Abstract

Biological wastewater treatment processes, such as activated sludge (AS) and aerobic granular sludge (AGS), have proven to be crucial systems for achieving both efficient waste purification and the recovery of valuable resources like poly-hydroxy-alkanoates. Gaining a deeper understanding of the microbial communities underpinning these technologies would enable their optimization, ultimately reducing costs and increasing efficiency. To support this research, we quantitatively compared classification methods differing in read length (raw reads, contigs and MAGs), overall search approach (Kaiju, Kraken2, RiboFrame and kMetaShot), as well as source databases to assess the classification performances at both the genus and species levels using an in silico-generated mock community designed to provide a simplified yet comprehensive representation of the complex microbial ecosystems found in AS and AGS. Particular attention was given to the misclassification of eukaryotes as bacteria and vice versa, as well as the occurrence of false negatives. Notably, Kaiju emerged as the most accurate classifier at both the genus and species levels, followed by RiboFrame and kMetaShot. However, our findings highlight the substantial risk of misclassification across all classifiers and databases, which could significantly hinder the advancement of these technologies by introducing noises and mistakes for key microbial clades.

Keywords: Wastewater, Microbial community, Classifications, Aerobic granular sludge, Benchmark

Subject terms: Bioinformatics, Genomic analysis, Sequencing, Biological techniques, Ecology, Environmental sciences, Ecological genetics, Microbial ecology, Molecular ecology, Restoration ecology

Introduction

The benefits derived from the industrial revolutions have fundamentally shaped modern lifestyles, enabling advancements nowadays as fundamental as the ease of reading this very paper. However, a significant downside of industrialization is the increased demand for the removal of carbon (C), nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) from municipal and industrial wastewaters1. To counterbalance the excessive production of pollutants by industrialized societies, environmental engineering has developed both artificial and biological strategies to restore ecological equilibrium. Among these, the activated sludge (AS) system and its technological evolution, the aerobic granular sludge (AGS) system, are two biological wastewater treatment methods that accelerate processes that would naturally occur over longer timescales2. Both AS and AGS rely on the collective metabolic activities of complex microbial communities, primarily composed of prokaryotes. Bacteria such as Candidatus Accumulibacter and Candidatus Competibacter, the most studied phosphate-accumulating organisms (PAOs) and glycogen-accumulating organisms (GAOs), have long been considered the primary components of AGS systems2. However, metagenomic insights have revealed that other PAOs may be better adapted to specific conditions. For instance, Tetrasphaera relies on a broad metabolic repertoire, allowing it to thrive in environments with low concentrations of readily biodegradable carbon3.

Other bacterial genera frequently identified in metagenomic surveys include Zoogloea, Pseudomonas, Thauera and Flavobacterium4. These bacteria are essential for secreting polysaccharidic matrices that embed PAO and GAO populations4 and harbor strains capable of denitrification5–7. Furthermore, the AGS granular biomass enable the co-existence of nitrifying bacteria such as Nitrosomonas and denitrifiers in different layers of the same granule2. Beyond bacteria, viruses, protozoa, and lower metazoans such as nematodes and rotifers play crucial roles in these microbial communities, as they act as bacterivores, horizontal gene transfer vectors (viruses), or contribute to biomass structuring through their movements and secretions (animals)8.

Given this complexity, a comprehensive understanding of AGS microbial communities is essential for optimizing reactor performance, accelerating maturation through targeted microbial augmentation, improving depuration efficiency, and even recovering valuable resources from waste streams4,9. For instance, various studies aim to enhance the production of poly-hydroxy-alkanoates (PHA), useful for bioplastics production, by adjusting reactor conditions to selectively enrich specific PHA-producing bacterial genera (e.g., Candidatus Accumulibacter, Thaurea and Azoarcus)4,10. However, achieving such optimization first requires a comprehensive understanding of the microbial communities involved, followed by a deeper exploration of their metabolic interactions. Total DNA sequencing is a widely used approach for comprehensive community characterization, involving the sequencing of bulk DNA extracted from reactor biomass followed by bioinformatics ecological analyses. Currently, short-read sequencing technologies dominate the market due to their high throughput, cost-effectiveness, and low error rates11. While long-read sequencing is steadily improving in both precision and throughput11, nowadays the short-read sequencing remains the most suitable method for accurately profiling the complexity of these environmental communities.

Whether that case, this approach always relies on bioinformatics classification methods the are currently known to be prone to misclassification errors12,13, particularly when analysing complex environmental samples. Moreover, most of the benchmark studies provided so far are highly biased against homo sapiens related microbiota that, although valuable in clinical research, lacks specificity in environmental settings. To support AS and AGS microbial communities researches, we evaluated various classification strategies for short-read sequencing (150 bp), including read, assembled contig and MAG based approaches. To explore different algorithmic approaches, this analysis employed four taxonomic classifiers, namely Kaiju14, Kraken215, RiboFrame16 and kMetaShot17, using multiple settings and databases. These classifiers were chosen for their proven effectiveness in their correspondent classification methodologies:

Kaiju translates nucleotide sequences into all six possible open reading frame (ORF) amino acid sequences and performs protein level matching using the Burrows-Wheeler transform14;

Kraken2 classifies sequences by analysing the frequency of distinctive k-mer patterns (sequences portions of length “k”)15;

RiboFrame extracts estimated 16S reads from whole-genome sequencing data and applies k-mer-based bayesian classification specifically to these reads using a dedicated 16S database16;

kMetaShot is a k-mer-based classifier tailored for MAGs, utilizing a custom-built database incorporating reference coding sequences, 16S rRNA and tRNA sequences from NCBI17.

The evaluation was conducted using a mock community, that, while not fully representative of the microbial complexity of AS and AGS systems, included a selection of key taxa commonly found in these environments. This design aimed to balance ecological relevance with interpretability, enabling clearer assessment of classifier performance. The mock was purposely generated in silico to control the exact clade relative abundances and avoid kitome contaminants18. The comparison considered the lack of certain taxa classification due to database limitations and, where possible, also tested custom databases ensuring the presence of relevant AS and AGS associated clades. Additionally, we assessed the risk of misclassifying higher metazoans as bacteria (and vice versa) and evaluated their removal before classification using two widely used decontamination tools, Kraken2 and Bowtie212,19.

Results

Mock processing stats

After BBDuk filtering, 46,315,875 out of 50,001,759 paired reads (92.6%) remained available for analysis. Kaiju classified between 94% (E-value 0.01 and minimal alignment length “m” = 11) and 76% of these sequences (m = 42) using either its databases, with no significant variation depending on the E-value when the m parameter was set to 30 or 42. However, between 16% (E-value 0.0001 m = 42) and 20% (E-value 0.01 and m = 11) of the additional sequences were classified as “cannot be assigned to a (non-viral) genus” by Kaiju in every setting, which did not add significant insights. Kraken2, when using the nt_core database, exhibited a strong dependency on confidence thresholds: at 0.05 confidence, it classified 51% of the reads, whereas at the highest confidence threshold tested, the classified read proportion dropped to 5%. Kraken2 with the SILVA database significantly reduced classification rates, with less than 2% of reads classified even at the most lenient thresholds. Despite using the same SILVA database, RiboFrame classified between 3000 (V3-V4 16S, confidence 0.9) and 70,000 (full length 16S, confidence 0.8) paired reads across tested settings. MetaBat2 produced 46 MAGs with the “custom” setting, 47 with the “default” setting and 48 with the “metalarge” setting. Subsequently, kMetaShot classified almost all MAGs (e.g., 41 out of 46 in case of “custom” MetaBat2 setting) when no confidence threshold was applied. However, classification decreased as the confidence threshold increased: with confidence set to 0.2 kMetaShot classified more than half of the MAGs for each setting (e.g., 24 out of 46 MAGs in case of “custom” MetaBat2 setting) while with confidence 0.4 it classified approximately a third of the MAGs (e.g., 17 out of 46 MAGs in case of “custom” MetaBat2 setting). Further details about the unclassified proportions for each tool and setting are available in the files available at the GitHub link reported in Data Availability section. Among the classifiers, RiboFrame was the least demanding in terms of RAM usage, requiring approximately 20 GB. In contrast, Kaiju and Kraken2 each required over 200 GB of RAM. The most memory-intensive approach was kMetaShot, which, when run in a multithreaded mode on MAGs, consumed 24 GB per thread.

Comparison at genus-level classification

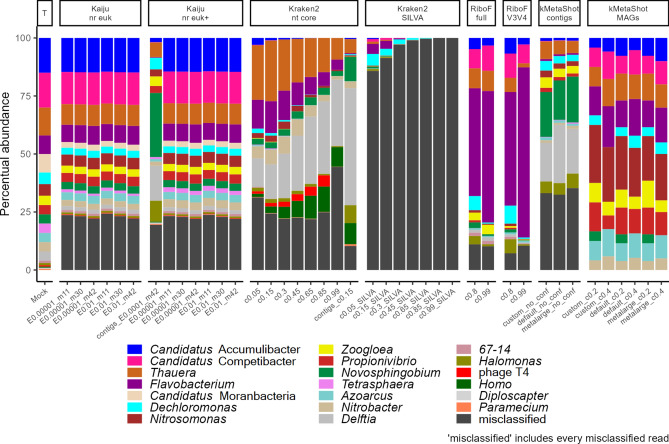

Notably, the only classifier that did not produce erroneous classifications at the genus level was kMetaShot on MAGs, regardless of the confidence levels and MEGAHIT settings (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). However, the same performance was not observed at the contig level, where many erroneous classifications and missed true genera were observed. Approximately 25% of the classifications from Kaiju and Kraken2 (using the nt core database) were erroneous, with Kaiju showing less dependence on the settings employed, while Kraken2 was strongly influenced by the confidence level (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). In fact, the percentage of misclassifications with Kraken2 increased at a confidence level of 0.99, indicating that false negative classifications (missed true genera) were more frequent than correct ones. Increasing the Kraken2 confidence level from 0.05 to 0.15 slightly reduced misclassification percentages, although fewer reads from Candidatus Accumulibacter were identified. It is noteworthy that Candidatus Competibacter was detected by Kraken2 at the lower confidence levels although just as traces. The true genus abundances inferred by Kaiju closely mirrored the actual mock proportions with both nr euk and nr euk + databases, although a few clades were missing with nr euk (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). In particular, the ratio between the relative abundances of the four most abundant genera were successfully captured by Kaiju. Both Kraken2 and Kaiju performed better on reads than on contigs. Kraken2 completely missed the true genus abundances when using the SILVA database. On the other hand, RiboFrame demonstrated the lowest percentage of misclassifications (after kMetaShot on MAGs) and captured most of the mock true abundances (after Kaiju) using the same SILVA database, although overestimating the abundance of Flavobacterium (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Bar plots depicting the relative abundances of the genera present in the mock community as estimated by various programs and parameter settings. The column “T” displays the true abundances of the clades in the mock. Genera inferred but not actually included in the mock are categorized as “misclassified”. The x-axis represents the classification types: “E” denotes the E-value threshold, “m” indicates the coverage threshold, and “c” represents the confidence level of the classification, depending on the classifier available options. The prefix “contigs” specifies classifications based on contigs rather than individual reads in case of Kaiju and Kraken2. The prefixes “default”, “metalarge” and “custom” refer to the different MEGAHIT assembly settings.

Subsequently, the overall profiling performance of the classifiers was compared (Fig. 2). Kraken2 classifications using the SILVA database were excluded from the analysis, as their estimated profiles exhibited the greatest deviation from the mock community which dominated the overall variability while obscuring differences among the other samples. When Kraken2 was applied with the nt core database, its estimated profile improved but remained different from the mock, particularly when the confidence threshold was increased or when analysis was performed at contigs level. The pipelines that most closely resembled the mock were kMetaShot on MAGs (especially with the MEGAHIT setting “metalarge”), RiboFrame on full 16S reads (with a confidence level of 0.8) and Kaiju (regardless of settings and database). As expected, RiboFrame exhibited superior performance when applied to the full 16S rRNA gene compared to a single 16S hypervariable region, although the overall classification results remained comparable. Overall, the classifications exhibited greater divergence from the mock profile as classification confidence levels increased. These results were also confirmed when the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity index was applied (Supplementary Figure S1).

Fig. 2.

PCoA plot illustrating the similarity between classification profiles based on Hellinger distance. Colors indicate the program, database, and classification level (read level by default, with additional specifications for contigs or MAGs level classifications where applicable). Labels on each point denote the specific settings used for the corresponding classification. In detail: “E” denotes the E-value threshold, “m” indicates the coverage threshold, and “c” represents the confidence level of the classification, depending on the classifier available options. The prefix “contigs” specifies classifications based on contigs rather than individual reads in case of Kaiju and Kraken2. The prefixes “default”, “large” (metalarge) and “custom” refer to the different MEGAHIT assembly settings. Labels for a few points have been omitted to avoid clutter from overlapping texts and thus to preserve the overall readability.

Additionally, the most frequent misclassifications for each pipeline were inspected (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Bar plots illustrating the relative abundances of the most abundant misclassified genera across classifications obtained using various programs and parameter settings. The displayed relative abundances account for the correct classification counts (not shown in this plot), thereby representing the total extent of misclassifications. The x-axis represents the classification types: “E” denotes the E-value threshold, “m” indicates the coverage threshold, and “c” represents the confidence level of the classification, depending on the classifier available options. The prefix “contigs” specifies classifications based on contigs rather than individual reads in case of Kaiju and Kraken2. The prefixes “default”, “metalarge” and “custom” refer to the different MEGAHIT assembly settings.

Most of the misclassifications in Kaiju were due to observations labelled as “cannot be assigned to a (non-viral) genus” by the software, summarized as “As generic virus” in Fig. 3. Excluding these, less than 4% of the reads were misclassified by Kaiju. Bradyrhizobium, Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, Sphingomonas, Stenotrophomonas and Chlamydia were among the most abundant genera incorrectly inferred by Kaiju but absent in the mock. The total amount of these misclassified genera by Kaiju, reduced to about 2% when the minimal query coverage threshold (“m”) was set to 42 (Fig. 3 and Supplementary figure S2). Moreover, increasing the stringency of Kaiju did not result in any loss of genera true positive identifications. No significant differences were observed between the overall amount of misclassifications of Kaiju on nr euk and nr euk +. Kraken2 when applied with the SILVA database erroneously assigned many reads to Pseudomonas, while Kraken2 with the nt core database continued to misclassify reads as Mycobacterium, even at higher classification confidence levels. Additionally, the misclassifications of Kraken2 on the nt core database were significantly reduced when applied at contigs level, albeit this improvement came at the expense of true positive identifications. On the other hand, kMetaShot applied at the contigs level exhibited the highest frequency of misclassifications after Kraken2 on SILVA. In contrast, RiboFrame and kMetaShot were the classifiers with the fewest misclassifications, with kMetaShot on MAGs showing no misclassified genera.

Comparison at species-level classifications

The species distribution estimated by Kaiju closely resembled that of the mock community with both nr euk and nr euk + databases, achieving even greater precision than kMetaShot at this taxonomic level (Fig. 4 and Supplementary table 3). However, Kaiju still underestimated the relative abundances of few abundant clades, such as Tetrasphaera vanveenii, Thauera sinica and Delftia spp. In contrast, Kraken2 exhibited substantial deviations from the true mock abundances, with the lower confidence threshold increasing sensitivity but leading to almost 50% of misclassified species, while the higher threshold effectively reduced misclassifications but missed reads from Candidatus Accumulibacter and Candidatus Competibacter (Fig. 4 and Supplementary table 3).

Fig. 4.

Bar plots depicting the relative abundances of the species present in the mock community as estimated by various programs and parameter settings. The column “True” displays the correct abundances of the clades in the mock. The less abundant true species are clustered as a unique observation defined “Others”. Species inferred but not actually included in the mock are categorized as “misclassified”. The x-axis represents the classification types: “E” denotes the E-value threshold, “m” indicates the coverage threshold and “c” represents the confidence level of the classification, depending on the classifier available options. The prefix “contigs” specifies classifications based on contigs rather than individual reads in case of Kaiju and Kraken2. The prefixes “default”, “metalarge” and “custom” refer to the different MEGAHIT assembly settings.

Thauera spp., Novosphingobium spp. and Flavobacterium johnsoniae were among the most frequently misclassified taxa across all settings. When disregarding relative abundances, kMetaShot at the MAGs level proved to be the most precise method for taxonomic identification within the community (Fig. 5A). This result is particularly notable when compared to Kaiju on nr euk +, which reported nearly 1600 erroneous species, and Kraken2 (with confidence threshold set at 0.99) which reported approximately 600 erroneous species (Fig. 5B). However, it is important to emphasize that most of Kaiju’s misclassifications occurred at very low relative abundances (less than 0.1%), with the exclusion of Thauera sp. and Tetrasphaera sp., with relative abundances of 1% and 1.5%, respectively. Notably, these species misclassifications still belong to clade actually featured in the mock.

Fig. 5.

Venn diagrams illustrating the species present in the mock dataset (“True” observation group) and those identified by Kaiju (E = 0.00001 and m = 42, nr euk + database), Kraken2 (confidence level = 0.99, nt core database), and kMetaShot (confidence = 0.2, executed on MAGs assembled from contigs generated by MEGAHIT with the “metalarge” option). Panel A highlights the comparison between the mock, Kaiju, and kMetaShot observations, while Panel B focuses on the comparison between the mock, Kaiju, and Kraken2 observations.

Furthermore, Fig. 5 highlights the varying sensitivities of the classifier in detecting the true mock species. Kaiju missed only 15 species, followed by Kraken2 with 157 missed species, and lastly, kMetaShot on MAGs. In particular, kMetaShot on MAGs exhibited the lowest sensitivity, missing nearly all of the true species. The 14 taxa featured in the mock but not detected by either of the classifications were species belonging to Halomonas, Novosphingobium, Thauera and Paramecium genera, although other species of the same genera were identified.

Classification performances of phage T4 and lower metazoan

The eukaryote-specific classifier, EukDetect, accurately identified 23 reads of Diploscapter spp. and did not report any misclassifications after applying its default filtering procedures. However, this high precision came at the cost of a substantial loss in sensitivity, as the majority of eukaryotic sequences remained unclassified. Notably, approximately 300 Novosphingobium aureum sequences were initially misclassified as the fungus Wolfiporia cocos by the first step of EukDetect, which relies on Bowtie2 alignment against the EukDetect database. Furthermore, Kaiju performed on the custom database constructed exclusively with lower metazoan sequences led to excessive false positives. In fact, when Kaiju was used with such focused database, despite successfully identified Paramecium and Diploscapter, it also erroneously classified many other nematodes and rotifers from bacterial and human-derived reads. For instance, reads from nearly every bacterial clade included in this mock were misclassified as Steinernema, and a substantial number of Homo sapiens reads were mistakenly assigned to nematodes. Although applying high-stringency settings significantly reduced these false positives, Kaiju’s precision on the lower metazoan database remained relatively low. On the other hand, Kaiju and Kraken2 with complete databases performed better in terms of overall sensitivity (supplementary figure S3). In fact, Kaiju with nr euk + was able to identify Diploscapter and Homo, maintaining the overall proportions between the clades despite underestimating their relative abundance (supplementary figure S3). Moreover, using Kaiju with nr euk + avoided the misclassification of Diploscapter reads as bacteria (observed with nr euk) while conversely only 137 reads of bacterial genera where incorrectly identified as Diploscapter with the most stringent settings. However, also other eukaryotic misclassifications were observed with Kaiju using the nr euk + database. For instance, a small fraction of Novosphingobium and Propionivibrio-derived reads were misclassified as Trichinella (0.003%). Similarly, bacterial and Plasmodium reads were misidentified as fungi (Termitomyces 0.003%, Wolfiporia 0.001%). Kraken2 with nt core detected Homo and Diploscapter, with only trace amounts of Diploscapter (0.009%) at the most permissive settings. However, Kraken2’s high sensitivity came at the cost of increased noise, as it misclassified Novosphingobium and Dechloromonas spp. as Wolfiporia (0.02%) and Gallus gallus (0.1%), respectively, even under the most stringent settings. Both Kraken2 and Kaiju (using either the nr_euk or nr_euk + databases) detected the T4 phage within the mock community, although with varying degrees of efficiency. Specifically, Kaiju successfully classified approximately 38% of the T4 phage reads using both m = 11 and m = 30 settings, irrespective of the E-value threshold applied. However, this proportion decreased to 34% when the m parameter was increased to 42. It is noteworthy that Kaiju would not have reported the T4 phage classification when using the nr_euk and nr_euk + databases with default settings unless the -e flag was included in the kaiju2table command, potentially leading to misleading conclusions. Furthermore, Kaiju successfully identified approximately half of the T4 phage reads when executed using the database containing only viral sequences. However, even under the most stringent settings, over 46 million sequences were misclassified as viruses within this focused database. On the other hand, Kraken2 correctly classified 67% of the T4 phage reads when the confidence threshold was set to 0.05. This proportion decreased to 38% with a threshold of 0.3 and dropped markedly at higher confidence levels as, for instance, only 0.7% of the T4 reads were identified when the highest threshold was applied.

Homo sapiens reads misclassifications as bacteria and decontamination test

Kraken2 on nt core database correctly identified about half of the Homo sapiens reads when performed on low confidence thresholds. Moreover, Kraken2 did not misclassify them as bacteria, correctly recognizing at least the correct clade (e.g., Hominidae, Bilateraria, etc.) or, at worst, it misclassified some as monkey-derived reads (e.g., Catarrhini spp.). In contrast, Kaiju, which performed well overall in the current benchmark, misclassified H. sapiens reads as bacteria (e.g. Enterococcus, Staphylococcus, Pseudomonas, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii and Escherichia coli) when used with the nr euk database. Using nr euk +, which includes Homo sapiens reads, allowed Kaiju to correctly identify few Homo reads (less than 10%) but, more importantly, to not mistaken them as bacteria. However, Kaiju frequently misidentified H. sapiens reads as Plasmodium ovale with both its databases. These misclassifications were consistent across the different Kaiju settings, although they were significantly reduced with the most stringent parameters (“E = 0.0001 and m = 42”) and when using the nr euk + database. While the total number of H. sapiens reads misclassified by Kaiju was relatively low (10,543 read pairs with nr euk and only 75 with nr euk +, under the most stringent parameters), such errors could lead to incorrect assumptions regarding the presence of certain rare taxa in the community. To address this issue, various decontamination methods for H. sapiens reads, as well as other likely eukaryotic DNA residuals originating from real wastewater, were tested before microbial community classification (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Bar plots illustrating the number of false positives (“Microbes as Homo”) and true positives (“Homo as Homo”) in the identification of Homo sapiens reads by various programs and parameter settings. The observation labelled “Total misclassific” represents the erroneous classification of microbial reads into any eukaryotic clade when the employed database includes taxa beyond Homo sapiens alone. The row labelled “Mock” indicates the actual number of H. sapiens paired reads present in the mock dataset. The program names, employed databases, and settings are displayed on the left side of the plot, while the X-axis represents the number of paired reads for each observation. The X-axis is magnified at lower values to improve readability.

Among the tested methods, Bowtie2 demonstrated the highest sensitivity in identifying H. sapiens reads while also reporting a relatively low number of false positives (i.e., microbial reads misclassified as Homo sapiens), particularly when used with end-to-end alignments which captured about 5000 paired reads misidentified as Homo. Specifically, Bowtie2’s false positives primarily consisted of misclassified Propionivibrio, Novosphingobium, Paramecium and Dechloromonas reads. Although slightly less effective, Kraken2 on the GRCh38 human database with a confidence threshold of 0.45 showed comparable performance. Kraken2 surpassed Bowtie2 in precision when the confidence threshold was increased. In fact, Kraken2 misclassified only around 200 reads, mainly from Novosphingobium and Dechloromonas, as H. sapiens at a confidence level of 0.99. However, this improvement in precision came at the expense of a significant reduction in sensitivity, as only about one-third of the true H. sapiens reads (approximately 70,000 out of 240,000) were correctly identified. Moreover, when Kraken2 decontamination was performed using a broader eukaryotic database, the total number of misclassifications increased substantially, resulting in nearly equal numbers of false positives and true positives. Specifically, a large proportion of reads originating from Flavobacterium were misclassified as Ostrinia furnacalis (a hexapod, i.e. an insect), while many Novosphingobium derived reads were incorrectly identified as belonging to the plant genus Elaeis, regardless of the confidence threshold employed.

Discussion

Current research efforts continue to investigate microbiomes using available sequencing technologies and bioinformatics workflows, however, many of these tools have been validated primarily for human-associated microbiota. Accordingly, this study aimed at systematically evaluate the advantages and limitations of commonly used taxonomic classification approaches following short-read DNA sequencing.

A considerable proportion of sequencing reads remained unclassified, even though the genomes composing the mock community were sourced from public databases, highlighting intrinsic classification limitations. The proportion of both unclassified and misclassified reads is expected to increase in real samples, given the higher complexity of real microbial communities and the presence of bacteria not represented in current databases.

Among the classifiers tested, Kaiju with either nr euk and nr euk + demonstrated the best performance, capturing the relative abundance ratios of the most prevalent genera and species. However, approximately 25% of its classifications were incorrect, with the majority assigned as “cannot be assigned to a non-generic virus”. Such classifications provide limited taxonomic resolution and are nearly as uninformative as the “unclassified” reads. While numerous misclassifications occurred with Kaiju, they were predominantly at very low relative abundances. Most of the species misclassified by Kaiju belonged to genera actually featured in the mock community, meaning that the misclassifications were taxonomically close to the expected assignment (i.e., accurate classification of the related reads was maintained till the genus level). The advantages conferred by Kaiju may stem from its in silico translation approach, which mitigates the impact of single nucleotide errors or mutations on the taxonomic classifications. Although protein databases lack non-coding genomic regions, Kaiju is expected to be relatively effective on bacterial and viral genomes as they predominantly consist of coding sequences14,17.

kMetaShot ranked as the second-best classifier in terms of overall efficiency. However, it primarily identified only the most abundant taxa while maintaining a high degree of accuracy, meaning that it obtained a high precision at cost of sensitivity. Its lack of sensitivity may be attributed to its database construction methodology, as it was primarily tested on human-associated environments rather than environmental microbiomes17. It is noteworthy that kMetaShot performed on MAGs assembled from short reads, hence both its sensitivity and precision are expected to significantly increase in case of long read sequencing.

RiboFrame’s estimation of the mock community was almost precise as Kaiju, but exhibited few misclassifications and overestimated Flavobacterium relative abundance, may due to the higher copy number of the 16S rRNA gene in its genome compared to other bacteria such as Candidatus Accumulibacter20. Kraken2, when used with the SILVA database, produced unreliable results, while RiboFrame successfully utilized the same database with minimal noise. Notably, RiboFrame had the lowest RAM requirements, confirming its suitability for short-read DNA sequencing analysis when high-performance computers are not available.

Kraken2 used on nt core database pictured a community similar to the mock, but its performance was inferior to the other tested classifiers. This outcome was unexpected, given that Kraken2 is frequently reported as one of the top-performing classifiers in human and soil microbiome studies21. Nevertheless, Kraken2 effectiveness was still confirmed as it managed to obtain unique insights, being the only classifier that successfully detected all the true genera. In detail, at a confidence threshold of 0.05 with the nt core database, Kraken2 exhibited over 25% misclassifications but still managed to identify all clades present in the mock, albeit with incorrect abundance estimations for Candidatus Accumulibacter, Zoogloea, and Candidatus Competibacter (Fig. 1).The high sensitivity of Kraken2 was also evident in its true positive rate for T4 phage derived reads, which markedly exceeded that of Kaiju when Kraken2 was employed with the lowest confidence thresholds. The observed inaccuracies are likely attributable to the database rather than the classifier itself, as many microbes associated with AS and AGS systems lack reliable reference genomes. In fact, inspecting the Kraken2 nt core highlights the under representations of many Candidatus Accumulibacter and Candidatus Competibacter species. This limitation was already reported for other Kraken 2 official databases, for example Calderón-Franco et al. found that many AGS related taxa are poorly annotated in Kraken2 standard database22.

All classifiers performed poorly when applied to contigs, suggesting suboptimal assembly. Specifically, contig-based classifications resulted in significant underestimation of many clades among which Candidatus Accumulibacter and Candidatus Competibacter, while overestimating others as Novosphingobium. Nevertheless, the contigs served as the basis for generating MAGs, which were classified with high accuracy using kMetaShot. Such contrasting outcomes suggests that the potential information obtained by assembling MAGs was greater than the noise obtained from the assembling in contigs. The most accurate MEGAHIT assembly setting resulted to be the “metalarge” mode, albeit with a marginal improvement.

As anticipated, lowering the confidence threshold increased the error rate with every classifier. However, the trade-off between reducing noise and losing valuable information was not favourable. For instance, at higher confidence thresholds, Kraken2 began to miss key species, suggesting that an optimal range its classification lies between 0.05 and 0.3 for AS and AGS related environments. Similar trends were observed for RiboFrame and kMetaShot. Conversely, Kaiju exhibited minimal changes when increasing stringency (Fig. 2) while further reducing its already low false positive rate (supplementary figure S2). Thus, increasing the minimal alignment length threshold (“m”) beyond 30 in Kaiju is suggested to further reduce its misclassifications without major losses in sensitivity when analysing 150 bp reads. However, this may result also in minimal loss of sensitivity regards certain taxa such as Rotifera, as more than 15.000 proteins known in this clade are shorter than 40 amino-acids according to the actual UniRef database23. Accordingly, such threshold should be selected based on the characteristics of the community under investigation and only after assessing the resulting unclassified reads proportion.

The classifier EukDetect2 exhibited perfect precision but suffered from extremely low sensitivity, as only few reads were recognised as Diploscapter. Similarly, Kaiju when used with the nr euk + database effectively detected eukaryotic sequences with good accuracy, albeit missing many. The inclusion of eukaryotic sequences in the classification pipeline was beneficial for every tested classifier. For example, a Kaiju-specific database containing only viral or eukaryotic sequences enhanced the classifier sensitivity but mostly increased its false positive ratios, even classifying many bacteria as eukaryotes. In contrast, Kaiju on nr euk rarely classified Homo or Diploscapter sequences as bacterial or vice versa, and was even more precise when using the nr euk +. Similarly, Kraken2 misclassified nearly all human-derived reads into the correct broad clade when using its complete database. Conversely, a comprehensive yet incomplete or unfocused database may result in a significant loss of information, as classifiers are more likely to assign reads to clades that are not actually present in the sampled environment. Such limit was observed when Kraken2 was used on the eukaryote custom database leading to numerous false positives, such as misclassifications of bacteria as insects. It is important to emphasize that the list of eukaryotes included such custom database should not be considered to be exhaustive of possible eukaryotic contaminants in wastewater, but rather as a benchmark for potential misclassifications of microbial sequences.

On the other hand, Kraken2 demonstrated superior accuracy in distinguishing human reads from bacterial sequences when using only the GRCh38 database at maximum confidence. Despite Bowtie2 achieved a significantly greater sensitivity in identify Homo reads in our simulations, also mistaken more microbial reads as human compared to Kraken2 used with 0.99 confidence. The decontamination prior to the classification would further reduce false positive classifications, as the Homo sapiens sourced reads are often mistaken for Plasmodium ovale in our simulated scenario. The likelihood of Homo sapiens DNA misclassifications were already reported in literature, for example Marcelino, Holmes and Sorrell highlighted the illogic inferring of reptiles from human gut DNA samples13. However, given the low misclassification rate of Homo sapiens reads with Kaiju (nr euk + database, stringent settings), decontamination should be carefully considered to avoid losing valuable microbial reads due to rare false positives Homo reads. Consequently, the optimal strategy may depend on sequencing depth (as bacterial reads are typically more abundant than animal or plant derived contaminants) and the nature of the influent feeding the reactor (i.e. real or synthetic wastewater). In real wastewater influent scenarios, particularly those originating from domestic sources, in silico decontamination of human reads using Kraken2 with a focused database at a high confidence threshold may be a viable strategy.

Overall, the results highlighted the risks of placing blind trust in classification outputs, particularly when interpreting low-abundance taxa. For instance, rare Dechloromonas reads were erroneously classified as Gallus gallus despite the application of high stringency thresholds, and fungal taxa were inferred despite their absence from the simulated community. While the former misclassification might be reasonably disregarded in practical scenarios due to its implausibility, the latter could misleadingly suggest the presence of fungi in the reactor.

Although we consider the reported observations essential for interpreting analyses of AS and AGS microbiota, the manuscript still presents unavoidable limitations that readers should carefully take into account:

Due to the intentionally simplified design of the simulated mock community, it is not possible to define abundance thresholds. Nonetheless, the application of filtering thresholds previously proposed in the literature, such as 0.005% at species level21,24 (calculated including unclassified reads in the total) is still suggested.

The mock community, for the same reason outlined above, could not encompass the numerous key taxa representative of AS and AGS systems;

Benchmarking all the classifiers available in the literature is clearly unfeasible, hence focused our tests on one representative classifier per major classification strategy.

Methods

Mock generation

Reference genomes of 14 bacterial genera frequently observed in AGS and activated sludge microbial communities were downloaded from NCBI RefSeq using NCBI Datasets v16.22.0. Additionally, genomes of Candidatus Moranbacteria and Solirubrobacter bacterium 67–1425,26, which have also been reported in AGS and activated sludge studies, were retrieved from GenBank, as these genera lack official reference genomes. To incorporate microbial eukaryotes and bacteriophages, the reference genomes of Diploscapter spp., Paramecium spp. and a T4 bacteriophage species were also included. Notably, Paramecium spp. were selected as they are the only ciliates with reference genomes available in the NCBI RefSeq database as well as members of the Vorticellaceae family that currently lack genomic data in both RefSeq and GenBank. Furthermore, the reference genome of Homo sapiens was downloaded to account for potential traces of eukaryotic DNA originating from reactor influents. In total, genomes from 20 taxa (16 bacteria, 3 eukaryotes, and 1 virus) were collected. The full list of selected genera is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of genera featured in the mock.

| Domain | Genus | Synonym | Reads counts | Reads percentages | Main role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Candidatus Accumulibacter | 7,500,159 | 15 | PAO | |

| Bacteria | Candidatus Competibacter | 7,499,920 | 15 | GAO | |

| Bacteria | Thauera | 6,000,210 | 12 | Heterotrophic | |

| Bacteria | Flavobacterium | 4,000,000 | 8 | Heterotrophic | |

| Bacteria | Candidatus Moranbacteria | Candidatus Moraniibacteriota | 3,999,999 | 8 | Heterotrophic |

| Bacteria | Dechloromonas | 2,500,038 | 5 | PAO | |

| Bacteria | Nitrosomonas | 2,500,189 | 5 | Nitrifying | |

| Bacteria | Zoogloea | 1,999,647 | 4 | Heterotrophic | |

| Bacteria | Propionivibrio |

Candidatus Propionivibrio (at species level) |

1,999,980 | 4 | Autotrophic |

| Bacteria | Novosphingobium | 2,000,782 | 4 | Heterotrophic | |

| Bacteria | Tetrasphaera | Nostocoides | 1,999,944 | 4 | PAO |

| Bacteria | Azoarcus | 1,999,998 | 4 | Autotrophic | |

| Bacteria | Nitrobacter | 1,999,951 | 4 | Nitrifying | |

| Bacteria | Delftia | 1,999,998 | 4 | Nitrifying | |

| Bacteria | 67–14 | Solirubrobacterales bacterium 67–14 | 500,004 | 1 | Heterotrophic |

| Bacteria | Halomonas | 500,688 | 1 | Halophilic | |

| none | Phage T4 | Tequatrovirus | 250,000 | 0.5 | Predator |

| Eukaryota | Homo | 250,275 | 0.5 | – | |

| Eukaryota | Diploscapter | 249,997 | 0.5 | Predator | |

| Eukaryota | Paramecium | 249,980 | 0.5 | Predator |

The column “Synonym” indicates taxon names as listed in the NCBI database when they differ from those in other databases (e.g. SILVA). The “Read Counts” column presents the raw number of paired reads assigned to each clade in the mock dataset, while “Read Percentages” represents their relative abundance. The “Main role” column reports the most known role or characteristic of that clade in AS or AGS environments and it is not intended to be a comprehensive summary of the clade’s potential functions or characteristics.

Simulated untargeted sequencing of these genomes was performed using InSilicoSeq (ISS) v2.0127, emulating sequencing via Illumina NovaSeq. This resulted in 150 bp paired-end reads at a total depth of 50 million paired reads. The seed 1994 was employed to ensure the full reproducibility of the results (see data availability). The sequencing simulation was designed to generate precise relative abundances for each taxon, as detailed in Table 1.

Notably, the simulated mock community comprises a few predominant bacterial taxa, with others taxa present at lower abundances, thereby reflecting realistic microbial community structures. In particular, Candidatus Accumulibacter and Candidatus Competibacter were the most abundant bacteria, leading to an abundance distribution r resembling AGS communities more than AS communities2. For sake of reading simplicity, the genera featured in the mock will be referred to as “true genera” in this paper.

Processing and classifying the mock reads

The mock reads were filtered through using BBDuk (module of BBTools suit version 39.06)28 to remove reads sourced from Illumina adapters or phiX, very-low complexity sequences with entropy value less than 0.01 (“entropy = 0.01”), 3' ends regions with Q-score lower than 20 (“qtrim = r”, “trimq = 20”) and reads shorter than 100 bp (“minlen = 100”) while taking into account the in paired-end nature of the sequencing (“tpe”, “tpo”). This pre-processing step was intentionally disregarded when comparing the estimated abundances with the known original ones, in order to incorporate actual sequencing biases into this benchmark. The filtered reads were classified as such or after being assembled into contigs or metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs). Contigs were assembled using MEGAHIT v1.2.929 under three different settings: “default”, “meta-large” and “custom” (the latter employing a k-mer list of 35, 57, 79, 99, as used in the kMetaShot study17). MAGs were subsequently reconstructed from the contigs for each setting using MetaBat v2.1730. The MAG assembly followed the same settings as in the kMetaShot study17 to ensure full compatibility with this classifier, as the MAGs identification was tested exclusively with kMetaShot.

The classification was carried out with the widely used Kraken v2.1.215 with various confidence levels, Kaiju v1.1014 with different E-value and minimal coverage thresholds, RiboFrame v 1.016 with different confidence thresholds applied to both the full-length 16S rDNA and its V3-V4 hypervariable region featured among the reads, and kMetaShot v1.017 with multiple confidence levels. Bracken 2.7.031 was used to re-estimate the abundances of the Kraken2 identified taxa according to their genome length and sequenced read length. In particular, the classification at read level was conducted with RiboFrame, Kaiju, and Kraken2, at contigs level with Kaiju, Kraken2, and kMetaShot and at MAG level with kMetaShot. The analysis at the contig level using kMetaShot was conducted for each kMetaShot setting described above, whereas classifications with Kaiju and Kraken2 (on “nt core” database) were performed exclusively on contigs generated with the MEGAHIT ‘metalarge’ option to avoid unnecessarily convoluted comparisons between the various settings combinations. Moreover, the confidence thresholds were not used when classifying at contig level with kMetaShot as almost every related confidence score was near zero.

Kraken2 was used with both the “nt core” (built on December 28, 2024) and SILVA 138 official databases. Kaiju was tested with the “nr euk” and “nr euk plus” (referred to as “nr euk +”) databases. The nr euk database, built in October 2023, is the most recent official distribution including bacteria, archaea, viruses, protozoa and fungi. In contrast, nr euk + is a customized version of this database, built with the most recent NCBI nr available (April 2024) and expanded to incorporate nr sequences from Platyhelminthes, Nematoda, Amoeba, Rotifera, Tardigrada and Homo sapiens. In detail, the flag -e was included in the kaiju2table command to ensure that the classification of the T4 phage was displayed in Kaiju outputs. RiboFrame relied on the RDP classifier retrained on SILVA SSU 138. kMetaShot employed its own database, downloaded in February 2025. Clades without official genus name in NCBI (e.g. Candidatus Moranbacteria) were obtained from the species classifications and added to the genus level outputs to reduce the database biases in the genus level comparison. A comprehensive list of all program, parameter, and database combinations used in this analysis is provided in Supplementary table 1.

Comparison between classifiers outcomes

The estimated microbial abundances in the mock datasets were compared across different settings using R v4.3, with the packages vegan v2.6.432 and ecodist v2.1.333. Data visualization was performed using ggplot v3.4.4, ggvenn v0.1.10, and ggh4x v0.2.7. Synonymies across the employed databases were manually resolved, at least for the known genera included in the mock and the most abundant misclassifications, through accurate searches in List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) database34. Importantly, the unclassified reads were not included in the percent abundances computation, hence the analysis was focused on the classifier-specific classifications. Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) was conducted using the Hellinger distance, i.e. the Euclidean distance applied to Hellinger-transformed abundances, to account for the sparse and compositional nature of the data35. Additionally, the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity index, applied to proportional data, was used as an alternative ecological measure to ensure that the PCoA related conclusions were not influenced by the choice of ecological distance. The most abundant misclassifications for each setting were identified by computing the average abundances of taxa that were incorrectly assigned as not actually present in the mock. All the analyses were primarily conducted at the genus level across all described settings, with additional species-level insights obtained by comparing Kaiju outputs at the reads level (using both the databases with settings E = 0.00001 and m = 42), Kraken2 at the reads level (using the nt core database with confidence thresholds of 0.15 and 0.99) and kMetaShot at the MAGs level (after contigs assembly through MEGAHIT with “metalarge” option). These programs and settings were specifically chosen for the comparison at species levels as theoretically capable of providing such taxonomic detail and due to their generally accurate performances at genus level.

Focus on non-prokaryotes derived reads

In addition to the listed software and parameter combinations used for classifying the bulk community, additional analyses were conducted to specifically assess potential misclassifications of non-prokaryotic reads. Read-level classification was performed using Kaiju v1.10 with the pre-built viral sequence database from RefSeq to further investigate false negative classifications of this clade observed in the full database. Additionally, Kaiju was executed with a custom database constructed by selecting only common metazoan sequences found in activated sludge (i.e. Rotifers, Platyhelminths, Nematodes, Amoebae and Tardigrades) from the UniRef100 protein database. Furthermore, EukDetect v1.336 was applied to unfiltered reads using its default database, EukDetect database v9, which has included lower metazoans since recent releases. Finally, an additional attention was spent on misclassifications of Homo sapiens reads as bacteria. The identification of Homo sapiens reads (as optional decontamination step prior to the actual microbes’ classification) was performed with Kraken2 on both GRCh38 reference genome37 and a custom database on diverse confidence levels, and with Bowtie219 in paired-end mode with the “very-sensitive” option using both local alignment and end-to-end alignment. The custom database used in Kraken2 was constructed from the reference genomes of various higher eukaryotes whose residual DNA fragments are likely to be present in wastewater feeding AGS and AS reactors, including Hexapoda, Annelida, Chlorophyta, plants (Kraken2 reference sequences), Homo sapiens and Mus musculus.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge PRIN 2022 project N4En - B53D23005590006 - 20228AF8JN for financial support.

Author contributions

D.L.: design, analysis and writing. L.C.: review and editing. T.L.: review and editing. R.M.: supervision, review and editing.

Data availability

The simulated mock community raw FASTQ are publicly available on NCBI SRA with the accession code PRJNA1252002. The resulting counts and classifications for each classifier and parameter, as well as the unclassified percentages, the R data containing the feature table ready for the analysis and the scripts, are available at https://github.com/LeandroD94/Papers/tree/main/2025_Benchmark_DNAseq_classifiers_AGS_and_AS.

Declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

8/21/2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: The Acknowledgements in the original version of this Article were omitted. The section now reads: “The authors acknowledge PRIN 2022 project N4En - B53D23005590006 - 20228AF8JN for financial support.”

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-07734-8.

References

- 1.Robles, Á. et al. New frontiers from removal to recycling of nitrogen and phosphorus from wastewater in the Circular Economy. Biores. Technol.300, 122673. 10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122673 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campo, R. et al. Efficient carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus removal from low C/N real domestic wastewater with aerobic granular sludge. Biores. Technol.305, 122961. 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.122961 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang, Y. et al. A review of the phosphorus removal of polyphosphate-accumulating organisms in natural and engineered systems. Sci. Total Environ.912, 169103. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.169103 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winkler, M.-K.H. et al. An integrative review of granular sludge for the biological removal of nutrients and recalcitrant organic matter from wastewater. Chem. Eng. J.336, 489–502. 10.1016/j.cej.2017.12.026 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su, J. F., Li, G. Q., Huang, T. L. & Xue, L. The mixotrophic denitrification characteristics of Zoogloea sp. L2 accelerated by the redox mediator of 2-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone. Bioresour. Technol.311, 123533. 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.123533 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang, M., Li, A., Yao, Q., Xiao, B. & Zhu, H. Pseudomonas oligotrophica sp. Nov., a novel denitrifying bacterium possessing nitrogen removal capability under low carbon-nitrogen ratio condition. Front. Microbiol.10.3389/fmicb.2022.882890 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ye, J. et al. Denitrifying communities enriched with mixed nitrogen oxides preferentially reduce N2O under conditions of electron competition in wastewater. Chem. Eng. J.498, 155292. 10.1016/j.cej.2024.155292 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilén, B. M., Liébana, R., Persson, F., Modin, O. & Hermansson, M. The mechanisms of granulation of activated sludge in wastewater treatment, its optimization, and impact on effluent quality. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.102, 5005–5020. 10.1007/s00253-018-8990-9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ekholm, J. et al. Microbiome structure and function in parallel full-scale aerobic granular sludge and activated sludge processes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.108, 334. 10.1007/s00253-024-13165-8 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falcioni, S. et al. in Resource Recovery from Wastewater Treatment. (eds Giorgio Mannina, Alida Cosenza, & Antonio Mineo) 140–146 (Springer).

- 11.Adewale, B. A. Will long-read sequencing technologies replace short-read sequencing technologies in the next 10 years?. Afr. J. Lab. Med.9, 1340. 10.4102/ajlm.v9i1.1340 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bush, S. J., Connor, T. R., Peto, T. E. A., Crook, D. W. & Walker, A. S. Evaluation of methods for detecting human reads in microbial sequencing datasets. Microb. Genomics10.1099/mgen.0.000393 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ten Chorlton, S. D. common issues with reference sequence databases and how to mitigate them. Front. Bioinformat.4, 1278228. 10.3389/fbinf.2024.1278228 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menzel, P., Ng, K. L. & Krogh, A. Fast and sensitive taxonomic classification for metagenomics with Kaiju. Nat. Commun.7, 11257. 10.1038/ncomms11257 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wood, D. E., Lu, J. & Langmead, B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol.20, 257. 10.1186/s13059-019-1891-0 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramazzotti, M., Berná, L., Donati, C. & Cavalieri, D. riboFrame: an improved method for microbial taxonomy profiling from non-targeted metagenomics. Front. Genet.6, 329. 10.3389/fgene.2015.00329 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Defazio, G., Tangaro, M. A., Pesole, G. & Fosso, B. kMetaShot: a fast and reliable taxonomy classifier for metagenome-assembled genomes. Brief. Bioinformat.10.1093/bib/bbae680 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Gloria, L. et al. Experimental tests challenge the evidence of a healthy human blood microbiome. FEBS J.292, 796–808. 10.1111/febs.17362 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods9, 357–359. 10.1038/nmeth.1923 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dueholm, M. K. D. et al. MiDAS 5: Global diversity of bacteria and archaea in anaerobic digesters. Nat. Commun.15, 5361. 10.1038/s41467-024-49641-y (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwin, N. R., Fitzpatrick, A. H., Brennan, F., Abram, F. & O’Sullivan, O. An in-depth evaluation of metagenomic classifiers for soil microbiomes. Environ. Microbiome19, 19. 10.1186/s40793-024-00561-w (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calderón-Franco, D. et al. Metagenomic profiling and transfer dynamics of antibiotic resistance determinants in a full-scale granular sludge wastewater treatment plant. Water Res.219, 118571. 10.1016/j.watres.2022.118571 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The UniProt, C. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res.53, D609–D617. 10.1093/nar/gkae1010 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amos, G. C. A. et al. Developing standards for the microbiome field. Microbiome8, 98. 10.1186/s40168-020-00856-3 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gu, Y., Li, B., Zhong, X., Liu, C. & Ma, B. Bacterial community composition and function in a tropical municipal wastewater treatment plant. Water14, 1537 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xin, Z., Yang, L. & Yang, L. Divergences of granules and flocs microbial communities and contributions to nitrogen removal under varied carbon to nitrogen ratios. Biores. Technol.425, 132226. 10.1016/j.biortech.2025.132226 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gourlé, H., Karlsson-Lindsjö, O., Hayer, J. & Bongcam-Rudloff, E. Simulating Illumina metagenomic data with InSilicoSeq. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England)35, 521–522. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty630 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bushnell, B., Rood, J. & Singer, E. BBMerge—accurate paired shotgun read merging via overlap. PLoS ONE12, e0185056–e0185056. 10.1371/journal.pone.0185056 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li, D., Liu, C. M., Luo, R., Sadakane, K. & Lam, T. W. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England)31, 1674–1676. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv033 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang, D. D. et al. MetaBAT 2: an adaptive binning algorithm for robust and efficient genome reconstruction from metagenome assemblies. PeerJ7, e7359. 10.7717/peerj.7359 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu, J., Breitwieser, F. P., Thielen, P. & Salzberg, S. L. Bracken: Estimating species abundance in metagenomics data. PeerJ Comput. Sci.10.1101/051813 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vegan: Community Ecology Package (2017).

- 33.Goslee, S. C. & Urban, D. L. The ecodist package for dissimilarity-based analysis of ecological data. J. Stat. Softw.22, 1–19. 10.18637/jss.v022.i07 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parte, A. C., Sardà Carbasse, J., Meier-Kolthoff, J. P., Reimer, L. C. & Göker, M. List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) moves to the DSMZ. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol.70, 5607–5612. 10.1099/ijsem.0.004332 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Legendre, P. & Legendre, L. Chapter 7—Ecological Resemblance, Vol. 24, 265–335 (2012).

- 36.Lind, A. L. & Pollard, K. S. Accurate and sensitive detection of microbial eukaryotes from whole metagenome shotgun sequencing. Microbiome9, 58. 10.1186/s40168-021-01015-y (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneider, V. A. et al. Evaluation of GRCh38 and de novo haploid genome assemblies demonstrates the enduring quality of the reference assembly. Genome Res.27, 072116. 10.1101/072116 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The simulated mock community raw FASTQ are publicly available on NCBI SRA with the accession code PRJNA1252002. The resulting counts and classifications for each classifier and parameter, as well as the unclassified percentages, the R data containing the feature table ready for the analysis and the scripts, are available at https://github.com/LeandroD94/Papers/tree/main/2025_Benchmark_DNAseq_classifiers_AGS_and_AS.