Abstract

The use of home dialysis (peritoneal dialysis [PD] and home hemodialysis [HHD]) is variable in high-income countries despite its known lifestyle benefits and lower costs, and is unavailable or underused in many lower-income countries, where PD could increase access to dialysis. The International Home Dialysis Consortium (IHDC) is a joint project of the ISN and the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD). The consortium has been established to address the challenges and barriers to and improve the adoption of home dialysis globally. A launch meeting was held at the World Congress of Nephrology 2024 in Buenos Aires, Argentina, focusing on 4 areas—empowering people needing dialysis, nephrology workforce education, developing workforce and resources, and integrating care and payment policies. The key statements from each group were then amalgamated to produce a manifesto that advocates for the global promotion of home dialysis (PD and HHD) to enhance patient experience, quality, and equity in kidney failure care. This manifesto will be presented to professional kidney-related societies (medical, nursing, patients, and technical) to adopt the declaration as a practical roadmap to increase home dialysis awareness and, consequently, modality selection.

The increasing availability of dialysis in many lower health care resource countries, the realization that for many people, home dialysis is preferable to in-center dialysis, and the predicted exponential growth in people requiring dialysis associated with an aging population and increasing diabetes prevalence is reinforcing the need to expand access to home dialysis globally. The use of home dialysis—PD and HHD—varies significantly across regions and income levels. As discussed in the 2023 Global Kidney Health Atlas,1 about 20% of countries, predominantly low-income countries in Africa, do not have access to PD. There is a large variation in the use of PD among high-income countries. Indeed, from 2019 to 2023, the median prevalence of people treated with PD decreased slightly.

The IHDC was established to address the challenges to adopting home dialysis and mitigate the obstacles to increasing its utilization.2 IHDC is a joint project of the ISN and the ISPD with representation on the steering committee from the International Pediatric Nephrology Association, Asian Pacific Society of Nephrology, African Association of Nephrology, Sociedad Latinoamericana de Nefrologia e Hipertension, International Society of Hemodialysis, EuroPD, Vantive Healthcare, and Fresenius Medical Care. The consortium focuses on PD and HHD while recognizing that PD is the predominant home modality and, in many parts of the world, the only home dialysis option.

A launch meeting was held at the World Congress of Nephrology 2024 in Buenos Aires, Argentina, focusing on 4 areas—empowering people needing dialysis, nephrology workforce education, developing workforce and resources, and integrating care and payment policies. The key statements from each group were then amalgamated to produce a manifesto. This manuscript presents a summary of the discussion from each theme and the manifesto.

Empowering People Needing Dialysis

Knowledge awareness remains a critical barrier to home dialysis adoption globally.3 Multiple international societies, global academic groups, and policymakers have provided guidance and action plans to advocate for chronic kidney disease education initiatives.4, 5, 6 Observational studies and randomized controlled clinical trials have confirmed that education allows patients to make informed dialysis modality choices by improving self-management skills, enhancing autonomy, reducing institutional barriers, and addressing psychosocial challenges.7,8 However, home dialysis awareness and knowledge continue to be lacking for patients and providers.9,10

Education efforts should not be limited to patients but extend to the entire circle of care, including care partners, families, and care providers (nephrologists, nurses, and allied health services). Prior education and mentorship activities have shown the potential of empowering the entire nephrology team and its impact on home dialysis adoption rates.2,11 Equally important, policy alignment with governing and funding partners are crucial system-level facilitators to empower patients’ adoption of home dialysis.4 Finally, manufacturers of supplies used for kidney replacement therapies have a direct role in curating unbiased home dialysis education materials and knowledge translation efforts. To achieve equity, a fully functioning learning system should include universal access to chronic kidney disease education.

Medical conditions (such as kidney failure) have been described as following the “inverse care law,”12 where inequitable access to education and care affects those who are the most vulnerable. Our declaration aims to ensure the fundamental rights of our patients (both adults and children) are respected and that education is the most important prerequisite to patient empowerment and equitable end-stage kidney disease care.

Collectively, the IHDC declares that equitable access to all forms of dialysis care and education is the right of our patients. Professional Societies should actively engage with patient advocates and include them in all initiatives. They can help dispel misinformation and educate other patients about the benefits and feasibility of home dialysis, engage with policymakers to remove institutional barriers, and advocate for changes in reimbursement policies. Finally, they build a network of champions within the health care system who can promote home dialysis as a viable option.

Nephrology Workforce Education

Health care providers have identified a lack of clinician education and experience as a significant barrier to home dialysis use.13 Although education and training are imperative, home dialysis provider training resources are limited, particularly in regions underpenetrated by home dialysis. One way to overcome these challenges is to establish a robust system of central hubs or reference centers, which would advance home dialysis training locally and regionally while remaining connected to a global network using a well-organized, team-based approach. The reference center would provide comprehensive education for regional nurses, physicians, technicians, social workers, and dieticians. It would also coordinate funding for workforce education and facilitate interprofessional exchange between local, regional, and global professionals. Achieving this goal involves a series of critical activities that will enhance the quality and reach of care internationally.

The first step in developing reference centers is defining criteria for attaining and maintaining reference center status. These criteria should encompass a range of factors, including but not limited to the expertise of the staff, the availability of resources, and the center's ability to provide basic and advanced home dialysis training (PD and/or HHD) suited to the local environment and resources. The criteria should also include metrics for evaluating the effectiveness of training programs and the quality of patient care provided by health care professionals and centers. By establishing these standards, we ensure that only centers that meet high-quality benchmarks will be recognized as reference centers, thereby maintaining the credibility and excellence of the program.6,14,15 An incentive program will likely be needed to encourage reference centers to maintain active participation and engagement. A team-based approach, emphasizing staff engagement and leadership opportunities for dialysis nurses and collaborative efforts from a team of clinical nephrologists and the dialysis provider, helps to maintain efficiency, fosters growth, and consistently provides high-quality clinical care in the home program.16 The development of reference centers supporting PD programs in remote geographical areas has been shown to be successful in diverse regions, including China17 and Colombia.18

Nephrology trainees demonstrate a low and moderate confidence level in the management of HHD and PD patients, respectively.10 Thus, the second step in the development of the reference center system is to develop, implement, and maintain a comprehensive core curriculum.

Finally, nurses play a pivotal role in the success of any home dialysis program and are the largest professional group responsible for providing kidney care internationally.19 Limited specialized training and education are significant challenges that prevent nurses from providing safe, quality nursing care.20,21 Developing a training platform for advanced practice nurses in nephrology should be a key part of the reference centers system. The platform should also address language barriers that may affect nurses' ability to understand training materials and clinical protocols in English. Including language support and clear resources will ensure that all advanced practice nurses can participate effectively. This platform should incorporate evidence-based strategies and best practices for managing home dialysis patients. Nurse-led clinics and advanced practice nurses have been shown to increase patient knowledge and ability for self-care in Sweden22 and achieve better clinical outcomes in general nephrology clinics.23 The training, therefore, should be designed to ensure that advanced practice nurses are well-equipped to deliver high-quality care and achieve optimal patient outcomes.

Training should be underpinned by a system of competencies and responsibilities that will differ based on local resources and health care systems.24,25 The platform should include interactive modules, simulation exercises, and assessments to enhance learning and application of skills. A critical aspect of increasing the number of PD patients is to have more professionals competent in starting the therapy. For example, having nurses and physicians trained for the aseptic insertion, care, and management of PD catheters will support PD growth.26,27

Developing Workforce, Resources and Pathways to Care

The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Home Dialysis report6 reviewed clinical evidence and agreed that everyone needing maintenance dialysis should be considered for home dialysis with individualized education, clinical assessment, and shared decision-making. The report also emphasized the importance of health care professionals' clinical experience and health system factors in the high variation in the use of home dialysis within and between countries. There is, therefore, a need for the development of a roadmap to support the creation and opening of home dialysis programs with strong clinical leadership and a trained workforce.28

To achieve this goal, an organized approach is required to identify patients progressing to end-stage kidney disease or presenting late with more urgent needs for dialysis and ensure education, assessment, and shared decision-making. It is known that even after making a choice to dialyze at home, health system or patient factors result in many patients not getting the modality of choice. The IHDC, therefore, recommends that pathways of care should be implemented in all health care settings to facilitate the successful transition of people with chronic kidney disease to home dialysis following shared decision-making. The 6-step model (identification, assessment, eligibility, offer, choice, and receipt)29 and Figure 1 should form the basis of a standardized pathway to support modality choice during both planned and unplanned dialysis start and modality transition. A set of tools respecting the different local dialysis program needs across all countries will be collated from existing resources and developed by the IHDC to support implementation. This model is ideal for implementation alongside local audit or quality improvement processes, which may be more successful in increasing home dialysis use than top-down processes.30

Figure 1.

The starting dialysis on time, at home on the right therapy (START) 6-step model for managing transition onto dialysis (adapted from reference Gomez et al.25).

An initial concept of a toolkit to support, start, and grow home dialysis programs is presented in Figure 2. Initially, this will be built as an online resource supported by mentorship through the proposed reference centers. The local patient and clinical leadership will ensure that all content is suitable for local adaptation and can be tailored to the health care system. In addition, guidance will be provided on simple quality improvement techniques to ensure standardized approaches within the home dialysis program as part of the broader kidney replacement therapy service. Centers that offer a supportive clinical environment where specific components of service organization and delivery can be effectively deployed, such as quality improvement, are more likely to facilitate home dialysis uptake.28

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework for online resources to assist in establishing and growing home dialysis programs.

Integrating Care and Payment Policies

The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Controversies Conference on Home Dialysis underscored the importance of policy alignment, fiscal resources, organizational structure, provider incentives, and accountability in expanding the use of home dialysis.6 The group identified the following 4 strategic areas concerning policies for increasing home dialysis utilization: (i) improving the cost-effectiveness of home dialysis through rigorous health technology assessment, (2) establishing a framework for home dialysis advocacy, (iii) ensuring an equitable incentivization policy, and (iv) outlining an acceptable standard for the delivery of quality care for home dialysis in different resource settings31,32

Establishing the Cost-Effectiveness of Home Dialysis Through Health Technology Assessment

Both Hong Kong and Thailand established a PD-first policy in 1985 and 2008, respectively, driven by the desire to increase access to kidney replacement therapy for the growing number of people with kidney failure while maintaining cost-effectiveness, leading to a substantial growth in the number of patients on dialysis.33, 34, 35 An alternative approach is a PD-preferred policy, adopted by Mexico and Guatemala.36 The choice of policy should be personalized to each country’s needs, resources, preferences, and political appetite. In many countries, a home dialysis–preferred policy will likely be more palatable over a more paternalistic home dialysis-first initiative. Nonetheless, vital to a home dialysis-centric policy is demonstrating the cost-effectiveness of home dialysis over in-center hemodialysis37 considering the peculiarities of health financing in individual settings. In Figure 3, we summarize the key considerations for a home dialysis–preferred policy and outline the objective of addressing each component.

Figure 3.

Key considerations for a home dialysis-preferred policy.

Advocating for Home Dialysis

It is important to establish a framework for advocating for home dialysis within each jurisdiction. Identifying the institution that will take ownership of pushing the home dialysis agenda is key to ensuring a sustainable and effective advocacy effort (Figure 4). The advocacy blueprint should identify system and individual barriers to adopting home dialysis, and strategies should be built to address and overcome these obstacles to home-based treatment. The Levesque’s conceptual framework of access to health care that addresses the dimensions of approachability, acceptability, availability or accommodation, affordability, and appropriateness of health systems and the abilities of individuals and populations to perceive, seek, reach, pay, and engage in health care can be considered in developing advocacy efforts.38

Figure 4.

Framework for advocating for home dialysis.

Incentivization for Home Dialysis

Incentivization is essential for the expansion of home dialysis.39, 40, 41, 42 The disparity in physician payments for in-center hemodialysis and PD in some jurisdictions has been recognized as a critical factor in low PD utilization in many countries, and removing financial disincentive is an important initiative that can be quickly addressed.43 Removing disincentives for home dialysis should be implemented for all vested parties and should go beyond just fiscal “carrots” to include attractiveness and convenience for all stakeholders. As an example, akin to having nursing rooms for mothers in shopping malls, the availability of dedicated areas for PD exchanges in these settings will enhance the integration of patients into society. The approach to home dialysis incentivization should not be to penalize in-center hemodialysis but to capitalize on the cost savings derived from home-based therapies and ensure that financial incentives and reimbursement are equitable to that of in-center hemodialysis, resulting in a greater gain from home dialysis. In addition, to ensure the sustainable and cost-effective supply of home dialysis consumables, the IHDC recognizes the importance of engaging the industry in public-private partnership programs. Reducing import tariffs and barriers while improving country infrastructure support for the shipment and storage of products could translate into cost-saving to patients, payers, and health systems; and improve the overall cost-effectiveness of home dialysis.

Standards of Home Dialysis Care and Monitoring of Outcomes

The IHDC seeks to provide adaptable guidelines that align with local health care systems. The proportion of people with kidney failure adopting home dialysis in each jurisdiction should be determined by its ability to deliver kidney replacement therapy equitably without compromising the standard of care. Quality standards for the delivery of home dialysis should be modeled on the ISN Kidney Failure Strategy Dialysis Framework,31,32 designed to support the growth of safe and effective dialysis in low-resource settings. The outcomes of home dialysis that should be monitored and used to guide further health policies have been articulated within the ISN framework and should be adapted and personalized to the needs of each country. It should be clarified, though, that the ISN framework focuses on PD as the home dialysis modality. HHD is a greater challenge worldwide in terms of implementing and ensuring quality standards.

Next Steps: Manifesto

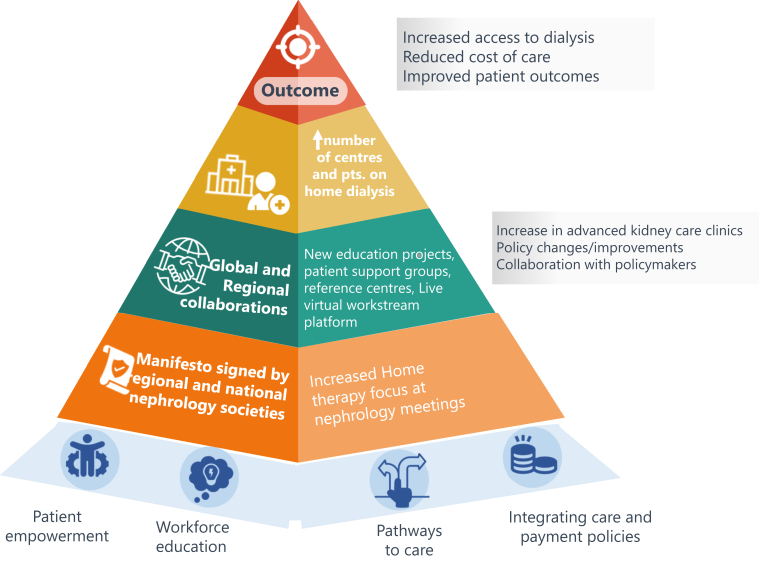

The IHDC's efforts highlight the critical need to develop implementation approaches to expand home dialysis access worldwide. The first step has been to produce a manifesto, which has been endorsed by ISN and ISPD (Table 1 and at https://www.theisn.org/initiatives/ihdc/#manifesto). This manifesto will be presented to professional kidney-related societies (medical, nursing, patients, and technical) to adopt the declaration as a roadmap to increase home dialysis awareness and, consequently, modality selection. This should enable each society to actively accommodate the home dialysis care agenda according to local needs, context, and economic and cultural realities. IHDC will aim to engage with local stakeholders to develop locally appropriate mechanisms to empower patients and health care providers by promoting education, fostering policy alignment, and creating resources. To this end, a meeting was coordinated with Middle East representatives after the ISPD meeting in Dubai in September 2024, and a meeting is being organized with South Asian stakeholders during the World Congress of Nephrology (WCN) meeting in New Delhi in February 2025. Further meetings will be organized in the regions of 2026 WCN (Japan/North East Asia) and ISPD (Africa) meetings. The vision and long-term goal of the IHDC is an increase in the number of centers delivering and patients receiving home dialysis worldwide. This can be monitored through national renal registries and globally through the Global Kidney Healthcare Atlas. However, as outlined, there are many steps required to enable this increase to occur. In Figure 5, we show some of the measures that can be monitored to determine the impact of each workstream in different regions. Meanwhile, the manifesto serves as a roadmap to ensure equitable, effective kidney care, addressing global disparities in treatment availability.

Table 1.

International Home Dialysis Consortium manifesto

| All forms of kidney replacement therapy are potentially lifesaving, and a key priority for all countries should be to ensure that kidney replacement therapy is available and affordable for everyone with kidney failure. However, to those who already have access to kidney replacement therapy, home dialysis has special advantages. Providing home dialysis (peritoneal dialysis and home hemodialysis) holds the promise of enhancing patient experience, quality, and equity in kidney failure care by allowing wider global access to kidney replacement therapies. |

| This manifesto is a public declaration advocating for the promotion of home dialysis globally by: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 5.

Framework for measuring outcomes from the International Home Dialysis Consortium.

Disclosure

EAB is the immediate past president of the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis; and receives speaker fees from Baxter Healthcare and Fresenius Medical Care, and consulting fees from Fresenius Medical Care. VJ reports receiving consulting fees paid to his institution from Bayer, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Biocryst, Vera, Visterra, Otsuka, Novartis, Astra Zeneca, Chinook, Biocryst, and Alpine. SB has received speaker honoraria from Baxter and Fresenius Medical Care, and travel grant as speaker from Baxter. CTC has received investigator grants from Medtronic and Red Sense. SD is vice-president of EuroPD and trustee of Kidney Research UK. AF receives speaker fees from Baxter Healthcare. AL reports employment with The Kidney & Transplant Practice Pte Ltd; consultancy for Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Baxter Healthcare, Bayer AG, BioCryst Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Chinook Therapeutics, Dimerix Limited, Eledon Pharmaceuticals, Fresenius Medical Care, George Clinical, GlaxoSmithKline, Kira Pharmaceuticals, Prokidney, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Vera Therapeutics, Visterra Inc, and Zai Lab Co. Ltd; has received speakers' honorarium from AstraZeneca, Baxter Healthcare, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Chinook Therapeutics, Fresenius Medical Care, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, and Vera Therapeutics; and has served as a member of Data Safety and Monitoring Committee for Dimerix Limited and Zai Lab Co. Ltd. MM reports receiving consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, and Boehringer Ingelheim; research support from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Renal Research Institute, and Tricida; speaker honoraria and travel support from AstraZeneca; and funding for expert testimony for AstraZeneca, Bayer, and Boehringer Ingelheim. RM is president of International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis and is editor-in-chief for Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. SM participates in an advisory board for Fresenius Medical Care. PR is an employee of and has stocks in Baxter Healthcare. AS is on the speaker’s bureau for Baxter Healthcare. BS is an employee of Fresenius Medical Care and has stock options in Unicycive. CPS received consulting fees from Chiesi, Baxter, StadaPharma, and Bioporto; lecture honorarium and traveling support from Chiesi; and research funding from Invizius and Baxter; and received a payment for participation in a Data Safety Monitoring Board funded by the German Research Organization DFG. SCWT received lecture honoraria from Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Baxter, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novartis; participates on advisory boards of Boehringer Ingelheim and Novartis; and is immediate past President of Asian Pacific Society of Nephrology. All the other authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Dr Priti Meena for designing Figure 5.

References

- 1.Bello A.K., Okpechi I.G., Levin A., et al. ISN–Global Kidney Health Atlas: a report by the international society of nephrology: an assessment of global kidney health care status focussing on capacity, availability, accessibility, affordability and outcomes of kidney disease. International Society of Nephrology. Published 2023. https://www.theisn.org/initiatives/global-kidney-health-atlas/

- 2.Brown E.A., Jha V., Steering Committee, on behalf of the Steering Committee Introducing the international home dialysis consortium. Kidney Int Rep. 2023;8:1277–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2023.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan C.T., Wallace E., Golper T.A., et al. Exploring barriers and potential solutions in home dialysis: an NKF-KDOQI conference outcomes report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;73:363–371. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watnick S., Blake P.G., Mehrotra R., et al. System-level strategies to improve home dialysis: policy levers and quality initiatives. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023;18:1616–1625. doi: 10.2215/CJN.0000000000000299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan C.T., Blankestijn P.J., Dember L.M., et al. Dialysis initiation, modality choice, access, and prescription: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2019;96:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2019.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perl J., Brown E.A., Chan C.T., et al. Home dialysis: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2023;103:842–858. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2023.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rioux J.P., Cheema H., Bargman J.M., Watson D., Chan C.T. Effect of an in-hospital chronic kidney disease education program among patients with unplanned urgent-start dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:799–804. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07090810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manns B.J., Taub K., Vanderstraeten C., et al. The impact of education on chronic kidney disease patients’ plans to initiate dialysis with self-care dialysis: a randomized trial. Kidney Int. 2005;68:1777–1783. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan C.T., Collins K., Ditschman E.P., et al. Overcoming barriers for uptake and continued use of home dialysis: an NKF-KDOQI conference report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75:926–934. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta N., Taber-Hight E.B., Miller B.W. Perceptions of home dialysis training and experience among US nephrology fellows. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;77:713–718. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abra G., Poyan Mehr A., Chan C.T., Schiller B. The implementation of a virtual home dialysis mentoring program for nephrologists. Kidney360. 2022;3:734–736. doi: 10.34067/KID.0000202022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hart J.T. The inverse care law. Lancet. 1971;1:405–412. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)92410-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reddy Y.N.V., Kearney M.D., Ward M., et al. Identifying major barriers to home dialysis (the IM-HOME study): findings from a national survey of patients, care partners, and providers. Am J Kidney Dis. 2024;84:567–581. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2024.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abra G.E., Weinhandl E.D., Hussein W.F. Setting up home dialysis programs: now and in the future. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023;18:1490–1496. doi: 10.2215/CJN.0000000000000284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szeto C.C., Lo W.K., Li P.K.T. Clinical practice guidelines for the provision of renal service in Hong Kong: peritoneal dialysis. Nephrology (Carlton) 2019;24(suppl 1):27–40. doi: 10.1111/nep.13505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmad M., Wallace E.L., Jain G. Setting up and expanding a home dialysis program: is there a recipe for success? Kidney360. 2020;1:569–579. doi: 10.34067/KID.0000662019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang Z., Yu X. Advancing the use and quality of peritoneal dialysis by developing a peritoneal dialysis satellite center program. Perit Dial Int. 2011;31:121–126. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2010.00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanabria M., Devia M., Hernández G., et al. Local investigators in study. Outcomes of a peritoneal dialysis program in remote communities within Colombia. Perit Dial Int. 2015;35:52–61. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2012.00301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker R.C., Bennett P.N. The international society of nephrology and the renal society of Australasia: towards a global impact. Renal Society Australasia Journal. 2020;16:6–7. doi: 10.33235/rsaj.16.1.6-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett P.N., Eilers D., Yang F., Rabetoy C.P. Perceptions and practices of nephrology nurses working in home dialysis: an international survey. Nephrol Nurs J. 2019;46:485–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett P.N., Walker R.C., Trask M., et al. The International Society of Nephrology Nurse Working Group: engaging nephrology nurses globally. Kidney Int Rep. 2019;4:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2018.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pagels A.A., Wång M., Wengström Y. The impact of a nurse-led clinic on self-care ability, disease-specific knowledge, and home dialysis modality. Nephrol Nurs J. 2008;35:242–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCrory G., Patton D., Moore Z., O’Connor T., Nugent L. The impact of advanced nurse practitioners on patient outcomes in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. J Ren Care. 2018;44:197–209. doi: 10.1111/jorc.12245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Canga-Armayor N. Academic training of nurses developing advanced practice roles. Enferm Intensiva (Engl Educ) 2024;35:e41–e48. doi: 10.1016/j.enfie.2024.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gomez N.J., Castner D., Hain D.J., Latham C., Cahill M. Nephrology nursing scope and standards of practice: take pride in practice. Nephrol Nurs J. 2022;49:313–327. doi: 10.37526/1526-744X.2022.49.4.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bowes E. A new role for nurses: PD catheter insertion under local anesthesia. J Ren Nurs. 2010;2:4. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowes E., Ansari B., Cairns H. Nurse-performed local-anesthetic insertions of PD catheters: one unit’s experience. Perit Dial Int. 2016;36:589–591. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2016.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Damery S., Lambie M., Williams I., et al. Centre variation in home dialysis uptake: a survey of kidney centre practice in relation to home dialysis organisation and delivery in England. Perit Dial Int. 2024;44:265–274. doi: 10.1177/08968608241232200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quinn R.R., Mohamed F., Pauly R., et al. Starting dialysis on Time, at home on the right therapy (START): description of an intervention to increase the safe and effective use of peritoneal dialysis. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2021;8 doi: 10.1177/20543581211003764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manns B.J., Garg A.X., Sood M.M., et al. Multifaceted intervention to increase the use of home dialysis: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;17:535–545. doi: 10.2215/CJN.13191021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris D.C.H., Davies S.J., Finkelstein F.O., Jha V. The second Global Kidney Health Summit outputs: developing a strategic plan to increase access to integrated end-stage kidney disease care worldwide. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 2020;10:e1–e2. doi: 10.1016/j.kisu.2019.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davies S.J., Naicker S., Liew A., et al. The international society of nephrology collaborative quality framework to support safe and effective dialysis provision in resource-challenged settings. Kidney Int Rep. 2025;10:663–672. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2024.11.1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li P.K., Lu W., Mak S.K., et al. Peritoneal dialysis first policy in Hong Kong for 35 years: global impact. Nephrology (Carlton) 2022;27:787–794. doi: 10.1111/nep.14042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chuengsaman P., Kasemsup V. PD first policy: Thailand’s response to the challenge of meeting the needs of patients with end-stage renal disease. Semin Nephrol. 2017;37:287–295. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2017.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chan J.Y.H., Cheng Y.L., Yuen S.K., et al. The Hong Kong Renal Registry: a recent update. HK Med J. 2024;30:332–336. doi: 10.12809/hkmj2411504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu F.X., Gao X., Inglese G., Chuengsaman P., Pecoits-Filho R., Yu A. A global overview of the impact of peritoneal dialysis first or favored policies: an opinion. Perit Dial Int. 2015;35:406–420. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2013.00204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Afiatin K.L.C., Kristin E., Masytoh L.S., et al. Economic evaluation of policy options for dialysis in end-stage renal disease patients under the universal health coverage in Indonesia. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cu A., Meister S., Lefebvre B., Ridde V. Assessing healthcare access using the Levesque’s conceptual framework- a scoping review. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20:116. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01416-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manns B., Agar J.W.M., Biyani M., et al. Can economic incentives increase the use of home dialysis? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019;34:731–741. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfy223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flanagin E.P., Chivate Y., Weiner D.E. Home dialysis in the United States: a roadmap for increasing peritoneal dialysis utilization. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75:413–416. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koukounas K.G., Kim D., Patzer R.E., et al. Pay-for-performance incentives for home dialysis use and kidney transplant. JAMA Health Forum. 2024;5:6–9. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2024.2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ji Y., Einav L., Mahoney N., Finkelstein A. Financial incentives to facilities and clinicians treating patients with end-stage kidney disease and use of home dialysis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3 doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.3503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mendelssohn D.C., Langlois N., Blake P.G. Peritoneal dialysis in Ontario: a natural experiment in physician reimbursement methodology. Perit Dial Int. 2004;24:531–537. doi: 10.1177/089686080402400611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]