Hi-Line at 0 Pi. AGP activity of 161–12 was greater than that of Hi-Line at each of the five Pi concentrations. The increase in AGP activity seen in 161–12 was observed in each of the other three SH2R6HS-positive lines, and no increases in AGP activity versus Hi-Line were seen in any other of the transgenic lines. The two stronger SH2R6HS expressers (152–7 and 161–12) did not appear to have greater AGP activity than the other two SH2R6HS-positive lines (155–4 and 161–8). The increase in AGP activity of 161–12 versus Hi-Line was larger with increasing Pi concentrations. In the absence of Pi, line 161–12 had 24% greater AGP activity than Hi-Line, whereas at 10 mm Pi, 161–12 had 91% more activity. With increasing concentrations of Pi, AGP activity decreased for both genotypes, dropping to 17 and 11% of maximum activity at 10 mM Pi for 161–12 and Hi-Line, respectively. Results of AGP activity assays indicated that SH2R6HS enhanced total AGP activity, and that its contributions to AGP activity are more significant as Pi concentrations increase.

Figure 5.

AGP activity from 20-dpa seeds of transgenic 161–12 and untransformed Hi-Line control. Data points (triangles connected by dashed lines for 161–12; squares connected by solid lines for Hi-Line) are the means, with standard errors, of three replicates for each combination of reaction conditions (10 mM 3-phosphoglycerate and 0, 1, 3, 5, or 10 mM Pi). AGP activity is expressed as a percentage of the activity exhibited by Hi-Line in the absence of Pi.

Plant Yield Analysis of Transgenic Lines.

The combination of Northern, Western, and AGP activity analyses indicated that four lines (152–7, 155–4, 161–8, and 161–12) expressed SH2R6HS. These four comprised the positive group. Three PCR-positive lines lacking detectable SH2R6HS expression (152–2, 152–9, and 152–10) along with the PCR-negative line, 161–1, made up the negative group. The PCR-positive SH2R6HS expression-negative line 161–5 was not included in phenotypic analysis because it proved to be a poorly performing line. Phenotypic comparisons were accomplished by comparing pooled data for the four positive group lines with pooled data for the four negative group lines.

Evaluation of phenotypic data for seeds from T0 plants of the eight lines showed 43% more seeds, 25% greater total seed weight, and 52% greater total plant biomass per plant (Table 2). However, the small sample sizes prevented statistical analyses. Phenotypic comparisons from heterozygous and homozygous T1 generation plants revealed the same yield enhancement trends and a SH2R6HS linear dosage response between heterozygous and homozygous plants (data not shown).

Table 2.

Plant and seed components of transgenic wheat plants expressing or not expressing the altered maize AGP large subunit (SH2R6HS)

| Generation† | Group‡ | Heads per plant

|

Seeds per plant

|

Seed weight per plant, g

|

Average individual seed weight, mg

|

Harvest index

|

Total plant biomass

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | |||

| T0 | Mean§ | 6.0 | 5.3 | 198.5 | 138.5 | 5.85 | 4.67 | 28.7 | 32.2 | 0.457 | 0.577 | 11.7 | 7.7 | |

| (2.6) | (2.5) | (109.1) | (74.0) | (3.22) | (2.56) | (2.2) | (3.3) | (0.092) | (0.022) | (6.5) | (4.4) | |||

| +/−¶ | 1.13 | 1.43 | 1.25 | 0.89 | 0.79 | 1.52 | ||||||||

| T2 | 152-7 | 7.5 | 44.1 | 1.34 | 29.8 | 0.180 | 6.4 | |||||||

| 155-4 | 5.2 | 56.6 | 1.70 | 29.8 | 0.255 | 5.7 | ||||||||

| 161-8 | 6.0 | 38.8 | 1.30 | 33.2 | 0.222 | 5.1 | ||||||||

| 161-12 | 5.9 | 71.7 | 2.50 | 34.8 | 0.310 | 7.2 | ||||||||

| 152-10 | 4.0 | 27.1 | 0.76 | 27.7 | 0.160 | 3.8 | ||||||||

| 161-1 | 5.8 | 52.6 | 1.80 | 34.1 | 0.256 | 6.2 | ||||||||

| 152-2 | 5.7 | 30.3 | 1.06 | 33.7 | 0.159 | 5.0 | ||||||||

| 152-9 | 5.1 | 39.8 | 1.32 | 32.2 | 0.255 | 4.4 | ||||||||

| Mean§ | 6.1 | 5.3 | 55.6 | 39.1 | 1.78 | 1.30 | 31.6 | 32.3 | 0.246 | 0.210 | 6.2 | 5.1 | ||

| (1.7) | (1.9) | (26.5) | (28.7) | (0.91) | (1.03) | (3.0) | (3.8) | (0.079) | (0.107) | (1.7) | (2.1) | |||

| +/−¶ | 1.15** | 1.42** | 1.37** | 0.98 | 1.17* | 1.22** | ||||||||

| F2‖ | Mean§ | 6.5 | 4.7 | 186.5 | 137.2 | 6.48 | 4.70 | 35.4 | 33.8 | 0.594 | 0.553 | 10.3 | 7.9 | |

| (1.7) | (1.1) | (42.2) | (42.2) | (1.33) | (1.65) | (6.4) | (4.9) | (0.031) | (0.091) | (1.8) | (1.8) | |||

| +/−¶ | 1.38** | 1.36** | 1.38** | 1.05 | 1.07 | 1.31** | ||||||||

For the T0 generation, n = 4 for both the positive and the negative group. For the T2 generation, n = 60 and 57 for the positive and negative groups, respectively. The 60 positives consist of 17 152-7, 20 155-4, 6 161-8, and 17 161-12. The 57 negatives consist of 12 152-10, 20 161-1, 15 152-2, and 10 152-9. Individual transgenic lines are from the T2 generation. For the F2 generation, n = 14 and 9 for plants homozygous positive and negative for SH2R6HS, respectively.

Numbers in + columns for T0 and T2 generations are pooled data for lines expressing SH2R6HS (152-7, 155-4, 161-8, and 161-12). Numbers in − columns for T0 and T2 generations are pooled data for lines lacking expression (152-2, 152-9, 152-10, and 161-1). Numbers in + and − columns for individual transgenic lines from the T2 generation are for lines expressing or lacking expression of SH2R6HS, respectively.

Group means are accompanied by standard deviations in parentheses.

For the F2 generation, numbers in + and − columns are progeny from a 161-12 × HL cross that are homozygous positive and negative for SH2R6HS, respectively.

+/− ratios are determined by dividing the positive group mean by the negative group mean.

,

, and

denote P < 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001, respectively.

The experimental design for phenotypic comparisons of T2 generation plants did permit statistical comparisons (Table 2). Homozygous T2-positive group plants produced 42% more seeds and 37% more total seed weight per plant. Harvest index, the ratio of total seed dry weight to total above-ground plant dry weight, was 17% greater, and total plant biomass was 22% greater. Analysis of individual transgenic lines from the T2 generation revealed that most or all of the lines negative for SH2R6HS showed values less than the mean for the positive lines as a group for the measured yield parameters (Table 2). Conversely, most or all of the positive lines yielded greater than the mean for the negative lines. Positive line 161–12 ranked best among the positive lines in both seed yield per plant and total plant biomass (Table 2) and likely had the highest expression of Sh2r6hs (Figs. 3 and 4).

Because of potential tissue culture effects, it is difficult to determine the influence of the Sh2r6hs transgene on yield without crossing a transgenic line back to the untransformed parent variety. Transgenic line 161–12 was chosen for that purpose. In a comparison of plant productivity of F2 progeny from the transgenic line 161–12 × untransformed Hi-Line cross, plants homozygous positive for Sh2r6hs produced ≈38% more seed weight and 31% more total plant biomass. Increases in plant biomass were also seen as increases in number of fertile heads per plant in all generations examined. Although seeds occurring on later heads accounted for roughly half of the yield increase, the remaining yield increase (or roughly 19% for the F2 161–12 genotypes) came from increased seed set on heads occurring in both control and transgenic plants.

Taken together, the phenotypic data indicate that expression of Sh2r6hs in wheat increased seed yield without reducing individual seed weight. The increase in total plant biomass observed in plants expressing Sh2r6hs in all three generations analyzed indicates increased overall plant growth and productivity.

Discussion

Increases in AGP activity in sink tissues of agronomically important plants have been shown to enhance seed size in maize (8) and starch content in potato (9). The unfulfilled yield potential in wheat whereby a significant percentage of potential seeds do not develop (27, 28) offers an opportunity to increase plant productivity and seed yield. Here we tested the hypothesis that increasing the activity of AGP, the enzyme controlling the rate-limiting step in wheat endosperm starch biosynthesis, enhances seed sink strength and seed yield.

Our data support the conclusion that introduction of SH2R6HS into wheat enhances seed AGP activity, resulting in increased yield. This increased yield is manifested primarily as increased seed number per plant. RNA and protein analyses from developing seeds of transgenic lines indicated that the maize transgene was stably inherited across five generations in wheat (T0 through T3 in original transgenic lines and then through F2 in the T3 161–12 × Hi-Line cross). Total AGP activity and AGP activity in the presence of Pi were increased, with activity increases being greatest at the higher Pi concentrations. Enhanced AGP activity indicates that SH2R6HS competes successfully with native wheat large subunits for interaction with wheat small subunits. The increased total plant biomass in transgenic lines indicates that increased AGP activity enhances developing seed sink strength, leading to increased availability and utilization of additional resources.

A number of studies have identified conditions that affect flower survival and thus seed number in wheat (15, 16, 29–33). However, no published evidence exists on the effects of increased seed enzyme activity and sink strength on the survival of developing seeds in wheat or any other plants. Plants typically abort weakly competitive reproductive structures early in development, before the investment of significant maternal resources (34). Survival of greater numbers of seeds in the transgenic wheat lines suggests that the effect of enhanced AGP activity on seed physiology occurs very early in development. Bindraban et al. (35) concluded that increasing yield through increased seed number is most likely achievable by modification of partitioning of resources from the time of flower maturation until 1 week after anthesis. The expression pattern of the Sh2r6hs transgene is consistent with this time period, with expression observable 2 days after anthesis (data not shown). The introduced Sh2r6hs gene encodes a protein with several potentially useful properties that could account for the increased allocation of resources to developing seeds.

The first of these useful properties is conferred by the rev6 alteration of the maize large subunit. This two-amino-acid insertion results in formation of an AGP heterotetramer with decreased sensitivity to allosteric inhibition by Pi (8), which would be expected to increase AGP activity. Our finding that the elevation of AGP activity became greater as Pi concentration increased may be a manifestation of this property. The second useful property conferred by the Sh2r6hs transgene on AGP activity is likely more stable subunit interactions. This property is conferred by the HS33 amino acid alteration. This alteration in the maize AGP large subunit stabilizes interactions with the small subunit (13). The enhanced AGP activity in the absence of Pi may be a manifestation of more stable subunit interactions.

During the early stages of development, a sink may require a threshold rate of supply of resources to continue development (reviewed in ref. 28). If the supply of resources drops below the threshold, development may cease leading to seed abortion. Increases in AGP activity early in seed development could enhance sink strength enough to enable developing seeds near the threshold of abortion to survive. Developing seeds within a wheat spikelet are believed to share a common vascular connection to the maternal plant (36, 37). As a result, the first seeds to set may attract assimilates to and hence benefit later-setting seeds (38, 39). Availability of resources during seed establishment and setting is thought to be the driving force for wheat seed number determination (35). Increased AGP activity resulting from decreased sensitivity to allosteric inhibition in seeds may more effectively mobilize resources not only to themselves but also to adjacent later-setting seeds, enhancing their ability to avoid abortion.

In addition, enhancement of starch biosynthesis may stimulate photosynthesis (40). The proposed mechanism is that increasing seed sink strength may stimulate photosynthesis by pulling greater levels of sugars into developing seeds, thereby reducing feedback inhibition of leaf sugars on photosynthesis (41). Therefore, expression of the Sh2r6hs transgene may lead to stimulation of photosynthesis by reducing sugar to starch ratios in leaves. This stimulation may underlie the enhancement in seed yield and/or total plant biomass reported here.

The findings presented here are important for several reasons. To manipulate crop plant physiology for maximum productivity, a clear understanding of factors determining organ sink strength and whole-plant resource partitioning is required. In addition, it is well known that many crop plants typically abort a majority of young reproductive structures (27, 28). A prerequisite for fulfilling the genetic potential of food crops is understanding how to use reproductive capacity. Factors influencing the survival of early reproductive structures in wheat are poorly understood (35). In the experimental approach described here, genetic manipulation of seed endosperm AGP activity in wheat increased seed number per plant and total plant biomass. These results provide insight into how plant resource availability and utilization may be modified, leading to increases in yield.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tara Martin for technical assistance. We also thank Curt Hannah, Tom Greene, and Andreas Fischer for helpful discussions and critical comments on the manuscript. Research at the University of Florida is supported in part by National Science Foundation Grants IBN-9316887, IBN-960416, and MCB-9420422, and by U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Competitive Grants 94–37300-453, 97–36306-4461, 95–37301-2080, 97–01913, and 98–01006. Research at Montana State University was supported by the Montana Agricultural Experiment Station, the Montana Wheat and Barley Committee, the Consortium for Plant Biotechnology Research, Dow AgroSciences, LLC, and USDA Competitive Grant 00–03395. This is Journal Series No. 2000–63 of the Montana Agricultural Experiment Station, Montana State University–Bozeman.

Abbreviations

- AGP

ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase

- Pi

orthophosphate

- dpa

days postanthesis

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Agriculture–National Agricultural Statistics Service. Agricultural Statistics. Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hannah L C. In: Cellular and Molecular Biology of Seed Development. Larkins B A, Vasil I K, editors. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer; 1997. pp. 375–405. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Preiss J, Romeo T. Progr Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1994;47:299–329. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60255-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Espada J. J Biol Chem. 1962;237:3577–3581. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hannah L C, Nelson O E., Jr Biochem Genet. 1976;14:547–560. doi: 10.1007/BF00485834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhave M R, Lawrence S, Barton C, Hannah L C. Plant Cell. 1990;2:581–588. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.6.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bae J M, Giroux M, Hannah L C. Maydica. 1990;35:317–322. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giroux M J, Shaw J, Barry G, Cobb B G, Greene T, Okita T, Hannah L C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5824–5829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stark D M, Timmerman K P, Barry G F, Preiss J, Kishore G M. Science. 1992;258:287–292. doi: 10.1126/science.258.5080.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singletary G W, Banisadr R, Keeling P L. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1994;21:829–841. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.1.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hannah L C, Tuschall D M, Mans R J. Genetics. 1980;95:961–970. doi: 10.1093/genetics/95.4.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duke E R, Doehlert D C. Environ Exp Bot. 1996;36:199–208. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greene T W, Hannah L C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13342–13347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geiger D R, Koch K E, Shieh W. J Exp Bot. 1996;47:1229–1238. doi: 10.1093/jxb/47.Special_Issue.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer R A, Laing D R. J Agric Sci. 1976;87:113–122. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu Z, Van Sanford D A, Egli D B. Ann Bot. 1988;62:295–302. [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Block M, Botterman J, Vandewiele M, Dockx J, Thoen C, Gosselé V, Rao Movva N, Thompson C, Van Montagu M, Leemans J. EMBO J. 1987;6:2513–2518. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02537.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaw J R, Hannah L C. Plant Physiol. 1992;98:1214–1216. doi: 10.1104/pp.98.3.1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clancy M, Vasil V, Hannah L C, Vasil I K. Plant Sci. 1994;98:151–161. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weeks J T, Anderson O D, Blechl A E. Plant Physiol. 1993;102:1077–1084. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.4.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altpeter F, Vasil V, Srivastava V, Stöger E, Vasil I K. Plant Cell Rep. 1996;16:12–17. doi: 10.1007/BF01275440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lanning S P, Talbert L E, McNeal F H, Alexander W L, McGuire C F, Bowman H, Carlson G, Jackson G, Eckhoff J, Kushnak G, et al. Crop Sci. 1992;32:283–284. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bio-Rad Laboratories. Biolistic Particle Delivery PDS-COOD/He Particle Delivery System Instruction Manual. Hercules, CA: Bio-Rad Laboratories; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riede C R, Anderson J A. Crop Sci. 1996;36:905–909. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCarty D R. Maize Genet Coop Newsl. 1986;60:61. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giroux M J, Hannah L C. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;243:400–408. doi: 10.1007/BF00280470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gifford R M, Thorne J H, Hitz W D, Giaquinta R T. Science. 1984;225:801–808. doi: 10.1126/science.225.4664.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egli D B. Seed Biology and the Yield of Grain Crops. Wallingford, U.K.: Cab; 1998. pp. 70–112. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fischer R A. Crop Sci. 1975;15:607–613. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fischer R A, Stockman Y M. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1980;7:169–180. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krenzer E G, Jr, Moss D N. Crop Sci. 1975;15:71–74. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinthus M J, Millet E. Ann Bot. 1978;42:839–848. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rawson H M, Evans L T. Aust J Biol Sci. 1970;23:753–764. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stephenson A G. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1981;12:253–279. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bindraban P S, Sayre K D, Solis-Moya E. Field Crops Res. 1998;58:223–234. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zee S-Y, O'Brien T P. Aust J Biol Sci. 1971;24:35–49. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thornley J H M, Gifford R M, Bremner P M. Ann Bot. 1981;47:713–725. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cook M G, Evans L T. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1983;10:313–327. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bremner P M, Rawson H M. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1978;5:61–72. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choi S-B, Zhang Y, Ito H, Stephens K, Winder T, Edwards G E, Okita T W. In: Feeding a World Population of More than Eight Billion People: A Challenge to Science. Waterlow J C, editor. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press; 1998. pp. 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun J, Okita T W, Edwards G E. Plant Physiol. 1999;119:267–276. doi: 10.1104/pp.119.1.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]