Abstract

Background

This study aims to evaluate the clinical characteristics of COPD patients with AATD according to their age at diagnosis.

Methods

Data was obtained from the European Alpha-1 Research Collaboration (EARCO) registry, an international prospective cohort study. AATD patients with COPD registered between February 2020 and October 2024 were analysed. Clinical charateristics were compared between groups, stratified by age of AATD diagnosis as follows; <45, 45–65 and ≥65 years. A multivariable logistic regression model explored factors associated with age at diagnosis.

Results

A total of 1,565 AATD-COPD patients were included, with 18.2% receiving an AATD diagnosis at age ≥ 65. In univariate comparisons according to diagnosis age revealed that the prevalence of patients with Pi*ZZ mutation was lower in the ≥ 65 age group (47.1%) compared to the 45–65 (65.5%) and < 45 (78.5%) age groups. In contrast, the prevalence of Pi*SZ and Pi*SS were higher in the ≥ 65 group compared to the younger age groups. The proportion of never-smokers was highest in the ≥ 65 group (39.5%), whereas only 15.3% of patients under 45 were never-smokers. Multivariate analysis showed that; compared to never-smokers, former smoking (OR: 0.08; 95% CI: 0.03–0.23) and current smoking (OR: 0.43; 95% CI: 0.27–0.70) were negatively associated with a diagnosis at age ≥ 65 in all sample. Compared to the Pi*ZZ genotype, among all sample, Pi*SS was associated with more than a 3-fold increased likelihood of diagnosis at age ≥ 65 and when considering only index cases Pi*SZ was associated with diagnosis age of ≥ 65 (OR: 2.01, 95%CI: 1.01–4.04). Among patients with the Pi*ZZ, current smoking was negatively associated (OR:0.24,95%CI: 0.13–0.47) with a diagnosis at age ≥ 65, whereas higher FEV1% and serum AAT levels were positively associated with later diagnosis.

Conclusion

Patients diagnosed at an older age had lower tobacco exposure and less severe disease. This suggests that subclinical symptoms may contribute to delays in diagnosis, as COPD features can be subtle or under-recognised until later in life. Our findings highlight the importance of considering AATD in all COPD patients, regardless of age, to avoid missed or delayed diagnoses.

Keywords: AATD, COPD, Elderly, Diagnosis age

Introduction

Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (AATD) is typically associated with younger patients, particularly those with lower smoking exposure or a family history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and emphysema. Consequently, AATD diagnoses in older patients presenting with COPD symptoms may be overlooked. Awareness of AATD remains limited, contributing to underdiagnosis [1]. While some countries have attempted population-based newborn screening programs [2], targeted screening approaches may be more effective given the low prevalence of AATD and the fact that not all affected individuals develop clinical disease. However, even within targeted screening programs, underdiagnosis and underestimation remain significant challenges [3, 4]. Despite guidelines recommending that all COPD patients be tested for AATD, younger COPD patients continue to be tested more frequently, while older patients remain underdiagnosed. In fact, being under 55 years old (OR 2.4, p < 0.001) has been identified as a significant factor associated with AATD testing in COPD patients [5]. Similarly, Soriano et al. analysed UK COPD patient data and found that AATD testing was most commonly performed in those aged 45–65 years, while it was least frequent among those aged 65 years and older [6]. AATD leads to early onset emphysema, despite often modest tobacco exposure, often one or two decades earlier than smokers with normal AAT levels. AATD has been associated with reduced life expectancy compared to never-smokers [7, 8]. Symptomatic AATD has been associated with a marked reduction in life expectancy, with a cumulative survival probability of 52% by age 50 and 16% by age 60 [7]. However, recent studies following Pi*ZZ and Pi*SZ individuals up to ages 43–45 years have shown no difference in survival compared to the Swedish general population [9].

Symptomatic AATD patients who live beyond the age of 60 tend to have fewer symptoms, experience fewer acute exacerbations, and report better health-related quality of life (HRQoL) scores than younger individuals with AATD, which may contribute to longer diagnostic delays [10]. Delayed diagnosis of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency has been reported to be associated with worsening of COPD-related symptoms and functional status and a tendency for worsening airflow obstruction [11]. The first study in the literature to examine the impact of diagnostic delay on survival found that longer diagnostic delays were significantly associated with worse overall survival and transplant-free survival, independent of known risk factors such as age, body mass index (BMI), impaired pulmonary function, smoking status, and prolonged oxygen therapy [12].

Consequently, increased efforts are needed to improve screening and ensure early diagnosis of AATD, particularly in relevant patient groups such as those with COPD [11, 12]. Given the limited evidence on the impact and determinants of age at diagnosis in AATD-COPD patients, our study aimed to assess the clinical characteristics of AATD-COPD patients according to their age at diagnosis, using a large, well-characterised cohort from the European Alpha-1 Research Collaboration (EARCO) registry.

Methods

Data was obtained from EARCO registry, an international prospective cohort study. EARCO is a clinical research collaboration of the European Respiratory Society (ERS) that aims to answer fundamental questions about the epidemiology, genetics, pathophysiology, clinical treatment and prognosis of AATD-related lung diseases. The registry was originally designed as a European observational study, but has now expanded beyond European borders to become a global registry. Individuals diagnosed with severe AATD, regardless of clinical features or severity, are eligible to participate in this observational study. The inclusion criteria were: Individuals diagnosed with AATD; AAT serum levels < 11 µM (50 mg/dL) and/or deficiency defined as heterozygous or homozygous combinations of proteinase inhibitor genotypes PI*ZZ, PI*SZ and other rare functionally deficient variants. The structure, objectives, populations and measurements in EARCO were previously described in detail [13, 14]. The EARCO registry protocol was registered in www.clinicaltrials.gov (ID: NCT04180319, posted registration date: 27th November 2019), and is hosted in www.earco.org. The study protocol received central ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Barcelona, Spain (PR(AG)480/2018) and was subsequently approved by all participating centres. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

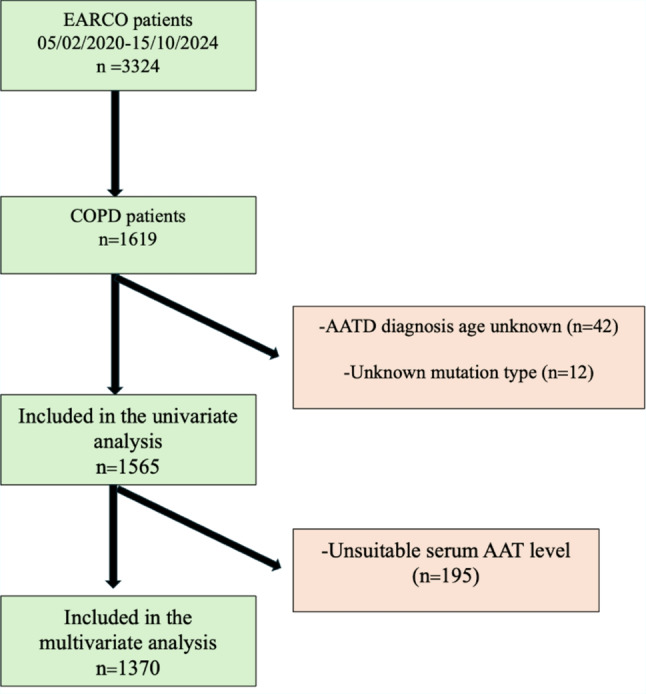

For this study, participants registered to EARCO between February 2020 and October 2024 were included. Out of total of 3324 patients with AATD, 1308 were identified as having COPD. A further 311 patients with forced expiratory volume in first second (FEV1)/ forced vital capacity (FVC) < 0.7 and coded as emphysema and/or chronic bronchitis were also included. Among all 1619 patients, those with missing data for age at time of AATD diagnosis (n = 42) and/or AAT genotype/phenotype (n = 12) were excluded. The final dataset consisted of 1565 patients (Fig. 1). Patients were grouped according to their age at AATD diagnosis in three groups; <45, 45–65 and ≥65 years for comparisons regarding their demographic and clinical characteristics. Diagnostic delay was defined as the time between COPD and AATD diagnosis. The power of the study was calculated for 1565 patients with AATD-COPD to be 95% when the lowest effect size level (0.10) was accepted in the analysis performed with G*POWER 3.1.9.7 software.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of inclusion and exclusion

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS (IBM Corp. Released 2023. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0.2.0 Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) software. Baseline characteristics of patients were assessed using means and standard deviations for continuous variables. Frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical variables. The distribution characteristics of continuous variables were evaluated by Shapiro Wilk test, and since none of them showed normal distribution, Kruskal Wallis test was used in these comparisons with age at diagnosis in 3 groups. Chi-square test was used in the comparison of age groups and categorical variables. A logistic regression model was created to determine the factors associated with older age at AATD diagnosis (≥65 years vs. < 65). The independent variables of the model were selected among the univariate analysis that showed statistical significance as well as clinical relevance. These included pulmonary function parameters (FEV1%, carbon monoxide transfer coefficient (KCO) %), respiratory symptom burden and quality of life (COPD-assessment test (CAT), Euro QoL 5 dimensions questionnaire (EQ-5D)), serum AAT level, genotype and smoking status. All assumptions of statistical models were tested and deemed satisfactory.

Results

In total, 1,565 AATD patients with COPD were included. 18.3% of patients were diagnosed at age 65 or older. The mean duration of diagnostic delay was longest in the ≥ 65 group and shortest in the < 45 group (5.61 years vs. 3.16 years).

Regarding smoking history, 6.8% of patients were current smokers, 68.3% were former smokers, and 24.9% were never-smokers. The proportion of never-smokers was highest (39.5%) among those diagnosed at age ≥ 65 and lowest (15.3%) in those diagnosed before age 45. The prevalence of the Pi*ZZ genotype was lowest in the ≥ 65 group (47.2%) compared to the 45–65 (65.5%) and < 45 (78.5%) groups, whereas the Pi*SZ and Pi*SS genotypes were more common in the ≥ 65 group than in younger age groups (Table 1). Detailed baseline characteristics of the cohort are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical and functional characteristics of AATD-COPD patients according to their diagnosis age groups

|

Total patients with AATD-COPD ( n :1565) |

Diagnosed at age < 45 ( n : 451) |

Diagnosed at age 45–65 ( n :828) |

Diagnosed at age ≥ 65 ( n :286) |

p | |

| Current age | 60.1 ± 11.1 | 50.0 ± 9.86* | 61.0 ± 7.53* | 73. 3 ± 4.97* | < 0.001 |

| Current age group | < 0.001 | ||||

| < 65 | 975 (62.3) | 413 (91.6) | 562 (67.9) | 0 | |

| 65 and over | 590 (37.7) | 38 (8.4) | 266 (32.1) | 286 (100) | |

| Age at COPD diagnosis age | 52.0 ± 12.4 | 39.9 ± 8.54* | 52.6 ± 8.04* | 67.9 ± 7.36* | < 0.001 |

|

Duration of diagnostic delay (n = 491) (age of diagnoseAATD-age of COPD diagnosis) |

4.84 ± 6.61 | 3.16 ± 4.54* | 5.17 ± 7.11 | 5.61 ± 6.84 | < 0.001 |

| Age of onset of symptoms | 47.5 ± 13.9 | 36.0 ± 9.34* | 48.3 ± 10.8* | 63.1 ± 12.0* | < 0.001 |

| Sex | 0.694 | ||||

| Female | 644 (41.2) | 180 (39.9) | 349 (42.1) | 115 (40.2) | |

| Male | 921 (58.8) | 271 (60.1) | 479 (57.9) | 171 (59.8) | |

| BMI | 25.9 ± 5.01 | 25.5 ± 5.08* | 26.1 ± 5.08 | 26.5 ± 5.01* | 0.023 |

| AATD testing reason | 0.001 | ||||

| Index case | 1370 (87.5) | 373 (82.7) | 743 (89.7) | 254 (88.8) | |

| Family screening | 195 (12.5) | 78 (17.3) | 85 (10.3) | 32 (11.2) | |

| Smoking status | < 0.001 | ||||

| Current smoker | 107 (6.8) | 39 (8.6) | 53 (6.4) | 15 (5.2) | |

| Former smoker | 1069 (68.3) | 343 (76.1) | 568 (68.6) | 158 (55.2) | |

| Never smoker | 389 (24.9) | 69 (15.3) | 207 (25.0) | 113 (39.5) | |

| Smoking pack/years | 24.7 ± 20.6 | 17.8 ± 11.5* | 25.7 ± 20.2* | 36.7 ± 29.9* | < 0.001 |

| Education level | 0.001 | ||||

| Lower than university | 898 (57.4) | 286 (63.4) | 457 (55.2) | 155 (54.2) | |

| University and higher | 371 (23.7) | 108 (23.9) | 204 (24.6) | 59 (20.6) | |

| Unknown | 296 (18.9) | 57 (12.6) | 167 (20.2) | 72 (25.2) | |

| Occupation | < 0.001 | ||||

| Actively working | 638 (41.1) | 271 (60.2) | 350 (42.9) | 17 (5.9) | |

| Others (retired/unemployed/other) | 913 (58.9) | 179 (39.8) | 465 (57.1) | 269 (94.1) | |

| Presence of any comorbidity | 707 (46.8) | 153 (35.7) | 375 (46.6) | 179 (64.4) | < 0.001 |

| Presence of asthma | 178 (11.4) | 60 (13.3) | 86 (10.4) | 32 (11.2) | 0.290 |

| Presence of bronchiectasis | 291 (18.6) | 65 (14.4) | 162 (19.6) | 64 (22.4) | 0.015 |

| Presence of cardiovascular diseases | 158 (10.4) | 29 (6.7) | 81 (10.1) | 48 (17.3) | < 0.001 |

| Presence of liver disease | 203 (14.8) | 47 (12.7) | 120 (16.5) | 36 (13.3) | 0.343 |

| Charlson index (age corrected) | 3.98 ± 1.80 | 2.74 ± 1.38* | 4.11 ± 1.52* | 5.65 ± 1.68* | < 0.001 |

| Genotype | < 0.001 | ||||

| Pi*ZZ | 1032 (65.9) | 354 (78.5) | 543 (65.6) | 135 (47.2) | |

| Pi*SZ | 253 (16.2) | 33 (7.3) | 141 (17.0) | 79 (27.6) | |

| Pi*SS | 76 (4.9) | 5 (1.1) | 31 (3.7) | 40 (14.0) | |

| Other (Rare mutations) | 204 (13.0) | 59 (13.1) | 113 (13.6) | 32 (11.2) | |

|

Total AATD-COPD (n:1565) |

Diagnosed at age < 45 (n: 451) |

Diagnosed at age 45–65 (n:828) |

Diagnosed at age 65 and over (n:286) |

p | |

| BODE index | 2.53 ± 2.08 | 2.75 ± 2.12 | 2.55 ± 2.05 | 2.15 ± 2.05* | 0.003 |

| EQ-5D index | 0.79 ± 0.23 | 0.77 ± 0.23* | 0.79 ± 0.24 | 0.83 ± 0.19* | 0.021 |

| CAT score | 14.7 ± 8.86 | 15.6 ± 8.91 | 14.9 ± 8.89 | 12.7 ± 8.43* | 0.007 |

| GOLD category | 0.808 | ||||

| A | 353 (22.6) | 105 (23.3) | 183 (22.1) | 65 (22.7) | |

| B | 838 (53.5) | 232 (51.4) | 455 (55.0) | 151 (52.8) | |

| E | 374 (23.9) | 114 (25.3) | 190 (22.9) | 70 (24.5) | |

| mMRC dyspnea score | 0.631 | ||||

| < 2 (0, 1) | 715 (45.7) | 211 (46.8) | 369 (44.6) | 135 (47.4) | |

| 2 and over (2,3,4) | 848 (54.3) | 240 (53.2) | 458 (55.4) | 150 (52.6) | |

| Ambulatory exacerbations | 0.136 | ||||

| 0 | 1019 (65.7) | 291 (65.1) | 527 (64.4) | 201 (70.3) | |

| 1 | 303 (19.5) | 79 (17.7) | 174 (21.3) | 50 (17.5) | |

| 2 and over | 229 (14.8) | 77 (17.2) | 117 (14.3) | 35 (12.2) | |

| Emergency department admission | 0.827 | ||||

| 0 | 1366 (90.7) | 390 (90.9) | 722 (90.4) | 254 (91.4) | |

| 1 | 98 (6.5) | 30 (7.0) | 52 (6.5) | 16 (5.8) | |

| 2 | 42 (2.8) | 9 (2.1) | 25 (3.1) | 8 (2.9) | |

| Hospitalization number | 0.152 | ||||

| 0 | 1390 (89.7) | 399 (89.1) | 743 (90.9) | 248 (87.0) | |

| 1 and over | 160 (10.3) | 49 (10.9) | 74 (9.1) | 37 (13.0) | |

| Post-bronchodilator | |||||

| FEV1% | 56.5 ± 24.3 | 51.3 ± 23.6* | 56.2 ± 23.7* | 64.8 ± 24.8* | < 0.001 |

| FVC % | 89.5 ± 24.7 | 86.7 ± 23.9 | 89.2 ± 24.4 | 96.4 ± 25.7* | 0.003 |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.48 ± 0.14 | 0.46 ± 0.15* | 0.49 ± 0.14* | 0.51 ± 0.13* | 0.002 |

| KCO% | 62.6 ± 25.8 | 60.4 ± 21.3 | 61.9 ± 22.1 | 67.8 ± 25.6* | 0.001 |

| DLCO% | 55.6 ± 22.7 | 55.7 ± 23.7 | 54.4 ± 22.2 | 58.5 ± 22.7 | 0.040 |

| LTOT, yes | 258 (16.7) | 75 (16.8) | 138 (16.9) | 45 (15.7) | 0.730 |

| Augmentation therapy, yes | 574 (37.1) | 196 (43.8) | 308 (37.8) | 70 (24.5) | < 0.001 |

| Lung transplantation, yes | 25 (1.6) | 14 (3.1) | 11 (1.4) | 0 | 0.003 |

| Lung volume reduction, yes | 34 (2.3) | 15 (3.5) | 17 (2.1) | 2 (0.7) | 0.049 |

| Emphysema, yes | 1047 (87.5) | 289 (86.8) | 575 (89.4) | 183 (83.2) | 0.047 |

| Serum AAT level, mg/dL | 37.5 ± 25.1 | 30.7 ± 22.8* | 36.7 ± 23.4* | 49.0 ± 28.3* | < 0.001 |

| Inhaler corticosteroid users | 907 (59.0) | 284 (64.1) | 478 (58.9) | 145 (51.1) | 0.002 |

Abbrevations: COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, BMI: Body mass index, AATD: Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, continuous variables were presented as mean± standart deviation, categorical variables were presented as number and percent: n (%), *: Shows the statistically significant difference between the groups. Kruskal Wallis test was used for continuous variables and Chi Square test was used for categorics

Abbrevations: GOLD: Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease, mMRC: Modiffied medical research council, FVC: Forced vital capacity; FEV1: Forced expiratory volume in 1 s; KCO: Carbon monoxide transfer coefficient; CAT: COPD assessment test; BODEx: Body mass index, obstruction, dyspnoea, exacerbations index; EQ-5D: Euro QoL 5 dimensions questionnaire, AAT: Alpha-1 antitrypsin, CS: Corticosteroid

continuous variables were presented as mean± standart deviation, categorical variables were presented as number and percent: n (%)

*: Shows the statistically significant difference between the groups. Kruskal Wallis test was used for continuous variables and Chi Square test was used for categorics

The BODE index and CAT scores were lowest in patients diagnosed at age ≥ 65, while the EQ-5D index was lower in this group compared to those diagnosed before age 45. Mean FEV1%, FEV1/FVC ratio, FVC%, DLCO%, and KCO% were highest in patients diagnosed at age ≥ 65. Serum AAT levels were also highest in those diagnosed at older ages (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Box pilot graphs show the serum AAT levels and FEV1% according to AATD diagnosis age groups

Younger patients were more likely to receive augmentation therapy, with the highest proportion in the < 45 group (43% vs. 24% in the ≥ 65 group). The use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) was most common in those diagnosed at a younger age, consistent with their more severe disease.

There were data from 23 countries in the dataset and they were grouped to regions as seen in Table 2. Southern Europe, had the highest proportion of patients diagnosed after the age of 65, in addition to the highest rate of current smokers, and higher rate of Pi*SS AATD, compared to other regions (Table 2; Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Distribution of COPD patients regarding AATD diagnosis age groups, smoking status and genotype

| America | Central Europe | Northern Europe | Southern Europe | Asia | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AATD Diagnosis age, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||||

| < 45 | 15 (18.5) | 87 (41.2) | 129 (31.9) | 135 (20.7) | 4 (21.1) | |

| 45–65 | 49 (60.5) | 92 (43.6) | 220 (54.5) | 355 (54.4) | 12 (63.2) | |

| ≥65 | 17 (21.0) | 32 (15.2) | 55 (13.6) | 163 (25.0) | 3 (15.8) | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||||

| Current smoker | 2 (2.5) | 10 (4.7) | 13 (3.2) | 73 (11.2) | 2 (10.5) | |

| Former smoker | 57 (70.4) | 147 (69.7) | 265 (65.6) | 450 (68.9) | 12 (63.2) | |

| Never smoker | 22 (27.2) | 54 (25.6) | 126 (31.2) | 130 (19.9) | 5 (26.3) | |

| Genotype, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||||

| PI*ZZ | 58 (71.6) | 172 (81.5) | 311 (77.0) | 314 (48.1) | 7 (36.8) | |

| PI*SZ | 11 (13.6) | 18 (8.5) | 31 (7.7) | 179 (27.4) | 0 | |

| PI*SS | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.7) | 72 (11.0) | 0 | |

| Other | 12 (14.8) | 21 (10.0) | 59 (14.6) | 88 (13.5) | 12 (63.2) | |

| Index case, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||||

| Yes | 77 (95.1) | 162 (76.8) | 367 (90.8) | 575 (88.1) | 17 (89.5) | |

| No | 4 (4.9) | 49 (23.2) | 37 (9.2) | 78 (11.9) | 2 (10.5) |

America: Argentina (n=41), Canada (n=37), Colombia (n=4), Central Europe: Austria (n=25), Chech Republic (n=52), Germany (n=72), Poland (n=6), Switzerland (n=56), Northern Europe: Belgium (n=56), Denmark (n=20), Estonia (n=7), France (n=98), Nerherlands (n=47), Sweeden (n=88), United Kingdom (n=88), Southern Europe: Croatia (n=24), Greece (n=1), Italy (n=47), Portugal (n=136), Serbia and Montenegro (n=4), Spain (n=441), Asia: Türkiye (n=19). *Bulgary was excluded from the regional grouping (n = 1)

Fig. 3.

Distribution of patients regarding their genotype and AATD diagnosis age groups according to regions

Table 3 and the Fig. 4 presents the factors associated with a diagnosis age of ≥ 65, both overall and in the subgroup analysis of Pi*ZZ cases. Compared to never-smokers, former smokers (OR = 0.08; 95% CI: 0.03–0.23) and, current smokers (OR = 0.43; 95% CI: 0.27–0.70) were negatively associated with an older age at diagnosis.

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression models for total sample and for Pi*ZZ cases regarding the associated factors with diagnosis age of ≥65

| All sample | All Pi*ZZ cases | All index cases | Index Pi*ZZ cases | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95%CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95%CI | p | |

| Demographics | ||||||||||||

| Smoking status | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Never | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Former | 0.08 | 0.03–0.23 | < 0.001 | < 0.01 | < 0.01–1.50 | 0.998 | 0.05 | 0.01–0.20 | < 0.001 | < 0.01 | < 0.01–1.50 | 0.998 |

| Curent | 0.43 | 0.27–0.70 | < 0.001 | 0.24 | 0.13–0.47 | < 0.001 | 0.38 | 0.23–0.65 | < 0.001 | 0.18 | 0.08–0.38 | < 0.001 |

| Genotype | 0.111 | - | - | - | 0.231 | - | - | - | ||||

| PI*ZZ | ref | ref | ref | - | - | - | ref | ref | ref | - | - | - |

| Other | 1.10 | 0.53–2.27 | 0.803 | - | - | - | 1.33 | 0.61–2.88 | 0.472 | - | - | - |

| PI*SS | 3.24 | 1.19–8.83 | 0.022 | - | - | - | 2.64 | 0.88–7.95 | 0.084 | - | - | - |

| PI*SZ | 1.85 | 0.98–3.49 | 0.058 | - | - | - | 2.01 | 1.01–4.04 | 0.049 | - | - | - |

| QoL measures | ||||||||||||

| CAT score | 1.03 | 0.99–1.07 | 0.063 | 1.04 | 0.98–1.09 | 0.130 | 1.03 | 0.99–1.08 | 0.079 | 1.05 | 0.99–1.12 | 0.097 |

| EQ-5D index | 2.19 | 0.55–8.73 | 0.268 | 0.42 | 0.08–2.21 | 0.303 | 2.36 | 0.52–10.74 | 0.268 | 0.27 | 0.04–1.99 | 0.198 |

| Lung functions, serum AAT level | ||||||||||||

| FEV1%predicted | 1.01 | 1.001–1.02 | 0.046 | 1.03 | 1.02–1.05 | < 0.001 | 1.01 | 0.99–1.02 | 0.138 | 1.04 | 1.02–1.06 | < 0.001 |

| KCO% predicted | 0.99 | 0.98–1.01 | 0.514 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 | 0.246 | 0.99 | 0.98–1.01 | 0.562 | 0.99 | 0.96–1.01 | 0.222 |

| AAT serum levels | 1.02 | 1.01–1.03 | < 0.001 | 1.03 | 1.01–1.05 | 0.004 | 1.02 | 1.01–1.04 | < 0.001 | 1.04 | 1.02–1.07 | < 0.001 |

| Constant | 0.003 | - | < 0.001 | 0.06 | - | 0.020 | 0.04 | - | < 0.001 | 0.05 | - | 0.040 |

Abbrevations: QoL: Quality of life, CAT: COPD assessment test, EQ-5D: Euro QoL 5 dimensions questionnaire, FEV1: Forced expiratory volume in 1 s, KCO: Carbon monoxide transfer coefficient

Fig. 4.

Multivariable logistic regression models of factors associated with diagnosis age 65 and over

FEV1% and serum AAT levels were positively associated with a diagnosis age of ≥ 65. Compared to the Pi*ZZ genotype, the Pi*SS genotype was more than three times more likely to be associated with a diagnosis age of ≥ 65. In the Pi*ZZ subgroup, current smoking was negatively associated with an older age at diagnosis (OR = 0.24, 95%CI = 0.13–0.47), whereas FEV1% (OR = 1.03, 95%CI = 1.02–1.05) and serum AAT levels (OR = 1.03, 95%CI = 1.01–1.05) were positively associated.

Sub-group analysis of index cases showed that former smoking and current smoking were negatively associated factors with diagnosis age of ≥65, whereas, Pi*SZ genotype (OR = 2.01, 95%CI = 1.01–4.04) and serum AAT level (OR = 1.02, 95%CI:1.01–1.04) were positively associated factors with diagnosis age of ≥65. Sub-group analysis of Pi*ZZ index cases showed current smoking (OR = 0.18, 95%CI = 0.08–0.38) was negatively associated with ≥65 diagnosis age, whereas, FEV1% (OR = 1.04, 95%CI = 1.02–1.06) and serum AAT level (OR = 1.04, 95%CI = 1.02–1.07) were positively associated with ≥65 diagnosis age.

Discussion

This study found almost a fifth of patients with AATD-COPD were diagnosed at age 65 or older. These patients exhibited distinct clinical and functional characteristics compared to their younger counterparts. Individuals diagnosed later in life had milder pulmonary function impairments, lower symptom burden, and better quality of life. Their serum AAT levels were higher, and the prevalence of the Pi*ZZ mutation—associated with severe deficiency - was lowest, whereas the prevalence of the Pi*SS or Pi*SZ mutations - linked to less severe deficiency - was highest.

Smoking behavior is a key factor influencing disease severity, with significant implications for disease progression and patient outcomes. In our study, smoking exposure was lowest in those diagnosed at an older age, a relationship that remained consistent across all multivariable models and was not restricted to the Pi*ZZ subgroup. Taken together, these findings suggest that patients diagnosed later in life may experience a milder disease course, potentially due to lower cumulative smoke exposure. In contrast, those diagnosed at a younger age are more likely to have a more severe disease presentation, likely driven by both higher exposure to environmental triggers and a more aggressive natural disease progression due to a higher prevalence of severe AATD phenotypes.

It is well known from previous studies that individuals exposed to airway-irritating substances - such as smoking or occupational exposure—develop symptoms much earlier, seek medical care, and therefore receive a diagnosis earlier. In contrast, non-smokers develop symptoms later, after the age of 60, which leads to a delayed diagnosis. Studies from Swedish registers are good examples to show the natural course of the disease due to newborn screening programme and follow the cases longitudinally, have shown that never-smokers develop COPD later, and usually have a milder form of the disease [8, 9]. Our study, which focused on AATD-COPD cases whose diagnosis was delayed until older age, showed that in this group, mutation type was associated with diagnosis at age 65 years or older, depending on its effect on disease severity. This highlights a delay in diagnosis for SS and SZ mutations. These phenotypes were most common in Southern Europe. According to our findings, the age at diagnosis of 65 years and older was also highest in Southern Europe. The fact that the smoking rate was also the highest in Southern Europe and the rate of delayed diagnosis was also the highest in Southern Europe supports us in terms of delayed symptoms and delayed diagnosis due to the mild natural course of the disease due to the effect of genotype. Therefore, one of the main messages of this study is that in the presence of all AAT mutations causing COPD, patients should be enrolled in the registries and their natural history should be followed in order to reach a consensus on treatment recommendations.

Another notable finding of our study is factors influencing delay in AATD diagnosis, defined as the time between COPD diagnosis and AATD diagnosis. In the age < 45 group, AATD was diagnosed, on average, three years after COPD diagnosis. The delay was longer in older age groups, with a median of five years. This suggests that AATD is more likely to be recognised in younger COPD patients but often overlooked in older COPD patients, where COPD is more commonly attributed to other causes, such as smoking exposure. Previous studies have evaluated diagnostic delay as the time from the first symptom to AATD diagnosis, with an average delay of 5–6 years reported [3]. Meischl et al.’s study on 268 patients in the Austrian AATD registry found a median diagnostic delay of 5.3 years. A multivariable analysis assessing factors associated with a diagnostic delay of > 2 years did not identify an association with age or active smoking. However, the dataset included only 10 current smokers and 62 patients with a diagnostic delay of < 2 years, limiting the statistical power to detect such associations [12].

Physicians’ lack of awareness about AATD has been suggested as a contributing factor to delayed diagnosis. Studies that assessed knowledge of AATD via questionnaires have found that doctors often have insufficient knowledge of AATD [15]. Other cited reasons for delayed diagnosis include non-compliance with recommended guidelines and therapeutic nihilism [3].

Since our study showed that older COPD patients are more likely to be overlooked for AATD testing compared to younger COPD patients, these factors alone may not fully explain the results. Instead, cognitive biases - such as the perception that AATD primarily affects younger individuals or causes only severe (not mild) COPD—may play a role. Current guidelines recommend that all COPD patients be tested for AATD. Our findings reinforce the importance of adhering to these guidelines and highlight the need for improved awareness and diagnostic approaches, particularly in older COPD patients. However, identification of AATD via screening of asymptomatic, or lower risk patients may lead to increased health anxiety in patients who would otherwise have remained symptom free [16].

This study suggests that that COPD patients diagnosed with AATD at an older age have a milder clinical course. This is supported by their better pulmonary function, gas transfer capacity, and quality of life assessments. Further results showed that those diagnosed at an older age had lower smoking exposure, with the highest proportion of never-smokers in this group. A subgroup analysis limited to Pi*ZZ individuals yielded similar findings, reinforcing the impact of tobacco exposure.

Key factors that influence a clinicians decision to initiate augmentation therapy includes younger age, lower serum AAT levels, higher symptom burden, and more impaired pulmonary function [17]. However, when considering studies from the EARCO registry, the first study comparing Pi*ZZ individuals − 81.4% of whom had chronic respiratory disease - found that both the mean age at diagnosis and the current mean age of non-augmented Pi*ZZ patients were lower than those of Pi*ZZ-augmented patients [12]. Additionally, augmented patients had poorer quality of life (QoL) scores and more impaired lung function parameters. In our study, the group diagnosed at an older age had the lowest rate of augmentation therapy, likely due to their lower symptom burden and better pulmonary function. However, bias favoring the treatment of younger patients may be a consideration. The long-term benefit of augmentation therapy on lung function and mortality should be balanced against cost, particualry in resource limited health care infrastructures. This may be one reason why augmentation therapy is less favoured in the elderly population. However, since there are also publications suggesting that augmentation therapy for severe alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency improves survival and is decoupled from spirometric decline, in addition to decreasing exacerbations, it is necessary not to make a treatment bias based only on the age factor [18, 19].

Another EARCO registry study examining gender differences found no significant difference in the mean age at diagnosis between men and women. However, being aged ≥ 60 was positively associated with a modified mMRC score ≥ 2 and a CAT score ≥ 10. Additionally, COPD diagnosis, age ≥ 60, a history of smoking, and female gender were all positively associated with greater symptom burden [20].

Among PiSS cases, the mean age was higher than in Pi*ZZ cases, with a later mean age at diagnosis (54 ± 16 years vs. 42 ± 18 years in Pi*ZZ cases) in both propensity score-matched and unmatched analyses. In the matched population, compared to Pi*ZZ cases, PiSS individuals had higher FEV1%, FEV1/FVC, and KCO% values, but worse QoL scores. However, when compared to Pi*SZ cases in the propensity score-matched analysis, the only significant difference in Pi*SS individuals was a higher mean serum AAT level, while all other demographic and clinical characteristics - including age, lung function, and QoL parameters - were similarly distributed [21].

In our study, individuals with the PiSS genotype in the overall cohort, as well as those with Pi*SZ mutations among index cases, were more frequently diagnosed at an older age. This strong positive association remained significant in the multivariable regression model, aligning with prior published findings.

There are relatively few studies examining smoking behaviour in individuals with AATD-associated COPD, and international data on smoking rates in this population remain limited. Genetic testing for AATD has been shown to influence smoking cessation [22]. One study found that smokers developed more severe emphysema at an earlier age compared to never-smokers [23].

Multivariable regression analysis in ever-smokers identified several independent associations, including increased emphysema, lower DLCO values, greater airflow obstruction, and increased sputum production. A study evaluating AATD patients at age 42 found that smoke-exposed Pi*ZZ individuals exhibited signs of COPD, poorer general health, and greater breathlessness. However, Pi*ZZ never-smokers showed early physiological signs of emphysema [24].

This suggests that while AATD-related disease can develop in the absence of cigarette smoking, smoking significantly worsens disease severity. However, disease in never-smokers does not appear to impact mortality, as studies have shown that never-smoking Pi*ZZ individuals identified through screening have a similar life expectancy to never-smokers without AATD in the Swedish general population [25]. It seems the most critical intervention for Pi*ZZ individuals is to avoid smoking altogether. This underscores the importance of early AATD diagnosis to support smoking prevention and cessation efforts.

A review evaluating the prevalence of Pi*ZZ mutations in COPD patients found that the highest prevalence was in Northern Europe, followed by Western, Southern, and Central Europe. Outside Europe, high prevalence rates were observed in Australia-New Zealand and the United Kingdom, while significantly lower prevalence was reported in large parts of Asia and Africa [26].

In our study, the highest prevalence of Pi*ZZ was observed in Central Europe, Northern Europe, and America, whereas Pi*SZ and Pi*SS mutations were most common in Southern Europe. Other mutations were most prevalent in Asia. The proportion of current smokers was higher in Southern Europe than in Northern Europe, consistent with previous studies that included all patients with the Pi*ZZ genotype [27].

Since the highest proportion of Pi*SS mutations was found in Southern Europe, this may explain the higher proportion of individuals diagnosed at an older age in this region. Given that Pi*SS is associated with a milder disease course, this trend may persist despite the lower proportion of never-smokers compared to other regions.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of our study is its large sample size and ability to account for confounders that impact disease severity. However, due to the study design, limited conclusions can be drawn regarding the causes of delayed diagnosis in older patients.

While the later onset of symptoms and clinical findings in patients diagnosed at an older age may be partially explained by lower smoking exposure, another contributing factor may be the higher serum AAT levels observed in this group. This pattern was noted specifically in the Pi*ZZ subgroup analysis. The reason for higher serum AAT levels in older-diagnosed patients remains unclear, making this an important research question for future investigation.

Since serum AAT is an acute-phase reactant, the timing of its measurement is critical, and simultaneous measurement with C-reactive protein (CRP) is recommended [28]. Another approach is to perform genotyping/sequencing simultaneously with AAT in the presence of conditions that affect the AAT level, so that the diagnosis of heterozygous strains is not missed [29]. However, in our study, CRP data were missing in many cases, preventing us from assessing whether inflammation influenced the observed age-related differences in serum AAT levels. This is likely to have a small impact on the results, since many patients had concomitant AAT genotyping.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that the age at diagnosis of AATD in COPD patients varies, with 18% diagnosed at an advanced age. Patients diagnosed later in life were more likely to have Pi*SS mutations, a milder clinical presentation, lower cigarette exposure, better pulmonary function, and higher serum AAT levels. Similar findings were observed when analysing individuals with the PiZZ mutation.

The association between lower tobacco exposure and a milder disease course in those diagnosed at an older age highlights the critical role of smoking prevention in reducing the development and progression of AATD-related lung disease. Furthermore, the later presentation in these individuals suggests that subclinical or less overt symptoms may delay diagnosis. These findings underscore the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for AATD in all COPD patients - regardless of age - to ensure timely identification and appropriate management.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients who participated in this study and the EARCO study investigators (listed below). We wish to acknowledge Elise Heuvelin and Valerija Arsovski from the ERS office (Lausanne, Switzterland) for her support in the management of EARCO, and Andrea Forés and Mireia Bonet (Bioclever, Barcelona, Spain) for her support in EARCO data monitoring.

List of EARCO study investigators

Mariano Fernandez-Acquier, Andrés L. Echazarreta (Argentina), Georg-Christian Funk, Karen Schmid-Scherzer (Austria), Wim Janssens, Silvia Pérez-Bogerd (Belgium), Kenneth Chapman (Canada), Leidy Prada (Colombia), Ana Hecimovic (Croatia), Eva Bartošovská (Czech Republic), Alan Altraja, Jaanus Martti (Estonia), Eric Y.E. Derom, Maeva Zysman, Jean-François Mornex, Martine Reynaud-Gaubert (France), Timm Greulich, Felix JF Herth, Franziska Trudzinski, Rembert Koczulla, Matthias Welsner (Germany), Gerry McElvaney (Ireland), Angelo G. Corsico, Ilaria Ferrarotti, Simone Scarlata, Mario Malerba, Luciano Corda (Italy), Jan Stolk, Emily F van’t Wout (Netherlands), Joanna Chorowstoska-Wyminko (Poland), Catarina Guimaraes, Maria Sucena, Ana Caldas, Raquel Marçoa, Isabel Ruivo dos Santos, Bebiana Conde, Maria Joana Reis Amado Maia Da Silva, Rita Boaventura, Cristina Santos, Gabriela Santos, Filipa Costa, Teresa Martin, Joana Gomes, Sonia Isabel Silva Guerra (Portugal), Ruxandra Ulmeanu (Romania), María Torres-Duran, Marc Miravitlles, Miriam Barrecheguren, Juan Luis Rodriguez-Hermosa, Myriam Calle-Rubio, José María Hernández-Pérez, José Luis López-Campos, Francisco Casas-Maldonado, Ana Bustamante, Carlota Rodriguez-García, Marta García-Clemente, Cruz González, Eva Tabernero, Lourdes Lázaro, Virginia Almadana, Mar Fernández-Nieto, Francisco Javier Michel de la Rosa, Carlos Martínez-Rivera, Layla Diab, María Isabel Parra, Nuria Rodríguez-Lázaro, Susana Martínez, Rosanel Amaro, Ramon-Antonio Tubio (Spain), Hanan Tanash, Eeva Piitulainen (Sweden), Christian F Clarenbach (Switzerland), Serap Argun Baris, Dilek Karadogan, Sebahat Genç, Ouksel Hakima (Turkey), Alice M Turner, Beatriz Lara, David G Parr, Charlotte Bolton, John Hurst, Ravi Mahadeva, Nicholas Hopkinson (United Kingdom). EARCO Steering committee: Christian F Clarenbach and Marc Miravitlles (Co-chairs), David G Parr, Catarina Guimaraes, Hanan Tanash, Karen O’Hara, Marion Wilkens, Alice M. Turner, Jens-Ulrik Stæhr Jensen, Maria Torres-Duran, Angelo Corsico.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to study conception or design, and/or data analysis and interpretation. All authors were involved in the writing, reviewing and final approval of the manuscript, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

The International EARCO registry is funded by unrestricted grants of Grifols, CSL Behring, Kamada, pH Pharma, Sanofi and Takeda to the European Respiratory Society (ERS). AMT is funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Midlands Patient Safety Research Collaboration (PSRC) and West Midlands Applied Research Collaborative (WM-ARC). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of confidentiality and are available from the Steering Committee of EARCO with reasonable request. Data are located in EARCO registry. Available from: https://www.earco.org/earco-registry.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol received central ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Barcelona, Spain (PR(AG)480/2018) and was subsequently approved by all participating centres. Also every participating center obtained ethical approval from coordinating centers of the country. For Türkiye (corresponding author’s country) from Manisa Celal Bayar University Medical Faculty Clinical Researches Ethical Committee Approval number 39, Date: 06.08.2019 and for EARCO exacerbation study from Recep Tayyip Erdoğan University Clinical Researches Ethical Committee Approval number:274, Date: 12.06.2024. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study was completed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration as revised in 2013.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients described herein for their anonymized information to be published in this article.

Competing interests

Catarina Guimarães has received speaker fees from CSLBehring. María Torres-Durán has received either speaker and consulting fees from CSL Behringand Grifols, and support for attending meetings from CSL Behring, Grifols, Chiesi and FAESFarma. Alice M Turner has received either grants or speaker fees from AstraZeneca,GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, CSL Behring, Takeda, Vertex and GrifolsBiotherapeutics. Hanan Tanash has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline,Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi and Grifols. Carlota Rodríguez-García has received speaker feesfrom AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols, Chiesi, and CSL Behring, expert testimony for Chiesi,support for attending meetings from Chiesi and Grifols. Angelo Corsico has received speakerfees and honoraria for participation on advisory board from CSL Behring, and honoraria formanuscript writing from Grifols. JoséLuis López-Campos has received honoraria during the last3 years for lecturing, scientific advice, participation in clinical studies or writing for publications for (alphabetical order): AstraZeneca, Bial, Boehringer, Chiesi, CSL Behring, Faes, Gebro, Grifols, GSK, Menarini, Sanofi, Zambon. Juan Luis Rodríguez-Hermosa has received honoraria during the last 3 years for lecturing, scientific advice or participation in clinical studies from AstraZeneca, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, CSL Behring, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols and Zambon. JoséMaría Hernández-Pérez has received consulting fees from Grifols and CSL Behring, speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Bial, CSL Behring, FAES laboratory, GlaxoSmithKline, and Grifols, support for attending meetings from Grifols and CSL Behring, and honoraria for participation on advisory board from Grifols. Maria Sucena has received consulting fees from Bial, GSK, CSL Behring Grifols and Sanofi, speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Bial, CSL Behring, GSK and Grifols. Paul Ellis has received speaker frees from Chiesi, Astra Zeneca, GSK and Takeda. The remaining authors report no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Quinn M, Ellis P, Pye A, Turner AM. Obstacles to early diagnosis and treatment of Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency: current perspectives. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2020;16:1243–55. 10.2147/TCRM.S234377. PMID: 33364772; PMCID: PMC7751439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hiller AM, Piitulainen E, Tanash H. The clinical course of severe Alpha-1-Antitrypsin deficiency in patients identified by screening. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:43–52. 10.2147/COPD.S340241. PMID: 35023912; PMCID: PMC8743380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stoller JK. Detecting Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency: Current State, Impediments, Opportunities, and Future Directions. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2024 Sep 23. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202406-600FR. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39311761. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Miravitlles M, Dirksen A, Ferrarotti I, Koblizek V, Lange P, Mahadeva R, McElvaney NG, Parr D, Piitulainen E, Roche N, Stolk J, Thabut G, Turner A, Vogelmeier C, Stockley RA. European Respiratory Society statement: diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary disease in α1-antitrypsin deficiency. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(5):1700610. 10.1183/13993003.00610-2017. PMID: 29191952. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Calle Rubio M, Soriano JB, López-Campos JL, Soler-Cataluña JJ, Alcázar Navarrete B, Rodríguez González-Moro JM, Miravitlles M, Barrecheguren M, Fuentes Ferrer ME, Rodriguez Hermosa JL, EPOCONSUL Study. Testing for alpha-1 antitrypsin in COPD in outpatient respiratory clinics in Spain: A multilevel, cross-sectional analysis of the EPOCONSUL study. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0198777. 10.1371/journal.pone.0198777. Erratum in: PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0212522. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212522. PMID: 29953442; PMCID: PMC6023216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Soriano JB, Lucas SJ, Jones R, Miravitlles M, Carter V, Small I, Price D, Mahadeva R, Respiratory Effectiveness Group. Trends of testing for and diagnosis of α1-antitrypsin deficiency in the UK: more testing is needed. Eur Respir J. 2018;52(1):1800360. 10.1183/13993003.00360-2018. PMID: 29853490. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Brantly ML, Paul LD, Miller BH, Falk RT, Wu M, Crystal RG. Clinical features and history of the destructive lung disease associated with alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency of adults with pulmonary symptoms. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;138(2):327– 36. 10.1164/ajrccm/138.2.327. PMID: 3264124. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Piitulainen E, Mostafavi B, Tanash HA. Health status and lung function in the Swedish alpha 1-antitrypsin deficient cohort, identified by neonatal screening, at the age of 37–40 years. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:495–500. PMID: 28203073; PMCID: PMC5298298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mostafavi B, Piitulainen E, Tanash HA. Survival in the Swedish cohort with alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, up to the age of 43–45 years. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:525–30. PMID: 30880942; PMCID: PMC6400233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campos MA, Alazemi S, Zhang G, Salathe M, Wanner A, Sandhaus RA, Baier H. Clinical characteristics of subjects with symptoms of alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency older than 60 years. Chest. 2009;135(3):600–8. 10.1378/chest.08-1129. Epub 2008 Nov 18. PMID: 19017884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tejwani V, Nowacki AS, Fye E, Sanders C, Stoller JK. The impact of delayed diagnosis of Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency: the association between diagnostic delay and worsened clinical status. Respir Care. 2019;64(8):915–22. 10.4187/respcare.06555. Epub 2019 Mar 26. PMID: 30914495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meischl T, Schmid-Scherzer K, Vafai-Tabrizi F, Wurzinger G, Traunmüller-Wurm E, Kutics K, Rauter M, Grabcanovic-Musija F, Müller S, Kaufmann N, Löffler-Ragg J, Valipour A, Funk GC. The impact of diagnostic delay on survival in alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency: results from the Austrian Alpha-1 lung registry. Respir Res. 2023;24(1):34. 10.1186/s12931-023-02338-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greulich T, Altraja A, Barrecheguren M, Bals R, Chlumsky J, Chorostowska- Wynimko J, et al. Protocol for the EARCO registry: a pan‐European observational study in patients with α1‐antitrypsin deficiency. ERJ Open Res. 2020;6(1):00181–2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miravitlles M, Turner AM, Torres-Duran M, Tanash H, Rodríguez-García C, López-Campos JL, Chlumsky J, Guimaraes C, Rodríguez-Hermosa JL, Corsico A, Martinez-González C, Hernández-Pérez JM, Bustamante A, Parr DG, Casas-Maldonado F, Hecimovic A, Janssens W, Lara B, Barrecheguren M, González C, Stolk J, Esquinas C, Clarenbach CF. Clinical and functional characteristics of individuals with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency: EARCO international registry. Respir Res. 2022;23(1):352. 10.1186/s12931-022-02275-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esquinas C, Barrecheguren M, Sucena M, Rodriguez E, Fernandez S, Miravitlles M, et al. Practice and knowledge about diagnosis and treatment of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency in Spain and Portugal. BMC Pulm Med. 2016;16:64. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Worthington AK, Parrott RL, Smith RA, Spirituality. Illness unpredictability, and math anxiety effects on negative affect and affect-Management coping for individuals diagnosed with Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Health Commun. 2018;33(4):363–71. Epub 2017 Jan 6. PMID: 28059573; PMCID: PMC5533635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greulich T, Albert A, Cassel W, Boeselt T, Peychev E, Klemmer A, Ferreira F, Clarenbach C, Torres-Duran ML, Turner AM, Miravitlles M. Opinions and attitudes of pulmonologists about augmentation therapy in patients with Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. A survey of the EARCO group. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:53–64. PMID: 35023913; PMCID: PMC8743984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fraughen DD, Ghosh AJ, Hobbs BD, Funk GC, Meischl T, Clarenbach CF, Sievi NA, Schmid-Scherzer K, McElvaney OJ, Murphy MP, Roche AD, Clarke L, Strand M, Vafai-Tabrizi F, Kelly G, Gunaratnam C, Carroll TP, McElvaney NG. Augmentation therapy for severe Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency improves survival and is decoupled from spirometric Decline-A multinational registry analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;208(9):964–74. 10.1164/rccm.202305-0863OC. PMID: 37624745; PMCID: PMC10870866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karadoğan D, Dreger B, Osaba L, Ahmetoğlu E, Özyurt S, Yılmaz Kara B, Hürsoy N, Telatar TG, Şahin Ü. Clinical implications of the SERPINA1 variant, mpalermo, and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency in Türkiye. BMC Pulm Med. 2024;24(1):622. 10.1186/s12890-024-03421-y. PMID: 39696116; PMCID: PMC11657439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ersöz H, Torres-Durán M, Turner AM, Tanash H, Rodríguez García C, Corsico AG, López-Campos JL, Miravitlles M, Clarenbach CF, Chapman KR, Hernández Pérez JM, Guimarães C, Bartošovská E, Greulich T, Barrecheguren M, Koczulla AR, Höger P, Olivares Rivera A, Herth F, Trudzinski FC. EARCO study investigators. Sex-Differences in Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency: data from the EARCO registry. Arch Bronconeumol. 2025;61(1):22–30. 10.1016/j.arbres.2024.06.019. English, Spanish. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martín T, Guimarães C, Esquinas C, Torres-Duran M, Turner AM, Tanash H, Rodríguez-García C, Corsico A, López-Campos JL, Bartošovská E, Stæhr Jensen JU, Hernández-Pérez JM, Sucena M, Miravitlles M. Risk of lung disease in the PI*SS genotype of alpha-1 antitrypsin: an EARCO research project. Respir Res. 2024;25(1):260. 10.1186/s12931-024-02879-y. PMID: 38926693; PMCID: PMC11210092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roche SM, Carroll TP, Fraughen DD, McElvaney NG. Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency and Smoking Cessation: Tackling the Burden of COPD One Test at a Time? Chest. 2023;163(4):e197. 10.1016/j.chest.2022.10.043. PMID: 37031997. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.O’Brien ME, Pennycooke K, Carroll TP, Shum J, Fee LT, O’Connor C, Logan PM, Reeves EP, McElvaney NG. The impact of smoke exposure on the clinical phenotype of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency in ireland: exploiting a National registry to understand a rare disease. COPD. 2015;12(Suppl 1):2–9. 10.3109/15412555.2015.1021913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schramm GR, Mostafavi B, Piitulainen E, Wollmer P, Tanash HA. Lung function and health status in individuals with severe Alpha-1-Antitrypsin deficiency at the age of 42. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2021;16:3477–85. 10.2147/COPD.S335683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanash HA, Ekström M, Rönmark E, Lindberg A, Piitulainen E. Survival in individuals with severe alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency (PiZZ) in comparison to a general population with known smoking habits. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(3):1700198. 10.1183/13993003.00198-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blanco I, Diego I, Castañón C, Bueno P, Miravitlles M. Estimated worldwide prevalence of the PI*ZZ Alpha-1 antitrypsin genotype in subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Bronconeumol. 2023;59(7):427–34. 10.1016/j.arbres.2023.03.016. English, Spanish. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miravitlles M, Turner AM, Torres-Duran M, Tanash H, Rodríguez-García C, López-Campos JL, Chlumsky J, Guimaraes C, Rodríguez-Hermosa JL, Corsico A, Martinez-González C, Hernández-Pérez JM, Bustamante A, Parr DG, Casas-Maldonado F, Hecimovic A, Janssens W, Lara B, Barrecheguren M, González C, Stolk J, Esquinas C, Clarenbach CF. EARCO study investigators. Characteristics of individuals with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency from Northern and Southern European countries: EARCO international registry. Eur Respir J. 2023;61(3):2201949. 10.1183/13993003.01949-2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dasí F. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Med Clin (Barc). 2024;162(7):336–42. 10.1016/j.medcli.2023.10.014. English, Spanish. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hernández-Pérez JM, López-Charry CV. Is the determination of C-reactive protein really necessary in the diagnosis of Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency? Clin Respir J. 2022;16(5):420–2. 10.1111/crj.13494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of confidentiality and are available from the Steering Committee of EARCO with reasonable request. Data are located in EARCO registry. Available from: https://www.earco.org/earco-registry.