Abstract

Background

Obesity, especially visceral obesity, is an established risk factor associated with cognitive impairment (CI). Body roundness index (BRI) is a newer anthropometric measure for assessing body fat distribution. CI, obesity, and type 2 diabetes (T2D) pose formidable public health challenges, carrying irreversible health implications and imposing a substantial economic strain on healthcare systems worldwide. This study explored the relationship between BRI and CI in middle-aged and elderly patients with T2D.

Methods

A general statistical description of the study population was conducted, and logistic analyses were used to explore the association between BRI and CI. Sensitivity analyses and restricted cubic spline (RCS) methods were employed to further investigate the association between BRI and CI.

Results

Overall, 1318 participants were included, the prevalence of CI was 44.8% (590/1318). The participants’ mean age was 62.2 ± 7.7 years, of whom 48.6% were women. We found a positive relationship between BRI levels and CI, elevated BRI was correlated with higher risk of CI in crude (odds ratio [OR] = 1.46, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.19–1.80, p < 0.001) and fully adjusted models (OR = 1.26, 95% CI = 1.01–1.59, p = 0.045) in women. However, BRI was not related to the prevalence of CI in fully adjusted models (OR = 1.04, 95% CI = 0.80–1.37, p = 0.750) in men. Based on further stratified analyses, the results were stable.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that BRI was as effective predictor of CI and showed superior predictive accuracy in women than men. In clinical practice, BRI could be used to assess CI among middle-aged and elderly individuals with T2D.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40001-025-02849-0.

Keywords: Body roundness index, Cognitive impairment, Middle-aged and elderly, Type 2 diabetes

Introduction

As the global population ages, cognitive decline among the elderly is becoming an increasingly significant concern. In 2019, approximately 57.4 million individuals worldwide were diagnosed with dementia, which is projected to reach 152 million by 2050 [1]. Emerging evidence underscores the critical role of chronic inflammation and dysregulation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAS) in mediating diabetic complications, including potential cognitive effects [2, 3]. Among patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D), the estimated prevalence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is 45.0% [4]. In China, the prevalence of cognitive impairment (CI) among elderly patients with diabetes is 48%, with higher rates observed in women, older individuals, those with lower educational levels, lower income, without a spouse, and those living alone [5]. CI makes it difficult for elderly patients with diabetes to perform complex self-management tasks [6], such as monitoring blood glucose and adjusting insulin doses, and influences meal timing and dietary choices. Early identification of CI is crucial for the management of diabetes in middle-aged and elderly patients, as CI can hinder effective diabetes management, and poorly managed diabetes can exacerbate cognitive decline.

Obesity is defined as the excessive or abnormal accumulation of body fat that negatively impacts health. Over the past 50 years, the prevalence of obesity has risen dramatically worldwide, and overweight is currently considered a major global public health challenge. Obesity can disrupt brain homeostasis and adversely affect the central nervous system and cognitive function [7]. Obesity is a frequent comorbidity in patients with diabetes and impacts cognitive function. The relationship between them is complex and controversial [8]. Research has found a significant association between body mass index (BMI) and CI [9]. Some studies have demonstrated stability in BMI predicts better cognitive trajectories [10]. However, there are research findings that refute the hypothesis that middle-aged obesity increases the risk of dementia in old age [11]. A study based on an elderly Chinese population found no evidence that obesity increases the risk of CI [12], whereas in a study of elderly Americans, obesity was found to be associated with an increased risk of cognitive decline [13].

The predominant approach for screening obesity is the measurement of BMI (obesity BMI ≥ 30 kg/m) [14]. However, BMI cannot effectively distinguish between fat and muscle mass, nor it can accurately reflect an individual’s fat distribution [15, 16]. Waist circumference (WC) is a straightforward and trustworthy proxy of abdominal obesity [17].

Body roundness index (BRI), a new obesity metric based on human body shape to calculate body roundness introduced by Thomas et al. [18], combines WC, weight, and height. BRI demonstrates robust predictive capacity for fat distribution patterns and serves as a reliable metric for assessing visceral adiposity [19]. Compared to BMI or WC, BRI exhibited superior diagnostic accuracy in identifying for metabolic obesity in normal-weight individuals [20].

Only a few studies have explored the relationship between obesity and cognitive function in elderly patients with diabetes, indicating that central obesity may be a risk factor for dementia in women [21]. Recent studies have determined a link between the BRI and various health conditions, including cardiovascular disease [22, 23], depression [24], diabetes [25], and osteoarthritis [26, 27].

However, in the existing literature, studies on the relationship between BRI and CI in the T2D population remain insufficient. Therefore, we hypothesized that BRI may be an important indicator of CI. This study aimed to explore the correlation between BRI and CI using data from hospitalized patients with T2D from the Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism of the Tianjin Union Medical Center.

Research design and methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Adults aged ≥ 40 years with T2D were consecutively recruited at the Department of Endocrinology at Tianjin Union Medical Center between July 2018 and July 2022. T2D was diagnosed based on the 1999 WHO criteria for diabetes [28]. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) aged ≥ 40 years, diagnosed with T2D, and (2) able to independently complete neuropsychological tests. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) unable to complete neuropsychological tests because of speech disorders, hearing loss, or unwillingness to cooperate, (2) presence of conditions that may affect cognitive function, including head injury, cerebral ischemia, depression, anxiety, coma, drug addiction, or other mental and neurological disorders, and (3) has concurrent anemia (hemoglobin < 90 g/L), severe lung or kidney disease, history of heart failure, malignant tumors, and thyroid disorders. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Tianjin Union Medical Center, following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (Approval Number: (2018) Fast-track Review No. (C08)). Participants were informed about the study and signed consent forms before participating. Written consent was obtained for any identifiable images or data published in the article. Of the 1350 patients, 1318 patients were included. We excluded one patient aged < 40 years, 30 patients with missing WC and height data, and one patient with missing HbA1c data.

Body roundness index (BRI)

The participants’ height, weight, and WC were measured and recorded by professional nurses. The BRI is a novel metric for assessing body shape, calculated using height (m) and WC (cm). Height was measured as standing height, whereas WC was evaluated at the level midway between the lower rib and top of the hip while standing.

The calculation formula for BRI is presented as follows [18]:

Screening evaluation for cognitive impairment

In the screening and diagnosis of MCI, global cognitive function was evaluated using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test, in which a score of ≤ 25/26 indicated MCI [29]. For participants with ≤ 12 years of education, one point is added to their total MoCA score to adjust for educational bias [29]. In this study, participants were classified into two groups: normal cognition (NCF), with MoCA scores ≥ 26, and CoI groups, with MoCA scores < 26.

Covariates

Participants underwent a face-to-face survey using a questionnaire addressing their demographic and clinical characteristics, such as sex, age, ethnicity, marital status, education level, sedentary lifestyle, duration of diabetes, dietary control of diabetes, smoking and alcohol consumption status, and use of anti-diabetic agents. Additionally, participants reported their medical history of diabetic microangiopathy (including DN and/or DR) and hypoglycemic events in the past 3 months, lower limb atherosclerosis, stroke (including hemorrhagic and/or ischemic strokes), cardiovascular disease, and hypertension based on self-reports and medical records. Dietary management for diabetes refers to adhering to the dietary recommendations outlined in the “Expert Consensus on the Diagnosis and Treatment Measures for Elderly Patients with Type 2 Diabetes in China” [30].

Participants fasted for at least 8 h before undergoing serum biochemical analysis. Total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), and serum creatinine (sCr) were measured using an automatic biochemical analyzer (TBA-120FR, Toshiba, Japan), and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was analyzed with a fully automated HPLC-based Glycohemoglobin analyzer (HA-8180, ARKRAY, Japan). The estimated GFR was calculated using the formula developed by the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration [31].

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as means (SD) or medians (IQR), and categorical variables as frequencies or percentages (n, %). The Chi-square test was used for categorical variables, and the Student’s test or Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare variables between women and men. The analysis excluded missing data, ranging from 0 to 2.2%.

Logistic regression models were used to calculate the odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the relationship between BRI and CI. Model I was adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, including age, sex, marital status, and education level. Model II further adjusted for factors of diabetes course, diabetic dietary control, and smoking status. Model III further adjusted for stroke, hypoglycemic events in the past 3 months, eGFR, and TG plus model II. Tests for trend were conducted with linear regression by entering the median value of each BRI tertile as a continuous variable in the models. To examine the possible non-linear dose–response associations between BRI and CI after adjusting variables in model III, we employed restricted cubic splines (RCS) with four knots positioned at the fifth, 35th, 65th, and 95th percentiles suggested by Harrell. We used the likelihood ratio test and bootstrap resampling method to determine inflection points. A two-piece-wise logistic regression model with smoothing was used to analyze the association threshold between BRI and CI after adjusting the variables in model III. To verify the stability of the relationship between BRI and CI across different populations, interaction and subgroup analyses were conducted based on age (< 65 vs. ≥ 65 years), stroke history (yes or no), and hypoglycemic events in the past 3 months (yes or no). Logistic regression models were used to assess heterogeneity among subgroups, whereas likelihood ratio tests were employed to evaluate interactions between subgroups.

Considering that the sample size was based on the existing data, no a priori statistical power analysis was conducted. The analysis was conducted using R version 4.2.1 (available at http://www.R-project.org, The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria) and Free Statistics software (version 1.9.2, Beijing Free Clinical Medical Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (two sided). Data were analyzed between November and December 2024.

Results

Baseline features

This study enrolled 1318 adults (641 [48.6%] women, mean age; 62.2 ± 7.7 years). There are 590 (44.8%) individuals with CI. The mean ages of women and men were 63.0 ± 7.6 and 61.4 ± 7.7, respectively. The proportion of married and living with a partner (93.1% vs. 84.2%) and education levels were higher in men (11.1 ± 2.8 vs. 10.2 ± 2.9). eGFR, TC, and BRI (5.3 ± 0.8 vs. 4.6 ± 0.6, p < 0.001) were higher in women, whereas males consumed more smoke and alcohol than women (Table 1). Men were less likely to develop hypertension and hypoglycemia but more likely to develop LEAD and microangiopathy (all p < 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population

| Variables | Total (n = 1318) | T1 (2.75–4.52) (n = 439) | T2 (4.52–5.19) (n = 437) | T3 (5.19–8.28) (n = 442) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI, n (%) | 590 (44.8) | 161 (36.7) | 201 (46) | 228 (51.6) | < 0.001 |

| MOCA | 25.4 ± 2.6 | 25.9 ± 2.5 | 25.4 ± 2.5 | 25.0 ± 2.8 | < 0.001 |

| Age (years) | 62.2 ± 7.7 | 60.5 ± 7.4 | 61.9 ± 7.6 | 64.1 ± 7.7 | < 0.001 |

| Sex, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Female | 641 (48.6) | 97 (22.1) | 209 (47.8) | 335 (75.8) | |

| Male | 677 (51.4) | 342 (77.9) | 228 (52.2) | 107 (24.2) | |

| Married, n (%) | 1170 (88.8) | 411 (93.6) | 391 (89.5) | 368 (83.3) | < 0.001 |

| Education level (years) | 10.6 ± 2.9 | 11.0 ± 2.9 | 10.7 ± 2.9 | 10.2 ± 2.8 | < 0.001 |

| Course of diabetes (years) | 7.0 (1.0, 13.0) | 6.0 (1.0, 13.0) | 7.0 (1.0, 13.0) | 8.0 (2.0, 13.0) | 0.28 |

| Diabetic dietary control, n (%) | 856 (64.9) | 298 (67.9) | 280 (64.1) | 278 (62.9) | 0.269 |

| Regular exercise, n (%) | 929 (70.5) | 306 (69.7) | 310 (70.9) | 313 (70.8) | 0.907 |

| Hypoglycemia, n (%) | 300 (22.8) | 89 (20.3) | 101 (23.1) | 110 (24.9) | 0.258 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 117.9 ± 34.2 | 119.9 ± 30.3 | 119.0 ± 40.4 | 114.8 ± 30.9 | 0.065 |

| Smoke, n (%) | 382 (29.0) | 195 (44.4) | 115 (26.3) | 72 (16.3) | < 0.001 |

| Drink, n (%) | 334 (25.3) | 157 (35.8) | 121 (27.7) | 56 (12.7) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 878 (66.6) | 242 (55.1) | 292 (66.8) | 344 (77.8) | < 0.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 133.2 ± 13.4 | 130.3 ± 13.3 | 133.7 ± 12.9 | 135.5 ± 13.4 | < 0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 79.5 ± 8.5 | 79.0 ± 8.2 | 79.5 ± 8.4 | 79.9 ± 8.8 | 0.314 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 365 (27.7) | 109 (24.8) | 122 (27.9) | 134 (30.3) | 0.189 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 480 (36.4) | 115 (26.2) | 168 (38.4) | 197 (44.6) | < 0.001 |

| LEAD, n (%) | 764 (58.0) | 267 (60.8) | 262 (60) | 235 (53.2) | 0.042 |

| Microangiopathy, n (%) | 561 (42.6) | 180 (41) | 181 (41.4) | 200 (45.2) | 0.372 |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.9 ± 2.1 | 9.0 ± 2.2 | 9.0 ± 2.0 | 8.8 ± 2.0 | 0.24 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.9 ± 1.2 | 4.8 ± 1.3 | 4.9 ± 1.2 | 4.9 ± 1.1 | 0.451 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 2.0 ± 2.1 | 2.0 ± 1.9 | 2.2 ± 3.0 | 1.9 ± 1.1 | 0.19 |

| Weight (kg) | 72.0 ± 12.6 | 70.2 ± 10.8 | 71.8 ± 12.2 | 74.0 ± 14.3 | < 0.001 |

| Height (cm) | 166.1 ± 8.3 | 171.4 ± 6.9 | 166.1 ± 7.0 | 160.7 ± 7.3 | < 0.001 |

| WC (cm) | 91.4 ± 9.7 | 85.1 ± 7.5 | 91.0 ± 7.6 | 98.0 ± 9.4 | < 0.001 |

| BMI (m/kg2) | 26.0 ± 3.6 | 23.8 ± 2.5 | 25.8 ± 2.9 | 28.4 ± 3.8 | < 0.001 |

| Secretagogue, n (%) | 193 (14.6) | 60 (13.7) | 71 (16.2) | 62 (14) | 0.505 |

| Insulin, n (%) | 429 (32.5) | 128 (29.2) | 142 (32.5) | 159 (36) | 0.097 |

| MET, n (%) | 524 (39.8) | 159 (36.2) | 177 (40.5) | 188 (42.5) | 0.148 |

| SU, n (%) | 278 (21.1) | 81 (18.5) | 97 (22.2) | 100 (22.6) | 0.249 |

| Glinides, n (%) | 187 (14.2) | 52 (11.8) | 60 (13.7) | 75 (17) | 0.088 |

| TZD, n (%) | 26 (2.0) | 8 (1.8) | 9 (2.1) | 9 (2) | 0.962 |

| AGI, n (%) | 680 (51.6) | 230 (52.4) | 212 (48.5) | 238 (53.8) | 0.263 |

| DPP-4i, n (%) | 180 (13.7) | 57 (13) | 68 (15.6) | 55 (12.4) | 0.356 |

| SGLT2i, n (%) | 34 (2.6) | 14 (3.2) | 11 (2.5) | 9 (2) | 0.556 |

| GLP-1RA, n (%) | 14 (1.1) | 4 (0.9) | 3 (0.7) | 7 (1.6) | 0.485 |

| BRI | 4.9 ± 0.8 | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | 5.8 ± 0.5 | < 0.001 |

Continuous variables are expressed as mean (SD) or median (interquartile range), and categorical variables are expressed as n (%)

MOCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; SBP, Systolic Blood Pressure; DBP, Diastolic Blood Pressure; CVD, Cerebrovascular disease; LEAD, Lower Extremity Arterial Disease; HbA1c, Hemoglobin A1c; TC, Total Cholesterol; TG, Triglycerides; WC, waist circumference; BMI, Body Mass Index; MET, Metformin; SU, Sulfonylureas; TZD, Thiazolidinediones; AGI, Alpha-Glucosidase Inhibitors; DPP-4i, Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitors; SGLT2i, Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors; GLP-1RA, Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists; BRI, body roundness index

Association between BRI and CI

The crude model demonstrated that BRI was related to CI in women (OR = 1.46, 95% CI; 1.19–1.80), with no statistically significant difference with that of men (OR = 1.24, 95% CI; 0.97–1.59) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between BRI and CI in different models

| BRI | Crude Model | Model I | Model II | Model III | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| All participants | ||||||||

| Continuous | 1.38 (1.20–1.59) | < 0.001 | 1.20 (1.02–1.42) | 0.032 | 1.17 (0.98–1.38) | 0.075 | 1.17 (0.98–1.39) | 0.078 |

| T1 (2.75–4.52) | Reference | Reference | Reference | reference | ||||

| T2 (4.52–5.19) | 1.47 (1.12–1.93) | 0.005 | 1.37 (1.02–1.82) | 0.034 | 1.35 (1.00–1.80) | 0.047 | 1.34 (1.00–1.81) | 0.051 |

| T3 (5.19–8.28) | 1.84 (1.41–2.41) | < 0.001 | 1.45 (1.06–1.99) | 0.020 | 1.40 (1.02–1.93) | 0.038 | 1.39 (1.00–1.93) | 0.047 |

| P for trend | < 0.001 | 0.020 | 0.039 | 0.048 | ||||

| Male | ||||||||

| Continuous | 1.24 (0.97–1.59) | 0.088 | 1.08 (0.83–1.40) | 0.577 | 1.06 (0.82–1.38) | 0.653 | 1.04 (0.80–1.37) | 0.750 |

| T1 (2.83–4.29) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| T2 (4.29–4.81) | 1.39 (0.95–2.04) | 0.086 | 1.36 (0.92–2.01) | 0.126 | 1.38 (0.92–2.05) | 0.116 | 1.38 (0.92–2.07) | 0.117 |

| T3 (4.81–6.61) | 1.62 (1.11–2.37) | 0.012 | 1.35 (0.91–2.00) | 0.139 | 1.31 (0.88–1.95) | 0.188 | 1.27 (0.85–1.91) | 0.244 |

| P for trend | 0.013 | 0.140 | 0.192 | 0.251 | ||||

| Female | ||||||||

| Continuous | 1.46 (1.19–1.80) | < 0.001 | 1.30 (1.05–1.62) | 0.017 | 1.26 (1.00–1.57) | 0.045 | 1.26 (1.01–1.59) | 0.045 |

| T1 (2.75–4.92) | Reference | 0.005 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| T2 (4.92–5.56) | 1.75 (1.19–2.58) | < 0.001 | 1.62 (1.08–2.42) | 0.020 | 1.62 (1.07–2.44) | 0.022 | 1.70 (1.11–2.60) | 0.014 |

| T3 (5.56–8.28) | 2.03 (1.38–2.99) | < 0.001 | 1.70 (1.13–2.55) | 0.011 | 1.58 (1.04–2.40) | 0.031 | 1.64 (1.07–2.51) | 0.023 |

| P for trend | < 0.001 | 0.012 | 0.032 | 0.024 | ||||

Model I: Adjust for age, sex (only for overall population), marital status, education level

Model II: Adjust for diabetes course, diabetic dietary control, and smoking status plus model I

Model III: Adjust for stroke, hypoglycemic events in last 3 months, cardiovascular disease, microangiopathy, GFR, and TC plus model II;

Univariate logistic regression analyses revealed age, sex, marital status, educational level, diabetes course, diabetic dietary control, stroke, cardiovascular disease, smoke status, hypoglycemic events in the past 3 months, and eGFR were associated with CI (p < 0.05). Moreover, TC and microangiopathy were associated with CI (p < 0.1) (STable 2).

In women, if BRI was analyzed as a continuous variable, there was a significant association between BRI and CI in all models (p < 0.05). If BRI was converted to categorical variable (tertiles), the prevalence of CI showed a threshold effect (only first increased) in model III. Compared with individuals with lower BRI T1 (2.75–4.52), the adjusted OR values for BRI and CI in T2 (4.92–5.56) and T3 (5.56–8.28) were 1.70 (95% CI; 1.11–2.60, p = 0.014) and 1.64 (95% CI; 1.07–2.51, p = 0.023), respectively (Table 2).

This study suggests that higher BRI is associated with an increased risk of CI, particularly in women. The associations are generally stronger and more consistent in women compared to men. The findings highlight the importance of considering BRI as a potential risk factor for CI, especially in women. Further research is needed to explore the mechanisms underlying this association and validate these findings in other populations.

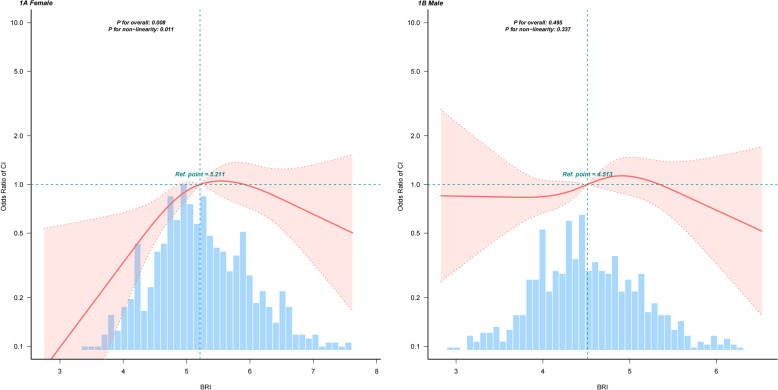

Threshold effect analysis

Fully adjusted models and restricted cubic splines curve (RCS) are shown separately for women and men in Fig. 1. There is a non-linear association between BRI and the prevalence of CI among women (Fig. 1). The risk of CI increased rapidly until approximately 5.2 of predicted BRI and relatively flat afterward (P for non-linearity = 0.011) in women. The OR of CI was 3.32 (95% CI; 1.58–6.95, p = 0.001) in participants with a BRI of < 5.2 (Table 3). One-unit increase in BRI was associated with a 2.32-fold higher risk of CI. If BRI was > 5.2, there was no association between BRI and CI; hence, the risk of CI no longer increases with increasing BRI.

Fig. 1.

Association between BRI and cognitive impairment. 1A:female, 1B: male. Adjusted odds ratio of CI from restricted cubic spline (RCS) logistic regression models with knots at the 5th, 35th, 65th, and 95th percentiles. Adjusted for all covariates (age, marital status, education level, diabetes course, diabetic dietary control, smoking status, stroke, cardiovascular disease, microangiopathy, hypoglycemic events in last 3 months, eGFR, TC. The solid lines and bands represent the ORs and corresponding 95% CIs

Table 3.

Association between BRI and CI using two-piecewise regression models in females

| Crude model | Adjusted model* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRI | OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| < 5.2 | 3.37 (1.80–6.33) | < 0.001 | 3.32 (1.58–6.95) | 0.001 |

| ≥ 5.2 | 1.05 (0.70–1.57) | 0.824 | 0.91 (0.58–1.41) | 0.666 |

| Non-linear test | 0.004 | |||

*Adjust for age, marital status, education level, diabetes course, diabetic dietary pattern, smoking status, stroke, cardiovascular disease, microangiopathy, hypoglycemic events in last 3 months, eGFR, TC

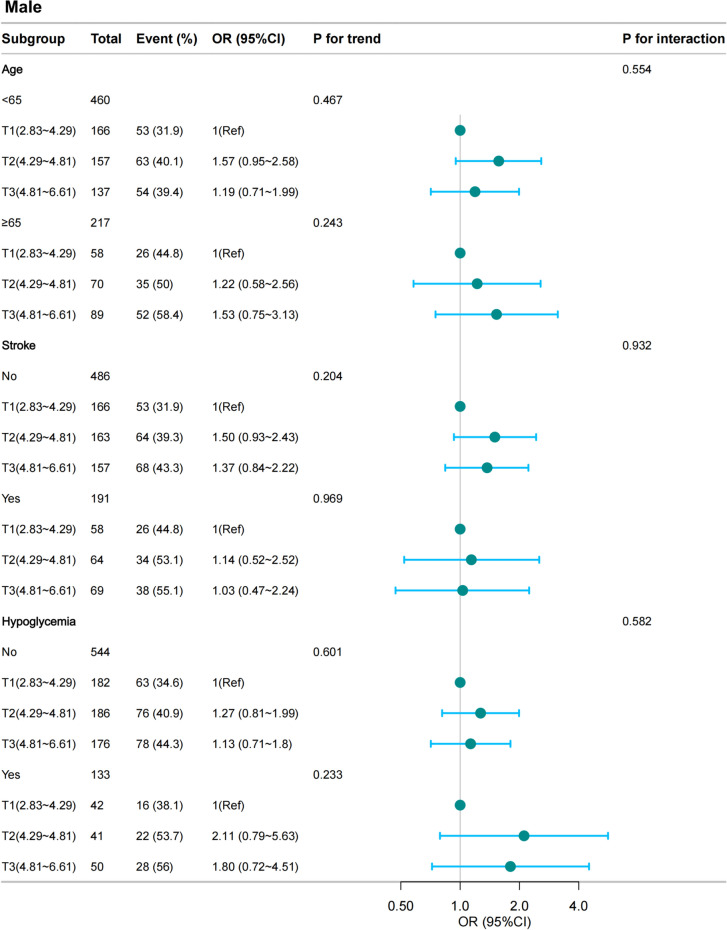

Stratified analyses

The results of subgroup analyses are presented in Figs. 2 (women) and 3 (men). No significant interactions were found in any subgroups after stratifying by age, stroke, and hypoglycemic events in the past 3 months (Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 2.

Stratified analyses of the association between BRI and CI according to baseline characteristics in female group. BRI was divided into four levels by tertiles (2.75 < T1 ≤ 4.92; 4.92 < T2 ≤ 5.56; 5.56 < T3 ≤ 8.28). The p value for interaction represents the likelihood of interaction between the variable and the BRI. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval, Hypoglycemia, Hypoglycemic events in last 3 months. BRI, body roundness index

Fig. 3.

Stratified analyses of the association between BRI and CI according to baseline characteristics in male group. BRI was divided into four levels by tertiles (2.75 < T1 ≤ 4.92; 4.92 < T2 ≤ 5.56; 5.56 < T3 ≤ 8.28). The p value for interaction represents the likelihood of interaction between the variable and the BRI. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval, Hypoglycemia, Hypoglycemic events in last 3 months. BRI, body roundness index

Discussion

The prevalence of CI in middle-aged and elderly T2D was 44.8% (590/1318). The participants’ mean age was 62.2 ± 7.7 years, 48.6% of whom were women. After adjusting for multiple variables, we observed a positive relationship between BRI and CI, elevated BRI was related with higher risk of CI, indicating that BRI may be a valuable metric for evaluating cognitive decline related to body shape in individuals with T2D. Based on stratified analyses, we found BRI was associated with CI in women, suggesting there were sex different in the association between BRI and CI.

There have been some research on the relationship between obesity and the risk of CI; however, the results were not consistent. Some studies suggested that high BMI appears to be a protective factor for cognitive function in patients with T2D [32]. In elderly Colombians, no significant relationship was found between BMI and the progression of cognitive decline [33]. Other studies found that BMI [34] and body fat percentage [35] increases the risk of CI in elderly. The limitations of BMI and variations in population can explain such inconsistent findings. Visceral obesity is identified as a recognized risk factor related to CI. Previous studies have confirmed that obesity indicators, such as WC and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) adjusted for BMI, were risk factors for CI in older patients with T2D [36, 37]. Although BMI and WC are commonly used to assess obesity, they may not fully reflect the impact of visceral obesity on CI. BRI, which accounts for WC besides weight and height, offers a more holistic indication of visceral fat distribution. Research on the relationship between BRI and CI remains limited. A study showed that elevated BRI was associated with CI in elderly US adults [38]. Knowingly, evidence on the association between BRI and CI in Chinese T2D populations is sparse. We used BRI to establish a positive association between obesity and CI among patients with T2D.

The potential biological mechanisms connecting obesity and CI are as follows: (i) Obesity results in insulin resistance in peripheral tissues, which can lead to insulin resistance in brain [39]. (ii) Obesity is associated with an imbalance in gut microbiota, which can trigger systemic inflammation and compromises the integrity of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), thereby facilitating the infiltration of inflammatory mediators into the brain and contributing to cognitive decline [40]. (iii) In individuals with obesity, adipose tissue secretes excessive amounts of inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) [41]. Elevated IL-6 levels induce the production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and release of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells; this disruption upregulates the expression of beta-secretase 1 (BACE1), leading to CI [42, 43]. INF-α activates astrocytes and microglia, leading to impaired learning and memory in the hippocampus [44]. (iiii) Obesity impacts cognitive function through alterations in adipokine levels, which exacerbates insulin resistance [40]. Additionally, obesity is related to a significant reduction in adiponectin levels, which increases the risk of insulin resistance and inflammation [45].

Knowingly, this is the first study to examine the association between the BRI and CI in middle-aged and elderly T2D in China, underscoring the potential of BRI in predicting CI. Sensitivity and subgroup analyses were conducted to substantiate the robustness of the results across different population groups. Moreover, we found BRI was associated with CI in women, suggesting there were sex different in the association between BRI and CI.

This study has limitations. First, owing to the cross-sectional nature of this study, we cannot establish the temporal association or causality between BRI and CI. Future research should prioritize well-designed longitudinal cohort studies to elucidate these associations. Despite the comprehensive adjustment for numerous potential confounders and consistency of results across various analytical approaches, the possibility of residual bias because of unmeasured confounding factors cannot be entirely ruled out. Additionally, the data are derived from a single-center cohort of hospitalized middle-aged and elderly patients with T2D and may not be generalized to other populations.

Conclusion

This cross-sectional study provides new evidence of BRI was an effective predictor of CI and showed superior predictive accuracy in women compared to men. In clinical practice, BRI could be used to assess CI, screening for cognitive function in individuals with abdominal obesity in T2D may be important for preventing cognitive decline.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants and the Department of Endocrinology at Tianjin Union Medical Center for their support.

Author contributions

Yanting Liu and Jingna Lin conceived and designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. Yanting Liu and Huina Qiu collected and managed data and performed statistical analysis. Jingna Lin and Meiyun Zhang contributed to study design, provided critical revisions to the manuscript, supervised the research, and reviewed and approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin City (Grant 18ZXDBSY00120) and Science and Technology Project of Tianjin Municipal Health Commission (Grant ZD20006).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tianjin Union Medical Center, Nankai University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Meiyun Zhang, Email: zmy22202@aliyun.com.

Jingna Lin, Email: 13207628978@163.com.

References

- 1.Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7(2):e105–25. 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00249-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Huang L, Xiong S, Liu H, Li M, Zhang R, Liu Y, et al. Bioinformatics Analysis of the Inflammation-Associated lncRNA-mRNA Coexpression Network in Type 2 Diabetes. J Renin-Angio-Aldo S. 2023;2023:6072438. 10.1155/2023/6072438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu X, Su Y, Liu J, Liu D, Yu C. Inhibition of Th17 cell differentiation by aerobic exercise improves vasodilatation in diabetic mice. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2024;46(1):2373467. 10.1080/10641963.2024.2373467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.You Y, Liu Z, Chen Y, Xu Y, Qin J, Guo S, et al. The prevalence of mild cognitive impairment in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Diabetol. 2021;58(6):671–85. 10.1007/s00592-020-01648-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen JF, Zhang YP, Han JX, Wang YD, Fu GF. Systematic evaluation of the prevalence of cognitive impairment in elderly patients with diabetes in China. Clin Neurol Neurosur. 2023;225: 107557. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2022.107557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomlin A, Sinclair A. The influence of cognition on self-management of type 2 diabetes in older people. Psychol Res Behav Ma. 2016;9:7–20. 10.2147/PRBM.S36238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Brien PD, Hinder LM, Callaghan BC, Feldman EL. Neurological consequences of obesity. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(6):465–77. 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30084-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dye L, Boyle NB, Champ C, Lawton C. The relationship between obesity and cognitive health and decline. P Nutr Soc. 2017;76(4):443–54. 10.1017/S0029665117002014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ntlholang O, McCarroll K, Laird E, Molloy AM, Ward M, McNulty H, et al. The relationship between adiposity and cognitive function in a large community-dwelling population: data from the Trinity Ulster Department of Agriculture (TUDA) ageing cohort study. Brit J Nutr. 2018;120(5):517–27. 10.1017/S0007114518001848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beeri MS, Tirosh A, Lin HM, Golan S, Boccara E, Sano M, et al. Stability in BMI over time is associated with a better cognitive trajectory in older adults. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18(11):2131–9. 10.1002/alz.12525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qizilbash N, Gregson J, Johnson ME, Pearce N, Douglas I, Wing K, et al. BMI and risk of dementia in two million people over two decades: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endo. 2015;3(6):431–6. 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ren Z, Li Y, Li X, Shi H, Zhao H, He M, et al. Associations of body mass index, waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio with cognitive impairment among Chinese older adults: based on the CLHLS. J Affect Disorders. 2021;295:463–70. 10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J, Sun J, Zhang Y, Zhang B, Zhou L. Association between weight-adjusted-waist index and cognitive decline in US elderly participants. Front Nutr. 2024;11:1390282. 10.3389/fnut.2024.1390282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19.2 million participants. Lancet. 2016;387(10026):1377–96. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30054-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Antonopoulos AS, Oikonomou EK, Antoniades C, Tousoulis D. From the BMI paradox to the obesity paradox: the obesity-mortality association in coronary heart disease. Obes Rev. 2016;17(10):989–1000. 10.1111/obr.12440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piche ME, Poirier P, Lemieux I, Despres JP. Overview of epidemiology and contribution of obesity and body fat distribution to cardiovascular disease: an update. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;61(2):103–13. 10.1016/j.pcad.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross R, Neeland IJ, Yamashita S, Shai I, Seidell J, Magni P, et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16(3):177–89. 10.1038/s41574-019-0310-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas DM, Bredlau C, Bosy-Westphal A, Mueller M, Shen W, Gallagher D, et al. Relationships between body roundness with body fat and visceral adipose tissue emerging from a new geometrical model. Obesity. 2013;21(11):2264–71. 10.1002/oby.20408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang X, Ma N, Lin Q, Chen K, Zheng F, Wu J, et al. Body roundness index and all-cause mortality among US adults. Jama Netw Open. 2024;7(6): e2415051. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.15051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Y, Wang C, Sun Q, Ye Q, Zhou H, Qin Z, et al. Comparison of novel and traditional anthropometric indices in Eastern-China adults: Which is the best indicator of the metabolically obese normal weight phenotype? BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):2192. 10.1186/s12889-024-19638-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.West RK, Ravona-Springer R, Heymann A, Schmeidler J, Leroith D, Koifman K, et al. Waist circumference is correlated with poorer cognition in elderly type 2 diabetes women. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(8):925–9. 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu M, Yu X, Xu L, Wu S, Tian Y. Associations of longitudinal trajectories in body roundness index with mortality and cardiovascular outcomes: a cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2022;115(3):671–8. 10.1093/ajcn/nqab412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang X, Ding L, Hu H, He H, Xiong Z, Zhu X. Associations of body-roundness index and sarcopenia with cardiovascular disease among middle-aged and older adults: findings from CHARLS. J Nutr Health Aging. 2023;27(11):953–9. 10.1007/s12603-023-2001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L, Yin J, Sun H, Dong W, Liu Z, Yang J, et al. The relationship between body roundness index and depression: a cross-sectional study using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011–2018. J Affect Disorders. 2024;361:17–23. 10.1016/j.jad.2024.05.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang Y, Guo X, Chen Y, Guo L, Li Z, Yu S, et al. A body shape index and body roundness index: two new body indices to identify diabetes mellitus among rural populations in northeast China. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:794. 10.1186/s12889-015-2150-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X, Guo Z, Wang M, Xiang C. Association between body roundness index and risk of osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis. 2024;23(1):334. 10.1186/s12944-024-02324-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang H, Si W, Li L, Yang K. Association between body roundness index and osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional analysis of NHANES 2011–2018. Front Nutr. 2024;11:1501722. 10.3389/fnut.2024.1501722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabetic Med. 1998;15(7):539–53. 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–9. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jia W, Weng J, Zhu D, Ji L, Lu J, Zhou Z, et al. Standards of medical care for type 2 diabetes in China 2019. Diabetes-Metab Res. 2019;35(6): e3158. 10.1002/dmrr.3158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AR, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–12. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xing Z, Long C, Hu X, Chai X. Obesity is associated with greater cognitive function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13: 953826. 10.3389/fendo.2022.953826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Donovan G, Sarmiento OL, Hessel P, Muniz-Terrera G, Duran-Aniotz C, Ibanez A. Associations of body mass index and sarcopenia with screen-detected mild cognitive impairment in older adults in Colombia. Front Nutr. 2022;9:1011967. 10.3389/fnut.2022.1011967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feinkohl I, Lachmann G, Brockhaus WR, Borchers F, Piper SK, Ottens TH, et al. Association of obesity, diabetes and hypertension with cognitive impairment in older age. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:853–62. 10.2147/CLEP.S164793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang H, Hai S, Liu YX, Cao L, Liu Y, Liu P, et al. Associations between Sarcopenic Obesity and Cognitive Impairment in Elderly Chinese Community-Dwelling Individuals. J Nutr Health Aging. 2019;23(1):14–20. 10.1007/s12603-018-1088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abbatecola AM, Lattanzio F, Spazzafumo L, Molinari AM, Cioffi M, Canonico R, et al. Adiposity predicts cognitive decline in older persons with diabetes: a 2-year follow-up. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(4): e10333. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen T, Liu YL, Li F, Qiu HN, Haghbin N, Li YS, et al. Association of waist-to-hip ratio adjusted for body mass index with cognitive impairment in middle-aged and elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):2424. 10.1186/s12889-024-19985-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang F, Ning Z, Wang C. Body roundness index and cognitive function in older adults: a nationwide perspective. Front Aging Neurosci. 2024;16:1466464. 10.3389/fnagi.2024.1466464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sripetchwandee J, Chattipakorn N, Chattipakorn SC. Links between obesity-induced brain insulin resistance, brain mitochondrial dysfunction, and dementia. Front Endocrinol. 2018;9:496. 10.3389/fendo.2018.00496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wong ZD, Tran V, Vinh A, Dinh QN, Drummond GR, Sobey CG, et al. Pathophysiological links between obesity and dementia. Neuromol Med. 2023;25(4):451–6. 10.1007/s12017-023-08746-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salas-Venegas V, Flores-Torres RP, Rodriguez-Cortes YM, Rodriguez-Retana D, Ramirez-Carreto RJ, Concepcion-Carrillo LE, et al. The Obese Brain: mechanisms of Systemic and Local Inflammation, and Interventions to Reverse the Cognitive Deficit. Front Integr Neurosc. 2022;16: 798995. 10.3389/fnint.2022.798995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ali M, Falkenhain K, Njiru BN, Murtaza-Ali M, Ruiz-Uribe NE, Haft-Javaherian M, et al. VEGF signalling causes stalls in brain capillaries and reduces cerebral blood flow in Alzheimer’s mice. Brain. 2022;145(4):1449–63. 10.1093/brain/awab387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Naomi R, Teoh SH, Embong H, Balan SS, Othman F, Bahari H, et al. The role of oxidative stress and inflammation in obesity and its impact on cognitive impairments—a narrative review. Antioxidants-Basel. 2023. 10.3390/antiox12051071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takahashi S, Fukushima H, Yu Z, Tomita H, Kida S. Tumor necrosis factor alpha negatively regulates the retrieval and reconsolidation of hippocampus-dependent memory. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;94:79–88. 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Forny-Germano L, De Felice FG, Vieira M. The role of leptin and adiponectin in obesity-associated cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurosci-Switz. 2018;12:1027. 10.3389/fnins.2018.01027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.