Abstract

Background

Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors have emerged as a promising class of therapeutics, particularly in the treatment of cancers with defective DNA repair mechanisms, such as those with breast cancer genes (BRCA) mutations. Their effectiveness in cancer therapy is now well-established, but the ongoing advancements in radiochemistry are expanding their potential to combine both therapeutic and imaging capabilities. Radiolabelled PARP inhibitors, used in conjunction with positron emission tomography (PET) or single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), might enable precise imaging of PARP expression in tumours, potentially providing invaluable insights into treatment response, tumor heterogeneity, and molecular profiling.

Main body

The radiochemistry of PARP inhibitors involves incorporating radioisotopes (most of all Fluorine-18) into the molecular structure of these molecules. The first strategy used to achieve this goal was the use of prosthetic groups bearing the fluorine-18. Then, the development of radioisotopologue have gained ground, followed later by the replacement with other halogens such as bromine, iodine, or astatine has taken place. Another frontier is represented by the metal radiolabelling of these inhibitors through the introduction of a chelator moiety to these molecules, thus further expanding both imaging and therapy applications.

Conclusion

Finally, emerging evidence suggest the possibility to involve PARP-related radiopharmaceuticals in theranostics approaches. Despite challenges such as the complexity of radiolabelling, regulatory hurdles, and the need for more robust clinical validation, the continued exploration of the radiochemistry of PARP inhibitors promises to revolutionize both the diagnosis and treatment of cancer, offering hope for more effective and personalized cancer care.

Keywords: PARP, PARP1, PARP inhibitor, Radiolabelling, PARP imaging, PARP therapy, Rucaparib, Olaparib, Niraparib, Talazoparib

Background

Genomic instability is a hallmark of cancer, and often is the result of altered DNA repair capacities in tumour cells (Mateo et al. 2019). DNA is the essential instruction manual for every cell in our body, guiding how cells grow, divide, and function. However, DNA is constantly exposed to damage from various sources, both internal and external (Farmer et al. 2005). Internal factors, such as natural cell growth and division, along with external factors like UV radiation, pollution, and toxins contribute to DNA damage (Pascal 2018). This damage can manifest as breaks in the DNA strands, which may be small single-strand breaks (SSBs) or more severe double-strand breaks (DSBs) (Hassa et al. 2006; Alhmoud et al. 2020). If left unrepaired or improperly repaired, DNA damage can lead to serious diseases, including cancer (D’Andrea 2018; Pommier et al. 2016). To counteract this, cells have complex repair mechanisms that help restore the breaks and maintain the integrity of the DNA molecule (Kubalanza and Konecny 2020). At least 450 proteins are thought to be involved in repairing pathways. Among these, the enzyme family called poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase or PARP for short (Lord and Ashworth 2012) plays a crucial role. Of this family, PARP1 is the most studied and abundant enzyme. PARP1 is crucial in DNA repair, especially in repairing single-strand breaks. When a strand break occurs in the DNA, PARP is one of the first proteins to recognize the damage (Ferraris 2010; Curtin and Szabo 2013). It attaches to the damaged site and adds special molecules called poly(ADP-ribose) chains to itself and nearby proteins, initiating the repair process (Murai et al. 2012). These chains act as signals, guiding other repair proteins to the damage site to help fix the break (Min and Im 2020). PARP does more than just fix breaks; it also helps regulate the structure of DNA, controls gene expression, and can influence whether a cell survives or undergoes cell death, depending on the extent of the damage (Jelinic and Levine 2014). This makes PARP1 a central figure in maintaining cellular health and genomic stability. Cancer cells, due to their rapid growth and division, experience much higher levels of DNA damage compared to normal cells. Many cancer cells, particularly those with mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes, lack an important DNA repair pathway known as homologous recombination repair (HRR) (Lord and Ashworth 2017). BRCA1 and BRCA2 roles in processes such as chromatin remodelling and transcriptional regulation might also be relevant to pathogenesis (Dhillon et al. 2016). Without the beforehand cited repair system, these cancer cells become highly dependent on PARP to fix their DNA damage. This reliance creates a vulnerability that can be exploited by PARP inhibitors which target tumour cells with HRR gene mutations therapies through a mechanism known as synthetic lethality. PARP inhibitors bind to and inhibit PARP, preventing PARylation and trapping inactivated PARP on DNA. This blocks replication forks, causing their collapse and double-strand breaks. In cells with defective HRR proteins (e.g., BRCA1, BRCA2), the breaks are repaired by the error-prone non-homologous end-joining pathway, leading to tumour cell death (Cortesi et al. 2021). Healthy cells, which can rely on other DNA repair systems, are less affected by the inhibition of PARP, offering benefits not seen with conventional chemotherapy (Mateo et al. 2019).

To date, five PARP inhibitors have been approved by FDA (Food and Drug Administration) for clinical use in treating cancers or as second line of treatment for recurrent malignancies. Currently, Olaparib, Rucaparib, Niraparib, Talazoparib, and Veliparib are used in the treatment of ovarian, breast, prostate, and pancreatic cancers, showing impressive results in patients with tumours that carry BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations (Das et al. 2024). On the other hand, Fluzoparib (Fuzuloparib 2021) and Pamiparib (Pamiparib 2021) have been approved in China for the treatment of germline BRCA mutation-associated recurrent advanced ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal cancer previously treated with two or more lines of chemotherapy. The cited PARP inhibitors are reported in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Molecular structures of approved PARP inhibitors

Due to the above mentioned functions, the use of PARP inhibitors is being explored in combination with other therapies, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immunotherapy, to enhance their effectiveness and broaden the range of patients (Jannetti et al. 2018; Pirovano et al. 2020). Beyond their use in therapy, radiolabelled PARP inhibitors may allow direct tracking of PARP expression in patients, improving patient’s stratification and monitoring of treatment response to PARPI therapy, thus opening up to further applications (Puentes et al. 2021). By attaching a radionuclide to the PARP inhibitors scaffold, clinicians can visualize the presence of PARP in tumours using imaging techniques like PET or SPECT. Radiolabelled probes for PET/SPECT and therapeutic applications must meet specific criteria to ensure they adhere to required standards and support reliable applications. The synthesis of the radioactive compound should be cost-effective, reproducible, and scalable, enabling large-scale production for clinical use. Additionally, the synthetic protocol should align with the half-life (t1/2) of the selected radionuclide and ensure the safety of the final product, thus facilitating its application. Moreover, every radionuclide comes along with its unique chemistry and related challenges, through time the radiochemist community has developed new methodologies to install them precisely and effectively. This review focuses on the chemical and synthetic aspects of PARP inhibitors that have been labelled with the radioisotopes reports in Table 1. Specifically, it highlights how synthetic strategies for developing new PARP-based compounds have changed over the years and investigates how procedures have been ameliorated to address the challenges.

Table 1.

Radioisotopes list, List of radioisotopes utilized to label PARP inhibitors

| Radioisotopes list | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Radionuclide, Half-life, Emission and type Applications | |||

| Flourine-18 (.18F) | 109.77 min | Positron emission (β⁺, max 633 keV, avg ~ 250 keV) | PET Imaging |

| Iodine-123 (.123I) | 13.2 h | γ emission (159 keV) | SPECT Imaging |

| Iodine-124 (.124I) | 4.18 days | Positron (β⁺, max 2.13 MeV) and γ emission (602–1691 keV) | PET Imaging |

| Iodine-125 (.125I) | 59.4 days | Low-energy γ emission (35 keV) | Imaging and Therapy |

| Iodine-131(.131I) | 8.02 days | β emission (β⁻, max 606 keV) and γ emission (364 keV) | Imaging and Therapy |

| Bromine-80m (.80mBr) | 4.4 h | γ emission (617 keV) and Auger electron (0.18-2.7 keV) | Therapy |

| Bromine-76 (.76Br) | 16.2 h | Positron emission (β⁺, max 3.94 MeV) and γ emission (657 keV) | PET Imaging |

| Bromine-77 (.77Br) | 57.0 h | Auger electron (0.07-5.794 keV) and γ emission (239 keV) | Therapy |

| Astatine-211 (.211At) | 7.2 h | α emission (5.87 and 7.45 MeV) and X-rays (~ 77–92 keV) | Therapy |

| Carbon-11 (.11C) | 20.38 min | Positron emission (β⁺ max 960 keV, avg ~ 386 keV) | PET Imaging |

| Copper-64 (.64Cu) | 12.7 h | Positron emission (β⁺ 653 keV), (β⁻ 573 keV) and Auger electrons (0.06–7.97 keV) | Imaging and Therapy |

| Copper-67 (.67Cu) | 61.8 min | Positron emission (β⁻, max 577 keV) and γ emission (184.6 keV) | Imaging and Therapy |

| Gallium-68 (.68Ga) | 67.7 min | Positron emission (β⁺, max 1.9 MeV, avg ~ 830 keV) | PET Imaging |

| Technetium-99m (.99mTc) | 6.01 h | γ Emission (140 keV) | SPECT Imaging |

Main text

Fluorine (18F)

Fluorine-18 (18F) is the gold standard radioisotope for PET imaging, commonly used due to its advantageous nuclear and physical characteristics. It decays to 18O by positron emission (β + with 97% efficiency). It has relatively low positron energy (0.635 MeV), a half-life of 109.8 min, and a short positron linear range in tissue (maximum of 2.3 mm) (Alauddin 2011). The first radiolabelled PARP inhibitor with fluorine-18 was developed in 2011 by Weissleder and colleagues. The development began by modifying the Olaparib scaffold, which was selected as a benchmark. Specifically, the final cyclopropyl tail was substituted for a tetrazine moiety. The final radiotracer, [18F]BO, also known as [18F]AZD228, was synthesised via an inverse-electron Diels–Alder cycloaddition with an fluorine-18-labelled trans-cyclooctene ([18F]3), obtained via a nucleophilic substitution (SN2) from a tosylate precursor (2) (Keliher et al. 2011) as depicted in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Radiosynthesis of [18F]BO

[18F]BO was the first Olaparib-based radiotracer to image in vivo PARP1 expression in breast and ovarian cancer xenografts (Reiner et al. 2012, 2011). The same group later developed an acid-catalysed fluorine-18/fluorine-19 exchange method for several functionalized boron dipyrromethene (BODIPY) fluorophores. They exploited this novel methodology to radiolabel a BODIPY-modified PARP1 inhibitor (4) utilizing [18F]F-/TBAB mixture with Tf2O/tBuOH at 40 °C to obtain the [18F]PARPi-FL with an encouraging radiochemical yield (RCY) of 49% (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Radiosynthesis of [18F]PARPi-FL via acid catalysed fluorine-18/fluorine-19 exchange

However, as stated by the authors, the fluoride exchange is not the method of choice to pursue a high molar activity (Am) due to the impossible separation of the starting material from the labelled product (Keliher et al. 2014). In vivo studies confirmed the radiotracer's ability to track PARP1 expression in glioblastoma xenografts, however, they also highlight the rapid metabolic defluorination (Carlucci et al. 2015). In the same period, the Rucaparib scaffold was selected in the Mach laboratories to develop a fluorine-18-labelled probe. The first idea was to modify the core structure obtaining a radiotracer structurally close to the parent compound. The [18F]Fluorthanatrace ([18F]FTT) saw the replacement of the dimethylphenylmethanamine moiety with fluorine-18-fluoroethoxy benzene (Zhou et al. 2014). The [18F]FTT was radiosynthesised from a mesylated precursor (5) where the radionuclide is inserted through a nucleophilic substitution in the presence of [18F]KF and a phase transfer agent such as Kriptofix (K2.2.2) with a 40–50% RCYdc as reported in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Radiosynthesis of [18F]FTT

This tracer showed a specific tumour uptake in several breast cancer cell lines such as HCC1937, MDA-MB-231, and MCF-7 (Zhou et al. 2014; Edmonds et al. 2016). The first radiolabelled Olaparib and Rucaparib derivatives bore a relatively large footprint and [18F]PARPi-FL and [18F]BO were definitively bulkier when compared to Olaparib. These modifications bring crucial changes to the pharmacokinetic properties and cell penetration ability, which is essential to reach the intranuclear target. In 2015, Reiner and collaborators decided to follow the pathway of the scaffold modification, replacing the Olaparib cyclopropyl moiety with a fluorobenzene ring. This tailoring was smaller than before and led to the radiochemically stable [18F]PARPi, structurally more similar and closer in molecular weight to parent PARPi (Carney et al. 2016). Carney and coworkers radiosynthesised the tracer introducing a small fragment, functioning as a prosthetic group. They conjugated a 4-[18F]fluorobenzoic acid group (8), obtained from two previous steps, to 4-(4-fluoro-3-(piperazine-1-carbonyl)benzyl)phthalazin-1(2H)-one (6). The 4-[18F]fluorobenzoic acid, 8, derived from ethyl 4-nitrobenzoate, 6, via nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr) with dry [18F]KF/K2.2.2, producing the ethyl 4-[18F]fluorobenzoate intermediate. The ethyl protective group was then removed using sodium hydroxide to yield 4-[18F]fluorobenzoic acid, 8 (RCYdc > 99%). The final coupling reaction resulted in the synthesis of [18F]PARPi with a RCYndc = 10% for the whole process and molar activity of 1.8 GBq/µmol as shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Radiosynthesis of [18F]PARPi

This radiotracer marks a significant milestone in the PARP imaging field, an extensive preclinical studies have demonstrated its potential in applications such as the diagnosis of brain, head, and neck cancers (Carney et al. 2016; Souza et al. 2020; Guru et al. 2021), quantification of PARPi target engagement (Carney et al. 2018), efficacy assessment of PARPi treatment, and for differentiation between malignant and non-malignant lesions in lymphomas and gliomas (Tang et al. 2017; Donabedian et al. 2018). However, the most important step was its translation into clinical practice (Schöder et al. 2020). In 2020, Wilson and colleagues proposed a more streamline radiosynthesis of [18F]PARPi, compared to Carney and colleagues (Carney et al. 2016), via a “fast” two-step, one-pot method. As depicted in Fig. 6, the introduction of fluorine-18 occurs via a SNAr reaction on a Boc-protected nitro precursor (9), and the final radiochemical yield was 9.6% comparable with the previous strategy, the total process was shortened to 66 min, placing an advantage working with radiotracers (Wilson et al. 2020).

Fig. 6.

Improved radiosynthesis of [18F]PARPi by Wilson and colleagues

To date, both [18F]-FTT and [18F]PARPi are in clinical translational as imaging agents used in humans to assess in vivo the expression of PARP-1 in oncological patients. They both showed a positive correlation with PARP-1 expression. The trials for considering [18F]FTT and [18F]PARPi as both diagnostic and predictive biomarker in aggressive oncological disease (breast, head and neck, prostate, neuroglioblastoma cancer), potentially enhancing the efficacy of PARP therapy in a selected group of patients are ongoing (Filippi et al. 2023).

Following the success of [18F]PARPi, other researchers expanded the field. In 2018, the Pimlott lab developed a close analogue called [18F]20 (Zmuda et al. 2018). This structure closely resembled the previous tracer but incorporated a methylfluorobenzene moiety instead of the fluorobenzene group (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Radiosynthesis of [18F]20

This slight modification helped retain PARP activity (IC50 = 1.3 nM in G7 human glioblastoma cells) and a favourable tumour uptake (%ID/g = 3.6 after 120 min). However, as it is well known to date, benzyl fluorinated fragments tend to undergo defluorination, leading to off-site fluorine-18 skeletal uptake. Consequently, [18F]20 was discontinued in further investigations. Following the approach of small scaffold modification, in 2018 the Zhou group developed a modified version of [18F]FTT called [18F]WC-DZ-F (Zhou et al. 2018a). The radio-fluorination was performed at the benzene ring's para position, removing the fluoroethoxy group of [18F]FTT. The radiosynthesis process followed a two-step protocol, schematised in Fig. 8. The first step consisted of yielding the [18F]4-fluorobenzaldehyde (13) via a SNAr reaction from an ammonium salt precursor, 12. In the second step, the [18F]WC-DZ-F was synthesised by reacting the diamine precursor (11) with the radioactive intermediate in the presence of 10% Pd/C in methanol, obtaining the final probe with a RCYdc of over 50% and a Am of approximately 37 GBq/µmol.

Fig. 8.

Radiosynthesis of [18F]WC-DZ-F

Although [18F]WC-DZ-F demonstrated superior in vivo blood stability compared to [18F]FTT (78.5% vs. 13% at 30 min), substantial nonspecific uptake in bone and muscle was observed, limiting its potential advantages over the parent probe (Zhou et al. 2018a). Finally, in 2019, a new approach emerged when the Cornelissen and Gouverneur labs decided to introduce fluorine-18 in the same position as the parent drug Olaparib, reporting for the first time the radioisotopologue [18F]Olaparib. They described the direct radiolabelling of a PARPi without any structural modifications (Wilson et al. 2019). The key reaction enabling this milestone procedure was the copper-mediated 18F-fluorodeboronation of a protected boronic pinacol ester precursor. This reaction was previously reported by the Gouverneur group (Tredwell et al. 2014) and further utilized and expanded (Mossine et al. 2015) by the (radio)chemistry community as a relevant technique for radiolabelling (pre)clinical candidate such as [18F]Fluorodopa (Mossine et al. 2019, 2020), [18F]JNJ-46356479, [18F]FITM (Das et al. 2024; Yuan et al. 2020) Flumazenil (Gendron et al. 2022) and many others (Wright et al. 2020). The [18F]Olaparib was obtained with an 18.3% of activity yield no-decay corrected (AYndc) and a Am = 25.7 GBq/μmol in 135 min. The probe behaves similarly to the parent drug, and both in vitro and in vivo experiments demonstrated a correlation between its uptake and PARP1expression levels in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cells. The same groups decided to scale up the radiofluorination procedure and develop a fully automated radiosynthesis compatible with Eckert and Ziegler Modular Lab systems (Guibbal et al. 2020a). Thanks to this new procedure, Guibbal and coworkers successfully afforded the [18F]Olaparib in a range of 1 to 11% AY and a Am between 78 and 319 GBq/μmol, opening up promising new perspectives for routine production (Guibbal et al. 2020a), as shown in Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Manual and automated radiosynthesis of [18F]Olaparib

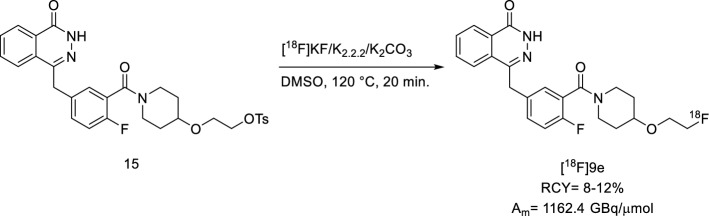

Later, the Maurer group focused on optimizing the reaction for [18F]Olaparib. The main focus was on the implementation of the Design of Experiments (DoE) approach, a statistical toolset that provides a detailed model of processes’ performances concerning multiple experimental variables (factors), while minimizing the number of optimization experiments. Here, Bowden and colleagues analysed several crucial factors such as the fluorine-18 processing method, base, eluting solvents, and QMA loading direction, they translated the small-scale reaction experiments to full batch synthesis. This winning approach increased the AY to 41% and RCY to 80% (Bowden et al. 2021a). The search for more effective drugs is ongoing. In clinical settings, Olaparib has demonstrated resistance mechanisms that remain poorly understood. Some preclinical studies have shed light on the drug being heavily effluxed by the transporter P-glycoprotein (P-gp). For this reason, a new PARP inhibitor, AZD2461, was developed as a next-generation agent demonstrating efficacy against Olaparib-resistant tumours that overexpress P-gp. Additionally, it showed lower levels of haematological toxicity in mice and was found to be a weaker inhibitor of PARP3 compared to Olaparib (O’Connor et al. 2016). The Mach group hypothesised that its ability to evade P-gp might lead to improved blood–brain barrier (BBB) penetration. Therefore, in 2019, they developed the [18F]9e, an analogue of AZD2461. Although this drug is closely related to Olaparib and, consequently, to its radioisotopologue, Riley and colleagues decided to incorporate a fluoroethoxy group, recalling the [18F]FTT probe (Reilly et al. 2019). The radiosynthesis step relied on a typical SN2 from a tosylate precursor, 15, in the presence of [18F]KF, K2.2.2, and K2CO3 (Fig. 10). The [18F]9e was afforded a RCY of 8–12% and with a Am of 1162.4 GBq/µmol.

Fig. 10.

Radiosynthesis of [18F]9e

However, further analysis did not show any appreciable brain uptake in non-human primates sinking Mach’s lab hypothesis, hence this radiotracer is not suitable to investigate PARP1in neurodegenerative diseases. In 2019, Shuhendler and colleagues introduced the [18F]SuPAR as a novel probe for non-invasive imaging of PARP-1/2 activity using PET (Shuhendler et al. 2019). This tracer is a radiofluorinated analogue of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), the native substrate of PARP. The main challenge in its radiosynthesis arose from the fact that the nicotinamide moiety is lost during nucleophilic substitution with the NAD acceptor, meaning any modifications are limited to the adenosine moiety of the poly-ADP ribose product. This limitation led to the development of a click chemistry approach, in which an F-PEG2-N3 side chain was attached to the adenosine nitrogen via a click reaction. The radiochemical process involved a two-step reaction: first, a radiofluorination of 3-(2-(2-tosylethoxy)ethoxy)azide (17) to yield [18F]-PEG2-azide (18), followed by the click reaction with precursor 16. This radiolabelling protocol achieved a 3.6% overall radiochemical yield of [18F]SuPAR with a 4.01 GBq/μmol molar activity as reported in Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.

Radiosynthesis of [18F]SuPAR

Although [18F]SuPAR demonstrated interesting in vitro results, the in vivo assessment of PARP activity was complicated because NAD + also serves as a substrate for other enzymes. Just one year after Riley’s work on AZD2461, the Gouverneur and Cornelissen groups reported the PARPi radioisotopologue. The radiofluorination was carried out via the well-established copper-mediated fluorine-18-fluorodeboronation, using both manual and automated procedures. The activity yields were reported as follows: AY = 9% ± 3% and Am of up to 17 GBq/μmol for non-automated radiosynthesis, AY = 3% ± 1% and Am = 237 GBq/μmol for the automated counterpart, with activity yields no-decay corrected (Guibbal et al. 2020b) (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12.

Manual and automated radiosynthesis of [18F]AZD2461

[18F]AZD2461 showed a reduced cellular uptake in PSN-1 cells when compared to [18F]Olaparib. Furthermore, in vivo studies showed that [18F]AZD2461 uptake could not be completely blocked by the non-radioactive AZD2461, whereas it was more efficiently inhibited by Olaparib (Shuhendler et al. 2019). These findings suggest that AZD2461 may bind to targets other than PARP-1/2. Thanks to the great variety of PARP radiotracers available at both preclinical and clinical levels, imaging of PARP expression has become an important and reliable strategy for predicting tumour malignancy. However, most of these tracers, due to their small-molecules nature, suffer from high hepatobiliary clearance, which limits their use. In 2021, the Maurer group aimed to address this issue by modifying the Olaparib scaffold to enhance renal clearance, resulting in the development of the new radiotracer [18F]FPyPARP (Stotz et al. 2022). The novel radiotracer is an analogue of [18F]PARPi, but in order to decrease the calculated partition coefficient (clogP) ([18F]PARPi: 3.36 vs [18F]FPyPARP: 2.49) the Maurer group introduced a fluoronicotinic moiety instead of fluorobenzene one. The radiolabelling approach was designed based on [18F]PARPi method, utilizing a two-step synthesis. The prosthetic group [18F]2,3,5,6-tetrafluorophenyl 6-fluoronicotinate (21) was afforded in one step from its ammonium precursor 20 via a SNAr reaction. This was then coupled with 4-(4-fluoro-3-(piperazine-1-carbonyl)benzyl)phthalazine-1(2H)-one to yield [18F]FpyPARP with a RCY of 9.9 ± 6.7% and a Am = 31 ± 12 GBq/μmol, as shown in Fig. 13.

Fig. 13.

Radiosynthesis of [18F]FpyPARP

When this tracer was evaluated in vivo, the fluoropyridine modification resulted in detectable bladder uptake in all animals, indicating a decent level of renal clearance, in contrast to [18F]PARPi and [18F]FTT. Based on these findings, we can conclude that [18F]FpyPARP may serve as a viable alternative to the previous tracers. On the other hand, the Cornelissen and Gouverneur labs chose not to introduce any modifications to their radiotracers. Leveraging the reliable Cu(II)-mediated 18F-fluorodeboronation, they successfully radiosynthesised the radioisotopologue of another important PARPi, [18F]Rucaparib, in 2021 (Chen et al. 2021), whose radiosynthesis is reported in Fig. 14.

Fig. 14.

Radiosynthesis of [18F]Rucaparib

In a subsequent study, [18F]Rucaparib was tested both in vitro and in vivo on human pancreatic cancer models, where its uptake was shown to be dependent on PARP1expression. Additionally, in vivo studies demonstrated relatively fast blood clearance and a significant reduction in [18F]Rucaparib uptake when different PARP inhibitors were administered suggesting PARP-selective binding (Chan et al. 2022). It can be stated that producing radioisotopologues of the different PARP inhibitors is a winning strategy, as it allows for a deeper understanding of the physicochemical and biological properties of the selected inhibitor. Based on this premise, the Maurer and the Xu groups independently reported the radiosynthesis and biological evaluation of the most potent PARPi, the [18F]Talazoparib (Bowden et al. 2021b; Zhou et al. 2021). The two groups adopted different approaches to radiosynthesis, despite both opting to radiolabel the fluorine on the benzene ring outside the phtalazone core. The Maurer group, following their experience with [18F]Olaparib optimization using DoE, utilised the Cu(II)-mediated fluorine-18-fluorodeboronation reaction designing an ad hoc protected boronate precursor 23. Here, the automated two-step radiosynthesis, radiofluorination and acidic deprotection, afforded [18F]Talazoparib with an AY = 4–8% and a Am = 52–176 GBq/μmol, as reported in Fig. 15.

Fig. 15.

Radiosynthesis of [18F]Talazoparib proposed by Bowden and colleagues (Maurer group)

Moreover, since the PARPi is chiral, the chiral product was isolated from the reaction mixture using a reversed-phase/chiral column (> 99% ee). Interestingly, thanks to DoE again, the group was able to modify different parameters of the radiolabelling reaction moving forward from the previous one developed by the Gouverneur group, also leading to an increase RCY and Am. On the other hand, the Xu group adopted a multistep technique, something quite unusual in the radiofluorination field. They started from the 4-formyl-N,N,N-trimethylbenzenammonium salt precursor, 24, to yield the fluorine-18 labelled benzaldehyde 25, then they performed two subsequent ring closures to afford the racemic [18F]Talazoparib. Lastly, the chiral separation was performed on a reverse phase semi-preparative chiral column to obtain [18F]Talazoparib with a chiral purities of 98% and a Am = 28 GBq/μmol, as shown in Fig. 16.

Fig. 16.

Radiosynthesis of [18F]Talazoparib proposed by Zhou and coworkers

When tested in vivo, both groups agreed that the radiotracer displays a favourable pharmacological profile in agreement with its reported high trapping efficiency. The wave of PARPi radioisotopologue did not stop with Olaparib, Rucaparib, AZD2491, and Talazoparib but it continued with [18F]Pamiparib and [18F]AZD9574. [18F]Pamiparib was evaluated by Tong and colleagues as a novel BBB penetrable PARP PET tracer in mice, rats and non-human primates (Tong et al. 2022). However, the tracer showed high uptake in the spleen but relatively lower in other organs, even if ex vivo autoradiography and metabolism studies on rats indicated some brain penetration. The radiosynthesis of [18F]Pamiparib (Fig. 17) may seem to rely on Cu(II)-mediated fluorine-18-fluorodeboronation, yielding the probe with RCYdc of 2 ± 1.4% and a Am of 127 ± 7 GBq/μmol.

Fig. 17.

Radiosynthesis of [18F]Pamiparib

Last year, another BBB penetrant PARPi was reported by the Liang group, the [18F]5 (AZD9574 radioisotopologue) (Zhou et al. 2024). The peculiar scaffold of this molecule bears two fluorine atom in different positions: the first one sits on a heterocycle moiety that can perhaps hamper a possible Cu(II)-mediated fluorine-18-fluorodeboronation due to the presence of nitrogen. The second fluorine is placed in ortho- position to the pyridine nitrogen, representing an easy access point for a SNAr radiofluorination. The Liang group decided to opt for the second fluorine for introducing the fluorine-18. After the synthesis of a brominated precursor (8), the latter was easily radiolabelled in the presence of [18F]TBAF, affording [18F]5 with 15% RCYndc and a Am greater than 37 GBq/μmol (Fig. 18).

Fig. 18.

Radiosynthesis of [18F]5 ([18F]AZD9574)

The group also demonstrated the capacity of [18F]5 for specific binding to PARP1and successful penetration of the BBB. These findings suggested that [18F]5 is a viable molecular imaging tool for PARP1-related brain disease.

Iodine (123I, 124I, 125I, 131I)

The first radioiodinated PARPi tracer was developed by Zmuda and coworkers in 2015 (Zmuda et al. 2015), following some extensive efforts to obtain a small library of cold iodinated analogues of Olaparib, with structural variance in the cyclo-propane region. For practical reasons, optimization of the radiolabelling reaction was performed using the long-lived 125I-radionuclide (half-life of iodine-125 of 60.1 days vs that of iodine-123 of 13.2 h). The authors started from the reaction conditions described by Gildersleeve (Gildersleeve et al. 1996), the temperature, reaction time, and the presence of air were screened, by individuating the optimal conditions for iodine-123 solid-state aromatic halogen exchange radioiodination (Pimlott et al. 2008). The results reported a RCYndc of 36.5 ± 7.2% (n = 6) and a Am of > 703 ± 0.38 GBq/μmol (n = 4), as shown in Fig. 19. The authors laid the foundation for future investigation of [125I]5 as SPECT agent, by preliminary conducting ex vivo biodistribution experiments in female nude mice bearing subcutaneous human glioblastoma xenografts.

Fig. 19.

Radiosynthesis of [125I]5

Almost simultaneously with Zmuda work, a two-synthetic steps radiolabelling procedure for [131I]I2-PARPi and [124I]I2-PARPi labelling was established by Salinas and coworkers (Salinas et al. 2015). An electrophilic substitution of the (Bu)3Sn labelled cold precursor with iodine-131 or iodine-124 in mild conditions was addressed, leading to a Am between 7.4–10.7 and 5.5–8.5 MBq/µmol for [131I]I2-PARPi and [124I]-I2-PARPi, respectively. In detail, in the first step, the precursor N-succinimidyl-4-(tributylstannyl) benzoate 30 was labelled in the presence of [131/124I]NaI and chloramine T in acetic acid. The resulting radioactive N-succinimidyl-4-iodo benzoate (31) was then conjugated to a PARP1 targeting 2H-phthalazin-1-one (32) in the presence of HBTU and acetonitrile at room temperature. The crude products were purified by HPLC, obtaining [131I]I2-PARPi with a RCY of 72 ± 8% (n = 12) and [124I]I2-PARPi with a RCY of 68 ± 5% (n = 5) (Fig. 20).

Fig. 20.

Radiosynthesis of [131/124I]-I2-PARPi

These two agents were tested as PET and SPECT imaging probes in orthotopic glioblastoma imaging, showed selective accumulation in the tumor tissue. Later on, [131I]PARPi was obtained similarly by Jannetti and coworkers (Jannetti et al. 2018) reporting a RCY of 70% (Fig. 21). They described the application of the agent for radiotherapy, treating mice bearing a subcutaneous glioblastoma model, showing a significant longer survival than mice receiving vehicle.

Fig. 21.

Radiosynthesis of [131I]PARPi

The identical iododestannylation strategy was adopted in the Anderson and Makvandi works. They report, respectively, the first example of a radioiodinated analogue of the benzimidazole class of PARPi ([125I]KX-02-019) (Anderson et al. 2016) and the compound [125I]KX1 as a PARP1-selective radiotracer that can accurately measure PARP expression in vitro and in vivo (Makvandi et al. 2016). In vivo biodistribution studies for [125I]KX-02-019 showed an increasing tumor to muscle ratio over 6 h, as well as fast clearance from healthy tissues. The authors reported for both the compounds an average RCY of 70%, a typical AY ranged from 74 to 222 MBq of radiolabelled product and the radiochemical and chemical purity of the product higher than 95%, as shown in Fig. 22.

Fig. 22.

Radiosynthesis of [125I]KX-02-019 and [125I]KX1

The primary limitation of this method, which hinders its clinical application, is the contamination of the radiotracer with organotin residues. Despite this issue, many small-molecule radiotracers, such as [125I]AGI-5198 (Chitneni et al. 2018), have been successfully prepared using radioiododestannylation approach. A milestone in the field was represented by the general method for the copper mediated nucleophilic iodine-123 123I-iodination of (hetero)aryl boronic esters and acids developed in 2016 by Wilson and coworkers (Wilson et al. 2016). This process avoided the general drawbacks related to organotin precursors such as their stability and toxicity, and possible tin residues contamination of the obtained radiotracer (Dubost et al. 2020). Concomitantly to the Gouverneur’s work, Zhang and colleagues published an iododeboronation procedure (Zhang et al. 2016) starting from boronic acids using a copper(I) catalyst, Cu2O. Using iodine-131 as the radioisotope, the reaction occurred smoothly at room temperature in one hour, achieving RCYs between 87 and 99%. Precisely based on Zhang's work, Reilly and his collaborators (Reilly et al. 2018) tried to further optimize this iodination strategy. They screened several Cu-sources and various functional groups on aryl boronic esters in order to identify an efficient catalyst for iodine-125-radiolabelling of aryl boronic esters that could be translated to astatination. They found that by using 1:1 ratio of Cu(py)4(OTf)2 and the electron-rich ligand 3,4,7,8-tetramethyl-1,10-phenanthroline led to excellent RCYs of PARPi precursors investigated (Destro et al. 2023; Chan et al. 2023). Almost simultaneously, the structurally similar [123I]-MAPi and [125I]-PARP-01 were synthesized by Wilson and coworkers (Wilson et al. 2023) and Sankaranarayanan and colleagues (Sankaranarayanan et al. 2022), respectively. Both groups used a one pot iododestannylation protocol, but the first ones used N-chlorosuccinimide (NCS) as oxidant, while the second ones preferred chloramine T. They obtained different results in terms of AY and Am: 45 ± 2% and 11.8 ± 4.8 GBq/µmol for [123I]MAPi, 78 ± 11.8 and 30.52 ± 6.4 GBq/µmol for [125I]-PARP-01 as reported in Fig. 23. The above reported procedure for [123I]MAPi radiosynthesis actually represents an improved version of the protocol reported in a previous work (Pirovano et al. 2020). We can state that, generally, the methodology described so far related to electrophilic iodination rely on the use of an external oxidant such as hydrogen peroxide, NCS or Chloramine T. They also need acidic conditions adding some acetic acid. The reaction temperature and solvent can vary depending by the group experience with the reaction.[125I]-PARPi-01 showed PARP1-specificity and higher cytotoxicity than Olaparib in TNBC cell lines.

Fig. 23.

Radiosynthesis of [123I]MAPi and [125I]-PARPi-01

Later on, [123I]GD1 was synthesized via copper-mediated radioiodination by Destro and colleagues, thus modifying the previously developed procedure for [18F]Rucaparib (Chen et al. 2021). The authors testes two radiosynthetic approaches: a two-step radiolabelling from the appropriate boronic pinacol ester containing an aldehyde handle to be further functionalized (38), and another from a Boc-protected benzylamine boronic pinacol ester (39) followed by deprotection (Fig. 24). They tested a series of copper-mediated radioiodination conditions (Wilson et al. 2016) and concluded that precursor 39 is a superior starting material for the radiosynthesis of [123I]GD1 (RCY: 90%, AY: 45 ± 8% and Am up to 20 GBq/µmol), reasonably due to the Boc-protected benzylamine chain which circumvents the issue relative to the presence of copper in the reductive amination step. Significantly reduced clonogenic survival was observed in vitro after [123I]GD1 exposure of cells for 1 h, but biodistribution and SPECT imaging of wild type C57BL/6 mice showed prolonged retention in the abdominal region that could lead to long-term toxicity.

Fig. 24.

Radiosynthesis of [123I]GD1

[123I]CC1 was developed by Chan and colleagues via a copper-assisted radiodeboronation from the boronic pinacol ester 40, basing on their previous work (Wilson et al. 2019). They obtained [123I[CC1 with a RCY of 93.6 ± 0.8% and Am of 18–342 GBq/µmol as shown in Fig. 25. They found [123I]CC1 binds selectively to PARP, causes damage to DNA double-strand breaks in vitro, and reduces clonogenic survival in vitro and tumor growth in vivo.

Fig. 25.

Radiosynthesis of [123I]CC1

For the sake of completeness, we reference the works of Makvandi et al., Pirovano et al., Lee et al., Riad et al., and Wilson et al., which are built upon the foundational studies already cited in this review (Jannetti et al. 2018; Makvandi et al. 2016; Reilly et al. 2018).

Bromine (76Br, 77Br)

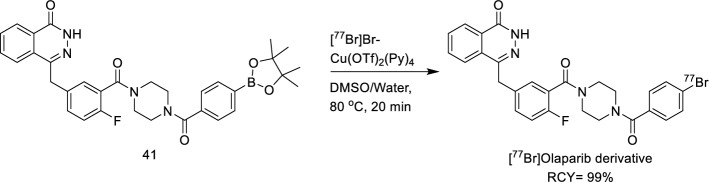

Radiobromine offers several advantages over radiofluorine and radioiodine. Unlike fluorine, which has only one radioisotope (fluorine-18) for PET imaging, bromine provides more versatility. Bromine's smaller size and the stronger C–Br bond (335 kJ/mol compared to C-I's 268 kJ/mol) enhance the in vivo stability of brominated compounds, potentially improving their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties. Additionally, radiobromide does not carry the same risk of thyroid accumulation as radioiodide and diffuses evenly throughout the body with only the stomach reaching higher uptake than blood (Hoffman et al. 2023). Radiobromine is important in both diagnostic and therapeutic nuclear medicine, with bromine-76 (t1/2 = 16.2 h, 55% β+) used for PET imaging and bromine-77 (t1/2 = 57.0 h, 6–7 Meitner-Auger electron—MAe—per decay) and bromine-80 m (t1/2 = 4.4 h, 7–8 Auger and Coster-Kronig electrons per decay) used for radiotherapy as Auger electron emitters (Eckerman and Endo 2008). In 2018 Zhou and co-workers described the copper-mediated nucleophilic radiobromination of aryl boron precursors and successfully synthesised a radiobromine-labelled Olaparib derivative using the developed method (Zhou et al. 2018b). Up to then, the major strategies for radiobromination (Moerlein et al. 1988) were represented by the oxidative electrophilic radiobromination and the copper-catalysed halogen-exchange reaction (Zhou et al. 2017). Starting from their previous work on radiobromination of iodonium precursors by nucleophilic substitution, in 2018, Zhou and co-workers developed a modified strategy with improved radiochemical yield and purification step. They described a copper-mediated nucleophilic radiobromination of aryl boron precursors and successfully synthesised a radiobromine-labelled Olaparib derivative using the developed method. They set a clean and feasible protocol for purification, using a variety of solvents, temperatures and catalysts. Moreover, the protocol highlights the uncommon finding according to which the water tolerance for this radiobromination is in sharp contrast to that of radiofluorination, which afforded no RCY in the presence of water. A radiobromine-labelled derivative of Olaparib was synthesised by them previously, using a tedious two-step route (Zhou et al. 2017) that proceeded in very low yield. However, using the new current method and starting from the corresponding boronic acid precursor 41, they were able to produce the radiobromine-labelled derivative in aqueous DMSO in 99% RCY as reported in Fig. 26.

Fig. 26.

Radiosynthesis of [77Br]Olaparib derivative

Building on Zhou's and Reilly’s works (Reilly et al. 2018; Zhou et al. 2018b), Ellison and collaborators synthetized the [77Br]KX1 (Rucaparib derivative) via copper-mediated aryl boronic ester radiobromination (Ellison et al. 2020) (Fig. 27).

Fig. 27.

Radiosynthesis of [77Br]KX1

The synthesised radiotracer had an estimated Am of up to 700 GBq/μmol. Large reaction volume and water content negatively affected the radiochemical reactivity of the copper-mediated aryl boronic ester bromination. In 2023, Mixdorf and colleagues (Mixdorf et al. 2023) investigated the effect that bromine-76 and bromine-77 QMA cartridge trap/release conditions have on downstream copper-mediated deboro-bromination and the radiochemistry’s tolerance to common functional groups. They found (CH3)2NH as the optimal QMA elution agent and using the catalyst system (i.e., [Cu(py)4(OTf)2]/3,4,7,8-tetramethyl-1,10 phenanthroline) reported by Mach for radioiodination/astatination of aryl boronic pinacol esters (Reilly et al. 2018), they tested the tolerability of the protocol to various functional groups. Thus, they applied the optimized method to the preparation of Rucaparib derivative labelling it from its bis(pinacolato)diboron (Bpin) precursor leading to high RCY (89 ± 4%, n = 7). The work presents a reproducible, high-yielding QMA-cartridge-based method for preparing reactive [76/77Br]-bromide for late-stage nucleophilic copper-mediated coupling to (hetero)aryl-boronic pinacol esters. Compared with previous deboro-radiobromination reports (Kondo et al. 2022; Mossine et al. 2017) the method is effective with milder conditions, less precursor, and more radioactivity as depicted in Fig. 28.

Fig. 28.

Radiosynthesis of 20 (Olaparib derivative) and 21 (RD1)

[76/77Br]RD1 was synthetized by the same research group (Hoffman et al. 2023) following the above described method (Mixdorf et al. 2023). [77Br]Br-WC-DZ targeting PARP1 (Rucaparib derivative) was synthesised in 2023 by Sreekumar and coworkers (Sreekumar et al. 2023) via copper-mediated nucleophilic radiobromination of a boron precursor with [77Br]Bromide as previously reported by the authors (Zhou et al. 2018b) with a Am of 777 ± 181.3 GBq/µmol (n = 12) (Fig. 29). The intravenous injection of [77Br]Br-WC-DZ in nu/nu mice bearing PC-3 and IGR-CaP1 tumors conferred a significant survival advantage, demonstrating a delay in tumor growth and lacking of radionuclide-induced systemic toxicity.

Fig. 29.

Radiosynthesis of [77Br]Br-WC-DZ

Astatine (211At)

Astatine was synthesised for the first time in 1940 at the University of California, Berkeley (Corson et al. 1940), and its use on humans was first reported as early as 1954 (Hamilton et al. 1954). Astatine-211 has a half-life of 7.2 h, which is a crucial advantage over tissue exposure. Reilly and co-workers have demonstrated the first approach to astatinated compounds using boronic ester precursors, providing an efficient and nontoxic protocol that eliminates the traditional need for toxic organotin reagents (Reilly et al. 2018). Moreover, their protocol eliminates elevated temperatures, and extended reaction times, providing a more practical and environmentally friendly approach to developing α-emitting radiotherapeutics. Traditional routes to astatinated compounds proceed through electrophilic destannylation of an organotin functional group (Reilly et al. 2018; Adam and Wilbur 2005). In 2016, Brechbiel and co-workers illustrated the use of aryl iodonium salts to access astatinated aryl compounds through an SNAr mechanistic pathway (Guérard et al. 2016). Despite the high yields obtained using this method, astatination of the conjugate aryl group results in unwanted side-product formation. Based on previous reports illustrating the versatility of the Chan − Evans − Lam reaction to access radioiodinated and fluorinated compounds via boronic reagents, they adapted a similar strategy to access astatine-211-labelled hetero(aryl) synthons. Makvandi and collaborators synthesised [211At]MM4 as reported previously for the radiosynthesis of [125I]KX1, except for the final step of radiohalogenation, where astatine-211 was used instead of iodine-125. Based on the Rucaparib scaffold, [211At]MM4 was synthesised using a stannylated precursor 35 and electrophilic aromatic substitution. The radiochemical purity of [211At]MM4 was greater than 95%, and its Am ranged from 950 to 16.021 GBq/μmol as shown in Fig. 30. The authors evaluated the in vivo antitumor efficacy of [211At]MM4 both with a single or fractionated dose administration, showing initial reductions in tumor volume and delayed tumor growth compared with controls.

Fig. 30.

Radiosynthesis of [211At]MM4

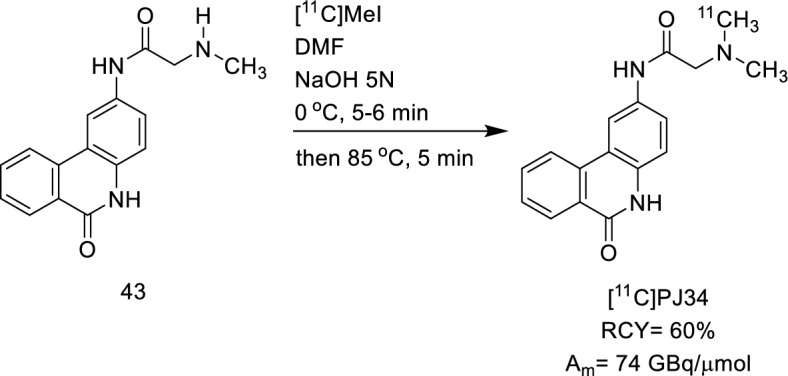

Carbon (11C)

Carbon-11 radiotracers are essential tools for the early detection of cancer, evaluating treatment responses, and studying the pharmacokinetics of anticancer drugs. However, carbon-11's short half-life (20.38 min) presents challenges in tracer synthesis, including the need for high RCY, purity, and Am within a brief time frame and small scale. In 2005, Tu and coworkers developed the [11C]PJ34 radiotracer for PARP1 imaging (Tu et al. 2005). The synthesis of [11C]PJ34 (Fig. 31) was accomplished by base-catalysed reaction of the corresponding des-methyl precursor, 43, with [11C]methyl iodide. The radiolabelling was conducted by phenol methylation with [11C]MeI. The authors found that NaOH addition in the reaction of the des-methyl precursor with [11C]MeI is required to obtain a satisfying yield. This method leads to a RCY of 60% and a Am of ~ 74 GBq/µmol.

Fig. 31.

Radiosynthesis of [11C]PJ34

The authors proved the high affinity of the compound for inhibiting PARP-1 activity (IC50 = 20 nM) and the high uptake of the radiotracer in tissues known to undergo necrosis, anticipating the radiotracer potentiality as PET tracer. Indeed, Andersen and collaborators (Andersen et al. 2015) focused their efforts on identifying wider carbon-11-labelling protocols than carbon-11-methylation. They proposed using a pre-generated (Aryl)Pd(X)Ln (44) oxidative addition complex as a potential solution. Additionally, the steps required for the formation of a phosphine-ligated, catalytically active palladium complex would be eliminated, effectively removing two potentially slow reaction steps. They achieved an improved purity and RCY of the final compound carbon-11 labelled Olaparib as shown in Fig. 32.

Fig. 32.

Radiosynthesis of [11C]Olaparib

Later on, inspired by Andersen's work (Quesnel et al. 2015; Lagueux-Tremblay et al. 2018), Ferrat and colleagues investigated the carbon-11-labelling of primary benzamides (Ferrat et al. 2021), since the primary benzamide motif is present in a wide range of biologically relevant compounds. In this context, [11C]Niraparib and [11C]Veliparib were synthesised by a two-step one-pot procedure, starting from their N-Boc-protected iodoarene derivatives 46 and 47. [11C]Veliparib and [11C]Niraparib were obtained at a Am, respectively, 9.9 GBq/μmol and 10.0 GBq/μmol (Fig. 33).

Fig. 33.

Radiosynthesis of [11C]Niraparib and [11C]Veliparib

Despite the potential use of PARP imaging with radiohalogen and radiocarbon-labelled PARP inhibitors in preclinical studies has been extensively demonstrated (Mateo et al. 2019; Farmer et al. 2005; Pascal 2018; Hassa et al. 2006; Alhmoud et al. 2020; D’Andrea 2018; Pommier et al. 2016; Kubalanza and Konecny 2020; Lord and Ashworth 2012; Ferraris 2010), some efforts have been focused on finding better alternatives to overcome drawbacks such as high accumulation of radioactivity in the abdomen due to hydrophobic behaviour of that tracers and radionuclides production and delivery. To date, only [64Cu]Cu-DOTA-PARPi, [68Ga]Ga-DOTA-Olaparib, [68 Ga]Ga-SMIC-2001 and [99mTc]Tc-CNPN and [99mTc]Tc-(TPPTS/tricine)-NPBHYNIC are radiolabelled with metal nuclides.

Copper (64Cu, 67Cu)

Copper-64 decays via positron emission and it has a radioactive half-life of 12.7 h. The decay properties of copper-64 (β + with 17.4% efficiency, Emax = 0.656 MeV, β-with 39% efficiency, Emax = 0.573 MeV) allow for PET images comparable in quality to those obtained using fluorine-18. Thanks to its longer half-life compared to fluorine-18 and chemistry versatility, copper is an attractive alternative to the shorter-lived radionuclides for PET imaging of peptides, antibodies, and small molecules that may require longer circulation times. In radiolabelling with radiometals, the presence of a specific chelator is essential. Chelators are cyclic structures containing atoms such as N, O, P, and S, which can form bonds with central metal atom through their lone pair electrons. These structures typically have a higher molecular weight compared to the smaller fragments used in medicinal chemistry. However, Huang and coworkers (Huang et al. 2017) suggested that, based on the Olaparib core scaffold, several imaging agents have already been developed by incorporating large units, such as the BODIPY dye and trans-cyclooctenes. Hence, the introduction of a chelator may slightly affect Olaparib binding affinity. Therefore, they modified the Olaparib cyclopropyl tail, removing it and installing a dodecane tetraacetic acid (DOTA) chelator able to complex copper-64 affording compound 49 as reported in Fig. 34.

Fig. 34.

Radiosynthesis of [64Cu]Olaparib DOTA derivative

Even if the tumour uptake in mesothelioma mice models was satisfying (3.45% ID/g in 1 h), the conjugation of the bulky and large chelator led to a decrease in binding affinity by 40%. These findings highlight the need to thoroughly investigate major structural modifications relative to the parent PARPi—ideally through molecular docking or IC₅₀ assays—before implementing such significant changes.

Gallium (68 Ga)

The radiochemistry behind fluorine-18 and gallium-68 is undoubtedly different. While fluorine-18 demands several precautions, gallium-68 radiolabelling protocols are generally more friendly to use. The radiolabelling strategy substantially differs from those described in the past sections, as gallium-68 is a radiometal. Briefly, the gallium-68 radiolabelling procedure needs a buffer solution to adjust the optimal complexation pH, heating in case of a heat-needed complexation reaction, and a solid-phase extraction (SPE) separation to discard the free gallium content and colloidal species. The first gallium-68-labelled PARP inhibitor was developed by Wang and collaborators in 2023 showing its potential application for PARP imaging (Wang et al. 2023) as PET tracer in SK-OV-3 tumor bearing mice (ovarian tumor). They labelled a DOTA-containing- Olaparib (50) in sodium acetate buffer, at 100° for 10 min. A C-18 column (SEP-PAK) was employed to purify the mixture and to achieve a high radiolabelling yield product (> 97%), as reported in Fig. 35. The tracer proved to be specific to PARP expression, by leading to a tumor uptake dependent on PARP1 level.

Fig. 35.

Radiosynthesis of [68Ga]Ga-DOTA-GABA-Olaparib

In 2024, [68 Ga]Ga-SMIC-2001 was evaluated in U87MG xenograft models as a PARP1imaging tracer (He et al. 2024) by He and colleagues. After reacting in acetate buffer (pH = 4.5) at 95 °C for 10 min, the tracer was purified on Sep-Pak C18 cartridges. A high RCY was achieved (> 90%) with a purity of > 99% and a Am of 3.51 MBq/nmol, as shown in Fig. 36. In vivo study revealed that it exhibited a high tumor-to-background contrast in the U87MG xenograft models and mainly renal clearance.

Fig. 36.

Radiosynthesis of [68Ga]Ga-SMIC-2001

More recently, the Niraparib-derivative [68 Ga]Ga-DOTANPB has been developed as a potential PET tracer for targeting PARP1 by Wang and co-workers (Wang et al. 2025a). Containing the DOTA chelator (52), the radiolabelling procedure is almost identical to that previously described. Acetate buffer was used to adjust the pH to 4, the mixture was heated at 100° C for 10 min and purified on Sep-Pak C18 column (Fig. 37).

Fig. 37.

Radiosynthesis of [68Ga]Ga-DOTANPB

For completeness, we mention the work of Li and colleagues, who developed gallium-containing nanoparticles as an alternative to platinum use in cases of cisplatin-resistant tumours (Li et al. 2023). However, as this review focuses on the radiochemistry behind PARP inhibitors, the cited study has not been included in the discussion.

Technetium (99mTc)

One of the most utilised radionuclides is definitively Technetium-99 m, which we can consider the workhorse of diagnostic nuclear medicine (SPECT imaging). Technetium-99 m has ideal nuclide properties (t1/2 = 6.02 h, γ = 140 keV), is easy to obtain, and does not require expensive facilities or complicated procedures for the radiolabelling process (Duatti 2021; Riondato et al. 2023). For these reasons, the group of Zhang (Wang et al. 2024) decided to merge this radiometal with the Niraparib scaffold to create a new derivative as a diagnostic probe. To coordinate technetium-99 m, the group selected the Isocyanate (− NC) chemistry since it is a strong coordinating group that can form a stable complex with the radiometal. Then, to overcome the possible solubility issues, they added a polyethylene glycol (PEG) chain to increase hydrophilicity at the final piperidine moiety of Niraparib. In this way, they create a Niraparib molecule with a long PEG chain bearing an isocyanate, 53, to use as a ligand to coordinate the radiometal. The radiosynthesis (Fig. 38) afforded [99mTc]Tc-CNPN with a Am ranged from 2.14 to 221.36 GBq/μmol (no RCY is reported).

Fig. 38.

Radiosynthesis of [99mTc]Tc-CNPN

In this study, no IC50 assay was performed to understand if the modification on the scaffold could have hampered the selectivity of the compound. Moreover, no proof of tracer internalization was performed, to our belief, it is crucial to understand the probe fate in the nucleus, especially for PARPi. Indeed, [99mTc]Tc-CNPN tumour uptake was only 0.78 ± 0.11%ID/g at 2 h p.i., and slightly reduced to 0.44 ± 0.06%ID/g when blocked. Sakr and colleagues (Sakr et al. 2024) reported another use of technetium-99 m and PARPi where, combining nanotechnology and radiochemistry, they developed an efficient nano-system conjugating the radiometal with a 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinazo-line-7-sulfonamide scaffold for possible application as a theranostic agent. They used carboxylated graphene oxide nanosheets (NGO-COOH) as a platform to conjugate the new PARPi via peptide coupling. Then, the same were radiolabelled with technetium-99 m to yield [99mTc]Tc-NGO-COOH-3 with a RCY of 98.5.0 ± 0.5%, however no precise structure of the labelled compound is reported. The results of radiolabelled nanodrug injection in solid tumour-bearing mice revealed a nice degree of localization of the nano-system at tumour tissue. The Zhang group reported a new technetium labelled Niraparib probe (Wang et al. 2025b). The group decided to modified the PARPi scaffold adding a quite encumbering moiety, the hydrazinonicotinamide group, indeed the in vitro affinity was worst compared to the parent molecule (IC50 = 450.90 nM vs IC50 = 3.8 nM). This moiety serves as ligand for technetium-99 m labelling and six different co-ligands were screened to yield the best probe. No in vitro assays were performed, hence no internalization test was tried. However, [99mTc]Tc-(TPPTS/tricine)-NPBHYNIC and [99mTc]Tc-(NIC/tricine)-NPBHYNIC (Fig. 39) were selected for biodistribution, based on their LogD values (−2.13 for TPPS vs −1.14 for NIC), in HeLa tumor-bearing BALB/c nude mice at 2 h post injection. The results revealed that the tumor uptake of [99mTc]Tc-(TPPTS/tricine)-NPBHYNIC (1.02 ± 0.07% ID/g) was greater than that of [99mTc]Tc-(NIC/tricine)-NPBHYNIC (0.36 ± 0.05% ID/g).

Fig. 39.

Radiosynthesis of [99mTc]Tc-(TPPTS/tricine)-NPBHYNIC and [99mTc]Tc-(NIC/tricine)-NPBHYNIC

Conclusions

PARP imaging and radiotherapy is a dynamic and rapidly growing field with potential application in the fields of both oncological and neurological diseases. The primary challenge in developing these probes lies in the radiolabelling methodologies. Typically, small modifications to the core scaffold or the development of radioisotopologues, when feasible, are the most pursued strategies. Figure 40 illustrates the progression of PARPi radiolabelling, highlighting how these methodologies have advanced or diverged from conventional nucleophilic (aromatic) substitution.

Fig. 40.

A timeline showcasing the evolution of radiochemistry in labelling PARP inhibitors

In the context of radiohalogenation, copper-mediated radiolabelling appears to be the method of choice, although several other methodologies have been described, particularly in the fluorine-18 field (Ajenjo et al. 2022). However, the reaction involves several parameters that need to be considered, such as the amount of precursor, the solvent, the source of the radiohalogen, the copper loading, and the selection of copper salts. To alleviate this challenge, several research groups have focused on improving the copper-mediated reaction. For example, the Neumaier group directed their efforts toward the azeotropic drying process, elution and phase transfer catalyst (Richarz et al. 2014; Zischler et al. 2016, 2017). Moreover, the Neumaier, Hall, and Sutherland groups independently reported novel copper salt mediators to increase the RCY of copper-mediated radiolabelling. The first two focused on fluorination, while the latter on iodination (Hoffmann et al. 2023; Sun et al. 2024; McErlain et al. 2024). Additionally, the Krasikova group contributed to the development of new elution methodologies and greener approaches for the radiosynthesis of PET tracers under copper-mediated conditions (Antuganov et al. 2019; Orlovskaya et al. 2020). Other groups, such as Sanford’s, have focused on applying new technologies to radiochemistry, including the high-throughput experimentation (HTE) to accelerate the discovery and optimization of radiochemical reactions (Orlovskaya et al. 2020). The same group also proposed an elegant alternative to streamline access to boronate precursors, complementing the well-established Miyaura Borylation (Ishiyama et al. 1995). They developed a sequential iridium/copper-mediated process for the meta-selective C − H radiofluorination of (hetero)arene substrates (Wright et al. 2021). On the other hand, the groups of Soobin, Feng, and Zeng developed different metal-catalyzed defluoroborylation of fluoroarenes, using cobalt, iron and chromium, respectively. These are powerful reactions that provide easy access to precursors for radiolabelling (Lim et al. 2018; Sun et al. 2021; Liu et al. 2024). As for radiometals and their use in the radiolabelling of PARP inhibitors, there are fewer advancements in terms of new methodologies. However, we can certainly summarize valuable insights from the publications cited here. The addition of the chelator mojety to the PARPs scaffold might impact on aspects such as the binding affinity constant (kD), specificity and biodistribution, making it crucial to determine the target affinity and specificity of the modified compound. Regarding the in vitro cells experiments, the probe’s internalization should be assessed, as the nuclear localization of the PARP enzyme. Another challenging aspect to manage is the lipophilicity of PARPi bearing chelators, as it is crucial to balance the cell membrane crossing and an exceeding abdominal region accumulation due to the hepatic clearance.

In conclusion, significant progress in PARP radiolabelling has been made in PARP radiolabelling over the past decade, with various approaches ranging from the use of prosthetic groups to introduce radioactivity, to the development of radioisotopologues. Moreover, it is interesting to see how the field has expanded to include radiometals in recent years, presenting new challenges from both a chemical and biological perspective. Overall, PARP imaging and therapy have the potential to make a meaningful impact at the (pre)clinical level and has an emerging interest for imaging in the clinical ground.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from Grant from Fondazione Ricerca Molinette.

Author contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript. GD and RR conceptualize the research, search and select the literature sources, write and review the draft. CR and RRA did the figures. SM review the draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The present work has been developed and funded by a Grant from Fondazione Ricerca Molinette FRM/RSE2024/SM.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable for raw data, all the references are cited below.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rebecca Rizzo and Gianluca Destro have contributed equally to the work.

References

- Adam MJ, Wilbur DS. Radiohalogens for imaging and therapy. Chem Soc Rev. 2005;34:153–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajenjo J, Destro G, Cornelissen B, Gouverneur V. Correction to: Closing the gap between 19F and 18F chemistry (EJNMMI Radiopharmacy and Chemistry, (2021), 6, 1, (33), 10.1186/s41181-021-00143-y). EJNMMI Radiopharm Chem. 2022;7:1–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alauddin MM. Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging with 18F-based radiotracers. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;2:55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhmoud JF, Woolley JF, Al Moustafa AE, Malki MI. DNA damage/repair management in cancers. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Andersen TL, Friis SD, Audrain H, Nordeman P, Antoni G, Skrydstrup T. Efficient 11C-carbonylation of isolated aryl palladium complexes for PET: application to challenging radiopharmaceutical synthesis. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:1548–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RC, Makvandi M, Xu K, Lieberman BP, Zeng C, Pryma DA, et al. Iodinated benzimidazole PARP radiotracer for evaluating PARP1/2 expression in vitro and in vivo. Nucl Med Biol. 2016;43:752–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antuganov D, Zykov M, Timofeev V, Timofeeva K, Antuganova Y, Orlovskaya V, et al. Copper-mediated radiofluorination of aryl pinacolboronate esters: a straightforward protocol by using pyridinium sulfonates. Eur J Org Chem. 2019;2019:918–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bowden GD, Chailanggar N, Pichler BJ, Maurer A. Scalable 18F processing conditions for copper-mediated radiofluorination chemistry facilitate DoE optimization studies and afford an improved synthesis of [18F]olaparib. Org Biomol Chem. 2021a;19:6995–7000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden GD, Stotz S, Kinzler J, Geibel C, Lämmerhofer M, Pichler BJ, et al. DoE optimization empowers the automated preparation of enantiomerically pure [18F]talazoparib and its in vivo evaluation as a PARP radiotracer. J Med Chem. 2021b;64:15690–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlucci G, Carney B, Brand C, Kossatz S, Irwin CP, Carlin SD, et al. Dual-modality optical/PET imaging of PARP1 in glioblastoma. Mol Imaging Biol. 2015;17:848–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney B, Carlucci G, Salinas B, Di Gialleonardo V, Kossatz S, Vansteene A, et al. Non-invasive PET imaging of PARP1 expression in glioblastoma models. Mol Imaging Biol. 2016;18:386–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney B, Kossatz S, Lok BH, Schneeberger V, Gangangari KK, Pillarsetty NVK, et al. Target engagement imaging of PARP inhibitors in small-cell lung cancer. Nat Commun. 2018;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chan CY, Chen Z, Destro G, Veal M, Lau D, O’Neill E, et al. Imaging PARP with [18F]rucaparib in pancreatic cancer models. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2022;49:3668–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CY, Chen Z, Guibbal F, Dias G, Destro G, O’Neill E, et al. [123I]CC1: a PARP-targeting, auger electron-emitting radiopharmaceutical for radionuclide therapy of cancer. J Nucl Med. 2023;64:1965–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Destro G, Guibbal F, Chan CY, Cornelissen B, Gouverneur V. Copper-mediated radiosynthesis of [18F]rucaparib. Org Lett. 2021;23:7290–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitneni SK, Reitman ZJ, Spicehandler R, Gooden DM, Yan H, Zalutsky MR. Synthesis and evaluation of radiolabeled AGI-5198 analogues as candidate radiotracers for imaging mutant IDH1 expression in tumors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2018;28:694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corson DR, MacKenzie KR, Segrè E. Possible production of radioactive isotopes of element 85. Phys Rev. 1940;57:459. [Google Scholar]

- Cortesi L, Rugo HS, Jackisch C. An overview of PARP inhibitors for the treatment of breast cancer. Target Oncol. 2021;16:255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin NJ, Szabo C. Therapeutic applications of PARP inhibitors: anticancer therapy and beyond. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34:10.1016/j.mam.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- D’Andrea AD. Mechanisms of PARP inhibitor sensitivity and resistance. DNA Repair (Amst). 2018;71:172–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das PK, Matada GSP, Pal R, Maji L, Dhiwar PS, Manjushree BV, et al. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors as anticancer agents: an outlook on clinical progress, synthetic strategies, biological activity, and structure-activity relationship. Eur J Med Chem. 2024;274: 116535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demétrio de Souza França P, Roberts S, Kossatz S, Guru N, Mason C, Zanoni DK, et al. Fluorine-18 labeled poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase1 inhibitor as a potential alternative to 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose positron emission tomography in oral cancer imaging. Nucl Med Biol. 2020;885:80–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destro G, Chen Z, Chan CY, Fraser C, Dias G, Mosley M, et al. A radioiodinated rucaparib analogue as an Auger electron emitter for cancer therapy. Nucl Med Biol. 2023;116–117: 108312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon KK, Bajrami I, Taniguchi T, Lord CJ. Synthetic lethality: the road to novel therapies for breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2016;23:T39-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donabedian PL, Kossatz S, Engelbach JA, Jannetti SA, Carney B, Young RJ, et al. Discriminating radiation injury from recurrent tumor with [18F]PARPi and amino acid PET in mouse models. EJNMMI Res. 2018;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Duatti A. Review on 99mTc radiopharmaceuticals with emphasis on new advancements. Nucl Med Biol. 2021;92:202–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubost E, McErlain H, Babin V, Sutherland A, Cailly T. Recent advances in synthetic methods for radioiodination. J Org Chem. 2020;85:8300–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckerman K, Endo A. ICRP Publication 107. Nuclear decay data for dosimetric calculations. Ann ICRP. 2008;38:9–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds CE, Makvandi M, Lieberman BP, Xu K, Zeng C, Li S, et al. [18F]FluorThanatrace uptake as a marker of PARP1 expression and activity in breast cancer. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;6:94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison PA, Olson AP, Barnhart TE, Hoffman SLV, Reilly SW, Makvandi M, et al. Improved production of 76Br, 77Br and 80mBr via CoSe cyclotron targets and vertical dry distillation. Nucl Med Biol. 2020;80–81:32–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer H, McCabe H, Lord CJ, Tutt AHJ, Johnson DA, Richardson TB, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraris DV. Evolution of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) inhibitors from concept to clinic. J Med Chem. 2010;53:4561–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrat M, Dahl K, Schou M. One-pot synthesis of 11C-labelled primary benzamides via intermediate [11C]aroyl dimethylaminopyridinium salts. Chem A Eur J. 2021;27:8689–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippi L, Urso L, Frantellizzi V, Marzo K, Marzola MC, Schillaci O, et al. Molecular imaging of PARP in cancer: state-of-the-art. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2023;23:1167–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuzuloparib LA. First approval. Drugs. 2021;81:1221–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron T, Destro G, Straathof NJW, Sap JBI, Guibbal F, Vriamont C, et al. multi-patient dose synthesis of [18F]Flumazenil via a copper-mediated 18F-fluorination. EJNMMI Radiopharm Chem. 2022;7:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gildersleeve DL, Van Dort ME, Johnson JW, Sherman PS, Wieland DM. Synthesis and evaluation of [123I]-iodo-PK11195 for mapping peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptors (omega 3) in heart. Nucl Med Biol. 1996;23:23–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guérard F, Lee YS, Baidoo K, Gestin JF, Brechbiel MW. Unexpected behavior of the heaviest halogen astatine in the nucleophilic substitution of aryliodonium salts. Chemistry. 2016;22:12332–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guibbal F, Isenegger PG, Wilson TC, Pacelli A, Mahaut D, Sap JBI, et al. Manual and automated Cu-mediated radiosynthesis of the PARP inhibitor [18F]olaparib. Nat Protoc. 2020a;15:1525–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guibbal F, Hopkins SL, Pacelli A, Isenegger PG, Mosley M, Torres JB, et al. [18F]AZD2461, an insight on difference in PARP binding profiles for DNA damage response PET imaging. Mol Imaging Biol. 2020b;22:1226–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guru N, Demétrio De Souza França P, Pirovano G, Huang C, Patel SG, Reiner T. PARPi imaging is not affected by HPV status in vitro. Mol Imaging. 2021;2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hamilton JG, Durbin PW, Parrott MW. Accumulation of astatine211 by thyroid gland in man. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1954;86:366–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassa PO, Haenni SS, Elser M, Hottiger MO. Nuclear ADP-ribosylation reactions in mammalian cells: where are we today and where are we going? Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70:789–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C, Shi H, Tan B, Jiang Z, Cao R, Zhu J, et al. Quinazoline-2,4(1 H,3 H)-dione Scaffold for development of a novel PARP-targeting PET probe for tumor imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2024;4:3840–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman SLV, Mixdorf JC, Kwon O, Johnson TR, Makvandi M, Lee H, et al. Preclinical studies of a PARP targeted, Meitner-Auger emitting, theranostic radiopharmaceutical for metastatic ovarian cancer. Nucl Med Biol. 2023;122–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann C, Kolks N, Smets D, Haseloer A, Gröner B, Urusova EA, et al. Next generation copper mediators for the efficient production of 18F-labeled aromatics. Chem A Eur J. 2023;29:e202202965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T, Hu P, Banizs AB, He J. Initial evaluation of Cu-64 labeled PARPi-DOTA PET imaging in mice with mesothelioma. Bioorganic Med Chem Lett. 2017;27:3472–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiyama T, Murata M, Miyaura N. Palladium(0)-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction of alkoxydiboron with haloarenes: a direct procedure for arylboronic esters. J Org Chem. 1995;60:7508–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jannetti SA, Carlucci G, Carney B, Kossatz S, Shenker L, Carter LM, et al. PARP-1-targeted radiotherapy in mouse models of glioblastoma. J Nucl Med. 2018;59:1225–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelinic P, Levine DA. New insights into PARP inhibitors’ effect on cell cycle and homology-directed DNA damage repair. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:1645–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keliher EJ, Reiner T, Turetsky A, Hilderbrand SA, Weissleder R, Keliher EJ, et al. High-yielding, two-step 18F labeling strategy for 18F-PARP1 inhibitors. ChemMedChem. 2011;6:424–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keliher EJ, Klubnick JA, Reiner T, Mazitschek R, Weissleder R. Efficient acid-catalyzed (18) F/(19) F fluoride exchange of BODIPY dyes. ChemMedChem. 2014;9:1368–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo Y, Kimura H, Sasaki I, Watanabe S, Ohshima Y, Yagi Y, et al. Copper-mediated radioiodination and radiobromination via aryl boronic precursor and its application to 125I/77Br–labeled prostate-specific membrane antigen imaging probes. Bioorganic Med Chem. 2022;69: 116915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubalanza K, Konecny GE. Mechanisms of PARP inhibitor resistance in ovarian cancer. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2020;32:36–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagueux-Tremblay PL, Fabrikant A, Arndtsen BA. Palladium-catalyzed carbonylation of aryl chlorides to electrophilic aroyl-DMAP salts. ACS Catal. 2018;8:5350–4. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Cen Y, Tu M, Xiang Z, Tang S, Lu W, et al. Nanoengineered gallium ion incorporated formulation for safe and efficient reversal of PARP inhibition and platinum resistance in ovarian cancer. Research. 2023;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lim S, Song D, Jeon S, Kim Y, Kim H, Lee S, et al. Cobalt-catalyzed C-F bond borylation of aryl fluorides. Org Lett. 2018;20:7249–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Luo Z, Zhao S, Luo M, Zeng X. Cr-catalyzed borylation of C(aryl)–F bonds using a terpyridine ligand. Chem Commun. 2024;60:5201–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord CJ, Ashworth A. The DNA damage response and cancer therapy. Nature. 2012;481:287–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord CJ, Ashworth A. PARP inhibitors: synthetic lethality in the clinic. Science. 2017;355:1152–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makvandi M, Xu K, Lieberman BP, Anderson RC, Effron SS, Winters HD, et al. A radiotracer strategy to quantify PARP-1 expression in vivo provides a biomarker that can enable patient selection for PARP inhibitor therapy. Cancer Res. 2016;76:4516–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateo J, Lord CJ, Serra V, Tutt A, Balmaña J, Castroviejo-Bermejo M, et al. A decade of clinical development of PARP inhibitors in perspective. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:1437–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McErlain H, Andrews MJ, Watson AJB, Pimlott SL, Sutherland A. Ligand-enabled copper-mediated radioiodination of arenes. Org Lett. 2024;26:1528–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min A, Im SA. PARP inhibitors as therapeutics: beyond modulation of PARylation. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mixdorf JC, Hoffman SLV, Aluicio-Sarduy E, Barnhart TE, Engle JW, Ellison PA. Copper-mediated radiobromination of (hetero)aryl boronic pinacol esters. J Org Chem. 2023;88:2089–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moerlein SM, Hwang DR, Welch MJ. No-carrier-added radiobromination via cuprous chloride-assisted nucleophilic aromatic bromodeiodination. Int J Rad Appl Instrum A. 1988;39:369–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossine AV, Brooks AF, Makaravage KJ, Miller JM, Ichiishi N, Sanford MS, et al. Synthesis of [18F]arenes via the copper-mediated [18F]fluorination of boronic acids. Org Lett. 2015;17:5780–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossine AV, Brooks AF, Ichiishi N, Makaravage KJ, Sanford MS, Scott PJH. Development of customized [18F]fluoride elution techniques for the enhancement of copper-mediated late-stage radiofluorination. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossine AV, Tanzey SS, Brooks AF, Makaravage KJ, Ichiishi N, Miller JM, et al. One-pot synthesis of high molar activity 6-[18F]fluoro-L-DOPA by Cu-mediated fluorination of a BPin precursor. Org Biomol Chem. 2019;17:8701–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossine AV, Tanzey SS, Brooks AF, Makaravage KJ, Ichiishi N, Miller JM, et al. Synthesis of high-molar-activity [18F]6-fluoro-l-DOPA suitable for human use via Cu-mediated fluorination of a BPin precursor. Nat Protoc. 2020;15:1742–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murai J, Huang SYN, Das BB, Renaud A, Zhang Y, Doroshow JH, et al. Differential trapping of PARP1 and PARP2 by clinical PARP inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2012;72:5588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor LO, Rulten SL, Cranston AN, Odedra R, Brown H, Jaspers JE, et al. The PARP inhibitor AZD2461 provides insights into the role of PARP3 inhibition for both synthetic lethality and tolerability with chemotherapy in preclinical models. Cancer Res. 2016;76:6084–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlovskaya V, Fedorova O, Kuznetsova O, Krasikova R. Cu-mediated radiofluorination of aryl pinacolboronate esters: alcohols as solvents with application to 6-L-[18F]FDOPA synthesis. Eur J Org Chem. 2020;2020:7079–86. [Google Scholar]

- Pamiparib MA. First approval. Drugs. 2021;81:1343–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascal JM. The comings and goings of PARP-1 in response to DNA damage. DNA Repair (Amst). 2018;71:177–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]