Abstract

Background:

Zilucoplan, a peptide complement component 5 (C5) inhibitor, is self-administered as a subcutaneous (SC) injection, which offers an alternative to intravenous infusion of antibody-based complement C5 inhibitors.

Objective:

To evaluate subcutaneous zilucoplan in adults with acetylcholine receptor autoantibody-positive generalised myasthenia gravis (gMG) who switched from intravenous complement C5 inhibitors to zilucoplan.

Design:

MG0017 (NCT05514873) was a phase IIIb, open-label, single-arm study.

Methods:

Eligible patients had clinically stable gMG on an intravenous complement C5 inhibitor and were willing to switch to zilucoplan. Patients received a 12-week treatment period of daily subcutaneous zilucoplan 0.3 mg/kg. Incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) was the primary endpoint. Change from baseline in the Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living (MG-ADL) score at Week 12 was a secondary endpoint. Treatment preference (Week 12) and treatment satisfaction (9-item Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM-9)) were both exploratory endpoints. Assessments by prior intravenous complement C5 inhibitor were conducted post hoc.

Results:

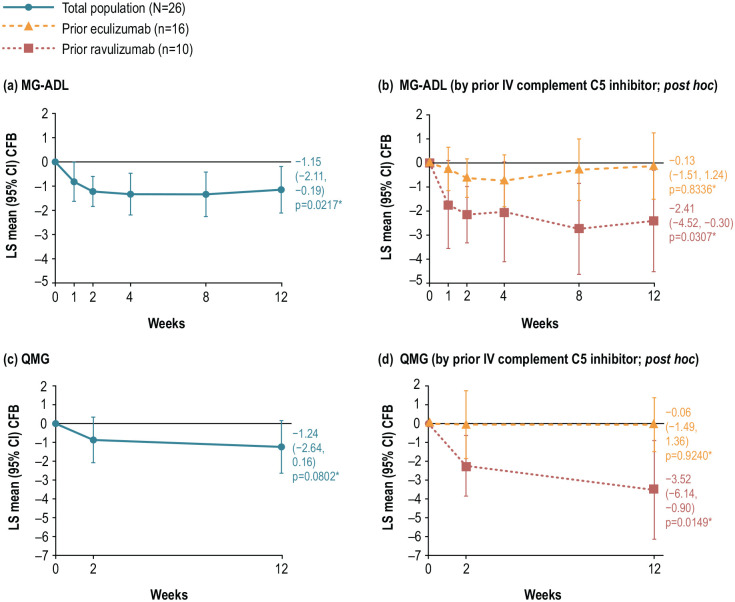

Twenty-six patients enrolled and received zilucoplan; 16 switched from eculizumab and 10 from ravulizumab. TEAEs occurred in 19/26 (73.1%) patients and were mostly mild in severity. At Week 12, least squares (LS) mean (95% confidence interval) MG-ADL scores improved from baseline by −1.15 (−2.11, −0.19), p = 0.0217 and Quantitative MG (QMG) scores by −1.24 (−2.64, 0.16), p = 0.0802. Clinically meaningful improvement from baseline in mean MG-ADL and QMG scores was observed at Week 12 among patients who switched from ravulizumab (−2.41 (−4.52, −0.30; p = 0.0307) and −3.52 (−6.14, −0.90; p = 0.0149), respectively). At Week 12, 76.9% (n = 20) patients preferred subcutaneous injection compared with intravenous infusion. Mean (standard deviation) changes from baseline in the TSQM-9 Global Satisfaction, Effectiveness and Convenience subscores at Week 12 were +19.410 (27.429), +13.889 (21.534) and +21.739 (19.955), respectively. Complement inhibition increased from baseline and was complete (>95%) by Week 2 and maintained to Week 12.

Conclusion:

Zilucoplan demonstrated a favourable safety profile. gMG symptoms improved during zilucoplan treatment; this was clinically meaningful for those switching from ravulizumab.

Trial registration:

ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05514873); 22 August 2022. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05514873

Keywords: complement inhibitor, eculizumab, myasthenia gravis, ravulizumab, zilucoplan

Plain language summary

Experiences of patients with myasthenia gravis who switched their treatments from intravenous infusions of ravulizumab or eculizumab to self-administered daily injections of zilucoplan: effects on symptoms, safety, and patient preference

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a chronic autoimmune disease. Complement, part of the immune system, is overactive in MG. This damages the connections between muscles and nerves, causing muscle weakness. Symptoms can be reduced by blocking complement activity. Ravulizumab and eculizumab are complement inhibitors that are given as intravenous (into a vein) infusions by a healthcare professional in a hospital or clinic. Zilucoplan is another type of complement inhibitor, which patients can inject subcutaneously (under the skin) themselves. This study followed patients with MG who wanted to switch from ravulizumab or eculizumab to zilucoplan. Side effects were recorded throughout the study. Patients’ symptoms were measured to see if there was any change since switching treatment. All 26 patients who enrolled in the study had stable symptoms with their current treatment (which was ravulizumab in 10 patients, and eculizumab in 16 patients). Once enrolled, patients switched to daily zilucoplan for 12 weeks. Their main reasons for wanting to switch treatment were challenges with intravenous infusions, including travelling to hospital and long infusion times. Some patients also felt their current treatment was wearing off. After 12 weeks of zilucoplan treatment, symptoms across the group as a whole had improved. Symptoms had either improved or stayed the same in approximately 75% of patients. Symptom improvements were greatest in patients who switched from ravulizumab to zilucoplan. At the end of the study, 76.9% (20 out of 26) patients said they preferred injections with zilucoplan to intravenous infusions of their previous treatment. Side effects occurred in 73.1% of patients, which were mostly mild. Although the study was short and limited to a small number of patients, the results suggest that switching to zilucoplan is an option for patients with MG who would prefer self-injections to intravenous infusions. Longer-term studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Introduction

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a chronic autoimmune disorder, characterised by fluctuating skeletal muscle weakness and exertional muscle fatigue. MG is caused by autoantibodies against the acetylcholine receptor (AChR), or other functionally important molecules, in the postsynaptic membrane at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ).1,2 These pathogenic autoantibodies initiate complement-mediated architectural damage of the NMJ, and therefore targeting the complement cascade has been shown to be an effective treatment strategy in MG.3–6

Eculizumab and ravulizumab are humanised monoclonal antibodies that bind to complement component 5 (C5) with high affinity to inhibit complement C5 cleavage into C5a and C5b, which prevents downstream formation of the membrane attack complex and thus damage to the NMJ.4,6 Both molecules are approved for the treatment of AChR autoantibody-positive (Ab+) generalised MG (gMG) in adults, and are administered intravenously by a healthcare professional (HCP) either every 2 weeks (eculizumab) or every 8 weeks (ravulizumab).7,8

Zilucoplan, a 15-amino acid macrocyclic peptide, targets the complement pathway with a dual mechanism of action. In addition to preventing the cleavage of complement C5 to C5a and C5b, zilucoplan also binds to the C5b domain of C5, thereby preventing any nascent C5b from binding to C6.9,10 Zilucoplan is also the first and currently the only complement C5 inhibitor for gMG that patients can self-administer as a subcutaneous (SC) injection.5,10,11 The phase III, open-label extension RAISE-XT study of zilucoplan in gMG has thus far shown that daily injection results in sustained efficacy and complement inhibition through to 60 weeks.5,11 In addition, there are data to suggest that patients with chronic conditions may prefer SC self-administration to HCP-administered intravenous (IV) infusions.12,13 In a meta-analysis of studies reporting preference for SC or IV treatment administration in patients with autoimmune diseases, including MG, 83% of patients preferred the SC route. Further, 84% of patients preferred at-home treatment administration compared with in-hospital administration. 13 There are many cited reasons for this preference toward at-home SC treatment administration, including challenges with logistics (travelling to and from hospitals), economic issues (time off work, travel expenses) and venous access issues. 12

MG0017 (NCT05514873) aimed to evaluate safety, efficacy, patient preference and satisfaction with switching from IV complement C5 inhibitors to SC zilucoplan in adults with AChR Ab+ gMG.

Methods

Study design

MG0017 was a phase IIIb, open-label, multicentre, single-arm study, consisting of a 12-week main treatment period of daily SC zilucoplan 0.3 mg/kg following a switch from an IV complement C5 inhibitor (Figure 1). The study included a 2- or 8-week screening period for patients switching from eculizumab or ravulizumab, respectively, based on the approved treatment regimens,7,8,14,15 so that all patients received their first dose of zilucoplan on the day they were due to receive their next dose of eculizumab or ravulizumab. At the end of the screening period, patients entered the 12-week main treatment period, receiving their first dose of SC zilucoplan on Day 1. Following in-clinic education and training, patients were provided with single-use pre-filled syringes to self-administer 0.3 mg/kg zilucoplan daily for 12 weeks. There was no washout period before treatment switch to ensure patients were continuously receiving complement-inhibiting gMG treatment. At the end of the 12-week main treatment period, patients could enter an optional extension period. Here, results are presented from the 12-week main treatment period only.

Figure 1.

Study design.

*In-clinic visits. Weeks 1, 4 and 8 were telephone appointments.

C5, component 5; IV, intravenous; SC, subcutaneous.

Study population

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were aged 18–85 years with a documented diagnosis of AChR Ab+ gMG and severity of Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America Disease Class II–IVa at screening. Patients were to have clinically stable disease per the investigator’s judgement, with no more than a 2-point change in Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living (MG-ADL) score at baseline compared with their screening visit. Patients must also have been receiving an IV complement C5 inhibitor approved for the treatment of gMG at the recommended dose regimen for at least 3 months (eculizumab) or 4 months (ravulizumab) prior to screening and be willing to switch to zilucoplan. Patients were allowed to take concomitant corticosteroids or immunosuppressive therapies for gMG provided the patient had no change in dose or in immunosuppressive therapy during the screening period, and that no change in dose or in immunosuppressive therapy was expected to occur during the 12-week main treatment period. Patients were vaccinated against Neisseria meningitidis.

Patients were excluded if they had: thymectomy within 6 months prior to baseline or thymectomy scheduled during the 12-week main treatment period; history of meningococcal disease; current or recent systemic infection within 2 weeks prior to baseline or an infection requiring IV antibiotics within 4 weeks prior to baseline; treatment with rituximab within 6 months prior to baseline; treatment with IV or SC immunoglobulin (Ig) or plasma exchange (PLEX) within 4 weeks prior to baseline or treatment with an experimental drug within 30 days, or 5 half-lives of the experimental drug, whichever was longer. All patients provided written informed consent.

Assessments

The primary safety endpoints were incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) and incidence of TEAEs leading to treatment discontinuation. Safety was also assessed by physical examination, electrocardiogram and other measurements of vital signs, and clinical laboratory assessments.

The secondary efficacy endpoint was to demonstrate the non-inferiority of change from baseline (CFB) to Week 12 in MG-ADL total score. MG-ADL is an eight-item patient-reported outcome designed to evaluate MG symptom severity. The scale assesses ocular, bulbar, respiratory and axial symptoms, each scored on a 4-point scale (0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate and 3 = severe). The total score is the sum of the eight individual scores, ranging from 0 to 24. A 2-point change in MG-ADL score is considered clinically meaningful.16,17

Efficacy was also measured by CFB in Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis (QMG) and revised 15-item Myasthenia Gravis Quality of Life (MG-QoL 15r) total scores to Week 12, MG-ADL and QMG score responder rates (defined as achieving a ⩾3-point and ⩾5-point reduction from baseline score, respectively, without rescue therapy) at Week 12 and time to first receipt of rescue therapy. QMG includes clinician- and patient-assessed swallowing, speech, limb strength, ocular and facial involvement, and forced vital capacity. Each of the 13 items is scored on a 4-point scale (0 = no impairment, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate and 3 = severe impairment), and the total score is the sum of the individual scores, ranging from 0 to 39. A 3-point change in QMG score is considered clinically meaningful in a typical clinical study population of patients with MG.18,19 MG-QoL 15r is a 15-item patient-reported outcome designed to assess quality of life in patients with MG. Higher scores indicate more severe impact of the disease on aspects of the patient’s life. Fifteen items are scored on a 3-point scale (0 = not much at all, 1 = somewhat, 2 = very much), and the total score ranges from 0 to 30. 20 There is currently no established threshold for clinical meaningful improvement in MG-QoL 15r score.

Patient treatment satisfaction was assessed using the 9-item Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire of Medication (TSQM-9). The TSQM-9 is a self-administered, disease-agnostic, patient-reported outcome designed to assess satisfaction with a medication over three domains: Global Satisfaction, Effectiveness and Convenience. Each domain score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction. A change of 9.99 points for effectiveness, 10.81 points for convenience and 12.24 points for satisfaction are considered meaningful. 21 These published meaningful change thresholds were determined using TSQM v1.4. Because the Global Satisfaction, Effectiveness and Convenience domains and scoring in TSQM v1.4 are the same as those used in TSQM-9, the use of these thresholds here is considered appropriate. Further substantiation of the use of these thresholds and additional supporting threshold calculations based on the current dataset can be found in Supplemental Table 1. Qualitative and psychometric testing have shown the TSQM-9 to be valid and reliable.22,23 Mean scores were assessed at baseline, reflecting treatment satisfaction for the prior complement C5 inhibitor treatment, and at Week 12 for zilucoplan, in the three domains.

To determine the overall patient preference for IV or SC treatment, patients were asked the following question at Week 12: ‘Think about your experience of the subcutaneous treatment you received during the clinical trial compared with your previous intravenous treatment. All things considered, which treatment did you prefer (please select one answer)?’ Patients could answer either ‘intravenous infusion’, ‘subcutaneous injection’ or ‘no preference’.

The time needed for patients to administer zilucoplan (i.e. the time it takes for the dose to be delivered) was measured at Week 2 and Week 12 by site staff, who started a stopwatch at the removal of the pre-filled syringe needle cap and stopped once the syringe was completely removed from the skin following the injection.

A sheep red blood cell (sRBC) lysis assay was used to evaluate classical component pathway activation and complement inhibition at baseline, Week 2 and Week 12. The pharmacokinetic endpoint was plasma concentrations of zilucoplan at Week 2 and Week 12. Blood samples for pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic analyses were obtained at these visits within 1 h prior to zilucoplan dosing.

Post hoc analyses by prior IV complement C5 inhibitor were also performed for efficacy (CFB in MG-ADL, QMG and MG-QoL 15r to Week 12; MG-ADL and QMG responder analyses), treatment satisfaction (TSQM-9) and complement inhibition (by sRBC lysis assay).

Statistical analyses

The sample size calculation was based on the non-inferiority assumption of MG-ADL score at Week 12 versus MG-ADL score at baseline. For the calculations, it was assumed that the CFB in MG-ADL score at Week 12 has a standard deviation (SD) of 3. Under the null hypothesis that the Week 12 MG-ADL score is inferior to the baseline MG-ADL score by more than 2 points (non-inferiority margin = 2), a sample size of 20 participants would provide at least 80% power to reject the null hypothesis with a one-sided alpha of 0.025.

For continuous parameters, descriptive statistics included the number of study participants, arithmetic mean, SD and median. For categorical parameters, the number and percentage of study participants in each category are presented. Safety analyses were performed on the safety set, comprising all study participants who received at least one dose of study medication. Efficacy analyses were performed on the modified intention-to-treat (mITT) population, comprising all study participants who received at least one post-baseline dose of study medication and had at least one post-baseline assessment.

For the efficacy endpoint of CFB in MG-ADL score at Week 12, a mixed model for repeated measures (MMRM) was used to estimate the least squares (LS) mean and 95% confidence intervals (CI). The MMRM included MG-ADL scores at baseline and Weeks 1, 2, 4, 8 and 12 as fixed variables and baseline MG-ADL score by visit as the interaction term. An unstructured covariance matrix was used. The LS mean CFB in MG-ADL score at Week 12 was compared to the non-inferiority margin of 2, representing the clinically meaningful 2-point increase (worsening) in MG-ADL score at Week 12. 16 Non-inferiority is declared if the upper limit of the one-sided 97.5% CI (or the two-sided 95% CI) of the LS mean CFB in MG-ADL score at Week 12 does not cross the non-inferiority margin of 2. All other efficacy endpoints were analysed descriptively. Statistical analyses and generation of data outputs were performed using SAS® version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Post hoc analyses of CFB in MG-ADL, QMG and MG-QoL 15r were assessed by the equivalent MMRM overall and by prior IV complement C5 inhibitor, producing nominal p-values.

Results

Patients and baseline demographics

In total, 26 patients were included in the mITT population and the same 26 were also included in the safety set (Figure 2). Of these, 23 patients completed the 12-week main treatment period. One patient increased their concomitant dose of prednisone from 10 to 20 mg during the main treatment period. Three patients discontinued, two due to TEAEs and one due to the patient’s lack of compliance with study procedures. All three patients who discontinued completed the 40-day safety follow-up.

Figure 2.

Patient disposition.

*All three patients who discontinued completed the 40-day safety follow-up.

mITT, modified intention-to-treat.

Several reasons were cited for why patients wanted to switch from their current complement C5 inhibitor (Table 1). The most common reasons for wanting to switch were related to issues inherent to IV infusions, including logistical challenges (seven eculizumab, one ravulizumab), lengthy infusions (three eculizumab) and other physical challenges such as feeling sick after infusions (one eculizumab) or wanting easier administration (one ravulizumab). Five patients wanted to switch due to perceived lack of efficacy or to improve their symptoms, of whom four were switching from ravulizumab and one was switching from eculizumab.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and reasons for switching from an IV complement C5 inhibitor.

| Characteristic | Zilucoplan 0.3 mg/kg N = 26 |

|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 59.9 (15.9) | |

| Female, n (%) | 13 (50.0) | |

| MG-ADL score, mean (SD) | 4.5 (4.1) | |

| QMG score, mean (SD) | 10.1 (5.0) | |

| Age at gMG onset, years, mean (SD) | 51.7 (18.6) | |

| Duration of disease from MG diagnosis, years, mean (SD) | 8.4 (7.7) | |

| Symptoms at onset, n (%) | ||

| Ocular | 10 (38.5) | |

| Baseline gMG therapy, n (%) | ||

| Cholinesterase inhibitors | 19 (73.1) | |

| Corticosteroids | 12 (46.2) | |

| Azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil | 13 (50.0) | |

| gMG treatment before switching to zilucoplan, n (%) | ||

| Eculizumab | 16 (61.5) | |

| Ravulizumab | 10 (38.5) | |

| Reason for switching to zilucoplan, n (%) | Eculizumab n = 16 |

Ravulizumab n = 10 |

| Logistical challenges, including travel and time spent at a hospital | 7 (43.8) | 1 (10.0) |

| Challenges with venous access | 2 (12.5) | 2 (20.0) |

| Lengthy intravenous infusion | 3 (18.8) | 0 |

| Other a | 4 (25.0) | 7 (70.0) |

| ‘Wearing off’ | ‘Patient perceived lack of efficacy’ | |

| ‘Patient gets sick after infusions’ | ‘Wearing off, less effective’ | |

| ‘Loss of hair’ | ‘Experiencing symptoms about 1.5 weeks prior to next infusion’ | |

| ‘Would like to participate in a research study to help science’ | ‘Patient would like to try a new treatment to see if this would improve their symptoms’ | |

| ‘Would like to try an alternative treatment’ | ||

| ‘Recommended by doctor, hates poking’ | ||

| ‘Easier administration’ | ||

‘Other’ was an option for investigators to write free text. Answers here are written verbatim.

C5, component 5; gMG, generalised myasthenia gravis; IV, intravenous; MG-ADL, Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living; QMG, Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis; SD, standard deviation.

Safety

Overall, switching from IV complement C5 inhibitors to SC zilucoplan was well tolerated (Table 2). TEAEs (six events in total) led to discontinuation in two patients. One of these patients discontinued due to injection-site pain, injection-site discoloration, pain, anxiety and fatigue. The TEAEs of injection-site pain and discoloration were deemed treatment-related by the investigator. The other patient discontinued due to reactivation of the Epstein–Barr virus, which was not considered treatment-related.

Table 2.

Overview of treatment-emergent adverse events.

| TEAE type | Zilucoplan 0.3 mg/kg N = 26 |

|---|---|

| Any TEAE | 19 (73.1) |

| Most common TEAEs (occurring in >1 patient) | |

| Amylase increased | 3 (11.5) |

| Diarrhoea | 2 (7.7) |

| Injection-site pain | 2 (7.7) |

| Lipase increased | 2 (7.7) |

| Nausea | 2 (7.7) |

| Pain | 2 (7.7) |

| Sinusitis | 2 (7.7) |

| Serious TEAE | 1 (3.8) |

| TEAE leading to discontinuation of zilucoplan | 2 (7.7) |

| Treatment-related TEAEs | 6 (23.1) |

| Severe TEAEs | 3 (11.5) |

Includes TEAEs reported during the 12-week main treatment period. Data are presented as n (%).

TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

The vast majority of TEAEs were mild in intensity, and there were four TEAEs in three patients rated as being severe in intensity by the investigator. One patient had a severe TEAE of pain and injection-site pain. The event of injection-site pain was deemed to be treatment-related by the investigator and zilucoplan was withdrawn, as noted above. Both events were resolved within 1–2 days with no further action taken. A second patient had a severe TEAE of nausea that was considered not related to treatment by the investigator. The third patient had an increase in serum lipase levels, which was considered treatment-related by the investigator. The lipase increase was transient and resolved within 18 days, with no action taken and no discontinuation of zilucoplan. Two serious TEAEs occurred in one patient, diverticulitis and pyelonephritis, which were mild in intensity and not related to zilucoplan. There were no deaths and no cases of meningococcal infection.

Efficacy

Overall, LS mean MG-ADL score had improved compared with baseline after 12 weeks of zilucoplan treatment (CFB −1.15; 95% CI: −2.11, −0.19; the upper limit of the 95% CI does not cross the predefined non-inferiority margin of 2). This improvement in the MG-ADL score was also significant with nominal p-value = 0.0217, post hoc analysis (Figure 3(a)). In a post hoc analysis, clinically meaningful and nominally statistically significant improvements from baseline at Week 12 in mean MG-ADL score were observed in patients who switched from ravulizumab (Figure 3(b)). Overall, LS mean QMG score did not improve significantly from baseline (Figure 3(c)); however, post hoc analysis for the subgroup of patients who switched from ravulizumab showed clinically meaningful and nominally statistically significant improvements from baseline at Week 12 (Figure 3(d)).

Figure 3.

CFB in (a, b) MG-ADL score to Week 12 for the total population and by prior IV complement C5 inhibitor subgroup, and (c, d) QMG score to Week 12 for the total population and by prior IV complement C5 inhibitor.

*p-Values are nominal.

C5, component 5; CFB, change from baseline; CI, confidence interval; IV, intravenous; LS, least squares; MG-ADL, Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living; QMG, Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis.

In a responder analysis, MG symptoms in approximately 75% of patients remained stable or improved according to MG-ADL and QMG scores at Week 12 (Figure 4(a) and (b)). Similar proportions of patients had stable or improved MG-ADL scores at Week 12 regardless of whether switching from eculizumab or ravulizumab (Figure 4(c) and (e)). Overall, improvements in QMG scores were driven, in particular, by patients switching from ravulizumab, of whom 89% had stable or improved QMG scores after 12 weeks of zilucoplan (Figure 4(f)) versus 65% of patients switching from eculizumab (Figure 4(d)). At Week 12, mean (SD) CFB in MG-QoL 15r score was −2.67 (5.66) in the total population (Table 3). Mean (SD) CFB in MG-QoL 15r score at Week 12 for patients who switched from ravulizumab was −5.33 (6.16) and −1.07 (4.86) among those who switched from eculizumab. No patients received rescue therapy during the 12-week main treatment period.

Figure 4.

Minimum point change from baseline in MG-ADL and QMG scores at Week 12 for (a, b) the total population, (c, d) patients receiving prior eculizumab and (e, f) patients receiving prior ravulizumab (responder analysis).

Pie chart percentages represent the proportion of patients who saw no change (× = 0) or who improved by ⩾1 point (× = −1).

MG-ADL, Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living; QMG, Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis.

Table 3.

MG-QoL 15r and TSQM-9 scores.

| PRO | Total population n = 26 |

Eculizumab n = 16 |

Ravulizumabn = 10 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline score | CFB at Week 12 | Baseline score | CFB at Week 12 | Baseline score | CFB at Week 12 | |

| MG-QoL 15r | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 11.8 (7.8) | −2.67 (5.66) | 10.2 (7.9) | −1.07 (4.86) | 14.5 (7.3) | −5.33 (6.16) |

| n | 26 | 24 | 16 | 15 | 10 | 9 |

| TSQM-9 | ||||||

| Global satisfaction | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | +59.472 (21.740) | +19.410 (27.429) | +61.264 (24.391) | +16.209 (31.563) | +57.143 (18.748) | +23.571 (21.835) |

| n | 23 | 23 | 13 | 13 | 10 | 10 |

| Effectiveness | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | +60.606 (21.476) | +13.889 (21.534) | +65.741 (23.550) | +7.870 (25.674) | +54.444 (17.916) | +21.111 (13.042) |

| n | 22 | 22 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 10 |

| Convenience | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | +58.454 (18.793) | +21.739 (19.955) | +58.547 (20.237) | +25.641 (23.198) | +58.333 (17.811) | +16.667 (14.344) |

| n | 23 | 23 | 13 | 13 | 10 | 10 |

CFB, change from baseline; MG-QoL 15r, Myasthenia Gravis Quality of Life revised 15-item; PRO, patient-reported outcome; SD, standard deviation; TSQM-9, 9-item Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire of Medication.

Higher treatment satisfaction was observed across all the three domain scores of the TSQM-9 at Week 12 compared with baseline (Table 3). Among the total population, mean (SD) CFB at Week 12 Global Satisfaction, Effectiveness and Convenience domain scores were +19.410 (27.429), +13.889 (21.534) and +21.739 (19.955), respectively. Among patients who switched from ravulizumab, mean (SD) CFB in domain scores at Week 12 were +23.571 (21.835), +21.111 (13.042) and +16.667 (14.344), respectively. Among patients who switched from eculizumab, mean (SD) CFB in domain scores at Week 12 were +16.209 (31.563), +7.870 (25.674) and +25.641 (23.198), respectively.

At Week 12, 76.9% (n = 20) of patients preferred SC injection compared with IV infusion. Four patients (15.4%) preferred IV infusion (all four switched from eculizumab) and two (7.7%) patients had no preference (one switched from eculizumab, one from ravulizumab). Patients (n = 23) took less than 30 s (28.5 s at Week 2 and 27.4 s at Week 12) to self-administer one dose of zilucoplan.

Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics

Overall, complement inhibition increased from baseline and was complete (>95% 24 ) at the first assessment (Week 2) after switching to zilucoplan (Figure 5). Complete complement inhibition was maintained at Week 12, which is consistent with previous studies of zilucoplan.5,11 In the subgroup of patients switching from ravulizumab, complement inhibition was incomplete at baseline (87.3%), but increased to 99.0% at Week 2 and 98.9% at Week 12. Among patients who switched from eculizumab, complement inhibition generally remained stable from baseline to Week 12 (97.4%–99.0%).

Figure 5.

Mean complement inhibition at baseline, Week 2 and Week 12, for the total population and by prior IV complement C5 inhibitor subgroup.

*Post hoc analysis. Complement activity was measured using the sheep red blood cell assay. One patient who withdrew early is not included in the Week 12 measurement as their blood sample was taken 16 days after the last zilucoplan dose.

C5, component 5; IV, intravenous; Wk, Week.

Plasma concentrations of zilucoplan were consistent with the known pharmacokinetics of zilucoplan. Whilst on treatment, the geometric mean zilucoplan plasma concentrations were similar at Week 2 (13,825.2 ng/mL) and Week 12 (12,709.7 ng/mL).

Discussion

This study reports the 12-week main treatment period of MG0017, a study to evaluate the safety, tolerability, efficacy, treatment satisfaction and patient preference of SC self-administered zilucoplan in participants with gMG, who wanted to switch from their current IV HCP-administered complement C5 inhibitor. These findings will be relevant to neurologists helping patients who would like to switch from an IV to an SC complement C5 inhibitor. Switching to SC zilucoplan from IV eculizumab or ravulizumab at the end of the IV treatment interval was feasible and well tolerated. Overall, there were no safety concerns, and these safety data build on the favourable safety profile for zilucoplan observed in the randomised, placebo-controlled, pivotal phase III RAISE study 5 and its open-label extension, RAISE-XT. 11

MG-ADL and QMG scores decreased after switching to zilucoplan, and symptoms remained stable or improved in approximately 75% of patients at Week 12, providing reassurance to patients and physicians that there is a high chance for efficacy to be maintained or improved if they choose to switch to zilucoplan. In particular, clinically meaningful and nominally statistically significant improvements from baseline in MG-ADL and QMG scores were observed in patients switching from ravulizumab. Given that there was no washout period between the end of the IV treatment interval and initiation of zilucoplan, these are noteworthy. Further, changes in concomitant standard of care medication could not have contributed to the observed differences in efficacy, as only one patient changed their standard of care dose during the main treatment period.

Complement inhibition also increased from baseline after switching from ravulizumab. All patients entering the study received their first dose of zilucoplan on the day they were due to receive their next dose of IV complement C5 inhibitor had they been continuing with that treatment. Thus, for patients switching from ravulizumab, there was an 8-week interval between the last dose of ravulizumab and the first dose of zilucoplan, while for patients switching from eculizumab, the respective time interval was 2 weeks. The longer, 8-week interval might explain the lower mean levels of complement inhibition at baseline for patients who were previously treated with ravulizumab. It is possible that complement inhibition decreased over the 8-week interval in the subset of ravulizumab-treated patients, which is reflective of the perception of waning efficacy that 3 out of 10 patients had cited as their reason for wanting to switch from ravulizumab. A daily treatment regimen can prevent the peaks and troughs in efficacy that may be associated with less-frequent infusions, as supported by consistently high complement inhibition observed in over 60 weeks of zilucoplan treatment in RAISE-XT. 11 In addition, data from RAISE and RAISE-XT have shown that in the event of IVIg or PLEX being needed as rescue therapy, complete complement inhibition is maintained during zilucoplan treatment, without the need for supplemental dosing.3,25 However, if IVIg or PLEX is required while receiving eculizumab or ravulizumab, a supplemental dose is required to maintain drug serum levels.7,8,14,15

Further, meaningfully higher treatment satisfaction and patient preference were observed for zilucoplan versus IV complement C5 inhibitors. Overall, mean CFB scores for Global Satisfaction, Effectiveness and Convenience exceeded the recommended meaningful change thresholds (described in the Supplemental Material). 21 In the Effectiveness domain of the TSQM-9, patients who switched from ravulizumab reported a greater increase compared with those who switched from eculizumab, partially carried by a lower Effectiveness baseline value. Conversely, in the Convenience domain, patients previously receiving eculizumab reported a greater increase compared with those on prior ravulizumab, which presumably reflects the more frequent infusion schedule of eculizumab compared with ravulizumab.

The most common reasons for wanting to switch were related to IV infusion, including logistical and physical challenges. These data support the literature suggesting that some patients with chronic diseases prefer SC administration. 12 In addition, daily self-administration reduces the logistical burden for patients, particularly as zilucoplan can be stored at room temperature for up to 3 months.24,26 Considering the chronic and unpredictable nature of gMG, reducing treatment burden such as repeated travel to clinics for treatment is important to consider for patients’ health-related quality of life. 13 In our study, 40% of patients switching from ravulizumab cited wearing off or lack of efficacy as the primary reason for wanting to switch. This is in line with findings from clinical practice in which 35% of patients undergoing treatment with ravulizumab reported waning efficacy before their next infusion. 27

This study has some limitations. First, it has a relatively low sample size and a short treatment period that may not be long enough to fully evaluate the preference for a daily regimen of zilucoplan compared with an every 2- or 8-week regimen (i.e. the potential ‘treatment fatigue’ of daily injections). However, long-term compliance for zilucoplan in RAISE-XT was high, with 95% of patients reported as having taken >95% of their medication over a median exposure period of 2.2 years. 28 In addition, this study included only patients who were interested in switching from their current IV complement C5 inhibitor, which would have contributed to higher treatment satisfaction and patient preference after a switch from IV to SC treatment than if the study was blinded, or if the patients were not actively looking for a different treatment. However, specifically targeting these patients was an important aspect of the study design. Patient preference in this study was assessed through a single question, rather than using robust patient preference methodology such as a discrete choice experiment. However, the reported preferences are in line with the results of the other efficacy assessments and TSQM-9 results, which provide further support for the conclusion that, overall, the current sample preferred zilucoplan treatment.

Conclusion

These data provide information that may be valuable for physicians and patients who are considering a switch from an IV to a SC complement C5 inhibitor for the treatment of gMG. An ongoing extension treatment period will provide continued pharmacovigilance surveillance and real-world data on zilucoplan.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tan-10.1177_17562864251347283 for Switching to subcutaneous zilucoplan from intravenous complement component 5 inhibitors in generalised myasthenia gravis: a phase IIIb, open-label study by Miriam Freimer, Urvi Desai, Raghav Govindarajan, Min K. Kang, Shaida Khan, Bhupendra Khatri, Todd Levine, Samir Macwan, Perry B. Shieh, Michael D. Weiss, Jos Bloemers, Babak Boroojerdi, Eumorphia Maria Delicha, Andreea Lavrov, Puneet Singh and James F. Howard in Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-tan-10.1177_17562864251347283 for Switching to subcutaneous zilucoplan from intravenous complement component 5 inhibitors in generalised myasthenia gravis: a phase IIIb, open-label study by Miriam Freimer, Urvi Desai, Raghav Govindarajan, Min K. Kang, Shaida Khan, Bhupendra Khatri, Todd Levine, Samir Macwan, Perry B. Shieh, Michael D. Weiss, Jos Bloemers, Babak Boroojerdi, Eumorphia Maria Delicha, Andreea Lavrov, Puneet Singh and James F. Howard in Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and their caregivers, in addition to the investigators and their teams, who contributed to this study. The authors thank Veronica Porkess, PhD, CMPP, for publication and editorial support, Brittany Harvey for study management and coordination and Dr Natasa Savic, all of UCB, for critical review. This manuscript was submitted by Ogilvy Health, London, UK, funded by UCB, on behalf of the authors.

Footnotes

ORCID iD: James F. Howard  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7136-8617

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7136-8617

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Miriam Freimer, Department of Neurology, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, 395 West 12th Avenue, 7th Floor, Columbus, OH 43210, USA.

Urvi Desai, Atrium Health, Wake Forest University, Charlotte, NC, USA.

Raghav Govindarajan, HSHS St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, O’Fallon, IL, USA.

Min K. Kang, Department of Neurology, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA

Shaida Khan, Department of Neurology, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA.

Bhupendra Khatri, The Regional MS Center and Center for Neurological Disorders, Milwaukee, WI, USA.

Todd Levine, HonorHealth Neurology, Bob Bové Neuroscience Institute, Scottsdale, AZ, USA.

Samir Macwan, Department of Neurology, Eisenhower Health, Rancho Mirage, CA, USA.

Perry B. Shieh, Department of Neurology and Pediatrics, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Michael D. Weiss, Department of Neurology, University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, WA, USA

Jos Bloemers, UCB, Brussels, Belgium.

Babak Boroojerdi, UCB, Monheim, Germany.

Eumorphia Maria Delicha, UCB, Braine-l’Alleud, Belgium.

Andreea Lavrov, UCB, Monheim, Germany.

Puneet Singh, UCB, Slough, UK.

James F. Howard, Jr, Department of Neurology, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: This study was conducted in accordance with ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki and that are consistent with Good Clinical Practice. The study protocol, amendments and patients’ informed consent were reviewed by a national, regional or independent ethics committee or institutional review board for each participating site. The approving ethics committees or institutional review boards are listed in the Supplemental Material. All patients provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Author contributions: Miriam Freimer: Investigation; Writing – review & editing.

Urvi Desai: Investigation; Writing – review & editing.

Raghav Govindarajan: Investigation; Writing – review & editing.

Min K. Kang: Investigation; Writing – review & editing.

Shaida Khan: Investigation; Writing – review & editing.

Bhupendra Khatri: Investigation; Writing – review & editing.

Todd Levine: Investigation; Writing – review & editing.

Samir Macwan: Investigation; Writing – review & editing.

Perry B. Shieh: Investigation; Writing – review & editing.

Michael D. Weiss: Investigation; Writing – review & editing.

Jos Bloemers: Conceptualisation; Methodology; Writing – review & editing.

Babak Boroojerdi: Conceptualisation; Methodology; Writing – review & editing.

Eumorphia Maria Delicha: Conceptualisation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing – review & editing.

Andreea Lavrov: Conceptualisation; Methodology; Writing – review & editing.

Puneet Singh: Conceptualisation; Methodology; Writing – review & editing.

James F. Howard Jr: Investigation; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by UCB. Medical writing support was provided by Julia Stevens, PhD, and Rachel Price, PhD, CMPP, of Ogilvy Health, London, UK, and funded by UCB, in accordance with Good Publications Practice (GPP) guidelines (https://www.ismpp.org/gpp-2022). Authors were not paid to participate in the manuscript writing or review.

Competing interests: M.F. has served as a paid Consultant for Alexion Pharmaceuticals, argenx and UCB. She receives research support from Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Avidity Biosciences, Fulcrum Therapeutics, Janssen Pharmaceuticals (now Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicine), the NIH and UCB. U.D. has served on advisory boards for Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, argenx, Biogen, Catalyst, CSL Behring, Fulcrum Therapeutics, Sarepta, Takeda Pharmaceuticals and UCB. She has served on speaker bureaus for Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, argenx and CSL Behring. Her institution has received research support from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma. R.G. has served on advisory boards for argenx, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Roche and UCB, and participated in speaker bureaus for Alexion Pharmaceuticals, argenx and UCB. M.K.K. receives research support from UCSF and has served on advisory boards for Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson and UCB. She has received honoraria from AcademicCME. S.K. has served as a paid Consultant for UCB and has served on advisory boards for argenx and UCB. She receives research support from the Fichtenbaum Charitable Trust. B.K. has received research and/or consulting financial compensation from Alexion Pharmaceuticals, argenx, Biogen, Bristol Myers Squibb, EMD Serono, Genentech, Novartis, Sanofi Genzyme (now Sanofi), Terumo BCT, TG Therapeutics and UCB. T.L. has nothing to disclose. S.M. has received personal compensation for serving as a Consultant for Alexion Pharmaceuticals, argenx, KabaFusion and UCB. He has received personal compensation for serving on a speakers’ bureau for AbbVie, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, argenx and Grifols. The institution of Dr S.M. has received research support from Alexion Pharmaceuticals and Dysimmune Diseases Foundation. P.B.S. has nothing to disclose. M.D.W. has received honoraria for serving on scientific advisory boards for Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Amylyx Pharmaceuticals, argenx, Biogen, Immunovant, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma and Ra Pharmaceuticals (now UCB), consulting honoraria from Cytokinetics and CSL Behring, and speaker honoraria from Soleo Health. He also serves as a special government employee for the Food and Drug Administration. J.B., B.B., A.L. and P.S. are employees and shareholders of UCB. P.S. is a previous employee and shareholder of GSK. E.M.D. is an employee of UCB. J.F.H. Jr has received research support (paid to his institution) from Ad Scientiam, Alexion/AstraZeneca Rare Disease, argenx, Cartesian Therapeutics, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA, USA), the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America, the Muscular Dystrophy Association, the National Institutes of Health (including the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases), NMD Pharma, PCORI and UCB; has received honoraria/consulting fees from AcademicCME, Alexion/AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Amgen, argenx, Biohaven Ltd, Biologix Pharma, CheckRare CME, Curie.Bio, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Medscape CME, Merck EMD Serono, Novartis, PeerView CME, Physicians’ Education Resource (PER) CME, PlatformQ CME, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi US, TG Therapeutics, UCB and Zai Labs; and has received non-financial support from Alexion/AstraZeneca Rare Disease, argenx, Biohaven Ltd, Toleranzia AB and UCB.

Availability of data and materials: Underlying data from this manuscript may be requested by qualified researchers 6 months after product approval in the USA and/or Europe or global development is discontinued, and 18 months after trial completion. Investigators may request access to anonymised individual patient-level data and redacted trial documents, which may include analysis-ready datasets, the study protocol, annotated case report forms, statistical analysis plans, dataset specifications and the clinical study report. Prior to use of the data, proposals need to be approved by an independent review panel at www.Vivli.org and a signed data-sharing agreement will need to be executed. All documents are available in English only, for a pre-specified time, typically 12 months, on a password-protected portal.

References

- 1. Gilhus NE, Verschuuren JJ. Myasthenia gravis: subgroup classification and therapeutic strategies. Lancet Neurol 2015; 14: 1023–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gilhus NE, Tzartos S, Evoli A, et al. Myasthenia gravis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019; 5: 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Howard JF, Jr, Vissing J, Gilhus NE, et al. Zilucoplan: an investigational complement C5 inhibitor for the treatment of acetylcholine receptor autoantibody-positive generalized myasthenia gravis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2021; 30: 483–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Howard JF, Jr, Utsugisawa K, Benatar M, et al. Safety and efficacy of eculizumab in anti-acetylcholine receptor antibody-positive refractory generalised myasthenia gravis (REGAIN): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre study. Lancet Neurol 2017; 16: 976–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Howard JF, Jr, Bresch S, Genge A, et al. Safety and efficacy of zilucoplan in patients with generalised myasthenia gravis (RAISE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Neurol 2023; 22: 395–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vu T, Meisel A, Mantegazza R, et al. Terminal complement inhibitor ravulizumab in generalized myasthenia gravis. NEJM Evid 2022; 1: EVIDoa2100066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc. SOLIRIS (eculizumab) injection, US PI, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/125166s447lbl.pdf (2024, accessed June 2025).

- 8. Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc. ULTOMIRIS (ravulizumab-cwvz) injection, US PI, https://alexion.com/documents/ultomiris_uspi (2024, accessed June 2025).

- 9. Tang G-Q, Tang Y, Dhamnaskar K, et al. Zilucoplan, a macrocyclic peptide inhibitor of human complement component 5, uses a dual mode of action to prevent terminal complement pathway activation. Front Immunol 2023; 14: 1213920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Howard JF, Jr, Nowak RJ, Wolfe GI, et al. Clinical effects of the self-administered subcutaneous complement inhibitor zilucoplan in patients with moderate to severe generalized myasthenia gravis: results of a phase 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter clinical trial. JAMA Neurol 2020; 77: 582–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Howard JF, Jr, Bresch S, Farmakidis C, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of zilucoplan in patients with generalized myasthenia gravis: interim analysis of the RAISE-XT open-label extension study. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2024; 17: 17562864241243186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Overton PM, Shalet N, Somers F, et al. Patient preferences for subcutaneous versus intravenous administration of treatment for chronic immune system disorders: a systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence 2021; 15: 811–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bril V, Lampe J, Cooper N, et al. Patient-reported preferences for subcutaneous or intravenous administration of parenteral drug treatments in adults with immune disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Comp Eff Res 2024; 13: e230171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alexion Europe SAS. ULTOMIRIS (ravulizumab-cwvx) injection, EU SmPC, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/ultomiris-epar-product-information_en.pdf (2025, accessed June 2025).

- 15. Alexion Europe SAS. SOLIRIS (eculizumab) injection, EU SmPC, https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/362/smpc (2025, accessed June 2025).

- 16. Muppidi S, Wolfe GI, Conaway M, et al. MG-ADL: still a relevant outcome measure. Muscle Nerve 2011; 44: 727–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wolfe GI, Herbelin L, Nations SP, et al. Myasthenia gravis activities of daily living profile. Neurology 1999; 52: 1487–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Katzberg HD, Barnett C, Merkies IS, et al. Minimal clinically important difference in myasthenia gravis: outcomes from a randomized trial. Muscle Nerve 2014; 49: 661–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barohn RJ, McIntire D, Herbelin L, et al. Reliability testing of the quantitative myasthenia gravis score. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1998; 841: 769–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Burns TM, Sadjadi R, Utsugisawa K, et al. International clinimetric evaluation of the MG-QOL15, resulting in slight revision and subsequent validation of the MG-QOL15r. Muscle Nerve 2016; 54: 1015–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Greene N, Quéré S, Bury DP, et al. Establishing clinically meaningful within-individual improvement thresholds for eight patient-reported outcome measures in people with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2023; 7: 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bharmal M, Payne K, Atkinson MJ, et al. Validation of an abbreviated Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM-9) among patients on antihypertensive medications. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009; 7: 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Regnault A, Balp MM, Kulich K, et al. Validation of the treatment satisfaction questionnaire for medication in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2012; 11: 494–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. UCB Pharma S.A. ZILBRYSQ (zilucoplan) injection, EU SmPC, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/zilbrysq-epar-product-information_en.pdf (2024, accessed June 2025).

- 25. Weiss MD, Hewamadduma C, Leite IM, et al. Concomitant intravenous immunoglobulin or plasma exchange has no effect on complement inhibition by zilucoplan [abstract]. Paper presented at the AANEM, Savannah, GA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 26. UCB, Inc. ZILBRYSQ (zilucoplan) injection, US PI, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/216834s001lbl.pdf (2024, accessed June 2025).

- 27. Ho D, Clifford K, Blum S, et al. Treatment fluctuations in patients with acetylcholine receptor antibody positive generalized myasthenia gravis on maintenance ravulizumab treatment (P10-11.001). Neurology 2024; 102: 3639. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ruzhansky K, Freimer M, Leite IM, et al. Compliance to daily self-administered subcutaneous zilucoplan in patients with generalized myasthenia gravis: a post hoc analysis of the RAISE-XT study [abstract]. Paper presented at the AANEM, Savannah, GA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tan-10.1177_17562864251347283 for Switching to subcutaneous zilucoplan from intravenous complement component 5 inhibitors in generalised myasthenia gravis: a phase IIIb, open-label study by Miriam Freimer, Urvi Desai, Raghav Govindarajan, Min K. Kang, Shaida Khan, Bhupendra Khatri, Todd Levine, Samir Macwan, Perry B. Shieh, Michael D. Weiss, Jos Bloemers, Babak Boroojerdi, Eumorphia Maria Delicha, Andreea Lavrov, Puneet Singh and James F. Howard in Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-tan-10.1177_17562864251347283 for Switching to subcutaneous zilucoplan from intravenous complement component 5 inhibitors in generalised myasthenia gravis: a phase IIIb, open-label study by Miriam Freimer, Urvi Desai, Raghav Govindarajan, Min K. Kang, Shaida Khan, Bhupendra Khatri, Todd Levine, Samir Macwan, Perry B. Shieh, Michael D. Weiss, Jos Bloemers, Babak Boroojerdi, Eumorphia Maria Delicha, Andreea Lavrov, Puneet Singh and James F. Howard in Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders